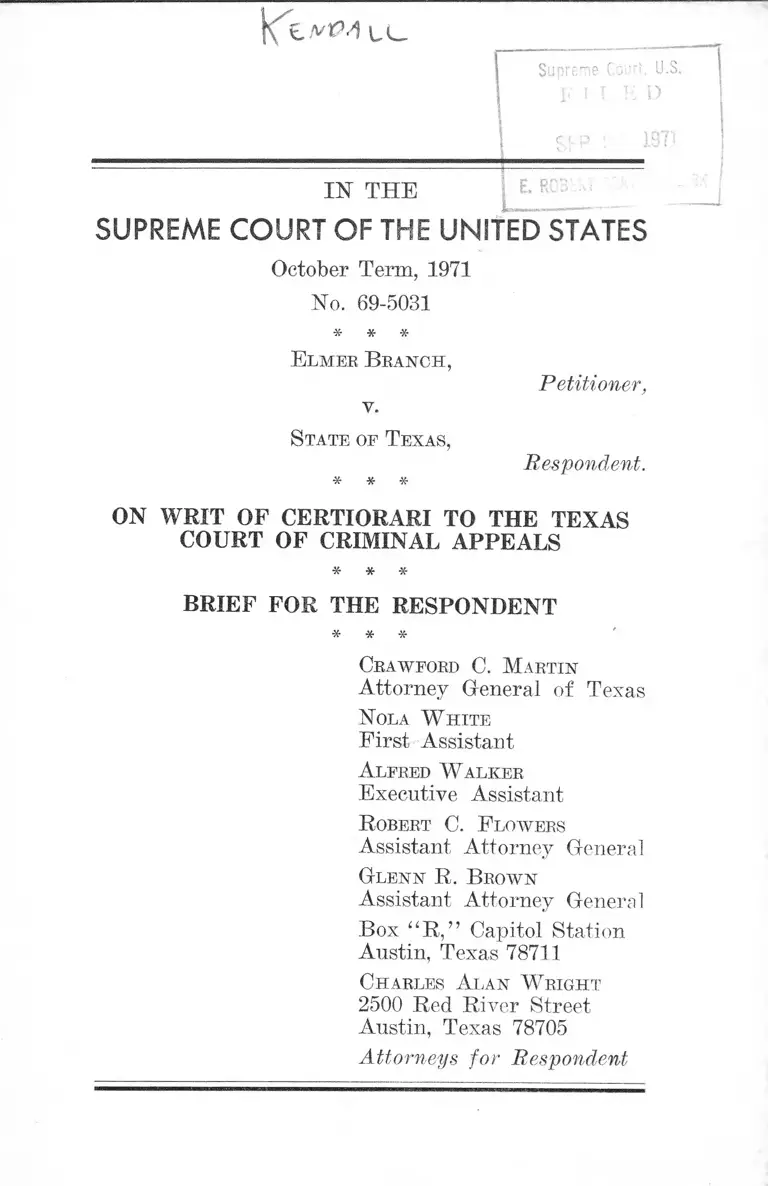

Branch v. Texas Brief for the Respondent

Public Court Documents

September 27, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Branch v. Texas Brief for the Respondent, 1971. 95869c2c-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1d834be3-bb0e-4fdd-ba41-c501c17e08e1/branch-v-texas-brief-for-the-respondent. Accessed February 04, 2026.

Copied!

ke N V A IL

Supreme Court, U

5

Cf.

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1971

No. 69-5031

* * *

Elmer B ranch,

Petitioner,

V.

State of Texas,

Respondent.* # *

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE TEXAS

COURT OF CRIMINAL APPEALS

* * *

BRIEF FOR THE RESPONDENT

* * *

Crawford C. M artin

Attorney General of Texas

Nola W hite

First Assistant

A lfred W alker

Executive Assistant

R obert C. F lowers

Assistant Attorney General

Glenn R. Brown

Assistant Attorney General

Box “ R ,” Capitol Station

Austin, Texas 78711

Charles A lan W right

2500 Red River Street

Austin, Texas 78705

Attorneys for Respondent

I N D E X

Subject I ndex

Statement of Case_______________________________ 1

Summary of Argument__________________________ 2

Argument ______________________________________ 4

I. Capital punishment may reasonably be

thought to serve the purposes of retribution

and deterrence and is not “ cruel and un

usual” within the meaning of the Eighth

Amendment_____________________________ 4

II. Captal punishment in rape cases is justified

by the seriousness of the crime and is not

“ cruel and unusual” within the meaning of

the Eighth Amendment____________________22

III. The other contentions of petitioner are not

properly in issue here______________________42

Conclusion_______________________________________44

Citations

CASES:

Anderson, In re, 69 Cal.2d 613, 447 P.2d 117

(1968) ____________________________________ 5

Calhoun v. State, 85 Tex.Cr. 496, 214 S.W. 335

(1919) ______________________________________31

Fay v. Noia, 372 U.S. 391 (1963)_______________ 22

Ginsberg v. New York, 390 U.S. 629 (1968)______19

i

Irvine v. California, 347 U.S. 128 (1954)________43

Kemmler, In re, 136 U.S. 436 (1890)__________ 6, 23

McGautha v. California, 402 U.S. 183

Goesaert v. Cleary, 335 U.S. 464 (1948)________ 12

(1971) ________________________5, 6,12,13, 21, 29

Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643 (1961)_____________ 22

Maxwell v. Bishop, 398 F.2d 138 (8th Cir. 1968) _5, 31

Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966)_______22

O’Neil v. Vermont, 144 U.S. 323 (1892)________24

Ralph v. Warden, Maryland Penitentiary,

438 P.2d 786

(4th Cir. 1970)_____11,13,23,30,32,35,36,39,41

Robinson v. California, 370 U.S. 660 (1962)_____24

Sanders v. United States, 373 U.S. 1 (1963)___ 22

State ex rel. Francis v. Resweber, 329 U.S. 459

(1947) _________________________________ 5,6,24

Townsend v. Sain, 372 U.S. 293 (1963)_________22

Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86 (1958)__________6, 7, 24

United States v. Jackson, 390 U.S. 570 (1969)_41

Weems v. United States, 217 U.S. 349 (1910) __6, 24

Wilkerson v. Utah, 99 U.S. 130 (1879)________6, 23

ii

Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510 (1968)—5, 7, 21

Williams v. New York, 337 U.S. 241 (1949)____13

STATUTES:

Act of April 30, 1790; 1 Stat. 112______________ 6

18 U.S.C. § 1751______________________________ 9

28 U.S.C. § 1257(3)_____ 43

Texas Code of Criminal Procedure, Art. 1.14—42,43

OTHER AUTHORITIES:

B edau, T he Death P enalty in A merica

(2d ed. 1967)__________________________ 8,9,17,18

Bullock, Significance of the Racial Factor in the

Length of Prison Sentences, 52 J. Crim . L., C.

&P. S. 411 (1961)____________________________ 29

Cohen, L aw W ithout Order (1970)----------------- 17

Cohen, R eason and L aw (1950)_________________ 14

Comment, The Death Penalty Gases, 56 Calie.L.

R ev. 1268 (1968)_______________________________12

Comment, Revival of the Eighth Amendment:

Development of Gruel-Punishment Doctrine ~by

the Supreme. Court, 16 Stan.L.Rev. 996 (1964) 23

Deut. 1 9 :2 1 _____________________________________ 25

Deut. 2 2 :1 5 _____________________________________ 25

iii

D uffy, 88 Men and 2 W omen (1962)

Ex. 2 2 :1 8 ___________________________

21

F lorida, R eport of the Special Commission for

the Study of A bolition of Death P enalty in

Capital Cases (1965)_________________________

FBI, U niform Crime R eports for the U nited

States 1970 (1971)________________________ 28,

F rankfurter, The Problem of Capital Punish

ment, in Of L aw and Men (1956)-----------------

Gebhard, G-agnon, P omeroy & Christenson, Sex

Offenders (1 9 6 5 )_______________________ 25,

Gibbs, Crime, Punishment, and Deterrence, 48

Sw. Soc. Sci. Q. 515 (1968)__________________

Goldberg & Dersbowitz, Declaring the Death Pen

alty Unconstitutional, 83 H arv.L.Rev. 1773

(1970) ______________________________7,11,13,

Halleck, Emotional Effects of Victimization, in

Sexual B ehavior and the L aw 673 (Slovenko

ed. 1965) ____________________________________

Hart, The Aims of the Criminal Law, 23 L. &

Contemp. P rob. 401 (1958)__________________

Hart, Murder and the Principles of Punishment:

England and the United States, 52 Nw.U.L.

R ev. 433 (1957)___________________________15,

Koeninger, Capital Punishment in Texas, 1924-

1968, 15 Crime & Del. 132 (1969)____________

25

16

40

40

33

15

16

38

14

17

29

IV

Lev. 20:21 25

Macdonald, R ape— Offenders and T heir V ic

tims (1 9 7 1 )__________________ 25, 27, 28, 30, 33, 34

Model P enal Code (Proposed Official Draft

1962) ______________________________________ 8

M odel P enal Code (Tent.Dr.No. 9, 1959)------16,40

National Commission on R eform of F ederal

Criminal Laws, F inal R eport (1971)----------- 8

Note, The Gruel and Unusual Punishment Clause

and the Substantive Criminal Law, 79 H arv.L.

R ev. 635 (1966)_________________________10, 26, 27

Note, The Effectiveness of the Eighth Amend

ment: An A.ppraisal of Cruel and Unusual

Punishment, 36 N.Y.U.L.Rev. 846 (1961)___10,11

Ohio Legislative Service Commission, Capital

P unishment (Staff Research Report No. 46,

1961) ______________________________________ 8,16

P acker, T he L imits of the Criminal

Sanction (1968) ---------------------------------- 13,14, 27

Packer, Making the Punishment Fit the Crime,

77 H arv.L.Rev. 1071 (1964)______ 19, 24, 26, 32, 41

R oyal Commission on Capital P unishment,

R eport 1949-1953, Cmd. N o. 8932

(1953) ______________________________ 14,15,17,18

v

Schwartz, The Effect in Philadelphia of Pennsyl

vania’s Increased Penalties for Rape and A t

tempted Rape, 59 J. Crim . L., C. & P. S. 509

(1968) ______________________________________24

Seney, The Sibyl at Cumae—-Our Criminal Law’s

Moral Obsolescence, 17 W ayne L .R ev. 777

(1971) ______________________________________30

Shakespeare, The Rape of Lucrece----------------------39

Sutherland & Scherl, Patterns of Response

Among Victims of Rape, 40 A mer. J.

Orthopsychiat. 503 (1970)_______________38,39

Texas P enal Code: A P roposed R evision (Final

Draft, 1970) ________________________________ 41

Williams, Rape-Murder, in Sexual B ehavior and

the L aw 563 (Slovenko ed. 1965)-------- .------- 33

W orking P apers op the National Commission

on R eform of F ederal Criminal Laws

(1970) _____________________________ 8,15,17,18

vi

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Terra, 1971

No. 69-5031

* * *

Elmek B ranch:,

Petitioner,

V.

State of Texas,

Respondent.

* * *

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE TEXAS

COURT OF CRIMINAL APPEALS

* * *

BRIEF FOR THE RESPONDENT

* * *

STATEMENT OF CASE

Shortly before 2:00 A.M. on the morning of May

9th, 1967, Mrs. Grady Stowe was awakened by an in

truder who had broken into her home twelve miles

north of Vernon, Texas, in which she was alone sleep

ing. The intruder overcame her resistance by force and

brutally raped her. Mrs. Stowe’s vivid narrative of

the events (A. 18-28) -was not cross-examined by the

defense (A. 28), and defense counsel told the jury he

had not cross-examined her “ because I feel like that

what she said was the truth, other than possibly the

identification” (A. 119-120). Any doubt but that de

fendant committed the crime was insubstantial. Mrs.

Stowe made a positive identification of him (A. 18),

he was arrested a short time after the crime (A. 35),

Ms clothing when he was arrested was as described by

Mrs. Stowe (A. 24, 30), and the tennis shoes he was

wearing made a distinctive mark that coincided with

foot prints found outside of Mrs. Stowe’s house (A.

41, 51). Mrs. Stowe was a 65 year old widow (A. 21).

Defendant was a powerful young man (A. 19) aged

20 or 21.*

The jury found defendant guilty and assessed death

as the penalty. Sentence was entered accordingly.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I. The Framers did not intend in the Eighth

Amendment to abolish capital punishment and this

Court has long and firmly supposed that punishment

to be constitutional. Even if the Amendment can take

on new meanings in the light of “ evolving standards

of decency,” there has been no change in standards

that would permit holding capital punishment to be

unconstitutional. Although there has been much debate

on the wisdom of this penalty and public opinion is

divided, the penalty is still widely accepted by the

public and by the legislatures of 41 states and the

federal government. Retribution remains one of the

legitimate aims of punishment and for some cases only

the death penalty is appropriate retribution. Legisla

tures may also conclude that capital punishment is

more effective as a deterrent of crime than is any other

penalty. Although there is no statistical evidence of

the superiority of death as a deterrent, there is other

*There is some confusion in the record about defendant’s

age. His mother testified that he was 20 at the time of the

trial two months after the rape (A. 97), but a parole sum-

mary prepared on February 25, 1966 (A. 87) listed him as

being 20 at that time (A. 89), which would have made him

21 at the time of the crime.

— 2

evidence supporting this conclusion and there is no

statistical evidence demonstrating that it is not su

perior. That executions now occur less frequently than

in the past does not show public rejection of capital

punishment and society may permissibly keep the death

penalty on the books to deter all crimes in a particu

lar class while actually imposing that penalty only on

the most extreme occurrences within the class.

II. I f capital punishment is constitutionally per

missible for some crimes, it is permissible for rape.

Even assuming that the Eighth Amendment bars not

only those punishments that are inherently cruel but

also those that are cruelly excessive, a death sentence

for rape does not run afoul of such a bar. The death

penalty may be regarded as a superior deterrent for

rape, as for murder, and there are some rapes not re

sulting in death that are so horrible that a legislature

may properly think that death is not disproportionate

retribution. Rape has always been regarded as one of

the most serious of crimes, its incidence is rising sharp

ly, and a legislature does not act unreasonably in con

cluding to retain the death penalty for rape. The argu

ment that that penalty for that offense is an attempt

to legitimize racial homicide is based on inconclusive

figures from the past. It is illusory to speak of limit

ing use of the death penalty to those cases in which the

victim’s life is endangered because in a sense this is

always so in forcible rape and there is no way to de

termine objectively whether it was the case in any

particular rape. It is also illusory to seek to confine

the applicability of the death penalty to rapes in which

the victim has suffered grievous physical or psycho

logical harm. Again there is a sense in which every rape

victim suffers lasting psychological harm and in the

— 3 —

present state of knowledge there is no way to know with

assurance what the psychological consequences on a par

ticular victim have been. The danger that a rape has

posed to the victim’s life and the extent of harm she

has suffered are legitimate considerations for a jury,

expressing the collective conscience of the community,

in determining sentence hut are not constitutional limi

tations on the use of capital punishment. It is not true

that most jurisdictions regard death as an excessive

penalty for rape and there is no trend toward aban

doning the death penalty for rape cases.

III . Petitioner’s contentions that it is a denial of

equal protection if a convicted rapist in Texas is sub

ject to the death penalty when he would not be if he

were convicted in some other state and that the Texas

procedure giving the prosecutor discretion whether to

seek the death penalty is unconstitutional cannot be

considered here. They are not within the limited grant

of certiorari, they were not presented in the petition

for the writ, and they were never raised in the state

courts.

ARGUMENT

I. Capital Punishment May Reasonably Be Thought

to Serve the Purposes of Retribution and Deterrence

and Is Not “Cruel and Unusual” Within the Meaning

of the Eighth Amendment.

Petitioner in the present case does not challenge the

constitutionality in general of capital punishment

(Branch Br. 9). He limits himself to the argument

that a death sentence for certain kinds of rape, of

4-—

which, he asserts this is one, is unconstitutional. But if

capital punishment is unconstitutional for any “ ci

vilian, peacetime crime,” as is claimed in some of the

companion cases (Aikens Br. 5), it necessarily follows

that it is unconstitutional in this case. Thus the issue

presented in Aikens and in Furman is central to the

present case as well and we must consider it before

turning to the special problems that may he thought

to he raised hy use of the death penalty in a rape case.

There is no issue before this Court of the wisdom

or social desirability of capital punishment. These are

questions addressed wholly to legislators. Even those

who are personally opposed to capital punishment may

well conclude that it violates no provision of the Con

stitution. F.g., State ex rel. Francis v. Resweber, 329

U.S. 459, 470 (1947) (Frankfurter, J., concurring) ;

Maxwell v. Bishop, 398 F.2d 138, 154 (8th Cir. 1968)

(per Blackmun, J.), vacated on other grounds 398

U.S. 262 (1970); In re Anderson, 69 Cal.2d 613, 634-

635, 447 P.2d 117, 131-132 (1968) (Mosk, J., concur

ring) ; cf. McGautha v. California, 402 U.S. 183, 226

(1971) (Black, J., concurring); Witherspoon v. Illi

nois, 391 U.S. 510, 542 (1968) (White, J., dissenting).

In terms of the usual criteria for interpreting the

Constitution, the case for the constitutionality of capi

tal punishment is a very compelling one. It seems be

yond dispute that the Framers did not intend by the

Eighth Amendment to outlaw the death penalty, a pen

alty that was “ in common use and authorized by law

here and in the countries from which our ancestors

came at the time the Amendment was adopted.” Mc-

Gautha v. California, 402 U.S. 183, 226 (1971) (Black,

J., concurring). The same Congress that proposed the

— 5 —

Eighth Amendment provided in the First Crime Act

for the death penalty for treason, murder, piracy,

counterfeiting, and other offenses. Act of April 30,

1790, §§ 1, 3, 8, 9,14, 23, 1 Stat. 112. It is equally clear

that this Court in a long line of cases has spoken of

the death penalty a,s if it were constitutional. E.g.,

Wilkerson v. Utah, 99 U.S. 130, 134-135 (1879) ; In

re Kemmler, 136 U.S. 436, 447 (1890) ; State ex rel.

Francis v. Besweber, 329 U.S. 459, 464 (1947) (plu

rality opinion) ; Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86, 99 (1958)

(plurality opinion). Only last term the Court filled

130 pages of the United States Reports with discus

sion of the constitutionality of the procedures used in

imposing the death penalty, McGautha v. California,

402 U.S. 183 (1971), a singularly academic exercise

if the Constitution does not permit that penalty ever

to he imposed. It is possible to make a nice analysis of

these cases and to decide that none of them represents

an actual holding on the constitutionality of the death

penalty hut even reading them for the least they are

worth they support what is said by petitioner in Aikens.

Obviously, the Court has long and firmly sup

posed its constitutionality; and if the question had

been appropriately posed in Wilkerson or Kem

mler, capital punishment plainly would have been

sustained. The same may be true as late as Francis,

or even Trop, * * *.

(Aikens Br. 9).

The same conclusion seems indicated even if one

concedes that the Eighth Amendment may change its

meaning with the passage of the years, as four Justices

said in Weems v. United States> 217 U.S. 349, 372-

373, 378 (1910), and the same number reiterated in

— 6

the plurality opinion in Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86,

100-101 (1958). In the latter case it was said that

the words of the Amendment are not precise, and

that their scope is not static. The Amendment must

draw its meaning from the evolving standards of

decency that mark the progress of a maturing

society.

In that same case the plurality opinion also stated that

the death penalty has been employed throughout

our history, and, in a day when it is still widely

accepted, it cannot he said to violate the constitu

tional concept of cruelty.

Id. at 99. That is no less true today. Society’s standards

of decency have not evolved that much in the interven

ing 13 years.

It is clear that there has been much debate about

the efficacy and morality of capital punishment and

that the American people are divided on this issue.

This Court took note of a 1966 poll indicating that

42% favor capital punishment while 47% oppose it.

Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510, 520 n. 16 (1968).

A 1969 poll finds 51% in favor of the death penalty.

Goldberg & Dershowitz, Declaring the Death Penalty

Unconstitutional, 83 H abv.L.Rev. 1773, 1781 n. 39

(1970). Whether the percentage is 42% or 51% is

of no significance. The fact is that public opinion is

divided with substantial support for both sides. Many

responsible citizens favor the death penalty though

the fight to abolish it “ has been waged with the fervor

of a crusade” (Aikens Br. 32). It is the abolitionists

rather than the retentionists who have organized them

selves into highly articulate lobbies and found repre

sentatives in respected public figures. Memorandum on

— 7

the Capital Punishment Issue, in 2 W orking P apers

of the National Commission on R eform of F ederal

Criminal Laws, 1347, 1363 (1970). It is the opponents

of the death penalty who have been, “ active in research

and prolific in their writings.” Ohio L egislative Serv

ice Commission, Capital P unishment 31 (Staff Re

search Report No. 46, 1961).

It is not only in the polls that a sharp division ap

pears. In 1964 abolition of capital punishment carried

with 60% of the vote in a referendum in Oregon. Two

years later 65% of the voters in Colorado chose to re

tain the death penalty. B edau, T he Death P enalty in

A merica 233 (2d ed. 1967). In 1970, 64% of the voters

in Illinois chose to retain capital punishment. The

majority of special committees in Massachusetts

(1958), Pennsylvania (1961), and Maryland (1962)

have favored abolition of capital punishment while

the majority of committees in New Jersey (1964) and

Florida (1965) have favored its retention. 2 W orking

P apers of the National Commission on R eform of

F ederal Criminal L aws 1365 (1970). The commission

that considered reform of the federal criminal laws was

sharply divided, with a majority favoring abolition

while other members of the commission had strongly

held views in favor of retention. National Commission

on R eform of F ederal Criminal L aws, F inal R eport

310 (1971). The American Law Institute provided

guidance for those states that wish to retain capital

punishment, Model P enal Code § 210.6 (Proposed Of

ficial Draft 1962), and its membership voted that the

Institute should not take a position one way or the

other on abolition.

Perhaps the most significant indication of public

8 —

feeling on this issue is that 41 states and the federal

government retain capital punishment for some or

all crimes. Indeed as recently as 1965 Congress added

one more to the list of federal capital crimes when it

provided the death penalty for assassination of a Pres

ident, President-elect, or Vice President of the United

States. 18 U.S.C. § 1751, added by Act of Aug. 28,

1965, Pub.L. 89-141, § 3, 79 Stat 580.

What our legislative representatives think in the

two score states which still have the death penalty

may be inferred from the fate of the bills to repeal

or modify the death penalty filed during recent

years in the legislatures of more than half of these

states. In about a dozen instances, the hills emerged

from committee for a vote. But in none except

Delaware did they become law. In those states

where these hills were brought to the floor of the

legislatures, the vote in most instances wasn’t even

close.

B edatt, T he Death P enalty in A merica 232 (2d ed.

1967).*

Even where the abolitionist movement has been suc

cessful it has commonly not been totally so. Great

Britain, Canada, and New York have seen fit to retain

capital punishment for such varied offenses as trea

son, murder of police and corrections officials, mur

der by a person under life sentence, piracy with vio

lence, and dockyard arson (Aikens Br. 32-34). These

represent very recent legislative determinations that

for some kinds of offenses the ultimate sanction of

death must be available. Yet this kind of discriminating

* Subsequent to when the quoted passage was apparently

written, though not to its publication, capital punishment

was abolished in West Virginia and Iowa but restored in

Delaware.

— 9

legislative judgment would be impossble should it be

held that the Constitution bars capital punishment, at

least for all civilian peacetime crimes. I f there is a

constitutional barrier to the execution of Ernest Aikens

there would seem to be the same barrier to execution

of the murderer of a prison guard or a President or to

the execution of a person who successfully puts a

bomb in a crowded 747.

Given the division of opinion on capital punish

ment, it can hardly be said that “ evolving standards

of decency” now reject it, even for an ordinary murder.

When countries with whom we share many of our

values and our legal traditions have only recently con

cluded that there remain some extraordinary crimes

for which the death penalty must be preserved, the

argument that to impose a sentence of death is never

constitutional under any circumstances is seen for

what it is, an attempt to impose an absolutist view

of a debatable social policy on the states and the fed

eral government by way of a novel constitutional in

terpretation.

Neither the language of the Eighth Amendment, the

intent of the Framers, the precedents in this Court,

nor, to the extent that it may be thought relevant, a

public consensus supports the notion that capital pun

ishment is unconstitutional. Indeed, insofar as these

indicators show anything, they support the freedom of

legislatures to make their own choice on the matter.

Commentators have rejected the argument that death

is an unconstitutional punishment. Note, The Cruel

and Unusual Punishment Clause and the Substantive

Criminal Law, 79 H arv.L.Rev. 635, 638-639 (1966) ;

Note, The Effectiveness of the Eighth Amendment:

— 10 —

An Appraisal of Gruel and Unusual Punishment, 36

N.Y.U.L.Rev. 846, 859-860 (1961). Justice Goldberg

and Professor Dershowitz, who have stated the ease

against the constitutionality of capital punishment, are

forced to note that in 1969 alone there were eight state

court decisions in which the death penalty was upheld

against an Eighth Amendment attack. Goldberg &

Dersbowitz, Declaring the Death Penalty Unconstitu

tional, 83 H arv.L.Rev. 1773, 1774 n. 6 (1970), and

at least six of the circuits have held to the same effect.

Id. at 1775 n. 7. As will be more fully discussed under

Point Two of this Brief, the Fourth Circuit has found

imposition of a death sentence in some rapes to violate

the Eighth Amendment. Ralph v. Warden, Maryland

Penitentiary, 438 F.2d 786 (4th Cir. 1970). It stands

virtually alone in going that far. No court has held, as

some of petitioners in the present cases now urge, that

the Constitution prohibits the death penalty for any

civilian peacetime crime.

Petitioner in the present case makes a very able

presentation of what has been the usual argument by

some recent commentators against the constitutionality

of capital punishment (Branch Br. 23-29). Essen

tially it begins with the premise that the traditional

aim s of punishment are retribution, deterrence, iso

lation, and rehabilitation. But retribution is said to

be inconsistent with modern penological thought and

must be discounted for that reason (Branch Br. 23).

Patently a death sentence does not rehabilitate

the offender and he can be isolated as effectively in a

modern prison as by executing him. Thus the only

legitimate object that capital punishment might serve

is deterrence and recent statistical studies have given

rise to a widespread belief that capital punishment

11 —

offers no effective deterrent relief (Braneli Br. 25).

Since, on this analysis, “ the death penalty has no ra

tional place in the legitimate penal policies of modern

man” (Branch Br. 28), and is “ inconsistent with ad

vanced concepts o f behavioral science” (Branch Br.

29), it runs afoul of the Eighth Amendment.

The argument cannot he taken lightly. Conjoined

with the moral, humanitarian, and pragmatic argu

ments against capital punishment, it might well prove

persuasive to a legislature considering a change in

the law or to a governor asked to commute the sen

tences of the condemned persons in his state. But here

the argument must stand or fall on its own, since this

Court is limited to the issue of constitutionality and

cannot write into the law its notions of morality or

humanitarianism or its pragmatic preferences. As a

purely constitutional argument, the analysis made by

petitioner gives too little weight to the elements of

retribution and deterrence and it gives too much

weight to “ advanced concepts of behavioral science.”

The Constitution does not require legislatures to

reflect sociological insight, or shifting social stand

ards, any more than it requires them to keep

abreast of the latest scientific standards.

Goesaert v. Cleary, 335 TJ.S. 464, 466 (1948). See also

McGautha v. California, 402 TJ.S. 183, 221 (1971).

In the light of history, experience, and the present

limitations of human knowledge, cf. McGautha v. Cali

fornia, 402 TJ.S. 183, 207 (1971), it cannot be said

that retribution is not a legitimate end of criminal

punishment. Those who would prohibit retribution as

a purpose of criminal punishment altogether, Com

ment, The Death Penalty Cases, 56 Calif.L.Rev. 1268,

— 12 —

1349-1354 (1968), as well as those who would require

that a penalty serve some other end besides retribution

more effectively than any other less severe penalty,

Goldberg & Dershowitz, Declaring the Death Penalty

Unconstitutional, 83 H arv.L.Rev. 1773, 1796-1797

(1970), ask too much of the Eighth Amendment. This

Court has recognized that:

Retribution is no longer the dominant objeetve of

the criminal law. Reformation and rehabilitation

of offenders have become important goals of crim

inal jurisprudence.

Williams v. New York, 337 II.S. 241, 248 (1949). To

say that retribution is no longer the dominant objec

tive of the criminal law is quite different from saying

that it is no longer one of the permissible objectives

of the criminal law. The permissibility of retribution

as an objective was suggested here as recently as Mc-

Gautha v. California, 402 U.S. 183, 284 (1971) (Bren

nan, J., dissenting). See also Ralph v. Warden, Mary

land Penitentiary, 438 E.2d 786, 791 (4th Cir. 1970).

It is true that much stirring debate has been going

on in recent years about the proper role and function

of the criminal sanction. The utilitarians reject retri

bution as a purpose of the criminal law on the ground

that suffering is always evil and there is no justification

for making convicted persons suffer unless some secu

lar good can be shown to flow from doing so. The be-

havioralists reject retribution because they consider

that human conduct is determined by forces that the

individual cannot modify and that moral responsibility

cannot be ascribed to behavior that cannot be avoided.

See P acker, The L imits of the Criminal Sanction 11-

12 (1968). Perhaps one or another of these positions is

— IB —

sound but it is hardly likely that either of them is

written into the interstices of the Eighth Amendment.

Many thoughtful persons whose views cannot he

lightly discounted continue to see retribution as one

of the legitimate purposes of the criminal law. Thus

Professor Henry M. Hart wrote:

Suppose, for example, that the deterrence of of

fenses is taken to be the chief end. It will still be

necessary to recognize that the rehabilitation of

offenders, the disablement of offenders, the sharp

ening of the community’s sense of right and wrong,

and the satisfaction of the community’s sense of

just retribution may all serve this end by contrib

uting to an ultimate reduction in the number of

crimes. Even socialized vengeance may be accorded

a marginal role, if it is understood as the provision

of an orderly alternative to mob violence.

Hart, The Aims of the Criminal Law, 23 L. & Contemp.

P rob. 401 (1958). Morris R. Cohen argued that it is

one of the functions of the criminal law to give ex

pression to the collective feeling of revulsion toward

certain acts, Cohen, R eason and L aw 50 (1950), and

the Royal Commission on Capital Punishment thought

that “ retribution must always be an essential element

in any form of punishment.” R oyal Commission on

Capital P unishment, R eport 1949-1953, Cmd. Ho.

8932, at 18, S 53 (1953). In his recent full-length study

of this and related questions, Professor Herbert L.

Packer has argued that it would be socially damaging

in the extreme to discard either retribution or deter

rence as a ground for punishment. P acker, The L imits

of the Criminal Sanction 36-37 (1968).

The view is still widely held that for some particu

larly serious and offensive crimes no penalty short

— 14 —

of death adequately satisfies the community’s sense

o f just retribution. Perhaps the view is unfortunate

and backward hut it is one that a legislature is con

stitutionally free to hold.

The legislature could also reasonably think that the

death penalty is superior as a deterrent to any other

punishment. This has been at the heart of the aboli

tionist case in recent years. Statistical studies, by Pro

fessor Thorsten Sellin and others, have been made

to compare the homicide rate in jurisdictions with the

death penalty and those without it. Attempts have been

made to refine these studies by comparing jurisdictions

that are thought to be generally similar and by ex

amining the experience in a particular jurisdiction

at a time when it had the death penalty and at a time

when it did not. These figures clearly demonstrate

that there is no statistical proof that the death penalty

is a superior deterrent. They do not justify the con

clusion that the death penalty is not a superior de

terrent, though, as Professor H. L. A. Hart has noted,

“ many advocates of abolition speak as if the second

were a warranted conclusion from the figures. ’ ’ Hart,

Murder and the Principles of Punishment: England

and the United States, 52 N w .U .L .R ev. 433, 457

(1957).

The reasons why these statistical studies do not

prove that capital punishment is not a superior de

terrent have been frequently pointed out. E.g., R oyal

Commission on Capital P unishment, R eport 1949-

1953, Cmd. No. 8932, at 22-24, W 62-67 (1953); 2

W orking P apers of the National Commission on R e

form of F ederal Criminal Laws 1354 (1970); Gibbs,

Crime, Punishment, and Deterrence, 48 Sw. Soc. Sci.

— 15 —

Q, 515, 516 (1968). It is very difficult to be sure that

all relevant variables other than capital punishment

can be eliminated. Goldberg & Dershowitz, Declaring

the Death Penalty Unconstitutional, 83 H arv.L.Rev.

1773, 1796 n. 105 (1970). Florida, R eport of the Spe

cial Commission for the Study of A bolition of Death

P enalty in Capital Cases 14 (1965); Ohio Legislative

Service Commission, Capital P unishment 38 (Staff

Research Report No. 46, 1961). It appears quite likely

that homicide rates per 100,000 of population are too

crude an instrument to reflect all the cases in which

the threat of a death sentence has had a deterrent effect.

Model P enal Code 64-65 (Tent. Dr. No. 9, 1959).

A leading opponent of capital punishment, Profes

sor Hugo A. Bedau, has given an example that shows

why the statistical findings are not inconsistent with

the existence of a deterrent effect for capital punish

ment.

Data reported below in Professor Sellin’s article

shows that the ten-year average of annual homcide

rates in Ohio fell during the 1920’s from 7.9 per

100,000 of population to 3.8 in the 1950’s. Yet if

the death penalty had been abolished in Ohio at

the beginning of this period and if (let us suppose)

abolition had been followed by a dozen or so more

murders each year thereafter, the general homicide

rate would have decreased almost exactly as in

fact it has, and at no time would the rate for any

given year be more than a tenth of one per cent

greater than it has been. Thus, while we could

truthfully say that the abolition of the death pen

alty in Ohio had been followed by a decrease in

the general homicide rate, it would also have been

true that abolition resulted in an increase in the

total number of murders, and this despite the eon-

— 16 —

stancy of the ratio of total homicides to murders

(except in the first year after abolition).

B edau, The Death P enalty in A merica 265-266 (2d

ed. 1967). H. L. A. Hart has made the same point based

on British statistics. Hart, Murder and the Principles

of Punishment: England and the United States, 52

Hw .ILL.Rev. 433, 457 (1957).

Of course capital punishment is not a perfect de

terrent. Murder, rape, and other serious crimes con

tinue to take place despite the threat of death. We can

number the cases in which the death penalty has failed

as a deterrent. We cannot number its successes. R oyal

Commission on Capital P unishment, R eport 1949-

1953, Cmd. No. 8932, at 18,1 55 (1953). There are many

human activities that involve risking one’s life in which

some persons, whether for the sake of a livelihood, from

recklessness, from pride, or from devotion to a cause,

are willing to run the risk while others refrain because

they do not wish to undertake the risk. Cohen, L aw

W ithout Order 49-50 (1970).

There is some objective evidence of criminals who

have been deterred by the existence of the death pen

alty: robbers who have said that they used simulated

guns or empty guns rather than take a chance of kill

ing someone and being condemned to death; an escaped

convict who released his hostages at the state line be

cause he was afraid of the death penalty for kid

napping in the neighboring state; and other instances

of this kind. 2 W orking P apers of the National Com

mission on R eform of F ederal Criminal L aws 1356

(1970); B edau, T he Death P enalty in A merica 266-

267 (2d ed. 1967). In addition, experienced law en

forcement officers are virtually as one in their con

17—

viction that the death penalty is a superior deterrent.

See, e.g., the statements of J. Edgar Hoover and of

Chief Edward J. Allen, reprinted inBEDAU, T he D eath

P enalty in A meeioa 130-146 (2d ed. 1967); 2 W orking

P apers of the National Commission on R eform of

F ederal Criminal L aws 1356 (1970). It is easy enough

to seek to dismiss these as mere “ impressionistic opin

ions” (Aikens Br. 60). Others have thought that they

could not “ treat lightly the considered and unanimous

views of these experienced witnesses, who have had

many years of contact with criminals.” R oyal Com

mission on Capital P unishment, R eport 1949-1953,

Cmd. No. 8932, at 21,1 61 (1953).

The conclusion that the Royal Commission drew on

this issue seems an appropriate one in the present state

of knowledge:

The general conclusion which we reach, after care

ful review of all the evidence we have been able

to obtain as to the deterrent effect of capital pun

ishment, may be stated as follows. Prima facie the

penalty of death is likely to have a stronger effect

as a deterrent to normal human beings than any

other form of punishment, and there is some evi

dence (though no convincing statistical evidence)

that this is in fact so. But this effect does not op

erate universally or uniformly, and there are many

offenders on whom it is limited and may often be

negligible. It is accordingly important to view this

question in a just perspective and not to base a

penal policy in relation to murder on exaggerated

estimates of the uniquely deterrent force of the

death penalty.

Id. at 24,1 68.

I f this Court were to reach the same conclusion as

did the Royal Commission, it would have to say that

— 18 —

a legislature could rationally choose to retain the death

penalty because it believed that to some extent that

penalty is a more effective deterrent than any other

form of punishment. But that would also be the result

here even if there was less evidence than there is to

support a finding of deterrent effect. In connection

with whether obscenity has a harmful effect, the Court

has noted that there is a growing consensus that while

a causal link has not been demonstrated it has not been

disproved either. In that situation, the Court said, leg

islation that proceeds on the premise that obscenity

is harmful has a rational basis. Ginsberg v. New York,

390 TJ.S. 629, 641-643 (1968). At least as much can be

said for legislation premised on the deterrent effect

of capital punishment.

The legislative judgment inherent in provisions

for the death penalty may he open to question, but

that hardly seems enough to make it impermissible.

One may wonder whether a constitution “ that does

not enact Mr. Herbert Spencer’s Social Statics”

can fruitfully be thought of as enacting Mr. Thor-

sten Sellin on the death penalty.

Packer, Making the Punishment Fit the Crime, 77

H arv.L.Rev. 1071, 1079-1080 (1964).

There is, however, another argument against the

constitutionality of capital punishment that is men

tioned by petitioner in this ease (Branch Br. 12) and

that is central to the position of the petitioners in the

companion cases. We have shown earlier that a sub

stantial portion of the public and the great majority

of legislatures accept death as a penalty. The argument

now to be considered concedes that society tolerates

having death penalty statutes on the books but that

it would not tolerate their widespread use. It is as

19

serted that death is a cruel and unusual punishment

because contemporary standards of decency, univers

ally felt, would condemn the use of death as a penalty

if the penalty were uniformly, regularly, and even-

handedly applied to all persons found guilty of a crime

for which death is made a possible penalty or even to

a reasonable proportion of them (Aikens Br. 24).

With the utmost respect for the able and dedicated

counsel who have put forward this argument, we sub

mit that it has even less persuasive force than do the

more usual arguments against capital punishment that

have already been considered. The present argument

relies, in the first place, on an assumption that is un

documented and that many persons would reject.

W e are told that “ standards of decency, universally

felt,” would condemn the regular use of the death pen

alty (Aikens Br. 24). Again it is said that if 184

criminals were to be executed in 1971, as happened in

1935, “ it is palpable that the public conscience of the

Nation would be profoundly and fundamentally re

volted * * *” (Aikens Br. 26). At another place it is

said that there is “ an overwhelming national repulsion

against actual use of the penalty of death” (Aikens

Br. 42), and that it is “ a punishment which, if applied

regularly, would make the common gorge rise” (Aikens

Br. 54). Finally Aikens asserts that “ if it were usually

used, it would affront universally shared standards of

public decency” (Aikens Br. 61). There is a similar

suggestion from the present petitioner (Branch Br.

12).

The various petitioners offer no evidence whatever

in support of this assertion. It is wholly possible that

a substantial portion of the public would think the

— 20 —

development hypothesized by petitioners a salutary one

and a constructive step in the direction of a no-non

sense “ war on crime.” It is wholly possible that, as

Warden Clinton Duffy has lamented, “ the public

doesn’t care” one way or the other. D uffy, 88 Men

and 2 W omen 258 (1962). An unsupported assertion

remains only an assertion though it is iterated six

times in varying and forceful language.

Even if petitioners were right in their supposition,

it is difficult to see what that would establish as a mat

ter of law. The public may think it wise to retain the

death penalty on the books as a warning to all would-be

murderers and rapists, even though application of the

penalty is reserved for only the most serious offenders.

It is then left to the sentencing authority, commonly

the jury, in each particular case to “ express the con

science of the community on the ultimate question of

life or death.” Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510,

519 (1968). That petitioners do not trust juries to

perform this function and believe that a death sentence

is given to a small number of persons arbitrarily chosen

from a much larger group who might have been sen

tenced to death is merely another form of the argument

that was made and rejected in McGautha v. California,

402 U.S. 183 (1971).

It can be conceded, as the figures of the Bureau of

Prisons presented by the petitioners show, that there

has been a decreasing number of executions in the last

40 years, although the figures for the last decade are

entitled to little weight on this point. In addition

to the de facto moratorium that has existed for the

last four years while cases challenging the procedures

for and the constitutionality of capital punishment

21 —

were pending in this Court, earlier cases such as Mapp,

Miranda, and others, which limited the kinds of evi

dence that can be heard in criminal cases, undoubtedly

aborted prosecutions or required vacation of convic

tions that would otherwise have led to an execution,

and cases such as Fay, Townsend, and Sanders en

larged the possibilities for delay in carrying out a

death sentence by collateral attacks on convictions. A

decade ago nearly one person per week was being exe

cuted in the United States. It hardly seems right to call

something that happened that frequently “ an almost

indescribably uncommon event” (Aikens Br. 38). The

conscience of the community, as expressed by those

who impose sentence in capital cases, has taken an

increasingly rigorous view of the extreme cases in

which the death penalty will be used. It has shown no

disposition to abandon the death penalty entirely. Re

taining it on the books for classes of the most serious

crimes and applying it to the most extreme of the cases

that fall within those classes is consistent with both the

conscience of the connnunity and the Eighth Amend

ment to the Constitution.

II. Capital Punishment in Rape Cases Is Justified by

the Seriousness of the Crime and Is Not “ Cruel and

Unusual” Within the Meaning of the Eighth Amend

ment.

The argument is made in this case and in Jackson

that even if death is a constitutionally permissible

punishment for some crimes it is cruel and unusual

for some or all rapes. The Jewish religious and civic

organizations that are amici here contend that death

is an unconstitutional punishment for any rapes that

do not result in death (Synagogue Council Br. 13).

— 22 —

Petitioner in the present ease argues that death is un

constitutional as punishment in rape eases “ where

life is not taken nor endangered” (Branch Br. 28) or

“ where no life has been taken or seriously endangered”

(Branch Br. 29). The first of those formulations,

“ when the victim’s life is neither taken nor endan

gered,” was held to be the point at which the Con

stitution prohibits a death sentence for rape by a

majority of the Fourth Circuit, speaking through

Judge Butzner, in Ralph v. Warden, Maryland Peni

tentiary, 438 F.2d 786, 793 (4th Cir. 1970). Chief

Judge Haynsworth, concurring in the result in that

decision, would allow a death sentence “ if the victim

suffered grievious physical or psychological harm

whether or not it clearly appeared that her life had

been endangered.” Id. at 794. I f a rape results in loss

of life it would be murder under the felony-murder

doctrine and so it adds nothing to speak of allowing

the death penalty for rapes in which a life has been

taken. The various arguments then are that capital

punishment is unconstitutional in any rape case, or

in rape eases in which the victim’s life has not been

seriously endangered, or in which her life has not

been endangered at all, or in which she has not suf

fered grievous physical or psychological harm.

The argument proceeds from the premise that the

Eighth Amendment bars both those punishments that

are inherently cruel and those that are cruelly ex

cessive. See Comment, Revival of the Eighth Amend

ment: Development of Gruel-Punishment Doctrine by

the Supreme Court, 16 Stan.L.Bev. 996 (1964). There

is ample support for the notion that the Amendment

prohibits inherently cruel punishments— Wither son v.

Utah, 99 U.S. 130, 135-136 (1879) ; In re Kemmler,

— 28

136 IJ.S. 436, 447 (1890) ; State ex rel. Francis v.

Resweber, 329 U.S. 459, 464 (1947)—though the death

penalty has never been thought to run afoul of this

aspect of the Amendment and, for the reasons set

forth in Point One of this Brief, should not be held

to do so. The notion that the Amendment also bars

cruelly excessive punishments is derived primarily

from Weems v. United States, 217 U.S. 349 (1910),

though it is supported also by the dissents in O’Neil v.

Vermont, 144 U.S. 323, 340, 370-371 (1892), and by

the decisions of the Court in Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S.

86 (1958) and perhaps Robinson v. California, 370

U.S. 660 (1962). There is much to be said for the idea

that the Weems case has been misread and that it is

much closer to the conventional view that cruel and

unusual punishment is a matter of mode of punish

ment rather than proportion. Packer, Making the Pun

ishment Fit the Crime, 77 H arv.L .R ev. 1071, 1075

(1964). Nevertheless we assume for purposes of this

argument that a punishment disproportionate to the

gravity of the offense might for that reason be held

to be cruel and unusual.

If, as is argued in Point One, a legislature could

reasonably find that capital punishment has some de

terrent effect on crime, it could reasonably find that

it has some deterrent effect on rape. Though it may

be, as argued by petitioner (Branch Br. 26), that the

nature of sex crimes is such that any punishment has

little or no deterrent value, “ very little is actually

known about the relationship between rape and penal

sanction.” Schwartz, The Effect in Philadelphia of

Pennsylvania’s Increased Penalties for Rape and A t

tempted Rape, 59 J. Grim. L. C. & P. S. 509, 515

(1968). The statistical studies on the effect of capital

_ 2 4 —

punishment have been confined to homicide and there

are no figures one way or the other on whether capital

punishment deters rapes. Indeed petitioner’s belief

that sex offenders cannot be deterred by threat of any

punishment and his related belief that there is little

or no recidivism among rapists (Branch Br. 26)—a

belief that is not as widely accepted as he suggests, see

M acdonald, R ape— Offenders and T heir V ictims 314

(1971); Gebhard, Gagnon, P omeroy & Christenson,

Sex Offenders 193 (1965)—would, if accepted, lead

quite logically to the conclusion he draws, “ that- rapists

need little rehabilitation or punishment” (Branch Br.

28). Society would overwhelmingly disagree.

The position of the Jewish religious organizations,

that death is never a constitutional punishment for any

rape, has the merit of being a clear and workable test.

It also has a certain attractive logic. The Biblical ref

erence to a life for a life, Deut. 19:21, surely was not

meant restrictively. The death penalty was also called

for in the ancient law for adultery, Lev. 20:21, bes

tiality, Ex. 22:18, and rape of a betrothed woman,

Deut. 22:15. But undoubtedly there is appeal to the

notion that just retribution permits the taking of a

life only when life has been taken.

But the Eighth Amendment did not enact the Book

of Deuteronomy and the difficulty is in establishing that

death is so “ greatly disproportioned” to any rape, re

gardless of its circumstances, that a legislature acts

unconstitutionally if it permits some rapists to be

executed. The several formulations of petitioner and

of the judges of the Fourth Circuit seek to distinguish

among rapes for which death is an appropriate pen

alty and those for which it is not. The Jewish re-

— 25

ligious organizations reject any distinction of this kind.

Thus they must take the view that there is no rape

in which the victim survives for which the criminal

can he put to death. No matter how seriously the vic

tim’s life was endangered, no matter how revolting and

barbarous the circumstances of the crime, no matter

how grievous the permanent physical and psychological

harm visited on the victim, so the argument runs, death

would be so excessive a penalty that the Constitution

forbids it.

It may be asked where in the Constitution this re

striction on the state and federal governments can be

found. W e have conceded for the purposes of argument

that a cruelly excessive punishment may be uncon

stitutional but there is ambiguity in speaking of a

punishment as being proportioned to a crime. The

punishment may be considered “ in relation to the harm

actually resulting from a criminal act, to the risk of

harm caused by the actor, to the degree of temptation

he faced, or to his 4moral fault.’ ” Note, The Gruel and

Unusual Punishment Clause and the Substantive

Criminal Law, 79 H arv.L.Rev. 635, 636 (1966). To

draw a line between rapes resulting in death and other

murders, on the one hand, and rapes not resulting in

death, on the other, requires looking to the first of

these concepts to the exclusion of the other three. Other

observers who have taken a broader outlook have

thought that “ capital punishment for rape is justi

fiable, if capital punishment is ever justifiable, as a

matter of legislative choice because of the danger to

life and limb as well as to other interests that a forcible

sexual attack may involve.” Packer, Making the Pun

ishment Fit the Crime, 77 H arv.L.Rev. 1071, 1077

26

(1964) ; see also Note, 79 H arv.L.Rev. 635, 642-643

(1966).

Society lias always regarded forcible rape as among

the most serious and most reprehensible of crimes. It,

along with willful homicide, aggravated assault, and

robbery are

the most threatening and the most strongly con

demned in the entire criminal calendar. # * These

four offenses are supremely threatening for dif

fering reasons, but in each case one’s physical

security is placed at the mercy of a person intent

on violating that security. Nothing makes either

the victim or the community feel more helpless

than an occasion on which someone has used force

to work his will on another. Violent injury or

the threat of it is the brute negation of the mini

mum that all of us—from the most self-sufficient

to the most dependent—expect from life in organ

ized society.

P acker, T he L imits op the Criminal Sanction 297

(1968). Even where the death penalty is not imposed

society shows the seriousness with which it considers

rape by the length of sentences it imposes for this

crime. The average time served before release is longer

for rapists, than for men convicted of manslaughter,

robbery, aggravated assault, or any offense other than

murder. M acdonald, R ape— Offenders and T heir V ic

tims 298 (1971). There is another, less agreeable, in

dication of how society views rape. Between 1872 and

1951, 1,198 persons suspected of rape or attempted

rape were lynched in the United States. Id. at 301.

The incidence of rape is sharply rising. In the last

decade the number of rapes has increased 121% and

the rate in relation to the population has increased

27 —

95%. In 1970 36 out of every 100,000 females in the

country was a reported forcible rape victim and it

is well understood that, because of fear and embarrass

ment, this offense is probably one of the most under

reported crimes. FBI, U niform Crime R eports for the

U nited States 1970 14 (1971). The past decade is not

unusual in this respect. Rape is the only crime of

violence that has shown a clear tendency to increase in

frequency over the last century. M acdonald, R ape—

Offenders and T heir V ictims 25 (1971). Given these

figures, it would be doctrinaire in the extreme to say

that Congress and the legislatures of 17 states are

acting unconstitutionally when they provide the death

penalty in an effort to deter all forcible rapes and im

pose it in those cases in which a lesser penalty would not

be sufficient for retribution.

It is appropriate to consider here the argument that

death for rape is cruel and unusual because the death

penalty is carried out on Negro rapists far more often

than white rapists and thus is “ a thinly veiled attempt

to legitimize racial homicide” (Branch Br. 19). That

argmnent comes in at this point because, if it has any

validity, it must be valid against any use of the death

penalty for rape. Surely it would not be permissible for

a state to legitimize racial homicide against those rap

ists who have seriously harmed their victim or endan

gered their lives but not against other rapists.

It would seem that the racial argument is more prop

erly directed to the Equal Protection Clause than to

the Cruel and Unusual Punishment Clause. Never

theless we will assume that it has sufficient relation to.

the Eighth Amendment to be within the limited grant

of certiorari in this case.

28 —

Undoubtedly the statistics are suggestive that juries

have taken race into account in imposing the death pen

alty for rape. Figures provided counsel by the Texas

Department of Corrections show that 97 persons have

been executed for rape in Texas since 1924. Of these

14 were white, 80 were black, and three were Latins.

Eight of the 42 persons now under sentence of death

in Texas were convicted for rape. Of these one is

white, five are black, and two are Latins. See also

Koeninger, Capital Punishment in Texas, 1924-1968,

15 Crime & D el. 132 (1969).

We have no doubt but that race is “ constitutionally

impermissible” as a consideration in sentencing con

victed offenders, McGautha v. California, 402 U.S.

183, 207 (1971), though we think that this is true

of all sentences:, and not merely of death sentences,

and that it is the result of the Equal Protection Clause

rather than of the Eighth Amendment as absorbed

into the Due Process Clause. Clearly the figures on

numbers of executions by race are suggestive that race

has been considered, but this has not been a problem

confined to rape cases or to use of the death sentence.

Professor Henry Bullock’s sophisticated study of

3,644 persons under prison sentence at Huntsville

would support a conclusion that in the past race has

played a part in sentencing in Texas, with Negroes

receiving shorter sentences than whites for some of

fenses and longer sentences for others. Bullock, Sig

nificance of the Bacial Factor in the Length of Prison

Sentences, 52 J. Crim . L., C. & P. S. 411 (1961). In

understanding this historical fact it cannot be for

gotten that until 1954 segregation of the races was le

gally required in Texas. At a time when the law pro

hibited racial intermingling even in a schoolroom or

29 —

on a bus, and when miscegenation was a crime, it is

hardly surprising that an interracial offense, and par

ticularly an interracial rape, was perceived as an espe-

cially traumatic event and an especially serious breach

of the good order of the state.

In understanding these figures from the past another

fact must be taken into account. The rape rate is much

higher among Negroes than among whites. Studies

both in Denver and Philadelphia, based on figures

that eliminated any possibility of racial discrimination

on the part of .judges and jurors, showed in each in

stance that the rape rate was 12 times as high among

Negroes: as among whites. M acdonald, R ape— Offend-

ees AND T heib Y ictims 51-54 (1971). That this is so

says nothing about comparative morality of different

races. It may well be a function of poverty rather

than of race. “ * * * [T]he rich kid can use flowers,

candy, wining and dining and a shiny automotive

super-phallus to ‘ seduce’ the girl whom the slum kid

‘ rapes.’ Seney, The Sibyl at Cumae—Our Criminal

Law’s Moral Obsolescence, 17 W ayne L.Rev. 777, 793

n. 76 (1971). I f the disparity between the incidence of

rape among whites and Negroes was one to twelve

in Texas, as it was found to be in Denver and Phila

delphia studies, then a disparity of less than one to

six in the numbers executed is less persuasive of dis

criminatory practices than the figures would seem at

first blush.

Those courts that have considered the statistical

argument about death sentences in rape cases have

found them insufficient to show that the Negro de

fendants who were before them received the death

penalty because of their race. Ralph v. Warden, Mary

— 30 —

land Penitentiary, 438 F.2d 786, 793 n. 24 (4th Cir.

1970) ; Maxwell v. Bishop, 398 F.2d 138, 149 (8th Cir.

1968), vacated on other grounds 398 U.S. 262 (1970).

Even counsel who has been most imaginative in mak

ing and seeking to document this argument concedes

that an irrefutable statistical showing that a particu

lar state has discriminated on racial grounds in the

administration of the death penalty is difficult to estab

lish, because the number of death sentences is so ex

ceedingly small in comparison to the number of factors

that may properly be considered at every stage of the

criminal process in deciding whether to impose capital

punishment (Aikens Br. 53). In any event, as the

Eighth Circuit noted in the Maxwell case, “ improper

state practice of the past does not automatically in

validate a procedure of the present.” Ibid.

If, for the reasons we have stated, the Constitution

is not a bar against capital punishment for any rape

case, are there some rapes that are sufficiently inof

fensive that to impose death for them is grossly dis

proportionate to the crime and, for that reason, cruelly

excessive? Interestingly the Texas Court of Criminal

Appeals has held that there are. In Calhoun v. State,

85 Tex.Cr. 496, 503, 214 S.W. 335, 338 (1919), that court

said:

We take it to be clear that the extreme penalty

should only be inflicted in an extreme case, and

we do not believe this is such a case. Our Constitu

tion (section 13 of the Bill of Bights) forbids the

infliction of excessive fines or cruel or unusual

punishment.

Though the Calhoun case has never been overruled

and is even occasionally cited, it is very doubtful that

31 —

it represents Texas law. It has never actually been

followed and it is quite plain on the face of the opinion

that the court simply did not believe the testimony of

the complaining witness. Since it could not reverse

on that ground, it hunted for some seemingly plausible

ground on which it could save the life of a defendant

whom the court thought to be not guilty. In fact it

sent the case back for a new trial, at which the state

had already predicted it could not get a conviction,

rather than merely setting aside the sentence.

Petitioner argues, and the Fourth Circuit has held,

that “ the death sentence is so disproportionate to the

crime of rape when the victim’s life is neither taken

nor endangered that it violates the Eighth Amend

ment.” Ralph v. Warden, Maryland Penitentiary, 438

E.2d 786, 793 (4th Cir. 1970). The dissenting judges

in the Fourth Circuit pointed out the extreme impre

cision of the term “ endangered.” Id. at 796. Professor

Packer also has questioned how a court is to tell

in any given case whether human life was “ endan

gered.”

There is a sense in which life is always endangered

by sexual attack, just as there is a sense in which

it is always endangered by robbery, or by burglary

of a dwelling, or by any physical assault. The

threat of violence too is not the less a threat for

being conditional, and violence always carries the

possibility of a fatal outcome.

Packer, Making the Punishment Fit the Grime, 77

H arv.L.Rev. 1071, 1077 (1964). This is consistent with

all that is known about rape and about rapists.

Dr. Kinsey’s associates have found in their study

that in 40% of the cases the rapists made threats of

- 3 2 - —

a major sort, such as of serious physical damage or

threats of injuring the victim’s children. Gebhard,

Gagnon, P omeroy & Christenson, Sex Offenders 196

(1965). The most common type of rapist is

the assaultive variety. These are men whose be

havior includes unnecessary violence; it seems, that

sexual activity alone is insufficient and in order

for it to be maximally gratifying it must be

accompanied by physical violence or by serious

threat. In brief, there is a strong sadistic element

in these men and they often feel pronounced hos

tility to women (and possibly to men also) at a

conscious or unconscious level. They generally do

not know their victim; they usually commit the of

fense alone, without accomplices; preliminary at

tempts at seduction are either absent or extremely

brief and crude; the use of weapons is common;

the man usually has a past history of violence; he

seemingly selects his victim with less than normal

regard for her age, appearance, and deportment.

Lastly, there is a tendency for the offense to be

accompanied by bizarre behavior including unnec

essary and trivial threats.

Id. at 197-198. Other studies have noted that rape often

does lead to murder. Williams, Rape-Murder, in Sex

ual B ehavior and the L aw 563 (Slovenko ed. 1965).

Dr. John Macdonald’s recent comprehensive examina

tion of rapes reports that in order to secure submis

sion and compliance, the rapist will often threaten or

physically assault his victim, and that even in the

absence of threats or blows the offender may convey to

his victim by his facial appearance and general be

havior the impression that resistance will lead to vio

lence. M acdonald, B are— Offenders and T heir V ic

tims 63 (1971). In a study he made of 200 rape victims

in Denver almost half were either struck with a fist

— 33 —

or choked. Id. at 64. He finds, too, that the force nsed

to subdue the woman may he fatal, though the rapist

did not intend this, since pressure on the neck of the

victim, though insufficient to cause strangulation, may

cause death from reflex causes. Id. at 180.

Whether or not the Fourth Circuit test is a usable

standard can profiably be considered in the light of

the facts of the present case. Was Mrs. Stowe’s life

endangered when Elmer Branch broke into her rural

house in the dead of night and raped her ? Defendant,

who was 20 or 21 years old, is virtually the prototype

of the “ assaultive variety” of rapist described by Gfeb-

hard and his colleagues. He committed the offense

alone, with no preliminary attempt at seduction, and

he selected his victim without regard to her age. The

events following the assault are characterized by his

own counsel as “ bizarre” (Branch Br. 3). He used

brute force to accomplish his will with Mrs. Stowe

(A. 19). She was 65 years old and was unable to do

anything because “ he was just so strong: I have never

seen a man with that kind of power in his hands.

* * *” ( A. 19). Prior to accomplishing penetration

he had Mrs. Stowe’s head hanging off the bed while

he pressed down harder and harder on her throat (A.

19). After the attack she was “ coughing and choking.

He had hurt my throat and I was hurting all over

really. My throat was hurting and I couldn’t hardly get

my breath * * *” (A. 22). When Branch finally left

he told her he would kill her if she told about the

attack (A. 23).

Was Mrs. Stowe’s life endangered? Was there a

risk that he might have suffocated her had she con

tinued to resist? Was there a risk that the pressure on

— 34 —

lier neck might cause death from reflex causes? I f he

had heard her slipping out the hack door immediately

after he went out the front and had seen her running

to her son’s house, was there danger that he would have

carried out his threat and have killed her? These are

the kinds of questions that must be answered in this and

every other rape case if the Fourth Circuit test should

he adopted as a constitutional rule. One could reason

ably answer each of these questions in the affirmative,

given what we know about rape and rapists, but if

we do so the protection supposedly afforded by the

Fourth Circuit rule is wholly illusory. Indeed similar

questions could just as well be answered in the affirma

tive on the facts of the Ralph case itself. But how can

the questions possibly or rationally be answered in the

negative? I f the line is a constitutional one, as the

Ralph holding and the argument here would require,

they will be questions that must ultimately be answered

by appellate judges, who would be required to de

cide in each instance whether a particular set of facts

came within or without the area in which the victim’s

life was “ endangered” and the Constitution would al

low a death sentence to stand. It seems quite odd that

the Constitution should require appellate judges to

speculate on what might have happened though, by

hypothesis, it did not.

Would the ease be in a different posture if the prose

cutor had asked Mrs. Stowe if she thought that her

life was, in danger and she had said: “ Oh, yes. I felt

that if I didn’t give in he would certainly kill me” ?

Or if she had said: “ I f he had kept his arm on my

throat a minute longer I would have suffocated.” I f

so, any protection from the Fourth Circuit rule would

again be illusory. Prosecutors would ask the ritual

— 35

questions to establish that the victim’s life was en

dangered just as they now put a ritual question to

establish penetration (A. 28).

Would this be a different case if, at the outset of

the encounter, Branch had said: “ I ’ll show you what

I want and I ’ll kill you, if I have to, to get it” ? (Cf.

A. 18.)I f so, why? I f so, what in the Eighth Amend

ment requires the drawing of such subtle and meaning

less distinctions? The Fourth Circuit test is neither

workable, logical, nor required by the Eighth Amend

ment. A legislature may reasonably believe, with Pro

fessor Packer, that “ there is a sense in which life is

always endangered by sexual attack.”

In the Ralph case Chief Judge Haynsworth chose

a different test. He though it was decisive that the vic

tim’s doctor had testified that she had suffered no last

ing physical or psychological harm, and could find

no bar in the Eighth Amendment against the im

position of the death penalty for rape if the vic

tim suffered grievous physical or psychological

harm whether or not it clearly appeared that her

life had been endangered.

438 F.2d at 795.

This appears to point to a more objective inquiry

than does the “ endangered” test and Chief Judge

Haynsworth is certainly right that “ the nature, degree

and duration of the harm have long been recognized

as important criteria in determining the appropriate

ness of punishment.” Ibid. But it does not follow from

this that they are constitutionally-imposed criteria.

The victim of any rape, as Chief Judge Haynsworth

himself noted, “ suffers harm and great indignity.”

Ibid. Serious physical harm can be recognized and

_ 3 6 —

measured. Lasting psychological harm is less easy to

identify and may he even more grievous. In the present

case, for example, Mrs. Stowe is what Dr. Seymour L.

Halleek refers to as an “ accidental” victim, one who

did not know her attacker and who made some effort to

resist the assault.

Such a woman has undergone an experience in

which she is aware of overwhelmingly angry feel

ings but is helpless in dealing with them. She re

peatedly searches her own motivations to discover

if there was something she might have done to pre

vent the attack. Often she blames herself for hav

ing neglected a minor defensive effort that she

feels might have been protective. She is uncertain

as to her role as a woman and such a role does

appear to her at that moment as a degraded and

helpless one. She wonders if she will again he at

tracted to men or interested in normal sexual

relations.

A wide variety of pathological reactions may de

velop following sexual assault. Women with pre

viously vulnerable personalities are likely to de

velop neurotic symptoms including anxiety at

tacks, phobias, hypochondriasis or depression. Oc

casionally psychotic reactions are seen. Less com

monly transient characterological difficulties such

as excessive drinking or promiscuity appear. The

previously well adjusted woman may also become

disturbed. It is indeed difficult to conceive of any

woman going through this experience without de

veloping some symptoms. While many symptoms

may be transient and not incapacitating those pa

tients who relate chronic symptoms to previous

sexual assault suggest that this is not always the

case.

The patient’s guilt following an attack is often

intense. Psychiatrists believe that most normal

— 37 —

women experience masochistic fantasies at some

times in their lives. The victim may, therefore, fear

that she might have willingly invited or pro

voked the attack, She is then tortured with self

accusation.

Halleck, Emotional Effects of Victimization, in Sex

ual B ehavior and the L aw 673, 675-676 (Slovenko ed.

1965). Which of these ill effects is sufficiently “ griev

ous” that the death penalty could he imposed? Will

victims, notoriously reluctant to complain of rape be

cause of the embarrassment it causes them, be even

more reluctant to do so if they are to be required to

take the stand and he examined about whether they

are interested in normal sexual relations or whether

they are experiencing masochistic fantasies? Given

the already common and unavoidable practice of try

ing the prosecutrix, can a rule whose harmful effect

is directly proportional to the victim’s susceptibility to

psychological damage, be sound?