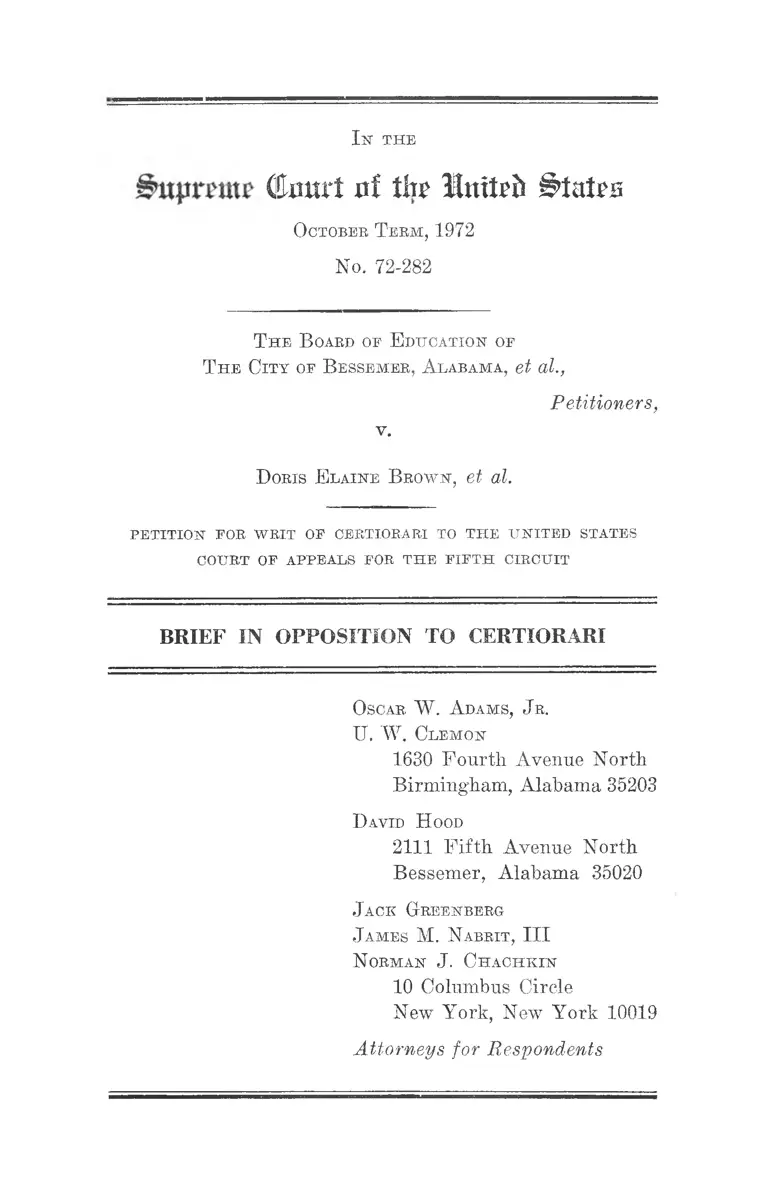

Board of Education of the City of Bessemer v. Brown Brief in Opposition to Certiorari

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1972

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Board of Education of the City of Bessemer v. Brown Brief in Opposition to Certiorari, 1972. a13ea3c6-c69a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1c405ce4-788d-48d7-9235-c5fd7d6a8c61/board-of-education-of-the-city-of-bessemer-v-brown-brief-in-opposition-to-certiorari. Accessed March 14, 2026.

Copied!

I k t h e

( ta r t of tlir luiteft itfatrs

O ctober T e r m , 1972

No. 72-282

T h e B oard of E ducation of

T h e C it y of B essem er , A labama , et al.,

v.

Petitioners,

D oris E l a ik e B r o w n , et al.

p e t it io n for w r it of certiorari to t h e u n it e d states

court of a ppea ls for t h e f if t h circu it

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO CERTIORARI

Oscar W . A dams, J r .

IT. W . Clem o n

1630 Fourth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

D avid H ood

2111 Fifth Avenue North

Bessemer, Alabama 35020

J ack G reenberg

J ames M. N abrit , III

N orman J . C h a c h k in

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Respondents

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Opinions Below ................................... 1

Jurisdiction ............................................ 2

Questions Presented ............ .............. ................. .......... 2

Statement ........................... 2

Reasons Why the Writ Should be Denied................... 3

C on clu sio n .......................................................................................... 4

I n t h e

(tart of fljo M n \ t& B u t v s

O ctober T e r m , 1972

No. 72-282

T h e B oard oe E ducation of

T h e , C ity oe B essem er , A labama , et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

D oris E la in e B r o w n , et al.

P E T IT IO N EOR W R IT OE CERTIO RARI TO T H E U N IT E D STATES

COU RT OE A PPEA L S EOR T H E F IF T H C IR C U IT

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO CERTIORARI

Opinions Below

The opinion of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fifth Circuit is not yet reported and appears at pages

A-l through A-5 of the Petition; the opinion of the United

States District Court for the Northern District of Alabama

is also unreported and appears at pages A-6 through A-ll

of the petition.

The opinion of the Court of Appeals in United States v.

Greenwood Municipal Separate School District, reprinted

at pages A-13 through A-17 of the Petition, is now reported

at 460 F.2d 1205.

2

Jurisdiction

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to 28

U.S.C. § 1254(1).

Questions Presented

1. Whether a school district must furnish transportation

to students who are reassigned beyond walking distance as

part of a desegregation plan to remedy constitutional viola

tions, rather than being allowed to bring about the failure of

the desegregation plan by refusing such transportation and

permitting students unable to furnish their own transporta

tion to attend segregated schools.

2. Whether Section 803 of the Education Amendments

of 1972, P.L. 92-318, applies to district court orders de

signed to remedy unlawful segregation and not to achieve

racial balance.

Statement

Subsequent to the entry of judgment by the Court of

Appeals, the district court held a hearing on August 21,1972

and entered an order deleting from its prior decree the pro

vision permitting students unable to obtain transportation

to their assigned high school to transfer to the other high

school. The application for recall and stay of the mandate

of the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

filed July 18, 1972 was denied by the Court of Appeals on

August 17, 1972; no such stay application was ever ad

dressed to a Justice of this Court by petitioners.

3

Reasons Why the Writ Should be Denied

Pursuant to the order of the district court of August 30,

1971 (which did not require the school district to furnish

transportation but allowed pupils unable to reach the high

school to which they were assigned under the Court-ap

proved desegregation plan without free transportation to

remain at the other high school), 111 black students and 26

white students in the Bessemer school system returned to

the schools they had previously attended. Accordingly, dur

ing the 1971-72 school year, the high schools remained sub

stantially segregated.

These facts make it clear that the furnishing of pupil

transportation by the school system is an essential prerequi

site to an effective plan of desegregation as required by

Green v. County School Board of New Kent County, 391

U.S. 430 (1968) and Swann v. Charlotte-MecMenburg Board

of Educ., 402 TT.S. 1 (1971). The judgment below is clearly

correct and, of course, the identical result was reached by

the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

in Brewer v. School Board of City of Norfolk, 456 F.2d 943,

cert, denied, 406 U.S. 905 (1972). Accord, United States v.

Greenwood Municipal Separate School Dist., supra. There

is absolutely no ground whatsoever warranting review of

the decision below.*

As to Section 803, we respectfully refer the Court to the

construction of the statute by Mr. Justice Powell in Drum

mond v. Acree, No. A-250 (September 1, 1972). That correct

interpretation of the statute, which is reflected in the ac

tions of other Justices during the Court’s summer recess

* Petitioners’ attempt to distinguish this ease from Swann must

fa il; the Charlotte school system was required by the district court’s

desegregation order to enlarge its transportation system by adding

far more new vehicles and personnel than will be required in Bes

semer.

4

denying stays in desegregation cases, is dispositive of the

issue here. Furthermore, since no application to a Justice

of this Court for such a stay was made following the denial

of a stay by the Court of Appeals, and the plan has now

been effectuated with free transportation, the issue will be

mooted before this Court could render a decision on the

merits even were it to grant the writ.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, respondents respectfully

pray that the Petition be denied.

Respectfully submitted,

Oscab W . A dams, J b .

I I . W . Cuemost

1630 Fourth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

D avid H ood

2111 Fifth Avenue North

Bessemer, Alabama 35020

J ack Gbeekbebg

J am es M. N abbit , III

N obman J . C h a c h k in

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Respondents

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C. 219