Dowell v. Oklahoma Board of Education Court Opinion

Public Court Documents

October 6, 1989

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Dowell v. Oklahoma Board of Education Court Opinion, 1989. 71e7161f-b09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1d354d6c-fda3-4f6d-9edd-0462dc41c72b/dowell-v-oklahoma-board-of-education-court-opinion. Accessed January 29, 2026.

Copied!

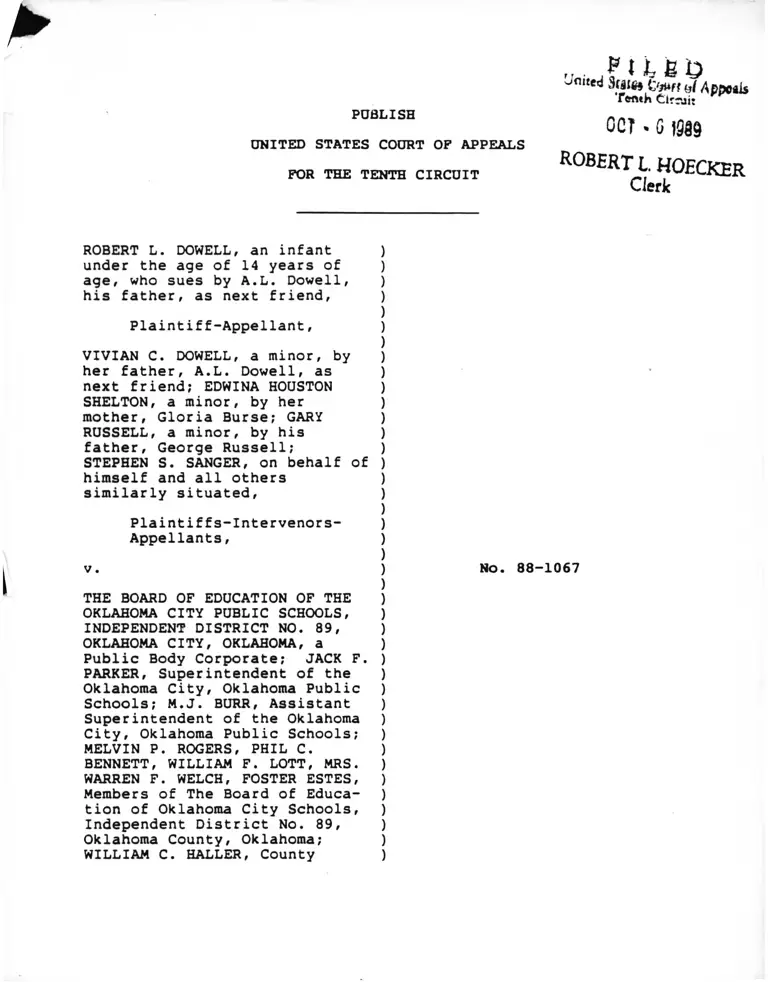

PUBLISH

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE TENTH CIRCUIT

rentn Circuit

O CT • S )989

ROBERT t. HOECKER

Clerk

ROBERT L. DOWELL, an infant )

under the age of 14 years of )

age, who sues by A.L. Dowell, )

his father, as next friend, )

)Plaintiff-Appellant, )

)VIVIAN C. DOWELL, a minor, by }

her father, A.L. Dowell, as )

next friend; EDWINA HOUSTON )

SHELTON, a minor, by her )

mother, Gloria Burse; GARY )

RUSSELL, a minor, by his )

father, George Russell; )

STEPHEN S. SANGER, on behalf of )

himself and all others )

similarly situated, )

)

Plaintiffs-Intervenors- )

Appellants, )

)

v. )

)

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE )

OKLAHOMA CITY PUBLIC SCHOOLS, )

INDEPENDENT DISTRICT NO. 89, )

OKLAHOMA CITY, OKLAHOMA, a )

Public Body Corporate; JACK F. )

PARKER, Superintendent of the )

Oklahoma City, Oklahoma Public )

Schools; M.J. BURR, Assistant )

Superintendent of the Oklahoma )

City, Oklahoma Public Schools; )

MELVIN P. ROGERS, PHIL C. )

BENNETT, WILLIAM F. LOTT, MRS. )

WARREN F. WELCH, FOSTER ESTES, )

Members of The Board of Educa- )

tion of Oklahoma City Schools, )

Independent District No. 89, )

Oklahoma County, Oklahoma; )

WILLIAM C. HALLER, County )

No. 88-1067

Superintendent of Schools of )

Oklahoma County, Oklahoma, )

)Defendants-Appellees, )

)JENNY MOTT McWILLIAMS, a minor, )

and DAVID JOHNSON McWILLIAMS, )

a minor, who sue by William )

Robert McWilliams, their father )

and next friend, on behalf of )

themselves and all others )

similarly situated; RENEE )

HENDRICKSON, a minor, BRADFORD )

HENDRICKSON, a minor, TERESA )

HENDRICKSON, a minor, and )

CINDY HENDRICKSON, a minor, who )

sue by Donna P. Hendrickson, )

as mother and next friend of )

each of said minors; and DONNA )

P. HENDRICKSON, Individually, )

and for themselves, and all )

others similarly situated, )

)

Defendants-Intervenors- )

Appellees, )

)DAVID WEBSTER VERITY, a minor, )

by and through his next friend, )

George L. Verity; GEORGE )

L. VERITY and ELLEN VERITY, )

for themselves and all others )

similarly situated; TAEJEMO )

DANZIE, a minor, by and through )

Mrs. A.J. Danzie, her next )

friend; and MRS. A.J. DANZIE, )

for themselves and all others )

similarly situated, )

)Intervenors. )

Appeal from the United States District Court

For the Western District of Oklahoma

D.C. No. CIV-61-9452-B

Norman J. Chachkin (Julius L. Chambers and Janell M. Byrd, New

York, New York; Lewis Barber, Jr. of Barber and Traviolia,

Oklahoma City, Oklahoma; and John W. Walker and Lazar M. Palnick

of John W. Walker, P.A., Little Rock, Arkansas, with him on the

briefs), New York, New York, for Appellants.

*

Ronald L. Day of Fenton, Fenton, Smith, Reneau & Moon, Oklahoma

City, Oklahoma, for Appellees.

Wm. Bradford Reynolds, Assistant Attorney General, David K. Flynn

and Mark L. Gross, Attorneys, Department of Justice, on the briefs

for the United States as Amicus Curiae.

Before SEYMOUR, MOORE, and BALDOCK, Circuit Judges.

MOORE, Circuit Judge.

-3-

*

Since its genesis, this litigation has sought to eradicate

the effects of an official policy of racial segregation in the

public schools of Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, and assure that each

child enrolled in an Oklahoma City school enjoys the same right to

a public education. We are now at a crossroad in the substantive

and procedural life of this case and must decide whether, after

our last remand, the district court followed the correct path,

terminating its prior decree and finding a new student assignment

plan implemented under that decree constitutional. Dowell v.

Board of Educ. of Okla. City Pub. Schools, 677 F. Supp. 1503

(W.D. Okla. 1987). We approach this case not so much as one

dealing with desegregation, but as one dealing with the proper

application of the federal law on injunctive remedies. We believe

that the law in this area is unambiguous, and simply because the

roots of the matter lie in school desegregation, there is no

reason to depart from the longstanding principles which form the

structure of that law. Upon our review, we conclude the trial

court did not follow the proper path and reverse the judgment

dissolving the 1972 injunctive decree. We remand the case for

modification of the decree consistent with this order. I.

I. Background

We have previously summarized the history of this case,

Dowell v. Board of Educ. of Okla. City, 795 F.2d 1516, 1517, n.l

(10th Cir.), cert. denied, 479 U.S. 938 (1986), tracing its

metamorphosis from filing in 1961 to the generation of an

equitable remedy in 1972. Dowell v. Board of Educ. of Okla. City

-4-

Pub. Schools, 338 F. Supp. 1256 (W.D. Okla. 1972). m 1986, when

last before us, plaintiffs urged review of the distrlot court's

refusal to reopen the case to consider their petition for

enforcement of the court's prior injunctive decree. The motion to

reopen was triggered by the implementation of a new student

assignment plan in 1984.

Until that time, defendants, the Board of Education of the

Oklahoma City Public Schools, school officials, and individual

board members, (the Board or defendants) operated the Oklahoma

City School District (the District) under tha Finger Plan, a court

ordered desegregation plan prepared by Dr. John A. Finger, Jr., a

Professor of Education at Rhode Island College and authority on

issues of school desegregation.1 Under the Finger Plan,

attendance zones were redesigned so that high schools and middle

schools enrolled black and white students. Black elementary

students in grades 1 through 4 were bused to previously all white

elementary schools while majority black elementary schools were

converted into 5th-year centers with enhanced curricula. Black

fifth graders then attended the 5th-year center in their

neighborhood, while white fifth graders were bused for the first

time into black neighborhoods to attend class. Excepted from the

Finger Plan were certain schools enrolling grades K-5, which were

designated -stand alone.- These schools were located in

neighborhoods that were racially balanced. Kindergarten children

attended their neighborhood elementary school unless their parents *

The Finger Plan was adopted only after th^ nna.j f ,

produce an acceptable desegregation plan to the district court. °

chose to send them to another school to join a sibling or be

closer to the parent's workplace. Aside from minor alterations

necessitated, for example, by a school's closing, the Board

maintained the District under the Finger Plan's basic techniques

of pairing, clustering, and compulsory busing, even after the

district court declared the District unitary and terminated the

case. Dowell v. School Bd. of Okla. City Pub. Schools, No. CIV-

9452, slip op. (W.D. Okla. Jan. 18, 1977).

Seven years later, the Board adopted a new student

assignment plan, the Student Reassignment Plan, (the Plan), which

was implemented for the 1984-85 school year. The Plan eliminated

compulsory busing in grades 1 through 4 and reassigned elementary

students to their neighborhood schools. A "majority to minority"

transfer option (M & M) was retained to permit elementary students

assigned to a school in which they were in the majority race to

transfer to one in which the student would be in the minority.

Fifth-year centers would remain throughout the District and, like

the middle schools and high schools, would continue to maintain

racial balance through busing. The Plan created the position of

an "equity officer" assisted by an equity committee to monitor all

schools to insure the equality of facilities, equipment, supplies,

books, and instructors. Dowell v. Board of Educ. of Okla. City

Pub. Schools, 606 F. Supp. 1548, 1552 (W.D. Okla. 1985). The Plan

professed to maintain integrated teaching staffs in line with the

District's affirmative action goal. As a consequence of the Plan,

eleven of the District's sixty-four elementary schools enrolled

-6-

90*t black children. Twenty-one elementary schools2 became 90*.

white and non-black minorities.2 Thirty-two elementary schools

remained racially mixed.

in February 1985, plaintiffs filed a motion to intervene and

reopen the case claiming the Board unilaterally abandoned the

Finger Plan. Although the record indicated the subsequent hearing

was limited to "the question of whether this case shall be

reopened and the applicants allowed to intervene shall be tried

and disposed of," Dowell, 795 F.2d at 1523 (emphasis omitted), the

district court received evidence on the constitutionality of the

Plan and disposed of all of the substantive issues defendants

raised. The district court concluded the Plan was constitutional

and found no special circumstances justifying relief under

Fed. R. Civ. P. 60(b) to support reopening. Dowell. 606 F. supp.

at 1557.

We reversed, holding the court abused its discretion in

failing to reopen the case and prematurely reached the merits of

the Plan's constitutionality without permitting plaintiffs the

opportunity to support their petition for enforcement of the

mandatory injunction which the court had never dissolved or

modified. Dowell, 795 F.2d at 1523. Key to our disposition was

the reassertion of the parties' burden of proof under

»ith less than

3In Oklahoma City,

the non-black minor Indian, Spanish, and Oriental ity population counted. children comprise

-7-

Fed. R. Civ. P. 60(b).4 We stated that on remand, the plaintiffs,

beneficiaries of the original injunction, only have the burden of

showing the court's mandatory order has been violated. The

defendants, who essentially claim that the injunction should be

amended to accommodate neighborhood elementary schools, must

present evidence that changed conditions require modification or

that the facts or law no longer require the enforcement of the

[1972] order." Id. (citation omitted) (emphasis added). Nothing

in this disposition touched on the underlying constitutional

issues. "[G]ur holding should not be construed as addressing,

even implicitly, the ultimate issue of the constitutionality of

the defendants' new school attendance plan." Id. at 1523. Remand

was confined to a determination of "whether the original mandatory

order will be enforced or whether and to what extent it should be

modified." Id.5

During the eight-day hearing on these remand instructions,

defendants6 introduced a golconda of testimony and exhibits to

establish their position that substantial demographic changes in

4Fed. R. Civ. P. 60(b) states:

On motion and upon such terms as just, the court may

relieve a party or a party's legal representative from a

final judgment, order, or proceeding . . . .

5The dissent takes several opportunities to disagree with this

unreversed holding. Nonetheless, it is the directive with which

this court remanded the case, and the trial court was not free to

depart from our mandate. Moreover, the holding is the present law

of this circuit.

6Although the stipulation was not found in the pretrial order, we

presume the parties agreed the injunction had been violated

because defendants presented their evidence of substantial change

first.

-8-

the District rendered the Finger Plan inequitable and oppressive.

The inequity, the Board maintained, surfaced primarily in the

burgeoning number of schools that qualified for stand-alone

status, thus necessitating that black children be transported

greater distances to attend racially balanced elementary schools.

Defendants' expert. Dr. william A. Clark, a specialist in

population geography, testified on the migration and mobility of

the black population in the District. Dr. Clark was satisfied

that the residential pattern that developed in the District since

the implementation of the Finger Plan was not a vestige of what

had occurred thirty-five or forty years before and that "black

preference" accounted for the dispersal of the black population

throughout the District. While recognising that socioeconomic

factors must be considered in any housing decision. Dr. Clark

maintained that the most significant motivation was preference.

Dr. Finis Welch, an economist at the University of

California, offered testimony on studies he conducted of the

dissimilarity and exposure indices of residential areas on which

the Plan was based. Dr. Welch opined that the increasing number

of stand-alones would "draw down" the Sth-year centers which, he

projected, would result in closing more schools in the northeast

quadrant, the area of central Oklahoma City which remains majority

black.

Three Board members testified about their involvement in the

preparation of the Plan. The District's superintendent, several

black school administrators, and various members of the community

offered their views on an array of issues, from linking

-9-

neighborhood schools to black achievement, to the value of

parental involvement in a child's education. Ms. Susan Hermes, a

member of the committee which prepared the Plan, stated that she

believed "educationally it is better for a child to have family

nearby." (R. IV, 390). Over plaintiffs' objection, counsel for

the Board asked each witness if he or she believed the District

remained unitary after implementation of the Plan. The court,

also over plaintiffs' objection, asked key defense witnesses if

the Plan was adopted with discriminatory intent.

Through cross-examination and in its presentation of

evidence, plaintiffs offered a contrasting analysis of the issues

of demographic change, the impact of the Plan, and the Board's

alternative approaches of the Effective Schools Program, increased

parental participation in PTA, and equity supervision. Dr. John

Finger, who had prepared the original plan, rejected each of these

features of the new Plan noting that Effective Schools and

increased parental participation deal with different problems and

cannot be substituted for a desegregated education. Dr. Gordon

Foster, a professor of education at the University of Miami,

testified about a student assignment plan he had prepared for

plaintiffs to solve the perceived inequities of busing under the

Finger Plan.

In its subsequent order, the district court initially

observed it was "now aware that it should have dissolved the

injunction in 1977, as pointed out in the Circuit opinion, because

the Oklahoma City schools were at that time, as they are today,

operating as a unitary system, wholly without discrimination to

-10-

Dowell, 677

F. Supp. at 1506. Nevertheless, the court apprehended the command

we framed in our prior review. "The fundamental issue the court

must address is whether the School Board has shown a substantial

change in conditions warranting dissolution or modification of the

1972 Order." Id. Relying on the testimony of Drs. Clark and

Welch, the court concluded:

[T]he Oklahoma City Board of Education has taken

absolutely no action which has caused or contributed to

the patterns of residential segregation which presently

exist in areas of Oklahoma City. If anything, the

actions of the Board of Education, through

implementation of the Finger Plan at all grade levels

for more than a decade, have fostered the neighborhood

integration which has occurred in Oklahoma City.

Id. at 1512.

Thus, unlinking the Board from existing residential

segregation and satisfied that demographic changes rendered the

Finger Plan inequitable,7 the court proceeded to examine the

constitutionality of the Plan. Acknowledging that "[a] once

unitary school district may lose its unitary status by partaking

in intentionally discriminatory acts creating de jure

segregation," id. at 1515, the court set forth the guidelines

established in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402

U.S. 1 (1971), and Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, Denver, Colo., 413

U.S. 189 (1973).

blacks or other minority students, faculty or staff."

7To reach this conclusion, the district court accepted defendants'

prediction that as new areas of the district qualified for "stand

alone" status, the distances which black students in grades 1-4

would have to be transported to attend integrated schools would

increase. Fifth-grade centers in the northeast quadrant would

then close because of the consequent diminished enrollment.

-11-

S o e ^ s y °i„b°lh the District Court and the Court of

s ^ = r aceasedy ^ r t C - T i"h‘*i =“*°°ls has^long

iSJrdCti°h-ih Chf conductr°f thiebSsinesseofetheheslhollBoard which [was] intended to, and did in fac

discriminate against minority pupils, teachers, or

Dayton Bd. of Educ. v. Brinkman. 433 U.S. 406, 420 (1977).

The court reviewed the evidence and concluded that not only

did legitimate nondiscriminatory factors motivate the adoption of

the Plan, but, also, that the Plan currently maintained a unitary

district which enjoyed increased parental and community

involvement and included safeguards such as the equity officer and

Effective Schools Program to insure continued unitariness. While

the court entertained plaintiffs* contention that the Plan did

have a disproportionate impact upon some blacks in the District,

it concluded that racial imbalance in the schools, without more,

does not violate the Constitution, citing Milliken v. Bradley. 433

U.S. 267 (1977). "it follows that a school board serving a

unitary school system is free to adopt a neighborhood school plan

so long as it does not act with discriminatory intent." Dowell,

677 F. Supp. at 1518. The court rejected plaintiffs' claim that

the Plan is a step toward a dual school system as "ludicrous and

absurd." Idi at 1524. In light of these findings of fact and

conclusions of law, the district court determined the Foster Plan,

plaintiffs' proposed modification of the 1972 decree, was neither

feasible nor necessary.

Plaintiffs appeal this order, contending essentially that the

district court misapplied the instructions on remand and

misperceived the function of the unitary status achieved in 1977

-12-

to be a post-decree change in circumstances warranting dissolution

of the injunction. In dissolving the injunction, plaintiffs urge

the court abused its discretion by relying on clearly erroneous

findings of fact.

II. Standard of Review

At the outset, we must underscore this case involves an

injunction upon which relief was sought pursuant to

Fed. R. Civ. P. 60(b). Dowell, 795 F.2d at 1522.® Thus, our

review focuses on whether the district court abused its discretion

in granting the Board's motion to dissolve the injunction and

denying plaintiffs' motion to modify the relief. On appeal we

will not disturb the district court's determination except for an

abuse of discretion. Securities and Exch. Comm'n v. Blinder,

Robinson & Co., Inc., 855 F.2d 677 (10th Cir. 1988). The district

court's exercise of discretion, however, must be tethered to legal

principles and substantial facts in the record. Evans v.

Buchanan, 582 F.2d 750, 760 (3d Cir. 1978), cert, denied, 446 U.S.

923 (1980). "[D]iscretion imports not the court's inclination,

but . . . its judgment; and its judgment is to be guided by sound

legal principles.'' Franks v. Bowman Trans. Co., 424 U.S. 747, 770-

71 (1976) (citation omitted).

®The dissent takes the position that because this case involves

the desegregation of a public school system, the usual standards

applicable to federal law on injunctive remedies are inapposite.

The Supreme Court has said, "However, a school desegregation case

does not differ fundamentally from other cases involving the

framing of equitable remedies to repair the denial of a

constitutional right." Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburq Bd. of

Educ., 402 U.S. 1, 16 (1971).

-13-

III. Standard for Modification

While a court's equitable power to fashion a remedy is broad

and its continuing duty to modify or vacate relief inheres to the

prospective nature of the relief,^ modification is subject to an

exacting standard from which this circuit has not wavered. See

Blinder, Robinson, 855 F.2d at 679; Equal Employment Opportunity

Comm'n v. Safeway Stores, Inc., 611 F.2d 795 (10th Cir. 1979),

cert, denied, 446 U.S. 952 (1980); Securities and Exch. Comm'n v.

Thermodynamics, Inc., 464 F.2d 457 (10th Cir. 1972), cert, denied,

410 U.S. 927 (1973) .

This standard, first articulated in United States v. Swift &

Co., 286 U.S. 106, 119 (1932), requires "[n]othing less than a

clear showing of grievous wrong evoked by new and unforeseen

conditions . . . to change what was decreed after years of

litigation with the consent of all concerned."9 10 The Court

cautioned;

There is need to keep in mind steadily the limits

of inquiry proper to the case before us. We are not

framing a decree. We are asking ourselves whether

anything has happened that will justify us now in

changing a decree. The injunction, whether right or

wrong, is not subject to impeachment in its application

to the conditions that existed at its making. We are

not at liberty to reverse under the guise of

9The Court stated in United States v. Swift & Co., 286 U.S. 106,

114 (1932), "A continuing decree of injunction directed to events

to come is subject always to adaptation as events may shape the

need."

10Although Swift involved a consent decree, the Court asserted the

same standards apply after litigation. Moreover, the Court

applies no distinction to requested modifications of decrees

sought by either plaintiffs or defendants. United States v.

Armour & Co., 402 U.S. 673, 681-82 (1971).

-14-

readjusting. Life is never static and the passing of a

decade has brought changes to the grocery business as it

has to every other. The inquiry for us is whether the

changes are so important that dangers, once substantial,

have become attenuated to a shadow.

Swift, 286 U.S. at 119 (emphasis added).

Hence, to pass muster under this test, the party seeking

relief from an injunctive decree "must demonstrate dramatic

changes in conditions unforeseen at the time of the decree that

both render the protections of the decree unnecessary to

effectuate the rights of the beneficiary and impose extreme and

unexpectedly oppressive hardships on the obligor." T. Jost, From

Swift to Stotts and Beyond: Modification of Injunctions in the

Federal Courts, 64 Tex. L. Rev. 1101, 1110 (1986). While the

Swift language may also support a modification when the original

purposes of the injunction are not fulfilled,^ the standard still

constricts the district court's inquiry.

Placed in other words, this means for us that

modification is only cautiously to be granted; that some

change is not enough; that the dangers which the decree

was meant to foreclose must almost have disappeared;

that hardship and oppression, extreme and unexpected,

are significant; and that the movants' task is to

provide close to an unanswerable case. To repeat:

caution, substantial change, unforeseenness, oppressive

hardship, and a clear showing are the requirements. *

i;L"Swift teaches that a decree may be changed upon an appropriate

showing, and it holds that it may not be changed in the interests

of the* defendants if the purposes of the litigation as

incorporated in the decree . . . have not been fully achieved."

United States v. United Shoe Mach. Corp., 391 U.S. 244, 248 (1968)

(government sought modification of injunction to achieve purposes

of original decree). See 11 C. Wright & A. Miller, Federal

Practice and Procedure S 2961, at 602-03 (1973).

-15-

Humble Oil & Ref. Co. v. American Oil Co., 405 F.2d 803, 813 (8th

Cir.), cert, denied, 395 U.S. 905 (1969). Fed. R. Civ. P. 60(b)

codifies this standard.

When the relief has been fashioned and the decree entered,

"an injunction takes on a life of its own and becomes an edict

quite independent of the law it is meant to effectuate." 64 Tex.

L. Rev. 1101, 1105. For this reason, the court's jurisdiction

extends beyond the termination of the wrongdoing, Battle v.

Anderson, 708 F.2d 1523, 1538 (10th Cir. 1983), because an

injunction seeks to stabilize a factual setting with a judicial

ordering and maintain that condition which the order sought to

create. The condition that eventuates as a function of the

injunction cannot alone become the basis for altering the decree

absent the Swift showing. Securities and Exch. Comm'n v. Jan-Dal

Oil & Gas, Inc., 433 F.2d 304 (10th Cir. 1970). To do otherwise

is to return the beneficiary of injunctive relief to the

proverbial first square. It is for this reason that Swift remains

viable.12

Thus, compliance alone cannot become the basis for modifying

or dissolving an injunction. United States v. W.T. Grant Co., 345

U.S. 629, 633 (1953); Jan-Dal Oil & Gas, Inc., 433 F.2d at 304.13

Nor can a mere change of conditions alter the prospective ordering

12It is noteworthy that the original Swift decree, affirmed in

1905, Swift & Co. v. United States, 196 U.S. 375 (1905), was

followed by a second decree in 1920 which was not dissolved until

198i.

13In Jan-Dal Oil & Gas, 433 F.2d at 306, we reversed the district

court1-! dissolution of a permanent injunction upon finding

defendant's proof established merely "short term compliance with

the law." Id.

-16-

of relationships embodied by a permanent injunction. The party

subject to the decree must establish by clear and convincing

evidence that conditions which led to the original decree no

longer exist, or the condition the order sought to alleviate, a

constitutional violation, has been eradicated.14 Until this

showing is made, the decree stands.

Nevertheless, a permanent injunction empowered by a court's

continuing jurisdiction does not presume that its underlying

circumstances or the rights achieved remain static. "By its

forward cast, an injunction contemplates change and must be

sufficiently malleable to adapt the ordered relief to contemporary

circumstances." United States v. Lawrence County School Dist.,

799 F.2d 1031, 1056 (5th Cir. 1986). Thus, while principles of

res judicata may be applied to the factual finding of unitariness

at the time the finding is made with the injunction in place, we

have recognized that this past finding alone does not bar

reconsideration of the decree. Dowell, 795 F.2d at 1519.

In contending there should be a different standard employed

in school desegregation cases, the dissent miscasts our basic

premise. We do not imply perpetual supervision of public schools

by federal courts, nor do we suggest the Board is incapable of

complying with constitutional mandates. We take the simple

position that an injunctive order entered in a school

desegregation case has the same attributes as any other injunctive

14Our case differs from Pasadena City Bd. of Educ. v. Spangler,

427 U.S. 424, 437-38 (1976), which found modification appropriate

because "no majority of any minority" provision in the 1974

injunction was "contrary to the intervening decision of this Court

in Swann."

-17-

order issued by a federal court, and that it is binding upon all

parties until modified by the court which entered the order in the

first instance. We add, as the trial court initially recognized,

the injunctive order can be modified or dissolved only upon a

finding of changed conditions. In this context, the intent of the

defendants has little, if any, relevance.

IV. Purpose of Injunctive Relief

In 1972, having found "the Defendant School Board has totally

defaulted in its acknowledged duty to come forward with an

acceptable plan of its own," Dowell, 338 F. Supp. at 1271, the

district court held that "[p ]laintiffs are entitled to a decree

requiring the reasonably immediate conversion of the Oklahoma City

Public Schools into a unitary school system." Id♦ at 1272

(citations omitted). The Board was ordered not to alter or

deviate from the plan without "the prior approval and permission

of the court," and the order was made binding on the Board, "its

members, agents, servants, employees, present and future, and upon

those persons in active concert or participation with them." Id.

at 1273.

The decree embodied the constitutional mandate to eliminate

"root and branch" racial discrimination enforced through a dual

school system. Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent County,

Va., 391 U.S. 430, 437 (1968). The resulting terrain

circumscribed by the injunction was later declared unitary upon

the district court's finding certain components of unitariness to

-18-

have been satisfied.“ "[U]nitariness is less a quantifiable

'moment' in the history of a remedial plan than it is the general

state of successful desegregation." Morgan v. Nucci, 831 F.2d

313, 321 (1st Cir. 1987); see also Brown v. Board of Educ. of

Topeka, (No. 87-1668).^ While a declaration of unitariness

addresses the goals of injunctive relief, it alone does not sweep

the slate clean.

Nor, in our view, does a finding of unitariness mandate the

later dissolution of the decree without proof of a substantial

change in the circumstances which led to issuance of that decree.

Dowell, 795 F.2d at 1521; contra United States v. Overton, 834

F.2d 1171 (5th Cir. 1987); Riddick v. School Bd. of Norfolk, 784

F.2d 521 (4th Cir.), cert, denied, 107 S. Ct. 420 (1986).17 Until

^While the Supreme Court has defined neither the meaning of the

term unitary nor the time and method of closing a school

desegregation case, the Court has suggested that the elimination

of "invidious racial distinctions" related to student assignment,

transportation, support personnel, and extracurricular activities,

and the school administration's concern for producing and

maintaining schools of like quality, facilities, and staffs meet a

threshold showing of unitariness. Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburq

Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S. 1, 18 (1971); see also Ross v. Houston

Indep. School Dist., 699 F.2d 218, 227-28 (5th Cir. 1983)

("Constructing a unitary school system does not require a racial

balance in all of the schools. What is required is that every

reasonable effort be made to eradicate segregation and its

insidious residue." (citations omitted)). Professor Fiss has

queried, "But what is a permissible basis for assigning students

to schools under a 'unitary nonracial school system'? This seems

to be the central riddle of the law of school desegregation."

Fiss, The Charlotte-Mecklenburg Case - Its Significance for

Northern School Deseqreqation, 38 U. Chi. L. Rev. 697, 700-01

(1971) .

16The Morgan court defined unitary status as "a fully integrated,

non-segregated system," 831 F.2d at 316, that is, complete

desegregation "in all aspects of the . . . schools." Id. at 318.

17The dissenting opinion, like that in Overton, 834 F.2d at 1171,

(Continued to next page.)

-19-

that showing, "those who are subject to the commands of an

injunctive order must obey those commands, notwithstanding

eminently reasonable and proper objections to the order, until it

is modified or reversed." Pasadena City Bd. of Educ. v. Spangler,

427 U.S. 424, 439 (1976). It is imperative that the rights of the

party for whose benefit an injunction has been entered are

affected by no one unless a court determines the injunction in

current form is no longer necessary to achieve the court's

original objective. It is also imperative that when considering

whether to vacate or modify an injunctive decree, the district

court not retry "the original premises of the judgment; instead,

any modification must be confined and tailored to the change in

circumstance that justifies the modification." Lawrence County

School Dist. , 799 F.2d at 1056. Necessarily, however, in

conducting a factual inquiry into the changed conditions pled, the

court must reexamine whether the underlying substantive

obligations are preserved. See B. Landsberg, The Desegregated

(Continued from prior page.)

confuses a trial court's jurisdiction to enforce its mandatory

orders with the concept of finality. We agree that a federal

district court should not attempt an interminable supervision over

the affairs of a school district. Recognizing the inherent power

to enforce prior orders, however, is not inconsistent with the

objective of curtailing active supervision. Once the school

district has achieved unitariness, the court's need for active

jurisdiction ceases. Its power to enforce its equitable remedy,

however, is born when the remedy is fashioned and does not die

until the remedy expires. By upholding this power, we are not

holding, as the dissent seems to suggest, that a district court

retain post- remedy authority over a school district for any

reason other than to enforce, modify, or vacate its decree. Thus,

the dissent's suggestion that we have added a new dimension to the

law by "retaining jurisdiction" over this case fails to recognize

we add nothing to the district court's jurisdiction that it did

not already possess.

-20-

School System and the Retrogression Plan, 48 La. L. Rev. 789

(1988) .* 18

V. Burden of Proof

A.

Nevertheless, in this case, unilaterally and without prior

approval from the district court, as required by the injunctive

decree, the Board implemented the Plan. It is uncontested that

the contents of the Plan are contrary to the explicit dictates of

the injunction. As we previously noted, the Board's action

creates a "special circumstance which permitted plaintiffs to

return to court and test the presumptions premised in the

declaration of unitariness." Dowell, 795 F.2d at 1522. We so

instructed the district court.

The first presumption we address, then, is whether the

Board's Plan maintains the unitary status of the District since

the injunction remained in effect when the Board restored

neighborhood schools for elementary student assignments.18 This

18Professor Landsberg correctly points out that this "core issue

of the substantive obligations of formerly de jure school systems

which have successfully desegregated" has been overlooked in the

judicial haste to restore school governance to local authority.

48 La. L. Rev. 789, 815 (1988). See also P. Gewirtz, Choice in

the Transition: School Desegregation and the Corrective Ideal, 86

Colum. L. Rev. 728 (1986).

18The dissent states: "Here, despite the school district's

continued unitary status, this court retains jurisdiction and now

orders the school district to racially balance the elementary

schools which most certainly will require busing." Dissent at

p.2. We are compelled to point out that the question of continued

unitariness of the District so readily assumed by the dissent was

the key factual controversy in this case. Moreover, both sides

(Continued to next page.)

-21-

presumption flows from the Board's continuing affirmative duty to

"accomplish desegregation," Swann, 402 U.S. at 42, to attain

"maximum practicable desegregation," Morgan v. McDonough, 689 F.2d

265, 280 (1st Cir. 1982), and to protect the constitutional rights

of the class protected by the equitable remedy. Keyes v. School

Dist. No. 1, Denver, Colo., 609 F. Supp. 1491, 1515 (D. Colo.

1985). The remedy "must survive beyond the procedural life of the

litigation." Dowell, 795 F.2d at 1521.

That thirty-two of the sixty-four elementary schools in

Oklahoma City emerge from the Plan as one-race majority schools

not only establishes a prima facie case that the decree has been

violated and the presumption of unitariness challenged, but also

satisfies plaintiffs' burden in reopening and shifts the burden to

defendants to produce evidence of changed circumstances or

oppressive hardship.

[I]n a system with a history of segregation the need for

remedial criteria of sufficient specificity to assure a

school authority's compliance with its constitutional

duty warrants a presumption against schools that are

substantially disproportionate in their racial

composition . . . The court should scrutinize such

schools, and the burden upon the school authorities will

be to satisfy the court that their racial composition is

not the result of present or past discriminatory action

on their part.

(Continued from prior page.)

recognized conditions had changed since the entry of the

injunctive order, thus clearly suggesting the incongruity between

those changed circumstances and the facts which convinced the

trial court the District was unitary. Whether the District was

unitary before circumstances changed is irrelevant to whether the

decree should be amended or vacated. Indeed, whether the District

remains unitary in light of changed circumstances is a wholly

different question. Finally, our focus is upon the issue of

desegregation. How that objective will be reached must be left

first to the Board's judgment, and we will not engage in

shibolethic speculation.

-22-

Swann, 402 U.S. at 26. The Board bears a "heavy burden" to show

that its implementation of the Plan does not "serve to perpetuate

or re-establish the dual school system." Dayton Bd. of Educ. v.

Brinkman, 443 U.S. 526, 538 (1979) (quoted in Clark v. Board of

Educ. of Little Rock School Dist., 705 F.2d 265, 271 (8th Cir.

1983)). This burden is not alleviated after a finding of

unitariness when the decree remains in place but is focused on the

Swift inquiry whether "anything has happened that will justify us

now in changing a decree." 286 U.S. at 119.

The Board sought to prove that substantial demographic change

in the District established new conditions that were unforeseen at

the time the decree was instituted and which now produced

"hardship so 'extreme and unexpected' as to make the decree

oppressive." Equal Employment Opportunity Comm'n v. Safeway, 611

F.2d at 800 (quoting Swift, 286 U.S. at 119). While the record

sets forth changed circumstances not unlike those contemplated by

Swann, it fails to establish "the dangers the decree was meant to

foreclose must almost have disappeared." Humble Oil & Ref. Co.,

405 F.2d at 813.

B.

In its factual findings, the district court relied on

relocation statistics offered by defendants' experts, Drs. Clark

and Welch. Although Dr. Clark's evidence indicated black families

had relocated within and outside of the District,^® he conceded

^Dr. Clark produced relocation statistics for black families with

(Continued to next page.)

-23-

that his examination focused only on seven inner-city tracts and

not on additional predominantly black residential tracts to the

north of the studied area. (R. II, 93-94). While Dr. Clark's

study establishes there is a substantial decrease in black

population in these particular tracts, it reveals the same

decrease for total population.* 21 Both on direct and cross-

examination, Dr. Clark stated that the area encompassing the seven

tracts underwent "land use transition," (R. II, 68) and that

construction of interstate highways, 1-40 and 1-35, and

developments in institutions, notably the hospital complex, had

"dramatic impact" on population movement in some of the studied

tracts. (R. II, 68).

Based on this testimony, the court concluded there was "a

substantial amount of turnover in the black population residing in

the east inner-city tracts." Dowell, 677 F. Supp. at 1507. This

conclusion is also premised on metropolitan census data compiled

from completion of a long census form. While the long census form

asks the respondent whether he or she lived in the same house five

years before, it does not determine whether the respondent moved

out of the District or merely down the street. The basis for the

(Continued from prior page.)

kindergarten children, 1974/75 to 1977/78, and black families with

children in three grade levels, 1982/83 to 1984/85. The results

are visualized in Def. Exs. 7 and 8.

21The court's order reproduced only the figures for black

population. Defendant Exhibit 5D, on which the court relied, also

represented "total population" figures for the studied tracts.

-24-

turnover22 * rate is thus incomplete, rendering the census form

suspect.22

Using census figures, Dr. Clark calculated that the

percentage of black population residing in these tracts in

Oklahoma City between 1960 and 1980 decreased by 67.2%. 24 25 Despite

his statement about external forces affecting population movement,

Dr. Clark concluded that "private preference" was the chief

motivating factor in determining where people chose to live. 3

(R. II, 113). Dr. Clark observed the "strong disinclination" of

whites to move into predominantly black neighborhoods and their

coincidental inclination to move out of neighborhoods that become

25 to 30% minority. (R. II, 105). He conceded that majority

black areas would then be unlikely to change unless the black

population moved elsewhere. (R. II, 106).

The district court thus observed, "Some blacks were choosing to

live within the area and others were choosing to move away. (Tr.

71)." 677 F. Supp. at 1507.

The district court also relied on the testimony of Dr. Welch

who presented statistical analyses of the racial composition of

22The district court noted that "turnover" refers to persons who

did not live in the same house five years previously.

22In Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, Denver, Colo., 609 F. Supp.

1491, 1508 (D. Colo. 1985), the district court rejected evidence

of demographic change based on the long census form because of its

omission of key information and incomplete sampling.

24"In 1960, 84% of all blacks residing in the Oklahoma City

metropolitan area lived within these tracts. In 1980, however,

only 16.8% of the total black population in the metropolitan area

lived in this area." 677 F. Supp. at 1507.

25Dr. Clark stated that his use of the term "preference" does not

preclude the element of prejudice. (R. II, 113).

-25-

residential attendance zones in the District from 1972 to 1986 and

then used these figures to project racial composition in 1995.

Based on Dr. Welch's calculations, the court noted that "the

exposure of blacks to non-blacks.almost doubled." 677 F. Supp. at

n c1508. Embracing Welch's analysis which included a ranking of

the 125 school districts he had studied, the court declared, "the

Oklahoma City school district experienced the eighth largest

reduction in the index of dissimilarity or, in other words, the

eighth greatest improvement in integration, during the period from

1968 to 1982 (Def. Ex. 27; Tr. 130-31)." 677 F. Supp. at 1508.26 27

The court noted that "[e]ven after implementing the K-4

neighborhood school plan, the degree of overall dissimilarity

among the races attending school in Oklahoma City was less than

that of Tulsa, Oklahoma, whose index was .557. (Def. Ex. 38)."

677 F. Supp. at 1508.® Similarly, the district court relied on a

26Dr. Welch utilizes the terms "dissimilarity index" and "exposure

index" to express these ratios. The former represents the

distribution of the races in an area, while the latter indicates

how well a school system is integrated based on the same two-group

comparison, whites and non-whites. He then postulates that a

dissimilarity index of .00 signifies a maximally integrated

population while an index of 1.0 represents a segregated

population. The exposure index reverses the ratio with .00

representing the most segregated population and 1.0 the most

integrated neighborhoods. Dr. Welch's study relied principally on

the dissimilarity index. "We do not use the exposure index very

intensively in the study." (R. II, 130).

27Dr. Welch stated on direct examination that the study of the

dissimilarity index used in this comparison included 1968 to 1982

and did not show the dissimilarity in the District after

implementation of the K-4 Plan in 1985. (R. II, 132). The

inevitable conclusion, then, is that the achievement of

integration in the District was the consequence of the adoption of

the Finger Plan.

2®Plaintiffs' objection to the admission of this comparison

(Continued to next page.)

-26-

comparison of the District figures following implementation of the

Plan with figures from other -unitary districts in the country -29

Noting the change in the dissimilarity index from .78 prior to

implementation of the Finger Plan to .24 in 1984, the district

court stated -the index rose slightly to .38- in 1985 with the

reproduction of neighborhood schools. 677 F. Supp. at 1509.

Contrary to the district court's characterization, the rise in the

represents a 58% increase in the ratio of blacks to non-

blacks. Despite this expansion of dissimilarity, the- court

concluded the “increased residential integration in Oklahoma city

has resulted in a much lower level of dissimilarity today in the

neighborhood elementary schools (.56) than existed in 1971 before

the Finger Plan was implemented (.83). (Def. Ex. 44; Tr. 187)."

677 F. Supp. at 1509.

on the basis of Def. Ex. 20. two graphs plotting enrollment

figures for the District for white, black, and non-black minority

students, grades K-12, the court concluded “the student body is

(Continued from prior page.)

"some school boards^e^esf attentive °t thaground U c°uld show attentive to the nrohTfm 5: ® to the Problem or more

Nevertheless, the court utilized^his* comn" • (R* IIX' 195-96).

evidence of the impact of the* Plan on aS substantive

dissimilarity among the races.- ?77 sSpp" St^fSS? °f "°Vera11

schoolC°UdistrictsySideclareded on.^e *̂ Ex* 39, a list of 117

Department press release. In resnon^t- ac^ordin<3 to a Justice

that he had not verified the list rR ttt DT a m WelCh'S statement to take judicial notice of ce*r\mi 1 * 280), the court agreed

NAACP v. Georgia. 775 mj ? ■ ?■'6, ?°nf ̂ ence °£ Branrhl* of

^Tiled the accuracy of pan of n s t ' ^ t ^ q u e s t ^ . ̂ ^ ’' Which

-27-

truly multi-cultural."3 ̂ 677 F. Supp. at 1509. Nevertheless, the

court acknowledged the Plan created "some schools," eleven, which

are 90%+ black but observed "the plan created no schools which are

90% or more white." Id. at 1510. The Plan, however, created

twenty-one schools that had less than 10% black student

enrollment.

The district court does not address contrasting evidence in

the record. Unmentioned by the court is plaintiffs' cross-

examination of Dr. Welch which produced testimony directly

controverting that of Dr. Clark30 31 and undermined the method

employed to create the figures the Board relied on to represent

substantial demographic change and the oppressiveness of the

decree. Noting that he used two different methods for calculating

the 1974 to 1986 figures and the 1986 to 1995 figures, Dr. Welch

conceded: "And I really didn't want an inconsistent forecast. I

thought someone would be cross-examining me. And so I designed

the procedure to be completely internally consistent." (R. Ill,

244). His numbers, he stated, were "guesstimates." (R. Ill,

246) .

In addition, the court does not reference the testimony of

Dr. Yale Rabin, plaintiffs' expert in population distribution.

Using U.S. Census data, Dr. Rabin compared and analysed the black

30In 1986, whites comprised 47%, blacks 40%, and non-black

minorities 13% of the District's enrollment.

31For example, on the basis of his calculations, Dr. Welch

projected the black population in the District for 1995. (Def. Ex.

11). The projection represented areas between 92.3% and 100%

black, becoming somewhere between 89.6% to 93.2% black. Dr. Welch

stated the projections suggest whites will move into the area. (R.

Ill, 252-53).

-28-

population in the District between 1950 and 1980. According to

these census tract figures, the black population expanded from one

tract in which approximately 25% of the District black population

resided, to sixteen tracts 75%+ black, including 60.8% of the

District's black population. He explained that as the area

expanded spatially from one tract in 1950 to six tracts in 1960,

thirteen tracts in 1970, and sixteen tracts in 1980, each

expansion included the original all-black tracts. (R. VII, 1125-

31). Dr. Rabin controverted Dr. Clark's conclusion that the black

population had dropped to 16.9% in 1980 in the six tracts. "[T]he

area of concentration itself has changed, and it's misleading to

refer, in each successive decade, to the same six tracts as the

area of concentration." (R. VII, 1133). Dr. Rabin not only

recognized the substantial population displacement caused by

institutional and highway development but focused the effect of

Def. Exs. 7 and 8, maps showing the numbers of black families and

general direction of movement in and out of the District. For

example, Dr. Rabin noted that while 46 families moved into white

areas from the northeast quadrant from 1974 to 1978 (Def. Ex. 7),

many thousands of blacks live in the subject tracts, thus putting

the significance of the turnover numbers into perspective. (R.

VII, 1157). In fact, the more predominant population shift, 148

families, was within the northeast quadrant.

Most importantly, Dr. John Finger, plaintiffs' expert,

underscored that the Board's statisticians had "changed the

rules." (R. VIII, 1207). He explained,

There will be no schools that have less than ten

percent minority, but there will be schools that have

-29-

II

less than ten percent black. How you label these as

segregated or not is what the words mean, and segregated

has always been a difficult word.

(R. VIII, 1208).

Permeating the testimony on demographic change were sharply

contrasting views on the impact of busing on children of "tender

age." 677 F. Supp. at 1526. Numerous lay witnesses and District

personnel testifying on behalf of the Board generally stated that

busing young children had an adverse, emotional impact on the

child.22 Defendants' expert witness, Dr. Herbert Walberg, a

research professor at the University of Illinois, offered a study

he completed showing that black children who were transported to

school tested lower than black children who did not ride a school

bus. Plaintiffs' witness, Dr. Robert Crain, who was qualified an

expert on school desegregation, stated that Walberg's study was

"absolutely indefensible" because it omitted critical covariant

factors like socioeconomic status in the analysis. (R. VII,

1008). Dr. Crain stated that in light of the fact that half of

all public school students ride a school bus and that only 5% of

those children are bused for desegregation purposes, the evidence

of the harmful effects of transportation on student achievement

22For example, counsel for the Board asked plaintiffs' expert, Dr.

Foster, if busing young children would be potentially more

difficult because "they're not fully developed." (R. VIII, 1367).

The court asked one witness if, in her opinion, K-4 children are

too young to be bused. (R. Ill, 338). Mrs. Clara Luper, a

teacher at John Marshall High School, stated that her daughter was

"excited about riding the bus." (R. IX, 1403). Testimony on

busing distances tended to be based on estimates of time and

mileage, not actual routing distance. See, e.g., R. V, 705.

-30-

and emotional development is suspect. The district court did not

reference plaintiffs' evidence on this issue.

C.

Based on the divergent testimony on demographic change, the

court concluded the Board had not taken action to cause or

contribute to presently existing residential segregation but "[i]f

anything, the action of the Board of Education, through

implementation of the Finger Plan at all grade levels for more

than a decade, have [sic] fostered the neighborhood integration

which has occurred in Oklahoma City.” 677 F. Supp. at 1512.

Previously, in summarizing the relocation statistics, the court

observed, "These relocation studies reveal the compulsory busing

of black children to a certain area does not have any appreciable

affect [sic] on where their parents choose to relocate. (Tr. 76-

77)." 677 F. Supp. at 1508.

That demographic change of some degree occurred within the

District after the Finger Plan was instituted is apparent. As

Swann observed, "It does not follow that the communities served by

such systems will remain demographically stable, for in a growing,

mobile society, few will do so." 402 U.S. at 31. Nevertheless,

we are reluctant to hitch the preservation of hard-won

constitutional rights to numbers alone. "Unitary status is not

simply a mathematical construction." Morgan, 831 F.2d at 321. As

the district court observed in Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1,

Denver, Colo., 609 F. Supp. at 1516, "The expert testimony in this

case concerning the use of racial balance and racial contact

-31-

j

indices, and the differing conclusions reached by the experts

called by the respective parties, demonstrate once again the

facility with which numerical data may be manipulated and

discriminatory policies may be masked.1' In Oklahoma City, the sum

total of all of the numbers immutably underscores the emergence of

eleven all-black elementary schools and twenty-one 90%+ white and

non-black minority schools, roughly half of the District's

elementary schools, with the reinstitution of neighborhood black

schools for the elementary grades. In fact, when the actual

numbers of children attending District elementary school are run,

the result is even more dramatic. Of the approximately 6,464

black students33 attending the District's elementary schools K-4,

2,990, or 46.2% of all black elementary children in the District

attend the eleven 90%+ black elementary schools.34

D.

Similarly, we are unable to conclude that these same

numerical calculations support a finding that the Finger Plan

became a hardship "extreme and unexpected," Humble Oil & Ref. Co.,

405 F.2d at 813, because of the unintended impact of the stand

alone schools. This hardship was projected to arise if a school

became stand-alone, necessitating busing black students, who had

33This total number includes the Star-Spencer area which was

already treated differently under the Finger Plan because of its

geographic separation from the District.

34These calculations are based on plaintiffs' Exhibit No. 26,

Membership by School, Race and Grade, K-4 Elementary Schools. The

District's data processing department generated the enrollment

figures.

-32-

been bused into that school, even greater distances to attend an

integrated school. With more students attending naturally

integrated K-5 schools, the 5th-year centers in the black

community would then have to close.

As viewed by the district court, the creation of Bodine

Elementary School in southeast Oklahoma City as a K-5 stand-alone

caused the Board to focus on the "perceived inequities" of the

stand-alone feature. 677 F. Supp. at 1513. According to the

minutes of the Board meeting which addressed the question of

maring Bodine a K-5 rather than a K-4 stand-alone,35 Board members

voiced several concerns over the process of deciding which schools

qualified and became stand-alone. (Def. Ex. 76). Dr. Clyde Muse,

a black Board member, objected that the creation of Bodine stifled

growth in the northeast quadrant and was yet another example of "a

concerted effort to see to it that not only will the black

community or the northeast quadrant not integrate, there also

seems to be a concerted effort on somebody's part to see that it

always remains impoverished." (Def. Ex. 76 at 349). Dr. Muse

lamented the inevitable closing of schools in the northeast

quadrant and urged the District undertake a study to determine

what changes had occurred that could result in a more equitable

plan for the District rather than the apparent piecemeal approach.

Id■ Another Board member, Ms. Jean Brody, urged the District to

35Prior to Bodine's designation as a K-5 stand-alone, only two

other K-5 stand-alones operated in the District. Horace Mann

Elementary School became a K-5 facility when the Finger Plan was

implemented. Arcadia was considered a K-5 stand-alone "based on

different criteria" and was treated differently because of its

isolated location. (Def. Ex. 76).

-33-

undertake a comprehensive study to avoid what she perceived as

random planning that resulted in Bodine's becoming a K-5 stand

alone, but postponed Rockwood Elementary School's becoming stand

alone although it fully qualified and had the capacity to become a

K-5 school.^

In voting to make Bodine a K-5 stand-alone, the Board

rejected the advice of Dr. Paul Heath, a board member, that the

K-5 concept was educationally unsound and would ultimately

adversely impact the entire District. Of concern to participants

at the meeting was the fact that in going to K-5 status, Bodine

fifth graders would give up the opportunity to participate in

special programs like strings and visual arts offered at the 5th-

grade centers. (Def. Ex. 76). On the positive side, however,

student reassignments necessitated by making Bodine stand-alone

were not expected to impact the existing 5th-grade centers. (Def.

Ex . 76 ) .

Similarly, the trial testimony on the hardship of stand-alone

schools echoed some of those concerns and underlined that the

Board's planning was based on theoretical conjecture, speculative

forecasting, and discretionary decision making. At the outset,

Dr. Welch noted that of the eleven stand-alone schools open in

1972, only three retained this status in the District in 1984.37

33 * * 6Before making Bodine stand-alone, the Board had agreed to add

four classrooms because of capacity problems at the school. Until

the addition was finished, however, 14 portable structures were

necessary to solve the overcrowding. Even with the new addition,

the Board estimated that 5 portables would still be needed.

(Def. Ex. 76).

21J'Overcrowding (Edgemere) and loss of racial balance caused eight

(Continued to next page.)

-34-

was tied to(R. Ill, 289). The projected number of stand-alones

or. Welch 1995 District calculations. A senior researcher for

the District, who monitored student assignments and helped prepare

projections on stand-alones, stated that although ten schools were

eligible for stand-alone status, only three were then stand-alone.

He stated that in order to create a stand-alone, the eligible

school had to have the capacity to absorb the increased number of

students. ,R. IV, 495-96); see_also Def. Ex. 69. internal Board

memoranda also addressed the possibility of creating additional

stand-alones by altering attendance boundaries, exploring

reassignment options,38 and opting fpr eithec R_4 or R_5

alones. ,B. IV, 498). Dr. Finger stated that the original plan

anticipated making as many schools stand-alone as qualified even

if some busing distances increased. "But, . . . these things get

to be political." ,R. V1II.1201,. The Sth-grade centers, he

stated, were considered temporary and were designed to be

incorporated into the middle schools.

The stand-alone feature, thus, emerged from the evidence as a

matter of speculation tied to capacity problems, budget

constraints, and local politics. Nevertheless, it was the

cornerstone upon which advocates of the need to modify or dissolve

the Finger Plan built their claim of hardship. * 3

(Continued from prior page.)

stand-alones, ̂ arrison^Edgemere^and ^ ^stand-alone. (Def. Ex. 76)? d Western Village, remained

3 8

-35-

VI. Impact of Plan on Modification

A.

We are satisfied the evidence reveals that because of

population shifts in the District, it was necessary to modify the

Finger Plan. It is within the court's equitable power to modify

the Finger Plan to mirror these changed circumstances, to retain

the unitariness of the District, and reflect the Board's

continuing duty under the decree. Just as the court can tailor

the relief to modification, so too can it dissolve the injunction

upon finding "that what it has been doing has been turned through

changing circumstances into an instrument of wrong." Swift, 2S6

U.S. at 114-15. Unfortunately, the district court perceived this

duty entirely in terms of the Board's alleged discriminatory

intent in adopting the Plan. This perception overlooks the

essential point. Given the changes that emerge from all of the

evidence presented, the court must determine whether the Plan

ameliorates those conditions. Dissolution is appropriate only if

the evidence unmistakably reveals the Plan encompasses the changed

circumstances and maintains the continuing prospective effect of

the decree.

Again, to undertake this analysis, the court must direct its

attention to "the question of the withdrawal or modification of

injunctive relief granted in the past . . . where the Cardozo

[Swift] precepts are the operating guidelines." Humble Oil & Ref.

Co., 405 F.2d at 814. Thus, while the Board's motive may be one

circumstance in evaluating the effect of the Plan, it is only an

-36-

element affecting the ultimate decision. An unimpeachable motive

cannot obscure the essential question, does the Plan relieve the

effects of changed circumstances and potential hardship? Only a

positive response will merit dissolution.

B.

The issue then becomes whether the Board's action in response

to the changed conditions has the effect of making the District

"un-unitary" by reviving the effects of past discrimination. The

new Plan must be judged in light of the old plan to assure it

mirrors actual changes in the District without so radically

departing from the original decree that the rights secured by that

decree are vitiated.

Swann guides our review in this inquiry by focusing our

attention on the Board's continuing duty to remedy the effects of

past discrimination until "it is clear that state-imposed

segregation has been completely removed." 402 U.S. at 13; see

also Columbus Bd. of Ed. v. Penick, 443 U.S. 449 (1979).39 The

inquiry into whether the Plan maintains unitariness in student

assignments may concretely be directed to evaluating (1) the

number of racially identifiable schools; (2) the good faith of

school officials in the desegregation effort and running the

schools; and (3) "whether maximum practicable desegregation of

student bodies at the various schools has been attained." Morgan,

^ Swann envisioned stability "once the affirmative duty to

desegregate has been accomplished and racial discrimination

through official action is eliminated from the system." 402 U.S.

at 32.

-37-

831 F.2d at 319. See also Brown v. Board of Educ. of 'Topeka, (No.

87-1668); Ross v. Houston Indep. School Dist., 699 F.2d 218, 227

(5th Cir. 1933) {"[T]he decision that public officials have

satisfied their responsibility to eradicate segregation and its

vestiges must be based on conditions in the district, the

accomplishments to date, and the feasibility of further

measures.”).4® No one factor is dispositive of the determination

that unitariness is preserved. However, once dismantled, the dual

school system should remain dismantled.

Thus, we are troubled because the evidence indicates the

Board's implementation of a "racially neutral" neighborhood

student assignment plan has the effect of reviving those

conditions that necessitated a remedy in the first instance.

Under these circumstances the expedient of finding unitariness

does not erase the record or represent that substantial change in

the law or facts to warrant overlooking the effect of the Board's

actions.40 41

40In Ross, despite its finding of unitariness after 12 years of

court-supervised desegregation, the Fifth Circuit affirmed the

district court's decision to retain jurisdiction for an additional

3 years.

41In its amicus brief, the government contends the successful

dismantling of a dual system represents the "changed circumstance"

making the continuation of a court's jurisdiction unjustifiable.

We are unwilling to revise Rule 60(b) to accommodate this

position. We also reject the government's contention that

sustained compliance with a desegregation plan is entitled to

great weight and should create at least a presumption of unitary

status. To do so simply eliminates any consideration of the

future value of an injunctive order and fixes for all time

equitable relief mandated by constitutional considerations on the

basis of present conditions. The extension of the government's

theory portends minority citizens have no assurance of any but

short-term and pyrrhic victories.

-38-

c.

The district court was satisfied the Plan was adopted to

remedy the increased busing burdens on young black pupils, avoid

closing 5th-year centers in the northeast quadrant, and eliminate

the inequities of stand-alone schools. Despite the emergence of

one-race elementary schools, the court found the Plan did not

disturb the District’s unitariness. The district court concluded

that unless the Plan was adopted with discriminatory intent, a

neighborhood school plan that has the effect of creating one-race

schools is not constitutionally infirm.

To reach this conclusion, the court examined the remaining

components of the Plan. While school faculties were not in

perfect racial balance, particularly in the 90%+ black elementary

schools, the court found that negotiated agreements with the

teachers' union and teacher preference and seniority accounted

for the imbalance and not Board policy.

The court did not address plaintiffs' exhibits 48, 50, 52,

and 54. The exhibits compare elementary school enrollment with

the racial composition of faculty from 1972 to 1985-87 and reflect

the growing parity of imbalance between faculty and students. By

1986-87, the 90%+ black elementary schools are staffed by

predominantly black teachers.42 Although the executive director

42For example, in 1986-87, at Edwards Elementary School, which is

99.5% black, the faculty is 70% black. At Rancho Village

Elementary School, which has a 10.6% black student population,

there are no black teachers. (PI. Ex. 54). In 1972, the Edwards'

faculty was 15% black; Rancho Village's faculty was 23% black.

(PI. Ex. 48).

-39-

teacherof personnel testified that especially after 1985,

assignments would comply with the District's affirmative action

goal of 36.9% with a 10% variance factor, the numbers belie the

aspiration.

Nevertheless, the court was satisfied that recent Board

action would "bring[] elementary faculties into racial balance in

1987-88," 677 F. Supp. at 1519, based on the statement of the

District's affirmative action program planner. However, the

record fails to support this conclusion with any specific evidence

of change to overcome plaintiffs' documented countertrend.

The district court believed that other factors in the

equation maintained the District's unitariness and offset the

racial imbalance in the elementary schools. Of prime importance

was the majority-to-minority transfer option which represented to

the court that "parents in Oklahoma City today have a choice. No

pupil of a racial minority is excluded from any school in Oklahoma

City on account of race." 677 F. Supp. at 1523. The record does

not support this assertion. In fact, there is little evidence to

determine the effectiveness and utilization of the transfer

option. Dr. Belinda Biscoe, an administrator in the department of

support programs, testified that letters were sent after the Plan

was implemented informing parents of the M & M option, but no

follow-up was done. Dr. Biscoe expressed the concern, apparently

^According to the witness, after the Plan was implemented,

teachers with seniority were permitted to choose their teaching

assignments. As a result of individual preference, many of the

faculties became imbalanced. (R. IV, 555). In fact, prior to the

Plan's implementation, Board member, Ms. Jean Brody, voiced her

concern that the current teacher agreement was negotiated "without

the knowledge that schools might be changed around." Def. Ex. 2.

-40-

voiced by the District superintendent, that parents needed more

information about the option. (R. Ill, 327). Asked if the Board

had studied the program to determine who was exercising the

transfer option, Dr. Biscoe answered that she did not believe the

numbers had been analysed. (R. Ill, 327). Dr. Betty Mason, the

assistant superintendent of high schools, agreed that the M & M

policy could not serve to desegregate the schools in the northeast

quadrant (R. V, 609) and was limited by the capacity of the

receiving school. Although Dr. Finger acknowledged the M & M

option might work if parents understood the alternative and were

willing to exercise it, he observed that often those children who

most need desegregated schools would be "the least likely to take

that option." (R. VIII, 1196). Another defense witness believed

the transfer option was available for "convenience." (R. VI,

837). There is simply no other evidence in the record to support

the court's conclusion that parents understand the availability of

the option and freely exercise it. Indeed, the court's analysis

of the figures indicating 332 parents exercised the option the

first year of the Plan and 181 the following year suggests

otherwise. 677 F. Supp. at 1523.

Likewise, the effect of the Board's desire to maintain the

District's unitariness by implementing programs like Effective

Schools, Student Interaction, Adopt-A-School, and the position of

Equity Officer is equally undocumented. The District's Effective

Schools program incorporates educational aspirations and attempts

to translate those values into enhanced student achievement. (R.

VI, 918-19). Although the court hailed a 13% decrease in the gap

-41-

between black and white achievement test results in the District

as evidence that the Effective Schools program was working, the

test comparisons are flawed. The group of students studied one

year is not the same studied the next year. (R. V, 744); see Def.

Ex. 185. While there appeared to be some gain in achievement at

eight of the 90%+ elementary schools as measured against the

national average, scores at two 90%+ schools dropped. (R. VI,

942). More significantly, the meaning of the gain was not

clear.44 Additional testimony established that the Effective

Schools program is geared to the upper grades (R. VII, 1004-05)

and tied to budgetary constraints experienced by the District.

(R. VI, 881). While the testimony was consistent that the

concepts of "Effective Schools" and desegregated schools are not

mutually exclusive, (R. V, 693) Board witnesses suggested that

increased expenditures for busing would necessarily cut into the

Effective School's budget. (R. VI, 944). Most importantly, there

is no evidence of specific educational programs designed for those

racially identifiable elementary schools to counteract the effect

of concentrating low achievement in these schools.

The Board designed the Student Interaction Plan to pair

schools 90%+ black with schools that do not have significant * VIII,

44Dr. Finger observed that gain is an elusive concept, noting that

"how much you can gain depends upon — on where you start. . . .

It's easier to gain at the lower level — lower part of the scale

than it is the higher part because the items are easier." (R.

VIII, 1191). Dr. Carolyn Hughes, the assistant superintendent for

curriculum and program development, stated that the District had

undertaken to study the achievement gap using a method she called

"the disaggregation of test data" which would look at "the

disproportionality in achievement by race and socioeconomic level

and gender." (R. V, 691).

-42-

racial minority populations. (R. IV, 394-95). Teachers were

encouraged to bring students together two to four times a year and

"to allow children to write letters to each other; to send video

cassettes of themselves . . . to have the children read the same

literature." (R. IV, 395). Although the program was

discretionary with each classroom teacher, the Board hoped that

perhaps nine to twelve hours a year would be devoted to the

Interaction plan. (R. IV, 407). In contrast, plaintiffs'

witness, Dr. Crain, rejected the value of student interaction

based on exchanges of letters and infrequent visits to a paired

school.* 4 ̂ Meaningful interaction, he suggested, took place on a

school athletic team or in a boy scout troop.

When the Plan was adopted, an Equity Committee chaired by an

Equity Officer4 ̂ was established to oversee the District and

assure that facilities and equipment were relatively equal