Ross v Radich Brief in Opposition to Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

June 8, 1972

15 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Ross v Radich Brief in Opposition to Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1972. cb7e494f-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1c56b56e-8edc-4156-9516-12ce3dc5f323/ross-v-radich-brief-in-opposition-to-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

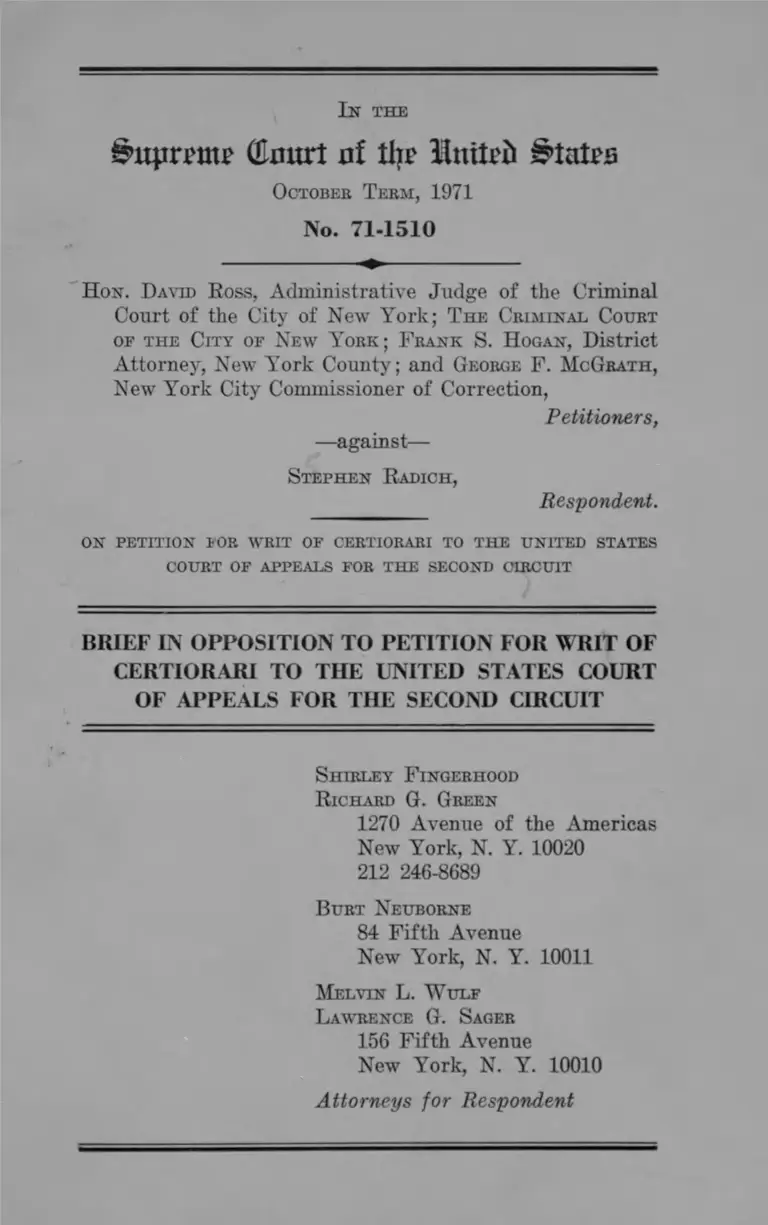

i>u;irrmp (Emtrt of tljr Iniirii Stairs

October Term, 1971

No. 71-1510

In the

H on. David Ross, Administrative Judge of the Criminal

Court of the City of New York; T he Criminal Court

of the City of New Y ork; F rank S. H ogan, District

Attorney, New York County; and George F. McGrath,

New York City Commissioner of Correction,

—against—

Petitioners,

Stephen Radich,

Respondent.

ON PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO PETITION FOR WRIT OF

CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT

OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

Shirley F ingerhood

R ichard G. Green

1270 Avenue of the Americas

New York, N. Y. 10020

212 246-8689

Burt Neuborne

84 Fifth Avenue

New York, N. Y. 10011

Melvin L. W ulf

Lawrence G. Sager

156 Fifth Avenue

New York, N. Y. 10010

Attorneys for Respondent

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Opinions B elow ................................................................. 1

Jurisdiction ....................................................................... 1

Questions Presented ........................................................ 2

Statutes Involved .............................................................. 2

Statement ........................................................................... 4

Reasons for Denying the W rit ....................................... 6

I. There is no important question of Federal law

and no conflict of decision................................... 6

II. The decision below is clearly correct and in ac

cordance with applicable decisions of this Court 8

Conclusion ................................................................................... 11

Table oe Cases

Neil v. Biggers,------U.S. — , 40 U.S.L.W. 3410, 3415

(1972) ............................................................................. 7

Ohio ex rel. Eaton v. Price, 364 U.S. 263 (1960) ...........9-10

People v. Radich, 53 Misc.2d 717, 279 N.Y.S.2d 680

(Crim. Ct. 1967); 57 Misc.2d 1082, 294 N.Y.S.2d 285

(App. T. 1968); 26 N.Y.2d 114, 308 N.Y.S.2d 846, 257

N.E.2d 30 (1970) 4

PAGE

Radich v. New York, 400 U.S. 864 (1970); 401 U.S. 531

(1971); 402 U.S. 989 (1971) ....................................... 4, 5

United States ex rel. Biggers v. Neil, 448 F.2d 91 (6th

Cir. 1971) ...................................................................... 7

Statutes:

Penal Law, New York Section 1425 Snbd. 16(d) (Now

Gen. Bus. Law, Section 136(d)) ................................. 4

28 U.S.C. Section 1254(1) ................................................. 1

2109 ........................................................................2,3, 5,7

2241 et seq............... .................................................. 5

2244(c) ..............................................................2, 5, 6,7,8

U. S. Constitution:

First Amendment...................................................... 4

Fourteenth Amendment ........................................... 4

11

In the

£>ttprmp (Hmtrt of the lotteh States

October Term, 1971

No. 71-1510

H on. David E oss, Administrative Judge of the Criminal

Court of the City of New York; T he Criminal Court

of the City of New Y ork ; F rank S. H ogan, District

Attorney, New York County; and George F. M cGrath,

New York City Commissioner of Correction,

—against—

Petitioners,

Stephen E adich,

Respondent.

o n p e t i t i o n f o r w r i t o f c e r t io r a r i t o t h e u n i t e d s t a t e s

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENT IN OPPOSITION

Opinions Below

The opinion of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Second Circuit (Appendix “A ” of Petition) is not yet

reported. The opinion of the United States District Court

for the Southern District (Appendix “B” of Petition) is

not yet reported.

Jurisdiction

Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under Title 28

U.S.C. §1254(1).

2

Questions Presented

1) Whether an equal division of this Court which results

in an affirmance of a State court conviction is an actual

adjudication of Federal constitutional issues within the

meaning of 28 U.S.C. Section 2244(c) and bars considera

tion of those issues in a habeas corpus proceeding?

2) Whether 28 U.S.C. Section 2109, which requires that

where the Supreme Court lacks a quorum it affirm the judg

ment of the court below “with the same effect as upon

affirmance by an equally divided court,” demonstrates the

intent of Congress to exclude such affirmances from the

conclusive presumption given only to actual adjudications

under 28 U.S.C. 2244(c) ?

Statutes Involved

Section 2244(c) of Title 28 of the United States Code:

(c) In a habeas corpus proceeding brought in behalf

of a person in custody pursuant to the judgment of

a State court, a prior judgment of the Supreme Court

of the United States on an appeal or review by a writ

of certiorari at the instance of the prisoner of the de

cision of such State court, shall be conclusive as to all

issues of fact or law with respect to an asserted denial

of a Federal right which constitutes ground for dis

charge in a habeas corpus proceeding, actually ad

judicated by the Supreme Court therein, unless the

applicant for the writ of habeas corpus shall plead

and the court shall find the existence of a material and

3

controlling fact which did not appear in the record of

the proceeding in the Supreme Court and the court

shall further find that the applicant for the writ of

habeas corpus could not have caused such fact to

appear in such record by the exercise of reasonable

diligence.

Section 2109 of Title 28 of the United States Code:

If a case brought to the Supreme Court by direct

appeal from a district court cannot be heard and

determined because of the absence of a quorum of

qualified justices, the Chief Justice of the United

States may order it remitted to the court of appeals

for the circuit including the district in which the case

arose, to be heard and determined by that court either

sitting in banc or specially constituted and composed

of the three circuit judges senior in commission who

are able to sit, as such order may direct. The decision

of such court shall be final and conclusive. In the event

of the disqualification or disability of one or more of

such circuit judges, such court shall be filled as pro

vided in chapter 15 of this title.

In any other case brought to the Supreme Court for

review, which cannot be heard and determined because

of the absence of a quorum of qualified justices, if a

majority of the qualified justices shall be of opinion

that the case cannot be heard and determined at the

next ensiling term, the court shall enter its order affirm

ing the judgment of the court from which the case was

brought for review with the same effect as upon affirm

ance by an equally divided court.

4

Statement

Respondent Stephen Radich was convicted in the Crimi

nal Court of the City of New York on May 5,1967 of casting

contempt on the American flag in violation of what was

then Section 1425(16) (d) of the New York Penal Law,

now Section 136(d) of the New York General Business Law.

Radich’s conviction was based upon an exhibition of

certain sculptures termed “constructions” in his second

floor art gallery. People v. Radicli, 53 Misc. 2d 717, 279

N.Y.S.2d 680 (1967). He was sentenced to pay a $500

fine or serve 60 days in the workhouse.

The Appellate Term, First Judicial Department, of the

Supreme Court of the State of New York affirmed without

opinion (57 Misc. 2d 1082, 294 N.Y.S.2d 285 (1968)). The

New York Court of Appeals affirmed the conviction on

February 8, 1970, 26 N.Y.2d 114, 308 N.Y.S.2d 846, by a

5-2 vote.

Radich then appealed to the Supreme Court of the United

States on May 18, 1970. Probable jurisdiction was noted

on October 19, 1970. Radicli v. New York, 400 U.S. 864.

Before this Court he argued, as he had in the State courts,

that his conviction violated the First and Fourteenth

Amendments to the Federal Constitution for reasons, inter

alia, that the statutory prohibition against casting contempt

on the flag violated the First Amendment because to “ cast

contempt” means to communicate an idea or attitude and

the statute therefore is directed specifically against com

munication. He also argued that the statute under which

he was convicted was overbroad and violated the equal

protection clause.

5

This Court “affirmed by an equally divided Court” ,

Radich v. New York, 401 U.S. 531 (1970), Mr. Justice

Douglas not participating. Thereafter Eadich applied for

a writ of habeas corpus in the United States District Court

for the Southern District of New York pursuant to 28

U.S.C. §2241 et seq. The Court, by Canella, J., denied re

lief on the ground that 28 U.S.C. §2244(c) barred federal

habeas corpus relief because the equally divided Supreme

Court affirmance of the State court conviction constituted

an actual adjudication of the merits of the constitutional

claims then before the District Court.

The United States Court of Appeals for the Second Cir

cuit granted a stay on January 4, 1972 and reversed the

District Court’s decision on April 26, 1972. The Court

held that an affirmance by an equally divided vote was not

an actual adjudication by the Supreme Court within the

meaning of §2244(c). The Court of Appeals ruled that the

Supreme Court was unable to reach a decision on the

constitutional issues because of its equal division and thus

the State court’s decision remained in effect because there

has been no federal adjudication of Eadich’s Federal con

stitutional rights.

The Court cited another provision of the Judicial Code,

28 U.S.C. §2109, as corroboration of Congress’s view that

a 4-4 decision by this Court is not an actual adjudica

tion of constitutional claims within the purview of §2244(c).

Section 2109 provides that when a case on review from a

State court cannot he decided by the Supreme Court be

cause of the lack of a quorum, “ the court shall enter its

order affirming the judgment of the court from which the

case was brought for review with the same effect as upon

affirmance by an equally divided court.”

6

The Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit reversed

and remanded to the District Court for consideration of

the constitutional claims raised by the petition.

REASONS FOR DENYING THE WRIT

I.

There is no important question of Federal law and no

conflict of decision.

The issue in the present case is, in the words of the Court

of Appeals, “unlikely to recur” (2a)* and is too narrow to

warrant review by this Court on certiorari. It can arise

only in those few cases where a writ of habeas corpus is

sought by a person whose State court conviction has been

affirmed as a result of an equal division of this Court. The

Court below found only six examples of equal division by

this Court upon appeals from State court convictions since

1960.

The case does not in any sense broadly concern the

habeas corpus jurisdiction of the Federal courts. It in

volves only the application of §2244(c) of the Judicial

Code, which bars consideration in habeas corpus proceed

ings of issues which have been actually adjudicated by the

Supreme Court in a prior appeal by the petitioner, in the

unusual situation where the Supreme Court has been un

able to reach a decision on such issues because it is equally

divided.

To focus precisely on the dimensions of the issue pre

sented for Supreme Court consideration, it may be pointed

* Numbers in parentheses refer to the Appendix to the petition.

7

out that petitioners ask this Court to decide that its fail

ure to reach agreement on a case is an actual adjudication,

or real decision, of the issues presented by the appeal.

There is no conflict of decisions on this narrow issue.

Two Courts of Appeal—for the Second Circuit in this case,

and for the Sixth Circuit in Neil v. Biggers, 448 F.2d 91

(6th Cir. 1971) cert, granted------U.S. ------- , 40 U.S.L.W.

3410, 3415 (1972)—have ruled squarely that a 4-4 decision

is not an actual adjudication of issues within the meaning

of §2244(c) of the Judicial Code and does not bar a con

sideration of the same issues in a habeas corpus proceed

ing.

The writ of certiorari was granted in Neil v. Biggers

when the District Court decision in respondent’s case was

pending on appeal to the Court of Appeals. At that time

there was a possibility of a conflict between decisions of

Courts of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit and for the Second

Circuit. That possibility has been eliminated by the deci

sion below; the circuits are now in accord. Petitioner there

fore respectfully requests that the Court consider dismiss

ing the writ of certiorari in Biggers, as well as denying

the petition herein.*

In addition, the opinion of the Court below in the instant

case cites a statute, Section 2109 of the Judicial Code, which

respondent believes was not brought to the attention of

this Court when it considered the application for a writ

of certiorari in Biggers. 28 U.S.C. §2109, provides that

in certain instances when a case on review in the Supreme

* Respondent is, of course, aware that this is not the only issue

raised in the petition for writ of certiorari in Biggers and accord

ingly, his request does not relate to the other issue.

8

Court cannot be decided because of the absence of a quorum

of qualified justices “ the court shall enter its order affirm

ing the judgment of the court from which the case was

brought for review with the same effect as upon affirmance

by an equally divided court.”

The use by Congress of an affirmance by an equally di

vided Court as the analogy for final disposition by affirm

ance when this Court cannot sit on an appeal, was cited

by the Court below as corroboration of Congressional in

tention that only a majority decision of this Court would

bar consideration of Federal claims in a habeas corpus pro

ceeding.

II.

The decision below is clearly correct and in accordance

with applicable decisions of this Court.

After a review of Congressional enactments authorizing

Federal courts to entertain writs of habeas corpus by per

sons convicted in State court proceedings, the Court below

concluded that in enacting Section 2244(c) Congress did

not intend to deprive the habeas petitioner of his right to

one federal adjudication of Federal constitutional issues

merely because those issues had been previously raised

before the Supreme Court. “Only if the Supreme Court

had actually decided the issues would its adjudication be

final” . (8a). (Emphasis in original.) Since the very fact

of an equal division meant that the Supreme Court was un

able to reach such a decision, the Court held that under

such circumstances there had been no adjudication of the

issues.

9

In addition, the Court below stated:

That Congress does not consider an affirmance by an

equally divided court to be an actual adjudication of the

merits is corroborated by its enactment of another pro

vision of the Judicial Code, 28 U.S.C. §2109, which

provides that in certain instances when a case on re

view in the Supreme Court cannot be decided because

of the absence of a quorum of qualified justices “ the

court shall enter its order affirming the judgment of

the court from which the case was brought for review

with the same effect as upon affirmance by an equally

divided court.” (Emphasis added.) See e.g., Prichard

v. United States, 339 U.S. 974 (1950). This provision

was enacted to allow final disposition of litigation when

“ appellate review has been had and further review by

the Supreme Court is impossible. . . . ” H.K. Hep. No.

308, 80th Cong., 1st Sess. A176 (1947). (9a).

Petitioners argue only that an affirmance by an equally

divided Court constitutes an actual adjudication of the

issues raised before the Court, first, because such affirm

ances are conclusive and binding upon the parties in civil

cases; and second, because such affirmances differ from

denials of writs of certiorari, which the legislative history

of the subsection excepts from its purview.

The Court below properly rejected those arguments.

Pointing out that the conclusive and binding effect of affirm

ances by an equally divided Supreme Court in civil actions

is irrelevant to a habeas corpus proceeding, the Court of

Appeals noted the statement that where there is an equal

division “ ‘nothing is settled’ by the Court, Ohio ex rel.

10

Eaton v. Price, 364 U.S. 263, 264 (1960) (opinion of Mr.

Justice Brennan).” (10a).

Petitioners’ second contention conflicts with their first:

if civil cases are relevant, then it must be noted that the

denial of a writ of certiorari in a civil case leaves in effect

a judgment as final and binding upon the parties as a

4 to 4 affirmance. When neither party to a civil action peti

tions for a writ of certiorari, the judgment in effect is

equally conclusive and binding. Yet habeas corpus is avail

able to a criminal defendant whose petition for a writ of

certiorari from a state conviction is denied or who does not

petition for such a writ.

In review of the foregoing, the decision of the Court be

low is correct and accords with decisions of this Court with

respect to its equally divided affirmances.

11

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons it is respectfully submitted

that this petition for a writ of certiorari should be

denied.

Dated: New York, N. Y.

June 8, 1972

Respectfully submitted,

Shirley F ingerhood

R ichard G. Green

1270 Avenue of the Americas

New York, N. Y. 10020

212 246-8689

Burt Neuborne

84 Fifth Avenue

New York, N. Y. 10011

Melvin L. W ulf

Lawrence G. Sager

156 Fifth Avenue

New York, N. Y. 10010

Attorneys for Respondent

RECORD PRESS, INC., 95 MORTON ST., NEW YORK, N. Y. 10014— (212) 243-5775

10608 CROSSING CREEK RD„ POTOMAC, MD. 20854— (301) 299-7775

38