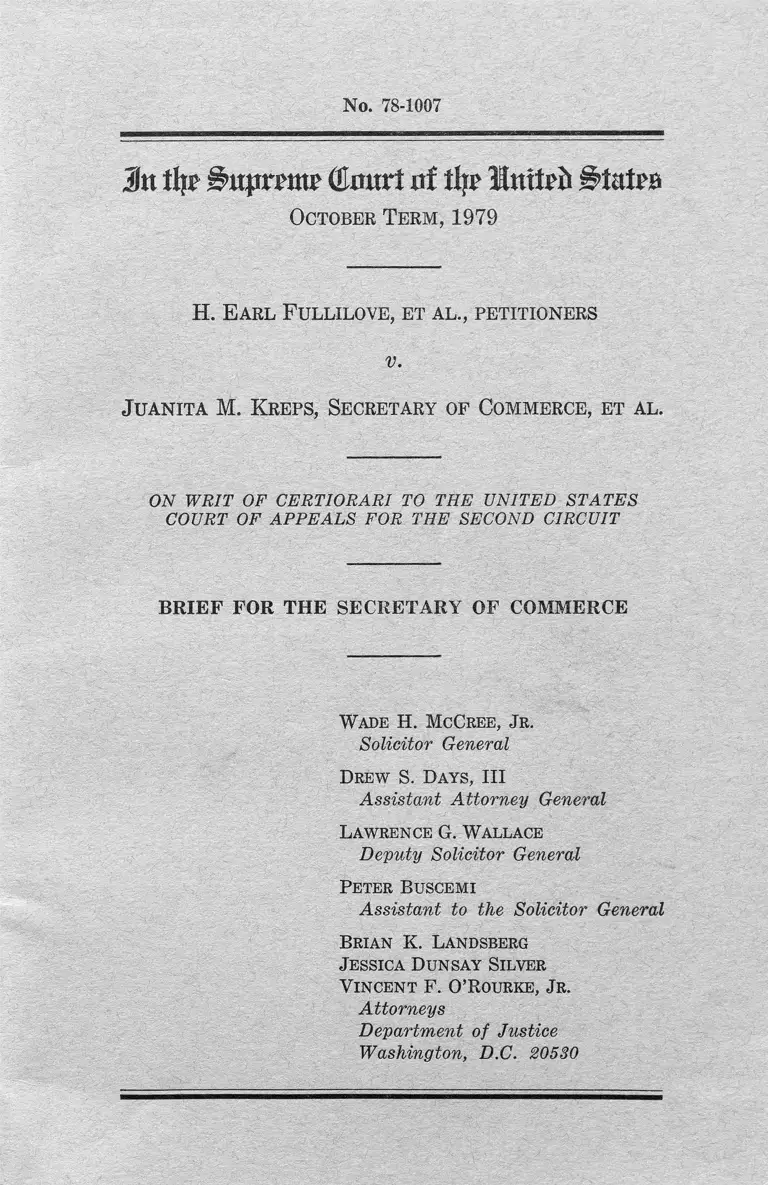

Fullilove v. Kreps Brief for the Secretary of Commerce

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1979

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Fullilove v. Kreps Brief for the Secretary of Commerce, 1979. d6ce877e-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/19f3f0cc-cac4-4506-a888-67859765992f/fullilove-v-kreps-brief-for-the-secretary-of-commerce. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

No. 78-1007

In % £>tqirma (Emtrt nf % Mnttafc

October Term , 1979

H. E arl F ullilove, et al., petitioners

v.

J uanita M. Kreps, Secretary of Commerce, et al.

ON W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED S T A T E S

COURT OF A P P E A LS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR THE SECRETARY OF COMMERCE

Wade H. McCree, Jr.

Solicitor General

Drew S. Days, III

Assistant Attorney General

Lawrence G. Wallace

Deputy Solicitor General

Peter Buscemi

Assistant to the Solicitor General

Brian K. Landsberg

Jessica Dunsay Silver

Vincent F. O’Rourke, Jr.

Attorneys

Department of Justice

Washington, D.C. 20530

I N D E X

Page

Opinions below ................................................... 1

Jurisdiction ......................................................... 1

Question presented..... ....................................... 2

Statement ........................................................... 2

Summary of argument ..................................... 13

Argument ............... 19

The minority business enterprise provi

sion of the Public Works Employment Act

of 1977 does not violate the Fifth Amend

ment or Title VI of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964 ....................................................... 19

A. Congress has broad authority to rem

edy the effects of past discrimination

through the exercise of the spending

power and the powers conferred by

the enforcement sections of the Thir

teenth and Fourteenth Amendments- 19

B. Congress concluded that legislative

action was necessary to eliminate the

effects of discrimination in the con

struction industry ............................. 26

C. The MBE provision is a constitution

ally permissible means by which Con

gress may seek to eliminate the ef

fects of discrimination in the con

struction industry............................... 51

II

D. The minority business enterprise pro

vision does not violate Title VI of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964 ................... 69

Conclusion ........................................................... 70

Appendix ............................................................. la

Argument—Continued Page

CITATIONS

Cases:

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S.

405 .......................................................15,23,56

Araya v. McLelland, 525 F.2d 1194 ___ 70

Associated General Contractors of Mass.,

Inc. v. Altshuler, 490 F.2d 9, cert, de

nied, 416 U.S. 957 .......... ............. ........ 38

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S.

483 ........................................................... 22

Buckley v. Valeo, 424 U.S. 1 .......... .......... 19

Califano v. Goldfarb, 430 U.S. 199 .... . 32

Califano v. Webster, 430 U.S. 313 ........... 32, 57

California Bankers Ass’n v. Shultz, 416

U.S. 21 ........ 19

Contractors Ass’n of Eastern Pennsyl

vania v. Secretary of Labor, 442 F.2d

159, cert, denied, 404 U.S. 854 ..... ..... 38

Constructors Ass’n of Western Pennsyl

vania v. Kreps, 441 F. Supp. 936, affd,

573 F.2d 811 ........................... ..... 34, 50-51, 69

Craig v. Boren, 429 U.S. 190 ................... 57

EEOC v. American Telephone & Tele

graph Co., 556 F.2d 167, cert, denied,

438 U.S. 915 .......... 57

EEOC v. Local 638, Sheet Metal Workers,

532 F.2d 821 13

Cases—Continued

in

Page

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co.,

Gaston County v. United States, 395 U.S.

285 -.......................................................... 23, 57

General Pictures Corp. v. Western Elec

tric Co., 304 U.S. 175 .......... ................ 60

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424.. 24

Heart of Atlanta Motel v. United, States,

379 U.S. 241 ....... ............... ................. 31

Helvering v. Davis, 301 U.S. 619............. 19, 20

Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, Inc.,

421 U.S. 454 ........................................... 20

Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S.

409 ...................... 20

Katzenbach v. Morgan, 384 U.S. 641....20, 24, 25,

31, 52, 61, 68

Lau v. Nichols, 414 U.S. 563 .................. . 19, 23

Lawn v. United States, 355 U.S. 339 ....... 60

McCulloch v. Maryland, 17 U.S. (4

Wheat.) 316 ............... 52

Morton v. Mancari, 417 U.S. 535 ......... 18, 69, 70

Nixon v. Administrator of General Serv

ices, 433 U.S. 425 ................... ............. 61

Perkins v. Lukens Steel Co., 310 U.S. 113.. 19

Oklahoma v. Civil Service Commission,

330 U.S. 127 ............... ............... ......... 19

Oregon v. Mitchell, 400 U.S. 112 ....... ..25, 28, 57

Regents of the University of California v.

Bakke, 438 U.S. 265 ______ passim

Rhode Island Chapter, Associated General

Contractors of America v. Kreps, 450

F. Supp. 338 .......................... ...... ....... 34, 38

Runyon v. McCrary, 427 U.S. 160 ......... 20

Schlesinger v. Reservists Committee to

Stop the War, 418 U.S. 208 __ ____ 27

Cases—Continued

IV

Page

29SEC v. Chenery Corp., 318 U.S. 8 0 .........

South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S.

301 .................. .......................... .............. 68

Steelworkers v. Weber, Nos. 78-432, 78-

435, 78-436 (June 27, 1979) ........... 38,59,61

Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324.. 23-24

Tillman v. Wheaton Haven Recreation

Ass’ll, 410 U.S. 431 _______ ____ _ 20

United Jewish Organizations v. Carey,

430 U.S. 144 _____________ __15, 23, 25, 58

United States v. Guest, 383 U.S. 745 __ 20

United States v. Ironworkers Local 86, 443

F.2d 544, cert, denied, 404 U.S. 984.... 38

United States v. Masonry Contractors

Ass’n of Memphis, 497 F.2d 871 ____ 38

Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropoli

tan Housing Development Corp., 429

U.S. 252 ....... ............... .................. ...... 31

Constitution, statutes, and regulations:

United States Constitution:

Article I __________ ____ ____ 15, 28, 31

Fifth Amendment ..... .............. ........ 2, 7

Thirteenth Amendment _____ 14, 19, 20, 36

Fourteenth Amendment __ 7, 14, 19, 20, 24,

25, 36

Civil Rights Act of 1957, Pub. L. No. 85-

315, 71 Stat. 634 _______ ___ _____ _ 22

Section 131, 42 U.S.C. (1958 ed.)

1971(b)-(e) 22

V

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Pub. L. No. 88-

352, 78 Stat. 241, 42 U.S.C. 2000a et

seq................. 22

Title VI, 42 U.S.C. 2000d et seq......2, 7,18,

19, 21, 35, 41, 45, 54, 69, 70

Title VII, 42 U.S.C. 2000e et seq...... ..7, 22,

35, 54

Comprehensive Employment and Training-

Act of 1973, 29 U.S.C. 991 ................... 21

Energy Conservation and Production Act,

42 U.S.C. 6870 ....................................... 21

Equal Credit Opportunity Act, Pub. L.

No. 93-495, 88 Stat, 1521, 15 U.S.C.

1691 et seq. .............................. ......... . 22, 54

Equal Credit Opportunity Act Amend

ments of 1976, Pub. L. No. 94-239, 90

Stat. 251 ____ 22

Equal Employment Opportunity Act of

1972, Pub. L. No. 92-261, 86 Stat. 103.. 22

Fair Housing Act of 1968, Pub. L. No. 90-

284, 82 Stat. 81-90 _____ ___ ______ 22

Housing and Community Development Act

of 1974, 42 U.S.C. 5309 ....................... 21

Constitution, statutes, and

regulations—Continued Page

Local Public Works Capital Development

and Investment Act of 1976, and as

amended by the Public Works Employ

ment Act of 1977, Pub. L. No. 95-28,

91 Stat. 116-120, 42 U.S.C. (and Supp.

I) 6701 et seq.:

42 U.S.C. 6701 ............. ..................... 2

42 U.S.C. (Supp. I) 66701 ............... 3

42 U.S.C. 6701-6710 ........................... 2

VI

42 U.S.C. 6705(d) ............................ 4,55

42 U.S.C. (Supp. I) 6705(e)(1) ..... 4

42 U.S.C. (Supp. I) 6705(f)(2) ..... 'passim

42 U.S.C. (Supp. I) 6705-6708 ......... 3

42 U.S.C. (and Supp. I) 6706 ........... 4, 55

42 U.S.C. (Supp. I) 6707(h) ...... . 55

42 U.S.C. 6709 .... ................ ...... ...... 45, 69

42 U.S.C. (Supp. I) 6710................. 3

Public Works Employment Act of 1977,

Pub. L. No. 95-28, 91 Stat. 116-120 ...... 3

Public Works Employment Appropriations

Act, Pub. L. No. 94-447, 90 Stat. 1497.. 2, 55

Small Business Act of 1958, Pub. L. No.

85-536, 72 Stat. 384, 15 U.S.C. 631 et

seq.:

Section 2(e) (to be codified in 15

U.S.C. 631(e)) ............... 66

Section 8(a), 15 U.S.C. 637(a) ..... . 41

Section 8(d), 15 U.S.C. 637(d) ...... 66

State and Local Assistance Amendments

of 1976, 31 U.S.C. 1242 .......... .............. 21

Voting Rights Act of 1965, Pub. L. No.

89-110, 79 Stat. 437, 42 U.S.C. (1964

ed., Supp. I ll) 1971 et seq..................... 22

42 U.S.C. (1964 ed., Supp. I ll) 1973-

1973p ______ 22

Voting Rights Act Amendments of 1970,

Pub. L. No. 91-285, 84 Stat. 314 ......... 22

Voting Rights Act Amendments of 1975,

Pub. L. No. 94-73, 89 Stat. 400 .......... 22

Constitution, statutes, and

regulations—Continued Page

VII

Pub. L. No. 95-507, 92 Stat. 1757-1773:

Section 201, 92 Stat. 1760 ................. 66

Section 211, 92 Stat. 1767-1770 ....... 66

91 Stat. 122............................... .............. _. 55

91 Stat. 123-124 ...................................... 2

15 U.S.C. 694a ....... ...... ............. .............. 54

15 U.S.C. 694b ____ ____ ________ _ 54

42 U.S.C. 1975c(b) ........................... . 36

42 U.S.C. 1981 ......... ..... ............. 7, 21, 36, 41, 54

42 U.S.C. 1983 ............ ....... ........ .......... 7

42 U.S.C. 1985 ....... 7

13 C.F.R. 317.19(b) ........ 4

13 C.F.R. 317.19(b) (2) ........ 3

13 C.F.R. 317.30 ........ 55

13 C.F.R. 317.35(j) ................................. 5

13 C.F.R. 317.74(e) ....... 55

41 C.F.R. 1-1.1302 ...... 33,41

41 C.F.R. 1-1.1303 ............. 33

41 C.F.R. 1-1.1310-2 ........ 33

41 C.F.R. 60-2.11 (b)(1) ......................... 63

Miscellaneous:

1972 Census of Construction Industries,

United States Summary—Statistics for

Construction Establishments With and

Without Payrolls (August 1975) ....... 38, 39

122 Cong. Rec. (1976) :

p. 13866 ........................................ 35

p. 34754 ............................................. 36

123 Cong. Rec.:

p. H1423 (daily ed. Feb. 24, 1977).... 33, 48

p. H1436 (daily ed. Feb. 24, 1977).... 45

Constitution, statutes, and

regulations—Continued Page

VIII

PP- H1436-H1437 (daily ed. Feb. 24,

1977) .......... 46

p. H1437 (daily ed. Feb. 24, 1977).... 47

pp. H1437-H1438 (daily ed. Feb. 24,

1977) ............................................... 48

p. H1440 (daily ed. Feb. 24, 1977).... 47, 48

pp. H1461-H1462 (daily ed. Feb. 24,

1977) ............................................... 48

p. S3910 (daily ed. Mar. 10, 1977).... 33

pp. S3926-S3929 (daily ed. Mar. 10,

1977) ............................................... 49

pp. S6755-S6757 (daily ed. Apr. 29,

1977) .................... 49

pp. H3920-H3935 (daily ed. May 3,

1977) ....... 49

124 Cong. Rec. E985 (daily ed. Mar. 2,

1978) 35.36

Cox, Foreword: Constitutional Adjudica

tion and the Promotion of Human

Rights, 80 Harv. L. Rev. 91 (1966).... 52

Exec. Order No. 11,246, 30 Fed. Reg.

12319 (1965), as amended by Exec.

Order No. 11,375, 32 Fed. Reg. 14303

(1967), and Exec. Order No. 12,086, 43

Fed. Reg. 46501 (1978) ....................... 63

Exec. Order No. 11,458, 34 Fed. Reg. 4937

(1969), as amended by Exec. Order No.

11,625, 36 Fed. Reg. 19967 (1971) ...... 41

35 Fed. Reg. 11595 (1970) ....................... 23

Miscellaneous—Continued Page

IX

Government Minority Enterprise Pro

grams—Fiscal Year 197U: Hearings

Before the Sub comm, on Minority Small

Business Enterprise and Franchising of

the House Permanent Select Comm, on

Small Business, 93d Cong., 1st Sess.

(1973) ...................... ............ ......... 34

Government Minority Small Business Pro

grams: Hearings Before the Subcomm.

on Minority Small Business Enterprise

of the House Select Comm, on Small

Business, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. (1971).. 34

H.R. 11 , 95th Cong., 1st Sess. (1977) __ 48

H.R. Conf. Rep. No. 95-230, 95th Cong.,

1st Sess. (1977) ........ ............ ....... ....... 49

H.R. Rep. No. 94-468, 94th Cong., 1st

Sess. (1975) ........... ....... ............. ......... 34,37

H.R. Rep. No. 94-1791, 94th Cong., 2d

Sess. (1977) ..................................... 36,41

H.R. Rep. No. 95-20, 95th Cong., 1st Sess.

(1977) .................... 32

Minorities and Women as Government

Contractors, A Report of the United

States Commission on Civil Rights

(May 1975) .............. .....’....36-37,63

Minority Business Development Adminis

tration: Hearings Before the Minority

Subcomm. on Intergovernmental Rela

tions of the Senate Comm, on Govern

ment Operations, 94th Cong., 2d Sess.

(1976) ........................................... 35,36

Miscellaneous—Continued Page

Miscellaneous—Continued

x

Minority Enterprise and Allied Problems

of Small Business: Hearings Before the

Subcomm. on SBA Oversight and Mi

nority Enterprise of the House Comm,

on Small Business, 94th Cong., 1st Sess.

(1975) ______________ ___________ 34

Monaghan, Foreword: Constitutional Com

mon Law, 89 Harv. L. Rev. 1 (1975)..,. 53

Public Works Employment Act of 1977:

Hearings Before the Subcomm. on Re

gional and Community Development of

the Senate Comm, on Environment and

Public Works, 95th Cong., 1st Sess.

(1977) _______ .____ ___ __________ 33

Review of Small Business Administra

tion’s Programs and Policies—1971:

Hearings Before the Senate Select

Comm, on Small Business, 92d Cong.,

1st Sess. (1971) __________ _______ 34

B. Schwartz, Statutory History of the

United States— Civil Rights (1970) .... 22

S. Conf. Rep. No. 95-110, 95th Cong., 1st

Sess. (1977) .................... ......... ...... . 49

S. Rep. No. 95-38, 95th Cong., 1st Sess.

(1977) _____ ____ ______ __________ 32

1972 Survey of Minority-Owned Business

Enterprises, Minority-Owned Businesses

(May 1975) ................ ....... ............. ...... 39

The Effects of Government Regulations

on Small Business and the Problems of

Women and Minorities in Small Busi

ness in the Southwestern United States:

Hearings Before the Senate Select

Comm, on Small Business, 94th Cong.,

2d Sess. (1976) ..................................... 34, 38

Page

XI

Miscellaneous—Continued

To Amend and Extend the Local Public

Works Capital Development and Invest

ment Act: Hearings Before the Sub-

comm. on Economic Development of the

House Comm, on Public Works and

Transportation, 95th Cong., 1st Sess.

(1977) ........................................ ....... 43,44,45

13 Weekly Corap. of Pres. Doc.:

p. 511 (Apr. 8, 1977) ......... ............. 53

p. 1333 (Sept. 12, 1977) ................... 51

In % j^upran? (Lmxrt nf tltt> TUnxttb States

October Term , 1979

No. 78-1007

H. E arl F ullilove, et al., petitioners

v.

Juanita M. Kreps, Secretary of Commerce, et al.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STA TE S

COURT OF A P PEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR THE SECRETARY OF COMMERCE

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the court of appeals (A. 206a-224a)

is reported at 584 F.2d 600. The opinion of the dis

trict court (A. 183a-204a) is reported at 443 F.

Supp. 253.

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the court of appeals was entered

on September 22, 1978. The petition for a writ of

certiorari was filed on December 21, 1978, and

granted on May 21, 1979. The jurisdiction of this

Court rests on 28 U.S.C. 1254(1).

(1 )

2

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether the minority business enterprise provision

of the Public Works Employment Act of 1977 vio

lates the Fifth Amendment or Title VI of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964.

STATEMENT

1. In July 1976, Congress enacted legislation de

signed to alleviate national unemployment and to

stimulate the economy by distributing two billion

dollars to state and local governments for public

works projects. The legislation, entitled the Local

Public Works Capital Development and Investment

Act of 1976, 42 U.S.C. 6701-6710, charged the Sec

retary of Commerce with the responsibility of dis

bursing the funds through the Economic Develop

ment Administration. The Act provided that the

funds were to be available for appropriation until

September 30, 1977. 42 U.S.C. 6710.1 In May 1977

Congress amended the 1976 Act by authorizing an

additional four billion dollars for similar projects.

The total of six billion dollars was to be available

for appropriation until December 31, 1978. 42 U.S.C.

(Supp. I) 6710.2

1 The Local Public Works Act itself merely authorized the

appropriation of two billion dollars for the local public works

program. Congress made the actual appropriation several

weeks later in the Public Works Employment Appropriations

Act, Pub. L. No. 94-447, 90 Stat. 1497.

2 On the same day that Congress authorized the appropria

tion of an additional four billion dollars for the local public

works program, it appropriated the full amount of the newly

authorized funds. 91 Stat. 123-124.

The new statute, entitled the Public Works Em

ployment Act of 1977, Pub. L. No. 95-28, 91 Stat

116-121, made various changes in the 1976 Act, in

cluding the addition of Section 103(f) (2), 42 U.S.C.

(Supp. I) 6705(f)(2), the “minority business en

terprise” provision.8 Section 103(f)(2) provides:

Except to the extent that the Secretary deter

mines otherwise, no grant shall be made under

this Act for any local public works project un

less the applicant gives satisfactory assurance to

the Secretary that at least 10 per centum of the

amount of each grant shall be expended for mi

nority business enterprises. For purposes of this

paragraph the term “minority business enter

prise” means a business at least 50 per centum

of which is owned by minority group members

or, in the case of a publicly owned business, at

least 51 per centum of the stock of which is

owned by minority group members. For the

purposes of the preceding sentence, minority

group members are citizens of the United States

who are Negroes, Spanish-speaking, Orientals,

Indians, Eskimos and Aleuts.

The circumstances under which the Secretary will

waive the 10% minority set-aside requirement are

described in regulations promulgated under the Act.

13 C.F.R. 317.19(b) (2). 3

3 The changes are codified in 42 U.S.C. (Supp. I) 6701 and

note, 6705-6708, and 6710 and note.

Section 103 of the Public Works Employment Act of 1977

added subsection (f) (2) to Section 106 of the Local Public

Works Capital Development and Investment Act of 1976 (see

91 Stat. 116-117). The parties and the courts below have re

ferred to the minority business enterprise provision as Section

103(f) (2) and, to avoid confusion, we will continue to refer

to it in that manner.

3

4

The 1976 Act and the 1977 amendments contained

several provisions designed to ensure that the local

public works program would have its intended effect

of providing an immediate boost to the economy gen

erally and the construction industry in particular.

Congress directed that no part of any public works

project funded under the statute should be performed

directly by any state or local government agency, but

rather that all project construction should be per

formed by private contractors who submit the lowest

competitive bids in response to invitations from the

grantees and who meet established criteria of re

sponsibility (42 U.S.C. (Supp. I) 6705(e)(1)). In

addition, Congress required grant applicants to give

satisfactory assurance that on-site labor would be

gin within 90 days of project approval (42 U.S.C.

6705(d)) and instructed the Secretary to make a

final determination on each grant application with

in 60 days of receipt (42 U.S.C. (and Supp. I)

6706). Moreover, the federal funds were required to

be committed to state and local grantees by September

30, 1977 (see note 30, infra).

In accordance with the requirements of the 1976

Act, 42 U.S.C. (and Supp. I) 6706, the Secretary

issued regulations to implement the local public works

program. The regulation concerning the minority

business enterprise provision stated (13 C.F.R. 317.19

(b )):

(1) No grant shall be made under this part

for any project unless at least ten percent of

the amount of such grant will be expended for

contracts with and/or supplies from minority

business enterprises.

5

(2) The restriction contained in paragraph

(b)(1) of this section will not apply to any grant

for which the Assistant Secretary [for Eco

nomic Development] makes a determination that

the 10 percent set-aside cannot be filled by mi

nority businesses located within a reasonable

trade area determined in relation to the nature

of the services or supplies intended to be

procured.

See also 13 C.F.R. 317.35(j). To supplement and

elaborate on the statute and regulation, the Economic

Development Administration issued guidelines govern

ing minority business participation in local public

works grants (A. 156a-167a) and a technical bulle

tin (A. 129a-155a) providing detailed instructions

and information to assist grantees and their con

tractors in meeting the 10% minority business en

terprise (MBE) requirement.

The guidelines state (A. 157a) that “ [t]he pri

mary obligation for carrying out the 10% MBE par

ticipation requirement rests with EDA Grantees.”

This obligation can be satisfied through the grantee’s

“own simple or prime contracts or through the sub

contracts or supply contracts of its prime contrac

tors” (A. 162a). Grantees must submit reports to

EDA, both before the first federal letter of credit

is issued and when the project is 40% complete, de

scribing actual and expected minority business par

ticipation (A. 162a-164a). In addition, grantees must

file a statement from each participating minority

firm “certifying that the minority firm is a bona

fide minority business enterprise and that the mi

nority firm has executed a binding contract to pro

vide a specific service or material to the project for

a specific dollar amount” (A. 164a).

The guidelines provide that EDA will approve a

grantee’s request for a waiver of the minority busi

ness requirement if the grantee “demonstrate [s] that

there are not sufficient, relevant, qualified minority

business enterprises whose market areas include the

project location” (A. 165a). Recognizing the prob

lems that a grantee may encounter in attempting to

comply with the MBE provision in an area where

the minority population is small, the guidelines per

mit a grantee to “apply for a waiver before request

ing bids on its project or projects if it can show that

there are no relevant, available, qualified minority

business enterprises which could reasonably be ex

pected to furnish services or supply materials for the

project” (A. 166a).

By the time Congress authorized the additional

four billion dollars of local public works grants in

May 1977, all grants authorized by the 1976 Act had

been awarded. The further grants authorized in

1977—the grants to which the minority business en

terprise provision applied—were all awarded by Sep

tember 30, 1977. Information submitted to the dis

trict court shows that respondent New York State

received at least 45 grants totaling $42,119,000 from

funds appropriated in 1977 and that respondent New

York City received at least 83 grants totaling $193,-

838,646 (A. 36a).4

4 Although all grants were awarded more than two years

ago, construction on many funded public works projects is

not yet complete. Moreover, in October 1979, we were in

6

7

2. On November 80, 1977, petitioners—four asso

ciations of construction firms and a mechanical con

tracting firm specializing in heating and air condi

tioning work—filed this action in the United States

District Court for the Southern District of New York.

They alleged (A. lla-12a) that Section 103(f) (2) of

the Act, the minority business enterprise provision,

caused them competitive injury by excluding them

from participating in subcontracts that they other

wise would have obtained in competitive bidding, by

requiring them to subcontract work that they ordi

narily would have performed themselves, and by com

pelling them to choose subcontractors according to

criteria other than the amount of their bids and their

performance records. They contended (A. 13a-15a)

that Section 103(f)(2) establishes an impermissible

racial classification and violates the Fifth and Four

teenth Amendments, the Reconstruction Civil Rights

Acts (42 U.S.C. 1981, 1983, 1985), and Titles VI

and VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (42 U.S.C.

2000d, 2000e et seq.). Petitioners sought a tempo

rary restraining order and a permanent injunction

formed by the Economic Development Administration that

there were some cost underruns on New York City projects

and that additional contracts would be let to utilize the

remaining funds and that the MBE provision may apply

to these contracts. There is also the possibility that on some

projects the EDA will find that a subcontractor represented

to be a minority business enterprise is not in fact a bona fide

MBE. This may result in a requirement that the grantee

expend other project funds for an acceptable minority con

tract, that he return a portion of the grant funds to the

United States Treasury, or that he obtain a waiver.

8

against enforcement of the minority business enter

prise provision by the Secretary of Commerce and

the state and local respondents (recipients of funds

distributed under the Act). Petitioners also sought

a declaratory judgment that Section 103(f)(2) is

“unconstitutional, illegal[,] void[,] and unenforce

able” (A. 19a).

After a trial,5 the district court denied petitioners’

requests for relief and dismissed the complaint. The

court held (A. 187a) that

5 Petitioners presented only two witnesses. Both were

officers in construction firms belonging to one of the peti

tioner associations. Each testified that his company had been

awarded contracts funded under the Act and that, in order

to satisfy the requirements of Section 103(f) (2), the com

pany would obtain supplies or services from minority sub

contractors. The witnesses stated that, in the absence of

the MBE provision, their firms would deal with other sub

contractors who could offer lower prices, more experience, or

both. They conceded, however, that any additional costs

attributable to the use of minority subcontractors would

be reflected in the overall bid and would thus be passed on

to the local grantee (and ultimately to the federal govern

ment) (A. 58a-97a).

The president of petitioner Shore Air Conditioning Com

pany submitted an affidavit (A. 23a-27a) alleging that the

company’s low bid on one project had been rejected because

the grantee determined that the purported minority subcon

tractor with which Shore proposed to deal was not a bona

fide minority business enterprise within the meaning of the

Act and that therefore Shore’s bid did not satisfy the require

ments of Section 103(f) (2). With the exception of this affi

davit, petition^ offered no direct evidence that they or any of

their member firms had lost business as a result of the MBE

provision. No subcontractor testified at trial.

James F. McNamara, an Assistant Commissioner of the

New York State Division of Human Rights, appeared as a

9

the MBE requirement is an entirely constitu

tional method of remedying prior acts of dis

crimination in the construction industry and

one which is fully consistent with the civil rights

laws that preceded it.

The court acknowledged that the provision “distin

guishes among various business enterprises, at least

in part, based upon the racial background of their

principals” (A. 191a). Because of the statute’s reli

ance on race, “an inherently ‘suspect’ classification,”

the district court determined that “rigid scrutiny of

witness for the Secretary and testified about the problems

encountered by minority contractors in the construction in

dustry. He explained that bonding requirements frequently

pose a serious obstacle for minority businessmen “because

the insurance companies and the banks will not cooperate

with them if they don’t have an established track record

[and t]hey can not establish a track record if they don’t get

a chance to perform” (A. 113a). He also stated that minority

firms have difficulty securing contracts because many of

their employees are minority workers who are not union

members and whom the unions refuse to accept (ibid.). In

addition, the witness said that minority contractors operate

at a disadvantage because “ [t] hey are not plugged in on the

information. They may not be able to get advanced drawings

or may not be able to get access to * * * the preliminary

plans and budget estimates. * * * [B]y not having access to

this information they are further frozen out” (A. 114a).

McNamara reported that the New York State agencies partici

pating in the MBE program considered it to be “the first really

successful route in assuring that there will be a portion of

the work going to minority contractors” (ibid.). He also

testified that the MBE provision had improved the employ

ment prospects for minority workers, among whom the un

employment rate was almost twice as high as that prevailing

within the white population (A. 115a).

10

both Congressional purpose and the means selected to

effectuate that purpose is clearly mandated” (ibid.).

The court stated that, in order to satisfy constitu

tional requirements, the MBE provision must serve

a compelling governmental interest and must be no

more discriminatory than other available means of

accomplishing the same objective (ibid.). The court

found (A. 192a-202a) that the MBE provision passes

both parts of this test.

With respect to the legitimacy of the congressional

purpose underlying the 10% minority participation

standard, the court first noted petitioners’ concession

that a racial classification serves a compelling govern

ment interest if it is intended to remedy the effects

of present or past discrimination (A. 192a). The

district court then reviewed the available materials

and concluded that Congress acted with just such a

remedial purpose in mind. The court examined the

limited legislative history of the MBE provision it

self, the numerous other federal antidiscrimination

measures in recent years, and the empirical data

available to Congress reflecting the disproportionately

small role of minority business concerns in the na

tional economy generally and the construction indus

try in particular. On the basis of this evidence, the

district court concluded that Section 103(f) (2) “was

incorporated into the Act after only brief debate be

cause of a general awareness of the compelling need

for legislative action capable of overcoming the ef

fects of prior discrimination against minority busi

11

nesses seeking to participate in government contract

ing” (A. 196a-197a).

Turning its attention to the means chosen by Con

gress to accomplish this purpose, the district court

ruled (A. 199a-202a) that the 10% MBE require

ment is a reasonable method of “promptly alleviating

the handicap imposed upon minority businesses due

to the lingering effects of discriminatory conduct in

the construction industry” (id. at 202a), In support

of this holding, the court cited (1) “the consistent

failure of less intrusive attempts to nurture the

growth of minority enterprises” (A. 202a); (2)

the limited percentage of annual government con

tracting affected by the MBE requirement (A. 201a);

(3) the short-term nature of the local public works

program established by the Act (A. 201a-202a); and

(4) the availability of a waiver provision to guard

against the possibility that work on funded projects

would be disrupted in particular areas by the lack of

sufficient qualified minority businesses to fulfill the

10% requirement (A, 201a).

Finally, the district court rejected (A. 202a-203a)

petitioners’ contention that the MBE provision vio

lates the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and 1964. The

court stated that “it defies credulity to argue that

measures intended to correct the invidious effects of

racial discrimination must be limited to remedies

which are not race sensitive, for minority groups

would forever be frozen into the status quo if that

were the intent of the Civil Rights Acts” (ibid.).

4. The court of appeals affirmed (A. 206a-224a).

The court held that “even under the most exacting

standard of review the MBE provision passes consti

tutional muster” (A. 211a). The court therefore

found it unnecessary to determine “ [wjhether rigid

scrutiny is mandated whenever an act of Congress

conditions the allocation of federal funds in a manner

which differentiates among persons according to their

race” (ibid.).

The court of appeals agreed with the district court

that the minority business enterprise provision in the

1977 Act was intended to remedy past discrimination

against minority construction businesses (A. 215a).

The court also agreed with the district court that

materials available to Congress provided ample sup

port for the conclusion that the severe shortage of

potential minority entrepreneurs with general busi

ness skills is a result of their historic exclusion from

the mainstream economy and that “the history of

discrimination was specific to the construction indus

try” (A. 218a; see also A. 194a).

Acknowledging that remedies for past discrimina

tion should be “sensitive to interests which may be

adversely affected” by such relief (A. 220a), the

court of appeals analyzed the likely impact of the

minority business enterprise provision on non-minor

ity contractors. For reasons similar to those that

persuaded the district court, the court of appeals

ruled that Section 103(f) (2) would not have an in

equitable effect on a “ ‘small, ascertainable group of

non-minority persons’ ” (A. 221a, quoting from

13

EEOC v. Local 638, Sheet Metal Workers, 532 F.2d

821, 828 (2d Cir. 1976)). The set-aside for minority

contractors, the court noted (A. 221a-222a; footnote

omitted),

extends to only .25 percent of funds expended

yearly on construction work in the United States.

The extent to which the reasonable expectations

of [petitioners], who are part of that industry,

may have been frustrated is minimal. Further

more, since according to 1972 census figures

minority-owned businesses amount to only 4.3

percent of the total number of firms in the con

struction industry, the burden of being dispre-

ferred in .25 percent of the opportunities in the

construction industry was thinly spread among

nonminority businesses comprising 96 percent of

the industry. Considering that nonminority

businesses have benefited in the past by not hav

ing to compete against minority businesses, it is

not inequitable to exclude them from competing

for this relatively small amount of business for

the short time that the program has to run.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

1. In the exercise of its power to spend public

money for the general welfare, Congress enacted the

Public Works Employment Act of 1977 to revive the

sluggish construction industry and stimulate the

economy generally. As part of its prescription for

the appropriate use of four billion dollars in federal

funds, Congress provided that, to the extent possible,

10% of the funds granted for each local public works

project should be expended for minority business en

14

terprises. By thus conditioning the grant of federal

monies to state and local applicants, Congress sought

to remedy the effects of racial and ethnic discrimi

nation in the construction industry and to ensure

that minority contractors would share equitably in

the benefits conferred by the public works program.

Such a legislative purpose is unquestionably legiti

mate.

The Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments em

power Congress to enforce the constitutional prohi

bition against slavery and involuntary servitude and

to secure the equal protection of the laws for persons

of every racial and ethnic background. When Con

gress acts in pursuit of its enforcement responsibili

ties under the Civil War Amendments, it enjoys a

considerable flexibility in fashioning measures to

achieve its important antidiscrimination objectives.

As Mr. Justice Powell observed in Regents of the

University of California v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265, 302

n.41 (1978), this Court has “recognized the special

competence of Congress to make findings with respect

to the effects of identified past discrimination and

its discretionary authority to take appropriate reme

dial measures.” When the congressional aim is to

eliminate discrimination and remedy its effects, race

conscious affirmative measures are permissible, pro

vided that they do not impose excessive burdens on

persons outside the group benefited by the legislative

action. See Regents of the University of California

v. Bakke, supra, 438 U.S. at 362-369 (opinion of

Brennan, White, Marshall, and Blackmun, J J . ) ;

15

United Jewish Organizations v. Carey, 430 U.S. 144

(1977); Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S.

405, 435 (1975).

2. Petitioners contend that the minority business

enterprise provision is invalid, because Congress did

not adequately describe and document the remedial

purpose for the statute’s enactment. This argument

rests on an erroneous view of the legislative process.

Congress does not sit as a court or an administra

tive agency making individualized decisions on the

basis of a limited record. Rather, Congress legislates

broad general rules for the governance of the nation

as a whole, and it acts on the basis of everything it

knows about a particular problem, regardless of the

source. Congress is not bound to consider only mate

rials that satisfy certain evidentiary standards, and

it is not required to announce, in accordance with

some predetermined format, the reasons for legisla

tive action. Article I of the Constitution prescribes

the procedures that Congress must follow in enacting

a law, and nowhere does it mention any requirement

of “detailed findings in the legislative record” such

as petitioners would impose.

The courts below properly examined all evidence

of the legislative purpose underlying the minority

business enterprise provision and correctly concluded

that Congress enacted the measure in order to rem

edy the effects of discrimination against minority-

owned businesses. While the primary aims of the

Public Works Employment Act were economic, Sec

tion 103(f)(2) was added to the statute to ensure

16

that the newly authorized funds would not be used

to perpetuate or reinforce discrimination in the con

struction industry. Congress’ purpose in enacting the

10% minority set-aside provision emerges clearly

when the contemporaneous legislative history is con

sidered in conjunction with Congress’ knowledge of

the economic plight of minority businesses and work

ers, its awareness of past discriminatory practices,

and its disappointing experience with earlier legisla

tive efforts to encourage the development of minority

business firms.

3. The MBE provision was a proper means by

which Congress could accomplish its remedial pur

pose. Congress ordinarily enjoys considerable dis

cretion in exercising its enumerated powers, and that

principle is particularly compelling when Congress

acts to enforce the guarantees of the Civil War

Amendments. Because of its investigative capabili

ties and its representative role in our tripartite sys

tem of government, the Legislative Branch is unique

ly suited to devise remedial measures that promise

effective solutions to difficult social problems and that

take adequate account of the competing interests at

stake in the distribution of government benefits, and

to adjust those remedies in the light of experience.

The 10% minority set-aside provision was a rea

sonable congressional response to the failure of previ

ous legislative measures to generate significant mi

nority participation in federal contracting pro

grams and to the need for expedition in providing

emergency economic relief under the local public

17

works program. Congress had ample reason to be

lieve that, if minority businesses were to obtain any

meaningful benefit from the new appropriation au

thorized in 1977, affirmative measures like those con

tained in the MBE provision were necessary.

The solution chosen by Congress did not impose

any undue disadvantage on nonminority contractors.

This Court has acknowledged that some “sharing of

the burden” of past discrimination may be required

for remedial purposes (Franks v. Bowman Transpor

tation Co., 424 U.S. 747, 777 (1976)), and the “shar

ing” required here did not have any significant ad

verse effect on the members of petitioner associations.

The racial classification was employed only on a

short-term basis and only in one federal program.

No contractor was precluded from bidding on any

particular contract, and, as long as the overall 10% re

quirement was met, no grantee was required to award

any particular contract to a minority business. The

10% set-aside did not “stigmatize” any identifiable

nonminority group, and no nonminority contractor

was excluded from his occupation by the partial

preference given to nonminority businesses. Pursuant

to the statutory authorization in Section 103(f)(2),

the Secretary established and utilized a waiver pro

cedure to deal with the possible unavailability of suf

ficient qualified minority contractors to satisfy the

10% requirement on particular projects.

For all these reasons, the members of petitioner

associations suffered no unnecessary adverse impact

from the 10% minority set-aside provision. Peti

18

tioners’ argument that Congress could have achieved

the same result through “less drastic” means is un-

persuasive. The alternatives suggested by petition

ers also involve the use of race as a selection or eli

gibility criterion and in that way are constitutionally

indistinguishable from Section 103(f) (2). A broader

selection standard, such as social or economic disad

vantage, would have included many persons who were

not members of minority groups that had suffered

discrimination in the past. Congress reasonably could

have concluded that the eligibility of such persons

for the limited special treatment required in the fed

erally funded program would have impeded the

achievement of the legitimate goal of remedying the

effects of discrimination in the construction industry.

4. The minority business enterprise provision does

not violate Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Regents of the University of California v. Bakke,

supra, established that Title VI does not prohibit a

constitutionally valid, remedial race-conscious pro

gram. 438 U.S. at 287 (opinion of Powell, J .) ; id.

at 325-326 (opinion of Brennan, White, Marshall,

and Blackmun, JJ.). Where two statutes are cap

able of co-existence, the courts must regard each as

effective. Morton v. Mancari, 417 U.S. 535, 551

(1974). Moreover, even if there were a conflict, it

should be resolved in favor of the later-enacted and

more specific statute, the Public Works Employment

Act of 1977.

19

ARGUMENT

THE MINORITY BUSINESS ENTERPRISE PROVI

SION OF THE PUBLIC WORKS EMPLOYMENT ACT

OF 1977 DOES NOT VIOLATE THE FIFTH AMEND

MENT OR TITLE VI OF THE CIVIL RIGHTS ACT

OF 1964

A. Congress Has Broad Authority to Remedy the Effects

of Past Discrimination Through the Exercise of the

Spending Power and the Powers Conferred by the

Enforcement Sections of the Thirteenth and Four

teenth Amendments

This Court has often acknowledged the congres

sional power to spend money in the national interest

and to impose conditions on such expenditures, es

pecially those in the form of grants to state or local

governments or private entities. See, e.g., Helvering

v. Davis, 301 U.S. 619, 640-641 (1937); Perkins v.

Lukens Steel Co., 310 U.S. 113, 127 (1940); Okla

homa v. Civil Service Commission, 330 U.S. 127, 143,

144 (1947); Lau v. Nichols, 414 U.S. 563, 569

(1974); California Bankers Ass’n v. Shultz, 416

U.S. 21, 50 (1974); Buckley v. Valeo, 424 U.S. 1,

91 (1976). Moreover, the Court has recognized that

the concept of the general welfare is not static and

that Congress retains substantial discretion to de

termine the ways in which federal funds should be

allocated and distributed. As Mr. Justice Cardozo

wrote for the Court in sustaining the constitutionality

of the Social Security Act, “ [njeeds that were nar

row or parochial a century ago may be interwoven in

our day with the well-being of the Nation. What

2 0

is critical or urgent changes with the times.” Hel

vering v. Davis, supra, 301 U.S. at 641.

The elimination of the effects of past or present

racial and ethnic discrimination is unquestionably a

legitimate purpose for which Congress may exercise

its spending power. The Constitution itself estab

lishes the legitimacy of such a legislative aim. The en

forcement sections of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth

Amendments authorize Congress to enact measures to

eliminate slavery and involuntary servitude and to

ensure that no state denies to any person within its

jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws. What

ever the precise scope of congressional power under

the Civil War Amendments,6 those additions to the

6 In Katzenbach V. Morgan, 384 U.S. 641, 650-651 (1966),

the Court stated that, by including Section 5, the enforce

ment section, in the Fourteenth Amendment, “the draftsmen

sought to grant to Congress * * * the same broad powers

expressed in the Necessary and Proper Clause * * *. Correctly

viewed, § 5 is a positive grant of legislative power authorizing

Congress to exercise its discretion in determining whether

and what legislation is needed to secure the guarantees of the

Fourteenth Amendment.” Similarly, in Jones V. Alfred H.

Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409, 440 (1968), the Court declared

that the enforcement section of the Thirteenth Amendment

gives Congress the power “rationally to determine what are

the badges and the incidents of slavery, and the authority to

translate that determination into effective legislation.” Con

gressional power under the Thirteenth Amendment extends to

private as well as public activity. See Runyon V. McCrary,

427 U.S. 160, 168-173 (1976) ; Johnson V. Railway Express

Agency, Inc., 421 U.S. 454, 459-460 (1975) ; Tillman V.

Wheaton Haven Recreation Assn, 410 U.S. 431, 439-440

(1973) ; Jones V. Alfred H. Mayer Co., supra. See also

United States V. Guest, 383 U.S. 745, 762 (1966) (Clark, J.,

21

Constitution plainly demonstrate that remedying the

effects of discrimination based on race or national

origin is one goal toward which Congress may prop

erly exercise each of its enumerated powers. In par

ticular, Congress may spend public funds in a man

ner designed to guarantee that the benefits of fed

eral grant programs are not denied to persons who

have suffered discrimination in the past.

In the last 20 years, Congress has enacted numer

ous statutes intended to eliminate discrimination and

its effects from federally funded programs.* 7 Congress

has also passed other antidiscrimination measures ad

dressed to different areas of public and private ac

tivity.8 The form of this legislation has varied as

concurring) ; id. at 781-782 (Brennan, J., concurring in part

and dissenting in part) (congressional power under the

Fourteenth Amendment may reach private activity).

7 The statute with the most comprehensive coverage is

Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. 2000d

et seq., which broadly prohibits discrimination on the basis

of race, color, or national origin in any program or activity

receiving federal financial assistance. Since the passage of

Title VI, many other specific federal grant statutes have

contained similar prohibitions against discrimination in par

ticular funded activities. See, e.g., State and Local Fiscal

Assistance Amendments of 1976, 31 U.S.C. 1242; Energy

Conservation and Production Act, 42 U.S.C. 6870; Housing

and Community Development Act of 1974, 42 U.S.C. 5309;

Comprehensive Employment and Training Act of 1973, 29

U.S.C. 991.

8 The congressional effort to end discrimination and its

effects began after the Civil War with the enactment of the

Civil Rights Act of 1866, 42 U.S.C. 1981 et seq. See generally

B. Schwartz, Statutory History of the United States-Civil

Rights (1970). Legislative activity has substantially increased

22

Congress has acquired experience in dealing with the

continuing problems of racial and ethnic discrimina

tion. Compare, for example, the relatively simple

provisions enacted in 1957 to protect the voting rights

of racial minorities8 9 with the elaborate procedures

established eight years later for the same purpose.10

Although many early federal statutes did not go

beyond bare prohibitions against discrimination, Con

gress is not limited to such negative commands. This

Court has sustained legislation that requires race

conscious affirmative measures to eliminate discrim

ination and its effects. See generally Regents of the

University of California v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265,

362-369 (1978) (opinion of Brennan, White, Mar

shall, and Blackmun, JJ.). For example, under

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, employers

since this Court’s decision in Brown V. Board of Education,

347 U.S. 483 (1954). See, e.g., the Civil Rights Act of 1957,

Pub. L. No. 85-315, 71 Stat. 634; the Civil Rights Act of

1964, Pub. L. No. 88-352, 78 Stat. 241; the Voting Rights Act

of 1965, Pub. L. No. 89-110, 79 Stat. 437; the Voting Rights

Act Amendments of 1970, Pub. L. No. 91-285, 84 Stat. 314;

the 1975 Amendments to the Voting Rights Act of 1965, Pub.

L. No. 94-73, 89 Stat. 400; the Fair Housing Act of 1968,

Pub. L. No. 90-284, 82 Stat. 81-90; the Equal Employment

Opportunity Act of 1972, Pub. L. No. 92-261, 86 Stat. 103;

the Equal Credit Opportunity Act, Pub. L. No. 93-495, 88

Stat. 1521; and the Equal Credit Opportunity Act Amend

ments of 1976, Pub. L. No. 94-239, 90 Stat. 251.

9 See Section 131 of the Civil Rights Act of 1957, Pub. L.

No. 85-315, 71 Stat. 637 (codified in 42 U.S.C. (1958 ed.)

1971(b )-(e)).

10 See the Voting Rights Act of 1965, Pub. L. No. 89-110,

79 Stat. 437 (codified in 42 U.S.C. (1964 ed., Supp. I ll)

1973-1973p).

23

may be required to avoid racially disparate effects of

employment tests by using racial criteria (i.e., one

passing score for blacks and another for whites)

so that tests will predict success on the job equally

well for each racial group. See Albemarle Paper

Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 435 (1975) (discussing

with approval EEOC Guidelines requiring “differen

tial validation” of employment tests for minority and

nonminority groups where technically feasible). The

Voting Rights Act of 1965 permits officials to take

race into account in apportioning legislative districts

in a way that fairly represents the voting strength

of different racial and ethnic groups. United Jewish

Organizations v. Carey, 430 U.S. 144 (1977). Guide

lines issued under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964 require “affirmative steps to rectify the lan

guage deficiency * * * [wjhere inability to speak

and understand the English language excludes na

tional origin-minority group children from effective

participation in the educational program offered by a

school district.” 35 Fed. Reg. 11595 (1970); see

Lau v. Nichols, supra, 414 U.S. at 568.

This Court has held that Congress may generalize

in identifying the victims of discrimination where,

as here, measurement of the effects of discrimination

on an individual basis is impractical or impossible.

See Gaston County v. United States, 395 U.S 285, 295-

296 (1969); Regents of the University of California

v. Bakke, supra, 438 U.S. at 377-378 (opinion of

Brennan, White, Marshall, and Blackmun, JJ.). See

also Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324, 357-

24

362 (1977). Similarly, the impact of remedial legis

lation enacted by Congress to eliminate and redress

the effects of past discrimination need not be limited to

proven discriminators. See Regents of the University

of California v. Bakke, supra, 438 U.S. at 366 (opin

ion of Brennan, White, Marshall, and Blackmun, JJ.);

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 747,

774-775, 777 (1976); Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401

U.S. 424, 430 (1971). Even if individual recipients

of financial assistance or nonminority contractors have

not themselves discriminated, Congress may require

them to adjust their conduct in order to ensure, for

example, that in the allocation of funds under the

1977 local public works program minorities do not

suffer the lingering effects of past discrimination in

the construction industry.

Katzenbach v. Morgan, 384 U.S. 641 (1966), illus

trates this point. There, the Court upheld federal

legislation prohibiting application of New York

State’s literacy requirements to citizens educated in

schools accredited by the Commonwealth of Puerto

Rico, regardless of whether the New York require

ment itself violated the Fourteenth Amendment. The

Court explained (384 U.S. at 653) that Congress, in

the exercise of its power under Section 5 of the

Fourteenth Amendment, was the proper govern

mental branch to

assess and weigh the various conflicting consid

erations—the risk or pervasiveness of the dis

crimination in governmental services, the effec

tiveness of eliminating the state restriction on

25

the right to vote as a means of dealing with the

evil, the adequacy or availability of alternative

remedies, and the nature and significance of the

state interests that would be affected by the nul

lification of the English literacy requirement as

applied to residents who have successfully com

pleted the sixth grade in a Puerto Rican school.

Morgan thus demonstrates that, when Congress has

determined that a particular measure is necessary to

remedy a Fourteenth Amendment violation or to

prevent the occurrence of such a violation (e.g., the

discriminatory denial of public services to Puerto

Ricans), the Court will not interfere and reweigh

the factors considered by Congress in reaching that

judgment, even if the legislative solution chosen ad

versely affects some state practice (e.g., the use of a

literacy test as a qualification for voting) that itself

does not necessarily violate the Fourteenth Amend

ment or any other constitutional provision. See also

United Jewish Organizations v. Carey, supra, 430 U.S.

at 161; Oregon v. Mitchell, 400 U.S. 112 (1970).

The same reasoning applies here. Congress is the

governmental body uniquely well situated to determine

which groups have suffered discrimination in the past

and what measures are most likely to prevent further

discrimination and to restore members of those groups

to the position they would have occupied had the dis

crimination not occurred. As Mr. Justice Powell ob

served in Bakke, this Court has “recognized the spe

cial competence of Congress to make findings with re

spect to the effects of identified past discrimination

26

and its discretionary authority to take appropriate

remedial measures.” 438 U.S. at 302 n.41.

Indeed, petitioners have conceded (A. 192a) that

the racial classification established by the minority

business enterprise provisions serves a compelling

governmental interest if it is intended to remedy the

effects of present or past discrimination. They argue,

however, that the legislative history of Section

103(f) (2) “fails to evince findings of prior discrimi

nation sufficient to justify upholding” a federal grant

statute that takes race and national origin into ac

count in distributing government funds (Pet. Br. 14-

21; GBC Br. 10-17).11 They also contend (Pet. Br.

21-28; GBC Br. 18-31) that, even if Congress’ pur

pose was to remedy the effects of past discrimination,

the 10% minority set-aside is an unacceptable method

of accomplishing that end, because it imposes an un

necessary burden on nonminority businesses that wish

to compete for local public works funds. We address

these arguments in turn.

B. Congress Concluded that Legislative Action Was

Necessary to Eliminate the Effects of Discrimination

in the Construction Industry

1. Inquiry into the congressional purpose underly

ing the MBE provision must begin with an apprecia

tion of the unique nature of the legislative role. While

courts decide cases and controversies on the basis of

11 “Pet. Br.” refers to the brief apparently filed by all

petitioners. “GBC Br.” refers to the brief filed by petitioner

General Building Contractors of New York State, Inc.

27

individual records, legislatures address broader prob

lems and attempt to devise solutions that extend

beyond the parties to any single dispute. As this

Court observed in Schlesinger v. Reservists Com

mittee to Stop the War, 418 U.S. 208, 221 n.10

(1974), “ [t]he legislative function is inherently gen

eral rather than particular and is not intended to be

responsive to adversaries asserting specific claims or

interests peculiar to themselves.” A legislature, un

like a court or an administrative agency, is not ob

ligated to confine its attention to the material con

tained in a record compiled for the resolution of a

particular dispute. Rather, it is empowered to make

laws on the basis of information obtained from a va

riety of sources in a variety of ways. It may rely on

the accumulated experiences of its individual members

and on its collective evaluation of the success or fail

ure of past legislative attempts to solve particular

problems. When it desires additional information, it

may conduct its own investigation unrestricted by

many of the procedural rules that govern judicial

and agency action.

These distinctive features of the legislative role,

which are, of course, rudimentary in our system of

separation of powers, bear repeating here because of

the kind of attack petitioners level against the minor

ity business enterprise provision. Petitioners assert

that Section 103(f)(2) of the Public Works Em

ployment Act is invalid because the legislative history

of the statute does not contain the “detailed findings

of constitutional or statutory violations (Pet. Br. 15)

28

allegedly necessary to justify the use of a racial classi

fication in the distribution of government benefits.

Petitioners maintain that the courts below erred by

“embark [ing] on a search outside of the legislative

record in an effort to sustain” the MBE provision (Pet.

Br. 17).

This argument is based on a false premise. By their

unstated assumption that congressional policy de

cisions must stand or fall on the basis of a limited col

lection of materials known as the “legislative record,”

petitioners cast Congress in the role of an administra

tive agency whose actions are subject to judicial re

view under something akin to the “substantial evi

dence” standard. Petitioners’ challenge to the MBE

provision thus rests on a fundamental misconception

of Congress’ place in our constitutional system. Con

trary to petitioners’ apparent belief, Congress may

legislate on the basis of everything it knows about

a particular situation, and it need not record every—

or even any—element of factual support for a bill in

the accompanying committee reports or in the course

of floor debates.12 Specific findings that a proposed

remedial measure will assist only those who have suf

fered injury in the past and will adversely affect only

those who have caused such injury are not necessary.

“Congress may paint with a much broader brush.”

Oregon v. Mitchell, 400 U.S. 112, 284 (1970) (Stew

art, J., concurring in part and dissenting in part).

12 Indeed, neither committee consideration nor floor debate

is required at all in order for a bill to be validly enacted into

law under the procedures prescribed by Article I of the

Constitution.

29

Because Congress is engaged in the business of

framing general rules for the governance of society,

not the resolution of individual disputes, judicial re

view of a federal statute proceeds differently from re

view of agency action. An agency ordinarily must

state the reasons for its action in the administrative

record, and if a reviewing court finds those reasons

deficient, it will normally reverse and remand for

further proceedings without examining other possible

justifications for the agency’s decision; this is often

true even where the additional or alternative reasons

for agency action are known to the court and sup

ported by extra-record material. See SEC v. Chenery

Corp., 318 U.S. 80 (1943). By contrast, in its efforts

to ascertain legislative purpose on review of a federal

statute, a court need not restrict its vision to the con

tents of a legislative record compiled by Congress.

A court may look not only to the statute’s legislative

history, narrowly defined, but also to the language of

the statute, its relationship with other federal laws,

and any other available materials that may explain

the congressional decision to adopt a particular

measure.

To be sure, when a statutory provision involves a

racial classification, a reviewing court must take spe

cial care in satisfying itself that the congressional

purpose underlying the provision is legitimate and

compelling.13 But this does not mean that the court

13 As four members of the Court stated in Bakke, “because

of the significant risk that racial classifications established

30

must limit its attention to a discrete body of materials

labelled the “legislative record.” On the contrary, the

court may and should consider all sources of infor

mation concerning the reasons for congressional ac

tion. Statutes involving racial classifications are, in

this respect, no different from any others. Legislative

purpose may be found in any materials that tend

to reveal the reasons for a statute’s enactment.14 Cf.

for ostensibly benign purposes can be misused, * * * it is

inappropriate to inquire only whether there is any con

ceivable basis that might sustain such a classification. In

stead, to justify such a classification an important and artic

ulated purpose for its use must be shown.” 438 U.S. at 361

(opinion of Brennan, White, Marshall, and Blackmun, JJ .).

Contrary to petitioners’ contention (Pet. Br. 12 & n.4, 15

n.6), this statement was not intended to suggest that a statu

tory racial classification can never be sustained unless Con

gress includes in the “legislative record” specific findings of

past discrimination and an explicit declaration that the

statute’s purpose is to remedy that discrimination. Indeed,

the four members of the Court who joined the statement

would have upheld the admissions program employed by the

Medical School of the University of California at Davis, even

though, as Mr. Justice Powell observed, the racial classifica

tion used in that program was not supported by any “deter

mination by the legislature or a responsible administrative

agency that the University engaged in a discriminatory prac

tice requiring remedial efforts.” 438 U.S. at 305. See also

id. at 305-310. A fortiori here, where Congress has identified

a history of discrimination in the construction industry and

has enacted the MBE provision in response to that back

ground, the constitutionality of the statute’s reliance on

minority ownership as a distinguishing factor for potential

contractors in federally funded public works projects should

be sustained.

14 A different rule, such as the one advocated by petitioners,

would encumber the legislative process in ways not required

31

Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Hous

ing Development Corp., 429 U.S. 252, 266-268 (1977);

by, and arguably inconsistent with, Article I of the Consti

tution. An obligation to make a thorough “legislative record”

for each statute would severely hamper Congress’ ability to

perform its lawmaking function, but would not contribute

significantly to either the quality of the final legislative prod

uct or the reliability of the information available to a court

on judicial review. Committee staffs presumably would be

assigned the task of inserting voluminous prepared materials

into the “legislative record” in order to ensure that a review

ing court would find a sufficient factual basis for congres

sional action. No substantive benefit would accrue to the

lawmakers’ empirical knowledge or their deliberative proc

esses, but Congress might often be disabled, for practical

purposes, from making eleventh-hour changes in proposed

bills to reflect the realities of political compromise. The need

to compile a “legislative record” adequate to survive the kind

of judicial review contemplated by petitioners would in

evitably reduce the usefulness of important legislative de

vices such as the floor amendment, through which Congress

can adjust proposed statutory language in response to con

cerns raised during general debate and can thereby better

fulfill its representative role.

This Court’s decisions show that measures first advanced

as floor amendments do not fail because of inadequate con

temporaneous statements of legislative purpose. In Katzen-

bach v. Morgan, supra, for example, the Court sustained

Section 4(e) of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, despite Con

gress’ failure explicitly to declare the reasons for the statute’s

adoption. The Court examined the information known to

Congress in order to determine whether there was a sufficient

basis for the exercise of legislative power. See 384 U.S. at

651-656. Section 4(e) was a floor amendment to the Act,

and the committee hearings and reports therefore did not

refer to the provision. 384 U.S. at 669 n.9 (Harlan, J., dissent

ing). See also Heart of Atlanta Motel v. United States, 379

U.S. 241, 252 (1964) ; Katzenbach V. McClung, 379 U.S. 294,

299 (1964).

32

Califano v. Goldfarb, 430 U.S. 199, 212-217 (1977);

Califano v. Webster, 430 U.S. 313, 316-321 (1977).

2. Applying these principles of judicial review,

the district court and court of appeals in the present

case correctly concluded that Congress added the

MBE provision to the Public Works Employment Act

of 1976 in order to remedy the effects of discrimination

against minority-owned businesses. Of course, the pri

mary aim of the Act as a whole (and its predeces

sor, the Local Public Works Capital Development and

Investment Act of 1976) was to stimulate the national

economy and especially the sagging construction in

dustry. Unemployment in the industry was high, and

Congress hoped that grants for local public works

programs would generate construction jobs that would

in turn induce a more widespread economic revival.

S. Rep. No. 95-38, 95th Cong., 1st Sess. 1-2 (1977) ;

H.R. Rep. No. 95-20, 95th Cong., 1st Sess. 1-2 (1977);

A. 35a-44a, 188a & n.6. But those overall aims of the

Act do not imply that Congress had no further pur

pose for enacting particular provisions in the statute.

To the contrary, the available evidence demonstrates

that the MBE provision was intended to redress past

discrimination against black and other minority con

tractors, while at the same time contributing to the

general congressional goal of “target[ing] the Federal

assistance more accurately into the areas of greatest

need.” H.R. Rep. No. 95-20, supra, at 2.

When Congress enacted the MBE provision, it

knew that the unemployment rate among minority

workers was twice as high as that among nonminor

33

ity workers. See 123 Cong. Rec. S3910 (daily ed.

Mar. 10, 1977) (remarks of Sen. Brooke); id. at

H1423 (daily ed. Feb. 24, 1977) (remarks of Rep.

Stokes). Public Works Employment Act of 1977:

Hearings Before the Subcomm. on Regional and Com

munity Development of the Senate Comm, on Envi

ronment and Public Works 95th Cong., 1st Sess. 110,

137, 155, 401 (1977). Congress also knew that un

employment in the minority construction sector was

particularly severe. 123 Cong. Rec. H1423 (daily

ed. Feb. 24, 1977) (remarks of Rep. Stokes). More

over, Congress acted against the backdrop of more

than two decades of legislative efforts to end racial

and ethnic discrimination in the market place and to

remedy the effects of discrimination against minori

ties.15 16 Experience with these earlier efforts gave Con

gress a broad perspective on the deep-seated nature

of the problems encountered by minorities as a result

of past discrimination in this country. As the court

of appeals held in rejecting petitioners’ argument

that the MBE provision was not intended to remedy

discrimination (A. 215a-216a, footnote omitted),

[i]n view of the comprehensive legislation which

Congress has enacted during the past decade and

15 The term “minority” as used in the MBE provision

refers to American citizens who are Negroes, Spanish-

speaking, Orientals, Indians, Eskimos, or Aleuts. Before the

enactment of the MBE provision, this definition had been

used in federal affirmative action efforts under regulations

concerning the procurement of government supplies and the

performance of government contracts. See, e.g., 41 C.F.R.

1-1.1302, 1-1.1303, 1-1.1310-2.

34

a half for the benefit of those minorities who

have been victims of past discrimination, any

purpose Congress might have had other than to

remedy the effects of past discrimination is dif

ficult to imagine.

See also Constructors Ass’n of Western Pennsyl

vania v. Kreps, 573 F.2d 811, 817 (3d Cir. 1978);

Rhode Island Chapter, Associated General Contrac

tors of America v. Kreps, 450 F. Supp. 338 (D. R.I.

1978). Cf. Regents of the University of California

v. Bakke, supra, 438 U.S. at 348-349 (opinion of

Brennan, White, Marshall, and Blackmun, 3J.).

Many times during the last 10 years, Congress has

given specific attention to the problems encountered

by minority-owned businesses,18 and has enacted leg- 16

16 See, e.g., Review of Small Business Administration’s

Programs and Policies—1971: Hearings Before the Senate

Select Comm, on Small Business, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. 283-

284 (1971) ; Government Minority Small Business Programs:

Hearings Before the Subcomm. on Minority Small Business

Enterprise of the House Select Comm, on Small Business,

92d Cong., 1st Sess. (1971) ; Government Minority Enterprise

Programs—Fiscal Year 197A: Hearings Before the Subcomm.

on Minority Small Business Enterprise and Franchising of

the House Permanent Select Comm, on Small Business, 93d

Cong., 1st Sess. (1973) ; Minority Enterprise and Allied

Problems of Small Business: Hearings Before the Subcomm.

on SBA Oversight and Minority Enterprise of the House

Comm, on Small Business, 94th Cong., 1st Sess. (1975), and

the related report, H.R. Rep. No, 94-468, 94th Cong., 1st Sess.

(1975) ; The Effects of Government Regulations on Small

Business and the Problems of Women and Minorities in

Small Business in the Southwestern United States: Hearing

Before the Senate Select Comm, on Small Business, 94th

Cong., 2d Sess. (1976) ; Minority Business Development Ad

35

islation designed to remedy these problems.17 When