Dinner to Announce New LDF President William T. Coleman Jr. and Launch the 1971 Appeal of the Black Lawyer Training Program

Press Release

April 21, 1971

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Volume 6. Dinner to Announce New LDF President William T. Coleman Jr. and Launch the 1971 Appeal of the Black Lawyer Training Program, 1971. e8a08c76-ba92-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1d3fb012-811a-4f1c-a051-ed9d341be183/dinner-to-announce-new-ldf-president-william-t-coleman-jr-and-launch-the-1971-appeal-of-the-black-lawyer-training-program. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

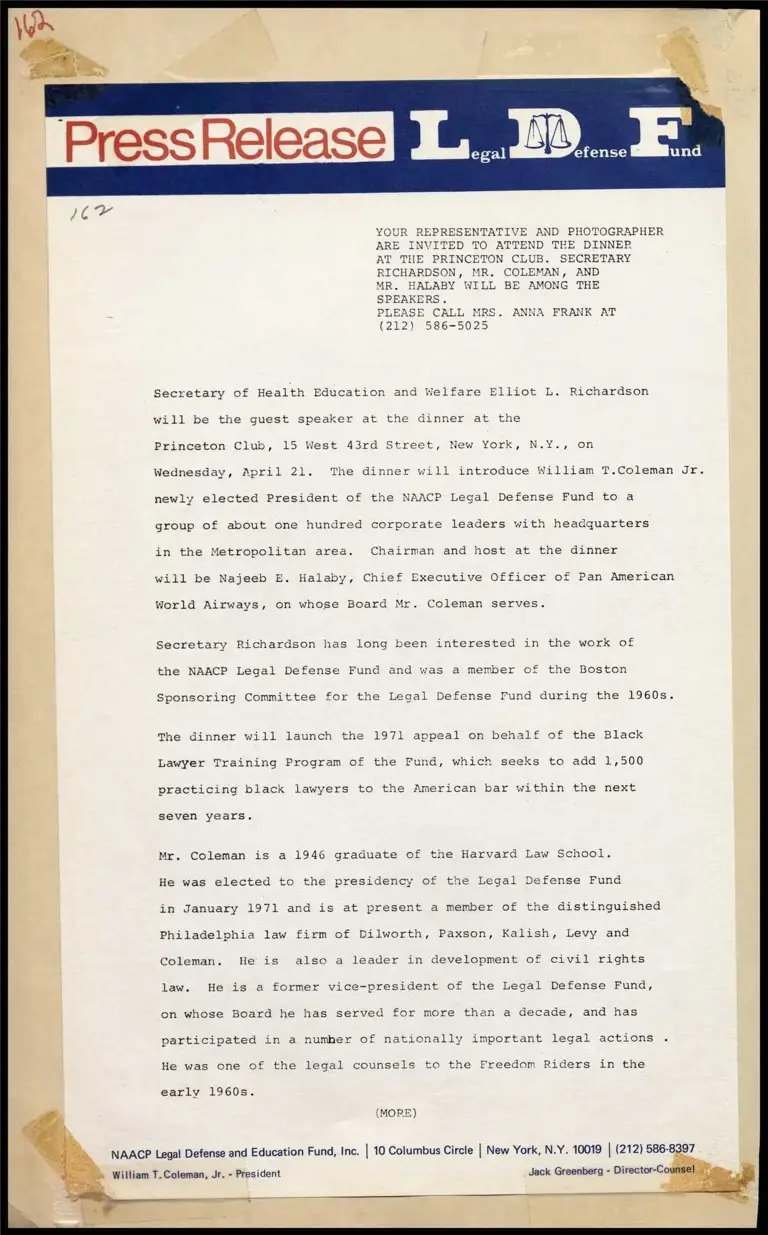

PressRelease P ame Lae sa

YOUR REPRESENTATIVE AND PHOTOGRAPHER

ARE INVITED TO ATTEND THE DINNER

AT THE PRINCETON CLUB. SECRETARY

RICHARDSON, MR. COLEMAN, AND

MR. HALABY WILL BE AMONG THE

SPEAKERS.

PLEASE CALL MRS. ANNA FRANK AT

(212) 586-5025

Secretary of Health Education and Welfare Elliot L. Richardson

will be the guest speaker at the dinner at the

Princeton Club, 15 West 43rd Street, New York, N.Y., on

Wednesday, April 21. The dinner will introduce William T.Coleman Jr.

newly elected President of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund to a

group of about one hundred corporate leaders with headquarters

in the Metropolitan area. Chairman and host at the dinner

will be Najeeb E. Halaby, Chief Executive Officer of Pan American

World Airways, on whose Board Mr. Coleman serves.

Secretary Richardson has long been interested in the work of

the NAACP Legal Defense Fund and was a member of the Boston

Sponsoring Committee for the Legal Defense Fund during the 1960s.

The dinner will launch the 1971 appeal on behalf of the Black

Lawyer Training Program of the Fund, which seeks to add 1,500

practicing black lawyers to the American bar within the next

seven years.

Mr. Coleman is a 1946 graduate of the Harvard Law School.

He was elected to the presidency of the Legal Defense Fund

in January 1971 and is at present a member of the distinguished

Philadelphia law firm of Dilworth, Paxson, Kalish, Levy and

Coleman. He is also a leader in development of civil rights

law. He is a former vice-president of the Legal Defense Fund,

on whose Board he has served for more than a decade, and has

participated in a numher of nationally important legal actions .

He was one of the legal counsels to the Freedom Riders in the

early 1960s.

(MORE)

NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, Inc. | 10 Columbus Circle | New York, N.Y. 10019 | (212) 586-8397

William T. Coleman, Jr. - President Jack Greenberg - Director-Cor