Russell v. The American Tobacco Company Reply Brief

Public Court Documents

August 29, 1974

25 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Russell v. The American Tobacco Company Reply Brief, 1974. ad034361-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1b71eb46-84a3-4e17-a3e0-b22b05eb557f/russell-v-the-american-tobacco-company-reply-brief. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

\

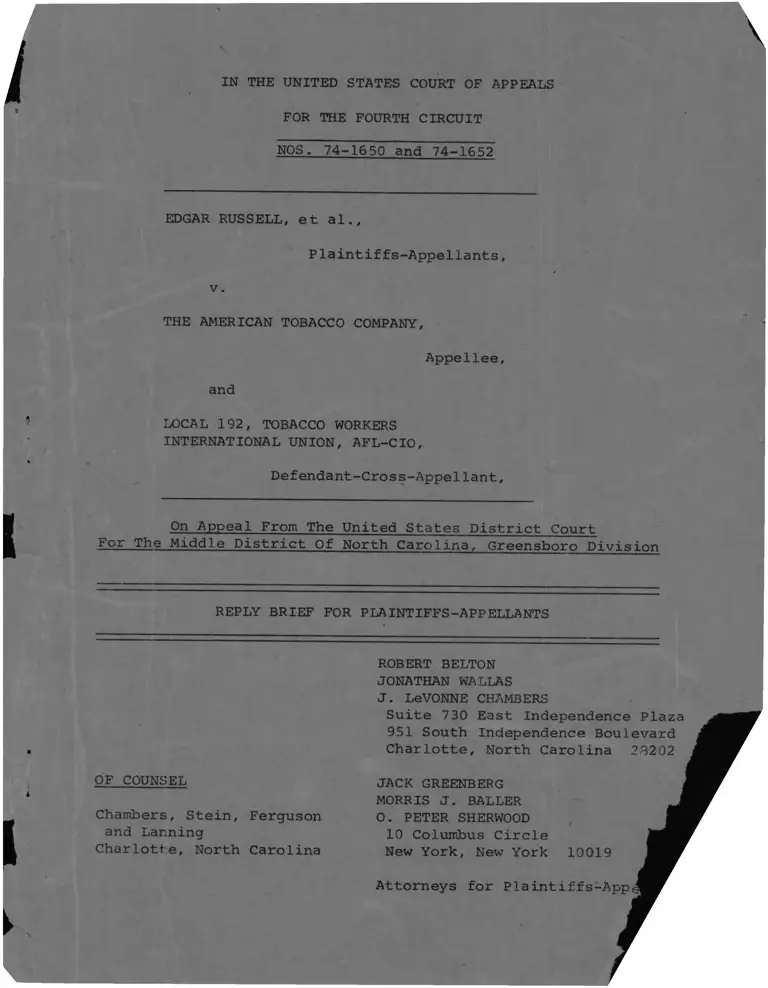

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

NOS. 74-1650 and 74-1652

EDGAR RUSSELL, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

THE AMERICAN TOBACCO COMPANY,

Appellee,

and

LOCAL 192, TOBACCO WORKERS

INTERNATIONAL UNION, AFL-CIO,

Defendant-Cross-Appellant,

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Middle District Of North Carolina, Greensboro Division

REPLY BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

OF COUNSEL

Chambers, Stein, Ferguson

and Lanning

Charlotte, North Carolina

ROBERT BELTON

JONATHAN WALLAS

J. LeVONNE CHAMBERS

Suite 730 East Independence Plaza

951 South Independence Boulevard

Charlotte, North Carolina 23202

JACK GREENBERG

MORRIS J. BALLER

0. PETER SHERWOOD

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-App

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

NO. 74-16 50

EDGAR RUSSELL, et al..

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

THE AMERICAN TOBACCO COMPANY,

Appellee,

and

LOCAL 192, TOBACCO WORKERS

INTERNATIONAL UNION, AFL-CIO,

Defendant-Cross-Appellant.

On Appeal From the United States District Court

For The Middle District of North Carolina, Greensboro Division

REPLY BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

ROBERT BELTON

JONATHAN WALLAS

J. LeVONNE CHAMBERS

Suite 730 East Independence Plaza

951 South Independence Boulevard

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

OF COUNSEL

Chambers, Stein,Ferguson

and Lanning

Charlotte, North Carolina

JACK GREENBERG

MORRIS J. BALLER

0. PETER SHERWOOD

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Plaintiffs' reply brief will address the issues raised

by Local 192 in its cross-appeal and several of the arguments

advanced by the Company in response to plaintiffs' main brief.

Plaintiffs will rely on the arguments set forth in their main

brief as to the remaining issues.

Local 192 adopts the statement of fact set forth in

plaintiffs' main brief (Pis' Br. pp. 12—33) as being sub

stantially correct" (Local's Br. p. 2). The Company's arguments

with the plaintiffs' statement of fact attempt only "to clarify

some statements in plaintiffs' recitation of the facts which

the Company conceives to be misleading" (Company's Br. pp. 1-

2) .

Plaintiffs will first discuss the issues raised by

Local 192. Most of these issues are jurisdictional.

A. The Jurisdictional Issues Raised By Local 192.

1. Jurisdictional prerequisites

Local 192 argues that the court below did not have

jurisdiction because the action was not timely. In support of

this argument, Local 192 states on p. 16 of its brief that

"there is no evidence that this action was instituted within

thirty (30) days after any one of the plaintiffs received

notice from the EEOC of his right to sue". Prior to filing

its answer to the complaint, Local 192, on February 14, 1968,

filed a motion to dismiss alleging, inter alia, that the

-2-

district court did not have jurisdiction because the plaintiffs

had alleged no facts in the complaint "from which it could be

affirmatively and positively determined that the requirements

of Sections 706(d) [42 U.S.C. Section 2000e-5(d)] and Section

706 (e) [42 U.S.C. Section 2000e-5(e)] of the Civil Rights Act

i/of 1964 have been observed". In the same motion Local 192

moved to strike Exhibits A and B attached to the complaint on

the grounds that Section 706(a), 42 U.S.C. Section 2000e-5(a),

of Title VII provides that a charge taken by EEOC shall not

be public or used as evidence in a subseauent proceeding.

2/

Exhibit B to the complaint is a copy of a letter from EEOC

to plaintiff Edgar Russell dated December 5, 1967 advising

Russell that conciliation efforts in EEOC Case No. AT 68-8-129E

and 129U against both the defendants herein had failed and that

he had a right to institute an action in federal court within

thirty (30) days after receipt of said letter. The complaint

3 /was filed on January 5, 1968 (A.60).

1/

This motion is not reproduced in the Appendix.

2/

Exhibit B is not reproduced in the Appendix but a

copy is attached to the brief for the convenience of the

court.

See Rule 6(a), Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

3/

-3-

On January 10, 1969 the court below entered a Memorandum

and Order denying the motion of Local 192 to strike Exhibit B

on the ground that "if for no other reason, the charges and

the 30-day letters of notification are relevant and material

to show that the plaintiffs have exhausted their administrative

remedies" (A.73). That same order allowed plaintiff to file

an amendment to the complaint to correctly state the dates on

which the right to sue letters were received by the named

plaintiffs (A. 75-77).

On July 17, 1970 the court heard oral arguments on the

defendants' motions to dismiss the complaint on the grounds

that the plaintiffs had failed to exhaust their administrative

remedies before EEOC. The motions addressed to the juris

diction of the court were denied in a Memorandum and Order

filed on January 20, 1971 and the reasons are specified.

The basis on which the district court relied are fully set

forth in its Memorandum and Order which appears at A. 97-105.

The jurisdictional facts relied on by the court were as

follows:

1. Charges were filed with EEOC by the plaintiffs

on August 3, 1966 and June 15, 1967. Plaintiff Russell

filed an additional charge dated July 26, 1967.

-4-

Local 192's own evidence, Exhibit 12, shows that

these charges were so filed.

2. Two sets of right to sue letters were issued

to the plaintiffs by EEOC. Those plaintiffs who

filed charges in 1966 were informed by letters

dated December 1, 1967. Those who had filed

charges in 1967 were informed by letters dated

December 5, 1967.

3. The notice of right to sue letter on Russell's

July 27, 1967 charge to EEOC was issued December 5,

1967. See copy attached hereto.

4. The court also found that defendants "admitted

that Russell's [December 5, 1967] letter was re

ceived within the thirty-day span previous to the

complaint" (A.99). This admission has not been

challenged by Local 192.

These facts, as found by the district court, clearly

support the finding of the district court that the plaintiffs

had exhausted their administrative remedies before EEOC, and

that at least one of the plaintiffs had filed his complaint in

the court below within thirty days of receipt of his notice.

See Johnson v. Seaboard Coast Line Railroad Co., 405 F.2d 645

(4th Cir. 1968), cert.denied 394 U.S. 918 (1969). See also

-5-

Oatis v. Crown Zellerbach Corp., 39 F.2d 496 (5th Cir. 1969).

At the trial on the merits, Local 192 objected to the

July 27, 1967 charge of EEOC being received. This charge was

identified as plaintiffs' trial Exhibit 29. At the time this

exhibit was offered, Local 192 moved to strike this exhibit.

The court denied the motion but granted Local 192 leave to

renew the motion at a later time. Tr. 43, 51. At no time,

either at the close of plaintiffs' evidence, Tr. 527, nor at

the close of the evidence offered on behalf of Local 192,

Tr. 1201, was this motion renewed. Local 192 did renew its

motion to dismiss for lack of jurisdiction but did not renew

its motion to strike plaintiffs' Exhibit 29.

Moreover, if Local 192 had any serious questions about

December 7, 1968 as the date on which Russell received his

notice, it has ample opportunity to cross examine Russell on

this issue. Russell testified at trial and Local 192 covered

approximately 44 pages of cross examination of Russell (Tr.

450-494) without raising at any time any questions about the

December 7, 1968 receipt date.

2. Local 192 not properly a respondent before EEOC.

Local 192 makes several arguments in support of its

contention that it was not properly a respondent before EEOC.

First, Local 192 argues that the July 27, 1967 charge of

-6-

Russell which clearly named Local 192 as a respondent was not

under oath. Local's Br. at 18. Local 192 cites no authority

for this argument but is apparently familiar with the cases

holding that the requirement for verification of a charge be

fore EEOC is merely administrative in character. Indeed, the

authority is to the contrary of Local 1921s position. In the

leading case on this issue the Seventh Circuit in Choate v\_

Caterpillar Tractor Co., 402 F.2d 357, 360 (1968) held:

Given the fact that the administrative

remedy alone may be insufficient to vindi

cate the rights of aggrieved parties, we

believe that it would be unnecessarily

harsh and in derogation of the interests

of those whom the Act was designed to pro

tect to interpret the statutory language

denying substantive rights in the district

court because of procedural defects before

the Commission. If the Commission under

takes to process a charge which is not

"under oath", we perceive no reason why

the district court should not treat the

omission of the oath as a permissive waiver

by the Commission. To deny relief under

these circumstances would be a meaningless

triumph of form over substance.

Accord, Blue Bell Boats, Inc, v. EEOC, 418 F.2d 355 (6th Cir.

1969), and cases cited therein at 357.

Second, Local 192 argues that the failure of EEOC to serve

on it copies of the charges deprived the district court of

jurisdiction. This argument was rejected by the court in

-7-

Mondy v. Crown Zellerbach Corp., 271 F. Supp. 258, 261 (E.D.

La. 1967). The court below relied on this decision in reject

ing Local 192’s position on this issue. The rationale

of Judge Butzner in Quarles v. Philip Morris, Inc., 271 F. Supp.

842, 846 (E.D. Va. 1967) in rejecting the defendant's claim

that jurisdiction is defeated where EEOC fails to attempt con

ciliation is equally applicable here: "The plaintiff is not

responsible for the acts or omissions of the Commission.

Local 192 next argues that the failure of EEOC to enter

into conciliation discussions with it defeats the jurisdiction

of the court. This argument just simply overlooks the decision

of this court in Johnson v. Seaboard Coast Line Railroad Co.,

405 F.2d 648 (1968), cert. denied 394 U.S. 918 (1968) which

holds that conciliation efforts is not a jurisdictional pre

requisite .

B. Other Ground Asserted by Local 192.

Local 192 apparently lumps under its jurisdictional

attack the order of the district court denying its motion to

require plaintiffs to join two other locals— one in Durham,

North Carolina and the other in Richmond, Virginia— as defendants

in this case. Although not articulated in its brief, it seems

that Local 192's argument is that the Durham and Richmond

Locals are indispensable parties and the failure of the plaintiff

-8-

to sue these locals, in this case, deprives the court of

jurisdiction. The obvious answer to this argument is the

Richmond and Durham locals are not indispensable parties;

the court did not attempt to adjudicate the rights of the

Durham and Richmond locals; and there is nothing in the

March 8, 1974 judgment of the district court which, in any way,

purports to adjudicate the rights of the Durham and Richmond

locals. Cf. United States v. Pilot Freight Carriers, Inc.,

54 F.R.D. 519, 521-522 (M.D.N.C. 1972).

Moreover, the court extended an invitation to these

locals to join in this case by directing the clerk to send

copies of its order to these locals. Apparently, these locals

did not feel that their rights and obligations were in any

way affected by the pendency of this lawsuit for the reason

that they did not seek to join in this lawsuit.

Local 192 next argues that assuming that its jurisdictional

arguments are rejected, Russell has no standing to represent

regular or seasonal employees of Leaf. This argument was re

jected by the court below (A.102)and must be rejected by this

Court. The court below found that allegations in the July 27,

1967 EEOC charge filed by Russell were sufficient to allow the

plaintiffs to raise issues and to challenge the discriminatory

practices of the defendants at both Leaf and Branch. In so

ruling the court below held:

-9-

However, it is not required that the

charge be worded with the specificity

often associated with legal expertise.

So long as the charge contains a general

notice of the situation, courts have

permitted matters reasonably related to

those charged and those growing out of

the charge to be considered in a court

action. Sciaraffa v. Oxford Paper Co._,

310 F. Supp. 891 (D. Maine 1970);

Younger v. Glamorgan Pipe & Foundry Co.,

310 F. Supp. 195 (D. West Va. 1970);

Bowe v. Colgate-Palmolive Co., 416 F.2d

711 (7th Cir. 1969); Logan v. General

Fireproofing Co., 309 F . Supp. 1096

(W.D.N.C. 1969) .

(A. 100). The cases relied on by the district court fully

supports its ruling. See also Graniteville Co. (Sibley Div.) v^

EEOC, 438 F.2d 32, 37-38 (4th Cir. 1971).

Joined as plaintiffs in this action were black employees

of Branch and Leaf. See Pis' Br. p.2, n.2. The court found

that this action was properly maintained as a class action

( A . 91-92) and further held that "although the others [named

plaintiffs other than Russell] might be precluded from individual

ly maintaining an action by reason of the time limitations,

they are included in the class of black employees of the

American Tobacco Company in Reidsville, North Carolina, and

are properly designated as plaintiffs in this action .

In support of its argument that black Leaf employees were

improperly joined in this action, Local 192 relied on the

decision of the Fifth Circuit in Oatis v. Crown Zellerbach

-10-

Corp., 398 F.2d 496 (1968). The Oatis case fully supports

the reasoning of the district court.

In Oatis, the district court had allowed a Title VII

action to proceed as a class action but had limited the class to

those members who had filed charges with EEOC. Joined in the

action were plaintiffs who had filed charges with EEOC and

plaintiffs who had not filed charges. On appeal, the Fifth

Circuit reversed holding that:

Additionally, it is not necessary that

members of the class bring a charge with

the EEOC as a prerequisite to joining as

co-plaintiffs in the litigation. It is

sufficient that they are in a class and

assert the same or some of the same issues.

This emphasizes the reasons for Oatis,

Johnson and Young to appear as co-plaintiffs.

They were each employed in a separate de

partment of the plant. They were repre

sentatives of their respective departments,

as Hill was of his, in the class action.

They, as co-plaintiffs must proceed however

within the periphery of the issues which

Hill could assert. Under Rule 23(a) they

would be representatives of the class con

sisting of Negro employees in their depart

ments so as to fairly and adequately protect

their interest. This follows from the fact

that due to the inapplicability of some of

the issues to all members of the class, the

proceedings might be facilitated by the use

of sub-classes. In such event one or more

of the co-plaintiffs might represent a sub

class. It was error, therefore, to dismiss

appellants. They should have been permitted

to remain in the case as plaintiffs but with

their participation limited to the issues

asserted by Hill.

398 F. 2d at 499.

-11-

This is precisely what happened in this case. The two

major departments of the Company are Leaf and Branch and joined

as plaintiffs in this action are black employees of both Leaf

and Branch.

The Union also argues that there is antagonism between

blacks at Leaf and blacks at Branch. But a close reading of

the complaint and the facts established in this case clearly

demonstrates that the claims asserted by the representative

plaintiffs of Brahch and Leaf are not antagonistic. All that

the plaintiffs desire is to have their employment opportunities

uneffected by racial discrimination. This is the common

question of fact and law in the case. The argument advanced

by Local 192 is not unlike the reasoning relied on by the

district court in Jenkins v. United Gas Corp., 261 F. Supp.

762, 763-764 (E.D. Tex. 1966). There the district court dis

missed a class action on the grounds that "no common question

of fact exists as to all Negro employees of the defendant, since

different circumstances surround their different jobs and

qualifications in the structure of the corporation". This

argument was rejected by the court of appeals in Jenkins v.

United Gas Corp., 400 F.2d 28, 33-34 (1968).

Local 192 takes the position that the mere presence at

a meeting where the 1968 collective bargaining agreement was

-12-

accepted by the union membership is a sufficient basis on

which this court can find that special circumstances are

present to defeat imposition of back pay as against it. The

only thing that the evidence shows is that some of the named

plaintiffs were present at the 1968 meeting when the unanimous

vote was made. There was no showing that any of these

plaintiffs participated in the unanimous vote since the vote

was not taken by a secret ballot.

Even if it were shown that the plaintiffs had voted for

the 1968 collective bargaining agreement establishing a single

seniority line for Branch and a separate seniority line for

Leaf there would be nothing inconsistent with that vote and

what they seek in this action. As plaintiffs have pointed

out in their main briefs, they are not asking for the merger

of the seniority lines at Leaf and Branch. The only relief

requested for the Leaf personnel is that they be given an

opportunity to transfer from their racially segregated jobs in

Leaf to the more lucrative and better paying jobs at Branch

without a loss of seniority. The relief requested by the

Leaf plaintiffs does not mean that the Company and Local 192

must establish a single line of seniority for all of the

employees at Leaf and Branch.

The good faith argument advanced by Local 192 has not

been demonstrated on this record. In 1968 when the Company

-13-

offered the thirty-five day prevailing rate proposal for certain

jobs at Branch, the union leadership rejected the proposal

solely on the grounds that white employees who had theretofore

performed those jobs were subject to a much longer period

before reaching prevailing rate. The union leadership did not

even discuss this proposal with its membership. Furthermore,

Local 192 made no efforts to disestablish its racially

segregated union of its own initiative. That initiative had

to be supplied by threat from the Company that it could no

longer continue to negotiate with the racially segregrated

unions and at the same time continue to maintain its contracts

with the federal government. When the segregated locals did

merge in 1963, Local 192 simply absorbed the members of the

black local and assumed possession and control of all of

the property, assets and bargaining rights of the black

local.

The arguments by Local 192 that it is not a profit making

organization and has no resources other than those gleamed

from its members and that it has no substantial source of income

or accumulated capital from which to pay an award are not

supported by the record in any way. Moreover, these are issues

which have been left to further determination by the court.

See the March 8, 1974 judgment at A. 56-57.

-14-

C. The Brief Filed by the Defendant Company.

Plaintiffs will address only two of the arguments advanced

by the Company in support of its position that the district

court did not err in failing to afford full relief to black

employees at Leaf.

The first argument is the reliance by the Company on

Rule 52(A), Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, as a hurdle to re

versal of the district court finding that Leaf employees had

equal opportunities to be employed at Leaf or Branch. Courts

of appeals review findings of fact in Title VII cases in the

same manner as other findings of fact of the trial court are

reviewed. Findings of fact are not set aside unless the

court of appeals is able to conclude that such findings are

clearly erroneous. Smith v. Delta Airlines, Inc,, 486 F.2d

512, 514 (5th Cir. 1973); Baxter v. Savannah Sugar Refining

Corp., 495 F.2d 437, 445 (5th Cir. 1974). It is equally clear

that where district courts have failed to evaluate claims of

Title VII violations under applicable legal standards, courts

of appeals have not hesitated to reverse. See Pettway v.

American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 494 F.2d 211 (5th Cir. 1974);

Brown v. Gaston County Dyeing Machine Co., 457 F.2d 1377 (4th

Cir. 1972) reversing 325 F. Supp. 541 (W.D.N.C. 1970); Jones

-15-

v. Lee Way Motor Freight, 431 F.2d 245 (10th Cir. 1970);

reversing 300 F. Supp. 653 (W.D. Okla. 1969); Griggs v. Duke

Power Co., 420 F.2d 1225 (4th Cir. 1970), reversing in part,

292 F. Supp. 243 (M.D.N.C. 1968). See also United States v

Chesterfield County School District, 484 F.2d 70 (4th Cir.

1973); Walston v. County School Board of Nansemond_County./

492 F.2d 919 (4th Cir. 1974); Eslinger v. Thomas, 476 F.2d

225 (4th Cir. 197^).

All of the cases cited by the defendant Company on pp.

brief11-24 of its /support the arguments set forth by the plaintiffs

in their main briefs rather than the position asserted by the

„ 4_/Company.—

On page 2 of its brief the Company "concedes" that the

two operations are owned by the same corporation. At this

point, the Company argues, all similarities between Leaf and

Branch ceases. The Company then argues on page 4 of its

brief that the collective bargaining agreements between Local

192 and the Company establish a contractual method for trans-

4_/Reliance by the Company on United States v. H. K.

Porter Co., 296 F. Supp. 40 (N.D. Ala. 1968) is no authority

whatsoever for the company's position. On March 19, 1974

the Fifth Circuit reversed the decision of the district

court and remanded with instructions that the district court

enter an attached decree. 491 F„2d 1105 (1974).

-16-

fers between Leaf and Branch, but on p. 11 the Company refers

to this contractual method as a "limited transfer privilege.

The evidence on this point is that neither the employees at

Branch nor Leaf have / privilege as a matter of a contractual

provision to transfer from Leaf to Branch or vice versa and

at the same time have the full benefit of accumulated Company

seniority for all purposes for which seniority is used.

According to the collective bargaining agreements em

ployees cannot transfer between Leaf and Branch and have bene

fit of their full company seniority for all purposes for which

seniority is used unless the transfer is effectuated at the

request of management of either Leaf or Branch. Management

of Leaf and Branch have exercised their discretion to re

quest employees to transfer between the two facilities and

in each and every instance the employees affected have been

white.

On pp. 11-12 of its brief the Company asserts that "the

Company did not require or force [Leaf employees] to become

employed at Leaf in the first instance and employment in the

Branch was also open to Negroes at all times relevant to

this action." If by "times relevant" the Company intends

to refer to the post July 2, 1965 date, then its assertion

-17-

that Leaf employees could have been employed at Branch is

factually inaorrect. The only way Leaf employees who were em

ployed prior to July 2, 1965 can move to Branch and have

full benefit of their Company seniority would be only at

the request of management of Leaf or Branch. If a transfer

from Leaf to Branch is effectuated at the instance of the

Leaf employee, he would lose all of the benefit of his com

pany seniority and would have to start as a new employee with

Branch. On the other hand, by reference to "times relevant"

the Company was referring to the pre-July 2, 1965 period,

then the only jobs that were open to black Leaf employees

would have been the all black jobs in pre-fabrication at

Branch. The court made a finding that prior to July 2, 1965

the Company had engaged in racially discriminatory hiring

practices at Branch (A.21). This finding is fully supported

t>y the evidence. With clear evidence that the Company had

engaged in discriminatory hiring at Branch prior to 1965

and the findings by the Court that this was true, then if

Leaf employees had applied at Branch and had been hired they

would have been hired only into all black jobs at Branch.

This can hardly qualify as "equality of opportunity" to be

hired at Leaf or Branch.

-18-

D. The Company's reliance on 42 U.S.C. Section 2000e-2(h).

42 U.S.C. Section 2000e-2(h) provides in part that it

shall not he an unlawful employment practice for an employer

to apply different standards of compensation, or different

terms, conditions or privileges of employment to employees

who work in different locations. The Company argues that

this section is applicable to its operations in Reidsville

and Rockingham County and is, therefore, a complete defense

to treating Leaf and Branch as single facilities for purposes

of this case.

The application of this section of Title VII is an is

sue of first impression. Counsel for the plaintiffs have

been unable to find any cases construing this section.

Plaintiffs concede that if the facilities at Reidsville and

Richmond (or Durham) of the Company were involved in this

case, then the applicability of Section 703(h) would be mani

fest. But that is not the situation here. Here we have two

operations of the Company which constitute a functionally

integrated operation which receives green leaf tobacco

from the market, processes it into cigarettes and other to

bacco products, packages it and ships it to the consumer

market. That the two operations are functionally integrated

-19-

is underscored by the testimony of one of the witnesses for

the Company who, in testifying about the reasons for having

Leaf "adjunct to Branch, as it is in Reidsville and Rocking

ham County" is "the convenience of moving tobacco to Branch,

or . - . having a stemmery near where the source of the to

bacco is" (A.316). Leaf does not supply tobacco for further

processing to any of the Company's three other cigarette

manufacturing facilities. See Plaintiffs' Trial Exhibit 1,

Company's Answers to Interrogatory No. 3, page 2.

These two departments are also integrated for purposes

of labor management relations (A.219; A.226). A single col

lective bargaining agreement covers both Branch and regular

Leaf employees (A.226). Management of both Leaf and Branch

have reserved the right to contract to transfer its regular

bargaining unit employees between Leaf and Branch (E.355;

E.486). When the transfer is made at the request of manage

ment of either Leaf or Branch, the employee forfeits none of

the seniority; if the employee transfers at its own request,

he forfeits all of his seniority (E.406-407). The Company

draws its work force from the same labor market, i.e. Reids

ville and Rockingham County. That same labor market does not

-20-

provide a source of workers for the Company's operations

in Richmond, Virginia and Durham, North Carolina.

Furthermore, a part of the Leaf operation is performed

at the Branch facility in Reidsville.

In deciding whether Section 703(h) applies to the in

stant case, the court does not have the benefit of very

much legislative history. In fact, whatever legislative

history there is is set forth on page 41 of the Company s

brief.

Plaintiffs have argued in their main brief that Section

706(h) should have no applicability to the facts of this case.

See plaintiffs' brief pp. 46-52. In addition to the argu

ments set out on those pages, it should be noted that Title

VII on which this action is based is remedial in character

and in the absence of specific legislative intent to the con

trary, the provisions of Title VII should be construed to

achieve its purpose. See Johnson v. Seaboard Airline R._R.,

Co., 405 F.2d 645 (4th Cir. 1968) cert, denied, 394 U.S. 918

(1968); Culpepper v. Reynolds Metals Co., 421 F.2d 888, 891

(5th Cir. 1970); Henderson v. Eastern Freight Ways, Inc.,

460 F.2d 258, 260 (4th Cir. 1972).

CONCLUSION

For the reasons set forth in the brief for plaintiffs

appellants filed heretofore and the reasons set forth in

this reply brief, plaintiffs respectfully pray that this

Court reverse the decision of the court below.

This 29th day of August, 1974,

Respectfully submitted,1

A

ROBERT BELTON

JONATHAN WALLAS

J. LeVONNE CHAMBERS

Suite 730, East Independence Plaza

951 South Independence Boulevard

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

JACK GREENBERG

MORRIS J. BALLER

OF COUNSEL O. PETER SHERWOOD

10 Columbus Circle

Chambers, Stein, New York, New York 10019

Ferguson & LanningCharlotte, North Carolina Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

,'*Sw O

r O ’ -AL E M P L O Y M E N T O P P O R T U N IT Y CO

W A S H IN G T O N . D C. 20506

jon EXHIBIT B

J :

m c ;’ op rig in1 to

WITHIN 30 DAYS

CERTIFIED MAIL RE1U

RECEIPT REQUESTED

DEC 5 1367 In Reply Refer To:

Case No. AT 68-8-129E & 129U

American Tobacco Co. & L o c u i

Union 192, Tobacco Wkrs. Int

Union, Reidsville, N. C.

r*v.i'*r. ct j ai

P. 0. Ecx 92

Ruffin, N. C. 27327

Dear Mr. Russell:

This is to advi.se you that conciliation efforts in the above

matter have railed to achieve voluntary compliance with Title

VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Pursuant to Section 706(e)

of the Act, you are hereby notified that you may, within thirtv

(30)̂ days of the receipt of letter, institute a civil action

in the appropriate Federal District Court. If you are unable

to retain an attorney, the Federal Court is authorized in its

discretron, to appoint an attorney to represent you and to

authorize the commencement of the suit without payment of fees,

costs or security. if you decide to institute suit and find

you need such assistance, you may take this letter, along with

the Commission determination of reasonable cause to believe

Title VI* h •>.: \ "n violated, to the Clerk of the federal District

Court nearest to the place where the alleged discrimination occur-

reo, and request that a Federal District Judge appoint counsel to represent you.

Please feel free to contact the Commission if vou have any ques

tions about this matter.

Sincerely,

j\ L~t n* /'/■£.(/

Pert L. Randolph(Acting)

/

i / \ s

Director of Compliance

-■ y jm " " ...' "SF’I T '

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

The undersigned certifies that copies of the foregoing

Reply Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants have been served on

counsel for each of the parties separately represented by

serving two copies each of said brief on:

Charles T. Hagan, Jr., Esq. and

Daniel W. Fouts, Esq.

Adams, Kleemeir, Hagan, Hannah & Fouts

611 Jefferson Standard Building

Greensboro, North Carolina

Julius J. Gwyn, Esq.

Gwyn, Gwyn & Morgan

108 South Main Street

Reidsville, North Carolina

Ms. Margaret C. Poles

Attorney at Law

Office of the General Counsel

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

1800 G Street, N. W.

Washington, D. C. 20506

This 29th day of August, 1974.

Respectfully submitted

Counsel for Plaintiffs-Appellants