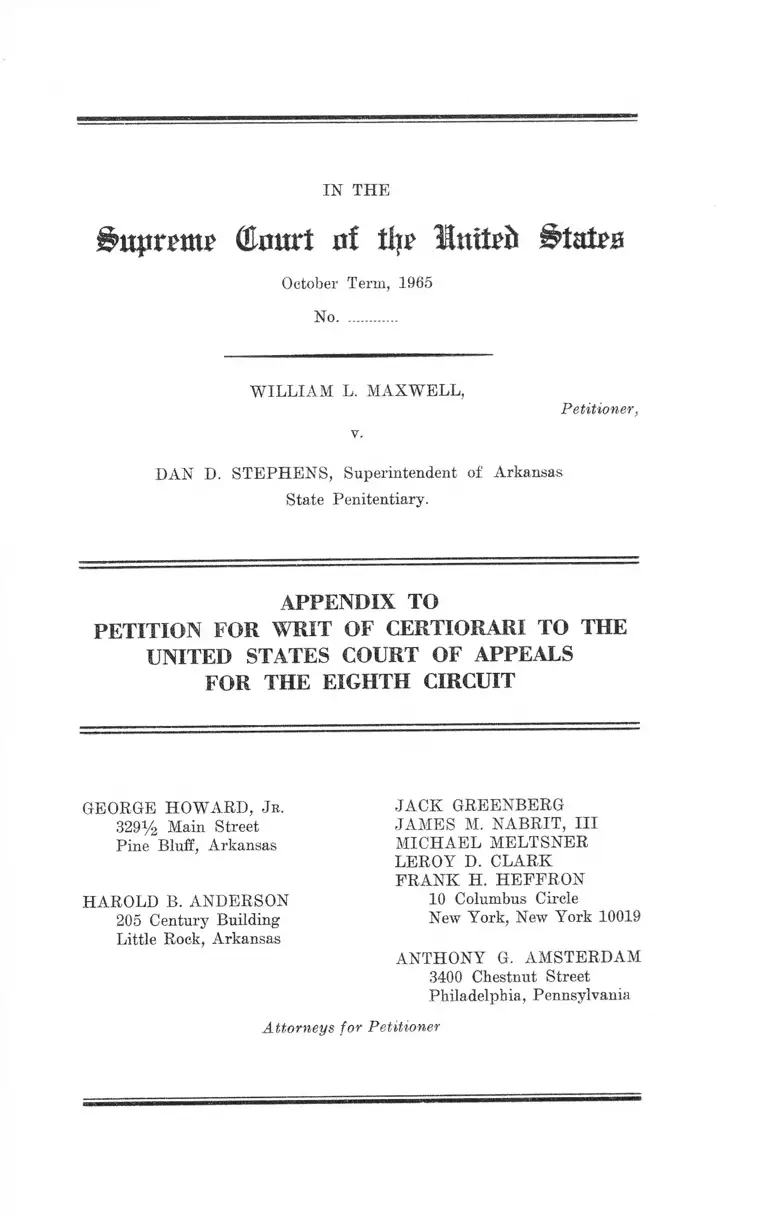

Maxwell v. Stephens Appendix to Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

June 30, 1965

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Maxwell v. Stephens Appendix to Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1965. e18ad34a-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1c5c7616-8836-4da1-9a3c-f99c206552c6/maxwell-v-stephens-appendix-to-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

Supreme Okmrt ai tlje States

October Term, 1965

No. ............

WILLIAM L. MAXWELL,

v.

Petitioner,

DAN D. STEPHENS, Superintendent of Arkansas

State Penitentiary.

APPENDIX TO

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

GEORGE HOWARD, Jr.

3291/2 Main Street

Pine Bluff, Arkansas

HAROLD B. ANDERSON

205 Century Building

Little Rock, Arkansas

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

MICHAEL MELTSNER

LEROY D. CLARK

FRANK H. HEFFRON

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

ANTHONY G. AMSTERDAM

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Attorneys for Petitioner

I N D E X

PAGE

Judgment of Court of Appeals ..................................... - la

Opinion of Court of Appeals .... ...................................... 2a

Opinion of District Court ............................... ................ 30a

Opinion of Supreme Court of Arkansas ....................... 55a

Initeti g ’tatra ffinurt of Apprala

F ob t h e E ig h t h C ib c u it

No. 17,729

September Term, 1964

W il l ia m L. M a x w e l l ,

vs.

Appellant,

D an D. S t e p h e n s , Superintendent of Arkansas

State Penitentiary.

APPEAL FBOM THE UNITED STATES DISTBICT COUBT FOB THE

EASTERN DISTBICT OF ARKANSAS

Judgment of Court of Appeals

This cause came on to be heard on the original files of

the United States District Court for the Eastern District

of Arkansas, and was argued by counsel.

On Consideration Whereof, It is now here Ordered and

Adjudged by this Court that the Order of the said District

Court entered May 6th, 1964 in this cause, denying peti

tion for writ of habeas corpus be, and the same is hereby,

affirmed, in accordance with majority opinion of this Court

this day filed herein.

June 30, 1965.

Order entered in accordance

with majority opinion:—

R obert C. T u c k e r

Clerk, U. S. Court of Appeals

for the Eighth Circuit.

2a

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

F ob t h e E ig h t h : C ir c u it

Opinion of Court of Appeals

No. 17,729

W il l ia m L. M a x w e l l ,

v.

Appellant,

D an D. S t e p h e n s , Superintendent of Arkansas

State Penitentiary,

Appellee.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

EASTERN DISTRICT OF ARKANSAS

[June 30, 1965.]

Before M a t t h e s , B l a c k m u n , and R idge , Circuit Judges.

B l a c k m u n , Circuit Judge.

William L. Maxwell, a Negro possessing an eighth grade

education, stands convicted by a jury in the Circuit Court

of Garland County, Arkansas, of the crime of rape, as de

fined by § 41-3401, Arkansas Statutes 1947. The offense

was committed on November 3, 1961. Maxwell at the time

was 21 years of age. The jury did not “render a verdict

3a

of life imprisonment in the State penitentiary at hard

labor” , as it had the right to do under §§ 43-2153 and

41-3403, and for which it had been given an alternate ver

dict form. As a consequence, and in line with the inter

pretation consistently given § 43-2153 by the Supreme

Court of Arkansas,1 the death sentence was imposed. On

appeal the conviction was affirmed. Maxwell v. State, 236

Ark. 694, 370 S.W.2d 113 (1963).1 2

Four days before the execution date which was fixed

following that unsuccessful appeal Maxwell filed a petition

for a writ of habeas corpus in the United States District

Court for the Eastern District of Arkansas. Judge Young

conducted a hearing on the federal constitutional issues

raised by that petition. Briefs were filed. The court

wrote a detailed opinion denying the relief requested,

Maxwell v. Stephens, 229 F.Supp. 205 (E.D. Ark. 1964),

but then granted Maxwell’s petition for a certificate of

probable cause, as contempla ted by 28 U.S.C. § 2253, and

further stayed execution.

Except for an early period prior to the state trial when

court appointed attorneys were in the case, Maxwell has

been represented through all the state and federal pro

ceedings by competent, although different, non-court-ap

pointed counsel.

1 Kelley v. State, 133 Ark. 261, 202 S.W. 49, 54 (1918); Bullen v. State,

156 Ark. 148, 245 S.W. 493, 494 (1922); Clark v. State, 169 Ark. 717, 276

S.W. 849, 853-54 (1925); Smith v. State, 205 Ark. 1075, 172 S.W.24 248,

249 (1943); Turner v. State, 224 Ark. 505, 275 S.W.2d 24, 31 (1955);

Stewart v. State, 233 Ark. 458, 345 S.W.2d 472, 475 (1961), cert, denied

368 U.S. 935.

2 No petition for certiorari was filed with the Supreme Court of the

United States. This of course no longer constitutes a failure to exhaust

available state remedies. Fay v. Noia, 372 U.S. 391, 435-38 (1963); Curtis

v. Boeger, 331 F.2d 675 (8 Cir. 1964).

Opinion of Court of Appeals

4a

We note, as we have noted before in other cases of this

type,8 that Maxwell’s guilt or innocence is not in issue

before us. This is still another situation where, as the

United States Supreme Court described the posture of an

earlier Arkansas case, “ . . . what we have to deal with

is not the petitioners’ innocence or guilt but solely the

question whether their constitutional rights have been

preserved” . Moore v. Dempsey, 261 U.S. 86, 87-88 (1923).

The circumstances and details of the crime are, as

usual, sordid. They are set forth in the Arkansas opin

ion, pp. 114-16 of 370 S.W.2d, and need not be repeated

here. It suffices only to say that the victim was a white

woman, 35 years old, who lived with her helpless ninety-

year-old father; that their home was entered in the early

morning by the assailant’s cutting or breaking a window

screen; that in the ensuing struggle the victim bit her

assailant and caused bleeding; and that she was assaulted

and bruised, her father injured, and the lives of both

threatened. Confessions taken from Maxwell were not

employed at the trial. The defense presented no evidence.

The jury was out several hours. No question is raised as

to the sufficiency of the evidence.

On this habeas corpus appeal Maxwell presses three

issues:3 4 * (1) he was denied due process of law and the

3 Bailey v. Henslee, 287 F.2d 936, 939 (8 Cir. 1961), cert, denied 368

U.S. 877; Henslee v. Stewart, 311 F.2d 691, 692 (8 Cir. 1963), cert, denied

373 U.S. 902.

4 Other issues urged in the district court, see pp. 208-09 and 211-12 of

229 F.Supp., but abandoned on this appeal, were the legality of Maxwell’s

arrest, the denial of a motion for change of venue, the validity of con

fessions taken from him, and the legality of a search of his person and

of the clothing which he was wearing. This search produced or revealed

a hair, a nylon thread, and blood and seminal stains which tended to

identify him as the intruder-assailant.

Opinion of Court of Appeals

equal protection of the laws, guaranteed by the Fourteenth

Amendment, because he was sentenced under statutes

wThich are discriminatorily enforced against Negroes; (2)

he was denied due process and equal protection because

the Garland County jury lists revealed race and were

compiled from racially designated poll tax books; and (3)

the taking of his coat while he was in custody, and refer

ences to it in testimony at the trial,5 violated rights guar

anteed to him under the Fourth, Fifth, and Fourteenth

Amendments.

A. The statute’s enforcement. The argument here is

that § 41-3403, which prescribes the death penalty for

rape, and § 43-2153, which, since its enactment as Acts

1915, No. 187, § 1, permits a jury in a death punishment

case to render a verdict of life imprisonment, although

perhaps constitutionally valid on their face, have been

discriminatorily enforced against members of the Negro

race and in favor of members of the white race. It is

claimed that in practice “ Negroes remain liable to the

supreme penalty for the crime of rape, but whites, with

very rare exceptions, suffer lesser punishments” ; that

“there is reason to believe that every person suffering

the death penalty has been convicted of a crime against

a white woman” ; that “All but two of the men executed

for rape since 1913 have been Negroes” ; that Negro de

fendants are more likely to be sentenced to death and 6

6 No point is apparently made about the fact the eoat itself (despite

a contrary statement in the Maxwell brief) was not introduced in evi

dence. In view of this, we do not raise the point on our own accord.

We assume that, for present purposes, questions of admissibility are as

applicable to testimony concerning the coat as to the coat itself. McGinnis

v. United States, 227 F.2d 598, 603 (1 Cir. 1955); Williams v. United

States, 263 F.2d 487, 488-89 (D.C. Cir. 1959). See Silverthorne Lumber

Co. v. United States, 251 U.S. 385, 391-92 (1920), and Wong Sun v. United

States, 371 U.S. 471, 484 (1963).

5a

Opinion of Court of Appeals

6a

only white women are protected by the deterrence of the

supreme penalty; that in Garland County (Hot Springs),

Pulaski County (Little Rock), and Jefferson County (Pine

Bluff), in the decade beginning January 1, 1954, only

three charges were lodged against white men for the rape

of Negro women; that one of these resulted in an acquit

tal and the other two in reduced charges; that in the

same period seven Negroes were charged with raping

white women; that of these, two were sentenced to death,

three to life imprisonment, one dismissed, and one n.ot

apprehended; that “ This history raises serious doubts

about the fairness of Arkansas’ system of criminal jus

tice” ; that the figures are not to be explained by the pro

portion of Negroes in the state’s total population nor by

any claim that the crime rate is higher among Negroes,

for in the three counties about two-thirds of the rape

charges were against white persons; that the proportion

of Negroes who receive the death penalty “ cries out for

an explanation” ; that race is the answer; and that the

state should be required to come forward with a rational

explanation.

It is further argued that there is no basis for assuming

a Negro’s victims have better character than the victims

of whites; that differing sentences for Negroes and whites

are consistent with Arkansas’ system of justice; that re

sponsibility for administration of penalties in rape cases

lies with other officials besides juries; that “ it is not what

public officials say but what they do which must be deter

minative when discrimination is at issue” ; that in Max

well’s state court proceedings “ several occurrences under

scored the presence of the racial factor” , namely, the use

of the term “nigger” , the excuse or successful challenge

of the nine Negroes who were called for jury service, and

Opinion of Court of Appeals

the prosecutor’s reference to the race of the defendant

and the victim three times during the state trial “under

the guise of requesting the jurors to dismiss the fact from

their minds” ; that the state’s laws on segregation and

the history of the resistance to desegregation of schools

in Little Rock are consistent with the contention that race

is a factor in the disposition of rape cases and the im

position of the death penalty; that the court erred in re

stricting the defense proof of race figures to the three

counties; and that, finally, the imposition of the death

penalty for rape violates due process in that it is a cruel

and unusual punishment.

This question of unconstitutionality in application -was

raised both in the Supreme Court of Arkansas and in the

United States district court. Each tribunal decided the

issue adversely to Maxwell. Pp. 117-18 of 370 S.W.2d;

pp. 216-17 of 229 F.Supp.

There can be no doubt that the equal protection clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment and 42 U.S.C. § 1981,6

which implements it, (and, it would appear, Art. 2, § 3,

of the Arkansas Constitution)7 operate to invalidate any

state statute which would differentiate punishment solely

on the basis of race. Virginia, v. Rives, 100 U.S. 313, 318

(1879); Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303, 307

(1879); McLaughlin, v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184, 192-94

(1964); see Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U.S. 535, 541 (1942).

We recognize, too, that a statute’s discriminatory admin

6 Section 1981. “All persons within the jurisdiction of the United States

. . . shall be subject to like punishment, pains, penalties, taxes, licenses,

and exactions o f every kind, and to no other.”

7 “ The equality of all persons before the law is recognized, and shall

ever remain inviolate; nor shall any citizen ever be deprived of any right,

privilege or immunity, nor exempted from any burden or duty, on account

of race, color or previous condition.”

( a

Opinion of Court of Appeals

8a

istration or enforcement, dictated solely by considerations

of race, runs afoul of the equal protection clause, Yick

Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356, 373-74 (1886); see Snowden

v. Hughes, 321 U.S. 1, 8 (1944).

This court has not been insensitive to constitutional

claims based upon race. See, for example, Aaron v.

Cooper, 257 F.2d 33 (8 Cir. 1958), aff’d 358 U.S. 1; Bailey

v. Henslee, 287 F.2d 936 (8 Cir. 1961), cert, denied 368

U.S. 877; and Henslee v. Stewart, 311 F.2d 691 (8 Cir.

1963), cert, denied 373 U.S. 902. “But purposeful dis

crimination may not be assumed or merely asserted . . .

It must be proven. . . .” , and the burden is on the one

asserting discrimination. Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S.

202, 205, 209 (1965); Tar ranee v. Florida, 188 U.S. 519,

520 (1903).

A meticulous review of the entire record in the United

States district court and of the entire record in the state

court convinces us that no federally unconstitutional ap

plication of the Arkansas rape statutes to this defendant

has been demonstrated. We reach this result upon the

following considerations:

1. The statistical argument is not at all persuasive.

The evidence as to the state at large showed that, in the

50 years since 1913, 21 men have been executed for the

crime of rape; that 19 of these were Negroes and two

were white;8 that the victims of the 19 convicted Negroes

were white females; and that the victims of the two con

victed whites were also white females. As to Garland

County, for the decade beginning January 1, 1954, Max

well’s evidence was to the effect that seven whites were

8 Needham v. State, 215 Ark. 935, 224 S.W.2d 785 (1949) ; Fields v.

State, 235 Ark. 986, 363 S.W.2d 905 (1963).

Opinion of Court of Appeals

9a

charged with rape (two of white women and the race of

the other victims not disclosed), with four whites not

prosecuted and three sentenced on reduced charges; that

three Negroes were charged with rape, with one of a

Negro woman not prosecuted and another of a Negro re

ceiving a reduced sentence, and the third, the present de

fendant, receiving the death penalty. With respect to

Pulaski County for the same decade, there were 11. whites

(two twice) and 10 Negroes charged, with the race of the

victim of two whites and one Negro not disclosed. Three

whites received a life sentence. One white was acquitted

of rape of a Negro woman. One received a sentence on

a reduced charge, two were dismissed, two cases remained

pending, one was not prosecuted, and the last was ex

ecuted on a conviction for murder.9 Of the Negroes, three

with white victims and two with Negro victims received

life. One case was dismissed, one was not arrested, two

with Negro victims were sentenced on reduced charges,

and one, Bailey, with a white victim, was sentenced to

death. In Jefferson County eight Negroes were charged,

with the cases against five dismissed, another dismissed

when convicted on a murder charge, and two receiving

sentences on reduced charges. Sixteen whites were

charged. One was charged three times with respect to

Negro victims and as to two of these charges received

five years suspended on a guilty plea. Two others re

ceived three year sentences. One is pending, one was

9 Leggett v. State, 227 Ark. 393, 299 S.W.2d 59 (1957); Leggett v.

State, 228 Ark. 977, 311 S.W.2d 521 (1958), cert, denied 357 U.S. 942;

Leggett v. Ilenslee, 230 Ark. 183, 321 S.W.2d 764 (1959), cert, denied 361

U.S. 865; Leggett v. State, 231 Ark. 7, 328 S.W.2d 250 (1959) ; Leggett v.

State, 231 Ark. 13, 328 S.W.2d 252 (1959) ; Leggett v. Kirby, 231 Ark.

576, 331 S.W.2d 267 (1960).

Opinion of Court of Appeals

10a

executed,10 and the rest were dismissed. The race of

four defendants was not disclosed; three of these cases

were dismissed and one is pending.

The complaint as to the federal court’s restricting the

statistical inquiry to three counties was not preserved by

objection or offer of proof and there is no claim here that

material from the State’s remaining counties would be

any more significant than that of the three counties pre

sented.

These facts do not seem to us to establish a pattern or

something specific or useful here, or to provide anything

other than a weak basis for suspicion on the part of the

defense. The figures certainly do not prove current dis

crimination in Arkansas, for in the last fourteen years the

men executed for rape have been two whites and two

Negroes. The circumstances of each rape case have par

ticular pertinency. We are given no information as to

how many Negroes and how many whites, after investiga

tion, were not charged. Note Hamm v. State, 214 Ark.

171, 214 S.W.2d 917 ((1948), where a Negro convicted of

rape of a white woman received a life sentence.

Turning to the three county statistics, we find no death

sentence at all in Garland County in the 1954-1963 decade

until Maxwell’s case. We also find that of the two other

Negroes charged, one was not prosecuted and the other

was sentenced on a reduced charge. In Pulaski County

we have about the same number of whites and Negroes

charged, with only one death penalty, albeit in an inter

racial case, and one acquittal, also in an interracial case.

But members of both races, three whites and five Negroes

(three interracial), received life sentences. In Jefferson

Opinion of Court of Appeals

10 Fields v. State, supra, 235 Ark. 986, 363 S.W.2d 905 (1963).

11a

Comity we find few convictions for either race but one

white man with a white victim was executed.

2. The defense argument goes too far and would, if

taken literally, make prosecution of a Negro impossible

in Arkansas today because of the existence in the past of

standards which are now questionable. This would effect

discrimination in reverse. The fact that this court has

concluded that certain Arkansas procedures did not meet

constitutional standards as interpreted by the Supreme

Court (see Bailey v. Henslee, supra, 287 F.2d 936, and

Henslee v. Stewart, supra, 311 F.2d 691, but compare

Moore v. Henslee, 276 F,2d 876 (8 Cir. I960)) does not

mean that this former defect must permeate all subse

quent proceedings in the state so as to render them un

constitutional. We pointed this out, as to jury selection,

in Bailey v. Henslee, supra, p. 943 of 287 F.2d, where we

said, “ Discriminatory selection in prior years does not

nullify a present conviction if the selection of the jury

for the current term is on a proper basis” , and where we

noted the Supreme Court’s comment, in Brown v. Allen,

344 U.S. 443, 479 (1953), that “ Former errors cannot in

validate future trials” .

3. The “ nigger” references, while unfortunate, are only

two in number and no objection was made to either. Both

were at the state court hearing on defense motions when

no jury was present. One was by the then superintendent

of the state penitentiary. The other was the prosecutor’s

reference to “white persons or nigger persons” . Through

out the balance of that hearing, throughout the entire

state court trial, and throughout the federal habeas corpus

Opinion of Court of Appeals

12a

proceeding, although race is necessarily mentioned many

times, not one other instance of this kind appears.

4. The other race references, complained of by the de

fense, are three in number. The first was in the prose

cutor’s opening statement to the jury: “ I want to ask you

first and tell you that it is your duty, and the Court will

so instruct you, to put from your mind any thought of

race. Ladies and Gentlemen, race has nothing to do with

it . . .” . The other two were of like import in his clos

ing argument. We find no error in these three references.

On their face they are as indicative of complete fairness

as of unfairness. No point is raised as to tone of voice,

attitude, or demeanor. The race of both the victim, who

testified, and of Maxwell, who of course was present in

court, was obvious. The comments, as we read them in

context in the cold record, could well be deserving of com

mendation, rather than condemnation.

5. The fact that in this particular case the nine Negroes

who appeared for jury service were all excused for cause

by the court (three) or peremptorily challenged by the

prosecution (six) and, as a consequence, the petit jury

was all white, is not an unconstitutional result. Swain v.

Alabama, supra, 380 U.S. 202, 209-22 (1965); Hall v.

United States, 168 F.2d 161, 164 (D.C. Cir. 1948), cert,

denied 334 U.S. 853; United States ex rel. Dukes v. Sain,

297 F.2d 799 (7 Cir. 1962), cert, denied 369 U.S. 868. See

Frazier v. United States, 335 U.S. 497, 507 (1948).

6. We are aware of the comments of three Justices, at

375 U.S. 889-91, dissenting from the Supreme Court’s de

nial of certiorari in Rudolph v. Alabama, 275 Ala. 115, 152

Opinion of Court of Appeals

13a

So.2d 662 (1963). The dissenters would have had the

Court consider in that case whether the Eighth Amend

ment,11 with its prohibition of “ cruel and unusual punish

ments” , and the Fourteenth “ permit the imposition of

the death penalty on a convicted rapist who has neither

taken nor endangered human life” . It is to be observed

that the record before us reveals that the rapist of the

victim here was evidently not one who failed to endanger

human life. He struck and injured a helpless and aged

man, he bruised the victim and he threatened to kill both.

Despite whatever personal attitudes lower federal court

judges as individuals might have toward capital punish

ment for rape, any judicial determination that a state’s

(in this case, Arkansas’ ) long existent death-for-rape stat

ute (it has been on the books since December 14, 1842)

imposes punishment which is cruel and unusual, within

the language of the Eighth Amendment and, by refer

enced inclusion, violative of due process within the mean

ing of the Fourteenth Amendment, must be for the Su

preme Court in the first instance and not for us. See

Ralph v. Pepersack, 335 F.2d 128, 141 (4 Cir. 1964).

B. The selection of the petit jury. The defense argu

ment here is that due process and equal protection have

been denied Maxwell because the petit jury list was com

piled from a racially designated poll tax book and be

cause the jury list itself indicated race. This argument

was not advanced in the state court proceedings.

In Arkansas petit jurors are selected from electors.

Ark. Stat. 1947, § 39-208. Electors are persons who cur- 11

11 The Arkansas Constitution, Art. 2, § 9, also reads:

“ Excessive bail shall not be required, nor shall excessive fines be im

posed; nor shall cruel or unusual punishment be inflicted; nor wit

nesses be unreasonably detained.”

Opinion of Court of Appeals

14a

rently have paid the State’s poll tax. Ark. Const., Art.

3, § 1; Ark. Stat. § 3-104.2. The statutes require that the

official list, bound as a book, of a county’s poll tax payers,

§ 3-118, and the poll tax receipts, § 3-227(b), specify color.

In contrast to the situation in the district court, pp.

213-16 of 229 F.Supp., no issue is raised here as to any

deficiency in the efforts or methods of the jury commis

sioners, as to underrepresentation of the Negro race in

the Gerland County jury lists, or as to any pattern of

Negro repeaters on the juries.

In Bailey v. Henslee, supra, p. 940 of 287 F.2d, we out

lined at footnote 5 the methods prescribed by the Arkan

sas Statutes for the selection of jury commissioners and

of jurors and, at pp. 941-45, we set forth, with extensive

citations, the applicable general principles relative to race

in jury selection. We cited four United States Supreme

Court cases of particular pertinence. Norris v. Alabama,

294 U.S. 587 (1935); Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S. 128 (1940) ;

Avery v. Georgia, 345 U.S. 559 (1953); and Eubanks v.

Louisiana, 356 U.S. 584 (1958). In Henslee v. Stewart,

supra, p. 694 of 311 F.2d, we again referred to the same

principles and the same cases. To that list of four Su

preme Court opinions one should now add Arnold v. North

Carolina, 376 U.S. 773 (1964), where, with a substantial

proportion of Negroes in the county and on the poll tax

list but only one on a grand jury in 24 years, the Court

held that a prima facie case of equal protection denial had

been established, and Swam v. Alabama, supra, 380 U.S.

202, 205-09 (1965), where the Court held that there was

no “ forbidden token inclusion” and that a prima facie

case of discrimination had not been made out when Negro

representation on jury panels was existent though less

than the percentage of Negro males in the county, when

Opinion of Court of Appeals

15a

there was an average of six to seven Negroes on petit

jury venires in criminal cases although no Negro had

actually served on a petit jury since 1950, and when an

identifiable group in a community is underrepresented by

as much as ten percent. See, also, Coleman v. Alabama,

377 U.S. 129 (1964).

In both Bailey and Stewart we concluded that the facts,

in the aggregate, established a prima facie case of im

proper limitation of Negroes in the selection of a petit

jury panel. Among the several factors which led to our

conclusion in both Bailey and Stewart were the circum

stances that the poll tax receipt carried, with other in

formation, the color of the taxpayer and that the jury

commissioners themselves affixed race identification marks

to their lists. We mentioned, p. 947 of 287 F.2d, p. 695

of 311 F.2d, that this presented “a device for race identi

fication with its possibility of abuse” .

We do not reach the same conclusion here. Our reasons

are the following: (1) There is no proof that the jury

list was compiled from the poll tax list. Each jury com

missioner specifically testified otherwise and asserted that

a proposed list was first independently prepared and that

the racially designated poll tax book was consulted only

thereafter. It had to be consulted, of course, in order to

ascertain that the persons tentatively selected were quali

fied electors. (2) Although the list of petit jurors formally

transmitted by the jury commissioners to the clerk of

court possessed, at the time of the habeas corpus hearing,

a small handwritten “c” after eight of the 36 names

thereon, exclusive of alternates, there was no positive

evidence as to when those leters were affixed or by whom.

The list had been compiled two months before the crime

with which Maxwell was charged. Each commissioner

Opinion of Court of Appeals

16a

denied making the identifying marks. (3) The clerk

testified that he had no personal recollection whether,

when he opened the list, it had any marks as to color;

that he was not certain he had placed the marks on the

list; that sometimes he did this for his own information

and for newspapers; and that on most lists the jury com

missioners did indicate race. Even the defense attorneys

here had examined this particular list prior to the habeas

corpus hearing. (4) None of the commissioners recalled

the presence of race marks in the poll tax books. Each

justified this conclusion on the ground that the marks

were insignificant and unimpressive. (5) for what it is

worth, one of the jury commissioners here was a Negro.

The clerk testified that, with the exception of one or

two terms, there has been a Negro jury commissioner for

every term of court in Garland County in the last nine

years.

In the light of these facts, we cannot conclude that the

selection of this particular petit jury was unconstitution

ally discriminatory. The use of race identification marks

is, of course, under principles presently espoused, and as

we noted in Bailey and again in Stewart, most disturbing.

Whether the Arkansas statutory provisions requiring race

identification on poll tax receipts and on the poll tax books

are unconstitutional is a question not yet finally resolved.

Hamm v. Virginia State Bd. of Elections, 230 F.Supp.

156, 157-58 (E.D. Va. 1964), summarily aff’d. sub nom.

Tancil v. Woolls, 379 U.8. 19, appears to cast some doubt

on their validity. Yet that opinion also states that race

designations in certain records may serve a useful and

lawful purpose. Until these Arkansas statutory require

ments are nullified or repealed it is to be presumed that

local officials must and will comply with them. The pres

Opinion of Court of Appeals

17a

ent action is not one to restrain such compliance. Per

sons desiring that result have the right to seek it. In the

meantime, we cannot say that, because the poll tax re

ceipts and books designate race, it necessarily follows

that every jury list in Arkansas is automatically uncon

stitutional. So to conclude would ignore the important

possibility of initial selection being made, as here, inde

pendent of the poll tax list. The Arkansas system may

presently be imperfect but “an imperfect system is not

equivalent to purposeful discrimination based on race” .

Swain v. Alabama, supra, p. 209 of 380 U.S. We hold

that the manner of selecting this particular petit jury list

avoided any constitutional obstacle which might be in

herent in the state statutes requiring race identification.

This makes it unnecessary to consider the argument

(strenuously urged by Stephens and upheld by the Dis

trict Court, pp. 212-13 of 229 F.Supp., as an alternative

ground) that Maxwell waived any objection to the petit

jury panel and did so within the permitted scope of Fay

v. Noia, supra, 372 U.S. 391, 438-40 (1963).

C. The coat. As has been noted, the controversial coat

was not introduced in evidence at the state court trial.

Witnesses, however, made references to it in their testi

mony.

Maxwell, of course, has standing to complain of these

references. Jones v. United States, 362 U.S. 257, 265-67

(1960).

The facts here are important: The offense took place at

approximately three o’clock in the morning of November

3, 1961. It was raining and wet. The victim was promptly

taken by the police to a hospital. At the hospital she de

scribed her assailant to Captain Crain of the Hot Springs

Opinion of Court of Appeals

18a

Police Department and to Officer 0. D. Pettus, a Negro.

She stated that the man had told her he was Willie C.

Washington. Two persons with that name, senior and

junior, were brought before her but she identified neither.

She described her attacker in greater detail. Pettus there

upon suggested that it might have been Maxwell. Officer

Childress, who was on car patrol duty and in uniform at

the time, was directed by radio to pick up Maxwell. He

went to the Maxwell home. The defendant’s mother, then

age 38, answered his knock. He told her he wanted to

talk to William. She let him enter, checked to see if her

son was in, and led Childress to the bedroom occupied by

Maxwell and two younger sons. Childress told Maxwell

he wanted to talk to him down town and asked him to

dress. Childress testified that Maxwell went to the closet

for clothes that were hanging there in a wrapper, and

that he asked him “ to put on these other clothes here that

he had on” . The latter were wet. Maxwell testified that

he was told to put on the clothes he had on that night,

that he went to the closet to get these, that he was then

told to put on the clothes folded on the chair, that he was

going to takes those clothes to the cleaners, and that they

were not his.

Maxwell was taken to the hospital and before the vic

tim. She at first did not identify him as her attacker

but witnesses described her as visibly disturbed and shak

ing when he stood before her. She later said she had

recognized him but feared for her life if she identified

him. Maxwell was taken from the hospital to the police

station.

Both sides admit that the exact times and place of

Maxwell’s arrest “ is not entirely clear from the record” .

Opinion of Court of Appeals

19a

It might have been at the home at about four a.m. or

shortly thereafter at the hospital.

Captain Crain, with Officer Timms, went to the Maxwell

home about five a.m. to get, as he testified at the habeas

corpus hearing, “ some more clothes that we thought might

help us in our investigation of this ease” or, as he testi

fied at the trial, “I was looking for a particular object

. . . I wanted what he was wearing that night” . They

had no search warrant. Mrs. Maxwell permitted them to

enter. They were in uniform. The testimony is in con

flict as to whether Mrs. Maxwell was then informed of

any charge against her son; Crain said he so advised her

but she stated, “He didn’t say nothing about no rape

case” . (The district court found she had been so ad

vised). She directed the officers to the clothes closet. The

blue coat in question was obtained from that closet. It

was eventually sent to the FBI laboratory. At the trial

there was expert testimony that fibers in the coat matched

others found on the victim’s pajamas and on part of a

nylon stocking picked up near the scene of the crime, and

that fibers in the pajamas matched those found on the

coat.

Mrs. Maxwell was understandably upset at the times

the officers called at her home. In the margin we quote

her testimony as to both the first call12 and the second * I

Opinion of Court of Appeals

12 “ . . . it was late and I was asleep and someone knocked on the door

and I woke up and I asked who was it and he said the policeman and

I went to the door to let him in. He asked me did I have a son here

by the name of William and I told him yes and he just come on in, he

didn’t have a search warrant or anything and I let him. I didn’t know

any better myself but I—I didn’t know that he—you know, everything

was all right, my children were at home and all and I just let him in.”

20a

call.13 Maxwell’s father worked at night and was not

home when the officers called.

At the habeas corpus hearing Maxwell admitted that he

had been adjudged guilty of two counts of petit larceny

in 1958 and of federal post office charges in the same year.

We thus have a situation where the Maxwell home was

twice visited by officers within two hours after the very

crime was committed, where the second visit was within

an hour of the first, where the officers were in uniform,

where they were permitted access to the home by the

mother, where on the second visit she pointed out the

closet where the coat was, and where the accused, with his

brothers, was still living with his parents in that home.

The district court held, pp. 209-211 of 229 F.Supp., that

the taking of the coat violated no Fourth Amendment

rights of Maxwell because his mother freely gave her con

sent and had the authority so to consent and because,

upon all the circumstances, any search and seizure here

was reasonable.

The parties are agreed, of course, that the Fourth

Amendment’s restraints against unreasonable searches

and seizures are now applicable to the states under the

due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and

are to be measured by standards which govern federal

cases, Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643 (1961); K er v. Cali

fornia, 374 U.S. 23, 33 (1963); Aguilar v. Texas, 378 U.S.

108, 110 (1964) ; Linkletter v. Walker, . . . U.S____(1965), I

13 “ I opened the door and I was afraid to not let them in because—

you know— when they said they were police officers—well, you just—I’ve

just always— I just let the poliee officers in because I just feel like he

is for peace and all, and I just—I don't know, I didn’t know anything—

I never been in anything like this and I just let them in and I still didn’t

think anything, didn’t any of those officer have any search warrant or

anything, didn’t show me anything like that.”

Opinion of Court of Appeals

21a

and that the Fifth Amendment’s guaranty against self

incrimination, through the Fourteenth, is also applicable

to the states and upon federal standards.14 Malloy v.

Hogan, 378 U.S. 1, 8, 11 (1964).

The parties are not in agreement, however, as to

whether what was done here was incident to a lawful ar

rest, see Preston v. United States, 376 U.S. 364 (1964),

or, if not, as to whether it was justified because of emer

gency or exceptional circumstances. We pass these is

sues and move on to the questions whether there was a

consent by Mrs. Maxwell and, if so, whether her consent

was a curative factor.

Although a consent freely and intelligently given by

the proper person may operate to eliminate any question

otherwise existing as to the propriety of a search, Honig

v. United States, 208 F.2d 916, 919 (8 Cir. 1953); Burge v.

United States, 332 F.2d 171, 173 (8 Cir. 1964), cert, denied

379 U.S. 883; Burnside v. Nebraska, . . . F.2d . . . (8 Cir.

1965), the defense argues that there is a presumption

that a consent is coerced unless proved otherwise by the

government and that the facts here—the early morning

calls at the Maxwell home, the presence of men clothed

with the uniform of authority, the confrontation of a

Negro mother by white police, and her obvious concern

Opinion of Court of Appeals

14 The Fifth-Fourteenth Amendment argument as to self-incrimination,

although possibly embraced in the language of the first amendment to the

petition for writ of habeas corpus (where it was alleged that the police

searched Maxwell’s room “and obtained clothing belonging to petitioner

without a search warrant, without the consent of petitioner and without

the consent of petitioner’s parents” ), was apparently not pressed before

the district court and is really asserted for the first time only on this

appeal. Because of this we could choose to ignore it here. Sutton v.

Settle, 302 F.2d 286, 288 (8 Cir. 1962), cert, denied 372 U.S. 930; Hunting-

ton v. Michigan, 334 F.2d 615, 616 (6 Cir. 1964); Trujillo v. Tinsley, 333

F.2d 185 (10 Cir. 1964). But this is a capital case and, without our doing

so regarded as a precedent, we consider this point on the merits.

22a

and confusion— “militate against finding voluntary con

sent” .

We recognize that it has been said that the government

has the burden to establish the legal sufficiency of a con

sent. Judd v. United States, 190 F.2d 649, 651 (D.C. Cir.

1951); United States v. Page, 302 F.2d 81, 83-84 (9 Cir.

1962). Nevertheless, the existence and voluntariness of

a consent is a question of fact. United States v. Page,

supra, p. 83 of 302 F.2d. And Judge Young specifically

found that there was a consent here and that it was volun

tary. We cannot say that his finding was either errone

ous or unsupported by substantial evidence. United

States v. Page, supra, p. 85 of 302 F.2d; Davis v. United

States, 328 U.S. 582, 593 (1946); United States v. Ziemer,

291 F.2d 100, 102 (7 Cir. 1961), cert, denied 368 U.S. 877;

McDonald v. United States, 307 F.2d 272, 275 (10 Cir.

1962). The record clearly discloses no concealment of

identity, no discourtesy, no abuse or threat, and no ruse

or force exerted by the officers. It contains testimony

that Mrs. Maxwell showed and directed them to the closet

where her son’s clothes were. On cross-examination she

herself conceded that she permitted the officers to enter

and to obtain the coat. She fully cooperated. She and

her husband were both present throughout the state court

trial, sat with their son at the counsel table, and heard,

with no indication of opposition, the testimony of the

officers as to how the coat was obtained with her permis

sion. All this adequately supports the court’s finding of

voluntary consent. Roberts v. United States, 332 F.2d

892, 897 (8 Cir. 1964). The factual situation is different

than that of Pekar v. United States, 315 F.2d 319, 325 (5

Cir. 1963), urged by Maxwell here, or the implied coercion

Opinion of Court of Appeals

23a

referred to in Amos v. United States, 255 U.S. 313, 317

(1921).

What, then, is the effect of this voluntary consent on

the part of Maxwell’s mother! We recognize, of course,

that constitutional rights are not to depend upon “ subtle

distinctions, developed and refined by the common law in

evolving the body of private property law” . Jones v.

United States, supra, 362 U.S. 257, 266 (1960). But this

is not a case of property right distinctions. The defense

concedes that Mrs. Maxwell possessed a proprietary in

terest in the house; that Maxwell himself only shared a

room there with his two younger brothers; and that no

landlord-tenant relationship existed between Maxwell and

his parents. Mrs. Maxwell had control of the premises,

undiminished by any kind of a less-than-fee interest pos

sessed by Maxwell. This fact stands in contrast to the

hotel or rental situations.16 See Stoner v. California, 376

U.S. 483 (1964); United States v. Jeffers, 342 U.S. 48

(1951); Lustig v. United States, 338 U.S. 74 (1949); Chap

man v. United States, 365 U.S. 610 (1961); McDonald v.

United States, 335 U.S. 451 (1948); Klee v. United States,

53 F.2d 58 (9 Cir. 1931). The situation strikes us as

being no different, factually, than if Mrs. Maxwell herself

had brought the coat, it being properly in her possession,

to the authorities. They came to the home, it is true, but

they obtained the coat by freely allowed access to the

house, by freely given directions as to its location, and by

freely permitted acquisition of it by the officers and de

parture with it in their hands. Roberts v. United States,

16 But even in these situations abandonment (not present here) while

the rental term is not yet expired overcomes any obstacle presented by a

rental relationship. Abel v. United States, 362 U.S. 217, 240-41 (1960);

Feguer v. United States, 302 F.2d 214, 248-49 (8 Cir. 1962), cert, denied

371 U.S. 872; Roberts v. United Stat&s, 332 F.2d 892, 898 (8 Cir. 1964).

Opinion of Court of Appeals

24a

supra, 332 F.2d 892, 896-97 (8 Cir. 1964); Burge v. United

States, 342 F.2d 408, 413-14 (9 Cir. 1965); Rees v. Peyton,

341 F.2d 859, 861-63 (4 Cir. 1965); United States v. Guido,

251 F.2d 1, 3-4 (7 Cir. 1958), cert, denied 356 U.S. 950;

Woodard v. United States, 254 F.2d 312 (D.C. Cir. 1958),

cert, denied 357 U.S. 930; Fredrickson v. United States,

266 F.2d 463, 464 (D.C. Cir. 1959); Morales v. United

States, . . . F.2d . . . (9 Cir. 1965); United States ex rel.

McKenna v. Myers, 232 F.Supp. 65, 66 (E.D. Pa. 1964).

See United States v. Maroney, 220 F.Supp. 801, 805-06

(W.D. Pa. 1963); Gray v. Commonwealth, 198 Ky. 610, 249

S.W. 769 (1923) ; Irvin v. State, . . . Fla. . . ., 66 So.2d

288, 293 (1953), cert, denied 346 U.S. 927.

But the defense argues that this coat was Maxwell’s

personal effect and clothing; that it could not be picked

up or acquired in any manner, even with a valid search

warrant, without his consent; and that it was evidentiary

material not the proper subject of a search. Gouled v.

United States, 255 U.S. 298 (1921) and Holzhey v. United

States, 223 F.2d 823 (5 Cir. 1955) are particularly cited.

Whatever force might otherwise lie in the facts that the

coat was clothing personal to Maxwell (and thus presum

ably an “ effect” within the meaning of the Fourth

Amendment), that it was not contraband or an article the

possession of which is illegal, or an instrumentality or

fruit of the crime, or capable of possible use to effect his

escape, see Harris v. United States, 331 U.S. 145, 154

(1947); United States v. Lefkowitz, 285 U.S. 452, 463-66

(1932); Agnello v. United States, 269 U.S. 20, 30 (1925);

Honig v. United States, supra, pp. 919-20 of 208 F.2d, this

argument overlooks the consent to the officers’ acquisition

of the coat by a person having the proprietary interest in

the premises where it was. If there was a search here at

Opinion of Court of Appeals

25a

all, it was not a general search, and certainly it was not

a search violative of a locked container or the like. Rob

erts v. United States, supra, p. 898 of 332 F.2d. Compare

United States v. Blok, 188 F.2d 1019, 1021 (D.C. Cir.

1951); Holzhey v. United States, supra, p. 826 of 223 F.2d.

It was an item which freely came into the hands of the

authorities by one who had the right to make it available

to them. See Haas v. United States, 344 F.2d 56, 57-60

(8 Cir. 1965), where this court upheld the seizure, in a

search pursuant to a lawful arrest, of a defendant’s grey

suit which fit the description of clothing worn by a bandit

and Irvin v. State, supra, p. 293 of 66 So. 2d. Compare

Williams v. United States, supra, 263 F.2d 487.

The situation therefore appears to us to be one not

involving any unreasonable search or seizure within

the prohibition of the Fourth, Fifth, and Fourteenth

Amendments. Reasonableness, after all, is the applicable

standard. United States v. Rabinoivitz, 339 U.S. 56, 63

(1950) ; Sartain v. United States, 303 F.2d 859, 862-63 (9

Cir. 1962), cert, denied 371 U.S. 894.

Neither are we impressed with any suggestion that the

testimonial references to the coat were in any way a fur

ther violation of Maxwell’s right not to be compelled

physically to be a witness against himself, within the

meaning of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments. The

description of the coat and what was found on it wms ob

jective evidence from the mouths of witnesses who saw or

who investigated. The coat is in no different category

than the contours of Maxwell’s face, the color of his hair,

the description and the nature and condition of the clothes

he wrnre, and his very size and color. Holt v. United

States, 218 U.S. 245, 252-53 (1910); Caldwell v. United

States, 338 F.2d 385, 389 (8 Cir. 1964).

Opinion of Court of Appeals

26a

The district court’s denial of the petition for habeas

corpus is therefore affirmed. Where life is concerned a

conclusion of this kind may involve a personal reluctance

for judges. We deal, however, with statutory provisions

which are not our province, at least not yet (see Rudolph

v. Alabama, supra, 375 U.S. 889), to change. Maxwell’s

life therefore must depend upon different views enter

tained by the Supreme Court of the United States or upon

the exercise of executive clemency.

Opinion of Court of Appeals

R idge, dissenting:

I agree with the disposition made in the majority opin

ion of appellant’s assignments of error 1 and 2, as raised

in this appeal.

I cannot agree with the ruling and disposition made in

respect to assignment of error 3, i.e. the search and seiz

ure issue. . . the taking of appellant’s “ coat” from his

place of abode by police officers under the factual circum

stances related in the majority opinion.

As I view the facts in the majority opinion and those

appearing in Maxwell v. State, 370 S.W.2d 113 (Ark.,

1963); and Maxwell v. Stephens, 229 F.Supp. 205 (E.D.

Ark., 1964), I think it is readily apparent that the search

of appellant’s place of abode and seizure of his “blue

coat” were made under factual circumstances which reveal

the same to be in violation of his Fourth Amendment

rights made obligatory on the States by the Fourteenth

Amendment to enforce.

I find fortification for that conclusion from the opinion

and decision of the Court of Appeals of Kentucky, as

made in Elmore v. Commonwealth (Ky.), 138 S.W.2d 956

(1940), where that Court considered a factual situation in

27a

a rape ease, which are on all fours with those appearing

in the case at bar and ruled the seizure there made to be

unlawful under federal constitutional standards.

In adjudging the validity of the search and seizure issue

here, the starting point begins with appellant’s arrest.

Hence I consider the constitutionality thereof must be

measured by a consideration of the following facts:

When Police Officer Childress first went to appellant’s

home he did so for the purpose of taking appellant into

custody. At that time he told appellant, “he (Childress)

wanted to talk to him downtown, and asked him to dress

. . .” and “to put on (the) clothes he had on” previously

that night, “which were wet.” Under compulsion of Chil

dress’ command, appellant dressed. I find no reasonable

ground for hesitancy in determining Maxwell was then

placed under arrest, cf. State v. King, 84 N.J. Super. 297,

201 A.2d 758. Concededly, no search was then made by

Officer Childress to seize appellant’s coat incident to his

arrest.

That appellant did not voluntarily leave his home in

company with Officer Childress is manifest, cf. Judd v.

United States, 190 F.2d 649 (D.C. 1951).

One or two hours thereafter, Capt. Crain and Officer

Timms went to the Maxwell home, without a search war

rant, and took possession of appellant’s “blue coat”

under circumstances as related in the majority opinion.

The conversation those two police officers then had with

appellant’s mother does not raise a question of credibility.

The only issue presented thereby is whether “consent”

as claimed by the State was freely given to those officers

to search the Maxwell home, and whether appellant’s

mother had power of possession to release appellant’s per

sonal belongings to the custody of such officers.

Opinion of Court of Appeals

28a

I do not consider the conversation appellant’s mother

had with Capt. Crain and Officer Timms to have any pro

bative value in making a determination of the validity of

the search and seizure made by those officers. Mere ac

quiescence in the apparent authority of a police officer is

not usually considered consent, cf. Dukes v. United States,

275 Fed. 142 (4 Cir., 1921); United States v. Marquette,

271 Fed. 120 (N.D. Calif., 1920). What was then said by

appellant’s mother “was but showing her respect for and

obedience to the law and she was not consenting to the

search regardless (of lack of a) search warrant.” Stroud v.

Commomvealth (Ky.), 175 S.W.2d 368, 370, citing Amos v.

United States, 255 U.S. 313 (1921); and Elmore v. Com

monwealth, supra. As the majority opinion notes, the

validity of arrest and search and seizure here must be

determined by reasonableness in light of the particular

circumstances revealed. I consider the factual circum

stances in the case at bar reveal “ implied coercion.”

Admittedly, the coat that was seized was the personal

property of appellant. Being under arrest at the time he

was taken from the place of his abode, where the coat was

then situate, the only reasonable inference is that he did

not voluntarily place possession of his coat in his mother

or anyone else. No one can waive his constitutional right

to assert his right of possession thereof. The search here

made was not incident to his arrest. To be legal, the

seizure of appellant’s coat could only have been validly

made without a search warrant at the time appellant was

arrested by Officer Childress. His other clothing was so

seized.

Respondent’s argument that this search and seizure was

lawful because of possible destruction of evidence, and

“ inability to secure issuance of a search warrant,” is hoi-

Opinion of Court of Appeals

29a

Opinion of Court of Appeals

low, indeed. Appellant was then under arrest. There is

no evidence that his mother had any knowledge that his

coat might be material to any offense for which her son

was arrested. The only possible inference I can make is

that she first gleaned knowledge of the cause of his arrest

from Capt. Crain or Officer Timms during the time the

illegal search and seizure here considered was made. It is

not contended that Childress told her why appellant was

being taken “downtown” , cf. Foster v. United States (8

Cir., 1960), 281 F.2d 310.

I would reverse the judgment below.

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

E aste rn D is tr ic t of A r k a n sa s

P in e B l u f f D iv isio n

No. PB 64 C 4

Opinion of District Court

W il l ia m L. M a x w e l l ,

-v -

Petitioner,

D a n D . S t e p h e n s , Superintendent of Arkansas

State Penitentiary,

Respondent.

M e m o r a n d u m of O p in io n

This habeas corpus proceeding is brought by William

L. Maxwell, a Negro male, age 24, who was convicted for

the crime of rape in the Circuit Court of Garland County,

Arkansas, on March 21, 1962, and sentenced to death. The

conviction was affirmed by the Arkansas Supreme Court in

the case of Maxwell v. State, 236 Ark. 694, 370 S.W.2d 113

(1963), and following a denial of petition for rehearing

the date of execution was scheduled for January 24, 1964.

No application for certiorari was made to the United States

Supreme Court. The instant action was filed on January

20, 1964, alleging that the state court conviction was ob

tained in violation of petitioner’s constitutional rights

guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment to the United

States Constitution. Petitioner was permitted to amend

31a

his petition twice and a hearing was held on the petition,

as amended, on February 12, 1964, as well as on February

27, 1964, at which time the testimony was concluded. Peti

tioner and respondent have submitted briefs in support

of their respective contentions.

Throughout the state court proceedings, petitioner was

represented by Mr. Christopher C. Mercer, Jr., a capable

attorney experienced in this type of litigation.1 Subsequent

to the state court proceedings, and prior to this action, pe

titioner obtained the services of his present counsel who

now represent petitioner in this habeas corpus proceeding.

The question of Maxwell’s guilt is not now before this

court. Cf. Henslee v. Stewart, 311 F.2d 691 (8th Cir. 1963) ;

Bailey v. Henslee, 287 F.2d 936, 939 (8th Cir. 1961). The

circumstances of the crime and the evidence against Max

well are fully discussed by the Arkansas Supreme Court

in Maxwell v. State, supra, 236 Ark. 696-700, 370 S.W.2d

114-116. The only issue which now confronts this court is

whether Maxwell’s federal constitutional rights, in the

particulars relied upon, were preserved in the state court

action.

The alleged violations of petitioner’s constitutional

rights, in substance, are that: (1) Petitioner was illegally

arrested and there was an unlawful search and seizure of

his home and person; (2) Petitioner was tried in a hostile

atmosphere; (3) Racial discrimination was practiced in the

selection of the jury which tried petitioner; (4) There has

been an unconstitutional application and enforcement of

Ark.Stat. § 41-3403 (1947) against petitioner, and the death

1 Mr. Mercer is a graduate of the University of Arkansas School of Law

and was one o f the attorneys who represented Lonnie Mitchell in a habeas

corpus proceeding. Mitchell v. Henslee, 208 F.Supp. 533 (E.D.Ark. 1962)

rev’d per curiam Case No. 17,208, 332 F.2d 16 (8th Cir. May 4, 1964).

Opinion of District Court

32a

penalty upon conviction for rape provided by this statute

is a “cruel and unusual” punishment contrary to the basic

concepts of a civilized society. In this opinion, the Court

will deal with these issues in the order mentioned.

I . T h e A rrest an d S earch

The offense with which petitioner was charged occurred

about three o’clock in the morning of November 3, 1961.

Approximately one hour later, petitioner was taken into

custody by police officers at his parents’ home where he

lived. This was done on the basis of information and de

scriptions given by the victim to a Negro police officer,

O. D. Pettis, now deceased. Sometime around five o’clock

that morning police officers Captain Crain and Officer

Timms made a trip back to petitioner’s home in order to

obtain some clothing belonging to petitioner allegedly worn

during the commission of the offense; and another trip was

made by Office Timms later that same morning in order to

obtain a change of clothing for petitioner since arrange

ments had been made for the clothes allegedly worn by

petitioner during the rape, and which petitioner put on

when taken into custody, to be sent to the laboratory of the

Federal Bureau of Investigation in Washington, D. C.

When petitioner was taken into custody he was viewed

by the victim at a local hospital and subsequently identified

as the assailant. Thereupon, petitioner was incarcerated

in the City Jail and held until later during the afternoon or

evening of November 3rd, when he was taken to the County

Jail in nearby Malvern, where petitioner remained until

November 6th. Petitioner signed a written confession while

at the County Jail in Malvern and made another confes

sion later in Hot Springs. Petitioner was then returned

to the city of Hot Springs, where on November 7, he was

Opinion of District Court

33a

formally charged by information with the crime of rape

under Ark.Stat. §41-3401 (1947).

No warrant for petitioner’s arrest was issued prior to

November 7th when petitioner was formally charged, and

a warrant to search petitioner’s home was never procured.

On November 3rd, while petitioner was held at the Hot

Springs City Jail, police officers combed petitioner’s hair

and obtained a nylon thread from his hair, as well as a

specimen of his hair. The police officers obtained clothing

from petitioner’s person, as well as his home. Petitioner

was not permitted to see his parents or a lawyer, and ac

cording to petitioner, he was mistreated and coerced into

signing a confession. Petitioner now argues that the ar

rest, and the search of his person and home were illegal

and constitute a violation of his constitutional rights.

(a) Petitioner’s Arrest Without A Warrant

[1] The lawfulness of petitioner’s arrest without a war

rant must be determined by the law of Arkansas, subject

to the test of reasonableness under the Fourth and Four

teenth Amendments to the United States Constitution.

Ker v. California, 374 U.S. 23, 40, 83 S.Ct. 1623, 10 L.Ed.2d

726 (1962). In Arkansas, it is provided by statute that an

arrest without a warrant is authorized where the arresting

officer has reasonable grounds for believing that the person

arrested has committed a felony. See Ark.Stat. § 43-403

(1947). The Arkansas Supreme Court has held that where

a felony has in fact been committed, an arrest without a

warrant may be made where the officer has reasonable

grounds to suspect the particular person arrested. Carr

v. State, 43 Ark. 99 (1884). Knight v. State, 171 Ark. 882,

286 S.W. 1013 (1926). Lane v. State, 217 Ark. 114, 229

Opinion of District Court

34a

S.W.2d 43 (195(X). Trotter and Harris v. State, 237 Ark.

820, 377 S.W.2d 14 (1964).

At the time of petitioner’s arrest, the fact that a felony

had been committed was clearly established. Miss Stella

Spoon had been brutally raped and her 90 year old father

with whom she resided had been mercilessly struck and

left bleeding when he attempted to aid her. Miss Spoon

had given a description of her assailant to Officer Pettis,

the Negro city policeman, and had further told him that

her assailant had said that his name was “Willie C. Wash

ington” .2 The first suspects brought to the hospital for

Miss Spoon to identify were Willie C. Washington, Sr.,

Willie C. Washington, Jr., and another Negro. Miss Spoon

told Officer Pettis that none of these individuals was her

assailant, but she gave Pettis some additional descriptions

which she was better able to do by comparison of her

attacker with Willie C. Washington, Jr. Officer Pettis then

indicated to Miss Spoon and the other policemen in her

room that he knew the identity of her assailant. Petitioner

was then taken into custody and was the next person

brought to Miss Spoon’s hospital room for her to identify.

When petitioner was brought into Miss Spoon’s hospital

room, according to the testimony of Officer Timms at the

state court trial, Miss Spoon “ * * * started shaking and

drawing herself up and shaking real bad,” 3 but she did not

then identify petitioner as her attacker. When asked by

petitioner’s counsel in the state court trial why she did not

immediately in her room identify petitioner as her as

sailant, Miss Spoon responded: “Because I had been

2 The details of the identification are set out in the transcript of Miss

Spoon’s testimony taken at the hearing on the habeas corpus proceeding.

See also Record, Vol. II, pp. 286-290, Maxwell v. State, 236 Ark. 694,

370 S.W.2d 113 (1963) (hereinafter cited as State Court Record).

3 State Court Record, Vol. II, pp. 312 and 313.

Opinion of District Court

35a

threatened, my father had been threatened. I don’t know

legal procedure, I didn’t know whether they could hold him

or not, and if he happened to break and get loose or some

thing, he would do like he said he would, just get a gun

and come back and kill us. I didn’t know how long I wras

going to stay in that hospital.” * On direct examination,

Miss Spoon testified that there was not any possible doubt

in her mind that petitioner was her attacker.6

[2] The conclusion is compelling that petitioner was ar

rested with reasonable cause and that therefore the arrest

without a warrant was lawful under the circumstances. The

police were benefited by a description given by Miss Spoon

as to the size, complexion and clothes of her assailant.

Officer Pettis was undoubtedly familiar with the Negro

community. He had seen petitioner that night on the

avenue and his description matched the one given by Miss

Spoon. Petitioner, known to the police as “Plunk” , had

previously experienced difficulties with the police, and peti

tioner personally knew Officer Pettis. His home was near

the place of attack, as well as the victim’s home.

(b) The Search of Petitioner’s Person

[3, 4] It is settled law that a search of the person or

premises incident to a lawful arrest is permissible. Preston

v. United States, 84 S.Ct. 881 (1964). Iver v. California,

supra. Brinegar v. United States, 338 U.S. 160, 69 S.Ct.

1302, 93 L.Ed. 1879 (1948). United States v. Iacullo, 226

F.2d 788 (7th Cir. 1955). See also Commonwealth v.

Holmes, 344 Mass. 524, 183 N.E.2d 279 (1962), and cases

collected in Annot., 89 A.L.R.2d 715, 780-801 (1963). Since 4 5

Opinion of District Court

4 State Court Record, Yol. II, p. 280.

5 State Court Record, Yol. II, pp. 263, 264, and 268.

36a

the arrest without a warrant was lawful under the circum

stances, it follows that the evidence obtained from the

clothes removed from petitioner’s body and the thread and

hair taken from petitioner’s head were not illegally ob

tained. See United States v. Iacullo, supra, 226 F.2d at

792, discussing United States v. Di Re, 332 U. S. 581, 68 S.Ct.

222, 92 L.Ed. 210 (1948); and Draper v. United States,

358 U.S. 307, 79 S.Ct. 329, 3 L.Ed.2d 327 (1958). United

States v. Cole, 311 F.2d 500 (7th Cir. 1963), cert, denied

372 U.S. 967, 83 S.Ct. 1092, 10 L.Ed.2d 130 (1963).

The items obtained from petitioner at the Hot Springs

City Jail, i. e., a hair from his head, a strand of nylon

thread found in his hair, and his clothing, were necessary

to a thorough investigation of the offense with which peti

tioner was charged and the obtaining of these items in the

course of the investigation was a reasonable procedure un

der the circumstances. According to Miss Spoon’s report,

her attacker had worn a nylon stocking on his head which

came off as the attacker attempted to pull it over his face.

The police had found a nylon stocking near the victim’s

house in the vicinity where the attack had occurred. Fur

thermore, the clothing worn by petitioner had seminal

stains, as well as blood stains. These items, along with

others, were sent to the Federal Bureau of Investigation

laboratories in Washington, D. C., for scientific analysis.

(c) The Search of Petitioner’s Home

Petitioner argues that the police officers conducted an

illegal search and seizure in obtaining a blue coat from

his home after petitioner was arrested. The coat was ob

tained by Captain Crain from petitioner’s mother and it

was used as evidence in the state court trial. (Certain

clothes obtained by Officer Timms from petitioner’s mother

Opinion of District Court

37a

on a second trip back to the house were merely a con

venient change of clothes for the ones obtained from peti

tioner at the City Jail and were not used as evidence.)

Admittedly, the blue coat was obtained without a search

warrant.

In the state court trial, Captain Crain testified that he

obtained the coat with the permission of petitioner’s mother,

and this was not disputed at the state court trial despite

the fact that petitioner’s mother was in the court room and

heard this testimony.6 At the hearing on the instant peti

tion, Captain Crain again testified that he explained to

petitioner’s mother that he wished to get the clothes worn

by petitioner that night and that she took him to peti

tioner’s room and showed him the closet where the coat

was hanging. Captain Crain informed petitioner’s mother

that petitioner had been accused of committing rape. Peti

tioner’s mother, age 40, testified that petitioner lived there

with his parents and occupied a room with his two brothers.

At the time of the search, petitioner’s father was at work

and petitioner’s two brothers were in bed asleep. Peti

tioner’s mother further stated in substance at the hearing

on the instant petition that she did not know anything

about a search warrant and did not object to the police

coming into her home since she did not think anything was

wrong and there was no reason not to cooperate. On cross-

examination, petitioner’s mother stated: “I didn’t never

say that I didn’t grant permission.”

The evidence not only reflects that petitioner’s mother

freely and voluntarily consented to the police officer taking

the coat, but she also cooperated with the officer to the

extent that she showed the officer where the coat was lo

Opinion of District Court

6 State Court Record, Vol. II, pp. 333 and 334.

38a

cated. The coat was obtained less than an hour after peti

tioner was arrested. The search itself was not a general

exploratory search of the entire house, nor was it a rigorous

search. The police officer simply requested to see the clothes

which petitioner had worn that night and petitioner’s

mother permitted the police to enter her house and accom

panied the police to petitioner’s room and directed them

to the closet. The analysis made by the Federal Bureau

of Investigation at the laboratory in Washington, D. C., es

tablished that the blue-black woolen fibers in the nylon

stocking found near Miss Spoon’s house, as well as the

blueblack fibers found in Miss Spoon’s pajamas, came from

this coat taken from the closet.7

[5-7] Of course, petitioner’s state court conviction can

not be based upon evidence obtained in violation of the

Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution and

contravening the Fourteenth Amendment due process

clause. Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643, 81 S.Ct. 1684, 6

L.Ed.2d 1081 (1961). However, the protection of the

Fourth Amendment prohibits only those searches which are

“ unreasonable” . United States v. Rabinowitz, 339 U.S. 56,

70 S.Ct. 430, 94 L.Ed. 653 (1950); and a search and seizure

are not deemed to be unreasonable and therefore unlawful

if based upon a valid consent freely and understandably

given. Foster v. United States, 281 F. 2d 310 (8th Cir.

1960). See also United States v. Roberts, 223 F.Supp. 49

(E.D.Ark.1963). Yet, ultimately, the reasonableness of any

search depends upon the facts and circumstances of each

case. United States v. Rabinowitz, supra, 339 U.S. at 63,

70 S.Ct, 430, 94 L.Ed. 653.

Opinion of District Court

7 State Court Record, Vol. II, p. 359.

39a

It would unduly burden this opinion to attempt to analyze

the many cases involving consent to a search and seizure

of property or evidentiary material. These cases are fully

discussed by Chief Judge Henley in United States v. Rob

erts, supra, 223 F.Supp. at 58 and 59, in which the court ob

serves that there is no hard and fast rule but rather the

determination in each case is based upon a consideration

of all of the surrounding facts and circumstances, includ

ing the validity of the consent. Only recently, the United

States Supreme Court in Stoner v. California, 84 S.Ct. 889

(1964) rejected the argument that the search of a hotel

room, although conducted without the consent of the ac

cused, was lawful because it was conducted with the consent

of the hotel clerk. Similarly, the Supreme Court has refused

to permit the unlawful search of a hotel room to rest upon

the consent of the hotel proprietor, Lustig v. United States,

338 U.S. 74, 69 S.Ct. 1372, 93 L.Ed. 1819 (1949), or a hotel

manager, United States v. Jeffers, 342 U.S. 48, 72 S.Ct.

93, 96 L.Ed. 59 (1951); and a search of a tenant’s room with

the consent of the owner of the house has been held un

constitutional, Chapman v. United States, 365 U.S. 610, 81

S.Ct. 776, 5 L.Ed.2d 828 (1961), as well as a search of an

occupant’s room in a boarding house, McDonald v. United

States, 335 U.S. 451, 69 S.Ct. 191, 93 L.Ed. 153 (1948).

However, all of these cases are distinguishable from the

instant case in which petitioner merely shared a room with

his two brothers in his parents’ home.

In Stoner v. California, supra, the Supreme Court dis

cussed the argument that the search of the defendant’s

room was justified by the hotel clerk’s consent and con

cluded :

“ It is important to bear in mind that it was the peti

tioner’s constitutional right which was at stake here,

Opinion of District Court

40a

and not the night clerk’s nor the hotel’s. It was a right,

therefore, which only the petitioner could waive by

word or deed, either directly or through an agent. It is

true that the night clerk clearly and unambiguously

consented to the search. But there is nothing in the

record to indicate that the police had any basis what

soever to believe that the night clerk had been author

ised by the petitioner to permit the police to search the

petitioner’s room.” (emphasis added)

[8] The evidence adduced at the hearing on this peti

tion, as well as the record from the state court trial, clearly

and positively establishes that petitioner’s mother freely,

voluntarily, intelligently and understandingly consented to

and authorized the search made by Captain Crain to obtain

the blue coat. The search was made in her home at a time

when the premises were under her sole control and she had

the right to exclude whomever she chose, even including

the petitioner. Petitioner’s mother had the authority to

permit the police or anyone else to enter petitioner’s room

and examine the clothes in the closet. In the language of the

Supreme Court in Stoner, the police did have a “basis * * *

to believe that * * * [petitioner’s mother] *' * * had been

authorized by the petitioner to permit the police to search

the petitioner’s room.” This is true not because of any

agency based upon the mother-son relationship, but rather

because petitioner’s mother, unlike petitioner himself, had

the sole control, power and, at the time, the superior right

to exclude others from not only her home but also from the

very room which petitioner shared with his two brothers,

and it was her free and voluntary choice to permit the po

lice to enter and search the closet.

Opinion of District Court

41a

It is the holding of this Court that the blue coat taken by

Captain Crain was obtained by a lawful search and seizure,