Muntaqim v. Coombe Brief in Support of Plaintiff-Appellant and in Support of Reversal on Behalf of Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

February 4, 2005

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Muntaqim v. Coombe Brief in Support of Plaintiff-Appellant and in Support of Reversal on Behalf of Amici Curiae, 2005. 841356f1-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1d2a6f61-85f8-45c2-b1c7-f3021d2d8b55/muntaqim-v-coombe-brief-in-support-of-plaintiff-appellant-and-in-support-of-reversal-on-behalf-of-amici-curiae. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

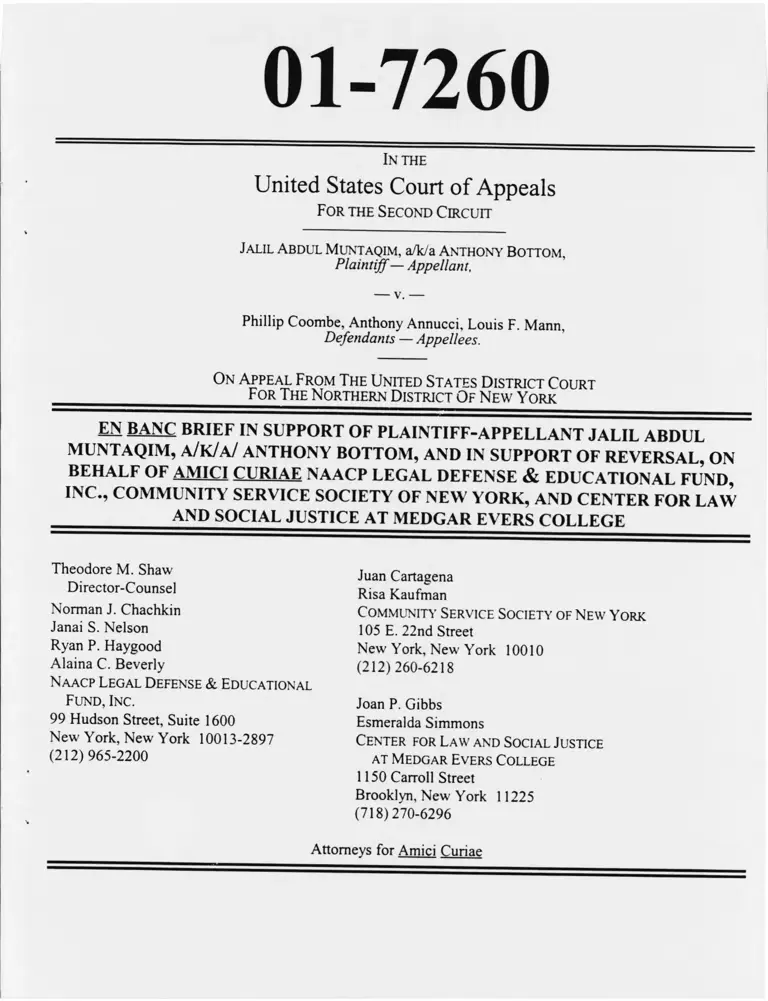

01-7260

In the

United States Court of Appeals

For the Second Circuit

Jalil Abdul Muntaqim, a/k/a Anthony Bottom,

Plaintiff — Appellant,

— v. —

Phillip Coombe, Anthony Annucci, Louis F. Mann,

Defendants — Appellees.

On A ppeal From The U nited States D istrict Court

For The N orthern D istrict Of N ew Y ork

EN BANC BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFF-APPELLANT JALIL ABDUL

MUNTAQIM, A/K/A/ ANTHONY BOTTOM, AND IN SUPPORT OF REVERSAL, ON

BEHALF OF AMICI CURIAE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE & EDUCATIONAL FUND,

INC., COMMUNITY SERVICE SOCIETY OF NEW YORK, AND CENTER FOR LAW

AND SOCIAL JUSTICE AT MEDGAR EVERS COLLEGE

Theodore M. Shaw

Director-Counsel

Norman J. Chachkin

Janai S. Nelson

Ryan P. Haygood

Alaina C. Beverly

N aacp Legal Defense & Educational

Fund , Inc .

99 Hudson Street, Suite 1600

New'York, New York 10013-2897

(212) 965-2200

Juan Cartagena

Risa Kaufman

Community Service Society of New York

105 E. 22nd Street

New York, New York 10010

(212) 260-6218

Joan P. Gibbs

Esmeralda Simmons

Center for Law and Social Justice

at Medgar Evers College

1150 Carroll Street

Brooklyn, New York 11225

(718)270-6296

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

Pursuant to Rule 26.1 of the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure, the NAACP

Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc., Community Service Society of New York,

and the Center for Law and Social Justice at Medgar Evers College, by and through

the undersigned counsel, make the following disclosures:

Counsel for Plaintiffs-Appellants, all not-for-profit corporations of the State of

New York, are neither subsidiaries nor affiliates of a publicly owned corporation.

Janai S. Nelson, Esq.

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, Suite 1600

New York, NY 10013

(212) 965-2237

jnelson@naacpldf.org

l

mailto:jnelson@naacpldf.org

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEM ENT.......................................................... i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES............................................................................... ^

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE ................................................................................. j

BACKGROUND ................................................................................... 3

INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF THE ARGUM ENT................................5

ARGUM ENT..................................................................................... 7

L Proof Required to Establish A Violation of Section 2

of the VRA (Court’s En Banc Question No. 3 ) ............................................. 7

A. Disparate Impact of New York Election Law §5-106..........................8

B. Totality of the Circumstances T e s t ..................................................... 8

i. Evidence of Discrimination in the Criminal Justice System . . 11

a- Type of Evidence (Court’s En Banc

Question No. 3lait ............................................................ \ \

b- Quantum of Proof (Court’s En Banc

Question No. 3IbB ............................................................20

c- Relevance of Evidence of Discrimination in

Federal and State Criminal Justice System

(Court’s En Banc Question No. 3 tc ) ) ..............................22

II. Additional Senate Factors ........................................................ 23

III. Evidence of Intentional Discrimination in the Enactment of

New York’s Felon Disfranchisement Law s.......................................................26

CONCLUSION .................................................................................................... 29

ii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES

Baker v. Pataki.

58 F.3d 814, 816 (2d Cir. 1995), vacated in part. 1996 U.S. App. LEXIS

13133 (2d Cir. 1996)................................................................................. 12> 13

Baker v. Pataki.

85 F.3d 919 (2d Cir. 1996) ...................................................................... 13

Burton v. City of Belle Glade.

178 F.3d 1175 (11th Cir. 1999).................................................................. g

Campaign for Fiscal Equity v. New York

719 N.Y.S.2d 475 (2002), rev'd , 245 A.D.2d 1,

744 N.Y. S.2d 130 (1st Dept. 2002) ............................................. 24

Farrakhan v. Washington

338 F.3d 1009 (9th Cir. 1003), cert, denied. U S

125 S. Ct. 477 (2004)................................................... 777’ ............4 ,9 , 12

Farrakhan v, Washington

No. CS-96-76-RHW (E.D. Wash.) ........................................................3? 4

Goosby v. Town Board of the Town of Hempstead.

180 F.3d 476 (2d Cir. 1999) ................................................. jq

Hayden v. Pataki. 2004 WL 1335921 (S.D.N.Y. June 14, 2004)

(order granting motion for judgment on the pleadings), appeal docketed

No. 04-3886-PR................................................................ 7 ^ 7 7 “ ' 3

Johnson v. Bush

353 F.3d 1287 (11th Cir. 2 0 0 3 ).............................................................. 3> 4

Johnson v. DeGrandv

512 U.S. 997(1994)............................................................................... 9> 10

iii

McCleskev v. Kemp

481 U.S. 279(1987)................................................................................... 20

Muntaqim v. Coomhe.

366 F.3d 102 (2d Cir. 2004) .................................................................... 12

Rodriquez v. Pataki.

308 F. Supp. 2d 346 (S.D.N.Y. 2004), afFd, 125 S. Ct. 627 (2004) . . . . 3

Thornburg v. Gingles

478 U.S. 30 (1986).............................................................. 9, 10, 20, 21, 22

U.S. v. Armstrong.

517 U.S. 456 (1996)................................................................................... 20

CONSTITUTIONS AND STATUTES

N.Y. Const. (1821), art. II, § 2 ................................................................................. 27

N.Y. Const, art. II, § 2 (amended 1894) ..................................................... 28

N.Y Elect. Law §5-106 ..................................................................................... ....

Section 2 of Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. § 1973 .........................................paSsim

S. Rep. No. 97-417 (1982), reprinted m 1992 U.S.C.C.A.N. 177, 179 .........passim

42 U.S.C. § 1973(a).................................................................................................. ... .

U.S. Const, amend. XV ................................................................ 28

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Brief for Plaintiff-Appellant In Banc ........................................................................ ...

Nathaniel Carter, William Stone and Marcus Gould, Reports of the

Proceedings and Debates of the Convention of 1821 at 1QS ..................... 26

iv

Constitutional Convention of 1846, Debates of 1846. at 1033 ........................ 27, 28

Jeffrey Fagan & Garth Davies, Street Stops and Broken Windows:

Terry, Race and Disorder in New York Citv. 28 Fordham Urb L J 457

458-462 (2000) ............................................................................................ ’ 17

Jeffrey Fagan, Valerie West, and Jan Holland, Reciprocal Effects of

Crime and Incarceration in New York City N eighborhoods 30 Fordham

Urb. L. J. 1551 (2 0 0 3 )............................................................................... 18> 19

The Franklin H. Williams Judicial Commission on Minorities, Equal Justice: A

Work in Progress, Five Year Report, 1991-1996 ...................................... 34

Tushar Kansal, The Sentencing Project, Racial Disparity in Sentencing-

A Review of the Literature ......................................................................... 13

Mark Levitan, Community Service Society, A Crisis of Black Male

Employment: Unemployment and Joblessness in New York

City 2003. 2, 6 (2004) ..................................................................................... 25

Manhattan Borough President’s Commission to Close the Health Divide,

Closing The Health Divide: What Government Can Do to Eliminate

Health Disparities Among Communities of Color in New York City

(October 2004)................................................................................. 24

Mason Tillman Associates, Ltd., Report: City of New York

Disparity Study (December 2004),

available at http://www.nvccouncil.info/pdf files/reports/citvnvrpt.pdf. . . 24

James Nelson, New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services,

Disparities in the Processing Felony Arrests in

NYS. 1990-1992 U 995^

Cong. Globe, 41 st Cong. 2d Sess., at 1447-81 ........................................................ 28

14, 15

http://www.nvccouncil.info/pdf_files/reports/citvnvrpt.pdf

New York State Judicial Commission on Minorities, New York

State Judicial Commission on the Courts, Report of the New York State

Judicial Commission on Minorities. Volume Two: The Public and the

Courts. 139-177 (Apr. 1991)............................................................ j

Office of the Attorney General of the State of New York, Civil

Rights Bureau, The New York City Police Department’s “Stop & Frisk”

Practices 0 9 9 9 ) ................................................. y

Cassia Spohn, U.S. Dep't of Justice, Thirty Years of Sentencing

Reform: The Quest for a Racially Neutral Sentencing Process 3 Crim J

427,444-450,475 (2000) ................................................... ’

vi

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE

Amici curiae are three non-profit, non-partisan legal organizations with lengthy

histories in advocacy and litigation in the area of voting rights. Amici curiae are also

the attorneys for the plaintiffs in Hayden v. Pataki. a class action brought on behalf

of Black and Latino prisoners, parolees, and community members to challenge New

York State s felon disfranchisement laws on the grounds that these laws

impermissibly deny and dilute the nght to vote of plaintiffs in violation of, inter aha,

the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution and Section 2 of

the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA). Havden is currently on appeal before this

Court.1

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. (LDF) was founded in

1940 under the leadership of the late Associate Supreme Court Justice Thurgood

Marshall. Its primary purpose is to provide legal assistance to poor African

Americans. LDF has been involved in more cases before the United States Supreme

Court than any other legal organization, except for the U.S. Department of Justice,

including every seminal Supreme Court case on the issue of voting rights. In addition

to serving as co-counsel in Havden. LDF is also co-counsel for the plaintiffs in

Hayden v. Pataki, 2004 WL 1335921 (S.D.N.Y. June 14, 2004) (order granting

motion for judgment on the pleadings), appeal docketed. No. 04-3886-PR (2d Cir

July 13, 2004).

1

Farrakhan v. Washington, No. CS-96-76-RHW (E.D. Wash.), a case brought by

Blacks, Latinos and Native Americans challenging Washington State’s felon

disfranchisement laws. LDF is also a founding member of the Right to Vote

Campaign, a national collaborative of eight organizations seeking to challenge state

felon disfranchisement laws through litigation, legislative action, and public

education.

For more than 160 years, the Community Service Society of New York (CSS)

has worked to improve the lives and enhance the political participation of the poor.

CSS has challenged an array of barriers to and discrimination in voting in New York.

Since 2002 CSS has directly challenged New York laws and policies that impede poor

voters from participating in the political process because of felony convictions. In

addition to serving as co-counsel in Hayden. CSS, along with other civil rights

organizations, was instrumental in changing New York State policies for re

integrating eligible persons with felony convictions to the voting rolls.

The Center for Law and Social Justice (CLSJ) is a unit in the School of

Continuing Education and Community Programs at Medgar Evers College of the City

University of New York. Founded in 1985, CLSJ’s mission is to be a resource for the

liberation of people of African descent in order to achieve equitable distribution of

wealth and resources, as well as cultural, economic, political, and social equity. CLSJ

2

seeks to achieve its mission through research, education, advocacy and litigation

projects. CLSJ is widely recognized as one of the few community-based

organizations in New York City that is actively committed to ensuring the voting

rights of Black people, including incarcerated and formerly incarcerated persons.

CLSJ s work has been pivotal in protecting the right to vote of communities of color

and in determining the City Council, State Assembly and Senate, and U.S.

Congressional districts in New York City. In addition to serving as co-counsel in

Hayden, CLSJ was counsel to intervening Black voters residing in the three New York

counties covered by Section 5 of the VRA in Rodnouez v. Pataki 308 F. Supp. 2d 346

(S.D.N.Y. 2004), affd , 125 S. Ct. 627 (2004).

BACKGROUND

Whether Section 2 of the VRA, as amended, applies to felon disfranchisement

laws is a question that will shape the modem civil rights struggle to ensure equal

access to the franchise for all Americans. The Court’s resolution of this question not

only has direct bearing upon this case, but will be germane to the resolution of at least

three other felon disfranchisement cases currently before federal courts — Johnson

3

- - Bush, Farrakhan v. Washington.3 and Hayden4 — as well as to the development

of Section 2 jurisprudence in general.

In Johnson, a challenge to Florida’s permanent disfranchisement of individuals

with felony convictions who have completed their sentences, the Eleventh Circuit

vacated for reconsideration en banc a panel decision reversing a lower court decision

holding that Section 2 applies to felon disfranchisement laws. In Farrakhan. the Ninth

Circuit upheld the application of Section 2 to felon disfranchisement laws. Farrakhan

w Washington, 338 F.3d 1009, 1019-20 (9th Cir. 1003), cert denied. ___U .S .___ ,

125 S. Ct. 477 (2004). The Supreme Court denied a petition for certiorari and

remanded the case for further proceedings.

Finally, Hayden, a challenge to New York State’s felon disfranchisement laws

on behalf of Blacks and Latinos who are incarcerated or on parole for a felony

conviction, is pending on appeal before this Court from a dismissal on the pleadings.

The Hayden pleadings describe the pervasive history of discrimination that motivated

the enactment of New York’s felon disfranchisement laws. Moreover, the Havden

pleadings set forth the disparate impact of felon disfranchisement laws on New York

4

353 F.3d 1287 (11th Cir. 2003).

No. CS-96-76-RHW (E.D. Wash.).

See supra n . l .

4

State’s Black and Latino communities. Consideration of the Havden plaintiffs’ vote

denial and vote dilution claims under Section 2 was explicitly reserved on appeal,

pending the outcome of the instant case.

INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT

The resolution of the issues raised in this appeal will reflect this country’s

commitment to democracy and the eradication of racially discriminatory practices in

the electoral process. This Court will decide whether voting eligibility requirements

namely felon disfranchisement laws — that disparately impact racial minorities

may be challenged under legislation specifically enacted to rid this country of

discrimination in the electoral arena.5 As a threshold matter, Amici submit that the

VRA unequivocally applies to felon disfranchisement laws such as N.Y Elect. Law

§5-106 (hereinafter “§5-106”). Moreover, Amici assert that Congress’ power to

legislate against such practices where they yield racially disparate results is firmly

grounded in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the United States

Constitution. For purposes of this brief, however, we focus upon the specific

According to a 2005 report by the Sentencing Project, 4.7 million, or one in

forty-three adults, have currently or permanently lost their voting rights because of

felony convictions. Of that number, 1.4 million or 13 percent are Black men, a rate

seven times the national average. Given current rates of incarceration, three in ten of

the next generation of Black men can expect to be disfranchised at some point in their

lifetime an eventuality that, if allowed to occur, places Black people’s right to vote

and to elect representatives of their choice on a path to extinction.

5

questions posed by this Court in its order granting rehearing en banc regarding the

nature and quantum of proof required to support a challenge to felon disfranchisement

laws under Section 2 of the VRA (Court’s En Banc Question No. 3).

Like other Section 2 challenges, claims regarding the racially disparate impact

of felon disfranchisement laws — whether in the context of vote dilution or vote

denial are governed by the totality of the circumstances test articulated in Section

2 jurisprudence since the 1982 amendments to the VRA. Once the disparate impact

of a voting practice, procedure or qualification is established, the totality of the

circumstances test requires courts to consider various external and contextual factors

that interact with the electoral mechanism at issue. The most salient of these factors

in a felon disfranchisement challenge is the extent to which racial bias in the criminal

justice system interacts with the disfranchisement law to create the racially disparate

impact. Like any other factor considered within the totality of the circumstances, bias

in the criminal justice system is not measured through a qualitative or quantitative

formula, but rather involves a probing assessment of the nature, magnitude, and extent

of the bias, along with consideration of other relevant factors.

As demonstrated below, there are several objective measures of bias within the

criminal justice system in New York State, some of which have been analyzed in

governmental reports and data. Plaintiff should be allowed an opportunity to marshal

6

such evidence and have it weighed by the district court as part of the totality of the

circumstances analysis prescribed by the law of this Circuit and Section 2

jurisprudence generally. We, therefore, urge the Court not only to affirm the breadth

of the protections afforded by Section 2, but to establish a flexible standard by which

to guide future felon disfranchisement jurisprudence.

ARGUMENT

I. Proof Required to Establish A Violation of Section 2 of the VRA (Court’s

En Banc Question No. 3)

In its order granting rehearing en banc, this Court posed specific questions

about the proof required to support a felon disfranchisement challenge under Section

2 of the VRA. While these questions are framed in the context of vote dilution, they

are equally relevant to an evaluation of Plaintiff s vote denial claim, which is the only

claim being pursued in his en banc appeal.6 Indeed, the totality of the circumstances

Brief for Plaintiff-Appellant jn Banc at 3. As described above. Amici represent

plaintiffs in Hayden, a felon disfranchisement challenge currently on appeal before

this Court, which raises, inter aha, a vote dilution claim under the VRA. The vote

dilution claim, which specifically challenges the erosive effects of §5-106 on the

voting strength of Black and Latino communities, is brought on behalf of Black and

Latino registered voters in those communities. These individuals undeniably have

standing to pursue a vote dilution claim under Section 2 of the VRA given their

allegation that §5-106 denies them an equal opportunity to participate in the political

process in New York State because of the disproportionate disfranchisement of Blacks

and Latinos under the statute.

Because the vote dilution claim is no longer before the Court in the instant

matter, Amici respectfully submit that any decision rendered by this Court should

7

analysis required under Section 2 applies to both vote denial and vote dilution claims,

although, as discussed below, the factors most relevant to the inquiry will depend on

the electoral procedure at issue, the specific facts of the case, and the nature of the

violation.

A. Disparate Impact of N.Y. Elect. Law §5-106

As an initial matter, Section 2 s application is triggered upon sufficient

allegations of disparate impact, and relief under the statute is appropriate upon a

showing that the electoral mechanism at issue is either intentionally discriminatory or

has a discriminatory result on account of race. See 42 U.S.C. § 1973(a). In the instant

case, Plaintiff has alleged facts and statistical evidence of the racially disparate impact

of §5-106 sufficient to trigger application of the “results” test of Section 2.

The racially disparate impact of §5-106 is starkly demonstrated by the fact that

a staggering 80 ̂ or more of the persons denied the right to vote under the statute are

Black or Latino. Blacks comprise over 50% of the disfranchised population in New

York State and Latinos comprise approximately 30% of the same, despite the fact that,

collectively, Blacks and Latinos comprise only 31% of the state population. These

numerical truths demonstrate beyond cavil the disparate impact of §5-106.

B. Totality of the Circumstances Test

reserve for further inquiry whether a vote dilution claim may be pursued under the

8

Section 2 of the VRA prohibits the use of any “voting qualification or

prerequisite to voting or standard, practice, or procedure . . . which results in a denial

or abridgement of the right of any citizen of the United States to vote on account of

race or color.” 42 U.S.C. § 1973(a). The statute expressly requires courts to assess

the “totality of the circumstances,” 42 U.S.C. § 1973(b), to determine whether “a

certain electoral law, practice, or structure interacts with social and historical

conditions to cause an inequality in the opportunities enjoyed by black and white

voters to elect their preferred representatives.” Thornburg v. Gjngles 478 U.S. 30,

47 (1986); see also Johnson v. DeGrandv 512 U.S. 997, 1010 n.9 (1994). This

totality of circumstances analysis applies to both vote denial and dilution claims. 42

U.S.C. § 1973; S. Rep. No. 97-417, at 30 (1982), reprinted in 1992 U.S.C.A.N.N. 177,

179 (hereinafter “S. Rep.”) (“Section 2 remains the major statutory prohibition of all

voting rights discrimination”); Gingles, 478 U.S. at 42-46; Burton v. City o f R P11P

Glade, 178 F.3d 1175, 1197-98 ( 11th Cir. 1999); Farrakhan. 338 F.3d at 1015 n.l 1.

The Senate Judiciary Committee report (hereinafter “Senate Report”) lays out

a broad, non-exclusive list of factors that “typically may be relevant to a §2 claim” in

assessing whether a VRA violation has occurred (hereinafter “Senate factors”). Id

at 44; see S. Rep. at 28-29 (listing factors). However, the Supreme Court has

recognized that while the Senate factors provide guidance for a totality of

9

circumstances analysis, they are “neither comprehensive nor exhaustive.” Gingles.

478 U.S. at 45. Indeed, no particular or specific number of factors must be proven to

establish a Section 2 violation, id ; S. Rep. at 29, and courts are free to evaluate other

factors to determine whether a challenged electoral procedure violates Section 2. S.

Rep. at 207. The factors most relevant to the court’s analysis will depend on the

electoral procedure at issue, the nature of the claim, and the specific facts of the case.

See id at 206; see also Goosby v. Town Bd. of the Town ofHempsteaH 180 F.3d 476,

492 (2d Cir. 1999) (“[T]he ultimate conclusions about equality or inequality of

opportunity were intended by Congress to be judgments resting on comprehensive,

not limited, canvassing of relevant facts.”) (quoting Johnson. 512 U.S. at 1011).

Having put forth evidence of the significant disparate impact of §5-106,

Plaintiff may proffer additional evidence relevant to whether New York State’s felon

disfranchisement laws result in discrimination on account of race. One clearly

pertinent factor in this inquiry is evidence of racial disparities and bias in New York’s

criminal justice system. In addition, Plaintiff may show other evidence of official

discrimination that touches on the right of Blacks and Latinos who are incarcerated

or on parole for a felony conviction to participate in New York’s political process,

including, inter aha, evidence of intentional discrimination in the enactment of New

York’s felon disfranchisement statute; evidence of the effects of discrimination in the

10

areas of education, employment, health, and housing; and evidence of the tenuousness

of the felon disfranchisement statute to any legitimate State policy. Consistent with

the flexible approach mandated by Section 2, however, none of these factors is singly

dispositive, and the weight given to each is measured by its relevance to Plaintiffs

claim.7

i. Evidence of Discrimination in the Criminal Justice System

a- l ype of Evidence (Court’s En Banc Question No 3(a))

Proof of racially disparate outcomes in the underlying criminal justice system

is indispensable to the totality of circumstances analysis and a successful felon

disfranchisement challenge under the VRA. However, no court has yet explicitly

addressed the types and quantum of evidence necessary to establish that racial bias in

a criminal justice system operates to deny an equal opportunity to vote in Section 2

challenges to felon disfranchisement laws.

Evidence of racial disparities in New York’s criminal justice system that

contribute to §5-106’s racially disparate impact fits squarely within the analysis of

the Senate factors. For example, the Senate Report expressly notes the relevance of

While the totality of circumstances test applies equally to vote denial and vote

dilution claims, the factors relevant to the court’s analysis may vary depending on

which type of claim is at issue and the specific facts involved. Amici thus propose a

standard for a vote denial challenge to felon disfranchisement laws consistent with

Section 2 jurisprudence.

11

the extent to which members of the minority group in the state or political

subdivision bear the effects of discrimination in such areas as education, employment

and health, which hinder their ability to participate effectively in the political

process.” S. Rep. at 29. This factor clearly contemplates proof of discrimination in

a variety of areas to the extent that such discrimination limits equal opportunity to

participate in the political process. See Farrakhan. 338 F.3d at 1020.

Indeed, in Farrakhan, the Ninth Circuit held that the totality of circumstances

test “requires the court to consider the way in which the disfranchisement law interacts

with racial bias in Washington’s criminal justice system to deny minorities an equal

opportunity to participate in the state’s political process.” 338 F.3d at 1014 (emphasis

added). The court held that “a causal connection may be shown where the

discriminatory impact of a challenged voting practice is attributable to racial

discrimination in the surrounding social and historical circumstances.” Id at 1019.

The racially discriminatory evidence that the lower court in Farrakhan found

“compelling,” id at 1020, consisted of statistical evidence regarding disparities in

arrest, bail and pre-trial release rates, charging decisions, and sentencing outcomes.

Id at 1013.8

8

In the instant case, the Court’s prior panel decision recognized that racial

disparities m sentencing in New York were at the heart of Plaintiff s allegations that

§5-106 discriminated against Blacks and Latinos. Muntaqim v. Coomhe 366 F.3d

102, 105 n.3 (2d Cir. 2004). Moreover, in the second appeal of Baker v. Pataki this

12

To this end, the extent to which race, ethnicity and sentencing are correlated is

a relevant consideration. In 2000 the U.S. Department of Justice sponsored a major

national review of the research addressing race and sentencing that included 32 studies

of sentencing decisions in state courts and 8 studies at the federal court level using

data from the 1980s and 1990s. These studies revealed that race and ethnicity are

strong determinants in sentencing.9

While Plaintiff should have the benefit of full discovery on remand, a number

of prominent and well-known studies have analyzed the racial bias prevalent in New

York’s criminal justice system with respect to some of these factors. For example, the

1991 report of the New York State Judicial Commission on Minorities10 cited a report

Court was prepared to remand the case for further factual development on the strength

of allegations regarding, inter aha, the racial composition of the prison population and

racially discriminatory sentencing in the courts. 58 F.3d 814 816 (2d Cir 1995)

vacated in part, 1996 U.S. App. LEXIS 13133 (2d Cir. 1996); see also Baker v Pataki’

85 F.3d 919, 934-35 (2d Cir. 1996) (Feinberg, J.).

Cassia Spohn, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Thirty Years of Sentencing Reform- The

Quest for a Racially Neutral Sentencing Process. 3 Crim. J. 427,444-450,475 (2000),

^ d a b l e at http://www.ncjrs.org/cnminaljustice2000/vol_3/03i.pdf (hereinafter

Spohn Review”). Three of the studies reviewed investigated sentencing decisions

by New York State courts. \ j l at 444-450; accord Tushar Kansal, The Sentencing

ProJect’ Eacial Dispantv in Sentencing: A Review of the Literaturr fr available at

http://www.sentencingproject.org/pdfs/dispanty.pdf (Jan. 2005) (“The most recent

generation of evidence suggests that while racial dynamics have changed over time,

race still exerts an undeniable presence in the sentencing process.”).

New York State Judicial Commission on the Courts, Repon of the New York

State Judicial Commission on Minorities. Volume Two: The Public and the CrmrtQ

13

http://www.ncjrs.org/cnminaljustice2000/vol_3/03i.pdf

http://www.sentencingproject.org/pdfs/dispanty.pdf

on bail disparities, which concluded that “race was found to affect both the decision

to release the defendant on bail and the amount of bail offered.”11 The Commission

also cited the New York State Committee on Sentencing Guidelines’s report

documenting significant differences in sentencing that turned on race.12 Each of these

reports firmly suggests that there is evidence of racial bias in many areas of the

criminal justice system that adversely impacts Blacks and Latinos.

Moreover, in 1995 the New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services

issued an empirical study of nearly 300,000 adult felony arrests addressing a number

of factors that resulted in the disproportionate representation of Blacks and Latinos

in New York State prison.13 Specifically, this report found: (1) statistically significant

differentials in detention rates for minorities and whites;14 (2) that minorities were

sentenced to prison more often than comparably situated whites;15 * and (3) that whites

139-177 (Apr. 1991).

14 at 142 (citing Nagel, The Legal/Extra-Leeal Controversy: Judicial Derisions

in Pretrial Release. 17 Law & Soc’y Rev. 481 (1983)).

14 at 164 (citing New York State Committee on Sentencing Guidelines, New

York State Sentencing Patterns: An Analysis of Disparity (1985)).

James Nelson, New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services,

Disparities in the Processing Felony Arrests in NYS. 1990-1997 MQQM (hereinafter

“Nelson Report”).

14 14 at vi.

13 14 at viii.

14

were sentenced to probation more than comparably situated minorities.16 Indeed,

statewide, for certain categories of defendants, one in five minority defendants

sentenced to prison would have been sentenced to a different sanction if they were

sentenced comparably to whites.17 Additionally, among certain probation-eligible

minority defendants, one in seven sentenced to prison in New York City and one in

three sentenced to pnson in the rest of the state would have been sentenced to a

different sanction if processed as similarly situated Whites.18 Relying on the Nelson

Report, the Franklin Williams Judicial Commission observed that “rampant racism

still infects our criminal justice system.”19

In 1999 the New York State Attorney General issued an historic report on stop

and frisk practices by the New York City police force which included a quantitative

analysis of nearly 175,000 “stops” in the City.20 * The data analyzed by the Attorney

General demonstrate that the decisions regarding stops in the City are marked by

racial disparities: Even when controlling for population and crime, the differences in

w Id at 27.

18 Id at 43.

The Franklin H. Williams Judicial Commission on Minorities, Equal Justice:

A Work in Progress, Five Year Report, 1991-1996 34 (1997).

Office of the Attorney General of the State of New York, Civil Rights Bureau,

The New York City Police Department’s “Stop & Frisk” Practices (1999)

15

stop rates for Blacks versus Whites and Latinos versus Whites remain statistically

significant. Blacks, who constitute only 25.6% of the City’s population, comprise

of all persons stopped” by the New York Police Department’s Street Crime

Unit.22

Indeed, even when it controlled for racial demographics, the Attorney General’s

report concluded that Blacks and Latinos are specifically targeted by the police in

areas where they comprise the smallest proportion of the population. In those

precincts, Blacks were stopped at a rate ten times greater than their percentage of the

overall population, and Latinos at a rate more than three times greater. Whites, by

contrast, were stopped at only half the rate of their population.23 Higher crime rates

in minority communities, as measured by race-specific arrest counts, also did not

explain why Blacks and Latinos are stopped at higher rates than Whites: “[A]fter

accounting for the effect of differing crime rates, Hispanics were ‘stopped’ 39% more

often than whites across crime categories. . . . [Bjlacks were ‘stopped’ 23% more

often than whites, across all crime categories.”24

Id at 121.

Id. at viii.

23 Id at 106.

Id. at ix-x.

16

Moreover, the breadth and depth of these empirical studies dwarf the sample

sizes in most national literature.25 Professor Jeffrey Fagan, Professor of Law and

Public Health at Columbia University, has used these data to study issues of mass

incarceration, policing, crime and health in New York City neighborhoods. In one

study,26 he examines “whether, after controlling for disorder, the city’s stop and frisk

policy is, in fact, a form of policing that disproportionately targets racial minorities”27 28

and found “little evidence to support claims that policing targeted places and signs of

physical disorder. Instead, “stops of citizens were more often concentrated in

minority neighborhoods characterized by poverty and social disadvantage.”29 As

Fagan notes, consistent with the findings of the Attorney General, when objective

measures of social disorder were analyzed, such as physical characteristics of

neighborhoods, stops had less to do with order-maintenance policing and more to do

with race and ethnicity.30 Accordingly, there is ample data that could be presented on

25 See Spohn Review, supra, at 444-452.

26 Jeffrey Fagan & Garth Davies, Street Stops and Broken Windows: Tprrv Rare

and Disorder in New York Citv. 28 Fordham Urb. L. J. 457, 458-462 (2000).

27 Id at 463.

28 Id

29 Id at 463-464.

30 Id at 489.

17

remand demonstrating that police practices in New York — the entry point to

prosecution in the criminal justice system — are racially biased.

The pattern of prosecution and incarceration in the City’s neighborhoods is

another relevant area of inquiry. Analyzing incarceration data in New York City in

five waves from 1985 to 1996, Fagan and his colleagues geocoded data on prison

admissions by the residential address of the incarcerated to show the spatial

concentration of incarceration.31 The study found that arrests and incarceration have

long been concentrated in only a few of the poorest neighborhoods, accounting for a

majority of New York’s prisoners and suggests that this concentration reflects a

correlation between race and policing.32 Moreover, the spatial concentration of

incarceration was independent of crime rates, including during a period from 1990 to

1996 when felony crimes declined by almost half across the City.33

These specific community impacts are so pervasive in minority neighborhoods

that Fagan characterizes them as endogenous or “grown from within, seeping into and

Jeffrey Fagan, Valerie West, and Jan Holland, Reciprocal F.ffects of Crime anH

Incarceration in New York City Neighborhoods. 30 Fordham Urb. L. J. 1551 (2003).

The sample in this study included 25% of all prison admissions and 5% of all jail

admissions in five waves, yielding annual samples of two to four thousand in the

former and three to four thousand in the latter. Id at 1567.

32 14

33 Id at 1569.

18

permanently staining the social and psychological fabric of neighborhood life in poor

communities in New York. 34 In the same vein, felon disfranchisement has an

identifiable community impact because of the excessive concentration of incarcerated

persons from predominantly Black and Latino neighborhoods who are ensnared by a

racially-flawed criminal justice system.

Thus, there is a significant body of research already available that provides a

substantial foundation for an analysis of Plaintiffs allegations concerning

discrimination in New York’s criminal justice system and its relation to §5-106’s

disparate impact on Blacks and Latinos. It is important to note that the studies that

have focused on sentencing outcomes (the Nelson Report and the research review by

Prof. Spohn, above) all control in some way for the seriousness of the offense and the

defendant s prior criminal history in order to assess how significantly race and

ethnicity factor into sentencing outcomes. The variables included in the important

work on policing practices (the Attorney General’s report and the report of Fagan, et

al., on stop and frisk practices) all control, at a minimum, for population and incidence

of crime to assess the significance of race and ethnicity in these discretionary

decisions by the police.

Id at 1589.

19

b- Quantum of Proof (Court’s En Banc Question No 3(b))

The appropriate quantum of proof of bias in the criminal justice system

sufficient to prevail under Section 2 in a felon disfranchisement challenge must be

grounded in the seminal case of Thornburg v. Gingles. and its progeny. These cases

have interpreted the amended Section 2 to create a results test that requires a searching

analysis of all relevant evidence concerning whether minority voters’ opportunity to

participate in the political process is effectively limited on the basis of race or

ethnicity.35

Although felon disfranchisement implicates issues related to criminal justice,

it is important to distinguish this civil challenge from the standards of proof required

in criminal proceedings and appeals. A vote denial plaintiff in a felon

disfranchisement challenge need not offer proof of discrimination in the criminal

justice system sufficient to overturn her criminal conviction or a sentencing decision.

To be sure, were Plaintiff challenging his conviction or sentence, he would have to

meet such standards and show ultimately that these decisions were made in

furtherance of a discriminatory purpose.36 This Section 2 challenge, however, is

35 Gingles. 478 U.S. at 62-63.

See McCleskey—v.—Kemp, 481 U.S. 279 (1987) (requiring proof of

discriminatory intent in an Equal Protection challenge to a death sentence); see also

U.S. v. Armstrong, 517 U.S. 456, 465 (1996) (summarizing case law requiring that

for selective prosecution claim, defendant must “demonstrate that the federal

20

simply not that case. Instead, Plaintiff asks this Court to examine the application of

a statute that unquestionably has a disparate impact to determine whether his right to

vote has been unlawfully denied. Success or failure on this claim will have no effect

on his conviction, the length of his sentence, or his chances for parole.

Section 2 jurisprudence also cautions against requiring the heightened

evidentiary standard of discriminatory intent used in criminal cases that focus on the

racial bias of the criminal justice apparatus. For example, under Gingles. evidence of

racially polarized voting is now a threshold evidentiary showing in all vote dilution

challenges to at-large electoral schemes. However, the plurality opinion in Gingles

rejected the proposition that racially polarized voting is present only when voting

behavior is caused by race, that is, when the race of Black voters is the determining

cause in their voting behavior and, conversely, when voting behavior by Whites is

explained primarily by their racial hostility to candidates preferred by Blacks.37

Instead, racially polarized voting is a function of patterns that are merely correlated

with the race of the voter:

[T]he reason why black and white voters vote differently is irrelevant to the

central inquiry of Section 2. . . . It is the difference between the choices made

prosecutorial policy . . was motivated by a discriminatory purpose’”).

37 Id at 63, 71-72.

21

by blacks and whites — not the reasons for that difference — that results in

blacks having less opportunity than whites to elect their preferred

representatives.38

The plurality in Gingles noted that requiring that racial intent or racial hostility be the

cause of racially polarized voting asks the wrong question under Section 2 and

converts the result standard Congress created into an intent standard that it sought to

undo.39

Similarly, Amici submit that the quantum of proof required in felon

disfranchisement challenges is a showing that race is significantly correlated to the

outcomes produced by the criminal justice system. For these reasons, this Court

should remand this case for further discovery with instructions to the district court to

re-open discovery and apply the totality of circumstances test to all of the evidence of

discrimination in the criminal justice system that may be marshaled by the Plaintiff,

in accordance with the mandates of Section 2.

c- Relevance of Evidence of Discrimination in Federal and

State Criminal Justice System (Court s En Banc Question

No. 3(c))

This Court’s query about whether to distinguish between the state and federal

criminal justice systems in weighing statistical and other evidence of racial

Id. at 63 (emphasis in original).

14 at 73. The Supreme Court has never disapproved the plurality’s approach.

22

discrimination should be answered in the negative. First, the factors contributing to

the discrimination in each system — including the existence of joint state and federal

policing task forces — are sufficiently commingled as to make any distinction

between the two systems irrelevant for purposes of Section 2’s totality of the

circumstances analysis. Moreover, it is clear that Section 2, as the “major statutory

prohibition of all voting rights discrimination,” 42 U.S.C. § 1973; S. Rep. at 30, was

enacted to stamp out racial discrimination in voting without regard to where it is

found.

II. Additional Senate Factors

In addition to evidence of discrimination in the criminal justice system, the

district court may consider other Senate factors in a Section 2 totality of the

circumstances analysis of felon disfranchisement laws. For example, the Senate factor

No. 5 is particularly relevant in this regard, as it considers the extent to which

members of the minority group in the state or political subdivision bear the effects of

discrimination in such areas as education, employment and health, which hinder their

ability to participate effectively in the political process.

A substantial body of evidence shows that Blacks and Latinos in New York

State and in New York City, in particular, bear the effects of discrimination in

education, health, housing and employment which hinder their ability to participate

23

in the political process. For example, Blacks and Latinos in New York City have been

found to be disadvantaged with respect to public education funding and, consequently,

denied a minimally adequate education.40

Government sponsored and scholarly reports have also found that Blacks and

Latinos in New York, especially in New York City, continue to suffer significant

disadvantages in housing, health, and public and private employment. See, e.g..

Manhattan Borough President’s Commission to Close the Health Divide, Closing The

Health Divide: What Government Can Do to Eliminate Health Disparities Am ong

Communities of Color in New York City (October 2004). In addition, a recent New

York City “disparity study” conducted under the supervision of Amicus CLSJ and the

DuBois-Bunche Center for Public Policy at Medgar Evers College for the New York

City Council identified statistically significant disparities between minority and white-

owned businesses in the City s award of prime contracts for construction, architecture

and engineering, professional services, standard services, and goods. See Mason

Tillman Associates, Ltd., Report: City of New York Disparity Study (December

See, Campaign for Fiscal Equity v. New York 7 1 Q N V S 9H47S (2002),

rev_d , 245 A.D.2d 1, 744 N.Y. S.2d 130 (1st Dept. 2002), a ff d in part and modified

mjiart, 100 N.Y.2d 893, 801 N.E.2d 326, 769 N.Y.S.2d 106 (2003) (holding that New

York State violated the state constitutional mandate to make available a “sound basic

education to all the children of the state by establishing an education financing

system that failed to afford New York City’s public school students, 84% of whom

are “racial minorities,” the opportunity for a meaningful high school education).

24

2004), available at http://www.nyccouncil.info/pdf_files/reports/citynyrpt.pdf.

Further, in 2003, according to a study undertaken by Amicus CSS, the citywide

unemployment rate for Blacks and Latinos was respectively 12.9 percent and 9.6

percent, as compared to 6.2 percent for Whites. Indeed, 50% of all Black males in that

year were unemployed. Mark Levitan, Community Service Society, A Crisis of Black

Male Employment: Unemployment and Joblessness in New York City 2003 2, 6

(2004). These disparities in educational and employment opportunities undoubtedly

contribute to the concentration of minority citizens in impoverished neighborhoods

which, as suggested above, become the focus of racially skewed police practices

leading to the dramatic impact of New York’s felon disfranchisement statute.

Moreover, Senate factor No. 9 concerns “[wjhether the policy underlying the

state or political subdivision’s use of such voting qualification, prerequisite to voting,

or standard, practice or procedure is tenuous.” Under the totality of circumstances

analysis, this Senate factor No. 9 would require a court to consider, among other

things, the extent to which felon disfranchisement serves an effective rehabilitative,

retributive, deterrent, and/or punitive function.

The above factors represent a relevant but not exhaustive list of factors for the

district court to consider in assessing whether felon disfranchisement results in

discrimination based on race.

25

http://www.nyccouncil.info/pdf_files/reports/citynyrpt.pdf

III. Evidence of Intentional Discrimination in the Enactment of New York’s

Felon Disfranchisement Laws

There is also considerable evidence that §5-106 was specifically enacted with

the intent to discriminate against Blacks. If presented below, that evidence should

also be considered under the totality of circumstances analysis by the court below on

remand.

As alleged in Hayden, the historical origins of New York’s felon

disfranchisement provisions are rooted in the Constitutional Convention of 1821__

a convention dominated by an express, racist purpose to deprive Blacks of the right

to vote. At that convention, the question of Black suffrage sparked heated debates,

during which delegates expressed their conviction that Blacks, as a “degraded” people,

and by virtue of their natural inferiority, were unequipped and unfit to participate in

the democratic process. Nathaniel Carter, William Stone and Marcus Gould, Reports

of the Proceedings and Debates of the Convention of 1821. at 198 (Albany: E. & E.

Hosford, 1821) (hereinafter “Debates of 1 8 2 1 One delegate to the 1821 convention

instructed his colleagues to “[ljook to your jails and penitentiaries. By whom are they

filled? By the very race, whom it is now proposed to cloth with power of deciding

upon your political rights.” Id at 191. Another delegate urged the other delegates to

[sjurvey your prisons your alms houses — your bridewells and your penitentiaries

and what a darkening host meets your eye! More than one-third of the convicts and

26

felons which those walls enclose, are of your sable population.” kb at 199.

Against this backdrop of racial hostility, the delegates to the 1821 convention

adopted a provision that permitted the legislature to exclude from the franchise those

“who have been, or may be, convicted of infamous crimes.” N. Y. Const. (1821), art.

II, § 2. As is made manifest by their own language, the delegates to the 1821

convention not only understood that enacting the felon disfranchisement provision

would result in the disproportionate disfranchisement of the “sable” or Black

population, but actively sought to preserve the franchise for Whites only: “[A]ll who

are not white ought to be excluded from political rights.” Debates of 1821. at 183.

Another delegate summed up the goals of the 1821 Constitutional Convention — to

exclude Blacks from “any footing of equality in the right of voting.” frL at 180.

Delegates to subsequent conventions continued to advocate for the denial of

equal suffrage rights to Blacks, including the 1846 Constitutional Convention, at

which one delegate pronounced that “[Blacks] were an inferior race to whites, and

would always remain so.” Constitutional Convention of 1846, Debates of 1846. at

1033 (hereinafter Debates of 1846 ). Moreover, the delegates were well aware of

and sought the same success as other slaveholding states in excluding Blacks from the

ballot. As one delegate suggested to the convention, “in nearly all the western and

southern states . . . the [Bjlacks are excluded . . . would it not be well to listen to the

27

decisive weight of precedents furnished in this case also?” Id at 181.

New York’s explicitly racially discriminatory suffrage requirements were

firmly in place until the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment, which sought to finally

bring equal manhood suffrage to New York. See U.S. Const, amend. XV. However,

two years after the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment, which New York attempted

to withdraw its ratification of, Cong. Globe, 41st Cong. 2d Sess., at 1447-81, an

unprecedented committee convened to amend the New York State Constitution’s

disfranchisement provision to require the State Legislature, at its following session,

to enact iaws excluding persons convicted of infamous crimes from the franchise. See

N Y- Const, art. II, § 2 (amended 1894). Until that point, enactment of such laws had

been permissive.

The corrosive effects of New York’s purposefully discriminatory felon

disfranchisement law still reverberate today in the incontrovertible disparate impact

of New York State Election Law § 5-106 on Blacks and Latinos. The pervasive

pattern of historical intentional discrimination against Blacks in voting in New York,

including repeated explicit statements by legislators about Blacks’ biological unfitness

for suffrage and, their perceived criminality, as well as the codification of mandatory

disfranchisement during an unprecedented special session at a time when overt denial

of the franchise to Blacks was newly outlawed by the Fifteenth Amendment provide

28

additional evidentiary support for a conclusion that Section 5-106 violates Section 2

of the VRA.

For the foregoing reasons, this Court should hold that Section 2 of the VRA can

constitutionally be applied to New York’s felon disfranchisement statute that results

m the denial of the nght to vote on account of race, and should reverse the district

court s grant of summary judgment with instructions to reopen discovery and evaluate

Plaintiff s claims within the totality of circumstances.

CONCLUSION

Respectfully submitted,

Theodore M. Shaw Juan Cartagena

Risa Kaufman

Community Service Society of N ew

York

105 E. 22nd Street

New York, New York 10010

(212) 260-6218

Director-Counsel

Norman J. Chachkin

Janai S. Nelson

Ryan P. Haygood

Alaina C. Beverly

N aacp Legal D efense & Educational

Fu n d , In c .

99 Hudson Street, Suite 1600

New York, New York 10013-2897

(212) 965-2200

Joan P. Gibbs

Esmeralda Simmons

Center for Law and Social Justice

at Medgar Evers College

1150 Carroll Street

Brooklyn, New York 11225

(718)270-6296

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

29

RULE 29(d) CERTIFICATE OF COMPLIANCE

The undersigned hereby certifies that this brief complies with the type-volume

limitations of Rule 32(a)(7)(B) of the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure. Relying

on the word count of the word processing system used to prepare this brief, I hereby

represent that the brief of the NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc.,

Community Service Society of New York, and the Center for Law and Social Justice

at Medgar Evers College for Plaintiff-Appellant contains 6,772 words, not including

the corporate disclosure statement, table of contents, table of authorities, and

certificates of counsel, and is, therefore, within the 7,000 word limit set forth under

Fed. R. App. P. 29(d).

Janai S. Nelson, Esq.

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, Suite 1600

New York, NY 10013

(212) 965-2237

jnelson@naacpldf.org

Dated: February 4, 2005

mailto:jnelson@naacpldf.org

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I certify under penalty of peijury pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1746 that, on

February 4, 2005,1 caused two true and correct copies of the foregoing En Banc

Brief in Support of Plaintiff-Appellant Jalil Abdul Muntaqim, a/k/a Anthony

Bottom, in Support of Reversal, on Behalf of Amici Curiae NAACP Legal Defense

& Educational Fund, Inc., Community Service Society of New York, and Center

for Law and Social Justice at Medgar Evers College, to be served via United States

Postal Service priority mail, postage prepaid, to the following attorneys:

Jonathan W. Rauchway Elliot Spitzer

1550 Seventeenth Street, Suite 500 New York, New York 10271-0332

Denver, Colorado 80202

William A. Bianco

Gale T. Miller

Davis, Graham & Stubbs, LLP

York

120 Broadway - 24th Floor

Attorney General fo r the State o f New

J. Peter Coll, Jr.

Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe,

LLP

666 5th Avenue

New York, New York 10013-0001 General

Appeals and Opinions Bureau

The Capitol

Albany, New York 12224

Julie M. Sheridan

Assistant Solicitor General

Daniel Smirlock

Deputy' Solicitor General

New Y ork State Office of the Attorney

Attorneys fo r Plaintiff-Appellant

Counsel for Defendants-Appellees

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, Suite 1600

New York, NY 10013

jnelson@naacpldf.org

mailto:jnelson@naacpldf.org