Anderson v. Auseth,Brief of the Attorney General of the State of California as Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

September 4, 1946

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Anderson v. Auseth,Brief of the Attorney General of the State of California as Amicus Curiae, 1946. 0ed3dcbc-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1b30cef4-8ca0-4ecb-9799-aaa50bc7ab7c/anderson-v-auseth-brief-of-the-attorney-general-of-the-state-of-california-as-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

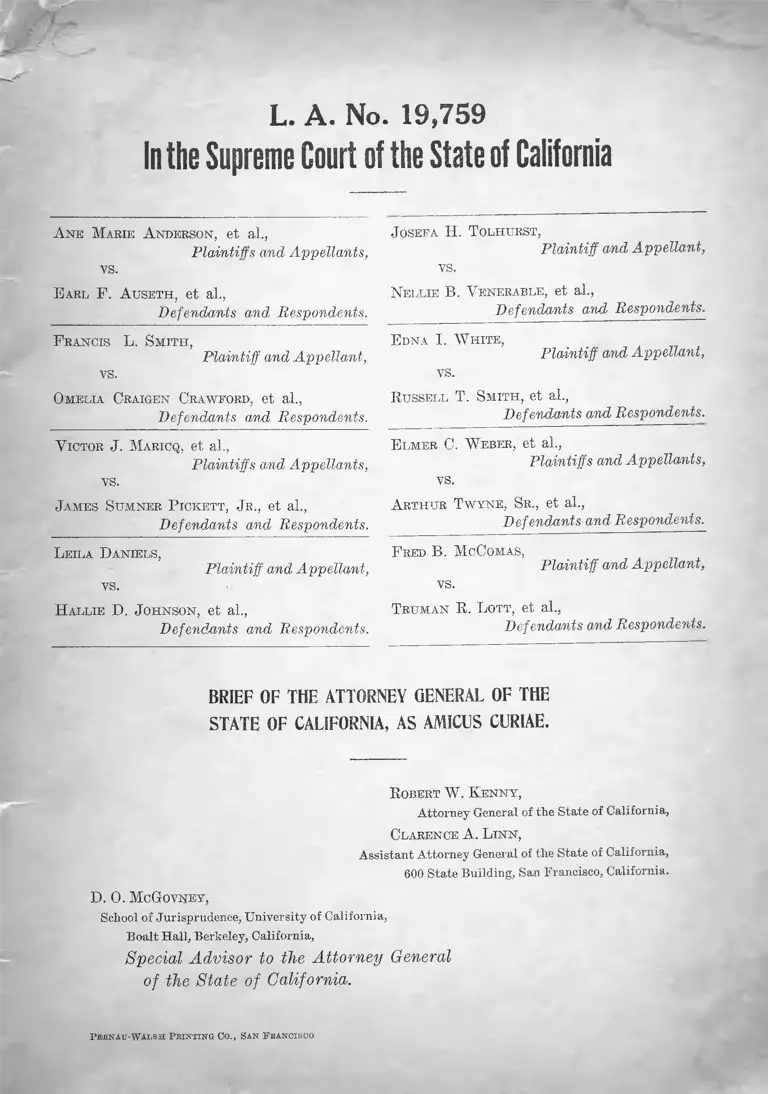

L. A. No. 19,759

In the Supreme Court of the State of California

A ne Marie A nderson, e t al.,

Plaintiffs and Appellants,

vs.

JOSEFA H. TOLHURST,

P lain tiff and A ppellan t,

vs.

E arl F. A useth , e t a l ,

D efendants and Respondents.

Nellie B. Venerable, et al.,

D efendants and Respondents.

F rancis L. Sm ith ,

P lain tiff and A ppellant,

vs.

E dna I. W h ite ,

P lain tiff and A ppellant,

VS.

Omelia Craigen Crawford, et al.,

D efendants and Respondents.

Russell T. Sm ith , et al.,

D efendants and Respondents.

V ictor J. Maricq, et al.,

P laintiffs and Appellants,

vs.

E lmer C. W eber, et al.,

Plaintiffs and Appellants,

vs.

J ames Sumner P ickett, J r ., et al.,

D efendants and Respondents.

A rthur T w yne, Sr ., e t al.,

D efendants and Respondents.

L eila Daniels,

P lain tiff and A ppellant,

vs.

F red B. M cComas,

P lain tiff and A ppellant,

vs.

H allie D. J ohnson, et al.,

D efendants and Respondents.

T ruman R. L ott, e t al.,

D efendants and Respondents.

BRIEF OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL OF THE

STATE OF CALIFORNIA, AS AMICUS CURIAE.

R obert W. K enny ,

Attorney General of the State of California,

Clarence A. L in n ,

Assistant Attorney General of the State of California,

600 State Building, San Francisco, California.

D. 0 . McGovney,

School of Jurisprudence, University of California,

Boalt Hall, Berkeley, California,

Special Advisor to the Attorney General

of the State of California,.

P ehnati-Wa l s h P e in t Ing Co., San F bancisco

Subject Index

Page

Foreword.......................................................................Preface

Argument ......................................................................... 1

The Contract Law Aspect............................................................ 3

The Property Law Aspect ......................................................... 5

State of the authorities on the constitutional issue in this case 11

(a) Supreme Court of California........................................... 11

(b) The United States Supreme Court decisions cited and

relied upon in the Gary case............................................. 12

(e) Decisions of other state courts......................................... 15

Corrigan v. Buckley ..................................................... 16

The United States Supreme Court’s decisions on the separate

factors involved in the present case......................................... 19

(1) Racial zoning by State statutory law............................. 19

(2) A state court’s decision giving effect to the State’s non-

statutory law is State action within the meaning of the

Fourteenth Amendment ................................................... 21

Conclusion ...................................................................................... 26

Table of Authorities Cited

Cases Pages

A. F. of L. v. Swing, 312 U. S. 321......................................... 22

Bailey v. Alabama, 219 U. S. 219............................................. 3

Bakery Drivers Local v. Wohl, 315 U. S. 760......................... 22

Bridges v. California, 314 U. S. 252..................................... 22

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60................................. 2,7,19,25

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296..................................... 22

Carter v. Texas, 177 U. S. 442................................................... 23

Chandler v. Zeigler, 88 Colo. 5, 291 Pac. 822........................ 16

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U. S. 3 ...................................................13,15

Corrigan v. Buckley, 271 U. S. 323.......................................... 15,16

Doherty v. Rice, 240 Wis. 389, 3 N. W. (2d) 734................. 15

Harmon v. Tyler, 273 U. S. 668................................................20,25

Janss Investment Co. v. Walden (1925), 196 Cal. 753.......... 12

Koehler v. Rowland, 275 Mo. 573, 205 S. W. 217.................. 8

Los Angeles Investment Co. v. Gary, 181 Cal. 680, 186 Pac.

596 ........................................................................ 8,10,11,12,14,15

Lyons v. Wallen, 191 Okla. 567, 133 P. (2d) 555.................. 6,15

McCabe v. Atchison, T. & S. F. R. Co., 235 U. S. 141.......... 26

Meade v. Dennistone, 173 Md. 295, 196 Atl. 330.................... 15,16

Missouri ex rel. Gaines, 305 U. S. 337..................................... 26

Mitchell v. United States, 313 U. S. 80............................... .. 26

Moore v. Dempsey, 261 U. S. 86............................................. 21

Morgan v. Commonwealth of Virginia, 66 S. Ct. 1050.......... 24

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U. S. 587............................................. 23

Parmalee v. Morris, 218 Mich. 625, 188 N. W. 330.............. 16

Porter v. Barrett, 233 Mich. 373, 206 N. W. 523.................. 16

Powell v. Alabama, 287 U. S. 45............................................. 21

Queensborough Land Co. v. Cazeaux, 136 La. 724, 67 So. 641 8,16

Ridgway v. Coburn, 163 Misc. 511, 296 N.Y.S. 936..............15,16

Rogers v. Alabama, 192 U. S. 226............................................. 23

T able op A u t h o r it ie s C ited iii

Pages

Slaughter-House cases, 16 Wall. 36......................................... 23

Thornhill v. ITerdt (Mo. App.), 130 S. W. (2d) 175.......... 15

Twining v. New Jersey, 211 U. S. 78..................................... 2,6,21

United Cooperative Realty Co. v. Hawkins, 269 Ky. 563, 108

S. W. (2d) 507........................................................................ 15

United States v. Cruikshank, 92 U. S. 542............................. 12

United States v. Harris, 106 U. S. 629................................... 14

Virginia v. Rives, 100 U. S. 313............................................... .. 13

Wayt v. Patee (1928), 205 Cal. 46............................................. 9

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356......................................... 23

Statutes

Civil Code, Section 711 ............................................................. 8

Civil Rights Bill of 1866, 14 Stat. 27..................................... 7,8

Civil Rights Bill, Section 18 of the Act of May 31, 1870, 16

Stat. 144 .............................................................................. 7,8.

Indian Contract Act, 1872 (codifying the English common

law) ............................................................................................ 4

United States Constitution:

Fifth Amendment .............................................................. 17,18

Thirteenth Amendment ....................................................... 7,17

Fourteenth Amendment .....................................................

................................. 2, 3, 6, 7, 8,14,17,18,19, 20, 21, 22, 25, 26

Eighteenth Amendment ..................................................... 3

Texts

33 Cal. L. Rev., p. 15.................................................................. 9

Corbin, Anson on Contracts, Sec. 9, note 2 ............................. 4

31 Harv. L. Rev., 479................................................................. 25

Los Angeles Daily Journal, June 14, 1945............................. 10

Pollack on Contracts (1885 and subsequent editions).......... 4

Restatement of the Law of Contracts, Sec. 1 ......................... 4

FOREWORD.

The Attorney General of the State of California respectfully

requests the permission of the Court to file this brief in the

above cases and to have the same considered in other companion

cases now under submission to this Court, as amicus curiae.

Although these actions are entitled as though they were be

tween private litigants this is not really the fact. Whole sec

tions of the population are to be affected by the outcome of

this litigation. Some persons of one race seek to fence in all

persons of another race and by agreement among themselves

have attempted to fix the bounds of the habitations of that other

race.

But this is not all. Some of the parties to the agreement,

either because of avarice or change of heart, have failed and

refused to live up to their agreement. The other parties to the

agreement now call into play all of the machinery of the State

for the purpose of giving effect to this agreement.

The State as 'a whole is interested in this matter. The aid

of its Courts, nisi prius and appellate, has been sought; its

clerks, sheriffs and constables have been called to issue and

serve writs which issue in the name of the People of the State

of California; ultimately (if the hopes of plaintiffs and appel

lants are realized) even the jails of the State may be called

upon to play a part in these actions.

Under such circumstances we do not feel that the legal arm

of the State should remain inactive.

When the State is called upon to take State action in its own

name against a large segment of its law-abiding citizens the

law officers of the State should be heard.

To this end we ask that this Court consider this brief.

L. A. No. 19,759

In the Supreme Court of the State of California

A ne Marie A nderson, et al.,

Plaintiffs and Appellants,

vs.

JOSEFA H. TOLHURST,

P lain tiff and A ppellant,

v s.

E arl F. A useth , e t al.,

D efendants and Respondents.

Nellie B. Venerable, et al.,

D efendants and Respondents.

F rancis L. Sm ith ,

Plaintiff and A ppellant,

vs.

E d n a I. W h i t e ,

P lain tiff and Appellant,

v s .

Omelia Craigen Crawford, et al.,

D efendants and Respondents.

B ussell T. Sm ith , e t al.,

D efendants and Respondents.

V ictor J. Maricq, e t al.,

Plaintiffs and Appellants,

vs.

E lmer C. W eber, et al.,

P laintiffs and Appellants,

v s.

J ames Sumner P ickett, J r ., et al.,

D efendants and Respondents.

A rthur T wyne, Sr ., e t al.,

D efendants and Respondents.

L eila Daniels,

P lain tiff and Appellant,

vs.

F red B. McComas,

P lain tiff and A ppellan t,

v s .

H allie D. J ohnson, et al.,

D efendants and Respondents.

Truman B. Lott, et al.,

D efendants and Respondents.

BRIEF OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL OF THE

STATE OF CALIFORNIA, AS AMICUS CURIAE.

ARGUMENT.

The Supreme Court of the United States holds that a

State in enacting a statute which attempts to set off

particular residential districts for occupation exclusively

2

by members of a particular race violates the Fourteenth

Amendment, Buchanan v. Warley, 245 IT.S. 60.

The question in this case is whether a law, not enacted

by the legislature, can exist and be enforced in a State,

under which residential districts for exclusive occupancv

by a particular race may be created, consistently with the

Fourteenth Amendment. Can the courts of a State by their

decisions make a law, or give effect as law to rules, which

its legislature is forbidden to enact 1 The framers and

adopters of the Fourteenth Amendment knew as well as

we do that the body of law in every State consists partly

of the law enacted by the legislature and partly of the

law which results from the decisions of its courts. Con

sequently the Fourteenth Amendment was drafted to

read “ No State shall” and the Supreme Court of the

United States has repeatedly held this to mean that no

State shall through action of any of its organs bring

about the results which the Amendment forbids. State

action of any kind producing a prohibited result is with

in the scope of the Fourteenth Amendment. In particular

the Supreme Court holds:

“ The judicial act of the highest court of the State,

in authoritatively construing and enforcing its laws,

is the act of the State.”

Twining v. New Jersey, 211 U.S. 78, 90.

On the other hand it is true that the Supreme Court

holds that the Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses

of the Fourteenth Amendment lay no restrictions upon the

purely private actions of unofficial persons, unsupported

by a State. The appellants contend that the result they

3

seek in this suit is solely a product of their private agree

ments. They pretend that that result may be recognized

by the Court as something already accomplished, and that

no State action of any kind is required, and this not

withstanding they have petitioned the Superior Court

to grant a decree ousting the respondents from their

homes, and now call upon this Court to recognize a state

of law in the State authorizing the Superior Court to

grant such a decree.

The lack of merit in this contention wrill be examined

in two aspects of these racial exclusionary agreements (1)

their contract law aspects (2) their property law aspects.

THE CONTRACT LAW ASPECT.

Not every agreement is a contract, which is the same

as saying, that not every agreement is enforceable by

courts. Some agreements are illegal by the common law

on grounds of public policy, and therefore unenforceable

by courts. By statutes others are declared unenforceable.

Some are rendered unenforceable by constitutional pro

visions. Peonage contracts are made unenforceable by the

Thirteenth Amendment. Bailey v. Alabama, 219 U.S. 219.

While the Eighteenth Amendment was in force all courts

in the United States were deprived of power to enforce

contracts for the sale of intoxicating liquors. The re

strictive agreement at issue, the respondents contend, is

unenforceable by a State court because the Fourteenth

Amendment deprives the State of power to enforce it by

action of its courts.

4

“ A contract is a promise or a set of promises for the

breach of which the law gives a remedy, or the perform

ance of which the law in some wav recognizes as a duty.”

Restatement of the Law of Contracts, § 1.

“ A briefer definition, of the same general purport, is,

‘a promise that is directly or indirectly enforceable at

law’.” Corbin, Anson on Contracts, §9, note 2.

“* * * a promise or set of promises which the law

ivill enforce.” Pollack on Contracts (1885 and subse

quent editions).

“ An agreement enforceable by law is a contract.”

Indian Contract Act, 1872 (codifying the English

common law).

All of these standard definitions of “ contract” em

phasize enforceability “ at law”1 or “ by law” as the es

sential element of “ contract” . Enforceable “ at law” or

“ by law” is a figure of speech. It means that a court

will give some effect to the agreement. The law of itself,

and until a court acts, is an abstraction that enforces

nothing. Only when a judgment or decree may be ob

tained in a court to give some effect to an agreement

can it be said that the agreement is a contract. An agree

ment to Which courts will give no effect is binding only

upon the consciences of the makers. Thus the alleged con

tract, the agreement, between the appellants not to per

mit non-Caucasians to occupy the residences covered by

the agreement is of no legal significance either between

them, or the respondents, unless a court will enforce it.

This is true of every agreement that is claimed to be a

contract, and necessarily is true of the agreement here in

litigation. Thus the position is untenable that a State in

5

enforcing such an agreement is not ACTING, but merely

taking a neutral position, accepting a consequence that

is brought about merely by a private agreement, for no

legal consequence can possibly result from this private

agreement unless a court will hold that the agreement is

a contract and renders some decree giving it legal effect.

The legal effect petitioned for by the plaintiffs is that the

present occupants be ousted from their homes because of

their race, and that they be ousted by a decree of the

court. The grievance of the appellants is that some of

the co-parties to their agreement have broken faith and

permitted the respondents to become occupants of some

of the residential properties. Thus their private agree

ment has become of no avail, and unless the State through

its courts takes affirmative action it will continue to be of

no avail. The very fact that the appellants’ agreement

has proved futile, and that they are frustrated in at

taining their objective by their own action, led them to

bring this suit. The suit is nothing but a petition for

action by the State to make effective an agreement, other

wise ineffective, by a decree ousting the respondents from

their homes.

THE PROPERTY LAW ASPECT.

Racial residential segregation by neighborhood agree

ments, covenants or conditions in deeds would be only

temporarily effective, assuming them enforceable, un

less they can be tied to the land, and bind subsequent

purchasers, Recently—not earlier than 1915—the courts

of some States evolved the doctrine that these racial re-

6

strictive agreements constitute what they call “ equi

table servitudes”, meaning that a court of equity will en

force them against subsequent holders who acquire the

land with notice, or knowledge of the agreements. To per

fect the plan of perpetuating these exclusive districts for

generations to come, the agreements are recorded and rec

ordation is held to make them effective against pur

chasers without actual notice. In at least one instance

an agreement provided that it was to continue in force

for ninety-nine years from the date of recording. See

Lyons v. Wallen (1942), 191 Okla. 567, 133 P. (2d) 555. It

cannot be denied that the act of the State in recording

these instruments is essential to the program. Equally

essential is the act of the State through its legislature or

its courts in making the law to be that recordation makes

the agreements binding upon future holders without no

tice.

Even without this last perfecting feature of recordation

and its effect, the doctrine of racial equitable servitudes

has come into existence by State action, by the action of

the Supreme Courts of the relatively few States that have

adopted it.

“ The judicial act of the highest court of the State,

in authoritatively construing and enforcing its laws

is the act of the State.”

Twining v. New Jersey, supra.

One has to reflect but a moment on the consequences

of a State’s maintaining such a system of land law to see

that the Equal Protection of the Law Clause of the Four

teenth Amendment forbids it. The American people in the

Reconstruction period were in deadly earnest in giving

7

equality of civil rights to all races of our citizens. Con

gress quickly saw that the abolition of slavery by the

Thirteenth Amendment was but a slight step. It pro

ceeded to enact the Civil Rights Bill of 1866, 14 Stat. 27.

It sought by that, statute to nullify the racial discrimina

tion made in the property law and contract law of many

States. The statute declared that:

“ citizens, of every race and color * * * shall have

the same right, in every State and Territory of the

United States, to make and enforce contracts, to sue,

be parties, and give evidence, to inherit, purchase,

lease, sell, hold and convey real and personal property

* * * as is enjoyed by any white citizen,”

Fear arose, however, that authority to enter this field

of legislation, formerly exclusively in the power of the

States, was not given to Congress by the Thirteenth

Amendment, Consequently the Fourteenth Amendment

was drafted to forbid the States to deny equality of civil

rights to any race among our citizens. This is the well-

known history of the origin of the Equal Protection

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, As soon as the lat

ter Amendment was ratified Congress expressly “ re

enacted” the Civil Rights Bill of 1866. See Section 18 of

the Act of May 31, 1870, 16 Stat. 144.

In Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60, 78, the Supreme

Court, after recounting the history of the Equal Pro

tection Clause, as above, said:

“ Colored persons are citizens of the United States

and have the right to purchase property and enjoy

and use the same without laws discriminating against

them solely on account of color.” (Emphasis added.)

8

Referring to the two Civil Rights Acts of 1866 and 1870,

as contemporary interpretations by Congress of the mean

ing of the Fourteenth Amendment, the Court said:

“ These enactments did not deal with the social

rights of men, but with those fundamental rights in

property which it was intended to secure upon the

same terms to citizens of every race and color.”

Is there a more fundamental right in property than that

of a family to live in a home which they legally own1?

Let any man ask himself that question with respect to

his own house. Is it possible to conceive that the gen

eration that framed and adopted the Fourteenth Amend

ment meant that the States were still free to create

through the decisions of their courts a body of contract

law or a body of property law under which all the resi

dential area of an entire town or city can be closed against

Negroes or people of any other race?

It was long after that generation passed away before

attempts were begun to get around the Constitution by

restrictive conditions and eonvenants in deeds, and later,

by neighborhood agreements. The earliest court decision

on them was in 1915 by the Supreme Court of Louisiana.

Queensborough Land Co. v. Gazeaux, 136 La. 774, 67 So.

641, sustaining a covenant against sale to any Negro. The

Supreme Court of Missouri held likewise in 1918. Koehler

v. Rowland, 275 Mo. 573, 205 S.W. 217. The next year this

Court refused to follow this novel doctrine and held

that a condition in a deed for forfeiture in case of sale

to any non-Caucasian was an illegal restraint on aliena

tion forbidden by the Civil Code, § 711. Los Angeles In

vestment Co. v. Gary, 181 Cal. 680, 186 Pac. 596. Un-

9

fortunately, however, the Court drew a distinction and

held that a condition for forfeiture in case of occupancy

of the property by a non-Caucasian was not a forbidden

restraint on alienation. This was the start in making the

rule of law in this State upon which appellants rely.

It is to be noted, however, that the Court stated, “ what

we have said applies only to restraints on use imposed

by way of condition and not to those sought to be im

posed by covenant merely.” (p. 683, emphasis added.)

The fact that the Court expressly confined its decision

to conditions in deeds, even saying that it did not apply

to covenants in deeds, shows that it did not intend the

decision to apply to “ neighborhood agreements,’’ which

are not made in instruments of conveyance, but are agree

ments between present owners, often very numerous,

covering large areas of cities, and capable of covering

a whole city. These when recorded were later held to

create “ equitable servitudes” closing the entire area

covered by them to all members of any proscribed race.

Wayt v. Patee (1928), 205 Cal. 46. Often these agree

ments exclude all non-Caucasians, and sometimes some

branches of the Caucasian race, such as Armenians and

Turks. (See 33 Calif. L. Rev. at p. 15.)

These agreements are motivated by race prejudice and

operate without regard to the culture or refinement of the

individuals affected. This is illustrated by an unappealed

decision of the Superior Court for the County of Los

Angeles. In enforcing a neighborhood agreement against

use or occupancy “ by any person whose blood is not

entirely that of the Caucasian or white race,” Judge

Myron Westover said:

10

“ The evidence showed and the Court finds that

both defendants are American Indians of the Nanti-

coke tribe, but with some white blood. Mr. Rodgers

says his mother was Indian and his father white, but

with some Indian blood, while all the blood of Mrs.

Rodgers is Indian. She received her Bachelor’s and

Master’s degree from New York University and also

studied psychiatry in Vienna under Dr. Alfred L.

Adler, and taught public school in New Jersey for

from ten to twelve years.

However desirable the defendants may be in the

cultural life of the immediate community and as

neighbors, we must apply the law as it exists. Re

strictions as to use or occupancy will be enforced in

a court of equity.”

Los Angeles Daily Journal, June 14, 1945.

In view of the Court’s caution in the Gary case, in say

ing that its decision did not apply even to covenants in

deeds, it is highly probable that it would have reached

a different result if it had foreseen that its doctrine would

be extended to “ neighborhood agreements,” which make

wholesale exclusions from large areas in cities of all

persons who have any trace of non-Caucasian blood, re

gardless of their social or economic status, and regardless

of their culture and refinement.

The concluding short paragraph of the Court’s opinion

in the Gary case was addressed to a constitutional ques

tion but as this brief will later show it was not the con

stitutional issue presented to the Court in this ease.

11

STATE OF THE AUTHORITIES ON THE CONSTITUTIONAL

ISSUE IN THIS CASE.

It is submitted that the constitutional issue made in

this case, the sole ground of decision of the Court below,

has never been decided by the Supreme Court of Cali

fornia.

It will further appear that the Supreme Court of the

United States has never decided the question, never

having been presented with a case involving it.

But it will still further appear that the Supreme Court

of the United States has decided every one of the separate

elements involved in the constitutional issue and decided

them favorably to respondents’ contentions. It is submit

ted that the combined effect of the prior decisions of that

Court would compel it to reach a result in this case

favorable to the respondents.

(a) Supreme Court of California.

In their opening brief counsel for appellants rely almost

wholly upon Los Angeles Investment Co. v. Gary, 181

Cal. 680 and the United States Supreme Court decisions

therein cited, as decisive of the constitutional issue.

What was the constitutional issue to which this Court

addressed itself in the Gary case?

All that this Court said was:

“ The particular condition in this ease being one

against the occupation of the property by persons

not of the Caucasian race, the question suggests it

self as to whether it is unlawful discrimination

against certain classes of citizens and, therefore,

within the prohibition of the federal Constitution.

12

* * # Construing this amendment [the Fourteenth],

the Supreme Court of the United States has held in a

number of cases that the inhibition applies exclusively

to action by the State and has no reference to taction

by individuals, such as is invoked here.” (p. 683,

emphasis added.)

The only other reference in any opinion of this Court

to any constitutional issue in cases of this kind is in

Jams Investment Go. v. Walden (1925), 196 Cal. 753, 754.

The opinion there makes a passing reference to “ the

authorities presented by appellant in support of his con

tention touching the constitutionality of the condition set

forth 'in the contract.” (Emphasis added.) The Court

cited the Gary case as settling this, issue.

Thus it appears that this Court has never had brought

to its attention that while the acts of individuals in making

such agreements are not of themselves unconstitutional

any act of the State in recognizing them as legal and

enforcing them is unconstitutional.

(b) The United States Supreme Court decisions cited and re

lied upon in the Gary case.

United States v. Cruikshank, 92 U. S. 542: In this case

the Supreme Court was concerned with the question

whether criminal or tortious acts committed by one private

person against another were forbidden by the Fourteenth

Amendment and therefore brought within the power of

Congress to penalize or redress. The Court held that

such private acts were not within the scope of the Amend

ment. Obviously criminal and tortious acts of one private

person against another are purely private acts, unaided

13

and unsupported by State action, and even contrary to

State law.

Civil Bights Cases, 109 U. S. 3: What was characterized

in these cases as merely the “ action of private indi

viduals” was the refusal of the keeper of a hotel or other

place of entertainment or public amusement to admit or

serve a patron because of his color. It is obvious that

such refusal is operative without aid or support of the

State. The Court made it clear, however, that the Four

teenth Amendment does forbid a State to legalize or aid

such discriminatory practices either by act of the legis

lature or by act of any other officer or organ of State

government, including its Courts. That action of a State

court, in rendering a decree ousting a person from his

quarters in a hotel solely because of his race wrould be a

violation of the Amendment is clear. How does that

differ from a decree ousting a person from his home

because of his race? The opinion in the Civil Bights

Cases, repeatedly affirms that it was dealing with private

action that is exclusively such, unaided, unsanctioned and

unsupported, by action of any organ of State government.

It repeatedly states that the command “ No State shall

* * *” includes “ the action of State officers, executive,

or judicial,” (p. 11, emphasis added); “ acts done under

State authority.” (at p. 13.) It carefully points'out that

it is dealing with “ wrongful acts of individuals, unsup

ported by State authority in the shape of laws, customs,

or judicial or executive proceedings.” (p. 17, emphasis

added.)

Virginia v. Bives, 100 U. S. 313: While it is true that

the opinion in this case says that the Fourteenth Amend-

14

ment has “ reference to State action exclusively, and not

to any action of private individuals” (p. 318), it also

refers to “ the violation of the constitutional provisions,

when made by the judicial tribunals of a State.” (p. 319.)

United States v. Harris, 106 U. S. 629: A provision of

an Act of Congress was held not within the power given

Congress to enforce the Fourteenth Amendment. The

Court said:

“ As, therefore, the section ;of the law under con

sideration is directed exclusively against the action

of private persons, without reference to the laws of

the State or their administration 'by her officers, we

are clear in opinion that it is not warranted by any

clause in the Fourteenth Amendment to the Consti

tution.” (Emphasis added.)

If counsel in the Gary case had clearly presented to

the Court the real issue, State Court enforcement of a

body of State contract law or property law under which

racial zoning may be accomplished, is it conceivable that

this Court would have thought the cited cases decisive?

In fact the grounds assigned for demurrer to the com

plaint in the Gary case do not mention State court en

forcement of the condition as a ground. No brief or

argument was presented to this Court in behalf of Gary.

(See 181 Cal. at p. 681.)

Counsel for appellants in that case (Los Angeles In

vestment Co.) argued in their brief:

“ The provision in the deed forbidding alienation

to persons other than of the Caucasian race is not the

act of the State. It is the act of an individual—the

corporation that made the condition in the deed.”

(p. 37.)

15

It is submitted that this Court was left to believe that

that was the whole of the constitutional issue raised. And

it is submitted that the Court is now presented with the

real constitutional issue for the first time.

(e) Decisions of other State Courts.

While remarks have been made in the opinions of

Supreme Courts of six other States, and of lower courts

of two more States about some kind of a constitutional

issue in this class of cases, these remarks fall into two

classes: (1) a brief reference to the decision of the

Supreme Court of the United States in Corrigan v.

Buckley, 271 U. S. 323, as settling that racial restrictive

agreements are not unconstitutional; (2) those which dis

pose of the supposed issue by citing the Civil Rights Cases

and other decisions of the United States Supreme Court

like those cited in the Gary case.

Of the first class are:

Lyons v. Wallen, 191 Okla. 567, 569, 133 P. (2d)

555, 558 (dictum,, issue not pleaded);

Ridgway v. Coburn, 163 Misc. 511, 514, 296 N.Y.S.

936, 942;

United Cooperative Realty Co. v. Hawkins> 269 Ky.

563, 565, 108 S. W. (2d) 507, 508 (apparently

dictum) ;

Meade v. Dennistone, 173 Md. 295, 302, 196 Atl.

330, 333;

Doherty v. Rice, 240 Wis. 389, 397, 3 N. W. (2d)

734, 737;

Thornhill v. Herdt (Mo. App.), 130! S. W. (2d) 175,

178.

16

Of the second class are:

Queensborough Land Co. v. Caseaux, 136 La. 724,

67 So. 641;

Chandler v. Zeigler, 88 Colo. 5, 6, 291 Pac. 822, 823;

Meade v. D'ennistone, supra,;

Par male e v. Morris, 218 Mich. 625, 627, 188 N. W.

330;

Porter v. Barrett, 233 Mich. 373, 376, 206 N. W. 523,

533.

It is to this last group of four States that this Court

must look for whatever aid they afford on the present

question, for the Courts in the first class so completely

misconceived the decision of the Supreme Court of the

United States in Corrigan v. Buckley that what considera

tion they gave to the question is negligible. Typical of

the opinions in this first group is the statement in

Ridgwuy v. Coburn, supra:

“ It is sufficient to say that the United States Su

preme Court has held that a covenant of this precise

character violated no constitutional right, Corrigan

v. Buckley, 271 U. S. 323.”

If emphasis be put on the word “ covenant” in this

passage the statement is not wide of the mark, but the

New York Court was misled into assuming that this

settled the question of State court enforcement of such a

covenant, a question that was not before the Supreme

Court in Corrigan v. Buckley.

Corrigan, v. Buckley.

Corrigan, et ial. v. Buckley, 271 U. S. 323, was an appeal

from a decision of the Court of Appeals of the DISTRICT

17

OF COLUMBIA. Corrigan, Buckley and other landown

ers had made mutual agreements not to sell) to any person

of Negro race or blood. Corrigan contracted to sell to a

Negro, and Buckley, before any conveyance, sued to re

strain Corrigan from conveying to Curtis, the Negro

buyer, and the latter from taking title. The Supreme

Court of the District granted an injunction and the Court

of Appeals affirmed, 299 Fed. 899. The latter Court,

differing from the Supreme Court of California, held that

a restriction against sale to all members of a particular

race was not an illegal restraint on alienation by the com

mon law of the District.

The defendant, Curtis, had pleaded that the covenant

is void, as a denial of due process of law and equal pro

tection of the laws, relying on the Fifth, Thirteenth and

Fourteenth Amendments.

The Supreme Court of the United States dismissed the

appeal on the ground that the pleading had raised no

substantial constitutional or statutory question, which was

then necessary to its having appellate jurisdiction. Since

it had long been settled that the Thirteenth Amendment

is directed at nothing but slavery, and that the Four

teenth Amendment applies only to the States, the Court

regarded the contentions based upon them as frivolous.

There remained the Fifth Amendment, which contains no

equal protection clause, but does contain a due process

of law clause. The Court, said: “ The Fifth Amendment

‘is a limitation only upon the powers of the General

Government’ * * * and is not directed against the action

of individuals.” The Court made it clear that it was

answering only the contention that “ the indenture or

18

covenant which is made the basis of the bill, is ‘void.’ ”

Summarizing, it said:

“ It is obvious that none of these Amendments pro

hibited private individuals from entering into con

tracts respecting the control and disposition of their

own property; and there is no color whatever that

they rendered the indenture void.” (Emphasis added.)

Then comes this most significant fact, the Court pointed

out that whether enforcement of the covenant by a Court

of the District of Columbia would be unconstitutional was

not in issue in the case, saying, “it was not raised by the

petition for the appeal), or by any assignment of error,

either in the Court of Appeals or in this Court.”

Counsel for appellants had attempted to raise that issue

in their brief (271 U. S. at p. 324), but the Supreme Court

holds that a constitutional issue cannot be raised in that

manner.

Even if that issue had been raised it would not have

been the issue in the present case. Whether the due

process of law clause of the Fifth Amendment forbids

Courts of the District of Columbia or the Territories to

enforce such covenants, is not the question in this case,

which is, whether a State court consistently with the

Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment

can enforce a body of State contract law or a body of

State property law under which racial zoning may be

accomplished, in face of the decisions of the United States

Supreme Court that a State may not accomplish it by act

of any of its legislative organs.

This question has never been presented to the United

States Supreme Court.

19

[Note also that the Supreme Court did not even affirm

the holding of the Court of Appeals that such covenants

were legal as a matter of the property law of the District

of Columbia. That question was not then appealable to

the Supreme Court, and that Court has never yet con

sidered it.]

THE UNITED STATES SUPREME COURT’S DECISIONS ON THE

SEPARATE FACTORS INVOLVED IN THE PRESENT CASE.

1. Is racial zoning by State legislation unconsti

tutional?

2. Are the decisions of State courts creating or

recognizing a body of non-statutory law in the State,

which legalizes racial zoning State action forbidden

by the Fourteenth Amendment?

(1) Racial zoning by State statutory law.

Buchaium v. Warley, 245 IT. S. 60, held that State ac

tion, namely by city ordinance, zoning a city racially was

a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment. The ordinance

forbade any white or Negro person to move into a resi

dential block in which a majority of the houses are already

occupied by persons of the other race. A Negro had

contracted to buy a house and lot on the condition that

he could legally occupy the property as a residence. The

seller sued for specific performance, and challenged the

validity of the ordinance. The Court being conscious

that few persons buy residential property in which they

cannot legally live, saw that the ordinance was a restraint

on sale, cutting out all members of a particular race as

buyers, and held that such a reduction of an owner’s right

20

to sell was a deprival of property without due process of

law, and that the ordinance therefore violated the Four

teenth Amendment. Since under the ordinance it was

immaterial what was the race of a seller, the seller could

not invoke the Equal Protection Clause. It seems clear

from statements in the opinion that from a buyer’s

point of view the ordinance violated the Equal Protection

Clause, by excluding him from occupancy because of his

race. Mr. Justice Day, for a unanimous Court, discussed

the history of the Fourteenth Amendment, showing that

one of its chief purposes was to secure to all persons

“ the right to purchase property and enjoy and use the

same without laws discriminating against them solely on

account of color.” (pp. 78-79.)

The Court further said:

“ It is urged that this proposed segregation will

promote the public peace by preventing race conflicts.

Desirable as this is, and important as is the preserva

tion of the public peace, this aim cannot be accom

plished by laws or ordinances which deny rights

secured or protected by the Federal Constitution.”

(p. 81.)

So also the Court brushed aside the contention that

acquisition of property by colored persons in white neigh

borhoods depreciates the value of property, (p. 82.) Where

this is true it but illustrates that the Constitution some

times subordinates pecuniary interests to more funda

mental rights.

Harmon v. Tyler, 273 U. S. 668: The decision in this

case is even more closely in point. A New Orleans ordi

nance barred whites or Negroes from any “ community or

21

portion of the city * * * except on the written consent of

a majority of the opposite race inhabiting such com

munity or portion of the city.” (See 1Tyler v. Harmon,

158 La. 439, 441, 104 So. 200.) The Supreme Court held

the ordinance unconstitutional. The scheme which the

ordinance sought to establish was close to legalizing

neighborhood agreements such as are in issue in the

present case. Instead of neighborhood agreements to

exclude, as in the present case, the ordinance attempted

to require neighborhood agreements to admit. The prac

tical result of the two schemes is the same. Both require

a combination of State action and action by private per

sons. If a State is prohibited from legalizing the one by

legislative action is it free to legalize the other by judicial

action ?

(2) A State Court’s decision giving effect to the State’s non-

statutory law is State action within the meaning of the

Fourteenth Amendment.

“ The judicial act of the highest Court of the State in

authoritatively construing and enforcing its laws is

the act of the State.” Twining v. Neiv Jersey, 211

U. S. 78, 90-91.

The law construed and enforced by the State Court in

that case was its common law, judge-made or non-statutorv

law.

There are many decisions in which the only action of

a State held by the Supreme Court to be a violation of

the Fourteenth Amendment consisted of a judgment of a

State court interpreting and enforcing its common law.

Powell v. Alabama, 287 U. S. 45 (procedural law);

Moore v. Dempsey, 261 U. S. 86 (procedural law);

22

Bridges v. California, 314 U. S. 252 (substantive

law);

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296 (substantive

law);

A. F. of L. v. Swing, 312 IT. S. 321 (substantive

law);

Bakery Drivers Local v. Wohl, 315 IT. S. 760 (sub

stantive law).

If the plea that the action of these State courts of itself

was a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment raised no

constitutional issue the Supreme Court of the United

States would not have had jurisdiction to review and

reverse the State Court decisions in the above cases, for

no other unconstitutional action of a State was pleaded

in any of them.

“ No State shall * * * deprive any person of life,

liberty or property, without due process of law; nor

deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal

protection of the laws.” Fourteenth Amendment,

Section 1.

If, as is held in the above cited cases, a judgment of a

State Court interpreting and enforcing its non-statutory

law is State action under the first clause, it is equally

State action under the second or Equal Protection Clause.

The United States Supreme Court so holds. Three

times for a unanimous Court the following has been

stated, once by Mr. Justice Cray, once by Mr. Justice

Holmes, and once by Chief Justice Hughes:

“ Whenever by any action of a State, whether

through its legislature, through its courts, or through

its executive or administrative officers, all persons of

23

the African race are excluded solely because of their

race or color, from serving as grand jurors in the

criminal prosecution of a person of the African race,

the equal protection of the laws is denied him con

trary to the Fourteenth Amendment of the Consti

tution of the United States.” (Emphasis added.)

So in

Carter v. Texas, 177 U. S. 442, 447;

Rogers v. Alabama, 192 U. S. 226, 231;

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U. S. 587, 589.

If by holding it to be a rule of the common law of a

State that Negroes are ineligible to jury service a State

Court could break through the command of the Equal

Protection Clause there are still a few States in which

the Courts would oblige the advocates of white supremacy.

The Equal Protection Clause was put into the Consti

tution primarily to nullify the Block Codes of the South

which discriminated against Negroes with respect to their

civil rights. With this origin freshly in mind, the Su

preme Court said, in 1873,

“ We doubt very much whether any action of a State

not directed by way of discrimination against the

Negroes as a class, or on account of their race, will

ever be held to come within the purview of this provi

sion.” (Slaughter-House cases, 16 Wall. 36, 81.)

Soon, however, it was perceived that the language of the

clause was general, “ deny to any person”, and the Court

held that administrative action of officials in San Fran

cisco in excluding Chinese from operating laundries was

a denial of Equal Protection. (Tick Wo v. Hopkins, 118

U. S. 356.)

24

Soon also it was perceived that the clause prohibits

irrational discrimination against any class of persons,

whether because of their race or on any other ground that

bears no rational relation to the object of the legislation.

A formula for interpretation of the Equal Protection

Clause evolved:

“ It does not prevent classification, but does require

that classification shall be reasonable, not arbitrary,

and that it shall rest upon distinctions having a fair

and substantial relation to the object sought to be

accomplished by the legislation.”

This is repeated in numerous cases.

Because, however, the primary purpose of the Clause

was to prevent racial discrimination there is not a single

decision of the Supreme Court that recognizes that race

alone is a rational justification for any discrimination

with respect to civil rights. So far as the Supreme Court

has sustained State laws which require racial separation

in public conveyances and public schools, it has been ex

pressly put on the ground that no discrimination is made

by such laws in that to be valid they must provide equal

facilities. [Compare the recent decision that a State may

not require racial separation in the State of persons

travelling into or through the State. Morgan v. Common

wealth of Virginia, 66 S. Ct. 1050.]

Any State law that outright forbade Negroes to ride

on any railroad or any street car line would unquestion

ably be invalid, even if the law applied to a single rail

road or a single street car line. We are here concerned

with a body of State law under which Negroes or any

other proscribed race can be totally excluded from par-

25

ticular districts or portions of a city, and no one pretends

that the districts left open to them are equal.

Surely the appellants will not contend that a body of

State law escapes unconstitutionality by permitting Ne

groes to make agreements excluding whites from their

neighborhood as an offset to legalizing agreements of

whites to exclude Negroes from their neighboi’hood. It is

obvious that such a law

“ while equal and reciprocal in phraseology, as re

gards the two races, does in reality, the facts of life

being what they are; discriminate heavily against the

Negro race.” 31 Harv. L. Rev., 479.

The ordinance held void in Buchanan v. War ley, supra,

had the reciprocal feature of forbidding whites to move

into “ black blocks” and Negroes to move into “ white

blocks.” So the ordinance held void in Harmon v. Tyler,

supra, reciprocally forbade whites to move into Negro

“ communities or districts” without the consent of a ma

jority of the Negroes residing there. This reciprocity

saved neither ordinance.

A judgment of a State court ousting a white family

from a home subject to a restrictive agreement against

occupancy by whites would be as unconstitutional as the

action sought by appellants in this case. It is the con

tention of the respondents that a State court judgment

ousting any person from his home because of his race,

whatever it may be, is State action violating the Equal

Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. That

Clause extends its protection to every person. Denial

to one fman of the privilege of living in his home is not

made constitutional by denying another man, of a dif-

26

ferent race, the privilege of living in his home. Under

the Equal Protection Clause, “ the essence of the consti

tutional right is that it is a personal one.” McCabe v.

Atchison, T. \& S. F. R. Co., 235 U. S. 141, 161; Missouri

ex rel. Gaines, 305 U. S. 337, 351; Mitchell v. United

States, 313 IT. S. 80, 97.

CONCLUSION.

The respondents acquired their home from a willing

seller and are, under the law of this State, the legal

owners. This, is a suit to oust them from their home

solely because they are non-Caucasians. If they were

Caucasions, concededly no action would lie. Without ac

tion by the State of California they may continue to

reside in their home. This Court is asked, by appellants,

to interpret and enforce the law of this State as requiring

action by the State, through its Court, to oust them. Such

action would be in violation of the Equal Protection Clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The judgments below should be affirmed.

Dated, San Francisco, California,

September 4, 1946.

Respectfully submitted,

R obert W. K e n n y ,

Attorney General of the State of California,

Cla ren ce A. L i n n ,

Assistant Attorney General of the State of California.

D . 0 . M cG ovney ,

School of Jurisprudence, University of California,

Special Advisor to the Attorney General

of the State of California.