Correspondence from Kelley and Krasicky to Clerk

Public Court Documents

July 3, 1972

1 page

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Correspondence from Kelley and Krasicky to Clerk, 1972. f507461f-53e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1a37b794-7e00-45f8-9827-6f15d52fc2ea/correspondence-from-kelley-and-krasicky-to-clerk. Accessed February 03, 2026.

Copied!

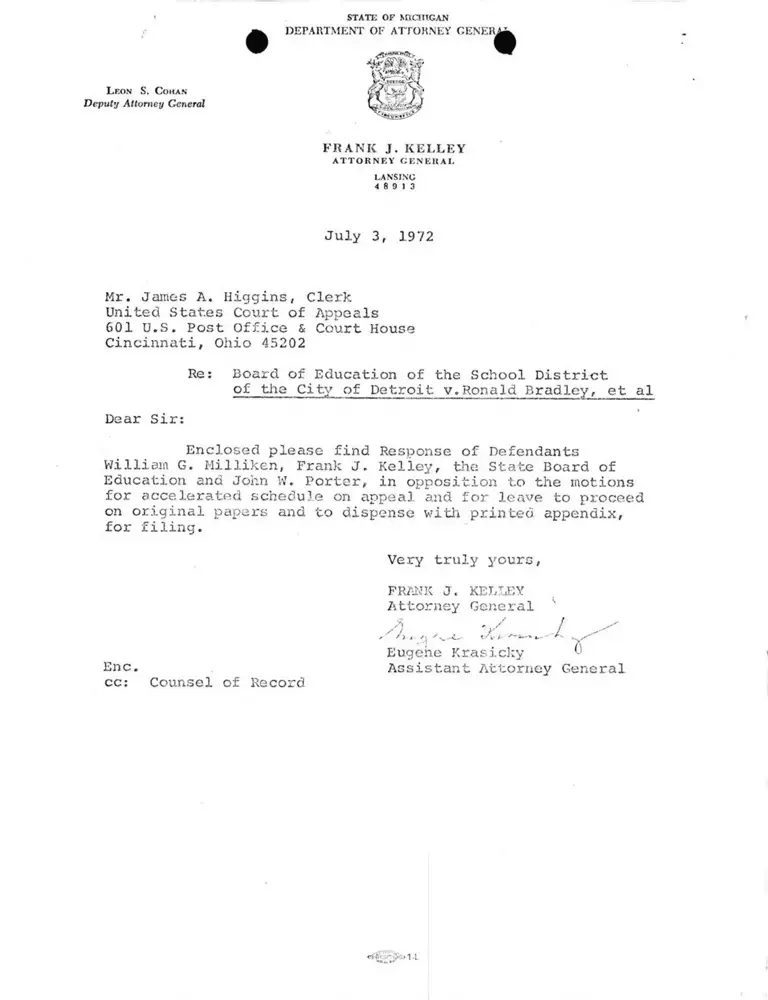

L eon S. C oh an

Deputy Attorney General

STATE OF MICHIGAN

DEPARTMENT OF ATrOKNEY GENER1

F R A N K J. K E L L E Y

A T T O R N E Y G E N E R A L

LANSING

4 8 9 1 3

J u ly 3, 1972

Mr. James A. H ig g in s , C lerk

U nited S ta te s Court o f A ppeals

601 U.S. P o s t O f f i c e & C ourt House

C in c in n a t i , Ohio 45202

Re: Board o f E d u ca tion o f the S ch o o l D i s t r i c t

o f the C ity o f D etro i t v .R o nald Br a d le y , e t a l

Dear S i r :

E n c lo s e d p le a s e f i n d Response o f Defendants

W ill ia m G. M i l l ik e n , Frank J . K e l l e y , the S ta te Board o f

E d u ca tion and John W. P o r t e r , in o p p o s i t i o n t o th e m otions

f o r a c c e l e r a t e d s ch e d u le on appeal, and f o r le a v e to p r o c e e d

on o r i g i n a l papers and t o d isp e n s e w ith p r in t e d ap pen d ix ,

f o r f i l i n g .

Enc.

Very t r u ly y o u r s ,

FRANK J. KELLEY

A tto rn e y G enera l

S I

* ' ' i t C v V 1-- a -

Eu.gehe K ra s ick y

A s s i s t a n t A tto rn e y G en era l

c c : C ounsel o f R ecord