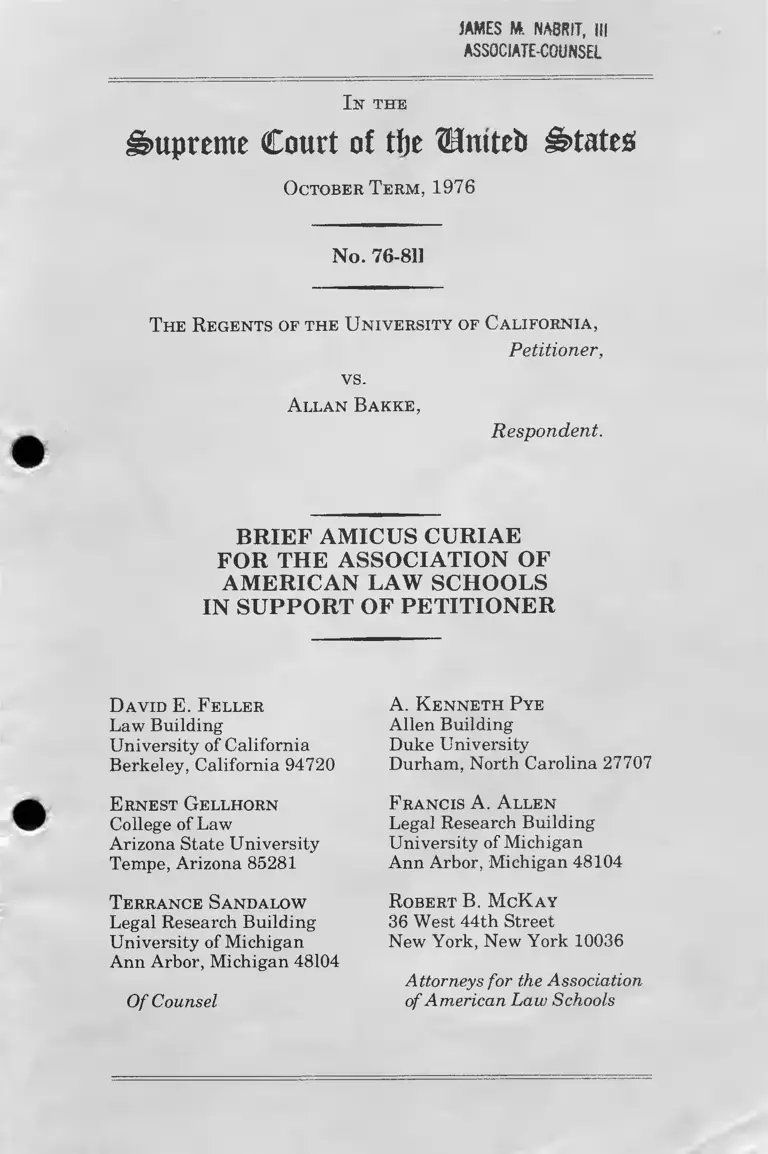

Bakke v. Regents Brief Amicus Curiae for the Association of American Law Schools in Support of Petitioner

Public Court Documents

June 7, 1977

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bakke v. Regents Brief Amicus Curiae for the Association of American Law Schools in Support of Petitioner, 1977. 4006c147-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1c386059-d92c-4fe3-9c98-e65188a54360/bakke-v-regents-brief-amicus-curiae-for-the-association-of-american-law-schools-in-support-of-petitioner. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

JAMES M. NA8R!T, III

ASSOCIATE-COU N S El

I n th e

Supreme Court of tfje Untteb States

October T er m , 1976

N o . 7 6 -8 1 1

T he Regents of the U niversity of Ca lifornia ,

Petitioner,

vs.

A llan Rakke ,

Respondent.

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE

FOR THE ASSOCIATION OF

AMERICAN LAW SCHOOLS

IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER

D avid E. F eller

Law Building

University of California

Berkeley, California 94720

E rnest Gellhorn

College of Law

Arizona State University

Tempe, Arizona 85281

T errance Sandalow

Legal Research Building

University of Michigan

Ann Arbor, Michigan 48104

Of Counsel

A. K e n n e th P ye

Allen Building

Duke University

Durham, North Carolina 27707

F rancis A. A llen

Legal Research Building

University of Michigan

Ann Arbor, Michigan 48104

Robert B. M cK ay

36 West 44th Street

New York, New York 10036

Attorneys for the Association

of American Law Schools

INDEX

Page

In terest of the Amicus ....................................................... 1

Sum m ary of A rgum ent ...................... .............................. 3

Introduction ......................................................................... 5

I. Without Minority Admission Programs Minority Stu

dents Would Be Excluded From American Law

Schools ............................................................................ 8

A. The Number of Qualified Applicants Exceeds The

Number of Openings in Law School ...................... 9

B. Numerical Predictors Indicate Which Applicants

Are Most Likely To Succeed In Law School ......... 12

C. The Admissions Process Is Designed To Identify

Which Of The Qualified Applicants Should Be Ad

mitted ..................................................................... 17

D. The Use of Race as a Factor In The Admissions Pro

cess Is Necessary If There Are To Be A Substantial

Number of Minority Students In Law School . . . . 21

1. The Special Admissions Programs ..................... 22

2. Minority Students Would Be Almost Eliminated

From Law School Without Special Admissions

Programs ............................................................. 27

3. No Reasonable Alternatives To Special Admis

sions Programs Have Been Proposed ............... 32

II. Special Minority Admissions Programs Serve Compel

ling Social Interests ...................................................... 39

A. The Need For More Minority Lawyers is Critical 42

1. The Public Role of the Legal Profession ............ 43

2. Serving the Legal Needs of Minority Com

munities ............................................................. 47

B. A Racially Diverse Student Body Is Important For A

Sound Legal Education ............................................. 49

C. Minority Group Lawyers Will Contribute To The

Social Mobility of Racial Minorities ......................... 53

11

D. Special Admissions Effectively Respond To The

Need For More Minority Lawyers .......................... 54

1. Success at School ................................................. 56

2. Success in Passing the Bar ................................ 59

3. The Argument on Stigmatization .................... 61

III. Special Admissions Programs Are Fully Consistent

With The Constitution .................................................... 63

Conclusion .............................................................................. 66

Ill

TABLES OF AUTHORITY

Table of Cases: Pages

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) ....... 4, 39, 54

Califano v. Webster, 97 S.Ct. 1192 (1977) ............................ 65

Cipriano v. City of Houma, 395 U.S. 701, 704 (1969) ......... 63

DeFunis v. Odegaard, 416 U.S. 312, 320 (1974) . . . .8, 10, 32, 47

Dred Scott v. Sanford, 19 How. 393 (1857) .......................... 39

Dunn v. Blumstein, 405 U.S. 330 (1972) .............................. 63

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1880) ................... 39

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402

U.S. 1, 16(1971) 52,64

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629, 634 (1950) ........................ 50

United Jewish Organizations of Williamsburgh v. Carey, 97

S. Ct. 996 (1977) 64,65

Other Authority:

ABA, Law Schools and Bar Admission Requirements (1950)-

(1976) ................................................................................ 58

ABA, Law Schools and Bar Admission Requirements: A Re

view of Legal Education in the United States 42, 45

(1976) ................................................................................ 7

Altesek & Gomberg, Bachelor’s Degrees Awarded to Minority

Students 1973-1974, at 4 33

Angoff & Herring, Study of the Appropriateness of the Law

School Admission Test for Canadian and A merican Stu

dents, LSAC 71-1, in 2 Law School Admission Research

(1976) .......................................................................... . • • 13

Bureau of the Census, Current Population Reports, Series

P-60, No. 103. "Money Income and Poverty Status of

Families and Persons in the United States: 1975 and

1974 Revisions” (Advance Report 1976) ...................36, 37

Bureau of the Census, Detailed Characteristics of the Popula

tion, Table 223 (1970) ................................................ 40

Bureau of the Census, Statistical Abstract of the United

States, Table 271, at 162 (1976) ............................... . 46

California Legislative Analysis of the 1976-77 Budget Bill,

Report of the Legislative Analyst to the Joint Legislative

Budget Committee 820 (1976) ......................................... 60

Carlson, Factor Analysis and Validity Study of the Law

School Admission Test Battery, LSAC 70-3, in 2 Law

School Admission Research 11 (1976) .......................... 14

IV

Carlson & Werts, Relationships Among Law School Pre

dictors, Law School Performance, and Bar Examination

Results, LSAC 76-1, at vii (1976) .................................. 60

CLEO, Annual Report of Executive Director (1976) 60

Columbia University Bulletin, School of Law, 96-97 (1976) . 18

A. de Tocqueville, Democracy in America 329-30 (Schocken

ed. 1961) 44

Employee Selection Guidelines. 41 Fed. Reg. 51733 (Nov. 23,

̂ 1976) .................................................................................. 34

EEOC Guidelines on Employee Selection Procedures, 29

C.F.R. 1607.1 (1976) ........................................................ 34

Evans, Applications and Admissions to ABA Accredited Law

Schools: An Analysis of National Data for the Class En

tering in the Fall 1976 (Law School Admission Council

1977) ................................................ 7, 28-34, 37, 38, 50, 55

Evans & Reilly, A Study of Speededness as a Source of Test

Bias, LSAC 71-2, in 2 Law School Admission Research

111 (1976) ........................................................................ 13

Evans & Reilly, The LSAT Speededness Study Revisited:

Final Report, LSAC 72-3, in 2 Law School Admission

Research 191 (1976) 13

Fleming & Poliak, The Black Quota at Yale Law School—An

Exchange of Letters, 19 The Public Interest 44, at 45

(Spring 1970) 55

Gellhorn, The Law Schools and the Negro, 1968 Duke L.J.

1069, 1073-74 ................................................................... 43

Hart & Evans, Major Research Efforts of the Law School A d

mission Council, in Law School Admission Research

(LSAC 1976) ..................................................................... 13

Hinds, Keynote Introduction: "The Minority Candidate and

the Bar Examination,” 5 Black L.J. 123, 124-36(1977) . 59

Hughes, McKay & Winograd, The Disadvantaged Student

and Preparation for Legal Education: The New York

University Experience, 1970 Tol. L. Rev. 701 ............... 56

In re Griffiths, 413 U.S. 717 (1973) ....................................... 63

Kaplan, Equal Justice in an Unequal World: Equality for the

Negro—The Problem of Special Treatment, 61 Nw. U. L.

Rev. 361, 410 (1966) ........................................................ 38

Law School Admission Council, Reports of LSAC Sponsored

Research, vols. 1 & 2 (1976) 12

Linn & Winograd, New York University Admissions Inter

view Study, LSAC 69-2, in 1 Law School Admission 547

(1976) 16

LSAT Handbook 47 (1964) .................................................... 15

Nicholson, The Law Schools of the United States 26, 217

(1958) ............................................................................ 9, 10

V

1972-1973 Prelaw Handbook 153, 345 (1972) .................

1976-77Prelaw Handbook 153,375 (1976) ...................... 18,

Pitcher, Predicting Law School Grades for Female Law Stu

dents, LSAC 74-3, in 2 Law School Admission Research

555 (1976) ......................................................................

Rappaport, The Case for Law School Minority Programs, Los

Angeles Times, Opinions Section, p. 1 (Mar. 14, 1976)..

Redish, Preferential School Admissions and theEqualProtec-

tion Clause: An Analysis of the Competing Arguments, 22

UCLA L. Rev. 343 (1974) ..............................................

Reilly, Contributions of Selected Transcript Information to

Prediction of Law School Performance, LSAC 71-4 in 2

Law School Admission Research 133 (1976) .................

Reilly & Powers, Extended Study of the Relationship of

Selected Transcript Information to Law School Per

formance, LSAC 73-4, in 2 Law School Admission Re

search 405 (1976) ...........................................................

Report of Minority Groups Project in AALS Proceedings 172

(1965) .............................................................................. 7,

Report on Special Admissions at Boalt Hall After Bakke, 28 J.

Legal Ed. 363 (1977) ..............................................; • • 19,

Sandalow, Racial Preferences in Higher Education: Political

Responsibility and the Judicial Role, 42 U. Chi. L. Rev.

653,684(1975) .............................................. .................

Schrader & Pitcher, Adjusted Undergraduate Average.

Grades as Predictors of Law School Performance, LSAC

64-2, in 1 Law School Admission Research 291 (1976) . .

Schrader & Pitcher, Effect of Differences in College Grading

Standards on the Prediction of Law School Grades, LSAC

73-5, in 2 Law School Admission Research 451 (1976)..

Schrader, Pitcher & Winterbottom, The Interpretation of Law

School Admission Test Scores for Culturally Deprived

and Non-white Candidates, LSAC 66-3, in 1 Law School

Admission Research 375 (1976) .....................................

Schrader & Pitcher, The Interpretation of Law School Admis

sion Test Scores for Culturally Deprived Candidates: An

Extension of the 1966 Study Rased on Five Additional

Law Schools, LSAC 72-5, in 2 Law School Admission Re

search 227 (1976) ...........................................................

Schrader & Pitcher, Predicting Law School Grades for Black

American Law Students, LSAC 73-6, in 2 Law School

Admission Research 451 (1976) .....................................

55

55

13

60

63

14

14

22

, 27

52

14

14

13

13

13

VI

Schrader & Pitcher prediction of Law School Grades for Mex

ican American and Black American Students, LSAC

74-8,in2LawSchoolAdmissionResearch715(1976). . . 13

State Bar of California, Report of Commission to Study the

Bar Examination Process (1973) 60

Symposium, Disadvantaged Students and Legal E du

cation—Programs for Affirmative Action, 1970 Tol. L.

Rev. 277 ............................................................................. 22

University of Virginia Record 1976-77, School of Law, 55

(1976) ................................................................................ 19

Warren, Panel on "Factors Contributing to Bar Examination

Failure,” 5 Black L.J. 149-52 (1977) .............................. 60

White, Legal Education: A Time of Change, 66 A.B.A.J. 355,

356 (1976) ......................................................................... 11

I n t h e

S u p r e m e C o u r t of tfje U n tte b S t a t e s

October T er m , 1976

N o. 76-811

T he R egents of the U niversity of California ,

Petitioner,

vs.

A llan Bakke ,

Respondent.

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE

FOR THE ASSOCIATION OF

AMERICAN LAW SCHOOLS

IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER

This brief amicus curiae is filed by the Association of

American Law Schools w ith the consent of the parties, as

provided for in Rule 42 of the Rules of th is Court.

IN T E R E ST OF TH E AM IC U S

The Association of American Law Schools (AALS) has a

membership of 132 law schools, all of which are approved by

the American Bar Association. The purpose of the AALS is

"improvement of the legal profession through legal educa

tion.” It participates in developments affecting legal educa

tion, serves as a repository of inform ation about legal educa-

2

tion and assists in developing policy on national issues of

legal education.

The Association’s in terest in th is case derives from the

im pact th a t th is Court’s decision will have on legal educa

tion and the legal profession. Although the decision of the

court below arises from adm issions to a medical school, the

admissions processes of law schools are sufficiently sim ilar

to those of medical schools to be affected directly by any deci

sion in this case. Almost all m em ber schools of the AALS

have some form of special adm issions program designed to

in c rease th e n u m b e r of q u a lif ied m em bers of ra c ia l

m inorities who will en ter law school and become members of

the bar. The decision of the court below im perils these pro

gram s and therefore the progress made in the la st ten years

to include racial and ethnic m inorities1 in the legal profes

sion. Specifically, if th is Court were to hold th a t professional

schools including law schools could no longer take race into

account in the admissions process, the resu lt would be to ex

clude v irtually all m inorities from the legal profession. Be

cause of the ir im portance to the objective of achieving a m ul

tiracial bar, we are committed to these programs. We are

convinced th a t these carefully designed and thoughtfully

a d m in is te re d p ro g ram s re p re s e n t th e only re a lis t ic

possibility for increasing the very small num ber of m inority

group members in the legal profession and th a t they are

fully consistent w ith the Constitution.

1. Throughout this Brief, the terms "race,” "racial,” or "minorities,” are

based upon "standard race/ethnic categories” such as those defined by the

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission for its various information

reports. See 41 Fed. Reg. 17601-02 (April 27, 1976). They are generally

limited to four groups: black, Hispanic (primarily Chicano and Puerto Ri

can), Asian (including Pacific Islanders) and American Indian (including

Alaskan Native). There is some variance among schools about which

groups are eligible for inclusion in their special admissions programs be

cause of differing emphasis reflecting the concerns of their geographical

service areas. It appears that all include blacks, either Chicanos or Puerto

Ricans or both, and American Indians.

3

SUM M ARY OF A R G U M EN T

The imposition of a requirem ent th a t professional schools

forego any consideration of race in m aking admissions deci

sions would resu lt in substantially all-white law schools. It

is for th is reason th a t almost all accredited American law

schools have adopted "special admissions program s” which

give preference in admissions to blacks and members of

other "discrete and in su la r” minorities. As a consequence, in

a little over a decade the law schools have increased the ir

enrollm ent of m inority students from 700 or 1.3% (in 1964)

to over 9,500 or 8.1% (in 1976). These special admissions

program s have thereby sought to increase the num ber of

lawyers from m inority groups, a num ber which is still inor

dinately sm all a t under 2% of the entire bar.

A fter over a decade of searching, it is clear to the law

schools th a t there is no alternative available to them , other

than the use of race as a factor in admissions, if m inority

student representation among American law students is to

rise above a negligible level. For the s ta rk and unalterable

fact is th a t under today’s conditions, if indicators of academic

potential were used by law schools as the sole basis for de

term ining admission, "few m inority students would be ad

m itted to law school.” Despite wishful th inking and facile

generalizations to the contrary concerning the means avail

able to professional schools to increase m inority enrollm ent

w ithout special admissions, no alternative with any prospect

of success has been proposed. Those alternatives which have

been suggested would be ineffective and undesirable: they

would not resu lt in a substantial enrollm ent of m inority s tu

dents in the nation’s law schools, but they would lead to an

abandonm ent of intellectual promise and academic qualifi

cation as the standard by which schools determ ine w hether

an applicant shall be adm itted.

Special admissions program s are an in tegral p a rt of the

4

law school admissions process which is designed to provide

the community w ith the lawyers i t needs. Admission to law

school is not a prize granted as a rew ard for the most deserv

ing. Law schools are created and supported by the sta te to

m eet its needs for lawyers and legal services. Thus the ques

tion which the law schools address in the ir admissions pro

cesses, in the best way they can, is which among the m any

applicants will best serve those needs of society. In th is con

text, where m any more qualified candidates apply than

there are places in the schools, th a t decision has generally

been to select those students who show the most potential to

succeed in law school subject to other lim itations which also

serve the community. Thus, in addition to past (under

graduate) grades and test scores, law schools consider an ap

plicant’s background as well as his residence in deciding

w hether to adm it him. Background is a factor in obtaining a

diverse student body so im portant to comprehensive educa

tion; residence is im portant to governing boards who seek

lawyers to m eet local needs.

Reliance on race is a sim ilar lim itation used as a factor in

the admissions process to serve the com m unity’s interests. It

is p a rt of the com mitment, made clear by this Court in 1954

in Brown v. Board of Education and by Congress a decade

la te r in the Civil R ights Act of 1964, tow ard racial equality

and the full participation of racial m inorities in American

life. T hat need is as pressing and pervasive today as i t has

ever been: (1) lawyers play a critical, indeed a crucial role in

our society and the inclusion of m inorities in the bar is re

quired to achieve the ir participation in the governance of our

society, public as well as private; (2) the existence of race as

an im portant social elem ent m eans th a t m inority lawyers

are needed to serve the legal needs of m inority communities

who will not otherwise be served as they prefer; (3) racial

diversity is v ita l in the classroom if legal education is to be

5

effective and not isolated from the individuals and in s titu

tions w ith which law interacts; and (4) the opportunity to be

a lawyer is part of a larger effort by the nation to improve

the conditions of life of its least advantaged citizens. The

special adm issions program s in the overwhelming m ajority

of A m erican law schools are a direct response to these and

sim ilar needs. Unless allowed to continue, these needs and

the nation’s need for m inority lawyers will go unm et.

The equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amend

m ent should not be construed to require th a t the law schools

of the country abandon special admissions program s so es

sential to achieving these compelling objectives. These pro

gram s are aimed w ith precision a t the ir objectives of racially

in teg rating law schools and substantially increasing the

num ber of m inority lawyers. They m eet the most exacting

constitutional standard and are necessary if law schools are

to serve these compelling sta te in terests. These programs

also support the concept of equality and give m eaning to the

opportunity which equal protection is designed to serve.

IN T R O D U C TIO N

The purpose of this B rief is to dem onstrate a single propo

sition: the practice of providing a degree of preference for

blacks and other m inorities in law school admissions is a

necessary, and indeed the only honest method, to achieve

ce rta in very im p o rtan t social objectives. S ta ted more

bluntly, a holding th a t the Constitution requires th a t the

schools abjure any consideration of race as a factor in m ak

ing adm issions decisions m ust, unless covertly circum

vented, resu lt in substantially all-white schools.

The case before the Court is a medical school case. We ven

tu re no conclusion as to w hether the m atters which we here

present are applicable to the same degree to medical schools.

6

But the holding of the court below, th a t none of the criteria

used in selecting among applicants for adm ission to medical

school "can be related to race,” may also be equally applica

ble to schools of law. Our assum ption, therefore, is th a t if the

judgm ent of the court below in th is case is affirmed, the pub

licly-supported law schools of this country will be obliged to

conform the ir admissions practices to the principle tha t, in

selecting among applicants, no consideration may be given

to race, either explicitly or by indirection.

The im position of such a requ irem en t would require

changes in the admissions practices used by the vast major

ity of the accredited A m erican law schools. Most of them

have, in one way or another, and under various nam es and

guises, adopted "special adm issions” programs: practices

which give preference in admissions to blacks and members

of other "discrete and in su la r” minorities. The resu lt is th a t

for each of those schools there can be found unsuccessful ap

plicants, such as the p la in tiff in th is case, who rank higher

on the num erical adm issions criteria used by th a t school

than other applicants who have been adm itted because they

are members of a racial m inority. The object ofth is Brief is to

dem onstrate th a t such a resu lt is the necessary consequence

of a program designed to m eet certain im perative social

needs directly related to the purposes for which the schools

exist and th a t there is no other reasonable method by which

those needs can be met.

The imposition of a requirem ent th a t the admission of law

school applicants be made w ithout consideration of race

would v irtually wipe out the progress th a t has been made

toward the goals of an in tegrated bar and society. In little

over a decade the law schools have increased the ir enroll

m ent of m inority students from 700 or 1.3% to over 9,500 or

8.1%.2 The regrettable but unalterable fact is th a t under to

day’s conditions, if indicators of academic potential w ithout

7

regard to race were used by law schools as the sole basis for

determ ining admission, "few m inority students would be

adm itted to law school.” T hat is the stark conclusion of an

exhaustive study of more than 76,000 applications to law

school for the 1975-76 admission year th a t was confirmed by

a separate survey of 80% of all accredited law schools. See F.

Ev ans, Applications and Adm issions to A B A Accredited Law

Schools: A n Analysis o f National Data for the Class Entering

in the Fall 1976 (Law School Admission Council 1977) (here

inafter Evans Report). The findings of the Evans Report are

crucial to an understanding of w hat is a t stake in th is case. A

detailed discussion of its findings appear a t pages 27-32, in

fra, following a description of the admissions process, which

also m ust be carefully considered if these findings are to be

fully understood. For now, we urge only a full awareness of

the major conclusions to emerge from the Evans Report, th a t

affirmance of the decision below would, under either exist

ing admissions standards or any realistic alternative, ex

clude all but a m inuscule num ber of m inority students from

the nation’s law schools.

The dem onstration of these conclusions comprises the fol

lowing parts. F irst, we exam ine the admissions systems used

by American law schools today, w ithout regard to the racial

question. This is im portant because those practices, and the

conditions which give rise to them , are quite different from

2. The specific figures for ABA-approved law schools are:

Total

Minority

Enrollment

Total

Enrollment

1964

1976

700 (approx.)

9,524

54,265

117,451

Source: Report of Minority Groups Project in AALS Proceedings 172

(1965); ABA Law Schools and Bar Admission Requirements: A Review of

Legal Education in the United States 42, 45 (1976).

8

those, fam iliar to most members of the bar, th a t existed only

a few years ago. Second, we describe the process by which the

practice of providing some preference to applicants of certain

m inority groups has developed in the context of these new

and different admissions standards. An understanding of

th is process dem onstrates th a t under current societal condi

tions, conditions th a t we believe will in tim e disappear,

there is no feasible alternative to the use of some form of

racial preference if the presence of a significant num ber of

m inority students is to be achieved. Third, we show th a t the

presence of a significant num ber of law students from these

m inority groups serves im portant social and educational

purposes th a t cannot be m et under today’s conditions in any

other way. Finally, and in conclusion, we add a few words as

to why we believe the Constitution does not require th a t the

law schools of the country abandon program s so essential to

achieving these compelling objectives.

I. WITHOUT MINORITY ADMISSION PROGRAMS

MINORITY STUDENTS WOULD BE EXCLUDED

FROM AMERICAN LAW SCHOOLS

An adequate appreciation of the devastating im pact th a t

affirm ance of the decision below would have upon m inority

enrollm ent in law schools depends, initially , upon an under

standing of how admissions decisions are made, the facts

upon which they are based, and the purposes they serve. The

failure of such understanding can lead, as in the opinion

below and in the dissenting opinion of Mr. Justice Douglas in

DeFunis v. Odegaard, 416 U.S. 312, 320 (1974), to faulty

diagnoses of the problem th a t special admissions program s

address and to facile generalizations concerning the means

by which it can be solved. Both opinions assum e th a t means

exist by which law schools (or medical schools) can, by some

how altering the ir admissions criteria, m ain ta in substan tial

9

m inority enrollm ents w ithout consideration of race. An

understanding of the admissions process will dem onstrate

th a t this assum ption is based upon wishful th inking in ig

norance of the facts.

There is a second reason why it is im portant to understand

the selection process of law schools. A tendency exists to re

gard admission to law school as a prize to be awarded in ac

cordance w ith some principle of desert. But the goal th a t law

schools seek to serve in the admissions process is not th a t of

rew arding those applicants who are most deserving; adm is

sions are not simply handed out as aw ards for prior per

formance. R ather, law schools exist to provide the commu

nity w ith the lawyers it needs to serve its many purposes.

The question to which the schools therefore address them

selves, in the best way they can, is which of the m ultitude of

applicants to the school will best serve those needs.

A. The Number of Qualified Applicants Exceeds The

Number of Openings In Law School

The drastic change th a t has occurred in the admissions

processes of the law schools over the past few decades can

best be described by dividing its development into three

stages. The first stage was th a t era in which there was a

place in law school, v irtually any law school, for everyone

w ith m inim al credentials. Any applicant w ith a college de

gree from an accredited institu tion , and indeed many w ith

out, could find a place. Competence to perform as a law stu

dent was tested in the best possible way—by performance

itself. Those who dem onstrated the m inim um competence

required by the particu lar school were passed and those who

did not were washed out.3

3. The situation as it existed in 1948-49 is graphically described in L.

Nicholson, The Law Schools of the United States (1958), a report based on

136 questionnaires and inspections of 160 law schools prepared for the

10

Such a system is operable, however, only when there are

places available in law school sufficient to accommodate all

those possessing the m inim al educational qualifications.

When applications exceed the places available, some crite

rion of selection is required. The most n a tu ra l criterion, and

the one actually adopted by the law schools, was probable

success in completing the course of instruction. This is the

second stage in the development of the admissions process,

the stage a t which the Law School Admission Test (LSAT)

was developed as a tool for aiding predictions as to w hether

an applicant, if adm itted, would be able to m eet a school’s

m inim um level of performance. Since the dem and for adm is

sion as compared to the available places varies from school to

school, different schools reached th is stage and began using

the LSAT at different times.

W hen there are more com petent and qualified applicants

than there are available positions the question becomes

which applicants, of the m any who would be likely to suc

ceed, should be adm itted. At th is th ird stage, reached by dif

ferent schools a t different tim es, the demand by qualified

applicants for adm ission to law school far exceeds the

num ber of available positions. All or nearly all law schools

are now at this stage. Thus, in 1975, there were approxi-

ABA Survey of the Legal Profession. In 1948, 87% of the applicants to the

schools surveyed met the schools’ minimum requirements and 70% of the

applicants were accepted. Id. at 217. Descriptions taken from three inspec

tion reports typical of the "vast majority of schools,” were as follows:

"All qualified applicants have regularly been admitted to the law

school in recent years.”

"The school does not attempt to screen applicants over and above

the determination that they have complied with the minimum qual

itative and quantitative requirements.”

"In the year 1948-49,190 students entered upon the study of law in

this school; only 91 remained in school at the beginning of the follow

ing year. Forty of the 190 were flunked out, and 59 others quit volun

tarily, most of them persuaded so to do because of low grades.”

Id. at 26.

11

m ately 83,000 applicants for law school admission for the

39,038 first-year places opened for them in all ABA-approved

schools th a t year. There were, in short, a t least two appli

cants for each law school seat in the U nited S tates.4

Confronted w ith the necessity of choosing from among so

m any fully qualified applicants, alm ost all schools attem pt

to select, subject to the qualifications discussed below (pp.

18-20, infra), those applicants who are most likely to perform

best academically. The object, in other words, is no longer to

identify those students who can earn a C, but those who are

most likely to earn As and Bs.

In using th a t standard for admission, the schools are

guided by the assum ption th a t those who perform well in law

school are as a general rule likely to perform well in the pro

fession. We know, of course, th a t th is assumption is a t best

only a rough approxim ation. Law schools are concerned

prim arily w ith developing intellectual qualities-—analytic

skill, the m astery of legal concepts, and the ability to work

im aginatively w ith those concepts—th a t are im portant in

all the roles th a t lawyers may be called upon to perform. But

it is plain th a t there are additional qualities th a t are also

4. White, Legal Education: A Time of Change, 66 A.B.A.J. 355, 356

(1976) (based on LSD AS completions; the LSDAS column therein errone

ously reports for each year the following year’s data.)

Law School Data Assembly Service (LSDAS) completions understate

the number of college graduates applying to law school. In 1975, there

were 133,000 LSAT administrations, 50,000 more than the number of reg

istered applicants in LSDAS. Some of the difference is accounted for by

"repeaters,” students taking the test for the second time. Some of the dif

ference reflects potential applicants who were dissuaded from completing

the application process by low scores and some applicants were not re

quired by their law schools to register in LSDAS. This does not, however,

convey the full dimensions of the problem confronted by individual

schools, especially those perceived by applicants as most desirable. It is

not uncommon for law schools to receive as many as ten or fifteen applica

tions for each position in the first-year class, the largest number of which

are by applicants who would, it can be predicted with a high degree of

certainty, successfully complete the school’s academic program.

12

im portant, qualities th a t m ay well be different for the ju ry

lawyer, the appellate specialist, the counsellor and advisor,

the negotiator and the legislator.

In m aking adm issions decisions, however, law schools are

not able to address the full range of these qualities th a t go

into the m aking of a successful law yer because there are no

reliable guides, a t least yet,5 to the a ttribu tes of a "successful

lawyer.” Given the necessity of selection, a choice is the re

fore made in term s of a standard th a t the law schools can

m easure and apply, the expected performance of the appli

cant in school.

B. Numerical Predictors Indicate Which Applicants Are

Most Likely To Succeed In Law School

C entral to any understanding of the process by which law

schools ration the available spaces among qualified appli

cants is the role of the quan tita tive predictors.

We have already mentioned the LSAT. I t was first used in

1948. Since th a t tim e the test has been the subject of an

enormous volume of research under the sponsorship of the

Law School Admission Council (LSAC) which consists of a

representative from each school using the test (today identi

cal w ith the list of ABA-approved schools). This research,

now compiled in Law School Admission Council, Reports of

L SA C Sponsored Research , vols. 1 & 2 (1976), covering 72

separate research projects, has been dedicated not only to

scrutiny of the validity of the LSAT and its component parts

and to im provem ent in its content and structu re bu t also to

5. A major effort to study the relationships of predictors and success in

practice was begun in 1973 with the inauguration of the Competent

Lawyer Study, a joint project of the Association of American Law Schools,

Law School Admission Council, American Bar Foundation and National

Conference of Bar Examiners. The purpose of the study is to learn how to

identify, measure and predict the factors that go into performance as a

competent lawyer.

13

the search for other possible predictors of law school per

formance.6

Some of the resu lts of th a t research are worth noting. We

know, for example, th a t the test is not racially biased. Five

separate studies have indicated th a t the test does not under

predict the law school performance of blacks and Mexican-

A m ericans.7 We know th a t it is not sexually biased.8 We

know, even, th a t it predicts as well for Canadians as it does

for A m ericans.9 We know th a t questions designed to m ea

sure an applicant’s general background knowledge, which

6. For a summary of the result of this research, see Hart & Evans,

Major Research Efforts of the Law School Admission Council, in Law

School Admission Research (LSAC 1976).

7. Schrader, Pitcher & Winterbottom, The Interpretation of Law School

Admission T est Scores for Culturally Deprived and Non-white Candidates,

LSAC 66-3, in 1 Law School Admission Research 375 (1976); Flickinger,

Law School Admissions and the Culturally Deprived, printed with

Schrader & Pitcher, The Interpretation of Law School Admission Test

Scores for Culturally Deprived Candidates: An Extension of the 1966 Study

Based on Five Additional Law Schools, LSAC 72-5, in 2 Law School Ad

mission Research 227 (1976); Schrader & Pitcher, Predicting Law School

Grades for Black American Law Students, LSAC 73-6, in 2 Law School

Admission Research 451 (1976); Schrader & Pitcher, Prediction of Law

School Grades for Mexican American and Black American Students,

LSAC 74-8, in 2 Law School Admission Research 715 (1976).

Research has also been done as to whether there is any possible source of

bias in the "speededness” of the test, i.e., the question whether minority

candidates may not finish the test in as large a proportion as whites. The

first study indicated that, although speededness had a slight affect on

scores, there was no differential in that effect. Evans & Reilly, A Study of

Speededness as a Source of Test Bias, LSAC 71-2, in 2 Law School Admis

sion Research 111 (1976) and in 9 J. Educ. Measurement 123 (1972). A

second, extended study confirmed the absence of any differential effect.

Evans & Reilly, The LSA T Speededness Study Revisited: Final Report,

LSAC 72-3, in 2 Law School Admission Research 191 (1976).

8. Pitcher, Predicting Law School Grades for Female Law Students,

LSAC 74-3, in 2 Law School Admission Research 555 (1976).

9. Angoff & Herring, Study of the Appropriateness of the Law School

Admission Test for Canadian and American Students, LSAC 71-1, in 2

Law School Admission Research (1976).

14

were a t one tim e included in the test, bu t have since been

abandoned, add nothing to its predictive value.10 We know

th a t it is a useful and valid tool bu t th a t there is another

ind icato r of alm ost equal v a lid ity —the u n d erg rad u a te

grade-point average (GPA). And we know, finally, th a t these

two indicators combined constitute the best predictors of law

school performance th a t we have been able to devise.11

The validity of the LSAT, the GPA, and th e ir combination

as predictors is under constant scrutiny. Most schools which

use the LSAT subm it, usually once each year, the per

formance of each of the ir students in the first year as m ea

sured by grades. This record of performance is then m ea

sured against the LSAT and GPA of these students. A de

term ination is made as to the correlation of each of these

predictors, and of both combined, w ith performance; in addi

tion each school has a predicted index (or index number) pre-

10. Carlson, Factor Analysis and Validity Study of the Law School A d

mission Test Battery, LSAC 70-3, in 2 Law School Admission Research 11

(1976).

11. Efforts to find a consistent and systematic correlation with other

factors in order to improve the effectiveness of the combination of LSAT

and GPA have proved fruitless. Studies have been made, for example, of

the utility of factoring in the quality of the undergraduate schools as mea

sured by the average LSAT scores of their graduates. This has not proved

effective in increasing the predictive power of the LSAT and GPA com

bined. Schrader & Pitcher, Adjusted Undergraduate Average Grades as

Predictors of Law School Performance, LSAC 64-2, in 1 Law School Ad

mission Research 291 (1976); Schrader & Pitcher, Effect of Differences in

College Grading Standards on the Prediction of Law School Grades, LSAC

73-5, in 2 Law School Admission Research 451 (1976). Until recently a

separate weight was given to the score on the writing ability (WA) portion

of the LSAT but this was abandoned when it was found that it added little.

At one time it was thought that taking account of undergraduate major or

using the improvement in grades over the undergraduate career, rather

than simply the three-year average, would improve prediction. They did

not. Reilly, Contributions of Selected Transcript Information to Prediction

of Law School Performance, LSAC 71-4, in 2 Law School Admission Re

search 133 (1976); Reilly & Powers, Extended Study of the Relationship of

Selected Transcript Information to Law School Performance, LSAC 73-4,

in 2 Law School Admission Research 405 (1976).

15

pared for it in evaluating applicants in the succeeding year

based on the accuracy of the predictors in prior years.12

12. These studies not only validate the use of the composite of LSAT

and GPA by each school but, in addition, they also provide each school

annually with predictive formulas showing which combination of the two

(LSAT and GPA) have the highest validity based on performance at that

school in that year and in the three most recent years combined, as well as

one based on the experience of all law schools put together. The school can

choose whichever of these formulas it desires, or any other combination it

desires and, in the succeeding year ETS, through the Law School Data

Assembly Service (LSDAS), provides the school with an index, based on

the school’s specified formula, of each applicant’s predicted performance.

An illustration may be helpful. Assume that a study of the 1975 enter

ing class at a particular school reveals that the grades earned by the mem

bers of that class would have been best predicted by a formula that sums

the LSAT score and the product of 135 times the GPA. (Since LSAT is

scored on a 200-800 scale and GPA on a 4-point scale the assumed formula

involves a determination, today generally accurate, that the LSAT is a

somewhat better predictor than the GPA.) In the following year, i.e., for

applicants to the class of 1976, the LSDAS will, using that formula or any

other requested, provide an index number for each applicant. This can, if

requested, be given in terms of the particular school’s grading system.

This is the predicted first-year average (PFYA or PG A) referred to in the

brief filed by the deans of the four publicly-supported California law

schools in support of the petition for certiorari.

Such predictions are, however, only statements of probability and hence

are necessarily imperfect. The degree of probability is expressed in a corre

lation coefficient. A school whose index number has a correlation co

efficient of .45 and which admitted 100 students would normally expect to

find that at the end of their first year, 8 of the top 20 who had the highest

index numbers would be in the top 20 students. But the top 20 students

would also include 1 or 2 whose index numbers were in the bottom 20% of

those admitted. Conversely, 8 of the students with the lowest index num

bers, and 1 or 2 of those with the highest, would probably be represented in

the bottom 20% of the class. Finally, it is worth pointing out that a major

ity of both the highest ranking 20% and the lowest ranking 20% of admit

ted applicants are likely to end up in the middle 60% of the class. See

LSAT Handbook 47 (1964).

Over the past few years, the correlation between the index number em

ployed by most schools and the performance of their first-year students

has ranged between .3 and .5, with some as high as .7. The mean validity is

.45. Because a .45 correlation can be said to mean that the index accounts

for only 20% of the rank order of student performance, there are those who

have argued that the correlation of LSAT and GPA with law school per

formance is so low as to make the use of these predictors unnecessary or

undesirable. One answer to that argument is that, though far from perfect,

16

None of this is m eant to suggest th a t the law schools of this

country should, or do, rely entirely on the num erical indi

cators. While on average they are valid and reliable, they

state in essence only a probability of relative performance.

The probability th a t a selection based on these predictors

the combined LSAT-GPA index is the best predictor available. Extensive

efforts to use interviews or other subjective methods of evaluation of can

didates for law school have never proved valid when tested against actual

performance. See Linn & Winograd, New York University Admissions

Interview Study, LSAC 69-2, in 1 Law School Admission 547 (1976). This is

in accord with the available scientific evidence that predictors such as the

LSAT are in general likely to be more accurate than subjective evaluation.

The greater efficiency of the combination of LSAT and GPA is explained

by the fact that the latter may measure motivation and study habits, fac

tors not measured by the LSAT.

Moreover, the argument that a .45 correlation is too low to justify use of

the index fails to take account of the phenomenon technically known as

"range restriction” and thereby understates the utility of the index as a

predictor. "Range restriction” can be illustrated by a simple example. It is

a fact that there is a very strong relationship between the height and

weight of human beings. If a randomly selected sample were taken, the

correlation coefficient between these two quantities would be very high.

There are a few short but very heavy people and a few tall bean poles, but

on the average it is true that the taller a person is the more he weighs. But

it is also true that as the differences in height decrease the correlation

decreases: it is much less certain that a person 6'1" tall is heavier than one

who is just 6' than it is that a 6' person is heavier than a 5' person. A

correlation coefficient of height and weight among, let us say, professional

basketball players would therefore be much lower than one in which the

population as a whole were being measured.

Just so with law school admissions. Since almost all American law

schools tend to select those who have the higher scores, the correlation

coefficient is very much lower than it would be if all who applied were

admitted. The greater the weight given to the index in admissions the

lower the correlation coefficient. But the drop in the correlation coefficient

says nothing as to the efficiency and effectiveness of the index as a dis

criminator between those accepted and the vast majority who are

rejected—it measures only the efficient use of the index in predicting the

relative position of those accepted The "range restriction” phenomenon at

least partly explains the difference between the relatively high correla

tion coefficient of .67 for the University of California at Berkeley (Boalt

Hall) and the more typical .45. Although Boalt Hall accepts only a small

proportion of those who apply to it, including minorities, it does have a

larger "special admissions” program than most schools and therefore ex

hibits a somewhat smaller "range restriction” effect.

17

will in fact select the candidates who will perform best is

very high if the difference in the indices is large but it is low

when the indices are sim ilar. Given the large volume of ap

plications the u ltim ate decision may have to be made among

applicants who have very sim ilar index scores. It is for this

reason, among others, th a t the schools generally use those

predictors in combination with other inform ation th a t they

have about applicants. We now tu rn to the process by which

they do so.

C. The Adm issions Process Is Designed To Identify Which

Of The Qualified Applicants Should Be Admitted

A lthough the specific procedure varies from school to

school, the following describes in general term s the m ain

features of the regu lar admissions process a t most schools.

The first step is to reduce the num ber of files th a t can be

given detailed exam ination to a m anageable number. This is

done on the basis of the index num bers except where quick

exam ination of the file indicates tha t, for some reason, the

num bers are not indicative of probable performance. Those

having the highest indices are adm itted and a larger num ber

are denied, not because they are unqualified, although some

may be, bu t simply because the ir performance as predicted

by the index will probably be lower than th a t of the group to

be given detailed exam ination. After th is in itia l screening,

then each school, in its own way, attem pts to make the best

possible prediction as to the relative quality of the appli

cants. Everything th a t is known about them is taken into

consideration: the applicants’ personal statem ents, the ir

work histories, the na tu re of the subjects taken in under

g rad u a te college, differences in the k ind of education

provided by different colleges or differences in grading s tan

dards between colleges, the trend of an applicant’s under

graduate grades, the possible effect of a disadvantaged

18

background upon the validity of the predicted performance,

and every other factor th a t the particu lar school th inks can

possibly be utilized in m aking a judgm ent as to the relative

quality of the applicants.

The admissions process thus involves more than the use of

test scores and grades.13 All, or v irtually all schools use

w hatever inform ation they believe, in the best exercise of

the ir professional judgm ents, will indicate the relative abil

ity of the applicants to perform in law school. W hatever fac

tors a particu lar school considers, i t seeks to pick the most

promising candidates from among those who apply for ad

mission to it.

The last sta tem ent is subject to an im portant qualifica

tion. The effort of each school to identify and select those

applicants most likely to perform successfully is subject to

certain overrides. The first of these is the desire for diversity.

Faculties generally believe th a t a process th a t produces a

homogeneous student body, all of the members of which

share a common history, is unlikely to provide an atm o

sphere for effective education in the law. Thus, an adm is

sions committee is likely to give preference to diverse back

grounds and experiences, perhaps selecting an experienced

businessm an, a prison guard, a psychiatrist or a newspaper

reporter over a recently graduated college senior who would

be likely to perform better academically.14

13. Almost all schools admit students other than "on the numbers.”

This can be seen dramatically by inspecting the profiles of admissions at

almost any school as shown in the 1976-77 Prelaw Handbook. One

school, for example, rejected 15 of 94 applicants in 1976 who had LSAT

scores between 650 and 699 and also had undergraduate grade point aver

ages between 3.50 and 3.74. But it accepted 32 applicants who had LSAT’s

below 600 and undergraduate grade point averages below 3.49. These fig

ures exclude admissions under what that school calls its "special experi

mental” program. Id. at 237.

14. See, e . g Columbia University Bulletin, School of Law, 96-97 (1976).

The procedure used at the University of Virginia School of Law is typical:

19

A nother override typical of most state-supported schools is

a m andated preference for residents of the state, usually ex

pressed as a maxim um percentage of the students not regis

tered in the state who may be adm itted. Such a preference

serves a t least two purposes—increasing the opportunities

for professional education for those whose families support

the institu tions and increasing the likelihood th a t graduates

of the school will rem ain in the state to meet its needs for

legal services. The effect of the preference is, of course, th a t

the school will be required to reject some nonresidents who

would be likely to perform more successfully than some resi

dents who are adm itted.

The final override, and the one this case is about, is race.

The plain fact of the m atter is th a t were it not for this over

ride the admissions processes of the nation’s law schools,

tak ing into account all of the factors we have described,

would produce very few students who are members of racial

Even in dealing with the large application volume, encountered

during the last several years, the admissions committee believes that

absolute standards based on a combination of LSAT score and under

graduate grade-point average (GPA) are not the best way to select an

entering class. Consequently, the committee considers a broad array

of elements in addition to the essential factors of LSAT and GPA, with

a view toward assembling a diverse group while at the same time

arriving at a fair appraisal of the individual applicant.

Because of this approach it is difficult to predict what action may be

taken on an individual application. The LSAT score and under

graduate GPA constitute the bulk of the committee’s consideration;

usually about 80 percent total weighting is accorded these two factors.

However, there are other elements taken into account; the maturing

effect of an individual some years away from formal education; a ris

ing trend in academic performance versus solid but unexceptional

work; financial pressure requiring employment during the under

graduate years; significant personal achievement in extracurricular

work at college or in a work or military situation; unusual prior train

ing which promises a significant contribution to the law school com

munity. Other, similar factors are also considered.

University of Virginia Record 1976-77, School of Law, 55 (1976). A more

complete report of the factors used and the admissions process relied on at

another school appears at 28 J. Leg. Ed. 363, 378 (1977).

2 0

minorities. This has led to the creation of "special adm is

sions program s” designed to produce decisions different from

those th a t would be produced if the process were conducted

in a racially neu tra l way.

Each of the overrides has a purpose. Single-minded devo

tion to predictions of probable academic excellence undoubt

edly would increase the num ber of graduates who possess

the highest levels of the intellectual qualities im portant to

the practice of law, but th a t is not the only purpose for which

a law school, particu larly a state-supported law school,

exists. If a single standard of probable performance is used, a

defined group having lower levels of predicted performance

may be entirely excluded, even though many in th a t group

will perform as well or b e tte r than those adm itted. The only

solution, if this resu lt is to be avoided, is to apply a somewhat

lower standard for th a t group but one which will still assure

a high probability of success.

These overrides are not w ithout cost. F irst, since the best

predictors express only probabilities, a higher percentage of

those in the preferred group may encounter academic dif

ficulties (although it is impossible in advance to say which

ones). Second, the use of different standards for different

groups m eans th a t some w ell-qualified applicants who

would otherwise be adm itted will be rejected. But those costs

are balanced by the cost of the a lternative—nam ely, the de

nial of admission to well-qualified residents and m inority

applicants because the school has selected only those who

are most certain to succeed.

There is, in short, no free lunch. As long as the num ber of

qualified applicants exceeds the num ber of persons who can

be adm itted, some applicants m ust suffer the disappoint

m ent of being denied admission. U nder fair procedures th a t

determ ine which applicants do (and do not) meet the school’s

admissions criteria, the only issue of law is w hether the ad-

r

21

m issions c rite ria employed advance perm issible public

policies. The mere fact, regrettable as i t may be, th a t some

qualified applicants have been denied admission is not rele

v an t to th a t issue, for th a t resu lt is inevitable under any

criteria.

Our description of the admissions process has been offered

to underline the proposition tha t, subject to the overrides

specified, each law school decides w hether to adm it or reject

the thousands of applications received on its best estim ate of

the relative performance of the applicants to th a t school as

law students. The focus of the admissions decision is not on

which of the applicants is the most deserving but, if you will,

on the product: which of the applicants will best serve the

purpose for which the school was created, th a t of supplying

professionals needed by the community. Preferences based

on residence or on the desire for diversity in the student body

are clearly related to th a t purpose. Preferences for members

of certain m inority groups equally serve th a t purpose. This

brings us directly to the question of race.

D. The Use of Race as a Factor In The Admissions Process

Is N escessary If There Are To Be A Substantial Number

Of Minority Students In Law School

Our consideration of the use of race in law school adm is

sions is in three parts. We first set out in brief compass, and

in fairly general term s, the history and the natu re of special

admissions program s used by law schools to in tegrate the ir

student bodies. N ext we consider w hat the im pact would be

of a forced abandonm ent of these program s designed to in

crease m inority enrollm ent in law school. W hat, in other

words, would be the effect of a race-blind system of admission

upon the racial mix of applicants who would be adm itted to

the schools if they adhered to current admissions criteria of

probable academ ic success and d iversity (excluding of

22

course, racial diversity). F inally we explain why there are no

reasonable alternatives to reliance on the race-conscious

admissions procedures if m inority admissions are to be at

more than a token level and why the proposed racially neu

tra l solutions, including those suggested by the Supreme

Court of California, are not grounded in reality or logic—and

merely invite schools to adopt an approach we reject as u n

worthy and inappropriate, the institu tion of disingenuous

programs whereby race is taken into account covertly.

1. T he S p ec ia l A d m issio n s P rogram s

Responding to the moral pressures of the civil rights

movement, first led by this Court, which was sweeping the

country in the mid-1960s, the law schools began in a variety

of ways to take affirm ative steps to a tta in more than a token

enrollm ent of m inority students.15 There were, in 1964, only

700 black students in all the accredited law schools of the

c o u n try — 1.3% of th e to ta l e n ro llm e n t of m ore th a n

54,265—and 267 of them , more than a third, were enrolled in

w hat then were essentially segregated black schools.16 In all

of the other accredited schools in the country, then, fewer

than 200 were being adm itted each year. P lainly something

had to be done.

The first pa tte rn to emerge was an active program by the

law schools to recruit m inority, th a t is prim arily black, s tu

dents. Since the profession had historically been all bu t

closed to blacks, these students had first to be persuaded to

consider law as a career and then to enroll. Many methods of

recruiting were used. The Law School Admission Council

(LSAC) sponsored visits to black colleges and with black

15. The history given here can be traced in the voluminous reports pub

lished in Symposium, Disadvantaged Students and Legal Education—

Programs for Affirmative Action, 1970 Tol. L. Rev. 277.

16. Report of Minority Groups Project in AALS Proceedings 172(1965).

23

student groups; the LSAT was adm inistered to m inority s tu

dents w ithout charge; sum m er program s were held, first at

H arvard Law School in 1965, and then elsewhere, to give

college students an understanding of w hat law study m ight

involve; and scholarships were offered especially for m inor

ity applicants to overcome the financial hurdles th a t seemed

to dissuade so many.

Im plicit in these first program s to recru it and enroll

m inority students was the relaxation of admission standards

for them. For a t the same tim e th a t the law schools were

seeking to adm it increasing num bers of m inority students

they were also being deluged with increasing numbers of ap

plicants of all backgrounds. Law was becoming a more a t

tractive field to all sorts of students and, as previously de

scribed, the num ber of highly qualified, indeed exceptional

ly qualified, non-minority students was growing dispropor

tionately. Law schools, as a result, were seeking to increase

m inority student enrollm ent a t the same tim e th a t they

were first having to ration the ir available spaces by select

ing all students on an increasingly higher standard—and

unless something were done, it would he the m inority group

students once again who would be squeezed out.

A t most schools the solution was to return , in effect, to

w hat we have previously called the second stage in the de

velopment of the admissions process. (See p. 10, supra.) The

clock was, in effect, tu rned back for applicants from m inority

groups and all of those who were deemed to be qualified were

adm itted. T hat is to say, m inority students were adm itted

under these special admissions on the standards which had

been used by these very same schools in the late 1950s or

early 60s.

The schools accomplished th is in a variety of ways. In a

few, an explicit m inority admissions program was estab

lished. In others, it was disguised as a program for the disad-

24

vantaged. In still others, the action took place but no public

statem ent was made concerning the existence of differential

adm issions standards. In recent years, more and more

schools have identified the ir special admissions programs

publicly as they more fully understood the process and rea l

ized th a t no alternatives were available. Thus, by the mid

1970s, in v irtually all schools, in one way or another, a pref

erence in the application of admissions standards was in fact

afforded to applicants from m inority groups.

At the same tim e the law schools began adopting special

admissions program s, efforts were made to improve m inor

ity student preparation for law study, in sum m er studies be

fore law school and assistance program s while in school. The

preparatory program s had mixed results. H arvard’s pro

gram in 1965 and 1966 included a few college graduates, and

New York U niversity’s pre-law program in 1966 and 1967

sought to introduce students to the fundam entals of legal

study and to prepare them for the law school curriculum . At

the same tim e Emory Law School began a "pre-start” pro

gram whereby a dozen students from nearby black colleges

were recruited to take one regu lar law course in the sum m er

before the ir first year. If they passed, they were then adm it

ted to Emory as regu lar students except th a t they were on a

ligh ter course load during the ir first year. But programs

such as these were expensive. H arvard had to abandon its

program after being unable to obtain adequate funding in

1967 and New York U niversity concluded after two sum

mers th a t the results were so m eager as not to justify the

cost.

It was a t this point th a t the AALS, the LSAC and the na

tional bar associations, the Am erican B ar Association and

the N ational B ar Association, supported by the Office of

Economic Opportunity and the Ford Foundation, formed

w hat was called CLEO (the Council on Legal Education Op-

25

portunity) to provide sum m er tra in ing for disadvantaged

m inority pre-law students and to provide financial support

for these students once in law school. It began w ith four n a

tional institu tes in the sum m er of 1968 and has continued in

one form or another (now relying solely on congressionally

appropriated funds received through HEW) to the present

day.

Students adm itted are those who in general would not be

adm itted today to law school, even under special admissions

programs, w ithout an opportunity to pretest the ir ability to

do law school work in a sum m er institu te . T hat is, the ir nu

m erical credentials are such th a t under the elevated stan

dards forced by increased applicants, law schools generally

would tu rn down the applications of these m inority appli

cants because of low LSATs and GPAs. These sum m er in sti

tu tes are designed to be alternative predictors of success, and

the admission of these students into law school is generally

conditioned by the schools on the students’ successful com

pletion of a sum m er institu te . CLEO also has supported

these students during th e ir entire law school careers.

CLEO is only a partia l response, however. F irst it is costly

and could not be sustained w ithout governm ent support.

More im portant for this case is th a t it generally supports

students whose credentials are such th a t they could not be

adm itted in the schools in which they are enrolled even

using second-stage standards. Thus as a m atter of policy

CLEO does not support the most promising m inority s tu

dents on the theory th a t the law schools having special ad

missions programs will adm it these (more qualified) s tu

dents w ithout the aid of an expensive sum m er institu te’s ex

perience and th a t adequate financial assistance can be ob

tained for them from other funds. It is, in other words, a de

liberate federally-supported program to increase the pool of

m inority students attending law school beyond those who

would otherwise be adm itted in m inority admissions pro

grams.

At the in itia l stage these special admissions program s had

difficulties which we discuss la ter. Over time, however, the

fact th a t law was now open to m inorities th a t had heretofore

been alm ost totally excluded, plus the first effect of the im

provem ent in elem entary and secondary education resulting

from this Court’s decision inB row n, caused an im provem ent

in both the num ber and the quality of the applicants from

these groups. This has led to refinem ent of the programs.

Originally, the effort was to find and recru it m inim ally qual

ified m inority applicants. As the num ber and the qualifica

tions of m inority applicants increased, i t often became

necessary to put a ceiling on the num ber enrolled in them.

This "quota,” so called, is neither a lim it on the num ber of

m inority students to be adm itted nor, on the other hand, a

guarantee th a t a num ber equal to th is lim it will be adm itted

irrespective of qualification. I t is simply a lim it on the pro

portion of the school’s resources which will be devoted to the

program, sim ilar to the lim it which a school m ay put on the

num ber of nonresidents to be adm itted. The result, in either

case, is the existence of essentially two admissions processes,

each competitive w ithin itself and not competitive against

the other.

The premise of these special admissions programs is th a t,

in time, they will disappear. They are essentially a tra n

sitional device to correct a tim e lag. It would be naive to sup

pose th a t the cum ulative effects of centuries of deprivation

will be overcome in the space of a few years. But when the

need which brought the special admissions program s into

being disappears they will be term inated. It is to the schools’

in terest th a t this occur. Each is dedicated to atta in ing the

highest possible level of achievem ent in its student body.

Special admissions program s represent a compromise with

27

th a t goal, a compromise made necessary by the schools’ a l

most universal perception of a pressing societal need to

provide more m inority lawyers than can possibly be pro

duced w ithout them . But as the num ber of unrepresented

m inorities who can gain admission through the regu lar pro

cedures increases, the necessity for th a t compromise will

disappear.

An example, the only one we now know, is provided by the

elim ination of Japanese-A m ericans from the special adm is

sions program a t Boalt Hall, when th a t faculty found, after a

few years’ experience, th a t members of th a t group were gain

ing admission in substan tial num bers through the regular

procedure.17 The appropriate tim e for the eventual elim ina

tion of the program s, insofar as we can now determ ine it, is

still far in the fu ture for blacks and C-hicanos. The success of

the program s thus far, even w ith the ir m istakes, should not

obscure the fact th a t under today’s conditions the ir elim ina

tion would be a disaster. To th a t question we now turn.

2. M in ority S tu d en ts W ould B e A lm ost E lim in a ted

F rom L aw S ch o o l W ithout S p ec ia l A d m issio n s

P rogram s

The unpleasant bu t unalterab le reality is th a t affirmance

of the decision below would mean, for the law schools, a re

tu rn to the v irtually all-white student bodies th a t existed

prior to the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and subsequent congres

sional enactm ents which, after so many years of default, fi

nally committed the nation to the goal of racial equality.

More specifically, as a resu lt of the programs described in the

preceding pages, 1700 black and 500 Chicano students were

adm itted to the Fall, 1976 enteri ng class of the nation’s law

17. Report onSpecial Admissions at BoaltHall After Bakke, 28 J. Legal

Ed. 363 (1977).

28

schools.18 They represented 4.9% and 1.3%, respectively, of

the total of 43,000 who were adm itted .19 If the schools had

not taken race into account in m aking th e ir adm ission deci

sions, bu t had otherwise adhered to the admission criteria

they employ, the num ber of black students would have been

reduced to no more than 700 and the num ber of Chicanos to

no more th an 300.20 It is v irtually certain , however, th a t the

reduction would have been much g reater and it is not a t all

unlikely th a t even th is reduced num ber would have again

been reduced by half or more. Thus, the nation’s two largest

racial m inorities, representing nearly 14% of the population,

would have had a t most a 2.3% represen tatation in the n a

tion’s law schools and, more likely, no more th an about 1%.

These conclusions are draw n from F. Evans, Applications

and Adm issions to A B A Accredited Law Schools: A n A naly

sis o f National Data for the Class Entering in the Fall 1976

(LSAC 1977) (the Evans Report) which studied characteris

tics of applicants for admission to the 1976 law school class.

The length and complexity of th a t study preclude any effort

to set out its findings and supporting data in detail. We shall,

however, set forth briefly the data underlying the conclu

sions stated in the preceding paragraph and sum m arize sev

eral additional findings th a t fu rther dem onstrate the devas

ta ting impact th a t race-blind admission standards would

have upon m inority enrollm ent in law schools.

The ineradicable fact is th a t, as a group, m inorities in the

18. The difference in the numbers of minority students covered by the

Evans Report and the number actually enrolled is explained primarily by

the absence of LSD AS status data from the four predominantly black law

schools. See Evans Report at 39.

19. The total admitted, as reported in the Evans Report, exceeds the

actual 1976 law school first-year enrollment of 39,000 because some of

those accepted into law school nevertheless did not matriculate. Thus of

the 43,000 students admitted to at least one law school, approximately

4,000 did not enroll.

20. Evans Report at 44.

29

pool of law school applicants achieve dram atically lower

LSAT scores and GPAs th an whites. Illustratively, 20% of

the w hite and unidentified applicants, bu t only 1% of blacks

and 4% of Chicanos receive both an LSAT score of 600 or

above and a GPA of 3.25 or higher. Similarly, if the combined

LSAT/GPA levels are set a t 500 and 2.75 respectively, 60% of

the w hite and unidentified candidates would be included but