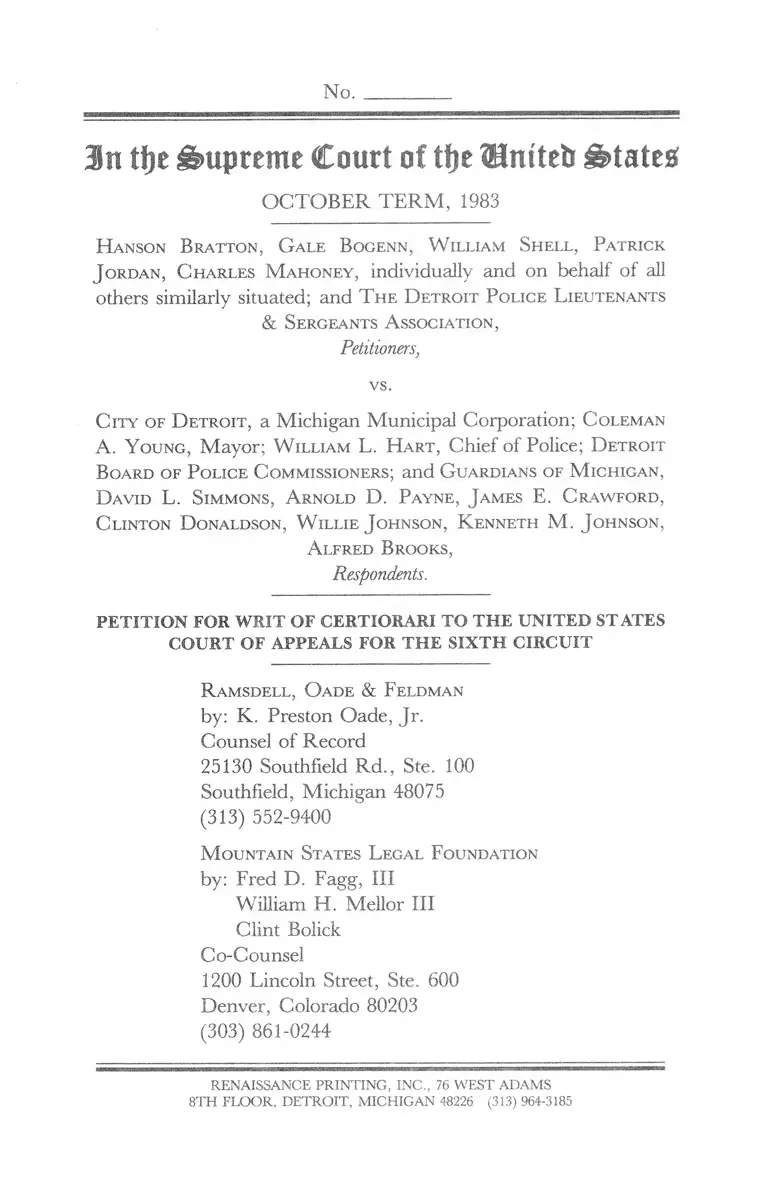

Bratton v. City of Michigan Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

Public Court Documents

September 30, 1983

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bratton v. City of Michigan Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, 1983. a3fc1345-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1c545f30-5bf8-4d78-b93e-1d7d1ea05011/bratton-v-city-of-michigan-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-united-states-court-of-appeals-for-the-sixth-circuit. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

No.

in tfje Supreme Court of tfje Hmtetr states?

O CTO BER TERM , 1983

H a n s o n B r a t t o n , G a l e B o g e n n , W il l ia m S h e l l , P a t r ic k

J o r d a n , C h a r l e s M a h o n e y , individually and on behalf of all

others similarly situated; and T h e D e t r o it P o l ic e L ie u t e n a n t s

& S e r g e a n t s A s s o c ia t io n ,

Petitioners,

vs.

C it y o f D e t r o i t , a Michigan Municipal Corporation; C o l e m a n

A. Y o u n g , Mayor; W il l ia m L. H a r t , Chief of Police; D e t r o it

B o a r d o f P o l ic e C o m m is s io n e r s ; and G u a r d ia n s o f M ic h ig a n ,

D a v id L. S im m o n s , A r n o l d D. P a y n e , J a m e s E. C r a w f o r d ,

C l in t o n D o n a l d s o n , W il l ie J o h n s o n , K e n n e t h M . J o h n s o n ,

A l f r e d B r o o k s ,

Respondents.

P E T IT IO N FOR W R IT O F C ER TIO RA RI T O T H E U N IT E D STATES

CO U R T O F APPEALS FOR T H E S IX T H C IR C U IT

R a m s d e l l , O a d e & F e l d m a n

by: K. Preston Oade, Jr.

Counsel of Record

25130 Southfield Rd., Ste. 100

Southfield, Michigan 48075

(313) 552-9400

M o u n t a in S t a t e s L e g a l F o u n d a t io n

by: Fred D. Fagg, III

William H.^Mellor III

Clint Bolick

Co-Counsel

1200 Lincoln Street, Ste. 600

Denver, Colorado 80203

(303) 861-0244

RENAISSANCE PRINTING, INC., 76 WEST ADAMS

8TH FLOOR, DETROIT, MICHIGAN 48226 (313) 964-3185

1

Q U ESTIO N S PR ESEN TED

1. W hether the use of a racial quota by a municipal govern

ment should be reviewed under a standard of “ reason

ableness” as opposed to the traditional strict scrutiny

standard of review applicable to all governmentally im

posed racial classifications?

2. W hether it is permissible for a municipal government to

impose a 50/50 racial quota for promotions from police

sergeant to lieutenant where a collectively bargained non-

discriminatory merit examination process is already in

place?

3. W hether a municipal government may impose a racial

quota for promotion to achieve a specified percentage of

black lieutenants equivalent to the general population

rather than reflecting the percentage of black employees

who would have been hired and promoted in the absence of

past discrimination as shown by relevant labor market

statistics?

4. W hether a municipal government that has successfully

eliminated all discriminatory employment practices must

limit the use of racial preferences to benefit only actual vic

tims of past discrimination, or is discrimination in favor of

black employees justified to redress wrongs committed by

the police force against black citizens many years earlier?

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Q U ESTIO N S PR E S E N T E D ........................................ i

TABLE OF A U T H O R ITIES ...................................... iv

O PIN IO N S BELOW ..................................................... viii

JU R ISD IC T IO N ............... viii

C O N STITU TIO N A L AND STA TU TO RY

PRO VISION S IN V O L V E D .................................... ix

STA TEM EN T OF T H E C A S E .................................... 1

A. In troduction ............................................................ 1

B. Description of P a rtie s ............................................ 1

C . Procedural H istory ................................................ 2

D. Facts and B ackground.......................................... 3

E. Decisions B e lo w ..................................................... 7

REASONS FO R G RA N TIN G T H E W R I T ........... 9

I. This Case Presents Pervasive Issues of Vital

National Concern Relating to Racial

Preferences in Public Em ploym ent.................. 9

II. Judicial Review of Governmentally Imposed

Racial Preferences is Characterized By

Confusion and C o n flic t..................................... 11

III. The Decisions Below Conflict in Principle

with Bakke, Weber, and Fullilove, and Squarely

Collide with the Requirement that the Nature

of the Violation Must Determine the Scope of

the R em edy............................................................ 14

IV. The Case is Ripe for Review and Presents a

Fully Developed Record for this Court to De

cide Appropriate Standards for the Remedial

Use of Race in Public Em ploym ent.................. 22

ii

Ill

C O N C L U SIO N .............................................................. 24

A P P E N D IX .......................................................................

Opinion O f The United States Court of

Appeals For The Sixth C ircu it............................. . la

Certificate O f Public Importance By The

Attorney General O f The United S ta te s ............. 46a

O rder Denying The United States O f America

Leave To In te rv e n e ................................................. 47a

Petition For Rehearing And Suggestion O f

Rehearing En Banc ............. 51a

O rder Denying Petition For R ehearing.................... 77a

Dissenting Opinion From O rder Denying

Rehearing En Banc ................................................. 79a

O rder of Judgm ent Affirming District C o u r t ......... 83 a

Opinion O f The U.S. District Court For The

Eastern District of M ic h ig a n ............................. 85 a

Final Opinion O f The U.S. District C o u r t ............. 235a

Judgm ent O f The U.S. District Court ....................... 255a

IV

TABLE OF A U T H O R ITIES

CASES PAGE

Baker v. City of Detroit, 483 F. Supp. 930

(E.D. Mich. 1979) ............................................... viii

Baker v. City of Detroit, 504 F. Supp. 841

(E.D. Mich. 1 9 8 0 ) ................................... viii

Bratton v. City of Detroit, 704 F.2d 878 (6th Cir.

1983)....................................................................... viii

Connecticutv. Teal, 457 U.S. 440 (1982).................. 19

Dayton Bd. of Educ. v. Brickman, 433 U.S. 406

(1 9 7 7 ) .................................................................... 18

Detroit Police Officers Ass’n. v. City of Detroit, 233

N .W .2d49(1975)................................................. 2

Detroit Police Officers Ass’n v. Young, 608 F.2d 671

(6thC ir. 1979) .......................... 4,7,22

E.E.O.C. v. American Telephone and Telegraph Co.,

556 F.2d 167 (3d Cir. 1 9 7 7 )............................... 12

Firefighters Institute for Racial Equality v. City of

St. Louis, 616 F .2d 350 (8th Cir. 1980)............. 12

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 747

(1 9 7 6 ) .............................................. 20

Fullilovev. Klutzmk, 448 U.S. 448(1980) ............. passim

Hazelwood School District v. United States, 433 U.S.

2 9 9 ,(1 9 7 7 )................................ 16,17

Hill v. Western Electric Co., 596 F.2d 99 (4th Cir.

1979)............. 12

In t’l Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United States, 431

U.S. 324(1977)................... 17,21

Kirkland v. New York State Department of Correctional

Services, 520 F.2d 420 (2d Cir. 1975).................. 12

V

Millikenv. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717(1974) ............... 17,19

Minnick v. California Department of Corrections, 452

U.S. 105(1981)..................................................... 22

NAACPv. Allen, 493 F .2d614(5thC ir. 1974) . . . 12,13,20

Parker v. Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Co., 652 F.2d

1012 (D .C .C ir. 1981)................. 12

Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, 438

U.S. 265(1978)..................................................... passim

Sledge v. J.P. Stevens & Co., 585 F.2d 625

(4thC ir. 1978) ................................................ 12

Stotts v. Memphis Fire Dept. (No. 82 -2 2 9 )................ 11

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenberg Bd. of Education, 402

U.S. 1(1971).............................. .......................... 17

U.S. v. City of Chicago, 549 F.2d 415 (7th Cir.

1977)....................................................................... 12

U.S. V. City of Chicago, 663 F.2d 1354 (7th Cir.

1981)................................................................. .. . 13

U.S. v. City of Miami, 614 F.2d 1322 (5th Cir.

1980) ...................................... 12

United Steelworkers of America v. Weber, 443 U.S.

193 (1979 )............... passim

Valentine v. Smith, 654 F.2d 503 (8th Cir. 1981). . . 12

Williams v. City of New Orleans, 543 F. Supp. 662

(E.D. La. 1982)........... 11

Williams v. City of New Orleans, 694 F.2d 987

(5th Cir. 1982), rehearing en banc granted,

694 F.2d 998 (1983) ........ 11

V I

C O N STIT U T IO N A L PRO V ISIO N

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States

C onstitu tion ............... passim

FEDERAL STA TU TES

28U .S .C .§ 1254(1)................................................. viii

28 U .S.C . §§ 1441 and 1443.................... ............... 2

42U .S .C .§ 1983 . . ............. ix.2.21

Title V II Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended,

42 U .S.C . § 20Q0e etseq ................................. passim

LOCAL STA TU TES

Michigan Public Employee Relations Act,

Mich. Comp. Laws Ann. § 423.201, etseq . . . . 2

Detroit City Charter, § 7-1103 .................... 2

Detroit City Charter, § 7-1114............... vi,2

M ISCELLA N EO US

Brown, Court-Ordered Racial Discrimination in

‘ A merica ’s Finest City, ’ ’ 3 Lincoln Rev. 9 (1983) 10

Buzawa, The Role of Race in Predicting Job Attitudes

of Patrol Officers, 9 J. Grim. Just. 63 (1981) . . . . 10

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission,

Eliminating Discrimination in Employment: A

Compelling National Priority (1 9 7 9 )...................... 13,20

Schlei and Grossman, Employment Discrimination

Law (2d ed. 1 9 8 3 ).................... ............................

Sowell, Dissenting from Liberal Orthodoxy (1976) . . .

U .S. Commission on Civil Rights, Affirmative

Action in the 1980’s: Dismantling the Process of

Discrimination (1 9 8 1 )............................................

U .S. Commission on Civil Rights, The State of

Civil Rights: 1979 (1980 )......................................

Williams, America: A Minority Viewpoint ( 1982) . . .

W ortham, The Other Side of Racism (1981 ).............

V l l l

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review the

judgm ent of the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth

Circuit entered in this case on M arch 29, 1983 and issued as

mandate on June 21, 1983.

O PIN IO N S BELOW

The opinion of the Court of Appeals is reported as Bratton v.

City of Detroit, 704 F.2d 878 (6th Cir. 1983), and is reproduced

at pages l-45a of the Appendix hereto. The consolidated

M emorandum Opinion of the District Court is reported as

Baker v. City of Detroit, 483 F. Supp. 930 (E.D. Mich. 1979),

reproduced at pages 85-234a in the Appendix. The Final opin

ion of the District Court is reported at 504 F. Supp. 841 (E.D.

Mich. 1980), set out in the Appendix at pages 235-254a.

The opinion and order of the Court of Appeals denying the

petition for rehearing en banc and vacating in part the final

order of the District Court is reproduced at page 77a of the

Appendix, with the separate dissenting opinion from the

order denying rehearing en banc at page 79a.

JU R IS D IC T IO N

The Court of Appeals decided and filed its opinion on

M arch 29, 1983, and denied rehearing on June 3, 1983. By

order of this Court entered by Justice White on August 8,

1983, the time for filing this petition was extended to and

including October 1, 1983. This Court has jurisdiction pur

suant to 28 U .S.C . § 1254(1) (1976).

I X

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED

The provisions of the United States Constitution involved

in this case are the Equal Protection and Due Process clauses,

which provide in pertinent part:

No state shall . . . deprive any person of life, liberty, or pro

perty without due process of law; nor deny to any person

within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

The statutory provisions involved include 42 U .S .C .

§ 1983, as well as sections 703(a), (h), and (j), of Title V II of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended, 42 U .S.C . §§

2000e-2(a), (h), and (j) (1976) [hereinafter Title VII], pro

viding in pertinent part:

42 U .S .C . § 1983

Every person who, under color of any statute, ordinance,

regulation, custom, or usage, of any State . . . causes to be

subjected, any citizen of the United States . . . to the depri

vation of any rights, privileges, or immunities secured by

the Constitution and laws, shall be liable to the party in

jured in an action at law, suit in equity, or other proper pro

ceeding for redress . . . .

42 U .S .C . § 2000e-2

(a) It shall be an unlawful employment practice for an

employer —

(1) to fail or refuse to hire or to discharge any individual,

or otherwise to discriminate against any individual with

respect to his compensation, term s, conditions, or

privileges of employment, because of such individual’s

race .. .; or

(2) to limit, segregate, or classify his employees or ap

plicants from employment in any way which would

deprive or tend to deprive any individual of employment

X

opportunities or otherwise adversely affect his status as

an employee, because of such individual’s race, . . . .

(h) Notwithstanding any other provision of this sub

chapter, it shall not be an unlawful employment practice for

an employer to apply different standards of compensation,

or different terms, conditions, or privileges of employment

pursuant to a bona fide seniority or merit system . . . pro

vided that such differences are not the result of any inten

tion to discriminate because of race . . . , nor shall it be an

unlawful employment practice for an employer to give and

to act upon the results of any professionally developed

ability test provided that such test, its administration or ac

tion upon the results is not designed, intended or used to

discriminate because of race . . . .

(j) Nothing contained in this title shall be interpreted to re

quire any em ployer . . . subject to this title to grant

preferential treatment to any individual or to any group

because of race . . . of such individual or group on account

of an imbalance which may exist with respect to the total

number or percentage of persons of any race . . . employed

by any employer . . . in comparison with the total number

or percentage of persons of such race . . . in any

community, State, section, or other area, or in the available

work force in any community, State, section or other area.

1

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

A. Introduction.

The Police D epartm ent of the City of Detroit consists of

patrolmen, sergeants, lieutenants, inspectors, commanders,

deputy chiefs, and ultimately the Chief of Police who is ap

pointed by the Mayor. As of 1973, and possibly as early as

1968, the mechanism governing promotions from sergeant to

lieutenant (a combination of merit examination and seniority

factors) had no disparate impact on blacks, i. e., blacks were

being promoted to lieutenants at rates at least equal to their

rep resen ta tio n am ong prom otional candidates in the

sergeants ranks. Although for many years under-represented

in the Detroit police force, by 1974, in part as a result of affir

mative action recruiting efforts that began in 1968, blacks

constituted approximately 11 % of the sergeant ranks.

In 1974, the newly elected administration of M ayor Cole

man A. Young imposed a strict 50/50 racial quota on, inter

alia, promotions from sergeant to lieutenant. By order of the

courts below, this racial preference is to remain in effect at

least until 1990, and possibly longer, in order to reach an

ultimate goal of black representation among the lieutenant

group that mirrors black representation in the city population.

As a result of this racial quota, the black promotion rate to

lieutenant was in 1974 and continues to be several times the

promotion rate that would be expected with a racially neutral

system. Black sergeants with lower examination scores than

white sergeants are promoted to lieutenant solely because half

of the promotional opportunities have been guaranteed to

blacks. Petitioners challenge the decision of the Court of Ap

peals, which sustained the 50/50 quota in its entirety.

B. Description of Parties.

Petitioners Bratton and other named individuals (Plain

tiffs/Appellants below) represent a class of adversely affected

2

white male sergeants who, since November of 1975, have

been or will be denied timely promotion to the rank of lieuten

ant solely because of their race. The Detroit Police Lieuten

ants & Sergeants Association is the exclusive bargaining agent

and the signatory to the collective bargaining agreement with

the City of Detroit, pursuant to the Michigan Public Em

ployees Relations Act (PERA), Mich. Comp. Laws Ann.

(MCLA) § 423.201, et seq.

Respondent Detroit Board of Police Commissioners (the

“ Board” ) is a five-member body appointed by the Mayor,

Respondent Coleman A. Young. U nder § 7-1103 of the

Detroit City Charter, the Board establishes “ policies, rules

and regulations” for the Police Departm ent “ in consultation

w ith” the Respondent Chief of Police, ‘ ‘with the approval of

the M ayor.” Respondent Guardians of Michigan is a minority

organization which intervened as a Defendant shortly before

trial.

C. P rocedural H istory.

Petitioners commenced this action in a state circuit court in

November, 1975. It was subsequently removed to federal

district court pursuant to 28 U .S.C . § § 1441 and 1443. In

terim injunctive relief was denied, and the quota has been ap

plied throughout the litigation and continues to date.

As amended, the complaint alleges that the 50/50 racial

quota for promotions from sergeant to lieutenant violates

Title VII, 42 U .S.C . § 1983, and the Fourteenth Amendment

to the United States Constitution.1 The district court upheld

1 Pendent state claims not addressed below include violations of § 7-1114

of the Detroit C ity C harter and the collective bargaining agreem ent re

quiring m erit exam inations for prom otions, as well as violations o f the

M ichigan Public Employees Relations Act (PERA ), M C LA 423.201, et

seq. PER A imposes the obligation of good faith bargaining on all prom o

tion standards and criteria as a term and condition of em ploym ent. See,

Detroit Police Officers A ss’n v. City of Detroit, 233 NW 2d 49 (1975).

3

the quota, and incorporated the program into its final judicial

decree. See Appendix at 255-261a [hereinafter App.]. The

Sixth Circuit affirmed on M arch 29, 1983. O n April 28, 1983,

the United States of America, through the Civil Rights Divi

sion of the Justice Department, sought leave to intervene as a

party appellant and to file a suggestion of rehearing en banc.

The motion was denied on M ay 27, 1983, with Judge M erritt

dissenting. (App. 47-50a).

The Sixth Circuit denied Petitioner’s Motion for Rehearing

and suggestion of rehearing en banc per Order dated June 3,

1983. The O rder also vacated that part of the district court’s

final O rder incorporating the quota into a judicial decree, and

remanded for further consideration of the 50 % quota in view

of the 1980 census showing a Detroit black population of 63 % .

(App. 78a). Circuit Judge Wellford filed a separate opinion

dissenting from the denial of rehearing en banc. (App. 79a).

D . Facts and Background.

The 50/50 quota on promotions to lieutenant was adopted

by the newly-appointed Board of Police Commissioners in

June, 1974, as part of a plan designed to remedy the Police

D epartm ent’s prior discriminatory employment practices and

to meet what the Board perceived to be an “ operational need’ ’

for more black police officers and supervisors. The 50% figure

was based upon the racial composition of the general popula

tion of the City of Detroit in 1974. Jo in t Appendix on Appeal

to the Sixth Circuit at 1237 [hereinafter J .A J . U nder the

plan, the Police Departm ent allocates 50% of all promotions

to black employees at every rank and level of the Department.2

2 In the 1973 M ayoral race, candidate Colem an A. Y oung cam paigned

on a pledge to the voters of proportional representation between the

C ity’s work force and the population. (J.A . 1088). Accordingly, when

the M ayor took office in Ja n u a ry of 1974, his C hief o f Police adopted as a

top priority the im plem entation of a 50/50 racial hiring and prom otional

policy. (J.A . 1124-25).

4

This case, however, involves only promotions from sergeant

to lieutenant since November of 1975.3

Prior to the imposition of the racial quota, all sergeants who

were candidates for promotion to lieutenant were ranked on a

single list according to numerical ratings based on various

performance evaluation factors, including individual exam

scores, oral board scores, educational attainment, seniority,

and other factors. (App. 152a). Promotions were made in

rank order from the resulting eligibility list of candidates.

While the Department did not keep statistics by race prior to

1973, the district court found that “ there is no question,

however, that the 1973 and 1974 promotional examinations

were not themselves discriminatory.’’ (App. 153a). At trial,

experts for both sides agreed that the 1973 eligibility list was

racially neutral, and that subsequent promotional exams and

resulting eligibility lists did not have any disparate impact

against black candidates.4

The Sixth Circuit’s opinion describes the operation of the

50/50 racial quota as follows:

The plan mandates that two separate lists for promotion

be compiled, one for black and the other for white officers.

The rankings on those lists are then made in accordance

with the same numerical rating system previously em

ployed. The promotions are made alternatively from

T he issue of prom otions from patrolm an to sergeant is currently pend

ing in the district court upon rem and in the related case of Detroit Police

Officers A ss’n. v. Young, 608F .2d671 (6th C ir. 1979), cert, denied, 452U .S .

938 (1981). Unlike the facts here, Young involves an exam ination for pro

m otions to sergeant which is alleged to have a disparate im pact against

blacks.

The district court s conclusion that the pre-1973 prom otional exams

had a disparate im pact on black candidates was inferred from the content

of the pre-1973 written exam inations. (App. 135-137a).

5

each list so that white and black officers are promoted in

equal numbers. The 50/50 plan is to remain in effect until

fifty percent of the lieutenant’s corps is black, an event

estimated to occur in 1990. (App. 4a).

Although the merit examination process was itself non-

discriminatory, the 1975 Board cited the imbalance between

the percentage of black police lieutenants as compared to the

general population of the City of Detroit. The Board made no

attempt to provide remedial relief on an individual basis, nor

did it attempt to define the extent of such past discrimination

through an analysis of the relevant labor market or labor pool,

relying instead on general population figures to determine the

50% goal. (App. 25a). This effort to achieve a racial balance

in the police department was acknowledged at trial by Chief of

Police H art, who conceded that the quota was not based upon

particularized needs, but rather reflected “ the mandate of the

M ayor, the m an in charge of the City. ” (J.A . 700).

The position of lieutenant is a specialized one, requiring

several years of experience and well-developed skills. As a

result, the relevant labor market is substantially narrower

than the general population. At trial, the City’s own expert5

attempted to define the relevant labor market to deter

mine racial disparities, if any, among the lieutenant ranks.

(App. 139a). Based on an analysis of the relevant labor market

as derived from a count of actual applications for employment

with the Department, he estimated the num ber and percent

age of black lieutenants that could have been expected in an

environment free of discrimination in both hiring and promo

tions since 1945. As of June, 1978, his estimate was 49 black

5 M r. A lan Fechter, who is incorrectly identified in the C ourt of Appeals

opinion as “ Appellants (Petitioners) own statistical expert, M r. Alan

Fechter” . (App. 27a).

6

male lieutenants out of a total of 194 lieutenants, or 25%.

(J .A . 1764). In fact, however, there were 41 black male lieu

tenants out of 194, or 21 % by that date.6 Fechter testified that

this difference between the expected and actual num ber of

black lieutenants in 1978 was not statistically significant.

(J.A . 1044). The district court, however, concluded that this

was a substantial difference justifying continued application of

the quota well beyond 1978. (App. 143a).

The following table illustrates the increased numbers of

blacks at every level of the Department since 1975. W hen the

quota was implemented in November, 1975, blacks repre

sented 22 % of total department personnel and 6% of the lieu

tenant’s ranks, down from 10% two months earlier (J.A. 1537)

because a disproportionately high number of black lieutenants

were appointed to the higher ranks of inspector and above

(J.A . 1538).

Racial Breakdow n of Police C om m and Officers7

____ lieutenants____ Inspectors Commanders & Above

White Black White Black White Black

1975 — 195 (89%) 23 (11%) 47 (84%) 9 (16%) 14 (64%) 8 (36%)

1976 — 161 (90%) 18 (10%) 43 (74%) 15 (26%) 15 (58%) 11 (42%)

1977 — 176 (78%) 51 (22%) 43 (66%) 21 (32%) 17 (63%) 10 (37%)

1978 — 154 (78%) 44 (22%) 38 (60%) 24 (38%) 16 (53%) 13 (43%)

1979 — 145 (77%) 44 (23%) 35 (59%) 23 (39%) 16 (55%) 12 (41%)

1980 — 151 (73%) 56 (27%) 36 (58%) 25 (40%) 15 (54%) 12 (43%)

1981 — 145 (73%) 54 (27%) 32 (56%) 24 (42%) 15 (50%) 14 (47%)

1982 - 138 (72%) 53 (28%) 28 (54%) 23 (44%) 15 (54%) 12 (43%)

1983 — 145 (70%) 62 (30%) 34 (54%) 28 (44%) 16 (52%) 14 (45%)

6 This 21 % figure does not include seven additional black female

lieutenants in Ju n e , 1978.

7 Source: U pdated statistics subm itted by order to the Sixth Circuit.

Discrepancies between the num ber of lieutenants above and those set out

in the Sixth C ircu it’s opinion (App. 17a) are the result of the C o u rt’s in

clusion of H ispanic and Asian officers as “ w hite” , which were deleted in

(footnotes continued on next page)

7

E. Decisions Below.

The district court found that the selection rates of the com

petitive merit examination process had no disparate impact

against black candidates for promotion since such statistics

were compiled starting in 1973. (App. 153a). It also found

that the racial classification creating two separate lists for pro

motion “ is unquestionably a racial preference and unques

tionably impacts against white officers.” (App. 185a).

Nonetheless, it concluded that the City ‘ ‘acted reasonably

when it adopted its affirmative action plan. ’ ’ Id. Extending its

interpretation of United Steelworkers of America v. Weber, 443

U .S. 193 (1979) to the case of a public employer (App. 201a),

the district court held that a broad ‘ ‘ area of discretion’ ’ exists

for employers to design and implement “ voluntary” affirma

tive action programs. (App. 192a). The district court then

concluded that the promotion quota was a “ reasonable”

effort to remedy the present effects of the C ity’s past inten

tional employment discrimination, which did not cease until

1967-1968, when an affirmative action minority recruitment

p ro g ram was in s ti tu te d by the D e p a rtm e n t. (A pp.

210-211a).8

The Sixth Circuit affirmed. Noting that “ what is valid

under [the Fourteenth Amendment] will certainly pass muster

under Title V II” (App. 13a), the Sixth C ircuit’s analysis

focused solely on the constitutionality of the Board’s 50/50

promotion quota. The Court of Appeals considered itself

bound by Detroit Police Officers Ass ’n v. Young, supra, which dealt

with a similar 50/50 quota on promotions from patrolman to

(footnotes continued from previous page)

the table above. These statistics are on file with the D etroit Police D epart

m ent Statistical Section, and are published yearly in the D etroit Police

D epartm ent A nnual Report.

8 T he court also based its holding on Respondents’ contention that the

D epartm en t’s “ operational needs” justified im position of the prom o

tional quota for lieutenants. (App. 226-229a). In a separate final opinion,

(footnote continued on next page)

8

sergeant, (App. 10a, n. 26). The court relied on Young’s

“ reasonableness’ ’ standard which, according to the Sixth C ir

cuit, requires an examination of whether any discrete group

or individual is stigmatized by the racial classification and

whether racial classifications have been “ reasonably used in

light of the program ’s remedial objectives.” (App. 13a, 20a).

Applying this standard to the instant case, the Court of Ap

peals concluded that the 50/50 quota (1) did not unduly

stigmatize anyone (App. 20a-23a), and (2) passed the “ test of

reasonableness.” (App. 23a). The court found it “ unneces

sary to address the validity of the operational needs defense to

affirmative action in this context.” (App. 12a n. 30).

The Court of Appeals held that to the extent to which the

50/50 quota is excessive as a remedy for past discrimination in

employment, it can be justified due to a prior “ pattern of

unconstitutional deprivation of the rights of a specific, iden

tifiable segment of the Detroit population by white members of

the segregated Police Departm ent,” and concluded that the

“ redress of this injury to the black population as a whole

justifies a plan which goes beyond the. . . work force limitation

which appellants imply may have been appropriate. ”

(App. 31a). Judge M erritt, dissenting in part, argued that “ the

Fourteenth Amendment requires a more exacting standard

than the open-ended mere ‘reasonableness’ stated by the

C ourt.” (App. 45a).

In its order denying rehearing, the court vacated that part

of the district court’s final order holding that the quota was

constitutionally required at the 50% level, and remanded for

reconsideration of the quota in light of the 1980 census showing

a black City population of 63%. (App. 79a). Circuit Judge

( footnote continued from previous page)

the district court incorporated the B oard’s prom otional quota for

lieutenants into a final and m andatory judicial decree, holding that the

quota was constitutionally required until the 50% black end-goal was

achieved. (App. 255a-261a).

9

Wellford filed a separate opinion dissenting from the denial of

rehearing en banc, expressing his view that the court “ inappro

priately considered the racial breakdown of the Detroit popula

tion as a whole instead of the racial breakdown of the applicable

qualified labor pool.” (App. 79a).

REASONS FOR G RANTING T H E W R IT

I. T H IS CASE P R E S E N T S PER V A SIV E

ISSU ES O F V ITA L N A TIO N A L C O N

CERN RELATIN G TO RACIAL P R E FE R

ENCES IN PU B LIC EM PL O Y M E N T .

Although there is substantial litigation in the area of

municipally imposed racial preferences in public employ

m ent,9 this Court has dealt only peripherally with these issues

in three principal cases: Regents of the University of California v.

Bakke, 438 U.S. 265 (1978); United Steelworkers of America v.

Weber, supra; and Fullilove v. Klutznik, 448 U .S. 448 (1980).

None of these cases directly addresses the pervasive issue of

the applicable parameters of municipal discretion to impose

racial quotas to remedy perceived past discrimination.

The U .S. Civil Rights Commission has singled out the

issue of municipal authority to impose racial quotas in public

employment as a principal unanswered question in affirm

ative action law, see U .S. Commission on Civil Rights, Affirm

ative Action in the 1980’s: Dismantling the Process of Discrimination

28 (1981), and has cited the district court opinion in the in

stant case as expressing the applicable state of the law on these

issues. U .S. Commission on Civil Rights, The State of Civil

Rights: 1979 22-24 (1980). The Attorney General has certified

“ that the United States has determined this case to be of

general public im portance.” (App. 46a).

9 See, e.g., B. Schlei and P. Grossm an, Employment Discrimination Law

775-870 (2d ed. 1983).

10

Racial preferences, particularly in promotions, substantially

impact individual citizens. Unbridled racial quotas foster

community divisiveness, with minority individuals,10 whether

beneficiaries or not, bearing the stigma of the unearned,11 and

innocent nonminority individuals harboring sustained resent

m ent.12 A resolution of the issues in this case will thus impact

not only the parties herein, but also “ the broader question of

race relations in the City of Detroit and throughout the United

States.’’ (App. 88a).

10 T he use of the term “ m inority” here is generic rather than descrip

tive. Blacks presently constitute a m ajority of the D etroit population, and

for nearly a decade have controlled the political apparatus which produced

and m aintains the quota.

11 Several outstanding black scholars have delivered strong indictments

against governmentally imposed racial preferences and so-called “ benign”

discrim ination. See, e.g., A. W ortham , The Other Side of Racism (1981);

T. Sowell, Dissenting from Liberal Orthodoxy (1976); W . W illiams, America:

A Minority Viewpoint (1982); an d S. B row n, Court-Ordered Racial

Discrimination in America’s Finest City, ” 3 Lincoln Rev. 9 (1983).

12 A 1981 com parative study reveals that white police attitudes in D etroit

have deteriorated markedly since the im position of racial quotas. Faced

with lim ited prom otional opportunities and “ alienated from the political

struc tu re ,” 21 % of the white police officers left the D epartm ent in the

four year period between 1974-78, which the author characterized as a

“ massive tu rnover” of white police officers on the force. This situation is

contrasted with O akland, which does not utilize racial quotas and where

white police attitudes are dem onstrably better. Buzawa, The Role of Race

in Predicting Job Attitudes of Patrol Officer, 9 J . C rim , Ju st. 63 (1981).

11

II. JUDICIAL REVIEW OF GOVERNMENT-

ALLY IMPOSED RACIAL PREFERENCES

IS CHARACTERIZED BY CONFUSION

AND CONFLICT.

No decision of this Court has established parameters in the

myriad circumstances in which municipalities enact affirm

ative action plans. Stotts v. Memphis Fire Dept. (No. 82-229),

679 F.2d 541 (6th Cir. 1982), cert, granted — U.S. — , 51

U .S.L .W . 3871 (1983), will provide an opportunity to adjudge

the authority of a federal court under Title VII to require

racially preferential employee layoffs, but will leave unad

dressed the constitutionality of racial promotional quotas

established by municipalities purportedly seeking to remedy

their own past discrimination.

This Court has never issued a majority opinion setting out

the constitutional standard for reviewing racial quotas or

preferences under the Equal Protection Clause. Consequently,

the circuits have expressed confusion in determining proper

standards in such cases.13 The Sixth Circuit below noted the

“ inherent uncertainty of the law in this area’ ’ (App. 36a) and

rendered its decision despite a perceived absence of agreement

within this Court “ on the nature of the governmental interest

which must be at stake, on the finding necessary to establish

the presence of that interest [and] on the standard under

which the method employed to achieve that interest is to be

reviewed.” (App. 9a). Similarly, the Fifth Circuit, citing

Bakke, complained that “ the Justices have told us mainly that

13 This confusion is illustrated in Williams v. City of New Orleans, in which

the district court denied a consent decree incorporating racial prom otion

quotas, 543 F. Supp. 662 (E .D . La. 1982), which denial was reversed and

rem anded on appeal, 694 F.2d 987 (5th Cir. 1982), and which m andate

was dissolved and rehearing en banc granted, 694 F. 2d 998 (5th Cir.

1983).

12

they agree to disagree.” U.S. v. City of Miami, 614 F.2d 1322,

1337 (5th Cir. 1980). Accord generally, e.g., Valentine v. Smith,

654 F.2d 503, 508 (8th Cir. 1981); Parker v. Baltimore and Ohio

Railroad Co., 652 F.2d 1012, 1020 (D .C. Cir. 1981). As a

result, conflicts among the circuits on issues presented in this

case are plentiful, including the following:

A. Promotion quotas. The circuits disagree on the propriety of

imposing racial quotas for promotions. The Fourth Circuit, in

reversing a public employment promotion quota, noted that

the relevant labor market for promotions is not the pool of

potential employment applicants, but rather the smaller pool of

experienced, qualified employees. Hill v. Western Electric Co.,

596 F.2d 99, 105-06 (4th Cir. 1979). And the Second Circuit,

recognizing important differences between hiring and promo

tion quotas in terms of the degree of injuries suffered by inno

cent persons, reversed such a quota in Kirkland v. New York State

Department of Correctional Services, 520 F.2d 420, 429 (2d Cir.

197o). The reasoning of the Second Circuit was specifically re

jected by the trial court below (App. 195-96a) in upholding

Respondents 50/50 promotion quota. Other circuits have join

ed the Sixth Circuit in sustaining promotion quotas. See

E.E.O.C. v. American Telephone and Telegraph Co., 556 F. 2d 167

(3d Cir. 1977): U.S. v. City of Chicago, 549 F.2d 415 (7th Cir.

1977); Firefighters Institute for Racial Equality v. City of St. Louis

616 F. 2d 350 (8th Cir. 1980).

B. Less harmful alternatives. In Sledge v. j .P . Stevens & Co.,

585 F .2d 625, 646-47 (4th Cir. 1978), the court reversed a

remedial decree requiring hiring quotas, noting the existence

of less burdensome means to achieve equal employment oppor

tunity. The Fifth Circuit in NAACP v. Allen, 493 F. 2d 614, 621

(5th Cir. 1974) instructed that quotas may be imposed only

where less burdensome alternatives have failed. Contrast the

instant case, in which a rigid 50/50 promotion quota was

13

superimposed on existing hiring quotas and admittedly non-

discriminatory promotion procedures which provided equal

opportunity based on merit. While conceding that the 50/50

ratio “ is unquestionably a racial preference and it unques

tionably impacts against white officers,” (App. 185a), the

trial court made no finding that less harmful alternatives had

failed to provide equal opportunity or were inadequate to

remove the vestiges of past discrimination over time.

C. Duration. The Fifth Circuit in NAACPv. Allen, 493 F.2d

at 621, admonished that in the narrow circumstances in which

a quota is justified, it should seek “ to spend itself as promptly

as it can by creating a climate in which objective, neutral

employment criteria can successfully operate.” Accord, Equal

Employment O pportunity Commission, Eliminating Discrimi

nation in Employment: A Compelling National Priority III-3 (1979).

And the Seventh Circuit recognized that failure to modify or

eliminate racial quotas where they are no longer justified

results in “ unfairness to innocent individuals.” U.S. v. City of

Chicago, 663 F. 2d 1354, 1361 (7th Cir. 1981). The Sixth C ir

cuit below, while terming the quota “ tem porary,” upheld a

program which will operate for at least sixteen years and not

spend itself until a balance in the lieutenants’ ranks consistent

with the general population is reached. Given the C ity’s goal

of racial balancing, along with rapidly changing demographic

patterns, it is clear that the quota cannot be fairly character

ized as temporary in nature.14

These conflicts among the circuits are central to the ques

tion of the extent to which municipalities may offend the rights

of innocent nonminority individuals in ostensibly remedying

past discrimination, and thus commend themselves to this

Court for resolution.

14 T he C ourt noted that the 1980 census reveals that the black population

is now 63% (App. 25a, n .41), and rem anded the case to the district court

in light of the new census figures. (App. 78a).

14

III. T H E D ECISIO N S BELOW C O N FL IC T

IN P R IN C IP L E W IT H B A K K E , W EBER

A N D F U L L IL O V E A N D SQ U A R E L Y

C O L L ID E W IT H T H E P R IN C IP L E

T H A T T H E NATURE OF T H E V IO LA

T IO N M U ST D E T E R M IN E T H E SCOPE

OF T H E REM ED Y .

The Sixth Circuit sustained a sweeping 50/50 quota which

places within the municipal “ area of discretion’ ’ (App. 192a)

the power to use racial preferences much broader than those

conferred under the remedial provisions of Title VII and the

permissible parameters of the Equal Protection Clause. If the

ruling below is not disturbed, major cities throughout the

country will, like Detroit, have (a) the power to impose class-

based racial preferences without regard to whether the benefi

ciaries are actual victims of past discriminatory practices;

(b) the ability to impose racial preferences on a racially neutral

merit and seniority system which would otherwise be pro

tected under § 703 (h) of Title VII; and (c) the ability to dis

regard procedural safeguard requirements for the protection

of individual rights and to distort the collective bargaining

system.

The result below contradicts the teachings of this Court,

which although not fully dispositive of all the issues presented

herein,15 nonetheless offer sound general principles with

which the decisions below conflict. The most obvious and fun

damental departure from established constitutional principles

15 Weber and Fullilove are distinguishable in im portant respects. For ex

am ple, Weber was lim ited in scope to a private, collectively bargained

plan which the C ourt em phasized did not implicate the Fourteenth

A m endm ent since no state action was involved, 443 US at 200; while

Fullilove involved an act of Congress, with broad, constitutionally derived

powers which provide unique authority to rem edy past discrim ination

based on carefully developed findings of fact. 448 US at 472-80.

15

is the standard of review adopted by the Sixth Circuit. In

Bakke, supra, Justice Powell, announcing the judgm ent of the

Court, clearly articulated the traditional “ strict scrutiny”

standard of review applicable to all governmentally imposed

racial classifications:

The guarantee of equal protection cannot mean one

thing when applied to one individual and something else

when applied to a person of another color . . . . Racial

and ethnic distinctions of any sort are inherently suspect

and thus call for the most exacting judicial examination.

438 US at 289-91.

M aintaining that “ the Supreme Court has failed to set out

a binding standard” (App. 10-1 la , n. 26), the Sixth Circuit

below flatly rejected strict scrutiny, choosing instead a “ rea

sonableness” standard, holding that:

One analysis is required when those for whose benefit

the Constitution was amended . . . claim discrimination.

A different analysis must be made when the claimants

are not members of a class historically subjected to

discrimination. (App. 11a).

Petitioners submit that this revisionist interpretation of the

Fourteenth Amendment not only dictated the result in the in

stant case, but also creates an alarming precedent by discard

ing the vital principle that “ if both are not accorded the same

protection, then it is not equal. Bakke, 438 US at 290.

Announcing the judgm ent of the Court in Fullilove, supra,

Chief Justice Burger confirmed that any “ preferences based

on racial or ethnic criteria must necessarily receive a most

searching examination . . . ” 448 US at 491; and Justices

Stewart, Rehnquist and Stevens clearly articulated the tradi

tional striet scrutiny standard in separate dissenting opinions.

Fullilove, 448 US at 526, 537. The Sixth Circuit disregarded

Fullilove, terming it “ a plurality decision with little preceden

tial value.” (App. 10a). Instead, the Court below explicitly

16

embraced concurring and dissenting opinions in Bakke and

Fullilove to ascertain applicable constitutional standards.

(App. 10a).

As applied below, this standard of “ reasonableness” per

mits the duration of the racial quota to be linked to achieving

racial parity with the general population rather than the rele

vant labor market of qualified “ minority members who would

have been employed (and promoted) by the governmental in

stitution in question in the absence of discrimination.” (M er

ritt, dissenting, App. 45a). While purporting to apply the

teachings of Weber, the Sixth Circuit remanded for recon

sideration of the 50% quota in view of the general population

figure of 63% in the 1980 census. (App. 78a). This contrasts

sharply with Weber, wherein preferential selection of craft

trainees terminates as soon as the percentage of skilled black

craft-workers approximates the number of minorities in the

relevant labor market. 443 US at 209. Indeed, in a separate

opinion dissenting from the denial of rehearing en banc, Circuit

Judge Wellford emphasized “ that the District Court, in ap

proving the affirmative action program in question, inap

propriately considered the racial breakdown of the Detroit

population as a whole instead of the racial breakdown of the

applicable qualified labor pool.” (App. 79a).16

This Court has specifically noted the limited probative

value of general population figures where the population at

large does not possess the requisite qualifications for the job in

question. Hazelwood School District v. United States, 433 US 299

This difference is substantial. Although the general population was

50% black in 1974, the C ity ’s relevant labor m arket expert estim ated that

absent discrim ination there should have been 43 black lieutenants in

1974 out of a total o f 232 lieutenants, a ratio of only 19% . The C ourt of

Appeals does not mention this finding, but com pare the num ber of

lieutenants in the table in the opinion at App. 17a with the district court’s

findings at App. 143a.

17

(1977); In t’l Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United States, 431 US

324, 399 (1977). As the Court stated in Hazelwood,

W hen special qualifications are required to fill particular

jobs, comparisons to the general population (rather than

to the smaller group of individuals who possess the

necessary qualifications) may have little probative value.

433 US at 308, n. 13.

The Sixth Circuit flatly misconstrued Hazelwood, con

cluding without any qualification that “ [tjhe Supreme Court

has approved the use of racial composition comparisons be

tween employers work forces and general area-wide popula

tion as probative of discrimination in employment discrimina

tion cases . . .” (App. 32a). This misconstruction of Hazelwood

permitted the Sixth Circuit to sustain the Board’s use of

general population figures in fashioning its 50/50 quota,

noting with approval that the Board in choosing this figure

had ‘ ‘ simply concluded that most police officers in the past had come

from within the City and that the City was now approximately fifty per

cent black.’’ (App. 25a, emphasis in original).17

As Justice Powell made clear in Bakke, 438 U.S. at 307, the

goal of achieving ‘ ‘ some specified percentage of a particular

group merely because of its race or ethnic origin’ ’ is not con

stitutionally permissible and constitutes discrimination for its

own sake. This Court has emphasized that there is neither a

constitutional necessity nor right to create balances, Milliken v.

Bradley, 418 US 717, 740-741 (1974), and the goal of racial

balancing as a remedy has been specifically rejected by the

Court. See Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenberg Bd. of Education, 402

US 1, 24 (1971). O n the contrary, where past discrimination

is to be remedied, “ the nature of the violation determines the

scope of the rem edy.’’ Id at 16.

17 It seems obvious that a police force of mostly thirty-year career officers

cannot possibly keep pace with rapidly changing demographics that went

from 16% black in 1950 to 63% black in 1980.

18

Instead of determining whether the racial preferences were

“ precisely tailored” to remedy past discrimination, the Sixth

Circuit embraced the use of a racial quota as a form of

‘ ‘ redress . . . to the black population as a whole. ’ ’ (App. 31a),

Referring specifically to past discrimination in employment, the

Sixth Circuit held that “ we do not believe that marginally in

creasing the percentage of black lieutenants above the figure that

would exist had hiring been non-discriminatory is an unreasonable

remedy for redressing this w rong.’’ {Id, emphasis added).

No authority is cited for this “ redress” rationale, which

conflicts with established case law. Such “ cum ulative”

remedies were specifically rejected in Dayton Bd. of Educ. v.

Brinkman, 433 US 406 (1977), in which the Court instructed

that race-conscious remedies may only be designed to redress

the difference between the status quo and that which would ex

ist absent past discrimination, based on specific fact findings.

A permissible remedy must be carefully designed to correct

past discrimination with due regard for the individuals

adversely affected by the remedy. Accordingly, when racial

classifications impinge upon individual rights, the individual

is entitled to a “ determination that the burden he is asked to

bear on that basis is precisely tailored to serve a compelling

governmental interest.” Bakke, 438 US at 299. In Fullilove,

this requirement was satisfied by the existence of procedural

safeguards insuring that “ the use of racial and ethnic criteria

is premised on assumptions rebuttable in the administrative

process. ’’ 448 US at 489. Contrast the instant case, in which the

courts below sustained the abrogation of existing procedural

safeguards specified in § 7-1114 of the Detroit City Charter,

providing that ‘ ‘ any person having been passed over (for pro

motion) may appeal to the Board.” (J.A . 1519). The district

court brushed aside the lack of procedural due process in the

19

Board’s systematic denial of a hearing to individual victims of

the racial preferences, declaring that:

[t]he purpose of individual appeals is to hear individual

grievances. The white officers who were bypassed by af

firmative action were complaining about Board Policy,

not an injustice unique to them as individuals. (App.

218a).

The quota thus contains no procedural safeguards to insure

that beneficiaries are victims of past discrimination, nor does

it preclude unjust penalization of innocent individuals.18 As a

result, the Sixth Circuit, in sustaining this class-based quota,

effectively rejected Chief Justice Burger’s warning against any

“ program which seeks to confer a preferred status upon a

non-disadvantaged m inority,” Fullilove, 448 US at 485; as

well as the requirement that race-conscious affirmative action

programs must be carefully tailored so that they do not “ stray

from narrow remedial justifications.” Id at 487.

This Court has specifically noted that the “ principal focus”

of Title V II “ is the protection of the individual employee,

rather than . . . the minority group as a whole.” Connecticut v.

Teal, 457 US 440, 453-54 (1982), and that remedial efforts

must be “ necessarily designed . . . to restore the victims of

discriminatory conduct to the position they would have oc

cupied absent such conduct.” Milliken v. Bradley, 418 US at

746. Indeed, Title VII expressly prohibits courts from order

ing specific affirmative relief for persons who were not actual

18 O ne individual m em ber of the P laintiff class observed over a period of

tim e several individual black sergeants who were first prom oted to lieu

tenant ahead of him , and who were later prom oted to inspector. (J.A .

236). A t the same time, other individuals were passed over for prom otion

not once, but two or three times. (J.A . 65).

20

victims of past discrimination. Franks v. Bowman Transportation

Co., 424 US 747, 774 (1976).19

As a class-based “ remedy” the 50/50 quota inherently

favors some persons who have never been hindered by dis

crim inatory employment practices,20 yet these same in

dividuals are preferred over other individuals in the context of

a merit examination that otherwise provides an equal oppor

tunity for each candidate to compete for promotion. This

equality of opportunity is consistent with equal protection,

“ for once an environment where merit can prevail exists,

equality of access satisfies the demand of the Constitution.”

NAACPv. Allen, 493 F 2d 614, 621 (5th Cir, 1974).

O n this point, the E .E .O .C . instructs that the proper pur

pose of an affirmative action program “is to overcome previous ex

clusion, rather than merely to achieve numerical ‘parity .’”

E .E .O .C ., Eliminating Discrimination in Employment, supra, at

III-3 (emphasis in original). The Civil Rights Commission

warns further that race-balancing quotas improperly change

“ the objectives of affirmative action plans from dismantling

discriminatory processes to assuring that various groups

receive specified percentages of resources and opportunities. ’ ’

19 The district court claimed that identification of actual victims of

discrim ination is impossible in the instant case (App. 155a), yet proceed

ed to illustrate several particular cases in point, dem onstrating that said

efforts are indeed feasible. (156a).

20 T o the contrary, some individual beneficiaries of the lieutenants quota

also benefitted from the same preference in prom otions from patrolm an

to sergeant. (J .A . 1661, 1686, 1871).

21

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, Affirmative Action in the

1980’s, supra, at 31.21

Finally, while the Sixth Circuit purports to apply the

teachings of Weber, it glosses over the role of the collective

bargaining agreement which constituted the voluntary affirm

ative action plan upheld in that case. See, 443 US at 197. The

instant case, conversely, involves a racial quota for promo

tions unilaterally imposed on a bona fide equal opportunity

merit system in derogation of the state law obligation to

bargain, and which includes procedural safeguards of the type

described in Fullilove.22

The decision below therefore conflicts with important con

stitutional principles as well as statutory parameters beyond

which racial quotas may not be considered “ benign” in any

real sense. Yet, in the absence of definitive guidance from this

Court, the decisions below are necessarily viewed as the state

of the law on these issues.23 It is therefore vital that this Court

review the statements of law decided below.

21 This C ourt has recognized that Congress, in § 703(h) of T itle V II,

specifically intended to protect seniority systems from being distorted by

racial preferences. See, In t’l Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United States, 431 US

324 (1977). On its face, § 703(h) also protects “ professionally developed”

merit systems such as the promotional process in the instant case. 42 USC

§ 2000e-2(h).

22 Unlike Fullilove, which involved an Act of Congress based on broad

constitutionally derived powers, the City of D etroit is a public entity in

com petent to make unilateral decisions regarding police prom otions

under the collective bargaining requirem ents of M ichigan law {see,

PE R A, supra, n . l) . A nd unlike the carefully developed findings of fact in

Fullilove, 448 US at 472-80, the B oard’s “ fact findings” were limited to

one public m eeting and no formalized findings of past discrim ination.

( J . A. 1129-31).

23 See, e.g. Schlei & G rossm an, Employment Discrimination Law, 854-62 (2d

ed 1983).

2 2

IV. THE CASE IS RIPE FOR REVIEW AND

PRESENTS A FULLY DEVELOPED

RECORD FOR THIS COURT TO DECIDE

APPROPRIATE STANDARDS FOR THE

REMEDIAL USE OF RACIAL PREFER

ENCES IN PUBLIC EMPLOYMENT.

In contrast to the unsettled records and procedural prob

lems in other similar cases that have come before this C ourt,24

this case presents to the Court a final Court of Appeals deci

sion based on a fully developed record. Issues fully developed

in the record evidence include:

(1) a comprehensive relevant labor market analysis

derived from a laborious count of actual applications for

employment with the Department over a three-year period,

1971-1973;

(2) an analysis of the competitive merit selection ex

amination process, with findings on the selection rates of

that process concurred in by experts for both sides;

(3) a detailed history of the affirmative action effort in

the Department commencing in 1967 with special recruit

ment efforts and the elimination of disproportionate stan

dards, and progressing through the use of racial preferences

for hiring and, finally, in promotions;

24 For example, in Minnick v. California Department of Corrections, 452 US

105 (1981), the state court decision was held not final and certiorari was

dismissed. In Detroit Police Officers A ss’n v. Young, supra, n. 3, the record

was unsettled because the Sixth C ircuit reversed the district court’s deci

sion holding the racial preferences for prom otion to sergeant unconstitu

tional, and rem anded for a new trial under standards inconsistent with

the opinion.

23

(4) studies and testimony from police professionals on

the question of race as a bona-fide occupational qualifica

tion in a modern police department; and

(5) on the issue of “ benign” discrimination, expert

testimony and the testimony of several individual members

of the Plaintiff class, including their experiences and feel

ings in dealing with the racial preferences.

The record is thus one on which this Court may solidly base a

decision regarding the permissible parameters of municipal

racial preferences in public employment.

24

CONCLUSION

The instant case presents im portant and topical issues of

vital nationwide significance, in a m anner ripe for resolution.

It is respectfully urged that this Court agree to hear this case

and resolve the questions presented herein.

Respectfully submitted,

R a m s d e l l , O a d e & F e l d m a n

/s / K. Preston Oade, J r . (P28506)

Counsel of Record for Petitioners

25130 Southfield R d., Ste. 100

Southfield, Michigan 48075

(313) 552-9400

M o u n t a in S t a t e s L e g a l F o u n d a t io n

by: Fred D. Fagg, III

William H. Mellor III

Clint Bolick

Co-Counsel

1200 Lincoln Street, Ste. 600

Denver, Colorado 80203

(303) 861-0244

Dated: September 30, 1983