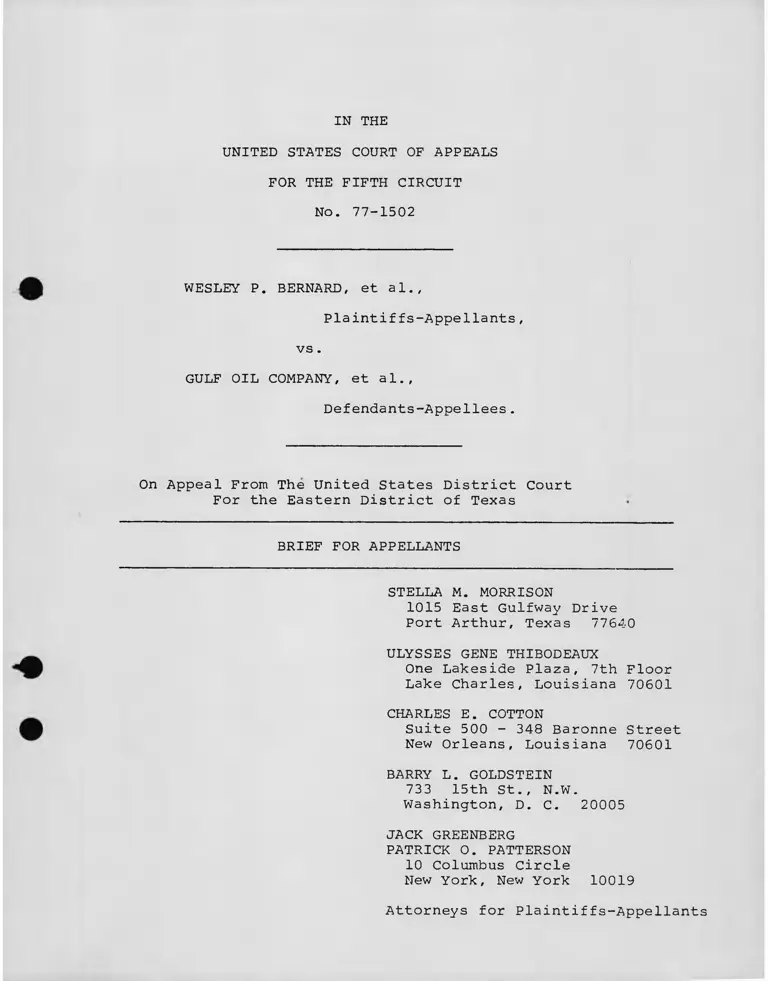

Bernard v. Gulf Oil Company Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

July 12, 1977

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bernard v. Gulf Oil Company Brief for Appellants, 1977. 49b20ec2-c69a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1c95be49-3997-4af7-aded-c5d9f21ac997/bernard-v-gulf-oil-company-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 77-1502

WESLEY P. BERNARD, et al.#

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

vs.

GULF OIL COMPANY, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For the Eastern District of Texas

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

STELLA M. MORRISON

1015 East Gulfway Drive

Port Arthur, Texas 77640

ULYSSES GENE THIBODEAUX

One Lakeside Plaza, 7th Floor

Lake Charles, Louisiana 70601

CHARLES E. COTTON

Suite 500 - 348 Baronne Street

New Orleans, Louisiana 70601

BARRY L. GOLDSTEIN

733 15th St., N.W.

Washington, D. C. 20005

JACK GREENBERG

PATRICK O. PATTERSON

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 77-1502

WESLEY P. BERNARD,

GULF OIL COMPANY,

et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants

vs.

et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal from The United States District Court

for The Eastern District of Texas

CERTIFICATE REQUIRED BY LOCAL RULE 13(a)

The undersigned, counsel of record for the plain

tiff s-appellants, certifies that the following listed par

ties have an interest in the outcome of this case. These

representations are made in order that Judges of this Court

may evaluate possible disqualification or recusal pursuant

to Local Rule 13 (a).

1. Wesley P. Bernard, Elton Hayes, Sr., Rodney

Tizeno, Hence Brown, Jr., Willie Whitley, and Willie

i

Johnson, plaintiffs.

2. The class of all black employees now employed

or formerly employed by defendant, Gulf Oil Company, in Port

Arthur, Texas, and all black applicants for employment at

Gulf Oil Company who have been rejected for employment at

said company.

3. Gulf Oil Corporation, defendant.

4. Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers International

Union, and Local Union No. 4-23, Oil, Chemical and Atomic

Workers International Union, defendants.

5. International Association of Machinists and

Aerospace Workers, Port Arthur Lodge No. 823; international

Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers; International

Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, Local Union No. 390;

International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, AFL-CIO;

United Transportation Local Union; International United

Transportation Union; Bricklayers, Masons, and Plasterers

International Union, Local 13; and International Bricklayers,

Masons, and Plasterers Union: prospective defendants named in

plaintiffs' motion to join additional defendants and for leave

to amend the complaint. This motion was pending when the dis

trict court granted summary judgment for the existing defendants.

Attorney for Plaintiffs-Appellants

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 77-1502

WESLEY P. BERNARD, et al..

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

vs .

GULF OIL COMPANY, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Eastern District of Texas

CERTIFICATE REQUIRED BY LOCAL RULE 13 (j) (2)

Plaintiffs-appellants believe that the errors of the

court below are clear from the record and that the issues raised

on this appeal can be adequately argued and decided on the briefs

alone. Therefore, we submit that oral argument is not necessary

and that this case is appropriate for summary disposition pursuant

to Local Rule 18. However, as set forth in part IV of the argument

herein, this case raises First Amendment and other constitutional

questions of first impression in this circuit which may have a

substantial impact on the administration of class actions in the

district courts, particularly with respect to restrictions on

communications by named plaintiffs and their counsel with class

members. Although plaintiffs-appellants submit that the

tions imposed on such communications in this case are so

unconstitutional as not to require further argument, the

may wish to hear oral argument on this question.

restric-

clearly

Court

IV

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Statement of Issues .......................................... 1

Statement of the C a s e ..........................................3

Summary of Argument........................................... 11

Argument

I. The district court erred in dismissing the

plaintiffs' Title VII claims for failure

to file a civil action within ninety days

of the issuance by the EEOC of letters

advising plaintiffs of the failure of

conciliation ...................................... 15

II. The district court erred in dismissing the

plaintiffs' claims under 42 U.S.C. § 1981

as barred by the statute of limitations.........21

III. The district court erred in holding that

this action may be barred by the doctrine

of l a c h e s ...........................................28

IV. The orders of the district court restric

ting communications by plaintiffs and their

counsel with class members are unconsti

tutional and are beyond the authority of

the district c o u r t ................................. 39

Conclusion............................................ 63

Certificate of Service ...................................... 64

Supplemental Appendix ...................................... ^

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES Page

Adickes v. S.H. Kress Co., 398 U.S. 144 (1970)......... 23

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975). . 23, 27

Alexander v. Gardner Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36 (1974)20,30,43

Allen v. Amalgamated Transit Union Local 788,

____ F.2d ____ , 14 FEP Cases 1494 (8th Cir. 1977). 25,27

Anderson v. Mt. Clemens Pottery Co.,

328 U.S. 680 (1946).................................. 36

Aulds v. Foster, 484 F.2d 945 (5th Cir. 1 9 7 3 ) ......... 24

Baker v. F & F Investment, 420 F.2d 1191

(7th Cir. 1 9 7 0 ) .................................. 26, 29

Bantam Books, Inc. v. Sullivan, 372 U.S. 58 (1963) . . . 40

Bates v. Little Rock, 361 U.S. 516 (1960)............. 52

Bates v. State Bar of Arizona, 45 U.S.L.W. 4895

(U.S., June 27, 1 9 7 7 ) ........................ 42, 48, 50

Belt v. Johnson Motor Lines, Inc.,

458 F. 2d 443 (5th Cir. 1 9 7 2 ) ................... 23, 24

Beverly v. Lone Star Lead Construction Corp.,

437 F.2d 1136 (5th Cir. 1 9 7 1 ) ........................33

Boazman v. Economics Laboratory, Inc., ___ F.2d ___ ,

13 EPD 11,329 (5th Cir. 1 9 7 6 ) ..................... 37

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 (1954)................. 57

Boudreaux v. Baton Rouge Marine Contracting Co., 437

F.2d 1011 (5th Cir. 1971) . . . .................. 23, 28

Bridges v. California, 314 U.S. 252 (1941)........... 62

Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen v. Virginia ex rel.

State Bar, 377 U.S. 1 (1964)................... 47, 58

33

Choate v. Caterpillar Tractor Co., 402 F.2d 357

(7th Cir. 1968) ............................

Costello v. United States, 365 U.S. 265 (1961) . . . . 29

Cox v. Allied Chemical Corp., 538 F.2d 1094

(5th Cir. 1 9 7 6 ) .................................... 43

Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 536 (1965)............... 58

Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 559 (1965)............... 58

Cox Broadcasting Corp. v. Cohn, 420 U.S. 469 (1975) . 44

Craig v. Harney, 331 U.S. 367 (1947)............... 43, 62

Davis v. County of Los Angeles, ___ F.2d ___ , 12 EPD

5 11,219 (9th Cir. 1 9 7 6 ) ......................... 25

DeMatteis v. Eastman Kodak Co., 511 F.2d 306, modified,

520 F.2d 409 (2d Cir. 1 9 7 5 ) ..................... 17, 18

Dent v. St. Louis-San Francisco R. Co., 406 F.2d 399

(5th Cir. 1 9 6 9 ) .................................. 33

Ecology Center of Louisiana v. Coleman, 515 F.2d 860

(5th Cir. 1 9 7 5 ) .................................. 29

EEOC v. Airguide Corp., 539 F.2d 1038 (5th Cir. 1976) 37,38

EEOC v. Cleveland Mills Co., 502 F.2d 153 (4th Cir.

1974), cert, denied, 420 U.S. 946 (1975)......... 32

EEOC v. Griffin Wheel Co., 511 F.2d 456 (5th Cir. 1975) 25

EEOC v. Louisville & Nashville R.R. Co., 505 F.2d 610

(5th Cir. 1974), cert. denied, 423 U.S. 824 (1975) 32

Evans v. Dow Chemical Co., 13 FEP Cases 1461

(D. Colo. 1975) .......................... 38

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 495 F.2d 398

(5th Cir.), cert, denied in pertinent part, 419

U.S. 1050 (1974)........................ 28, 33, 36, 37

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424

U.S. 747 (1976)..................................... 49

Garner v. E.I. DuPont de Nemours and Co., 538 F.2d

611 (4th Cir. 1 9 7 6 ) ................................ 16

Gibson v. Florida Legislative Investigative Committee,

372 U.S. 539 (1963)................................ 53

Gideon v. Wainwright. 372 U.S 335 (1963)............. 58

Gray v. Greyhound Lines, East, 545 F.2d 169

(D.C. Cir. 1 9 7 6 ) .................................. 23

Guerra v. Manchester Terminal Corp., 498 F.2d 641

(1974)............................................. 37

Halverson v. Convenient Food Mart, Inc., 458 F.2d 927

(7th Cir. 1972) .................................. 42

Hanover

U.S

Shoe, Inc. v

. 481 (1968)

. United Shoe Machinery Corp 392

. 25,36

Harper v.

Supp.

1134

Mayor and City Council of Baltimore, 359 F.

1187 (D. Md.), modified and aff’d, 486 F.2d

(4th Cir. 1973) ............................

Hines v. Olinkraft, Inc., 413 F. Supp. 1360 (W.D. La.

1976) .

36

23

Holmberg v. Armbrecht, 327 U.S. 392 (1946) . . . .

Huff v. N.D. Cass Co., 485 F.2d 710 (5th Cir. 1973)

(en banc) .......................................

Jenkins v. McKeithen, 395 U.S. 411 (1969) .........

v m

49, 59

Jenkins v. United Gas Corp., 400 F.2d 28

(5th Cir. 1 9 6 8 ) .............................. . 49, 59

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, Inc. , 488

F .2d 714 (5th Cir. 1974) ................... . 49

Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 491 F.2d

1364 (5th Cir. 1974) ........................ . 23

Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, Inc., 421

U.S. 454 (1975) .............................. . 21, 23,

26, 27

Johnson v. Robison, 415 U.S- 361 (1974) ......... . 57

Kohn v. Royall, Koegel & Wells, 59 F.R D.

515 (S.D.N.Y. 1973), appeal dismissed, 496

F . 2d 1094 (2d Cir. 1974)..................... . 34

Lacy v. Chrysler Corp., 533 F.2d 353 (8th Cir)

(en banc), cert, denied. U.S. 12 EPD

5 11,234 (1976) .............................. . 17, 18

Lea v. Cone Mills, 438 F.2d 86 (4th Cir. 1971) . . . 49

Macklin v. Spector Freight Systems, Inc., 478

F .2d 979 (D.C. Cir 1973) ................... . 26

Marlowe v. Fisher Body, 489 F.2d 1057

(6th Cir. 1 9 7 3 ) .............................. . 26

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U S.

792 (1973) .................................. . 20

McGuire v. Aluminum Company of America, 542 F.2d

43 (7th Cir. 1976) .......................... . 17

Miller v. Amusement Enterprises, Inc.. 426

F.2d 534 (5th Cir. 1970) ................... . 47

NAACP v. Alabama ex rel. Patterson, 357

U.S. 449 (1958) .............................. . 52, 59

NAACP v. Button, 371 U S. 415 (1963) ............. . 7, 14

42, 45-48,

50-53, 55

- IX -

Near v. Minnesota, 283 U.S. 697 (1931) 40

Nebraska Press Association v. Stuart, 427

U.S. 539 (1976).................................. 43, 44

51

New York Times Co. v. United States, 403 U.S.

713 (1971) 40

Newman v. Piggie Park Entreprises, Inc., 390

U.S. 400 (1968).................................. 48, 49,

59

Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 U.S. 268 (1951) ........... 57

Oatis v. Crown Zellerbach Corp., 398 F.29 496

(5th Cir. 1 9 6 8 ) ................................... 20

Occidental Life Insurance Co. v. EEOC, 45 U.S.L.W.

4752 (U.S., June 20, 1977) ..................... 27. 30,

31, 32,

37

Oklahoma Publishing Co. v. District Court

51 L.Ed. 2d 355 ( 1 9 7 7 ) .......................... 44

Organization for a Better Austin v. Keefe,

402 U.S. 415 (1971).............................. 40

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 411

F . 2d 998 (5th Cir. 1969) 53

Rodgers v. United States Steel Corp., 508 F.2d

152 (3rd Cir.), cert denied, 420 U.S. 969

(1975) 61, 62,

63

Rodgers v. United States Steel Corp., 536 F.2d

1001 (3rd Cir. 1976) 40. 44,

45, 62

Shelton v. Tucker. 364 U.S. 479 (1960)............... 53

x -

512 F .2dSkipper v. Superior Dairies, Inc., 512 F.2d

409 (5th Cir. 1975) .......................... . 36

Southeastern Promotions, Ltd. v. Conrad, 420

U.S. 546 (1975) ..............................

Sperry v. Barggren, 523 F.2d 708 (7th Cir. 1975) . . 24

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U.S 88 (1940) ......... . 57

Tuft v. McDonnell Douglas Corp.. 517 F.2d 1301

(8th Cir. 1975), cert denied, 423 U.S.

U.S. 1052 ( 1 9 7 6 ) ............... ............

United Air Lines, Inc. v. Evans, 45 U.S.L.W.

4566 (U.S.- May 31, 1977) ................... . 26

United Mine Workers v. Illinois State Bar

Association, 389 U.S. 217 (1967) ........... . 47

United States v. Allegheny-Ludlum Industries,

Inc., 517 F .2d 826 (5th Cir. 1975),

cert, denied, 425 U.S. 944 (1976) ...........

United States v. Georgia Power Co., 474 F.2d

906 (5th Cir. 1973) .......................... . 25

United States Steel Corp. v. Darby, 516 F.2d

961 (5th Cir. 1975) .......................... . 37

United Transportation Union v. State Bar of

Michigan, 401 U.S. 576 (1971) ............... COr-

Virginia Pharmacy Board v. Virginia Consumer

Council, 425 U S. 748 (1976) ............... . 48

Watkins v. Scott Paper Co., 530 F.2d 1159

(5th Cir. 1976) .............................. . 43

Weaver v. Joseph Schlitz Brewing Co.. F.2d

, 13 EPD f 11,589 (6th Cir. 1977) . . . . . 16

Wheat v. Hall, 535 F.2d 874 (5th Cir. 1976) . . . . 29

Williams v. Norfolk & Western Ry. Co-, 530

F .2d 539 (4th Cir. 1975) ........... 25

Williams v. Southern Union Gas Co., 529 F.2d

483 (10th Cir.), cert, denied, ___U.S.

___, 12 EPD 5 11-234 (1976)................... 17

Williamson v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., 468 F.2d

1201 (2d Cir. 1972), cert denied, 411 U.S. 931. 43

Wood v. Georgia, 370 U.S. 375 (1962)............... 43

Zambuto v. American Telephone & Telegraph Co.,

544 F. 2d 1333 (5th Cir. 1 9 7 7 ) ................. 12, 18,

19, 32, 33

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS, STATUTES,

RULES AND REGULATIONS

United States Constitution, First Amendment . . . . passim

United States Constitution, Fifth Amendment . . . . passim

28 U.S.C. § 2071 ........ ............................ 14. 60

42 U.S.C. § 1981, Civil Rights Act of 1866 ........ passim

42 U.S.C. § 1988, Civil Rights Attorneys' Fees

Awards Act of 1976 ............................ 42, 49

42 U.S.C. § 2000e et seq,, Title VII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, as amended by the Equal

Employment Opportunity Act of 1972 ........... passim

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-3 (a) , § 704(a) of Title VII . . . 53

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5 (b) , § 706 (b) of Title VII . . . 53

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(f), § 706(f) of Title VII . . . 15, 16,

18, 19

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(k), § 706 (k) of Title VII . . . 42, 49

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-8(c), § 709(c) of Title VII . . . 34, 35

Rule 23. Fed. R. Civ. P ............................. 14, 20

59, 61

Rule 56, Fed. R. Civ. P ............................... 37

Rule 83, Fed. R. Civ. P ............................... 14, 60

Local Rule 34(d), Western District of Pa...........61

EEOC Regulations, 29 C.F.R. § 1602, 14(a)

(1967) and 31 Fed. Reg. 2833 (Feb. 17. 1966) . 35

Tex. Rev. Civ. Stat. Ann. art. 5526 ( 4 ) ........... 23

OTHER AUTHORITIES

ABA Committee on Professional Ethics. Opinions,

No. 148 (1935)................................ 48

118 Cong. Rec. 7168, 7565 (1972) ................. 31-32

Legislative History of the Equal Employment

Opportunity Act of 1972 (H.R. 1746, Pub. L.

No. 92-261) 53

Manual for Complex Litigation, 1 J. Moore,

Federal Practice (2d Ed. 1 9 7 6 ) ............... 61, 62

S. Rep. No. 415, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. (1971) . . . 31

S. Rep. No. 1011, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. (1976),

reprinted in 1976 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News

6338-44 49

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 77-1502

WESLEY P. BERNARD, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

vs .

GULF OIL COMPANY, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For the Eastern District of Texas

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

STATEMENT OF ISSUES

1. Did the district court err in dismissing the

plaintiffs 1 claims under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964, as amended, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e et seq., for failure

to file a civil action within ninety days of the issuance

by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission of letters

advising plaintiffs of the failure of conciliation efforts?

2. Did the district court err in dismissing as

barred by the statute of limitations the plaintiffs' claims

under 42 U.S.C. § 1981 of present and continuing discriminatory

employment practices?

3. Did the district court err in concluding that

this action was barred by laches?

4. Are the district court's orders restricting

communications by plaintiffs and their counsel with class

members violative of the First and Fifth Amendments and

beyond the authority of the court?

2

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The plaintiffs-appellants in this case are six black

present or retired employees of the defendant Gulf Oil

_1/Company (hereinafter "Gulf" or "the company") who charge

that they and all other similarly situated black persons

are the victims of systematic past, present, and continuing

racial discrimination in employment by the company and the

_2/

union defendants, in violation of the Civil Rights Act of

1866, 42 U.S.C. § 1981, and Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, as amended, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e et seq. Juris

diction in the district court was predicated on 28 U.S.C.

§ 1343 (4) and 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5 (f) . Plaintiffs appeal

from orders of the district court restricting or prohibiting

communications by plaintiffs and their counsel with class

members and granting summary judgment for the defendants.

This court has jurisdiction of the appeal pursuant to

28 U.S.C. § 1291.

1/ The named plaintiffs are Wesley P. Bernard, Elton

Hayes, Sr., Rodney Tizeno, Hence Brown, Jr., Willie Whitley,

and Willie Johnson. In a motion which was filed on November

24, 1976, Mr. Brown requested that he be dropped as a party

plaintiff (R. 344). This motion was never decided by the

District Court, and it is not otherwise pertinent to this

appeal.

2/ The Union defendants are the Oil, Chemical and Atomic

Workers International Union and Local Union No. 4-23 (hereinafter

"international union" and "local union" respectively).

3

The complaint in this action was filed in the

district court on May 18, 1976 (A. 4), and it was amended

on July 19, 1976 (A. 66). Plaintiffs brought the action

on their own behalf and, pursuant to Rule 23(b)(2) of the

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, on behalf of all black

present and former employees of the company at its refinery

at Port Arthur, Texas, and on behalf of all black applicants

who have been rejected for employment at the company (A. 5, 67).

Plaintiffs allege that black employees of the company "are,

and have in the past, been victims of systematic racial dis

crimination by defendants . . and that "prior and sub

sequent to July 2, 1965, Gulf Oil engaged in policies, prac

tices, customs and usages . . .which discriminate or have the

effect of discriminating against plaintiffs and the classes

they represent because of their race and color" (A. 70).

The methods of discrimination are alleged to include present

and continuing discriminatory practices in hiring, job assign

ment, testing and selection, wages, working conditions, exclusion

of blacks from higher-paying craft positions, promotion and up

grading practices, training opportunities, and discriplinary and

discharge practices (A. 70-72). The union defendants are alleged

to have agreed to, acquiesced in, or otherwise condoned these

discriminatory practices (A. 72-73). Plaintiffs seek, inter

alia, a declaratory judgment, a make-whole remedy including

4

back pay for past discrimination, and a broad range of prospec

tive injunctive relief from present and continuing discrimina

tory practices (A. 74-76)-

Three of the named plaintiffs — Bernard, Brown,

and Johnson — filed charges of discrimination with the

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) in 1967 against

the company and the local union (A. 92, 96, 100). Plaintiff

Bernard filed an amended charge with the EEOC in 1976 against,

inter alia, the international union (R.361-366, Supp. App. 21A).

Plaintiff Whitley filed a charge with the EEOC in 1972 against

the company (A. 110). Plaintiffs Hayes and Tizeno have not

filed any charges of discrimination with the EEOC.

On August 15, 1968, the EEOC issued a decision

finding reasonable cause to believe that the charges of

discrimination filed by plaintiffs Bernard, Brown, and Johnson

were true (A. 94, 98, 102). On December 4, 1973, the EEOC

issued a determination finding no reasonable cause with

respect to the charge filed by plaintiff Whitley, together

_3/with a "Notice of Right To Sue" (A. 104-115).

On February 26, 1975, plaintiffs Bernard, Brown,

and Johnson each received a letter from the EEOC stating

that the respondents named in their charges of discrimination

[did] not wish to entertain conciliation

discussions ... [and that] you are hereby

3/ The final order of the district court states that "Plaintiff

Willie Whitley's failure of conciliation letter was sent December

4, 1973" (A. 182). The record contains no support for a finding

that any letter regarding the failure of conciliation was ever

sent to plaintiff Whitley or that any such conciliation efforts

were ever undertaken.

5

notified that you may request a "Notice

of Right to Sue" from this office at any

time. If you so request, the notice will

be issued, and you will have ninety (90)

days from the date of its receipt to file

suit in Federal District Court. (A. 84, 87,

90) .

However, on the basis of a separate charge of

discrimination which had been filed against the company by

a commissioner of the EEOC in 1968, the company engaged in

conciliation discussions with the EEOC and with the Office

for Equal Opportunity of the United States Department of

the Interior (DOI), resulting in a conciliation agreement

which was entered into between the company and the EEOC on

April 14, 1976, and which was approved by the DOI on the

same date (A. 15-28). This agreement was not subject to

judicial review or approval, and neither the union defend

ants in this case nor the named plaintiffs or any members of

their class were parties to the agreement (A. 26-28).

Approximately two weeks after the agreement was

signed (A. 36), the company began tendering "back pay

awards" under the agreement to certain black and female

employees and former employees identified as "affected

class members" (A. 18-20), and soliciting releases or

waivers from such persons purporting to release the company

"for any and all claims against [it] as a result of events

arising from its employment practices occurring on or before

the date of release, or which might arise as the result of

the future effects of past or present employment practices"

(A. 20, 35-36). Failure to respond within thirty days to

6

notice of the tender and the release or waiver was deemed

an acceptance of back pay under the terms of the agreement

(A. 20, 36). The tendering of awards and solicitation of

waivers or releases continued until the commencement of this

action on May 18, 1976, after which the company temporarily

suspended these activities (A. 29, 36).

On May 22, 1976, four days after the complaint

was filed, the named plaintiffs held a meeting in Port

Arthur, Texas, which was attended by members of the class

defined in the complaint. Attorneys for the named plaintiffs

were invited to attend the meeting to discuss the lawsuit and

to answer questions concerning the lawsuit and the conciliation

agreement (A. 51, 53-54). Affidavits of counsel show that the

attorneys for plaintiffs are associated with the NAACP Legal

Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., which is a nonprofit

corporation engaged in furnishing legal assistance in cases

involving claims of racial discrimination (A. 46,50). Legal

Defense Fund attorneys have represented persons in hundreds

of civil rights cases in this circuit and in its district

courts, and in many landmark Title VII cases which have been

decided in the Supreme Court, the Fifth Circuit, and other federal

courts (a . 47-48). The organization has been recognized by

the Supreme Court as having "a corporate reputation for ex

pertness in presenting and arguing the difficult questions

of law that frequently arise in civil rights litigation."

NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415, 422 (1963). None of the

7

attorneys for the plaintiffs has accepted or expects to

receive any compensation from the named plaintiffs, from

any additional named plaintiffs who may be joined in the

future, or from any members of the class (A. 48, 54). Any

counsel fees which they might obtain would result from an

award by the court which, pursuant to statutory authorization,

would be taxed as costs to the defendants (A. 48, 54). Any

such award to staff attorneys of the Legal Defense Fund

would be paid over to the Legal Defense Fund and would not

be paid directly to any such attorneys (A. 48).

Five days after the meeting of May 22, 1976, the

company filed a motion to prohibit the parties and their

counsel from communicating concerning the action with any

potential or actual class member who was not a formal party

to the action without the prior consent and approval of the

district court (A. 14). On the following day, May 28, 1976,

District Judge Steger, ruling in Chief Judge Fisher's absence,

entered an order forbidding without exception all such communi

cations with any potential or actual class member not a formal

party to the action, pending Judge Fisher's return (A. 30-31).

The order of May 28 remained in effect until

June 22, 1976, when Judge Fisher granted the company's

motion to modify the order so as to permit the resumption

of the tenders of "back pay" and the solicitation of releases

(A. 32-39, 56-61). The modified order also provided that it

did not forbid certain communications initiated by a client

8

or prospective client and certain communications occurring

in the regular course of business, and it required that any

constitutionally protected communication be filed with the

court within five days after its occurrence (A. 57). The

modified order otherwise repeated the prohibitions of the

original order (A. 56-57).

On July 6, 1976, the plaintiffs moved for per

mission for themselves and their counsel to communicate with

members of the proposed class, and for an order declaring that

a notice which they proposed to distribute was within their

constitutionally protected rights (A. 62-65). The motion

of the plaintiffs was denied (A. 157).

On June 11, 1976, the EEOC issued to plaintiffs

Bernard and Brown the "Notices of Right To Sue Within 90

Days"(A. 73) which had been mentioned in the letters which

they had received from the EEOC on Febraury 26, 1975 (A. 84,

_4/

87, 90). These notices stated as follows:

Pursuant to Section 706(f) of Title VII

. . ., you are hereby notified that you may,

within ninety (90) days of receipt of this

communication, institute a civil action in the

appropriate Federal District Court.

The plaintiffs then filed a motion to amend their

complaint, which was granted on July 19, 1976 (A. 66-76).

The unions, which had answered the original complaint on

June 10, 1976 (A. 40-43), filed an answer to the amended

4/ The amended complaint states that these notices were attached

thereto as Exhibits A and B (A. 73). However, they do not appear

in the record as transmitted by the District Court. These notices

nevertheless were referred to by the parties and the court below

(e.g., A. 183), and copies are provided in an appendix to this

brief (Supp. App. 1A-2A) . o

complaint on July 30, 1976 (A. 153-156). The company, which

had moved to dismiss the original complaint on June 17, 1976

(A. 44-45), filed a motion to dismiss the amended complaint

on July 28, 1976 (A. 77-78). The unions joined in this motion

on August 25, 1976 (A. 158). The motion sought dismissal on

the grounds, inter alia, that the jurisdictional prerequisites

for maintaining the action under Title VII had not been satisfied,

that the action was barred by the statute of limitations and

by laches, and that no proper class representatives had been named

(A. 77-78). In support of its motion, the company filed affi

davits of EEOC employees regarding administrative records and

files (A. 79-152), and an affidavit of C. B. Draper, an employee

of the company, stating inter alia that from July 1965 to April

1975 personnel changes had occurred and the company had destroyed

numerous records and documents pertinent to this case (A. 174-179).

On November 29, 1976, the district court ordered sua sponte

that the motion to dismiss the amended complaint be treated as

a motion for summary judgment (A. 180). On January 11, 1977,

the court granted summary judgment for the defendants (A. 181-185),

holding that plaintiffs Hayes and Tizeno had not filed charges

of discrimination with the EEOC and therefore could not maintain

suit in their own right or adequately represent a class (A. 182);

that the ninety day period for plaintiffs Bernard, Brown, and

Johnson to file a civil action under Title VII had begun on

February 25, 1975, the date on which the EEOC had sent them

letters advising that the respondents did not wish to entertain

10

conciliation discussions, rather than the date on which

plaintiffs Bernard and Brown received their June 11, 1976,

EEOC "Notices of Right to Sue Within 90 Days," and that the

Title VII claims were therefore time-barred (A. 182-184);

that the EEOC had sent plaintiff Whitley a "failure of con

ciliation letter" on December 4, 1973, which started the

running of his ninety day period to file a civil action,

and that his Title VII claim was therefore time-barred (A. 182)

that plaintiffs' claims under 42 U.S.C. § 1981 were "the

subject of complaints filed with the EEOC in 1967 by three

of the plaintiffs," that the pattern of discrimination alleged

therein "has long since been eliminated," and that all of the

plaintiffs' claims under § 1981 were therefore barred by the

applicable Texas statute of limitations (A. 184); and that

the company had presented "a most compelling argument for the

application of the equitable doctrine of laches" (A. 184).

Plaintiffs subsequently filed a timely notice of appeal

(R. 392, Supp. App. 27A).

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The amended complaint in this action was filed

within ninety days of the receipt by plaintiffs Bernard and

Brown of EEOC "Notices of Right to Sue Within 90 days," but

not within ninety days of the issuance of EEOC letters stating

11

that the defendants did not wish to entertain conciliation

discussions regarding plaintiffs' charges of discrimination.

Although this court has held a similar EEOC two-letter pro

cedure to be improper under Title VII, the court explicitly

made its ruling prospective and therefore inapplicable to the

instant case. Zambuto v. American Telephone and Telegraph Co.,

544 F.2d 1333 (5th Cir. 1977). Moreover, even if the Zambuto

decision were applicable to this case, the opinion indicates

that the Fifth Circuit has joined other circuits in holding

(1) that the ninety day suit period does not commence until

a charging party receives notice that the EEOC has terminated

all administrative procedures, and (2) that a letter stating

only that conciliation has failed does not satisfy this require

ment. Therefore, the district court erred in dismissing the

plaintiffs 1 Title VII claims on this ground.

Since plaintiffs Bernard and Brown satisfied the

jurisdictional prerequisites to the institution of an action

under Title VII, plaintiffs Hayes, Tizeno, Johnson, and Whitley

were also properly named as plaintiffs and class representatives.

Even if none of the named plaintiffs had satisfied the Title VII

prerequisites, the district court would be in error for refusing

for this reason to permit them to maintain the action under

42 U.S.C. § 1981, which provides remedies which are independent

of those provided by Title VII.

12

Plaintiffs have alleged that the defendants are

engaging in numerous present and continuing discriminatory

employment practices in violation of Title VII and 42 U.S.C.

§ 1981. Such claims of present and ongoing discrimination

are barred neither by the statute of limitations nor by the

doctrine of laches, and the court below erred in dismissing

the action on these grounds. The district court also erred

in holding that the filing of EEOC charges by three of the

named plaintiffs in 1967 operated to deprive all of the

plaintiffs of the right to seek redress for present violations

of § 1981.

The district court further erred to the extent

that it dismissed the action on the basis of laches. The

party asserting the defense of laches must prove that there

has been inexcusable delay and resulting prejudice. Neither

element has been established here. Plaintiffs did not in

excusably delay the filing of this action; instead, they

justifiably relied on the EEOC to perform its administrative

functions in accordance with the intent of Congress, and

they promptly filed suit when they found the resulting EEOC

conciliation agreement unsatisfactory. In view of the in

contestable fact that the company has been on notice since at

least 1967 that charges of discrimination were pending against

it, there has been no showing that the company's failure to

preserve the testimony of witnesses, or its destruction of

documents and records in violation of Title VII and EEOC

13

regulations, constitutes prejudice resulting from any delay.

Rather, the loss of any such evidence is attributable to the

negligence and unlawful conduct of the defendant itself. More

over, the district court erred in resolving these disputed

factual and legal issues by means of a summary judgment.

The district court's orders prohibiting or restrict

ing communications by plaintiffs and their counsel with class

members constituted prior restraints on expression and associa

tion in violation of the First Amendment. These orders are

directly contrary both to the Supreme Court's decision in

NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963), and to the intent of

Congress to encourage litigation against racial discrimination.

The orders are also plainly overbroad.

In the context of this case, the restrictions on

the First Amendment rights of plaintiffs and their counsel

to speak, and on the rights of the class members to hear,

are so unfair and one-sided as to constitute a denial of

due process in violation of the Fifth Amendment. These

restrictions also impermissibly interfere with the efforts

of plaintiffs and their counsel to carry out their congressionally

mandated responsibilities as "private attorneys general" and

their obligation under Rule 23 of the Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure to provide fair and adequate representation to the

class. In addition, the orders prohibiting or restricting

communications are inconsistent with the Federal Rules of

Civil Procedure and are therefore beyond the powers of the

district court under 28 U.S.C. § 2071 and Rule 83.

14

ARGUMENT

I. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN DISMISSING THE PLAINTIFFS'

TITLE VII CLAIMS FOR FAILURE TO FILE A CIVIL ACTION

WITHIN NINETY DAYS OF THE ISSUANCE BY THE EEOC OF

LETTERS ADVISING PLAINTIFFS OF THE FAILURE OF CON

CILIATION EFFORTS.

Section 706(f) of Title VII provides that if the EEOC

has not within 180 days from the filing of a charge of

discrimination "filed a civil action ... or the Commission

has. not entered into a conciliation agreement to which the

person aggrieved is a party, the Commission ... shall so

notify the person aggrieved and within ninety days after

the giving of such notice a civil action may be brought ..."

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(f)(1). The court below read this

language as requiring the dismissal of the Title VII claims

in this case on the ground that plaintiffs Bernard, Brown,

and Johnson had not brought their civil action within ninety

days of notification by the EEOC that the respondents named

in their EEOC charges— the defendants below— did not wish to

entertain conciliation discussions (A. 182-184). However,

the record shows that the amended complaint in this action

was filed well within ninety days of the receipt by plaintiffs

Bernard and Brown of EEOC "Notices of Right to Sue Within 90

Days" dated June 11, 1976 (A. 73; Supp. App. 1A-2A).

15

As the district court noted, the EEOC in this case

utilized a two-letter notification procedure with respect

to charges on which it had made findings of "reasonable

cause," but which it had been unable to resolve through con

ciliation (A. 182-183). In the first letter, the EEOC

advised the charging party that the respondents

[did] not wish to entertain conciliation

discussions ... [and that] you are hereby

notified that you may request a "Notice

of Right to Sue" from this office at any

time. If you so request, the notice will

be issued, and you will have ninety (90)

days from the date of its receipt to file

suit in Federal District Court (A. 84, 87,

90) .

The second letter, entitled "Notice of Right to Sue

Within 90 Days," stated as follows:

Pursuant to Section 706(f) of Title VII

... you are hereby notified that you may,

within ninety (90) days of receipt of this

communication, institute a civil action in

the appropriate Federal District Court (Supp.

App. 1A-2A).

Several courts of appeals have held that, under the

EEOC two-letter procedure, the ninety day suit period does

not commence with receipt of the first letter, but only with

receipt of the second letter or of some other communication

clearly indicating that all EEOC administrative procedures

have been terminated. Garner v. E. I. DuPont de Nemours and

Co., 538 F.2d 611 (4th Cir. 1976); Weaver v. Joseph Schlitz

16

Brewing Co., F .2d ___, 13 EPD H 11,589 (6th Cir. 1977);

McGuire v. Aluminum Company of America, 542 F.2d 43 (7th

Cir. 1976); Lacy v. Chrysler Corp., 533 F.2d 353 (8th Cir.

en banc,)cert. denied, ___ U.S. ___, 12 EPD H 11,234 (1976);

Tuft v. McDonnell Douglas Corp., 517 F.2d 1301 (8th Cir.

1975), cert, denied, 423 U.S. 1052 (1976); Williams v .

Southern Union Gas Co., 529 F.2d 483 (10th Cir.), cert.

denied, ____ U.S. ___ , 12 EPD fl 11,234 (1976).

The Second Circuit has rejected the EEOC two-letter

procedure in a significantly different procedural context,

holding that the ninety day suit period commenced when the

plaintiff received notice that the EEOC had completed its

administrative proceedings by the issuance of a "no reasonable

cause" determination and a dismissal of the plaintiff's charge

of discrimination. De Matteis v. Eastman Kodak Co., 511 F.2d

306, 309-10, modified, 520 F.2d 409 (2d Cir. 1975). The

holding and underlying rationale of De Matteis are fully

consistent with the decisions in the other circuits in that

each court has held that the ninety day suit period begins to

run only upon notification of the completion of all administra

tive procedures. In cases such as De Matteis, where the EEOC

has notified the charging party of a finding of no reasonable

cause and a dismissal of the charge, the administrative

17

procedures have clearly come to an end. But in cases such

as the instant case, where the EEOC has found reasonable

cause and has been unable to conciliate the charge, the EEOC

must make a further determination as to whether it will file

a civil action. 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(f). The letters advis

ing plaintiffs that defendants did not wish to entertain

conciliation discussions contained no indication that the

EEOC had made any determination regarding the filing of a

civil action (A. 84, 87, 90). Thus, these letters did not

constitute notice of the completion of all administrative

procedures and they accordingly did not begin the running of

the ninety day suit period. See, Lacy v. Chrysler Corp.,

supra, 533 F.2d at 358-59.

This court recently resolved the two-letter issue in

Zambuto v. American Telephone and Telegraph Co., 544 F.2d

1333 (5th Cir. 1977). The court there held that an EEOC

two-letter procedure similar to that in the instant case was

improper under Title VII, but the court also held that its

ruling would be prospective, applying only to actions brought

in this circuit on or after April 11, 1977. Id.- at 1335.

Cf. De Matteis v. Eastman Kodak Co., supra, 520 F.2d 409.

The substantive ruling in Zambuto, therefore, does not apply

to the instant case, in which the complaint was filed on

18

May 18, 1976 (A. 4), and amended on July 19, 1976 (A. 66).

The adverse effects of any impropriety in the EEOC's two-

letter procedure thus cannot be visited upon the plaintiffs

here. 544 F.2d at 1336.

Moreover, while holding the two-letter procedure improper,

this court in Zambuto interpreted the above-quoted language

of section 706(f) in a manner consistent with the other cir

cuit court decisions cited above. The court stated as

follows:

This language [of 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5 (f) (1)]

has been read to require communication of

both the failure of conciliation and the

EEOC's decision not to sue in order to indi

cate clearly that the administrative process

has been completed. ... A notice which merely

informs the aggrieved party that conciliation

has failed, may not mean that no suit will be

brought [by the EEOC]. ... A letter only

announcing "no conciliation" would not fulfill

the statute's requirement for notice of both

inability to conciliate and a determination

not to sue by EEOC. 544 F.2d at 1335 (emphasis

in original).

Thus, even if the substantive ruling in Zambuto were

applicable to this case, it would dictate a finding that

the "first" letters here (A. 84, 87, 90), like the first

letter in Zambuto, "failed to furnish [the plaintiffs] ...

with the form of notice required under § 2000e-5(f)(1) to

start the 90-day period for filing suit." 544 F.2d at 1335.

Since the "failure of conciliation" letters were not

19

sufficient to start the running of the suit period, the

district court clearly erred in dismissing the plaintiffs'

Title VII claims on this ground.

Title VII "specifies with precision the jurisdictional

prerequisites that an individual must satisfy before he is

entitled to institute a lawsuit," and these prerequisites

are met when a plaintiff has "(1) filed timely a charge of

employment discrimination with the Commission, and (2) received

and acted upon the Commission's statutory notice of the

right to sue." Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S.

35, 47 (1974). See also, McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green,

411 U.S. 792, 798 (1973). Plaintiffs Bernard and Brown have

both clearly satisfied these requirements here. As the court

below recognized, it is not necessary for each named plain

tiff in a Title VII class action to satisfy these procedural

requirements (A. 181-182). Indeed, in Oatis v. Crown Zellerbach

Corp., 398 F.2d 495, 499 (5th Cir. 1968), this court explicitly

held that persons who have not filed EEOC charges or received

notices of their right to sue may be proper named plaintiffs

and Rule 23 class representatives, so long as one other named

plaintiff in the action has satisfied these requirements.

Thus, contrary to the decision in the court below, plaintiffs

Hayes, Tizeno, Johnson and Whitley are properly named in

20

conjunction with Bernard and Brown as plaintiffs and class

representatives with respect to the Title VII claims.

In addition, the district court erred in holding that

those named plaintiffs who had not satisfied the Title VII

requirements could not "maintain suit in their own right ...

and therefore could not adequately represent a class" (A.

182), in that the court failed to recognize that the plain

tiffs had also asserted claims under 42 U.S.C. § 1981. The

remedies available under Title VII and § 1981 are "separate,

distinct, and independent," and "the filing of a Title VII

charge and resort to Title VII's administrative machinery

are not prerequisites for the institution of a § 1981 action.

Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, Inc., 421 U.S. 454, 461,

460 (1975). Thus, even if none of the named plaintiffs had

satisfied the Title VII requirements, the district court

would be in error for refusing for this reason to permit them

to maintain the action under § 1981.

II. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN DISMISSING THE PLAINTIFFS'

CLAIMS UNDER 42 U.S.C. § 1981 AS BARRED BY THE STATUTE

OF LIMITATIONS.

Plaintiffs' original and amended complaints allege that

"black employees of Gulf Oil are, and have in the past; been

victims of systematic racial discrimination by defendants ...'

21

and that "prior and subsequent to July 2, 1965, Gulf Oil

engaged in policies, practices, customs and usages made

unlawful ..." (A. 8, 70). The complaints specify that the

defendants are at the present time continuing to engage in

numerous discriminatory practices in hiring, job assignment,

testing practices and selection criteria, wages, working

conditions, exclusion of blacks from higher paying craft

positions, promotion and upgrading practices, training oppor

tunities, and disciplinary and discharge practices (A. 8-10,

70-73). The present and continuing nature of these violations

is expressed in such unambiguous terms as "Gulf Oil unlawfully

has assigned and continues to assign ..." (A. 8, 70); "White

employees are given preference ..." (A. 8, 70); "The company

utilizes a battery of tests which discriminates ..." (A. 8,

71) ; "Black employees are now, and have in the past, been

paid less money for harder work under less desirable working

condirions __" (A. 9, 71); "Defendant company employs a

disproportionately small number of blacks in permanent craft

positions ..." (A. 9, 71-72); "Blacks have been and are now

confined to the lower-paying and less-preferred jobs ..." (A.

9, 72); "Blacks who perform the same or comparable work as

whites are given unequal pay and compensation ..." (A. 9-10

72) ; and "Gulf Oil discriminatorily assesses discipline and

discharge against black employees ..." (A. 10, 72).

22

Plaintiffs have alleged that these present and continuing

discriminatory practices violate both Title VII and 42 U.S.C.

§ 1981 (A. 8, 70). For the purposes of the motion to dismiss

_5/

the § 1981 claims as barred by the statute of limitations,

the district court was required to construe the plaintiffs'

allegations liberally and to accept them as true. Jenkins

v. McKeithen, 395 U.S. 411, 421-22 (1969); Belt v. Johnson

Motor Lines, Inc., 458 F.2d 443, 444 (5th Cir. 1972). Simi

larly, after converting the motion to dismiss into a motion

for summary judgment, the district court was required to view

"the inferences to be drawn from the factual material before

the court ... in the light most favorable to the party opposing

the motion." Gray v. Greyhound Lines, East, 545 F.2d 169, 174

(D.C. Cir. 1976). Failure to do so is reversible error.

Adickes v. S. H. Kress Co., 398 U.S. 144, 153-61 (1970);

5/ Since § 1981 contains no limitations period, the court

must borrow the state statute of limitations which applies

to the most analogous state action. Johnson v. Railway

Express Agency, Inc., 421 U.S. 454, 462 (1975). With respect

to the § 1981 claims for back pay in the instant case, the

applicable statute is the two year Texas limitation on actions

to recover unpaid wages, Tex. Rev. Civ. Stat. Ann. Art.

5526(4). Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 491 F.2d

1364, 1378 (5th Cir. 1974). A longer period of limitations

may apply to the § 1981 claims for declaratory and injunctive

relief. See Boudreaux v. Baton Rouge Marine Contracting Co.,

437 F.2d 1011, 1017, n. 16 (5th Cir. 1971); Johnson v. Goodyear

Tire & Rubber Co., supra, 491 F.2d at 1378, n. 48; Hines v.

Olinkraft, Inc., 413 F. Supp. 1360, 1364 (W.D. La. 1976). Cf.

Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, Inc., 421 U.S. at 467, n. 7.

23

Sperry v. Barggren, 523 F.2d 708 (7th Cir. 1975); Aulds v .

Foster, 484 F.2d 945, 946 (5th Cir. 1973).

Despite these clear legal standards, the court below

found that there were "no circumstances of continuous dis

crimination ..." (A. 184). The record contains absolutely

no support for this finding. On the contrary, plaintiffs

allege numerous present and continuing discriminatory practices

and the court was obliged to accept these allegations as true.

The court below also found that the pattern of discrimination

alleged by plaintiffs "has long since been eliminated" (A.

184). This finding is equally devoid of any support in the

record, and it is especially baffling since the plaintiffs

were never given an opportunity to prove that such a pattern

had ever existed.

Under the appropriate legal standards, it must be assumed

that the defendants were continuing to engage in the alleged

discriminatory practices at least until the date on which the

amended complaint was filed. As this court has previously

held, present and continuing discriminatory employment practices

are not insulated from attack: "[T]here is no reason to lock

the courthouse door to [a plaintiff's] claim because he has

alleged a contemporary course of conduct as an act of discrim

ination." Belt v. Johnson Motor Lines, Inc., supra, 458 F.2d

24

at 445. The words of the Supreme Court in an antitrust case

are directly applicable to this employment discrimination

case:

We are not dealing with a violation which, if

it occurs at all, must occur within some spe

cific and limited time span. ... Rather, we

are dealing with conduct which constituted a

continuing violation of the Sherman Act and

which inflicted continuing and accumulating

harm on [the plaintiff]. Although [the

plaintiff] could have sued in 1912 for the

injury then being inflicted, it was equally

entitled to sue in 1955. Hanover Shoe, Inc.

v. United Shoe Machinery Corp., 392 U.S. 481,

502, n. 15 (1968).

It is firmly established in this circuit and elsewhere

that claims of present and continuing discriminatory employ

ment practices, such as those alleged here, are not barred by

statutes of limitation, and that "for the purpose of the

statute of limitations a cause of action accrues whenever an

individual is directly and adversely affected by that discrim

inatory practice." EEOC v. Griffin Wheel Co., 511 F.2d 456,

459 (5th Cir. 1975) (Title VII); United States v. Georgia

Power Co., 474 F.2d 906, 922 (5th Cir. 1973) (Title VII);

Allen v. Amalgamated Transit Union Local 788, ___ F.2d ___,

14 FEP Cases 1494, 1498 (8th Cir. 1977) (§ 1981); Davis v .

County of Los Angeles, ___ F.2d ___ , 12 EPD ^ 11,219 at 5650

(9th Cir. 1976) (Title VII and §§ 1981, 1983); Williams v.

Norfolk & Western Ry. Co., 530 F.2d 539, 541-42 (4th Cir. 1975)

25

(Title VII and § 1981); Marlowe v. Fisher Body, 489 F.2d 1057,

1063 (6th Cir. 1973) (§ 1981); Macklin v. Spector Freight

Systems, Inc., 478 F.2d 979, 994 (D.C. Cir. 1973) (§ 1981).

See also, Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, Inc., 421 U.S.

454, 467, n. 13 (1975) (dictum). Cf. Baker v. F. & F .

Investment, 420 F.2d 1191, 1200 (7th Cir. 1970) (42 U.S.C.

§ 1982). As the Supreme Court held in a recent Title VII

decision, the "critical question" in determining the timeli

ness of a claim of continuing discrimination "is whether any

present violation exists." United Air Lines, Inc, v. Evans,

45 U.S.L.W. 4566, 4567 (U.S., May 31, 1977) (emphasis in

_§/original). Since the plaintiffs in the instant case have

set forth numerous present violations, their claims clearly

6/ The plaintiff in Evans was a rehired employee who had

not filed a timely EEOC charge challenging her termination

in 1968, but who claimed in a charge filed after she had

been rehired in 1972 that the employer's seniority system

had a continuing impact on her pay and fringe benefits which

carried into the present the effects of the allegedly unlaw

ful previous termination. The Court found that the plaintiff

in Evans had not alleged facts establishing that a violation

was occurring within the applicable limitations period, and

that her Title VII complaint should therefore be dismissed.

45 U.S.L.W. at 4567. Here, in contrast, numerous present

and continuing violations have been alleged, and under the

reasoning of Evans these claims are not barred by the

statute of limitations.

26

are not time-barred.

The statute of limitations will indeed limit the period

of the defendants' back pay liability for continuing viola

tions of § 1981. Allen v. Amalgamated Transit Union, supra,

___ F.2d at ___, 14 FEP Cases at 1498. Cf. Occidental Life

Insurance Co. v. EEOC, 45 U.S.L.W. 4752, 4757 (U.S., June 20,

1977); Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 424-25

(1975). But there is simply no basis for the conclusion of

the court below that the statute of limitations poses an

absolute bar to the assertion of claims of present and

ongoing discriminatory employment practices.

The district court also viewed the filing of EEOC charges

by three of the named plaintiffs in 1967 as having some effect

on the application of the Texas statute of limitations to the

claims which plaintiffs now assert under § 1981 (A. 184).

This view of the law is clearly erroneous. As the Supreme

Court has held, "the remedies available under Title VII and

under § 1981 ... are separate, distinct, and independent."

Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, Inc., supr a , 421 U.S. at

461. The district court erred in holding that the filing of

EEOC charges in the past somehow deprived the plaintiffs of

the right to seek redress for present violations of § 1981.

27

III. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN HOLDING THAT THIS ACTION

MAY BE BARRED BY THE DOCTRINE OF LACHES.

The court below stated that it "acknowledges a most

compelling argument for the application of the equitable

doctrine of laches in this particular case, based not only

on the obvious lack of diligence on the part of the plaintiffs,

but a recognition that to put this defendant to the task of

obtaining records and locating witnesses after the expiration

of such a lengthy period would pose a particularly onerous

burden" (A. 184-185). To the extent that this language indi

cates a holding that the action is barred by laches, the

court was in error and its decision must be reversed. Even

if an outright reversal on this point would be inappropriate,

this court, for the guidance of the court below on remand,

should state the proper principles to be applied in resolving

the issue of laches in this case. Cf. Boudreaux v. Baton

Rouge Marine Contracting Co., 437 F.2d 1011, 1017, n. 16

(5th Cir. 1971).

Where, as here, an action in federal court asserts

federally created claims which are essentially equitable in

nature, Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 495 F.2d 398,

406 (5th Cir.), cert, denied in pertinent part, 419 U.S. 1050

(1974), the applicability of the doctrine of laches is

28

determined by federal law. See Holmberg v. Armbrecht, 327

U.S. 392, 395 (1946); Baker v. F. & F. Investment, 420 F.2d

1191, 1193, n. 3 (7th Cir. 1970). In order to establish

laches, the party asserting the defense must prove that

there has been inexcusable delay and resulting prejudice.

Costello v. United States, 365 U.S. 265, 282 (1961); Wheat

v. Hall, 535 F.2d 874, 876 (5th Cir. 1976); Ecology Center of

Louisiana v. Coleman, 515 F.2d 860, 865 (5th Cir. 1975).

Neither of these elements was established here.

The crux of the company's argument with respect to laches

is that "certain important relevant testimony and documents

have not been preserved because Gulf did not know the six

named plaintiffs in this lawsuit or the class they purport

to represent had potential claims against it" (R. 303; Supp.

App. 16A). This statement is patently false. The company

has acknowledged and the district court has correctly found

that, as early as 1967, three of the named plaintiffs filed

EEOC charges of discrimination naming the company as a

respondent (A. 184). As of February 1975, at least forty (40)

related charges against the company had been pending before

the EEOC for eight years (A. 84, 87, 90 [listing of EEOC case

numbers]). Moreover, the company claims that it was engaged

for those eight years in negotiations with federal agencies

29

concerning charges of discrimination, and that those negotia

tions continued until a conciliation agreement was signed on

April 14, 1976 (R. 25; Supp. App. 8A). Under these cir

cumstances, the company cannot reasonably expect this court

to believe that it was unaware of potential claims of dis

crimination by the named plaintiffs and class members.

After the charges of discrimination were filed with the

EEOC in 1967, plaintiffs could justifiably rely on that

agency to carry out its statutory enforcement responsibili

ties. As the Supreme Court has recently reaffirmed, Congress

in enacting Title VII "selected 'cooperation and voluntary

compliance ... as the preferred means for achieving' the goal

of equality of employment opportunities," and "[t]o this end,

Congress created the EEOC and established an administrative

procedure whereby the EEOC 'would have an opportunity to settle

disputes through conference, conciliation, and persuasion

before the aggrieved party was permitted to file a lawsuit.'"

Occidental Life Insurance Co. v. EEOC, 45 U.S.L.W. 4752, 4755

(U.S., June 20, 1977); Alexander v. Gardner Denver Co., 415

U.S. 36, 44 (1974); United States v. Allegheny-Ludlum

Industries, Inc., 517 F.2d 826, 846-48 (5th Cir. 1975), cert,

denied, 425 U.S. 944 (1976). The 1972 amendments to Title VII,

which empowered the EEOC to bring civil actions,' preserved

these administrative functions and duties of the EEOC and

30

retained the preference for settling disputes in an informal,

noncoercive fashion- Occidental Life Insurance Co., supra,

45 U.S.L.W. at 4755.

The legislative history of the 1972 amendments clearly

reflects the intent of Congress to permit, and indeed for a

specified period to require, charging parties to rely on

the efforts of the EEOC to obtain compliance with Title VII.

The Senate committee evaluating the proposed amendments

stated that, "where the Commission is not able to pursue

a complaint with satisfactory speed, or enters into an

agreement which is not acceptable to the aggrieved party,

the bill provides that the individual shall have an

opportunity to seek his own remedy. . . ." S. Rep. No. 415,

92d Cong., 1st Sess., 23 (1971) (emphasis added). Similarly,

the section-by-section analysis which was presented with

the conference committee report on the 1972 amendments stated

that

the provisions . . . allow the person

aggrieved to elect to pursue his or

her own remedy under this title in

the courts where there is agency

inaction, dalliance or dismissal of

the charge, or unsatisfactory

resolution.

It is hoped that recourse to the

private lawsuit will be the exception

31

and not the rule, and that the vast

majority of complaints will be

handled through the offices of the

EEOC. 118 Cong. Rec. 7168, 7565

(1972) (emphasis added).

See Occidental Life Insurance Co. v. EEOC, supra, 45

U.S.L.W. at 4754-55; EEOC v. Louisville & Nashville

R.R. Co., 505 F.2d 610, 615 (5th Cir. 1974), cert.

denied, 423 U.S. 824 (1975); EEOC v. Cleveland Mills

Co., 502 F .2d 153, 156 (4th Cir. 1974), cert, denied,

420 U.S. 946 (1975).

It is only when the EEOC has notified the charging

party of the completion of its administrative processes

that he must exercise his right to sue. Zambuto v .

American Telephone & Telegraph Co., 544 F2d 1333, 1335 (5th

Cir. 1977). See pp. 16-20, supra. This is what plaintiffs

have done. Indeed, the legislative history cited above

indicates that, in awaiting the results of EEOC

conciliation efforts which continued until April 1976 and

then promptly filing a civil action when they found the

EEOC conciliation agreement unsatisfactory, plaintiffs

did precisely what Congress intended. Thus, there was

no inexcusable delay in bringing this suit, but rather

32

justifiable reliance on the EEOC in accordance with the intent

of Congress. To hold otherwise would penalize the plaintiffs

for this reliance and would, contrary to the settled rule in

this circuit elsewhere, deprive the plaintiffs of their

statutory right to sue because of delay or lack of diligence

on the part of the EEOC. See Zarobuto, supra, 544 F.2d at

1336; Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., supra, 495 F.2d

at 404-405; Beverly v. Lone Star Lead Construction Corp.,

437 F .2d 1136, 1140 (5th Cir. 1971); Dent v. St. Louis -

San Francisco R. Co., 406 F.2d 399, 403 (5th Cir. 1969))

Choate v. Caterpillar Tractor Co., 402 F.2d 357, 361 (7th

Cir. 1968).

The second element necessary to establish the defense

of laches — a showing of prejudice resulting from the

delay — is also absent here. The company has asserted

that, throughout the period since 1967, during which it

has undeniably been on notice that claims of discrimination

were pending against it (See pp. 29-30, supra), it has

failed to preserve the testimony of certain witnesses and

it has destroyed numerous records and documents pertinent to

33

those claims (A. 174-179). Where the defendant has been on

notice that its conduct is being challenged, and indeed has

engaged in settlement negotiations throughout the period

in question, there is no basis for a finding of prejudice.

See Kohn v. Royall, Koeqel & Wells, 59 F.R.D. 515, 518 n.3

(S.D.N.Y. 1973), app. dismissed, 496 F.2d 1094 (2d Cir.

1974). The problems of proof which such a defendant may

experience are attributable not to any conduct of the

plaintiffs, but rather to its own negligence.

The company's destruction of relevant records and

documents appears to go beyond mere negligence. This

conduct is a clear violation of Title VII and of the

applicable EEOC regulations, which have been published

in the Code of Federal Regulations since 1967. Section

709(c) of Title VII provides that

[e]very employer, employment agency, and labor

organization subject to this subchapter shall

(1) make and keep such records relevant to

the determinations of whether unlawful employ

ment practices have been or are being

committed, (2) preserve such records for such

periods, and (3) make such reports therefrom

as the Commission shall prescribe by regulation

or order, after public hearing, as reasonable,

34

necessary, or appropriate for the

enforcement of this title or the

regulations or orders thereunder

- . . . 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-8(c).

The regulations adopted by the EEOC pursuant

to this section provide in pertinent part as follows:

. . . Where a charge of discrim

ination has been filed, or an action

brought by the Commission or the Attorney

General, against an employer under Title

VII, the respondent employer shall preserve

all personnel records relevant to the

charge or action until final disposition

of the charge or the action. The term

"personnel records relevant to the charge,"

for example, would include personnel or

employment records relating to the

aggrieved person and to all other

employees holding positions similar to

that held or sought by the aggrieved

person and application forms or test

papers completed by an unsuccessful

applicant and by all other candidates

for the same position as that for which

the aggrieved person applied and was

rejected. The date of "final disposition

of the charge or action" means the date of

expiration of the statutory period within

which the aggrieved person may bring an

action in a U.S. District Court or, where

an action is brought against an employer

either by the aggrieved person, the Com

mission or by the Attorney General, the

date on which such litigation is termin

ated. 29 C.F.R. § 1602.14(a) (1967) and

31 Fed. Reg. 2833 (Feb. 17, 1966).

The record demonstrates beyond dispute that the

company has violated these provisions by destroying

35

relevant personnel records prior to the disposition of

EEOC charges and prior to termination of this litigation

(A. 174-179). The company cannot base its laches defense

on its own violation of these statutory record-keeping

requirements. See Anderson v. Mt. Clemens Pottery Co.,

328 U.S. 680, 688 (1946); Skipper v. Superior Dairies, Inc.,

512 F.2d 409, 419-20 (5th Cir. 1975). Plaintiffs cannot be

penalized for the defendant's illegal conduct, which is a

circumstance "beyond the control of the aggrieved party."

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., supra, 495 F.2d at 405.

Even if the defendants could make the requisite showings

of delay and resulting prejudice, the defense of laches,

like the statute of limitations (see pp. 24-27, supra).

would not bar an action challenging present and ongoing

discriminatory practices. Harper v. Mayor & City Council of

Baltimore, 359 F.Supp. 1187, 1195-96 and n.12 (D. Md.),

modified and aff'd, 486 F2d 1134 (4th Cir. 1973). Cf.

Hanover Shoe, Inc, v. United Shoe Machinery Corp., supra,

392 U.S. at 502 n.15. At most, laches would, if established,

constitute on the facts of this case an equitable limitation

36

on the period of the defendant's back pay liability, not a

ground for dismissal of the entire action. See EEOC v.

Airquide Corp., 539 F.2d 1038, 1042 n.7 (5th Cir. 1976);

Guerra v. Manchester Terminal Corp., 498 F.2d 641, 653 and

n.7 (1974); Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., supra,

495 F .2d at 406. Cf. Occidental Life Insurance Co. v.

EEOC, 45 U.S.L.W. 4752, 4757 (U.S., June 20, 1977);

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 424-25 (1975).

Finally, a motion for summary judgment presents a

singularly inappropriate vehicle for the resolution of the

factual and legal issues raised by the defense of laches.

Under Rule 56(c) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure,

the moving party has the burden of showing that there is no

genuine issue as to any material fact and that judgment is

warranted as a matter of law. Boazman v. Economics Laboratory,

Inc., ____ F.2d ____, 13 EPD H 11,329 at 6106 (5th Cir. 1976).

Both the district court and this court on appeal "must draw

inferences most favorable to the party opposing the motion,

and take care that no party will be improperly deprived

of a trial of disputed factual issues." Id; United States

Steel Corp. v. Darby, 516 F.2d 961, 963 (5th Cir. 1975).

37

As this court has held, the existence and extent of any

prejudice to a Title VII defendant resulting from delay

in notification of a claim is precisely the kind of

issue which should not be resolved on a summary judgment

motion; instead, even where a supporting affidavit

"shows the possibility of prejudice," the district court

is required to undertake a "full exploration of the facts,"

and its failure to do so is reversible error. EEOC v.

Airguide Corp., supra, 539 F.2d at 1042. The doctrine of

laches, as applied to employment discrimination cases,

[b]y its very nature . . . is not a proper

basis for summarily dismissing a claim.

The doctrine is first a matter of affirm

ative defense which must be pleaded and

second a matter of evidentiary facts which

must be proven. On the present record,

[the court] cannot determine plaintiff's

delay is "inexcusable" or whether it has

caused actual "prejudice" to defendant.

Additionally, the "balancing of equities"

required by the doctrine is best accom

plished after full development of all

relevant facts. Evans v. Dow Chemical

Co., 13 FEP Cases 1461, 1466 (D. Colo.

1975).

38

IV. THE ORDERS OF THE DISTRICT COURT RESTRICTING

COMMUNICATIONS BY PLAINTIFFS AND THEIR COUNSEL

WITH CLASS MEMBERS ARE UNCONSTITUTIONAL AND ARE

BEYOND THE AUTHORITY OF THE DISTRICT COURT.

A . The Orders Are Overbroad Abridgments of the

Freedom of Speech and Freedom of Association

Guaranteed by the First Amendment.

On the basis of unsworn allegations that counsel for

plaintiffs had engaged in unethical conduct (R. 17-18; Supp.

App. 4A-5A), the court below prohibited all communications

by the parties and their counsel with any actual or potential

class member not a formal party to the action (A. 30-31). The

court subsequently modified the order to prohibit all such

communications without its prior approval of both the com

munication and the proposed addressees; to permit certain

communications initiated by a client or prospective client;

to permit communications occurring in the regular course of

business; to require that any constitutionally protected

communication be filed with the court within five days after

its occurrence; and to permit the company through the district

court to make tenders of "back pay awards" to class members

and to solicit releases from class members under the company's

conciliation agreement with the EEOC and the DOI (A. 56-61).

When the plaintiffs and their counsel sought permis sion to

distribute a notice regarding the conciliation agreement and

the releases to the class members and to discuss these subjects

with the class members within the forty-five day period allowed

for their consideration of the company's offer, permission

39

was denied (A. 62-65, 157). These orders have deprived the

plaintiffs and their counsel of the right to discover the

case and effectively present the claims of the class members,

and these orders have infringed the right of the class members

to consult with and be advised by the attorneys who seek to

represent their class concerning the settlement offered by

the defendant and the purported waiver of their civil rights.

Such prior restraints on expression come to the court

with a "heavy presumption" against their constitutional

validity. Southeastern Promotions, Ltd, v. Conrad, 420 U.S.

546, 558 (1975); New York Times Co. v. United States, 403

U.S. 713, 714 (1971); Organization for a Better Austin v.

Keefe, 402 U.S. 415, 419 (1971); Bantam Books, Inc, v.

Sullivan, 372 U.S. 58, 70 (1963); Near v. Minnesota, 283 U.S.

697 (1931); Rodgers v. United States Steel Corp., 536 F.2d

1001, 1007 (3rd Cir. 1976). Notwithstanding the "heavy burden

of showing a justification for the imposition of such a re

straint, " Organization for a Better Austin v. Keefe, supra

at 419, and notwithstanding the requirements that such a

restraint "first, must fit within one of the narrowly defined

exceptions to the prohibition against prior restraints, and,

second, must have been accomplished with procedural safeguards

that reduce the danger of suppressing constitutionally pro

tected speech," Southeastern Promotions Ltd, v. Conrad, supra

at 559, the court below did not make any findings of fact or con

clusions of law with respect to these orders, nor did it state

40

any reason for the orders.

The company has contended that the orders were necessary

to prevent allegedly unethical conduct by counsel for plain-

_ZJtiffs and to permit the continued smooth operation of the

settlement and waiver machinery which had been set into motion

by the company's conciliation agreement with the federal agencies.

As for the first asserted justification, there has been no

showing that any unethical conduct has occurred. The company's

concern appears to focus on alleged solicitation of clients.

However, none of the attorneys for the plaintiffs has accepted

or expects to receive any compensation from the named plaintiffs,

from any additional named plaintiffs who may be joined in the