Belk v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education Page Proof Briefs of Appellees William Capacchione, Michael Grant, et al.

Public Court Documents

March 24, 2000

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Belk v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education Page Proof Briefs of Appellees William Capacchione, Michael Grant, et al., 2000. 479e1597-c69a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1c0410eb-7439-403f-9259-076c7416d42b/belk-v-charlotte-mecklenburg-board-of-education-page-proof-briefs-of-appellees-william-capacchione-michael-grant-et-al. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Copied!

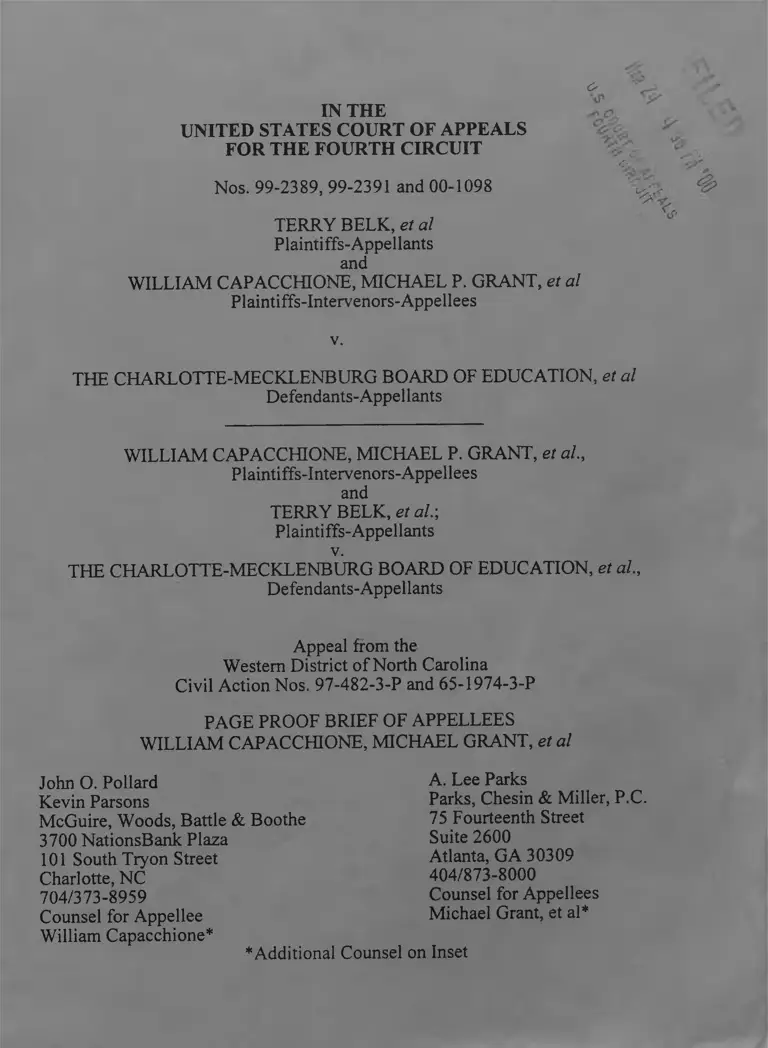

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 99-2389, 99-2391 and 00-1098

TERRY BELK, et al

Plaintiffs-Appellants

and

WILLIAM CAPACCHIONE, MICHAEL P. GRANT, et al

Plaintiffs-Intervenors-Appellees

v.

6

4O

THE CHARLOTTE-MECKLENBURG BOARD OF EDUCATION, et al

Defendants-Appellants

WILLIAM CAPACCHIONE, MICHAEL P. GRANT, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Intervenors-Appellees

and

TERRY BELK, et al.;

Plaintiffs-Appellants

v.

THE CHARLOTTE-MECKLENBURG BOARD OF EDUCATION, et a l,

Defendants-Appellants

Appeal from the

Western District of North Carolina

Civil Action Nos, 97-482-3-P and 65-1974-3-P

PAGE PROOF BRIEF OF APPELLEES

WILLIAM CAPACCHIONE, MICHAEL GRANT, et al

John O. Pollard

Kevin Parsons

McGuire, Woods, Battle & Boothe

3700 NationsBank Plaza

101 South Try on Street

Charlotte, NC

704/373-8959

Counsel for Appellee

William Capacchione*

A. Lee Parks

Parks, Chesin & Miller, P.C.

75 Fourteenth Street

Suite 2600

Atlanta, GA 30309

404/873-8000

Counsel for Appellees

Michael Grant, et al*

*Additional Counsel on Inset

Additional Appellee Counsel:

William S. Helfand

Magenheim, Bateman, Robinson,

Wrotenbery & Helfand

3600 One Houston Center

1221 McKinney

Houston, Texas 77010

713/609-7700

Counsel for Appellee William Capacchione

Thomas J. Ashcraft

212 South Tryon Street

Charlotte, NC 28281

704/333-2300

Counsel for Appellees Michael Grant, et al

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES................................................................................. vi

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT ........................................................................... 1

ISSUES PRESENTED ................................................................................................2

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT................................................................................. 3

STATEMENT OF THE C A S E ................................. 6

1. Procedural History: Original Violations

and Court Ordered Remediation .............. 6

2. CMS’ Historic Compliance with the Court Orders ............................... 10

3. Demographic Change in Charlotte-Mecklenburg and CMS

and the Impact on Student Assignm ent.................................................... 13

4. Demographic Change, School Siting and CMS Compliance ...............18

5. Compliance with the Faculty Balance Requirements............................... 20

6. Roughly Equal Transportation B urdens.................................................... 20

7. Demographic Change, Magnet School Transfers and Compliance . . . . 22

8. Facilities ..................................................................................... 23

9. R esources....................................................................................................26

10. CMS’ Magnet Schools and Rigid Racial Q uotas................................... 28

a. The Magnet Schools Were a Voluntary Desegregation

Plan Implemented To Counteract Demographic Change . . . 28

b. The Magnet Schools’ Rigid Racial Admission Q uotas........ 30

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT 34

ARGUMENT............................................................................................................ ...

I. THE STANDARD OF R E V IEW .................................................................38

A. Unitary S tatus....................................................................... .................... 3g

B. The Injunction..............................................................................................40

C. Sanctions Order and Attorneys Fees ...................................................... 41

II. THE FINDINGS OF FACT UPON WHICH CMS WAS DECLARED

UNITARY WERE NOT CLEARLY ERRONEOUS......................... .. 42

A. The District Court Properly Declared CMS Unitary

in Student Assignment ............................................................ .............. 47

1. Good Faith Compliance................................................................ 47

2. Racial B alance................................................................................. 51

3. School Siting ............................................................ .................... 54

4. The Consideration of White Flight by CMS In Adopting a

Voluntary Magnet School Program Was Proper ....................... 55

5. Transportation B urdens.................. 57

B. The District Court Properly Declared CMS Unitary In Faculty

Assignment..................................................................................................60

C. The District Court Properly Declared CMS Unitary

as to Facilities and Resources ...................................................................63

D. CMS Is Unitary As To Transportation............................... 66

E. The District Court Correctly Found No Vestiges of the Dual System to be

Adversely Impacting Student Achievement..............................................66

F. CMS Has The Burden of Proof on Issues Not Subject to the Remedial

O rd e r ............................................................................................................ 70

G. The Eleventh Hour Submission of a Theoretical “Controlled Choice”

Plan Did Not Require Extending Court Supervision...........................,7 2

ii

H. The District Court Correctly Interpreted The 1979 Martin Order __ 75

1. The Martin Order and Twenty Years of Compliance................. 77

III. THE INJUNCTION ......................................................................................80

A. The District Court Properly Held the Magnet School Program

Violated The Constitution and Awarded the Plaintiff Intervenors

Nominal Monetary and Injunctive R e l ie f .............................................. 81

1. Strict scrutiny applies to all government sponsored

racial classifications ............................................................................. 81

2. CMS’ magnet school lottery quotas violated prior court orders,

and were adopted to combat shifting racial residential demographics,

not as a good faith effort to comply with any court o rd e r ...............84

3. Strict scrutiny review applied to the magnet school lottery

regardless of whether it was a voluntary or involuntary race-based

classification..........................................................................................88

4. The District Court properly held CMS used the Swann Orders as a

pretext for unconstitutional racial balancing ......................................89

B. Nominal Damages Are Required For Constitutional Violations...........91

C. The District Court’s Injunction is a Measured, Properly Fashioned

Remedy for Unconstitutional Racial Quotas that was Well Within

its Discretionary, Equitable Pow ers........................................................ 94

1. Racial neutrality is the chief end of injunctions under the

Fourteenth Amendment .......................................................................94

2. Injunctions under the Fourteenth Amendment have been

characterized by flexibility, breadth and judicial deference

to trial courts ..........................................................................................95

3. CMS retains control over its school systems under the

injunction ......................................................................................... 96

4. The injunction is narrowly tailored to the violations.....................97

iii

D. The District Court Injunction Eliminated Both a Past Practice

and Prohibited Threatened Future H a rm ................................................ 98

1. CMS failed to satisfy the Court that it would not

continue its illegal conduct............................................................... 99

2. The District Court Injunction is Suitably Narrow ..................... 101

IV. THE DISTRICT COURT PROPERLY REJECTED “RACIAL

DIVERSITY” IN STUDENT ASSIGNMENT AS A COMPELLING

STATE INTEREST........................................................................................ 103

A. Sound Precedent Precludes Race-Conscious Policies To Either

Achieve Racial Diversity Or Avoid Racial Resegregation ................... 104

1. Acknowledging racial diversity as a compelling governmental

interest would render the Fourteenth Amendment incoherent . . . . 105

2. Racial diversity cannot be a compelling governmental interest

without eviscerating strict scrutiny.................................................. 108

3. Accepting racial diversity as a compelling state interest would

license the state to racially stereotype ............................................ 110

4. CMS’ interest in avoiding resegregation is neither compelling nor

warranted by the fac ts ......................................................................... 112

V. THE EVIDENCE AND CONTROLLING CASE AUTHORITY

OVERWHELMINGLY SUPPORT THE DISTRICT COURT’S RULING

THAT PLAINTIFF-INTERVENOR CAPACCHIONE WAS A

“PREVAILING PARTY” AND ENTITLED TO RECOVER ATTORNEYS

FEES ...............................................................................................................113

A. As an Intervenor in Swann, Capacchione is a “prevailing party” entitled

to attorney’s fees if his counsel significantly contributed to the result,

regardless of his Article III standing........................................................... 113

1. Capacchione significantly contributed to the Plaintiff-Intervenors

obtaining a favorable Judgment in this case.................................... 117

2. Farrar is distinguishable from this case....................................... 120

IV

B. The record clearly supports the judgment holding CMS liable on the

merits, making Capacchione a prevailing party entitled to attorneys’ fees,

notwithstanding the testimony of Susan Purser........................................123

1. The magnet admissions program employed inflexible racial quotas

and was therefore unconstitutional.................................................. 123

VI. THE DISTRICT COURT’S SANCTION OF CMS FOR FAILING

TO DISCLOSE MULTIPLE FACT WITNESSES DURING

DISCOVERY WERE REASONABLE, FAIR AND NOT AN ABUSE OF

DISCRETION................................................................................................ 126

CONCLUSION.........................................................................................................135

CERTIFICATE OF COMPLIANCE....................................................................... 136

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE 137

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES: Page

Adarand Constructors, Inc. v. Pena, 515 U.S. 200,

227 (1995)....................................................................... 81,84, 103, 107, 114

Alabama Nursing Home Ass'n v. Harris, 617 F.2d 385 (5th Cir. 1980) ............. 76

Alexander v. Estepp, 95 F.3d 312, 315-316 (4th Cir. 1996) ........... 83, 89, 105, 108

Anderson v. Bessemer City 470 U.S. 564, 573-74(1985)............... 39, 133, 78, 134

Bazemore v. Friday, 478 U.S. 385, 407-09(1986) .......................................... 65, 69

Board ofEduc. o f Oklahoma City v. Dowell, 498 U.S. 237,

249-250(1991) ................................. .................. 34 ,47 ,48 ,74 ,75 ,85 ,110

Bradley v. School Bd. o f Richmond, 462 F.2d 1058, 1064 (4th Cir. 1972) . . . 86, 92

Briton v. South Bend Community School Corp., 819 F.2d 766, 771-72

(7th Cir. 1987) ................................................................................................ 62

Brown v. Board o f Education, 349 U.S. 294, 300-01 (1955).....................passim

Buffington v. Baltimore County, Maryland, 913 F.2d 113, 135 (4th Cir. 1990)

cert, denied, 499 U.S. 906 (1991)............................................................... 132

Bush v. Vera, 517 U.S. 952 (1 9 9 6 )....................................................................... 103

Calhoun v. Cook, 525 F.2d 1203, 1203 (5th Cir. 1975)......................................... 74

Capacchione v. Charlotte-MecklenburgBd. ofEduc.,51 F.Supp. 2d 228

(W.D.N.C. 199 9 )................................................................................................passim

Cartwright v. Stamper, 7 F.3d 106, 109 (7th Cir. 1993) ................................... 122

vi

City o f Richmond v. J.A. Croson Co., 488 U.S. 469,

498 (1989)....................................................................... 72,83, 101, 106, 107

Coalition to Save Our Children v. State Bd. ofEduc. o f Delaware,

90 F.3d 752, 759 (3d Cir. 1 996 ).......................................... 39, 48, 61, 67, 71

Columbus Bd. ofEduc. v. Penick, 443 U.S. 449, 457 n.6(1979) ......................... 39

Cornish v. Richland Parish Sch. Bd., 495 F.2d 189, 191 (5th Cir. 1974) ........... 75

Daytona Bd. ofEduc. v. Brinkman, 433 U.S. 406, 410 (1977).............................. 34

Donnell v. United States, 682 F.2d 240, 247 (D.C. Cir. 1982),

cert, denied, 459 U.S. 1204(1983) ............................................................. 117

EEOC v. Strasburger, Price, Kelton, Martin & Unis,

626 F.2d 1272, 1273 (5th Cir. 1980) ........................... ............................. 116

Eisenburg v. Montgomery County Pub. Sch., 197 F.3d 123, 129 (4th Cir. 1999) . 82

Evans v. Harnett County Bd. ofEduc., 684 F.2d 304, 306 (4th Cir. 1982)........ .9 6

Exxon Corp. v. United States, 931 F.2d 874, 878 (Fed. Cir. 1991) ..................... 76

Farrar v. Hobby, 506 U.S. 103, 112 (1992)................................. 92, 120, 121, 122

Felder v. Harnett County Bd. ofEduc., 409 F.2d 1070, 1'074 (4th Cir. 1969) . . . 95

Freeman v. Pitts, 503 U.S. 467, 493-494 (1992) .......................................... passim

Full Hove v. Klutznick, 480 U.S. 149, 184 (1 9 8 0 ).......................................... 95, 102

Goldsboro City Bd. ofEduc. v. Wayne County Bd. ofEduc.,

745 F.2d 324, 327 (4th Cir. 1984) ................................................................. 39

Grove v. Mead Sch. Dist. No. 354, 753 F.2d 1528, 1535 (9th Cir.),

cert, denied, 474 U.S. 826(1985) ......................... .......................... 116, 117

Hasten v. Illinois State Bd. o f Election Comm V, 28 F.3d 1430, 1441

(7th Cir. 1993).............................................................................................. 116

Hathcockv. Navistar In t7 Transp, Corp., 55 F.3d 36, 39 (4th Cir. 1995)........ 132

Hayes v. North State Law Enforcement Officers Ass ’n, 10 F.3d 202, 212 (4th Cir.

1993) ...................................................... 35, 82, 88, 102, 105, 108, 109, 111

Henry v. Clarksdale Mun. Separate Sch. Dist., 433 F.2d 387, 388 n. 3

(5th Cir. 1971) ................................................................................................64

Higgins v. Bd o f Ed. o f Grand Rapids, 508 F.2d 779, 794 (6th Cir. 1974) ........ 55

Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U.S. 81, 100(1943)...................................... 107

Ho v. San Francisco Unified Sch. Dist., 147 F.3d 854, 856-865

(9th Cir. 1998) .......................................................................................... 37; 83

Hopwood v. State o f Texas, 78 F.3d 932 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 518 U.S. 1033

(1996) ..................................................................................................105, 125

International Salt Co. v. United States, 352 U.S. 392, 400 (1947) ..................... 96

Jacksonville Branch, NAACP v. Duval County Sch. Bd., 883 F,2d 945, 952 n.3

(11th Cir. 1989)........................................................................................ 38, 52

James B. Beam Distilling Co. v. Georgia, 501 U.S. 529, 542(1991)................... 74

Johnson v. Bd. ofEduc. o f City o f Chicago, 604 F.2d 504, 516-17

(7th Cir. 1979) ................................................................................................ 56

Johnson v. Capital City Lodge No. 74, 477 F.2d 601, 603 (4th Cir. 1 9 7 3 )___ .95

Jones v. Lockhart, 29 F.3d 422, 423-24 (7th Cir. 1994)

viii

122

Keyes v. Congress o f Hispanic Educators., 902 F. Supp, 1274

(D. Colo. 1 9 9 5 )....................................................................................... 37, 52

Klinger v. Nebraska Dept, o f Correction Servs., 909 F. Supp. 1329,1335

(D. Neb. 1995).............................................................................................. 121

Koger v. Reno, 98 F.3d 631, 637 (D.C. Cir. 1996)................................................ 69

Koopman v. Water Dist. No. 1, 41 F.3d 1417 (10th Cir. 1994) ......................... 121

Lee v. Anniston City Sch. Sys., 737 F.2d 952, 957, n.3 (11th Cir. 1984)............... 55

Lee v. Etowah County Bd. o fE d u c 963 F.2d 1416, 1422 (11th Cir. 1992)........ 11

Lee v. Talladega County Bd. ofEduc., 963 F.2d 1426, 1429 (11th Cir. 1992 . . . 34

Liddell v. State o f Missouri., 731 F.2d 1294, 1314 (8th Cir. 1984)....................... 55

Locke v. Mesa Petroleum Co., 479 U.S. 1031 ...................................................... 77

Lockett v. Bd. o f Ed. o f Muscogee County, 111 F.3d. at 842: . . . . 34, 38, 50, 75, 77

Lone Star Steakhouse & Saloon, Inc. v. Alpha o f Virginia, Inc.,

43 F.3d 922, 938 (4th Cir. 1995) ................................................................. 40

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145, 154 (1 9 6 5 ).................................... 95, 98

Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1, 11 (1967)...................................................... 94, 107

Lutheran Church - Missouri Synod v. FCC, 141 F3d. 344 (D.C. Cir. 1998) . . . 105

Martin v. CMS, 475 F.Supp. 1318

(W.D.N.C. 1979)............................... 4,10, 48, 66, 70, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80

Maryland Troopers Assn., Inc. v. Evans, 993 F.2d 1072, 1074-76

(4th Cir. 1993)............................ 4 ,35 ,82 ,87 ,88 ,89 ,95 , 109, 110, 111, 132

Maul v. Constan, 23 F.3d 143, 145 (7th Cir. 1994) ........................... ............ .. . 122

IX

94McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184, 191-192

Mesa Petroleum Co. v. Coniglio, 787 F.2d 1484, 1488 (11th Cir. 1986) ........... 76

Miller v. Johnson, 515 U.S. 900, 904 (1995) ........ 85, 94, 95, 103, 104, 106, 110

Miller v. Stoats, 706 F.2d 336, 340-42 (D.C. Cir. 1983) .................................... 117

Milliken v. Bradley, 481 U.S. 717, 740-741 (1 9 7 4 ).............................................. 48

Mills v. Freeman, 942 F. Supp. 1449, 1456 (N.D.Ga. 199 6 ).............................. 51

Milton v. Des Moines, Iowa, 47 F.3d 944, 946 (8th Cir. 1995) ......................... 122

Missouri v. Jenkins, 515 U.S. 70, 101-02(1996) ..................... ............................. 67

Mutual Fed. Sav. & Loan Ass ’n v. Richards & Assoc., 872 F.2d 88, 92

(4th Cir. 1989)........................................................................................ 41, 132

Northeastern Fla. Chapter, Associated Gen. Contractors o f Am. v. Jacksonville,

508 U.S. 656, 666(1993)............................................................ 114, 123, 124

Paradise v. United States, 480 U.S. 149, 166

(1986) ............................................................... 82,88,95,96,102,106,108

Parents Ass ’n o f Andrew Jackson High Sch. v. Ambach, 598 F.2d 705, 719-20

(2dCir. 1979) ................................................................................................ 56

Pasadena Bd. o f Ed. v. Spangler, 427 U.S. 424(1976)................. 35, 36, 67, 77,78

People Who Care v. Rockford Bd. ofEduc., 111 F.3d 528, 537

(7th Cir. 1997) ............................................................................. 36 ,62,67,96

Plessyv. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 533-544 (1896) ........................... 106

Podberesky v. Kirwan, 38 F.3d 147, 153 (4th Cir. 1994) ........ .. 49, 83, 89, 111

Reedv. Rhodes, 934 F. Supp. 1533 (N.D. Ohio 1996) 51

Regents o f the Univ. o f California v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265, 307 (1978) . . . . 78, 104

Riddick v. Sch. Bd. o f City o f Norfolk, 784 F.2d 521, 533 (4th Cir.),

cert, denied, 479 U.S. 938 (1986)................................................ 38, 39, 55, 63, 112

School Bd. o f Richmond v. Baliles, 829 F.2d 1308, 1311-1313

(4th Cir. 1987) .......................................................................................... 63,70

SEC v. United States Realty & Improvement Company,

310 U.S. 434, 459 (1940) ............................................................................ 116

Shaw v. Hunt, 154 F.3d 161, 164-68 (4th Cir. 1 9 9 8 )....................................passim

Singleton v. Jackson Mun. Separate Sch. Dist., 419 F.2d 1211(5* Cir. 1969) . . 61

Spencer v. General Elec. Co., 706 F. Supp. 1234, 1236-37 (E.D. Va. 1989),

a ff’d, 894 F.2d 651, 662 (4th Cir. 1990)............................................ 1 13, 126

Stillman v. Edmund Scientific Co., 522 F.2d 798, 800 (4th Cir. 1975) ............. 113

Stout v. Jefferson Co. Bd. ofEduc., 537 F.2d 800, 802 (5th Cir. 1976) ............... 56

Swann v. CMS, 243 F.Supp. 667 (1965)...................................................................6

Swann v. CMS, 300 F. Supp. 1358, 1372 (W.D.N.C. 1969)........... 6, 23, 26, 48, 63

Swann v, CMS, 306 F. Supp. 1299, 1312 (W.D.N.C. 1969)..................... 30, 63, 91

Swann v. CMS, 311 F.Supp. 265, 268-70 (1 9 7 0 )............................................ 30, 87

Swann v. CMS, 318 F.Supp. 786, 802-03 (1 9 7 0 ).................................................. 30

Swann v. CMS, 402 U.S. 1(1971) ................................................................... passim

Swann v. CMS, 379 F.Supp. 1102, 1103 (1974)................................................ 8, 31

Swann v. CMS, 67 F.R.D. 648, 649 (1975)........................................................ 9, 43

Swann v. CMS, 334 F. Supp. 623, 625 (1971) ...................................................... 63

xi

31Swann v. CMS, 401 U.S. 1, 23-25 (1971)................................................

Taxman v. Board ofEduc. o f the Township ofPiscataway, 91 F.3d 1547

(3rd Cir. 1996) cert, dismissed 522 U.S. 1010 (1997) .............. 42, 103, 105

Texas v. Lesage,____U.S.__ , 120 S.Ct. 467 (1999) ....................... 114, 115, 123

Tracy v. Board o f Regents o f the Univ. o f Georgia, 59 F. Supp.2d. 1314, 1322-

1323 (S.D. Ga. 1999) ................................................................................. 110

Tuttle v. Arlington County Sch. Bd., 195 F.3d 698, 703

(4th Cir. 1999)..................................................................... 41, 82, 89, 90, 101

United States v. Bd. ofEduc. o f St. Lucie County, 977 F. Supp. 1202

(S.D. Fla. 1997).............................................................................................. 52

United States v. City o f Yonkers & Yonkers Bd. ofEduc., 197 F.3d 41

(2d Cir. 1999) ............ .................................................................................. 70

United States v. Hunter, 459 F.2d 205, 220 (4th Cir. 1972) cert, den., 409 U.S. 934

(1972) ...................................................................... 99

United States v. Overton, 834 F.2d 1171 (5th Cir. 1987) ...................................... 35

United States v. United States Gypsum Co., 333 U.S. 364, 395(1948) ............... 38

United States v. Virginia, 518 U.S. 515, 547 (1996) ............................................ 98

United States v. Yonkers Bd.of Educ. 837 F.2d 1181, 1235-1238

(2nd Cir. 1 9 8 7 ).............................................................................................. 103

United States Fire Ins. Co. v. Allied Towing Corp., 966 F.2d 820, 824

(4th Cir. 1992)................................................................................................ 39

xii

Vaughns v. Bd ofEduc. o f Prince George’s County, 758 F.2d 983, 990

(4th Cir. 1985)................................................................... 38

Virginia Carolina Tools, Inc. v. International Tool Supply, Inc., 984 F.2d 113,

116 (4th Cir. 1993) ........................................................ .41

Vodrey v. Golden, 864 F.2d 28, 32 (4th Cir. 1988) ............................................ 132

Vulcan Tools o f Puerto Rico v. Makita USA, Inc., 23 F.3d 564, 566

(1st Cir. 1 994 )................................................................................................. 75

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229, 245(1976)..................... ............ .................. 65

Wessman v. Gittens, 160 F.3d 790, 792, 794, 800 (1st Cir. 1998) ................. 68, 83

Wilcox v. City o f Reno, 42 F.3d 550, 555 (9th Cir. 1994) ................................. 121

Wilder v. Bernstein, 965 F.2d 1196, 1204 (2d Cir. 1992) ......................... 116, 117

Williams v. United States Merit Sys. Protection Bd., 15 F.3d 46, 48

(4th Cir. 1994)................................................................................................. 41

Wilson v. Volkswagen o f America, Inc., 561 F.2d 494, 505-06 (4th Cir. 1977),

cert, denied, 434 U.S. 1020 (1978)........ .................................................... 132

Wolfe v. City o f Pittsburgh, 140 F.3d 236, 240 (3rd Cir. 1998)............................. 93

Wygant v. Jackson Bd. o f Ed., 476 U.S. 267, 273 (1986)...................................... 81

xiii

CONSTITUTION:

U. S. Constitution ...............................................................................................passim

STATUTES:

28U.S.C. § 1331 ......................................................................................................... 1

28U.S.C. § 1343 ......................................................................................................... 1

28U.S.C. §1291 ........................................................................................................... 1

42U.S.C. §1988 ............................................... ...................................... 41, 113, 115

42U.S.C. §1983 ....................................................................................................... 96

RULES:

Fed. R. Civ. P. 5 2 (a ) ......................... 39

Fed. R. Civ. P. 3 7 (d ).................................................................................................. 41

Fed. R. Civ. P. 33 ................................................................................................. 127

Fed. R. Civ. P. 37 .......................................................................................... 127, 132

Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(e)(1)......................... 127

Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(e)(2)..................................................................................127, 130

Fed. R. Civ. P. 37(a)(4)............................................................................................ 134

PUBLICATIONS

Friedrick A. Havek, The Constitution of Liberty. 160 (1960)

xiv

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

Jurisdiction in the District Court was pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §§ 1331 and

1343. Appellate jurisdiction over these consolidated appeals is pursuant to 28

U.S.C. §1291 etseq.

The District Court accorded Appellees prevailing party status for purposes

of an award of attorneys fees in the September 9 Order. The December 13 Order

merely calculated the amount of that award. Appellant Charlotte-Mecklenburg

County Board of Education [hereinafter CMS] has abandoned its appeal from the

Order of December 13, 1999, with respect to the amount of the fees and expenses

awarded Appellees Michael Grant, et al [Grant], since it did not contest those

findings in its opening brief. See CMS Brief at p. 38. Nor does CMS contest

Grant’s status as prevailing parties under the Order of September 9, should it be

affirmed by this Court.

1

ISSUES PRESENTED

I. Whether the material findings of fact upon which the District Court based

its determination that CMS had attained unitary status are clearly erroneous?

II. Whether the District Court correctly applied the legal principles governing

the determination of a school district’s unitary status?

III. Whether the award of nominal damages to each Appellee was supported by

the evidence?

IV. Whether the District Court abused its discretion in fashioning prospective

injunctive relief?

V. Whether the District Court abused its discretion in sanctioning CMS for

discovery abuses?

VI. Whether Capacchione-Grant are entitled to their respective awards of

attorneys fees and expenses of litigation made by the District Court?

2

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

The District Court’s Memorandum of Decision and Order of September 9,

19991 successfully culminates Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board o f

Education, a thirty-five-year-old desegregation case. The Order terminated an

injunction intended when entered to be a temporary remedy to bring CMS into

compliance with Brown’s objective of transforming segregated dual school

districts into unitary school systems that assign students to public schools on “a

non-racial basis.” Brown v. Board o f Education, 349 U.S. 294, 300-01 (1955).

Since the case was deactivated in 1975, the Swann plaintiffs [now referred

to as Belk] have closely collaborated with CMS in the operation of the school

system. See Capacchione, 57 F.Supp.2d at 232. (“CMS, the Defendant, is now

allied with the original class action plaintiffs.”) Neither CMS nor Belk desire a

declaration of unitary status, even though several CMS experts and its former

Superintendent effectively concluded the school system was unitary many years

before this litigation ensued.2 This collusion transmogrified a temporary remedial

1Capacchione v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board o f Education, 57 F.Supp. 2d

228 (W.D.N.C. 1999) [hereinafter referred to as Capacchione or the Order]

2See Schiller Report (PX1), Stolee Report (DX108 at p. 1-2); and testimony

of former Superintendent John Murphy (Transcript, 4/26 passim).

3

order into what this and other courts have long warned against — court ordered

remedies taking on a life of their own. See Maryland Troopers Assn. Inc. v.

Evans, 993 F.2d 1072, 1074-76 (4th Cir. 1993).

The Belk plaintiffs have not initiated a single complaint or objection with

the supervising Court during the last twenty five years.3 This, coupled with the

“remarkable”4 fact CMS objects to termination of the desegregation order, further

demonstrates the collusive nature of this case. Neither Belk nor CMS want the

Swann case to terminate. Both CMS and Belk aggressively employ the

desegregation order to pretextually perpetuate race-based student assignments for

non-remedial, i.e., racial diversity, purposes. Capacchione, 57 F.Supp. at 232. The

voluntary augmentation of the desegregation order with a magnet school program,

which employed strict racial quotas and required seats be “set aside” for black

students and remain empty rather than be assigned to non-black students, is strong

proof of that mindset.

The CMS collaboration with Belk was also manifest at trial. In unison,

3In 1980, the Swann plaintiffs assisted CMS in defending the case of Martin

v. CMS in order to perpetuate race-based student assignments. See infra

Argument, Section II G. Since 1975, Belk has never taken an adversarial position

to CMS.

4CMS brief at 13.

4

Belk and CMS “admitted” CMS had failed to comply with the desegregation

order; yet, Belk “agreed” with CMS that it did not need judicial supervision.

Belk’s cooperation with CMS in formulating litigation strategies has even

extended to the appellate process with Belk briefing the unitary status issues and

CMS briefing the injunction issue while simultaneously adopting each other’s

positions.

By declaring CMS unitary and enjoining it from continuing to employ racial

quotas, the District Court finally achieved Brown’s goal of admitting children to

public schools on “a non-racial basis.” Brown, 349 U.S. at 300-01. Belk and CMS

seek the opposite goal: they hope to defer a declaration of unitary status via this

appeal so a “controlled choice” student assignment plan, described by the District

Court as even “more race conscious...” than the remedial plan, can be

implemented. Capacchione, 57 F.Supp. 2d at 257. The tension between the two

competing goals provides the engine that drives this appeal.

5

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

1. Procedural History: Original Violations and Court-Ordered Remediation

Thirty-five years ago, several black parents initiated this action alleging that

CMS segregated its students and teachers by race. Swann's Motion to Restore the

Case to Active Docket, Exhibit 3 at 4. The Plaintiffs made no original allegations

that CMS maintained a system with discriminatory facilities, transportation,

extracurricular activities or educational opportunities. Id.

Over thirty years ago, former District Court Judge James B. McMillan

specifically found no racial discrimination as to “the use of federal funds; the use

of mobile classrooms: quality of school buildings and facilities: athletics . . .;

school fees; free lunches; books; elective courses nor in individual evaluation of

students.” Swann v. CMS, 300 F. Supp. 1358, 1372 (W.D.N.C. 1969).5 The 1970

desegregation decree was designed to eliminate the only vestiges of segregation

found to exist in the areas of student and faculty assignment., See Swann, 243 F.

Supp. 667 (1965); Swann, 300 F. Supp. 1358, 1372 (1969); Swann, 311 F.Supp.

5A11 Swann district court orders were entered against CMS in the Western

District (i.e., W.D.N.C.). Case citations to the various Swann orders will not

reiterate this reference.

6

265, 268-70 (1970); and Capacchione, 57 F. Supp.2d 228, 233-234.6 The 1970

order was the only desegregation decree ever issued in the Swann case. At its

heart was the simple directive that “no school [could] be operated with an all black

or predominantly black student body.” Id. at 268-70.7 CMS implemented the

decree and achieved complete desegregation of virtually all its schools for a

minimum of ten years. Capacchione, 57 F.Supp. 2d. at 246-249.

In 1971, the Supreme Court afforded the Swann case plenary review. See

Swann v. CMS, 402 U.S. 1,91 S.Ct. 1267 (1971). The Swann decision has

provided the following guide posts for district courts around the Nation engaged

in the supervision of dual public school systems:

1. With regard to racial balances or quotas, the limited use o f

mathematical ratios of white to black student is permissible “as a

starting point” but not as “an inflexible requirement. ” Id. at 22-25

(emphasis added).

2. The existence of “one-race, or virtually one-race, schools” does not

6The Order includes a succinct and accurate summary of the numerous

orders entered over the thirty-five year history of this case. Since neither CMS or

Belk has objected to the District Court’s chronicle of the procedural history of this

case, it should be adopted by this Court. Capacchione, 57 F. Supp. 2d at 232-238.

7In fashioning its desegregation order, the district court refused to adopt the

Swann plaintiffs plea for inclusion of precise racial quotas (like those unilaterally

implemented with the 1992 magnet school plan and held unconstitutional in this

case) “This court does not feel it has the power to make such a specific order.”

Swann, 300 F.Supp. at 1371. See Capacchione, 57 F.Supp. 2d at p. 230.

7

necessarily mean that desegregation has not been accomplished, but

such schools “in a district of mixed population” should receive close

scrutiny to determine that assignments are not part of state-enforced

segregation. Id. at 25-27.

3. The remedial altering of attendance zones, including the pairing and

grouping of noncontiguous zones, is not, as “an interim corrective

measure,” beyond the remedial powers of a district court. Id. at 27-29

(emphasis added).

4. The use of mandatory busing to implement a remedial decree is

permissible so long as “the time or distance of travel is [not] so great

as to either risk the health of the children or significantly impinge on

the educational process.” Id. at 29-31.

On July 30, 1974, the District Court approved several additional CMS

policies, presented as the CAG Plan. The Court characterized the Plan as

evidencing “a clean break with the essentially ‘reluctant’ attitude [of former

Boards of Education].” Swann, 379 F.Supp. 1102, 1103 (1974). “If implemented

according to their stated principles, they will produce a ‘unitary’ (whatever that is)

system.” Id.

These 1974 modifications included approval of three “optional” schools

which had no attendance zones. The District Court approved a flexible admissions

guideline for optional schools of “about or above” 20% black students to avoid

them becoming havens for white students seeking to avoid desegregation. Id. The

District Court never approved the use of strict racial quotas or segregated race-

8

based admissions lotteries for the optional schools.

On July 11, 1975, Judge McMillan placed the case on the inactive docket

with his “Swann Song” order. Swann, 67 F.R.D. 648, 649 (1975). The court noted

the Board's "positive attitude" and its open support of "affirmative action" as cause

for great confidence in the fact a declaration of unitary status was imminent. Id.

For the next twenty two years, the case remained inactive. CMS operated

autonomously, relying increasingly on strict racial quotas and the mandatory

busing of students to counteract the racial demographic change occurring within

the school system and throughout the entire county and maintained an

extraordinary level of racial balance in student assignment system wide.8

By 1992, the 1970 desegregation decree had developed into a permanent,

ever-accelerating racial quota system directed not at eliminating vestiges of

segregation but at combating demographic change. Given the continually

expanding role race played in student assignment to counteract Charlotte’s rapid

growth and the powerful demographic forces unleashed thereby, it was only a

The Report of Dr. David Armor, Capacchione-Grant’s principal expert,

details the exceptional levels of integration CMS achieved in its schools.

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit (PX) 137, Figures 1 and 2. This sustained racial balancing

achieved by CMS is further documented infra in Section IIA of this brief and in

Section IIB(l) of the Order. Capacchione, 57 F.Supp. 2d at 244-248.

9

matter of time before exasperated parents would challenge the constitutionality of

the dominant role race continued to play in the education of their children.9

2. CM S’ Historic Compliance with the Court Orders

For the last twenty-five years, CMS has "routinely reaffirmed its

commitment to integration, and the Court has never sanctioned CMS for violating

its desegregation orders.” Capacchione, 57 F. Supp.2d at 282. During this time,

the Belk Plaintiffs have never complained to the District Court that CMS violated

any aspect of the desegregation order, nor have they initiated a court challenge to a

school siting, student and faculty assignments or any other CMS policy or

practice. Id. at 239, 282. Indeed, Belk has never complained to the Court about

CMS compliance with the desegregation order except to urge it to maintain the

status quo when third parties challenged the continuing need for race based

busing.10

In April of 1999, the District Court commenced a two-month trial in which

it conducted an exhaustive review of CMS' compliance with its court ordered

student and faculty assignment obligations and the other factors deemed relevant

9The procedural history of this latest, and hopefully final, chapter in the

Swann litigation is detailed in the Order. Capacchione, 57 F.Supp. 2d at 239-40.

10 See, e.g., Martin v. CMS, 475 F.Supp. 1318 (W.D.N.C. 1979).

10

to unitary status under Green. Based upon largely uncontradicted evidence, the

Court found that since 1970 CMS was "highly desegregated for about twenty years

and 'well desegregated' for the remaining years." Capacchione, 57 F. Supp.2d at

248-249 (emphasis added).

On the central issue of student assignment, the District Court found the only

cause for any school’s racial imbalance was demographic change. Id. at 250.

Remarkably, during the very first decade of the desegregation process, "almost

every school was in compliance.” Id. at 249.11 In a report the Board commissioned

and adopted in 1992, an expert described CMS as having complied with the Court

Orders in good faith and desegregated all of its schools. (PX 11, p. 1-2).

Currently, over 70% of CMS' schools comply with the order’s racial balancing

goals; and, of those non-compliant schools, "a great deal" have been "borderline"

1 'In 1992, the Supreme Court approved a declaration of unitary status in student

assignment for the DeKalb County Schools despite the fact its schools had only one

year of compliance. Freeman v. Pitts, 503 U.S. 467, 493-494 (1992). ("this plan

accomplished its objective in the first year of operation, before dramatic demographic

changes altered residential patterns. For the entire seventeen year period,

Respondents raised no substantial objection to the basic student assignment system,

as the parties in the District Court concentrated on other mechanisms to eliminate the

dejure taint"). The Eleventh Circuit has found three years of compliance sufficient

to support a declaration of unitariness. Lee v. Etowah County Bd. o f Ed., 963 F.2d

1416, 1422(11th Cir. 1992).

11

compliant. Id}2 The District Court also found that, when compared to other urban

unitary school systems, CMS had "achieved a higher degree of racial balance . . . "

Id. at 248-249.

The District Court conducted a vestiges analysis of student assignment and

found that "[a]ll of the former de jure black schools still in operation have

maintained consistent levels of racial balance for at least twenty-two years . . ."

even though they are located in predominately black neighborhoods where the

density of black students has increased significantly over time. Id. at 253-254

(emphasis added). After at least twenty-two years of sustained system-wide racial

balance, only four formerly black schools under the dual system were found to

have become imbalanced and those few only after over 20 years of racial balance.

Id. at 254. The Court further found that twelve of the current schools that were

predominantly black for three or more years were all formerly white schools in the

I2The District Court's findings regarding CMS' high level of compliance is

actually understated. The Court's compliance analysis used the most restrictive

possible standard of desegregation, not the one actually required under the orders.

The desegregation order entered in 1980 only required CMS to avoid schools

having a black student population that exceeded the system wide black student

average population by 15%. The court never required any set minimum black

student population. However, the District Court’s review added a minimum black

student population standard equal to the system wide average black population

less 15%. The District Court acknowledged this +/- 15% of the system-wide

average was not required under the desegregation order. Id. at 246.

12

dual system. Id. at 254.

3. Demographic Change in Charlotte-Mecklenburg and CMS and the

Impact on Student Assignment

The demographics of CMS student population and of the Charlotte-

Mecklenburg area, from the entry of the desegregation decree in 1970 to present,

are carefully set forth in the Order, Id. at 236-239; 249-50.13 The Order details a

history of sweeping changes which neither CMS nor Belk dispute. This Court is

respectfully requested to adopt them.

The District Court described CMS as having "institutionalized" its

obligations under Swann to the extent that CMS repeatedly sought to counteract

residential racial demographic changes rather than isolate and eliminate any actual

vestiges of segregation. Id. at 249; 255.14 CMS began to experience racial

imbalances in its schools due to "the changing demographics of the county and the

,3The percentage of white students attending CMS schools has declined

from approximately 75% at the outset of the desegregation process to just over

50% today. This dramatic shift in the racial composition of the school system had

made the original edict of no majority black school unrealistic. This school district

will soon be a majority-minority system. See Clark Report (PX 138 at 4-5, Table

1); Capacchione, 57 F.Supp.2d at 237-238; Clark Testimony passim.

,4CMS went so far as to plan, fund and administer several housing

initiatives, believing it was constitutionally justified in delaying unitary status

while it tried to change housing patterns in Charlotte. Capacchione, 57 F.Supp 2d

at 283.

13

expanding geographic distribution of school age children___" Id. at 250. The

Court found that the rapid growth of previously undeveloped areas in the northern

and southern parts of the county, and the resulting change in residential

demographics played the "largest role" in causing racially imbalanced schools. Id.

Specifically, the District Court found that the so-called "inner city" had a

"still more concentrated" black student population today than in 1970. Id. at 237.

In the "donut-like middle suburban" communities, surrounding the inner city,

residential demographics changed from "almost all white in 1970 . . . to

predominately black . . . " today. Id. Almost all presently racially imbalanced

black schools are located in these two predominantly black residential areas.

These areas have "lost large numbers of white residents since the 1970's". Id. The

District Court noted that the "outer area" which extends in a ring around the

middle suburban and inner city areas has experienced the highest level of

population growth in the county. Id. Moreover, the "outer area" is between 75% -

95% white. Id. at 254-255.

These changes meant that the middle suburban area, which once supplied

reasonably proximate populations of white students for satellite zones or pairing

relationships to racially balance the black inner city schools, were now

predominantly black. Thus, the distances between black inner city areas and white

14

suburban areas grew while the density of black inner city and middle suburban

black populations increased. Consequently, proximately located white student

populations were unavailable to racially balance black inner and middle suburban

schools, given rush hour traffic problems that created unduly burdensome bus

rides.

Based on these findings of demographic change, the District Court

concluded "there can be no doubt that demography and geography played the

largest role in causing imbalance." Id. at 250 (emphasis added). These findings

were not seriously challenged by either CMS' or the Belk Plaintiffs' demographers.

The court’s findings are corroborated by at least four major CMS studies.

In 1988, Assistant Superintendent Dr. Bruce Irons found CMS was experiencing

increases in the number of racially imbalanced schools due primarily to

demographic changes in the racial composition of attendance zones (Plaintiff-

Intervenors' Index of Relevant Testimony and Documentary Evidence [Index], p.

119).

A second study in 1992 by Assistant Superintendent Jeffrey Schiller and

staff member Chuck Delaney documented how dramatic demographic changes

within the attendance zones of certain schools caused racial imbalances. A third

study conducted in 1994 by Schiller reiterated that CMS' schools were becoming

15

increasingly racially imbalanced due to demographic changes "in attendance

zones" that were cumulatively inhibiting CMS' ability to racially balance its

schools. Id. at 121. Dr. John Tidwell conducted a fourth study corroborating the

previous studies and concluding that demographic change was "too powerful for

CMS to conquer with student assignment policies alone." Id. at p. 122 (emphasis

added).

Schiller's 1994 report is especially authoritative and compelling. This study

demonstrated how sustained levels of demographic change in attendance zones of

formerly balanced schools resulted in the schools becoming racially imbalanced.

Schiller analyzed several predominately white neighborhoods with racially

balanced schools in 1987-88 that experienced significant losses of white residents

and reciprocal increases in black residents resulting in racially imbalanced schools

during the 1992-93 school year. (PX 8, Appendix H). Schiller's report concluded:

• Racial residential demographic changes were the "primary cause" of

racially imbalanced schools, in part, because "the inner city . . . became

'blacker'. . ." and the outer suburbs "became whiter."

• No evidence indicated "CMS policies or practices are responsible . .

." for increasing levels of school segregation; and

• The "continuing and cumulative effect of demographic shifts . . . "

inhibited CMS' ability to maintain desegregated schools (PX 1).

CMS has admitted that demographic change was causing the very imbalance

16

it now seeks to use as a way to forestall its own unitary status. In a 1993 letter to

the United States Department of Education [DOE], CMS legal counsel represented

that the magnet school program was implemented "[b]ecause . . . of demographic

and residential patterns in the community [which] have made it extremely difficult

to continue . . . . the Court approved desegregation techniques which had

been rendered increasingly ineffective by demographic change.” (PX 4, p. 3,

emphasis added). In 1994, present CMS counsel of record cited this same rationale

for maintaining the magnet school program. (Id., letter from James G.

Middlebrooks).

The Court specifically found that CMS did not attempt to bring about any

resegregative residential demographic change. Capacchione, 57 F.Supp.2d at 250.

CMS repeatedly sought to counteract the effects of demographic changes by

undertaking disruptive, destabilizing student reassignments in the late 1980!s and

early 1990's. Capacchione, 57 F.Supp.2d at 238. Such racial balancing proved to

be an increasingly impossible task because the area in the county with the highest

density of black students was becoming increasingly black while predominantly

white suburban areas became whiter still. The residential areas in between the

inner city and the outlying suburbs also became increasingly black and widened

the distances between the highest concentrations of black students and

17

communities predominantly composed of white students. CMS adopted the

magnet school program specifically to counteract demographic changes in

attendance zones that were causing schools to fall out of racial balance.

4. Demographic Change, School Siting and CMS Compliance

CMS' school siting practices were found to be compliant with the Court's

Orders since 1980. Judge McMillan had urged CMS to avoid siting schools based

upon "population growth trends alone . . . " and directed CMS to consider "the

influences . . . of new building . . . " on simplifying integration. Swann, 57 F.

Supp. 2d at 251 (emphasis added). The court did not prohibit CMS from building

schools to address growth needs in any part of the county so long as other factors

were also considered. Obviously, no constitutional court order could prohibit CMS

from being responsive to demographic changes and public demand for services at

a level that could not have been foreseen in the 1970's.

The District Court analyzed the last twenty years of CMS' school siting

practices and concluded it had not followed "an intentional or neglectful pattern of

discrimination." Id. at 251-52. The Court found CMS had "not based its school

planning on growth trends alone-----Rather, it routinely considered] racial

diversity in school siting decisions," and "a host of other important criteria, such

as finances, site availability, site size, traffic patterns, transportation burdens, and

18

utilization." Id. As a result, CMS had maintained a "well desegregated" school

system for nearly 30 years.

The District Court further found CMS built schools to reasonably serve both

black and non-black students. The majority of CMS* schools built since 1980 have

had racially balanced student bodies every year since they were opened. Id. at

252, n. 26. CMS did not engage in a practice of closing racially mixed schools

while building schools in predominately white areas. Rather, the District Court

described CMS' school sitings in its outer areas as a "pressing necessity" due to

massive increases in suburban residential populations causing overcrowding. Id.

at 252.

The District Court found that "[t]he majority of new schools built since

1980 ~ fifteen out of twenty-seven - have had racially balanced student bodies

every year since they have been opened." Id. at 252, n. 26. Since 1980, most

newly built schools have been sited in the fastest growing areas of the county. The

Court held this was partly "a consequence of racial balancing requirements"

produced by the practical impossibility of assigning white students to any schools

built in the inner city without untenably long bus rides. Id. at 252-253. The Court

found that "[bjuilding schools in the inner city would have exacerbated this racial

balancing dilemma." Id.

19

High levels of integration were achieved and sustained by CMS despite an

array of practical l imitations on school siting such as the unavailability of suitably

affordable large tracts of land -- minimum 50 acres for high schools — in densely

populated, predominately black mixed use inner city areas, or in areas between

predominately black and white neighborhoods.

5. Compliance with the Faculty Balance Requirements

The desegregation order never established specific numerical targets for

racially balancing the various schools faculties. Id. at 259. The District Court

found CMS' faculty was 90 percent compliant with the Court's Orders "during the

school years with the 'worst' racial imbalance." Id. at 259-260. The trial court

further found that since 1977, "seventy-five percent to ninety percent of the

district's schools have racially balanced faculties" even when schools not subject

to the prior orders were counted. Id. This high level of compliance was achieved

despite changing residential racial demographics, strong teacher preference to

work in a school close to their home and an "especially pronounced" black teacher

shortage. Id. at 259.

6. Roughly Equal Transportation Burdens

The District Court examined the comparative transportation burdens giving

due consideration to Judge McMillan's acknowledgment that "absolute equality"

20

regarding the desegregation transportation burden was not required, and his

explicit finding that the transportation burdens for black children were not

unconstitutional due to the practical limitations on achieving more equal travel

burdens while still racially balancing all schools. Id. at 253.

From 1974 through 1992, the busing of black and white students was

substantially equal. (Plaintiffs' Index, f 154, p, 65). When CMS voluntarily

implemented the magnet school plan, the District Court determined that "a greater

proportion of white students . . were voluntarily bused for desegregation

purposes "on generally . . . much longer bus rides". Capacchione, 57 F.Supp.2d

at 252-53. That is because CMS located its highly attractive magnet schools

almost entirely in the inner city in order to draw non-black students in from the

suburbs. Id. Black students wishing to attend magnet schools can choose a school

located in predominantly black inner city neighborhoods and avoid any significant

transportation burden.

The comparative busing burden is complicated by the racial demographics

of the county's residential neighborhoods. The Court found that if white students

in outer suburban neighborhoods were involuntarily assigned to inner city schools,

it would have required intolerable trip times due to "rush hour traffic." Id.

(Testimony of Sharon Bynum, April 22, 1999, p. 14.) The District Court

21

concluded, "[gjiven the realities of the situation . . . the current situation may be

about the best CMS can do while adhering to racial balance guidelines." Id. at

253.

7. Demographic Change, Magnet School Transfers and Compliance

Importantly, the District Court found the CMS' magnet school program "had

an overall effect of countering resegregative trends . . . " resulting in fewer blacks

attending segregated schools than if the magnet school program had not been

adopted. Id. at 249-250, n.23. The court further found that student transfers into

magnet school were monitored by CMS to ensure that they had an overall

integrative effect on the school system. Id.

In 1993, CMS conducted a study designed in part to monitor the effect of

magnet transfers on the desegregation plan. That study analyzed magnet transfer

patterns, and concluded there was "no evidence of a negative systematic impact on

the racial balance of the non-magnet schools." Remarkably, yet consistently,

Belk’s expert witness, Dr. Leonard Stevens, testified that magnet school transfers

never caused a school he analyzed to fall out of compliance with any court order.

(Stevens testimony, pp. 182-183). Dr. Stevens conceded that if the inner city

schools were not converted to magnet schools, "it is quite possible that these

schools would have remained out of compliance. . . . " Finally, this Belk expert

22

concluded there was no evidence that any CMS school failed to achieve its racial

balance goals because of transfers to magnet schools. Actually, the magnet schools

had an overall integrative effect on CMS. Capacchione. 57 F.Supp.2d at 250, n.23.

Non-magnet transfers were also fastidiously monitored. Actually, CMS’

Board so carefully watched its non-magnet transfers that children were routinely

denied transfers despite their hardships solely to preserve precise racial balancing.

(Testimony of Lindalyn Kakadelis, p. 46-52). One Board member described this

process as disturbing. Id. at 46.

8. Facilities

The District Court found CMS' facilities were not maintained or allocated

discriminatorily. In 1969 and again in 1971, Judge McMillan found that CMS

never maintained racially discriminatory facilities. See Swann, 300 F. Supp. at

1366; Swann, 306 F. Supp. 1291, 1298 (1969); Swann, 334 F. Supp. 623, 625

(1971). The Court thus concluded "that there were no vestiges of discrimination

in facilities at the initial stages of the Swann case and again at the close of the case

in 1975.” Capacchione, 57 F. Supp.2d at 262.

Both the testimony of CMS' facilities expert, Dr. Dwayne Gardner, and the

CMS' Assistant Superintendent responsible for facilities, Jeffrey Booker,

23

demonstrated that CMS maintained its facilities without racial discrimination.15

The District Court found Dr. Gardner’s report, while suffering from serious

methodology problems, demonstrated "no disparities [in facilities] along racial

lines." Id. at 264.

The two lowest rated schools in the district were so inadequate they needed

to be replaced. Yet, "both [were] majority white schools in predominately white

neighborhoods . . . Id. at 264-65. By contrast, the second highest rated school

was predominately black and located in a black neighborhood. Id. at 265.

Eighteen racially identifiable white or racially balanced schools fell into Dr.

Gardner’s second lowest, "needs major improvement," rating category. Id. Sixteen

predominately black schools were given that rating. Id. Even using a flawed and

result-oriented methodology of evaluating only a portion of predominately white

or balanced schools while evaluating all predominantly black schools, the greatest

number of schools falling in the "needs major improvements" category of the

report were still either predominately white or racially balanced.

The Court concluded that more white and racially balanced schools were

"likely to [be].. . needing major improvement". Dr. Gardner's report demonstrated

15The schools evaluated by Dr. Gardner were selected by CMS. At least 50

needy, racially balanced schools were excluded by CMS from his analysis.

(Plaintiffs’ Index, pp. 57-61).

24

"that CMS' facilities' needs are spread across the system without regard to the

racial composition of its schools." Id. Dr. Gardner actually testified that he could

not trace any disparities to the dual system. Id.

Booker wrote a memorandum in August 1997, identifying those schools

"having impediments that inhibit the delivery of instructional services." He

identified three times as many racially balanced or racially identifiable white

schools with facilities inhibiting the delivery of the instructional program. See

Plaintiffs' Index, p. 61. Based upon Booker’s testimony, the Court found 108 out

of 135 schools were "in need of renovations and most of these needy schools — 80

out of 108 or roughly 75 percent of them -- have racially balanced populations."

Id. at 265. Like Gardner, Booker testified he could not trace any inequities to the

dual system.

The Court found CMS had spent over $500,000,000 renovating older

facilities, many of which were in the inner city. CMS' own surveys showed black

parents were satisfied — in some cases more so that white parents - with the

facilities their children attended. Capacchione, 52 F. Supp.2d at 264, n. 33.

Despite these enormous expenditures, older facilities tend to be comparably

inadequate regardless of the racial composition of their student body because, as

Dr. Gardner testified, they were built to satisfy the needs of entirely different

25

educational programs than those used today. (Plaintiffs' Index, ^ 135, pp. 56-57).

These schools are not inadequate because of the race of the students who attend

them, rather, their inadequacies stem entirely from their age and the limited

financial resources of CMS. Capacchione, 57 F.Supp.2d at 266.

9. Resources

In 1969, the District Court determined CMS had not discriminated

regarding library books, elective courses, the availability of and assignment to

advanced classes and other educational resources. Swann, 300 F. Supp. at 1366-

1367. See Swann, 306 F. Supp. 1291, 1298 (1969) Thirty years later, these

findings were repeated by the District Court without an intervening complaint to

the contrary from thesBelk Plaintiffs. Capacchione, 57 F. Supp.2d at 261-262

(1999). (“no vestiges of discrimination in . . . resources at the initial stages of the

Swann case. . . .”).

The finding that CMS did not discriminate in allocating its educational

resources was based largely upon the unrebutted testimony of two CMS assistant

superintendents. Both testified CMS allocated funds to schools "on a per pupil

basis" which means all schools received resources based on the number of

students, not race. The District Court found this practice safeguarded against

discrimination and ensured equality in the allocation of resources. Id. at 266.

26

The Court also found much of the evidence of inequitably allocated

resources was unreliably "anecdotal" which rendered the allegations of inequality

"inconclusive." Id. at 265. Morever, much of the anecdotal evidence demonstrated

that racially identifiable white schools faced greater resource needs than racially

identifiable black schools. Id. at 263-64.

Former Assistant Superintendent Dan Saltrick conducted a study that found

each school in CMS implemented the "same core curriculum . . . " and found "no

differences in the allocations for instructional staff, materials or text books . . . [in]

any [CMS] school." (PX 29). Additional resources were routinely allocated to

predominately black schools that were not made available to white or racially

balanced schools (Index, pp. 67-71). In fact, black students in predominantly black

schools had more favorable student-teacher ratios than white imbalanced schools.

{Id. at 71). When Mr. Saltrick was asked if black students were denied equal

educational resources, he testified, "no." Id. at p. 74. Instead, he testified the

opposite was true in many cases.

Finally, the Court found that if any racial disparities in resources did exist,

they were caused by private factors such as PTA, parent and corporate

sponsorships and contributions which were isolated and outside of CMS' control .

Id. at 266, n. 27. The District Court correctly concluded Capacchione-Grant

27

proved the absence of racially discriminatory intent and causation as to any

alleged resource disparities.

10. CMS' Magnet Schools and Rigid Racial Quotas

While CMS' level of compl iance with the Court's desegregation order on

student assignment was found to be very high, the District Court concluded "CMS

went too far in trying to achieve racial balance in its magnet schools by imposing a

selfprescribed quota that was too inflexible." Id. at 282, n. 45 (emphasis added).

These racial quotas were imposed on CMS' students through a racially segregated

magnet school dual lottery system and strict seat “set asides” based on race.

a. The magnet schools were a voluntary desegregation plan

implemented to counteract demographic change

In 1992, CMS voluntarily implemented its "greatest change in student

assignment policy by adopting a student assignment plan that emphasized the use

of magnet schools. Id. at 239. This change was inaugurated by a 1992 report

prepared by Dr. Michael Stolee, a CMS retained expert in student assignment. The

report specifically found that, over the prior twenty years, CMS had "in good faith,

complied with the Orders of the Court . . . " and that "all public schools in the

system have been desegregated." (PX 11) (emphasis added). Despite these

findings, Dr. Stolee recommended that CMS adopt a magnet school program,

28

cautioning that CMS should obtain court approval prior to doing so,16

Ignoring these findings and warnings, CMS initiated the magnet school

program as a “self-prescribed...” voluntary desegregation plan. Id. at 282, n. 45.

The magnet school program was not designed to eliminate vestiges of the dual

school system; Dr. Stolee determined none existed in student assignment. Rather,

the plan was designed to correct racial imbalance caused by demographic changes.

(PX 4).

The sweeping demographic changes that motivated CMS to adopt its

magnet school program were noted as early as 1988 in the report of Dr. Irons. He

correctly concluded that the cause of schools falling out of racial balance was

demographic change. In his report, Dr. Irons predicted residential racial

demographic change would most strongly affect CMS' ability to maintain racially

balanced schools. (PX 3).

Dr. John Murphy, the former CMS superintendent who devised and

implemented the magnet school program, also admitted that CMS adopted the

magnet school plan to racially balance schools that were imbalanced due to

16Contrary to its own consultant's warnings that CMS should obtain prior

court authorization, CMS implemented the magnet school plan without court

approval or supervision.

29

residential racial demographic shifts. (Murphy testimony, pp. 33, 46). He also

conceded the desegregation order was used by CMS as a shield to facilitate

attainment of racial balancing goals (Id. at pp. 31-33). This was no secret. CMS

openly acknowledged to the Department of Education that its magnet school plan

was implemented "[bjecause . . . of demographic and residential patterns___"

(PX4).

b. The magnet schools* rigid racial admission quotas

The plan clearly violated prior Swann orders because CMS implemented the

racially segregated lotteries which used strict racial quotas to populate the magnet

schools. The District Court noted that Judge McMillan "firmly rejected the use of

rigid racial quotas . . . " quoting him as admonishing CMS that "fixed ratios o f

pupils in particular schools will not be set" and requiring flexibility in its effort to

achieve racial balance. Id. at 286; quoting Swann, 306 F. Supp. at 1312 (emphasis

added); Swann, 311 F. Supp. at 268; See also Swann, 318 F. Supp. at 792

(approving schools with only three percent black population, stating "this is not

racial balancing but racial diversity. The purpose is not some fictitious 'mix,' but

the compliance of this school system with the Constitution") The Court

specifically stated that "racial balance is not required by this Court" but rather

permitted "wide variations in permissible school populations . . . . " Swann, 318 F.

30

Supp. at 792. The Supreme Court in Swann also held that racial balancing was

forbidden under the desegregation order. Swann v. CMS, 401 U.S. 1, 23-25

(1971). The District Court therefore did not impose "an inflexible requirement,"

but approved only "the very limited use ...of mathematical ratios." Id. at 25

(emphasis added).

The three optional schools approved in 1974 did not use rigid racial quotas.

Swann, 379 F. Supp. at 1104. Unlike the admission process for optional schools,

CMS used racially segregated lotteries to admit students to magnet schools. Id. at

287. (CMS used a "black lottery and a non-black lottery until the precise racial

balance is achieved.") CMS set a sixty percent non-black and forty percent black

racial quota for each school. The District Court found that "[i]n policy and in

practice, the magnet schools 60/40 ratio requirement is an inflexible quota." Id. at

288. 17

CMS' policy also required that magnet school seats were reserved in such a

way that "slots reserved for one race will not be filled by students of another race."

Id. For example, if after the black lottery was concluded two black seats

17In the case of Christina Capacchione's 1996 application for the 1996-1997

school year, all black applicants were admitted to the Olde Providence school

while over 100 non-blacks were wait listed. Capacchione, 57 F. Supp.2d at 288.

Accordingly, the odds of a non-black student being admitted to a magnet school

were enormously smaller than those of a black student.

31

remained open, CMS would not allow non-black students to immediately fill them

even though the school in question was well within the Court's racial balance

guidelines. Id. Instead, CMS actively recruited for the remainder of the spring

and into the summer to find two more black students to fill those seats. Id.

Furthermore, while blacks were recognized as one racial category, all other races

were simply lumped together as "non-blacks."

The District Court found the magnet schools offered "specialized curricula"

while optional schools did not. Id. at 286, n. 49. Also, while the optional schools

"guaranteed admission into schools of equal quality;" the magnet school program

had no such guarantee. Id.

In many magnet schools, the District Court found it "was not uncommon for

the school year to begin with seats remaining vacant because students of one race

would disrupt the desired racial balance." Id. Based upon this evidence, the Court

concluded CMS, in direct contravention of Judge McMillan's Orders, employed

"inflexible" quotas "using mathematical ratios not as a starting point but as an

ending point." Id. at 289-290.

The District Court then found the rigid racial quotas were unnecessary

because they were not required by the desegregation orders, but rather, forbidden

by those orders and unnecessary in the later years of the desegregation order. Id.

32

The inflexibility of the quotas was such that the Court stated it would be "hard

pressed to find a more restrictive means of using race" Id. The quotas were also

found to be indefinite in duration. Id. at 290. Ultimately, the Court deemed the

quotas as lacking any "reasonable basis" and amounted to CMS' ‘“ standing in the

schoolhouse door’ and turning students away from its magnet programs based on

race .. ."!8 which was incompatible with Brown’s goal of achieving "a system of

determining admissions to the public schools on a non-racial basis." Brown v.

Board o f Education, 349 U.S. 294, 300-301 (1955).

The District Court concluded the CMS' magnet lottery denied CMS students

"equal footing" in obtaining an enhanced educational opportunity and that "this

denial of equal footing occurred even where seats were available and where racial

balancing goals under the desegregation Order would not be affected."

Capacchione, 57 F.Supp. 2d at 289.

Having found that CMS denied students "equal footing" based upon race

through its magnet school lottery, the District Court correctly enjoined the precise

practice it found unconstitutional, directing CMS to refrain student assignment

practices designed "to deny students an equal footing based on race."

Capacchione, 57 F. Supp.2d at 294. The Court declared CMS unitary in all

18Capacchione, 57 F.Supp.2d at 290.

33

respects, and awarded the Plaintiff Intervenors nominal damages, attorneys' fees,

expert fees, and costs. Id.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The increasingly uniform and authoritative rulings of federal courts limit the

role of a supervising court in a desegregation case to elimination of the dual

system of segregated education and their vestiges with a return of control to local

authorities at the earliest opportunity. See Freeman v. Pitts, 503 U.S. 467, 490

(1992); see also Daytona Bd. ofEduc. v. Brinkman, 433 U.S. 406, 410 (1977). A

desegregation decree is not intended to be permanent. Dowell, 488 U.S. at 247-48.

“ A [n]ecessary concern for the important values of local control of public school

systems dictates that a federal court’s [supervision] . . . does not extend beyond the

time required to remedy the effects of past intentional discrimination.” Id. “Rather,