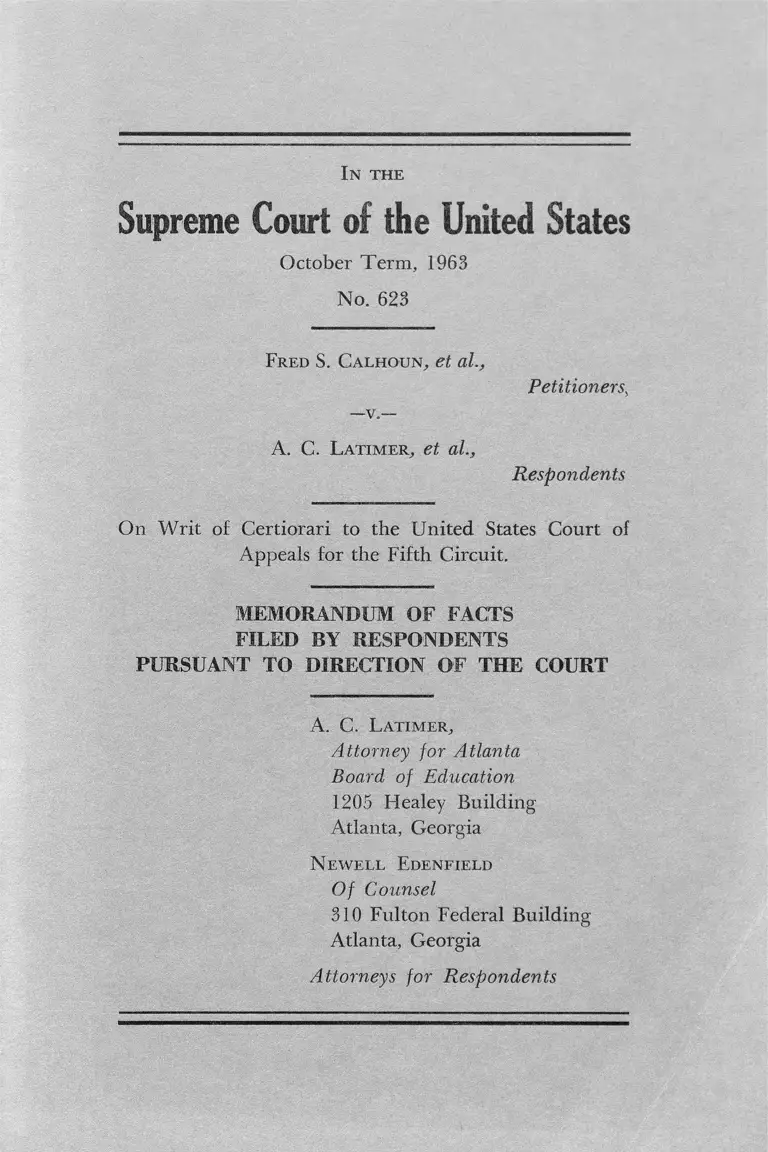

Calhoun v. Latimer Memorandum of Facts Filed by Respondents Pursuant to Direction of the Court

Public Court Documents

April 8, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Calhoun v. Latimer Memorandum of Facts Filed by Respondents Pursuant to Direction of the Court, 1964. 85382288-ac9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1c302e56-5715-41c8-8361-d3418114ff2e/calhoun-v-latimer-memorandum-of-facts-filed-by-respondents-pursuant-to-direction-of-the-court. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1963

No. 623

In th e

Fred S. C alhoun , et ah,

Petitioners,

A. C. L atim er , et al.,

Respondents

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit.

MEMORANDUM OF FACTS

FILED BY RESPONDENTS

PURSUANT TO DIRECTION OF THE COURT

A. C. L atim er ,

Attorney for Atlanta

Board of Education

1205 Healey Building

Atlanta, Georgia

N ew ell Edenfield

Of Counsel

310 Fulton Federal Building

Atlanta, Georgia

Attorneys for Respondents

INDEX

Page

IN TRO DU CTION ______________________________ 1

QUESTIONS ANSWERED_______________ 3

Formal action of School Board on freedom of

choice and proximity as assignment and

transfer criteria. ......... 3

Notice to Negro community as to mechanics of

assignment and transfer.______________________ 4

A solution to overcrowding. ____________________ 5

Present administrative problems. _______________ 5

Start toward desegregation in 1961 rather than

in 1954______________ 6

Zone lines vel non. ________ 7

RESOLUTION OF TH E A T LA N TA BOARD

OF EDUCATION______________________________ 8

AFFIDAVIT OF THE ATLA N TA

SUPERINTENDENT OF SCHOOLS. _________ 12

I n the

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1963

No. 623

Fred S. C alhoun , et al.,

Petitioners,

A. C. L atim er , et al.,

Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit.

MEMORANDUM OF FACTS

FILED BY RESPONDENTS

PURSUANT TO DIRECTION OF THE COURT

INTRODUCTION.

The confusion and apparent conflict between the

record and the oral argument in this case came about by

reason of the fact that the case was argued on a record

which was then two years old. In the intervening period

the actual situation in Atlanta, as respects both policies

and practices, had drastically changed, particularly as a

result of the decision of the Circuit Court and its im

plementation by the Atlanta School Board. These changes

which did not appear in the record then came out in

1

2

argument and in response to questions from the Court.

Hence the confusion. If this circumstance has incon

venienced the Court or embarrassed opposing counsel,

we respectfully ask the forgiveness of both. If we have

departed from the record, it was unavoidable. The rea

sons for this were pointed out in our brief in opposition.

There we said (p. 9) :

“ The most important changes in the plan, how

ever, are those that have taken place as a result of

the opinion of Judge Bell, or are planned for

September, 1964. These are not in the record, of

course. We are dealing with a record made in the

first days of desegregation, yet the Court is asked to

assess the degree of progress toward a goal made

over a period of time. We do not see how that can

fairly be done unless we, as attorneys and spokes

men for the school board, may make reference to

things that have occurred after the making of the

formal record.”

In short, what we were attempting to do was to argue

the case not on the basis of what the Atlanta situation

was but what it is, based on changes which we conceived

to be implicit in the lower court’s opinion.

For the convenience of the Court we have arranged

the material in this response in question and answer

form, the questions being intended in each case to sum

marize those asked by the Court. The answers in each

case show the record reference or the authority on which

they are based. In order that there be no question as to

the present policies of the Atlanta school authorities, we

also include a confirming resolution of the Atlanta Board

3

of Education and an affidavit from the Superintendent

of Schools.

QUESTIONS ANSWERED.

QUESTION (by Chief Justice Warren)

Where in the record or in the briefs does it appear

that the Atlanta Board of Education has by formal action

adopted a present policy of making initial assignments

or granting transfers on the basis of freedom of choice

or proximity?

ANSWER:

At the time of oral argument there had been no such

formal resolution. This was admitted in response to a

direct question by the Chief Justice. It had been publicly

stated, however, that under the decision of the Circuit

Court the only criteria left in the Atlanta plan were free

dom of choice, availability of facilities, proximity to

schools, and grade-a-year. (See Affidavit of Superin

tendent Letson, infra, p. I ! ) That such was the situa

tion was also indicated in the briefs. (See Brief for

Respondents, pp. 14-15; see Brief for State of Georgia

as Amicus Curiae, p. 9.) Availability of facilities as a

criterion was recited in the preamble to the original

Atlanta plan (R. 11). Availability of facilities is one of

the “other relevant matters” (R. 12) which per force

are a part of any school assignment and transfer plan.

Choice was one of the criteria contained in the original

plan (R. 13). All transfers heretofore granted under the

Atlanta plan were based upon choice. (Affidavit of Su

perintendent Letson, infra, p. If-.) Choice was not one

of the criteria which were abandoned. (Brief in Opposi

tion, pp. 8-9.) Proximity was not one of the criteria ex

pressly mentioned in the original plan but was recognized

4

by the District Court, by the respondents, and by peti

tioners to be a relevant consideration in the assignment

and transfer of pupils (R. 212). Atlanta has now adopted

a formal policy of applying these criteria in connection

with assignments and transfers. (See Resolution of the

Atlanta Board of Education, infra, pp. §-J|.)

QUESTION (by Chief Justice Warren) :

Has the Negro community been apprised of the me

chanics to be followed in applying for initial assignments

to the eighth grade and for transfers in the higher grades?

ANSWER:

This question was asked in a context which leads us

to believe that what the Chief Justice wanted to know

was whether or not the Negro community had been ad

vised as to the plans of the school board relating to as

signments and transfers in September, 1964. In response

we can only say that there had been a public announce

ment following the decision of the Circuit Court as to

what was left of the Atlanta plan. (See affidavit of Su

perintendent Letson, infra, p. IS.) The decision of the

Circuit Court was widely publicized and was construed

by the school board as eliminating all criteria except

freedom of choice, availability of facilities, and proximity

of schools. (See Affidavit of Superintendent Letson, infra,

p. 13.) These were the same criteria urged before the

Court on oral argument. For each of the previous years

the Negro community had been apprised of how to take

advantage of the transfer privilege (R. 63-65, 71) . The

procedure was printed and made available to the public.

(R. 64) . In previous years the official action of the Board

of Education was made public (R. 64), it was discussed

5

between the Superintendent and school principals (R.

64-65, 71), and teachers (R. 65), and was discussed over

the educational television system (R. 65). It was given

wide publicity by newspapers, radio and television (R.

64). It was discussed at Parent-Teacher Association

meetings (R. 71). The Superintendent was of the opinion

that there was no lack of understanding as to how to

apply for transfers (R. 63-64, 71).

QUESTION (by Chief Justice Warren) :

When and how will Atlanta solve the present situation

with respect to overcrowding whereby some schools are

crowded to several times their capacity while others are

only half full?

ANSWER:

The respondents freely admit the existence of this

situation and concede that the Negro school population

suffers more as a result than do the whites, although there

is overcrowding with respect to both (R. 105). Over

crowding, however, is not so much a racial problem as

a population problem. The enrollment in Atlanta

schools has been constantly increasing (R. 101) . This

increase has consisted almost entirely of Negro children

(R. 101, 105) . No plan of desegregation, however com

prehensive or however fairly administered, can com

pletely solve the problem of overcrowding. Admittedly,

desegregation will help and is helping this situation, but

the ultimate solution can lie only in additional con

struction. JJ-

QUESTION (by Mr. Justice Stewart) :

Does Atlanta presently have any administrative prob

6

lems which would militate against a more speedy transi

tion toward complete desegregation?

ANSWER.

Since this question is addressed to the situation pres

ently existing, it of course can only be answered by going

outside the record. The administrative problems which

lead to a staggered plan of desegregation were recited in

the preamble to the original plan (R. 10-12) . Since the

existence of these problems was not controverted, the

District Court took them as true (R. 19). With respect

to the present situation, we can only say that the same

problems, including the size of the school system, rapid

growth of the community, and shifting populations, con

tinue to exist.

QUESTION (by Mr. Justice Goldberg) :

Why did Atlanta not voluntarily start toward desegre

gation in 1954, and should it be rewarded because it

waited to make a start until after a court order which be

came effective in 1961?

ANSWER:

The answer to these questions must necessarily be

more practical than legal. The resistance of the Georgia

Legislature, which threatened to cut off funds, the danger

of schools being closed, and the successful efforts of the

Atlanta community to overcome these obstacles have

been stated and reiterated both in the record and in the

briefs. (See: Order of District Court of December 30,

1959, R. 29; Order of the District Court of March 9,

1960, R. 43-46; Order of the District Court of September

8, 1960, R. 48-53; Order of the District Court of June

7

16, 1959, R: 165; Brief in Opposition to Petition for

Certiorari, pp. 4, 6; Brief for Respondents, pp. 2, 3;

Brief for the State of Georgia as Amicus Curiae, pp. 2,

3.)

QUESTION:

Does Atlanta now have or has it ever had inflexible

attendance zones for each school? (This question was

raised by several Justices but was perhaps put in best

perspective by Mr. Justice White, who asked the precise

question whether the District Court made any finding

as to the use of attendance lines.)

ANSWER:

The District Court found as follows (R. 158) :

“ Neither does the evidence show that defendants

are maintaining a ‘dual system of school attendance

area lines.’ Proximity to the schools in question is

a factor considered by the defendant Board. It is

not shown that defendants are acting arbitrarily in

connection with the assignment of pupils in rela

tion to their distance from the school. It does ap

pear that area lines (where such exist) are some

times changed for the sole purpose of relieving

overcrowded conditions in the schools.”

On the question of lines the Court of Appeals also

found (R. 234) that:

“ He [the School Superintendent] testified that

there were no attendance areas or zone lines es

tablished by the board, but that lines are sometimes

drawn administratively between schools in an at

tempt to equalize class loads. There was no evidence

8

before the court that they were based on race. The

Atlanta system is divided into five sub-areas with an

assistant superintendent in charge of each area. One

sub-area has only Negro schools in it, but there is

no evidence of white children living in it, or that

it resulted from gerrymandering.”

In his dissenting opinion Judge Rives challenges these

statements (R. 250, Footnote 4) . With all deference to

Judge Rives and to the District Court, the statement

made in the majority opinion in the Circuit Court more

correctly states the facts.1 For administrative purposes,

as distinguished from attendance, the school board has

divided the City of Atlanta into five administrative areas,

each under an area superintendent (R. 234) . Atlanta

has no “ official attendance lines. There are administra

tive lines drawn by individual schools on occasion to

equalize the load in various schools.” (R. 61.) “ There

are no official lines in this city.” (R. 98, 99.) (See also

R. 104-105.)

RESOLUTION OF THE ATLANTA BOARD OF

EDUCATION.

A regularly called meeting of the Atlanta Board of

Education was held at the administrative offices of the

Board on April 8, 1964. All members of the Board were

present.

A report was received from Mr. A. C. Latimer, Mr.

Newell Edenfield, and Mr. J. Lee Perry, the attorneys

1 A reading of the testimony quoted in footnote 4 of Judge Rives’

dissent (R. 250) will reveal that the line of inquiry was with

respect to elementary schools which, of course, have not been

reached by the plan at this date. (R. 61-62).

who appeared for the Board in the case of Calhoun v.

Latimer before the Supreme Court of the United States.

It was reported by the attorneys that at the time of

argument the Court was somewhat confused as to exactly

what issues were presented for decision, inasmuch as

the record in the case was originally made during the

1961-62 school year, and particularly because neither in

the record nor elsewhere did it appear what, policy was

to be followed by the Board in making assignments and

granting transfers under the plan of desegregation for

the school year 1964-65.

By reason of the foregoing and in the light of certain

questions asked by the Justices during argument, the at

torneys were requested by the Court to furnish to the

Court such documents, minutes or resolutions, or other

actions of the Board as would indicate the exact position

of the Board on these questions. The attorneys there

upon requested the Board to adopt such a resolution

for the benefit of the Court stating unequivocally the

present policy of the Board and the factors to be con

sidered by it in making initial assignment of pupils and

in permitting transfers for the school year 1964-65.

U pon motion made and seconded, the following resolu

tion was adopted by a unanimous vote:

“ BE IT RESOLVED: That for the school year

beginning August 24, 1964, all pupils entering the

eighth grade from elementary schools be assigned

among the various high schools without regard to

race, after consideration of the following factors:

1. Choice of the pupil or his parents;

2. Availability of facilities; and

10

3. Proximity of the school to place of residence.

“ BE IT FURTH ER RESOLVED: That among

those seeking to attend a particular school, where

facilities are not available for all, priority shall be

based on proximity, except that for justifiable edu

cational reasons and in hardship cases other factors

not related to race may be applied. Administrative

assignments or reassignments may be made in cases

of overcrowding, in hardship cases, and for disci

plinary reasons. When such administrative assign

ments are made they shall be based on relative

proximity and available facilities, giving considera

tion to pupil choice where possible.

“ BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED: That in

those grades already reached by the Atlanta plan of

desegregation (ninth, tenth, eleventh and twelfth

grades) , transfers be freely granted according to the

criteria hereinbefore provided, without formal ap

plication, other than the usual pre-registration re

quired of all students.

“ BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED: That where

a student has exercised his choice of schools, either

by initial assignment to the eighth grade or by

transfer, as herein provided, further and additional

transfers will be permitted only in hardship cases

or for valid educational reasons unrelated to race.

“ BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED: That a

certified copy of this resolution be furnished to the

attorneys for transmission to the Supreme Court of

the United States in accordance with its direction.”

11

CERTIFICATE

I, Louise Simpson, Secretary of the Atlanta Board of

Education, do certify that the within and foregoing con

stitutes a true and correct transcript of a resolution

adopted by the Atlanta Board of Education in regular

called session held on the 8th day of April, 1964.

L ouise Simpson ,

Secretary.

(SEAL)

12

AFFIDAVIT OF THE ATLANTA

SUPERINTENDENT OF SCHOOLS,

GEORGIA,

FULTON COUNTY

Personally before the undersigned officer authorized

to administer oaths appeared JOHN W. LETSON, who,

being duly sworn, deposes and says that he is Superin

tendent of Schools in the City of Atlanta, Georgia, and

that he makes this affidavit to be furnished to the Su

preme Court of the United States for the purpose of

clarifying and eliminating any uncertainty as to what are

the present policies of the Atlanta School Board with

respect to the assignment and transfer of pupils pursuant

to the plan of desegregation originally adopted pursuant

to court order in 1959.

Affiant deposes and says that in the opinion of the

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit (on petition for

rehearing), the Court held:

“ The corrective action necessary in light of the

deficiencies will entail the application of the plan

in an even handed manner without regard to race

to all assignments of pupils new to a school for ad

mission in a desegregated grade in that school; and

to all transfers whether formal, informal or other

wise. Personality interviews to determine probable

success or failure in the schools to which transfer

and assignment is sought may not be utilized where

such a practice relates only to Negro pupils as was

the case. No standard requiring that a transferee

score a grade on scholastic ability and achievement

tests equal to the average of the class in the school

to which transfer is sought may be utilized, nor may

13

any scholastic requirement whatever be used where

applied only to Negro students seeking transfer and

assignment as was the case in Atlanta in the ad

ministration of the plan approved by the District

Court. The opinion is modified to make it clear

that this corrective action must apply to transfers

and assignments for the 1963-64 school term to the

extent, if any, that the practices giving rise to the

deficiencies may have been continued in use.”

Affiant further says that upon the rendition of the

judgment quoted, it was publicly stated by him, on be

half of the Atlanta Board of Education, that under the

decision initial assignments could be made and transfers

determined only on the basis of freedom of choice,

available facilities, proximity, or other valid educational

reasons, not related to race.

Affiant shows that pursuant to the conclusions stated,

and in what they conceived to be compliance therewith,

the Board caused all previous applications for transfer

to be reconsidered and further caused each of said trans

fers which had been denied to be granted, provided only

that the school to which transfer was sought was nearer

to the place of residence of the student than the school

then attended.

Affiant shows that the foregoing conclusions of neces

sity would not appear on the record in the Supreme

Court of the United States because they represented

policies which were and could only have been adopted

subsequent to the decision of the Circuit Court on

August 16, 1963.

Affiant says further that said policies were publicly re

ported at the time of the reconsideration of transfer ap

14

plications following receipt of the Circuit Court opinion.

Administrative regulations were not formulated and

distributed because it has always been the policy of the

Board since the adoption of the original plan to announce

administrative regulations for the assignment and trans

fer of pupils by a regulation promulgated in the spring

of each school year to be effective during the following

school year.

With respect to “ freedom of choice” as distinguished

from “ proximity” in making assignments and transfers,

affiant shows that such a factor was among those con

tained in the original plan, that all transfers heretofore

granted pursuant to the plan were initiated pursuant to

choice, and that for administrative reasons wholly un

related to race, Atlanta prefers to continue to give rec

ognition to choice, as well as proximity, in making as

signments and transfers in the future.

John W. L etson

Sworn to and subscribed before me this 10th day of

April, 1964.

Fannie R. K night

Notary Public

Notary Public, Georgia, State at Large.

(SEAL). My Commission Expires Jan. 26, 1966.

Respectfully submitted,

A. C. L atim er , Attorney for

Atlanta Board of Education

N ew ell Edenfield,

Of Counsel

V':/