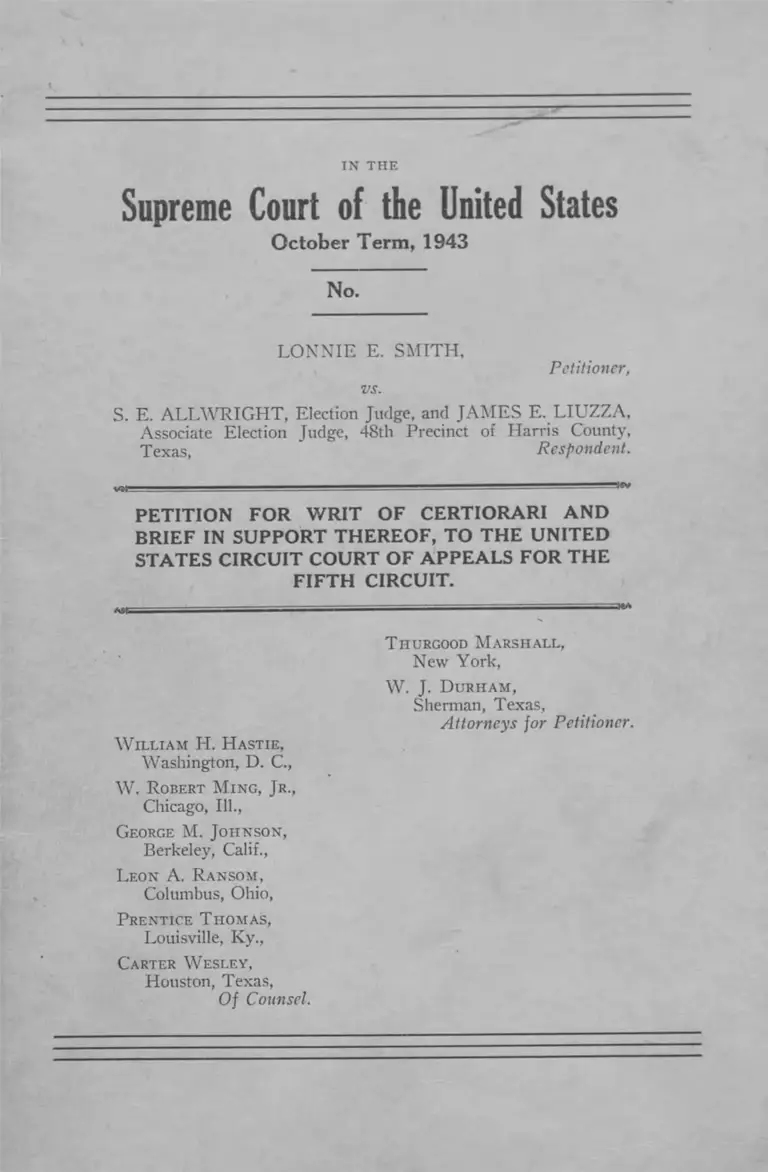

Smith v Allwright Petition for Writ Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1943

28 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Smith v Allwright Petition for Writ Certiorari, 1943. bb2475bb-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1d3b8548-0435-4897-bc45-d19cb5f7e966/smith-v-allwright-petition-for-writ-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1943

No.

LON NIE E. SMITH,

Petitioner,

vs.

S. E. ALLW RIG H T, Election Judge, and JAMES E. LIUZZA.

Associate Election Judge, 48th Precinct of Harris County,

Texas, ' Respondent.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI AND

BRIEF IN SUPPORT THEREOF, TO THE UNITED

STATES CIRCUIT COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE

FIFTH CIRCUIT.

W illiam H . H astie,

Washington, D. C.,

W . R obert M ing, Jr.,

Chicago, 111.,

George M. Johnson ,

Berkeley, Calif.,

L eon A. R ansom ,

Columbus, Ohio,

Prentice T homas,

Louisville, Ky.,

Carter W esley,

Houston, Texas,

Of Counsel,

T hurgood M arshall,

New York,

W . J. D u rh a m ,

Sherman, Texas,

Attorneys for Petitioner.

INDEX FOR PETITION.

PAGE

P art O n e :

Summary Statement of Matter Involved---------------- 2

I. Statement of the Case_______ ___ _________ 2

II. Salient Facts ____________________________ 4

P art T w o :

Question Presented _______________________________ 7

P art T h r e e :

Reasons Relied on for Allowance of the W rit______ 7

Conclusion _____.•___________________________________ 8

INDEX FOR BRIEF.

Opinion of Court Below_______________________________ 9

Jurisdiction ________________________________________ 9

Statement of the Case_________________________________ 10

Errors Below Relied Upon Here________________ 10

Argument __________________________________________ 10

I. The decision of the Circuit Court of Appeals

in this case is inconsistent with the decision of

this Court in United States v. Classic_______ 10

II. Ratio decidendi of Grovey v. Townsend should

be re-examined in the light of new facts dis

closed by the present record__________________ 15

III. Inconsistency between the decisions of this

Court in Grovey v. Townsend and United

States v. Classic apparent in their application

to the instant case should be resolved_________ 20

A. Grovey v. Townsend and United States v.

Classic present inconsistent theories as to

Federal authority over primaries which

decide elections __________________________ 21

11

PAGE

B. Grovey v. Townsend and United States v.

Classic present inconsistent theories of

what constitutes “ state action” in the con

duct of the primaries-------------------------------- 23

Conclusion ------------------------------------------------------------- 24

Table of Cases.

Bell v. Hill, 123 Tex. 531, 74 S. W. (2d) 113 (1938)-------- 17

Cf. Ex Parte Virginia, 100 U. S. 346 (1879)___________ 14

Grovey v. Townsend, 295 U. S. 45 (1935)-------------------15,17

19, 20, 21, 23

Hague v. Committee for Industrial Organization, 307

U. S. 496, 507, 519 (1939)________________________ 14

Home Telephone & Telegraph Co. v. Los Angeles, 227

U. S. 278 (1913)__________________________________ 14

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268 (1939)__________________ 14

Myers v. Anderson, 238 U. S. 368 (1914)--------------14,15,16

Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536, 540 (1927)___________ 12

United States v. Classic, 313 U. S. 299 (1941)_____11,12,14

20, 23

Statutes.

28 U. S. C., Sec. 347 (A )_____________________________ 9

Sections 31 and 43 of Title 8, U. S. C--------------- ---- ----- 10

Section 43, Title 8, U. S. C---------------------------------- --- .13,14

Section 52, Title 8, U. S. C...... ...... ..... —--- ----------------- 13,14

Criminal Code (18 U. S. C., Secs. 51 and 52)---------------- 23

General Laws of Texas, 1903, Chapter 51, p. 133--------- 5

2nd Civil Rights Act (16 Stat. 140 and 433)________— 13

Other Authorities Cited.

American Parties and Elections______________________ 12

The Pate of the Direct Primary______________________ 12

10 National Municipal Review, 23, 24------------------------- 12

Party Government in the House of Representatives— 12

Primary Elections --------------------------------------------------- 12

United States Census (1940)-------------------------------------- 19

IN T H E

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1943

No.

L o n n ie E. S m it h ,

Petitioner,

vs.

S. E. A l l w r ig h t , Election Judge, and

J am es J . L u izza , Associate Election

Judge, 48tli Precinct of Harris County,

Texas,

Respondent.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES CIRCUIT COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT.

To the Honorable, the Chief Justice of the United States

and the Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of

the United States:

Petitioner Lonnie E. Smith, appellant below, respect

fully prays that a writ of certiorari issue to review the

judgment of the Circuit Court of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit (R. 152), which affirmed a final judgment for the

respondents, defendants below, by the District Court of the

United States for the Southern District of Texas, Houston

Division (R. 85-87).

2

The opinion of the Circuit Court of Appeals appears in

the record herein (E. 150-151) and is reported in 131 F.

(2d) 593.

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under Section

240(2) of the Judicial Code (28 U. S. C., sec. 347 (a )).

PART ONE.

Summary Statement of Matter Involved.

I.

Statement of the Case.

The amended complaint alleged that on July 27, 1940,

and on August 24, 1940, the respondents, acting as election

judges of the 48th Precinct of Harris County, Texas, de

nied the petitioner and other qualified electors the right to

vote in the primaries for selection of candidates of the

Democratic party for the offices of U. S. Senator and Rep

resentatives in Congress. Petitioner sought damages for

himself and a declaratory judgment on behalf of himself

and others similarly situated that the actions of the respon

dents in refusing to permit qualified Negro electors to vote

in these primaries violated Sections 31 and 43 of Title 8

of the United States Code in that they had subjected him

to a deprivation of rights secured by Sections 2 and 4 of

Article I, and the 14th, 15tli, and 17th Amendments of the

United States Constitution (R. 4-16). The amended answer

admitted that respondents refused to permit petitioner to

vote, but denied that their actions violated the United States

Constitution or laws, because the Democratic primary in

Texas was “ a political party affair” not subject to federal

control (R. 59-71). Both parties agreed to stipulations as to

certain material facts (R. 71-76).

The case was heard upon the stipulations (R. 71-76),

depositions (R. 118-147), and oral testimony (R. 96-109).

On May 11, 1942, District Judge T. M. K e n n e r ly filed

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law (R. 80-85), and

on May 30, 1942, entered a final judgment that: (1) the

petitioner ‘ ‘ take nothing against” respondents, and (2)

issued a declaratory judgment “ that the practice of the

defendants (respondents here) in enforcing and maintain

ing the policy, custom, and usage of which planitiff (peti

tioner here) and other Negro citizens similarly situated

who are qualified electors are denied the right to cast bal

lots at the Democratic Primary Elections in Texas, solely

on account of their race or color, is constitutional, and does

not deny or abridge their rights to vote within the meaning

of the Fourteenth, Fifteenth, or Seventeenth Amendments

to the United States Constitution, or Sections 2 and 4 of

Article I of the United States Constitution” (R. 86).1

Notice of appeal to the United States Circuit Court of

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit was filed by petitioner on

June 6, 1942 (R. 148). On November 30, 1942, the United

States Circuit Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit af

firmed the judgment of the lower court (R. 153).2 Petition

for rehearing was promptly filed and denied on January 21,

1943, without opinion (R. 160).

1 The District Court reached the conclusion: “ I, therefore, follow

Grovey v. Townsend, and render judgment for defendants” (R . 85).

2 The per curiam opinion of the Circuit Court of Appeals con

cluded : “ The opinion in that case (U. S. v. Classic) did not overrule

or even mention Grovey v. Townsend (supra). W e may not overrule

it. On its authority the judgment is affirmed” (R . 152).

4

II.

Salient Facts.

All parties to this action, both petitioner and respon

dents, are citizens of the United States and of the State of

Texas, and are residents and domiciled in said State (R. 71).

Petitioner is a Negro, native born citizen of the United

States residing in Houston, Harris County, Texas, and has

been a duly and legally qualified elector under the laws of

the United States and the State of Texas, and is subject to

no disqualification (R. 71).

Petitioner is a believer in the tenets of the Democratic

party and, as found by the district judge, is a Democrat

(R. 81).

On July 27, 1940, a primary, and on August 24, 1940, a

“ run o ff” primary were held in Harris County, Texas, for

nomination of candidates upon the Democratic ticket for the

offices of U. S. Senator, U. S. Congressman, Governor and

other State and local officers. Prior to this time the respon

dents were appointed and qualified as Presiding Judge and

Associate Judge of Primaries in Precinct 48, Harris County,

Texas (R. 72, 81).

On July 27, 1940, petitioner presented himself to vote in

the said Democratic primary, at the regular polling place

for the 48th Precinct with his poll tax receipt and requested

to be permitted to vote. Respondents refused him a ballot

because of his race and color, in accordance with alleged

instructions of the Democratic party of Texas (R. 73, 81).

The State of Texas has prescribed the qualifications for

electors in Article 6 of the Texas Constitution and Article

5

2955 of the Revised Civil Statutes of Texas, which statute

sets forth identical qualifications for voting in both “ pri

mary” and “ general” elections (R. 11,12, 23).

Primaries in Texas are created, required and controlled

in minute detail by an intricate statutory scheme.3

According to the stipulations of facts made a part of

the Findings of Facts of District Cohrt: “ At all times

material herein the only State-Wide Primaries held in

Texas have been for nominees of the Democratic Party”

(R. 72).

While there is a statutory provision requiring the pay

ment of certain primary election expenses by the candi

dates, all other expenses^are borne by the State of Texas.

The County Clerk, the Tax Assessor and Collector, and the

County Judge of Harris 'County Misperformed duties re

quired of them undqr Articles 3100-3153^evised Civil Stat

utes of Texas, in connection with holding of primaries on

July 27, 1940 and August 24,1940, without cost ro the candi

dates, or the Democratic party, or any official thereof (R.

73).

After such primary the names of the candidates receiv

ing the nomination are certified by the County Executive

3 The present election laws of Texas originated with the so-called

“ Terrell Law,” being “ An Act to regulate elections and to prescribe

penalties for its violation” (General Laws of Texas, 1903, Chapter 51,

p. 133). Sections 82 to 107 of this statute set out the requirements for

the holding of primary elections. In 1905 that Statute was repealed

and in place thereof Chapter 11 of the General Laws of Texas, 1905,

was enacted. These statutes established almost identical requirements

for both the “ primary” and “ general” elections as integral parts of the

election machinery for the State of Texas. A comparative table of

present election laws is set out in Appendix C filed herewith.

Sections of the Constitution of the State of Texas and Sections of

the Texas Election statutes are set forth in Appendix D filed herewith.

6

Committee to the State Executive Committee; the State

Execulive Committee, in turn, certifies said nominees to the

Secretary of State who places the names of these candidates

on the General Election Ballot to be voted on in the General

Election. Such services are rendered by the Secretary of

State as a part of his governmental function and are paid

for by the State of Texas. Said Secretary of State also

certifies other Party candidates as well as Independent

candidates for places upon the General Election Ballot;

such services as rendered by the Secretary of State are paid

by the State of Texas (R. 74).

contribution to the Harris County Democratic Executive

Committee, following the assessment so levied” (R. 76).

The stipulation of facts agreed upon by petitioner and

respondents provides that: “ Since 1859 all Democratic

nominees, for Congress, Senate and Governor, have been

elected in Texas with two exceptions” (R. 72).

7

PART TW O.

Question Presented.

Does the Constitution of the United States prohibit the

exclusion of qualified Negro electors f rom voting in primary

elections which are an integral part of the election

machinery of the State and which are determinative of the

choice of federal officers?

PART THREE.

Reasons Relied on for Allowance of the Writ.

I. T h e decision of t h e C ir cu it C ourt of A ppeals in

THIS CASE IS INCONSISTENT WITH THE DECISION OF THIS COURT

in U n ited S tates v . C lassic .

II. R atio decidendi of G rovey v . T ow n sen d sh o u ld be

re -exam in ed in t h e l ig h t of n e w facts disclosed by t h e

presen t record.

III. I n co n sisten cy betw een t h e decisions of t h is

C ourt in G rovey v . T ow n sen d and U n ited S tates v . C lassic

APPARENT IN THEIR APPLICATION TO THE INSTANT CASE SHOULD

BE RESOLVED.

A. G rovey v. T ow n sen d and U n ited S tates v . C lassic

PRESENT INCONSISTENT THEORIES AS TO FEDERAL AUTHORITY

OVER PRIMARIES WHICH DECIDE ELECTIONS.

B. G rovey v. T ow n sen d and U n ited S tates v . C lassic

PRESENT INCONSISTENT THEORIES OF WHAT CONSTITUTES

“ STATE ACTION” IN THE CONDUCT OF PRIMARIES.

8

Conclusion.

Wherefore, it is respectfully submitted that this

petition for writ of certiorari to review the judgment

of the United States Circuit Court of Appeals for the

Fifth Circuit, should be granted.

T hurgood M a r sh a ll ,

New York,

W. J. Durham,

Sherman, Texas,

Attorneys for Petitioner.

W il l ia m H . H astie ,

Washington, D. C.,

W . R obert M in g , J r .,

Chicago, 111.,

G eorge M . J o h n s o n ,

Berkeley, Calif.,

L eon A. R a n so m ,

Columbus, Ohio,

P ren tice T h o m a s ,

Louisville, Ky.,

C arter W esley ,

Houston, Texas,

Of Counsel.

IN T H E

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1943

No.

L o n n ie E. S m it h ,

Petitioner,

vs.

S. E. A l l w r ig h t , Election Judge, and

J am es J. L tjizza, Associate Election

Judge, 48th Precinct of Harris County,

Texas,

Respondent.

BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF PETITION FOR WRIT OF

CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES CIRCUIT

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT.

Opinion of Court Below.

The opinion of the Circuit Court of Appeals is reported

in 131 F. (2d) 593, as well as in the record filed in this cause

(R. 150-151).

Jurisdiction.

The jurisdiction of the Court is invoked under Section

240(2) of the judicial code (28 U. S. C. Sec. 347 (A )).

The date of the judgment in this case is November 30,

1942 (R. 152). Petition for rehearing was filed within the

9

10

time provided by the Rules of the Circuit Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit and was denied on January 21, 1943

(R. 160).

Statement of the Case.

The statement of the case and a statement of the salient

facts from the record are fully set forth in the accompany

ing petition for certiorari. Any necessary elaboration on

the finding of the points involved will be made in the course

of the argument.

Errors Below Relied Upon Here.

I . T h e decision of t h e C ir cu it C ourt of A ppeals in

THIS CASE IS INCONSISTENT WITH THE DECISION OF THIS COURT

in U n ited S tates v . C lassic .

II. R atio decidendi of G rovet v . T ow n sen d sh o u ld be

RE-EXAMINED IN THE LIGHT OF NEW FACTS DISCLOSED BY THE

PRESENT RECORD.

III. I n co n sisten cy betw een t h e decisions of t h is

C ourt in G rovey v . T ow n sen d an d U n ited S tates v . C lassic

APPARENT IN THEIR APPLICATION TO THE INSTANT CASE SHOULD

BE RESOLVED.

Argument.

I.

The decision of the Circuit Court of Appeals in this case

is inconsistent with the decision of this Court in United

States v. Classic.

jQjU

In his complaint pe&lemer charged that fyda^omlents had

violated Sections 31 and 43 of Title 8, United States Code,

in that they had subjected him to a deprivation of rights

11

secured by Sections 2 and 4 of Article I and the

17th Amendment^ of the Constitution of (he United

States. The courts below held that the2jCefi«oner, a quali

fied elector of the State of Texas, could not maintain an

action for damages against the "’r ^ poMentls,

primary election judges, who refused to permit

and other qualified electors to vote in the Democratic pri

mary election^held July 27, 1940, and August 24, 1940, in

voting precinct 48, Harris County, Texas. Those rulings

were inconsistent with the decision of this Court in United

States v. Classic, 313 U. S. 299 (1941).

Democratic v

Petitioner seeks to maintain this action to obtain redress

for deprivation of a constitutional right specifically recog

nized and described by this Court in the Classic case. There,

relying on Section 2 of Article I this Court said: “ The

right of the people to choose (Congressmen) * * * is a right

established and guaranteed by the Constitution and hence is

one secured by it to those citizens and inhabitants of the

state entitled to exercise the right” (313 U. S. 299, 314).

In the Classic case, as in the instant case, the acts

complained of had been committed in connection with pri

mary elections. Nevertheless, this Court concluded that

those acts were an interference with a right “ secured by

the Constitution,” saying:

“ Where the state law has made the primary an integ

ral part of the procedure of choice, or where in fact

the primary effectively controls the choice, the right

of the elector to have his ballot counted in the pri

mary, is rightfully included in the right in Article I,

Section 2. This right of participation is protected

just as is the right to vote at the election, where the

primary is by law made an integral part of the elec

tion machinery, whether the voter exercises his right

12

at a party primary which invariably, sometimes or

never determines the ultimate choice of the repre

sentative” (313 U. S. 299, 318).1

In the instant case the record demonstrates that the laws

of the State of Texas have made the primary “ an integral

part of the procedure of choice.” No valid distinction can

be drawn between the Texas and Louisiana statutes in this

connection.2 Moreover, the history of Texas elections shows

that the Democratic primary “ effectively controls the

choice” of the elected representatives in the State,3 and re

spondents in this case have so stipulated.4

While United States v. Classic, supra, was a criminal

case, the statutory prohibition (18 U. S. C. sec. 51, 52), in

volved there closely parallels Section 43 of Title 8 of the

^"Compare statement by Holmes, in Nixon v. Herndon (273

U. S. 536, 540) 1927.

“ If the defendants’ conduct was a wrong to the plaintiff the

same reasons that allow a recovery for denying the plaintiff a vote

at a final election allow it for denying a vote at the primary election

that may determine the final result.”

2 See Appendix B for a comparative table of the Texas and Louisi

ana constitutional and statutory provisions applicable to primary elec

tions.

3 See: American Parties and Elections by Edward A. Sait (1942),

pp. 63 et seq.: The Fate of the Direct Primary by Charles Evans

Hughes, 10 National Municipal Review 23, 24; Party Government in

the House of Representatives by Hasbrouck (1927) pp. 172, 176, 177;

Primary Elections by Merriam and Overacker (1928) pp. 267-279.

On the great decrease in the vote cast in the general election

from that cast at the primary in “ one-party” areas of the country,

see George C. Stoney, Suffrage in the South, 29 Survey Graphic

163, 164 (1940). In the 1938 Texas primaries, 34.5% of the adults

voted, while in the general election the figure dwindled to 15%.

4 Both parties agreed to the following stipulation: “ Since 1859 all

Democratic nominees, for Congress, Senate and Governor, have been

elected in Texas, with two exceptions” (R . 72).

13

United States Code upon which petitioner here relies. These

sections of the United States Code are parts of the same

Acts of Congress, the legislative history of which demon

strates that they were intended to provide both civil and

criminal redress for the same wrongs.5 Both the criminal

sanction of Section 52 of Title 18 and the civil sanction of

Section 43 of Title 8 are aimed at any deprivation of con-

5 After the adoption of the 13th Amendment, a bill, which became

the first Civil Rights Act (14 Stat. 27) was introduced, the major

purpose of which was to secure to the recently freed Negroes all the

civil rights secured to white men including language similar to that in

Section 43 of title 8 and section 52 of title 18. The 2nd Civil Rights

Act (16 Stat. 140— 16 Stat. 433) was passed for the express purpose

of enforcing the provisions of the 14th Amendment. The third civil

rights act, adopted April 20, 1871 (17 Stat. 13), reenacted the same

provisions.

Section 43 of Title 8 and Section 52 of the United States Civil Code

were both parts of the same original bill and although one provides for

civil redress and the other for crim

sections is closely similar:

Sec. 43 of Title 8

“ Every person who, under

color of any statute, ordinance,

regulation, custom, or usage, of

any State or Territory, subjects,

or causes to be subjected, any citi

zen of the United States or other

person within the jurisdiction

thereof to the deprivation of any

rights, privileges, or immunities

secured by the Constitution and

laws, shall be liable to the party

injured in an action at law, suit in

equity, or other proper proceeding

for redress. R. S. Sec. 1979.”

redress, the language of the two

Sec. 52 of Criminal Code

“ Whoever, under color of any

law, statute, ordinance, regulation,

or custom, willfully subjects, or

causes to be subjected, any inhab

itant of any State, Territory, or

District to the deprivation of any

rights, privileges, or immunities

secured or protected by the Con

stitution and laws of the United

States, or to different punish

ments, pains, or penalities, on ac

count of such inhabitant being an

alien, or by reason of his color, or

race, than are prescribed for the

punishment of citizens, shall be

fined not more than $1,000, or im

prisoned not more than one year,

or both.” (R . S. Sec. 5510, Mar.

4, 1909, c. 321, sec. 20, 35, Stat.

1092.)

14

stitutional right “ under color of any statute, ordinance,

regulation, custom, or usage of any state or territory.”

Election judges in Texas, just as in Louisiana, have author

ity to act in primary elections only by virtue of the State

laws.0 The decision of the Court below is inconsistent with

the determination made by this Court in the Classic case

that the “ alleged acts of appellees were committed in the

course of their performance of duties under Louisiana stat

utes requiring them to count the ballots, to record the result

of the count, and to certify the result of the elections. Mis

use of power, possessed by virtue of state law and made

possible only because the wrongdoer is clothed with the

authority of state law, is action taken ‘ under color o f ’ state

law” (313 U. S. 299, 325-326).* 7

Moreover, this Court having found that the misconduct

of primary election officials in the Classic case constitutes

action taken “ under color of state law” within the meaning

of Section 52 of Title 18, United States Code, it necessarily

follows that similar misconduct here involves “ state ac

tion” within the meaning of the 14th Amendment.8 Where

such misconduct is discrimination on account of the race

or color of the complaining voter, there is, likewise, a viola

tion of the 15th Amendment and section 31 of Title 8 of the

United States Code which is a part of an original act en

titled, “ A Bill to Enforce the Right of Citizens of the

8 See Appendix B.

7 Section 43 of Title 8 has been used repeatedly to enforce the

right of citizens to vote without discrimination because of race or color.

See: Myers v. Anderson, 238 U. S. 368 (1914); Lane v. Wilson, 307

U. S. 268 (1939).

8 Cf. E x Parte Virginia, 100 U. S. 339, 346 (1879); Home Tele

phone & Telegraph Co. v. Los Angeles, 227 U. S. 278 (1913) ; Hague

v. Committee for Industrial Organisation, 307 U. S. 496, 507, 519

(1939).

15

United States to Vote in the Several States of this Union

and for other purposes” (17 Stat. 13).9

It is, therefore, submitted that the decision of the Cir

cuit Court of Appeals affirming the action of the District

Court in this case is inconsistent with the decision of this

Court in United States v. Classic, supra.

II.

Ratio decidendi of Grovey v. Townsend should be re

examined in the light of new facts disclosed by the present

record.

The record formerly before this Court in Grovey v.

Townsend, 295 U. S. 45 (1935), failed to reveal or present

facts essential to an adequate legal appraisal of the so-

called “ white primary” . That decision had no proper

basis in the actualities of the Texas system, and should be

re-examined in the light of facts now revealed for the first

time in the present record. In the words of Mr. Justice

B randeis :

“ Not only may the decision of the fact have been

rendered upon an inadequate presentation of then

existing conditions, but the conditions may have

changed meanwhile.” Burnett v. Coronado Oil and

Gas Co., 285 U. S. 393, 412 (1932).

In Grovey v. Townsend, supra, this Court decided that

the present method of excluding Negroes from voting in the

Texas Democratic primary elections did not involve such

state action as is comprehended by the 14th and 15th

9 Myers v. Anderson {supra).

16

Amendments. Because the exclusionary practice was pred

icated upon a resolution of the State Democratic Conven

tion, and in the light of the record then at hand, this Court

failed to find any decisive interposition of state force in the

primary election.

Grovey v. Townsend, supra, was decided upon demurrer

to a petition for damages filed in Justice Court, Precinct

No. 1, Position No. 2, Harris County, Texas. That record

provided no factual picture of the organization and opera

tion of the so-called Democratic party of Texas and per

mitted the assumption that the “ party” had the basic struc

ture and defined membership which are characteristic of

an organized voluntary association. Moreover, on that rec

ord, this Court assumed that the privilege of voting in the

Democratic primary election was an incident of “ party

membership” and restricted to members of an organized

voluntary association called the “ Democratic party.” 10

The present record and the following analysis will show

that these supposed facts, vital to the decision in Grovey v.

Townsend, supra, did not exist.

The problem in Grovey v. Townsend, supra, as in the

present case, was the determination and evaluation of the

participation of government on the one hand, and the so-

called “ Democratic party” on the other hand, in Texas

primary elections with a view to deciding whether the con

duct of these elections was, in legal contemplation, a gov

ernmental function subject to the restraints of the 14th

10 “ While it is true that Texas has by its laws elaborately provided

for the expression of party preferences as to nominees, has required

that preference to be expressed in a certain form of voting, and has

attempted in minute detail to protect the suffrage of the members of

the organization against fraud, it is equally true that the primary is a

party primary * * *” (296 U. S. 45, 50).

17

and 15th Amendments or a private enterprise not so re

stricted. The complaint described in detail the state

statutes creating, requiring, regulating, and controlling the

conduct of primary elections in Texas. These circumstances

were summarized in the opinion of this Court (295 U. S.

45, 49-50).

In contrast, the nature, organization and functioning of

the “ Democratic party” were nowhere adequately de

scribed. Instead, the Court found it necessary to rely upon

a general conclusion of the Supreme Court of Texas in Bell

v. Hill, 123 Tex. 531, 74 S. W. (2d) 113 (1938), that the

“ Democratic party” of Texas is a voluntary association

for political purposes, functioning as such in determining

its membership and in controlling the privilege of voting in

its primaries.11

Now, for the first time, this Court has significant facts

before it which permit an independent examination of the

“ party” and its functioning and a meaningful comparison

of the roles of state and “ party” in Texas primary elec

tions. The present record shows that in Texas the Demo

cratic primary is not, as was assumed in Grovey v. Town

send, supra, an election at which the members of an organ

ized voluntary political association choose their candidates

for public office.

First, any white elector, whether he considers himself

Democrat, Republican, Communist, Socialist, or non-par

tisan, may vote in the “ Democartic” primary. The testi

11 Bell v. Hill was decided by the Supreme Court of Texas on an

original motion for leave to file a petition for mandamus. As in the

Grovey case there were no facts presented or evidence of either the

“ Democratic Party” or the actual functioning of the election

machinery.

1 8

mony of the respondent Allwright is positive and stands

unchallenged on this point.

“ Q. Mr. Allwright, when a white person comes

into the polling place during the primary election of

1940 and asks for a ballot to vote do you ever ask

them what party they belong to? A. No, we never

ask them.

Q. As a matter of fact, if a white elector comes

into the polling place to vote in the Democratic pri

mary election, he is given a ballot to vote; is that

correct? A. Right.

Q. And Negroes are not permitted to vote in the

primary election? A. They don’t vote in the pri

mary.

Q. But any white person that is qualified; regard

less of what party they belong to, they can vote ? A.

That is right.

Q. And you do let them vote? A. Yes” (R. 106).

Second, the “ Democratic party” of Texas has no iden

tified membership and no structure which would make its

membership determinable. Under these circumstances, it

is impossible to restrict voting in the primary election to

“ party members.” The testimony of E. B. Germany,

Chairman of the Democratic State Executive Committee,

illustrates this point (R. 119).

Third, the “ Democratic party” in Texas is not orga

nized. Officials claiming to represent the “ party” testi

fied positively that the “ party” has no constitution nor

by-laws (R. 146), and is a “ loose jointed organization”

(R. 126). No minutes or records of the periodic “ party”

conventions are preserved (R. 131). The “ party” has no

officers between conventions (R. 125, 143). Beyond the lack

of organic party law, there is no formulated body of party

19

doctrine. No resolutions of the state conventions are pre

served (R. 137). Even the resolution upon which the ex

clusion of Negroes from the primaries is predicated is not

a matter of record and has no existence as a document

(R. 136). At the trial, the alleged contents of the resolu

tion were proved, over the objection of the petitioner, by

the recollection of a witness who testified that he had intro

duced such a resolution, and was present when it was

adopted (R. 138).

The only rules and regulations governing the “ Demo

cratic party” and the “ Democratic primary” elections are

the election laws of the State of Texas (R. 133-134). This

startling state of affairs is perhaps the most striking evi

dence of a one-party political system where for all prac

tical purposes the “ Democratic party” is co-extensive with

the body politic and, hence, needs no private organization

to distinguish it from other parties.

In such circumstances the legal character of the pri

mary elections, and the status of those who conduct them,

can be derived only from the one organized agency, which

creates, requires, regulates and controls these elections,

namely, the State of Texas. The factual material supplied

in this record, but not available in the record of Grovey v.

Townsend, supra, compels this conclusion. Inadequately

informed, this Court sanctioned the practical disenfran

chisement of 540,565 adult Negro citizens, 11.86% of the

total adult population (citizens) of Texas.12 It is for the

correction of this error and the resultant deprivation of

constitutional right that the present petition is submitted.

12 United States Census (1940). (Figures include native born

and naturalized adult citizens.)

20

III.

Inconsistency between the decisions of this Court in

Grovey v. Townsend and United States v. Classic apparent

in their application to the instant case should be resolved.

The District Court and the Circuit Court of Appeals

refused to follow the decision in United States v. Classic,

supra, because of their belief that the instant case was con

trolled by the earlier decision in Grovey v. Townsend,

supra. The District Court concluded: “ I, theretox-e, fol

low Grovey v. Townsend, and render judgment for Defen

dants” (R. 85). The Circuit Court of Appeals likewise

followed the Grovey case in affirming the lower court. In

a per curiam opinion it was stated:

‘ ‘ The Texas statutes regulating party primaries

which were considered in Grovey v. Townsend are

still in force. They were held not to render the pri

mary an election in the constitutional sense. There

is no substantial difference between that case and

this. It is argued that different principles were an

nounced by the Supreme Court in United States v.

Classic, 313 U. S. 301. The latter was a criminal

case from Louisiana, and did not involve the Texas

statutes. It differs in many points from this case.

The opinion of the court in that case did not overrule

or even mention Grovey v. Townsend (supra). We

may not overrule it. On its authority the judgment

is affirmed” (R. 152).

In thus following the Grovey case rather than the Clas

sic case, the District Court and the Circuit Court of Ap

peals made a choice between apparently inconsistent legal

theories of this Court as to federal control over primaries.

21

A. Grovey v. Townsend and United States v. Classic

present inconsistent theories as to Federal author

ity over primaries which decide elections.

The decision in the Grovey case was based on the theory

that the right to participate in the Democratic Primary is

one of the privileges incidental to membership in the Demo

cratic Party of Texas and should not be confused with “ the

right to vote.” Thus, the opinion stated:

“ The complaint states that * * * in Texas nomi

nation by the Democratic party is equivalent to elec

tion. These facts (the truth of which the demurrer

assumes) the petitioner insists, without more, make

out a forbidden discrimination. * * * The argument

is that as a Negro may not be denied a ballot at a

general election insignificant and useless, the result

is to deny him the suffrage altogether. So to say is

to confuse the privilege of membership in a party

with the right to vote for one who is to hold a public

office. With the former the state need have no con

cern, with the latter it is bound to concern itself,

for the general election is a function of the state

government and discrimination by the state as re

spects participation by Negroes on account of race

or color is prohibited by the Federal Constitution”

(295 U. S. 45, 54).13

In following the decision in the Grovey case the lower

courts ignored the reasoning in the Classic case that in a

state where choice at the primary is tantamount to election,

the right to vote in the primary is derived not from the

party but from the Constitution. In the Grovey case the

13 Similar reasoning appears throughout the Grovey decision: e. g.,

“ Here the qualifications of citizens to participate in party counsels and

to vote at primaries has been declared by the representatives of the

party in convention assembled, and this action upon its face is not state

action” (295 U. S. 45, 48).

22

question as to whether or not federal authority extended to

primary elections was approached by a consideration of

the relation between the Democratic primary elections and

the “ Democratic party” in Texas. In the Classic case the

Court viewed as controlling the fundamental relationship

between the Democratic primary elections and the choice

of office-holders. The Court was not concerned with who

ran the machinery but with the practical operation of that

machinery upon the expression of choice.14

The Grovey case was a complaint for damages in a state

court based solely upon the Fourteenth and Fifteenth

Amendments, and this Court, therefore, centered its atten

tion upon the question of what constituted “ state action”

under those Amendments. Yet the language of the opinion

is so broad as to create the impression that the effect of the

primary in controlling the choice of office-holders has no

bearing whatsoever upon the question of federal authority

over the conduct of primary elections. The lower courts

here gave this all-inclusive effect to the language of the

Grovey case thereby ignoring the decision of this Court in

the Classic case that the right to vote in such a primary is

derived from the Constitution and protected by federal

statutes not involved in the Grovey case.

14 “ The right of the people to choose (Congressmen), * * * is a

right established and guaranteed by the Constitution and hence is one

secured by it to those citizens and inhabitants of the state entitled to

exercise the right” (313 U. S. 299, 314).

23

B. Grovey v. Townsand and United States v.

Classic present inconsistent theories of what

constitutes “state action” in the conduct of the

primaries.

The Louisiana and Texas election statutes are substan

tially alike. On the basis of the Louisiana election laws this

Court in the Classic case concluded that the Democratic

primary in Louisiana was “ an integral part of the election

machinery of Louisiana and that the election officials who

refused to count the ballots of qualified electors in the

primary election in Louisiana were rightfully charged with

violation of Sections 19 and 20 of the Criminal Code (18

U. S. C., secs. 51 and 52) because “ misuse of power, pos

sessed by virtue of State law and made possible only be

cause the wrongdoer is clothed with the authority of State

law, is action taken ‘ under color o f ’ state law’ ’ (313 U. S.

299, 326). But in the Grovey case the action of officials

conducting a primary election which was similarly created,

required, regulated and controlled by the State was held

not to be “ state action.” The essential inconsistency is

that in the Classic case the Court decided the issue of state

action by examining the relation of the state to the enter

prise in which the election judges were engaged, while in

the Grovey case the Court disregarded this relationship and

gave legal effect to the circumstances that the particular

act complained of was not authorized by the state. I f the

Grovey doctrine had been applied in the Classic case it

would have led to the conclusion that the election frauds

were not “ under color of state law” because they were not

authorized by the state.

It is these conflicts between the theories of United States

v. Classic and Grovey v. Townsend which should be resolved,

and resolved in accordance with the sound theory in the

Classic case.

24

Conclusion.

Wherefore, it is respectfully submitted that this

petition for writ of certiorari to review the judgment

of the United States Circuit Court of Appeals for the

Fifth Circuit, should be granted.

T hurgood M a r sh a ll ,

New York,

W . J . D u r h a m ,

Sherman, Texas,

Attorneys for Petitioner.

W il l ia m H . H astie ,

Washington, D. C.,

W. R obert Ming, Jr.,

Chicago, HI.,

G eorge M . J o h n s o n ,

Berkeley, Calif.,

L eon A. R a n so m ,

Columbus, Ohio,

P ren tice T h o m a s ,

Louisville, Ky.,

C arter W esley ,

Houston, Texas,

Of Counsel.

[2830]

L awyers P ress, I nc., 165 William St., N. Y. C .; ’Phone: BEekman 3-2300