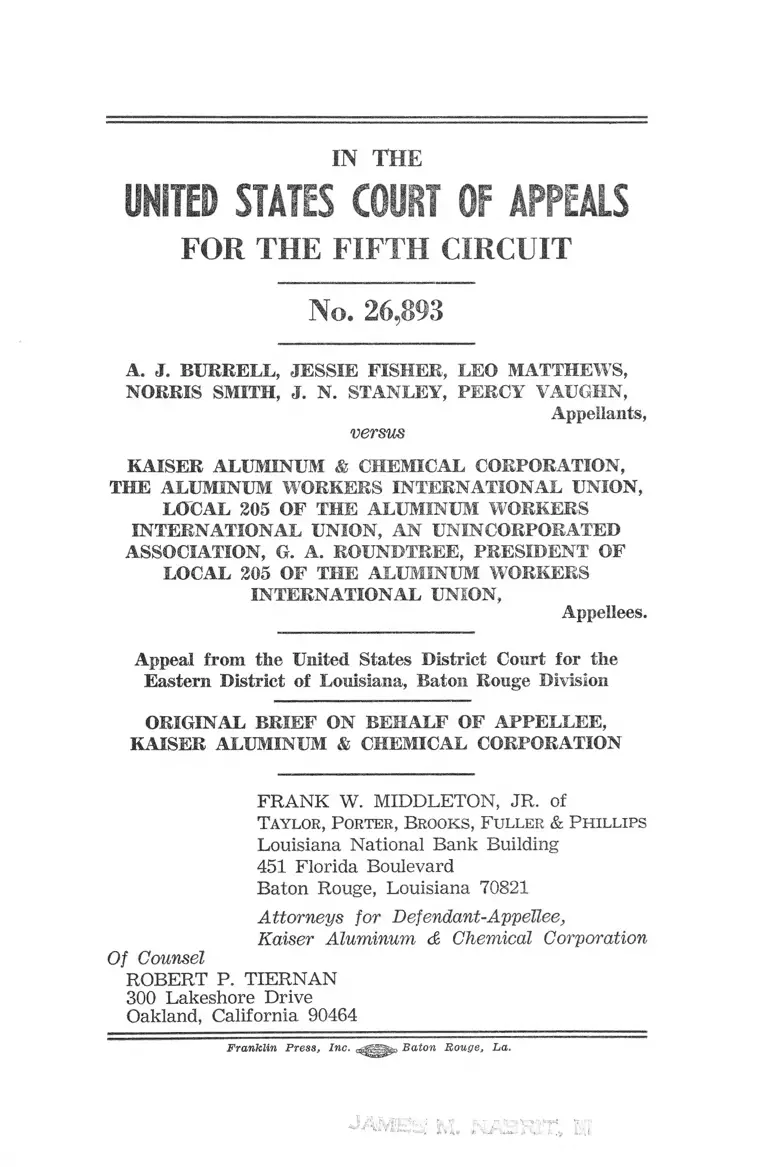

Burrell v Kaiser Aluminum and Chemical Company Original Brief on Behalf of Appellee

Public Court Documents

December 1, 1968

21 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Burrell v Kaiser Aluminum and Chemical Company Original Brief on Behalf of Appellee, 1968. a64b0f25-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1b32e1ea-5fad-489e-8b7a-6fe50aaed08b/burrell-v-kaiser-aluminum-and-chemical-company-original-brief-on-behalf-of-appellee. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

IN THE

No. 26,893

A. J. BURRELL, JESSIE FISHER, LEO MATTHEWS,

NORRIS SMITH, J. N. STANLEY, PERCY VAUGHN,

versus

Appellants,

KAISER ALUMINUM & CHEMICAL CORPORATION,

THE ALUMINUM WORKERS IN TE RN ATIO N AL UNION,

LOCAL 205 OF THE ALUMINUM WORKERS

IN TE R N A TIO N AL UNION, A N UNINCORPORATED

ASSOCIATION, G. A. ROUNDTREE, PRESIDENT OF

LOCAL 205 OF THE ALUMINUM WORKERS

IN TE R N ATIO N AL UNION,

Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Louisiana, Baton Rouge Division

O RIG INAL BRIEF ON BEHALF OF APPELLEE,

KAISER ALUMINUM & CHEMICAL CORPORATION

FR AN K W. MIDDLETON, JR. of

Taylor, Porter, Brooks, Fuller & Phillips

Louisiana National Bank Building

451 Florida Boulevard

Baton Rouge, Louisiana 70821

Attorneys for Defendant-Appellee,

Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical Corporation

Of Counsel

ROBERT P. T IERNAN

300 Lakeshore Drive

Oakland, California 90464

Franklin Press, Inc. Baton Rouge, La.

' i M I : U .

I N D E X

Page

STATEMENT OF THE CASE ............................................ 1

ARGUMENT

I. The Lower Court Properly Held That It Had

No Jurisdiction, Since Plaintiff Here Has Failed

to Comply with the Procedural Requirements of

Title V II— the EEOC Not Having Found That

There Was a Violation of the Act, Nor Had an

Opportunity to Attempt Conciliation, Nor Was

There Here a Failure to Secure Voluntary Com

pliance with the A c t .............................................. 5

II. This Case Was Properly Dismissed in the Lower

Court for Lack of Jurisdiction in View of the

Existence of a Written Conciliation Agreement

Covering the Issues in Dispute and Which Estab

lished the Equal Employment Opportunity Com

mission as the Sole Party for Judging Com

pliance with the Provisions of Such Agreement.... 7

A. A Reasonable and Meaningful Construction

to Title V II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

42 U.S.C. Para. 2000e, et. seq., Requires the

Finding by This Court That Successful Con

ciliation of an Alleged Unlawful Employ

ment Practice by the Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission, Resulting in an

Agreement by Those Involved, Preempts the

i

ii

Page

Jurisdiction of the Courts Over the Subject

Matter of the Conciliation Agreement.......... 8

B. The Appellants Made a Binding Election of

Remedies When They Chose to Accept the

Benefits of a Conciliation Agreement in Set

tlement of the Discriminatory Employment

Practices Charges ........................................... 10

C. The Acceptance of the Benefits of the Con

ciliation Agreement and the Repudiation of

Their Promises Exchanged for Such Bene

fits Estop the Appellants from Herein Seek

ing Enlarged Remedies from the Same Set

of F acts ............................................................ 13

CONCLUSION ................................................................ 16

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE ............................................. 17

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 26,893

A. J. BURKELL, JESSIE FISHER, LEO MATTHEWS,

NORRIS SMITH, J. N. STANLEY, PERCY VAUGHN,

Appellants,

versus

KAISER ALUMINUM & CHEMICAL CORPORATION,

THE ALUMINUM WORKERS INTERNATIONAL UNION,

LOCAL 205 OF THE ALUMINUM WORKERS

INTERNATIONAL UNION, AN UNINCORPORATED

ASSOCIATION, G. A. ROUNDTREE, PRESIDENT OF

LOCAL 205 OF THE ALUMINUM WORKERS

INTERNATIONAL UNION,

Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Louisiana, Baton Rouge Division

ORIGINAL BRIEF ON BEHALF OF APPELLEE,

KAISER ALUMINUM & CHEMICAL CORPORATION

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

As an appellee, Kaiser does not take issue with the bulk

of the statement of the case presented by appellants, consist

ing principally of a summary of the allegations of plaintiffs’

complaint and the record history of the case.

1

2

Since largely overlooked (except by footnote) in appel

lants’ statement of the case, the factual basis of one of the two

principal points raised by Kaiser must at this time be more

adequately presented to the Court.

The present proceeding is but the last of a long chain of

proceedings instituted by the plaintiff, A. J. Burrell, and vari

ous others associated with him by name from time to time,

all purporting to represent, as a class, the Negro employees

of Kaiser. The first action instituted was a complaint filed

September 27, 1965, lodged with the Equal Employment Op

portunity Commission, complaining of substantially the iden

tical items complained of in the complaint in this case. Follow

ing reference to the Commission, reasonable cause to believe

that a violation of the Act had occurred was found but, under

the letter as well as the spirit of Title V II, representatives of

Kaiser, of the Union and the charging parties, including the

plaintiff here, met and worked out their differences resulting

in a Conciliation Agreement, dated January 30, 1966, spe

cifically dealing with the issues involved in the pre-existing

controversy [which are the same issues involved in the pres

ent controversy].

This history is set forth in the complaint Article V II, D

and E (RlOa). A copy of the Conciliation Agreement was

attached to and made a part of plaintiffs’ complaint as Ex

hibit A (R17a).

It should be noted that this Conciliation Agreement was

signed by the then complaining parties, by Kaiser, by the

Union and by its Local, as well as by the representative of

the Commission, under whose auspices the agreement was

reached (R17a, R22a). Among other things, this written,

3

signed Conciliation Agreement provided “ ***the parties here

by agreed to and do settle the above matter in the following

extent and manner:

“ 1. The respondents agree that the Commission, on re

quest of any charging party or on its own motion,

may review compliance with this agreement. As a

part of such review, the Commission may require

written reports concerning compliance, may inspect

the premises, examine witnesses, and examine and

copy documents.

# # #

“3. The Charging Party hereby waives, releases and

covenants not to sue any respondent with respect to

any matters which were or might have been alleged

as charges with the Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission, subject to performance by the respon

dents of the promises and representations contained

herein. The Commission shall determine whether

the respondents have complied with the terms of

this agreement.” (R17a - R18a)

Without reference to the fact that the Conciliation Agree

ment of January 30, 1966, required by its terms that the

Commission determine compliance with such agreement, the

present complainants, on or about January 20, 1967, filed a

complaint with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commis

sion alleging violation of their rights, the specifics of which

were substantially the same as those dealt with in the com

plaint filed with the Commission in 1965 and disposed of by

the Conciliation Agreement of January 30, 1966 (see plain

tiffs’ complaint, paragraph V III [R13a]).

4

Immediately upon the lapse of sixty (60) days following

the filing of the complaints with the Commission, counsel

for the present plaintiffs demanded and received the statutory

letter authorizing the filing within thirty (30) days there

after of civil action in the appropriate Federal District Court

(R50a).

Within thirty (30) days after the issuance of such statu

tory letter, the present civil action was instituted asking for

judicial determination of the alleged issues between the

parties and covering the same matters dealt with in the

Conciliation Agreement dated January 30, 1966, all without

ever having asked for or having received determination by

the Commission as to “ ###whether the respondents have com

plied with the terms of this agreement.” (Conciliation Agree

ment, Paragraph 3 - R18a).

The lower court in the present matter concluded that this

suit must be dismissed for lack of jurisdiction. Although the

specific reason and authority cited in the opinion of the lower

court refers only to the lack of conciliation as a jurisdictional

prerequisite (R54a), the lower court’s recitation of the his

tory of the matter in the previous two pages of its opinion

and particularly the court’s specific reference to and quota

tion from the Conciliation Agreement of January 30, 1966,

indicates that the existence of and legal significance of the

Conciliation Agreement played some undisclosed part in the

lower court’s finding of no jurisdiction (R52a, R53a). Cer

tainly, this phase of the matter was one most stringently

urged by Kaiser in its motion to dismiss (R30a, R31a), and

was repeatedly and extensively dealt with in both brief and

oral argument by both sides in appearing before the lower

court.

5

Appellee Kaiser submits that there are, therefore, two

principal points or alleged errors of the lower court to be

considered here:

(1) Lack of jurisdiction in the lower court, for failure

to comply with the procedural requirements of Title

V II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, since the EEOC

had not found reasonable cause, nor had an oppor

tunity to attempt conciliation, nor was there a fail

ure to secure voluntary compliance with the Act.

(2) The lack of jurisdiction herein by the lower court

in view of the existence of a written Conciliation

Agreement covering the issues in dispute here, which

agreement establishes the Equal Employment Oppor

tunity Commission as the sole party for judging

compliance with the provisions of such agreement.

ARGUMENT

I

The lower court properly held that it had no jurisdiction,

since plaintiff here has failed to comply with the procedural

requirements of Title V II— the EEOC not having found that

there was reasonable cause to believe that there was a viola

tion of the Act, nor had the EEOC had an opportunity to

attempt conciliation, nor was there here a failure to secure

voluntary compliance with the Act.

Appellants have at considerable length and on some six

different fronts attacked the holding of the lower court with

regard to this point. Kaiser in the lower court filed an origi

nal and two supplemental briefs in support of its position

here, and particularly citing Dent v. St. Louis-San Francisco

Railway Company, et al, 265 F. Supp. 56 (1967), and the

6

decisions of the Fourth Circuit in Mickel v. South Carolina

State Employment Services, 377 F.2d 239 (C.A. 4th, 1967),

and Stebbins v. Nationwide Mutual Ins. Co., 382 F.2d 267

(C.A. 4th, 1967).

We must here concede that Johnson v. Seaboard Coast

Line Railroad C o.,_____F .2d ------- , 59 L.C. 9177 (C.A. 4 th -

October 29, 1968), in a decision by a divided court takes a

contrary position. It is submitted that the dissenting opinion

by Judge Boreman more accurately and correctly sets forth

the proper interpretation of the statute and its application

than does the majority opinion of two of the three judges on

the panel. It should, of course, be noted that this decision

was handed down well after judgment was rendered herein

by the trial court in the instant case.

In view of the fact that this issue will have been decided

by this Court’s decision in Dent v. St. Loms-San Francisco

Railway Company, et al, now pending decision, before con

sideration of the instant case, it is believed unnecessary to

belabor the point herein except to point out the following.

In the instant case, this suit was filed before there had

been any investigation by the EEOC and before there was

any finding of reasonable cause to believe a violation had

been committed and, certainly, therefore, before there was

any opportunity whatsoever for conciliation to take place or

for there to be any voluntary compliance if, in fact, there

were any violation. In fact, as soon as the minimum time

had run, the statutory suit letter was here issued on demand

of counsel for appellant. Thus the present case is substantially

distinguished from Johnson v. Seaboard Coast Line Railway

Co. Supra; and Choate v. Caterpillar Tractor C o .,---- F.2d

7

___ , 58 L.C. 9162 (C.A. 7th, October 17, 1968). In Johnson

it should be noted that the complaint filed with the EEOC

was received on January 14, 1966. A fter investigation, the

EEOC, on July 18, 1966, determined that there was reason

able cause. Subsequently, the statutory letter was issued on

August 8, 1966, advising that due to workload requirements,

it would be impossible to undertake conciliation. Suit was

thereafter filed. Similarly, in Choate, the EEOC conducted

an investigation, issued a finding of reasonable cause some

seven months thereafter in issuing the statutory letter. In

both of these cases— the only appellate decisions dealing with

the point since Michel and Stebbins— there had been an in

vestigation resulting in a finding of probable cause and after

a lapse of six or seven months subsequent to the filing of the

complaint, the EEOC had had an opportunity to attempt con

ciliation but was unable to do so. Therefore, both the Fourth

and Seventh Circuits were unwilling to hold that there had

been a lack of procedural exhaustion of remedies before the

EEOC. Such is not sufficiently similar to the actual facts

involved in the instant case to be determinative of the point

of this case and before this Court. Similarly, we should point

out that a number of the list of cases cited by appellant in

brief as allegedly supporting his position involve statutory

letters actually issued after the failure to achieve conciliation

despite the efforts of the EEOC to do, so. However, we are

sure that this Court will have adequately explored this field

in its consideration of and (presumably) prior decision in

Dent.

II

This case was properly dismissed in the lower court for

lack of jurisdiction in view of the existence of a written

8

Conciliation Agreement covering the issues in dispute and

which established the Equal Employment Opportunity Com

mission as the sole party for judging compliance with the

provisions of such agreement.

A.

A Reasonable and Meaningful Construction to Title VII

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. para. 2000e,

et seq., Requires the Finding by This Court That Suc

cessful Conciliation of an Alleged Unlawful Employment

Practice by the Equal Employment Opportunity Com

mission, Resulting in an Agreement by Those Involved,

Preempts the Jurisdiction of the Courts Over the Sub

ject Matter of the Conciliation Agreement.

The Court below found that the subject matter of the

instant suit by the Appellants was “ the subject of a con

ciliation agreement which was later approved by the Equal

Opportunity Commission and signed by all parties to the

present suit on January 30, 1966. This agreement . . . was

entered into for the purpose of settling the disputes between

these parties . . .” (R52a). In concert with this finding of

the Court below it is observed in Title V II of the Civil Rights

Act, Section 706, Prevention of Unlawful Employment Prac

tices, that the sole and exclusive power of the EEOC is “ to

eliminate any such alleged unlawful employment practice by

conference, conciliation and persuasion.” (Emphasis added.)

The Court below found that based upon this argument

(among others) and the brief of the Appellees, the suit “must

be dismissed for lack of jurisdiction.” This finding is not

only a valid one under the law but necessary to preserve the

9

integrity of Title V II of the Civil Rights Act. To hold other

wise would be to deny the very purpose for the creation of

the EEOC and to strip it of its single power to eliminate un

lawful employment practices in the United States.

This Appellate Court is not only passing upon the juris

diction to entertain the subject matter of a final and binding

conciliation agreement fostered, nurtured, and executed under

the aegis of the EEOC, but is also passing upon the effec

tiveness of all conciliation agreements, present and future,

that the EEOC has fathered or shall father in its endeavors

to eliminate unlawful employment practices. For if this Court

finds error in the no-jurisdiction decision of the Court be

low it is unequivocally recognizing that the EEOC is power

less to effectively conciliate any alleged unlawful employment

practice.

The skill of conciliation is found in the ability of the

conciliator to cause two or more disputing parties to agree.

(In the instant case the agreement took the form of an ex

change of promises among the Appellants and the Appellees

and a mutual understanding of how changed employment

practices would operate.) (R17a-R22a) The reduction of re

ciprocal promises to writing constitutes the documented Con

ciliation Agreement which, in this instance, is the product

of the EEOC’s efforts. I f the Conciliation Agreement reached

by the disputing parties does not conclusively bind the parties

to its terms, does not resolve the dispute that it purports to

settle, or is unenforceable in its specified exclusiveness, then

in fact there is no real agreement. And, moving backwards,

if there is no agreement there is no real conciliation; and if

there is no real conciliation the conciliator has no actual

conciliation powers. Thus, in the instant case, unless this

10

Court finds the Conciliation Agreement in issue preemptive

as to all it purports to resolve and hold, the EEOC must

necessarily be recognized as without actual power to function

in any useful manner under Title V II of the Civil Rights Act.

The conciliation power of the EEOC is its sole and ex

clusive opportunity to eliminate unlawful employment prac

tices in the United States; and it therefore relies upon the

vitality, effectiveness, and binding nature of those concilia

tion agreements it fosters and endorses to be final and bind

ing. I f the Appellants are permitted by this Court to pursue

in any other forum those matters that were “made the sub

ject of a conciliation agreement which was later approved

by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and

signed by all parties to the present suit . . .” (R52a) then

it is eliminating the exclusive, final and binding nature of a

conciliation agreement, which is the critical foundation for

the EEOC’s conciliation power. In sum, the Congressional

intent that the EEOC should have but one effective power,

the power of conciliation, will be frustrated if this Court

recognizes any continuing concurrent jurisdiction over the

subject matter of the Conciliation Agreement contrary to

the terms of the Agreement.

B.

The Appellants Made a Binding Election of Remedies

When They Chose to Accept the Benefits of a Concdia-

tion Agreement in Settlement of the Discriminatory Em

ployment Practices Charges.

The Court below observed and found the following: The

allegations of that complaint were made the subject of a con-

11

ciliation agreement which was later approved by the Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission and signed by all par

ties to the present suit on January 30, 1966. This agreement,

which was entered into for the purpose of settling the disputes

between these parties provided, inter alia, ‘that the Commis

sion, on request of any charging party or on its own motion,

may review compliance with this agreement’ and it further

provided that ‘The Charging Party hereby waives, releases

and covenants not to sue any respondent with respect to any

matters which were or might have been alleged as charges

filed with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission,

subject to performance by the respondents of the promises

and representations contained herein. The Commission shall

determine whether the respondents have complied with the

terms of this agreement.” (R52a)

The content of the discrimination charges and the settle

ment thereof, the Conciliation Agreement, embraces the very

same subject matter as does this suit (see Exhibit A to Com

plaint— R17a-R22a). Prior to the entrance into the Concilia

tion Agreement, the Appellants could have elected to pursue

their charges in Federal Court; they were in no way restricted

in their choice of forums. They could have elected to use the

conciliation “forum” to try to gain all they wished, and then

abandoned the forum if it proved unsuccessful. There was

no obligation upon the Appellants to accept anything that was

placed before them in conciliation effort; and, again, they could

have proceeded to court at any time up to the signing the

Conciliation Agreement to pursue whatever entitlements they

believed due them. However, Appellants not only elected the

forum of conciliation but elected to agree to the terms of the

conciliation as dispositive of the discrimination dispute and

specifically waived their right to sue on the matter. Such

12

agreement was reduced to writing in the Conciliation Agree

ment in issue in this matter. The Appellants executed the Con

ciliation Agreement, accepted the promises of the Agreement

as well as the benefits that flowed therefrom. By so electing

and accepting the benefits of the Conciliation Agreement,

Appellants made a final and binding election of remedies.

The election of remedies bar is not novel to the courts

under the Civil Rights Act. The matter recently arose in

Washington v. Aerojet General Corp., 282 F. Supp. 517 (C.D.,

Cal., 1968). In this case the grievant, as in the Appellants’

case, elected a forum different from the Federal Courts the

grievance procedure of a collective bargaining agreement. The

Judge therein found that the concurrent jurisdiction of the

grievance procedure and that established by statute in no way

restricted the plaintiff to a choice of forums. So far as the

Court was concerned, an individual could concurrently pursue

his remedies in both forums— but must eventually elect one

forum, to the exclusion of all others, from which to accept his

remedy. Such eventually in the Washington case was found

to be at that point where the plaintiff accepted the company-

union settlement in the third step of the grievance procedure

and returned to work. The common sense, reasonableness, and

equity of the election rule was reflected upon by the Court in

Washington: “ Such a rule is not only consonant with that

applied in an analogous area, but also will contribute to the

expeditious resolution of disputes in the equal employment

area and promote the sound and equitable administration of

justice by precluding an aggrieved party from subjecting a

defendant to multiple actions based upon the same claim.”

(282 F. Supp. 517, 523) The “ sound and equitable admin

istration of justice” to which the Court referred in Washing

ton has equal application in the matter before this Court. The

13

technique of absorbing the benefits of the accepted settlement

of the first forum, only to repudiate the settlement (but not

the benefits flowing therefrom) in an attempt to enlarge upon

the settlement of the second forum cries for denial of juris

diction in the second forum. The gross inequity and bad faith

involved in the repudiation of accepted agreements by the

plaintiff in the Washington case and by the Appellants in this

case are implicit.

C.

The Acceptance of the Benefits of the Conciliation Agree

ment and the Repudiation of Their Promises Exchanged

for Such Benefits Estop the Appellants from Herein

Seeking Enlarged Remedies from the Same Set of Facts.

The concept of equitable estoppel is the most penetrating,

dispositive principle of either law or equity that is applicable

in this matter. It can be logically and persuasively argued

that the Appellants should be precluded, both at law and at

equity, from asserting any right which they may at one time

have had against the Appellees— if the Appellees have in fact

relied upon the Appellants’ conduct in good faith and have

been thereby led to change their position “for the worse.”

Applying the principle to the instant case, the Appellants orig

inally made a charge of discrimination in employment against

the Appellees and the truth of the matter reached no further

than a “ reasonable cause to believe” stage with the EEOC.

But, pursuant to this undetermined right under the Civil

Rights Act— little more than a bare allegation— the Appellees

participated with the Appellants and the EEOC in a concili

ation effort to resolve the discrimination charge. Pursuant

14

to such efforts an agreement was reached and reduced into

the Conciliation Agreement in issue in this case. Such Con

ciliation Agreement required the changing of position by the

Appellees to their detriment and to the benefit of the Appel

lants in exchange for the Appellants’ commitment that “The

charging party hereby waives, releases and covenants not to

sue any respondent with respect to any matters which were or

might have been alleged in charges filed with the EEOC . . .

The Appellants thereafter accepted the benefits that flowed

from the Conciliation Agreement and will hereafter continue

to benefit therefrom for so long as they are employed by the

Appellee company at its Baton Rouge plant.

It can’t be emphasized too much that the Appellee com

pany was never determined to be in violation of the Civil

Rights Act— it was only found upon the barest of investiga

tive efforts that “ reasonable cause” existed to believe that em

ployment discrimination existed at the Baton Rouge plant.

(As a matter of law the Appellee company did not and does

not believe that a violation of the Civil Rights Act ever existed

at the Baton Rouge plant— either in 1965 or thereafter.) But

even though the charges raised by the Appellants did not, in

the opinion of the Appellee company, have legal substance,

they did have sufficient moral justification to warrant con

sideration and changes in the working conditions at the Baton

Rouge plant. The Appellees therefore entered into Conciliation

with the Appellants under the guidance and direction of the

EEOC. A fter difficult and extensive efforts on the part of all

involved, a Conciliation Agreement was reached to which all

parties were in concert: certain working conditions, seniority,

and employment approaches were changed by the Appellees

in exchange for a final and binding resolution of the sub

stance of the charges raised by the Appellants. The signifi

15

cance of the word “exchange” in reaching the final Concili

ation Agreement is the key to equitable estoppel. It must be

accepted as unthinkable in either equity or law that one party

to an agreement should benefit therefrom while repudiating

the agreement and his duty to fulfill his exchange promise.

The exchange of substantial and meaningful change in em

ployment conditions for a final and binding settlement that

is neither final nor binding is no exchange at all. Considera

tion must flow between the parties to any agreement if, in the

eyes of the law, any real agreement is ever to occur. There

fore, unless the Conciliation Agreement is found by this Court

to be final and binding as to all it purports to embrace, and

as its terms provide and as the Appellants agreed, then (1)

the Conciliation Agreement is a sham, (2) the Appellants have

fraudulently benefited at the expense of the Appellees, and

(3) repudiation of voluntary settlements in the area of civil

rights is encouraged.

The Court herein, is of course passing not only upon the

power of the EEOC to render conciliation agreements final

and binding but also upon the opportunities of those who bene

fit from conciliation agreements or voluntary settlement to

unjustly repudiate their exchanged commitment in an effort

to “get more.” Those who believe and hold that the very

nature and fibre of agreements before the law is mutuality

of obligation cannot help but be offended by the “dirty hands”

with which the Appellants have approached the Court below

as well as this Court. In the interest of justice, equity, and

the continued vitality and effectiveness of the EEOC, this

Court is urged to recognize that it has been preempted by the

Appellants’ own acceptance of the Conciliation Agreement as

its remedy in the substantive matter the Appellees bring be

fore the Federal Courts.

16

CONCLUSION

For the above discussed reasons, it is submitted that this

matter was properly dismissed for lack of jurisdiction by the

court below, which ruling must be affirmed as correct.

Respectfully submitted,

Taylor, Porter, Brooks, Fuller & Phillips

Attorneys for Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical

Corporation, Defendant-Appellee

F. W. Middleton, Jr.

Louisiana National Bank Building

451 Florida Boulevard

Baton Rouge, Louisiana 70821

Of Counsel

Robert P. Tiernan

300 Lakeside Drive

Oakland, California 94604

17

CERTIFICATE

I certify that a copy of the foregoing brief has been this

day mailed, postage prepaid, to the following:

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, I I I

Robert Belton

Gabrielle A. Kirk

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Murphy Bell

214 East Boulevard

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

Albert J. Rosenthal

435 West 116th Street

New York, New York 10027

Baton Rouge, Louisiana, th is_____day of December, 1968.

F. W. Middleton, Jr.

Ta y l o r , Po r t e r , Br o o k s , Fu ll e r & Phillips

A t t o r n e y s a t L a wLa u r a n c e W. Br o o k s

Ch a r le s W. P h il l ip s

W ill iam C. Ra n d o l p h

Ben B .Ta y l o r ,J p .

Fr a n k W. M id d le to n , J r .

Ro b e r t J. Va n d a w o r l e r

T om F. P hili ip s

David M-El l is o n , J r .

Fr a n k M.Co a t e s , J r .

J o h n I, Mo o r e

W illiam H. Mc Cl e n d o n , III

W illiam A -N o r f o l k

W ill iam S h e lb y McKenzie

J o h n S. Ca m p b e l l , J r .

Ro b e r t H. Ho d g e s

L o u is ia n a Na t io n a l Ba n k B u il d in g

P o s t O m c r . Draw er 2471

B a t o n R o u g e , L o u i s i a n a 7oe2i

A rea Code 5G4

Te l e ph o n e 348-3221

B e n j a m i n 8 - T a y l o r (i b o s - i q s ©)

C h a r l e s V e r n o n Po r t e r { laes -r aez }

J a m e s R. F u l l e r

Cou nsel

December 30, 1968

The Honorable. Edward W. Wadsworth

Clerk, U. S. Court of Appeals

Fifth Circuit

Room 408, 400 Royal Street

New Orleans, Louisiana 70130

Re: No. 26893 - A. J. Burrell, et al vs.

Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical Corporation, et al

Dear Sir:

Enclosed are twenty copies of a printed brief in the above captioned matter,

which we request that you file on behalf of Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical

Corporation.

I am executing certificate of service on opposing counsel in the form printed

with the brief.

Yours very truly,

FWM/ec

Enel.

cc: Mr. Jack Greenberg

Mr. James M. Nabrit, III

Mr. Robert Belton

Mr. Gabrielle A. Kirk

Mr. Murphy Bell

Mr. Albert J. Rosenthal

Mr. C. Paul. Barker

Mr. Herbert S. Thatcher

Mr. Robert P. Tiernan

Mr. J. J. Durney