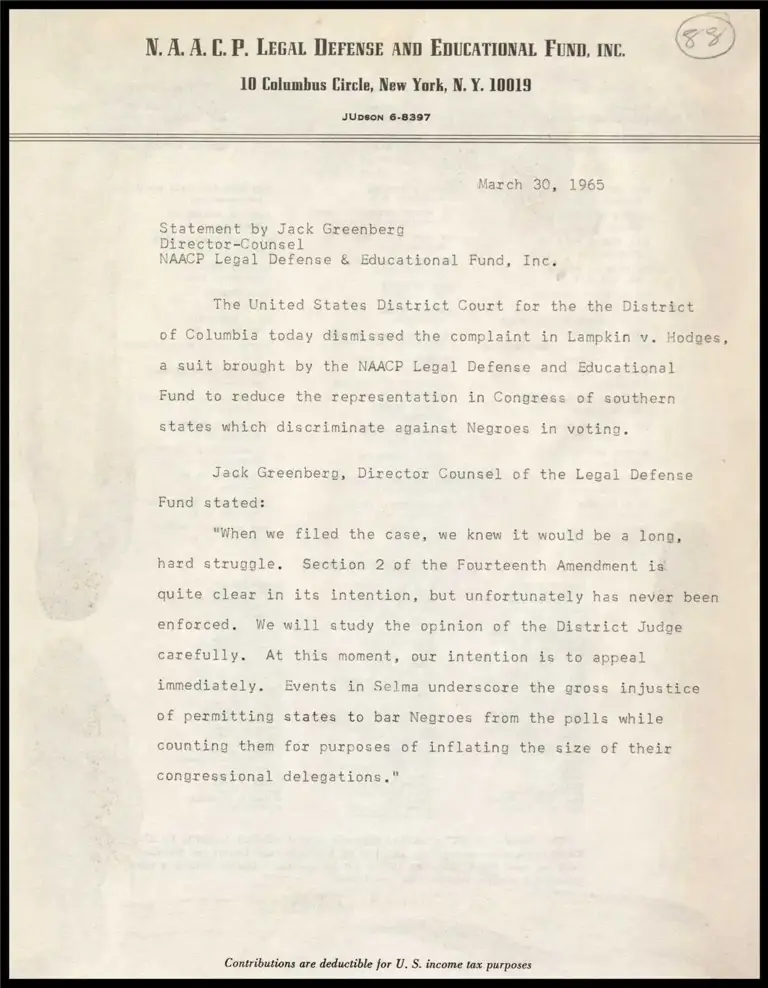

Greenberg Statement on Dismissal of Suit to Reduce Congressional Representation of State Practicing Voter Discrimination

Press Release

March 30, 1965

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Volume 2. Greenberg Statement on Dismissal of Suit to Reduce Congressional Representation of State Practicing Voter Discrimination, 1965. fbbe72da-b592-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1c9707de-f069-4272-8567-95ab846d2683/greenberg-statement-on-dismissal-of-suit-to-reduce-congressional-representation-of-state-practicing-voter-discrimination. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

N. A. A.C. BP. Lega DErense AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, 1

10 Columbus Circle, New York, N. Y. 10019

JUDSON 6-8397

sreenberg

never been

study th th District Judge

is moment, our intention is to a

Events in Selma

of permitting states to bar Negr from the polls while

counting them of y the size of

Contributions are deductible for U. S. income tax purposes