Hill v. Franklin County Board of Education Brief for Intervening Plaintiff-Appellant

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Hill v. Franklin County Board of Education Brief for Intervening Plaintiff-Appellant, 1966. bae0833c-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1bfbdb31-8247-43de-aad6-c4faf1db873d/hill-v-franklin-county-board-of-education-brief-for-intervening-plaintiff-appellant. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

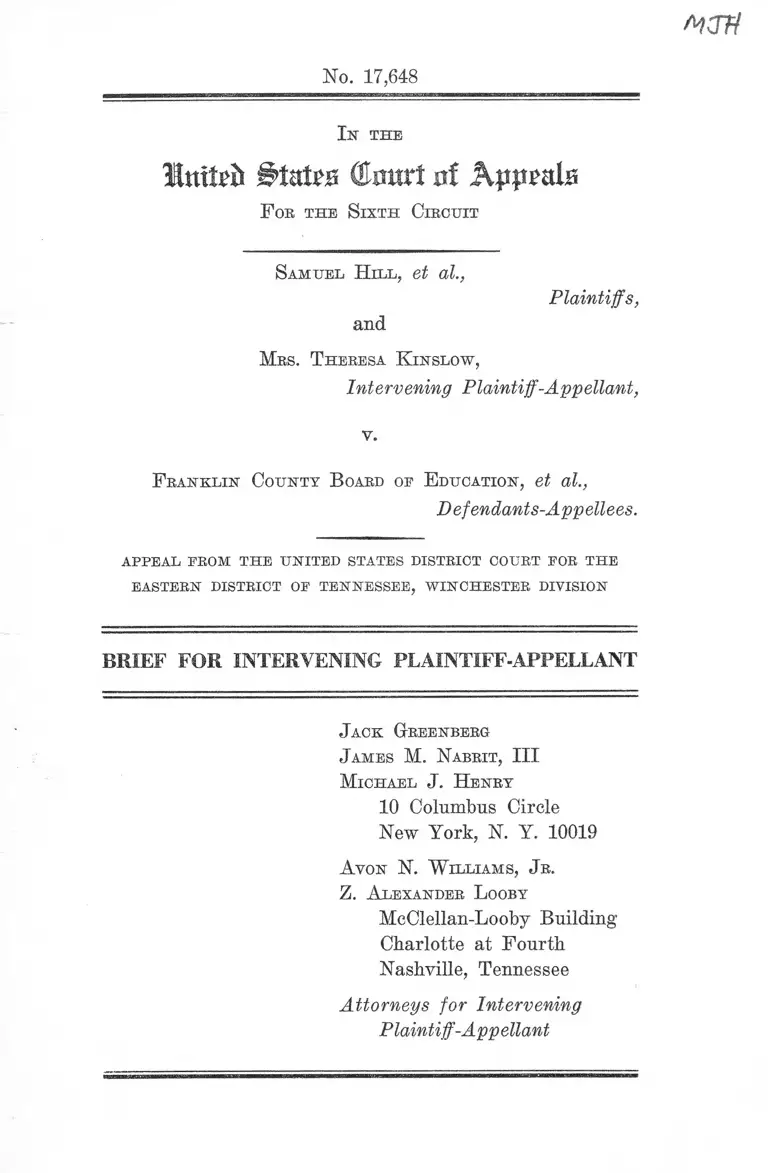

No. 17,648

I n t h e

Initial ( ta rt nf Appeals

F oe t h e S ix th Circu it

A) Jtf

S am uel H il l , et al.,

Plaintiffs,

and

M bs. T hebesa K inslo w ,

Intervening Plaintiff-Appellant,

y.

F r a n k lin C ounty B oabd of E ducation, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

appeal ekom t h e un ited states distbict couet eoe th e

EASTEEN DISTBICT OF TENNESSEE, WINCHESTEE DIVISION

BRIEF FOR INTERVENING PLAINTIFF-APPELLANT

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abeit, I I I

M ichael J . H enry

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

A von N. W illiam s , J r.

Z. A lexander L ooby

McClellan-Looby Building

Charlotte at Fourth

Nashville, Tennessee

Attorneys for Intervening

Plaintiff-Appellant

Statem ent o f Q uestion Involved

Whether plaintiff-appellant, whose application for a pub

lic school teaching position was denied, made out a prima

facie case that the denial was racially discriminatory,

which the school board did not rebut!

The district court answered this question “No” and

plaintiff-appellant contends the answer should have been

“Yes.”

I N D E X

PAGE

Statement of Question Involved ................ ........... Preface

Statement of F ac ts................... .................... ..... ........... 1

Argument .............................................................. ......... 9

Relief............................................... .............................. 18

T able op Ca ses :

Alston v. School Board of City of Norfolk, 112 F.2d

992 (4th Cir., 1940), cert. den. 311 U.S. 693 _____ 10

Avery v. Georgia, 345 U.S. 559 (1953) ......... ......... 16

Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond, 382

U.S. 103 (1965) ........................................ ................10,12

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) ....9,12

Chambers v. Hendersonville City Board of Education,

364 F.2d 189 (4th Cir., 1966) ...................... .....9,15,16

Colorado Anti-Discrimination Comm’n v. Continental

Air Lines, Inc., 372 U.S. 714 (1963) .................9,10,12

Eubanks v. Louisiana, 356 U.S. 584 (1958) ............... . 16

Franklin v. County School Board of Giles County,

360 F.2d 325 (4th Cir., 1966) ........................... . . . . . 11, 15

Garner v. Board of Public Works, 341 U.S. 716.......... 11

Johnson v. Branch, 364 F.2d 177 (4th Cir., 1966) ...... 10,16

11

PAGE

Konigsberg v. State Bar of California, 353 U.S. 252 .... 11

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587 (1935) ..................... 16

Reece v. Georgia, 350 U.S. 85 (1955) ........................ 16

Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965) ........................ 10,12

Schware v. Board of Bar Examiners, 353 U.S. 232 .... 11

Smith v. Board of Education of Morrilton School

District No. 32, 365 F.2d 771 (8th Cir., 1966) ___ 9,15

Torcaso v. Watkins, 367 U.S. 488 ............................... 11

United Public Workers v. Mitchell, 330 U.S. 75 .......... 9

Wieman v. Updegraff, 344 U.S. 183 ................... ......... 9

Zimmerman v. Board of Education, 38 N.J. 65, 183

A.2d 25 (1962) ...... ............................. ................... . 11

I n the

Imtpfc States Court of A t t a la

F ob th e S ix th Circuit

S amuel H il l , et al.,

Plaintiffs,

and

M r s . T heresa K inslow ,

Inter v enin g Plaintiff-A ppellant,

v.

F ra n k lin County B oard of E ducation, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

EASTERN DISTRICT OF TENNESSEE, WINCHESTER DIVISION

BRIEF FOR INTERVENING PLAINTIFF-APPELLANT

Statement of Facts*

This is an action in which Mrs. Theresa Kinslow inter

vened on behalf of herself and all other persons similarly

situated, against the County Board of Education of

* This case is one of three appeals—Nos. 17,647; 17,648; and 17,649—

arising from the same Motion for Further Relief and District Court

opinion. The respective parties have stipulated to file a, Joint Appendix

under this Court’s Rule 16(5), which will not be printed until after

briefs are filed under that rule. Thus the citations in this Statement of

Facts are to the typewritten transcript and other papers in the original

record on appeal, rather than to the subsequently printed record.

2

Franklin County, Tennessee, seeking relief against the

board’s policy and practice of denying, on the basis of

race, applications of teachers for employment.

Mrs. Theresa Kinslow had a B. S. degree, a Tennessee

Teacher’s Certificate in grades 1-9, and four years’ regular

and substitute teaching experience at the time that she

filed her application with the Franklin County School

System (Tr. 56-57). She had been a lifelong resident of

Franklin County, taking all of her public schooling there,

with the exception of the three years after graduating

from college that she spent in Kentucky (Tr. 55-57).

After returning to her home community in Tennessee

from Kentucky, she filed an application for a teaching

position in grades 1-9 with the Franklin County School

System on January 19, 1965 (Tr. 61). The application

form in use by the Franklin County School System at

that time had a space in which to indicate the race of

the applicant, and Mrs. Kinslow indicated therein that

she was a Negro (Application).

It was the practice in Franklin County that elementary

teachers were nominated for election by the particular

member of the Board of Education who resided in the

district in which the school was located for which the

teacher was being considered, and that the other members

of the Board would usually accept this recommendation

(Tr. 67, 102-105, 218-219, 246-247). Mr. L. J. Morris, the

member of the Board from the first district, in which

the formerly all-white Mary Sharp elementary school was

located, had determined in the summer of 1965 that there

was a vacancy in this school, and discovered through in

quiries that Mrs. Kinslow was available for the position

and had filed an application for employment with the

school system (Tr. 62-68, 242-248). Mr. Morris contacted

3

Mrs. Kinslow and suggested that she contact the super

intendent of the school system, Mr. Louis Scott (Tr. 63).

When she did so, Mr. Scott said that there was no vacancy

at the Mary Sharp School, since it had been filled earlier

in the summer (Tr. 63). Mrs. Kinslow then contacted

Mr. Morris again, who stated that there was a vacancy

there, since the person who had previously been considered

for it had refused to take it (Tr. 64). Mr. Morris then

suggested that Mrs. Kinslow send a transcript to the

superintendent, Mr. Scott, to supplement her previous

application, which she did (Tr. 65). Mr. Morris indicated

that he would recommend Mrs. Kinslow for the vacancy

at Mary Sharp School (Tr. 68).

Subsequently Mr. Morris discovered through conversa

tions with the superintendent and with other Board mem

bers that they were not going to go along with his recom

mendation of Mrs. Kinslow for the position at Mary

Sharp, although he did not know why, particularly since

they usually did go along with his recommendations (Tr.

246-247). He then inquired as to whether Mrs. Kinslow

would accept a position at the Townsend School (all

Negro), and indicated that he would attempt to obtain a

position for her there (Tr. 247).

At the Board of Education meeting on August 12, 1965,

Mr. Morris made a formal motion that Mrs. Kinslow be

employed at the Townsend School (Tr. 107). The Franklin

County School System at that time had adopted no formal

standards with which to determine which teachers should

be retained and/or employed (Tr. 91). When considering

Mrs. Kinslow’s application for a teaching position, the

Board never made a formal comparison of Mrs. Kinslow’s

qualifications with those of the other teacher applicants

(Tr. 152). The nature of the discussion which took place

at the Board meeting on the proposal to employ Mrs.

4

Kinslow concerned primarily the fact that the superin

tendent, Mr. Scott, had not recommended her (Tr. 107-

113). Mr. Scott stated that the reason he opposed Mrs.

Kinslow’s election was mainly because the principal of

the Townsend School had told him that he did not want

her there (Tr. 174). He nevertheless admitted that he

knew that Mrs. Kinslow had never done any teaching at

the Townsend School, and therefore there was no basis

for the asserted negative recommendation by the principal

of the Townsend School (Tr. 176-178). He also indicated

that he did not take the trouble at that time to write to

the school system which had previously employed her for

a written recommendation (Tr. 176, 196-197). As a result

of this conflict in recommendations, the vote of the Board

of Education on the proposal to elect Mrs. Kinslow to

fill the vacancy at the Townsend School was 3 in favor,

1 abstention, and 4 opposed, and therefore the motion

failed to carry (Tr. 107).

At the same time the Board of Education refused to

employ Mrs. Kinslow, the Board employed sixteen (16)

new white applicants for elementary positions, almost all

of whom had applied for positions with the system after

Mrs. Kinslow did, and many of whom had less experience

than she did, including four who had absolutely no teach

ing experience at all (Tr. 150-151, 188-190; Pre-trial Order

Information, Section III, Sub-section (d) (3)—-Non-Tenure

Teachers 1965-66; Exhibit No. 14—Applications of Teach

ers Employed 1965-66). The applicants employed by the

system for elementary positions during the summer of

1965 for the 1965-66 year are set out in the following

table:

5

N ew E lementary (G rades 1-8) T eachers E mployed for

1965-66 S chool Y ear

Name Degree

Teaching

Experience

Date of

Application Race

1. Broyles,

Minnie Mrs.

B. S.&7

sem. hours

6 years 1965 w

2. Cannon,

Frances Mrs.

B. S. 4 years 1965 w

3. Cunningham,

Dixie Mrs.

B.S. none 9/11/65 w

4. Fuller,

Angie Mrs.

B.S. none 7/28/65 w

5. Garner,

Marie Mrs.

90 quarter

hours

2 years 7/30/65 w

6. Hunter,

Frances Mrs.

B. S. & 3

quarter

hours

none 4/27/65 w

7. Martin, Homer

Wayne Mr.

B. S. & L. L. B. 4 years 1965 w

8. Moody,

Marion Mrs.

A. B. none 1965 w

9. More,

Novella Mrs.

B.C. 17 years 1965 w

10. Rose,

Nancy Mrs.,

B.S. 2 years 8/14/65 w

11. Running,

Julia Mrs.

MME 10 years 6/15/65 w

12. Skirven, MME 2 years 2/10/65 w

Martha Mrs.

6

N ew E lementary (G rades 1-8) T eachers E mployed for

1965-66 S chool Y ear

(Continued)

Name Degree

Teaching

Experience

Date of

Application Race

13. Soderbom,

Peggy Mrs.

B. S.&18

sem. hours

7 years 6/23/65 w

14. Soderbom,

Richard Mr.

B. A. 2 years

IJ. S. Army

6/23/65 w

15. Somerville,

Mary Mrs.

B.S. 2% years 1965 w

16. Wood,

Kathleen Miss

B. S. 1 year 5/1965 w

There were a number of other white applicants for elementary posi

tions for the 1965-66 school year who were not employed, but most of

these had less experience and qualifications than Mrs. Kinslow (Ex

hibit 13).

Eleven days after the Board of Education voted not

to employ Mrs. Kinslow, the Board met on August 23,

1965 and voted to discharge five Negro teachers from all-

Negro schools because of enrollment losses which occurred

in consequence of the implementation of a plan of desegre

gation (District Court opinion; Tr. 21-22, 224-226; Pre

trial Order Information, Section III, Subsection (d), p. 10

—Minutes of the Board of Education; Motion for Further

Relief, pp. 4-5). The school system did employ one new

Negro teacher during the summer of 1965 for the 1965-66

school year, but he was employed for the all-Negro Town

send High School (Tr. 165-166). It was the unwavering

policy of the Franklin County School System to assign

Negro teachers only to schools with exclusively Negro

student bodies through the school year 1965-66, even though

7

required to integrate the faculty under the Court ordered

plan of desegregation of April 1965 (Tr. 166).

In regard to the question of whether he made any in

vestigation of Mrs. Kinslow’s qualifications before deciding

against recommending her for a teaching position in the

summer of 1965, Superintendent Louis Scott produced no

affirmative evidence that he had made inquiries to officials

of the Christian County Kentucky School System in which

Mrs. Kinslow had been employed immediately preceding

her application to the Franklin County System (Tr. 174-

178, 196-197). T. K. Stewart, the superintendent of edu

cation of the Christian County School System stated in

August, 1966 that his recollection of the first telephone

conversation which he had had with Mr. Louis Scott was

only several months previously, which would place the

time at approximately the time of the filing of this lawsuit

in February, 1966, rather than during the summer of

1965 at the time of the consideration of Mrs. Kinslow’s

application (Stewart Deposition, p. 2). Mr. Stewart did

state that he gave Mrs. Kinslow an unsatisfactory recom

mendation after suit was filed, but this was based not on

his own personal knowledge of her qualifications but upon

impressions gained from the principal and the supervisor

of the school in wffiich Mrs. Kinslow was employed, Mr.

Rozzelle Leavell and Mrs. Idella Ervin (Stewart Deposi

tion pp. 4-5, 32-33). However, Mr. Leavell specifically de

nied that he had ever given an unsatisfactory recom

mendation of Mrs. Kinslow (Leavell Deposition, pp. 5, 15),

and stated specifically that she was an “excellent teacher”

(Leavell Deposition, p. 2).

The only written record which Mr. Stewart had indi

cating that Mrs. Kinslow had been an unsatisfactory

teacher was a letter which he had sent to the Kentucky

Human Rights Commission, in response to an inquiry as

8

to why the system had discharged so many Negro teachers,

all at the same time (Stewart Deposition pp. 4, 12-13,

25, 27). The Christian County School System had been

completely racially segregated up until the 1963-64 school

year, during which a freedom of choice desegregation plan

was begun (Stewart Deposition pp. 9-10). In consequence

of that plan of desegregation, the enrollment dropped at

the all-Negro Gainsville School at which Mrs. Kinslow

had been teaching, thereby causing the school system to

make a reduction in the number of teaching positions at

that school, at the same time that Mrs. Kinslow was

allegedly discharged for unsatisfactory teaching (Stewart

Deposition, pp. 10-11; Leavell Deposition, pp. 3-4). The

Christian County School System at this time was still

following an unwavering policy of complete faculty segre

gation, and did not begin faculty desegregation until the

1965-66 school year and did not assign any Negro teachers

to schools where they would be teaching white pupils

until that time (Stewart Deposition p. 11).

The District Court held a hearing in this case on August

25, 1966, and filed an opinion on September 30, 1966 deny

ing relief to Mrs. Kinslow, although granting relief to

another Negro teacher (Mrs. Virginia Scott) who was

discharged at the same time that Mrs. Kinslow was not

employed (District Court opinion).

9

ARGUMENT

Whether Plaintiff-Appellant, Whose Application lor

a Public School Teaching Position Was Denied, Made

Out a Prima Facie Case That the Denial Was Racially

Discriminatory, Which the School Board Did Not Rebut ?

The District Court Answered This Question “No” and

Plaintiff-Appellant Contends the Answer Should Have

Been “Yes.”

The mandate of Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.8.

483 (1954), forbids the consideration of race in faculty-

selection by a public school system just as it forbids it in

pupil placement. Chambers v. Hendersonville City (N.

Car.) Board of Education, 364 F.2d 189 (4th Cir., 1966).

This follows the Supreme Court’s holding in Colorado

Anti-Discrimination Commission v. Continental Air Lines,

Inc., 372 U.S. 714, 721 (1963), that “any state or federal

law requiring applicants for any job to be turned away

because of their color would be invalid under the Due

Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment and the Due

Process and Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth!

Amendment.” The Court of Appeals for the Eighth Cir

cuit specifically applied this holding to public school teach

ers in Smith tv. Board of Education of Morrilton School

District No. 32 (Ark.), 365 F.2d 771 (8th Cir., 1966),

when it held:

It is our firm conclusion that the reach of the Brown

decisions, although they specifically concerned only

pupil discrimination, clearly extends to the proscrip

tion of the employment and assignment of public school

teachers on a racial basis. Cf. United Public Workers

v. Mitchell, 330 U.S. 75, 100, 67 S.Ct. 556, 91 L.Ed. 754

(1947); Wieman v. Updegraff, 344 U.S. 183, 191-192,

10

73 S.Ct. 215, 97 L.Ed. 216 (1952). See Colorado Anti-

Discrimination Comm’n v. Continental Air Lines, Inc..

372 U.S. 714, 721, 83 S.Ct. 1022, 10 L.Ed.2d 84 (1963).

This is particularly evident from the Supreme Court’s

positive indications that nondiscriminatory allocation

of faculty is indispensable to the validity of a desegre

gation plan. Bradley v. School Board, supra; Rogers

v. Paul, supra. . . .

The Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit recently

had occasion to apply these basic Constitutional principles

in the case of a Negro teacher who was not rehired, al

legedly because of civil rights activity, Johnson v. Branch,

364 F.2d 177 (1966). In finding for the complaining Negro

teacher, the Court stated in its opinion that:

“The law of North Carolina is clear on the procedure

for hiring teachers. All contracts are for one year only,

renewable at the discretion of the school authorities. . . .

There is no vested right to public employment. No one

questions the fact that the plaintiff had neither a contract

nor a constitutional right to have her contract renewed,

but these questions are not involved in this case. It is the

plaintiff’s contention that her contract was not renewed

for reasons which were either capricious and arbitrary or

in order to retaliate against her for exercising her con

stitutional right to protest racial discrimination.

# # #

“In Alston v. School Board of City of Norfolk, 112 F.2d

992 (4 Cir., 1940), cert, denied, 311 TT.S. 693, 61 S.Ct. 75,

85 L.Ed. 448 (1940), this court struck down a practice of

paying lesser salaries to Negro school teachers. In that

case Chief Judge Parker said:

11

‘It is no answer to this to say that hiring of any

teacher is a matter resting in the discretion of the

school authorities. Plaintiffs, as teachers qualified and

subject to employment by the state, are entitled to

apply for the positions and to have the discretion of

the authorities exercised lawfully and without uncon

stitutional discrimination as to the rate of pay to be

awarded them, if their applications are accepted.’

# # #

“Again in Franklin v. County School Board of d ies

County, 360 F.2d 325 (4 Cir. 1966), this court ordered that

Negro teachers whose contracts were not renewed because

of their race be reinstated. There the Board contended

that they had, in the act of failure to renew the contracts,

compared the qualifications of the teachers with others

in the system and found them inferior, but the record

disclosed no objective evidence of such inferiority in the

face of equal certification and experience. However wide

the discretions of School Boards, it cannot be exercised

so as to arbitrarily deprive persons of their constitutional

rights. Zimmerman v. Board of Education, 38 N.J. 65,

183 A.2d 25, 27-28 (1962); Garner v. Board of Public

Works, 341 U.S. 716, 725, 71 S.Ct. 909, 95 L.Ed. 1317

(1951). The principle has often been applied in analogous

situations. Torcaso v. Watkins, 367 U.S. 488, 81 S.Ct.

1680, 6 L.Ed.2d 982 (1961); Schware v. Board of Bar

Examiners, 353 U.S. 232, 77 S.Ct. 752, 1 L.Ed.2d 796

(1957). In Konigsberg v. State Bar of California, 353

U.S. 252, 77 S.Ct. 722, 1 L.Ed.2,d 810 (1957), the Court said:

‘We recognize the importance of leaving the States

free to select their own bars, but it is equally im

portant that the State not exercise this power in an

arbitrary or discriminatory manner nor in such [a]

12

way as to impinge on the freedom of political ex

pression or association.’ (At 273, 77 S.Ct. at 733.)”

Thus it is clear that no matter how extensive the dis

cretion of school officials in determining whether or not

to employ a particular teacher, such employment decision

may not be made on an unconstitutional ground. It is

also clear that race is such an unconstitutional ground.

Brown v. Board of Education, supra; Bradley v. School

Board of Richmond, 382 U.S. 103 (1965); Rogers v. Paul,

382 U.S. 198 (1965).

In the instant case, when a Negro teacher applicant,

Mrs. Kinslow, filed her application form, she was required

to indicate thereon her race. In Colorado Anti-Discrim

ination Commission v. Continental Air Lines, Inc., 372

U.S. 714 (1963), the Supreme Court upheld a finding of

discrimination based on a requirement by an employer

that the racial identity of the applicant be revealed on an

application form. It is undisputed that the race of all

applicants for positions in the 1965-66 school year was

required by the Franklin County School System to be

stated on the application form. It follows logically that

if the school system asked for this fact on the applica

tion form, they used it in their decisions as to whether or

not to employ the applicants—which is clearly unconsti

tutional.

Even apart from this requirement to indicate race on the

application form, the evidence clearly established a prima

facie case of a refusal to employ based on race which the

school officials did not rebut. Mrs. Kinslow, a Negro, was

a certified elementary teacher of four years experience

who filed her application with the Franklin County School

System in January, 1965. She was recommended in the

summer of 1965 for a position at the formerly all-white

13

Mary Sharp School by the school board member in whose

district the school was located. Although the board’s nor

mal practice was to follow the recommendation of the

board member in whose district a school was located with

regard to hiring elementary teachers, in this case the

superintendent and the other board members deviated from

their normal practice and refused to follow that recom

mendation. Then Mrs. Kinslow was proposed for a posi

tion at the all-Negro Townsend School later in the sum

mer of 1965, but in order to be consistent with their

previous refusal to employ her for a formerly all-white

school, the superintendent and several board members

also acted to keep her out of this position, even though

other board members desired to employ her here.

The Franklin County School superintendent later claimed

that he had checked Mrs. Kinslow’s qualifications with

the Kentucky school system where she was previously

employed and had received a negative recommendation

from the superintendent of that system. Nevertheless,

there was no written inquiry made by the superintendent

in the summer of 1965 at the time of the decision, and the

Kentucky superintendent indicated that his earliest recol

lection of even a telephone inquiry from the Franklin

County superintendent was early in 1966. Furthermore,

the Kentucky superintendent later stated that he gave

Mrs. Kinslow an unsatisfactory recommendation based not

on his own direct impressions of her work (of which he

had none) but on those of the principal and supervisor

of the school where she taught in Kentucky. But, the

principal of that school testified and contradicted this di

rectly, saying that Mrs. Kinslow was an “excellent teacher.”

The only written evidence the Kentucky superintendent

could point to as justifying his unfavorable recommenda

tion was a letter he had been forced to send to the Ken-

14

tucky Human Rights Commission in response to an in

quiry as to why so many Negro teachers, including Mrs,

Kinslow, had been discharged at the same time, coinciding

with the implementation of a plan of student desegrega

tion in which there were substantial enrollment losses at

Negro schools.

At the same time that the Franklin County school

board was refusing to employ Mrs. Kinslow during the

summer of 1965, the board hired sixteen (16) new white

elementary teachers, twelve (12) of whom had less or no

greater experience and qualifications than Mrs. Kinslow

and almost all of whom filed their applications after she

did. The 1965-66 school year was the first year during

which the court-ordered freedom-of-choice student desegre

gation plan of April 17, 1965 applied and during which the

school system could anticipate substantial student desegre

gation. It had become clear at this point that any new Negro

teacher employed by the system might have to be assigned

to teach white students, since the number of students in

the all-Negro schools could be expected to decrease sub

stantially. Furthermore, eleven days after the board voted

not to employ Mrs. Kinslow, the school system discharged

five Negro teachers from all-Negro schools because of

enrollment losses which did materialize at the beginning

of the 1965-66 school year in consequence of the implemen

tation of the new court-ordered freedom-of-choice desegre

gation plan. It had been the unwavering policy of the

school system up to this time to assign Negro teachers

to teach only Negro students, and the only alternative

to discharging these now “excess” Negro teachers would

have been re-assigning them to formerly all-white schools

where they would be teaching some white students.

We submit that on this state of the facts, the district

court’s conclusion that there was “substantial evidence”

15

(which it does not specify) to support the school board’s

decision as being within the proper bounds of admin

istrative discretion and not arbitrary or founded on con

siderations of race, is clearly erroneous.

It is also completely inconsistent with same court’s de

termination in the same opinion that the discharges of

five Negro teachers at the same time as the refusal to

employ Mrs. Kinslow were wrongfully based on race, since

“the defendant Board had no definite objective standards

for the employment and retention of teachers which were

applied to all teachers alike in a manner compatible with

the requirements of the due process and equal [protection]

clauses of the federal Constitution.” There is no indication

that the board made any formal comparison according to

any Constitutionally permissible objective criteria of Mrs.

Kinslow’s qualifications with those of the other applicants

before declining to employ her.

The U. S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit has

specifically held in teacher discharge cases that the failure

to make comparative evaluations according to objective

standards among all person eligible for the available posi

tions is a Constitutional defect. Franklin v. County School

Board of Giles Co. (Va.), supra; Chambers v. Henderson

ville City (N. Car.) Board of Education, supra. The Eighth

Circuit has held similarly in the context of the imple

mentation of a plan of desegregation. Smith v. Board of

Education of Morrilton School District No. 32 (Ark.),

supra. There is no reason why this basic prohibition of

and protection against arbitrary conduct on the part of a

school board should not apply in the case of applications

as well as dismissals.

Furthermore, in view of the district court’s conclusion

in the same opinion that the defendant school board had

16

been guilty of “a long-continued pattern of evasion and

obstruction of the desegregation of the public schools of

Franklin County, Tennessee,” it was inconsistent of the

district court to cast the burden of proof of showing racial

discrimination upon Mrs. Kinslow in the first place. As

the Fourth Circuit said in Chambers v. Hendersonville

City (N. Car.) Board of Education, supra, in reference

to a comparative evaluation which allegedly had been made:

Finally, the test itself was too subjective to with

stand scrutiny in the face of the long history of racial

discrimination in the community and the failure of the

public school system to desegregate in compliance with

the mandate of Brown until forced to do so by litiga

tion. . . . Innumerable eases have clearly established

the principle that under circumstances such as this

where a history of racial discrimination exists, the

burden of proof has been thrown upon the party

having the power to produce the facts. In the field

of jury discrimination see: Eubanks v. Louisiana,

356 U.S. 584 (1958); Reece v. Georgia, 350 U.S. 85

(1955) ; Avery v. Georgia, 345 U.S. 559 (1953); Norris

v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587 (1935). 364 F.2d at 192-193.

Additionally, the Fourth Circuit specifically stated in

Johnson v. Branch, supra, that under such circumstances

even where a board maintains that they had compared the

qualifications of discharged teachers with others in the

system and found those of the discharged teachers in

ferior, the facts of equal certification and experience and

lack of objective evidence of inferiority in the record

require a finding that the board has acted arbitrarily and

unconstitutionally on the basis of race. The record in the

instant case shows that Mrs. Kinslow’s qualifications were

equal or superior to those of three-fourths of the white

17

applicants who were employed, and there is no reason why

this principle of burden of proof applied in teacher dis

charge cases in the context of implementation of desegrega

tion plans should not be applied to teacher applicants in

similar circumstances.

Thus in the summer of 1965 the Franklin County school

system was still requiring of teacher applicants that they

indicate their race on the application form; was facing

substantial student integration for the first time which

might require the assignment of Negro teachers to teach

white students; and in fact discharged five Negro teachers

when substantial numbers of Negro students transferred

from previously all-Negro schools rather than re-assigning

those teachers to integrated schools where there would

be white students. At the same time, the school system

refused to employ Mrs. Kinslow while hiring sixteen (16)

new white elementary teachers, three-fourths of whom had

less or only equivalent experience and qualifications; had

no definite objective standards for determining which teach

ers to employ and made no formal comparison of Mrs.

Kinslow’s qualifications to those of the other applicants;

and did not even make a formal written inquiry of her past

employers for recommendations. We submit that circum

stances such as these in the context of a long history of

past racial discrimination by this school system permit no

other conclusion but that Mrs. Kinslow was not employed

because of her race.

18

Relief

For the foregoing reasons, plaintiff-appellant respect

fully submits that the decision of the lower court should

be reversed, and that an order should be entered requiring

the school board to employ her, and to compensate her for

the income which she would have earned if the school

board had not wrongfully refused to employ her.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Gbeenbebg

J ames M. N abbit, III

M ichael J . H enry

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

A von N. W illiam s , J b.

Z. A lexander L ooby

McClellan-Looby Building

Charlotte at Fourth

Nashville, Tennessee

Attorneys for Intervening

Plaintiff-Appellant

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C « ^ P » 219