Jackson v. Godwin Brief for Appellant

Public Court Documents

November 1, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Jackson v. Godwin Brief for Appellant, 1967. 6cc990f8-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1bb4d75b-8cd7-4f79-b8cb-c67ed44ac77a/jackson-v-godwin-brief-for-appellant. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

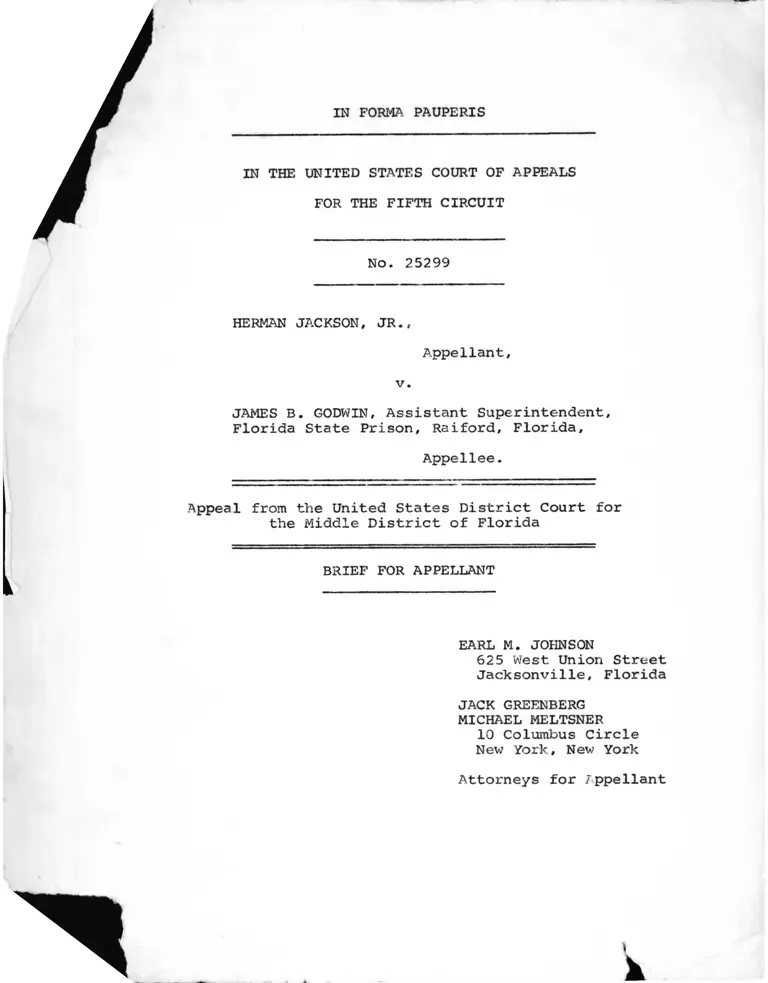

IN FORMA PAUPERIS

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 25299

HERMAN JACKSON, JR.,

Appellant,

v.

JAMES B. GODWIN, Assistant Superintendent,

Florida State Prison, Raiford, Florida,

Appellee.

Appeal from the United States District Court for

the Middle District of Florida

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

EARL M. JOHNSON625 West Union Street

Jacksonville, Florida

JACK GREENBERG

MICHAEL MELTSNER

10 Columbus Circle New York, New York

Attorneys for Appellant

r.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Statement .............................................. 1

Testimony of James B. Godwin ....................... 5

Testimony of Eric 0. Simpson....................... 9

Testimony of Mrs. Olga L. B r a d h a m ................. 10

Testimony of Herman Jackson ........................ 11

Specification of Error ................................ 11

ARGUMENT.............................................. 12

Denial of Negro Publications to Negro

Prisoners While White Prisoners Are Permitted to Receive White Publications

Violates the Fourteenth Amendment.................... 12

Conclusion.............................................. 22

TABLE OF CAGES

Adderly v. Wainwright, No. 67-298 Civ. J. (M.D. Fla.) . . 1

Board of Managers v. George, 377 F.2d 288 (8th Cir.

1967) cert. den. 36 U.S.L. Week 3144................ 20

Burnside v. Byars, 363 F.2d 744 (5th Cir. 1966) ........ 21

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U.S. 714

(1961).............................................. 18

Cochran v. State of Kansas, 316 U.S. 255 (1942) ........ 19

Cooper v. Pate, 373 U.S. 546 (196 5 ) ................... 19

Fulwood v. Clemmer, 111 U.S. App. D.C. 184, 295 F.2d

171 (1961)................ 18

Hawkins v. North Carolina Dental Society, 355 F.2d

718 (4th Cir. 1966) ............................ 17, 13

Hunt v. Arnold, 172 F. Supp. 847 (N.D. Ga. 1959)........ 18

Lamont v. Postmaster General, 331 U.S. 301 (1965) . . . . 21

i

Page

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965)........ 18

Ludley v. Board of Supervisors, 150 F. Supp. 900 (E.D. La. 1957) affirmed 252 F.2d 372 (5th Cir.

1958) cert. den. 358 U.S. 8 1 9 ...................... 18

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184 (1964)............. 18

Meredith v. Fair, 293 F.2d 696 (5th Cir. 1962).......... 18

NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963).................... 21

Overseas Media Corp. v. McNamara, 36 U.S.L. Week 2217 . . 21

Pierce v. La Vallee, 293 F.2c1 233 (2nd Cir. 1961) . . . . 19

Rivers v. Royster, 360 F.2d 593 (4th Cir. 1966) ......... 17

Roth v. United States, 354 U.S. 476 (1957).............. 20

Sewell v. Pegelow, 291 F.2d 196 (4th Cir. 1961) ......... 19

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948).................. 18

Singleton v. Board of Commissioners, 356 F.2d

771 (5th Cir. 1966) ................................ 20

Smith v. Morrilton, 365 F.2d 770 (8th Cir. 1966)........ ' 18

United States v. Logue, 344 F.2d 290 (5th Cir. 1965). . . 19

United States v. Mississippi, 339 F.2d 679 (5th

Cir. 1964).......................................... 13

United States v. Wilbur Ward, 345 F.2d 857

(5th Cir. 1965) 13

Washington v. Lee, 263 F. Supp. 327 (M.D. Ala. 1966)probable jurisdiction noted 13 L.ed. 2d 988 (1967) . . 20

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 113 U.S. 356 (1886)................ 14

STATUTES AND REGULATIONS INVOLVED

Fla. Stat. Ann. §945.21 (1) (j).......................... 6

Rule 190A-3.403 (2)..................................... 6

Rule 190A-3.403 (3)..................................... 3

Rule 190A-3.406 (4)..................................... 3

ii

/

IN FORMA PAUPERIS

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 25299

HERMAN JACKSON, JR.,

Appellant,

v.

JAMES B. GODWIN, Assistant Superintendent,

Florida State Prison, Raiford, Florida,

Appellee.

Appeal from the United States District Court for

the Middle District of Florida

BRIEF FOR AiPPELLANT

Statement

Appellant Herman Jackson, a 27 year old Negro, has been a

prisoner for the past seven years at the Florida State Prison1/ 2/under sentence of death for the crime of rape (Tr. 64, 75). He

1/ Jackson's sentence has been stayed pending disposition of a

class action brought on behalf of all Florida prisoners under

sentence of death challenging various aspects of administration

of the death penalty by the State, Adderly v. Wainwright,

No. 67-298, Civ. J. (M.D. Fla.).

2/ Citations to the typed transcript of trial are shown as (Tr.).

Citations to (R.) is employed for the remainder of the record.

is lodged in the prison's maximum security area, the East Unit,

which has a population of about 1,100 or about one-third of the

prison's total population of 3,200. Approximately one-half of

the prisoners in the East Unit are Negro (Tr. 8, 9). During

1966, Jackson subscribed out of his own funds to the Courier

(R. 22), a weekly newspaper which presents news and features of

special interest to the Negro reader. The paper is referred to

interchangeably in the record as the Pittsburgh and Florida Courier,

published in Miami as the Florida edition of the Pittsburgh Courier.

(R. 22; Tr. 41). Apparently Jackson subscribed with the knowledge

of prison authorities for a permit is required (Tr. 31).

When he received only a few issues of the Courier during the

first six weeks of the subscripttion (R. 22), Jackson wrote a

letter to Mr. James E. Godwin, superintendent of the East Unit,

requesting that his subscription be continued and also that he be

permitted "to order two black magazines, namely Ebony and Sepia,

of which neither is subversive, but rather clean, educational and

informative literature" (R. 7). Jackson claimed that white inmates

were permitted to receive publications directed to white readers.

Without intending "to be disrespectful. . . in any manner", he

urged that it violated his rights to deny him publications oriented

to the Negro reader (R. 7):

" . . . since I'm a black man I enjoy reading

black literature, just as much as a white

man enjoy (sic) reading white literature, and

. . . inasmuch as white inmates are permitted

to receive white magazines and newspapers I

think I am entitled to black magazines and

newspapers so long as they're not of a subver

sive nature."

- 2

Godwin wrote Jackson denying both these requests. As

Jackson had been a resident of West Palm Beach, Florida prior to

his incarceration, he could not subscribe to the Courier because

"only hometown newspapers are permitted to any inmate on death

row" (R. 6). No explanation was given as to why Jackson would

not be permitted to subscribe to Ebony and Sepia other than the3/

statement that white inmates are not permitted "to have Esquire."

On September 20, 1966, Jackson filed a handwritten petition

invoking the jurisdiction of the district court under 42 U.S.C§

1983 to enjoin the assistant superintendent from unconstitution

ally refusing to permit him and other Negro inmates from ordering

"black newspapers, magazines and books" (R. 5-12). In his peti

tion Jackson alleged that (R. 6-10):

(1) he had requested permission to receive the Pittsburgh

Courier, Ebony and Sepia;

(2) his reauest had been denied;

(3) Mr. Godwin's statement in his letter that inmates could

3/ Godwin's reply states;

TO: Jackson, Herman, £000494, CM

R-2-N-17

Jackson:

No one is depriving you of your civil rights or any other

eights accorded men on death row. Only hometown newspapers

are permitted to any inmate in death row and that includes

white inmates. This applies to colored magazines such as

Ebony, which are not permitted nor do we permit white inmates

on death row to have Escruire.

You may not have the Pittsburgh Courier for in no place in

your jacket is there any indication your hometown is Pittsburgh

or have ever even been there (R. 6).

3

only receive a newspaper from their hometown was incorrect as he

had received "white" newspapers which did not come from his home

town, to wit, the Washington Post for three months, the Tampa

Tribune-Times for 9 months, the Gainsville Sun for 4h months and

the St. Petersburgh Times for three months;

(4) inmates were allowed to receive the Amsterdam News until

the prison officials discovered that it was a Negro newspaper;

(5) inmates receive only "white" newspapers;

(6) the only six magazines available to prisoners — National

Geographic, Field and Stream. Outdoor Life, Readers Digest, Red

Book and Cosmopolitan — were oriented to the white reader; and

(7) as a result of being compelled to read "white" literature,

he was uninformed about the Negro community (R. 9-10).

On December 7, 1966 the district court granted Jackson leave

to proceed in forma pauperis and issued an order to show cause

"why the injunction should not stand" (R. 13).

Respondent moved to dismiss the petition February 6, 1967 on

the grounds that it failed to state a cause of action; that the

magazines and periodicals sought induce lack of security because

they incite and stimulate in an unhealthy manner;and. that control of

prisoners' reading material is within the discretion of the custo

dian of the prison (R. 14-16). It was also alleged Jackson had

failed to exhaust his state remedies (R. 15-16).

In a pleading answering the motion to dismiss, Jackson

alleged that as he complained of a violation of his constitutional

rights, he was under no duty to exhaust the state's judicial

4

remedies before resorting to the federal courts; and that in any

event to seek relief in the Florida courts would be "entirely

futile", as the Florida Supreme Court had on a prior occasion

refused to consider his petition for the relief demanded in the

present action (R. 13-19). He denied that the Courier, Ebony and

Sepia would in any way induce, incite or stimulate in an unhealthy

manner. On the contrary, they were educational and informative

publications (R. 21).

On March 15, 1967, the district court denied the motion to

dismiss and appointed Earl Johnson, Esquire, of Jacksonville,

Florida as counsel for Jackson (R. 17).

In a response to the order to show cause respondent alleged

once more that the "magazines and periodicals which the petitioner

seeks are of a known character to induce lack of security within

the penal system because of their nature to incite and stimulate

in an unhealthy manner", (R. 30, 31). None of the other factual

allegations in the petitioner's complaint were denied.

Trial was held August 9, 1967 and the following evidence was

adduced.

Testimony of James B. Godwin

Mr. Godwin testified that the Superintendent of the Institu

tion and the Director of the Division of Correction had authorized

him to establish a prescribed list of reading material for inmates

4/(Tr. 9). Godwin explained that a committee — consisting of the

4/ Under section 944.11 of Florida Statutes Annotated, the Board

of Commissioners of State Institutions is authorized to adopt

such regulations as it may deem proper to govern the admission

of educational and other reading material within the state

5

Chief Classification Officer, the Chief Correction Officer, and

the Chaplain — had the responsibility of selecting magazines for

the inmates in the East Unit (Tr. 10). This committee did not

operate under any particular guidelines other than to exclude

magazines which, in their view, were either "sexy" or would raise

security or disciplinary problems among the inmates (Tr. 12-13).

They sought magazines which would be "uplifting", "entertaining

and educational." In selecting these magazines no attempt was

made to include any intended for or of interest to Negro inmates

(Tr. 11, 12, 20), even though one-half of the unit's population

is Negro (Tr. 9):

Q. Do you happen to recall whether any

magazine or periodical or newspaper

was permitted which, you might say,

was oriented toward the Negro reader?

A. Really, I don't know as they were ever

considered on that basis; we didn't

even consider that. We just assumed

that — .

At first, Mr. Godwin testified that he did not recall if Ebony or

Sepia had been considered for inclusion or. the list (Tr. 13-14) ,

4/ (Con't) institutions for the use of prisoners. Under section

945.21 (1)(j) the Board is authorized to adopt and proru ilgate

regulations relating to mail to and from inmates.

The Board adopted Rule 190A-3.403 (2) which provides for the censorship of inmates’ mail; Rule 190A-3.403 (3) which g...ves the

administrative head of the prison the right to refuse to send

or receive any prisoners' mail, when, in his opinion, such mail

would be detrimental to good order or discipline; and

190A-3.406(4) which grants the Director of the Division of

Corrections authority to set up a specific list of reading

material which may be admitted in the correctional institu

tions of the State of Florida. These regulations are found in

the record at pages 37, 41.

6

but then testified that he had been told the Committee had

considered them although he had not been present at the time

(Tr. 15).

According to Godwin, Jackson's request for the Couri.er was

denied because inmates are only permitted to receive newspapers

from their home town (Tr. 27, 57, 14). Jackson would be permitted

to receive the Pittsburgh Courier only if he were from Pittsburgh

and the Florida Courier only if he were from Miami (Tr. 41, 42;

R. Despite the assertion that Jackson could not receive the

Couri r because of the heme town rule, Godwin expressed a reserva

tion bout the Florida edition. He had never read the Pittsburgh

edition (Tr. 14). He stated that three front page pictures

depicting rioters in the June 24, 1967 issue (Resp. Exh. 5) would

have a detrimental effect on prison discipline (Tr. 42-43). He

conceded, however, — and the court took judicial notice — that

"all of the daily newspapers" carried similar pictures and stories

of riots (Tr. 43, 97). The record also shows that the home town

rule is not strictly enforced with respect to white publications;

three white Florida papers are available at the prison canteen;

and Jackson received the Washington Post and other white papers

for short periods (Tr. 16, 69, 70, 77).

According to Godwin, Jackson was not permitted to subscribe

to Ebony and Sepia because they were not on the prescribed list

which included only U.S. News and World Report, Reader's Digest,

Saturday Evening Post, Sports Illustrated, Picket Cross T,T..rd

Puzzles, National Geographic, and Outdoor Life (R. 39).

7

Restrictions on the number and character of the magazines were

necessary, in his opinion, because the prison staff was not large

enough to screen every magazine (Tr. 18). Such screening was

required because some might contain articles which might incite

(Tr. 23) and because "there have been reports of jails in Florida"

(emphasis supplied) receiving publications impregnated with LSD

(Tr. 23, 29).

Godwin testified that Ebony was objectionable, although not

generally a "sexy or spicy" publication (Tr. 19), because it

occasionally contained articles which would lead to racial diffi

culty in the prison (Tr. 19). He could net, however, recall any

specific picture or article which he though was detrimental

(Tr. 19-20). When confronted with the March 1967 issue of Ebony

(Resp. Exh. 3), Godwin found objectionable an editorial entitled

"Needed — More Human Communication" (p. 109) and an accompanying

picture "showing Negroes apparently rioting" (Tr. 45). The

editorial bemoans the lack of communication between the races,

and between men of the same race, and expresses the hope that

through true communication man will be able to work for the

betterment of all.

When confronted with the Fpril 1967 issue of Sepia (Fosp.

Exh. 4) Godwin stated that this issue would be detrimental to

prison discipline because it contained "spicy" pictures. He

referred specifically to an advertisement on page 31 which contains

a small line drawing of a man and woman embracing (Tr. 39 -40).

He admitted that the Saturday Evening Port — one of the

8

publications on the prescribed list — contained pictures of

women, but said that they were of a different nature from those

contained in Sepia (Tr. 52, 53). Pictures of women, he stated,

"would not be detrimental. . . to security; but it just is some

thing that we feel doesn't have its place in a prison where men

are confined by themselves" (Tr. 52).

On redirect examination Godwin was shown the August 7, 1967

issue cf Newsweek (Pet. Exh. B) and the August 7, 1967 issue of

U.S. N-ws and World Report (Pet. Exh. C). Newsweek had been on

the approved list of six publications, and was still considered

an ac!' . ptable publication, and U.S. News and World Report was

presently on the list (Tr. 92). He was referred to an article on

page 18 of Newsweek, entitled "American Tragedy, 1967 - Detroit",

and to accompanying pictures which shewed “a picture of the Detroit

riots, showing quite a bit of chaos in the streets, and destruc

tion" (Tr. 93). He was also referred to an article on H. Rap

Brown in the August 7, 1967 issue of U.S. hews and World Report.

He stated that, although these were "approved" publications, the

articles were the type which he preferred that prisoners did not see

(Tr. 95).

Testimony of Eric 0. Simpson

Mr. Simpson is publisher of the Florida Star a newspaper with

a circulation of between ten and seventeen thousand directed to

the Negro reader (Tr. 80). He stated that Ebony, Sepia, and. the

Pittsburgh Courier were oriented to the Negro reader, and described

these publications as educational and informative. He was not

9

aware of anything printed in either likely to induce riot or incite

disorder. On the contrary, his opinion was that Ebony would help

to create a very good state of mind for Negroes because "it shows

some of the better things that the Negroes can be proud of — some

of their activities, other than that you would see in, particularly,

the white press" (Tr. 82-83).

Testimony of Mrs. Olga L. Bradham

Mrs. Bradham, a librarian for more than thirty years in

school, university, and public libraries, and a holder of a

Master's Degree in Library Science, testified that Ebony and the

Pitt, burgh Courier were available to the public in the Jacksonville,

Florida Public Library (Tr. 34-85). Sepia, which she found unob

jectionable, was not available solely because of "budgetary

reasons" (Tr. 35). It was her opinion based on her experience

as a librarian that the Pittsburgh Courier and Ebony were among

the best Negro publications in the country (Tr. 85-86). She

described Ebony as being comparable in terms of quality to Life

magazine except that Ebony reported the accomplishments of Negroes,

and items which were of special interest to Negroes. She stated

that such articles were not available in white oriented magazines

(Tr. 86-87).

Testimony of Mrs. Gwendolyns Chandler

Mrs. Chandler, a librarian for three years with the

Jacksonville Public Library corroborated Mrs. Bradham's opinion

of the unobjectionable nature of the Negro publications. She

stated that Ebony was one of the best magazines available and

found nothing in it which would contribute to social disorder

10

(Tr. 83-89).

Testimony of Herman Jackson

Appellant testified in his own behalf that he would like to

read Ebony, Sepia and the Pittsburgh Courier because these pub

lications contained articles which cannot be found in the

literature which is now permitted to the prison population — one

half of which is Negro. He had pleaded with prison officials to

permit him this literature but all his requests had been denied

(Tr. 66-67). He criticized the West Palm Beach newspaper which

he was permitted to receive because it never carried any news

about Negroes except when arrested or when there was a riot

(Tr. 68). Jackson admitted that he had not read his home town

papers recently because he had been able to obtain copies of

out-of-town newspapers — the Atlanta Constitution and Journal,

Tampa Times-Tribune, Washington Post, and the Gainesville Sun for

short periods of time (Tr. 69-70). When he filed his petition in

the present case, the receipt of these papers was terminated

(Tr. 71).

In an August 5, 1967 opinion, the district court denied

relief holding "petitioner has failed in his burden to shov; that

the practices complained of are manifestly discriminatory in

violation of 42 U.S.C. §1983” (R. 45). The court granted leave

to appeal in forma pauperis on September 20, 1967 (R. 51).

Specification of Error

The court below erred in failing to hold that denia >. of

publications written for a Negro audience to Negro prisoners while

11

white prisoners are free to receive white publications deprives

appellant of due process of law and equal protection of the laws

as guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of

the United States.

ARGUMENT

Denial of Negro Publications to

Negro Prisoners While White Prisoners

Are Permitted to Receive White

Publications Violates the Fourteenth

Amendment.

Although one-half of the approximately 1100 prisoners in

appellant's unit are Negro (Tr. 8, 9) no attempt has been made to

assure them access to some newspaper or magazine intended for a

Negro audience. Assistant superintendent Godwin testified that

race was not considered in determining publication policy;

inquiries were not made of Negro prisoners. (Tr. 11, 12, 20)

As a consequence, Negro prisoners may obtain only periodicals

written for a white audience except if a Negro prisoner happens

to come from one of the relatively few communities which have

Negro newspapers. Even the latter possibility appears unlikely

given Godwin's objection to every Negro publication presented to

him at trial; appellant's uncontroverted allegation that the

Amsterdam News was denied to inmates after prison authorities

learned it was a Negro publication (R. 8); and the fact certain

white - but not Negrc-papers are generally available to inmates.

According to prison authorities, however, the only reason

why appellant is unable to subscribe to the Pittsburgh or Florida

12

Courier, its Miami published Florida edition, is that his home town

is West Palm Beach, Florida, not Pittsburgh or Miami. (See Resp.

Exh. 1; Tr. 27, 41, 42, 57) At the outset we note that the

policy permits appellant to obtain the Courier if he were

from Miami which is only 50 miles from West Palm Beach, Florida.

Secondly, Godwin raised no serious administrative justification

for refusing to permit appellant to receive a newspaper not

published in his home town.

Q. Generally, you try to restrict the inmates

no ordering newspapers from somewhere in this general

vicinity. Is that correct?

A. Yes, we feel that their interest would be more

apt to be in their home town - something like of that

nature. So we restricted that; there has to be a point

to cutoff somewhere, and we felt that this was the

most fair way to decide (Tr. 18).

No reason was offered why a reasonable alternative to the home town

restriction would not be to permit Negro prisoners to select one

Negro paper of their choice, or even one Florida Negro paper of

their choice, instead of a home town white paper. Thirdly, although

Godwin objected to one article in the Courier because it reported

recent riots, (Tr. 42-43) the district court took judicial notice

that any newspaper would contain material similar to the article

which was found objectionable. (Tr. 97) Finally, the record con

tains numerous instances in which the rule was not strictly applied

enabling prisoners to obtain white newspapers even if not from their

13

home town (Tr. 16, 69, 70, 77,); (R- 6-10) cf. Yiĉ c Wo v̂ .

Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886).

The two Negro magazines which Jackson sought, Ebony and Sepia,

are distinguished from the six magazines on the approved list sole

ly by reason of the fact that they picture and describe the

activities of Negroes. We invite the Court's consideration of

the issues of these publications which are in the record. The

April and August 1967 issues of Sepia (Resp. Exh. 4, Pet. Exh.A)

and the March Ebony (Resp. Exh 3) feature articles about Negro

politicians, entertainers, sports figures, scientists and re

ligious leaders. News of the civil rights movement is promiment;

e.g. "Little Rock Ten Years Later" ("After a decade of painful

transformation from bigotry and ignorance 'city of hate' emerges

with dignity and pride") (Pet. Exh. A). The tone is conventional;

layout familiar. Editorial policy is restrained. Not a word in

either publication encourages or condones use of violence or crime

as a solution to the problems of the American Negro. On the

14

contrary, the prevailing ethic is that only through hard work

and political organization have Negroes been able to make progress.

Coverage of riots seem somewhat more restrained than that found in

U.S. News and World Report and Newsweek — two "approved" publica

tions which have been made part of the record (Pet. exh. B, C).

A Negro newspaper publisher and two librarians testified that the

Negro publications were informative and educational and that they

were either available or qualified to be available at Jacksonville,

Florida Public libraries. (Tr. 80, 82-89) In short, the cnly thing

which distinguishes Ebony and Sepia from "approved" publications is

that they are written about Negroes, with a point of view aimed at

a Negro audience.

With respect to the Negro magazines — as opposed to the

home town rule — various administrative justifications for ex

clusion were raised. None bears scrutiny. It was said that news

and picture reports of riots were found in Ebony and Sepia and

that such stories might harm prison discipline. (Tr. 19, 43, 55)

It is obvious, however, as the district court noted and Godwin

conceded, that the reading matter presently available to inmates also

containssuch material (Tr. 48, 95, 97) (See e.g.. Pet. Exh. C).

It was said that the magazines contained material which would have

to be screened out (Tr. 23) and that the prison did not have the

personnel to do this on a large scale. (Tr. 35) It was conceded,

however, that the presently "approved" white publications also have

to be screened (Tr. 99-100). There appears, therefore, ro reason

why Negro magazines could not be on the approved list and be

15

subjected to the same screening white publications receive to

eliminate the articles which prison authorities find objectionable

in those publications. Although in pleadings respondent alleged

that Ebony and Sepia "incite and stimulate in an unhealthy manner"

Mr. Godwin withdrew this allegation with regard to Ebony (Tr. 19).

He objected only to one small advertisement (Tr. 39) and one

picture of a tribal woman (Tr. 55) in two issues of Sepia. The

picture is of the sort which fills the pages of National Geographic

magazine, which is on the approved list. (Tr. 26)

Appellant readily concedes that deference is to be accorded

to the judgment of prison officials in formulating policy with

respect to receipt of periodicals. Indeed, prison authorities

could for disciplinary reasons deny entirely to any inmate, or to

5/all inmates, the opportunity of receiving periodicals. To concede

this, however, is not to say that any magazine or newspaper policy

may cloak racial discrimination, or that unsupported incantations

of the classic formula — "discipline", "security", "discretion" —

are sufficient to immunize the policy from scrutiny. Here the

discriminatory result is plain: the white half of the unit's 1100

population may choose among six magazines which reflect the values

and perspective of the dominant race; the Negro half does not

have the opportunity to select a magazine published for the Negro

5/ The disciplinary problems of the petitioner cannot, however,

justify the respondent's publication policy which applies to him

and all Negro inmates without regard to their disciplinary

record.

16

reader. All white prisoners who come from communities with news

papers are able to receive white newspapers; a Negro must come

from one of the Sew home towns with a Negro paper. While

Jackson may not receive a Negro paper from a city a few miles

away, certain white papers are available to inmates regardless

of their home town. In selecting publications prison authori

ties made no attempt to consider the reading interest of Negro

inmates.

On the other hand, reasonable alternatives which do not burden

Negro inmates exist; they could be permitted to receive one Negro

newspaper instead of a "home town" white paper and a Negro maga

zine selected for quality by prison officials. In such circum

stances, we submit that respondent must at least come forward with

a justification for exclusion of publications directed to Negro

readers sufficient to negate the inference of racial discrimination.

None has been supplied. Even in its prisons the state may not

adopt a rule which burdens a Negro but not a white in the exercise

of a right or privilege.

With respect to the issue before this Court, the Fourth

Circuit has held that a general denial of Negro publications to

Negro prisoners, while white prisoners are free to obtain white

publications, denies Fourteenth Amendment rights to a state

prisoner. Rivers v. Royster, 360 F. 2d 593 (4th Cir. 1966). While

Rivers was decided on pleadings, the cases confirm that the marked

discriminatory effect shown here establishes unconstituticnal action.

In Hawkins v. North Carolina Dental Society, 355 F.2d 718, 723

17

(4th Cir. 1966) for example, the Fourth Circuit struck down a re

quirement, although facially non-racial, that a Negro applicant

obtain a recommendation from two of 1214 white dentists in order

to be admitted to a State dental society. I-Iawkins relied on this

Court's decision in Meredith v. Fair, 298 F.2d 696, 701, 702 (5th

Cir. 1962), where a state university sought to justify rejection of

a Negro on the ground that he had not furnished required certifi

cates of good character from five alumni, all of which were white.

Such a requirement was a violation of the equal protection of the

law because it imposed " a heavy burden on qualified Negro students,

because of their race." Similar requirements were invalidated in

Ludley v. Board of Supervisors, 150 F. Supp. 900 (E.D. La. 1957),

affirmed 252 F.2d 372 (5th Cir. 1958), cert. den. 358 U.S. 819,

and Hunt v. Arnold, 172 F. Supp. 847, 849 (N.D. Ga. 1959). See

also. United States v. Wilbur Ward, 345 F.2d 857 (5th Cir. 1965);

United States v. Mississippi, 339 F.2d 679 (5th Cir. 1964);

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965); Smith v. Morrilton,

365 F.2d 770 (8th Cir. 1966).

The severe discriminatory consequences of the home town rule

and the total exclusion of Negro magazines are a violation of the

Constitution. "Equal protection of the laws is not achieved by

indiscriminate imposition of inequalities" Shelley v. Kraemer,

t/334 U.S. 1, 22 (1948); McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184 (1964)

6_/ Nor may respondent take refuge in his presumed good faith.

"It is of no consolation to an individual denied equal pro

tection of the laws that it was done in good faith" Hurton

v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U.S. 714, 725 (1961).

18

i

United States v. Logue, 344 F.2d 290 (5th Cir. 1965), is an

instructive decision. There this Court held invalid a requirement

that required vouchers for applicants registering in a county where

no Negroes had been registered. The voucher requirement "inevi

tably imposes a greater burden on Negroes than whites under exist

ing dominant social patterns" and by reason of "imposing as it does a

heavier burden on Negroes than on white applicants is inherently

discriminatory as applied." (344 F.2d at 292). The Court did not

inquire into the purpose of the voucher rule; rather, it focused

on the rule's effect and found that it fell more heavily on

Negroes than on whites. The "dominant social patterns" in this

case result in few of the home towns of Negroes having papers

which feature news about Negroes while most all whites come from

home towns with white newspapers. They also result in white prison

officials selecting only white magazines and rejecting, without

convincing justification, comparable Negro publications, although

half of the potential readers are Negroes.

Although as the district court put it "it is not the duty of

the federal courts to supervise the general administration of

state prisoners" (R.45) it is well established that "prisoners do

not lose all their constitutional rights, and that Due Process and

Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment protect against

Vunconstitutional action on the part of prison authorities." And it

7/ Cooper v. Pate, 378 U.S. 546, (1965); Cochran v. State of

Kansas, 316 U.S. 255, (1942); Sewell v. Pegelow, 291 F.2d

196 (4th Cir. 1961); Pierce v. La Vallee, 293 F.2d 233

(2nd Cir. 1961); Fulwood v, Clemmer, 111 U.S. App. D.C.

184, 295 F.2d 171 (1961).

19

9

is unmistakably clear that "racial discrimination by governmental

authorities in the use of public facilities cannot be tolerated"

Washington v. Lee, 263 F. Supp. 327 (M.D. Ala. 1966), probable

jurisdiction noted 18 L. ed. 2d. 988 (1967). See also Board of

Managers v. George 377 F.2d 288 (8th Cir. 1967) cert. den. 36

U.S.L. Week 3144;Singleton v. Board of Commissioners, 356 F.2d 771

(5th Cir. 1966). Even considerations of prison security or

discipline do not permit the state to distinguish racially save in

the most extraordinary and compelling circumstances and such

considerations never permit the state to follow a general practice

§/of arbitrary treatment based on race. Washington v. Lee, supra.

We submit that in his handwritten petition, drafted prior

to the appointment of counsel on his behalf, appellant Jackson

stated the principle which governs this case:

Petitioner realize the resoondent has under state law authority to regulate prisoners reading

literature, still petitioner thoroughly scrutinized

the Correctional Penal Code, and see (sic) law

giving him the authority to practice racial

discrimination nor to promulate racial discrimina

tory rules to regulate literature on a discrimina

tory basis, such as being exhibited in this instant (sic) (R. 10).

In a recent District of Columbia case a newspaper publisher

complained that the Secretary of Defense acted arbitrarily in re

fusing to permit its publication to be sold on Army bases in the

Far East. The Secretary claimed that the approval of publications

fell within the unreviewable discretion of the Department of Defense

8/ Indeed, the very premise on which respondents attempted

justifications rest — that magazines and papers of this

sort incite behavior — is subject to the greatest doubt,

see Roth v. United States. 354 U.S. 476, 501 (1957)

(opinion of Mr. Justice Harlan).

20

'4

and the district court agreed. In reversing, the court of appeals

held that even though there is no right to sell a publication at

army bases the Secretary may not act arbitrarily: "publishers of

newspapers may fairly claim to be governed by uniform standards"

Overseas Media Corp. v. McNamara, 36 U.S.L. Week 2217. If this

reasoning applies to the Secretary's discretion in governing the

military establishment, it surely applies to prison authorities

once they determine to permit inmates access to newspapers and

magazines.

The prison's publication policies should also be appraised

in light of the First Amendment. Rights of free speech and ex

pression necessarily include the right of freeaccess to publications

"The dissemination of ideas can accomplish nothing if otherwise

willing addressees are not free to receive and consider them. It

would be a barren marketplace of ideas that had only sellers and

no buyers." Lamont v. Postmaster General, 381 U.S. 301, 308 (1965)

(Brennan, J., Concurring). Concededly, the protections of the

First Amendment are relaxed in the case of prisoners, but as First

Amendment rights are involved government has the duty to confine

itself to the least intrusive regulation adequate for the purpose

of maintaining prison discipline and administration, NAACP v.

Button, 371 U.S. 415, 438, 439 (1963). Respondent has simply

failed to come forward with sufficient justification for generally

denying appellant access to Negro publications. See Burnside v.

Byars, 363-F. 2d 744 (5th Cir. 1966).

21

To sum up: The record shows that the prison's publications

policy treats Negroes harshly; that the policy was formulated

without consideration of the interests of Negro inmates; that

jus tifications given for exclusion of Negro publications are un

convincing; and that reasonable alternatives to the present

policy exist. Respondent should be ordered to permit appellant

and other Negro inmates similarly situated to receive Negro

newspapers and magazines.

CONCLUSION

WHEREFORE, appellant prays that the judgment below be

reversed.

V

EARL M. JOHNSON

625 West Union Street

Jacksonville, Florida

JACK GREENBERG

MICHAEL MELTSNER

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

Attorneys for Appellant

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

This is to certify that on the ____day of November, 1967, I

served a copy of the foregoing brief for appellant on the attorney

for respondent David U. Tumin by depositing same in the United

States mail, air mail, postage prepaid addressed to him at the

Capitol Building, Tallahassee, Florida.

Michael Meltsner

Attorney for Petitioner