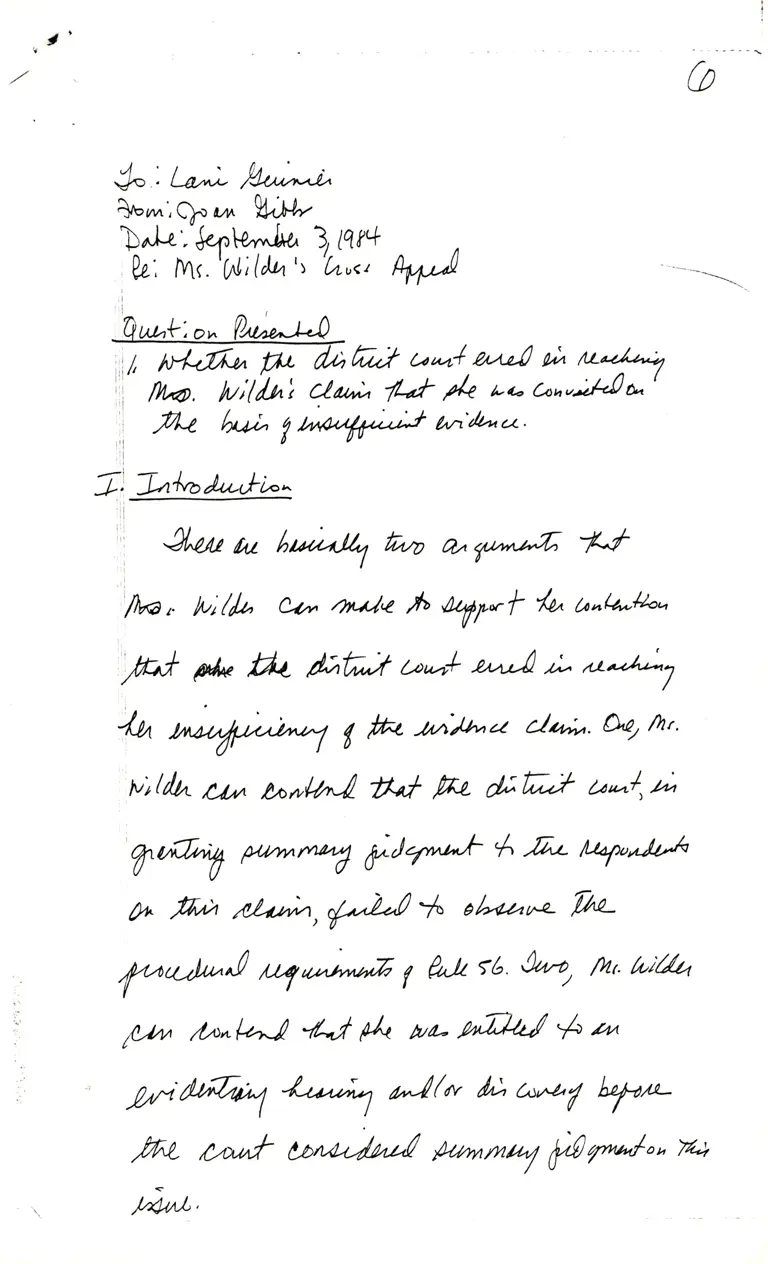

Memorandum from Gibbs to Guinier

Working File

September 3, 1984

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bozeman & Wilder Working Files. Memorandum from Gibbs to Guinier, 1984. bd3d0e4f-ef92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1aab205d-8ba6-43d2-a6a4-9c3f443436a1/memorandum-from-gibbs-to-guinier. Accessed February 09, 2026.

Copied!

'fYry/f

,o.7u.*/N Lrt,urW W t<r/ M

-r4r7 /*v 7V N/ru L'""".r* l"ry"fr/.''"'f

vrzf ruzr4 Yryfvluc4/ '*r/

Wrq'q/ '% ?5 7fV I Z"^^^r"'?'bn' fryr'r'/

% dftnta€ yLrcfr(r@ W +0

,7,-r7rch7y ry Y Nf,!

7't-n-ruf, 4 lW

'rry /arg 'ryr/" z*r7.W 4

L--,-,7.-nyry1nr7ruW W W fq

n*xfiu7 ry 4^/b { vrua q qf/!,( ''4

% y"-nr.r9.U ry

l,r?f,r-a*r?tu? vT4tr

:

@tfi,

'n't7F.*?fu[ ry ryd

,,

,w6*.nqnn Y n ruP yFl,,4 '@'1,(/

i,l

/",-rnry yo 7wfq ru? rd ryW /t':

I

r )n ??, t , vry) I ?v1,

' ltal '.q

hlbl'L Ytq,",n\*4^'31r(

ffi mc(3',trq&

ryy7 '.7

f,'*r'^*rA 0r^L*'0

rul'q vryl

tM

/.^l

ry

YI

o)

,f

@

i U* D&t*;f U,A Lr."o,L r^ obuv<- W

, ^YlA^lL Arwt *t*tr"vt Wu^r4,q^ *r 4 ?rrL SL( " Jt!^ ho^C,ao l;^'^if"l,f"4 "ft4aist fi'ts,

i.

t^)r),i" A^,tl'rl^r"l& 4" CL tu;/r-,oe- (ta)

,I

', ?)r),L ll q ttt, P-^L- *lo,rrnn;^q ltilNl-0t

:l

ti

',Arg,to eor* tJfi*" /uL; 22{Lt -luv;lu \4n

,l

li

,,t'*fo xilhal e,,"ll

b Lr,;X fu,ru)u,,e-rto TI,o

tigr*t^+ fr,qf a^l ^r^+ ,r)c.*,..al"J c.-*an

y rvJ,u, rmy h,L afl,M,,wlh

a4^k fhhL .*lt, o 0*t

aqY^ Y,r.l'rh

g rt,o W^l r,y'*o

t{^} W,o C"^+ R* WWitL

WF #ur! lMl,bhrpu.pq

h U^1, {br,^rl;l^

Touq/r,r

fa @ r' arr,r)!

t lyn o+;on( l-,, lczymn'r^f i/r?.*/* flit '# ,.

fril-+ron.) L{31 O,S, 101 |u-(lC{lJ). Ur*h t-

Ur/rA/A^/^tf wl,'$t^rtu +b W or 4 l,'tttamt/Lf

6rJM

^'ld,h-

btrywt uAt. Wet 'lt*-

affi,/Lr^9 W^. tr^*l*r* ( Pr").{6. kz- 0,,

V,

b

r{z F 9,ff. Tal C/t' 6, -fo^'o'

/f le ) 9k/'drr(4 Ezl 7/ bil 4,- //7t)'

/ f ? ? € Jyr. //f f/r. D. d. tftt).

;, /4 b-+, V* fq ounru%PN

l

'Unl^t, zu {br rnA} il* Uut *, /.t,atut- frrt

,,'t1/\ 0.il)1, ,l n htd/ d- il^L I^J.+z*,{;"X -irrrr)*/^/,

,1,'f , U,,w,^*fr f/f,^h* a^r|, zu f6 /' tlz*'

lq

Qfr"@. Ca /.7. h/y'r. L)aJ , b?? FZto?L

Ltr*L h;, /0O),' ilcDo,ruU frkh-, bbu t;)/

' arlL (rt/ a),/lr2)r' fu

y"t,, 6ot l7 U tzt [sfl o). 07il- @

Prrl, ftLt p^,fu Zr// B,

t* *tto, phU k zt wJ "* U/.f

/04,,4*fu^fu,fu.>il

,&* t/ic,oe

y"Uf-fry 4gtu,fu

no,,? p.lF hFl"try d/,t4/lr^E

[11,. til;tlh /uL, Pr;,1r0

4,rr$*'t^To

/

\Cr [/4 uff"@ h k '/*ril h1 -/r^-

rl

.ll

,11..

".lr1^)rfun Ov AouO^/ ocaoqattu tn/*rnlrl >a ,E^.

,l

ri

p*4 tlrrek ar/- ry ry '4/2wt*%

l'i

'*'l

;'l,l

I

,'a/M

{-

,

tn

At^ -/h rlur{)a t/a/"; /,-l rt./

//i4r,ZA A,1 C** /o.tt*u* erJ?.,,/"r/ -

&r, W ;,ru ai/lnu au"t a"-?/

5 Jl. b*t+i 1da 6 Dt"c/".d/, )/ /11? f - /,

Pnk *' i frt "'wm {ffi {#,,ff ,@/+ /t,o [e/ /r1*"' E /"r-",

,,qrt {"r4 &h nr. D/bn| /toofbn f, *tunt*1

Nfr*, tula ?nr. b;//h ttf,,,,a! Y/,-/

4'h qrlrH u1^uA ?^-pt ,fr* u,* /-L*-u*

Lwn* 4 e/ /^,tgvlrlft !.rl pt)

wr,fldGl l**^,ri'l; rr/; j4

ry V7 "%l*{ 4 @

ffiirt,"t "'xn/ r"* '^'"'"'/L;g

,,'r.i /a -n t lt t4./t/TT7n/ ry,xy - ,;; k'ru?r' |%rut -,-ri"l

? q?u/ f1{'T ,,JINQ EflL

4f-{ t^e rug ry /:--7r1: 4 ,*U

fittr 'z 7*,4 q Nn! L^-@ t( 'lJew

l,q/ru'ft11r w 4 ry r 47or"cu/l/

,T w "til!"( W

1.ry,l,7 lqre?" b* q- @n,,

-,M/ { *'rztrr ztol*+/>(7 7 ,A) o'Y f?1.

L,-*r,sr*/ ,o-rymrl , tr/ ry-I?-t/ iry*'"/ o/

rN +*-,r/rr! P*-r*tr2d wfr.T

Wry%ru f4mv77l

ry.w7% { L*'"4(-** T

tuo

a

0//da/ h, fr". @/-l P*,t /h.,- lr;/fu tur'

,

(.r,*,t 9.p, Uu,^/

v L/ aaT"*'1 ,

. (-

/u-hJ.^1)b. Lu.-f

,tnu^+ Orfuas W pl,tnvrtnoL1 t^/1** C ou

,trt tD,r,"J

W tr4 a)u*u fq LX ""o/ k/-

% rrnlt/ o-/tfark >,4t;,2 u ou *fu-/-(r',*f7 rt

%.-r;-^/ Lr/ &r/. fL. &/ o,7,

r L*r,rilr-, /.

t0> t f, 2n 3fi ( s14 a), /?ro)) [1nr-l,uttos,/- ,

-/l4b^ru/ t t; E Ll -2t a Gru L^. /?%)r'

bt'U l-,

gtwt^-l NNTI,Anq*

ill

.l 0A lht, b,'//h) l/-,; "fr./ -/" 4rl aa44 co*:u4o

i

il

:,i t

:li A^ trL ln4; X h il^lt ^*,# ttai,,o*,u /.,/J /"

,';

ii . ,

,fi2atal ^tr4 hAt;/_ t*/ @ %,,;d, 0

,,'w dLb),

ll

iii

', J l^,r*o n- n'u",,t'l't'5

'a*L q/tiffi, Atu^t Pd.r-

6

n>l

s|(

t,i

; LlL4/h,A^

bu'+i

lLq ktr (i,

f 2.il qb(fn

/?)).

A,rJ

'r boY

nfr) ) /o'l/a,.r, rto,f ,\- ,

a\, m0/' l/u'.fri !-,flr,,*

)hrttl* g* h,* l/,

/ s7 3 F2/ y/;

e4 t/. /o I lc

/l-,"xr*, r,( h,-! 4 oilr-

t

,atat- ru44Alt/aq FI

a /;L.r

arb 4 1ttw,rnA /.1^ a L,/4*

I

p,//)"" fu, nL /o,,,ntl , k//u. 4),/,--'rqt? +.

l,;

brf* fflrfr-^ wL d; "pr^Ll # P'1u 94

V.rn-*l 0 4, 1tt"t,^rlt, l'J, ?d fr "f'"-

€t.1. ,!L,*^)1 lrrG; adrl 0"e. 2* l-

,A* /r)lwrarJ I -/; TrTh;, rL /,fr/l*-,t-

//,/L ,rti/* ?** o^Di M./ a.^ ?f*@ rt

Ae /r*,,1 0 h ry -h f,frfr,"; C,-U

/rt- dfirilrr*J , 0u @, tr"'a**lZu

6

0"*7 E-alrl ,U- /r"f udfu,ic / n-t{;- /"

'fr, &*w,mt.q d;"!"ML u.Jr" U- fa o''9 Ul

l:t.

',|1fr^.1 d".A^*t aJ AX uz! b /)*1

:rl

ii

& flfrlL'hi pfub- dfu"4 f""+4;

nol /*ftnrl 6( I n tL,"!A L1 t*c,,^-.9'

t.i,,l-aA t' t / -^ l I lt e)-

fu /Lt7,*,Q"-1, ,n/, {r,"d f**,/7 h.r/

/ Ftu+ trtht,/,,*- ol'hu.",J { ^^4 h.u7*"'/

v w,l o "htr //}J/*t,ri,fu)c'//

//,1/r,^t1497 /-7 A l)fr"nfi 4U a^ "E-

!4J //tr. b;\eb ?4 //t*.;,..

ltut4@/yh{A.ry,

?uil'J

^

U,/!-

fur W uj\ W'1 4 A-r7*ila/c//1t,/P^

+, (2il4 Tv,- q-/f",rJ, f,?. ful'lry,

o

,frt /tuf D,L/,2*k b;// f*/,r4 ,*'ry/" rutl*4

eM /;l nuol ,f,n,tol* a d;,',*;4r/ PtL,t,]* fuJ'4'?6)'

',1, fh, [,",//(", f^4 Pol,onlt d// aA- f ry

I

l,bnl./*l/ ,/"1 E* oF/u.'/fi) /^ rya'^Jr^l *,

I

lifre d^fr^* Lrr,#, e,ltn { Du/r/"r,J/ /qrg,#

?4/"#% dil^tu/ "X-*,*TL*

oL{'9

,l'i' ' t t /4" if W/ 6 tll ort'ltru*? otgn\ *pyl.l^Wl-*a u""/e-i/h/4.r, b":

I

Yk Lufr^^bt t/ /4 dl g,u,*Ol t'

-fu" Ntb. S?-p+fArM'P'47u,'u J" Ditr'n

l

fuut'' \cfu^ q, Tl*z.,U E Ff r//.0

,, J4" b*/t lr^fr.t'-

^

W., L,.,.rn*,

C0/^ k /*,ki"r/rl b */ry f'h/ {-L-"u,.

,r* L)4* A,r/* /tcu-% 2u,,/ k

p/h44nL% da'/ fr,,^/ ,f;'/ fia*, 0* tul

6

fr@.1-or!4r,nr th, fr-f

Ur^,b, 0^k {6k)7 h+4 ttu rabJ

6/z !""ZtlrJ k,o/|cz fi',/ TrL

0frf4 /u,/-l *o. ^

W ?t) d;/'""'/-f

ruaa^il hL

tfuk[ (b ,t tno*,b,

Aqr runnag

h*l /r-^d utu/ a'a- evPr'fu;h-r\\ v

Wttrfr,rfr!fuffi

afu Wu-' run r^*i nnt'l-n. ,u i

lrr+ e.!,-* fr^I /L-a 4-0r/ A,lotu

/" frv fuorr*Ak! &1r*""t*/o?a'n

'|1,k- ,/ , b?) f -zl of /o?('7U

t:i

rt:l

'ru,^nl h &Z *fu c,-a.!a/troa-y'ak-'

"i

Uat/ i ,rtJrfifrrl u,-'1] adl4 ?-^fu1vq.4_r/

,l

luryumuf /-/7-tu/@ ur.at-0 lrtq *,

,ru V*^.-.l IL-t "be a),^arre /4 Ll eof' ,Y,*"1,/-l

hzh,lrl-/.r1r/*t< untrz- ar-! a Lrr4 d-l *', M

I

/0/4/- ,rc" afu,q,,4t n *"/ /r4/. /"f"/J

% /r/d/oK 4/t, /Wu'L)& r 6/7 n/*

/D34- lols.

o

-1L a.at {r/J q frL .b,*-/ u)k.

:Wy,O t^ lil! h,t,

ri

l,'iA ,t F,ad 27? Gil a

,il

olr} u.,<h ,fr,4 4 i>;d;--,tru,

r!l

,bnl,,*u* on 3ar*7 J1 l. /*r- 6^f-^,u*

:,it:Ou

fr,,L Wt n^ut,ou '/. U/4,,/)4,JLNf

i

t/r, t/rz6*,1il Fe f l"^Xtt * ru/n',L/ L /ncw /th-L/

I

,'tlflio^dz /- dq/*la44' ,Lrot; aJ on W..-P^

'ol? W fW W't/*rt- il'o,onzt, &-f,"'-

.Pt'n^t futrfu W W d- h-rqi"'X7"'/-

4 P,U yt4,r+ -oh , t/*- 4 ru.a/z fii.ar,?-r--..

0

,,,,,P//"^//- ,L ,fr^L f/%', fu/,tr,/t*t" i ryf"'+

/untio* 4 /r-r*;a,O^ fhL ry 6rf*{fr"

ar-U,rrr1 &1t FL P ffi14 #4

@

.( ru&otu( Ln, ru/-, ,Zaf/71/t?\2.oLb

(

'

' '^"1'L'

,,tt

k/tr0t/{- /

N+N

4^A trL fbrb^+ /^l L'Qr" a"'^-t,t''^"9

dr, firr";r^! T,l*- (')hbq4\ b*1/;/ ?

)/ ,t' zvo.

qryWW M,"*{*l [,*

i or"l*. i7* u*,/ % fts

'd,)ur*d,^'^

t P^e lffif ' c//; llA A/

/rrr^ ,*ot Ar/^ //-o?;U Y^.fu o'/ 4

fu arotn,q 1* /,,L 2 t /z(t)G) n^frno: -l (

"y') (--.> nt+-l*4 ,;d. A nurt.,ort /A'/ **U /^'lp

Y1* a(,/u,r4 yJ nof)ct- ryilu"t*E fr A-/L

//L(6) 0,,-r! f6 d /h/,t4/- lz a// lr,,J h. " /

lifot)+b,. Sdn@, fu'

0u a,*" ll!ilfr\ W^* rlu^Jl*A

/ bts € 2/,/ e tb.

@

J,t yLq t#t- Lt:,.*l ,QrLl/ -l*l il^+ )-"u^"

,p*i tlrA ,W{lu- lau//*e fr* L-,a /,A//*-}i,n-

,l

rl

fu -k Lr!'/n/ ttoillat o''a"'/t [^' Na-4"

I

.,i

1l

,i;Olr',ut {^^ e.q' fuf ,, W*- d% I ,t*

;li

),Atl fri h-u lo,t@ bs E:/

.,|

.lr,l

fu di f*f b|-,{ fr-4, / b"^l' b-/*,,u,t,

lii

i!

,/ Llo

/e0

l.l yhdfl

/'A h

tto.f 4M,A*-tW Pry

'

i.

,iM ! -/; tryr","",e b,^t rafi+t

nruo,tLdJ- ,b4 f q, d't+ al*y,rA Y'of t--

l/

i

O*il,O,?- olyhr*-67 * lo-r^f il @

r,^ilrl hr+ tU ogwtrr^-oft

J il,tlil^^o/ rrilhrJ'

O^/ A fl/r"ra,/- 4r/r,,4 Vl- n" /414

4 orr,o,%d4/,) ),,J/ c^// tt 1/L D//

h^*/.4/,e',r/* pk;74i

{* ah,rz4 Pr^/r)rr} "t/l 5

-/,,r ^ f *L: :fu . raf L/a,tu-

( rur,4^J,h il**, Aa^r.,!,tu4

on llrr+i 'D a*/rr:4,t !" u

'A/Auu, ao ^A^/ rt* /r,&h" a;//

fu a,rhA 2,*4

d//fr,,l a^/ hl af;""^/./M u

,i / r€ )/t J/o'

.'. C{

i,i

i,,

iii !t*lvr, o-n,e- afirl 4 fr* c,*t t;W'

l'i

l,;, tr*u k*lo?r. kLk Wl*1",r:0, '-/n'c' bs€ul

lt.

1,,

',til g?? tStl, (;, /qfo) 0,,-

lt,

tll

Itt

It

lil

lil

Ilt

il!

iil

tit

tir

i';

lri

Itr

lil

lri

ii;

l

li:

lil

Ir,

i,

irl

lr,

t,:

i'r

itilll

lil

li;

i.'

:tl

tll

t'l

ir

lti

.,1

Itl

il'

iii

i,l

lt.li

ii

ii.

6

' [Vt, . r/;//h .fu, /t-,Jl c,*L-A 7/-+ .fr^L

:

,i

'1ltlr'< re*W n^Ta. bJ d44 WW

,.1

I'iJe * /*r^A W /a,^"< L4b Wr-l d lLou

,ti

i:rlUU* u)t- pj,^,,.L0 tt afifrl /*, /h at,t a*0

til

'W rb* MGc,* /n*r{l oc-.!ta ,ffuru%

tii

ilPqr,.* 1^ X,^- lt /onlnL n*l hz Yr.-l'0

'il-ar.'llo^g 4L uaz ,u.*.r-',L-l {, W0 4A Do qfq

/. kt k '/rrr! aa' %, cL",;' fr b'**-

',1

40* f A** ( tr'w ai& ,w/tu /,11/4

:

t^arl"tAryL /t/*,il/

,,J/r A' 64h frr; ltl 14^2'L

w &-*'rn'/r,/W/ alltu

@

l

',,it t oy^ ,-'4 o'fu4t prn-l d- P *1"-/+

i-

'p*trr-l o*C {<,lrr'",,r^; Arrnlcd.la %

I

7rt*or-a 1 t, "/1r4u/ ry, o^ p{,+a", ;nb^/''-*'ot-

il

'r,; /r,r'zth rh nl-* rrhJ bru;"^o." uh[p ^'t,',*, @

li,.

i, 0

W/,r! h*fhr-t ru/.f1 4 ry ron"6/4hq.

fu o0q4 ,aLr^^f lrv,u d/*l fi 7* /T-/a'/rr

i,-e

,;'/r/- P Tth4 s/4il/,n% t"/N *lw.

'; Atu/ W L *** /- TLaL noh.^, )An 'Ltu

i

"14

{

i'

'

a

4 ,r,tu

orda

Y/* E-&, A-4 a4ratu4ffiru?e,

W d;fuku,A Wr,,^f-l -sua*,^a N./"-^f-U

ill La- ,r,f ar,-l L dt;* f-il

o,*WO W^l W,L tbL,4 W I^f.r-

L

U hruLr,/ c/;

CL&a^l W Pq

orlt^ ;^la^,%,e e

//^^4b*! hel dtgza-fA fr

I

A*i e""L (L 4*lI

I^lLl&r*u- DfA

M- a,yyyulr-; l"*l rylr! c,o4 /' uf /wa' n,ff

W tts kt-az. f ,rD' /"r

r-^ fn,-lo--/ fut;*t- glrZ, )t,

1x1,0^L- q* ilt-* a,-/ "Pr ,Lttryr^rl f/v'"".^C

dffi.i* tarnlJ

'fL-/ -At /*uJr^r-

:lttt /afi

+ fu atyUefi ov'. ilo 1 %/,J'/ *Uie

u u/1t^L

Pr,1xu LLLt imtr- b,'la- 4/"^J, il-d*nts ail D,4- tr

, /n-r(! lrrL Ttr3?10? + 'y''

ba

tW % 6-77ry U)a,b ml#-

I

-rynVs,*,"u| W? fVrVO @ %

,f@

"TC

,VT"Z

/*'ruf17xz frV

(ffiru

// fiy-*l ?*t-*ro 4

qo,t+wv

V@fu W/r* lqqt {,.-ryp v

/fwd l*n? 4,,'uif^r.*tw{TP -r$

K, :tutnnn) z^nqfu Tyl $ Br"o.)?O

vrJ Wfgrt 1td ,fr'lrh t +wJ lG

I

ry ?V+tt1e'A 'f(f

.,

e4, f* d

(-*,-"@ ,"f

?r/-rry+v 0-'l 71dv dqw

alw

-0

%

,rfyryf"p

w/fi rya

'ta ffi,a ril.

'@/-,qM

WA 'obt fr KJ

P

?)

.f?7

v4

nrw+4

?,,

ryt

'ol2L-L tt PFzY d7.9tffi

@

ry ryf'rrf

{T:7,'f % Ym%ir W

-,=y'* 4rq V rry N-

fu uH r*"'''a*'Ytyn/rq

% r*f ,!%:d

7 Y ?P nv7-J'rv

ry T,/,,n-tW fr,t V,*,+ ry

-io

rrh

ryrfurJ nh

/

W t4o h"V""y*,-A ry ry ru,?k/€ *ff1/

/-qwm,ryf'-+a

V-p t-r,rr-r-t/"oV ry

fit nd,Twr4"W krb Wfl"Wr+

wI lrry,ryM

fu_Wrf Lnopu,ng,f ^a+ow

Jrwp.r$rn Wp:g

lfnn TZ. f-T4 +T wf ryL*(?Ll/

q

'2

"+r)

e 8s /'e 3 st s

e)

Cryl^r,--t d o".f; "',.,*f-lL-, eJrb a/ fi*

b" ,LLo,',,s ilrJ I on<-,l"*f {a fr*

e,--lN. q-til n'/hr /./F, r. fu E '|,

%/ ,t' ', A2t F. ) / a-f 37 // 3s?/ 3?).

l(t

r( tC N,,,, i fu c;,,,k /-/h,,-^? 7U

nM /h^t< fi.-l %? ,€,ru f6, fu*

a d;6'r c''^'/ il ^/L*'r 'uzA W

*fu h-U runnnS il^f*,fr',Tte a,..*l X

A?y"^A pfu.l h //a,-*;1 d?-T/i a*L*/a"-,

,ffi,/ fr. n^Ta a^l 4 j,.-*t /

W {b /*l /,4,tr 1tt-o/,,fu 4, "E- 4,D,/ z,r^/J

/ ,/'

Cr',trla"D; f P* &r,,L aJJal TA 4

hfu, " rA /ru /s- %rr,^;.c %# v^*

4Wu4,.-WrurywtrMrvWA

-/2. f*v?v ryle 'r7.n7aty{ 'WO

iry f?.1? Zr ; /W ru > -,?e rrr'A

-wd ryvq ryry ryL ru

7-ru+V4 f-**, ,f ylo+? ?y'ry4r/ ?4

/.r*1,t4 k7A nffz de?v//**0 t

r*aTYffiW ff 6'"?n

?3rcry*uuryoY@

?fY*dvru ''

,), $rl 7 4 d ry/-wt i,"-??h d

!n*@ f f-7r/h ryt", A'A.

ry -Zo4 4 o/ ,-q.f % Nrytlo t*nO

@

?rD (rq lr1-y .YC ru€ rv r( j, l<?

z7rmtV ry4 T'-,.!,#N

, %f V*,.tnlrVW ry1 fvfkQ

?t-?/?1y 'fV?4ry yVry WJ

TL ryV Won Yrt rtT?P.e

, ry'ffiryq/yqt ry 'qrl+ m,,ry ta/

c,[,-.r?vr-*n

ry ? ryi fv(- #

?Ybn''CI

Z, v try,tr q1 Zry ,7ydW

f o,*,-'rV*r,l , ,+ TI-rtT 17

4*,q? v l,^*nr /r,-Try/-t*f! 4 "f

fTol'4.2-?4a /-o*

y.l.b y,a,ho V //t t,re!{qrql

/t'trry-*f

PrYr-0

fufu'"*.+nlvtv

'fufra

L f-+r(n %

//"*'*r"fr? f:fh

're *ef! %*ry?i -a+ ry4w.,i

.

r,i*r1-lrp

",<-?+ew A W

@

ryry77 y

f7,.* Lt- l.r.-*k-7 *! %e H /l,w.t^U'

?Lrrifr,rffi N/;l L*>,Lta;/ b q

Cn,.,.4 ; /'ufr, h ,fu' ooo'lala^

,U" l*;t* ru4 Z.;#T;L.-/4 ilttom

%,U tu * 7o,.^/ H /ru, il//a Arr--r-/ /*r-

ft*rl tL 1r-! l-u- /.;u,e ;A9o. V* ld /

q- L/r,n*/id- * dl,4'4 cpn,+q* @t .n* a*t

.4.

rlJa/t o

r

,b

dt;

ho*b0

a

tun **2 i/?"- ^/ / 'rt* "t-,yl+4'

ob l,-14 Z4 f lb+;fi I o,,6*,J d; /",.1 p,

d4*rk*+ c c^> nla r/,L r t)* + da,*'l=' /r, olqr-

*, ,4,u,w,^ub 6:,1 .r**4 /rfu-,4 t)/^;/', A/ro rt/J

4+A ePPE;{,.u, I ,tr't pW ya^4)cc /*,1 t'u.

/atln *A a- /r,uh;r! c"^J.-,t-",c LJ /z- t/-g

"Lj Sau4t{ sun^-r/ ful"r-*J ry bu ,tr,

y/a;l;|4i dd;) h,il 6n fr* @/d<'^,,..,h1/;,

Sh t't r- &.*^rk-; / Sit t24 ,,r/ )t>.

@

J- d;tr* r-r,,^4 ni YL*&A pnc,*.l fu

g/-l^l , ,,!^ +14 {;f rfo,rr!. c,,.-,11 u)tLr,^*

Oa,*^ -rl |n'tl /r"*f *, fu/l*ld^l ,' o- rL 7A*/,V',

elz;. Jr- fr* pa^^/ -or/rnt k;^0 dr b*fl 1,./*t

1L h,^;) ?-.lo,e0 ;,*,*A f,^/Nj h. /f.tJ,

br-, fu, ^)t"-* LL

o

o^ P) fr-"+ fr^, cr,*,] I u a/ on k.

.% trfurl Ptt,mo,t"l l4l7.rr.-^/* D.-

I fi* offo,'k$) '6 W T'*d ,a)rY.^/4L-

{ et!, fG. 9L Ul X alf-l a-g-u) n,k^

Ll*,l^fr.u[rJ lrifrh,' ft, h,o,l

nlL,^rAt @

X

4/lt cJ, ,L./,1

lL o/"h//-

ilr,.*0+' f*4 ,ru nnd*la 44.,,*,d1,

@

1>1ttctAv,.t<

D( ff ",;7 A++ra^k 0c "*l*f

b< tr +L of f * hr,"tt1 A [oab* ct- fr'e- t^",,^t

fU] a **k-;.0 N d^-1',,^k L{;h * A

fit Ld"l! "/ar f/* fr"., a7/rl^,,1 u4'qA

4^^ JPf " l.lr^,/rh r. furr^sk;, f?) e U ^l

J ?&, W ; oe,, ^!ro

k u,*.0

^'t,ff

n*

\1* uff+ +L+ fr,- A^{^rf c,,*l

^'"!*

O.,^ frLr. l,t l/hj lrrr-,,-L,,1 S;/zf**./; fu/dul

L i O" otri;Lq * H7 a"*'lrct,"*,'f

-il; ,/;1-fL 1,,*t.

54"N",) o{14 ca,*

*Ir-+ 44. u*i{L,

"lrr^r;-1 q,r, r)**

Xtt

@ "t1o,!.

ul,^

kuilr"/.c-, bot li)/

CW i,/n, lr- l^^*rl A

+1*+ fr* y"#u ,J

e'4 (6 ou I t'-

!*o^,," " %tt A,^1

/)? (r/'/ C), H?q ),fu

d4a/rlr ral-J ^,,,*1 F &n,-,-6 a

TL ry/*k'a,,nh W1,,*k" D4 d'*^/'J/

t

W A n ,*r,r, ruo/iou t", rrt+anta, y:l'r*'r

o*l ,Ck 7tr,*(:54 iuJ ^ F,,J./+ b,ar-e,

A^ A* i,r.-,,,^- % o-T)* rfu Pt^tp,r' '

+,Drl rU, *7,,"i L7* 4/r,^/,'-,-L

tw"-tiou rt, fu.n,n^1 ilf*bTL a.,-/,rt-/r^-,!

4 u-n t+r-u b'J tr^/P4 /--1"'-'a

7 ta"-t) l4', fo>rv', 1,1r.*t c--'ft /*t-l'&, J% ,tou tt '

Y"lV U*rq{1 lil A,n-, botr E)rl ,-/ /?4,

9* 0r,-/ I "ililt ,tt-,r*,tr-! R- /;T*7

b,-'il dg-rrra^r; a^ fl^ Vr*,,r.-!tf#

P.-^% S-/ "rr^r/ *.1 /'& V*U Fu'ttu."*

:6 0^ lrr/r,tt-g,,,,0-*, A- %/"*+

a"-,1 +tt A* a,, 1 fu ru * fn//A*-

D

fr*

dr^

le*l ,, Aot €A *f

t1 ? ot fr) ru/ /ht. L,'//t" ca^''

hn,l+,4 il* L.r,v 4 .D- c,r,,^* N 4',*00

tL/ tr* stt-xv,nta-r1 p:/rrr*

Vrr),J-*> ) W, '

th

M,rr"t *^-t 4t fu ( u-,-ta*fr

a^ /ua^J 1 /194 -H-j o,uLl

* ArAV Z- f,un/^J u-5 ri--.^*^/,

fbk)

T/,tn A-bry /,r.

4 fr* ,o//t'/l.nu d; u^Jt"

t

pJ4*l?

/,--* [re Lo 6l<

f Po/ '-

'fy qfl L*.*n

-4fW

q4 34frL ffryY ry'll-

'rcFY'4f! f, f;4%'*? ffnd

.nf ,r-,/,7 /-,-.@, rylrV I ,"71rU L

aJ % frry LytT -7

@ ru frfry+

/-, 1L ? rryt /t1*r7-{.rp

1+ Vry ,1.1<+V th

-/ //'8 'Y*74b ?'-/*ryz '*'+

?1177 /':'?f ' ryt 7 '*'d '*/- ?tr *

T/'w, /*r/'lwV*rlrV W] 4TrrV 1%d Y

(-*,"^rnl ry/ It L,*vtotrtl I'0 'y*?l

, o94:fy/d 40

t^"-*-rv-

"fb

tf*r,-rl"f 4 b ,*t y

/r-,.-bf-N /--wrw;x)

ry4 f, ryy a)

(tgdt'? trs) ttt fr! tLe/

L-,-,pd y

A

,Y no-,f o W

I

@

!* Pr),r ,J L,*,fr,-V, ?) ? F ee aj /fl'

v!*, (1r."+ d- A^- htuu,l ,l a77"J, ,/, rr,,,*-1,

kmT,fu,

4,irlry''r',-r-rrt, " 7*l O;lTr%,-twqd 4,p-tWbn,n' [;r n,"-t;* x fi^z nofrrt

il bL* Lfuq,fiua Lu /L. rrr/truD , //-

W +k4i* o'-o4l /* tu'

,./r* h*?, X* 44*7 na4

WY;,t -l ,u ,u,-ftL ( b*71*

'

0r o-l- {t {,r"*6,n L1 ar-l $2n'lr,rtt

,,,n"/-l b,k /k a*J.'A. furf

*, /,)-Z^,; Y/-r/ fr^t nr-h;,(

l,ar,,Zl A a-.c*( {* .rr.+r^1

4 ,4u-*ttruu.l PV"f"*J /-&, fr*-

P @r:4,',/,n r ta^a / fl*&

lL 6- Tl, o nll.t tztrla ah J er4 ^*f

6^l& / t

,-l d_,d

?^r cfuis't^2.,,.t, 1L t^,,.-{ 1 *n ^L, 114^

lN4 en .1" hncL^)t-, u1,,,^;-l ,f {" q,r-ul1

tL- difrrr+ Lo,u,{'E d-oa.,z^'; /*utt-,t if /-*(

A/rr^-rl ih /Ao",/t-. ^Vq

*l

*lN+ t/^*,u1*aJt x'ifuuJ W r*-9

fr* 1,

h;t,fu c,;T"n or,,A' L L-4 * rrX d;0

U e^!* {b,

v, ful--L,^L/, Ll} /.,*

-Aa)ua"l b^fr,"^?/ ?1 ] EU aj /?f. JL-

,,-,! Lr&acq)

')bti rr-Lq *1,*J f /'J,16T

h*+ /LU hr,.4/L( *,-4 /vua,& "/.nro4Zt''

/t'

0h nt^-t.'q- a^J Lr;'1 ,L1/,*;3

4 {r*hd D U) h-,! l'L^/, {t d) r4!-

"/r,t tvtur 11* ,l-,.o"lri"*, dr 1F

lvM Lr,j fr4 h,* ,PP,'l'*'q

-/- p4/"b"t"/1//l-a++L1' or4, dL4 L

0,.1! aa*,t uLr** vb fl*. 0 - ''t 4

ltrA<;*--Q Oo4^r,huol Nn .*/.

sl<4il h ",1 L^t//,/, ir 1 tr

[^r-l ;h (r4 t)h!,] * 'r/-JL

of f n t^h v( h /'*,/." /4C L i

a^qn^-,4"ilnt fl.- *.

OuA y>,1-t ^;^i,'j /-r,ll,^7r.,,; (*.fU,

Ahril nUt{, fl- /,;'r,-" at/t I

t*f

4 f co,l-f ot tuou-o-l /*rz-

f.;;*! td 4-1 o",

vP4,tvvrn!4

6*'t7,^^t L' U%or;,k,

{-r L"g', I ^ t0l^^a 1.1^t4-,rk,-

o

/lL-trvtl 4-1q Ur-/ r.d.rt4 N/ ..^0,.q,

W ih"^1}.1" ,"r Tzb, u

4- ftoucr)t,^ntr,, hf/,h Pou/L L

fr,iJ-l ,/f^o'qz,na n r7*

ocob' XA* 4lM L,/an-l

fa*t w'ft f?^? y k

na,JT-c u*U /"bbl !,*-r1tLL1

'a/-un Lr-. 9u- Mq;4J

,,t{ t, /l -rr ,J.l-/8, /"rL-

t/t'

/rrr'{: n *in- 4 ruor'k/r4 hH'l*,

Y:?7 VN '/'.t'ti^-e-Arl.orr+L ug-Yil.--{ k /u--t/.'oc,

[.: ll lT /,ul*,{-k^! dh, !4/" q

ffir*'rryaq

bi^, V/

J)? it,t rj /rt^fir,fr,^'ru.tfl*-

b,/^l- L/l ,fr<- vt^tlu %u**"4 { /"J42

ar^,fb, I /;a;d-?^,d"&ol U bpu q-

h Covr,rate,! 4- a Lntttt-, d4,- {ttv-r^*1 fJrf,*V

n^l;u fu P,-,trl*l L fr. n* ao/*--ft f4,

J* nuliu

l",lz tL

.J

ttu&*& 0

//Lv/*LTP*

0/h ti,,Ahct fuLri4.- %rrrl

tv;ft, fl^ d^*,a- A /rbrq,t J t , , / f A -

/ro / itz- ,rzt /-acL.&.J ,!l p*,*rn

lnt -rL *)Ar( h"L. Jara,k

4JLlrh- 1a)/t f o/,,/-,.al4;-.

-- n6JU.

d;,,,L

./

UU" oul. *f ;- d-,rf f-:^ r, ,.ofL^ l"r

St?**,-,1 F/q**,1- LJ rrIL^

'LruJ Ot^ tla/rrvlL \t ,fr* t

ea-.u ll\^";.l4aI

SLcc fL Wh'wfvlu-h *-

4 t'urtL-

}1/p*t

* b,.lr) Ur^t tt@

Otk,,ndL Ola* 6:

rh+t;^u + dd h/)n t;tbn4Ttot^ 1- &1-rtu-+2 @,.*

lyt,uthn +/ ctu,,^m

dll Y;l-k aa,,l1rU44

ht. /";\fu./tL /b/*l-t| / D// PA,n

A"6,^z tDh "u* bilU L 0., trt

ai^ /,r^ rtd t4-j A Lu Lt>ntrL/=g oq 2a.(i/dl

!,vt'/t"-u L* "* 4,f o1y".l*fi L aL)tu:1 .

YL, fl&l b,;ll a,r.rr,,f -L"l b,e* ,fy*q

/(/

Arhl 0.a.. %n\\rr,,*fivj p<-r ,;7-.0 n^. l-;* 1",1 ,A-;

(\rur- l* fr4- b,,-,'li or&- I N"*l* P, l?(Y

hrGf fv"rfi^l4**- an.y,,--* d- L*

IU Vtr*|a,a| g-; !)*-!^l k ^,f&-! @{L

w^Ir. 0k fiL*+',/b* [;--y,nln-L- uilt "*1

0Jfl,'4 \t^* @ffifuY.]al*

q^h A suln*[-1 rut d2> ,hffi,.*<-G

t---+', or:,ltn t n4;*" ?/ lht?r-U 41

&,)d! 6."- p"/,.6 ru,lt/rL /J ."*Qi

llr,r-,-J

'la ;*fA p*;, Jo, fu* q,r,- 4,[L*

4

,n-fa,/^-, 76 r'w,u*e [- fun, ^7 |r^/v*.f

h, *" l^/),c 4,

D/,^ Lrh* r. 't/o"-//-", f?f E )J 1o

(tl4 G. /ete) fl-. l/146 /J-/ a h*p/*

'-1",^ h pr)h-, e,;h il-" t/.*fi/ r/'&' Po'*!

n;t,1L +t"&,t.^,"dl ' ^7b T/*

t"-/A f ,a4 7ta,4A{ ^T/u?.ilJ,-

n,fir, * hna^.r0, ar ; f7" '/**'fu, 4 th' /4-

{Lill

r^{t

14( Su"*,*T t^/1*/, funYa*t*t^

bdb Lilo* b- drLr/-.'I c",/ rtL'r.{

u /rfu ,fr-- f, l;+t or 4-Lrrr*,?

f ^W

ru,?,^-7 d^{r?**rf ); dr./r/ X

ft*-

dl^/r^,h. lL p/,.a|>pg fL^ /iJ ^ ,,^u,r/o,^

..6 M/- /;-/L ,A* c,",^l( orb oq ft- V,L4

.{^lA.l ,. \h,,,^fl-^.,f )t E>l 1t,(rt/, C,, /q%)

6

. 0,. W) ttg A;Virl ur*\ oduu,t-

.VaU)A! 0,',-0 fr* b* t-p,,^,a^,lzl {. fl-. l^k/r}

Lo,nl P,J ft,Dl tilJ- c-,^-l I Mrt{z}<-l, ilrr,*/

n,+ e14 ll-rt 0n ulru* y^7

d-rl-r"A^( /.il-y /t* g,+;^-e- Tldt'

lq- P ,u{)ru- dJ o1.L of/*lr^+ kp?^*

O-l ar"j*;f N-v,+or*-/4.q l^/ tfto ^*/a n4

+ ft" L.,'-t' yt)ar t ,h &.a.. u-r/+ a /tA.n)JL-

i*t po*w,t^uV p,-"tr*; t L-'-r'/ k f "J"0 -7-^,t

'/t"> a/ L.

lilt- /,r"r* nlbn o, )n n{t wb-,l

Tl.*,,/ u& nLtu_ -'( y',u-nn,y'

Ot^LbL q t-lrrtG)) h Lq,,r;

y-l)u {-'r^ u/Nr!t- p*fi"o-4/-

-Lrd-, /. nau--H ,^L lA,- U

khA'. -1^,,-^ LJ;r4o r-ln.-. (lg

rtu-i-z a.r

,

{'( 1/ f/*

'Fry. \ cf

|--4'nilqa,t -@ a,|n/ W/ ffi

ru fum/ aJffi4 m*Qfv7

/n/n4Y ru m rlry r.:4"r rc

/b rr(3 22)Yv7 //ru

'?) r:z [ /'*-'on'* a)

-il(-7 7"V'*?ry A-ry

7///?^4/'vrile 7J 4 C

b?rJ uz-.7- TL/, 1?--' t"oQ-vt4/

aJ% w,"ryrW - +7 t hea

+ /ry? =U,'t. T,W,Y

vJory qF4/ery'kaft

' ' Wr,try"rt nwp;A?vry*r/ re

'tuTry? v b ryfwTT,uTV

% ro rru,'ry ry4

??wrnl ftL 9"td ?)WW

T/ % ?.1 *rt Au?uru t'-TV 0l

4 Tfylry7urJ Tr fd ryll/

"/nna fr?

v-? vr7ll h7yra.WV

@

l

t

;

,^l

e>

,Lub"h ^rrj#u- { LLa*)1,

ful*^L L-a- W ltlco^ {^rf-/*

lrlc*il9, 'L e*Y-/ 7*

'ru h,-J h,a- /J'n,4t h a,*^h-

0u /7-. t'ro^,+l*' ,4 y/t."1;4

h-/ lrU*, 4" re-, >rnli"o

LLq 11- L4^,/r,J= or t7* ',r.*( ).4 bta.-,n'/* r r-lrr*J't*/ 7

arl/*; {l 7ur,./ e,-,4 M

t!1A,,4 {". 44^ L/k-"*;-

4 il"^*

^Ar,-r/l

PaJ

,9,

^,/U

rA 77^r*,{L L u,* 7,

lk-lJ*-'td p,,>/.-

,fu* r^u/r* ar A14*1

iTL; ua."iH t

p/a'J;g, oVV,r*;Z, K

dllfuL^P / /1k-,)./ o'n 'tJ

V4 "# lx>,,0.1 ru r.'y''-

Aq^ #i* 6;6*fL-#.

-l cl

UrJrC-rf, fl,*,, r?/2 uY// *, fu oftzq

U,ur/- f ()nu-r--0 P-;r*rl, u/v k 4/.*J

/*,24 vn4 ffi

//

O,\ 6 rLt/*Aa--.tn//o,

fuy }r*n7,,e,"--/'9 4*4V ry

-T?..ty/ f*.rfi$),ae ZrI Y ftAT-1 ,nqrrl

I er??lro *n/-

+T),1-?,rH:/ql/ "ft T ?jq

,-*d tr-4?, ry n?-lg.'/t-?

I y,>t t--t%,/ ?r4,

y'cl hoq

r

,.bq// V r7q vn '(bLl/'ru yrsT Lqt

d fno:/.,rr/d rurV/

4/,,#.v t ry ry v+q) ru 4 ry,'il

a

a+ ? 'vf /"-.ry /f{ s 4*t,,//o

* /yn, .rr*rrl, urt t?w"r) qp ty--r-*rlro

ryZ Or 7*rz'27 'er? { 'll/r*:/ffi '?.*rr(,

1€ -/",-r-., fnfz

vO

t*nt

v#

d f"r&r/

Yea.r-2/Ya"v Ta fr

tv'"/i q Y ry

ry4/rery 4a r v*%**h

f

s.,.-z te+zxtzTe

7u/ W fti (! : a?,{+t

ffi

I

' rTaue

t,+;7t7/ ry

63

l"nff "7,/Ir

t4,r n]-

G9

W l/a^il*;L p:ft-'J . a*7d/-.7 &k Lk"n

/* Vt-. /.1,n n I ^A1 /sl, fH aJ /(4 fu,,t--l-.<-,.a;

o rul ,rI* &h-*? ?tL.-4 &*;J -r/*

% y,ah.tta. le4p*r- /hct.<2. ?zqacq /-P t4

u'( d*'^*t);@

4 o " orrni ?nrZ /uL1 tnu./ rt*r1;/r.att- 'r /Lh /"t"0

'[ t

O+t . /dr.'h 7t*'l' L*. 4aaQ,rt(hLfrL-4 L*go*

I rc* kstt /*r*4

-a

g.,'Pl 7t4 /^lt * fr 1".,*,>- Ft*L 4

?r*g ; 4.*7 o/,")/4 -/,r. /r/^f /, Lak ol fl.

ki j utt-, b**t*ocJ u, /tL*-L , bo/ E ll 4j ?/r'

6

3h y/a,-fi5, ^*,,-lni;

tarr'

"/t,,- + itu- vot|^I ralls ryfu 4 d4 ULr*,

U{ o^ du ptar^};gr' tno/;n, Yz* +/LJ/

W 4 ,u-r*,t ^ + /ir"r> TL aqh-J *. /-Jrr.r'-

I

I

!

t

@

* <t /4 4 t/-r; ,q*t wLJ /44 a,-*/ h-

I

qb*A' , fr{ dift LJ

U.*,0 lst ordt s. I* fu & t./a

a @^-,f ,^t "'al)c- 440 14 Tt 1/'1

i ,t J" ;^ ,)r;^ ,-,^r* ru 6r'it

,!ln^b eilplt L alZ"i , -'A,, E4 klA*l dak4/ 74

b,rrrl g,, tur;*! Fe F*il tAu,Lt, 6 tZ^; tu fl4-

,Xt,tr,L W [b4 Cn,*,l c*n4 ,n*{ t-unLiL'l< L

W* nfi/^!. frrfuk h ,l/* ld; X h,,f4"/t-

gfrl^bd i", hAflr"-\ fra dr-T*" /.h'rJ,tt'*ur/,,, /'h^l+ ,

bo4 ru * 36?,

BrU ( fr,a" (rt,^t{i ordlts IANJ,L u)4l2 vat"A0

A^ a4rtL&. T1. co,,^l 1, arffL,lt AJ*l 1T- l-",,t -

(^t

S,hrQ[,

U,t'r 1*t+

od^on V y"{r^l ,tuu-1 # "^,-t

4, ne lyn*^*s 'i),..a 'l'..0- L/1^ a.v !,,ttLor, il*

hA t a,fl^-rA 'LLI/ /**'1r1 trL

h,.+ l,re^ W*'b ,^+tn- o*A /*l nol lQ- f,^l

a /.14u/L^ * d;^^;-"

n ,4 rllzlrrcQ- kt A .l/42dr-9; i YL

7lL*;,,y, b,^/ fi 'dr* , ! A"

t

/^r-

Ll,y,rrb,f-t trry + fu t a ,tt- l, Ott'wumat1 A'/rtl*"i'

W ru lhffifi {+,1 no r),t),A,.

fL^*&ou^^*yPyd,dW

dtr*,nrd ,'r,*dk- Mu-E- !"o* th

V,r*h;"1.1 4 i* "t, /D.1 . g/L, , uhr#"a y/r/ fr,z ;ill-<f ,

y^lrrr^l (fr frt- lrrrr^1 wo'''-Ll Lz

fuuA ,b, 9t^11pd a NhvLwtd++

@M *L LtrL cud', a"Ja t"d"rrqA"r2J, Lrr 4a *^/

6g*-;.d-; t*ol,o^ ry? ,t .t v'tt t-

A- 0&o lt il^efir! otr I/^L -t Q.rZ,

V* fi,& 4 fr,l- (i4, A^e.r"rl<rt

A a///vr/1lt dt fu.l"ruJ u" l, ,'*d /r--

m) hqqt -bt+ P

L -nJ Yll '4 F a,nt4|ny'f 'tro t{7a

,*lg--*1a

.TLfvt\5$e?o1U ry 1. ydvf{fiV

q)1 v76aJo

f% !)*n +72n 'D w

*r?,vrw d y:-r;r:*?t

T?qfia/g 7rr.; L-ly +ivwT) V"l '+r?T ?rq 11

YTIJ q nf ? I*JW'fa fq\nfl V

w "7rd

,'ur/Uq

,'

, y^ ffWo v{n a ffi'm ry+

WwT,Fr:"w) nt^\fl fr

b':";,rdJo'uq

"fif

"riflri\

,YY+ 9

y y-*--tw f ryt fn ?4

1r.d^,$,26

* +.*tfd

fl -"dndA @,o,1 )o W fry4.+v \ yc"rn^)

f'%r %f t'o? 4 'W

zrlry Y./4@

,?f{ 4 ,,"t/;al*f ,ry*vb

€a

4l

At*t k n, f* !/*,^Ll fu ,w-a-/:-

0.1^t OYfu Ad /ttro/"j " @6<za-'1/rt-"M-

7 7t,7 EU f/6( lna, /?/t)

L A*;b 4L*roqt+P

',''lrl- )rrua

{*

fr"-t f,io't a,,-fu^rfr/"

A a/-*c # lq^^,!

",'Y^rr/6-h trbrf Mry ( P

,i

,tl

///4 u/tl (, //hi^r a-/ r't/t y''t-|/'fr'n

:l

:{ fu O,/^fA WI7uM,n- V.*,fI

P/,14,ytrn/-?V dr;/M

Wf Wtrt4 W-fry6t,uh7,utt1 .u

yr/ th /ri W$,*y*"/ ,ry't,.t

A /fu Wi no"/ra, /ar /,w*7

7af il

wnlu&)1, t;kn aM.4/A 'l* wu d't;J

AA?rrk r,*tiu u.*r)A PuJL ,bG) 'tL* ,6'-

fuf-lr*+{ hu,lun +, *7 NN ua,tlL'

drJL nL ry L bv ^r'l n,.l;(,*,g 5W "'ru|

l-+ W \rdu,l a6tr^tutt+c A"' u"^d

X

il^LJ h @0, Xfr* f hr,lrt +14 A,tl ,l@

goL-d,

-/*0

LJ

J^ bt .,aSL /. fl-ooru's a*b*{^- tI^J

i.

/Ly,/rr/^-? ef F", . li.n

/at-Q*- u;ili /o

a" r7r,-l '/4^+ /o ro/ d;/.;r* b,-,1 r*ll

/ot/*'4t'L+? Nfr*t

/r-f f ,4anzt, d/ 7,t 'r;/,-Q

flfuro,tl L rt/, "(u*;#u.J,ilz l^/)r-e-.

/' ltua^n H'*-

Xlt-o,;,l , Jo\ Ez/ *fn. ( L.u, ,/ /,J'*O

a*/ @ Li i^ t-l '?,//- /"J*;'* * ru-4,aqfl

a

t+A

P?**.) d/+ %7a-,4r, i *^4 #.4.-*,6^,^.{

,UI*LL ,^ a- irrrJ 1'r4-C[ Cu rrrrk c"2z

th*.rtu. 3n+,un/ 656 F.>d GtbCs'ft (;, tXlt)/

#t^t-'/,k W L),t -L'J /Ld;l b ot',

*f L-l r^tt- L %e o,* ,1yrllr^l't a*lu/,^*,

?A^ ft0^ cu^t,re.

-}tq furrr,31 A>*J d,"*,^@

[h ronz h; ["*r4 oi fr^a- ot"r',! +t^) +1""^u

U

dLl **t ;^.rt* L P I !;tr-g f- . -!.-l'"ott- v ' fla}+ +

!ilh.: [a- , io I E tl el >r d . 9r. a)su l))l-'')* t '

W,, b? L € z/ trtb ( rra a. /rt, )-&,to, .

L, ?lbrt f>J ttol({H.c-'tZtt) Jl*

+14* n'"t-k ^ L

bd, A*,.,rrrr*r^@*^l P"^IL

lrrJ.t-6LG) i tt, W ru,.l,q qr,*,a^*,.d

tr'

,,1" A-6-il1-1 P*{, n4 /r. pd /4 t,/-*s, " 3d'

((

fl fiil,'tfl,ru 3114 Td^-f &/^+

qn )anc-o- U-ir^^^

0d. W 4rr* w t ^d

p.,'^',U,r 1"

-tl*

W+ u,yrrur,t.Jnl "*! *,,6tt,^,r. 6I,,,,<.,.,u

{fu tffib 0/r# ^{^k b 44f frrL Pt-rnnf,6r-6r-^r^f

w tr fir?^h frfu-t a/^ &/0AL

pq ffw,.,t ,r^+ ;t, ttru,te nff* o^j 0n-

upfo W+, td. lr*& tufw l,*,,r.',1

p1.rl,.l"t i"rw^i.rL$ P''$^* b,^t

o!"^ /Nr,,E[ l^ilehu,N WrLtr^L ryp,q

+ W /'u,r/*f t', 1 fMfr'(i el-un''r

fu ,ffi, Uxr*+ Q^ f@ 7lt hlAr4 al

eil)Wi- oceaq*'^s blutW flllt Al" wa^L,!

'klb c*-+ {" /1tr/4^v{ pq"^,*fr uil) du,;

()r,frt W /,L lu'ilhlrtu/ /"*^r/ 'lad /'Q/,,,

1,"-0t o- .,f , I-" ry Ff //'s. fh bo,/

1t

ob,*rJ lk . Ut//a\ n*|,b, ,1n pucttklua a t

d)u/rr^!^b ,b tt4.t fi- t^ /rr"l"fr4ild 0,4f,-,i

b* a$tnort nfuirA4 %at l/rl tu^il lbf

el b*t WbL o(iln,lll or trr*.41 6/

AffW * Ur^rl-e- lrll Wzfi a ru/*torr*,/a.n-

4 h/// fr TAL Pzrr-d a^ -fr- il;' /vl'o' /,r/b,

D

'4N-, dr-,^!l fr'l^rt^!- % V^at, trL urnl b

tar-rl-[ a- *+ W;lrry l^ ,rbr^ r,,nDr-o- ol u/J

Olf,W+ L b.a dr/,*,4 t tu* 6rt*

YPw b k 4 d|,uvh/ fria.tvtmaT0,.

I

trM /a4,uL!. t/ rv1y'/.

Jk Mrfry pru {-W r^yr.*,a,t *

Ntt)-/,-4 'nn ryL. lrrfurl -ru lr^/rrrtu

brrta.ftr"r^rj a tu/r,t f W fu,r*.^L

ry t d;C,rr b*i ddt" p/,h,tmga4a//q

a /il*^nla 3 frlt^, fu /ra,lb 0Tu4.

w

J* lar; w [Yo" ng

lt,LLte //a/

.l,t{f u},{M}L Ctx,^,"1 pnfir;,^t* (N/t- ,*,,* b,tr}L,!

+ at^ awd'!r,{"r^rt Wrtttr^ric,Po,rrfi

{rl

ll '^ /?

' i a* /"^k l<,ov::L Wrfl, Prla*,u,,ws4

:

.b,@ AffDrW h fry* d,,rf-/""t h ruJ'fr^!

,\r* fueu,v'tutl4 edqwhe"; frror t

/la,lttn fur^b

914,L t, d^t * e,,4 trt h,eu/

Plk 4. a-l-ltq-alr,au l"t 6n 4 '/"*

ItJrh^,Xrf /r/il^d" ofl*/& e dr/+*

(.,orPtn Pru^;* /- {'" t*'l'f,"'"1

'-furrr,L|, k i a;*/ u-t- ,/^;.9,

14r, !rh"* q p+oMt* ,*o\t*

Fwfoz t, + W b,lrfiu-

thrLlr4 a&4,u-/1 atlq,%;

E'uN'lt)ltiirt b"L'dfu7

+ arr-rrlt p4,*,1 Vt"i,/'L;

K tn/t*o"W ryryL)

tr'!-

4u,, 9 , fl. A,/,'o ,n ,Lor fttttztuuaL?

,/tr ?* rt;ril4.t o/,,u-

ityt 4 k b,*ilI ?anori,pq7p*41 k w),*t^ uildu"c, 'iturl 1^-

wil1", +-; aH-auh ,

Ct, t,

lH/-&

.A^2

/ f?/ 0, t, "J (o-f I(.i4u^

C//12

IllS /- ho u/ Nt,1t t4A4 (Wvr'/.-l ; F*

erlb $ru<.ian' l1ttrrt/-' Qrput

Ad-, I),,L dknhf A;-lf (,>t N

rna-ffirk + uAoH W che. t1'7r7

k tu+rr"*! ) lYttul tnVlrX 4 ,/-^^fr/t

iltllrh p/,,rtl ,

-

I

I

l

I.--;

I

!4

YLat,lL)rt,'. *11-o^,4l/ U-t' # ?/-tz

W/.h- t u,/;A yu-llw TrtL b,.nt P//ous,

1/" C,r,,l- fhu" hrtu{ ol t @ ,['*-

frT,fu*, rtu"tl b c,/yulal d-* ofrry

d, Palr)*T *r1tr,"r"^f i a/Vtc*/fi*, ,t' F"^

@

lua,n,{zt l1's, at E>-t >.

,, (-rt a^ra o" Lhru lr tt/r"q fru lril,e0( '

U,r- ayt D'tE at IAL ru kkt Pfu il-^t0

i,

"brt- h/!* W'fr/u- W^h,4 1, /,,11

furrrl,ef tu/ '/,/, uJ ry

0;;yrfur,'lr{" J- [trL 6^r,f 1U dLfrrX tu*\'

, +re

/ru,D 6q-oNa7 A4I/^/\o

-h,,;iA"W [N- WIi;- (

@ rt' k'yrloJ fuk, b,u[ t^rlhf

u,^Lrt 2 F l/. f .c, (at€ld i,O 7.,o 7 r.r/*,

t tDl^rIJr^ a /r.y -/*^. D^ L/J.

S{z 0-"q ,?rrnnba( v. /14r,1r. q 4? L/. f.; n

Ltiltt)r' Jou,vt y-^J u. fu-, , 3?z U.f, eq 3 (tvt)'

% ? -vrrr/4y ) i*e ^D

futryry %, !,yT"*zfifryZflt

ryfl nn Yfa

yTffi/rr,-r-T? *Jrq %,,4 ?Yf,ml

,wq.d ry W

u? )*tt re i UV: tntt)*v-7ir

,7W ,rnvfu fru h iw) nW vra

,

. Prrr, @"ilyy-,.1 yq Tfi Wuo fTlrrl

d

p>turpm nft hMtw

b /,r,z,rr,* w 4

rc frr{ v(t :h*rrr?

m,l(tLb-?- /Lrt 'r 'r) Lhh/

ezt

r+wnTrTrbn M /wWrl)'(,,+w?%) rw/ (

fry fo'?y.n rr4t

irrryt wr)

vd4w

wr,

yffi,,uts O,4rbff^; /M

fu na/aAf /*

ZZi b,ilkhl

/116# o",*/ Ia Pud

lrt( dtw"nthtl<A frW (( lfu /4a^;L*

7,ktw/l4a-/ /,- '6- l(t<' 444/-

furu,r,,^

Lru /rrilrru ,%tL p* r.rr; 7 ( ) ) 9( fl/ tUa''4

v0,4. A)llia,*,t otn "Ca-

gfo fu, f,Q t44

-/-, 74*t

M "4/ Ma/rj"n a //.fu,r?^dtcr-rt-,'; /i/,,r-".n,

:.

6rd1il,0 /,--0 Wd-'v'/-'*A fi* T'n! 'u<-a'J'

In ,a da*rt1, tr*= o*r.f t/r-lol'

il,- NfurL ar*+ . .

atwrw+ purinJ^/, alA,nt, 4-

AW ,!44&A o,*4'+i ,,r,i"r,*,

I 0r0^* / A.r/r/ o- /* co,ra", ,

orn /'l^'ffi'L /''lr"*" tffi;"di/b,lL f,^- dr49,

t. . fu ctF-

h,lrr";J /; ft lvturit o c"-zj

,, + ^il"ur li("'ir* b,n-l-r

'?m n/),rr ;ry/lV ,U /^"rfrrt/ %f

,4*rt '''+Vn/_ra ry %/o M

a"Jy,ry ry M

rTA

trL {n /n*wry *"U {"1 tr ,Yr

4 ru-#ry ,

ffl. tvi u,.u ? tT|

-wT,4 4 fy Jv rury ry

ftrr,l,,fu y'rrtt ry !W(-4 v,wVV,t*e 2{tf

tfuuryf*fu',,/Cewflm

ry y /7v-ryrrlh 1u

'-'/m/ ry ry

tr% fua ^$ vtwrTVY t*9 )?"'rf'/'l'A

W>z/^w fjrt 4-r*l ry mvV

)w'2br * /tL

'l{r"T

qnu

v/,

W7w W/