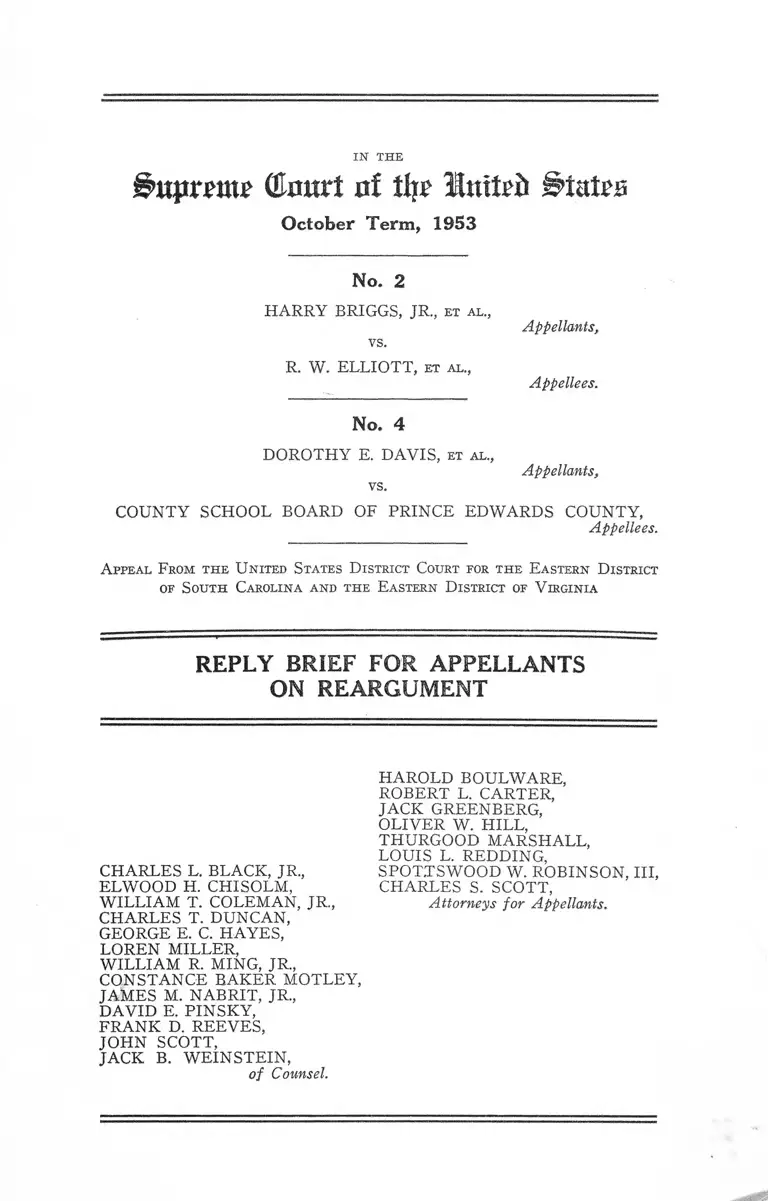

Briggs v. Elliot Reply Brief for Appellants on Reargument

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1953

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Briggs v. Elliot Reply Brief for Appellants on Reargument, 1953. 9dee5e6f-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1c8e9cda-114f-4ccd-8bd9-6a7bdf71aedc/briggs-v-elliot-reply-brief-for-appellants-on-reargument. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

CEmtrt at % Wnxtvb

October Term, 1953

No. 2

HARRY BRIGGS, JR., et al„

vs.

R. W. ELLIOTT, et al.,

Appellants,

Appellees.

No. 4

DOROTHY E. DAVIS, ex al.,

vs.

Appellants,

COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD OF PRINCE EDWARDS COUNTY,

Appellees.

A ppeal From the U nited States D istrict Court for the Eastern D istrict

of South Carolina and the Eastern D istrict of V irginia

REPLY BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

ON REARGUMENT

HAROLD BOULWARE,

ROBERT L. CARTER,

JACK GREENBERG,

OLIVER W. HILL,

THURGOOD MARSHALL,

LOUIS L. REDDING,

CHARLES L. BLACK, JR., SPOT.TSWOOD W. ROBINSON, III,

ELWOOD H. CHISOLM, CHARLES S. SCOTT,

WILLIAM T. COLEMAN, JR., Attorneys for Appellants.

CHARLES T. DUNCAN,

GEORGE E. C. HAYES,

LOREN MILLER,

WILLIAM R. MING, JR.,

CONSTANCE BAKER MOTLEY,

JAMES M. NABRIT, JR.,

DAVID E. PINSKY,

FRANK D. REEVES,

JOHN SCOTT,

JACK B. WEINSTEIN,

of Counsel.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. Appellees’ mistaken approach to the history of

the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment . . . . 2

II. Appellees’ mistaken concept of the decisions of

this C ou rt................................................................. 6

III. Appellees’ classification argument...................... 7

IV. Appellees have an erroneous conception of state

understanding and contemplation concerning the

effect of the 14th Amendment with respect to seg

regated schools........................................................ 12

V. Local customs, mores and prejudices cannot pre

vail against the Constitution of the United States 18

Conclusion ........................................................................ 24

Appendix A ................................................. 25

Appendix B— (Charts)

Table o f Cases

Adkins v. Sanford, 120 F. 2d 471 (CA 5th 1941).......... 4

Betts v. Brady, 316 U. S. 455 ......................................... 4

Blair v. Cantey, 29 S. C. L, (2 Spears) 3 4 ..................... 14

Bolling v. Sharpe, et al., No. 8 ........................................ 25

Bolin v. Nebraska, 176 U. S. 8 3 ...................................... 15

Bute v. Illinois, 333 U. S. 640 .......................................... 4

Commonwealth v. Williamson, 30 Leg. Int. 406 (1873).. 16

Coyle v. Smith, 221 U. S. 569 .......................................... 15

District Township v. City of Dubuque, 7 Iowa 262

(1858) ............................................................................ 13

Doswell v. Buchanan, 3 Leigh (Va.) 365 ....................... 14

Elkinson v. Delisseline, 8 Fed. Cas. 493 (C. C. S. C.

(1823)) .......................................................................... 19

Gebhart v. Belton, No. 1 0 ................................................. 20

Gilbert v. Minnesota, 254 U. S. 325 ............................... 5

Gitlow v. New York, 268 U. S. 652 .................................. 4, 5

PAGE

11

Hurtado v. California, 110 U. S. 5 1 6 ............................. 4

Johnson v. Zerbst, 304 U. S. 458 .................................... 4

Legal Tender Cases, 12 "Wall. 457 .................................. 3

McKissick v. Carmichael, 187 F. 2d 949 (CA 4th. 1951),

cert, denied, 341 U. S. 9 5 1 .......................................... 11

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U. S.

637 .............................................................. 6,7,11,19,20,23

Marlin v. Lewallen, 276 U. S. 5 8 ...................................... 14

M ’Culloch v. Maryland, 4 Wheat. 3 1 6 ........................... 4

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337 .......... 7

Ohio ex rel. Clarke v. Deckeback, 274 U. S. 392 ........... 9

Patsone v. Pennsylvania, 232 U. S. 1 3 8 ....................... 9

Patterson v. Colorado, 305 U. S. 454 .............................. 4

Permoli v. New Orleans, 3 How. 589 ............................. 15

Powell v. Alabama, 287 U. S. 4 5 .................................... 4

Prudential Insurance Co. v. Cheek, 259 U. S. 530 ........ 5

Quaker City Cab Co. v. Pennsylvania, 277 U. S. 389 . . . 7, 8

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 .............................. 2,11, 23

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 631 .................... 7

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303 .................... 2

Stromberg v. California, 283 U. S. 359 ......................... 5

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629 .........................3, 6, 7,10, 20

Takahashi v. Fish & Game Commission, 334 U. S. 410 9

Tanner v. Little, 2401 U. S. 369 ...................................... 9

Walden v. Gratz, 1 Wheat. 292 ........................................ 14

Tick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356 ................................ 7, 8

State Constitutions and Statutes

Alabama Const., Art. XI (1867) .................................... 13

Alabama Const., Art. X I §6 (1867)................................ 13

Florida Laws 1866, c. 1475 .............................................. 14

Florida Laws 1866, c. 1486 .............................. 14

Iowa Const., Art. IX (1857) ............................................ 13

Iowa Const., Art. IX §12 (1857)...................................... 13

PAGE

North Carolina Const., Art. IX §§1-17 (1868)............. 16

South Carolina Laws No. 125 (1869) ............................. 17

South Carolina Acts & Res. 1868-69, pp. 203-204 .......... 17

Proceedings o f Constitutional Conventions

5 Elliot’s Debates, 435 ..................................................... 4

5 Elliot’s Debates, 543-4 .................................................. 4

Proceedings of the South Carolina Constitutional Con

vention, etc. 100-101, 264-272, 654-656, 685-708, 899-

901 ............................................................................. 17

Congressional Debates and Reports

Congressional Globe, 37th Cong. 2d Sess. 1544, 2037,

2157 (1862) .................................................................... 25

Congressional Globe,' 38th Cong. 1st Sess. 2814, 3126

(1864) ............................................................................. 25

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. (1866):

182, 183 .............................. 31

App. 217 .................................................................... 14

474 ........................................................................... 26

505 .................................. 26

541 .............................................................................. 26

570, 571 ....................................................................... 27

598 ................................................................................ 27

599 ............... 29

602 .............................................................................. 27

603 .............................................................................. 29

605 ............................................................................... 30

1094 et seq..................................... 33

1095 ............................................................................ 35

1296 ............................................................................ 30

I l l

PAGE

IV

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. (1866):

1415 ........................................................................ 32

2459 ...................................................................... 36,37,38

2502 ............................................................................ 38

2538 ............................................................................ 38

2542 ............................................................................ 39,

2764 ............................................................................ 40

2765 ................... 37

2766 ...........................................................................36,37

Cong. Globe, 40th Cong., 2d Sess. (1868):

2461 .......................... 33

2462 ............................................................................ 33

2477 ............................................................................ 33

Cong. Globe, 41st Cong. 3rd Sess. 1055 ............. .......... 15

2 Cong. Rec., App. 478 (1874) ...................................... 15

Kendrick, Journal of the Joint Committee of Fifteen

on Reconstruction 85-107 ............................................ 36

PAGE

Other Authorities

Brief for the Committee of Law Teachers, Sweatt v.

Painter, No. 44, Oct. Term, 1949, pp. 5-18 .._............. 3

Courts and Racial Integration in Education, The, 21

J. Negro Edue. 3 (1952) .............................................. 20

Fifth Annual Report State Supt. Educ.—1873, p. 15 .. 17

21 J. Negro Educ. 321 (1952) ...................................... 20

Johnson, Mr. Justice Wm. and the Constitution, 57

Harv. L. Rev. 328, 338 .................................................. 19

Noble, A History of the Public Schools in N. C. 312-313

(1930) ............................................................................ 16

Simpkins & Woody, South Carolina During Reconstruc

tion 439-440 (1932) ...................................................... 17

Special Groups, Special Monograph No. 10, Selective

Service System (1953) ...................................... 5, 21, 22, 23

Thayer, “ Legal Tender',” 1 Harv. L. R. 7 3 ................... 4

Wertham, Psychiatric Observations on Abolition of

School Segregation, 26 J. Ed. Soc. 336 (1953).......... 20

IN THE

CUimrt uf United UtateB

October Term, 1953

----------------------0----------------------

No, 2

H arry B riggs, J r., et al.,

Appellants,

vs.

R. W. E lliott, et al,,

Appellees.

No. 4

D orothy E . D avis, et al.,

vs.

Appellants,

County S chool B oard op P rince E dward

V irginia, et al.,

County,

Appellees.

A ppeals F rom the U nited S tates D istrict C ourts por

the. E astern D istrict of S outh Carolina and

the E astern D istrict of V irginia.

----------------------o— ---- -— -------- -

REPLY BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

ON REARGUMENT

This Reply Brief is a joint reply to the Briefs for Appel

lees on Reargument in No. 2 and No. 4.

In dealing wtih the Congressional debates on the Four

teenth Amendment appellees have made several errors in

text and quotations. In order to conserve the time of the

2

Court we have corrected the more important of these errors

in Appendix A to this brief. There is even more dispute

between appellants and appellees in regard to the actions

of the several states. In order to facilitate the Court’s

resolution of dispute of the states on the Fourteenth

Amendment we have prepared charts which are set forth in

Appendix B to this brief.

I

Appellees’ mistaken approach to the history of the

adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment.

We doubt that the decision in this case is to be con

trolled by any isolated statement in either the Congres

sional debates or statements of any individual legislator

in the states. On the contrary, we believe that the deter

mining factor must be the overall purpose and intent of

the framers of the Fourteenth Amendment1 plus the gen

eral understanding of this intent by the other members of

Congress. On this phase of the case, appellees have uni

formly disregarded the undisputed intent of the framers

of the Fourteenth Amendment to remove by constitutional

amendment all governmentally imposed racial classifica

tions and caste legislation and to do this in the most general

and comprehensive language as is customary in the wording

of constitutional provisions.2 Appellees have consistently

ignored the admitted intention of the framers of the

Fourteenth Amendment and the other Radical Republicans

in the 39th Congress that the Fourteenth Amendment would

destroy the validity of the Black Codes then in existence,

those being adopted during the same period, and would

deprive the states of power to adopt any similar racial

classification statutes in the future.

1 See Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, 23.

2 Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303, 310.

3

On this point the United States in its Supplemental

Brief on Reargument (p. 115) concluded:

“ In sum, while the legislative history does not

conclusively establish that the Congress which pro

posed the Fourteenth Amendment specifically under

stood that it would abolish racial segregation in the

public schools, there is ample evidence that it did

understand that the Amendment established the

broad constitutional principle of full and complete

equality of all persons under the law, and that it

forbade all legal distinctions based on race or color.

Concerned as they were with securing to the Negro

freedmen these fundamental rights of liberty and

equality, the members of Congres-s did not pause to

enumerate in detail all the specific applications of

the basic principle which the Amendment incorpo

rated into the Constitution. There is some evidence

that this broad principle was understood to apply

to racial discriminations in education, and that it

might have the additional effect of invalidating state

laws providing for racial segregation in the public

schools.” 3

The historic role of this Court has always been to give

specific content to constitutional guarantees of due process,

equal protection, the Bill of Rights and affirmative grants

of power in accordance with the fundamental and under

lying intent of the framers. That the framers may have

had or failed to have a specific problem in mind is after all

beside the point. What must be determined is whether the

particular problem is embraced within the broad scope of

the constitutional provision. And the Court resolves this

question.

Thus, this Court sustained the Legal Tender Acts, Legal

Tender Cases, 12 Wall. 457, in the face of the fact that the

3 See also: Brief for the Committee of Law Teachers Against

Segregation in Legal Education filed in the case of Sweatt v. Painter,

No. 44, October Term, 1949, pp. 5-18.

4

Constitutional Convention, in voting to strike out a provi

sion authorizing Congress to “ emit bills of credit,” clearly

understood that the Federal government would thereby be

deprived of this power. 5 Elliot’s Debates, 435;4 Thayer,

“ Legal Tender,” 1 Harv. L. B. 73. Likewise, in upholding

the establishment of the Bank of the United States in M ’Cul-

loch v. Maryland, 4 Wheat. 316, Chief Justice Marshall was

not deterred by the fact that the Constitutional Convention

had voted down a proposal to authorize the chartering of

corporations. 5 Elliott’s Debates, 543-4.

It should also be noted that the Sixth Amendment was

adopted in the light of the English common law rule that one

accused of a felony other than treason was denied the

assistance of counsel. See Powell v. Alabama, 287 U. S. 45,

60-64; Betts v. Brady, 316 U. S. 455; Adkins v. Sanford,

120 F. 2d 471 (CA 5th 1941). From the date of the adoption

of the Sixth Amendment until the decision of this Court in

Johnson v. Zerbst, 304 U. S. 458, the right conferred was

generally understood as meaning only that in the federal

courts the defendant in a criminal case was entitled to be

represented by counsel retained by him. See Bute v. Blinois,

333 U. S. 6401, 661, footnote 17. In Johnson v. Zerbst this

Court departed from this concept and construed the Amend

ment as entitling a defendant to court-appointed counsel if

unable to retain counsel of his own.

Moreover, from the time of the adoption of the Four

teenth Amendment until Gitlow v. New York, 268 U. S. 652,

666, the Fourteenth Amendment was not considered as a

prohibition against state invasion of freedom of speech.

The inclusion of this specific protection in the Fourteenth

Amendment was impliedly rejected in Hurtado v. California,

110 U. S. 516, 534, on the ground that none of the constitu

tional provisions was superfluous. In Patterson v. Colorado,

4 See particularly the speeches of Butler, Ellsworth, Reed and

Mason.

5

205 U. S. 454, the question was left open. In Gilbert v.

Minnesota, 254 U. S. 325, the Court refused to decide the

question, and in Prudential Insurance Co. v. Cheek, 259

U. S. 530, 543, it was expressly stated that the free speech

guaranty was not a part of the Fourteenth Amendment.

In the Gitlow case, the Court assumed the Fourteenth

Amendment protected this right, and in Stromberg v. Cali

fornia, 283 U. S. 359, a state statute restricting* the exercise

of free speech was struck down for the first time as viola

tive of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Whatever may be one’s views as to the propriety of this

judicial function, it is a fact of our constitutional system,

and explains why for over 150 years, in spite of revolution

ary social, economic and political changes, only eleven con

stitutional amendments have been necessary, aside from

the first ten amendments which were almost contemporane

ous to the adoption of the Constitution itself.

The significance of the legislative history of the Four

teenth Amendment is that there can be no doubt that the

framers were seeking to secure and to protect the Negro

as a full and equal citizen subject only to the same legal

disabilities and penalties as the white man. The Court

decisions in aid of this fundamental purpose, we submit,

compel the conclusion that school segregation, pursuant

to state law, is at war with the Amendment’s intent.

It is too late to say this is a question of local rather

than national interest. ‘ ‘ In every phase of living the United

States must demonstrate that the American way of life

exemplifies true democracy by eliminating majority-minor

ity division and distinctions, thus having the same citizen

ship privileges and obligations for all.” 6 5

5 Special Groups, Special Monograph #10, Selective Service

System (page 192), (1953).

6

Appellees’ mistaken concept of the decisions o f this

Court.

In arguing that it is not within the judicial power of

this Court to construe the Fourteenth Amendment as abol

ishing public school segregation, appellees in No. 2 (Br.

56-80), while recognizing that “ the function of the Court

is to interpret the language under scrutiny in accordance

with the understanding* of the framers,” follow this with

the assertion that “ the Fourteenth Amendment should be

interpreted so as not to include those subjects, and specifi

cally the issue of segregation in public schools, which the

framers clearly did not intend the language of the Amend

ment to embrace.” (See also Appellees’ Brief in No. 4,

pp. 42-46.) Such an argument is no more valid as respects

elementary and high school segregation than it was for

graduate school segregation.

Appellees in No. 2 apparently recognize this dilemma

and seek to escape the obvious by combining Sweatt v.

Painter, 339 U. S. 629 and McLaurin v. Oklahoma State

Regents, 339 U. S. 637 and asserting that neither case dis

turbed the separate but equal doctrine “ for in each case

the Court expressly found that the facilities offered to the

Negro student was unequal” (Br. p. 65). Similar conten

tion is made by appellees in No. 4 (Br. 58-62). In the

McLaurin case racial segregation in and of itself and with

out more was found a denial of equal protection.6

6 In the McLaurin case the single issue involved, i.e., the validity

of state-imposed racial segregation in graduate education; the under

lying rationale of the decision, i.e., state-imposed segregation destroys

equality of educational benefits; and the unmistakable language of

the opinion is more pertinent to the issue in these cases than quota

tions of statements of general principles of constitutional construc

tion in habeas corpus and tax cases.

II

7

In an effort to distinguish the McLaurin case, appellees

in No. 2 rely on statements in the majority opinion of the

Court below to the effect that education at the common

■school level is compulsory and that the state must there

fore take account of the wishes of the parent (Br. 67-68).

Compulsory public school education, rather than being a

distinguishing factor validating segregation, in fact high

lights the unconstitutionality of the laws in question. Here

the state requires the Negro parent solely because of his

race to subject his children to all of the known harmful

incidents of racial segregation under threat of imprison

ment.

Appellees in No. 4 seem to rely upon a statement by

Senator Trumbull that the right to go to public schools was

not considered a civil right at that time (Br. 29, 65, 126).

But the Gaines, Sipuel, McLaurin and Sweatt cases have

rendered the significance of this statement meaningless

with respect to public education as it exists today.

I I I

Appellees’ Classification Argument

Appellees in No. 2 argue that the laws here involved

are not unconstitutional classifications within the rules

established by this Court. ' ‘ Fundamental is the proposi

tion that the legislature may classify the subjects of legis

lation and treat different classes differently provided there

is a real and substantial, as distinguished from a fanciful

or arbitrary, basis for the classification and difference in

treatment. Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356 (1886);

Quaker City Cab Co. v. Pennsylvania, 277 U. S. 389 (1928) ”

(Br. pp. 70-71).

Both of the cases cited by appellees in fact destroy any

basis which they might have had for urging that statutes

8

of the type here involved are reasonable classifications

within the meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment.

“ And while this consent of the supervisors is

withheld from them and from two hundred others

who have also petitioned, all of whom happened to

be Chinese subjects, eighty others, not Chinese sub

jects, are permitted to carry on the same business

under similar conditions. The fact of this discrimi

nation is admitted. No reason for it is shown, and

the conclusion cannot be resisted, that no reason for

it exists except hostility to the race and nationality

to which the petitioners belong, and which in the

eye of the law is not justified. The discrimination is

therefore illegal, and the public administration which

enforces it is a denial of the equal protection of the

laws and a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment

of the Constitution. The imprisonment of the peti

tioners is therefore illegal, and they must be dis

charged.” Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356, 374.

“ In effect §23 divides those operating taxicabs

into two classes. The gross receipts of incorporated

operators are taxed while those of natural persons

and partnerships carrying on the same business are

not. The character of the owner is the sole fact on

which the distinction and discrimination are made

to depend. The tax is imposed merely because the

owner is a corporation. The discrimination is not

justified by any difference in the source of the re

ceipts or in the situation or character of the prop

erty employed. It follows that the section fails to

meet the requirement that a classification to be con

sistent with the equal protection clause must be

based on a real and substantial difference having

reasonable relation to the subject of the legislation.”

Quaker City Cab Co. v. Pennsylvania, 277 U. S. 389,

402.

This Court in 1916 in deciding another question involv

ing the power of a state to classify stated:

“ .. . Bed things may be associated by reason of their

redness, with disregard of all other resemblances or

9

of distinctions. Such classification would be logi

cally appropriate. Apply it further: make a rule

of conduct depend upon it, and distinguish in legis

lation between red-haired men and black-haired men,

and the classification would immediately be seen to

be wrong; it would have only arbitrary relation to

the purpose and province of legislation.” Tanner

v. Little, 240 U. S. 369, 382.

Appellees also rely on the caseiS restricting the right of

aliens to hunt and to operate poolrooms (Br. 73-74) in

support of the proposition that the racial distinctions in

public education are therefore valid. But Patsone v. Penn

sylvania, 232 U. S. 138 and Ohio ex rel. Clarke v. Deckeback,

274 U. S. 392, distinguish themselves. See Takahashi v.

Fish do Game Commission, 334 U. S. 410. Certainly, it is

not a valid argument that because a state law prohibiting

aliens from operating poolrooms has been held reason

able, that a state may, therefore, impose racial distinctions

on American citizens with respect to its public school

systems.

Appellees additional argument in No. 2 as to reason

ableness of school segregation laws (Br. 75-78) is merely

one of custom and tradition (Br. 75-78). This has been

dealt with in our brief-in-chief (pp. 42-43).

Appellees seek to justify compulsory racial segregation

on the grounds that “ segregation is the result of racial

feeling” and cannot be legislated out of existence” (Br.

75) ; that such an “ experiment” of non-segregation will

not work because the fear of mixed schools hampered the

development of public education in the last century (Br.

76 ) ; that prohibition of segregation would “ work an aboli

tion of virtually the entire school system” and would

therefore be “ absurd” (Br. 77); and that the people of

South Carolina did not want to abandon segregation.

Not only have these arguments been consistently and

unsuccessfully urged upon this Court in similar cases in

1 0

the past7 but in the Sweatt case respondents in addition

relied on testimony and the results of a Statewide Survey

of Public Opinion that 76% of the people polled were

opposed to “ Negroes and whites going to the same uni

versities.” 8

Appellees in No. 4 assert (Br. 66-75) the “ reasonable

ness” of the segregation requirement. They have reviewed

the testimony of their witnesses (Br. 69-73) in an effort

to support this contention. But we do not find in this testi

mony the elements which the general classification test

under equal protection clause demands of all state legis

lative and constitutional enactments.

All items of this testimony fall within one of two

categories:9 (1) those referring to long-standing “ cus

toms” and “ traditions” of Virginians, a consideration

already treated by appellants (Br. 42-43), and (2) opinions

as to the effects of school desegregation, both generally and

upon Negro students particularly.

As to the latter, there is substantial evidence to the

contrary.10 But more fundamentally, the considerations

urged cannot resolve the issue. So far as appellees’ posi

tion is predicated upon the assumption of an adverse com

munity reaction, it is a declaration that constitutional rights

characterized by this Court as personal and present can

be postponed until the community desires to honor them.

Clearly, the Constitution forbids such a subversion of

fundamental individual rights to inconsistent local policy.

7 Brief for Respondents in Sweatt v. Painter, No. 44, October

Term, 1949, pp. 92-98; see also Brief for Attorneys General of Several

Southern States filed in the same case.

8 Id. at 231.

9 The testimony of appellees’ witnesses in this connection is

summarized in appellants’ opening brief upon the original argument

(pp. 22-25).

10 Summarized in appellants’ opening brief upon the original

argument (pp. 18-22).

11

And so far as appellees’ position is based upon the

assumption that desegregation will not benefit Negro stu

dents—because, it is said, discriminations will be imposed

by individual white students—it fails to distinguish be

tween constitutionally permissible individual activity and

constitutionally proscribed governmental activity. See

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U. S. 637, 641-

642; Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, 13, 14.

Nor may it be assumed, as appellees seem to assume,

that the state may undertake to determine that appellants ’

best interest is served by continued school segregation.

That suggestion was made in MeKissick v. Carmichael, 187

F. 2d 949 (CA 4th 1951), cert, denied, 341 U. S. 951. There

the Court of Appeals said at pages 953-954:

. . the defense seeks in part to avoid the charge

of inequality by the paternal suggestion that it wTould

be beneficial to the colored race in North Carolina

as a whole, and to the individual plaintiffs in par

ticular, if they would cooperate in promoting the

policy adopted by the State rather than seek the

best legal education which the State provides. The

duty of the federal courts, however, is clear. "We

must give first place to the rights of the individual

citizens, and when and where he seeks only equality

of treatment before the law, his suit must prevail. It

is for him to decide in which direction his advantage

lies.”

The evidence does not establish, nor does it elsewhere

appear, that there are any differences between the races

of educational significance or that educational segre

gation subserves any valid educational objective. This is

the minimum standard which the equal protection clause

prescribes for all legislation (Appellants’ Br. 45-47), and

the segregation laws involved here fail to meet this test.

12

I V

Appellees have an erroneous conception of state

understanding and contemplation concerning the effect

of the 14th Amendment with respect to segregated

schools.

1. Appellees in No. 2, motivated by a desire to avert

any misleading of this Court by appellants, “ have found

a considerable number of errors—errors of omission and

of commission—in appellants ’ account of state action

regarding the Amendment and segregated schools” (App.

B at 4). Appellees in No. 4 have not been less diligent in

their editorial efforts. While there are a few paginal

errors in our citations which we will amend at the outset,

we were unable to discover any errors of substance in our

interpretation.

Appellees point out that they are unable to find sup

port for a statement made regarding the education article

of the Arkansas Constitution of 1868 in the treatise cited

by us as authority (Br. No. 2, App. B at 6-7; Br. No. 4 at

158). Appellants admit that the task of appellees would

have been made less onerous had the correct page references

been given: it is at pages 245, 250 of the cited treatise.

Similarly, appellees unearthed an incorrect paginal refer

ence in appellants’ documentation of the North Carolina

action (Br. No. 2, App. B at 39; Br. No. 4 at 191-192). The

reference in the cited treatise should be to pages 312-313.

2. Much importance is attached by appellees to their

conclusion that we have charged the late Confederate states

with having “ perpetrated a gigantic fraud on the United

States” (Br. No. 4 at 154. See Br. No. 2, App. B at 2).

Their design is obviously to detract from the significance

of the events which transpired in these states. Appellants

reply that history undeniably records the events. We

13

have attempted to dispassionately present the significant

action taken in these states, and respectfully submit that

the conclusion above is appellees’ own.

Appellees in these cases seem to contend that an answer to

the Court’s inquiry with respect to what the ratifying states

understood or contemplated the effect of the Fourteenth

Amendment to be rests primarily upon an examination of

the action or lack of action which the state legislatures and

conventions took to conform their school laws to the new con

stitutional mandate (Br. No. 2, App. B at 2; Br. No. 4 at 18,

150,151). We concur in this, but seriously disagree with ap

pellees’ conclusion, predicated upon such evidence, that no

legislature which ratified the Amendment contemplated or

understood that it would prohibit segregation in public

schools (Br. No. 2 at 48; Br. No. 4 at 26, 209-210). To us,

such a conclusion is on its face absurd. And, to create sup

port for this conclusion, appellees have substituted as bases

therefor accounts of the action of state legislative bodies

which are deceptive in stress and content.

3a. First, appellees charge that we have mistakenly char

acterized the education article of the Alabama Constitution

of 1867 as an “ anti-segregation article” (Br. No. 2, App.

B at 5). Appellants submit that the Alabama education

article was borrowed from the Iowa education article.

Compare Ala. Const., Art. X I (1867) with Iowa Const., Art.

IX (1857). And compare particularly Ala. Const., Art. XI

§ 6 (1867) with Iowa Const., Art. IX § 12 (1857). In 1857,

the Iowa Supreme Court struck down a statute which

irreeusably compelled segregated schools on the ground

that Article IX, section 12 of the Constitution prohibited

any distinction being made between white and colored

children. District Township v. City of Dubuque, 7 Iowa

262 (1858). When legislation is adopted from another state

the construction placed upon such legislation by the highest

court of the state from which it was taken is treated as

14

incorporated therein so as to govern its interpretation.

Marline. Lewallen, 276 U. S. 58, 62 and the cases there cited.

See Walden v. Grots, 1 Wheat. 292; Blair v. Cantey, 29

S. C. L. (2 Spears) 34; Doswell v. Buchanan, 3̂ Leigh (Ya.)

365. Thus, appellants deemed “ anti-segregation article”

an appropriate characterization of Article XI, section 6

of the Alabama Constitution of 1867.

b. Appellees imply that during the time of reconstruc

tion Florida did not provide for a free public school sys

tem for white students although public funds had been

appropriated for the education of Negroes (Br. No. 2, App.

B at 11; Br. No. 4 at 162, 163). There are two mis-state

ments here. Florida did maintain a system of public

schools for white students at the tim e;11 and Negroes, al

ready taxed for the support of these schools, had an addi

tional tax imposed upon them for the specific support of

their own schools.12 Furthermore, appellees ’ assertion that

Florida enforced segregated schools during the period

when state law omitted any sanction for segregated schools

(1868-1872) and when such schools were expressly for

bidden (1873-1887) is unsupported except by what appears

to be an unofficial statement of the Attorney General of

Florida (Br. No. 4 at 163-164).

c. Again, speaking of the development of public educa

tion under the provisions of the Louisiana Constitution of

1868 which forbade segregated schools, appellees state that

no effective school system was established while this con

stitution was in effect (Br. No. 2, App. B at 23; Br. No. 4

at 174). Appellants submit that authorities equally as

11 Fla. Laws 1866, c. 1486. Observe this was the same legisla

ture which provided for colored schools. See fn. 4, infra.

12 Fla. Laws 1866, c. 1475. See Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st

Sess., App. 217 (1866). (Remarks of Senator Howe)

15

reliable as those cited by appellees positively contradict

this statement.13

d. Appellees’ treatment of Nebraska’s understanding

(Br. No. 2, App. B at 32-33; Br. No. 4 at 182-183), ignores

the fact that Nebraska entered the Union pursuant to the

“ fundamental and perpetual condition” maintained in the

Enabling Act of February of 1867 that there shall be no

abridgement or denial of the exercise of the elective fran

chise, or any other right, to any person by reason of race

or color. . . . ” (emphasis supplied). 14 Stat. 377. Pur

suant to this requirement, Nebraska effectively repealed

the laws which formerly had apparently excluded Negroes

from public schools and neither by statute nor in practice

sanctioned racial segregation in public schools subsequent

to its ratification of the Amendment. The legal significance

of this flows from Nebraska’s apparent understanding that

any restriction upon Negroes’ full enjoyment of a public

education, i.e., by exclusion or mandatory segregation or1

permissive segregation, would be a denial of a right by

reason of race or color and violative of the Fourteenth

Amendment which they ratified in conformity with the

fundamental condition. Furthermore, the imposition of

this condition did not exceed congressional authority.

Bolin v. Nebraska, 176 U. S. 83, 87. It was apparently jus

tified as a requirement which would put Nebraska on an

equal footing with the original states and cannot be viewed

as solely referrable to Nebraska. See Coyle v. Smith, 221

U. S. 569; Permoli v. New Orleans, 3 How. 589.

e. To imply that the North Carolina Constitution of

1868 provided for segregation in public schools, as appel

lees do (Br. No. 2, App. B at 39; Br. No. 4 at 188) is a

misleading half-truth. The education articles specifically

13 2 Cong. R ec., App. 478 (1874). (Statement of Rep. Darrall of

Louisiana). See remarks of Sen. Harris of Louisiana. Cong.

Globe, 41st Cong., 3rd Sess. 1055.

16

refrained from any intimation of a racial distinction in the

establishment of public schools and contains no authoriza

tion therefor.14 Appellees similarly report only part of the

story when they asert that, within two weeks of the legisla

ture’s ratification of the Amendment, both houses adopted

a resolution which directed the joint assembly to provide

a system of free schools “ but that the races should be

segregated” (Br. No. 2, App. B at 40; Br. No. 4 at 189).

Diligent research by a well known authority on public

schools in the state reveals that such a resolution was

adopted in the lower chamber but that the upper chamber

deleted the segregation proviso and concurred only in so

much of the resolution as instructed the board of education

to prepare and report a plan for the organization and

maintenance of public schools.15

f. In Pennsylvania, appellees report that subsequent

to the state’s ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment,

segregation was upheld when attacked on constitutional

grounds in 1873 (Br. No. 2, App. B at 44-45; Br. No. 4 at

194). Appellees’ authority for this statement is Common

wealth v. Williamson, 30 Leg. Int. 406 (1873). It is our

understanding that this case arose when the school directors

of Wilkes-Barre united two districts, each having less than

twenty Negro children, and established a single school for

Negroes. The Court held that this was a violation of the

law of 1854 which required separate schools only where

twenty or more colored pupils were available in a school

district.

g. Appellees admit that the South Carolina legislature

extended the prohibition against segregation in public

schools to preclude segregation in the University of South

14 See N. C. Const., Art. IX, §§ 1-17 (1868).

15 N oble, A H istory of the P ublic Schools in N orth Caro

lin a 312-313 (1930).

17

Carolina16 and that the state superintendent of schools

sought to enforce total non-segregation at the State In

stitution for the Deaf, Dumb and Blind.17 Whether these

actions contradicted appellees’ conclusion that there was

“ no real effort to require amalgamated schools” (Br. No.

4 at 199; Br. No. 2, App. C passim) may not be decisive.

But one cannot review the debates of the Constitutional

Convention of 1868 and concur in appellees’ conclusion

that the framers of that instrument did not think that the

Fourteenth Amendment prohibited mandatory segregated

schools.18 Apposite to appellees’ inference that racially

integrated schools were the exception in South Carolina,

appellants here take the position that voluntary segrega

tion on the part of Negro pupils is not inconsistent with

absolute prohibition of any compulsory racial separation

in public schools.

h. Finally, appellees so present their evidence with

respect to California (Br. No. 2, App. B at 7-9; Br. No. 4

at 159-160), Illinois (Br. No. 2, App. B at 15-16; Br. No. 4

at 165-167), Indiana (Br. No. 2, App. B at 16-19; Br. No. 4

at 167-170), Ohio (Br. No. 2, App. B at 41-42; Br. No. 4 at

190-192) and Pennsylvania (Br. No. 2, App. B at 43-45;

Br. No. 4 at 192-194) that they obscure the fact that the

post Amendment development of legislation in these states

unequivocally demonstrates a trend away from racial ex

clusion and separation by force of law. It is submitted

that this conclusion is inevitable when comparison is made

with appellants ’ effort to more fully present in chronologi

16 S. C. Laws No. 125 (1869); S. C. Acts & Res. 1868-69, pp. 203-

204.

17 Fifth Annual Rep. State Supt. Educ.— 1873, p. 15. See S im p -

kins and W oody, South Carolina D uring R econstruction 439-

440 (1932).

18 Proceedings of the Constitutional Convention, etc. 100-

101, 264-272, 654-656, 685-708, 899-901.

18

cal sequence all the school legislation enacted in these

states during the pertinent period.

4. In sum, we submit that appellees’ treatment

of the state ratification aspect of Question One contains

serious omissions and unfortunate distortions of subject

matter. In contrast we invite the Court’s attention to the

treatment of this question in the brief of the United States

as Amicus Curiae on reargument.

For the convenience of the Court we have set forth in

Appendix B, a graphic summary highlighting all the ma

terials we could find. We submit that the available evidence

amply supports our original conclusion that the states

which ratified the Fourteenth Amendment understood and

contemplated that it prohibited segregated schools.

V

Local customs, mores and prejudices cannot pre

vail against the Constitution of the United States.

Despite the technical argument of appellees on the

intent of the framers of the Fourteenth Amendment, of the

39th Congress and the state legislatures, the burden of

their argument begins and ends with the proposition that

their police power, their mores and customs, and alleged

racial prejudices are so paramount as to suspend any neces

sity for application of the general test of reasonableness to

their school segregation laws and to justify non-compliance

with the admitted intent and purpose of the Fourteenth

Amendment—to destroy all state imposed class distinctions.

The truth of the matter is that this is an attempt to place

local mores and customs above the high equalitarian prin

ciples of our Government as set forth in our Constitution

and particularly the Fourteenth Amendment.

19

This entire contention is tantamount to saying that the

vindication and enjoyment of constitutional rights recog

nized by this Court as present and personal can he post

poned whenever such postponement is claimed,to be socially

desirable. We need go no further than McLcmrin v. Okla

homa State Regents, supra, to learn that this exalta

tion of local policy over fundamental individual rights

declared in the Federal Constitution is not tolerable in the

United States.

And there are striking and persuasive analogies in other

situations where local policy has been urged to minimize

or override individual constitutional rights. More than a

hundred years ago South Carolina attempted to prevent

the free movement of Negro seamen into and about its

seaport cities on the ground that domestic order and tran

quility required their exclusion. Justice Johnson,19

sitting on Circuit in South Carolina in 1823 did not hesitate

to overrule this defense and condemn the restriction as

unconstitutional. Elkinson v. Delisseline, 8 Fed. Cas. 493

(C. C. S. C. 1823). He disposed of this argument at page

496 as follows:

“ But to all this the plea of necessity is urged;

and of the existence of that necessity we are told

the state alone is to judge. Where is this to land

us? Is it not asserting the right in each state to

throw off the federal Constitution at its will and

pleasure? If it can be done as to any particular

article it may be done as to all; and, like the old

confederation, the Union becomes a mere rope of

sand. . . .”

The present apprehensions of South Carolina and Virginia

have no better standing to impede appellants’ enjoyment of

their constitutional right to be relieved of the educational

19 See: Mr. Justice William Johnson and the Constitution, 57

Harv. L. Rev. 328, 338.

2 0

disadvantages which those states have imposed upon them

solely because of their color.

The realistic answer to the contentions of appellees

is that, despite the dire predictions of the attorney generals

of 12 southern states in the Sweatt case, in less than two

years after this Court decision in the Sweatt and McLaurin

cases over 1500 Negro students had been enrolled in for

merly all white state, graduate and professional schools in

twelve of the southern states.20 It is perhaps more signi

ficant that “ [pjrivate institutions in eight states (Georgia,

Kentucky, Louisiana, Texas, Maryland, West Virginia, Vir

ginia and Missouri) and the District of Columbia have

revised their admission policies and admitted Negro stu

dents. In an institution in one state there were 251 Negro

students registered and five Negro teachers on the faculty.

“ Editorial Comment: The Courts and Bacial Integration

in Education,” 21 J. Negro Ed. 3 (1952).

Even closer is the fact that in the companion case of

Gebhart v. Belton, No. 10, Negro students have been ad

mitted to heretofore all white schools without untoward

incident. A recent survey by one of the witnesses for

respondents in the Gebhart case reveals that: 21

“ Summarizing- these observations, one can say

that the abolition of segregation removes a handicap

that interferes with the self-realization and social

adjustment of the child. The much-predicted ill

effects of such a step did not eventuate. As one

parent put it: ‘ If they’d leave it to the children

themselves it would be alright. It is really only what

the older people say that makes it harder for chil

dren to get along with other children. ’ ’ ’

2»21 J. Negro Educ. 321 (1952).

21 W ertham , Psychiatric Observations on Abolition of School

Segregation, 26 J. Ed. Soc. 336 (1953).

21

Local mores and customs and local political expediencies

not only should not prevail but cannot exist in the presence of

the overriding national and international need for the full

est reserve of manpower in time of war. A recent report

issued this year by the Selective Service System points up

in much detail the experience of our Government in trying

to overcome the handicap to our national war effort as a

result of segregation and other modes of discrimination in

public education in the South.

On the question of education, this report finds that:

“ The question as to whether or not one com

munity, county or State provides adequate educa

tional opportunities is a matter of concern for all of

the citizens in all of the States. Communities, coun

ties and States with high educational standards are

compelled to absorb the manpower procurement defi

ciencies of States with poor educational programs.

In the final analysis, the former actually pay in lives

for the educational deficiencies of the latter. The

safety of the Nation depends in a large measure upon

citizens in every State and section having a reason

able minimum of education.

“ In consequence, the following statement has sig

nificance for the extent to which low educational

standards are a national liability in time of war:

Educational deficiency, or failure to pass Army

intelligence tests primarily because of educational

deficiency, has deprived our armed forces of more

physically fit men than have the operations of the

enemy. Total American war casualties as of the last

official announcement were 201,454; total rejected for

failure to pass Army intelligence tests primarily be

cause of educational deficiency who have no other

disqualifying defect have been about 240,000. ’ ’ 22

22 Special Groups, Special Monograph No. 10, Selective Service

System, p. 166 (1953).

This report recognizes as one of the involved problems

standing between our Government and full and complete

mobolization in the time of future emergency.

“ Educational levels and backgrounds of minority

registrants plagued Selective Service, the armed

forces and industry alike, with no adequate solution

resulting. Modern mechanized civilization requires

a minimum basic educational level which often had

not been attained by the racial minority registrant.

Here again his cultural background contributed

heavily. Substandard schools, equally poor physical

facilities, teachers with inadequate preparation and

a lower per capita expenditure of school funds, all

common throughout the South, were foremost among

the factors creating this condition.

When these are coupled with morale factors,

which are the inescapable concomitants of racial dis

crimination and segregation, the obvious result

placed the Negro registrant at a marked disadvan

tage even before his preinduction examination. He

was discriminated against in the civilian life he was

soon to leave, and according to reports of prior in

ductees, he was to meet new and greater problems in

the armed forces. Furthermore, industry presented

the same ‘ closed door, no opportunity’ problem to

both those with skills and those with aptitudes quali

fying them for apprentice training in essential war

work. ’ ’ 23

The same monograph includes among its recommenda

tions the following:

“ In the event of war or otherwise, all American

citizens must be treated alike in the operation of

Selective Service regardless of national origin.

It ought to be stressed that the maximum use of

manpower in a national emergency can best be ob

tained through integration. A method which re

quires the use of men on the basis of racial separa

2 2

23 Id. at page 189.

23

tion tends to defeat its own purposes and racial

quotas in industry, agriculture and the armed forces

are difficult of justification.

“ There needs to be greater recognition of the

‘ physical, educational and social’ problems encoun

tered during the operation of the 1940 Act with ref

erence to registrants of minority racial groups and

the development of a long-range planning program

that will ultimately resolve these ills and assist such

minorities to have the same opportunities as other

citizens. Remedial measures properly applied with

out delay should show benefits in the increased size

of the total manpower pool and net additional man

power which may be badly needed in the event of

another major war.” 24

The gravamen of appellees ’ argument is that as a matter

of policy, legislative or otherwise, the people of South

Carolina and Virginia desire that all Negroes be excluded

from the white schools and vice versa. They also assert

that the removal of racial segregation in public education

will not be acceptable to the people of South Carolina and

Virginia. The individual rights of the appellants herein

cannot be made dependent upon this reasoning. This Court

stated in the McLaurin case:

“ It may be argued that appellant will be in no

better position when these restrictions are removed,

for he .may still be .set apart by his fellow students.

This we think irrelevant. There is a vast difference

—a Constitutional difference— between the restric

tions imposed by the state which prohibit the intel

lectual commingling of students, and the refusal of

individuals to commingle where the state presents

no such bar. Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, 13, 14,

92 L. ed. 1161, 1180, 1181, 68 S. Ct. 836, 3 ALE 2d

441 (1948). The removal of the state restrictions

will not necessarily abate individual and group pre

dilections, prejudices and choices. But at the very

least, the state will not be depriving appellant of the

2* Id. at 191.

24

opportunity to secure acceptance by his fellow stu

dents on his own merits. ’ ’

It bears repeating that appellants in these cases are only

seeking to remove the barrier of state-imposed racial segre

gation in the educational opportunities and benefits offered

by these states.

CONCLUSION

W e respectfully submit that, for the reasons stated

herein and in appellants’ other briefs, the decrees of

the District Courts should be reversed.

H arold B oulware,

R obert L . Carter,

J ack Greenberg,

Oliver W . H ill ,

T hurgood Marshall,

L ouis L . R edding,

Spottswood W . R obinson, III,

Charles S. S cott,

Attorneys for Appellants.

Charles L. B lack , J r .,

E lwood H . Chisolm ,

W illiam T. Coleman, Jr.,

Charles T. D uncan ,

George E . C. H ayes,

L oren M iller,

W illiam R . M ing, J r .,

C onstance B aker M otley,

J ames M. N abrit, J r .,

D avid E . P in sky ,

P rank D. R eeves,

J ohn S cott,

J ack B. W einstein ,

of Counsel.

25

Appendix A

Appellees put great stress on the action of the 39th Con

gress in regard to schools in the District of Columbia:

“ The Establishment of Separate Schools for Negroes in the

District of Columbia Before the End of the Civil W ar”

(Br. No. 2, App. A, at 2, 3 ); “ Attempts to Require Mixed

Schools in the District of Columbia” (Br. No. 2, 52-55);

“ The Early District of Columbia Schools” (Br. No. 4, 86-

87). The action of Congress in regard to schools in the

District of Columbia is not material to a determination

of the intent of Congress as regards the Fourteenth Amend

ment. The 39th Congress considered the District of Colum

bia school situation perfunctorily, as routine business, with

little debate and practically no discussion of note.1 There

is nothing in any of the debates on these measures to

indicate that Congress contemplated or understood that

the Fourteenth Amendment did not prohibit segregated

schools.2

Appellees argue that the debates on the Freedmen’s

Bureau Bill do not support a conclusion that the civil rights

referred to in the Bill included the right to attend segregated

schools (Br. No. 2, App. A, at 3-11; Br. No. 4, 87-90).

It is clear that several members of the Congress oppos

ing the Freedmen’s Bureau thought that the bill would be

used to promote mixed schools and that the Bureau was

already doing this. Representative John L. Dawson of

Pennsylvania, one of the opponents to the bill, made this

clear in his statement on January 31, 1866: “ . . . They

[the Radicals] hug to their bosoms the phantom of Negro

1 See also Cong. Globe, 37th Cong., 2d Sess. 1544, 2037, 2157

(1862); Cong. Globe, 38th Cong., 1st Sess. 2814, 3126 (1864).

2 For a complete discussion of this point see Brief for Petitioners

in Bolling v. Sharpe, et al., # 8 , pp. 23-46.

26

equality. . . . They hold that the black and white races are

equal. This they maintain involves and demands . . . that

Negroes should be received on an equality in white families

. . . their children are to attend the same schools with white

children, and to sit side by side with them. . . . ’ ’ 8

Appellees in No. 4 (Br. 91) make the assertion that Sena

tor Trumbull of Illinois pointed out that the Civil Rights Act

of 1866 included only these civil rights specifically enume

rated. To the contrary, Senator Trumbull said about the

bill: “ Then, sir, I take it that any statute which is not

equal to all, and which deprives any citizen of civil rights

which are secured to other citizens, is an unjust encroach

ment upon his liberty; and is, in fact, a badge of servitude

which, by the Constitution, is prohibited.” 3 4

Appellees in No. 4 (Br. 92) seek to limit the scope of the

Civil Rights Act of 1866 (both the bill as introduced and the

bill as amended). Then they argue that the scope of the

Fourteenth was limited by the alleged scope of the Civil

Rights Act. They are wrong on both points. As to the

Civil Rights Bill they ignore the following:

The comments of Senator Johnson as to the effect of the

bill on miscegenation: 5

“ . . . What is to be its application? There is not

a State in which these Negroes are to be found where

slavery existed until recently, and I am not sure that

there is not the same legislation in some of the States

where slavery has long since been abolished, which

does not make it criminal for a black man to marry a

white woman, or for a white man to marry a black

woman; and they do it not for the purpose of denying

any right to the black man or to the white man, but

for the purpose of preserving the harmony and peace

3 Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 541 (1866) .

4 Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 474 (1866).

B Id. at 505.

27

of society . . . Do you not repeal all that legislation

by this bill? . . . Is it not clear that all such legisla

tion will be repealed?”

* * *

[Johnson then illustrates this conflict in the anti

miscegenation law of Maryland and the Federal law

and how the state is denied its rights.]

“ . . . White and black are considered together,

put in a mass, and the one is entitled to enter into

every contract that the other is entitled to enter into. ’ ’

The comments of Senator Davis with respect to the

criminal codes: * 7 8

“ . . . Here the honorable Senator in one short

bill breaks down all the domestic systems of law that

prevail in all the States. . . . To the extent that a

negro is by them subjected to a severer punishment

than a white man, this short bill repeals all the penal

laws of the States. . . . ”

Senator Hendricks of Indiana on the effects of the bill

on the entrance of free Negroes:T

“ . . .In the State of Indiana we do not recognize

the civil equality of the races. . . . The policy of the

State was to prevent the further immigration of

colored people into the State after 1852, and as a

means of preventing that we denied to colored people

who might come into the State after that date the

right to acquire real estate. . . . Is this law to have

the force of vesting in the colored people who came

into that State since 1852 a good sufficient title to

land when the constitution and the law of the State

denied that right?”

Senator Morrill’s comment on the revolutionary char

acter of the Civil Rights B ill: 8

8 Id. at 598.

7 Id. at 602.

8 Id. at 570, 571.

28

“ • • • this amendment to which I address myself

is important in another respect. It marks an epoch

in the history of this country, and from this time

forward the legislation takes a fresh and a new de

parture. . . . I hail it, therefore, as a declaration

which typifies a grand fundamental change in the

politics of the country, and which change justifies the

declaration now.

• • That the measure [S. 61] is not ordinary

is most clear. There is no parallel . . . for it in the

history of this country; there is no parallel for it in

the history of any country. No nation from the foun

dation of government has ever undertaken to make

a legislative declaration so broad. Why? Because

no nation hitherto has ever cherished a liberty so

universal. The ancient republics were all exceptional

in their liberty; they all had excepted classes, sub

jected classes, which were not the subject of govern

ment ; and therefore they could not so legislate. That

it is extraordinary and without a parallel in the his

tory of this Government or of any other does not

affect the character of the declaration itself.

“ The Senator from Kentucky tells us that the

proposition is revolutionary, and he thinks that is an

objection. I freely concede that it is revolutionary. I

admit that this species of legislation is absolutely rev

olutionary. But are we not in the midst of revolution?

Is the Senator from Kentucky utterly oblivious to the

grand results of four years of war? Are we not in the

midst of a civil and political revolution which has

changed the fundamental principles of our Govern

ment in -some respects?

# # *

“ . . . I deny that [our] Government was organ

ized in the interest of any race or color, and there is

neither ‘ race’ nor ‘ color’ in our history politically or

civilly. Is there any ‘ color’ or ‘ race’ in the Declara

tion of Independence, allow me to ask? ‘ All men are

created equal’ excludes the idea of race or color or

caste. There never was in the history of this country

29

any other distinction than that of condition, and it

was all founded on condition. ”

# # *

The sweeping character of the bill was made eminently

clear by Senator Trumbull when he stated: “ . . . The very

object of the bill is to break down all discrimination between

black men and white men. . . . ” 9

Senator Cowan, in commenting upon the earlier remarks

by Senator Hendricks of Indiana, said: 10

# * #

“ But this is not a bill simply for the abolition of

slave codes. This is a bill for the abolition of all laws

in the States which create distinctions between black

men and white ones.

* # #

“ This is a proposition to repeal by act of Con

gress all State laws, all State legislation, which in

any way create distinctions between black men and

white man insofar as their civil rights and immu

nities extend. It is not to repeal legislation in regard

to slaves. . . . I hold—educated in the school in

which I have been educated, and it was not that of

the strictest constructionists, nor was it in that lati-

tudinarian school which can extract anything from

. . . the Constitution, but it was in the fair construc

tion school. . . . This bill pretends to repeal those

laws, to set them, at naught; and it pretends more

over to go further, and to make the State officers who

attempt to execute those laws criminals. . . . ”

* # *

Senator Trumbull again rose to speak upon the bill and

made it plain that its object was to repeal all state legisla

9 Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 599 (1866).

10 Id. at 603.

30

tion which created any distinction between black men and

white men as to their civil rights and immunities,11

, . [The Senator from Kentucky] says that

when slavery was abolished the slave codes in con

nection with it were abolished, and that he will advise

the people of Kentucky to extend the same civil rights

to the black population that the white population

have. He believes that they are entitled to them.

Now, sir, that is all that is provided for by the first

section of this bill. . . .

“ Then what is our duty? Agreeing as I do with

him that all slave codes fall with slavery, that it is the

duty of the States to wipe out all those laws which

discriminate against persons who have been slaves,

yet if they will not do it, and Congress has authority

to do it under the constitutional amendment, is it not

incumbent on us to carry out that provision of the

Constitution? That is all we propose to do.

“ . . . There is a positive duty upon us to pass

such a law if we find discriminations still adhered to

in the States where slavery has recently existed.”

# # #

Indeed, it is important to remember that if the purpose

of the Civil Eights Act was, as Trumbull indicated, to

destroy the Black Codes, then it follows necessarily that this

Act included more than those rights expressly enumerated.

Appellees in No. 4 cannot gain any support from Sena

tor Wilson’s statement, as to the scope of the bill on the

basis of the fact that he was speaking as Chairman of the

Judiciary Committee and the floor leader (Br. 92, 93).

The bill was recommitted against Wilson’s wishes.12

It was amended because, as Wilson said, the original

version had been taken by some as warranting “ a latitudi-

11 Id. at 605.

12 Id. at 1296.

31

narian construction not intended” (Congressional Globe,

39th Cong., 1st Session, p. 1366).

Appellees in No. 2 (Br. 13) attack the statement in

our brief-in-chief that the Civil Rights Act as originally

drafted was so broad in scope that it was believed to have

the effect of destroying entirely all state legislation which

distinguished or classified on account of race, including

school segregation laws. But Senator Garrett Davis,

speaking at the time of the Johnson veto, made the follow

ing statement: 13

“ In many if not most of the States, there are

discriminations in relation to some of those impor

tant concerns against the negro race, made by their

constitutions and statutes; and this act abrogates

not only those constitutions and laws to that extent,

but makes their execution by the State officers ap

pointed for that purpose, a high misdemeanor, and

punishes them heavily by fine and imprisonment.”

# * #

“ But this measure proscribes all discrimination

against negroes in favor of white persons that may

be made anywdiere in the United States by any

‘ ordinance, regulation or custom,’ as well as by ‘ law

or statute ’. . . .

“ But there are civil rights, immunities, and privi

leges ‘which ordinances, regulations, and customs’

confer upon white persons everywhere in the United

States, and withhold from negroes [on ships, steam

boats, in hotels, churches, railroads, streetcars.]___

All these discriminations in the entire society of the

United States are established by ordinances, regula

tion and customs. This bill proposes to break down

and sweep them all away, and to consummate their

destruction, and bring the two races upon the same

great plane of equality. . . . ”

13 Id., App. 182, 183.

32

Attention is also directed to Senator Davis’ further

remarks on March 15, 1866, on the completed bill: 14

“ . . . W e have laws in the State of Kentucky that

discriminate between the punishment of the whites

and blacks. Those laws we expect to continue in

operation, and we expect to execute them in the

future. What power has Congress to pass a law to

harmonize the criminal and penal law of the State of

Kentucky, and command and coerce that the same pun

ishments which are inflicted upon her white citizens,

and none other, shall be administered to her negro

population? What authority has Congress to com

mand the government and the people of Kentucky,

or any State to confer on the negro portion of its

population the same civil rights with which the laws

invest white citizens? . . . It [this bill] assumes the

principle, the general power that would as well

enable Congress to occupy both of those vast fields

of State and domestic legislation which regulate the

civil rights, and the pains, penalties, and punish

ments inflicted upon the people of the respective

States which were not delegated to the Government

of the United States, but were reserved to the States

respectively and to the people, as to them the most

important and interesting portion of their original

sovereignty. ’ ’

Appellees in No. 4 criticize the use of a speech by Mr.

Bingham of Ohio as “ an example of the misleading charac

ter of the apparent scholarship of appellants” (Br. 99).

Our “ implication” that Bingham approved of state con

stitutions banning segregated schools is criticized as

“ erroneous” and “ the impression left” is characterized as

“ materially misleading” {Ibid.).

If the context of Mr. Bingham’s speech is examined, the

original statement objected to by appellees will be found

to be amply supported by the debates in Congress. On

14 Id. at 1415.

33

May 13,1868, Mr. Beck of Kentucky, speaking against H. K.

1058, a bill to readmit five southern states, objected to the

new Constitution of South Carolina in particular which

provided, he said “ that the white race shall never have

any public school exclusively for themselves. . . .” 15 The

following day, Mr. Pruyor of New York reminded the

House of Beck’s speech regarding “ several most objection

able provisions [in the new state constitutions], especially

as to the compulsory education of whites and blacks to

gether.” 16 Mr. Bingham, speaking after him, defended

the same state constitutions in a ringing declaration that

they: 17

“ . . . in accordance with the spirit and letter of the

Constitution of the United States as it stands

amended . . . secure equal political and civil rights

and equal privileg*es to all citizens of the United

States. . . . Time was in this Republic when that was

Democracy. ’ ’

Appellees in No. 4 refer to Bingham’s answer to Hale’s

opposition to the proposed Amendment as an “ elaborate

speech . . . but no great meaning can be derived from it. ’ ’

And refer to Bingham’s reply to Hale as a modification

of his original answer (Br. 101). No such implication

is warranted, as can be seen from the colloquy referred to

below: 18

Bingham

“ . . . They [the Southern people] will, I trust,

though it may not be without additional sacrifice,

correct all errors, perfect their Constitutions enforce

by just and equal laws all its provisions, and so

fortify and strengthen the Republic that it will stand

unmoved until empires and nations perish. . . . ”

# # #

15 Cong. Globe, 40th Cong., 2d Sess. 2447 (1868).

16 Id. at 2461.

17 Id. at 2462.

18 Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 1094 et seq.

34

“ I urge the amendment for the enforcement of

these essential provisions of your Constitution,

divine in their justice, sublime in their humanity,

which declare that all men are equal in the rights

of life and liberty before the Majesty of American

law. . . . Your Constitution provides that no man, no

matter what his color, no matter beneath what sky he

may have been born, no matter in what disastrous

conflict or by what tyrannical hand in his liberty may

have been cloven down, no matter how poor, no mat

ter how friendless, no matter how ignorant shall be

deprived of life or liberty or property without due

process of law—law in the highest sense, that law

which is the perfection of human reason, and which

is impartial, equal, exact justice; that justice which

requires that every man shall have his right. . . . ”

Hale

“ • • . My question was whether this provision, if

adopted, confers upon Congress general powers of

legislation in regard to the protection of life, liberty

and personal property.”

Bingham

“ It certainly does this; it confers upon Congress

power to see to it that the protection given by the

laws of the States shall be equal in respect to life

and liberty and property to all persons.”

Hotchkiss

“ . . . As I understand it, his [Bingham’s] object

in offering this resolution and proposing that this

amendment is to provide that no State shall dis

criminate between its citizens and give a class of

citizens greater rights than it confers upon another.

If this amendment secured that, I should vote very

cheerfully for it today; but as I do not regard it as

permanently securing those rights, I shall vote to

postpone its consideration until there can be a fur

ther conference between the friends of the measure,

and we can devise some means wdiereby we shall

secure those rights beyond a question. . . . ”

# # #

35

“ Now, if the gentleman’s object is, as I have

no doubt it is, to provide against discrimination to

the injury or exclusion of any class of citizens in any

State from the privileges which other classes enjoy,

the right should be incorporated into the Constitu

tion. It should be a constitutional right that cannot

be wrested from any class of citizens or from the

citizens of any State by mere legislation. But this

amendment offers to leave it to the caprice of Con

gress. . . . I want them [the privileges] secured by a

constitutional amendment that legislatures cannot

override. Then if the gentleman wishes to go fur

ther, and provide by laws of Congress for the en

forcement of these rights, I will go with him. . . . ”

* .y. -y-

“ His amendment is not as strong as the Consti

tution nowT is. . . . The Constitution now gives equal

rights to a certain extent to all citizens. This amend

ment provides that Congress may pass laws to

enforce these rights. Why not provide by an amend

ment to the Constitution that no State shall discrimi

nate against any class of its citizens, and let that

amendment stand as an organic law of the land,

subject only to be defeated by another constitutional

amendment. We may pass laws here today, and the

next Congress may wipe them out. What is your

guarantee then?”