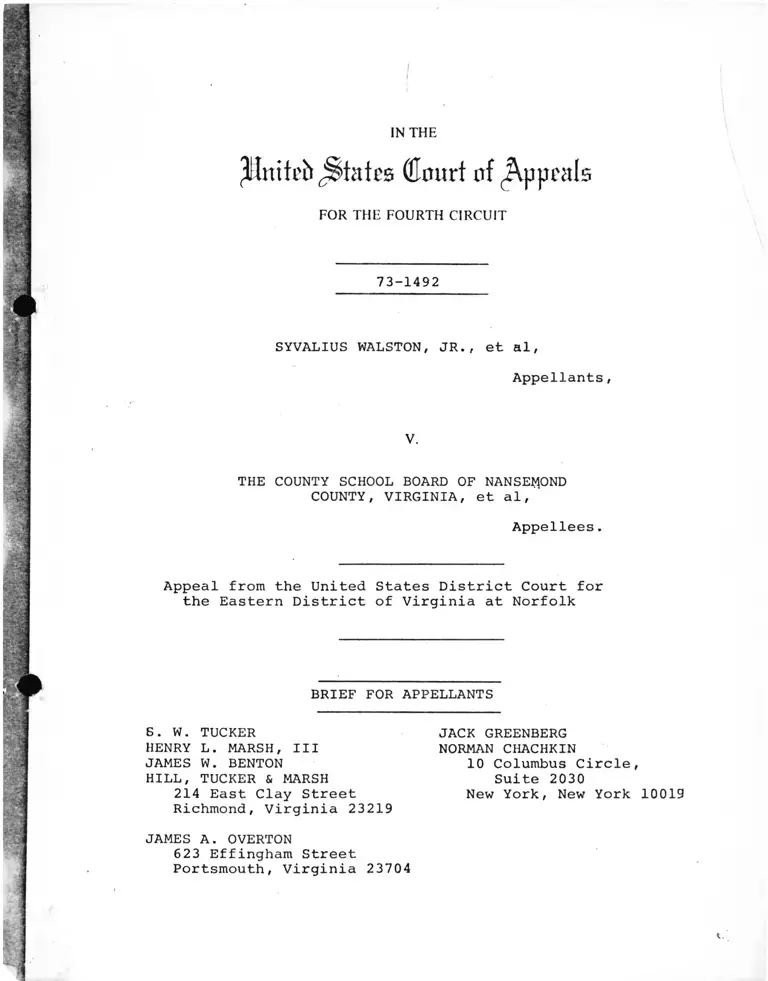

Walston v. County School Board of Nansemond County Virginia Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

July 2, 1973

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Walston v. County School Board of Nansemond County Virginia Brief for Appellants, 1973. b783536c-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1d6f4cb8-1c22-4308-8887-4c51ee6e394d/walston-v-county-school-board-of-nansemond-county-virginia-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

•lllmteh jita tes dour! nf appeals

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

73-1492

SYVALIUS WALSTON, JR., et al,

Appellants,

V.

THE COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD OF NANSEMOND

COUNTY, VIRGINIA, et al,

Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court for

the Eastern District of Virginia at Norfolk

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

S. W. TUCKER

HENRY L. MARSH, III

JAMES W. BENTON

HILL, TUCKER & MARSH

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

JAMES A. OVERTON

623 Effingham Street

Portsmouth, Virginia 23704

JACK GREENBERG

NORMAN CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle,

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ISSUES PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

Page

1

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS

3

6

A. Beginning The Transition From A

Segregated School System 6

B. The National Teachers Examination -8

C. Nansemond's Decision To Use The NTE 10

D, Application Of The NTE Policy To

The Plaintiffs .. 14

1. Plaintiff Teachers With Prior

Experience In Nansemond County 14

2 . Plaintiff Teachers Who Should Have

Been Exempted From The NTE 16

3. Transfer And Resulting NTE Requirements

May Be Imposed By The Administration 17

4. A Teacher Dismissed Despite Her

Required NTE Score 18

5. General Results Of NTE Requirement 19

Appellants Dismissed For Reasons Other

Than The NTE 20

1. Syvalius Walston 20

2. Eula Baker 23

x

ARGUMENT

I. The Board Did Not Overcome The

Strong Inference Of Racial

Discrimination Created By The

Use Of A Device Which Eliminated

Black Teachers At The Commencement

Of The Desegregation Process

II. The Board Has Demonstrated Neither A

Rational Relationship Between The

Tests And The Purpose For Which They

Were Used Nor A Compelling Interest

To Justify The Use Of The Tests

III. The School District Has Applied The

Stated NTE Policy ^Arbitrarily

IV. Syvalius Walston, Jr., And Eula Y.

Baker Were Fired For Impermissible

Racial Reasons

Page

26

33

41

43

CONCLUSION > 47

TABLE OF CITATIONS

Cases

Page

Baker v. Columbus Municipal Separate School

District, 329 F. Supp. 706 (N.D. E. D. Miss.

1971) , affirmed 462 F .2d 1112 (5th Cir.

1972) ------------------------------------ 27,32,38,39,40

Bonner v. Texas City Independent School

District, 305 F.Supp. 600 (S.D. Tex 1969) 27

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483

(1954) ----------------------------------- 26

Castro v. Beecher, 459 F .2d 725

(5th Cir. 1972) ------------------------- 38

Chambers v. Hendersonville City Board of

Education, 364 F .2d 189 (4th Cir.-1966) — 27,28,32

Griggs v. Duke Power Company, 401 U.S. 424

(1971) ------------------------------- 30,31,35,37,38,39

Hunter v. Erickson, 393 U.S. 385 (1969) --- 38

Jackson v. Wheatley School District No. 28,

430 F . 2d 1359 (8th Cir. 1970) ------------ 28,46

Johnson v. Branch, 364 F .2d 177

(4th Cir. 1966) -------------------------- - 42,45,46

Jones v. Lee Way Motor Freight, Inc.,

431 F . 2d 245 (10th Cir. 1970) ------------ 30

Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214

(1944) ----------------------------------- 38

Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967) ----- 38

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green,

41 L.W. 4651 (1973) ---------------------- 30,31,38,46

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184 (1964) - 38

Moody v. Albemarle Paper Co., 474 F .2d 134

(4th Cir. 1973) ------------------7 7— 39,40

Moore v. Board of Chidester School District,

448 F . 2d 709 (8th Cir. 1971) ------------- 45,46

North Carolina Teachers Ass'n . v. Asheboro

City Board of Education, 393 F .2d 736

(4th Cir. 1968) --------- :---------------- 28

Norwalk CORE v. Norwalk Redevelopment

Authority, 395 F.2d 920 (2d Cir. 1971) -- 38

Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 F .2d 791

(4th Cir. 1971) -------------------------- ' 39,40

United States v. Georgia Power Co.,

474 F . 2d 906 (5th Cir. 1973)-- ---------- 39

United States v. Jacksonville Terminal Co.,

451 F . 2d 418 (5th Cir. 1971) ------------- 37

- iii -

TABLE OF CITATIONS

Page

United States v. Jefferson County Board of

Education, 372 F . 2d 836 (5th Cir. 1966)-------- 28

Williams v. Kimbrough, 295 F.Supp. 578

(W.D. La. 1969) --------------------- '---------- 27,32

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886) --------- 42

IV

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

73-1492

SYVALIUS WALSTON, JR., et al,

Appellants,

v.

THE COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD OF NANSEMOND

COUNTY, VIRGINIA, et al,..

Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court^ for

the Eastern District of Virginia at Norfolk

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

ISSUES PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

I

Whether a school board, when forced to desegregate

its pupils and faculties, can utilize for the first time

the National Teacher Examination for excluding and

eliminating teachers from its faculties, where it is

shown that such examination has an adverse racial impact on

black teachers, that the value of such examination has not

been demonstrated, and that other effective methods of

excluding or eliminating teachers were not utilized?

II

Whether, in view of the disparate racial impact, the,

school board should have been required to demonstrate a

rational relationship between the tests and the purpose for

which they were used?

III

Whether, in view of the alternative methods available,

the board has demonstrated a compelling state interest in

utilizing the National Teacher Examination?

IV

Whether the district court erred in sanctioning the

arbitrary and unreasonable manner in which the defendants

have applied their stated National Teacher Examination

policy?

V

Whether the district court erred in not finding that

Syvalius Walston, Jr., and Eula Y. Baker were fired for

impermissible racial reasons?

I

« • 2.

I

3.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

On May 27, 1970, a complaint was filed by the United

States, pursuant to Title IV of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, 42 U.S.C. 2000c-6, alleging that the County School

Board of Nansemond County was operating a segregated

school system [Appendix (hereinafter referred to as A.)

pp. 12-19]. After the filing of various pleadings by both

parties, the Court held a hearing on August 13, 1970, at

which time the school board was ordered to implement a

school desegregation plan which it had submitted for the

1970-71 school year [A. pp. 23-30].

On May 13, 1971, the district court entered an order,

sua sponte, requiring the United States to file on or

before June 1, 1971, any motions for further relief which

may affect the operation of the Nansemond County schools,

and requiring the school board to file an answer on or

before June 14, 1971 [Record (herein after referred to as

R.) Vol. I, pp. 47-49]. In response to that order, the

United States filed on June 1, 1971, a motion for supple

mental relief alleging, inter alia, that the school board

had hired and fired teachers in a racially discriminatory

manner and requesting appropriate relief (A. pp. 37-39).

response thereto the school board filed a motion to

dismiss and a further answer to the motion for supplemental

relief (R. Vol. I, p. 65; A. p. 40).

On August 3, 1971, the Court held a hearing on the

objections of the United States to the school desegregation

plan for the 1971-72 school year (See R. Vol. VIII). The

Court entered an order on October 18, 1971, overruling the

objections of the United States to the school board's

desegregation plan for the 1971-72 school year but requir

ing certain modifications (A. pp. 76-77). The issues

relating to the hiring and firing of teachers were deferred

for a later hearing.

The appellants herein, certain black teachers formerly

employed by the County School Board of Nansemond County,

filed a suit against that school board on August 20, 1971

(See A. pp. 80-84) . The complaint alleges, inter alia,

that the school board is following a course of action

which will diminish the number of black teachers and that

the school board discriminated against such teachers in

violation of their Fourteenth Amendment rights. The

school board denied the allegations as set forth in the

complaint (R. Vol. Ill, pp. 10-11).

On December 8, 1971 the district court ordered the

consolidation of Civil Action No. 392-70-N (United States

v. Nansemond County School Board) and Civil Action No. 472-

71-N (Syvalius Walston, Jr., et al v. County School Board

of Nansemond County) (See A. p. 86).

: • ' 4 .

II

After extensive pre-trial conferences, objections and

discovery, the trial of this matter was held April 3 and

4 of 1972 (R. Vol. XV; R. Vol. XVI).

On November 28, 1972, the district court issued a

memorandum opinion (A. pp. 701-722). All plaintiffs, with

the exception of Mrs. Watts whose claim was raised by the

United States, were denied any and all relief (A. p. 722).

The district court entered a final order on February 27,

1973 (A. pp. 723-724) .

The appellants herein filed their notice of appeal

on March 30, 1973 (R. Vol. Ill, p. 133).

The United States filed a notice of appeal on April

30, 1973 (R. Vol. II, p. 308).

5.

6.

STATEMENT OF FACTS

A. Beginning The Transition From A

Segregated School System

Prior to the 1970-71 school year/ the County School

Board of Nansemond County maintained racially segregated

1/schools. (See PX #9) By letter to the school board

dated May 9, 1969, the Attorney General of the United

States, acting pursuant to §407 (a) of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, protested "that after three years of deseg

regation no white classroom teacher serves on a full time

basis in a minority situation * * * [and that] all schools

in the county continue to be racially identifiable by the

composition of their faculties." (A. pp. 936, 937.) -

During the 1969-70 school year, the student enroll

ment in the Nansemond County public schools was 9663, of

which 6147 (64%) were black and 3516 (36%) were white

(PX #9). Ten of the 18 schools had student enrollments

that were 100% black. The remaining eight schools had

majority white student enrollments (PX #9). Eight of

the 18 schools had faculties that were 100% black; and

the eight schools with majority white student enrollments

1/ The various parts of the record will be designated as

follows:

Trial Transcript Tr.

Government Exhibits GX

Walston Plaintiffs' Exhibits PX

Defendants 1 Exhibits DX

7.

had majority white faculties. (PX #9) . There was a total

of 451 faculty members, of whom 255 (59%) were black and

185 (41%) were white.

Commencing with the 1970—71 school year, the

school board put into effect a court ordered desegrega

tion plan utilizing pairing and zoning to bring about

the transition to a unitary school system. In addition,

the school board assigned the faculties in such a nner

that no faculty contained only teachers of one race.

Simultaneously, the school board began the implementation

of a new policy of requiring certain teachers to submit

a minimum score on the commons test of the National

Teachers Examination, hereinafter referred .to as NTE (A.

pp. 445-446).

The available data show the racial breakdown of

f

the faculty in Nansemond County to be as follows:

Yea^ Black White Total % Black

1969-70 265 186 451 59%

1970-71 267 192 460 58%

1971-72 236 219 455 52%

(A. pp. 32, 35, 725-762; PX #9).

During the first two years of operation under the court

ordered desegregation plan and the new policy of using

the NTE, the newly hired faculty members were, as follows.

2/ The government's suit seeking school desegregation

~ was filed May 27, 1970 (see A. pp. 12-19).

8.

Year Black White Total % Black

1970- 71 27 44 71 38%

1971- 72 14 84 98 14%

(A. pp. 767-770) .

Prior to 1970-71, the school board had required

each applicant to possess a baccalaureate degree, a

Virginia teacher's certificate endorsed for the grade or

subject which that individual was to teach, and three

letters of recommendation (A. pp. 829-830). Nevertheless,

23 teachers without college degrees were teaching in the

school district during the 1970-71 school year, 19 of whom

were white (A. pp. 1056-1057). During the 1971-72 school

year 19 teachers without college degrees were teaching

in the school district, 14 of whom were white (A. pp.

1054-1055). In both school years, there were 68 teachers

teaching outside their areas ,of certification, approxi

mately 50% of whom were white (A. pp. 1042-1053) .

B . The National Teacher Examination

The NTE is a test developed and administered by

the Educational Testing Service of Princeton, New Jersey

(A. pp. 1136-1137, 1184). There are two major sections

of the NTE: The Common Examinations and the Teaching

Area Examinations. The Common Examinations are designed

to measure certain aspects of. ya teacher's preparation

■'i

and general academic achievement. The Teaching Area

Examinations cover over 24 subject areas and are designed

9 .

to indicate a teacher's knowledge of his area of speciali

zation (GX #39, p. 6). The score scale for each section

is 300 to 900 (GX #39, p. 7).

There is no absolute score. All of the examinations

are separately normed on a national sample of graduating

i

college seniors. (GX #39, p. 8; A. p. 1185) . Thje indi

vidual is scored in comparison with the other persons

taking' the tests (A. p. 1185) .

The NTE was constructed to aid the various institu

tions of higher education in determining the adeq aacy of

their training programs.

been validated to predict

it was not designed

3/

job performance.

andI

i

has not

1 ,--------------- , j

3/ Dr. Deneen, Director of Teacher Examinations for the

Educational Testing Service, testified that, unlike

the Law School Aptitude Test which is "a predictive

instrument, validated against performance in law

schools" (A. p. 1201), "[t]he National Teacher Exami

nation has been validated not to predict teaching

performance as such, that is not looking forward, but

has been validated as a standardized record of a past

event. That is why it is an achievement test and not

an -aptitude test. It reflects backward upon the can

didate’s college career." (A. p. 1201).

Similarly, Dr. Rosner, Dean of Teacher Education at

the City University of New York and formerlyJthe Direc

tor of Test Development for Educational Testing Service,

testified: "* * * the original purpose in preparing

the test was to provide a more common yardstick for

assessing the end product of four years of teacner

preparation so that colleges or universities which

prepare tea,chers could determine how their students

measured up against other students undergoing similar

preparation so that one could carry out studies modi

fying the teacher training program to determine whether

or not variations in teacher training produced different

results 'in terms of the graduate's knowledges and

understanding." (A. p. 511).

t

C . Nansemond's Decision To Use The NTE

In 1970, and without benefit of prior studies or in-

depth information concerning the NTE, the school board

adopted the policy of requiring certain teachers to submit

a minimum score of 500 on the Common Examinations of the

NTS (A. p. 837; PX #7, p. 19). Teachers in certain non-

academic areas, such as physical education, driver educa

tion, and trade and industrial courses, and "teachers

currently employed" wore exempted.^ "However, if a transfer

to another school is affected, that teacher may be placed

on a three month provisional contract until such time as

he or she has had adequate opportunity to take the National

Teachers Examination and the scores reported to the

Superintendent's Office." (A. pp. 962-953.)

Teachers new to the system, whether experienced or

inexperienced, who have not taken the NTE are eligible for

employment for at least a year, within which time-they

must submit a score of 500 or suffer dismissal (A. pp.

440-441). Extensions of time may be given, depending

"on where her score was and what the possibilities were

for her to make over 500." (A. p. 439.) Teachers who

have been separated from the system for any period of

time must meet these requirements as a condition for

reinstatement.

11.

The superintendent had-two stated reasons for

recommending to the school board that the Common Examina

tions of the NTE be used in employment decisions: The

Stahl Report and the superintendent's prior experience

with teachers from North Carolina (A. pp. 360-361, 364).

In 1969, at the request of the school board, a committee

of consultants headed by Dr. Stanley Stahl made a Curricu

lum Study and Evaluation Survey of the school district.

The Stahl Report, however, has no findings, discussion

or recommendation concerning the National Teacher Examina-1/tion. (See GX #8B.)

On the basis of his own informal, undocumented

survey, the division superintendent of schools had con

cluded that a number of teachers who performed very

poorly were from North Carolina where there is an NTE

requirement for teacher certification (A. pp. 364, 835-

837) .

4/ The Stahl Report noted that, in general, "teachers

showed competency in the content matter but their

weaknesses showed in making the content meaningful

and relevant to the pupils. With rare exception,

the instructional methods were conventional, with the

teacher talking and the children listening. * * *

There is no question but that the Nansemond County

School System, must consider a massive in-service

training program, incorporating all teachers and admin

istrators into the objectives . . . An active and

' stimulating in-service training program is the prime

responsibility of the system . . . ." (GX #8B, pp.

6-7) .

/

12.

At no time prior to the school board's adoption of

the NTE as a device for selecting teachers did anyone

from the school district consult with the Educational

Testing Service about the nature of the examination or

the proper use of the examination (A. p. 1170). On

September 1, 1970, Dr. Roger Long was hired by the school

district for the position of general supervisor of the

Nansemond County public schools (A. p. 400). From his

survey, undertaken at the direction of the school adminis

tration, he concluded that there should have been changes

in the manner in which the school district used the test.

In a letter dated July 22, 1972 to an official at

Educational Testing Service, he stated:

"If any conclusions were reached by us, it would

be that our use of the examination as a screening

device is quite solidly based, but the over-all

tenth percentile cut-off used by Nansemond County

needs to be examined so that comparisons can be

made among individuals. . . . " (PX #2.)

Dr. Long's concern about the cut-off point was shared

5/

by the witness who was and by the witness who had

5/ Dr. Deneen: "ETS generally discourages the use of

cut-off scores for all of its examinations. * * * v?e

oppose them under any circumstances, and that reasoning

. . . on the part of the school district, would not

change our opinion. We would consider that an inade

quate basis to adopt something we consider a mistake

in the first place." (A. p. 1180.)

6/ .been in the employ of the Educational Testing Service.

13 .

I

6/ Dr. Rosner: "Mow, if the — if a school system wishes

to use the NTE for, let us say, an .initial screen

before deciding to hire someone, the school system,

in my judgment, should have some evidence that the

test scores differentiate among teachers who are

judged to be effective or ineffective." (A. p.

613. )

I

14 .

D. Application Of The NTE

Policy To The Plaintiffs

The teaching experience of the appellants who

were dismissed for insufficient NTE scores ranged from

thirteen years to one year, viz:

Roumaine Howell

Celestine Whitehead

Dorothy Mozelle

Evelyn Jones

Queen Malone

Thelma Corprew

Brenda Williams

Josephine Gatling

13 years

11 years

8 years

3-1/2 years

3-1/2 years

3 years '

2 years

1 year

(A. P- 386)

(PX #11 , PP- . 32-33)

(R. Vo. XV, p. 271)

(PX #15 / pp. 168-170)

(PX #12 / pp- 279-280)

(PX #13 , pp. 267-269)

(R. Vol . XV, P- 247)

(PX #10 , p- 158) •

1. Plaintiff Teachers With Prior

Experience In Nansemond County

Of the listed teachers, three (Celestine Whitehead,

Queen Malone and Evelyn Jones) had taught in Nansemond

County at some time prior to the 1970-71 school year.

Celestine Whitehead taught in Nansemond.County

from 1966 to 1968 when she resigned to join her husband,

a serviceman stationed in Europe (PX #11, pp. 50-51),

there then being no provision for a leave of absence

(PX #11, p . 55). Mrs. Whitehead taught elementary school

while in Germany (PX #11, p. 34) and earned a high recom

mendation from her principal there (g X #11; A. p. 987).

She was re-employed in Nansemond upon her return for the

1970-71 school year. (PX #11, p. 54). During the 1970-71

15.

school year, she received the Teacher of the Year award

by the Chuckatuck Ruritan Club, a white organization

(A. p. 1363-B).

Her principal for 1970-71 rated her outstanding

or above average in all categories on the "Evaluation of

Personnel" form (A. p. 936). Her principal, on the same

form, recommended her for reappointment for the 1971-72

school year. However, her contract was not renewed for

the 1971—72 school year because she did not submit a

score of at least 500 on the NTE.

Two teachers who had been required to resign

during the 1969-70 school year for reason of pregnancy,

were re-employed for 1970-71 with the condition that con

tract renewal for 1971—72 would be conditioned upon

submission of at least 500 on the NTE.

Queen Malone was first employed in Nansemond

County in January of 1968 (PX #12, p. 279) and taught

until June of 1970 (PX #12, p. 280). Her child was born

on August 12, 1970 (PX #12, p. 288). With her doctor's

permission, she requested re-employment after the birth

of her child, but was not re-employed until December of

1970 (PX #12, p. 287), wh en she was given a contract the

renewal of which was conditioned'upon the submission of

a 500 score on the NTE (A. p. 1368).

I

I

For the 1969-70 school year, Mrs. Malone had

received an overall evaluation of "above average" and

was recommended for re-employment (A. p. 990). For the

1970-71 school year, she received a similar evaluation

and recommendation for reappointment; moreover, her

principal commented that she was an excellent primary

teacher (A. p. 939). Her contract, however, was not

renewed for failure to submit a score of 500 on the NTE.

Evelyn Jones was first employed in Nansemond

County in 1967 and remained in continuous service until

January of 1970, when she had to resign for reason of

pregnancy (PX #15, pp. 169-170). During the summer of

1970 she reapplied for a teaching position in Nansemond

County and was re-employed (PX #15, p. 171). Her contract

also contained the condition that its renewal was subject

to the submission of at least a 500 score on the NTE

(A. p. 1372). She received an above average evaluation by

her principal and was recommended for reappointment

(A. p.. 9 83) . Her contract was no't renewed because she did 1

not submit an NTE score of at least 500.

2. Plaintiff Teachers Who Should

Have Been Exempted From The NTE

The NTE requirements, as stated, specifically

exempt "certain non-academic areas such as physical

16.

17.

education and driver education" and "certain trades and

industrial courses" from the minimum score of 500 (A. pp.

962-963. During the 1971-72 school year, at least three

teachers employed by the defendant were given exemptions~-

teachers of brick masonry, auto mechanics, and electronics

(A. p. 430).

However, Josephine Gatling, who was employed

to teach physical education and driver education for the

1970- 71 school year (PX #10, p. 165), was not re-employed

for the 1971-72 school year because of her failure to

submit a score of 500 on the NTE (PX #10, p. 156), despite

the fact that her ratings on the personnel evaluation

were generally above average and outstanding and she was

also recommended for reappointment by her principal (A.

p. 995). Her contract required that she submit a score

of 500 on the NTE in order to be re-employed for the

1971- 72 school year (A. p. 1365). She was denied' the

exemption that was extended others similarly situated

(A. p. 430).

3. Transfer And Resulting NTE Requirements

May Be Imposed By The Administration

The defendants also have a discretionary clause

which allows them to require a teacher currently employed

to submit a satisfactory score on the NTE "if a transfer

to another school is affected" (A. p. 963). The teacher

18.

may be placed on a three-month provisional contract until

that condition is met.

If the teacher is transferred by the system,

the teacher is not required to take the NTE. If the

teacher requests the transfer, the condition is applied.

The condition probably would be applied if a principal

requested the transfer; however, no firm guidelines have

yet been established. (A. pp. 424-425).

4. A Teacher Dismissed Despite

Her Required NTE Score____

Thelma Corprew was first employed -in Nansemond

County for the 1970-71 school year (PX #13, p. 269) . She

has a collegiate professional certificate in elementary

education and taught the fourth grade (PX #13, p. 272;

A. p. 997). Prior to her employment in Nansemond County

she had taught two years in other school systems (PX #13,

pp. 267-268). During the 1970-71 school year she was

evaluated above average in ten cat^go^iss and average

in four. Her principal recommended her for reappointment

(see A. p. 997). Her contract, however, was not renewed

at the end of the school year because she had. not sub

mitted a satisfactory score on the NTE (PX #13, p. 272.

In July of 1970, Miss Corprew took the NTE again

and scored 505 on the common examination (PX #13, p. 275).

She called Mr. Cockrell, the assistant superintendent in

charge of personnel, on August 19, 1971, to inform him

that she had scored above 500 on the NTE (PX #13, p. 275).

Mr. Cockrell informed her that all positions were filled

for the year (PX #13, p. 275. At least three white

persons filed applications after August 19, 1971, and were

hired before the 1971-72 school year began, to teach

elementary grades (see A. pp. 1101-1106).

5. General Results Of NTE Requirement

Each of the eight appellants has a collegiate

professional certificate and, therefore, is"duly certified

to teach in the State of Virginia; moreover, all were

recommended by their respective principals for reappoint

ment for the 1971-72 school year (see A. pp. 962, 986,

988, 989, 993, 994, 995, 997, 998). Each would now be

employed in Nansemond County but for the NTE requirement.

E. Appellants Dismissed For

Reasons Other Than The NTE

In addition to the appellants dismissed for

reasons of the NTE, two of the appellants were dismissed

for matters unrelated to the NTE.■

/I

20 .

1. Syvaltus Walston

Syvalius Walston was first employed as a teacher

in Nansemond County in 1961. He has a baccalaureate

degree and a Virginia collegiate professional teaching

certificate with an endorsement in elementary education -

grades 4 through 7 (A. p. 536). He taught at the Florence

Bowser School for one year. The following school year he

taught in the Portsmouth School System. He returned to

Nansemond County as a teacher during the 1964-65 school

year and taught continuously until his employment was

terminated at the end of the 1970-71 school year (A. pp.

535-536).

During the 1969-70 school year, Mr. Walston

taught science at the Oakland Elementary School (A. p.

536), which had an all-black student body and faculty

(PX #9). He was evaluated by his principal during the

school year and received an overall rating of outstanding.

He was also recommended for re—employment (See PX -n-25) .

Mr. Walston was assigned to the Southwestern

School for the 1970-71 school year, where he taught

health and physical education for seven weeks before

being assigned to teach seventh grade English (A. pp. 537-

538). In 1969 Southwestern had an all-black student body

21.

and faculty headed by David Fulton, principal. (PX #9).

Under the'1970-71 court ordered desegregation plan,

Southwestern had 363 black and 314 white students. There

were 16 black and 3 white teachers assigned for the 1970-

71 school year (see GX #1 (a)) .

On March 5, 1971, David Fulton, principal,

met with Mr. Walston and prepared an "Evaluation of

Personnel" form as required by the school board (A. pp.

538, 971-972). At that time he rated Mr. Walston out

standing in one category, above average in two, average

in ten and below average in the area of "professional

dedication" and he also recommended reappointment on

probationary status (A. pp. 480-481; see also PX #19).

There were no unsatisfactory ratings.

Superintendent Wood informed Mr. Fulton, by

letter of April 2, 1971, that a teacher could not be

recommended on probationary status and that a specific

recommendation to employ or not employ had to be made

(A. p. 1014). In response to that letter, Mr. Fulton,

by letter of April 5, 1969 (A. p. 1015), recommended

Mr. Walston for reappointment for the 1971-72 school year.

The superintendent testified that he expressed

his dissatisfaction, in a principals' meeting on April 8,

1971, at the way in which the principals were making

- ■ i . v i i n f f a i a ,

22 .

evaluations and recommendations (A. pp. 338-339). It was

his opinion that:

", . , if a principal preferred not to

live up to their responsibility and make

a fair and equitable and honest evaluation

and recommendation, then I think that

principal had made his own bed and had

to sleep in it." (A. p. 339)

Every principal employed by Nansemond County at

that time was on a non-tenured status (Tr. 454).

By letter of April 9, 1971, Mr. Fulton informed

the superintendent that he was unable to justify Mr.

Walston's recommendation following the principals' meet

ing and that "unless I hear differently from you by 3:00

P.M. Tuesday, April 13, 1971, I shall confer with each of

the teachers above and present then a copy of the enclosed

letter." (A. pp. 1016). On April 14, 1971, when Mr.

Fulton handed him a letter dated April 9, 1971 (PX #23),

Mr. Walston discovered that his principal had changed his

recommendation about reappointment (A. pp. 538).

The letter of April 9, 1971, stated that the

recommendation was changed because of incidents occurring

on March 8, 1971 and March 12, 1971 (See PX #23). Each

of these events occurred ana was known to the princxpal

prior to his letter to the superintendent dated April 5,

1971, in which he specifically recommended Mr. Walston

for reappointment. The recommendation not co reappoint

23.

Mr. Walston was made without valid justification.

Mr. Walston requested an open hearing before

the school board. He was granted a closed hearing

(A. p. 546). His principal, Mr. Fulton, decided not to

attend that hearing (A. p. 502). Although the Virginia

statutes require a hearing before the school board (see

Code of Virginia §§22-217.1 to 22-217.8), it was the

testimony of Mr. Custis, a member of the board, that in

-v

Mr. Walston's case, the school board did not vote nor

did it make a decision (PX #7, pp. 12-13) :

[By Mr. Bell]:

"Q Was a vote taken after the hearing of

Syvalius Walston?

"A No, we did not.

* * *

"Q But the Board did not make a decision,

is that correct?

"A No, we didn't make a decision...."

Mr. Walston was not given a contract for the

1971-72 school year.

2. Eula Baker

Eula Baker began teaching in 1941 in Surry

County, Virginia. She started teaching in Nansemond

County in September of 1959, where she remained until

24 .

June of 1971. Her time of teaching service is twenty-

nine years and eight months - four months short of

retirement (A. pp. 580-582). Mrs. Baker has a

baccalaureate degree and a Virginia collegiate pro

fessional teaching certificate v/ith an endorsement in

elementary education (A. p. 1012; 581).

During the 1969-70 school year, Mrs. Baker

taught at the Mount Zion School, v/hich had an all-black

*

student body and faculty (PX #27, PX #9). she was

evaluated by her principal and recommended for

reappointment (PX #27) . She remained at Mount Zion for

the 1970-71 school year, when the school was desegregated.

The student enrollment was 47% black; seven of the thirteen

faculty members v/ere black (A. pp. 582; see GX #1 (a) ) .

On January 29, 1971, Mrs. Baker was evaluated by Mr. Tucker,

her principal (A. p. 1013; Tr. 13). Mr. Fred Brown

replaced Mr. Tucker as principal of Mount Zion School on

February 22, 1971 (Tr. 407).

Mr. Brown conducted the'third evaluation of

Mrs. Baker on March 26, 1971, including the recommendations

of Mr. Tucker and Mrs. McGronan, the curriculum coordi

nator (Tr. 385; A. pp. 564, 569), at which time he rated

her above average in three categories, average in ten and

below average in one (A. p. 1012). He also recommended

her for reappointment for the 1971-72 school year (A. p. 1012).

25.

On April 8, 1971, Mr. Brown also attended the

principals' meeting at which the superintendent expressed

his disagreement with the evaluation procedure (A. p. 573.

Mr. Brown met with Mrs. Baker on April 13, 1971, and

informed her that "something had come up" and that he had

to change his recommendation (A. pp. 585, 576). Mrs.

Baker received a hearing before the school board, but

neither Mr. Brown nor Mrs. McGronan testified (A. p. 586).

As in the case of Mr. Walston, the school board took no

action (PX #7, p. 25). Mrs. Baker was not offered a

contract for the 1971-72 school year. Both of these

teachers received evaluations from their principals which

compare favorably with other teachers who were retained

for re-employment and which can not be rationally related

f

to recommendations of non re-employment (See GX #8C).

26.

A R G U M E N T

I

The Board Did Not Overcome The Strong Inference

Of Racial Discrimination Created By The Use

Of A Device Which Eliminated Black Teachers

At The Commencement Of The Desegregation Process

I

In .1969 when the Justice Department charged the school

board with operating a segregated school system and put it

on notice of the possibility of court action to desegregate

the student and teacher assignments, there was and had been

» '

no use of National Teacher Examination scores in selection,

hiring or retention of teachers. The school board adopted

the NTE requirement in January 1970 at the urging of the

superintendent (A. pp. 832, 835). j

Nansemond County school board did not desegregate its

Istudent bodies or faculties until ordered by the district

|

court (A., p. 76) in 1970, fully 16 years after Brown v.

Board of Education, 347U.S. 483 (1954). ■

The evidence in this case shows, and the district

if

court found, that the use of the cut-off score o±. 500 on

the Common Examinations of the NTE for employment decisions

has an adverse impact on the black teachers in Nansemond

County (A. pp. 708-709). The uncontradicted evidence is

that there is a demonstrable disparity between the test

scores of blacks and whites on the Common Examinations of

the NTE (A. pp. 1191-1194).

\

27.

Prior to the 1970-71 school year, 59%

were black. For the 1970-71 school year,

the NTE requirement and the first year of

new faculty members were hired, of whom 27

black.

of the teachers

the first year of

desegregation, 71

(or 38%) were

At the end of the 1970-71 school year, the school

board denied reemployment to 25 teachers, 21 of whom were

black (A. p. 764). Of the 25 teachers refused reemployment,s !

15 black and only 2 white teachers were dismissed, after a

1

year of satisfactory teaching, for failure to score>500 on

the NTE (See A. p. 764). In 1971-72, 98 new teachers were

hired in the school system of whom only 14 (dr 17-s) were

\

black (GX #2).

In Baker v. Columbus Municipal Separate School

District, [329 F. Supp. 706, 719 (N.D. E.D. Miss. 1971),

affirmed .462 F . 2d 1112 (5th Cir. 1972)], the court stated

that i

"[a] 'long history of racial discrimination, J

coupled with'disproportionate discharges in

the ranks of Negro teachers where desegrega

tion finally is begun, gives rise to a rather ,

strong inference of discrimination. * *

citing --

Williams v. Kimbrough, 295 F.Supp. 578, 585 (W.D. La. 1969).

See Bonner v. Texas City Independent School Dist., 305 F.

Supp. 600, 621 (S.D. Tex 1969); Chambers v. Hendersonville

City Bd. of Educ., 364 F .2d 189, 192 (4th Cir. 1966)

\

(en banc); North Carolina Teachers Ass’n v. Asheboro City

Board of Ed. , 393 F.2d 736 , 743 (4th Cir. 19-68) (en banc) ;

Jackson v. Wheatley School District No., 28, 430 F.2d 1359,

1363 (8th Cir. 1970); cf. United States v. Jefferson County

j

Board of Education, 372 F.2d 836 , 887-888 (5th Cir. 1966) ,

aff’d en banc, 380 F .2d 335 (1967) cert, denied, Caddo

Parish School Board v. United States, 389 U.S. 840, 88 S.Ct.

67, 19 L.Ed.2d 103. \

!In an attempt to meet the burden of the board,jas

Idescribed in Chambers, supra, and Jefferson County,;supra,

the district court made several findings of fact wnich are

1 Iunsupported by this record. " ■ \

\The Court below erroneously states that the school

I

district made inquiries of Educational Testing Service and

surrounding school districts, and conducted various studies

before adopting the NTE requirement (A. pp. 703—704). The

fact is that contact was made with the surrounding school

districts and the North Carolina Department of Teacaer

if

Certification in 1971, after the NTE was adopted (PX #1).

‘ 28.

7/

7/ Dr. Deneen commented on the superintendent's "study"

with respect -to the North Carolina teachers:

"dearly, however, v/hat mr. Wood did was not a formal

and very controlled study, and one would scarcely put

. great deal of confidence in the results of what you

might call an eyeball examination of the sampling of

candidates" (A. p. 1170)*

I

29.

Moreover, Educational Testing Service was contacted after

the requirement was adopted (PX #1; A. p. 1170). In

addition, the research and other information from journals

was gathered by Dr. Long after the requirement was adopted

t

(see A. pp. 417-420). When Dr. Long was hired in September

of 1970, one of his first assignments was to study the NTS.

His training and education are not related to testing. He

had never seen a copy of the examination prior to July 1971

and had no familiarity with the examination. His study

was superficial and unscientific (see A. pp. 411-423; 435-43o)

The district court stated that there was no evidence to

support a finding that Nansemond County intentionally dis

criminated against black teachers (A. p. 708). The ^vidence

in this record clearly indicates that the superintendent

knew that the institution of a cut-off score of 500 would

have a greater impact on the black applicants (A. pp. 832-

834, 839-840). Moreover, the following quote reveals that

the superintendent had a definite opinion concerning the

• l

blacks seeking employment with his system:

"n Do you have any opinion as to why more black

than white teachers failed to attain the scores.

"A I think I have already expressed that, and that

is the fact that many of your Negro institutions

-- and I have to say as I look down the list

all of these people are graduated from a Negro

institution-. They have open admission standards

which amount to no standards at all. If you can

pay your admission money and have graduated from

high school, then you are admitted to college.

\

30.

I think, many Negro people are going into college

who have no business being there, and they are

coming out with a remedial high school education

rather than a college education." (A. pp. 839-S40)

It was with this belief and knowledge that the super

intendent made the decision to use the cut-off score. In

the face of the clear pattern of statistical discrimination

evident- in this system, this decision is apparently condemned

by the court in Griggs v. Duke Power Company, 401 U.S. 424

(1971); also Jones v- Lee Way Motor Freight, Inc.,431 F .2d

245 (10th Cir. 1970), cert denied, 401 U.S. 954 (IS 71).1 I

As stated in McDonnell Douglas Corporation v. Percy Greer./

41 L.W. 4651, at 4655: " . . . statistics as to petitioner's

employment policy and practice may be helpful to a determi

nation of whether petitioner's refusal to rehire respondent

in this case conformed to a general pattern of discrimination

against blacks."

Thejre is yet another reason why the school board failed

to overcome its burden of rebutting plaintiffs' claims of

racial discrimination. Dr. Deneen's testimony confirmed a

if

demonstrable disparity between the score of blacks,and whites

on the NTE. He indicated that a mean score of 596 for

graduates of the white institutions tested as compared with

a mean score of 461 for graduates of black institutions

meant "that far fewer than half the [black] candidates could

possibly qualify" and that the result would be just the

opposite for -white applicants (A. pp. 1191-1194).

t

. ' 31.

In view of the unchallenged evidence that many of the

rejected teachers had been recommended - some enthusiasti

cally - for reemployment based on their actual performance,

it is clear that the NTE requirement is condemned by the

court's prohibition against standardized testing devices

which, however neutral on their face, operate to exclude

many blacks who are capable of performing effectively in

desired positions. As stated by the Court in McDonnell,

supra, at 4655: "Griggs was rightly concerned that child

hood deficiencies in the education and background of

minority citizens, resulting from forces beyond tneir con

trol, not be allowed to work a cumulative and invidious

burden on such citizens for the remainder of their lives."

The evidence shows that at least four black teachers

were the victims of irrational and uneven application of

the NTE requirement. Josephine Gatling was required to

take the examination although the policy expressly excluded

physical education instructors (A. pp. 962-963). Evelyn

Jones, who had been employed continuously in the school

district from 1967 to January of 1970 (when she had to

resign for reasons of pregnancy), was required to take the

examination when she returned in the summer of 1970 (P-̂ wl5) .

Similarly, Queen Malone, who had been employed continuously

in the school district from 1968 to June of 1970 (when she

had to resign for reasons of pregnancy), was required to

II

J

take the examination upon her return in December of 1970

(PX #12). Thelma Corprew was told in March of 1971 that

she would not be reemployed for failure to score 500 on the

NTE; and she was not reemployed although she informed tne

school officials that she had scored 505 on the NTE. Three

vacancies in her teaching area were filled immediately

thereafter by white applicants.

The court below made an explicit finding that Beulah

Watts, a black principal who was demoted, was a victim of

racial discrimination (A. p. 719).

This evidence raises an inference, which was not

overcome, that there was intentional discrimination in the

formulation and application of the NTE Common Examinations

cut-off score requirement. See Baker, supra; Chambers, supra,

32.

Williams, supra.

33.

The Board Has Demonstrated Neither A Rational

Relationship Between The Tests And The Purpose

For Which They Were Used Nor A ■Compelling

Interest To Justify The Use Of The Tests

As has been demonstrated earlier, the adoption of

the 500 cut-off score on the Common Examinations of the

NTE has caused a significant decrease in the number of

black teachers in Nansemond County. Studies conducted

by E.T.S. demonstrate that the use of a cut-off score

on the NTE falls far more heavily on blacks (A. pp. 1191-

1194) .

The evidence shows that there is no study as

documentation by either the school district or E.T.S.

which demonstrates a correlation between any score on

the NTE and effective or successful teaching (A. p. 711) .

The court thus concluded that "... the NTE lacks pre

dictive validity." (A. p. 711.)

Moreover, there is no evidence in this record to

support the court's statement that "... there is no way

to detect one teacher's effect on a class of students

for the variables are too vast." (A. p. 711.) To the

contrary, the uncontradicted testimony is that teacher

effectiveness can be measured (A. pp. 608-610), and that

it is the responsibility of the school system to come

up with the version or definition of teacher effectiveness

II

that it will apply (A. pp. 622, 643-644, 1159, 1163,

1189) .

8/

What the evidence does show, however, is that,

because of the nature and purpose of the NTL, there is

no demonstrable relationship between a given test score

and teaching ability or performance (A. pp. 612, 620-

622, 1159-1162). The testimony of both experts that

such relationship is largely unknown or is non—existenu

in this case as follows:

"Q [Dr. Deneen,] [w]hat would it measure with

respect to whether or not a teacher functions

effectively in the classroom?

"A It would measure whatever part of 'function

ing effectively in the classroom' is dependent

upon his knowledge.

f"Q Do you know what part that would be?

"A That can't be answered with any accuracy

because of the complexity of defining teaching

or good teaching or competency. In general the

studies we have done, studies with which we are

by no means completely satisfied, suggest that

knowledge is a component somewhere in the area

of 25 to 30% of the total variance or the total

8/ This is particularly appropriate here where both

experts agreed that the best way to measure a

teacher's performance is by on-site observation and

that cut-off scores should/'.never be utilized^to

eliminate a teacher when there is a record Oi job

performance (A. pp. 1177-1178). All of the appellan

teachers were evaluated favorably and recommended

for re-employment by their principals.

(A. p.

35.

universe

1160.)

called teaching behavior,

9/

"Q Dr. Rosner, having reviewed that answer that

I just handed you and heard Dr. Long's testimony

and having read some of Superintendent Wood's

deposition, do you find that the -- or what .

relationship do you find that what they have;

done establishes between their score requirement

and a teacher's performance?

1

"A So far, none.

"Q And what relationship would you find estab

lished between their score requirement and a-

teacher's ability to profit from in-service \

training?

,!A As it is reflected in this response, so far,

nothing." (A. p. 630.) t

Any possible link between the NTE and the measuring

1 !

of characteristics necessary for teaching iri Nansemond

\dissolves because of the failure of the school system)

to produce evidence that the test scores differentiate

among teachers as they are judged to be effective or

ineffective.

Just as in Griggs, supra, at 431, the test used

by Nansemond County was adopted "without meaningful

i t

study of their relationship to job performance ability."

IDr. Rosner outlined the kind of study that needed to

be done’

9/ The NTE does not measure many' other important char

acteristics required of a teacher (see A. pp. 1159-

1162; 1186-1189).

36.

"Now, on the basis of this kind of preliminary

assessment of the test, a school system would be

able to judge whether or not the test should be

studied further as a possible instrument_to_pre

dict future performance of teachers within its

own instructional settings.

"So that assuming that a school system were ;

satisfied that the test was technically well-

constructed, that the content measured by the_

test reflected the kinds of knowledges it believes

that teachers ought to possess, that the experi

ence with the test elsewhere indicated tha<_ the

test did a reasonably good job for school districts,

perhaps even similar to the one that was goijng to

use it, then the school system ought to administer

the test to a representative sample of the teachers

or cause the test to be administered to a repre

sentative sample, to attempt to obtain evidence

of the performance of the teachers in the system

to determine whether or not there was any rela

tionship between the performance on the test, and

what the system valued as teacher performance

under its own conditions of employment. \

I

"On the basis of a determined relationship between

the test score and independent evidence of teacher

performance within the specific conditions of ̂ that

particular school system, the school system ̂ migh l.

make a determination as to the degree to which

you wish to rely on tne test score as a useful

predictor of future performance.

"THE COURT: When you were operating the Testing

Service, isn't that exactly, what you and yop.r group

did?

"There must be a purpose in putting out the N1E.

"THE WITNESS: No — " (A. pp. 609-610..)

*

The school system thus uses the NTE to create an

arbitrary classification without supporting data. ̂

"Accepting arguendo that whites scoring high on thj

test perform satisfactorily . . • , to conclude that

therefore blacks scoring low could not adequately per

form the same job is a non sequitur." United States

v. Jacksonville Terminal Co., 451 F.2d 418, 456 (5th

•----------------- ---------------- — ----------------------- ‘ ' -*t

Cir. 1971) .

As was previously indicated, there has been ho

showing that the test bears a reasonable relationship to

the job performance and there is absolutely ..no evidence

m 10/ . \.that the cut-off score of 500 has a rational basjLS.

Even under a reasonable relationship standard, "... any

tests used must measure the person for the job and not

|

the person in the abstract." Griggs, supra, at 436.

10/

\i •The standard error of measurement of the tes,i_ xs

such that a "...score of 500 means that his true

score is probably between 475-525 and almost cer

tainly between 450 and 550." (A. p. 1204.) Dr.

Deneen indicated that the fact that one examinee

scored 490.and another examinee scored 502 on the

NTE " tells you nothing about their success as

a teacher nor in itself does.it really tell you

anything about their achievement in college. The

difference is too small between them." (A. pp.

1201-1202.)

38.

Griggs, however, as well as other testing cases

decided under Title 77.1, is directly applicable here,' since

the prohibitions against employment discrimination embodied

in Title VII, governing private employers, coincide with

those embodied in the Fourteenth Amendment governing public

employers. It would be anomalous indeed if public employers

had a lesser obligation than private employers to afford

equal employment opportunities. See Castro v. Beebher,

459 F . 2d 725 (5th Cir. 1972); Baker, supra. See ajt.so

McDonnell Douglas Corp., v. Green, supra, at 4654,’n.l4.

When there is evidence, as is here, of a racial impact

or classification, the school system bears the heavy burden

of demonstrating that there is a compelling interest to be

promoted. Hunter v. Erickson, 393 U.S. 385 (1969); Loving

v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967); McLaughlin v. Florida, 379

U.S. 184 (1964); Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214

(1944). This burden must be met even when there îs no

evidence of an intent to discriminate. See, e.g. ̂Norwalk

CORE v. Norwalk Redevelopment Authority, 395 F. 2d 920,931

(2d Cir. 1968) .

Xn Grigcis v. Duke Power Co. , supra, the Court stated.

"The touchstone is business necessity. If an

employment practice which operates to exclude

Negroes cannot be shown to be related to job

psrfonnance, the practice is prohibited....

(p. 431)

* * *

t

39.

" . . . but good intent or absence of discrimi

natory intent does not redeem employment pro

cedures or testing mechanisms that operate as

'built in headwinds' for minority groups and

are unrelated to measuring job capacity." (p. 432).

This standard thus requires a showing that tlje test

I

scores have a manifest relationship to the job performance

and that there is no less discriminatory alternative available.

Griggs, supra; Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d 791,

798 (4th Cir. 1971); Moody y. Albemarle Paper Co.,'; 4 74 F. 2d

134, 138 (4th Cir. 1973); United States v. GeorgiajPower Co.,

474 F.2d 906 , 912 (5th Cir. 1973); 3aker, supra.

I *

The school district has available the traditional and

universally used supervisory rating system. The rating

• •system can be made both objective and less discriminatory;

moreover, it may be more reliable than the present system

11/ Iof judging teacher performance.

It’ is not surprising that in light of such eyidence

the district court concluded that the NTE lacks predictive

validity (A. p. 711). This finding is fatal to thfe continued

I

use of the NTE because it is used by Nansemonci on tne hypo

thesis that those who score above 500 will be successful

11/ Dr. Deneen testified that "samples of behavior are

always better predictors of future behavior than is,

say, a pencil and paper test." (A. pp. 1177-1178.)

t

III

and those who do not will not be successful; ie., it is

used as a device to predict performance. There has been

no job analysis or validation studies to support this

hypothesis. See, Moody v. Albemarle Paper Co., supra at

137-140. Use of the NTE without a demonstrable correlation

between test scores and job performance violates the Due

Process Clause. Baker, supra Moody,' supra; Rooinson v.

Lorillard, supra. ,

40.

41.

Ill

The School District Has Applied

The Stated NTE Policy Arbitrarily

The school district applied its stated NTE policy

arbitrarily and thereby caused the dismissal of four black

teachers• who, under fair standards, would not have been

required to take the NTE.

Queen Malone and Evelyn Jones were required to take

the NTE even though they were not new teachers. Mrs. Malone

had taught continuously in Nansemond from January of 1968

to June of 1970. Mrs. Jones had taught continuously in

Nansemond from 1967 to January of 1970. Both were required

to resign for reasons of pregnancy. Evelyn Jones returned

to Nansemond in August of 1970 and Queen Malone returned in

December 1970 (see PX #12, #15). Both were forced to take

the NTE as a condition for reemployment.

Josephine Gatling was fired for failure to submit a

score of 500 on the NTE, although the stated policy clearly

exempted her because she taught physical education (A. pp.

962-963).

Thelma Corprew attained a score of 505 on the NTE in

July of 1970 but was refused continued employment on the

"i| .ground that there were no vacancies, while several white

teachers were immediately thereafter employed.

The Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses of the

Fourteenth Amendment prohibit the application of standards in

42.

such an uneven and irrational manner. Yick Wo v. Hopkins,

118 U.S. 355 (1886). "However wide the discretion of School

Boards, it cannot be exercised so as to arbitrarily deprive

persons of their Constitutional rights." Johnson; v.' Branch,

I

364 F.2d 177 (4th Cir. 1966). II

i

43.

Syvalius Walston, Jr., And

Eula Y. Baker Were Fired For

Impermissible Racial Reasons

Syvalius Walston, Jr., was dismissed by the school

district after nine years of successful teaching in

Nansemond for the stated reason that he received a mark of

12/"below average on his orincipal's evaluation in the area

13/

of "professional dedication" (A. pp. 481; 535-536).

The evidence demonstrates that ha was in fact dis

missed because he brought to the attention of the principal

matters involving racial inequities at his school during

the first year of student desegregation in Nansemond (A. pp

484-503; 1373-1379) .

He was reprimanded by hlis principal, David Fulton,

because he asked in a faculty meeting whether a "Negro

History Week" assembly would be allowed (A. p. 494.) . He wa

"informed by the principal that at no time would race be an

issue at this school" (A. p. 1373).

IV

12/ The evaluation sheets contain 14 areas to be rated,

each with categories of outstanding, above average,

average, below average, and unsatisfactory (See A.

1005-1011). ' ^

13/ The manual defines "professional dedication— below

average" as follows:

"Joins in or initiates criticism of the school and

other personnel. Fails to defend school against

criticism" (A. p. 1008).

44.

He was reprimanded by his principal for complaining

about segregated seating assignments on school busses

(A. pp. 487, 1373); although the practice was not halted

until a month had elapsed (A. p. 487).

He was accused by the principal of being overly con

cerned 'about the voiding of the school spelling bee contest

after a black student was the apparent winner (A. pp. 4 88-

490) .

All these matters took place prior to April $, 1971,

the date that Mr. Walston's principal recommended that he

be reappointed for the 1971-72 school year (A. p. ,1015).

After being pressured by the superintendent's, remarks

at a principals' meeting, Mr. Fulton, who was untenlred,

decided to change his decision about reappointment and

I .recommended dismissal (A. p. 1016). I |

Although Mr. Walston requested and received a hearing

before the school board, Mr. Fulton, his principal!, did not

attend the hearing (A. p. 502). Mr. Fulton never Appeared

• i

before the school board to explain why Mr. Walston was not

recommended for reappointment; moreover, the school board

did not vote on the matter and did not render a decision

(PX #7, pp. 12-13). Syvalius Walston, however, was not

raemployed for the 1971-72 school year.

\

45.

Similarly, Eula Baker was not reemployed for the

1971-72 school year, after having taught successfully in

Nansemond since 1959. Because of her dismissal she lacks

four months teaching credit needed for full retirement

after 30 years (A. pp. 580-532).

As in the matter of Mr. Walston, Mrs. Baker's

untenured principal, Fred Brown, changed his original recom

mendation of reemployment after attending the principals'

meeting and after being told by the assistant superintendent

that Mrs. Baker was incompetent (A. pp. 573-575). Mr. Brown

told Mrs. 3aker that "something had come up" and that he

could not recommend reemployment.

Neither Mr. Brown nor Mrs. McGronan stated reasons

r

for terminating Mrs. Baker's employment at the school board

hearing (A. p. 586). The school board took no vote and

made no decision (PX #7, p. 25). Mrs. Baker was terminated.

The evidence conclusively demonstrates that both

teachers were dismissed for impermissible racial reasons

and that the school district acted arbitrarily and capri

ciously in refusing to reemploy them. See Johnson v.

Branch, supra; Moore v. Board of Education of Chidester

School District, 448 F.2d 709. (8th. Cir. 1971).

Mr. Walston was refused reemployment because he

attempted to present to the principal, for correction,

46.

problems that occurred during the process of desegregating

the schools in Nansemond County. No other reason can be

found in this record to explain his dismissal. Federal

Courts have long protected such clear expressions of First

Amendment freedom. See Johnson v. Branch, supra. Moreover,

the stated reasons for refusing to reemploy Syvalius Walston

was "pretextual" and "discriminatory in its application"

McDonnell Douglas Corp., supra at 4655.

The school board has put forth no reason why

Mrs. Baker was dismissed other than to suggest that she

was not good enough to teach white students. Such a reason

can not stand in light of her long history of employment

in the school district. See Moore, supra, at 714; Jackson

v. Wheatley, supra, at 1363.

47.

CONCLUSION

The issues presented by this appeal are critically

important to the black teachers of Nansemond County who

were refused reemployment. For many of them, years of

teaching at a level which was considered by the school

board as "outstanding" have been ignored because of

the board’s NTE policy. That aspect, however, repre

sents only the tip of the iceberg.

The valuable lessons learned from the teacher

discharge litigation which developed in response to

desegregation efforts are instructive here. This record

reveals evidence of a supremely ironic penalty imposed

on those whose legacy has been to bear the brunt of the

struggle for equal educational opportunity.

Unless the judgment below is reversed, thousands

of black teachers will be victimized by an unfair device

and the efficacy of the judicial process will be

seriously challenged.

For these reasons, the judgment of the district

court should be reversed and remanded with instructions

for reinstatement and appropriate injunctive .relief,

; j V .including back pay and reasonable attorneys fees.

Respectfully submitted,

July 2, 1973

JAMES W. BENTON

Of Counsel for Appellants

s. W. TUCKER

HENRY L. MARSH, III

JAMES W. BENTON

HILL, TUCKER & MARSH

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia

JAMES A . OVERTON

623 Effingham Street

Portsmouth, Virgini.

JACK GREENBERG

NORMAN CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle,

New York, New York

Counsel for Appe

i

23219

a 23704

Suite 2030

10019

Hants