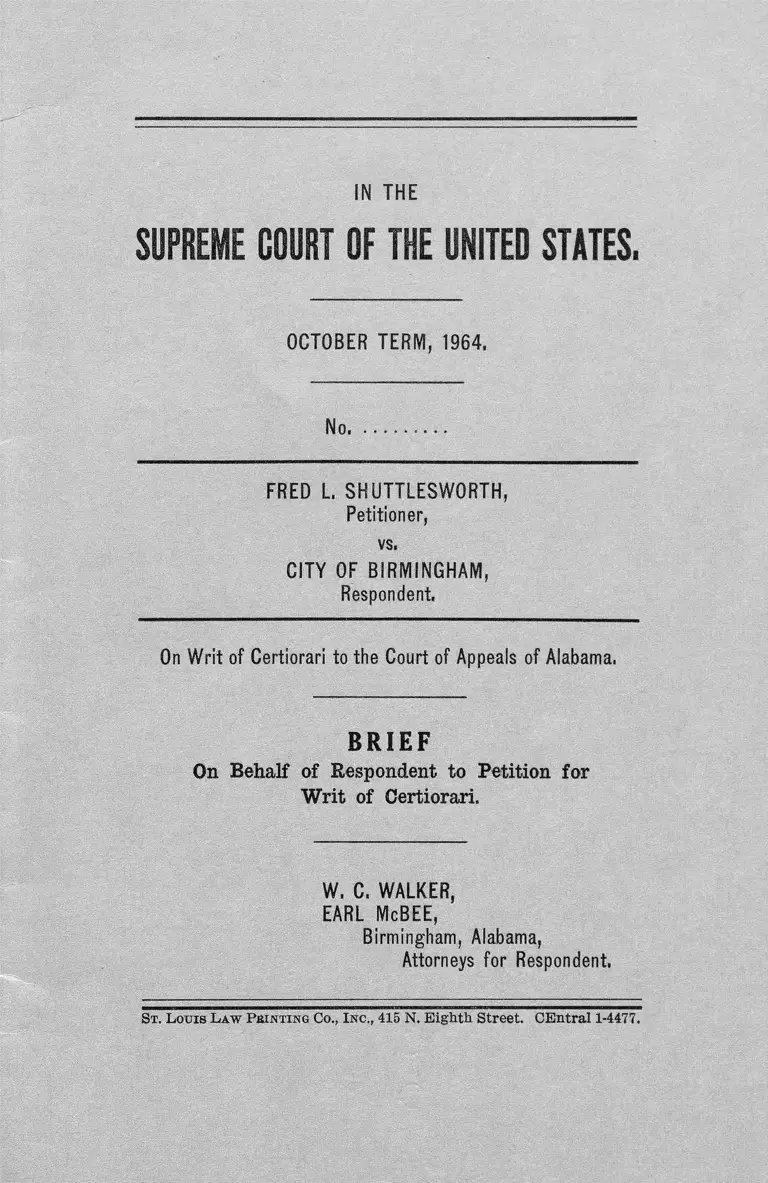

Shuttlesworth v Birmingham AL Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1964

21 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Shuttlesworth v Birmingham AL Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1964. 05bb8654-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1a66fe89-da97-4abf-bdf0-fd9735987fda/shuttlesworth-v-birmingham-al-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 05, 2026.

Copied!

IN TH E

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES,

OCTOBER TERM, 1964,

No,

FRED L. SH U TTLE S W O R TH ,

Petitioner,

vs,

C ITY OF BIRMINGHAM,

Respondent.

On W rit of Certiorari to the Court of Appeals of Alabama,

BRIEF

On Behalf of Respondent to Petition for

Writ of Certiorari.

W, C. WALKER,

EARL McBEE,

Birmingham, Alabama,

Attorneys for Respondent.

St. Louis La w F e in tin g Co., Inc., 415 N. Eighth Street. CEntral 1-4477.

INDEX.

Page

Citation to opinion below ........................................ 1

Statement in opposition to jurisdiction of the Court . . 1

Statement ..................... -

Statement in opposition to questions presented . . . . 4

Constitutional and statutory provisions involved . . . . 4

Argument ............................................................................ 5

Oases Cited.

Bouie v. Columbia, . . . U. S. . . . , 12 L. Ed. 894

(1964) .............................................................................15,16

Drummond v. State, 37 Ala. App. 308, 67 So. 2nd

280 ................................................................................... 6

Garner v. State of Louisiana, 82 Sup. Ct. 248, 368

IT. S. 157 .......................................................................... 14

Inland Power and Light Company v. Grieger, 91 F. 2d

811 ................................................................................... 6

Phifer v. City of Birmingham, . . . Alabama App. .. .,

160 So. 2d 898 .................................................12,14,15,16

Philyaw v. City of Birmingham, 36 Ala. App. 112, 54

So. 2d 6 1 9 ................................................................ 15

State v. Lucas, Miss., 221 Miss. 538, 73 So. 2d 158 . . . . 8

State v. Taylor, 119 A. 2d 36, 38 N. J. Super. 6 .......... 11

Statutes Cited.

Constitution of the United States, Fourteenth Amend

ment ............................................................................... 4. 6

11

General City Code of Birmingham:

Section 1142 ....................... .......................... 2. 4, 5, 8,13

Section 1230 ................................. .............. ..4,16

Section 1231 .................... ...2, 4, 5, 8,12,13,14,15,16

Textbooks Cited.

27 A. dur. Section 57, p. 623 ........................... 13

22 Corpus Juris Secundum, Section 24 (2), p. 67 . . . . 14

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES.

OCTOBER TERM, 1964,

No.

FRED L. S H U TTLE SW O R TH ,

Petitioner,

vs.

C ITY OF BIRMINGHAM,

Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the Court of Appeals of Alabama,

BRIEF

On Behalf of Respondent to Petition for

Writ of Certiorari.

CITATION TO OPINION BELOW.

The opinion of the Alabama Court of Appeals is reported

at . . . Ala. App. . . . , 161 So. 2d 796, and is set forth

in the appendix to petitioner’s brief and application for

writ of certiorari at appendix page la.

STATEMENT IN OPPOSITION TO JURISDICTION

OF THE COURT.

Petitioner has not been deprived of rights, privileges,

and immunities secured by the Constitution of the United

States.

STATEMENT.

As set forth in petitioner’s statement (p. 4), the pe

titioner was charged and convicted below for violation

of Sections 1142 (as amended by Ordinance No. 1436-F)

and 1231 of the General City Code of Birmingham.

The complaint charging petitioner was framed in two

counts as set out in petitioner’s statement (p. 4). Count-

one complained that the petitioner, as part- of a group,

blocked the free passage over a sidewalk in the City of

Birmingham. Count Two complained that the petitioner

failed to obey a lawful order, signal or direction of a

police officer.

The following facts were established by the evidence

introduced in the trial court. On April 4, 1962, at about

10:30 A. M., Officer B-obert E. Byars, Jr., observed the

petitioner,, along with James Phifer and three or four

other people walking South on 19th Street toward 2nd

Avenue, North, Birmingham, Alabama (R. 17, 20). Officer

Byars then entered Newberry’s- Department Store at its

alley entrance and walked to the front of the store at

19th Street and 2nd Avenue (R. 17, 18). When he got

to the front entrance he saw the petitioner standing in

a group of ten or twelve people (R. 18, 28, 40). They were

on the Northwest corner of 2nd Avenue and 19th Street

(R. 18, 28, 40). The group was standing, listening and

talking (R. 18). The traffic light changed a number of

times while they stood there at the intersection (R. 38).

The group blocked pedestrian traffic to such an extent that

some people walking east on the north side of 2nd Avenue

had to walk into the street to get around the group (R.

18, 21, 29). Petitioner was a member of the group (R. 18,

28, 35, 42, 51, 61, 62, 76). Officer Byars watched the

group for a minute to a minute and a half (R. 19, 28, 29).

Officer Byars then walked up to the group and informed

them they would have to move on and clear the sidewalk

— 3

so as to allow free passage and not obstruct pedestrian

traffic (R, 19, 28, 29). A small number in the group

moved but that was all. Petitioner did not move (R. 19,

42, 51, 62, 76). After a short while, the officer informed

the group a second time they would have to move and

not obstruct the sidewalk in order to permit pedestrian

traffic to move unhampered (R. 19). Petitioner and some

others in the group did not move and petitioner stated:

“ You mean to say we can’t stand here on the sidewalk?”

(R. 19, 30). Officer Byars did not do or say anything for

a short period and then he told the group that he was

telling them the third and last time to move or they

would be arrested for obstructing the sidewalk (R. 19, 30,

62). Petitioner was still in the group (R. 19, 30, 35, 42,

51, 61, 62, 76). There was still some eight to twelve

people in the group when told to move the third time (R.

19, 30, 35, 42, 51, 61, 62, 76). Petitioner did not move

but made the statement: “ You mean to tell me we can’t

stand here in front of this store?” (R. 19). Officer Byars

then informed petitioner that he was under arrest, after

which time petitioner moved away saying: “ Well, I will

go into the store” (R. 19, 21, 43, 54). At this time the

rest of the group began moving away (R. 54). Officer

Byars followed petitioner into Newberry’s Store and took

him into custody (R. 19, 20). Petitioner asserts in his

statement that James Phifer was arrested simultaneously

with Shuttlesworth, but this is not so. The circumstances

of James Phifer’s arrest are as follows: After taking

Shuttlesworth into custody, Officer Byars took him to the

west curb to await transportation to city jail (R. 20, 34).

While awaiting the transportation James Phifer walked

up and began talking to the petitioner (R. 20, 34). He

was told that petitioner was under arrest and that he

could not talk to him. He was instructed three times

to move away from petitioner before he was arrested (R.

20, 34), Obviously the Alabama Court of Appeals found

from the evidence that James Phifer was not arrested for

— 4 —

obstructing the sidewalk, but for talking to petitioner,

and failing to leave when so instructed. Under the cir

cumstances, it is clear that no traffic situation existed at

that time and therefore no violation was established under

either Section 1142 as amended or Section 1231.

STATEMENT IN OPPOSITION TO QUESTIONS

PRESENTED.

1. Petitioner was convicted on a record containing ample

evidence of his guilt and therefore was not denied due

process of law contrary to the Fourteenth Amendment

to the Constitution of the United States.

2. Petitioner was convicted under ordinances which as

applied to his conduct were not unconstitutionally vague

under the Fourteenth Amendment.

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY PROVISIONS

INVOLVED.

In addition to the ordinances set out in Petitioner’s

application this case also involves Section 1230 of the

General City Code of Birmingham:

Police to direct traffic; directing in event of fire or

emergency.—It shall be the duty of the police department

to enforce the provisions of this chapter. Officers of the

Police Department are hereby authorized to direct all

traffic either in person or by means of visible or audible

signal or sign in conformance with the provisions of this

chapter; provided, that in the event of a fire or other

emergency or to expedite traffic or safeguard pedestrians,

officers of the police or fire department may direct traffic,

as conditions may require, notwithstanding the provisions

of this chapter.

Section 1230 is involved in this case because when it is

construed in pari materia with Section 1231, it limits or

restricts the scope of Section 1231 to traffic situations.

0 —

ARGUMENT.

Petitioner, Fred L. Shuttlesworth was convicted of

violating Sections 1142 and 1231 of the General City Code

of Birmingham, Alabama.

Section 1142 of the General City Code of Birmingham,

Streets and Sidewalks to be kept open for free passage

reads:

“ Any person who shall obstruct any street or side

walk or part thereof in any manner not permitted by

this code or other ordinance of the City with any

animal or vehicle, or with boxes or barrels, glass,

1 trash, rubbish or display of wares, merchandise or

sidewalk signs, or other like things, so as to obstruct

the free passage of persons on such street or side

walks or any part thereof, or who shall assemble a

crowd or hold a public meeting in any street without

a permit, shall, on conviction, be punished as pro

vided in Section 4.

“It shall be unlawful for any person or any number

i of persons to so stand, loiter, or walk upon any street

or sidewalk in the City as to obstruct free passage

over, on or along said street or sidewalk. It shall also

be unlawful for any person to stand or loiter upon

any street or sidewalk of the City after having been

requested by any police officer to move on.”

Section 1231 of the General City Code of Birmingham,

Obedience to Police, reads as follows:

“It shall be unlawful for any person to refuse or

fail to comply with any lawful order, signal or direc

tion of a police officer.”

There are only two questions which petitioner contends

are presented to this Court for review. Petitioner’s ques

tions are stated as follows:

“ 1. Whether petitioner was denied due process of

law contrary to the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States by his conviction

on a record containing no evidence of his guilt.

' “ 2. Whether petitioner was also denied due process

of law by his conviction under ordinances which as

applied to his conduct are unconstitutionally vague,

under the Fourteenth Amendment.”

First Question,

Let us now determine whether or not there was sufficient

evidence to justify petitioner’s conviction and afford him

his full rights under the “ due process” clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment.

It may well be that a defendant is protected by the

Constitution from conviction on a record without any evi

dence of guilt. This is not the ease here. The evidence

in this case is overwhelmingly in support of the trial

court verdict. Appellant raised this question in the Cir

cuit Court by a motion to exclude the evidence. He as

signed its overruling as error. Naturally, a motion to

exclude the evidence will not lie if there is sufficient evi

dence to support conviction. The rule in this regard in

Alabama is that no error results from the overruling of a

motion to exclude where the evidence presents a question

for the jury and is sufficient to sustain conviction. Drum

mond v. State, 37 Ala. App. 308, 67 So. 2nd 280. A sim

ilar rule is expressed in Inland Power and Light Company

y, Grieger, 91 F. 2d 811, where we find:

“ In considering the evidence, we must consider

only that which is most favorable to Appellees, with

every inference of fact that might be drawn from it.

Maryland Casualty Co. v. Jones, 279 U. S. 792, 49 S.

Ct. 484, 73 L. Ed. 960.”

It is clear that both the Alabama rule in regard to

“ motions to exclude the evidence” and the Federal rule

— 6 —

in regard to the consideration of the evidence and the in

ferences to be drawn therefrom, are simply giving recog

nition to the fact that the trial judge is in a much better

position to weigh and evaluate contradictory testimony.

The Appellate Courts are simply not in a position to

fairly make such a determination; and consequently, the

foregoing rules were formulated to place this burden

where it logically belongs.

Seldom is a record presented to this honorable court or

any other Appellate Court that does not contain contra

dictory evidence as to distances, number of persons in

volved or other matters not mentally noted when ob

served. In this case the evidence, although possibly

disputed, shows the petitioner was standing in a group of

ten or twelve people (R. 18, 28, 40), that they stood on

the corner of 2nd Avenue and 19th Street (R. 18, 28, 40)

through several changes in the traffic light (R. 38), and

that the group, including petitioner, blocked the sidewalk

to such an extent that other pedestrians using the side

walk had to walk out into the street in order to get

around the group (R. 18, 21, 29). Officer Byars watched

the group for a minute to a minute and one-half (R. 19,

28, 29) and then walked up to the group and informed

them they were blocking the sidewalk and to move (R.

19, 28, 29). After a short while Officer Byars told the

group a second time they would have to move (R. 19).

Petitioner and others in the group failed to move (R. 19,

30). A short time later Officer Byars told petitioner and

his group a third time to move and upon petitioner’s

failure to comply he was arrested (R. 19). There were

still eight to twelve persons in the group when told the

third time to move (R. 19, 30, 35, 42, 51, 61, 62, 76). Peti

tioner did not move after being told the third time that

the sidewalk was blocked, but indicated a determination

not to move by stating: “ You mean to tell me we can’t

stand here in front of this store?” (R. 19). At this time

Officer Byars arrested petitioner (R, 19).

Section 1142 as amended and Section 1231 have been

set out earlier in this brief. Since the evidence must also

be sufficient under the counts charging the violations, we

shall consider the evidence in light of the complaint.

Count One is essentially as follows:

“ Comes the City of Birmingham . . . and com

plains that F. L. Shuttlesworth, . . . did stand, loiter

or walk upon a street or sidewalk within and among

a group of other persons so as to obstruct free pas

sage over, on or along said street or sidewalk . . .

or did while in said group stand or loiter upon said

street or sidewalk after having been requested by a

police officer to move on . . . ”

It is clear that under count one of the complaint the

evidence was sufficient.

Petitioner in his brief does raise one other proposition

which should be discussed. He argues that there was no

obstruction as contemplated by Section 1142 as amended.

In order to properly define the term “ obstruct” as used

in Section 1142 as amended, the Court should first deter

mine the objects of the statute and then direct its defini

tion of the term toward those ends. State v. Lucas, Miss.,

221 Miss. 538, 73 So. 2d 158. In the light of this rule, it is

clear that “ obstruct” does not mean a total or complete

blocking of the sidewalk. This is apparent from the lan

guage used in the ordinance as well as the objects sought

to be attained by this regulation. The term “ obstruct

free passage” definitely contemplates something less than

a total or complete blocking of pedestrian traffic. All

that is required is that the “ free passage” of pedestrians

be hindered or impeded. The object of the regulation is

to permit freedom of travel to pedestrians walking along

the sidewalk.

Obviously no complete blocking of pedestrian traffic is

contemplated. Even where large crowds gather to listen

— 8 —

to speeches there is no complete blocking of movement.

It is possible at the largest of these assemblages to squeeze

through the crowd. Clearly the word “ obstruct” in the

context in which it is used and the object sought to be

attained means no more than to hinder or impede the

passage of persons on the sidewalk. If the term “ free”

as used in “ free passage” has any meaning at all it must

be construed so as to limit the term “ obstruct” as indi

cated.

Petitioner sets out a portion of the testimony, contend

ing it establishes that there was no obstruction. The

portion of the testimony set out by petitioner does not

even support an inference that there was no obstruction

of passage. In fact, if we enlarge just slightly upon the

portion of the record set out in petitioner’s brief, we find

it completely inconclusive of anything.

“ Q. Now, Mr. Byars, they were standing about

where you drew that little x mark?

A. That is where the defendant, Shuttlesworth, was.

Q. Well, we are only concerned with these defend

ants, Mr. Byars. We don’t know what other persons

made up the crowd.

A. Would you restate the question?

Q. I saw (six) assuming the defendants were stand

ing where you drew that little mark there, that would

have left more than half of your north-south cross

walk free, would it not?

A. That is true.

Q. And they didn’t block the east-west cross-walk

at all, did they?

A. They did not” (R. 22, 23).

From the foregoing it is uncertain whether the witness

was just describing that portion of the sidewalk blocked

by the petitioner and James Phifer or the entire group.

Petitioner and Phifer were the only ones on trial and it

— 9 —

is quite likely the witness was telling about the portion

of sidewalk blocked by these two persons, exclusive of

the crowd. This seems the only logical conclusion in light

of counsel’s statement to the witness: “ Well, we are only

concerned with these defendants, Mr. Byars. We don’t

know what other persons made up the crowd.”

A. In the case before this Honorable Court it was not

essential that petitioner, by himself constitute an obstruc

tion. If his conduct in unison with that of his companions

caused an obstruction, then he was guilty. It will be noted

that the second paragraph of Section 1142 as amended

specifically covers such a situation:

“ It shall be unlawful for any person or any number

of persons to so stand, loiter, or walk upon any street

or sidewalk in the City as to obstruct free passage

over, on or along said street or sidewalk. . . . ”

It is clear under the terms of the ordinance that the

petitioner could not stand or loiter with his companions

so as to obstruct the free passage of pedestrians without

being in violation of Section 1142 as amended. The evi

dence is clear that petitioner was a member of a group

that was standing and listening and talking (R. 19). It is

equally clear that petitioner considered himself a part

of this group because when told to move on the second

occasion petitioner stated: “ You mean to say we can’t

stand here on the sidewalk” (R. 19, 30)? Common sense

and logic dictate that this police officer, after observing

this group for about one and one-half minutes, could tell

that petitioner’s group was all together. The only other

conclusion that could be drawn is that those persons

allegedly not in the group were either themselves ob

structed by petitioner’s group or had stopped to listen

to them talk. In either event the conclusion is inescapable

that petitioner was in violation of Section 1142 as amended.

— 10 —

— 11

Let us now turn to count two of the complaint to see

if the evidence presented is sufficient under this count.

Count Two is essentially as follows:

“ Comes the City of Birmingham . . . and complains

that F. L. Shuttlesworth . . . did refuse to comply

with a lawful order, signal or direction of a police

officer . . . ”

The “ lawful order, signal or direction” in this case

directed the petitioner to “move on” . Under the circum

stances existing at the time of the order, it was certainly

lawful.

The general scope and authority of a police officer in

giving orders in the performance of his duty was dis

cussed in State v. Taylor, 119 A. 2d 36, 38 N. J. Super. 6,

in the following language:

“ . . . The duty of police officers, it is true, is ‘not

merely to arrest offenders, but to protect persons

from threatened wrong and to prevent disorder. In

performance of their duties they may give reasonable

directions.’ People v. Nixon, 248 N. Y. 182, 188, 161

N. E. 463, 466. Then they are called upon to deter

mine both the occasion for and the nature of such

directions. Reasonable discretion must, in such mat

ters, be left to them, and only when they exceed that

discretion do they transcend their authority and

depart from their duty. The assertion of the rights

of the individual upon trivial occasions and in doubt

ful cases may be ill-advised and inopportune. Failure,

even though conscientious, to obey directions of a

police officer, not exceeding his authority, may inter

fere with the public order and lead to a breach of the

peace.” People v. Galpern, 259 N. Y. 279, 181 N. E.

572, 83 A. L. R. 785 (Ct. App. 1932).

“Failure to obey a police order to ‘move on’ can be

justified only where the circumstances show conelu-

lively that the order was purely arbitrary and was

not calculated in any way to promote the public

order. As was said in the Galpern case, the courts

cannot weigh opposing considerations as to the wis

dom of a police officer’s directions when he is called

upon to decide whether the time has come in which

some directions are called for.”

The evidence in this case revealed that petitioner and

his group not only obstructed the sidewalk, but obstructed

It to such an extent that people using the sidewalk had to

walk out into the street to get around the group. Peti

tioner’s conduct was such as to cause an interference with

vehicular traffic as well as pedestrian traffic, and was well

within any limitation imposed by virtue of Section 1231

being located in the Chapter of the City Code titled

“ Traffic” . Phifer v. City of Birmingham, . .. Alabama

App. . . ., 160 So. 2d 898.

Under his first question petitioner argues that the real

reason for his arrest was because of his civil rights ac

tivities in the City of Birmingham. He implies that he

was unable to put into evidence the fact that there was

a selective buying campaign going on in Birmingham on

the part of the Negro community. It is immaterial

whether the sustaining of an objection to such evidence

would be error because the fact of a selective buying

campaign was introduced into evidence as shown at pages

25, 26, 66, 81, 125 and 136 of the transcript. Petitioner

cannot complain of any error in this regard because his

questions were answered and these answers were con

sidered by the court.

Not only was petitioner not arrested for his civil rights

activities, but it can logically be argued that because of

his civil rights activities, he actively sought arrest to

further those same ends. In other words he had a better

motive to seek arrest than did the traffic officer who ar

— 12 —

13 —

rested him. Each time petitioner has been arrested for

any offense, it can reasonably be contended that it en

hanced and increased his prestige in all his civil rights

activities, and quite likely increased his potential for

acquiring contributions to support these activities.

Second Question.

Petitioner’s second point or question is equally without

merit. He contends that Sections 1231 and 1142 as amended

are vague in their application to his conduct; and con

sequently, deprive him of rights protected by the Four

teenth Amendment.

If, as contended by petitioner, his only offenses were

talking back to the officer and taking part in Civil Eights

activities, then clearly the application of these ordinances

to his conduct would be unconstitutional. The facts just

don’t bear this out. By coincidence, as the record shows,

the petitioner did talk back to the officer at the same time

he was committing the offense charged. Actually the

evidence discloses the petitioner -was told to move three

times and three times he failed to move, thus violating.

Sections 1231 and 1142 as amended three times.

The petitioner was not convicted on an ordinance that

as applied to his conduct was vague and uncertain. The

defendant has a substantive right:

“ . . . to be informed by the indictment or informa

tion in simple, understandable language of the crime

he is charged with and the acts constituting the

crime, in sufficient detail to enable him to prepare his

defense and to be protected in the event of double

jeopardy.” 27 A. Jur., Section 57, p. 623.

In the instant case the complaint based upon the two

ordinances sufficiently inform the petitioner of the nature

of the crime and the acts he is charged with having com

mitted in sufficient detail and manner for him to prepare

his defense and be protected from another prosecution for

the same offense.

A good discussion of the certainty required of the lan

guage employed in statutes is found in 22 Corpus Juris

Secundum, Section 24 (2) at page 67:

“ In determining whether a statute meets the re

quirement of certainty, the test is whether the lan

guage conveys sufficiently definite warning as to the

proscribed conduct when measured by common under

standing and practices. Absolute certainty is not re

quired in a criminal statute, and the standards of

guilt proscribed therein need not be so precise as to

be capable of reduction to an exact mathematical

formula or of mechanical application . . ., and a

standard of conduct under statute need not be defined

with such precision that those affected by it will

never be required to have to hazard their freedom

on correctly foreseeing the manner in which a matter

of degree may be resolved by a jury . . . ”

Any doubt, if there ever was any, concerning the cer

tainty of Section 1231 was removed by the limitation

placed on this section by virtue of its location in that

chapter of the City Code entitled “ Traffic” . Phifer v.

City of Birmingham, . . . Ala. App. . . . , 160 So. 2d 898.

As noted in Garner v. State of Louisiana, 82 Sup. Ct. 248,

368 U. S. 157:

“ Whether state statutes are to be construed one

way or another is a question of state law, final de

cision of which rests, of course, with the Courts of

the State. ’ ’

Under the construction placed on Section 1231 by the

Appellate Court in Alabama, there is no basis left upon

which to argue the vagueness and uncertainty of that

section. Phifer v. City of Birmingham, . . . Ala. App. . . . ,

160 So. 2d 898.

— 14 —

— 15

Petitioner also contends at least inferentially, that when

the Alabama Conrt of Appeals restricted the scope of

Section 1231 to traffic situations, it made its application

unconstitutional as to petitioner. He implies that under

authority of Bouie v. Columbia, . . . U. S. . . . , 12 L. Ed.

894 (1964), the limitation thus placed on Section 1231 was

unforeseeable and therefore deprived petitioner of fair

warning contrary to the “ due process” clause of the

United States Constitution. There is no comfort for peti

tioner in that case. The Court in the Bouie case held

that the judicial enlargement of an ordinance violated

the due process clause of the Constitution, and also by

way of dicta held that the unforeseeable limitation by

judicial construction of a vague or broad statute also

failed to give fair warning and was thus a denial of due

process. Tour respondent submits that this statute is not

and never , has been subject to criticism for being vague

or too broad. If Section 1231 as presently written had

appeared in Chapter 35 of the City Code dealing with

“ Offenses—Miscellaneous” , it would not have been re

stricted to traffic situations and would not have been so

broad as to be vague. Respondent also insists that the

rule of construction applied in the Phifer case is com

pletely consistent with the prior decisions of the Alabama

Appellate Courts and was easily foreseeable. In the case

of Philyaw v. City of Birmingham, 36 Ala. App. 112, 54

So. 2d 619, we find the following statement of the same

rule:

“ All City ordinances appearing in the same chapter

of a city code are in pari materia, and must be con

strued together and, if possible, be interpreted so as

to be in harmony. Sloss-Sheffield Steel and Iron Co.

v. Allred, 247 Ala. 499, 25 So. 2d 179.”

Section 1231 appears in Chapter 51 of the General Code

and is entitled “ Traffic.” All sections in this chapter

relate in some manner to traffic. The section immediately

16 —

preceding Section 1231 when construed with said section

does a great deal to clarify the restriction imposed in the

Phifer case.

“ Section 1230. Police to direct traffic; directing in

event of fire or emergency.

“ It shall be the duty of the police department to

enforce the provisions of this chapter. Officers of the

police department are hereby authorized to direct,

all traffic either in person or by means of visible or

audible signal or sign in conformance with the provi

sions of this chapter; provided that in the event of a

fire or other emergency or to expedite traffic or safe

guard pedestrians, officers of the police or fire depart

ment may direct traffic, as conditions may require,

notwithstanding the provisions of this chapter.”

It is clear when section 1231 is construed in pari ma

teria with section 1230 and all the other sections appearing

in this chapter, that it is limited to traffic situations. It

is equally clear that such a traffic situation existed in this

instance because pedestrians were compelled to leave the

sidewalk and walk out into the street to get around peti

tioner and his group.

As observed in Bouie v. Columbia, supra, the rule peti

tioner seeks to invoke, is limited to an unforeseeable rule

of construction which limits or restricts an otherwise vague

enactment:

“ The basic due process concept involved is the same

as that which the Court has often applied in holding

that an unforeseeable and unsupported state-court

decision on a question of state procedure does not con

stitute an adequate ground to preclude this Court’s

review of a federal question . . . The standards of

state decisional consistency applicable in judging the

adequacy of a state ground are also applicable, we

17

think, in determining whether a state court’s construc

tion of a criminal statute was so unforeseeable as to

deprive the defendant of the fair warning to which

the Constitution entitled him. In both situations, ‘ a

federal right turns upon the status of state law as of a

given moment in the past—or, more exactly, the ap

pearance to the individual of the status of state law

as of that moment . . . ’ ”

In this case, the petitioner was given fair warning. The

construction limiting section 1231 to traffic situations is

supported by the prior decisions of the State of Alabama,

and the application of this ordinance in this manner was

clearly foreseeable by petitioner.

Respondent respectfully submits that the opinion of the

Court of Appeals of Alabama is correct in all respects

and that Petitioner’s application for writ of certiorari

should be denied.

W. C. WALKER,

EARL McBEE,

Attorneys for Respondent.