Complaint, Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law

Public Court Documents

42 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Complaint, Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law, ae201608-54e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1a38dde5-7c3d-44ec-b7c7-5d97ba9fa9b4/complaint-findings-of-fact-and-conclusions-of-law. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

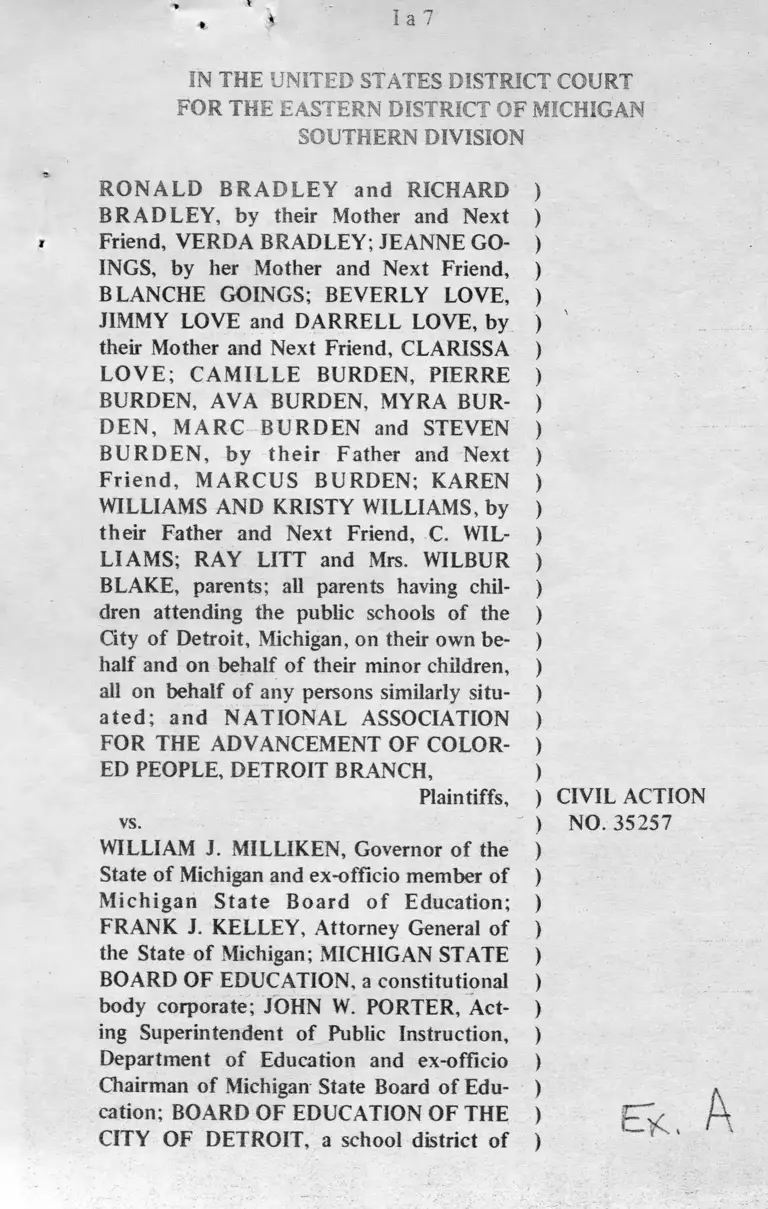

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

SOUTHERN DIVISION

RONALD BRADLEY and RICHARD

BRADLEY, by their Mother and Next

Friend, VERDA BRADLEY; JEANNE GO

INGS, by her Mother and Next Friend,

BLANCHE GOINGS; BEVERLY LOVE,

JIMMY LOVE and DARRELL LOVE, by

their Mother and Next Friend, CLARISSA

LOVE; CAMILLE BURDEN, PIERRE

BURDEN, AVA BURDEN, MYRA BUR

DEN, MARC BURDEN and STEVEN

BURDEN, by th e ir Father and Next

F rien d , MARCUS BURDEN; KAREN

WILLIAMS AND KRISTY WILLIAMS, by

their Father and Next Friend, C. WIL

LIAMS; RAY LITT and Mrs. WILBUR

BLAKE, parents; all parents having chil

dren attending the public schools of the

City of Detroit, Michigan, on their own be

half and on behalf of their minor children,

all on behalf of any persons similarly situ

a ted ; and NATIONAL ASSOCIATION

FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLOR

ED PEOPLE, DETROIT BRANCH,

Plaintiffs,

vs.

WILLIAM J. MILLIKEN, Governor of the

State of Michigan and ex-officio member of

M ichigan S ta te Board o f Education;

FRANK J. KELLEY, Attorney General of

the State of Michigan; MICHIGAN STATE

BOARD OF EDUCATION, a constitutional

body corporate; JOHN W. PORTER, Act

ing Superintendent of Public Instruction,

Department of Education and ex-officio

Chairman of Michigan State Board of Edu

cation; BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE

CITY OF DETROIT, a school district of

)

)

)

)

)

) '

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

) CIVIL ACTION

) NO. 35257

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

the first class; PATRICK McDONALD, )

JAMES HATHAWAY and CORNELIUS )

GOLIGHTLY, members of the Board of )

Education of the City of Detroit; and )

NORMAN DRACHLER, Superintendent of )

the Detroit Public Schools, )

Defendants.

C O M P L A I N T

I.

The jurisdication of this Court is invoked under 28 U.S.C.

Sections 1331(a), 1343(3) and (4), this being a suit in equity

authorized by 42 U.S.C. Sections 1983, 1988 and 2000d, to re

dress the deprivation under color of Michigan law, statute, custom

and/or usage of rights, privileges and immunities guaranteed by the

Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution of

the United States. This action is also authorized by 42 U.S.C. Sec

tion 1981 which provides that all persons within the jurisdiction

of the United States shall have the same rights to the full and

equal benefits of all laws and proceedings for the security of per

sons and property as is enjoyed by white citizens. Jurisdiction is

further invoked under 28 U.S.C. Sections 2201 and 2202, this be

ing a suit for declaratory judgment declaring certain portions of

Act No. 48 of the Michigan Public Acts of 1970 (a copy of which

is attached hereto as Exhibit A) unconstitutional. This is also an

action for injunctive relief against the enforcement of certain por

tions of said Act No. 48 and to require the operation of the

Detroit, Michigan public schools on a unitary basis.

II.

Plaintiffs, Ronald Bradley and Richard Bradley, by their

Mother and Next Friend, Verda Bradley; Jeanne Goings, by her

Mother and Next Friend, Blanche Goings; Beverly Love, Jimmy

Love and Darrell Love, by their Mother and Next Friend, Clarissa

Love; Camille Burden, Pierre Burden, Ava Burden, Myra Burden,

Marc Burden and Steven Burden, by their Father and Next Friend,

I a 9

Marcus Burden; Karen Williams and Kristy Williams, by their

Father and Next Friend, C. Williams; Ray Litt and Mrs. Wilbur

Blake, parents, are all parents or minor children thereof attending

‘-schools in the Detroit, Michigan public school system. All of the

above-named plaintiffs are black except Ray Litt, who is white

t and who joins with them to bring this action each in their own

behalf and on behalf of their minor children and all persons simi

larly situated.

P la in tiff , National Association for the Advancement of

Colored People, Detroit Branch, is an unincorporated association

with offices at 242 East Warren Avenue, Detroit, Michigan, which

sues on behalf of its membership who are members of the plaintiff

class. Plaintiff, N.A.A.C.P., has as one of its purposes the advance

ment of equal educational opportunities through the provision of

integrated student bodies, faculty and staff.

III.

Plaintiffs, pursuant to Rule 23 of the Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure, bring this action on their own behalf and on behalf of

all persons in the City of Detroit similarly situated. There are com

mon questions of law and fact affecting the rights of plaintiffs and

the rights of the members of the class. The members of the class

are so numerous as to make it impracticable to bring them all be

fore the Court. A common declaratory and injunctive relief is

sought and plaintiffs adequately represent the interests of the

members of the class.

IV.

The defendants are:

1. William J. Milliken, Governor of the State of Michigan

and ex-officio member of the State Board of Education;

2. F rank J. Kelley. Attorney General of the State of

Michigan, who is responsible for enforcing the public acts and laws

of the State of Michigan;

l a 10

3. The Michigan State Board of Education, a constitutional

body corporate, which is generally charged with the power and re

sponsibility of administering the public school system in the State

of Michigan, including the City of Detroit;

4. John W. Porter, Acting Superintendent of Public Instruc

tion, Department of Education, in the State of Michigan, and ex-

officio member of the State Board of Education;

5. The Board of Education of the City of Detroit, a school

district of the first class, organized and existing in Wayne County,

Michigan, under and pursuant to the laws of the State of Michigan

and operating the public school system in the City of Detroit

Michigan;

6. P a trick M cD onald, James Hathaway and Cornelius

Golightly, all residents of Wayne County, Michigan, and elected

members of the Board of Education of the City of Detroit;

7. The remaining board members of the Board of Education

of the City of Detroit;

8. Norman Drachler, a resident of Wayne County, Michigan,

and the appointed Superintendent of the Detroit Public Schools.

V.

Plaintiffs seek a declaratory judgment declaring the last sen

tence of the first paragraph of Section 2a and the entirety of Sec

tion 12 of Public Act No. 48 of the Michigan Public Acts of 1970

unconstitutional.

The challenged portion of Section 2a reads as follows:

Regions shall be as compact, contiguous and nearly equal as

practicable.

Section 1 2 reads as follows:

The implementation of any attendance provisions for the

I a 11

>

1970-71 school year determined by any first class school dis

trict board shall be delayed pending the date of commence

ment of functions by the first class school district boards

established under the provisions of this amendatory act but

such provision shall not impair the right of any such board to

determine and implement prior to such date such changes in

attendance provisions as are mandated by practical necessity.

In reviewing, confirming, establishing or modifying atten

dance provisions the first class school district boards esta

blished under the provisions of this amendatory act shall have

a policy of open enrollment and shall enable students to

attend a school of preference but providing priority accep

tance, insofar as practicable, in cases of insufficient school

capacity, to those students residing nearest the school and to

those students desiring to attend the school for participation

in vocationally oriented courses or other specialized curri

culum.

Plaintiffs also seek a temporary restraining order and pre

liminary and permanent injunctions against the enforcement of

said provisions of Act 48.

VI.

This is also a proceeding for a permanent injunction enjoining

the defendant, Board of Education of the City of Detroit, its

members and the Superintendent of Schools from continuing their

policy, practice, custom and usage of operating the public school

system in and for the City of Detroit, Michigan in a manner which

has the purpose and effect of perpetuating a biracial segregated

public school system, and for other relief, as hereinafter more

fully appears.

VII.

On August 11, 1969, the Governor of the State of Michigan

approved Act No. 244 of the Public Acts of 1969 (Mich. Stats.

Ann. Section 15.2298), said Act being entitled, “AN ACT to re

quire first class school districts to be divided into regional districts

and to provide for local district school boards and to define their

9-

powers and duties and the powers and duties of the first class dis

trict board.” (A copy of Act No. 244 is attached hereto as Exhibit

B). Act No. 244 applies exclusively to the Board of Education of

the School District of the City of Detroit, that being the only first

class school district in the State of Michigan. The essence of Act

a

No. 244 is that it provides the mandate and means for the admini

strative decentralization of the Detroit school system and the ex

tent thereof.

On March 2, 1970, the Detroit School Board’s attorney ren

dered an opinion (attached hereto as Exhibit C) advising the Board

that in effectuating decentralization under Act No. 244 the law

imposed three limitations:

1. The Act itself required each district to have not less than

25,000 nor more than 50,000 pupils;

2. The United States Constitution required each district to

be in compliance with the “one man, one vote” principle;

3. The United States Constitution, above all, required that

the districts be established on a racially desegregated basis.

VIII.

In the 1969-70 school year, the Detroit Board of Education

operated 21 high school constellations providing a public educa

tion for 281,101 school children (excluding 12,758 students not

listed in high school constellations and in adult programs). 61.9%

of these students were Negro, 36.4% were white, and 1.7% were of

other racial-ethnic minorities. Of the 21 high school constellations

operated by the Detroit School Board in 1969-70, 14 were racially

identifiable as “ white” or “Negro” constellations. The high school

constellations contain within them 208 elementary schools, 53

junior high schools, and 21 senior high schools. Of the 208 ele

mentary schools (enrolling 166,258 pupils), 114 (enrolling 92,225

pupils) are identifiable as “Negro” schools and 71 (enrolling

46,448 pupils) are identifiable as “ white” schools. Of the 53

junior high schools (enrolling 63,476 pupils), 24 (enrolling 31,201

pupils) are identifiable as “ Negro” schools and 18 (enrolling

la 12

I a 13

21,507 pupils) are identifiable as “white” schools. Of the 21

senior high schools (enrolling 54,394 pupils, 11 (enrolling 25,351

pupils) are identifiable as “Negro” schools and 6 (enrolling 19,183

pupils) are identifiable as “white” schools.

IX.

On April 7, 1970, the Detroit Board of Education adopted a

limited plan of desegregation (Exhibit D, attached hereto) for the

senior high school level, which plan was to take effect on a stair

step basis over a period of four years so that by 1972, there

would be substantially increased racial integration. This plan for

high school desegregation comtemplated a change in high school

boundary lines, thereby changing the junior high feeder patterns in

twelve of Detroit’s 21 senior high schools.. The plan was designed

so that by the year 1972. only three (as compared to the present

17) of Detroit’s senior high schools would be racially identifiable

as “ Negro” or “ white” high schools. The plan also provided that a

student presently enrolled in a junior high school and who has a

brother or sister presently enrolled in a senior high school would

continue in senior high school at the school his brother or sister

was presently attending. All those presently enrolled in senior high

school would not, due to the stair-step feature of the plan, be

affected and they would continue through graduation at the segre

gated senior high school they were presently attending. The April

7 plan did not involve, nor did it affect, the existing racially segre

gated pattern of pupil assignments in the elementary and junior

high schools.

X.

On April 7, 1970, the Detroit Board of Education by a four-

to-two vote (the seventh member, now deceased, expressing his

approval by letter from his hospital bed) adopted a regional

boundary plan (attached hereto as Exhibit D) for administrative

decentralization consisting of --men regions. The seven regions as

established by the Board on April 7.1970 contained an average of

38,802 pupils per region with the smallest region containing

33,043 pupils and the largest region containing 46,592 pupils, or a

range of deviation of 13.549 pupils with an average deviation of

I a i 4♦

2,892 pupils per region. The racial complexion of the pupil enroll

ment in the seven regions averaged 61.7% Negro with the lowest

percent Negro region being 34.4% and the largest percent Negro

. region being 76.7%, or a range of deviation of 42.3% Negro with

an average regional deviation of 10.5% Negro.

XI.

The actions of the Detroit School Board on April 7, 1970

approv ing a desegregation plan resulted in expressions of

“ community hostility” . A movement to recall the four members

of the Detroit School Board who voted in favor of the April 7,

1970 action was initiated by white citizens. The recall movement

was resolved by the Detroit voters (of which a majority are white)

at the August 4, 1970 election, which resulted in the removal of

the four board members who had voted in favor of the April 7,

1970 plan. The April 7th plan created a similar reaction in the

Michigan State Legislature which culminated in the passage of

Public Act 48, interposing the State and voiding the partial dese

g regation plan, which Act was approved by the defendant,

Governor Milliken, on July 7, 1970.

XII.

On July 28, 1970, the attorney for the Detroit Board of

Education rendered an opinion (attached hereto as Exhibit E) that

Act 48 has both the design and the effect of completely elimi

nating the provisions of the April 7th plan adopted by the Board.

Section 2a of the Act provides that “ [rjegions shall be as com

pact, contiguous and nearly equal in population as practicable.”

This provision was intended to and does eliminate the efforts of

the Board on April 7, 1970 to create racially integrated regions.

Section 1 2 of Act 48 eliminates all provisions of the Board’s April

7th plan aimed at desegregation of the Detroit public schools by,

first, delaying the implementation of the attendance provisions

until January 1, 1971 and, second, by mandating an open enroll

ment (“ freedom of choice” ) policy qualified only by a provision

providing students residing nearest a school with an attendance

priority over those residing farther away. Section 1 2 has the fur

ther effect of eliminating two policies of the Detroit Board of

I a 15

Education: (1) prior to the adoption of Act 48, a student could

transfer to a school other than the one to which he was initially

assigned only if his transfer would have the effect of increasing

desegregation in the Detroit school system; (2) prior to the adop

tion of Act 48, whenever pupils had to be bused to relieve over

crowding, they were transported to the first and nearest school

where their entry would increase desegregation.

XIII.

Pursuant to the provisions of Section 2a of Act 48, the defen

dant, Governor William G. Milliken, on July 22, 1970 appointed a

three-member commission known hereafter as the Detroit Boun

dary Line Commission to draw the boundary lines for the eight

public school election regions mandated by Act 48. On August 4,

1970 the Detroit Boundary Line Commission adopted its plan and

presented its boundary lines for the eight election regions as called

for in Act 48. The Boundary Line Commission’s August 4th plan

(a copy of which is attached hereto as Exhibit F) is a complete

negation of the Board’s April 7th region plan. The August 4th plan

creates eight regions with an average of 33,582 pupils in each

region with a range of deviation of 19,942 (the largest region con

tains 43,025 pupils while the smallest region contains 23,083) and

an average deviation for each region of 22.9%. Under the plan

adopted by the Detroit Boundary Line Commission on August 4,

3 970, there will be new racially segregated school regions estab

lished in the defendant school system.

XIV.

Section 12 of the Act was enacted with the express intent of

preventing the desegregation of the defendant system. It applies to

but one school district in the State and reestablishes a policy

found by the United States Supreme Court to be an inadequate

method for elimination of segregated school attendance patterns.

It seeks to reverse a finding of the United States District Court for

the Eastern District of Michigan in Sherrill School Parents Com

mittee v. The Board o f Ed. o f the School District o f the City o f

Detroit, Michigan, No. 22092, E.D. Mich. Sept. 18, 1964, that the

“Open School” program does not appear to be achieving substan-

I a 16

tial student integration in the Detroit School System presently or

within the foreseeable future.

XV.

Plaintiffs allege that in the premises Public Act 48 on its face

and as applied violates the Fourteenth Amendment to the Consti

tution of the United States; the Act pertains solely to the Detroit

Board of Education and thereby deliberately prohibits the Detroit

Board of Education from making pupil assignments and estab

lishing pupil attendance zones in a manner which all other school

districts in the State of Michigan are free to do. Public Act 48

thereby creates an irrational, unreasonable and arbitrary classifi

cation which contravenes the equal protection and due process

clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment. The distinction made by

Public Act 48 is further unconstitutional by the fact that it applies

solely to the Detroit school district where the bulk of Negro

school children in the State of Michigan are concentrated.

XVI.

Public Act 48 further violates the Fourteenth Amendment to

the United States Constitution in that the Act impedes the legally

mandated integration of the public schools; the effect of the Act is

to perpetuate the segregation and racial isolation of the past and

give it the stamp of legislative approval. The Act, building upon

the preexisting public and private housing segregation, has the pur

pose, intent and effect of intensifying the present segregation and

racial isolation in the Detroit public schools. The Act further vio

lates the Fourteenth Amendment in that it constitutes a reversal

by the State of Michigan of action taken by the Detroit School

Board which action was consistent with and mandated by the Con

stitution of the United States. In addition, Public Act 48 infringes

upon the Thirteenth Amendment in that its effect is to relegate

Negro school children in the City of Detroit to a position of

inferiority and to assert the inferiority of Negroes generally, there

by creating and perpetuating badges and incidents of slavery; and,

also, in that it denies to black persons in Detroit the same rights to

the full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings as white

citizens enjoy.

l a 17

XVII.

The defendants, Board of Education of the City of Detroit

and Michigan State Board of Education, are charged under

Michigan law and the Constitution and laws of the United States

with the responsibility of operating a unitary public school system

in the City of Detroit, Michigan.

XVIII.

Plaintiffs allege that they are being denied equal educational

opportunities by the defendants because of the segregated pattern

of pupil assignments and the racial identifiability of the schools in

the Detroit public school system. Plaintiffs further allege that said

denials of equal educational opportunities contravene and abridge

their rights as secured by the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amend

ments to the Constitution of the United States.

XIX.

The plaintiffs allege that the defendants herein, acting under

color of the laws of the State of Michigan, have pursued and are

presently pursuing a policy, custom, practice and usage of oper

ating, managing and controlling the said public school system in a

manner that has the purpose and effect of perpetuating a segre

gated public school system. This segregated public school system is

based predominantly upon the race and color of the students

attending said school system: attendance at the various schools is

based upon race and color; and the assignment of personnel has in

the past and remains to an extent based upon the race and color of

the children attending the paiticular school and the race and color

of the personnel to be assigned.

XX.

The plaintiffs allege that the racially discriminatory policy,

custom, practice and usage described in paragraph XIX has in

cluded assigning students, designing attendance zones for elemen

tary junior and senior high schools, establishing feeder patterns to

secondary schools, planning future public educational facilities.

l a 18

constructing new schools, and utilizing or building upon the

existing racially discriminatory patterns in both public and private

housing on the basis of the race and color of the children who are

‘eligible to attend said schools. The said discriminatory policy, cus

tom, practice, and usage has resulted in a public school system

> composed of schools which are either attended solely or pre

dominantly by black students or attended solely or predominantly

by white students.

XXI.

The plaintiffs allege that the racially discriminatory' policy,

custom, practice and usage described in paragraph XIX has also

included assigning faculty and staff members employed by defen

dants to the various schools in the Detroit school system on the

basis of the race and color of the personnel to be assigned. Conse

quently, a general practice has developed whereby white faculty

and staff members have been assigned on the basis of their race

and color to schools attended solely or predominantly by white

students and Negro faculty and staff members have been assigned

on the basis of their race and color to schools attended solely or

predominantly by black students.

xxn.

The defendants have failed and refused to take all necessary

steps to correct the effects of their policy, practice, custom and

usage of racial discrimination in the operation of said school

system and to insure that such policy, custom, practice and usage

for the 1970-71 school year, and thereafter, will conform to the

requirements of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments.

XXIII.

Plaintiffs and those similarly situated and affected on whose

behalf this action is brought are suffering irreparable injury and

will continue to suffer irreparable injury by reason of the pro

visions of the Act complained of herein and by reason of the

failure or refusal of defendants to operate a unitary school system

in the City of Detroit. Plaintiffs have no plain, adequate or com-

l a 19

plete remedy to redress the wrongs complained of herein other

than this action for declaratory judgment and injunctive relief.

Any other remedy to which plaintiffs could be remitted would be

'attended by such uncertainties and delays as to deny substantial

relief, would involve a multiplicity of suits and would cause fur

ther irreparable injury. The aid of this Court is necessary in

* assuring the citizens of Detroit and particularly the black public

school children of the City of Detroit that this is truly a nation of

laws, not of men, and that the promises made by the Thirteenth

and Fourteenth Amendments are and will be kept.

WHEREFORE, plaintiffs respectfully pray that upon the

Filing of this complaint the Court:

1. Issue, pendente life, a temporary restraining order and a

preliminary injunction:

a. Requiring defendants, their agents and other persons

acting in concert with them to put into effect the partial plan

of senior high school desegregation adopted by the defendant,

Detroit Board of Education, on April 7, 1970, which plan

called for its implementation at the start of the 1970-71

school term, provided, however: (1) that the plan shall not be

e ffec ted on a stair-step basis, but shall, in accord with

Alexander v. Holmes County Board, 396 U.S. 19 (1969), be

come completely and fully effective at the beginning of the

coming (1970-71) school year; and (2) that those provisions

which exclude a pupil who has a brother or sister presently

enrolled in a senior high school from being affected by the

plan shall be deleted in accord with Ross v. Dyer, 312 F.2d

191 (5th Cir. 1963);

b. Restraining defendants, their agents and other per

sons acting in concert with them from giving any force or

effect to Sec. 1 2 of Act No. 48 of the Michigan Public Acts of

1970 insofar as its application would impair or delay the dese

gregation of the defendant system;

c. Restraining defendants from taking any steps to

implement the August 4, 1970 plan, or any other plan, for

I a 20

new district or regional boundaries pursuant to Act 48, or

from taking any action which would prevent or impair the

, im p le m e n ta tio n o f the regions established under the

defendant Board’s earlier plan which provided for non-racially

identifiable regions;

d. Restraining defendants from all further school con

s t r uc t i on until such t ime as a constitutional plan for

operation of the Detroit public schools has been approved and

new construction reevaluated as a part thereof;

e. Requiring defendants to assign by the beginning of

the 1970-71 school year principals, faculty, and other school

personnel to each school in the system in accordance with the

ratio of white and black principals, faculty and other school

personnel throughout the system.

2. Advance this cause on the docket and order a speedy

hearing of this action according to law and upon such hearing:

a. Enter a judgment declaring the provisions of Act No.

48 complained of herein unconstitutional on their face and as

applied as violative of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amend

ments to the United States Constitution;

b. Enter preliminary and permanent decrees perpetu

ating the orders previously entered;

c. Enter a decree enjoining defendants, their agen

employees and successors from continuing to employ policies,

customs, practices and usages which, as described herein

above, have the purpose and effect of leaving intact racially

identifiable schools;

d. Enter a decree enjoining defendants, their agents,

employees and successors from assigning students and/or

operating the Detroit school system in a manner which re

sults in students attending racially identifiable public schools;

e. Enter a decree requiring defendants, their agents.

I a 213?

employees and successors to assign teachers, principals and

other school personnel to schools to eliminate the racial

identity of schools by assigning such personnel to each school

in accordance with the ratio of white and black personnel

throughout the system.

f. Enter a decree enjoining defendants, their agents,

employees and successors from approving budgets, making

available funds, approving employment and construction con

tracts, locating schools or school additions geographically, and

approving policies, curriculum and programs, which are de

signed to or have the effect of maintaining, perpetuating or

supporting racial segregation in the Detroit school system.

g. Enter a decree directing defendants to present a com

plete plan to be effective for the 1970-71 school year for the

elimination of the racial identity of every school in the system

and to maintain now and hereafter a unitary, nonracial school

system. Such a plan should include the utilization of all

methods of integration of schools including rezoning, pairing,

grouping, school consolidation, use of satellite zones, and

transportation.

h. Plaintiffs pray that the Court enjoin all further con

struction until such time as a constitutional plan has been

approved and new construction reevaluated as a part thereof.

i. Plaintiffs pray that this Court will award reasonable

counsel fees to their attorneys for services rendered and to be

rendered them in this cause and allow them all out-of-pocket

expenses of this action and such other and additional relief as

may appear to the Court to be equitable and just.

Respectfully submitted,

Nathaniel Jones, General Counsel

N.A.A.C.P.

1790 Broadway

New York, New York

Louis R. Lucas

Ratner, Sugarmon & Lucas

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee

Bruce Miller and

Lucille Watts, Attorneys for

Legal Redress Committee

N.A.A.C.P., Detroit Branch

3426 Cadillac Towers

Detroit, Michigan, and

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

*

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

SOUTHERN DIVISION

I a 497

RONALD BRADLEY, et al., j

Plaintiffs j

)

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al., j

Defendants )

and |

DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS,)* ^ ^ * * * V 1 , p t v t i A P T JO N ISin

LOCAL 231, AMERICAN FEDERA- )

TION OF TEACHERS, AFL-CIO, j 35257

Defendant- )

Intervenor )

and . )

DENISE MAGDOWSKI, et al., )

)Defendants- )

Intervenor )

et al. !

r - v RjS.

FINDINGS OF FACT AND CONCLUSIONS OF LAW

IN SUPPORT OF RULING

ON DESEGREGATION AREA AND DEVELOPMENT OF PLANS

On the basis of the entire record in this action, including

particularly the evidence heard by the court from March 28

through April 14. 1972. the court now makes the following

Supplementary Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law. It

' should be noted that the court has taken no proofs with respect

to the establishment o f the boundaries o f the 86 public school

districts in the counties o f Wayne, Oakland and Macomb, nor

on the issue o f whether, with the exclusion o f the cHgr o f

Detroit school district, such school districts have commitci; acts

o f de jure segregation.

INTRODUCTION

1. On September 27, 1971, this court issued its Rulsugon

Issue of Segregation. On October 4, 1971, this court ismed

from the bench guidelines to bind the parties in the submission

of plans to remedy the constitutional violation found, ie .,

school segregation; and in particular this court noted that the

primary objective before us was to deveop and implement a

plan which attempts to “achieve the greatest possible degree of

actual desegregation, taking into account the practicalities of

the situation.” The same day this court reiterated these require

ments by orders “that the Detroit Board of Education submit a

plan for the desegregation of its schools within 60 days** and

“that the State defendants submit a metropolitan plan o f de

segregation within 120 days.” In response to these orders hear

ings were held, and thereafter rulings issued, on Detroit-only

plans (see Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law on Detroit-

Only Plans of Desegregation) and on the propriety of con

sidering remedies which extend beyond the corporate

geographic limits of the City of Detroit. (See Ruling on Pro

priety of Considering a Metropolitan Remedy to Accomplish

Desegregation of the Public Schools of the City of Detroit.)

Between March 28, 1972 and April 14, 1972, hearings were

held on metropolitan proposals for desegregation of the Detroit

public schools.

2. From the initial ruling on September 27, 1971, to this

day, the basis of the proceedings has been and remains the

violation: de jure school segregation. Since Brown v. Board of

Education the Supreme Court has consistently held that the

remedy for such illegal segregation is desegregation. The racial

history of this country is writ large by constitutional adjudica

tion from Bred Scott v. Sanford to Plessy v. Fergusmt to

1*498

I a 499

Brown. The message in Brown was simple: The Fourteenth

Amendment was to be applied full force in public schooling.

The Court held that “state-imposed” school segregation

immeasurably taints the education received by all children in

the public schools; perpetuates racial discrimination and a his

tory of public action attaching a badge of inferiority to the

black raoe in a public forum which importantly shapes the

minds and hearts of succeeding generations of our young

people; and amounts to an invidious racial classification. Since

Brown the Supreme Court has consistently, and with increasing

force, held that the remedy upon finding de jure segregation is

prompt and maximum actual desegregation of the public

schools by all reasonable, feasible, and practicable means avail

able. This court finds that there is nothing in the law, wisdom,

or facts, and the particular circumstances and arguments,

presented in this case which suggest anything except the affir

mance of these principles in both fact and law.

3. The task before this court, therefore, is now, and, since

September 27, 1971, has always been, how to desegregate the

Detroit public schools. The issue, despite efforts of the inter-

venors to suggest a new rationale for a return to the discredited

“separate but equal” policy, * is not whether to desegregate.

That question has been foreclosed by the prior and settled com

mands of the Supreme Court and the. Sixth Circuit. Our duty

now is to “grapple with the flinty, intractable realities” 2 Qf

implementing the constitutional commands.

4. In the most recent set of hearings, several issues were

addressed generally, including appropriate methods of pupils

reassignment to desegregate schools; quality and capacity of

school facilities; transportation needs incident to school de

segregation; the effects of new school construction, and

judicially established controls thereon, on any plan of de

segregation; the reassignment of faculty and restructuring of

facilities incident to pupil reassignment to accomplish school

desegregation: appropriate and necessary interim and final

administrative and financial arrangements; appropriate com

munity, parental, staff, and pupil involvement in the deseg

regation process; and attention to individual, cultural, and

l a 500

ethnic values, respect, dignity and identity. But the primary

question addressed by these hearings, in the absence of submis

sion of a complete desegregation plan by the state, remains the

determination of the area necessary and practicable effectively

to eliminate “ root and branch” the effects of state-imposed and

* supported segregation and to desegregate the Detroit public

schools.

SUPPLEMENTARY FINDINGS OF FACT

A. The Desegregation Area

5. The State Board of Education filed six (6) “plans”

without recommendation or preference; intervening defendants

Magdowski, et al., filed a proposal for metropolitan desegrega

tion which included most of the tri-county area; the defendant

Detroit Board of Education filed a proposal for metropolitan

desegregation which included the entire tri-county area. 3 At

the hearing plaintiffs presented a modification of the three pro

posals which actually described areas within which pupil deseg

regation was to be accomplished.

6. In the consideration of metropolitan plans of deseg

regation of the Detroit public schools, the State defendants

stand as the primary defendants. They bear the initial burden of

coming forward with a proposal that promises to work. In the

context of this case, they represent the “school authorities ” 4

to whom equity courts traditionally have shown deference in

these matters. ̂ Yet in its submission without recommendation

of six (6) “plans” the State Board of Education has failed to

meet, or even attempt to meet, that burden and none of the

other State defendants has filled the void.

7. The State Board refused to make any recommenda

tions to the court about the appropriate area for desegregation.

In State Defendant Porter’s words, the State Board “didn’t

make a decision, period.” Defendants Milliken and Kelley

merely filed objections to all six (6) plans.

8. Three of the State “plans” merely proposed concepts

alternative to maximum actual desegregation. The Racial

Proportion Plan described a statistical method of determining the

I a 501

number of transfers involved in achieving a particular racial

'ratio in each school once an area of desegregation had been

chosen. The Equal Educational Opportunity and Quality

Integration Plan was admitted to be a non-plan and described

criteria for education which, in whole or part, might, or might

not, be applicable to any school system.

9. Only one State “plan,” the Metropolitan District Re

organization Plan, attempted to describe an area within which

desegregation should occur, called the “initial operating zone”

(sometimes referred to hereafter as the “ State Proposal”). That

“plan,” however, was primarily concerned with discussing a new

governance structure for the desegregation area. Pupil reassign

ment was mentioned only in passing and no foundation was laid

by State defendants for the particular area of desegregation

described. Further, it suffered from the default of the State

defendants by their stubborn insistence that under their self-

serving, and therefore self-limiting, view of their powers they

were free to ignore the clear order of this court and abdicate

their responsibility vested in them by both the Michigan and

Federal Constitution for supervision of public education and

equal protection for all citizens.

10. From the very limited evidence in the record in sup

port of the area in that state proposal, the primary foundation

appears to be the particular racial ratio attained in that plan,

approximately 65% black, 35% white, with the provision that

the area could be expanded if “white flight” ensued. In the

absence of any other persuasive foundation, such area is not

based on any definable or legally sustainable criteria for either

inclusion or exclusion of particular areas; and the concept of an

“initial operating zone” raises serious practical questions, which

should be avoided if a more permanent solution is now possible.

In short, the area described by the “ initial operating zone” does

not appear to be based primarily on relevant factors, like elim

inating racially identifiable schools; accomplishing maximum

actual desegregation of the Detroit public schools; or avoiding,

where possible, maintaining a pattern of schools substantially

disproportionate to the relevant school community’s racial com

position by force of deliberate action by public authority. Nor.

I a 502

on the evidence in this record, is the “initial operating zone”

based on any practical limitation of reasonable times and dis

tances for transportation of pupils. These factors seem to have

played little part in the creation of the “ initial operating zone”

and are reflected less in its result.

11. At the hearings, moreover, the State defendants did

not purport to present evidence in support, or even in opposi

tion, to the State Proposal. The State, despite prodding by the

court, presented only one witness, who merely explained what

appeared on the face of the various State “Plans” submitted.

The State’s cross examination of witnesses was of no assistance

to the court in ascertaining any preference, legal or educational.

Put bluntly, State defendants in this hearing deliberately chose

not to assist the court in choosing an appropriate area for effec

tive desegregation of the Detroit public schools. Their resistance

and abdication of responsibility throughout has been consistent

with the other failures to meet their obligations noted in the

court’s earlier rulings. Indeed, some of the submissions spoke as

clearly in opposition to desegregation as did the legislature in

Sec. 12 of Act 48 ruled unconstitutional by the Sixth Circuit.

12. In such circumstances little weight or deference can be

given to the unsupported submission of the State Board of

Education. In light of the available alternatives and the facts

produced at the hearing bearing on the issue, the court finds

that State defendants offered no basis for ruling that the “initial

operating zone” is the appropriate area within which to effec

tively desegregate the Detroit public schools.

13. Similarly, the newly intervening, defendant school dis

tricts did not attempt at the hearing to assist the court in

determining which area was appropriate to accomplish effective

desegregation. They were given the opportunity, by express

written order and several admonitions during the course of the

hearings, to assist the court in the task at hand but chose in

their best judgment instead, in the main, to suggest their view

that separate schools were preferable. The failure of the group

of 40 districts to even comment that the court should exclude

certain districts under any number of available rationales may in

part be explained by the awkward position chosen by them and

their counsel of having single representation for districts on

different sides of the various suggested perimeters.

14. The plans of intervening defendants Magdowski, et al.,

and the defendant Detroit Board of Education are similar. With

slight variations they include the entire tri-county, metropolitan

Detroit area, with that area divided into several regions or

clusters to make the planning for accomplishing desegregation

more manageable. Although both have as their main objective

desegregation, their larger area arises primarily from a heavy

emphasis on such factors as white flight and an appropriate

socio-economic balance in each cluster and school. 6

15. The authors of the Detroit Board and Magdowski

plans readily admit that the regions or clusters for pupil reas

signment which involve Mt. Clemens and Pontiac are not direct

ly related to desegregation of the Detroit public schools and

may be disregarded without any substantial adverse effect on

accomplishing our objective. No other party has expressed any

disagreement with that view. And the court finds that these two

regions or clusters, for purposes of pupil reassignment, need not

be included at this time in the desegregation area.

16. With the elimination of these two clusters there are,

then, three basic proposals to be considered for the desegrega

tion area: the State Proposal; the Detroit Board Proposal, and

the proposal of defendant-intervenors Magdowski, et al. In

addition, as noted, plaintiffs filed a modification of these three

proposals.

17. Each of these proposals starts from the same two

premises: (1) the tri-county area 7 constitutes the relevant

school community which can serve as an initial benchmark in

beginning the evaluation of how to effectively eliminate the

racial segregation of Detroit schools; (2) but in some instances

reasonable time and distance limitations for pupil transporta

tion, and in other instances the actual area required to eliminate

the pattern of racially identifable schools, limit the area within

which pupil reassignment should occur. In terms of proof, put

ting aside arguments of impotence by the State defendants,

I a 503

I a 504

there was absolutely no contradictory evidence on these two

criteria. The entire tri-county area includes areas, pupils, and

schools in 86 school districts; it includes approximately one

million students, of whom approximately 20% are black. Based

on the evidence concerning school and non-school factors, 8

and reasonable time and distance limitations for pupil transpor

tation, the court finds that both premises are accurate.9

18. The State Proposal includes the areas, pupils and

school in 36 school districts, approximately 550,000 students

are included of whom 36% are black. The Detroit Board Pro

posal (excluding clusters 8 and 12) includes the areas, pupils,

and schools in 69 school districts; approximately 850,000 stu

dents are included, of whom 25% are minority. ^ The CCBE

Proposal includes the areas, pupils, and schools in some 62

school districts; approximately 777,000 students are included

of whom 197,000 (25.4%) are black. Plaintiffs’ Proposal

includes the areas, pupils, and schools in 54 school districts;

approxim ately 780,000 students are included, of whom

197,000(25.3%) are black.

19. The State Proposal approaches what may be con

sidered a substantial disproportion in the context of this case. It

is to be remembered that within any desegregation area, the

racial composition of desegregated schools will vary from the

area’s racial mix. Given the variations in school plant, demo

graphic and geographic factors, limiting the desegregation area

to the State Proposal would result in some schools being sub

stantially disproportionate in their racial composition to the

tri-county area, and other schools racially identifable, all with

out any justification in law or fact. This finding is supported by

the lack of any apparent justification for the desegregation area

described by the State Proposal except a desire to achieve an

arbitrary racial ratio.

20. Transportation of children by school bus is a common

practice throughout the nation, in the state of Michigan, and in

the tri-county area. Within appropriate time limits it is a con

siderably safer, more reliable, healthful and efficient means of

getting children to school than either car pools or walking, and

this is especially true for younger children.

I a 505

21. In Michigan and the tri-county area, pupils often

spend upwards of one hour, and up to one and one half hours,

one-way on the bus ride to school each day. Consistent with its

interest in the health, welfare and safety of children and in

avoiding impingement on the educational process, state educa

tional authorities routinely fund such transportation for school

children. Such transportation of school children is a long

standing, sound practice in elementary and secondary education

in this state and throughout the country. And the court finds

such transportation times, used by the state and recommended

here, are reasonable in the circumstances here presented and

will not endanger the health or safety of the child nor impinge

on the educational process. For school authorities or private

citizens to now object to such transportation practices raises the

inference not of hostility to pupil transportation but rather

racially motivated hostility to the desegregated school at the

end of the ride.

22. The Plaintiffs’ Proposal made reference to P.M.8,

based on the TALUS regional transportation and travel times

study. Although there was dispute over the meaning of the

study, such studies are deemed sufficiently reliable that major

governmental agencies customarily rely on their projection for a

variety of planning functions. When used by the plaintiffs, P.M.

8, in conjunction with the Detroit Board’s survey of maximum

school to school travel times, served as a rough guideline within

which the plaintiffs’ modification of other proposals attempted

to stay in an effort to provide maximum desegregation without

any more transportation time than is required to desegregate.

This court finds that the utilization of these two factors, and

the lower travel time estimates which should result, is a reason

able basis for the modification in the circumstances of this case.

The court’s duty and objective is not to maximize transporta

tion but to maximize desegregation and within that standard it

will always be reasonable to minimize transportation. To that

end the court has accepted the more conservative perimeter for

the desegregation area suggested as a modification by plaintiffs

because it provides no less effective desegregation.

23. Based on these criteria, the State Proposal is too nar

rowly drawn.

I a 506

24. Based on these criteria, parts of the Detroit Board

Proposal are too sweeping.

25. Based on these criteria, the CCBE Proposal and the

Plaintiffs’ Proposal, roughly approximate the area so de-

* scribed * *.

26. There is general agreement among the parties, and the

court so finds, that on the west the areas, schools, and pupils in

the Huron, Van Buren, Northville, Plymouth and Novi districts

12 (1) are beyond the rough 40-minute travel time line; (2) are

not necessary to effectively desegregate schools involved in the

regions and clusters abutting those schools; and, (3) at this

writing, are not otherwise necessary, insofar as pupil assignment

is concerned, to provide an effective remedy now and hereafter.

(See Findings 63-69 below.)

27. In the southwest the school districts of Woodhaven,

Gibralter, Flat Rock, Grosse lie and Trenton are within reason

able time and distance criteria set forth above. These virtually

all-white districts are included in the Detroit Board Proposal but

excluded from the plaintiffs’ modification. The areas, schools

and pupils in such school districts are similarly not necessary to

effectively desegregate. (Clusters 13, 14, and 15 in Plaintiffs’

Proposal are 20.5%, 24.4% and 22.7% black respectively.) There

is nothing in the record which suggests that these districts need

be included in the desegregation area in order to disestablish the

racial identifiability of the Detroit public schools. From the

evidence, the primary reason for the Detroit School Board’s

interest in the inclusion of these school districts is not racial

desegregation but to increase the average socio-economic

balance of all the schools in the abutting regions and clusters. In

terms of what this court views as the primary obligation estab

lished by the Constitution — racial desegregation — the court

deems the proper approach is to be more conservative: the

court finds it appropriate to confine the desegregation area to

its smallest effective limits. This court weighs more heavily the

judicially recognized concern for limiting the time and distance

of pupil transportation as much as possible, consistent with the

constitutional requirement to eliminate racially identifiable

schools, than a concern for expanding the desegregation area to

I a 507

raise somewhat the average socio-economic balance of a rela

tively few clusters of schools. * 3

28. To the north and northeast, the only major disagree

ment among the Detroit Board Proposal and plaintiffs’

modification relates to the areas, schools, and pupils in the

Utica School District. This district is a virtually all-white, long,

relatively narrow area extending several miles in a north-south .

direction away from the city of Detroit. Only the southern part

of the district is within the rough, TALUS 40-minute travel

time line.

29. The Detroit Board argues that Utica should be includ

ed in order to raise the average socio-economic balance of the

abutting clusters and schools. In this instance, however, the

overall racial composition of the cluster, 27.0% black, may tend

toward disproportionate black relative to the tri-county starting

point.

30. Mr. Henrickson, the planner for the Board, also sug

gested that Cluster 3 of Plaintiffs’ Proposal, because of its

omission of Utica, might present some problems, which he

admitted could be solved, in designing a plan of pupil reassign

ment for the desegregation of schools. (See Findings 34-39

below.)

31. In light of these relevant, and competing, considera

tions the question presented by the Utica situation is close;

however, at this writing, the court determines that the areas,

schools, and pupils in the Utica School District need not be

included, and therefore, should not be included in the deseg

regation area. ̂4

32. The court Finds that the appropriate desegregation

area is described by plaintiffs’ modification of the three primary

proposals. Within that area the racial identifiability of schools

may be disestablished by implementation of an appropriate

pupil desegregation plan. The area as a whole is substantially

proportionate to the tri-county starting point. Within the area it

is practicable, feasible, and sound to effectively desegregate all

schools without imposing any undue transportation burden on

the children or on the state’s system of public schooling. The

I a 508

time or distance children need be transported to desegregate

schools in the area will impose no risk to the children’s health

and will not significantly impinge on the educational process.

B. Ousters

33. The Detroit Board Proposal makes use of 16 regions

or clusters. These clusters range from 36,000 to 105,000 pupils

and from 17.5% to 29.7% “minority.” The clusters are arranged

along major surface arteries and utilize the “skip,” or non

contiguous zoning, technique to minimize the time and distance

any child need spend in transit. The use of these clusters basical

ly subdivides the planning for pupil reassignment within the

desegregation area into a series of smaller, manageable and

basically independent plans. Thus, although as the new inter-

venors suggest devising a desegregation plan for a system with

some 800,000 pupils has never been attempted, the practical

'and manageable reality is that desegregation plans for systems

with from 36,000 to 100,000 pupils has been done and such

plans have been implemented.

34. Plaintiffs’ Proposal uses the same cluster technique

and the same clusters, modified to fit the desegregation area.

The 15 clusters range from 27,000 to 93,000 pupils and from

20.5% to 30.8% black. Only three relevant objections were

raised by Mr. Henrickson, to the clusters as modified.

35. First, Cluster 4 was challenged as “concealing” a

“problem,” namely effective desegregation of other schools

resulting from the omission of Utica from plaintiffs’ modifica

tion. On cross-examination Mr. Henrickson admitted that the

“problem” of actual pupil desegregation for these other schools

could be “solved,” that all schools within Cluster 4 could be

affectively desegregated, and that Cluster 4 was smaller than the

Detroit Board Cluster 6. The objection was thus narrowed to

the possibility that a suburban high school constellation feeder

pattern might have to be split between two Detroit high school

constellation feeder patterns in order to desergregate. Several of

the Detroit Board’s clusters, however, also contain two Detroit

high school feeder patterns.

I a 509

36. This objection, splitting an existing feeder pattern,

was raised directly in reference to Cluster 12. In neither

instance, however, did Mr. Henrickson suggest that the time or

distance of transportation involved was too long or that it would

present administrative difficulty in devising a pupil assignment

plan for either cluster. The objection relates solely to a matter

of administrative convenience, namely the use of existing feeder

patterns in preparing pupil assignments. For example, Mr.

Henrickson previously admitted that in drawing a pupil assign

ment plan, an alternative to use of existing feeder patterns

would be to “wipe the slate clean,” and disregard existing

feeder patterns. In fact one of the State plans suggested use of

census tracts as an alternative. 1 ̂On numerous occasions in the

past Mr. Henrickson himself has reassigned parts of one feeder

pattern to another school in order to relieve overcrowding

and/or accomplish desegregation. The objection to such

practice, therefore, is admittedly insubstantial.

37. The third objection relates to the exchange of Detroit

Northern for Detroit Murray in Clusters 6 and 15 requiring that

the students transported, if they proceed on their entire journey

by way of the expressway, encounter an interchange which

tends to be rather slow-moving. Such transportation time and

distance, however, is well within the rough criteria for reason

ableness and is shorter than or comparable to the maximum

trips required in the Detroit Board’s clusters. In other instances,

Mr. Henrickson admitted that pupils in the Detroit proposal

might also have to travel through similar interchanges. More

over, the objection to this particular increase in travel time must

be weighed against the apparent general decrease in time which

would be required in plaintiffs’ modified clusters as compared

with the Detroit Board’s clusters. In any event the desegregation

panel, based on its investigation of all aspects of pupil assign

ment, remains free to suggest a modification of these clusters in

order to reduce the time and number of children requiring

transportation.

38. With that caveat, the court finds that plaintiffs’

modification of the Detroit Board’s clusters provides a

workable, practicable, and sound framework for the design of a

plan to desegregate the Detroit public schools.

C. PupH Assignment and Transportation.

39. Example o f various methods of pupil assignment to

accomplish desegregation have been brought to the attention of

the court by the parties: pairing, grouping, and clustering of

schools; various strip, skip, island, and non-contiguous zoning;

various lotteries based on combinations of present school assign

ment, geographic location, name, or birthday. Judicious use of

these techniques — coupled with reasonable staggering of school

hours and maximizing use of existing transportation facilities —

can lead to maximum actual desegregation with a minimum of

additional transportation.

40. Quite apart from desegregation, under any circum

stances, transportation for secondary pupils living more than \Vz

miles, and elementary pupils, living more than 1 mile from

school, is often demanded by parents and should be provided.

Moreoever, it is essential to the effectiveness of any desegrega

tion plan that transportation be provided free to all students

requiring it under that criteria. (Brewer v. Norfolk Board of

Education,____F. 2d_____ (April 1972) (4th Cir.)

41. In the recent past more than 300,000 pupils in the

tri-county area regularly rode to school on some type of bus;,

this figure excludes the countless children who arrive at school

in car pools, which are many, many times more dangerous than

riding on the school bus.

42. Throughout the state approximately 35-40% of all stu

dents arrive at school on a bus. In school districts eligible for

state reimbursement of transportation costs in the three

affected counties, the percent of pupils transported in 1969-70

ranged from 42 to 52%.

43. In comparison approximately 40%, or 310,000, of the

780,000 children within the desegregation area will require

transportation iii order to accomplish maximum actual deseg

regation.

44. Hence, any increase in the numbers of pupils to be

transported upon implementation of a complete desegregation

plan over the number presently transported, relative to the state

I a 510

I a 511

and the tri-county area, should be minimal. Indeed, any increase

may only reflect the greater numbers of pupils who would be

transported in any event but for the state practice, which af

fected the segregation found in this case, and which denies state

Reimbursement to students and districts wholly within city

limits regardless of the distance of the child from the school to

which assigned. ^ (R u lin g on Issue of Segregation at 14.) The

greatest change is the direction of the buses.

45. There is uncontradicted evidence that the actual

cost of transportation for a two-way plan of desegregation

should be no greater than 50 to 60 dollars per pupil trans

ported, comparable to the present costs per pupil through

the state. Increases in the total costs of pupil transportation in

the desegregation area, therefore, will result primarily from pro

viding all children requiring transportation a free ride instead of

imposing the costs of transportation for many on the families in

districts which are ineligible for state reimbursement and which

fail to provide transportation.

46. By multiple use of buses, careful routing, and econo

mies of scale resulting from a comprehensive system of pupil

transportation, it may be possible to achieve savings in per pupil

costs. For example in 1969-1970 many school districts in the

tri-county area which used the same bus for even two loads per

day lowered their per pupil costs to $40 or less. In a co

ordinated, urban pupil transportation system it may be possible

to raise the bus use factor to three of more. (See “First Report”

State Survey and Evaluation.)

47. In the tri-county area in the recent past there were

approximely 1,800 buses (and another 100 smaller vans) used

for the transportation of pupils. Assuming a rough average of 50

pupils per bus carrying three loads of students per day, this

transportation fleet may prove sufficient to carry some 270,000

pupils.

48. Various public transit authorities now transport an

additional 60,000 pupils on their regular public runs.

49. The degree to which these plausible bus-use factors

I a S12

can be realized to their maximum, and whether these public

transit facilities may be fully utilized in a plan o f desegregation,

must be answered upon careful investigation by a panel o f ex

perts.

50. There is no disagreement among the parties, and the

court so finds, that additional transportation facilities, at least

to the number o f 3 SO buses, will have to be purchased to meet

the increase in the number o f students who should be provided

transportation for either an interim or final plan o f desegrega

tion.

51. For all the reasons stated heretofore — including time,

distance, and transportation factors — desegregation within the

area described in physically easier and more practicable and

feasible, than desegregation efforts limited to the corporate

geographic limits of the city of Detroit.

52. The issue of transportation of kindergarten children,

and their inclusion in part or in full in the desegregation plan,

may require further study. There was general agreement among

the experts who testified that kindergarten, but for “political”

considerations, should be included, if practicable, in the deseg

regation plan. Kindergarten, however, is generally a half-day

program. Transportation of kindergarten children for upwards

of 45 minutes, one-way, does not appear unreasonable, harmful,

or unsafe in any way. In the absence of some compelling justifi

cation, which does not yet appear, kindergarten children should

be included in the final plan of desegregation.

53. Every effort should be made to insure that transporta

tion and reassignment of students to accomplish desegregation

is “two-way” and falls as fairly as possible on both races.

Although the number of black and white children transported

and reassigned at the outset will be roughly equal, it is

inevitable that a larger proportion of black children will be

transported for a greater proportion of their school years than

white children, if transportation overall is to be minimized. To

mitigate this disproportion, every effort should be made at the

outset to randomize the location of particular grade centers. In

the short term, full utilization of vastly under-capacity inner-

I a 513

city schools may also help to mitigate the disproportion for

some black children; and in the long term, new school capacity,

consistent with other constitutional commands and the overall

needs of the desegregation area and the surrounding area, should

be added in Detroit, in relative proximity to concentrations of

black student residence.

D. Restructuring of Facilities and

Reassignment of Teachers

54. In the reassignment of pupils to accomplish deseg

regation the court finds that facilities must be substantially

reallocated and faculty substantially reassigned by reason of the

clustering, pairing and grouping of schools.

55. In order to make the pupil desegregation process fully

effective the court finds that it is essential to integrate faculty

and staff and to insure that black faculty and staff representa

tion at every school is more than token. The court has pre

viously found and reaffirms that “a quota or racial balance in

each school which is equivalent to the system-wide ratio and

without more” is educationally unsound, and that the desid

eratum is the balance of staff by qualifications for subject and

grade level, and then by race, experience and sex. It is obvious,

given the racial composition of the faculty and staff in the

schools in the metropolitan plan area, and the adjusted racial

composition of the students, that vacancies and increases and

reductions in faculty and staff cannot effectively achieve the

needed racial balance in this area of the school operation.

Active steps must be taken to even out the distribution of black

teachers and staff throughout the system.

56. In the desegration area approximately 16% of the

faculty and 12% of the principals and assistant principals are

black. In this context “token” means roughly less than 10%

black. Moreover, where there is more than one building adminis

trator in any school, a bi-racial administrative team is required

wherever possible.

57. Every effort should be made to hire and promote, and

to increase such on-going efforts as there may be to hire and

I a 514

promote, additional black faculty and staff. Because of the

system atic and substantial under-employment of black

administrators and teachers in the tri-county area, an affirma

tive program for black employment should be developed and

implemented.

58. The rated capacity of classrooms in the Detroit public

schools is 32; in some of the suburban districts the average rated

capacity is as low as 24 or 25. Utilization should be redeter

mined on a uniform basis.

59. In respect to faculty and staff, school facilities, and

the utilization of existing school capacity, normal administra

tive practice in handling the substantial reallocation and reas

signment incident to pupil desegregation should produce

schools substantially alike.

60. In the circumstances of this case, the pairing, grouping

and clustering of schools to accomplish desegregation with

minimum transportation often requires use of grade arrange

ments such as K-4, K-5, or even K-6. In so planning pupil reas

signments, it is sometimes necessary, and often administratively

practicable, to include grades K-8 or even K-9 to achieve the

maximum actual desegregation with the minimum trans

portation. Grade structures in most elementary schools in the

desegregation area is a basic K-6; however, almost all other

combinations are found. They differ within and among various

districts.

61. In the reassignments of pupils and teachers and the

reallocation of equipment and facilities required to accomplish

desegregation, the elementary grades and schools present rela

tively few administrative difficulties, while the high school

grades and facilities present the greater difficulties, particularly

with respect to scheduling and curriculum.

62. For these reasons, if it develops that interim choices

must be made because of the impossibility of immediate deseg

regation of all grades, schools, and clusters in the desegregation

area, the weight of the evidence is, and the court so finds, that

desegregation should begin first at the earliest grades for entire

I a 515

elementary school groupings throughout as many clusters as

, possible.

E. School Construction

63. Relative to suburban districts the Detroit public

schools, as a whole, are considerably over-capacity. (See also

Finding 58, supra.) To alleviate this overcrowding equalize rated

capacity and minimize and equalize transportation burdens

borne by black pupils in the city, needed new school capacity,

consistent with other requirements of a desegregation plan,

should be added on a priority basis in the city of Detroit.

64. Relevant to the court’s choice of a desegregation area

more limited than the Detroit Board Proposal is the testimony,

elecited on cross-examination from two of the primary authors

of that proposal, related to the effects of controlling new school

construction. The broader area in the Detroit proposal was

chosen without any real consideration of the impact of control

ling school construction in an area larger than the desegregation

area. Upon reflection, both Dr. Flynn and Mr. Henrickson

admitted that closely scrutinizing and limiting the addition of

capacity to areas outside the desegregation area might lead them

to re-evaluate the need, in the context of maintaining now and

hereafter a unitary system, to include an area as sweeping as

recommended by the Detroit Board Proposal.

65. In our Ruling on Issue of Segregation, pp. 8-10, this

court found that the “residential segregation throughout the

larger metropolitan area is substantial, pervasive and of long

standing” and that “governmental actions and inaction at all

levels, Federal, State and local, have combined with those of

private organizations, such as loaning institutions and real estate

associations and brokerage Firms, to establish and to maintain

the pattern of associations and brokerage firms, to establish and

to maintain the pattern of residential segregation through the

Detroit metropolitan area.” We also noted that this deliberate

setting of residential patterns had an important effect not only

on the racial composition of inner-city schools but the entire

School District of the City of Detroit. (Ruling on Issue of Seg

regation at 3-10.) Just as evident is the fact that suburban

I a 516

school districts in the main contain virtually all-white schools.

The white population of the city declined and in the suburbs

grew; the black population in the city grew, and largely was

’contained therein by force of public and private racial discrim

ination at all levels.

66. We also noted the important interaction of school and

residential segregation: “Just as there is an interaction between

residential patterns and the racial composition of the schools, so

there is a corresponding effect on the residential pattern by the

racial composition of schools.” Ruling on Issue of Segregation

at 10. Cf. Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenberg, 402 U.S. 1, 20-21

(1971); “People gravitate toward school facilities, just as

schools as located in response to the needs of people. The loca

tion of schools may thus influence the patterns of residential

development of a metropolitan area and have important impact

on composition of inner city neighborhoods.”

67. Within the context of the segregatory housing market,

it is obvious that the white families who left the city schools

would not be as likely to leave in the absence of schools, not to

mention white schools, to attract, or at least serve, their chil

dren. 18 Immigrating families were affected in their school and

housing choices in a similar manner. Between 1950 and 1969 in

the tri-county area, approximately 13,900 “regular classrooms,”

capable of serving and attracting over 400,000 pupils, ^ were

added in school districts which were less than 2% black in their

pupil racial composition in the 1970-71 school year. (P.M. 14;

P.M. 15).

68. The precise effect of this massive school construction

on the racial composition of Detroit area public schools cannot

be measured. It is clear, however, that the effect has been sub

stantial. 20 Unfortunately, the State, despite its awareness of

the important impact of school construction and announced

policy to control it, acted “in keeping generally, with the

discriminatory practices which advanced or perpetuated racial

segregation in these schools.” Ruling on Issue of Segregation at

15; see also id., at 13.

69. In addition to the interim re-evaluation of new school

I a 517

construction required in the order, pursuant to the State

Board’s own requirements, the final plan will consider other

•appropriate provisions for future construction throughout the

metropolitan area.

» F. Governance, Finance and Administrative Arrangements

70. The plans submitted by the State Board, the Detroit

Board, and the intervening defendants Magdowski, et al., discuss

generally possible governance, finance and administrative ar