Hall v. Holder Brief of Appellants

Public Court Documents

July 10, 1991

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Hall v. Holder Brief of Appellants, 1991. 843cc627-b59a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1b143b39-f519-448a-ad54-fe5f97ab506b/hall-v-holder-brief-of-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

r svt'esnĉ feosns

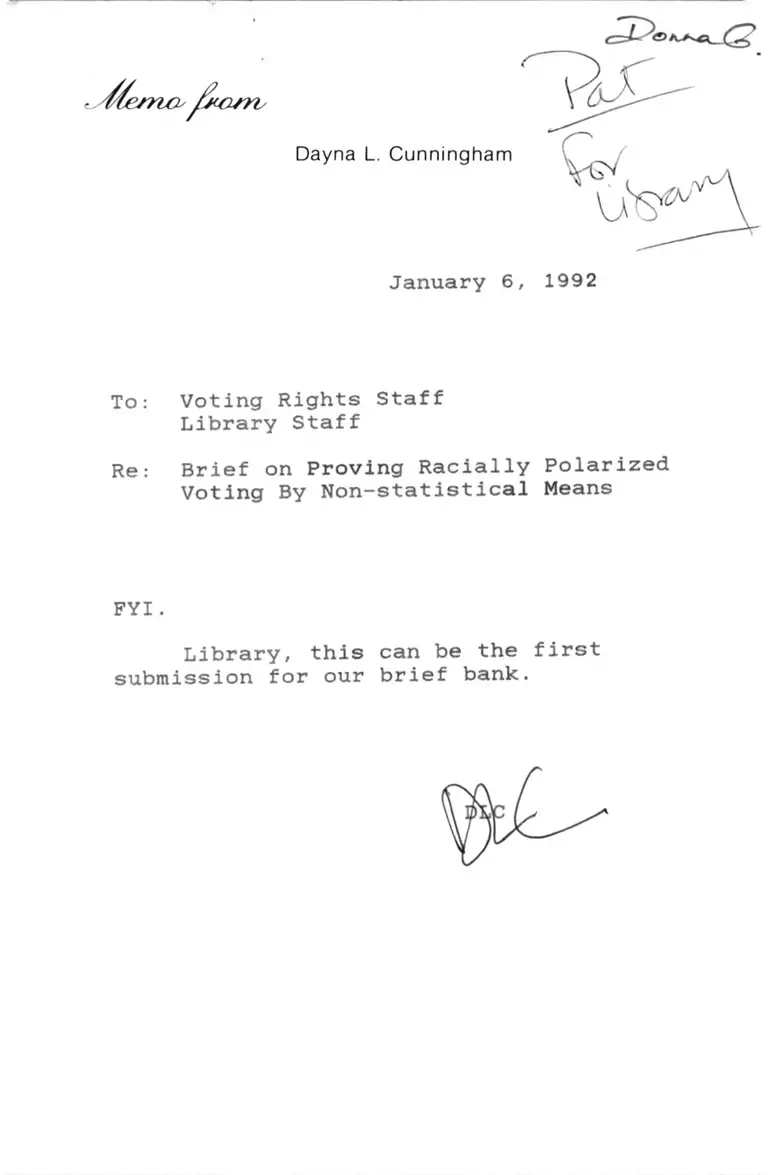

To: Voting Rights Staff

Library Staff

Re: Brief on Proving Racially

Voting By Non-statistical

Polarized

Means

FYI .

Library, this can be the first

submission for our brief bank.

4

tyUL 1 2 1095

NO. 91-8306

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

REV. E.K. HALL, SR., DAVID WALKER, U.S. DONALDSON, RICHARD

HARRIS, WILLIE ATES, REV. WILSON C. ROBERSON, and NAACP Chapter

of Cochran/Bleckley County

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

vs.

JACKIE HOLDER, individually and in his official capacity as

County Commissioner for Bleckley County, Georgia and ROBERT

JOHNSON, individually and in his official capacity as

Superintendent of Elections for Bleckley County, Georgia,

Defendants-Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

MACON DIVISION

BRIEF OF APPELLANTS

Christopher Coates

Georgia Bar No. 170980

111 West Washington Street

Milledgeville, Georgia 31061

(912) 453-9512

Mr. Laughlin McDonald

Mr. Neil Bradley

Ms. Kathy Wilde

Ms. Mary Wycoff

American Civil Liberties Union

44 Forsyth Street, N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

(404) 523-2721

COUNSEL FOR APPELLANTS

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS

The following list of interested persons is set forth as

signated in 11th Cir. R. 28-2(b):

1. Reverend E.K. Hall, Sr.

2. David Walker

3. U.S. Donaldson

4. Richard Harris

5. Willie Ates

6. Reverend Wilson C. Roberson

7. NAACP Chapter of Cochran/Bleckley County, Georgia

8. Christopher Coates

9. Laughlin McDonald

10. Neil Bradley

11. Kathleen Wilde

12. Mary Wycoff

13. American Civil Liberties Union Foundation

14. Jackie Holder

15. Robert Johnson

16. Bleckley County, Georgia

17. R. Napier Murphy

18. John C. Daniel, III

19. W. Lonnie Barlow

- -__

. >;vm/. WlVt.

20. The Law Firm of Martin, Snow, Grant & Napier

21. Hon. Wilbur D. Owens

C^L. si '• 1t ]jl_y? .

CHRISTOPHER COATES

ATTORNEY FOR PLAINTIFFS -APPELLANTS

)

STATEMENT REGARDING ORAL ARGUMENT

This case presents important issues concerning the application

of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. 1973, the

method of proving polarized voting, political cohesiveness, and the

denial of equal access to the political process. For these

reasons, counsel believe oral argument would be of assistance to

the court.

i n

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS....................... i

STATEMENT REGARDING ORAL ARGUMENT.................... iii

TABLE OF CONTENTS....................................... iv

TABLE OF CITATIONS AND AUTHORITIES.................... vi

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION............................... x

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES................................. 1

STATEMENT OF THE CASE................................... 2

Course of Proceedings and Disposition in the

Court Below........................................... 2

A. Racially Polarized Voting................. 4

B. Discrimination Against Blacks in Bleckley

County..................................... 13

C. Discrimination in the Political Process.. 18

D. The Depressed Socio-Economic Status of

Blacks............................... 21

E. The Difficulties in Campaigning.......... 22

F. Maintenance of the Sole Commissioner System

and the Majority Vote Requirement........ 24

G. Geographical Compactness................. 26

H. The Decision of the District Court...... 26

B. Statement of the Facts.......................... 3

C. Standard of Review............................. 29

iv

*

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT ............................... /y

ARGUMENT AND CITATIONS OF AUTHORITY................... 31

I. The District Court Erred in Failing to

Consider, or Give the Required Weight to,

Relevant Evidence of Polarized Voting.... 31

- II. The Court Erred in Holding that Blacks Were

not Politically Cohesive and in Failing to

Consider the Relevant Evidence........... 40

III. The Court Erred in Refusing to Consider the

Discriminatory Purpose and Effect of the

Majority Vote Requirement................ 43

IV. The Court Erred by Refusing to Consider

Circumstantial Evidence and Holding the

Elections Were not Discriminatory........ 47

CONCLUSION............

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

v

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases : Page No.

Bailey Vining, 514 F.Supp. 452 (M.D.Ga. 1981)...... 38

Brewer Ham, 876 F.2d 448 (5th Cir. 1989)........... 42

Brooks Miller , Civ. No. 1:90-CV-1001-RCF(N.D .Ga.) ..

.................................................. 3, 30, 47

Carrollton Branch NAACP Stallings. 829 F.2d 1547 "(11th

cir- 1987)............................ 4, 9, 12, 31, 34, 44

Ci t izens for a Better Gretna v. City of Gretna, 636

F.Supp llirCE.D.La. 1986).7.___ 7 7 ...... Ti .7777777 39

City of Rome, Georgia v^ United States. 446 U.S. 156

( 1 980)................................................... 45

Clar k v^ Telfair County, Georgia Commission. Civ. No.

287-25 XS.D.Ga. Oct. 26, 1988) . .7. . . .T7....... ........ 4

Collins v,_ City of Norfolk. Va. , 816 F.2d 932 (4th Cir.

1987> ............................. ................. 32, 38

C o n c e r n e d Citizens v . Hardee County Board of

Commissioners, 906 F.2d 524 (11th Cir. 1990).. 29, 41, 42

Cross v^ Baxter, 604 F.2d 875 (5th Cir. 1979).... 37, 40

Dickinson v^ Indiana State Election Board. 1991 WL 82414

(7th Cir. May 21, 1991) . ............. .................. 44

Dillard v^ B_aldwin County Board of Education, 786 F.Su d d .

1459 (M.D.Ala. 1988Ju" ......... 77.77................. 45

Dillard v^ Crenshaw County, 640 F.Supp. 1347 (M.D.Ala.

1986)77;............................................ 30, 44

■ Dillard v_. Crenshaw County, Alabama. 831 F.2d 246 nith

Cir. 19 8 7 7.................. 7777777.................. 45

Bast Jefferson Coalition v. Jefferson Parish, 691 F.Su d d .

571 (e . d . La. 19887777777.77. 7 T 3 -------------

vi

j- iM iJ Ju.' i tl x*'SuSCieLi w

Edge v. Sumter County School District, 775 F .2d 1509

Tilth Cir. 1985)........................................ 46

Gi ngles v . Edmi s ten, 590 F.Supp. 345 (E.D.N.C. 198M

Hendrix v . McKinney, 460 F.Supp. 626 (M.D.Ala. 1978).. 39

Howard v. Commissioner o_f Wheeler County, Georgia, Civ.

No. 390-057 (S.D.Ga.)................................... 4

Jackson v. Edgefield County, South Carolina School

District, 650 F. Supp. 117"5 ( D . S . C . 1986).... 10, 34, 37

Jeffers v . Cl inton, 730 F.Supp. 196 (E.D.Ark 1989).... 39

King v . Chapman, 62 F.Supp. 639 (M.D.Ga. 1945)....... 18

Lodge v . Buxton, 639 F.2d 1358 (5th Cir. 1981) ...... 36

Lodge v. Buxton, Civ. No. 176-55 (S.D.Ga. Oct. 26, 1978)

77777. 77. 777777......................................... 36

LULAC v. Midland Independent School District, 812 F.2d

1494 (5th Cir. 1987) . . ....... ..................... 41, 42

McDaniels v . Mehfoud, 702 F.Supp. 588 (E.D.Va. 1988).. 34

McMillan v. Escambi a County, 748 F.2d 1037 (1 1 th Cir.

1984).... 38

Monroe v. City of Woodville, Mississippi, 881 F.2d 1327

(5th Cir. T W 9 ) ......................................... 42

NAACP of Cochran/Bleckley County v_;_ Bleckley County, Civ.

No. 88-32-MAC (M.D.Ga.)................................ 21

Neal v . Colburn, 689 F.Supp. 1426 (E.D.Va. 1988)..... 22

Nealy v . Webster County , Georgia, Civ. No. 88-203

(M . D.Ga . March 16 , 1990)................................ 4

Nevett v . Sides, 571 F.2d 209 (5th Cir. 1978)......... 33

vi 1

Rogers v . Lodge, 458 U.S. 613 (1982)...................

.................................... 1 1, 36, 44, 46, 48, 49

Sierra v . El Paso Independent School District:, 591

F.Supp. 802 IW.D. Tex. 1984)..... ..................... 34

Solomon v. Liberty County, Florida, 899 F.2d 1012 (11th

Ci r . 1990T(en banc).................................... 31

Sutton v . Anderson, Civ. No. 89-58-1 (M.D.Ga.)......... 4

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 ( 1986)................

....... 9, 26, 27, 28, 29, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 37, 40, 41

United States v. Marengo County Commission, 731 F.2d

1546 ( 1 1th Cir. 1984) ................................... 33

Village o f Arli n g t o n Heights v . Metro Housing

Development, 429 U.S. 252 (1977).............. 47, 48, 49

West Gulf Maritime Ass'n v. ILA Deep Sea Local 24, 75*1

F . 2d 7TT"(5th Cir. 1985) ................................ 47

Wh i te v . Regester, 412 U.S. 755 (1973)................ 46

Wilkes County, Ga . v. United States, 450 F.Supp. 1171

(D.D.C. 1978) . .......................................... 38

Williams v. City of Dallas, 734 F.Supp. 1317 (N.D.Tex

1990)... ................................................ 42

Windy Boy v. County of Big Horn, 647 F.Supp. 1002

l O ^ t r i g s s y . . t t ..t t t ..t t t : ........... :: 34, 40

Z i mm e r v . McKei then, 485 F. 2d 1297 (5th Cir. 1973)(en

banc) . ............................................ 3, 34, 46

v m

Statutes and Constitutional Provisions Page No.

42 U.S.C. Section 1973...... -............... 3, 8, 31, 44

14th Amendment to the United States Constitution....... 3

15th Amendment to the United States Constitution....... 3

Rule 19, F.R.Civ.P...................................... 44

Rule 52 (a) , F.R.Civ.P................................. 40

Other Authorities Page No.

S. Rep. No. 147, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. 28-9 (1982)......

............................................ 28, 31, 46, 48

H.R. Rep. No. 227, 97th Cong., 1st Sess. 30 (1981).....

......................................................... 48

Cole, Engstrom, & Taebel, "Cumulative Voting in a

Municipal Election: A Note on Voter Reactions and

Electoral Consequences," 43 Western Pol. Q. 191-99 (1990)

......................................................... 11

Engstrom and Barrilleaux, " Native Americans and

Cumulative Voting: The Si sseton-Wahpeton Sioux," 72

Social Sci. 0. 387-93 (1991)........................... 1 1

Engstrom and McDonald, "Definitions, Measurements and

Statistics: Weeding Wildgen's Thicket," 20 Urban Lawyer

175 (1988) ............................................. 10

McDonald, Binford & Johnson, "The Impact of the Voting

Rights Act in Georgia" (forthcoming) ............ 46

* 1 i-f- ■iviiu £*\\LL

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION

This Court's jurisdiction is based upon 28 U.S.C. 1291. This

appeal is from the final decision of the district court dismissing

a complaint alleging violations of Section 2 of the Voting Rights

Act and the Constitution.

x

iiiniitiiiiiiHiii

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES

1. Whether the district court erred as a matter of law by

refusing to consider evidence other than that drawn from prior

elections, such as socio-economic or other. barriers to voting and

political participation, the history of segregation, racial

campaign appeals, and the testimony of experienced local politi

cians, in holding that plaintiffs' failed to prove that voting in

Bleckley County, Georgia was racially polarized?

2. Whether the district court was clearly erroneous in

finding that plaintiffs failed to prove the existence of racially

polarized voting?

3. Whether the district court erred as a matter of law in

holding that plaintiffs failed to prove that the black community

was politically cohesive because election returns did not show "a

pattern of bloc voting" or "a pattern of unified support" for black

candidates, and by failing to consider other evidence of cohesive

ness, such as a distinctive socio-economic status and a history of

segregation and discriminatory treatment of the black community?

4. Whether the district court was clearly erroneous in

holding that plaintiffs failed to prove that the black community

was politically cohesive?

5. Whether the district court erred as a matter of law in

holding that the issue of whether the majority vote requirement for

the Bleckley County Commissioner had a discriminatory purpose or

effect was not properly before the court because (a) the majority

vote statute was a part of state law which the county lacked power

1

to change, and (b) the claim that the majority vote statute

violated the Voting Rights Act was the subject of pending litiga

tion in another district?

6. Whether the district court erred as a matter of law in

holding that plaintiffs failed to produce "any evidence" that the

at-large elected, sole commissioner form of government was adopted

or was being maintained with a racially discriminatory purpose

because they failed to present specific, smoking gun evidence, and

in refusing to consider circumstantial evidence of racial purpose?

7. Whether the district court was clearly erroneous in

finding that the at-large elected, sole commissioner form of

government was not adopted or being maintained with a racially

discriminatory purpose?

8. Whether the district court erred in concluding that black

voters were not denied the equal opportunity to participate in the

political process and elect candidates of their choice by the at-

large elected, sole commissioner form of government in violation of

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Course of Proceedings and Disposition in the Court Below

This is a voting rights case filed on July 17, 1985 by black

residents and voters of Bleckley County, Georgia and the NAACP

Chapter of Cochran/Bleckley County. The plaintiffs-appellants

contended that the at-large elected, sole commissioner form of

county government had a racially discriminatory purpose and effect

and resulted in the dilution of their voting strength in violation

2

of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. 1973, and the

Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments.^ The defendants-appellees

are the county commissioner and the superintendent of elections of

Bleckley County. A trial was held on December 4-7, 1989, and the

district court held for the defendants on March 7, 1991.

The district court held that plaintiffs failed to prove that

voting was racially polarized, that minority voters were political

ly cohesive, or that their voting strength was diluted by the at-

large elected, sole commissioner system in violation of Section 2.

The court refused to consider whether a majority vote requirement

for election of the commissioner had a discriminatory purpose or

effect because the requirement was part of state law which the

court held the county was powerless to change, and because

litigation concerning whether or not the law violated the Voting

Rights Act throughout the state was pending in another case in

federal district court, Brooks v. Miller, Civ. No. 1:90-CV-1001-RCF

(N.D.Ga.). The court dismissed plaintiffs' claim that the

challenged method of elections had been adopted or was being

maintained with a discriminatory purpose on the ground that there

was no specific evidence of racial intent.

Plaintiffs filed their notice of appeal on April 3, 1991.

Statement of Facts

Bleckley County is in rural Georgia and has 219 square miles.

^The plaintiffs also challenged the district voting plan for

the Bleckley County Board of Education and the method of electing

the Cochran City Council. These claims were settled by consent of

the parties on November 22, 1985 and July 17, 1986, and are not

involved in this appeal.

3

It was established in 1912 and has a sole commissioner form of

government. The sole commissioner, pursuant to general state law,

exercises all the powers and duties of the governing authority of

the county.* 2 A declining number, fewer than 20, of the 159

counties in the state still retain the sole commissioner system.2

The commissioner is elected from the county at-large, and a

majority vote requirement is in effect. According to the 1980

Census, Bleckley County has a population of 10,767 people, of whom

2,367 (22%) are black.4 No black has ever been elected to, or

held, the office of county commissioner.

A. Racially Polarized Voting

Plaintiffs' evidence of polarized voting consisted of the

testimony of experienced local politicians; the consistent defeat

of minority candidates; the history of racial discrimination,

particularly discrimination in the conduct of elections, and its

continuing effects; few minority elected officials; the depressed

2The commissioner's duties include construction and mainte

nance of roads and bridges, setting the tax millage rate, serving

on boards and author ities, Tiiring and firing county employees, and

managing the every day operations of the county. R5-495-97, 548.

2Sole commissioner systems were abolished in Carroll, Telfair

and Webster Counties as a result of Section 2 litigation.

Carrollton Branch NAACP v. Stallings, 829 F.2d 1547 (11th Cir.

1987); Clark v. Telfair County, Georgia Commission, Civ. No. 287-25

(S.D.Ga. Oct. 26, 1988); Nealy v. Webster County, Georgia, Civ. No.

88-203 (M.D.Ga. March 16, 1990). Similar challenges are pending in

Pulaski and Wheeler. Sutton v. Anderson, Civ. No. 89-58-1

(M.D.Ga.); Howard v. Commissioner of Wheeler County, Georgia, Civ.

No. 390-057 (S.D.Ga.).

^The 1990 Census shows a slight decline in the total popula

tion (to 10,430), and a slight increase in the percentage of black

population (to 2332) .

4

> - - o’ .i££&iijbn£-̂ £i*

level of black candidacies for at-large elected, county wide

offices; the increased level, and success, of black candidates in

non or less dilutive election systems utilizing majority black

districts (board of education and city council), and in elections

with no majority vote requirement (city council); an exit poll; and

statistical analysis and testimony by expert witnesses.

(1) The Testimony of Experienced Local Politicians

Experienced local black politicians were unanimous in their

testimony that voting in Bleckley County was racially polarized.

According to plaintiff Roberson, who has lived in Bleckley County

since 1955 and who was elected to the Cochran City Council from a

majority black (71X) district in 1986, "having had the experience

that I've had, I know that the white voters will not vote for a

black candidate." R3-85. In his opinion, no more than 10% of

whites, "if that many," would cross over and vote for a black in a

contested election for the sole commissioner position. R3-84.

Mattie McDonald, a retired black school teacher and an

unsuccessful candidate for an at-large position on the Cochran City

Council in 1982, testified that no black, however well qualified,

could expect to win an election for commissioner because of severe

white bloc voting. R4-282. The number of whites who would be

willing to vote for a black "would be very low." R4-283.

Willie Basby, a local black business man and a member of the

Cochran City Council, testified that he did not think he could win

a county wide election for commissioner. R4-309. A black

candidate would "have to make sure he could get all the black

5

voters and a percentage of the whites and they're not going to --

that's not going to work. I just don't believe that would work."

R4-314. In his opinion, "[t]here would be a very small percentage

[of white cross over votes], I would say maybe -- probably 101."

R4-315. Plaintiff Walker, the president of the NAACP and a three

time unsuccessful candidate for the Cochran City Council, testified

that whites would not support black candidates. R4-347-48.

(2) The Depressed Level of Minority Candidacies

Because of their belief that voting is racially polarized and

that they could not win enough white votes to obtain a majority,

few blacks have run for county wide office. As plaintiff Walker

explained, "it'd be a waste of money." R4-332. Plaintiff

Roberson agreed that "if you know the trend and you know that

you're going to lose, there's no sense in trying." R3-104. A

black candidate "hasn't got a chance, if he run[s] overall." R3-

110 .

The district court found that blacks had been deterred and

hindered from running for office because of their depressed socio

economic status. According to the court:

The depressed socio-economic status of black

residents, including particularly the lack of

public or private transportation, telephones

and self-employment, hinders the ability of

and deters black residents of Bleckley County

from running for public office, voting and

otherwise participating in the political

process. R2-59-5-6

Plaintiffs' expert Dr. Richard Engstrom, a political scientist

and an authority in the field of minority political participation,

testified that the at-large commissioner system, in the context of

6

a majority vote rule, the history of discrimination in the county,

the serious socio-economic disparities in the black community, and

continuing segregation, has a "chilling effect on black political

participation and "filter[s] out black candidates. R4-425-26.

No black has ever run for sheriff, clerk of court, tax

commissioner, justice of the peace, county commissioner, or for the

state legislature. R4-274-75 The only black to run for an at-

large, county wide position was plaintiff Hall. He ran for judge

of probate court in 1984 and was defeated, getting only 15% of the

total vote. R6-688 Blacks were 13.5% of the actual voters in the

election. R6-706.

(3) Success of Blacks in Non or Less Dilutive Systems

A black was elected to the county board of education in 1986,

but only after it adopted single member districts pursuant to a

referendum in 1982. R4-446-47. At the first election held under

the new plan, plaintiff Hall was elected from a majority (66%)

black district. Hall is the only black to hold any of the county's

fourteen elective offices. R5-521.

Blacks have been successful in elections for the Cochran City

Council as a result of its plurality vote rule, and because of the

adoption of district voting in 1986 as a result of this law suit.5

According to the 1980 Census, Cochran has a population of 5,121

people, of whom 1,704 (33%) are black. Cochran contains about half

(48%) of the total population of Bleckley County, and has a greater

^Under the new plan the city is divided into three districts,

with two council members elected from each district. One of the

districts is 71% black, and the other two are majority white.

7

percent of blacks than the county.6

Prior to the adoption of district elections, eight blacks had

run for the city council. Four had run for the council more than

once, and one had also run for mayor. All the blacks were defeated

except Willie Basby who was elected in 1973 by a plurality of the

votes in a contest against two whites.7

After the adoption of district voting, plaintiff Roberson ran

for city council in 1986 against a white in the majority black

(71%) district and won, receiving 84% of the vote. R3-53, 87. He

was re-elected in 1988 without opposition. R3-54.

Basby first ran for city council in 1972, and was defeated.

Prior to that time, running for office "was something you [blacks]

just didn't do." R4-319. Elections for the mayor and city council

had always been conducted on a plurality vote basis. After Basby

announced his candidacy, the city amended its charter to require a

majority vote for election. The legislature enacted a majority

vote requirement for the city later that year, but it was objected

to by the Attorney General in 1973 under Section 5 of the Voting

Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. 1973c.

Basby ran again in the 1973 election held after the Attorney

General's Section 5 objection. He had two white opponents, neither

^According to the 1990 Census, the population of Cochran is

4,390, of whom 1,651 (38%) are black.

^Plaintiff Walker ran for the council in 1979, 1980, and 1982.

R4-328. Plaintiffs Harris and Howard ran for the council in 1976.

Hosea Lee Blackshear, a black, ran in 1977, and plaintiff Hall ran

the next year. Henry Pitts, a black, ran for the council in 1978

and for mayor in 1980. Mattie McDonald ran for the council in

1982,.and plaintiff Harris ran for the council again in 1984.

8

of whom was an incumbent, and this time was elected with a

plurality (39%) of the votes. R3-148-49, R4-303-06, R5-642-45. At

the next election in 1975, Basby was opposed by a lone white and

was defeated. Basby was reelected in 1977 and has held office ever

since. He was opposed in 1979, but subsequently has run as the

incumbent without opposition. Since 1987 he has represented the

majority black district. No black has ever been elected mayor or

from a majority white district to the city council.

Basby runs a shoe repair shop in Cochran, a business he bought

from a white resident in the late 1960's. Approximately 901 of his

customers are white. He is the only black business person in the

county with such a large white clientele, a fact which gives him

unique personal contact with the white community and provides a

political advantages which other blacks in the county do not have.

(4) Statistical Analysis

The facts of this case limit the usefulness of extreme case

(or homogeneous precinct) analysis and regression analysis,

statistical methods for proving racial bloc voting approved by the

Supreme Court in Thornburg v. Gingles. 478 U.S. 30, 52-3 (1986),

and used by this Court in numerous cases. See, e . g ■ Carrollton

Branch of NAACP v. Stallings. 829 F.2d 1547 (11th Cir. 1987). This

is so because of the small number of black candidates for county

offices, and because in August, 1984 (the year in which plaintiff

Hall ran for judge of probate court) the county changed from using

eight precincts or polling places to using a single polling place

9

for the entire county.8 However, regression analysis can be done

for the 1984 Democratic presidential preference primary in which

Rev. Jesse Jackson was a candidate and in which voters were

presented with a racial choice.

Dr. Engstrom estimated on the basis of regression and

homogeneous precinct analysis of the 1984 primary that whites in

Bleckley County voted exclusively for white candidates at the rate

of 99.1%. Blacks voted for Jackson-at the rate of 60.8%. These

estimates were almost identical to the CBS News/New York Times exit

poll for Georgia which estimated that Jackson got 61% of black

votes and 1% of white votes statewide. R2-59-33 . In the five

homogeneous white precincts (those that were 90% or more white),

Jackson could have received at most only 3.4% of the white vote.

According to Dr. Engstrom, racial polarization occurred in the

election, and the likelihood of such results occurring by chance

was 1 in 10,000. R4-422, 430.

(5) The Exit Poll

Plaintiffs conducted an exit poll in connection with the 1988

^Homogeneous precinct analysis estimates voting behavior by

examining voting patterns in precincts predominantly of one race.

Whe^e there is only one precinct, it is impossible to do homoge

neous precinct analysis. Regression analysis compares the race of

voters in each precinct with the votes candidates of different

races received in those precincts. Regression analysis allows one

to estimate the percentages of white and black voters who voted for

candidates of their own race. Since regression analysis requires

multiple data points, or precinct voting totals, the existence of

only one precinct also precludes regression analysis. R4-414-21,

430. For a more detailed discussion of homogeneous precinct and

regression analysis, see Jackson v. Edgefield County, South

Carolina School District, 650 F.Supp. 1176, 1194-96 (D.S.C. 1986),

and Engstrom & McDonald, "Definitions, Measurements, and Statis

tics: Weeding Wildgen's Thicket," 20 Urban Lawyer 175 (1988).

10

Democratic preference primary in which Rev. Jackson was again a

candidate to determine the existence of racially polarized voting.

Dr. Alex Willingham, a political scientist at Williams College and

an expert witness in prior voting cases, including Rogers v. Lodge,

458 U.S. 613 (1982), designed the exit poll, which was conducted by

an associate. Voters were asked to mark a sample primary ballot

after they left the polls indicating how they had voted, and to

answer a brief questionnaire about their race, sex, age and whether

they believed voting in the county was racially polarized. The

pollsters attempted to distribute the sample ballots to as many

voters as they could. Participation in the poll was voluntary,

however, and 993 voters (39% of the total of all voters) respond

ed .9 The poll showed that Jackson got more than 90% of the black

vote (a substantially higher percent than he received in the 1984

primary), but a very small percentage - less than 2% - of the white

vote. Both Dr. Willingham and Dr. Engstrom were of the opinion

that the exit poll revealed a substantial level of racially

polarized voting in Bleckley County. R4-423.

^Random sampling of voters is not required in exit polls;

indeed, it is problematic, because in exit polls one cannot

randomly sample replacements for respondent!; who refuse to

participate. In a small jurisdiction, such as Bleckley County, it

is standard practice to attempt to poll all voters in the election.

As a practical matter it is impossible to get a 100% response rate,

but the level of response in. this case (39%) was excellent and was

actually higher than that in other polls published in social

science journals and relied upon by experts in the field. See,

e.g., Cole, Engstrom & Taebel, "Cumulative Voting in a Municipal

Election: A Note on Voter Reactions and Electoral Consequences," 43

Western Pol. Q. 191-99 (1990)(response rate of 33.2%); Engstrom &

Barrilleaux, "Native Americans and Cumulative Voting: The Sisseton-

Wahpeton Sioux," 72 Social Sci. Q. 387-93 (1991)(32.3% response

rate).

11

(6) Other Elections

Plaintiffs also put in evidence of other elections in which

residents of the county voted, and in which voters were either

given a racial choice among candidates or in which race was a

significant issue, to examine the existence or not of racial bloc

voting. One of those elections was the 1974 Democratic primary for

lieutenant governor in which J. B. Stoner, a self styled white

supremacist, was a candidate. Stoner finished second in a field of

ten candidates getting 20% of the total vote in Bleckley County.

He missed being the top vote getter by only 35 votes. Statewide,

Stoner got only 9% of the votes. The defendants' expert agreed

that Stoner's showing was evidence of racial polarization in

Bleckley County. R5-649.

In the same 1974 primary election, Lester Maddox, a candidate

for governor and an avowed racist, led a field of ten candidates

getting 44% of the total vote in Bleckley County. In the 1966

general election for governor Maddox out polled Republican Howard

"Bo" Callaway in Bleckley County getting 69% of the vote.

In the 1968 presidential election, George C. Wallace, an

independent candidate and a strong advocate of racial segregation,

carried Bleckley County. The Cochran Journal wrote that the county

"went almost solid for George Wallace as expected."^

l^The court discounted defendants' evidence of four statewide

elections which involved minor black candidates who received little

support from either black or white voters (C. B. King for governor

in 1970, Hosea Williams for United States senator in_1972, Mildred

Glover for lieutenant governor in 1982, and Otis Smith for public

service commissioner in 1988) as "simply a nullity." R2-59-39 The

court, in conformity with Carrollton Branch of NAACP v. Stallings,

12

Based upon his examination of the election data and other

factors, Dr. Engstrom was of the opinion that voting in Bleckley

County was racially polarized, and that a black preferred candidate

would not have a reasonable chance of winning an election for the

commission. R4-426-27. Dr. Peyton McCrary, a southern historian

and another of plaintiffs' experts, agreed that the sole commis

sioner form "closes off the possibility of black representation.

R3-213.

Dr. Willingham concluded, based upon his examination of the

evidence and interviews with black residents of the county, that

blacks are still largely excluded from decisionmaking at the county

level. R4-373. There is a high degree of racial polarization in

the county, and in areas of life where federal intervention has not

compelled desegregation, barriers to black participation remain.

R4-378. He was of the opinion that the extent of racial polariza

tion in Bleckley County makes it highly unlikely that a black

candidate would ever be elected to the commission because s/he

would be unlikely to receive a sufficient number of white votes to

gain a majority. R4-381.

B. Discrimination against Blacks in Bleckley County

(1) The Public Policy

Discrimination against blacks in Bleckley County in all areas

supra, 829 F.2d at 1558-59, similarly placed no reliance on

defendants* evidence of the 1984 re-election of Justice ̂ Robert

Benham, a black member of the state court of appeals, which the

district court found was "a unique situation" involving an

incumbent member of the judiciary. Judicial elections generate

very little voter interest and incumbents, such as Benham, are

routinely re-elected. R4-443.

13

■ I

«

1

of life has been gross and systematic. As the district court

found, prior to the intervention of Congress and passage of the

modern civil rights acts, "Bleckley County... enforced racial

segregation in all aspects of local government -- courthouse [water

fountains, bathrooms, seating], jails, public housing, governmental

services [including recreational facilities] -- and deprived its

black citizens of the opportunity to participate in local govern

ment." R2-59-4. R3-60-1, 64.

The maintenance of segregation in all its forms was a major

topic of debate into the mid to late 1960's, and " [ c ]andidates for

public office during those years appealed for voter support by

promising to oppose desegregation." R2-59-4-5. In 1960, Bleckley

County representative Ben Jessup took out a political ad addressed

"To the White Voters of Bleckley County,” promising to vote for the

continuation of racial segregation and the county unit system.

P.Exh. 20. Mr. Jessup represented Bleckley County in the legisla

ture for over 25 years. Today he is a member of the Cochran City

Council and is Doorkeeper of the Georgia House of Representatives.

James M. Dykes in his campaign for the Georgia Senate in 1960

pledged to maintain segregated schools throughout the state. R3-

138. In his political ads, he promised to maintain white suprema

cy, the all white primary and the county unit system. P.Exh. 74.

Public accommodations, such as restaurants, movie theaters and

motels, were racially segregated. R3-66-7. Even the bookmobile

was Jim Crow. P.Exh. 56 Prior to passage of the Civil Rights Act

1A

of 1964, Cochran operated a swimming'pool for whites only. After

passage of the Ac-t, the city closed the pool and covered it over

with bricks. R3-64. The cemetery owned and maintained by the city

is still operated on a racially segregated basis. R3-65.

Public housing was built on a racially segregated basis.

Although it is no longer segregated by law, Happy Hill Homes, which

was built in the 1950's as an all black project, has never had a

white resident. R3-68.

The segregated public school facilities that were available to

blacks during the 1950's and '60's were so grossly unequal that the

state board of education took action to terminate state funds to

schools in Bleckley County. R3-137. As reported in the Cochran

Journal, "the Negro schools...have been condemned for several

years." P.Exh. 244. The county school superintendent's response

was that "as far as I know, they [blacks] are perfectly contented

with what they have got." The superintendent reported in 1957 that

40% of the black students in the county between the ages of 6 and

16 were not attending school. P.Exh. 57.

Bleckley County sought to avoid desegregation through a series

of stratagems, including building a new "equal" school for blacks

in 1963, P.Exh. 245, 21, and operating schools on a freedom of

choice basis in 1965. P.Exh. 258-59. According to the board of

education, "enforced racial integration of school students...[was ]

morally and socially wrong." P.Exh. 260. Schools were not

desegregated until 1970, and only after HEW notified the county

that its federal funds were being terminated. P.Exh. 274.

The superintendent of schools acknowledged in 1982 that de

facto segregation continued to exist in the county schools. P .Exh.

189. Although the public school system is 30% black, in 1989 there

were only five blacks in teaching or administrative positions, one

at the county high school, one at the middle school and three at

the elementary school. R4-269, 299, R5-482-92.

Prior to consolidation in 1977, there were two school systems

in Bleckley County, a county system operated by a board of

education appointed by the grand jury, and a city system in Cochran

operated by a board elected at-large. R4-273-74. Although

consolidation, which retained the grand jury method of appointing

members to the board, was a change in voting it was never submitted

for preclearance under Section 5. R3-155. Both before and after

consolidation, no black was ever appointed to the board of

education by the grand jury.^ R4-273-74. No black ever ran

for, or served on, the board of education of the city schools. Id.

No black served on the county board until single member districts

were adopted in 1982. R4-275, 445-46.

(2) The Private Sector

Churches, civic clubs, private social groups and housing in

Bleckley County are racially segregated. R2-59-6. R3-70, 76. In

llThe failure to appoint blacks is not surprising in view of

the systematic exclusion of blacks from the grand jury. Although

blacks according to the 1980 census were 19% of those 18 years of

age or older and presumptively eligible for jury duty, for six

randomly selected terms of court during 1960-1966, blacks comprised

only 3.7% of those summoned as grand jurors. R3-28-9. For five

randomly selected terms of court during 1973-1979, blacks comprised

only 9.5% of grand jurors. R3-29.

16

the early 1980's Samuel Moore, a black employee of the Georgia

Power Company, contracted to buy a home in an all white neighbor

hood in Cochran. Whites living in the neighborhood asked plaintiff

Roberson to convince Moore not to go through with the purchase.

Moore eventually decided not to buy the house because of the

opposition by whites to his living in their neighborhood. R3-69-

70, R4-277.

News was reported in the Cochran Journal on a racially

segregated basis. P.Exh. 43,44, 59, 116, 131, 252. The Bleckley

County Sportsman Club, of which defendant Holder is a member, has

never had a black member. R5-537. The Cochran Rotary Club is all

white. R3-73. The Masons and Eastern Stars are racially segregat

ed. R3-73. The Woodmen of the World chapter in Bleckley County is

all white, as are the Jaycees and the Cochran Pilots Club, a

professional women's organization. R3-75-6, R5-585, 622.

Racial attitudes, amounting at times to negrophobia, have

permeated life in Bleckley County. Cross burnings and klan rallies

took place in the county during the 1940's and 1950's. R5-572, R3-

72-3, P.Exh. 120-21. One of the cross burnings was in plaintiff

Roberson's yard in 1956, the year after he had tried to register to

vote. R3-73.

The Cochran Journal attacked the 1954 Brown decision and said

that Justice Black had accepted an award from a communist front

organization. The £>aper criticized President Eisenhower in 1958

for sending troops to Little Rock and "his policy of appeasement of

minority groups." P.Exh. 83, 125. In 1960 the paper applauded

17

Senator Herman Talmadge for his opposition to civil rights

legislation, especially voting rights legislation. P.Exh. 86 The

paper frequently attacked the Civil Rights Act of 1964. P.Exh. 89-

97. In 1963 the paper criticized the Georgia Board of Regents for

allowing Georgia Tech to play home games against racially integrat

ed teams. The regents were accused of "giving in” to integration,

which the paper said was "unchristian." P.Exh. 76.

C . Discrimination in the Political Process

Discrimination against blacks in the political process has

been particularly rigorous and draconian.

(1) Voter Registration

As the district court found, prior to passage of the Voting

Rights Act of 1965, "black citizens were virtually prohibited from

registering to vote in Bleckley County." R2-59-6. Disfranchise

ment was accomplished by the use of discriminatory literacy tests,

the all white primary, and intimidation and threats of violence.

R4- 251-53. When the white primary was invalidated in King— v_̂

Chapman, 62 F.Supp. 639 (M.D.Ga. 1945), Representative Dykes

announced that forms had been prepared to use in challenging every

black registered voter "to safeguard our Democratic White Primary.

The challenges were successful. P.Exh. 33.

In 1946, Lewis Carswell, a black World War II veteran, and

several other blacks attempted to vote at the segregated Thompson

Street school. There were no voting materials at the precinct, <

however, and the sheriff came by and said, "y'all niggers go around

to the back of the Courthouse. We’re going to let y'all vote

18

around there." R4-255. The blacks went to the courthouse but were

confronted by a group of 20-30 armed whites, who used physical

force to prohibit them from entering. All the blacks left and none

cast any ballots. Carswell did not attempt to vote again until the

Johnson/Goldwater presidential election in 1964 because he felt "it

would've been impossible." R4-257.

Two years after the Carswell incident the Cochran Journal, in

reporting on the 1948 election, noted that: "It is interesting to

not (sic) that there were no Negro votes cast in the entire county.

No Negroes appeared to vote and little if any interest was shown by

them in the election." P.Exh. 5. In fact, one black, Ralph Allen,

a retainer at a white hunting lodge frequented by local white

politicians, was allowed to vote. Allen explained that he was

different from other blacks, "because I try to make sure that my

personality and everything be different from anybody else's." R5-

570-71. Allen is employed by the county as a bailiff and testified

that in all his years of living in Bleckley County he never saw

anything that he thought was racial discrimination-; R5-576.

Plaintiff Roberson first tried to register to vote in Bleckley

County in 1955 when he moved there to teach in the city schools.

R3-51, 55. He went to the courthouse and after he entered, the

Cochran chief of police took him outside and told him that "no

niggers register in this courthouse." R3-55. Roberson complained

about the incident to his school superintendent, but the superin

tendent told him, "just don't push the issue." R3-57. Roberson,

who didn't want to lose his job, did not try to register again

19

until 1964. R3-58. A black teacher who ignored similar advice

from the superintendent and who registered in 1958 was not rehired

as a teacher the following year. R3-59-60. As late as 1962,

voting by blacks in Bleckley County was virtually non-existent.

R4-267.

At the time the Voting Rights Act was passed in 1965, 3,346

whites (741 of the voting age population) were registered, but only

45 blacks (31 of the voting age population). Black voter registra

tion did not increase significantly until 1984 when satellite

registration was allowed in the black community away from the

courthouse. R3-110, R4-279-80, 335-36. Some of those who

registered at the sites in the black community said that they had

been afraid to register before. R4-338.

(2) Registrars and Poll Workers

Despite passage of the Voting Rights Act, systematic discrimi

nation against blacks in the conduct of elections continued into

the late 1980's. No blacks were appointed as deputy registrar

until 1984, and only after blacks complained to the Georgia

secretary of state's office. R4-337. Prior to their complaints,

blacks had asked the chief registrar to appoint blacks, but he said

"he didn't know about it." R4-337. p. 7. No black served on the

county board of registrars until 1985. R4-277-78.

From 1978 to 1986, the defendant superintendent of county

elections appointed 224 poll managers for some 17 elections, and

not a single one was black. R2-59-7. He also appointed 509 poll

clerks, and only 30 (6%) were black. Although blacks had requested

20

to be allowed to work at the polls, they were told by the superin

tendent of elections that "we're already filled up," R.4-329, or

"we can't use you at this time." R4-331.12 An election system

largely run by whites, particularly in view of the rich history of

discrimination in Bleckley County, can serve to intimidate black

voters. R3-152.

D . The Depressed Socio-Economic Status of Blacks

As the district court found, the 1980 Census and the testimony

of Drs. Willingham and Engstrom "show conclusively" that blacks in

Bleckley County continue to endure a depressed socio-economic

status, and that such status hinders their ability to participate

effectively in the political process:

(1) 50% of the whites in Bleckley County have a high

school education while less than 15% of the blacks have

a high school education; (2) whites are more likely than

blacks to own automobiles and have telephones; (3) the

per capita income and median family income of whites is

double that of blacks; (4) while one-third of the blacks

live below the federally recognized poverty level, only

9% of the whites do. This depressed socio-economic

status hinders the ability of blacks to participate in

the Bleckley County political process because...(1)

better educated people are less threatened by having to

make choices and are more likely to understand the

importance of civic involvement; and (2) less educated

people are more difficult to mobilize to vote even if

they are registered to do so. R2-59-5

The court found that these "barriers to active participation

in the political process are today compounded by the fact that

Bleckley County now has only one voting precinct for the entire 219

11 2Blacks in Bleckley County have filed suit in federal court

challenging the discriminatory appointment of blacks as poll

managers and clerks. NAACP of Cochran/Bleckley County v. Bleckley

County, Civ. No. 88-32-MAC (M.D.Ga.).

21

square-mile area." R2-59-6. n.3. There is no public transporta

tion and it is difficult for poor blacks who lack private transpor

tation to get to the polls. R3-81. The polling place, known as

the Jaycee Barn, is owned by the Bleckley County Jaycees and serves

as its meeting place. R3-81. The Jaycees is an organization with

an all white membership, and for that reason many blacks are

reluctant to vote at all. R3-81-3.

E . The Difficulties in Campaigning

As the district court found, to be successful in Bleckley

County, a candidate has "to be known" by black and white voters.

R2-59-28, 39. Whites have little difficulty gaining access to the

black community, or being "known." Blacks, however, because of the

continuing effects of past discrimination and the existence of

racial polarization, find it very difficult to campaign effectively

in the white community.

In 1982 when Mattie McDonald ran for an at-large seat on the

city council, she received invitations to speak at black churches

but never any invitations to speak at white churches or organiza

tions. R4-276. White candidates, however, are regularly invited

to speak to black congregations. R3-112-13. According to

defendant Holder, door-to-door personal contact is absolutely

essential to a successful campaign in the county. R5-514.

McDonald did campaign door-to-door in the black community, but

because of doubts that she would be accepted she did not do the

same thing in the white community. R4-277.

When plaintiff Roberson ran for the city council in 1986,

22

R3-79. Heblacks, but not whites, publicly campaigned for him.

was never asked to speak at white civic or social organizations.

R3-79-80. Based upon his experience, the continuing segregation in

civic and private life of the county create substantial barriers to

the ability of blacks to participate effectively in the political

process. R3-81, 88, 90.

Plaintiff Walker got no public support or contributions from

whites during his campaigns for city council. R4-332. He spoke

before black, but not white, organizations. R4-333. He didn't

attempt to put his campaign cards in white businesses because I

didn't think they would be accepted." R4-334.

Council member Basby has been invited to speak at black clubs

and churches, but not to white organizations. R4-317-18. White

candidates have addressed the all white Rotary Club in Cochran, but

never any black candidates. R5-537.

In 1989, state senator Joseph Kennedy, as part of his campaign

for lieutenant governor, spoke at the Cochran Rotary Club.

Defendant Holder, a member of the club, had been asked previously

by one of Kennedy's aides to "get as many blacks together" as he

could in an effort to promote Kennedy's candidacy. R5-512. Rather

than inviting any blacks to the Rotary Club, Holder arranged for

Basby and Roberson, the two black elected members of the city

council, to meet with Kennedy separately at the public library.

R3-88-90, R4-307-09, R5-536. According to Roberson, being excluded

from places like the Rotary Club deprives blacks of a chance to

meet white voters and "be more positive in running their cam

23

paigns. R3-90. Basby agreed. R4-313.

Efforts to build a bi-racial political organization in

Bleckley County have been unsuccessful. The Concerned Citizens

Committee was established in Cochran several years ago by McDonald

and others to help improve local government. Both whites and

blacks participated initially, but the number of white participants

has declined. At the present time there is only one active white

member. .R4-286, 296.

F. Maintenance of the Sole Commissioner System and The

Ma ]or itv Vote Requirementt

The sole commissioner form of government is the most extreme

form of at-large elections. R3-132, 207. Coupled with a majority

vote requirement, and where voting is racially polarized, it

virtually assures that blacks are excluded from effective partici

pation in the political process.

Since the 1960's there have been efforts in Bleckley County to

adopt a multi-member board of commissioners. In 1972, the

Republican candidate for commissioner advocated bringing the issue

to a referendum vote. P.Exh. 303. In 1975 the grand jury recom

mended that a committee be established to study the feasibility of

a board of commissioners, P.Exh. 335, and in 1982, 1983 and 1985

the grand juries recommended that a referendum be held on whether

to change the sole commissioner system. P.Exh. 132, 207, 209. A

referendum was finally held on the question in 1986. There was

some organized effort in the black community in support of the

referendum, but it was defeated by a vote of 57% against to 43%

for. R4-320-21 . Defendant Holder, whose position was jeopardized

24

...... . " - ' - »• • -

by the referendum, actively campaigned against it. R5-540. He ran

newspaper and radio ads urging that the sole commissioner system be

maintained. R5-540.

The Bleckley County Democratic executive committee adopted a

majority vote requirement for county primary elections in 1964. P.

Ex. 250, R3 — 121—23. Prior to that time nomination was by a simple

plurality. R3-123. Political leaders in the county, such as

representative Jessup, Democratic Party chairman JameSs S. Dykes,

and mayor James M. Dykes, were knowledgeable and experienced

politicians. They were firmly committed to maintaining white

control and knew the likely racial impact of a majority vote

requirement for county offices. R3-129.

Later that same year, the general assembly enacted a law

requiring a majority vote for nomination or election to all state

and county offices. Representative Denmark Groover of Bibb County

was a principal sponsor of the majority vote law and said that it

was needed to thwart the recent increases in Negro voter registra

tion and to make it impossible for the black "bloc vote" to elect

a candidate to office by a plurality. P.Exh. 229-31.

During the time that the majority vote bill was being enacted,

the general assembly attempted in numerous other ways to dilute the

voting strength of blacks and ensure white dominance. House floor

leader Frank Twitty strongly supported legislation in 1962

requiring candidates to run at-large in counties with more than one

senatorial district for the reason that "district elections almost

inevitably would lead to the election of a Negro in one of Fulton

25

County's seven districts." P.Exh. 228. In 1964 the general

assembly reenacted the state's discriminatory literacy test

designed to make it more difficult for blacks to register and vote.

Dr. McCrary testified that in his opinion the majority vote

requirement was adopted, first by the Democratic executive

committee and then by the general assembly, for the racially

discriminatory purpose of ensuring that no matter how many blacks

registered to vote, the white majority would be able to control the

outcome of elections. R3-134, 142, 180-81.

G . Geographical Compactness

The district court found that "[t]here can be little dispute

that the black community is sufficiently geographically compact to

meet the Gingles standard." R2-59-45. If the county commission

were elected from five single member districts using the existing

configuration of the county board of education, one of the

districts would contain a majority of voting age blacks. p. 10.

H. The Decision of the District Court

The district court held that evidence of the existence of

racially polarized voting in Bleckley County "is simply unavail

able." R2-59-46 n. 48 It found that "[njothing in the plaintiffs'

evidence drawn from elections for local [municipal] office leads

this court to a conclusion that voting on local levels is racially

polarized." R2-59-28. As for the elections involving racial

issues or themes, the court found "this evidence simply falls short

of proving polarized voting." R2-59-39 According to the court,

"under prevailing law with regard to this stage of the court's

26

— TiZi 1 . . v ■» :: AVi .'— »!»• .'VAv ii'.u.ri ■ikS ' 'ii.'— .»Akih(>w.(a i ->». * \ £ . o i t * . ' , ® . .

evaluation, the evidence to which Dr. Engstrom referred [the 1984

regression analysis and the 1988 exit poll] is all the court has or

can have." R2-59-41 (emphasis in original). Based upon this

evidence, the court concluded that plaintiffs failed to demonstrate

a pattern of racial bloc voting.

The court also held that "plaintiffs may not rely upon socio

economic or other barriers as specific evidence that voting in the

community is racially polarized." R2-59-41. The court firmly

"reject[ed] plaintiffs' arguments that evidence other than that

drawn from previous elections, i.e. Bleckley County's history of

racial segregation, racial themes in public forums, etc., amounts

to evidence of racial bloc voting." R2-59-42 n.45.

Although the trial judge refused to look at any factors other

than election data in making his legal ruling on the issue of

polarized voting, he acknowledged in a colloquy with counsel at the

end of the trial that "[c ]ommonsense tells you something" about the

futility of a black running for office in Bleckley County. R6-807-

08. According to the judge:

Having run for public office myself, I'll guarantee you,

under the circumstances, I wouldn't run if I were black

in this county. You're going to put your hard-earned

time and shoe leather campaigning throughout this

county.... Mr. Basby is, as y'all said, an aberration.

R6-808.

Having found no polarized voting, the court found that

plaintiffs failed to prove that blacks were politically cohesive.

"This [pattern of bloc voting] is what Gingles requires, and this

court may require no less at this stage of its analysis.

Plaintiff's evidence simply fails to prove that Bleckley County's

27

black community is politically cohesive." R2-59-45. The court did

not consider any factors other than elections returns in making

this determination.

The court, having concluded that plaintiffs failed to meet

"two requisite preconditions to relief" set out by Thornburg v.

Gingles, supra, considered only "brief[ly]M the other factors

listed in the senate report that accompanied the 1982 amendment of

Section 2 that were probative of vote dilution, 13 such as the

socio-economic status of blacks, low black representation among

poll workers, the existence of a slating process, whether the

commission was responsive to black needs, and the policy underlying

the commission form of government, but concluded that the evidence

was not sufficient to support a Section 2 violation. R2-59-49.

The court dismissed plaintiffs' claim that the sole commis

sioner system had been adopted or was being maintained with a

discriminatory purpose on the ground that there was no "specific

evidence of racial intent. R2-59-20. The court refused to

consider whether the adoption of a majority vote requirement in

1964, as to which there was "specific evidence" of racial intent,

had made the sole commissioner system a more secure mechanism for

discrimination, because the requirement was a part of state law

which the county was powerless to change, and because litigation

concerning whether the majority vote law violated Section 2 was

pending in another case. R2-59-22. 13

13See, S.Rep. No. 147, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. 28-9 (1982).

28

THE STANDARD OF REVIEW

The standard of review is one of reviewing errors of law,

including the correction of findings of fact based on misconcep->

tions of the law. Concerned Citizens v. Hardee County Board of

Commissioners, 906 F.2d 524, 526 (11th Cir. 1990).

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

In applying the three part test for a violation of Section 2

set out in Thornburg v. Gingles, supra, and in holding that

plaintiffs failed to prove racial bloc voting, the district court

erred by refusing to consider evidence other than that drawn from

prior elections, by failing to give adequate- consideration to

evidence of prior elections and by relying almost exclusively on

the two elections which could be analyzed by quantitative tech

niques. Gingles and the precedents of this Court require a court

to consider factors other than elections where election data is

sparse or unavailable, both to determine the existence of racial

bloc voting as well as the denial of equal access to the political

process, e . g . , the testimony of experienced local politicians, the

history of discrimination, continuing segregation, socio-economic

conditions, and the difficulties minorities have in campaigning in

the white community. The court also failed adequately to consider

evidence of: few black candidacies or electoral successes in county

wide contests; black electoral successes in non or less dilutive

systems which used district voting and/or a plurality vote; and,

elections with racial themes or issues.

In holding that blacks were not politically cohesive, the

29

court erred in relying exclusively on election returns, by failing

to give adequate consideration to evidence#of prior elections and

in refusing to consider other relevant evidence, e . g . , that blacks

shared a common experience in past discriminatory practices, that

blacks had common social, economic and political interests, that

the black community supported religious, civic and political

organizations, and that blacks supported black candidates where

they had a realistic chance of winning.

The district court erred in refusing to consider whether the

majority vote requirement had a discriminatory purpose or effect.

The requirement was enacted by the general assembly in 1964 to

reshape at-large elections into more secure mechanisms for

discrimination wherever they existed in the state. Under the

circumstances, the at-large system in Bleckley County is the

product of intentional discrimination and violates Section 2.

Dillard v. Crenshaw County, 640 F.Supp. 1347 (M.D.Ala. 1986).

Brooks v. Miller , supra, a statewide challenge to the majority vote

requirement, was filed after the instant litigation and does not

take precedence over it.

The trial court failed to follow the analysis in Vi 11 age of

Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Development Corp., 429

U.S. 252 (1977), in refusing to consider circumstantial evidence of

intent, and in holding that plaintiffs failed to produce "any

evidence" that the sole commissioner form of government was

adopted, or was being maintained, with a racially discriminatory

purpose.

30

ARGUMENT AND CITATIONS OF AUTHORITY

I. The District Court Erred in Failing to Consider, or Give the

Required Weight to. Relevant Evidence of Polarized Voting

In Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30, 50-1 (1986), the Supreme

Court established a three part test for determining a violation of

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. 1973. The minority

must demonstrate that: (1) it is geographically compact, i. e . it

could constitute a majority in a single member district; (2) it is

politically cohesive; and, (3) whites vote as a bloc usually to

defeat the candidates supported by the minority.^ Bloc voting

was defined as "'a consistent relationship between [the] race of

the voter and the way in which the voter votes,1...or to put it

differently, where 'black voters and white voters vote different-

ly.'" Id. at 53 n.21. The Gingles analysis has been adopted and

applied by this Court in its voting cases. See, e . g . Carrollton

Branch of NAACP v. Stallings, 829 F.2d 1547, 1550 (11th Cir. 1987);

Solomon v. Liberty County, Florida, 899 F.2d 1012 (11th Cir.

1990)(en banc).

The district court found that blacks in Bleckley County were

geographically compact, but that plaintiffs failed to establish the

remaining two Gingles factors in that they failed to prove the

existence of polarized voting based solely upon evidence drawn from

prior elections. The court erred by refusing to consider other

relevant evidence, and by relying almost exclusively on the two

^According to the Court, the other factors listed in S.Rep.

No. 147, supra, "are supportive of, but not essential to, a

minority voter's claim." 478 U.S. at 48 n . 15 (emphasis in

original) .

31

'K.' J .M .

elections which could be.analyzed by quantitative techniques.

A - The Court’s Refusal to Consider All the Relevant Evidence

The district court refused to consider any evidence to prove

racial bloc voting other than election data. This was clear error

of law under Gingles and the precedents of this Court.

Gingles held that in some cases a minority group may never

have been able to sponsor a candidate. Under such circumstances,

"courts must rely on other factors [than elections] that tend to

prove unequal access to the electoral process." 478 U.S. at 57

n.25 (emphasis supplied). Moreover, where the minority has begun

I

just recently to sponsor candidates, "the fact that statistics from

only one or a few elections are available for examination does not

foreclose a vote dilution claim." Id. 15

The trial court believed it was prohibited from considering

| evidence other than election data by Gingles. supra, 478 U.S. at

63> and Collins v. City of Norfolk. 816 F.2d 932, 935 (4th Cir.

.

1987), which held that causation, or the reasons black and white

voters voted differently, was irrelevant to the determination ofI

j polarized voting. R2-59-40 Plaintiffs, however, did not

^Plaintiffs believe footnote 25 in Gingles means at least two

things: (1) racial bloc voting may be proved by factors other than

election data; and, (2) where racial bloc voting cannot be shown

because, for example, a system is so discriminatory that the

minority has never participated in elections as voters or candi

dates,^ or where^ the evidence is simply sparse, a Section 2

violation can still be established by proof that the minority is

denied equal^ access to the electoral process ’ based upon the

totality of circumstances identified in the legislative history of

Section 2. See, S.Rep. No. 417, supra, at 29. The evidence of

racial bloc voting in this case is strong, but quite apart from

that, the totality of circumstances clearly supports a violation of

the equal access standard' of Section 2 identified in footnote 25.

32

introduce evidence of socio-economic and other barriers to voting,

the history of discrimination, racial campaign appeals, the

testimony of experienced local politicians, etc. to show why voters

voted differently, only that they were in fact voting different

ly.^ Gingles is no bar to the consideration of such evidence

for that purpose, and it was error for the court to exclude it.

The Gingles requirement that a court look at other factors in

determining the existence of polarized voting, or access to the

electoral process, where election data -is sparse or unavailable is

simply a restatement of pre-existing voting rights case law. In

Nevett v. Sides, 571 F.2d 209, 223 (5th Cir. 1978), the court held

that:

Bloc voting may be indicated -,.by a showing...of the

'existence of past discrimination in general..., large

districts, majority vote requirements, anti-single shot

voting provisions and the lack of provision for at-large

candidates running from particular geographical subdis

tricts. 1 . . . Of course, bloc voting may be demonstrated by

more direct means as well, such as statistical analy

ses,... or the consistent lack of success of qualified

black candidates.

571 F.2d at 223 n.18 (citing Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297,

1305 (5th Cir. 1973) (en banc). • ‘

The Zimmer-Nevi tt method of proving polarized voting has been

consistently followed and approved by this Court. In United States

v. Marengo County Commission, 731 F .2d 1546, 1567 n.34 (11th Cir.

1984), for example, the Court held that in addition to direct

^The failure to establish a bi-racial political organization

in the county, for example, is evidence of general polarization in

the electorate and evidence that voting is likely polarized as

well. The evidence does not, however, tell us why the polarization

exists, nor was it introduced to do so.

33

statistical analysis "[w]e have stated that ’[b]loc voting may

[also] be indicated by a showing under Zimmer of...past discrimina

tion in general...or by 'the consistent lack of success of

qualified black candidates'." In Carrollton Branch of NAACP_v^

Stallings, supra, 829 F.2d at 1558, the Court held that polarized

voting can be established "through the clearly acceptable means of

a bivariate regression analysis and the testimony of lay witness

es." Other decisions are to the same effect. See, McDaniels— v^

Mehfoud, 702 F.Supp. 588, 593 (E.D.Va. 1988)("Racially polarized

voting can be established through both anecdotal evidence and

electoral analysis."); Windy Boy v. County of Big Horn, 647 F.Supp.

1002, 1013 (D.Mont. 1986)("The testimony of observers of Big Horn

County politics confirms that it is racially polarized. ); Sierra.

v. El Paso Independent School District, 591 F.Supp. 802, 807

(W.D.Tex. 1984) (racial bloc voting may be shown by "lay testimony

from...practical politicians who are thoroughly familiar with

voting behavior"); Gingles v. Edmisten, 590 F.Supp. 345, 367

(E.D.N.C. 1984), aff'd sub nom. Thornburg v. Gingles, supra.

One decision, Jackson v. Edgefield County,— South Carolina

School District, 650 F.Supp. 1176 (D.S.C. 1986), has even expressed

a preference for lay testimony over analysis of election data.

According to the court:

Even more persuasive to the Court than the experts

quantitative analysis of polarization on voting behavior

is the testimony by the local politicians who, through

their participation in the political processes, have the

direct observation and are familiar with the voting

practices and voting patterns in Edgefield County.

650 F.Supp. at 1198.

34

ĝ aatatateaa ■ ■ ■■■■*■ ■ m l MimmmAim i

V>. U.l«

In this case there was a substantial amount of evidence

showing the existence of polarized voting, other than evidence

drawn directly from elections, which the district court totally

ignored. That evidence included the testimony of experienced local

politicians that voting was polarized; a long history of discrimi

nation in the jurisdiction, particularly discrimination in

registering and voting; de facto segregation in housing, civic

organizations, churches and social clubs; racial campaign appeals;

the prevalence of strong racial attitudes in the county; the

depressed, and distinctive, socio-economic status of blacks; the

use of only one polling place (owned by an all white membership

organization); the difficulties black candidates have in gaining

access to the white community; and, the difficulty in establishing

a bi-racial political organization in Bleckley County. Gingles and

the decisions of this Court hold that such evidence is relevant and

must be considered, particularly where election data is sparse or

unavailable. It was error for the district court completely to

ignore it. 17

B . The Court's Reliance on Quantitative Analysis

In making its finding that voting was not polarized, the

district court relied almost exclusively on the 1984 and 1988

presidential primary elections, these being the only elections for

which quantitative analysis (i.e . regression analysis and an exit

poll respectively) could be done. R2-59-41. There was, however,

1 ‘ As noted supra, this evidence also proves "unequal access

to the electoral process" Gingles, supra, 478 U.S. at 57 n. 25.

35

\

i. e .substantial additional evidence from previous elections,

municipal and board of education elections in which blacks were

successful, and elections in which race was an issue. It was error

for the court to fail adequately to consider this evidence and

limit its review to statistical evidence of racial bloc voting.

In Lodge v, Buxton. 639 F.2d 1358 (5th Cir. 1981), aff'd sub

nom. Rogers v . Lodge. 458 U.S. 613 (1982), a challenge to the at-

large method of electing the Burke County Commission, there was no

regression analysis or survey data offered at all. The evidence of

polarized voting consisted entirely of: (1) one black candidate won

a majority of the votes in all four of the majority black precincts

in the county while losing in the others; (2) the only other black

candidate won a majority in three of the four majority black

precincts and lost in the others; (3) a white candidate who was

thought of as being sympathetic to black political interests was

soundly defeated; and (4) a black was elected in a recent city

council election in a district with a high percentage of black

residents. Lodge v. Buxton. Civ. No. 176-55 (S.D.Ga. Oct. 26,

1978), slip op. at 7-9. Based upon this evidence, the court of

appeals found "the evidence of...bloc voting was clear and

overwhelming." 639 F.2d at 1378. The court of appeals found "of

particular significance... the fact that in the one city election

in which city councilmen were elected from single-member districts,

a Black was elected." Id ■ The finding of polarized voting was

affirmed by the Supreme Court. Rogers v. Lodge, supra, 458 U.S. at

623.

36

Other courts have also noted the importance of black electoral

successes in single member or non-dilutive systems within the same

jurisdiction in determining polarized voting. In Jackson v.

Edgefield County, South Carolina, supra, the court found that black

successes in majority black districts for the county council were

evidence of racially polarized voting in a suit challenging at-

large elections for the county board of education. According to

the court, "[t]hese two recent County Council elections confirmed

the political unity of each racial group and the cohesiveness of

its voting behavior." 650 F.Supp. at 1198.

Similarly, in Cross v . Baxter. 604 F.2d 875, 880 n .8 (5th Cir.

1979), a challenge to at-large elections in Moultrie, Georgia, and

where regression analysis could not be done because of the limited

number of precincts, the court held that a finding of no polarized

voting by the trial court "would be clearly erroneous." The

evidence relied upon by the court of appeals included an analysis