Brown v. Board of Education Brief for Appellants in Nos. 1, 2 and 4 and for Respondents in No. 10 on Reargument - 25 Years Since Brown

Reports

January 1, 1979

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Brown v. Board of Education Brief for Appellants in Nos. 1, 2 and 4 and for Respondents in No. 10 on Reargument - 25 Years Since Brown, 1979. 9472ede1-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1a72cb3b-5b1b-46d0-9693-9ce176ca69fc/brown-v-board-of-education-brief-for-appellants-in-nos-1-2-and-4-and-for-respondents-in-no-10-on-reargument-25-years-since-brown. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

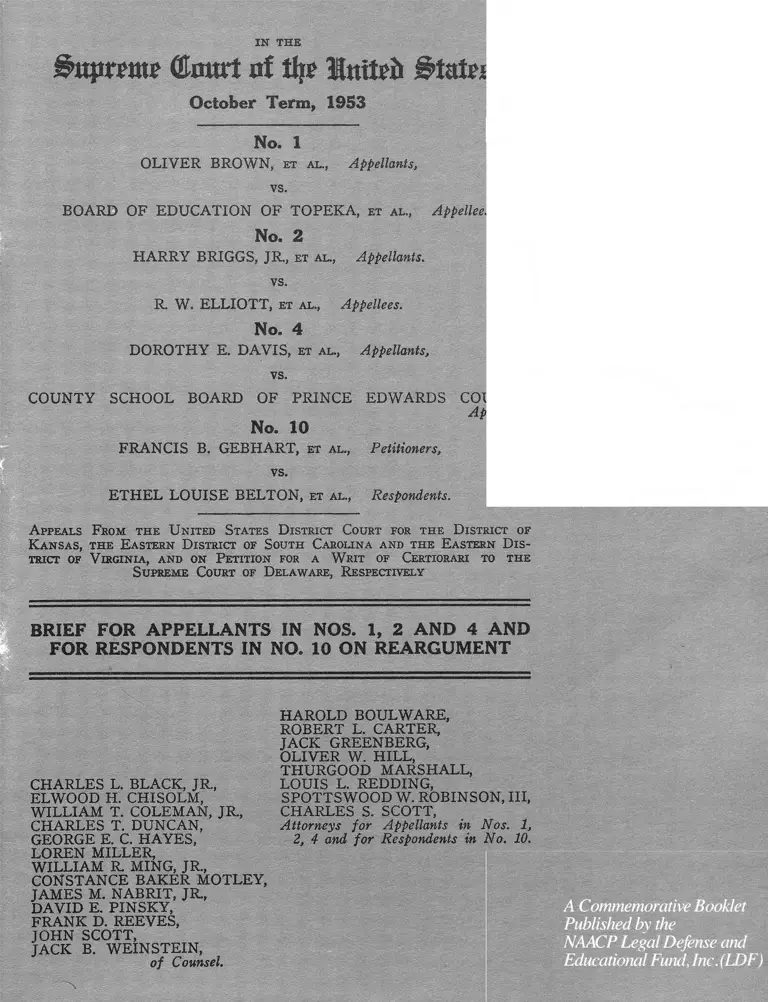

IN THE

ffimtrt of % &tatw

October Term, 1953

Mo. 1

OLIVER BROWN, e t a l ., Appellants,

vs.

BOARD OF EDUCATION OF TOPEKA, e t a l ., Appellees,

No. 2

HARRY BRIGGS, JR , e t a l ., Appellants.

vs.

R W. ELLIOTT, e t a l ., Appellees.

No. 4

DOROTHY E. DAVIS, e t a l ., Appellants,

vs.

COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD OF PRINCE EDWARDS COUNTY,

Appellees.

No. 10

FRANCIS B. GEBHART, e t a l ., Petitioners,

vs.

ETHEL LOUISE BELTON, e t a l ., Respondents.

%f "....

: ; ; . . >■

i j jijp s i

' t :: — ' i; '•

‘ :,a

A p p e a l s F r o m t h e U n i t e d S t a t e s D i s t r i c t C o u r t fo r t h e D i s t r i c t o f

K a n s a s , t h e E a s t e r n D i s t r i c t o f S o u t h C a r o l i n a a n d t h e E a s t e r n D i s

t r ic t o f V i r g i n i a , a n d o n P e t i t i o n fo r a W r i t o f C e r t io r a r i t o t h e

S u p r e m e C o u r t o f D e l a w a r e , R e s p e c t i v e l y

■

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS IN NOS. 1, 2 AND 4 AND

FOR RESPONDENTS IN NO. 10 ON REARGUMENT

CHARLES L. BLACK, JR.,

ELWOOD H. CHISOLM,

WILLIAM T. COLEMAN, JR.,

CHARLES T. DUNCAN,

GEORGE E. C. HAYES,

LOREN MILLER,

WILLIAM R. MING, JR.,

CONSTANCE BAKER MOTLEY,

JAMES M. NABRIT, JR.,

DAVID E. PINSKY,

FRANK D. REEVES,

JOHN SCOTT,

JACK B. WEINSTEIN,

of Counsel.

HAROLD BOULWARE,

ROBERT L. CARTER,

JACK GREENBERG,

OLIVER W. HILL,

THURGOOD MARSHALL,

LOUIS L. REDDING,

SPOTTSWOOD W. ROBINSON, III,

CHARLES S. SCOTT,

Attorneys for Appellants in Nos. 1,

2, 4 and for Respondents in No. 10.

Table of Contents

The NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE &

EDUCATIONAL FUND is not part of the

National Association for the Advancement of

Colored People although it was founded by it

and shares its commitment to equal rights. LDF

has had for over 20 years a separate Board,

program, staff, office and budget.

Foreword—Jack Greenberg ..............................................

Opening Statement—Ambassador Andrew Y oung........

Priorities Now—The Needs Today .................................

Commentary

Vernon E. Jordan, Jr. ......................................................

Robert Coles, M .D...........................................................

Bayard R ustin ...................................................................

Before B ro w n .....................................................................

Commentary

Richard K luger.................................................................

The Brown Decision..........................................................

Commentary

Charles L. Black, Jr. ......................................................

Judge A. Leon Higginbotham ........................................

Clifton R. Wharton, Jr. ..................................................

Roy Wilkins .....................................................................

Since B ro w n .......................................................................

Commentary

Wiley A. Branton.............................................................

James C. Comer, M.D......................................................

James L. Curtis, M.D.......................................................

Dorothy Height ...............................................................

Since Brown (continued) ....................................................

Commentary

Anthony Amsterdam ......................................................

William Sloane C offin ....................................................

Charles V. Hamilton ......................................................

Patricia Roberts H arris ....................................................

Nicholas DeB. Katzenbach ............................................

James Vorenberg ............................................................

Roger Wilkins .................................................................

Legal Talent .......................................................................

Commentary

Michael I. Sovern............................................................

The Legal Defense Fund as Model .................................

Commentary

Vine DeLoria, Jr. ..........................................................

Margaret Fung .................................................................

Father Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.M...........................

Vilma Martinez ...............................................................

The Legal Defense Fund Today.......................................

Financing Legal Redress ..................................................

Closing Statement— Excerpts from Earl Warren Address,

May 15, 1970 .....................................................................

. 2

3

5

5

8

9

11

15

17

21

22

22

23

25

. . . 32

. . . 33

. . . 34

. . . 34

. . .35

. . . 42

. . . 42

. . . 43

. . . 44

. . . 44

. . . 45

. . . 45

. . . 47

. . . 47

. . .53

. . . 54

. . . 54

. . . 55

. . . 56

. . . 51

. . .62

. . .6 4

Foreword

When anniversaries roll around, one

tends to look in two directions—over the

years passed, and ahead to the uncertain

future. In these summary pages, the

Legal Defense Fund and some of its

good friends do both.

As 1 look back to 1954, I wonder what

life in America would be like today if in

the Supreme Court’s deliberations the

Brown decision had gone the other way.

Legal segregation would have

remained institutionalized in much of

the country. The courts would not have

been a forum to effect transition from a

segregated to a nonsegregated society.

Public protests, such as that of Martin

Luther King, would have met the same

hostile resistance. But the courts

probably would not have protected Dr.

King, as they did in over forty Supreme

Court cases brought by LDF. And.

therefore, legal and nonviolent means

would have scarcely been available to

America’s black citizens in their quest

for equality. America very well might

have come to resemble Northern Ireland

or Lebanon.

Instead, by legal process and legal

protest, the nation turned the comer from

being two inexorably separate societies,

black and white, towards becoming one

nation where skin color and the heritage

of slavery one day will make no

difference in a person’s life.

Nevertheless, a massive task remains

ahead of us. School segregation lingers

in the South and is widespread in the

North. Employment discrimination

slowly crumbles but also resists change,

so that black unemployment is double

that of white, black youth unemployment

four-fold. Housing segregation yields

grudgingly. The criminal justice system

disadvantages the poor and black. But

we continue to make precedents that

combat injustice, create greater equality

and offer hope.

We are effective insofar as our

resources permit. We are grateful for

the steadfast past support of our friends,

and ask you to uphold our efforts now

and in the years ahead.

Jack Greenberg, Director-Counsel

NAACP Legal Defense Fund

2

Andrew Young, United States Ambassador to

the United Nations, is the former member of the

U.S. House of Representatives who worked

closely with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in the

Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

T H E R E P R E S E N T A T I V E

OF THE

U N I T E D S T A T E S O F A M E R I C A

TO THE

U N I T E D N A T I O N S

The revolution in race relations in the United States over the last quarter century could

not have been achieved without a vast and imaginative offensive through the judicial

process. The Legal Defense Fund was always at the forefront of that undertaking.

My own perspective on this legal effort came from participation in the nonviolent mass

movement with its multiple strategies of citizenship education and voter registration,

community organizing and economic boycotts, demonstrations and negotiations, civil

disobedience and jail-ins. Time and time again, the movement called upon the Legal

Defense Rind for assistance, and the Fund’s lawyers responded with an aggressive use

of Constitutional law and a consummate skill which prevailed in a wide variety of

landmark cases.

Perhaps more than any other lawsuit, Brown v. Board of Education laid the groundwork

for a body of law which is still growing, still strengthening our democratic institutions,

still affirming and protecting the whole range of human rights that are the aspiration of

all people everywhere in the world.

Twenty-five years ago, few people foresaw the potential for the larger meaning of the

Brown case—the possibility that the legal process, when properly utilized in a

democratic society, could undergird a mass movement for social change and lead to

epochal victories for the rights of all citizens. That is the legacy of Brown and the Legal

Defense Fund, a legacy that inspires people the world over and energizes the global

quest for human rights.

That alone is enough to enshrine the Legal Defense Fund as a bastion of the rule of law,

and a beacon of freedom with justice.

Andrew Young

3

In commemoration of the 23rd anniversary of

Brown v. Board of Education and to lend support

to LDF’s three-year 40th anniversary national

campaign, President Carter met with this group at

the White House on May 18, 1977. Pictured from

left to right are: ViCurtis Hinton, Coordinator,

LDF-Washington Committee; Julius L. Chambers,

President, LDF; William T. Coleman, Jr.,

Chairman of the Board, LDF; John Filer,

Chairman, Aetna Life and Casualty and Chairman,

40th Anniversary Campaign; President Carter;

Martha Mitchell, then Special Assistant to the

President for Special Projects; Jack Greenberg,

Director-Counsel, LDF; Ernest G. Green, Assistant

Secretary, Employment and Training, U.S.

Department of Labor and one of the nine high

school students who integrated Central High

in Little Rock, Arkansas; Betty J. Stebman,

Development Staff, LDF; E. B. Knauft, Vice

President, Corporate Social Responsibility, Aetna

Life and Casualty; James Ghee, Esquire, of

Farmville, Virginia; and Lucinda Todd, retired

elementary school teacher, former secretary of the

Topeka branch of the NAACP and a leader in

initiating the Brown suit.

4

Priorities Now—The Needs Today

Vernon E. Jordan, Jr. is President of the

National Urban League. He headed the staff of

the United Negro College Fund and of the Voter

Education Project.

Their Urgency

The Legal Defense Fund’s immediate and

long-term priorities were never more

necessary to the well-being of our entire

country than they are today. Whether

we consider the problems of the economic

dilemma of the United States, the physical

and mental health of our people or our

deteriorating cities, the legal struggle to

make equal opportunity a practical reality

is fundamental to the finding of solutions.

The National Urban League has applied

intelligence and energy to improve the

working conditions of black Americans

and other disadvantaged minorities for

seven decades. In the three centuries of

black experience in the United States,

we have achieved tangible and measurable

progress toward equal treatment only in

the past thirty years. The Brown decision

was a quantum leap. But, although the

Supreme Court and the Congress wrote

the principle of equality into the

enforceable laws of the nation, translating

those laws into reality is still painfully

slow.

An intolerable level of one in four black

persons ready to work but unemployed,

the rising numbers of impoverished black

children, the largely unredeemed promises

of decent housing and delivery of quality

medical care to those who need it most,

a widening gap between the incomes of

black and white families, and the growing

indifference to the need for workable,

effective measures that improve the lot of

people all mock any assumptions that we

share a national commitment to the

enjoyment of equal rights.

Contrary to a widely held belief,

benefits from general progress in recent

decades have reached only a small part of

the black community. True, there is a

growing number of blacks in college, in

management positions, and the

professions. But so long as 28 percent of

black families have still to climb above the

poverty level, we have a very long way to

go-

And not much time.

Vernon Jordan

Twenty-five years after the Supreme

Court’s historic Brown decision

outlawing racially segregated public

schools, what is happening to America’s

commitment to equal justice?

There is rising reaction against hard-

won gains. Too many legislators,

government officials, even some jurists,

remain callous to deprivation and

injustice. As one federal Judge has

observed, rights of the black and poor

are being measured “with a

micrometer” .

The Legal Defense Fund will sustain

the fight. In litigation and in negotiation

we continue the national struggle for

equal access to employment, against

capital punishment—the most racially

discriminatory penalty, for further strides

desegregating education, housing, for

rights of the imprisoned, for equality in

medical care and voting rights, and the

steady growth of an experienced civil

rights bar.

Employment

Notwithstanding civil rights laws

passed since 1957, and key court

decisions the Fund has won, minorities

still have immense difficulty getting jobs

and overcoming barriers to advancement.

For the same or more work, too often

they receive less. Since its creation in

1964, the federal Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission (EEOC) has

accumulated a backlog of 130,000

complaints. Some date back as long as

seven years.

5

The EEOC has begun crash efforts to

reduce this glut. Expediters use

computers. The Fund intends to make

sure that, in belated haste, equal

employment opportunity is not lost in an

avalanche of paper.

The LDF assigns about half of its

work toward the right of minority

Americans to get and hold jobs on their

individual merits.

As job markets tighten, court

challenges become more intricate. The

May 1977 Supreme Court decision in

International Brotherhood of Teamsters

v. United States denied relief on the

ground that seniority systems had no

intent to discriminate. This may lock an

entire older generation of minority men

and women into an inferior least-paid

underclass.

Brian Weber’s suit against Kaiser

Aluminum and the United Steelworkers,

charges reverse discrimination. Bakke's

case similarly charged reverse

discrimination in medical school

admissions. Strenuous effort has fended

off the “ reverse discrimination

backlash” , but it still presents the threat

of stiffling affirmative action programs.

One attack on voluntary affirmative

action would require employers to admit

earlier discrimination that invites claims

for back pay.

Nearly all the hundreds of current

LDF employment suits are class actions.

They affect the chances of thousands of

minority workers to enter the

mainstream of the nation’s work force

and to progress on their worth. In one

recent year, the Fund appeared in 23

such employment cases in the Supreme

Court.

Discrimination by Government. The

1972 Equal Employment Opportunity

Act aims to “eradicate entrenched

discrimination in the Federal Service.”

Federal workers must first exhaust

procedural remedies through the Civil

Service Commission before recourse to

court. There were long delays, elaborate

rigmarole, few results. Hundreds of

Justice Department lawyers stalled

reform, until the LDF won a December

1975 court judgment compelling the

Commission to permit class actions.

With the 1978 Barrett case, the

Commission was ordered to resolve class

complaints it had refused to recognize.

A unanimous Supreme Court ruled in

Chandler v. Roudebush: Federal

employees’ job discrimination

complaints are now entitled to full trials,

just as workers in the private sector are.

The Fund has stepped up 20 class action

suits.

The discriminatory PACE

(Professional and Administrative Career

Examination) is now a central issue in

public employment. It screens applicants

for hundreds of thousands of middle

level civil service positions. On the West

Coast, only one per cent of black, and

no Hispanic, test-takers passed PACE.

LDF and others have filed a legal

challenge to the continued use of PACE.

Twenty-seven active LDF cases attack

job bias by states and cities. The Fund is

defending the City of Detroit against two

suits filed by white police officers’

organizations. The survival of

affirmative action policies, begun in

1974 by Mayor Coleman Young to

change discriminatory police hiring and

promotions, is at stake.

Capital Punishment

The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals has

rejected legal arguments against death

penalty laws developed since 1976. The

Supreme Court declined to review the

decision in the case of John Spinkellink,

a prisoner condemned to death. If not

granted clemency, the state of Florida

can electrocute him in 1979. That can

also pave the way for the six Fifth

Circuit states to proceed with execution

of 363 prisoners now on death row in the

six deep South states. In these six states

half of the condemned prisoners are

black or Hispanic.

The Fund intends to prove that the

application of newly enacted capital

punishment laws is arbitrary and racist.

In 1978, the Fund continued direct

defense of more than 50 defendants

charged with capital crimes. John

Irving’s case challenges Mississippi’s

new law: one of the factors considered in

sentencing him to death was that he had

once been sent home from school as

discipline. Whether Texas state

psychiatrists could lawfully examine

defendants before trial and then after

conviction testify as to their admission in

an effort to secure the death penalty is at

issue in Ernest Benjamin Smith’s case.

The LDF assists lawyers now

defending hundreds of the nearly 500

men and three women now under death

sentences in 25 states. The LDF seeks

out volunteer lawyers for condemned

prisoners who are without counsel. It

helps with strategy, exchange of

information, and briefs.

Education

In graduate professional and

undergraduate college education the LDF

is making sure that past progress does

not succumb to new attempts that will

circumvent court-ordered desegregation.

The Fund has helped the U.S.

Department of Health, Education and

Welfare (HEW) define clear criteria, so

that the long delayed desegregation of

state-wide public university and college

systems will go forward. These should

eliminate wasteful curricular duplication

while also strengthening predominantly

black colleges.

To ensure effective progress, we

monitor federal enforcement and state

compliance.

The LDF is also working with

admissions officers of medical schools.

Since 1978, some professional school

affirmative action programs have

regressed, probably in reaction to Bakke.

We are showing them how, in

compliance with law, they can continue

to admit minorities affirmatively.

In elementary and secondary public

schools we press forward to:

• maintain desegregation won earlier

in the South;

• see to it that all-white

“segregation academies” do

not receive tax-deductibility while

continuing to evade the law;

• move against segregated Northern

schools;

• defend black educators from

discriminatory firings and

demotions;

• eliminate “ tracking” and “ ability

group” practices designed to

segregate black children;

6

® prevent arbitrary and illegal

suspension and expulsion of black

pupils;

• eliminate racially slanted teaching

materials; and

• stamp out race and sex

discrimination in state-supported

vocational schools.

Housing and Land Use

Lacking real enforcement, the federal

Fair Housing Law fails to protect

families refused sale or rental of places

to live solely because of race. LDF now

strongly supports efforts of the U.S.

Department of Housing and Urban

Development (HUD) to secure legislative

authority to get cease and desist power

against housing discrimination.

Since late 1977, the HUD has rated

the laws and complaint procedures of 24

states and the District of Columbia as

“ substantially equivalent” to remedies

prescribed by law. Having earlier found

the diligence of these states and D.C.

less deserving, the Fund consults closely

with the U.S. Commission on Civil

Rights staff, monitoring the actual

performance under such laws and

helping aggrieved home-seekers.

In the absence of effective federal

protection, LDF continues to bring cases

that serve as class actions affecting many

thousands of families. We negotiated a

consent decree with one real estate

company to pay damages for past

discrimination and to report periodically

on how its affirmative action program

works. The LDF has sued five other

firms and the 300-member Delaware

County Board of Realtors in

Pennsylvania. The Board covers 15

almost exclusively white towns and one

nearly all-black area outside

metropolitan Philadelphia.

LDF has sued four major Brooklyn

real estate firms and the largest New

Haven, Connecticut realtors for racial

steering. Evidence shows they

discouraged white families from buying

in areas where blacks live, and steer

prospective black residents away from

white suburbs.

We hope to build on the victory won

in the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals in

the Harper case (a black couple refused

a Nashville apartment); our purpose is to

establish need for objective standards, so

that prospective tenants will receive

equal treatment.

As in the past, we will continue the

efforts begun in California where LDF

established a two-pronged approach to

housing cases: an exceptionally large

volume of cases was brought and

publicized as a way to signal that

vigorous enforcement against

discriminators was underway; as a

further deterrent, we succeeded in

raising substantially the amount of

damages awarded in housing

discrimination cases.

HUD has said it welcomes, but has

not yet adopted, LDF recommendations

to stop redlining—the systematic denial

of mortgage credit in predominantly

black neighborhoods. We filed a friend-

of-the-court brief against federal savings

and loan banks’ attempt to escape

California’s law against redlining.

Although federal District and Supreme

Court decisions have frustrated minority

interests in urban renewal, highway, and

regional development schemes, the Fund

still brings new suits. These scrutinize

relocation programs, exclusionary

planning, and allocation of federal

money in the light of damage they inflict

on black neighborhoods.

Prisoner Rights

Having established the principle that

prisoners have constitutional rights— and

having long served as one of the

principal private resources in the U.S.

engaged in comprehensive legal action to

remedy local jail conditions where

degredation and brutality are normal—

the Fund’s task now is to make certain

that court-ordered changes happen.

The June 1978 Supreme Court

decision in Finney v. Hutto followed a

decade of litigation in which some years

ago the entire Arkansas prison system

was held unconstitutional. The 1978

decision found that indefinite solitary

confinement violates the Constitution’s

prohibition against cruel and unusual

punishment.

In 1979 we are challenging the

overcrowded racist Texas prison system.

We pursue further relief of caged men,

women, and children in the wake of

decisions won to date in Alabama,

Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana,

Massachusetts, New York, Ohio,

Pennsylvania, Rhode Island and

Tennessee, affecting state, county, and

city prisons.

Medical Care

As many as 17 private nonprofit

community hospitals may be spending

federal Hill-Burton money to build

suburban “branches” , while the services

they once provided to minority and poor

inner city people become vestigial

remnants.

Acting as counsel for Mayor Richard

Hatcher of Gary, Indiana, and other

black citizens the Fund sued Methodist

Hospital and HEW. The hospital had

moved the preponderance of its facilities

15 miles to Merrillville, where 90

percent of patients are white. The federal

District Court has ordered that the

tentative settlement terms LDF

negotiated not yet be made public.

In 1979 the LDF will represent the

city of San Antonio, Texas, and a

constellation of citizen organizations.

Issues similar to those in Gary head for

trial. The focus is on transfer of inpatient

maternity services to an inaccessible

white suburb. For the first time the U.S.

Department of Justice will enter such a

case, contesting relocation of a runaway

hospital and consequent reduced delivery

of medical treatment to sick, poor and

old people.

The Vote

After protracted litigation, citizen

action, and national legislation, minority

citizens can register and vote. In some

localities reapportionment discounts the

black constituency’s votes despite the

Constitutional requirement that each

citizen’s vote be given equal weight.

Multi-member districts in combination

with at-large elections dilute minority

voting strength.

Supreme Court decisions up to now

may tolerate a double standard. City

residents seeking redress against

overrepresented less populated rural

districts can prove violation of the one-

7

person, one-vote principle with simple

statistical evidence. The minority

plaintiff must prove racial motivation to

strike down discriminatory

malapportionment.

The LDF has a dozen active cases in

six states that seek to correct minimized

minority participation in government.

Legal Training

LDF’s Earl Warren Legal Training

Program is providing scholarships for

190 students at more than 50 law schools

in the 1979-1980 academic year. Since

our legal scholarship program began, it

has helped send 1,121 black lawyers

through law school.

The Fund is well prepared, but needs

funds to resume its Civil Rights Legal

Training Institutes for practicing lawyers.

These can again be an invigorating

means to hone and coordinate legal

actions being brought to court across the

United States.

Robert Coles, M.D. is the psychiatrist who

wrote “Children of Crisis.” He is Professor,

Psychiatry and Medical Humanities, Harvard

University.

For twenty years I’ve been working with

American children in all parts of this

country, from various classes, races,

backgrounds, and I believe more strongly

than ever in the value, the importance of

school integration.

When I worked with the black and white

children of the South in the early 1960s,.1

saw the extremely difficult (and different,

depending upon race) hurdles they had to

face, in order to sit near each other in a

classroom. I often wondered whether

desegregation was worth the effort— all

that fear and anxiety and mutual distrust

and suspicion. Yet, over time those

children became not only pioneers in the

legal, constitutional sense, but young

people with a new sensibility— able to see

others, different by skin color, as

classmates, and eventually, particular

persons. I’ve tried to document that

process in the various articles and books

I’ve written, but in essence what I've kept

seeing has been children becoming not only

broader in their perceptions of others, but

larger human beings themselves.

I don’t know how better to describe

what school integration means than to

quote a white student in a Mississippi

school in 1970: “I've known black people

all my life: ‘the colored’, my folks would

say, or something else! Now there’s Louis

and there’s Freddie, and there’s Sally and

there’s Mary Ann, and each is different;

and I’ll bet they have our names in their

heads, not just a picture of a white, and

another white, and another white.” Is

there any more that needs saying?

We seek integration so that “a more

perfect union” may be accomplished, to

use an old American constitutional

statement. We seek, through integration,

not something in the abstract, not the

construction of a social or political theory,

but an ongoing experience, embedded in

the concreteness of everyday life, for our

American children.

Robert Coles

Bayard Rustin is President of the A. Philip

Randolph Institute. He took part in the first

Freedom Ride in 1947 testing enforcement of the

Irene Morgan case outlawing discrimination in

interstate travel. Arrested in North Carolina, he

served 30 days on a chain gang. He is a member

of LDF’s Board.

New Barriers To Minority

Employment

Twenty-five years ago when the Supreme

Court handed down its historic decision in

Brown v. Board of Education, the barriers

to minority employment and full

participation in American society were

shockingly clear. Throughout the South

and even in many Border states, blacks

and whites lived under a perverse legal

system shaped by the “separate but equal”

doctrine enunciated by the Supreme Court

in its 1896 decision in the Plessy v.

Ferguson case. Everywhere one went, the

tangible results of the 1896 decision could

be seen— signs designating separate

drinking fountains and rest rooms for

“coloreds” and “whites” abounded;

rigidly enforced segregation existed in

restaurants and public transportation;

and, of course, blacks and whites had

separate— and outrageously unequal—

schools for their children. The legal

barriers, then, were easy targets and the

program of the civil rights movement was

clear-cut, and highly specific.

With the proclamation of the Brown

decision and the dramatic civil rights

revolution of the 1960s, the situation

changed. For the most part, the legal

barriers which blocked the forward

movement of black people disappeared

and blatant racial segregation soon lost all

social legitimacy. Consequently, the civil

rights movement was forced to broaden its

focus, and move beyond the purely

legalistic aspects of racism.

Today, we once again face new and

rather difficult challenges in the area

of minority employment. Specifically, we

must begin to deal with issues like the

impact of international trade, the problems

arising from labor-saving technological

innovation, and the worsening

unemployment situation among minority

youth.

In short, our vision of minority

employment problems must be all-

encompassing. It must look toward

long-term social and economic trends, and

it must combine imagination with

pragmatism.

Bayard Rustin

G. W. McLaurin kept apart from University of

Oklahoma Graduate School of Education classmates

until the 1950 Supreme Court ordered relief.

10

Before Brown

The five 1954 School Desegregation

cases collectively known as Brown v.

Board of Education were the climax in a

long series of tests that ate away the legal

authority of enforced racial segregation

in the United States. The Legal Defense

Fund brief in Brown cited decisions from

the Supreme Court in several cases in

which the National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People

(NAACP) had taken part before the

NAACP Legal Defense Fund was

founded. Among these were:

Guinn v. U.S. (1915), outlawing the

1910 Oklahoma constitution’s “grand

father clause” preventing Negroes from

voting on the pretext that their ancestors

had not voted before 1866;

Buchanan v. Warley (1917), declaring

the Louisville residential zoning by

race was “ in direct violation of the

fundamental law enacted in the

Fourteenth Amendment of the

Constitution” ;

The White Primary cases, declaring

that blacks could not be excluded from

party primaries. In Nixon v. Herndon

(1927) Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes

said, “Color cannot be made the basis of

a statutory classification affecting the

right set up in this case.” In Nixon v.

Condon Justice Benjamin Cardozo

wrote, “The Fourteenth Amendment,

adopted as it was with special solicitude

for the equal protection of members of

the Negro race, lays a duty upon the

court to level by its judgement these

barriers of color.”

Volunteer attorneys argued NAACP

cases. Among them were Moorfield

Storey, former American Bar Association

president who had been secretary to

Charles Sumner, Arthur Spingarn, long

NAACP president and Clarence Darrow.

Starting in 1929 American Fund for

Public Service grants enabled Nathan

Margold, former Solicitor of the

Department of the Interior, to study how

legal action might reduce Negroes’ legal,

political, and economic disabilities.

Margold urged legal suits against

segregation as a tactic to force states and

boards of education “to provide ‘equal if

separate’ accommodations in white and

colored schools.” The NAACP retained

Charles H. Houston, then vice dean

of Howard Law School, to direct a

coordinated legal program; he worked

part-time through June, 1935, full time

until 1938, as Special Counsel to 1940,

and as national legal committee

chairman up to his death in 1950.

The lawyers who conducted the

suits— Dr. Houston, William H. Hastie,

Thurgood Marshall, and Howard Law

School colleagues—did not follow

Margold’s idea of first attacking

conditions in elementary and high

schools. They chose all-white tax

supported professional schools in the

South. They were the only such training

centers available in their states.

The Graduate School Cases began

in 1935 when Thurgood Marshall

persuaded the Maryland Court of

Appeals to order Donald Murray

admitted to the University of Maryland

Law School.

In 1938 the U.S. Supreme Court

decided in Missouri ex rel Gaines v.

Canada that the University of Missouri

had to admit Lloyd Gaines to its law

school. Missouri had offered to pay the

difference between its tuition and the

rate at an out-of-state school. Chief

Justice Charles Evans Hughes dismissed

the excuse that there was not enough

demand to establish a law school for

Negroes. He said “ the State was bound

to furnish ... within its borders facilities

for legal education substantially equal to

those which the State there afforded for

persons of the white

race. . . ”

Gaines was a breakthrough. Soon

after the decision the NAACP felt there

would be greatly increased demand for

lawsuits. Costs would rise. It decided to

establish the new NAACP Legal Defense

and Educational Fund as a separate,

independent organization.

The NAACP Legal Defense Fund

incorporated in New York State on

March 20, 1940. On its first Board of

Directors were the seven incorporators:

William H. Hastie; Governor Herbert H.

Lehman of New York; President William

Allan Neilson of Smith College; Miss

Mary White Ovington, a founder of the

NAACP in 1909; Judge Hubert T.

Delaney; Judge Charles H. Toney; and

Arthur B. Spingarn. Esq., who was

elected as LDF’s first President on

March 27, 1940.

11

When the Board was expanded in

1941, it included, among others, Senator

Warren Barbour of Washington;

President John W. Davis of West

Virginia State College (who still works

with LDF 39 years later); Lewis S,

Gannett of the N.Y. Herald-Tribune;

John Hammond, the musician and

businessman; and Dean Charles H.

Thompson of Howard University

Graduate School.

Their purposes were to provide free

legal aid to Negroes suffering injustice;

to seek and promote educational

opportunities denied Negroes because of

race; to conduct research and publish

information on “educational facilities

and inequalities furnished for Negroes

out of public funds and on the status

of the Negro in American life.”

Three crucial Graduate School

Cases, 1946-1950, on the Way to

End Segregation

Sipuel v. University of Oklahoma was

the suit Ada Lois Sipuel brought in 1946

after being refused entrance to law

school. Her defeat in the trial court was

sustained by the State Supreme Court in

April, 1947. The trial record contained

testimony supporting her case from

leading law professors from Chicago,

Columbia, Harvard, and Wisconsin. The

LDF appealed to the U.S. Supreme

Court. Its brief argued:

“ From the ranks of the educated

professionals come the leaders of a

minority people. In the course of their

daily lives they transmit their skills

and knowledge to the people they

serve__The average Negro in the

South looks up to the Negro

professional with a respect that

sometimes verges on awe. It is

frequently the Negro professional who

is able to articulate the hopes

and aspirations of his people . . . ”

In 1948 the Supreme Court issued its

unanimous, unsigned per curiam

decision. Oklahoma had to provide Miss

Sipuel with a legal education “as soon

as it does for applicants of any other

group.” (emphasis ours)

The LDF case of Heman M. Sweatt, a

Texas mail carrier, against the University

of Texas was another giant step. After

Sweatt had repeatedly applied to the

University law school by registered mail,

the University hurriedly assembled a

“Texas Law School for Negroes” in four

basement rooms. At trial in federal

District Court, Fund lawyers exposed the

pretense of equality under claimed

“ separate but equal” expedients. The

segregated improvisation had nothing

like the great University law school’s

library, Law Review, moot courts, or

faculty reputation.

Significantly, Chief Justice Fred R.

Vinson’s 1950 decision emphasized that

the absence of white law students with

whom the future lawyer would practice

was a serious handicap. Substantial

equality, he said, could be achieved only

by admission to the University of Texas

Law School.

On the same day the Court decided

the LDF case of G. W. McLaurin. After

the University of Oklahoma Graduate

School of Education admitted him, it

made McLaurin sit in an anteroom

adjoining the main classroom. It

assigned him a desk on a stair landing in

the library, and required that he eat at a

table apart from fellow students. Chief

Justice Vinson spoke for the unanimous

Court, stating that McLaurin “must

receive the same treatment at the hands

of the state as students of other races.”

In both Sweatt and McLaurin the

Supreme Court refused to reconsider the

1896 Plessy formulation of “ separate but

equal.” The unanimous Court stated that

“ substantial equality” was not provided

when a student was kept separated from

other graduate students. The decision in

McLaurin recognized that his segrega

tion meant discrimination. That plainly

set the stage for Brown.

From the time the Fund had become a

separate entity in 1940 Thurgood

Marshall and his colleagues accelerated

their work for minority rights. In

education, the LDF sought and got

redress for discriminatory low pay to

black teachers. It acted against injustices

that persisted in voting, housing,

transportation and public accommoda

tions, employment, military and criminal

justice.

LDF cases resulted in a repertory of

precedents that made Supreme Court

avoidance of decision on the separate-

but-equal doctrine harder. A broad legal

framework evolved. Well before the

highest Delaware state court and the

federal District court in Kansas squarely

faced the segregation issue, there were

landmark decisions outlawing restrictive

covenants, juries that excluded blacks,

and interstate Jim Crow buses.

Black Teachers’ Pay

Between 1935 and mid-1938 when

Thurgood Marshall succeeded Charles

Houston as chief NAACP attorney in

New York, Marshall won equal-pay

agreements from nine of Maryland’s 23

county school boards. In 1939 he

brought suit on behalf of black principal

Walter Mills against the Anne Arundel

county board of education. U.S. District

Court Judge W. Calvin Chestnut found

evidence of discrimination

overwhelming. None of 91 Negro

teachers received as much pay as any of

243 white teachers with similar

qualifications and experience.

Chestnut’s judgment stated that such

discrimination “ violated the supreme law

of the land.” Anne Arundel County did

not appeal. At the Governor's request the

state legislature made racial pay

differentials illegal across Maryland.

Alston v. School Board of City of

Norfolk (Fourth Circuit Court of

Appeals, June 18, 1940) was a key LDF

victory. Melvin O. Alston, a high school

teacher with five years’ experience, was

being paid $921 per year while white

male Norfolk high school teachers

received $1,200. Relief was ordered by

the appellate court and the U.S.

Supreme Court refused to review.

The Right to Vote

To get around the 1915 Supreme Court

decision in Guinn, Oklahoma passed a

law that anyone who had been eligible to

register during a two-week period in the

spring of 1916 but had failed to do so

was forever ineligible to register to vote.

James M. Nabrit, Jr. challenged that law

in Lane v. Wilson which went to the

Supreme Court as an NAACP case in

1939. The Supreme Court stated, in a

Justice Frankfurter opinion, later quoted

in numerous court decisions, that the

12

1949

SEGREGATION AUTHORIZED OR REQUIRED B y STATE LAW

What Brown ended: state laws requiring and permitting segregation. SOURCE: Dr. Pauli Murray

Fifteenth Amendment forbids

“sophisticated as well as simple-minded

modes of discrimination.” It nullified

the Oklahoma law.

The Court had originally upheld the

Texas white primary in Grovey v.

Townsend in 1935. The LDF, on new

grounds, challenged that practice, and in

Smith v. Allwright the Supreme Court

held that such all-white primaries

violated the Fifteenth Amendment.

South Carolina attempted to evade the

Allwright ruling with repeal of every one

of 150 laws on its books governing

primary elections. When Thurgood

Marshall tried Rice v. Elmore in 1947

before the United State District Court in

South Carolina, Judge J. Waties Waring

forbade continued exclusion of Negores

from South Carolina primaries:

“ It is time for South Carolina to

rejoin the Union. It is time to fall in

step with the other states and adopt

the American way of conducting

elections.... Racial distinctions cannot

exist in the machinery that selects the

officers and lawmakers of the United

States.”

Housing: Restrictive Covenants

Ruled Unenforceable in Court

. .it shall be a condition all the time

and whether recited or referred to or

not in subsequent conveyances and

shall attach to the land as a condition

precedent to the sale of the same, that

hereafter no part of said property or

any portion thereof shall be, for said

term of Fifty-years, occupied by any

person not of the Caucasian race . . . ”

In at least 21 states, courts had upheld

covenants that excluded Negroes, Jews,

American Indians, Latin Americans,

Puerto Ricans and other minorities from

use of real estate. The Supreme Court

repeatedly declined applications to

decide on such covenants since its 1926

decision Corrigan v. Buckley.

During World War II over 20 suits

against covenants were filed in Los

Angeles and as many in Chicago. The

Federal Housing Administration had

drawn up a model form and kept public

housing projects separate-but-equal. The

1947 report of the President’s Commis

sion on Civil Rights indicated a more

favorable climate; one of its 40

recommendations was that the Justice

Department enter the legal fight against

the covenants being presented by Legal

Defense Fund cases from St. Louis and

Detroit in Shelley v. Kraemer.

The LDF submitted two “Brandeis

briefs” for Shelley.* Charles H. Houston

and Spottswood Robinson, III cited over

150 publications in their St. Louis case

brief. Thurgood Marshall, Marian Perry

and Loren Miller used data from

economist Robert C. Weaver (whose

book on “The Negro Ghetto” was soon

to be published), public health and

mental statistics for the Detroit brief.

Chief Justice Fred R. Vinson handed

down the unanimous opinion of the six

sitting Justices in Shelley v. Kraemer,

restrictive covenants are unenforceable.

In Barrows v. Jackson (1953) the

Supreme Court said that damages could

not be awarded for ignoring a restrictive

covenant, because that would result in

their enforcement.

Interstate TYavel: Buses, then

Trains

In Morgan v. Virginia (1946) the LDF

asked the Supreme Court to rule against

state imposed discrimination on

interstate buses. It did.

This began when a sheriff arrested

Irene Morgan for refusing to go to the

back of a Greyhound bus when a white

passenger got on. She had boarded at

Hayes store in rural Tidewater, Virginia,

bound for Baltimore. In stating the

Virginia travel segregation law could not

apply to interstate buses, the Court said

differing state laws— 18 states forbade

segregation, ten required it— were a

burden to carriers. On a long trip,

passengers could be made to change

seats back and forth in a game of

compulsory musical seats.

The ruling was worded for interstate

buses, but soon applied to trains in a

1949 Virginia state court test and the

*These amplified legal arguments with support of

medical and social science knowledge, in the

tradition begun by Louis D. Brandeis in his 1908

brief asking the Supreme Court to uphold a state’s

right to mandate a ten-hour day for women and

children working in laundries.

Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals decision

in 1951 that people going by train from

North Carolina to Pennsylvania could

not be forced to change where they sat.

Military Injustices: Courts

Martial

In World War II, the Fund intervened

in hundreds of cases when black service

men and women were victims of gross

injustice. After inept bungling by a new

commanding officer resulted in long

prison sentences for 68 black soldiers of

the 1320th Engineer General Service

Regiment; when 44 Negro Seabees,

trying to protect themselves against

white Marines invading their barracks

with machine guns blazing were court

martialed and sentenced to prison; when

50 black sailors at Port Chicago,

California were convicted of mutiny for

alleged refusal to load ammunition and

LDF investigation found they were tried

solely because they were Negroes, LDF

representatives brought reversals.

In the Korean War in 1950, after the

24th Infantry Regiment recaptured

Yechon in a 16-hour battle, 39 black

enlisted men were convicted and

sentenced for cowardice. Thurgood

Marshall talked with the imprisoned

men, with witnesses at their courts

martial, and examined records in Korea.

He found that, for the same offense,

black soldiers were consistently accused

of more serious charges. Trials were

rushed at assembly-line speed. In one

case, a black was sentenced to death; in

another, 15 years to life imprisonment;

fourteen received from ten to 50 years.

The few whites who were sentenced

received three and five years

imprisonment. The LDF prevailed upon

the Army to grant substantial reduction

of the blacks’ sentences.

All-White Juries

The Fund has defended hundreds of

victims of miscarried criminal justice.

When the Dallas county court convicted

Henry Allen Hill of rape, LDF attorneys

Leon R. Ransom and W. Robert Ming

showed that Dallas jury commissioners

had consistently selected only white

jurors. Chief Justice Harlan F. Stone’s

14

1942 opinion reversing Hill’s conviction

declared:

“ Equal protection of the laws is

something more than an abstract right.

It is a command which the state must

respect, the benefits of which every

person may demand.”

In Patton v. Mississippi (1947) the

Supreme Court struck down strategies

that excluded blacks from jury service.

Coerced Confessions

In the same tradition are scores of

cases that exposed extraction of incrim

inating statements under severe duress.

In Chambers v. Florida (1940),

requiring five appeals to the Florida

Supreme Court, police forced

confessions from four black defendants

by repeated beatings. Justice Hugo L.

Black wrote:

“ Due process of law ... commands

that no such practice as that disclosed

by this record shall send any accused

to his death.”

Five weeks later the Supreme Court

acted in White v. Texas to reverse the

Polk County sentence of Bob White for

rape. Police had pounded out the

“confession” in four nights of beatings.

After the alleged victim’s husband

walked into the courtroom during

White’s third trial, and shot him, the all-

white jury voted acquittal of the husband

after a trial that lasted two minutes.

Richard Kluger wrote “Simple Justice.” He

founded Charterhouse Books, was editor-in-chief

at Atheneum Publishers and executive editor of

Simon & Schuster. His most recently published

novel is “Star Witness.”

On December 9, 1952, in the waning days

of the presidency of Harry Tfuman, fifty-

six years after “equal but separate”

segregation was approved in Plessy v.

Ferguson, ninety years after the

Emancipation Proclamation, 163 years

after the ratification of the Constitution,

and 333 years after the first African slave

was known to have been brought to the

shores of the New World, the Supreme

Court convened to hear arguments on

whether the white people of the United

States might continue to treat the black

people as their subjects.

Another year and half would pass before

the Justices decided Brown v. Board of

Education of Topeka, the climax of a legal

crusade more than two decades in the

making. The decisive battle, won by a

small company of mostly black attorneys

under the flag of the NAACP Legal

Defense Fund, turned May 17, 1954, into a

milestone in American history. To many, in

retrospect, that day marked merely the

beginning of the struggle; in the midst of

slowed progress today, however, it is wrong

to minimize how large a triumph Brown

was and how far the American people have

come since.

Having proclaimed the equality of all

men in the preamble to the Declaration of

Independence, the nation’s founders then

elected, out of deference to the

slaveholding South, to omit that definition

of equalitarian democracy from the

Constitution. It took a terrible civil war to

correct that omission. But the Civil War

amendments, granting full-citizenship

rights to the freed slaves, were soon

drained of their original intention to

lift the black people to meaningful

membership in American society. The

Court itself would do much to assist in that

corrosive process, and Plessy was its most

brutal blow. Congress was no greater help.

In the grip of frankly racist Dixiecrats, it

passed no civil rights laws after the Court

eviscerated the one of 1875, and those that

remained on the books were largely

ignored by the states and unenforced by

federal administrations that ranged in

their attitudes from the high-tone bigotry

of the Wilson regime to the largely

ineffectual friendship of the TVuman

presidency.

The Negro, technically liberated from

bondage, was thus expected to shift on his

own. But he was no more welcomed in the

North and the West than he was embraced

in the South, which derived a perverse

solace for its own troubled fortunes by

continuing to bruise the bodies and souls of

black folk. Denied high skills or advanced

learning, they remained a superfluous and

lower order of American being— excess

baggage in the nation's rush to prosperity

and greatness. At most, he was there to

keep the American dream highly polished

and fetch cool libations for its white

beneficiaries. The law, as interpreted by

the Supreme Court, had pronounced it

permissible— indeed, it was normal and

expected— to degrade black America.

It was into that moral void that the

Court under Chief Justice Earl Warren

stepped twenty-five years ago this day.

Its opinion in Brown, for all its economy,

represented nothing short of a

reconstruction of American ideals. At a

moment when the country had just begun

to realize the magnitude of its world-wide

ideological contest with Communist

authoritarianism, the opinion of the Court

said that the United States still stood for

something more than material abundance,

still moved to an inner spirit, however

deeply it had been submerged by fear and

envy and mindless hate. The Court

restored to the American people a measure

of the humanity that had eroded in their

climb to global supremacy. The Court

said, without using the words, that that

ascent had been made over the backs of

black America— and that when you

stepped on a black man. he hurt. The time

had come to stop.

But ending the torment was not enough.

The nation had acquired a moral debt a

dozen generations in the making. New

15

statutes and insistent judicial rulings were

necessary— and met by resistance all along

the way. Affirmative action was denounced

as punitive to whites, who were reluctant

to acknowledge that blacks needed, and

deserved, a break if their climb to

economic equality and all that flowed

from it were not to consume many more

generations. Some have favored benign

neglect as a substitute for forthright social

policy in dealing with the nation’s worst

continuing human dilemma.

If black hopes and white fears may have

both been unreasonably high in the wake

of Brown, both races would do well to

remember that a single generation is not a

long time to complete a profound social

revolution. Patience, depending upon

circumstances, can be both a virtue and a

vice. What matters most is that the healing

process, once begun, never stop until the

noble destiny that animated it has been

won.

Richard Kluger

School Bell

From Herblock’s Here and Now (Simon & Shuster, 1955). Reprinted by permission.

16

The Brown Decision

On May 17, 1954 the United States made

racially segregated public schools illegal.

Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote the

Supreme Court’s unanimous decision in

Brown v. Board of Education.

Relying on the Equal Protection

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment

to the Constitution, the historic Brown

decision stated: “ in the field of public

education the doctrine of ‘separate but

equal’ has no place. Separate educational

facilities are inherently unequal.”

The last six words transformed

America’s standard of decency.

Inevitably it would soon affect access

to every other kind of public amenity

and service.

The Brown decision finally overthrew

the Plessy v. Ferguson decision of

the 1896 Supreme Court. That case,

seeking to uphold the right of a ‘colored’

passenger from Louisiana on an

interstate railway train, validated

“ separate but equal” laws. Despite a

succession of judgments that ordered

relief to Negro applicants, the Supreme

Court had for years avoided decision on

whether the Plessy formula was still

constitutionally valid.

Even though unanimous Supreme

Court decisions in June, 1950, ordered

previously segregated graduate schools at

the Universities of Texas and Oklahoma

to accord black students equal treatment,

Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson had

specifically refused to reject or affirm

the separate-but-equal principle.

In his classic history of the Brown

decision, “ Simple Justice,” Richard

Kluger tells how the Vinson court left

segregated education below graduate

professional schools still unadjudicated.

And how further legal attacks directed at

segregation risked permanently

cementing it in thousands of schools:

“ .. .For the first time, the Court had

asserted that separate-but-equal

education was not a mere slogan. The

equality had to be real or the separate

was constitutionally intolerable. That

was what Sweatt had accomplished.

And if separate facilities were not

provided, no individual or group

might suffer restrictions or

harassments within the biracial school.

That was what McLaurin did...

“All the Justices had really done was

to declare that the Court meant what it

said in Plessy more than half a century

earlier. Unless the Court could be

forced now to confront the legality of

segregation itself, NAACP lawyers

might have to spend the next half-

century arguing cases of unequal

educational facilities one by one.

Meanwhile, segregation would go on.

If the issue were forced, though, and

the Supreme Court chose not to uproot

Plessy, the cost of defeat might be

higher still. Segregation would be

reinforced as the law of the land... ”

Brown v. Board of Education cf

Topeka led the list of five school

desegregation appeals the Supreme

Court had scheduled for consideration in

its October 1952 term.

Two of the cases, Briggs v. Elliott

from Clarendon County, South Carolina,

and Davis v. County School Board of

Prince Edward County, Virginia, were

from the rural South. Black people there

were still at the margin of existence.

Black plaintiffs suffered severe reprisals

after filing suits.

In Topeka, Kansas, white and black

students attended school together in all

classes above the sixth grade. A court

order had integrated junior high schools

in 1941. Oliver Brown, who headed the

list of plaintiffs, was a welder working

for the Santa Fe Rail Road, belonged to

a union; he sued because his seven-year-

old daughter Linda had to travel farther

to get to her black primary school than if

she had been allowed to go to either of

two white elementary schools closer to

their home. As a skilled craftsman he

was economically secure.

In contrast, Harry Briggs, who headed

the list of black plaintiffs suing

Clarendon County, S.C., was fired after

14 years pumping gas at a filling station.

Community pressure forced the firing of

teachers, an Esso driver-salesman, two

motel chambermaids, and a garage

worker. A family was thrown off the

farm it rented. A veteran of Iwo Jirna

and Okinawa could not get a tractor

financed and the feed store told local

black farmers they had to pay up at once.

Sharecroppers were told not to bring

their dead to a funeral home run by a

plaintiff. The school board fired the

black principal from the school where he

had taught for ten years, discharged his

wife, two sisters, and a niece. The

church he served as pastor was stoned.

17

The Legal Defense Fund attorneys in the five

school segregation cases, Gebhart v. Belton,

(Delaware); Davis v. County School Board of

Prince Edward County, (Virginia); Briggs v.

Elliott, (South Carolina); Bolling v. Sharpe,

(Washington); Brown v. Board c f Education,

(Kansas). From left to right— Louis L. Redding

(Gebhart)-, Robert L. Carter (Brown)-, Oliver M.

Hill (Davis)-, Thurgood Marshall, Director-Counsel,

NAACP Legal Defense Fund; Spottswood W.

Robinson, III (Davis); Jack Greenberg (Gebhart);

James M. Nabrit, Jr. (Bolling); George E. C. Hayes

(Bolling).

18

His house was burned to the ground.

Gebhardt v. Belton was an appeal by

Delaware’s Attorney General after the

highest state court upheld complaints

filed by black plaintiffs in two cases.

Both had sought admission to suburban

schools in the towns where the black

families lived.

The Topeka and Delaware cases thrust

before the Supreme Court clear findings

that segregation penalized black

students.

In Kansas Judge Walter A. Huxman

had issued the federal District Court’s

unanimous opinion in July, 1962. It

found physical facilities and all other

measurable factors comparable in

Topeka’s 18 white and four black

elementary schools. There was “ no

willful, intentional or substantial

discrimination,” but whether segregation

itself constituted inequality was another

matter:

“ ... If segregation within a school as

in the McLaurin case is a denial of

due process, it is difficult to see why

segregation in separate schools would

not result in the same denial. Or if the

denial of the right to commingle with

the majority group in higher

institutions of learning as in the

Sweatt case and gain the educational

advantages resulting therefrom, is lack

of due process, it is difficult to see

why such denial would not result in

the same lack of due process if

practiced in the lower grades.”

Attached to Huxman’s opinion were nine

“Findings of Fact.” Finding VIII echoed

the social scientists who had testified

at the Topeka trial, especially the

sociologist Louisa Holt:

“ Segregation of white and colored

children in public schools has a

detrimental effect upon the colored

children. The impact is greater when it

has the sanction of the law; for the

policy of separating the races is

usually interpreted as denoting the

inferiority of the Negro group.

A sense of inferiority affects the

motivation of a child to learn.

Segregation with the sanction of law,

therefore, has a tendency to retard the

educational and mental development

of Negro children and to deprive them

of some of the benefits they would

receive in a racially integrated school

system.”

In Delaware Chancellor Collins Seitz

heard three days’ testimony in the State

Court of Chancery in October, 1951. One

witness was Frederic Wertham, the

psychiatrist who had examined eight

black and five white Delaware children.

Dr. Wertham reported, “Most of the

children we have examined interpret

segregation in one way and only one

way— and that is they interpret it as

punishment.” He said school segregation

is especially damaging because (1) it is

absolutely clearcut; (2) the state does it;

(3) it is discrimination of very long

duration, and (4) “ it is bound up with

the whole educational process. . . ”

Chancellor Seitz then saw for himself

the schools for white and colored

children. He found the differences

overwhelming. His April, 1952, decision

read:

“ Defendants say that the evidence

shows that the state may not be

‘ready’ for non-segregated education

and that a social problem cannot be

solved through legal force. Assuming

the validity of the contention without

for a minute conceding the sweeping

factual assumption, nevertheless, the

contention does not answer the fact

that the Negro’s mental health and

therefore his educational opportunities

are adversely affected by state-

imposed segregation in education. The

application of constitutional principles

is often distasteful to some citizens,

but that is one reason for

constitutional guarantees. The

principles override transitory

passions”

Chancellor Seitz then placed the duty to

decide on the highest Court:

“ ... the Supreme Court... has said

that a separate but equal test can be

applied, at least below the college

level. This court does not believe such

an implication is justified under the

evidence. Nevertheless, I do not

believe a lower court can reject a

principle of United States

Constitutional law which has been

adopted by fair implication by the

highest court of the land. I believe the

‘separate but equal’ doctrine should be

rejected, but I also believe its rejection

must come from that court.”

The Legal Defense Fund was the

attorney-of-record in the Kansas, South

Carolina, Virginia, and Delaware cases.

Bolling v. Sharpe, in which eleven black

students sued for admission to an all-

white District of Columbia junior high

school, had as its counsel James M.

Nabrit, Jr.— Professor of law and later

president of Howard University— who

was “of counsel” as co-author of the

briefs in the four LDF cases and for

many years has been an LDF board

member.

The Bolling argument was different.

Even though the all-white John Philip

Sousa Junior High School the plaintiffs

sought to enter was brand-new and

beautifully equipped, and the all-black

Shaw Junior High they attended had a

science laboratory consisting of one

Bunsen burner and a bowl of goldfish,

Nabrit made no claim that Shaw was

unequal to the Sousa school. He based

the request for relief wholly on the fact

of segregation itself.

Professor Nabrit argued that the

District of Columbia government had the

obligation to prove there was a

reasonable basis or public purpose in

racially restricting school admissions. If

acts of Congress were held to compel the

District to maintain separate schools,

these were bills of attainder, legislative

acts “ which inflict punishment without a

judicial trial.”

He also cited Judge Henry Edgerton’s

1950 U.S. Court of Appeals dissent in

Carr v. Corning, which Charles H.

Houston had argued soon before his

death. Edgerton said:

“ ... School segregation is humiliating

to Negroes. Courts have sometimes

denied that segregation implies

inferiority. This amounts to saying, in

the face of the obvious fact of racial

prejudice, that the whites who impose

segregation do not consider Negroes

inferior. Not only words but acts mean

what they are intended and understood

to mean ... Segregation of a depressed

minority means that it is not thought

fit to associate with others. Both

whites and Negroes know that

enforced racial segregation in schools

exists because people who impose it

19

consider colored children unfit to

associate with white children.

“Appellees [the D.C. school officials]

say that Congress requires them to

maintain segregation ... I think the

question irrelevant, since legislation

cannot affect appellants’ constitutional

rights.

” ... Congress may have been right in

thinking Negroes were not entitled to

unsegregated schooling when the

Fourteenth Amendment was adopted.

But the question what schooling was

good enough to meet their

constitutional rights 160 or 180 years

ago is different from the question what

schooling meets their rights now.”

James M. Nabrit, Jr. ended his oral

argument before the Supreme Court with

two sentences: “ We submit that in this

case, in the heart of the nation’s capital,

in the capital of democracy, there is no

place for a segregated school system.

The country cannot afford it, and the

Constitution does not permit it. and the

statutes of Congress do not authorize it.”

On June 8, 1953 the Supreme Court

ordered the five segregation cases to be

reargued on October 12th. It asked the

parties to the suits five questions. These

called for evidence showing whether or

not the framers and ratifiers of the

Fourteenth Amendment understood that

it would abolish public school

segregation, or authorize future

Congresses or courts to do so. If the

Court were to decide against segregated

public schools, what orders should it

issue? It also invited the Attorney

General of the U.S. to submit a new

brief.

The summer of 1953 saw more intense

historical research into Congressional

and state legislative debates in the period

soon after the Civil War than had been

pursued within memory.

John W. Davis, the eminent attorney

who had argued more cases before the

Supreme Court than any man living or

dead and was counsel for South

Carolina, assigned half a dozen crack

law students working as summer trainees

for his Wall Street law firm of Davis,

Polk & Wardwell to study the

Congressional debates in the New York

Public and Congressional Libraries. The

leading Richmond law firm of Hunton,

Williams, Anderson, Gay & Moore,

retained by Prince Edward County,

studied the process whereby states had

ratified the Fourteenth amendment.

The Legal Defense Fund divided

research into sections on law, history,

and sociology. Dr. John A. Davis,

associate professor of government at City

College of New York, directed non-legal

studies. By the time the LDF filed its

reargument brief the task force would

number more than 200 scholars.*

Richard Kluger has written that more

top-grade brainpower flowed into the

effort early that summer "when, without

being asked, William Coleman, the

tough-minded black Philadelphia lawyer,

’phoned [Thurgood] Marshall and asked

to coordinate the research in the various

states— a task that in most cases had to

be done in the state capital, where

archives and official accounts of

legislative and other governmental

proceedings were generally stored.

“From his experiences as an editor of

the Harvard Law Review, a clerk to

Felix Frankfurter, and an associate at

the Paul, Weiss firm in New York,

Coleman had a growing network of

acquaintances in the profession who

shared with him a notably high-caliber

intellect— young lawyers and legal

scholars who had been, in effect, the

law-school All Americans of their

day. ‘Sitting here in my office one

*Dr Alfred H. Kelly, professor of constitutional

history at Wayne State University, Law Librarian

Howard Jay Graham of the Los Angeles Bar

Association, and President Horace M. Bond of

Lincoln University prepared basic monographs on

the adoption and ratification of the 14th

amendment. Professors C. Vann Woodward of

Johns Hopkins and John Hope Franklin of Howard

University wrote monographs on the history of

reconstruction in the South and the results of

segregation. Dr. Kenneth B. Clark, associate

professor of psychology at the City College of

New York, headed the team that explored methods

used to effect desegregation in varied situations.

Others the December 15. 1953 brief credited were

Professor Howard K. Beale. Dr. Charles S.

Johnson. Dr. Buell Gallagher, Dr. Charles Wesley.

Professor Robert K. Carr, Professor John Frank,

Professor Paul Freund, Dean George M. Johnson.

Professor Walter Gellhorn, Dr. Charles S.

Thompson, Professor David Haber, Dr. Milton

Konvitz, Professor Robert Cushman, Ulysses S.