Missouri v. Jenkins Brief in Opposition of Respondent

Public Court Documents

October 28, 1991

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Missouri v. Jenkins Brief in Opposition of Respondent, 1991. 41ffddf3-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1b3e2ab1-ed48-4744-bb98-6073b0ca69e3/missouri-v-jenkins-brief-in-opposition-of-respondent. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

'S

8

□

□

"

8

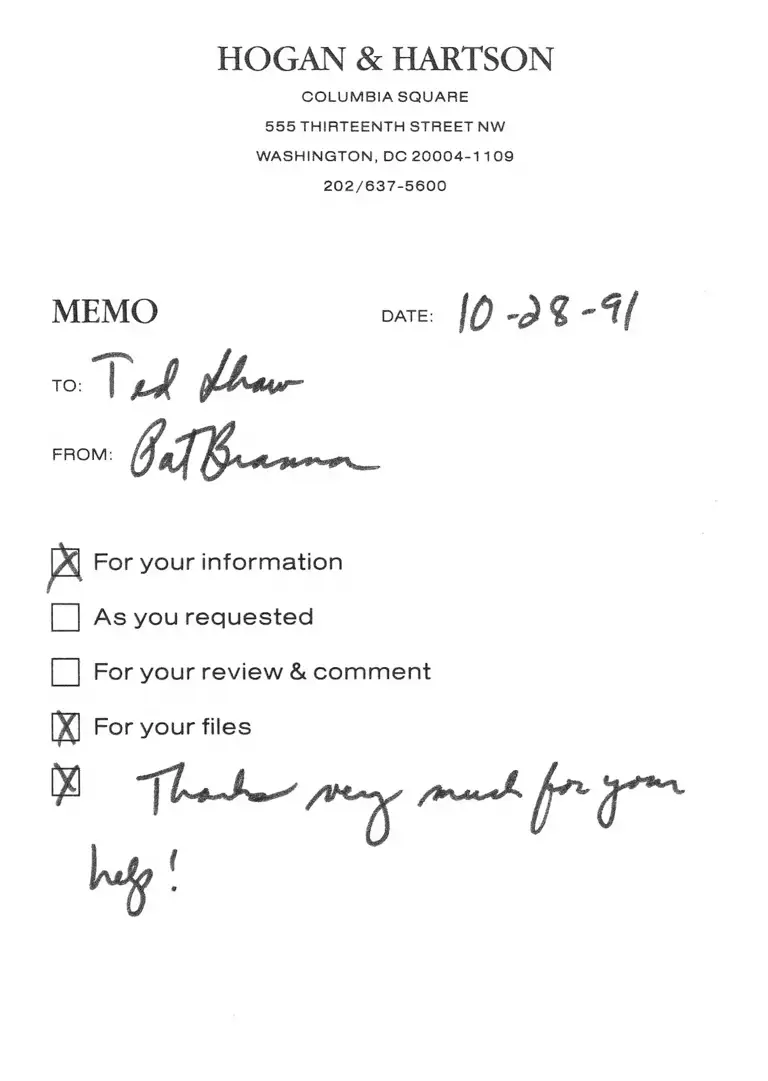

HOGAN & HARTSON

C O L U M B IA SQUARE

5 5 5 THIRTEENTH STREET NW

W A S H IN G T O N , DC 2 0 0 0 4 -1 1 09

2 0 2 /6 3 7 - 5 6 0 0

MEMO

| jlJTO:

FR O M : $ * % $ * * * * »

DATE: \ o-n -v

For yo u r in fo rm a tio n

A s you re q u e s te d

For y o u r re v ie w & c o m m e n t

For y o u r files

/&%****&■* (jf

No. 91-324

I n T h e

Btxpnm (Errurt uf tit? Ittftpfc §tatra

October T e r m , 1991

State of M issouri, et al.,

Petitioners, v. ’

K alim a Je n k in s , et al,,

_________ Respondents.

On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals

for the Eighth Circuit

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION OF RESPONDENT

KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI SCHOOL DISTRICT

A llen R. Snyder *

Patricia A. Brannan

Hogan & Hartson

555 Thirteenth St., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20004

(202) 637-5741

Shirley W ard Keeler

Michael Thompson

Blackwell Sanders Matheny

W eary and Lombardi

Two Pershing Square

2300 Main Street

Kansas City, Missouri 64141

(816) 274-6816

* Counsel of Record

W ilson - Efes Printing Co . . Inc . - 7 8 9 -0 0 9 6 - W a s h in g t o n . D .C . 2 0 0 0 1

COUNTERSTATEMENT OF QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Whether the courts below acted well within their

equitable discretion to modify a desegregation plan, the

scope of which this Court has declined to review, by as

suring that as part of capital improvements necessary to

make schools sufficiently safe, healthy and suitable for

desegregation programs asbestos hazards would he abated

to the extent required by federal law.

2. Whether the courts below similarly acted well within

their equitable discretion to modify the desegregation plan

by adjusting the budget required for the construction of

a single high school, where the record at an evidentiary

hearing demonstrated that errors in the original budget

estimate, and new information about the actual costs of

construction, necessitated a revised budget.

( i )

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

COUNTERSTATEMENT OF QUESTIONS PRE

SENTED...... ........... ............... ... ............................... ... i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES .................................. ....... iv

COUNTERSTATEMENT OF THE CA SE....... ........... 1

A. Liability and Initial Remedy Proceedings______ 1

B. The Orders at Issue ............... .......... .............. . 8

1. The Asbestos Order............ ..... .................. . 8

2. The Central High School Order ................ . 12

REASONS FOR DENYING THE WRIT ___________ 15

I. REVIEW OF THE COST OF CENTRAL HIGH

SCHOOL AND ASBESTOS ABATEMENT

WOULD BE INAPPROPRIATE UNDER THIS

COURT’S STANDARDS FOR GRANTING A

PETITION FOR CERTIORARI................. ........ 16

II. EVEN IF THE PETITION PRESENTED THE

ISSUE OF THE OVERALL SCOPE OF THE

DESEGREGATION REMEDY IN KANSAS

CITY, THE COURT SHOULD DECLINE RE

VIEW BECAUSE IT HAS PERMITTED THAT

REMEDY TO GO FORWARD WHEN THE

SCOPE ISSUE WAS PREVIOUSLY PRE

SENTED ....... ........... ....... ................................. .... 22

CONCLUSION ................ ....................... ........................ . 28

(hi)

IV

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Page

Aetna Life Insurance Co. v. Haworth, 300 U.S. 227

(1937) ................ ..,....... .................... ................... . 21

Anderson v. Bessemer City, 470 U.S. 564 (1985).... 15

Berkemer v. McCarty, 468 U.S. 420 (1984) ........ 23

Board of Education of Oklahoma City Public

Schools v. Dowell,------ U.S.------- , 111 S. Ct. 630

(1991) ........... 23,26

Booker v. Special School Dist. No. 1, 585 F.2d 347

(8th Cir. 1978), cert, denied, 443 U.S. 915

(1979)....... .......... ........... ................ ......... ....... 14, 19

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294

(1955) ............ 19

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483

(1954)___________ 7

Christianson v. Colt Industries Operating Corp.,

486 U.S. 800 (1988) ........... ....................... ........... 5

Deakins v. Monaghan, 484 U.S. 193 (1988) _____ 21

Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co., 482 U.S. 656 (1987).. 18

Graver Tank & Mfg. Co. v. Linde Air Products Co.,

336 U.S. 271 (1978) ....... ...... ....... .......... ........... . 18

Green v. New Kent County School Board, 391 U.S.

430 (1968) ............................ ................ ......... . 26

Jenkins v. Missouri, 855 F.2d 1295 (8th Cir. 1988),

cert, denied in relevant part, 490 U.S. 1034

(1989) ........ ........... ... ...... ................. ...................7, i i , 16

Jenkins v. Missouri, 807 F.2d 657 (8th Cir. 1986)

{en banc), cert, denied, 484 U.S. 816 (1987)____4, 5,16

Jenkins v. Missouri, 672 F. Supp. 400 (W.D. Mo.

1987), aff’d, 855 F.2d 1295 (8th Cir. 1988),

cert, denied in relevant part, 490 U.S. 1034

(1989)..................................... .............. ............. . 6, 7

Jenkins v. Missouri, 639 F. Supp. 19 (W.D. Mo.

1986), aff’d, 855 F.2d 1295 (8th Cir. 1988),

cert, denied in relevant part, 490 U.S. 1034

(1989)..................... ............ .......... .............. ..... . 6

Jenkins v. Missouri, 639 F. Supp. 19 (W.D. Mo.

1985), aff’d, 807 F.2d 657 (8th Cir. 1986) {en

banc), cert, denied, 484 U.S. 816 (1987) ....... . 2-4, 9

V

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page

Jenkins v. Missouri, 593 F. Supp. 1485 (W.D. Mo.

1984).............................. ......................... ...... ........ 2

Lewis v. Continental Bank Corp., 494 U.S. 472,

110 S. Ct. 1249 (1990)_______ ______ _______ _ 21

Mapp v. Board of Education, 477 F.2d 851 (6th

Cir.), cert, denied, 414 U.S. 1022 (1973)....... 19

Milliken v. Bradley, 433 U.S. 267 (1977) ............... 18-19

Missouri v. Jenkins, 495 U.S. 33, 110 S. Ct. 1651

(1990) ___ _____ ___ ______ ______ _____ _________ 8

NCAA v. Board of Regents, 468 U.S. 85 (1984).... 18

North Carolina v. Rice, 404 U.S. 244 (1971) .... .... 21

Rogers v. Lodge, 458 U.S. 613 (1982) ........ .............. . 18

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Educa

tion, 402 U.S. 1 (1971) ............... ............... ......... 19

Tiffany Fine Arts, Inc. v. United States, 469 U.S.

310 (1985) _____ _______________ ___________ .... 18

United States v. Ceccolini, 435 U.S. 268 (1978).... 18

United States v. Montgomery County Board of

Education, 395 U.S. 225 (1969)............... ............... 18

Statutes:

Asbestos Hazard Emergency Response Act of 1986

(“AHERA” ) , 15 U.S.C. §§ 2641-2654 (1988)..... 9-11,

19-20

Rules:

Fed.R. Civ. P. 52(a) ................ ................................. 15

Sup. C t.R .21.1(a)................ .................... ....... ....... 23

In T he

Bupmm (&mrt nf % Unikb Btnt?b

October T erm , 1991

No. 91-324

State of M issouri, et at.,

Petitioners, v. ’

K alim a Je n k in s , et at.,

Respondents.

On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals

for the Eighth Circuit

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION OF RESPONDENT

KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI SCHOOL DISTRICT 1

COUNTERSTATEMENT OF THE CASE

A. Liability and Initial Remedy Proceedings.

After a 92-day trial on interdistrict and intradistrict

desegregation claims brought by the Jenkins plaintiff

class of schoolchildren and the Kansas City, Missouri

School District (“ KCMSD” ),2 on September 17, 1984 the

district court (The Honorable Russell G. Clark) found

that “ [t]he people of the State of Missouri through eon-

1 The Kansas City, Missouri School District respondents include

the school district itself and its Superintendent.

2 The KCMSD originally filed the complaint in 1977 against State

of Missouri defendants and a group of surrounding school districts.

The KCMSD was re-aligned as a defendant and separate counsel was

retained to represent the plaintiff schoolchildren. Trial proceeded

both on the claims of the Jenkins plaintiff class and KCMSD’s cross

claims against the State. The district court granted the motions to

dismiss of the surrounding school districts on June 5, 1984.

2

stitutional provision and the General Assembly through

legislative enactments mandated that all schools for blacks

and whites in th[e] State were to be separate” in viola

tion of the Fourteenth Amendment, and that “ the inferior

education indigenous of the state-compelled dual school

system has lingering effects in the Kansas City, Missouri

School District.” Jenkins v. Missouri, 598 F. Supp. 1485,

1503-04, 1492 (W.D. Mo. 1984). With these liability

findings, uncontested by the State, the parties and dis

trict court began the development of the remedy for this

violation.

The State and the KCMSD submitted proposed desegre

gation plans, and Judge Clark held two weeks of hearings

that resulted in his initial remedial order of June 14,

1985. The plan adopted by the district court had four

key components designed both to achieve actual desegrega

tion and to restore the black schoolchildren who were the

victims of segregation to the position they would have

occupied in the absence of discriminatory conduct. First,

Judge Clark approved educational programs “designed

to increase student achievement” because segregation had

“ caused a systemwide reduction in student achievement

in the schools of the KCMSD.” Jenkins v. Missouri, 639

F. Supp. 19, 25, 24 (W.D. Mo. 1985) (emphasis in orig

inal), aff’d, 807 F.2d 657 (8th Cir. 1986) (en banc),

cert, denied, 484 U.S. 816 (1987). KCMSD, the plain

tiff schoolchildren, and the State all had supported in

clusion of educational components in the remedy. Jen

kins, 639 F. Supp. at 24.

The second remedial component approved by the court

was the use of magnet schools to draw new non-minority

enrollment to the KCMSD, to encourage voluntary de-

segregative transfers within the school district, and to

make better educational opportunities available to mi

nority as well as non-minority students in the district.

Id. at 34. Judge Clark specifically found that magnet

schools which would draw a voluntarily desegregated

enrollment based on a special theme or method of teach-

3

mg held better promise of achieving actual desegrega

tion than the State’s preferred method of mandatory

student reassignment and busing, which would “ only

serve to increase the instability of the KCMSD and reduce

the potential for desegregation.” Id. at 38. As a third

component of the remedy, Judge Clark ordered the State

to seek the active cooperation of surrounding school dis

tricts in a voluntary interdistrict transfer program. Id.

at 38-39. The voluntary enrollment of non-minority stu

dents from area districts in KCMSD magnet schools, and

the opening of opportunities for minority students from

KCMSD to attend integrated suburban schools, was found

by the district court to be an appropriate remedial com

ponent because of the difficulty of desegregating the

KCMSD, which had become nearly 70 percent black and

had an enrollment of 90 percent or more black in 25 of

its 66 schools. Id. at 39, 36. That component of the

remedy, and the remedial goal of attracting non-minority

students from outside the KCMSD back to its magnet

schools on a voluntary basis, also was responsive to the

district court’s findings that “ segregated schools, a con

stitutional violation, ha[ve] led to white flight from the

KCMSD to suburban districts, large number [s] of stu

dents leaving the schools of Kansas City and attending

private schools and that . . . has caused a system

wide reduction in student achievement in the schools of

KCMSD.” Aug. 25, 1986 Order at 1-2.3

The court also approved as a fourth component of the

remedy a program of capital improvements, because

“ [t]he current condition of the . . . school facilities * 4

3 The State’s Petition contends that “ the plaintiffs . . . proved

neither an interdistrict violation nor an interdistrict effect.” Pet. at

4. The respects in which the remedy provides for voluntary inter-

district desegregation are fully supported by Judge Clark’s orders,

including the August 25, 1986 Order quoted in text, and by the

extensive evidence presented in the liability case that the violation

had significant interdistrict aspects. That evidence is described in

the Brief in Opposition of Respondents Kalima Jenkins, et al, at

the Counter-Statement of the Case.

4

adversely affects the learning environment and serves

to discourage parents who might otherwise enroll their

children in the KCMSD . . . .” 639 F. Supp. at 39. Judge

Clark recounted the evidence of “safety and health haz

ards, educational environment impairments, functional

impairments, and appearance impairments” in the schools,

id., and concluded that “ improvement of school facilities

is an important factor in the overall success of this de

segregation plan.” Id. at 40.

On cross appeals to the United States Court of Appeals

for the Eighth Circuit, KCMSD and the Jenkins plaintiffs

argued that the district court erred in the legal standard

that it applied to dismiss the surrounding suburban school

districts, while the State questioned “what the vestiges of

th[e] dual school system are 30 years after it was de

clared void and what constitutes a proper remedy to elim

inate those vestiges.” Brief of State Appellees/Cross

Appellants at 40 (No. 85-1765WM, et al.) (filed Sept.

23, 1985). The State also attacked some components of

the remedy, particularly components for which the dis

trict court set funding allocations that required most of

the cost to be paid by the State.4 With regard to the

voluntary interdistrict transfer plan, the State argued

“that an order requiring support of an exchange pro

gram between numerous school districts, based solely

upon a violation in one of those districts, imposes an

interdistrict remedy for an intradistrict violation.” Id.

at 54.

The Eighth Circuit affirmed the dismissal of the sur

rounding school districts and made modest alterations in

the allocation of funding for the remedy, but affirmed 4

4 As the Eighth Circuit observed, “ [n,]o one challenge [d] the sub

stantial portion [of the remedy] in which the costs are divided

evenly between the State and the KCMSD.” Jenkins v. Missouri,

807 F.2d 657, 682 (8th Cir. 1986) (en banc), cert, denied, 484 U.S.

816 (1987). Those portions of the remedy included most of the

components designed to improve educational achievement and the

holding that magnet schools would be the basis in the remedy for

student reassignment.

5

the inclusion of a voluntary interdistrict transfer com

ponent and capital facilities improvements in the remedy.

The Eighth Circuit specifically held that an interdistrict

transfer plan, on a voluntary basis, is an appropriate

part of a remedy where liability against the State has

been established because such transfers would assist in

the achievement of desegregation within the KCMSD.

Jenkins, 807 F.2d at 683-84. The court reiterated, how

ever, that a mandatory interdistrict remedy (such as

consolidation of school districts or mandatory assign

ment of students across school district lines) would be

outside the scope of the violation found by the district

court and thus beyond the district court’s power. Id. at

683 n.30. With respect to capital facilities, the Eighth

Circuit further held that the district court’s findings of

hazards in the schools that impede attraction of students

and obstruct the success of the educational programs in

cluded in the remedy were “ sufficient to support its con

clusion that capital improvements are necessary for suc

cessful desegregation.” Id. at 685. The court went on,

however, to reallocate funding responsibility for capital

improvements on an equal basis between the State and

the KCMSD, rather than requiring the State to pay most

of the cost. Id.

The KCMSD and Jenkins plaintiffs petitioned this

Court for a writ of certiorari to review the legal basis

of the Eighth Circuit’s affirmance of the dismissal of the

surrounding school districts. This Court denied certiorari.

484 U.S. 816 (1987). No cross-petition was filed by the

State on the scope of remedy issues it raised in the Eighth

Circuit. The order setting the initial scope of the remedy,

with the modest modifications made by the Eighth Circuit,

thus became the law of the case. See Christianson v. Colt

Industries Operating Corp., 486 U.S. 800, 816 (1988).

Because no party had sought a stay of implementation

during the pendency of the proceedings, the implementa

tion of the remedy began at the start of the 1985-86

school year.

6

Over the six years since the implementation of the

remedy began, the district court has entered numer

ous orders clarifying, renewing, or setting specific param

eters on the remedial components. Of greatest note, on

June 16, 1986, the district court approved for fall of 1986-

87 the opening of an initial group of six magnet schools,

and on November 12, 1986, ordered a Long-Range Magnet

School Plan that was to be phased in over a six-year

period. Each of these orders also provided for capital

facility improvements to accommodate the special needs

of the magnet school programs and to bring the schools

up to an acceptable level of safety, health and appro

priateness for educational programs. Jenkins v. Missouri,

639 F. Supp. 19, 53-55 (W.D. Mo. 1986), aff’d, 855 F.2d

1295 (8th Cir. 1988), cert, denied in relevant part, 490

U.S. 1034 (1989) ; Jenkins v. Missouri No. 77-0420-

CV-W-4, slip op. at 4 (W.D. Mo. Nov. 12, 1986).

On September 15, 1987, the district court approved a

Long-Range Capital Improvements Plan to implement a

significant part of the remaining capital needs to make

KCMSD schools sufficiently safe, healthy, comfortable

and attractive for both the magnet school programs and

for the desegregation educational programs. The court

specifically found that KCMSD’s “physical facilities have

literally rotted” and that the “overall condition” of the

schools remained “ generally depressing and thus adversely

affects the learning environment and continues to dis

courage parents who might otherwise enroll their children

in the KCMSD.” Jenkins v. Missouri, 672 F. Supp. 400,

411, 403 (W.D. Mo. 1987), aff’d, 855 F.2d 1295 (8th

Cir. 1988), cert, denied in relevant part, 490 U.S. 1034

(1989). The district court premised this order on two

findings. First, the court found that the State’s manda

tory segregation had caused these “ rott[ingj” physical

conditions, since large numbers of white taxpayers with

children, who previously had contributed to the majori

ties needed to pass levy increases and bond elections, left

the district, thereby “preventing] the KCMSD from

raising funds to maintain its schools.” 672 F. Supp. at

7

411, 403, citing November 12, 1986 Order at 4. Second,

the court found that “ a long-range capital improvement

plan aimed at eliminating the substandard conditions

present in KCMSD schools is properly a desegregation

expense and is crucial to the overall success of the de

segregation plan.” Id. at 403 (emphasis added).

The State appealed these three orders to the Eighth

Circuit, once again arguing strenuously that the orders

exceeded the district court’s equitable discretion because

the State believed they went beyond the bounds of the

violation that the district court found. Once again, the

Eighth Circuit affirmed. Jenkins v. Missouri, 855 F.2d

1295, 1299-1300 (8th Cir. 1988), cert, denied in relevant

part, 490 U.S. 1034 (1989). The Eighth Circuit based its

affirmance on the principle that “ the victims of unconstitu

tional segregation must be made whole, and . . . to make

them whole it will be necessary to improve their educa

tional opportunities and reduce their racial isolation.”

Id. at 1301. The court further affirmed the capital im

provements plan, based on the district court’s “ findings”

that the constitutional violations of “both KCMSD and

the State had caused the decay of the KCMSD’s build

ings.” Id. at 1300. The court recognized that “ [t]he

foundation of the plans adopted was the idea that im

proving the KCMSD as a system would at the same time

compensate the blacks for the education they had been

denied and attract whites from within and without the

KCMSD to formerly black schools.” Id. at 1301. The

court went on to affirm as modified a procedure by which

local property taxes could be raised to pay the KCMSD’s

share of the remedy that both it and the district court

had found to be constitutionally required. Id. at 1308-15.

The State petitioned this Court for a writ of certiorari

to review two questions presented by the Eighth Circuit’s

affirmance:

1. Whether a federal court, remedying an intra-

district violation under Brown v. Board of Edu

cation, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), may

8

a) impose a duty to attract additional non

minority students to a school district, and

b) require improvements to make the district

schools comparable to those in surrounding

districts.

2. Whether a federal court has the power under

Article III, consistent with the Tenth Amendment

and principles of comity, to impose a tax increase

on citizens of a local school district.

See 57 U.S.L.W. 8577 (Feb. 28, 1989) (No. 88-1150).

This Court granted the petition to review the second

question only. 490 U.S. 1034 (1989). The decision on

the merits, issued on April 18, 1990, addressed only the

issue of whether the tax orders of the district court and

the court of appeals exceeded their equitable and consti

tutional power. Missouri v. Jenkins, 495 U.S. 33, ------ ,

110 S. Ct. 1651, 1660 (1990) (“ [w]e granted the State’s

petition, limited to the question of the property tax in

crease . . . .” ). The magnet school and capital improve

ment orders thus have been in the process of implemen

tation since the district court’s orders were issued in 1986

and 1987.

B. The Orders at Issue.

The two particular orders at issue in the State’s peti

tion for certiorari are among a series of orders by the

district court that have made modifications in the de

segregation plan in the course of implementation, based

on experience and further information that has become

available.

1. The Asbestos Order.

The Long-Range Capital Improvements Plan and the

earlier capital improvements ordered for the initial stages

of the magnet school plan all contemplated that some

asbestos abatement would be done as part of the renova

tion work at District schools. The district court originally

so ordered because it held that “ a school facility which

9

presents safety and health hazards to its students and

faculty serves both as an obstacle to education as well as

to maintaining and attracting non-minority enrollment.”

639 F. Supp. at 40. In fact, the State's own proposed

capital improvement plan, which the district court re

jected because it was inadequate in other respects, ac

knowledged that asbestos abatement necessarily would

have to be part of the desegregation-related work and

provided budget estimates for that work.5

The cost of asbestos abatement was particularly diffi

cult to specify with certainty in advance of each project.

This is true because it generally cannot be known until

a renovation project begins precisely where asbestos will

be found and what means will be necessary to abate it.

The record also shows that other desegregation-related

capital improvement plan work, such as knocking out

walls to enlarge learning spaces and opening walls to

gain access to decrepit pipes and electrical wiring, has

created a need for asbestos abatement that otherwise

would not exist.6

Moreover, on October 30, 1987, the United States En

vironmental Protection Agency published final rules pur

suant to the Asbestos Hazard Emergency Response Act

of 1986 (“AHERA” ), 15 U.S.C. §§ 2641-2654 (1988),

establishing strict standards for maintaining environments

free of asbestos hazards. The rules went into effect on

December 14, 1987. 52 Fed. Reg. 41826 (Oct. 30, 1987).

Thus the actual work done by KCMSD under the capital

improvements plan had to comply with the new, stricter

standards; the inspections originally conducted by the

KCMSD for the presence of asbestos in its facilities and

the less expensive methods KCMSD originally contem

6 See State’s Ex. 9, Tr. Vol. VI at 64 (Aug. 11,1987).

6 See Declaration of Don M. Powers, in support of KCMSD Motion

for Increased Funding for CIP Asbestos Abatement Costs (filed

Dec. 7, 1988), ft 3.

plated for handling asbestos abatement were no longer

consistent with federal law.7

By late in 1988, the KCMSD had completed asbestos

abatement work and knew the necessary costs for the first

six magnet schools that had opened in the KCMSD. The

KCMSD moved the district court for approval of the

asbestos abatement costs in excess of its original esti

mates for those six schools— some $910,224— as a de

segregation cost required to meet federal health and

safety standards in regard to the work that remedying

the constitutional violations required in the KCMSD’s

school buildings. It also sought court approval of the

use of AHERA standards as an appropriate guideline

for the KCMSD’s future renovation of school buildings

to make them available and suitable for desegregation

programs.8

The State opposed the District’s motion, contending

that asbestos abatement is not a desegregation expense,

but it produced no evidence challenging the facts that

the renovations otherwise necessitated by the constitu

tional remedy in turn necessitated asbestos abatement

for the health and safety of children in KCMSD schools.9

The record showed, to the contrary, that the renovations

required to remedy the violation would dislodge asbestos-

containing materials, and once they did, AHERA would

require a level of abatement as a matter of federal law

that was more stringent than originally contemplated by

the KCMSD when it prepared its estimated budgets for

capital improvements. Although one of the State’s major

7 See Declaration of Walter Houston, in support of KCMSD Mo

tion for Increased Funding for CIP Asbestos Abatement Costs (filed

Dec. 7, 1988), If 3.

8 The State’s Petition at page 11 confuses the schools and amounts

involved in the KCMSD’s motion. The $910,224 increase was for the

six schools in “ Phase III” of the capital improvements plan; the

Phase III increase requested was not in addition to the $910,224.

9 See State’s Response to KCMSD Motion for Increased Funding

for CIP Asbestos Abatement Costs (filed Jan. 5, 1989).

10

11

arguments was that school districts generally have to

comply with AHERA so the costs of compliance should

not be a desegregation expense, it produced no evidence

to counter the KCMSD’s proof that the cost in the KCMSD

was extraordinary because the asbestos-containing ma

terials would not have been dislodged had the consti

tutional violations not required desegregation-related cap

ital improvements work that the court ordered.10

The district court granted the KCMSD’s motion, with

some modifications in the requested allocation of costs

between KCMSD and the State. The district court noted

that the Eighth Circuit, in its affirmance of the scope of

the capital improvements plan, already had anticipated

that “ ‘the capital plan that we affirm today does not

cover all expenditures that may be necessary between now

and the 1991-92 school year [including some] asbestos

removal costs.’ ” Pet. App. A-56, quoting Jenkins, 855

F.2d at 1306.11

On the State’s appeal to the Eighth Circuit, that Court

affirmed, citing the uncontested evidence that achieving

an acceptable level of health and safety was an appropri

ate goal for capital improvements in a desegregation

plan, that asbestos abatement was vital to health and

safety, and that “ the evidence in the record . . . differ

entiates this situation from situations found at other

school districts, or for that matter any other public build

ings” because “many asbestos-containing products that

normally would pose no danger (such as flooring), be

come potentially dangerous when disturbed during the

[court-ordered] renovation work” needed to remedy the

constitutional violations. Pet. App. A-25.

The State sought no stay of the district court order

pending appeal. The asbestos abatement work approved

10 Id.

11 We cite the State’s petition for writ of certiorari as “ Pet.” ; the

State’s Appendix in support of its petition as “ Pet. App.” ; and the

Joint Appendix from the Eighth Circuit Jenkins III Appeal, No. 89-

1838WM, reported at 855 F.2d 1295 (8th Cir. 1988) as “J.A.”

12

for the six magnet schools has been done, and the $910,-

224 budget increase for that work has been expended. In

fact, the vast majority of asbestos abatement called for

under the capital improvements plan is complete.

2. The Central High School Order.

When the Long-Range Magnet School Plan was pro

posed in 1986, Central High School was a virtually all

black school, located in the “central corridor” area of

Kansas City which is heavily minority. J.A. 2477-78,

988-89. It was at that time in the worst physical condi

tion of any KCMSD high school. J.A. 2388. Testimony

during the Long-Range Magnet School Plan hearing dem

onstrated that water damage, falling plaster and ceiling

tiles, worn out floors and peeling paint were prevalent

throughout the school. Testimony of Dr. Richard Hunter,

Volume II at 396-400 (Sept. 16, 1986). Dr. Hunter

stated that one could “ see daylight” through a hole in

the auditorium’s roof and “when it rains it just came

directly into the auditorium. Very depressing conditions

walking around the building, and a very poor educational

facility.” Id. at 399-400.

Among the initial capital facility projects approved for

magnet schools as part of the Long-Range Magnet School

Plan order was the construction of a new Central High

School. No party contested that a new building was neces

sary for reasons of safety, health, comfort and attractive

ness for educational programs, and for the special facili

ties needed to implement at Central both the Computers

Unlimited and Classical Greek magnet themes.12 The

approval of a new Central High School building thus

became final with the Eighth Circuit’s affirmance of the

12 The Computers Unlimited program offers computer-assisted in

struction and specialized courses involving computer technology,

while the Classical Greek program emphasizes development of “a

sound mind and a sound body” by combining a vigorous liberal arts

and classical studies curriculum with unique opportunities for

athletic training and physical education, including a focus on

Olympic events and activities. J.A. 596-98, 599-601.

13

November 12, 1986 Order, and this Court’s denial of

the State’s petition for certiorari to review that

affirmance.

As KCMSD developed the design for the new Central

High School, it became clear that the budget approved

by the courts below would not be adequate for the pro

gram requirements for the new facility. The budgets

originally presented to the district court by the KCMSD

were “based upon studied estimates” that the district court

held could be “ adjusted when the actual costs of the

capital facilities work and the magnet school plan ordered

by the Court are ascertained.” November 12, 1986 Order

at 6.

In September 1988, the KCMSD filed a motion asking

the district court to increase the construction budget for

Central to recognize the “actual costs” necessary for the

construction. After extensive discovery, the district court

held a three-day hearing. The court heard expert testi

mony by architects for both the KCMSD and the State,

the KCMSD’s construction project manager, and educa

tors, parents and community members involved in the

development of the programs at Central, or who con

templated sending their children to school there.

The district court approved the budget modification for

the construction of the new Central High School, exclud

ing the costs associated with a high diving tower.13 Pet.

App. A-46, A-50. The court carefully reviewed the basic

reasons why the original budget was inadequate: 1) a

flawed design assumption that certain enclosed athletic

facilities could be located inside an indoor track; 2) an

incorrect assumption about the appropriate design “ effi

ciency ratio,” or ratio of net program space to gross

building space; and 3) the erroneous omission of archi

18 In the same order the district court approved a site for Central

and a revision in the alignment of budget years and adjustment in

the cost of equipment for the school. Pet. App. A-50-A-52. The

State did not present evidence disputing those aspects of the Central

project.

14

tects’ and engineers’ fees, soil survey and testing and bid

advertising from the estimate. All of these issues were

the subject of discovery and hearing testimony by expert

architects and a construction manager. The court also

carefully reviewed the extensive evidence that the facili

ties proposed by the KCMSD for Central, particularly the

athletic facilities on which the court made findings on a

room-by-room basis, were necessary for the magnet school

theme. Pet. App. A-45-A-49. The State’s own witness

admitted, as the district court noted, that various facili

ties were appropriate to the program and would be at

tractive to a desegregated enrollment. Pet. App. A-46,

A-47. The court specifically found that “ [t]he magnet

programs could not be successfully implemented in a lesser

facility,” and that “ such facilities are necessary to attract

non-minority suburban students to the inner city to ac

complish the difficult task of desegregating Central High

School.” Pet. App. A-49. The court also reviewed the

uncontested evidence that the KCMSD made efforts to

remain within the original budgets, and that in the

course of so doing eliminated certain art, athletic and

music facilities from Central that also could be attractive

but that were not essential to the program. Pet. App.

A-49-A-50.

On an appeal taken by the State, the Eighth Circuit

affirmed. That court rejected the State’s argument that

the district court exceeded its authority in modifying its

earlier budget order for Central, because “a federal court

has ‘inherent jurisdiction in the exercise of its equitable

discretion and subject to appropriate appellate review

to vacate or modify its injunctions.’ ” Pet. App. A-32,

quoting Booker v. Special School Dist. No. 1, 585 F.2d

347, 352 (8th Cir. 1978), cert, denied, 443 U.S. 915

(1979). The court recognized that the original order

approved “ studied estimates to be adjusted as actual costs

were ascertained,” and the district court’s order demon

strated its careful consideration of the various facilities

proposed within the school. Pet. App. A-33. In particular,

the court pointed out that the State made no argument

15

that any of the district court’s findings were “ clearly

erroneous.” Pet. App. A-34; see Fed. R. Civ. P. 52(a).

Applying this Court’s standard in Andersooi v. Bessemer

City, 470 U.S. 564, 573-74 (1985), the court was “ con

vinced that the district court did not clearly err in finding

that the KCMSD’s design process was appropriate, that

the additions to the planned athletic facilities were justi

fied, that the allocated space of 200 square feet per stu

dent is necessary to implement the magnet themes and

enhance the school’s attractiveness to non-minority stu

dents, and that the increased construction and equipment

budgets are necessary to meet the design requirements.”

Pet. App. A-34.

Once again, no stay was sought or issued pending

appeal. In fact, the new Central High School building

was constructed and open to students on September 3,

1991. Nearly 200 non-minority students are now in the

Central High School student body, resulting in a 17.5

percent non-minority racial composition. This is a sig

nificant change from the all-minority student body that

Central had before it became a magnet school.

REASONS FOR DENYING THE WRIT

The decision which the State seeks to have this Court

review presents highly fact-bound, narrow, and technical

issues of the correct budget amounts for certain construc

tion activities as part of a desegregation plan. It is

extraordinary to contemplate the prospect of this Court

delving into the intricacies of building efficiency ratios,

the extent of appropriate asbestos abatement during

school renovations and the like. No conflict among the

circuits or important question of federal law is presented

by why it costs more than originally anticipated in 1986

or 1987 to build a new Central High School in 1990 and

1991, or why it costs more to abate asbestos during school

renovations after new federal regulations raised health

and safety standards for that work. Under the “two-

court rule,” the extensive fact findings that supported the

revised estimates should not be disturbed by this Court.

16

In any event, the issues the State asks the Court to re

view are moot, because Central High School is finished,

and received its new student body on September 3, 1991.

The asbestos work that was the subject of the $910,224

budget increase the State complains of has been per

formed. No decision of this Court could alter the scope

of what has been done in these projects.

In apparent recognition that the orders actually at

issue do not present questions worthy of the Court’s re

view, the State invites the Court to take “ a renewed

opportunity to consider the scope of the ongoing school

desegregation remedies ordered by the United States Dis

trict Court for the Western District of Missouri for” the

KCMSD. Pet. at 2. Such an invitation is inappropriate,

because the Court already declined to review the magnet

school and capital improvement plans affirmed in Jenkins

v. Missouri, 855 F.2d 1295 (8th Cir. 1988), cert, denied

in relevant part, 490 U.S. 1034 (1989), and the State

never even sought this Court’s review of the basic struc

ture of the remedy approved in Jenkins v. Missouri, 807

F.2d 657 (8th Cir. 1986) (en banc), cert, denied, 484

U.S, 816 (1987). The remedy has been in implementa

tion for years. All of the conversions to magnet schools

called for in the initial six-year cycle of the plan have

taken place; most of the capital improvements have oc

curred. It would be tremendously disruptive of a remedy

that is off to a successful start for this Court to attempt

now, in the context of far narrower issues, to review the

reams of testimony, exhibits, other record evidence and

fact findings that support the desegregation remedy in

Kansas City.

I. REVIEW OF THE COST OF CENTRAL HIGH

SCHOOL AND ASBESTOS ABATEMENT WOULD

BE INAPPROPRIATE UNDER THIS COURT’S

STANDARDS FOR GRANTING A PETITION FOR

CERTIORARI

The actual issue before the courts below that cul

minated in the approval of a revised budget for Central

High School and for asbestos abatement was limited to

17

ascertaining the appropriate and accurate cost of those

projects. The court previously had found that a new

Central High School to replace the segregation-scarred

Central High School building was a necessary part of the

desegregation plan. Indeed, the State in those earlier pro

ceedings had offered no evidence contesting the need for

a new Central High School as part of the desegregation

plan, nor did it challenge that asbestos abatement had to

be done in KCMSD school buildings to make them suffi

ciently safe and healthy for successful desegregation pro

grams. Indeed, the State’s own proposed desegregation

plan component for capital improvements called for as

bestos abatement as part of the renovation work.14

It is simply not the case that these increased budgets

were ordered, as the State suggests, because it would be

nice to have bigger, better, or fancier schools to attract

non-minority enrollment. In the case of Central High

School the actual stated reasons for the budget increase,

in both the KCMSD’s request and the district court’s find

ings, are: 1) The budget needed to include items that

originally were omitted erroneously such as architects’

and engineers’ fees, bid advertising, soils survey and test

ing, furniture and construction contingencies; 2) A 72

percent ratio of net to gross building space was more

appropriate than the 85 percent ratio assumed in the

original estimate; and 3) Certain athletic facilities could

not properly be located inside an indoor running track.

Pet. App. A-43, A-50. The asbestos budget increase was

requested by the KCMSD, and affirmed by the Eighth

Circuit, based on “uncontested evidence . . . that asbestos

was found in existing buildings during the court-ordered

renovation, and that many asbestos-containing products

that normally would pose no danger (such as flooring),

became potentially dangerous when disturbed during the

renovation work,”—-factors which “differentiate [ ] this

situation from situations found at other school districts,

14 See note 5, supra.

18

or for that matter any other public buildings.” Pet. App.

A-25.

Because these findings of fact were reviewed by two

lower courts, this Court should follow its “ traditional def

erence to the ‘two-court rule,’ ” United States v. Cecco-

lini, 435 U.S. 268, 273 (1978) (citation omitted), and

decline review. As this Court has frequently stated “ [a]

court of law, such as this Court is, rather than a court

for correction of errors in factfinding, cannot undertake

to review concurrent findings of fact by two courts below

in the absence of a very obvious and exceptional showing

of error.” Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co., 482 U.S. 656,

665 (1987), quoting Graver Tank & Mfg. Co. v. Linde

Air Products Co., 336 U.S. 271, 275 (1978).15 Since there

has been no “ exceptional showing of error,” the judgment

of the district court, affirmed by the Eighth Circuit Court

of Appeals, should remain undisturbed.

Even beyond the two-court rule, the complex remedial

situation here should make the Court hesitate to review

the district court’s fact findings concerning a change in

the remedy, because changes in equitable remedies are

frequently necessary if remedial goals are to be achieved.

See United States v. Montgomery County Board of Edu

cation, 395 U.S. 225, 234-35 (1969) (in school desegre

gation cases, remedial orders that are inflexible and rigid

are “ troublesome” ). As this Court has long taught, “ [i]n

fashioning and effectuating [such] decrees, the courts

will be guided by equitable principles. Traditionally,

equity has been characterized by a practical flexibility in

shaping its remedies and by a facility for adjusting and

reconciling public and private needs.” Milliken v. Brad

15 See also, e.g., Tiffany Fine Arts, Inc. v. United States, 489 U.S.

310, 317-18 n.5 (1985) (noting “ reluctance to disturb findings of

fact concurred in by two lower courts” ) ; NCAA v. Board of Regents,

468 U.S. 85, 98 n.15 (1984) (Court accords “ great weight to a find

ing of fact which has been made by a district court and approved by

a court of appeals” ) ; Rogers v. Lodge, 458 U.S. 613, 623 (1982)

(same).

19

ley, 433 U.S. 267, 288 (1977), quoting Brown v. Board

of Education, 349 U.S. 294, 300 (1955).16

The wisdom of these admonitions is illustrated here.

The State petitioners never challenged as clearly errone

ous the fact finding on which these budget increases were

based. While they contested in the district court some of

the facts KCMSD and the Jenkins plaintiffs presented,

their own expert architect acknowledged at the eviden

tiary hearing on the Central High School budget that

certain costs were not included in the original construc

tion estimate that were essential for completion of the

project. J.A. 1146-49; J.A. 1151. While the State com

plained generally in objecting to the use of the AHERA

standard for asbestos abatement that not all of the abate

ment was necessitated by the disruption of asbestos due

to demolition and renovation required elsewhere in the

desegregation plan, it failed to produce any evidence iden

tifying any particular portion of the abatement that was

unrelated to that disruption and the need to make schools

sufficiently safe and healthy to conduct successful educa

tional programs that will draw a desegregated enrollment.

The State petitioners’ attacks on the use of AHERA

standards for asbestos abatement make clear how far

its argument has strayed from the record and logic of the

courts below. At the same time that the State petitioners

16 Accord, Swann v. Charlotte-Meckleriburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1, 15 (1971) ( “ breadth and flexibility are inherent in

equitable remedies” ) (emphasis added). The lower federal courts,

in considering modifications in desegregation decrees, repeatedly

have recognized that the district courts are in the best position to

assess the appropriateness of changes in the remedy. See, e.g.,

Booker v. Special School Dist., 585 F.2d 347, 353 (8th Cir. 1978),

cert, denied, 443 U.S. 915 (1979) ( “ the basic responsibility for de

termining whether . . . and to what extent [a desegregation injunc

tion] should be modified rests primarily on the shoulders of the dis

trict court that issued the injunction in the first place” ) ; Mapp v.

Bd. of Educ., 477 F.2d 851, 852 (6th Cir.), cert, denied, 414 U.S.

1022 (1973) (“ [appropriate relief required by changed conditions

is a matter for presentation to and consideration by the District

Court” ).

20

criticize the courts below for supposedly adopting as the

guideline for the remedy the “virtually limitless” stand

ard of attractiveness to additional non-minority students,

they fault those courts for adopting the AHERA regu

latory standards for asbestos abatement work. Far from

being limitless, the AHERA standards add an objective

level of precision to the remedy, so that the school dis

trict can measure not whether it has done all of the as

bestos abatement it would like to do, or that it would be

attractive to do, but that it must do under federal law

because it is disrupting asbestos in the course of other

work required by the court-ordered plan.

The State’s AHERA argument is as illogical as would

be a complaint that electrical work performed in the

course of the desegregation capital improvements was

being done in accordance with the standard required by

the city’s building code. When the court orders that the

constitutional violations that caused the district’s schools

to “ rot[J” be remedied by building a new school or ad

dition, or by upgrading wiring to provide the lighting

needed for an adequate educational environment, that

work must, of course, meet the applicable building codes.

That the work is “up to code” does not mean that the

State is required as an obligation under the desegrega

tion plan to bring the KCMSD schools’ electrical systems

up to the building code; the use of the building code as

a measure is a function of the fact that electrical work

is being done for other reasons. Indeed, the reasons for

the work the State does not, and cannot, challenge, hav

ing acknowledged the same remedial proposals in its own

capital improvements plan. The use of the building code,

like the use of AHERA to measure the appropriate de

gree of asbestos abatement, is the kind of objective meas

ure that the lower federal courts can and should rely

on to lend some clarity and objectivity in the shaping of

an equitable remedy. The illogical alternative apparently

favored by the State petitioners is an order that the

KCMSD abate asbestos disturbed as part of the constitu

tionally mandated desegregation plan capital improve

21

ments to some lesser degree than is required by federal

law, and by the health and safety needs of KCMSD

schoolchildren.

Finally, the issues here are moot, and as a practical

matter present no opportunity for the Court to change

the course of the Central High School construction or

asbestos abatement projects. The new Central High

School is now completed. The school opened in September

1991, and whereas it was an all-minority school before

it became a magnet, the student body for 1991-92 is 17.5

percent non-minority. This is significant progress, since

the existing, all-minority classes of students were not

required to leave when the school became a magnet school.

The freshman class is 24 percent non-minority, so en

hanced desegregation for Central is readily achievable.

Similarly, the $910,224 in additional absestos work

for six schools, about which the State complains, has

long been completed and paid for. In the desegregation

capital improvements program generally, the vast ma

jority of the work has been completed.

Litigants “must have suffered, or be threatened with,

an actual injury traceable to the defendant and likely to

be redressed by a favorable judicial decision” before this

Court should exercise its discretionary jurisdiction. Lewis

v. Continental Bank Cory., 494 U.S. 472,------ , 110 S. Ct.

1249,1253(1990) (emphasis added) (citations omitted).17

A ruling by this Court would not change the fact that

Central High School has been built in accordance with

17 This is true because Article III of the Constitution limits the

federal courts to adjudicating- “actual, ongoing controversies between

litigants.” Deakins v. Monaghan, 484 U.S. 193, 199 (1988). In

addition, Article III “ denies federal courts the power ‘to decide

questions that cannot affect the rights of litigants in the case before

them,’ ” Lewis v. Continental Bank Corp., 110 S. Ct. at 1253, quoting

North Carolina v. Rice, 404 U.S. 244, 246 (1971), and further limits

them to “ resolving ‘real and substantial controversies admitting of

specific relief through a decree of a conclusive character.” Id., also

quoting Aetna Life Insurance Co. v. Haworth, 300 U.S. 227 (1937)

(emphasis added).

22

the budget increase approved by the courts below, and

the work at the schools subject to the asbestos abate

ment budget increase of $910,224 has been completed.18 19

Needless to say, these issues do not present any con

flict among the circuits that requires resolution by this

Court, nor do they present any important question of

federal law. They concern the process of school build

ing construction and estimating the costs of such con

struction. The fact findings at issue are backed by the

testimony, in affidavits and at a hearing in the case of

Central High School, of architects, construction managers

and construction cost estimators. They should remain

undisturbed by this Court.

II. EVEN IF THE PETITION PRESENTED THE ISSUE

OF THE OVERALL SCOPE OF THE DESEGREGA

TION REMEDY IN KANSAS CITY, THE COURT

SHOULD DECLINE REVIEW BECAUSE IT HAS

PERMITTED THAT REMEDY TO GO FORWARD

WHEN THE SCOPE ISSUE WAS PREVIOUSLY

PRESENTED

Despite the fact that the questions presented by the

State petitioners raise only the narrow and technical

issues described in part I. above, petitioners invite the

Court generally to “consider the scope of the ongoing

school desegregation remedies” ordered for Kansas City.

Pet. at 2.:1® That issue is not properly before the Court

18 The State petitioners likely will contend that these issues are

not moot because this Court could rule that the State should not

have to pay for the budget increases. Such a narrow question of

payment allocation is hardly an issue, however, that warrants this

Court’s review.

19 The State stresses repeatedly that the overall purported cost of

the remedy is “ some $1.2 billion” and that it “ has actually paid

approximately $4-69 million” toward the remedy. Pet. at 9 (emphasis

in original). These numbers distort considerably what is at issue

in the instant petition and the facts regarding the overall remedy.

The actual construction cost increase approved for Central High

School was $8,231,565, with a 10 percent contingency factor, and the

actual cost increase for asbestos abatement at six schools was

23

because of the narrowness of the State’s questions and

the rulings actually made by the court of appeals on the

two budget change decisions the State petitioners chal

lenge. See Sup. Ct. R. 21.1(a) ( “ Only the questions set

forth in the petition, or fairly included therein, will be

considered by the Court” ) ; Berkemer v. McCarty, 468

U.S. 420, 443 n.38 (1984).

Even if that decision and the questions presented could

somehow be read to implicate larger issues about the

scope of the remedy overall, the Court should decline

review because it has permitted the remedy to go for

ward on two previous occasions when review of scope

issues was requested by various parties.20 * * * * * * * * * 30 In 1989, the

$910,224, with future work likewise to meet the AHERA standards.

Even if the petition properly raised issues concerning the overall

scope of the remedy, the State’s $1.2 billion figure apparently a)

compresses about 10 years of capital improvement work and seven

years of magnet school and desegregation program costs into one

number, b) is based at least in part on maximum budgeted figures

and not on the actual costs of the work, which have been ascertained

on occasion to be lower, and c) includes all the costs paid by the

KCMSD from locally generated funds.

20 The State’s rather dramatic recitation of what it characterizes

as “ the evolution of this expansive remedy” stresses the dollar

amounts of each stage of the further development of the remedy, as

if to suggest that the costs of the remedy will continue to escalate

forever if not halted by this Court. Pet. at 5-10, 16-18, 20 (“ the

courts in this case have embarked on a remedy that is potentially

endless in nature and scope” ). In fact, the capital improvements

ordered by the courts below are one-time projects to provide schools

or to make existing schools suitable for desegregation programs. A

very significant proportion of that work is already completed. With

respect to the magnet school plan, the KCMSD has made a commit

ment to the district court that after the initial cycle of implementa

tion and magnet school conversions ends at the conclusion of the

1991-92 school year, the cost will begin to drop because start-up

equipment, supplies and training necessary to begin these programs

will be in place. In short, there is no basis to believe that any party

to this case, or the courts below, intend these decrees to operate

“ in perpetuity” in violation of this Court’s teaching in Board of

Education of Oklahoma City Public Schools v. Dowell, —— U.S.

------ , ------ , 111 S. Ot. 630, 637 (1991).

24

State petitioners sought review of the scope of the de

segregation orders’ Long-Range Magnet School Plan and

capital improvements plan, arguing specifically, as they

do in the instant petition, that a remedy based on the

duty to attract additional non-minority students to a

school district and to improve a school district to a

level of comparability with surrounding districts is be

yond the power of a federal court remedying an intra

district constitutional violation. Compare Petition in

Nos. 88-1150, et al. at i (“ Whether a federal court, rem

edying an intradistdict [school segregation] violation

. . . may a) impose a duty to attract additional non

minority students to a school district, and b) require

improvements to make the district schools comparable to

those in surrounding districts” ) with Petition at issue

here, No. 91-324 at 18 ( “By establishing as a primary

remedial objective the goal of attracting additional non

minority enrollments to the school system, the lower

courts in Jenkins have defined this intradistrict remedy

in terms that exceed the constitutional mandate.” ) .

On April 24, 1989, this Court declined to review the

scope of the remedy issue presented by the State in Nos.

88-1150, et al. 490 U.S. 1034 (1989). Moreover, the

Court also declined to review the original petitions for

certiorari filed by KCMSD and the Jenkins plaintiffs in

1987, which argued that a mandatory interdistrict rem

edy was justified based on the record before the district

court in the liability case. See 484 U.S. 816 (1987).

The State bypassed the opportunity to cross-petition to

challenge the basic structure of the original remedy,

which called for educational programs, magnet schools,

capital improvements, and desegregative voluntary in

terdistrict transfers.

The result has been that progress has continued in the

implementation of the overall remedy right up to today.

The 1991-92 school year, now underway, is the final

year for conversion of schools to magnet schools under

the first six-year cycle of the Long-Range Magnet School

25

Plan. Accordingly, all of the KCMSD high schools and

middle schools have been converted to magnet schools,

along with 35 elementary schools. This process has in

cluded training of existing staff and hiring of specialized

staff in the magnet themes, the purchase of equipment

and supplies to support the specialized programs that the

themes require and, under the capital improvements plan,

the construction or renovation of specialized facilities to

accommodate specialized classes. Indeed, under the capital

improvement plan, seven new school buildings are com

pleted and already housing students in magnet school

programs. Six more new school buildings are under con

struction and are scheduled for completion during the

1992-93 school year. Dozens of other school building ren

ovation projects are completed or will be completed dur

ing the current school year.

Simply put, the courts below have been on the course

of supervising the implementation of the remedy for over

six years, during which this Court declined or was not

asked to review challenges to the scope of that remedy.

It would be extremely disruptive to the implementation,

and no doubt could set the KCMSD on an even longer

course toward unitary status, if the Court entertained

now what at least some passages in the State’s petition

describe as a global review of the remedial standards and

particular remedy components adopted by the courts be

low.121

In an effort to raise some question of federal law

that might make these issues appear worthy of review

21 Needless to say, review of the overall remedy, after over six

years of judicial proceeding's and implementation, would raise

many of the same questions described at pages 18-19 above con

cerning deference to the fact findings of the courts below. The

remedial proceedings have been the subject of weeks of major

hearings and several smaller hearings per year, involving expert

as well as lay testimony on educational and construction issues.

The parties have filed cabinets full of motions papers and exhibits

during the remedial proceedings, and the district court has entered

over 160 substantive orders.

26

by this Court, the State petitioners suggest that “ [t]he

grant of certiorari in this case would allow this Court

to establish clearly that the permissible scope of a court-

ordered desegregation remedy is to be determined by ref

erence to the factors identified in Green v. New Kent

County School Board, 391 U.S. 430 (1968) . . . Pet.

at 16. Certainly no such clarification is needed. For

over 20 years, the lower federal courts have been super

vising the development and implementation of desegrega

tion plans with reference to this Court’s directives in

Green, reiterated last Term in Board of Education of

Oklahoma City Public Schools v. Dowell, — — U.S. — —,

------ , 111 S. Ct. 630, 638 (1991) . The district court

here relied on Green, among other decisions of this Court,

as the guideline for the overall structure of the remedy.

639 F. Supp. at 23. The State petitioners fail completely

to explain how the Central High School and asbestos de

cisions run afoul of Green, since both bear directly on the

“ facilities” factor cited in Green as part of “every facet

of school operations” that must be considered in formulat

ing a desegregation remedy. Green, 391 U.S. at 435.

The State petitioners also ask the Court “to specify

that the federal courts’ mandate to determine whether

the vestiges of de jure segregation had been eliminated

‘as far as practicable,’ Dowell, 111 S. Ct. at 638, is to be

determined by those same Green factors.” Pet. at 16

(footnote omitted). The Central and asbestos issues

simply do not raise Dowell issues of when stable desegre

gation, to the extent practicable, can be said to have been

achieved. No party in this case has made a request that

the district court determine whether unitary status has

been achieved in the KCMSD, and the State makes no

representation that the KCMSD is unitary. Such a deter

mination obviously is premature in the midst of imple

mentation of this desegregation plan. Without a deter

mination by the district court, after a hearing and

through proper fact findings, as to whether all vestiges

of segregation have been removed to the extent practi

27

cable, there is no Dowell issue to be considered by this

Court.

For the same reasons, the issues presented by this

petition do not raise any question of whether some or all

“ largely-minority schools” can remain in a unitary school

district. Pet, at 18. The petition does not define what a

“ largely-minority school” would be in Kansas City, and

the courts below have not opined on whether it is prac

ticable for all schools in the KCMSD to have desegregated

enrollments, or whether some racially identifiable schools

will be permitted to remain at the termination of the

remedy. Indeed, no party has sought a ruling on that

issue, which is unsurprising since it would be premature

in the midst of implementation of the remedy, while de-

segregative gains are still being made, to determine

whether some schools as a practical matter will remain

racially identifiable. Certainly the question of whether

racially identifiable schools will remain in the KCMSD

is not implicated in issues of the proper budget for con

struction of Central High School and the proper amount

of asbestos abatement to be done during desegregation

capital improvements.

In fact, the issue of racially identifiable schools may

never need to be reached, because as the KCMSD magnet

schools come on line, they are slowly winning the desegre

gated enrollments that are the goal of the plan. In 1985,

Judge Clark found that 19 of the 50 elementary schools

had 90 percent or higher black enrollment, as did three

of the eight junior high schools and three of the eight

high schools. By the 1991-92 school year, 11 fewer schools

were at that level: 9 fewer elementary schools and 2

fewer middle and high schools. In the 1991-92 school

year, almost 1,700 new non-minority students, who previ

ously had attended private or suburban schools, were at

tending school in the KCMSD. Of that number, over 900

were new to the KCMSD in the fall of 1991. A solid

28

foundation of desegregative progress and of remedying

the harm to minority students has been laid.

There can be no doubt that such voluntary desegrega

tion costs more to achieve than the type of mandatory

busing that the State proposed and the district court re

jected in 1985. Voluntary desegregation through magnet

schools and parent choice, although it requires an invest

ment to make the schools worth choosing, avoids the coer

cion and instability inherent in busing-only remedies.

The district court here so found back in 1985. 689 F.

Supp. at 35-36. For over six years it has been on a course

of making a voluntary remedy work in a school district in

a state of “ decay” and declining educational achievement.

As we are finally turning the corner on desegregative

progress, that remedy should not be disturbed.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the petition should be denied.

Respectfully submitted,

Allen R. Snyder *

Patricia A. Brannan

Hogan & Hartson

555 Thirteenth St., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20004

(202) 637-5741

Shirley W ard Keeler

Michael Thompson

Blackwell Sanders Matheny

W eary and Lombardi

Two Pershing Square

2300 Main Street

Kansas City, Missouri 64141

(816) 274-6816

October 28,1991 * Counsel of Record