Desegregation Now, Legal Defense Attorneys Urge

Press Release

November 15, 1954

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Loose Pages. Desegregation Now, Legal Defense Attorneys Urge, 1954. e7ddb7f6-bb92-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1a7a2a2c-41f7-47a2-9acf-7b243f2412c3/desegregation-now-legal-defense-attorneys-urge. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

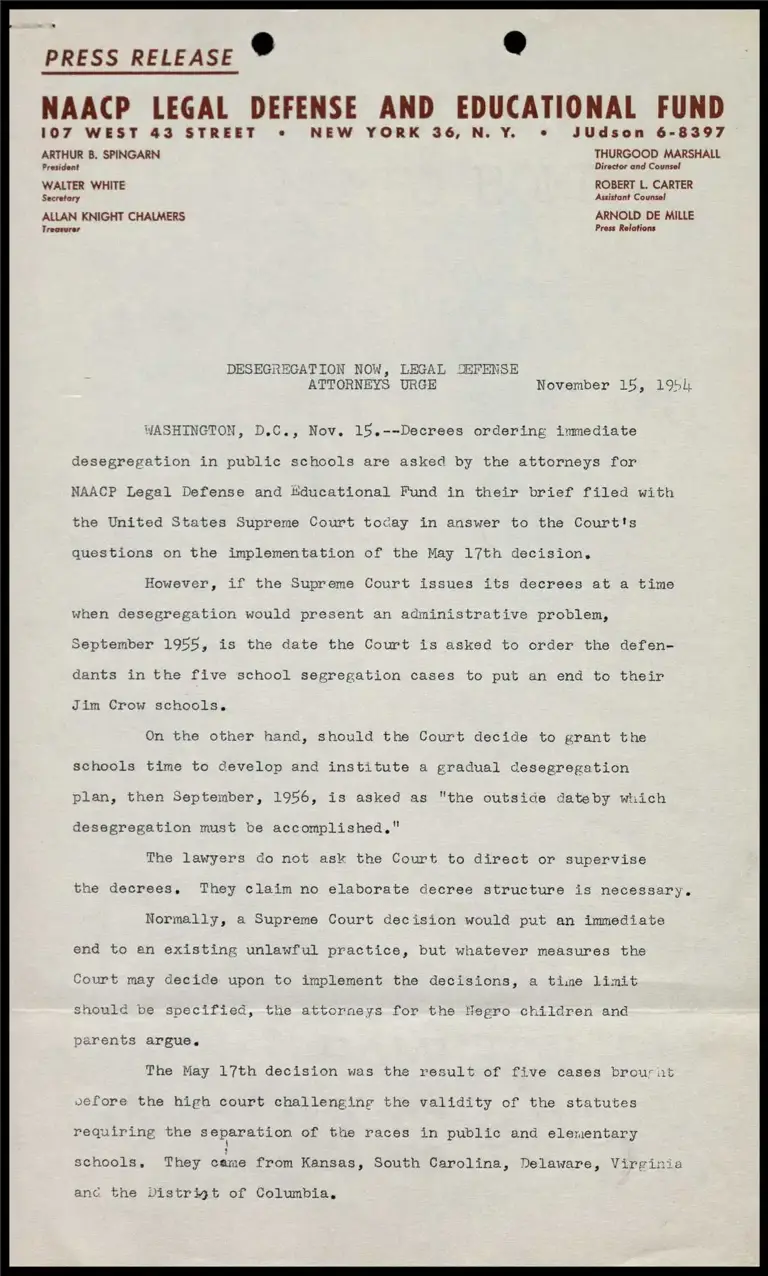

PRESS RELEASE e

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND

107 WEST 43 STREET + NEW YORK 36, N. Y. JUdson 6-8397

ARTHUR B. SPINGARN THURGOOD MARSHALL

President Director and Counsel

WALTER WHITE ROBERT L. CARTER

Secretary Assistant Counsol

ALLAN KNIGHT CHALMERS ARNOLD DE MILLE

Treosurer Press Relations

DESEGREGATION NOW, LEGAL SRFENSE

ATTORNEYS URGE November 15, 195h

WASHINGTON, D.C., Nov. 15.--Decrees ordering immediate

desegregation in public schools are asked by the attorneys for

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund in their brief filed with

the United States Supreme Court today in answer to the Court's

questions on the implementation of the May 17th decision,

However, if the Supreme Court issues its decrees at a time

when desegregation would present an administrative problem,

September 1955, is the date the Court is asked to order the defen-

dants in the five school segregation cases to put an end to their

Jim Crow schools.

On the other hand, should the Court decide to grant the

schools time to develop and institute a gradual desegregation

plan, then September, 1956, is asked as "the outside dateby which

desegregation must be accomplished."

The lawyers do not ask the Court to direct or supervise

the decrees, They claim no elaborate decree structure is necessary,

Normally, a Supreme Court decision would put an immediate

end to an existing unlawful practice, but whatever measures the

Court may decide upon to implement the decisions, a time limit

should be specified, the attorneys for the Negro children and

parents argue.

The May 17th decision was the result of five cases brourit

oefore the high court challenging the validity of the statutes

requiring the separation of the races in public and elenentary

schools, They came from Kansas, South Carolina, Delaware, Virginia

and the Distrigt of Columbia,

eo.

In handing down the unanimous opinion declaring that the

"separate but equal" doctrine has no place in education and that

segregated schools established by statutory requirements violates

the Federal Constitution, the Supreme Court ordered the five cases

restored to the docket for further argument on questions ) and 5

of the five original questions posed in the reargument of the

cases in December, 1953.

All parties involved were asked to present their views on

whether the Court should direct immediate or gradual desegregation,

and when and how it should be done.

Should the Court decide that gradual adjustment from a

segregated to a non-segregated system is necessary, the attorneys

for the NAACP Legal Defense ask that the integration program not

be allowed to drag on indefinitely, They point out that, "Each

day the relief is postponed is to the appellants a day of serious

and irreparable injury; for this Court has announced that segrega-

tion of Negroes in public schools generates a feeling of inferiority

as to their status in the community that may affect their hearts

and minds in a way unlikely ever to be undone,"

There is no reason to believe that the process of transi-

tion would be more effective if allowed to lapse into years, they

say.

The attorneys agree that delays in some communities might

be necessary because of administrative difficulties, but they do

believe that the Court would not place the request of the defendants

to prolong and drag out a make-believe process of desegregation

above the need for immediate action to give relief to the many

thousands of Negro children now being denied a fair and adequate

education.

"Gradual @ proaches" to desegregation without a time limit

could well delay the successful conclusion for five or ten years,

the lawyers maintain. Such delay could result in additional

manipulation on the part of those bent on circumventing the law and

the decrees.

Negro children should be given an opportunity to enjoy the

constitutional rights which the Court held on May 17th they are

ay ® *

entitled, the lawyers continue. The decrees should contain no

provision for extension of time. To grant more time is merely an

invitation to put off a desegregation program,

Moreover, the decrees should also provide that in the

event the school authorities for any reason at all fail to comply

with the time limitation, the Negro children should immediately

be admitted to the Schools where they applied for enrollment and

were refused, the attorneys maintain.

NAACP Legal Defense lawyers ask that any decree granting

time for gradual desegregation be so framed that no state main-=

taining segregated school systems will be encouraged to sit back,

do nothing and merely wait for court suits on the assumption that

the same period of time will be granted to them after the suit

hits the court.

The lawyers also say that if the Court should decide to

grant gradual adjustment, it should not formulate detailed decrees

but "should send these cases back to the courts where they origi-

nated" with "specific instructions to complete desegregation" by

a certain date,

They urge the Court to issue specific instructions that

any decree entered by the district courts should specify "(1)

that the process of desegregation be commenced immediately, (2)

that appellees be required to file periodic reports to the courts

of first instance, and (3) an outer time limit by which desegrega-

tion must be completed.”

In this argument, the lawyers say that "whatever the reason

for gradualism, there is no reason to beliéve that the process of

transition would be more effective if further extended. . .

Therefore, we submit that if the Court decides to grant further

time, then all decrees should specify September, 1956 as the out-

side date by which desegregation must be accomplished."

NAACP Legal Defense attorneys are Thurgood Marshall, NAACP

special counsel and director-counsel of NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc., New York, and Harold R. Boulware,

Columbia, S.C., (the South Carolina case); Robert L, Carter, NAACP

assistant special counsel and assistant counsel of Legal Defense,

New York, and Charles Scott, Topeka, Kansas (the Topeka case);

Spottswood Robinson, III, Southeast regional counsel of Legal

alin

Defenses and Oliver W, Hill, member of the Legal Defense National

Legal Committee, both of Richmond, Va, (the Virginia case); Jack

Greenberg, Legal Defense assistant counsel, New York, and Louis

L. Redding, member Legal Defense National Legal Committee,

Wilmington, Del, (Delaware case); and James M, Nabrit, professor

of Law at Howard University and member of Legal Defense National

Legal Committee, and George E, C, Hayes, Washington, D, C. (the

D.C. case),

The questions posed by the Supreme Court are:

. Assuming it is decided that segregation in public

schools violates the Fourteenth Amendment,

(a) would a decree necessarily follow providing

that, within the limits set by normal geo-

graphic school districting, Negro children

should forthwith be admitted to schools of

their choice, or

(b) may this Court, in the exercise of its equity

powers, permit an effective gradual adjustment

to be brought about from existing segregated

systems to a system not based on color dis-

tinctions?

Se On the assumption on which questions l(a) and (b)

are based, and assuming further that this Court

will exercise its equity powers to the end described

in question k(b),

(a) should this Court formulate detailed decrees

in these cases;

(bo) if so, what specific issues should the decrees

reach;

(ec) should this Court appoint a special master to

hear evidence with a view to recommending

specific terms for such decrees;

(d) should this Court remand to the courts of

first instance with directions to frame

decrees in these cases, and if so, what

general directions should the decrees of this

Court include and what procedures should the

courts of first instance follow in arriving

at the specific terms of more detailed decrees?

The Attorney General of the United States was invited to

participate. The Attorneys general of the states requiring or per-

mitting segregation in public education were also invited to appear

as amici curiae (friends of the court).

30m