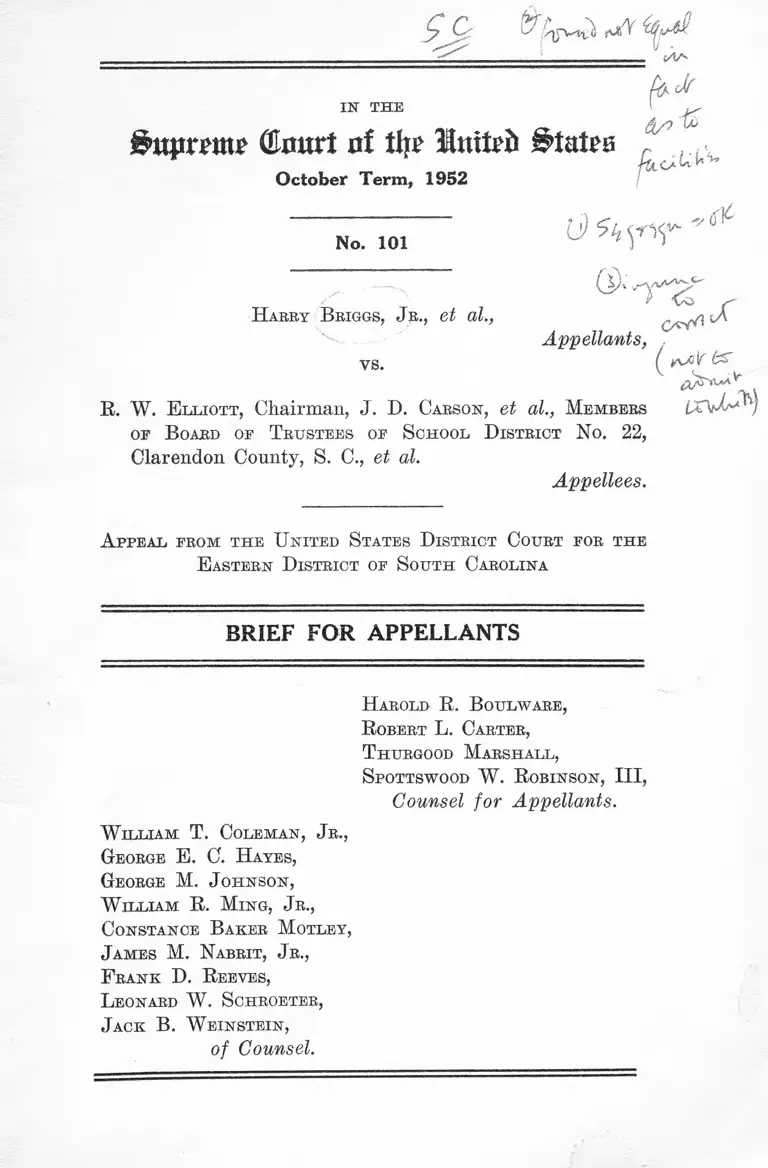

Briggs v. Elliot Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1952

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Briggs v. Elliot Brief for Appellants, 1952. 5f424a81-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1c3a1d13-f876-40e4-b52b-41b38e4b526a/briggs-v-elliot-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

59

iA/̂

IN THE

(&mvt of tfyp Itrifrib States

October Term, 1952

f a *

&/>X

ffa<^U5

No. 101

f 1 X-- y y f , 9

U 54 ^<,v- '

® : * r z

H arry B riggs, J r., et al., c ŷ*'"1

Appellants,

X

vs. j/%j0 V

<x^<v

E. W . Elliott, Chairman, J. I). Carson, et al., Members i x X * )

of B oard of Trustees of School D istrict No. 22,

Clarendon County, S. C., et al.

Appellees.

A ppeal from the U nited States D istrict Court for the

E astern D istrict of South Carolina

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Harold R. B oulware,

R obert L. Carter,

T hurgood Marshall,

Spottswood W. R obinson, III,

Counsel for Appellants.

W illiam T. Coleman, Jr.,

George E. C. H ayes,

George M. J ohnson,

W illiam R. Ming, Jr.,

Constance B aker M otley,

J ames M. Nabrit, J r.,

F rank D. R eeves,

Leonard W . Schroeter,

Jack B. W einstein,

of Counsel.

I N D E X

PAGE

Opinions ............................................................................ 1

Jurisdiction ....................................................................... 1

Statement of the Case ......................................... 2

The Constitutional Issue Involved ............................ 2

First Hearing ............................................................... 3

First Appeal ................................................................. 7

Second Hearing ........................................................... 7

Errors Relied U p on ......................................................... 9

Questions Presented ............................................. ......... 10

Constitution and Statute Involved................................ 10

Summary of Argument................................................... 11

Argument .......................................................................... 12

I. Legally Enforced Racial Segregation In The

Public Schools of South Carolina Denies The

Negro Children Of The State That Equality

of Educational Opportunity and Benefit

Required Under The Equal Protection Clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment ......................... 12

II. The Compulsory Segregation Laws of South

Carolina Infect Its Public Schools With

That Racism Which This Court Has Re

peatedly Declared Unconstitutional In Other

Areas of Governmental A ction ......................... 21

III. Neither The Decision in Plessy v. Ferguson

Nor the Decision In Gong Lum v. Rice Are

Applicable To This C ase .................................. 26

IV. The Equalization Decree Does Not Grant

Effective Relief and Cannot Be Effectively

Enforced Without Involving the Court In the

Daily Operation of the Public Schools.......... 28

Conclusion ........................................................................ 31

11

Air-Way Electric Appliance Co. v. Day 266 U. S. 71. 23

Armour & Co. v. Dallas, 255 U. S. 280...................... 30

Beasley v. Texas & Pac. By. Co., 191 U. S. 492............. 30

Belton et al. v. Gebhart et al.,—Del. —decided Aug. 28,

1952 ................................................................................ 29

Bd. of Supervisors v. Wilson, 340 U. S. 909 ................. 23

Brown v. Bd. of Education, Oct. Term, 1952, No. 8___ 20

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 6 0 ................................ 21

Carr v. Corning, 182 F. 2d 14, 22, 31 (C. A. D. C. 1950). 30

City of Birmingham v. Monk, 185 F. 2d 859 (C. A. 5th

1951) cert. den. 341 U. S. 942...................................... 21

Concordia Fire Ins. Co. v. Hill, 292 U. S. 535 ............. 23

Edwards v. California, 314 U. S. 160.............................. 23

Ex parte Endo, 323 U. S. 283 ........................................ 22

Fisher v. Hurst, 333 U. S. 147...................................... 28

Flood v. Evening Post Publishing Co., 71 S. C. 122, 50

S, E. 641 (1905) ........................................................... 24

Flood v. News and Courier Co., 71 S. C. 112, 50 S. E.

637 (1905) ................................................................. 24

Gong Lum v. Bice, 275 U. S. 78................................ 26, 27, 28

Hale v. Kentucky, 303 U. S. 613................................... 23

Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection & Ins. Co. v. Harri

son, 301 U. S. 459 ....................................................... 23

Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U. S. 81................. 22

Javierre v. Central Altagracia, 217 U. S. 502............. 30

Jones v. Better Business Bureau, 123 F 2d 767, 769

(C. A. 10th 1941) ......................................................... 15

Korematsu v. United States, 323 U. S. 214..................... 22

Table o f Cases Cited

PAGE

I l l

PAGE

McLaurin v. Board of Regents, 339 U. S. 637.. 12,13, 20, 21,

23, 26, 28, 29

Mayflower Farms v. Ten Eyck, 297 U. S. 266............... 23

Missouri ex rel Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337 .. 23, 28, 29

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 IT. S. 373 .................................. 23

Nixon y. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536....................................23, 24

Oyana v. California, 332 TJ. S. 633................................ 22, 23

Paton v. Mississippi, 332 U. S. 463................. ............. 23

Pierre v. Louisiana, 306 TJ. S. 354.................................. 23

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537 ......................... 26, 27, 28

Rutland Marble Co. v. Ripley, 10 Wall. 339 ................. 30

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 TJ. S. 1 .................................... 22

Shepherd v. Florida, 341 TJ. S. 50.................................... 23

Sipuel v. Bd. of Regents, 332 TJ. S. 631 ............. 23, 28, 29

Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 TJ. S. 535.............................. 22, 23

Southern Railway Co. v. Greene, 216 TJ. S. 400............. 23

Steele v. Louisville & N. R. Co. 323 TJ. S. 1 9 2 ............. 22

Stokes v. Gt. A. and P. Tea Co., 202 S. C. 24, 23 S. E.

2d 823 (1943) ................................................... ........... 24

Sweat! v. Painter, 339 TJ. S. 629 . .12,13, 20, 23, 26, 27, 28, 29

Takahashi v. Fish and Game Commission, 334 TJ. S. 410

22, 23

Truax v. Raich, 239 U. S. 3 3 ............................................ 23

Texas & Pac. Ry Co. v. City of Marshall, 136 TJ. S. 393. 30

United States v. Cong, of Industrial Org., 335 U. S. 106. 22

United States v. Paramount Pictures, Inc., 334 U. S. 131 30

Weyl v. Comm, of Int. Rev., 48 F(2d) 811, 812 (CA 2d)

1931) .............................................................................. 15

IV

American Teachers Assn., The Black d White of Re

jection for Military Service (1944) ........................... 25

Clark, Negro Children, Educational Research Bulletin

(1923) ....................................... 25

Dollard, Caste and Class in a Southern Town (1937) .. 24

Johnson, Patterns of Negro Segregation (1943)......... 24

Klineberg, Race Differences (1935) ............................... 25

Klineberg, Negro Intelligence and Selective Migration

(1935) ............................................................................ 25

Montague, Man’s Most Dangerous Myth—The Fallacy

of Race (1945) ............................................................... 25

Myrdal, An American Dilemma (1944) ........................... 24

Peterson and Lanier, Studies in the Comparative Ab

ilities of Whites and Negroes, Mental Measurement

Monograph (1929) ....................................................... 25

Rose, America Divided: Minority Group Relations In

the United States (1948) .............................................. 25

Notes

39 Col. L. Rev. 986 (1939) .............................................. 24

49 Col. L. Rev. 629 (1939) .............................................. 24

56 Yale L. J. 1059 (1947) ................................................ 24

Authorities Cited

PAGE

PAGE

Title 28, United States Code,

sections 1253, 2101 (b) ........................................... 2

sections 2281, 2284 .................................................. 3

Article XI, section 7, Constitution of South Carolina 2, 8,10

section 5 ............................................................ 14

Code of Laws of South Carolina (1942)

section 5377 ......................................................... 2, 8,10

South Carolina Code (1935) Title 31, Chapter 122

sections 5321, 5323, 5325 .................................... 14,15

Statutes Cited

IN THE

(Urntrt of tin Itutefo States

October Term, 1952

No. 101

----- --------------o------------------

Harry B riggs, J e., et al.,

vs,

Appellants,

R. W. E lliott, Chairman, J. D. Carson, et al., Members

o f B oard of T rustees of School D istrict No. 22,

Clarendon Comity, S. C., et al.

Appellees.

A ppeal from the U nited States D istrict Court for the

E astern D istrict of South Carolina

-------------------—-o----------------------

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Opinions

The majority and dissenting opinions filed at the con

clusion of the first hearing are reported in 98 F. Supp.

529-548 and appear in the record (R. 176-209). The opinion

filed at the conclusion of the second hearing is reported in

103 F. Supp. 920-923 and appears in the record (R. 301-306).

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the statutory three-judge District

Court was entered on March 13, 1952 (R. 306). A petition

for appeal was presented to the district court and allowed

on May 10, 1952 (R. 309). Probable jurisdiction was noted

by this Court on June 9, 1952 (R. 316).

2

This is an appeal from an order denying an injunction

in a civil action required by an act of Congress to be heard

and determined by a district court of three judges. The

jurisdiction of the Supreme Court to review this decision

by direct appeal is conferred by Title 28, United States

Code, Sections 1253 and 2101(b).

Statement of the Case

The Constitutional Issue Involved

The complaint in this ease was filed by Negro children

of public school age residing in School District No. 22,

Clarendon Countv. South Carolina, and their respective

parents and’ guardians, against the public school officials of

said county and school district who, as officers of the State,

maintain, operate and control the public schools for children

residing in said district. It was alleged that appellees

maintained certain public schools for the exclusive use of

white children and certain other public schools for Negro

children; that the schools for Negro children were in all

respects inferior to the schools for white children; that the

appellees excluded the infant appellants from the white

schools pursuant to Article XI, section 7, of the Constitu

tion of South Carolina, and section 5377 of the Code of

Laws of South Carolina of 1942, which require the segre

gation of the races in public schools; and that it was

impossible for the infant appellants to obtain a public

school education equal to that afforded and available to

white children as long as the appellees enforced these laws.

The complaint sought a judgment declaring the inva

lidity of these laws as a denial of the equal protection of

the laws secured by the Fourteenth Amendment of the

Constitution of the United States, and an injunction re

straining the appellees from enforcing them and from

making any distinctions based upon race or color in

3

the educational opportunities, facilities and advantages

afforded public school children residing in said district.

Appellees in their answer joined issue on this question

and admitted that in obedience to the constitutional and

statutory mandates separate schools were provided for the

children of the white and colored races; and that no child

of either race was permitted to attend a school provided

for children of the other race. In the Third Defense of

Appellees’ Answer they alleged that the above constitu

tional and statutory provisions were a valid exercise of

the State’s legislative power.

The jurisdiction of a three-judge District Court was

invoked pursuant to Title 28, United States Code, Sections

2281, 2284, for the purpose of determining the validity of

the provisions of the Constitution and laws of South

Carolina requiring segregation of the races in public!

schools. This issue was clearly raised, and was decided by

upholding the validity of these provisions and by refusing

to enjoin their enforcement.

First Hearing

At the opening of the trial (before a three-judge Dis

trict Court as required by Title 28, United States Code,

sections 2281 and 2284) appellees admitted upon the record

that “ the educational facilities, equipment, curricula and

opportunitieTafforded in School District No. 22 for colored

pupils * * * are not substantially equal to those afforded

in the District for white pupils.” The appellees also stated

that they did “ not opposean order finding, that inequalities

in respect to buricErig^erpiipnieiit, facilities, curricula, and

other aspects of the schools provided for the white and

colored children of School District No. 22, in Clarendon

County now exist, and enjoining any discrimination in

respect thereto.”

These admissions were made part of the record by

being filed as an amendment to the answer. The only issue

4

remaining to be tried was the question of the constitution

ality of the lawgrequiring segregation of the races in public

education as applied to the appellants.

During the trial the appellants produced testimony

showing the extent of the physical inequality in the segre

gated schools of Clarendon County and especially School

District No. 22. Over the objection of the appellants1

the appellees introduced testimony that a three per cent

sales tax and authorization of a $75,000,000 bond issue for

improvement of schools had recently been adopted by the

State of South Carolina, and that the State Educational

Finance Commission had just been organized to supervise

the distribution of these funds and had not even set up

rules or procedures.2 About a week before the trial

Clarendon County had “ inquired” about making an ap

plication for funds.

The testimony of nine expert witnesses was introduced

by appellants; two experts in the field of education who

offered a comparison of the public schools; one expert in

educational psychology, three experts in the respective

fields of child and social psychology, one expert in political

science, one expert in school administration, and one expert

in the field of anthropology.

The uncontroverted testimony of these witnesses demon

strated that the Negro schools in question were inferior

in every material aspect to the white schools, and that

similarly the caliber of education offered to Negro pupils

was inferior to that offered to white pupils. The testimony

of these witnesses also established the fact that the segrega

tion of Negro pupils in these schools would in and of itself

1 On the grounds that equality within the meaning of the Four

teenth Amendment did not include contemplated future action

(R. 108).

2 It was admitted that although the school population of South

Carolina was approximately forty to forty-five per cent Negro there

were no Negroes on the Commission and no Negro employees of

the Commission (R. 114).

5

preclude them from receiving educational benefits equal

to those offered to white pupils or pupils in a non-segregated

school. These witnesses not only established their qualifica

tions in their respective fields but also supported their

conclusions by objective and scientific authorities.

One of the experts in the field of child and social

psychology testified that he had made special studies of

the recognized methods of testing the effects of racial

prejudice and segregation on children. He used a test

of this type on Negro school children including the infant

appellants in School District No. 22 a few days before

the trial. From his general experience in this field and the

results of his tests he testified:

“ A. The conclusion which I was forced to reach

was that these children in Clarendon County, like

other human beings who are subjected to an obviously

inferior status in the society in which they live, have

been definitely harmed in the development of their

personalities; that the signs of instability in their

personalities are clear, and I think that every

psychologist would accept and interpret these signs

as such.

“ Q. Is that the type of injury which in your

opinion would be enduring or lasting? A. I think

it is the kind of injury which would be as enduring

or lasting as the situation endured, changing only

in its form and in the way it manifests itself” (B.

89-90).

These witnesses testified as to the unreasonableness of

segregation in public education and the lack of any scientific

basis for such segregation and exclusion. They testified

that all scientists agreed that there are no fundamental

biological differences between white and Negro school pupils

which would justify segregation. An expert in anthropology

testified:

6

“ The conclusion, then to which I come, is differ

ences in intellectual capacity or inability to learn

have not been shown to exist as between Negroes and

whites, and further, that the results make it very

probable that if such differences are later shown to

exist, they will not prove to be significant for any

educational policy or practice” (R. 161).

Another expert witness testified:

“ It is my opinion that except in rare cases, a

child who has for 10 or 12 years lived in a community

where legal segregation is practiced, furthermore, in

a community where other beliefs and attitudes sup

port racial discrimination, it is my belief that such

a child will probably never recover from whatever

harmful effect racial prejudice and discrimination

can wreck” (R. 134).

The appellees did not produce a single expert to contra

dict these witnesses. There were only two witnesses for

the appellees. The Superintendent of Schools for District

No. 22 testified as to the reasons for the physical inequalities

between the white and Negro schools. The Director of the

Educational Finance Commission testified as to the pro

posed operation of the Commission and the possibility

of the appellees obtaining funds to improve public schools.

The latter witness testified that from his experience as a

school administrator in Sumter and Columbia, South

Carolina, it would be “ unwise” to remove segregation in

public schools in South Carolina. On cross-examination,

he admitted he had not made any formal study of racial

tensions but based his conclusion on the fact that he had

“ observed conditions and people in South Carolina” all

of his life. He also admitted that his conclusion was based

in part on the fact that all of his life he had believed in

segregation of the races.

7

The judgment on this hearing, one judge dissenting

stated that neither the constitutional nor statutory pro

visions requiring segregation in public schools were in

violation of the Fourteenth Amendment and that appellants

were not entitled to an injunction against the enforcement

of these provisions by these appellees. The judgment also

stated that the educational facilities offered infant appel

lants were unequal to those offered to white pupils, and

ordered the_appellees “ to furnish to appellants and other

Negro pupils of said district educational facilities, equip

ment, curricula and opportunities'lqual to those furnished

white pupils.”

First Appeal

An appeal from this judgment was allowed on July

20, 1951 and the appellees filed a motion to dismiss or

affirm. On December 21, 1951 appellees filed their report

in the District Court showing progress being made toward

equalization of physical facilities in the public schools of

Clarendon County. A copy of this report was forwarded

to this Court. On January 28—L952. this Court, vacated

the judgment of the District Court and remanded the

case to that court in order to obtain the views of the trial

court upon the additional facts in the record and to give

the District Court an opportunity to take whatever action

it might deem appropriate in light of the report (342 U. S.

350). Mr. Justice Black and Mr. Justice Douglas dissented

on the ground that the additional facts in the report were

“ wholly irrelevant to the constitutional questions presented

by the appeal to this court” (342 U. S. 350).

Second Hearing

As soon as the mandate reached the District Court,

appellants filed a Motion for Judgment requesting an early

hearing and a final judgment granting the relief as prayed

for in the complaint. Among the reasons for this motion

appellants alleged:

8

“ It is, therefore, clear that plaintiff’s rights

guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment are being

violated and remain unprotected. The injury is

irreparable. The only available relief is by injunc

tion against the continued denial of their right to

equality which is brought about by compulsory

racial segregation required by the Constitution and

laws of South Carolina. (So. Car. Const. Art. XI,

Sec. 7: S. C. Code, 1942, Sec. 5377.)

“ Plaintiffs can get no immediate relief except

by the issuance of a final judgment of this Court

enjoining the enforcement of the policy of racial

segregation by defendants which excludes Negro

pupils from the only schools where they can obtain

an education equal to that offered white children.

“ Plaintiffs can get no permanent relief unless

this Court declares that the provisions of the Con

stitution and laws of South Carolina requiring racial

segregation in public schools are unconstitutional

insofar as they are enforced by the defendants

herein to exclude Negro pupils from the only schools

where they can obtain an education equal to that

offered white children” (E. 258),

It appearing that School District No. 22 of Clarendon

County had been combined with six other school districts

into a single school district the district court made the

appellees parties in their present capacities as officials of

School District No. 1 (R. 262-263; 306).

The second hearing was held on March 3, 1952, at which

time the appellees filed an additional report showing

progress since the December report. The appellants did

not question the accuracy of these statements of physical

changes in the making.

9

At the second hearing the District Court ruled that the

question of the decision on the validity of segregation

■statutes was closed by the original judgment and could not

be argued at that hearing. The District Court also refused

to rule that, aside from the question of the validity of these

statutes, the admitted lack of equality of facilities entitled

appellants to an injunction restraining appellees from ex

cluding them from an opportunity to share the superior

schools and the inferior schools on an equal basis without

regard to race and color.

On March 13, 1952, the District Court filed an opinion

and a decree again finding that the educational facilities

for Negroes were not substantially equal to those afforded

white pupils. Despite this finding the District Court held

that “ plaintiffs are not entitled to an injunction forbidding

segregation in the public schools of School District No. 1” .

Errors Relied Upon

The District Court erred:

I

In refusing to enjoin the enforcement of the laws of

South Carolina requiring racial segregation in the public

schools of Clarendon County on the ground that these

laws violate rights secured under the equal protection

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

II

In refusing to grant to appellants immediate and effec

tive relief against the unconstitutional practice of excluding

appellants from an opportunity to share the public school

facilities of Clarendon County on an equal basis with other

students without regard to race or color.

III

In predicating its decision on the doctrine of Plessy v.

Ferguson and in disregarding the rationale of Sweatt v.

Painter and McLaurin v. Board of Regents.

10

Questions Presented

I

Whether legally enforced racial segregation in the

public schools of South Carolina denies the Negro chil

dren of the state that equality of educational opportunity

and benefit required under the equal protection clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment.

II

Whether the compulsory segregation laws of South

Carolina infect its public schools with that racism which

this Court has repeatedly declared unconstitutional in other

areas of governmental action.

III

Whether the decision in Plessy v. Ferguson or the deci

sion in Gong Lum v. Bice are applicable to this case.

IV

Whether the equalisation decree in this case grants

effective relief and can be effectively enforced without in

volving the District Court in supervising the daily opera

tion of the public schools.

Constitution and Statute Involved

Article XI, section 7 of the Constitution of South

Carolina provides:

“ Separate schools shall be provided for children

of the white and colored races, and no child of either

race shall ever be permitted to attend a school pro

vided for children of the other race.”

Section 5377 of the Code of Laws of South Carolina is

as follows:

“ It shall be unlawful for pupils of one race to

attend the schools provided by boards of trustees

for persons of another race.”

11

Summary of Argument

Although the decisions in the case of Sweatt v. Painter

and McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents involved state

afforded education on the graduate and professional level,

the underlying principles of these decisions are applicable

and controlling in this case involving public education on

the elementary and high school level.

Applying these principles, the basic question in the in

stant case is: “ To what extent does the equal protection

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment limit the power of a

state to distinguish between students of different races ’ ’ in

the educational benefits afforded on the elementary and

high school level of public education. Further, the equality

or inequality of physical facilities are not decisive of this

question. Consideration must be given not only to the

measurable physical facilities but to all of the factors which

have educational significance. Finally, if it appears from

the record, as it does in this case, that segregation is a

major handicap to the segregated pupils, then the state

laws requiring this segregation violate the equal protec

tion clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The laws here challenged are likewise unconstitutional

under a uniform line of decisions of this Court striking

down governmental classifications based solely on race or

ancestry. The laws of South Carolina segregate Negro

public school pupils from other public school pupils solely

because of race or color. Such a classification based on race

alone cannot be justified as a classification based upon any

real difference which has pertinence to a valid legislative

objective.

The District Court was in error in rejecting the basic

principles set forth in the Sweatt and McLaurin decisions

as being inapplicable to the instant case despite the uncon

troverted expert testimony showing the injury to the seg

regated Negro children on the public elementary and high

school level. Neither the case of Plessy v. Ferguson nor

the case of Gong Lum v. Rice relied on by the majority of

12

the District Court are decisive of the issues in this case.

The final order of the District Court in upholding the segre

gation laws of the State of South Carolina cannot bring

about the equality of educational benefits required.

ARGUMENT

I

Legally enforced racial segregation in the public

schools of South Carolina denies the Negro children

of the State that equality of educational opportunity

and benefit required under the equal protection clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment.

In its recent opinions on the constitutionality of racially

segregated public education, this Court has refused, on the

one hand, to give blanket sanction to such state racism, but

refrained on the other hand, from formulating a general

rule that all forms of governmentally imposed segregation

offend the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment. Without saying that such racial segregation

is per se valid or per se invalid this Court has tested each

complaint against segregated education in terms of whether

or not—taking into account the nature, purpose and cir

cumstances of the educational program—the segregated

person or group is in some real and significant sense de

nied educational benefits available to the rest of the com

munity.

In two recent cases, Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629 and

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U. S. 637, this

Court considered the question: “ to what extent does the

equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment limit

the power of a state to distinguish between students of dif

ferent races in professional and graduate education in a

state university?” (339 U. S. 629, 631).

In neither case were physical inequalities decisive of the

issue. In the Sweatt case, there were quantitative differ

ences between the white and Negro law schools with respect

13

to such matters as the number of faculty members, the size

of the libraries and the scope of the curricula. This Court,

however, laid stress upon those “ more important” factors

which are “ incapable of objective measurement” —factors

such as the relative reputation of the faculties, the relative

experience of the school administration, the relative status

and influence in the community of the alumni, and the rela

tive ease with which the two student groups could associate

with fellow students and with their future professional

colleagues. This Court concluded that Sweatt was entitled

to claim his “ full constitutional right” to a legal educa

tion equivalent in all respects to that offered by the state

to students of other races and that such education was not

available to him in a separate law school.

In the McLaurin case, there was no question of in

equality insofar as buildings, faculties or curricula were

concerned because McLaurin was actually in the same

classroom with the other students. The only issue in that

case was whether the enforced racial segregation of Mc

Laurin inherent in his being seated apart from the other

students denied to him educational benefits equivalent to

those offered other students. This Court held that it did.

Although the Sweatt and McLaurin cases arose in the

field of higher education, the constitutional issue is the

same at every level of public education: Does state-imposed

segregation destroy equality of educational benefitsf

The Sweatt and McLaurin cases teach not only that this

is the issue which must be resolved in every case presented

for judicial review, but also that in seeking the answer the

Court will consider the educational process in its entirety,

including, apart from the measurable physical facilities,

whatever factors have been shown to have educational sig

nificance. And where the record shows that segregation

is a major handicap to education, the Court will hold that

the difference in treatment is the type of state-imposed

inequality which is prohibited by the equal protection clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment.

14

Any other conclusion would be inconsistent with the

rule recognized in the Sweatt and McLaurin cases that

where the state-imposed racial restrictions impair the

ability of the segregated student to secure an equal edu

cation because of the denial of any kind of educational bene

fits available to other students, the aggrieved student may

invoke the protection afforded by the equal protection

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to enjoin the main

tenance of state-imposed barriers to a racially integrated

school environment.

This rule cannot he peculiar to any level of public edu

cation. Public elementary and high school education is no

less a governmental function than graduate and profes

sional education in state institutions. Moreover, just as

Sweatt and McLaurin were denied certain benefits charac

teristic of graduate and professional education, it is appar

ent from this record that appellants are denied educational

benefits which the state itself asserts are the fundamental

objectives of public elementary and high school education.

South Carolina, like the other states in this country,

has accepted the obligation of furnishing the extensive

benefits of public education. Article XI, section 5, of the

Constitution of South Carolina, declares: “ The General

Assembly shall provide for a liberal system of free public

schools for all children between the ages of six and twenty-

one years. ’ ’ Some 410 pages of the Code of Laws of South

Carolina deal with “ education” . Title 31, Chapters 122-23,

S. C. Code, pp. 387-795 (1935). Provision is made for

the entire state-supported system of public schools, its

administration and organization, from the kindergarten

through the university. Pupils and teachers, school build

ings, minimum standards of school construction, and speci

fications requiring certain general courses of instruction

are dealt with in detail. In addition to requiring that the

three “ B ’s ” must be taught, the law compels instruction

in “ morals and good behaviour” and in the “ principles”

and “ essentials of the United States Constitution, including

15

the study of and devotion to American institutions.” Title

31, Chapter 122, sections 5321, 5323, 5325, S. C. Code (1935).

South Carolina thus recognizes the accepted broad pur

poses of general public education in a democratic society.

There is no question that furnishing public education is

now an accepted governmental function. There are com

pelling reasons for a democratic government’s assuming

the burden of educating its children, of increasing its citi

zens’ usefulness, efficiency and ability to govern.

In a democracy citizens from every group, no matter

what their social or economic status or their religious or

ethnic origins, are expected to participate widely in the

making of important public decisions. The public school,

even more than the family, the church, business institutions,

political and social groups and other institutions, has be

come an effective agency for giving to all people that broad

background of attitudes and skills required to enable them

to function effectively as participants in a democracy.

Thus, “ education” comprehends the entire process of de

veloping and training the mental, physical and moral pow

ers and capabilities of human beings. Weyl v. Comm, of

Int. Rev., 48 F. 2d 811, 812 (0. A. 2d 1931); Jones v.

Better Business Bureau, 123 F. 2d 767, 769 (C. A. 10

1941 ).J

The record in this case emphasizes the extent to which

the state has deprived the appellants of these fundamental

educational benefits by separating them from the rest of

the school population.

Expert witnesses testified that compulsory racial segre

gation in elementary and high schools inflicts considerable

personal injury on the Negro pupils which endures as long

1 See: Brief of Committee of Law Teachers Against Segregation

in Legal Education filed in Sweatt v. Painter, No. 44, October Term,

1949, pp. 36-38.

16

as these students remain in the segregated school. These

witnesses testified that compulsory racial segregation in

the public schools of South Carolina injures the Negro

students by: (1) impairing their ability to learn (R. 140,

161); (2) deterring the development of their personalities

(R. 86, 89); (3) depriving them of equal status in the school

community (R. 89, 141, 145); (4) destroying their self-

respect (R. 140, 148); (5) denying them full opportunity

for democratic social development (R. 98, 99, 103); (6)

subjecting them to the prejudices of others (R. 133) and

stamping them with a badge of inferiority (R. 148).

Dr. Kenneth Clark, an expert in the fields of social and

child psychology who tested the infant plaintiffs and other

Negro school children in District No. 22, testified:

“ A. The conclusion which I was forced to reach

was that these children in Clarendon County, like

other human beings who are subjected to an obviously

inferior status in the society in which they live,

have been definitely harmed in the development of

their personalities; that the signs of instability in

their personalities are clear, and I think that every

psychologist would accept and interpret these signs

as such.

“ Q. Is that the type of injury which in your

opinion would be enduring or lasting! A. I think

it is the kind of injury which would be as enduring

or lasting as the situation endured, changing only

in its form and in the way it manifests itself” (R.

89-90).

Dr. David Krech, another psychologist, testified:

“ * Legal segregation, because it is legal,

because it is obvious to everyone, gives what we

call in our lingo environmental support for the belief

that Negroes are in some way different from and

17

inferior to white people, and that in turn, of course,

supports and strengthens beliefs of racial differences,

of racial inferiority. I would say that legal segrega

tion is both an effect, a consequence of racial pre

judice, and in turn a cause of continued racial pre

judice, and insofar as racial prejudice has these

harmful effects on the personality of the individuals,

on his ability to earn a livelihood, even on his ability

to receive adequate medical attention, I look at

legal segregation as an extremely important con

tributing factor. May I add one more point. Legal

segregation of the educational system starts this

process of differentiating the Negro from the white

at a most crucial age. Children, when they are

beginning to form their views of the world, begin

ning to form their perceptions of people, at that very

crucial age they are immediately put into the situa

tion which demands of them, legally, practically,

that they see Negroes as somehow of a different

group, different being, than whites. For these

reasons and many others, I base my statement.

“ Q. These injuries that you say come from legal

segregation, does the child grow out of them? Do

you think they will be enduring, or is it merely a

sort of temporary thing that he can shake off? A.

It is my opinion that except in rare cases, a child

who has for 10 or 12 years lived in a community

where legal segregation is practiced, furthermore, in

a community where other beliefs and attitudes sup

port racial discrimination, it is my belief that such

a child will probably never recover from whatever

harmful effect racial prejudice and discrimination

can wreak” (R. 133-134).

Dr. Harold McNalley, an expert in the field of Educational

Psychology, testified:

18

“ * * * And, secondly, that there is basically implied

in the separation—the two groups in this case of

Negro and White—that there is some difference in

the two groups which does not make it feasible for

them to be educated together, which I would hold

to be untrue. Furthermore, by separating the two

groups, there is implied a stigma on at least one

of them. And, I think that that would probably be

pretty generally conceded. We thereby relegate

one group to the status of more or less second-class

citizens. Now, it seems to me that if that is true—

and I believe it is—that it would be impossible to

provide equal facilities as long as one legally accepts

them.

“ Q. I see. Now, all of the items that you talked

about that you based your reason for reaching your

conclusion, you consider them to be important phases

in the educational process? A. Very much so” (R.

74).

Dr. Louis Kesselman, a political scientist, testified:

“ I think that I do. My particular interest in

the field of Political Science is citizenship and the

Political process. And, based upon studies which

we regard as being scientifically accurate by virtue

of use of the scientific methods, we have come to feel

that a number of things result from segregation

which are not desirable from the standpoint of good

citizenship; that the segregation of white and Negro

students in the schools prevents them from gaining

an understanding of the needs and interests of both

groups. Secondly, segregation breeds suspicion and

distrust in the absence of a knowledge of the other

group. And, thirdly, where segregation is enforced

by law, it may even breed distrust to the point of

conflict. Now, carrying that over into the field of

19

citizenship, when a community is faced with problems

which every community would be faced with, it will

need the combined efforts of all citizens to solve

those problems. Where segregation exists as a

pattern in education, it makes that cooperation more

difficult. Next, in terms of voting and participating

in the electorial process, our various studies indicate

that those people who are low in literacy and low

in experience with other groups are not likely to

participate as fully as those who have * * * ” (R.

103-104).

Mrs. Helen Trager, a child psychologist who had conducted

tests of the effects of racial segregation and racial tensions

among children, testified:

“ Q. Mrs. Trager, in your opinion, could these

injuries under any circumstances ever be corrected

in a segregated school? A. I think not, for the

same reasons that Dr. Krech gave. Segregation is a

symbol of, a perpetuator of, prejudice. It also

stigmatizes children who are forced to go there.

The forced separation has an effect on personality

and one’s evaluation of one’s self, which is inter

related to one’s evaluation of one’s group” (R. 148).

Dr. Robert Redfield, an expert in the field of anthropology,

testified as to the unreasonableness of racial classification

in education:

‘ ‘ Q. As a result of your studies that you have

made, the training that you have had in your special

ized field over some 20 years, given a similar learn

ing situation, what, if any difference, is there between

the accomplishment of a white and a Negro student,

given a similar learning situation ? A. I understand,

if I may say so, a similar learning situation to include

a similar degree of preparation?

20

“ Q. Yes. A. Then I would say that my con

clusion is that the one does as well as the other on

the average” (R. 161).

The testimony on behalf of the appellants was by ex

pert witnesses of unimpeachable qualifications. The record

in this case presented for the-fi^t-time in any case com

petent testimony of the permanent injury to Negro ele

mentary and high school children forced to attend segre

gated schools. Testimony was introduced showing the

irreparable damage done to the appellants in this case

solely by reason of racial segregation. The record also

shows the unreasonableness of this racial classification.

This evidence stands uncontradicted in the record.

On the basis of like testimony in a similar case another

■’ ! District Court made a finding of fact that segregatmrf in

j j public schooKYetardrerTthe mental and educational develop

ment of the colored children and was generally interpreted

as denoting the inferiority of the Negro group. Brown v.

Board of Education, October Term, 1952, No. 8.

The application of the rationale of the Sweatt and

McLaurin cases to the record in the instant case requires

the conclusion: “ that the conditions under which this ap

pellant is required to receive his education deprive him of

his personal and present right to the equal protection of

the laws. See: Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629, ante. We

hold that under these circumstances the Fourteenth Amend

ment precludes differences in treatment by the state based

upon race.” (McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339

U. S. 637, 642).

21

II

The compulsory segregation laws of South Caro

lina infect its public schools with that racism which

this Court has repeatedly declared unconstitutional in

other areas of governmental action.

The issue of the validity of the laws of South Carolina

requiring racial segregation in public schools was clearly

joined in the pleadings in this case and has been preserved.

The District Court has twice decreed that these laws are

valid and has twice refused to enjoin their enforcement.

These laws require that all Negro pupils attend schools

segregated for their use and prohibit them from attending

other schools in which pupils of all other racial groups are

educated as a matter of course. The clear vice is that the

segregated class is defined wholly in terms of race or color—

‘ ‘ simply that and nothing more. ’ ’ Buchanan v. Warley, 245

U. S. 60, 73.

At the trial of the instant case the State made no effort

to justify these provisions of its laws except by statements

of one witness to the effect that it would be “ unwise” to

adopt a policy of non-segregation (E. 113). The basis for

this belief was that there was a feeling of “ separteness

between the races in South Carolina.” The witness also

testified that there would probably be a “ violent emotional

reaction” to non-segregation (B. 113-114). Neither of

these theories justify the deprivation of constitutional

rights. Buchanan v. Warley, supra; McLaurin v. Oklahoma

State Regents, supra; City of Birmingham v. Monk, 185 F.

2d 859 (C. A. 5th 1951), cert. den. 341 U. S. 940. The Dis

trict Court, however, concluded that segregation of the

races in public schools “ so long as equality of rights is

preserved, is a matter of legislative policy for the several

states, with which the federal courts are powerless to inter

fere” (E. 179).

22

The laws here involved, like all others which curtail

a civil right on a racial basis, are “ immediately suspect”

and will be subjected to “ the most rigid scrutiny.” Kore-

matsu v. United States, 323 TJ. S. 214, 216.2

In South Carolina the school which a child is permitted

to attend depends solely upon his race or color. This Court

has declared that insofar as the federal government is

concerned “ distinctions between citizens solely because of

their ancestry are by their very nature odious to a free

people whose institutions are founded upon the doctrine

of equality.” Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U. S. 81,

100. The Court reached this conclusion by adopting the

reasoning of its prior decisions that similar state imposed

classifications and discrimination violated the equal pro

tection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. See also:

Korematsu v. United States, supra. This Court, however,

recognized that insofar as the federal government is con

cerned its constitutionally conferred right to wage war

could temporarily override this civil right. Cf. Ex parte

Endo, 323 IT. S. 283. No state can show either constitu

tional authorization or any such overriding necessity which

would warrant sustaining state action founded upon these

constitutionally irrelevant and arbitrary considerations.

See: Oyama x. California, 332 U. S. 633; Takahashi v. Fish

and Game Commission, 334 IT. S. 410 ; Shelley v. Kraemer,

334 IT. S. 1.

During the past quarter century this Court has con

sistently held that the Fourteenth Amendment invalidated

specific state imposed racial distinctions and restrictions

in widely separated areas of human endeavor: ownership

and occupancy or real property, Shelley v. Kraemer, supra;

2 See also: Ex parte Endo, 323 U. S. 283, 299; United States v.

Congress of Industrial Organizations, 335 U. S. 106, 140, concur

ring opinion; Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U. S. 535, 544, concurring

opinion; Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U. S. 81, 100; Idem, at

110, concuring opinion; Steele v. Louisville & N. R. Co., 323 U. S.

192, 209.

23

Oyama v. California, supra; pursuit of gainful employment

or occupation, Takahashi v. Fish and Game Commission,

supra; selection of juries, Shepherd v. Florida, 341 U. S.

50; Patton v. Mississippi, 332 U. S. 463; Pierre v. Louisiana,

306 U. S. 354; Hale v. Kentucky, 303 U. S. 613; and gradu

ate and professional education, McLaurin v. Oklahoma State

Regents, 339 U. S. 637; Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629;

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 631; Missouri ex rel.

Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337; Board of Supervisors v.

Wilson, 340 U. S. 909.

The Court has further held that in the area of inter

state travel the state’s power is further limited by the com

merce clause which similarly proscribes racial distinctions

and restrictions. Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373.

A state legislative classification violates the equal pro

tection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment either if it

is based upon nonexistent differences or if the differences

are not reasonably related to a proper legislative objective.3

Classifications based on race or color can never satisfy

either requirement and consequently are the epitome of

arbitrariness in legislation. In Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316

U. S. 535, 541, this Court held unconstitutional an Okla

homa “ habitual criminal” statute providing for steriliza

tion of persons convicted two or more times of felonies

involving moral turpitude but exempting persons convicted

of embezzlement, declaring that the State of Oklahoma

“ has made as invidious a discrimination as if it had selected

a particular race or nationality for oppressive treatment.”

Similarly, in Edwards v. California, 314 U. S. 160, 184,

where this Court invalidated a California statute making

3 Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U. S. 535; Hartford Steam Boiler

Inspection & Insurance Co. v. Harrison, 301 U. S. 459; Mayflower

Farms v. Ten Eyck, 297 U. S. 266; Concordia. Fire Insurance Co. v.

Illinois, 292 U. S. 535; Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536; Air-Way

Electric Appliance Co. v. Day, 266 U. S. 71; Truax v. Raich, 239

U. S. 33; Southern Railway Co. v. Greene, 216 U. S. 400.

2 4

it a criminal offense for any person to bring or assist in

bringing an indigent nonresident into the state, Mr. Justice

Jackson, concurring, pointed out that

“ The mere state of being without funds is a

neutral fact—constitutionally an irrelevance, like

race, creed or color.”

Likewise, in Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536, 541, where a

Texas statute confining participation in primary elections

to white persons was held to violate the equal protection

clause the Court stated:

“ States may do a great deal of classifying that

it is difficult to believe rational, but there are limits,

and it is too clear for extended argument that color

cannot be made the basis of a statutory classifica

tion affecting the right set up in this case.”

Segregation of Negroes as practiced here is universally

understood as imposing on them a badge of inferiority.4

It “ brands the Negro with the mark of inferiority and

asserts that he is not fit to associate with white people.”

It is of a piece with the established rule of the law of South

Carolina that it is libelous per se to call a white person

a Negro. Flood v. Neivs and Courier Co., 71 S. C. 112, 50

S. E. 637 (1905); Flood v. Evening Post Publishing Co.,

71 S. C. 122, 50 S. E. 641 (1905); see also: Stokes v. Gt. A.

and P. Tea Co., 202 S. C. 24, 23 S. E. 2d 823 (1943).

South Carolina has made no showing of any educa

tional objective that racial segregation subserves. Nor

could it. Efforts to conjure up theories of intellectual dif-

4 Myrdal, I An American Dilemma 615, 640 (1944); Johnson

Patterns of Negro Segregation 3 (1943) ; Dollard, Caste and Class

in a Southern Town 349-351 (1937); Note, 56 Yale L. J. 1059,

1060 (1947); Note, 49 Columbia L. Rev. 629, 634 (1949); Note, 39

Columbia L. Rev. 986, 1003 (1939).

25

ferences between races are futile. As one authority has

put i t : 5

“ * * * there is not one shred of scientific evi

dence for the belief that some races are biologically

superior to others, even though large numbers of

efforts have been made to find such evidence.”

The record in this case, contains the conclusion of an

expert, based on exhaustive investigation, that:

“ Differences in intellectual capacity or inability

to learn have not been shown to exist as between

Negroes and whites, and further, that the results

make it very probable that if such differences are

later shown to exist, they will not prove to be sig

nificant for any educational policy or practice” (R.

202) .

This conclusion accords with all the scientific investiga

tions on the subject. Klineberg, Race Differences 343

(1935); Montague, Man’s Most Dangerous Myth— The Fal

lacy of Race 188' (1945); American Teachers Association,

The Black and White of Rejections for Military Service 29

(1944); Klineberg, Negro Intelligence and Selective Migra

tion (1935); Peterson and Lanier, Studies in the Com

parative Abilities of Whites and Negroes, Mental Measure

ment Monograph (1929); Clark, Negro Children, Educa

tional Research Bulletin, Los Angeles (1923).

The record in the instant case clearly establishes that

there is absolutely no relation between race and edu

cability, and that racial distinctions in public education in

evitably injure those against whom it is directed. Appel

lants have shown that such distinctions are not relevant to

any educational objective; and they have authoritatively

5 Rose, America Divided: Minority Group Relations in the

United States 170 (1948).

26

demonstrated that classification wholly on the basis of

race in public schools cannot be condoned in the light of

this Court’s decisions in cases involving racial and other

odious classifications.

Therefore, the compelling conclusion is that the provi

sions of the Constitution and Code of South Carolina re

quiring racial segregation in education are no more capable

of surviving constitutional onslaught than the invidious

classification legislation previously voided by this Court

as repugnant to the constitutional guarantee of the equal

protection of the laws.

Ill

Neither the decision in Plessy v. Ferguson nor the

decision in Gong Lum v. Rice, are applicable to this

case.

At the conclusion of the first hearing a majority of the

District Court rejected the principles recognized in the

Sweatt and McLaurin decisions and accepted as controlling

the statements in the decisions in Plessy v. Ferguson, 163

U. S. 537 and Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 U. S. 78. The dis

senting Judge considered the decisions in the Sweatt and

McLaurin cases decisive of the issue raised.

In Plessy v. Ferguson, supra, the majority of the

Supreme Court held that the application to an intrastate

passenger of a Louisiana statute requiring the segrega

tion of white and Negro passengers did not violate the

Fourteenth Amendment, The case was decided upon plead

ings which assumed the possibility of' attainment of a

theoretical equality within the framework of racial segrega

tion, rather than on a full hearing and evidence which

would have established the inevitability of discrimination

under a system of segregation.

27

Plessy v. Ferguson is not applicable here. Whatever

doubts may once have existed in this respect were removed

by this Court in Sweatt v. Painter, supra, at page 635,

636.

Gong Lum v. Rice is irrelevant to the issues in this

case. There, a child of Chinese parentage was denied

admission to a school maintained exclusively for white

children and was ordered to attend a school for Negro

children. The power of the state to make racial distinc

tions in its school system was not in issue. Petitioner

contended that she had a constitutional right to go to

school with white children, and that in being compelled

to attend school with Negroes, the state had deprived

her of the equal protection of the laws.

Further, there was no showing that her educational

opportunities had been diminished as a result of the state’s

compulsion, and it was assumed by the Court that equality

in fact existed. There the petitioner was not inveighing

against the system, but rather that its application resulted

in her classification as a Negro rather than as a white

person, and indeed by so much conceded the propriety of

the system itself. Were this not true, this Court would

not have found basis for holding that the issue raised was

one “ which has been many times decided to be within the

constitutional power of the state” and, therefore, did not

“ call for very full argument and consideration.”

In short, she raised no issue with respect to the state’s

power to enforce racial classifications, as do appellants

here. Bather, her objection went only to her treatment

under the classification. This case, therefore, cannot be

pointed to as a controlling precedent covering the instant

case in which the constitutionality of the system itself is

the basis for attack and in which it is shown the inequality

in fact exists.

28

In any event, the assumptions in the Gong Lum case

have since been rejected by this Court. In the Gong Lum

case, without “ full argument and consideration,” the Court

assumed the state had power to make racial distinctions in

its public schools without violating the equal protection

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and assumed the

state and lower federal court cases cited in support of

this assumed state power had been correctly decided.

Language in Plessy v. Ferguson was cited in support of

these assumptions. These assumptions upon full argument

and consideration were rejected in the McLaurw and

Sweatt cases in relation to racial distinctions in state

graduate and professional education. And, according to

those cases, Plessy v. Ferguson, is not controlling for the

purpose of determining the state’s power to enforce racial

segregation in public schools.

Thus, the very basis of the decision in the Gong Lum

case has been destroyed. We submit, therefore, that this

Court has considered the basic issue involved here only

in those cases dealing with racial distinctions in education

at the graduate and professional levels. Missouri ex rel.

Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337; Sipuel v. Board of Regents,

supra; Fisher v. Hurst, 333 U. S. 147; Sweatt v. Painter,

supra; McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, supra.

IV

The equalization decree does not grant effective

relief and cannot be effectively enforced without in

volving the Court in supervising the daily operation of

the public schools.

The rights here asserted are personal and present.

At the beginning of the first hearing (R. 30-35), at the

time of the first judgment and at the time of the judgment

here appealed from, the appellants and appellees were in

29

agreement that the equal protection of the laws of South

Carolina was being denied to the appellants herein—and

the District Court twice made this finding (R. 210, 306-307).

The appellants were entitled to effective and immediate

relief as of the time of the first judgment on June 23,

1951. Sipuel v. Board of Regents, supra; Sweatt v. Painter,

supra; McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, supra.6 At

the second hearing on March 3, 1952, appellees admitted

that, although progress was being made, the physical

facilities were still unequal. The District Court ruled that

the question of the validity of the segregation laws was

foreclosed by their prior decision (R. 279, 281). Appellants

then urged that even under this ruling, they were entitled

to immediate relief by an injunction against the continua

tion of the policy of excluding them from an opportunity

to share all of the public school facilities—good and b a d -

on an equal basis without regard to race and color. This

the District Court refused to do even after a showing that

the June, 1951, decree had failed to produce even physical

equality after eight months.

Rather, the District Court again ordered an injunction

requiring the appellees to make available to appellants and

other Negro pupils of the district “ educational facilities,

equipment, curricula and opportunities equal to those

afforded white pupils” (R. 307). Appellees’ sole defense

has been complete reliance on the segregation laws of South

Carolina. As long as the District Court insists on declar

ing these laws valid and constitutional, appellees will con

tinue to enforce them. The record in this case shows that

in the past their action has discriminated against appellants

and all other Negroes. Whatever they do in the future will

be under the continuing policy of rigid racial segregation.

6 See also: Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337;

Belton, et d. v. Gebhart, et a l.,------ D e l.------ , decided August 28,

1952.

30

Education is not an inert subject. Teachers differ in

ability, personality and effectiveness, and their teachings

correspondingly vary in value. Schools differ in size, loca

tion and environment. These are among the many vari

ables in any educational system.7 Public education, as

education generally, is an ever-growing and progressing

field. Facilities and methods improve as experience dem

onstrates the need and the way. Buildings and facilities

are constantly increased to accommodate the expanding

school population. It seems clear that no two schools can

retain a constant and fixed relationship in the flux of edu

cational progress. Certainly this relationship cannot be

fixed or maintained by judicial decree.

Resolution of the basic issue in this case—the right to

equal educational benefits—by an equalization decree will

engage the parties and the court interminably. The task

of attempting equality under a segregated school system

is clearly one for which the machinery of the court is

unsuited. The decisions of this Court establish the impro

priety of a decree which would require the continuous

supervision of numerous details. United States v. Para

mount Pictures, Inc., 334 U. S. 131; Armour & Co. v. Dallas,

255 U. S. 280; Javierre v. Central Altagracia, 217 U. S.

502; Beasley v. Texas & Pacific By. Co., 191 TJ. S. 492;

Texas & Pacific Ry. Co. v. City of Marshall, 136 U. S. 393;

Rutland Marble Co. v. Ripley, 10 Wall. 339.

If under any circumstances the decree is to be effective,

even as to physical facilities, courses and teachers, children,

parents and school authorities alike must be constant liti

gants.

7 Judge Edgerton, dissenting in Carr v. Corning, 182 F. 2d 14,

31 (C. A. D. C. 1950), pointed out that:

“ * * * two schools are seldom if ever fully equal to

each other in location, environment, space, age, equipment,

size of classes and faculty.”

31

At some point appellants are entitled to conclude their

litigation and enjoy constitutional equality in the public

schools. The District Court’s decree can accomplish neither

objective. It should be annulled, and a decree entered

restraining the use of race as the factor determinative of,

the school which the child is to attend.

Conclusion

In light of the foregoing, we respectfully submit that

appellants have been denied their rights to equal educa

tional opportunities within the meaning of the Fourteenth

Amendment and that the judgment of the court below

should be reversed.

H arold R. B ottlware,

R obert L. Carter,

T hurgood Marshall,

Spottswood W. R obinson, III,

Counsel for Appellants.

W illiam T. Coleman, J r.,

George E. C. H ayes,

George M. J ohnson,

W illiam R. Ming, J r .,

Constance Raker M otley,

J ames M. Nabrit, J r .,

F rank D. R eeves,

L eonard W. Schroeter,

J ack B. W einstein,

of Counsel.

Supreme Printing Co., Inc., 41 Murray Street, N. Y 7, B A 7-0349

49