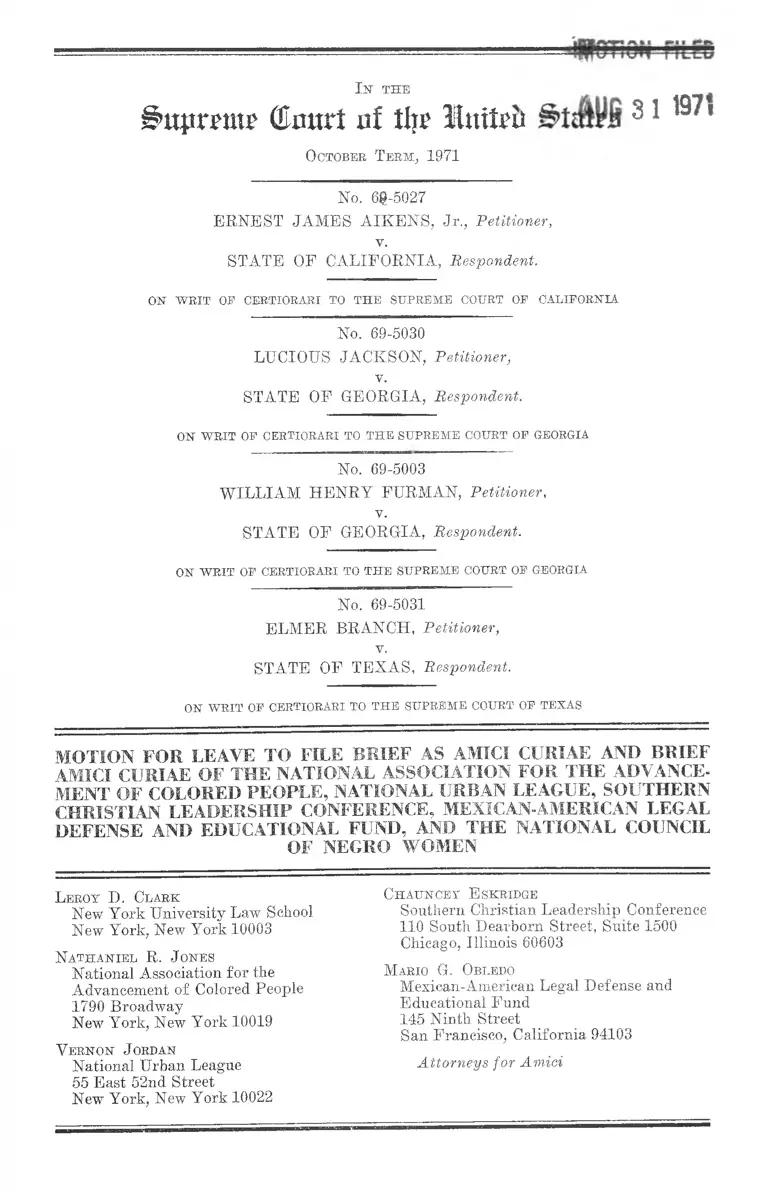

Aikens v. California, Furman v. Georgia, Jackson v. Georgia, and Branch v. Texas Motion for Leave to File Brief as Amici Curiae and Brief Amici Curiae of the NAACP, National Urban League, SCLC, MALDEF, and National Council of Negro Women

Public Court Documents

August 31, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Aikens v. California, Furman v. Georgia, Jackson v. Georgia, and Branch v. Texas Motion for Leave to File Brief as Amici Curiae and Brief Amici Curiae of the NAACP, National Urban League, SCLC, MALDEF, and National Council of Negro Women, 1971. 37d35914-ac9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1dc185a4-ce7d-4aaa-b0ab-16e9da2b4da5/aikens-v-california-furman-v-georgia-jackson-v-georgia-and-branch-v-texas-motion-for-leave-to-file-brief-as-amici-curiae-and-brief-amici-curiae-of-the-naacp-national-urban-league-sclc-maldef-and-national-council-of-negro-women. Accessed February 26, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e ^

g>ttpr?nt? (Eourt at % Huifrii 81 *97*

October Term, 1971

No. 68-5027

ERNEST JAMES ATHENS, Jr., Petitioner,

v.

STATE OF CALIFORNIA, Respondent.

ON W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OP CALIFORNIA

No. 69-5030

LUCIOUS JACKSON, Petitioner,

v,

STATE OF GEORGIA, Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF GEORGIA

No. 69-5003

WILLIAM HENRY FURMAN, Petitioner,

v.

STATE OF GEORGIA, Respondent.

ON W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO TH E SUPREME COURT OF GEORGIA

No. 69-5031

ELMER BRANCH, Petitioner,

v.

STATE OF TEXAS, Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF TEXAS

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AS AMICI CURIAE AND BRIEF

AMICI CURIAE OF THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCE

MENT OF COLORED PEOPLE, NATIONAL URBAN LEAGUE, SOUTHERN

CHRISTIAN LEADERSHIP CONFERENCE, MEXICAN-AMERICAN LEGAL

DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, AND THE NATIONAL COUNCIL

OF NEGRO WOMEN

Leroy D. Clark

New York University Law School

New York, New York 10003

Nathaniel R. J ones

National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People

1790 Broadway

New York, New York 10019

Vernon J ordan

National Urban League

55 East 52nd Street

New York, New York 10022

Chauncey E skridge

Southern Christian Leadership Conference

110 South Dearborn Street, Suite 1500

Chicago, Illinois 60603

Mario G. Obledo

Mexican-American Legal Defense and

Educational Fund

145 Ninth Street

San Francisco, California 94103

Attorneys for Amici

I N D E X

PAGE

Motion for Leave to File Brief Amici Curiae ...............2-M

Brief Amici Curiae......................................................... 1

Statement of Interest.............................................. 2

Summary of Argument............................................ 7

Argument .................................................... 8

I. Pre-1935 History of the Racially Discrim

inatory Use of Formal and Informal Cap

ital Punishment by Whites Against Non

whites ......................................................... 8

A. Slavery 1619-1865 ....................... 8

B. Lynching and Vigilantism 1882-

1935 ................................................ 11

II. The Disproportionate Numbers of Non-

White Persons Executed by Formal Cap

ital Punishment Constitutes Cruel and

Unusual Punishment in Violation of the

Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments of

the Constitution ......................................... 13

Conclusion ....................................... 23

Appendix A:

Pre-Civil War History of Punishment for Rape

in Southern States and Washington, D.C...... ........ la

T able oe A uthobities

Cases:

Douglas v. California, 372 U.S. 353 (1963) ................. 21

Gideon v. Wainright, 327 U.S. 335 (1963) ................... 21

11

PAGE

Maxwell v. Bishop, 398 Fed. 2d 138 (1968) ................. 16

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1879) .......... 18

Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86 (1958) ............................19, 20

Weems v. United States, 217 U.S. 399 (1910) ..........19,20

Wilkerson v. Utah, 90 U.S. 130, 135-136 (1879) .......... 19

A uthorities

Bedau, The Death Penalty in American Law (paper

back ed.) (1967) 411-413 ...... .................................... 18

Du Bois, The Suppression of the African Slave Trade

to the United States of America (1954) p. 6 ..........9,10

Franklin, From Slavery to Freedom—A History of

Negro Americans, (1966) 3rd ed., 58-59 ................. 8

Graham and Gurr, Violence in America—Historical

and Comparative Perspectives—A Stall Report to

the National Commission on the Causes and Pre

vention of Violence, Vol. I (1969) 39 ................. 11,12,13

Greenberg, Race Relations and American Law (1959)

320 .............................................................................12,18

Jordan, White Over Black (1968) 106 ........................ 10

Myrdal, An American Dilemma ................................... 14

Stamp, The Peculiar Institution—Slavery in the Ante-

Bellum South (1956) 210 .......................................... 9

Ill

PAGE

Tannenbaum, Slave and Citizen (1947) 28-29 .......... 8

Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil

Disorders (1968) 102 ..............................................12,14

United States Department of Justice, Bureau of Pris

ons, National Prisoner Statistics No. 45, Capital

Punishment 1930-1968 (August 1969) 7 ................... 20

I n the

Ihtprrmr Court of tfjr Initrft States

October T erm, 1971

No. 69-5027

E rnest J ames A ikens , J r., Petitioner,

v.

S tate of California, Respondent.

ON W R IT OF CERTIO RA RI TO T H E S U P R E M E COU RT OF CA LIFO R N IA

No. 69-5030

Lucious J ackson, Petitioner,

v.

S tate of Georgia, Respondent.

ON W R IT OF CERTIO RA RI TO T H E S U P R E M E CO U RT OF GEORGIA

No. 69-5003

W illiam H enry F urman , Petitioner,

Y.

S tate of Georgia, Respondent.

ON W R IT OF CERTIO RA RI TO T H E S U P R E M E CO U RT OF GEORGIA

No. 69-5031

E lmer B ranch, Petitioner,

v.

S tate of T exas, Respondent.

O N W R IT OF CERTIO RA RI TO T H E S U P R E M E COU RT OF TEXAS

2-M

Motion for Leave to File Brief Amici Curiae

The National Association for the Advancement of Col

ored People, the National Urban League, The Southern

Christian Leadership Conference, the Mexican-American

Legal Defense and Educational Fund, and the National

Council of Negro Women, respectfully move the court

for leave to file the attached brief amici curiae. The at

torneys for the petitioners have consented to the filing,

but except for the State of California, the attorneys for

the respondent have refused.

Movants have never before asked leave of this court

to file an amicus brief on previously presented aspects of

the administration of capital punishment. We do so now

because the decision of the court will have an unprece

dented impact on the manner in which the death penalty

is imposed upon the downtrodden and deprived minor

ities of this country, who too often are black.

Counsel for the Petitioners have covered admirably, we

think, the aspects of the case which deals with funda

mental violations of the Eighth and Fourteenth Amend

ments. While we are deeply concerned with those issues,

we shall, to avoid repetition, treat principally the areas

that bear with discriminatory harshness upon blacks, Mex

ican-Americans, the poor and other disadvantaged persons.

3-M

W herefore, movants pray that the attached brief amici

curiae be permitted to be filed with the Court.

Respectfully submitted,

Leroy D. Clark

New York University Law School

New York, New York 10003

N athaniel R. J ones

National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People

1790 Broadway

New York, New York 10019

V ernon J ordan

National Urban League

55 East 52nd Street

New York, New York 10022

Chauncey E skridge

Southern Christian Leadership

Conference

110 South Dearborn Street

Suite 1500

Chicago, Illinois 60603

Mario G. Obledo

Mexican-American Legal Defense

and Educational Fund

145 Ninth Street

San Francisco, California 94103

Attorneys for Amici

I n the

$upr?m? ©Hurt of % In it^ States

October T erm, 1971

No. 69-5027

E rnest J ames A ikens , J r., Petitioner,

v.

S tate oe California, Respondent.

ON W R IT OF CERTIO RA RI TO T H E S U P R E M E CO U RT OF C A LIFO R N IA

No. 69-5030

Lucious J ackson, Petitioner,

y.

S tate of 'Georgia, Respondent.

ON W R IT OF CERTIO RA RI t o T H E S U P R E M E COU RT OF GEORGIA

No. 69-5003

W illiam H enry F urman, Petitioner,

v.

S tate of Georgia, Respondent.

O N W R IT OF CERTIO RA RI TO T H E S U P R E M E CO U RT OF GEORGIA

No. 69-5031

E lmer B ranch, Petitioner,

v.

S tate of T exas, Respondent.

ON W R IT OF CERTIO RA RI TO T H E S U P R E M E COU RT OF TEXAS

BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE

2

Statement of Interest

This brief amici curiae is tendered by five national civil

rights organizations which work to obtain, protect, and

promote equal rights by lawful and peaceful means for

black, Mexican-American and other minority-American

citizens.

The National Association for the Advancement of Col

ored People, the National Urban League, The Southern

Christian Leadership Conference, the Mexican-American

Legal Defense and Educational Fund, and the National

Council of Negro Women, are united by the harsh reality

that capital punishment has become reserved almost exclu

sively for our nation’s minorities.

The National Association for the Advancement of Col

ored People (NAACP) has a membership of 470,000 black

and white belonging to 1,700 branches and offices through

out the nation. Since its inception in 1909, the NAACP

played a key role in securing legislation providing addi

tional enforcement machinery to deal with extra-legal forms

of capital pnuishment and bigoted lawlessness. It has also

songht to end racial discrimination, through our judicial

system in all aspects of American life. Complementing the

Association’s legal spearhead are extensive programs to

deal with racial factors in housing, education, employment,

voter registration, and the administration of criminal

justice.

The National Urban League, founded in 1910, is an inter

racial, non-partisan, non-profit organization. A national

movement with over 98 autonomous local affiliates, the Na

tional Urban League seeks social and political equalization

through channeling contributions received, to innovative

3

projects designed to free blacks and other minorities from

poor economic opportunities and unfair law enforcement.

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC)

was founded in 1957, and I)r. Martin Luther King was its

first President. Since its inception, SCLC’s fundamental

purpose has been the obliteration of all vestiges of racial

apartheid relying primarily on creative conflict-resolution

generated by non-violent techniques. Programs of SCLC

include voter registration, increased participation of blacks

in economic institutions (“Operation Breadbasket”) and

projects aimed at the elimination of poverty.

Pounded in 1967, the Mexican-American Legal Defense

and Educational Fund (MALDEF) is devoted to securing

the constitutional rights of Mexican-American citizens

through concerted effort in the courts and by preparing

young Mexican-Americans for legal careers . . . Since its

inception four years ago, MALDEF has handled, through

its four branches 90 per cent of the civil rights litigations

undertaken in behalf of Mexican-Americans.

The National Council of Negro Women began in 1935,

now includes a coalition of 25 national organizations and

concerned individuals; forming a network affiliating it with

about four million women throughout the United States.

Its one hundred and thirty-seven (137) sections are in

volved in innovative program approaches to chronic depri

vation and need by supporting black women to conduct

housing, day-care, drug addiction, and self-help economic

projects, sponsered by the National Council.

Past statements and resolutions adopted by these organi

zations reflect the united interest of the parties participat

ing in this brief. Addressing itself to the discriminatory

application of capital punishment, the 1969 resolution by

the Board of Directors of the National Urban League

stated:

4

“There seems little question that the death penalty

has been applied in a discriminatory fashion. The

black and the poor suffer the extreme consequence in

numbers far out of proportion to their rates of crime

. . . Since 1930 of the nearly 4,000 persons executed

fifty-five (55) percent have been black, although Ne

groes make up only eleven (11) per cent of our popu

lation. Almost without exception, the victims of execu

tion have been poor. Statistics indicate that discrimi

nation because of race is rampant and the death penalty

applied most often in instances of crimes by Negroes

against whites. It is all too often the poor, the weak,

the ignorant and the black who have been executed.”

From the facts at hand they were led to conclude:

“Since we are convinced that the death penalty fails

in its deterrent role; is patently unfair and discrimi

natory as applied to the poor and the black; distorts

our legal system and the psychology of our nation;

and may, in fact, be in violation of the Constitution,

the National Urban League ardently endorses and sup

ports all efforts to have this most extreme form of

punishment abolished.”

In re-acknowledging the commitment of the Association

against the imposition of capital punishment the 61st An

nual Convention of the NAACP resolved:

“Whereas, the Constitution of the United States of

America guarantees all persons without regard to race,

color, creed or national origin equal protection under

the law,

Whereas, the sad facts of past and recent history

clearly demonstrate that the vast majority of people

5

who have received the death penalty or are presently

held in death row are blacks,

Whereas, many not so held in death row or in other

facilities for crimes for which they were convicted by

juries that did not in fact have representatives of that

person’s peer group.

B e I t T herefore R esolved, that the National Office

use its prestige and resources to press for the Supreme

Court of the United States to abolish the death penalty

as cruel and inhuman punishment violative of the equal

protection clause and therefore unconstitutional.”

Speaking in behalf of Mexican-Amerieans, caught in the

criminal process, Mario G. Obledo, General Counsel for the

Mexican-American Legal Defense and Educational Fund

(MALDEF) has stated:

“Maldef believed that Mexican-Americans, particularly

in the Southwestern United States, receive and have

received the death penalty in greater frequency for

similar crimes than their Anglo or White counterpart.

Maldef is deeply concerned that the administration of

justice system is depriving the Mexican-American of

basic constitutional rights. The last man to be executed

in the United States was a Mexican-American.”

SCLC’s position against capital punishment is related to

its unique national reputation for steadfast espousal of

non-violence for individuals and the State; its former lead

er, Dr. Martin Luther King was a victim of a modern style

lynching while he was in the pursuit of the Ghandian ideals.

SCLC has not been deflected from its committment to the

non-violent philosophy even in the case of Dr. King’s death.

On the occasion of the conviction of James Earl Ray for

6

the assassination of Dr. King, Mrs. Martin Luther King

stated on behalf of the organization: “The death penalty

for the man who pleaded guilty to the crime would be con

trary to the deeply held moral and religious convictions of

my husband and the present President of SCLC, Dr. Ralph

D. Abernathy . . . Retribution and vengeance have no place

in our beliefs.”

The individual petitioners before this Court are engaged

in a grim struggle for their lives and will undoubtedly

seek to explore every facet of their case before this Court

and any other public body or official whose actions may

spare them. The undersigned, however, through their long,

unceasing and continuing fight to erase the stain of racism

from America, have a broader and more protective concern,

for they speak not only on behalf of the instant petitioners,

all of whom are black, but for the disproportionate number

of disadvantaged minority group members who will in the

future, if the past is any predictor, face the ultimate penalty.

It is only through organizations such as the undersigned

that ethnic groups who have been peculiarly subjected to

discrimination, but who still look to the constitution to

protect their young from an unjust penalty, can have their

day in Court, to state what they—who have been subjected

to much of this society’s inhumanity—believe are minimal

standards for civilized administration of criminal justice.

The undersigned organizations, because of their unique

goals, have a special responsibility to place the death pen

alty before this Court within the full context of the struggle

for racial justice.

7

Summary of Argument

I.

The total history of the administration of capital punish

ment in America, both through formal authority, and in

formally, is persuasive evidence, that racial discrimination

was, and still is, an impermissible factor in the dispropor

tionate imposition of the death penalty upon non-white

American citizens.

II.

A. The available social science data is sufficient to sub

stantiate the assertion that the death penalty is discrimina-

torily imposed in contravention to the Equal Protection

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. However, where an

inference exists that an impermissible factor is a basis for

the imposition of the death penalty, the burden shifts to

the state to refute that inference. To take a life, without

refutation of that impermissible factor is inconsistent with

the “cruel and unusual punishment” clause of the Eighth

Amendment.

B. In view of the trend away from the imposition of

formal and informal punishment on alleged black offenders,

any lingering executions which “prima facie” have been

affected by racial discrimination, violate contemporary

American standards for civilized criminal justice; thereby

constituting cruel and unusual punishment.

8

I.

Pre-1935 History of the Racially Discriminatory Use

of Formal and Informal Capital Punishment by Whites

Against Non-Whites.

A. Slavery 1619-1865.

The Court is faced with the ultimate in the use of pub

lic authority over its citizens—four black defendant’s lives

hang in the balance. The amici curiae, wish to place the

penalty predicament of these four defendants within the

total historical context of the infliction by whites of pun

ishment upon non-whites, both through the formal public

authority, and informally, in an attempt to assert that

the contemporary phenomenon, capital punishment, is

merely the grossest (because irremediable) and contem

porary evidence, of continued racial discrimination oper

ating to impose heavier burdens on the non-white popula

tion in the criminal process.

No attempt will be made here to focus on unprovoked,

near-genocidal behavior, such as that which occurred in

crossing the Atlantic during the slave trade,1 or the near

extinction of the American Indian due to systematic forays

by white settlers on the western frontier. Nor will we

cover the black fatalities due to white inflicted race riots,

where the black victims were largely the by-product of

general random violence, which, as they progressed, be

came hysterical reactions and not responses to specific

offenses. We will concentrate on that form of racial hos-

1 Accurate figures with respect to the total number of slaves

imported to the country do not. exist, but estimates range up to

fourteen million. “From Slavery to Freedom—a History of Negro

Americans”, pages 58-59, 3rd Edition (1966), John Hope Franklin.

It has been further estimated that one-third of the blacks taken in

Africa died on the coast and another third in crossing the ocean.

“Slave and Citizen”, pages 28-29 (1947), Frank Tannenbaum.

9

tility, approved or by the white majority, which controlled

the dispensation of fatal penalties for alleged perpetrators

of crime.

The most brutal and inhumane forms of punishment-

crucifixion, burning and starvation—were legal under the

slave codes in the early colonies and were used extensively

because imprisonment would have been a reward, giving

the slave time to rest, and fines could not be collected

from unpaid laborers.2 While one would imagine that the

fact that the slave was conceived of as primarily an eco

nomic unit would make him totally immune to capital

punishment, in fact, he was exposed to a higher liability

than non-slaves in this regard under formal statutes:

“State criminal codes dealt more severely with slaves

and free Negroes than with whites. In the first place,

they made certain acts felonies when committed by

Negroes; and in the second place, they assigned heavier

penalties to Negroes than whites convicted of the same

offense. Every southern state defined a substantial

number of felonies carrying capital punishment for

slaves and lesser punishments for whites. In addition

to murder of any degree, slaves received the death

penalty for attempted murder, manslaughter, rape

and attempted rape upon a white woman, rebellion

and attempted rebellion, poisoning, robbery, and

arson. A battery upon a white person might also

carry a sentence of death under certain circum

stances.” 3

2 “The Suppression of the African Slave Trade to the United

States of America”, page 6 (1954), W. B. B. du Bois.

8 “The Peculiar Institution-—Slavery in the Ante-Bellum South”,

page 210 (1956), Kenneth M. Stamp.

10

This pervasive authorization of capital punishment was,

ironically, due to the fact that the slave trade was so

thriving; often the masters of the slaves were so largely

outnumbered that there was always the fear of violent

rebellion.4 The intense fear of violent reaction by blacks

had its roots in the real security problems of the slave

owners, but it has spread to the general populace in the

South and to the North as blacks migrated and has had

a continual impact on the white public’s view of blacks

charged with crimes against whites.

Capital punishment was also freely authorized for whites

who interfered with slave discipline. North Carolina made

death the penalty for concealing a slave “with the intent

and for the purpose of enabling such slave to escape,”

and Louisiana made it a capital offense to use “language

in any public discourse, from the bar, the bench, the stage,

the pulpit, or any place whatsoever” that might produce

“insubordination among slaves.” The only brake on the

actual imposition of capital punishment was the interest

of the slave-owner in maintaining continuing production,

but encouragement to use the penalty for slaves seen as

particularly obstreperous existed by way of reimburse

ment of the owner for any slaves so disposed of.6 Further,

formal capital punishment was not needed to control

slave rebellions for these were largely responded to with

4 Indeed, this appears to be the prime factor in abatement of the

slave trade after the Eighteenth Century. This attessts to the

intensity and depth of the fear of blacks-—because slavery was

highly profitable for the whites involved. “The Suppression of the

African Slave Trade”, supra, p. 6.

6 “White Over Black”, p. 106 (1968), Winthrop Jordan.

11

immediate and ruthless counter-violence on the spot.6 Such

was the formal, explicit utilization of capital punishment

during the slavery period—a use which was totally un

related to the gravity of the crime, dangerousness of the

offender, or any of the other oft asserted, superficially

plausible justifications for the death penalty. The prime

and express purpose of capital punishment in this context

was to maintain the maximum threat for any reaction

against the caste-like slave system.

B. Lynching and Vigilantism 1882-1935.

Immediately after slavery, when the freed men in the

South came into economic cempetition with the white poor,

and no longer could rely on the protection of their lives

by white plantation owners, violence in the form of lynch

ing—the informal mob resort to summary capital punish

ment for real or alleged crimes—increased sharply in

severity:

“From 1882 to 1903 the staggering total of 1,985 Ne

groes were killed by Southern mobs. Supposedly the

lynch-mob hanging (or, too often, the ghastly penalty

of burning alive) was saved for the Negro murderer

or rapist; but the statistics show that Negroes were

frequently lynched for lesser crimes or in cases where

there was no offense at all or the mere suspicion of

one. Lynch-mob violence became an integral part of

the post-Reeonstruction system of white supremacy.” 7

During this period 1,169 whites were also lynched, but

the proportion of non-whites was approximately 60% of the

6 “Violence in America—Historical and Comparative Perspec

tives—a Staff Report to the National Commission on the Causes

and Prevention of Violence”, p. 39, Vol. I (1969), Hugh Graham

& Ted Gurr.

7 “Violence in America”, Vol. I, page 38.

12

total [this includes 108 non-whites who were not black], a

figure roughly paralleling the 53% of non-whites executed

by way of capital punishment post-1930.8

Between 1903 and 1935, it has been estimated that an

additional 1,015 blacks were lynched by white mobs. These

figures do not include kangaroo court actions, unreported

murders, or blacks killed in race riots.9 It is clear, however,

that by 1935 the recorded and easily identifiable lynchings

were sharply in abatement. From a high of 130 killed in

1901,10 and 70 in 1918,11 lynching became almost non-exis

tent, with 2 killed in 1950, 1 in 1951 and 1 each in the years

1957 through 1959.

We have been using the term “lynching” primarily based

on the definition by the recent Violence Commission Re

ports ; “The practice or custom by which persons are pun

ished for real or alleged crimes without due process of

law . . . an unorganized, spontaneous, ephemeral mob which

comes together briefly to do its fatal work.” Other non-

white ethnic groups have been murdered primarily by

another form of white lawlessness, namely Vigilante vio

lence, a more organized and systematic usurpation of the

functions of law and order. It was supported often by men

occupying the high office of Senator and Congressman, and,

when not being used to check horse thievery, it was used for

racial intimidation of Mexican-Americans, Chinese and

Indians.12

8 “Violence in America”, Vol. I, supra, p. 57, footnote 27.

9 “Violence in America”, page 344, Vol. II (1969).

10 “Race Relations and American Law”, page 320 (1959), J.

Greenberg.

11 “Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Dis

orders”, page 102 (1968).

12 “Violence in America”, Vol. I, supra, footnote, pages 40, 52.

13

“Not unmixed with vigilantism is frequently a fair

share of racism, which has its own curious history on

the American frontier. In some ways the frontier was

the freest of places in which a man was judged on the

quality of his work and his possession of such abstrac

tions as honesty, bravery, and shrewdness. The Chi

nese merchant, the Negro cowboy, the Indian rider

all were admired because of what they could do within

the frontier community and not because of their pig

mentation. On the other and, the only good Indian was

a dead Indian, ‘shines’ could seldom rise above the

worker level, and ‘coolies’ wrere something to take

potshots at without fear of retribution, either civic or

conscience. Just as lynching a Negro in parts of the

South was no crime, so shooting an Indian or beating

an Oriental or a Mexican was equally acceptable. Like

all societies, the frontier had its built-in contradic

tions.” 13

II.

The Disproportionate Numbers of Non-White Persons

Executed by Formal Capital Punishment Constitutes

Cruel and Unusual Punishment in Violation of the Eighth

and Fourteenth Amendments of the Constitution.

The above material now brings us down to 1930, which

is the earliest date for which statistics are available on

persons executed after a formal trial. It is the thesis of

this brief that this Court must evaluate the constitutional

question of the arbitrary application of the death penalty

within the context of prior history of official and non-official

racial violence, and that the figures on capital punishment

post-1930 can only be explained as a residual end product

13 “Violence in America”, Vol. I, supra, footnote, page lOo.

14

of the prior practices of meting out the severest penalty on

racial grounds. The capital punishment statutes under

slavery would, by today’s standards, clearly be unconstitu

tional, both as a denial of equal protection of the laws and

as cruel and unusual punishment under the Federal Consti

tution. The Civil War has precluded that question from

reaching this Court, but we see that historically, lynching

and vigilantism, while technically not authorized by State

statutes, historically performed the same function of domi

nation and subjection on nonwhites by a white majority.

When lynching and vigilantism were subsiding, the white-

initiated race riot continued to play the lawless function of

intimidation by fatalities in the early 1900’s. [In time, that

form of technically unapproved mass execution fell rapidly

into disuse, but it is unbelievable that a society with such

a history of ingrained and widespread use of violence

against nonwhites as a prime reaction to perpetration of

crime, could suddenly cease injecting racist considerations

into the formal administration of justice.] It must be noted

that all social science examination of the extent and depth

of racial hostility by whites against nonwhites have re

ported that it has been pervasive and intense,14 and as late

as 1968, the National Advisory Commission on Civil Dis

orders could conclude:

“Our Nation is moving toward two societies, one black,

one white—separate and unequal.” 16

But the fact of the historical continuity need not rest on

assertion of generalized racism in American society, for the

current data creates the clear, to date, unrefuted inference

that disproportionate imposition of the death penalty upon

14 See generally, “An American Dilemma”, Myrdal, G.

16 Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Dis

orders, page 1.

15

blacks and other minorities is a function of racial discrimi

nation.

Based upon statistics compiled by the Federal Bureau of

Prisons, 3,859 persons were executed in this country be

tween 1930-1968. Of these 2,066 were blacks; 1,751 were

whites and 42 were of other minority groups.16 Proportion

ately, more than one half of the prisoners executed in this

country were black during a period in which blacks consti

tuted less than one tenth of the nation’s population. More

persuasive however, are the figures of persons executed

for rape and murder. Of the 3,334 persons executed for

murder, almost one half, 1,630 were blacks. Shocking how

ever, is the fact that 1,231 of the blacks executed for murder

were from the South.17

16 The figures below illustrate the racial composition of the pris

oners executed between 1930-1967:

Rape

Murder

Other

Black White Other Total

405 (89.0%) 48 (10.6%)

1630 (48.9%) 1665 (49.9%)

31 (44.3%) 39 (55.7%)

2 (0.4%) 455 (100%)

40(1.2% ) 3334 (100%)

0(0.0% ) 70 (100%)

Total 2066 (53.1%) 1751 (45.4%) 42 (1.1%) 3859 (100%)

17 The following is a breakdown by region, of prisoners executed

for crimes of murder and rape, 1930-1968;. 98% of the executions

in the U.S. were for rape and murder.

M u rd e r R ape

R eg io n T o ta l W h ite B la ck O th er T ota l W h ite B lack O ther

Northeast

(9 States) 606 422 177 7 - - -

Northcentral

(12 States) 393 254 137 2 10 3 7 -

South

(16 States) 1,824 585 1,231 8 443 43. 398 2

West

(13 States) 496 393 82 21 - - - -

Federal 15 10 3 2 2 2 - -

Total 3,344 1,664 1,630 40 455 48 405 2

16

Equally as significant are the rape statistics, nationally

455 persons were convicted of rape. Of these 405 or 89%

were black. As the figures indicate below, 443 convicted

rapists were executed in the South, of these 398 were black.

Although the foregoing statistics give the overall impres

sion that racial discrimination in the United States is the

root cause of the disproportionate imposition of the death

sentence on blacks and other minority groups, a systematic

and extensive examination of differentials in capital sen

tencing was undertaken in the summer of 1965 by Dr.

Marvin Wolfgang, a professor of Sociology at the Univer

sity of Pennsylvania.18 Briefly, the study was a survey of

rape convictions during the period 1945-1965 of nineteen

randomly selected counties in the State of Arkansas. The

study compared the rate of death sentencing for black and

white defendants all of whom were convicted of the crime

of rape. The approach was to develop a “null hypothesis”

that there is no difference in the distribution of the sentence

of death or life imprisonment imposed upon black and white

defendants. The principal variables considered were the

race of the defendant, of the victim, and sentence. However,

other data ranging from family status to circumstances at

the trial were gathered and analyzed. Prom the Arkansas

data, and his survey, Dr. Wolfgang concluded “that Negro

defendants who rape white victims have been dispropor

tionately sentenced to death by reason of race during the

years 1945-1965 in the State of Arkansas.”

The Wolfgang survey, although limited to the crime of

rape, clearly substantiates the fact that the death penalty

has been diseriminately applied over the years in those

states which retain the death penalty.

18 Dr. Marvin Wolfgang’s study was extensively reviewed and

discussed in Maxwell v. Bishop, 398 Fed. 138.

17

The above data confirms the hypothesis of the amici

curiae, especially with respect to the data drawn from the

South, that current figures showing the large proportion

of nonwhites who were executed is merely the present phe

nomenon of racial discrimination being exercised against

the nonwhite. Slavery was exclusively a Southern phe

nomenon, lynching was primarily a Southern phenomenon,

and the general data with respect to all crimes, and par

ticularly the crime of rape,19 indicates that the South has

been the prime contributor to the disproportionate applica

tion of the death penalty to blacks. If this data is coupled

with other material showing the explicit Southern legisla-

19 The history of the South’s use of the death penalty in rape

cases during the period preceding the civil war, unmistakably shows

the original official empathis for this region’s discriminatory appli

cation of capital punishment. Of 15 jurisdictions which had sepa

rate penal laws for free persons and for slaves, in 9 jurisdictions

(Alabama, District of Columbia, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi,

Missouri, [the mandatory penalty for blacks was not death, but

castration], Tennessee, Texas and Virginia). Rapes committed by

whites were not punishable by death, while in the cases of rapes or

attempted rapes upon white women committed by black men, the

death penalty was mandatory. In Louisiana and Maryland the

crime of rape committed by whites was punishable by death or

terms of imprisonment, while in the case of blacks the death penalty

was mandatory for the crime of rape or attempted rape upon a

white woman. In the four remaining jurisdictions, Arkansas,

Florida, North Carolina, and South Carolina, assault with intent

to commit rape upon a white woman was a capital offense for a

black man, but not for a white man. It is to be noted that in every

jurisdiction but the District of Columbia and Mississippi, the

statutes imposing more severe penalties for the crime of rape, or

attempted rape, or assault with intent to commit a rape not only

applied to slaves, but also expressly applied to “free persons of

color”, furthermore, in each one of the 15 jurisdictions the death

penalty was mandatory (except in Missouri where the mandatory

penalty was castration), for the crime of attempted rape upon a

white woman by a black man, in none of these jurisdictions punish

able by death if committed by a white man upon any woman, white

or black, nor was that crime punishable by death if committed by a

black man upon a black woman. The source of the above summary

is included in Appendix A.

18

tion excluding blacks from juries80 and, where that no

longer obtained, the racial exclusion of blacks in adminis

tration of jury selection,21 we know that the capital pun

ishment figures are explained in part by the fact that the

bulk of the white population from 1930 through the 50’s had

not totally expunged its racial prejudice, and was probably

allowing the race of the defendants to affect their judg

ment. It is precisely because of this phenomenon that some

of the amicus curiae have worked actively to reverse the

trend of the exclusion of non-whites from juries. To vote

to put a man to death requires the juror to place some

distance between himself and the defendant, and this proc

ess is facilitated if he can, because of some perception of

the defendant, dehumanize him—racial prejudice can play

exactly that function.

Amici curiae submit that the above data is sufficient to

raise a claim on behalf of the instant petitioners that the

application of the death penalty has been discriminatory

and violative of the equal protection clause of the Federal

Constitution. However, because some experts have ques

tioned the definitive and conclusive nature of the data22

showing the role race has played in the application of the

death penalty, amici curiae assert that the cruel and un

usual punishment provisions of the Federal Constitution are

flexible enough to sustain this Court in voiding the death

penalty in its present state of application on the basis of

two propositions: (1) that where a defendant faces an

irreversible penalty, and creates, through maximum devel

opment of contemporary social science data within his lim-

20 See, eg., Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1879).

21 Race Relations in American Law, supra, footnote —, pp. 323-

328.

22 The Death Penalty In America (paperback edition), (pp.

411-413).

19

ited resources, an inference that an impermissible factor

has controlled or modulated the imposition of such penalty,

the burden shifts to the State to refute that inference, and

in lieu of such refutation, it is cruel and unusual punish

ment to put the defendant to death. (2) The current trend

of white imposition of formal and informal punishment on

alleged black offenders shows a movement away from ex

plicit, and lawless racial violence, a progressive reduction

of the factor of race in meting out formal punishment such

that any lingering executions which prima facie have been

affected by race, would violate contemporary American

standards for civilized criminal justice and constitute cruel

and unusual punishment.

The cruel and unusual punishment provisions of the

Eighth Amendment to the United States Constitution can

best be described as dynamic, subject to interpretation based

on the realities as existing in society, and the state of men’s

m i n d s when its interpretation is before the Court. This

Court has long ago acknowledged that great “difficulty

would tend the effort to define with exactness the extent of

the constitutional provision which provides that cruel and

unusual punishment shall not be inflicted.” Wilkerson v.

Utah, 90 U.S. 130, 135-136, 25 L. Ed. 345 (1878). Despite

the difficulty in interpreting the “cruel and unusual pun

ishment” clause this Court in Weems v. United States, 217

U.S. 399, 30 S.Ct. 544 (1910) held that a section of the

Philippine Legal Code which imposed punishment dispro

portionately to the crime was likewise violative of the cruel

and unusual clause. The Court clearly stated that the defi

nition of cruelty shall be governed by the “contemporary

standards.” In Weems, the Court stated: “the clause of

the Constitution in the opinion of commentators, may be

therefore progressive and is not fashioned to be obsolete,

but may acquire meaning as public opinion becomes en

lightened by humane justice” 217 U.S. at 378. In Trop v.

20

Dulles, 356 U.S. 86, 78 S.Ct. 90 (1958), the Court in holding

that de-nationalization for wartime desertion was cruel and

unusual punishment, reaffirmed the “flexibility” of the

Eighth Amendment as stated in Weems, and provided a

new formula. It stated: “The Amendment must draw mean

ing from the evolving standards of decency that mark the

progress of a maturing society,” 356 U.S. at 101, 78 S.Ct.

at 598.

Amici curiae assert that the clear sweep of American

history, running from the period of slavery through the

extra-legal and racially motivated lynchings, vigilantism

and race riots shows an unmistakable and contemporary

trend toward disuse and relinquishment of race as a basis

for taking a man’s life. White America has released its

blacks from their status as slaves who faced official dis

criminatory application of the death penalty. There is

no more Western frontier to conquer to act as the excuse

for extermination of additional American Indians. Whites

no longer organize vigilante parties against the rest of.

its Spanish-speaking and Oriental population : and, they

have given up taking to the streets to murder blacks in

race riots. It is true that white Americans left the street

and entered the jury box to continue to exercise their

racial animosity, but even this phenomenon has been on

the decrease as the jury population recoiled from the ap

plication of capital punshment in general. From 1940

through 1960 more blacks were executed than whites each

year. From 1951 to 1961, a higher number of blacks than

whites were executed for 7 of the 10 years. Since 1962

there has been a reversal in this trend and for 5 of the

6 years more whites were executed than blacks, and in the

last year (1967) the executions were even—1 white and

1 black.23

23 National Prisoner Statistics (1968), p. 7.

21

Racism, from which many receive concrete economic

benefits and psychic sustenance, subsides with great re

sistance—especially given the current attempts by irres

ponsible politicians to revive fears in the white populace

of the “black rebel” with the code words of “Law and

Order.” There is, however, some indication, that white

America regardless of the continued racial discrimination

in many facets of American life, desires,—at least with

respect to capital punishment,—not to take a man’s life

simply because the color of his skin differs from theirs.

It remains only for this Court to validate that direction.

We re-assert that this Court may find the continued ap

plication of the death penalty within the American con

text, as cruel and unusual punishment without a finding

that race has controlled the death decisions to a statis

tical certainty. I t need only find that the defendants

have marshalled enough evidence, within the available

social science data bearing on the subject, to create an in

ference that race has affected the application of the death

penalty to the overwhelming number of men now on death

row and that to execute the defendants under this state

of the evidence is cruel and unusual punishment. We

hasten to remind the Court that the overwhelming number

of non-whites in this country, Indians, Black, Puerto Ri

cans and Mexiean-Americans are poor, and that another

inference created by the current social science data is

that the class of the defendant, again an irrelevant factor

in any rational criminal law system, may be a contribut

ing element to their receipt of the death penalty. Another

clear and unmistakable contemporary standard which this

Court has consistently, and with elaboration begun to an

nounce is that the indigency of a defendant should not

be allowed to affect the outcome in a criminal prosecu

tion. Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963); Douglas

v. California, 372 IT.S. 353 (1963). This standard should

22

reinforce the holding which amici curiae argue for, namely

that defendants’ inability, due to their indigency and conse

quent lack of resources, to produce statistically certain

proof of the discriminatory application of the death pen

alty cannot be allowed to cause their deaths. To place

a burden of proof on indigent defendant beyond that

which he has resources to sustain,24 especially where he has

established a prima. facie case that an irreversible penalty

will be applied to him unconstitutionally, is itself cruel

and unusual punishment. This Court can legitimately take

the small step of merging its evolving protection for blacks

and indigents under the equal protection clause, with the

announcement of this minimal civilized standard for con

trolling the ultimate penalty available in a criminal justice

system. To look back twenty years from now when the

statistical data is in an even more developed shape and to

find that post 1971 men had still been put to death for being

non-white, and not possessed of sufficient resources to give

further proof of it, would be a travesity of justice.

24 There is also some serious question as to whether any defendant,

even with unlimited resources, could offer proof beyond that which

is current that the death penalty has been applied discrimjnatorily.

Record keeping has varied over the years, trial transcripts do not

reveal all the pertinent data. If proof of past jurors’ subjective

state of mind were required, that would be impossible. The vast

number of variables which impinge upon any complex human

behavior make it difficult to isolate one as a single causative factor

in explaining any human event. But where the cost to the defen

dant is so total, and the interest of the State so minimal, the Court

must find some formula for giving credence to maximum amount ot

information which defendant facing terminal penalty could pro

duce, given the inherent compromises on ideally definitive data.

23

CONCLUSION

Capital Punishment clearly violates the equal protection

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, and the cruel and

unusual clause of the Eighth Amendment, it should on

that basis be ruled unconstitutional.

Respectfully submitted,

L eroy D. Clark

New York University Law School

New York, New York 10003

N athaniel R. J ones

National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People

1790 Broadway

New- York, New York 10019

V ernon J ordan

National Urban League

55 East 52nd Street

New York, New York 10022

Chatjncey E skridge

Southern Christian Leadership

Conference

110 South Dearborn Street

Suite 1500

Chicago, Illinois 60603

Mario G. Obledo

Mexican-American Legal Defense

and Educational Fund

145 Ninth Street

San Francisco, California 94103

Attorneys for Amici

Appendix A

Pre-Civil War History of Punishment for Rape in Southern

States and Washington, D.C.

A labama

whites: An act of 1802 provided that rape shall be

punished by death. Harry Toulmin, Digest of the

Laws of the State of Alabama 207 (1823). In 1841,

the punishment for rape was changed to life im

prisonment. C. C. Clay, Digest of the Laws of the

State of Alabama 414 (1843).

slaves, free negroes, and mulattoes: An act of 1814

provided that a slave convicted of an attempt to

rape a white woman shall suffer death. Harry

Toulmin, Digest of the Laws of the State of Ala

bama 185 (1823). The 1841 Penal Code of Slaves

and Free Negroes provided that a slave, free negro

or mulatto convicted of the crime of rape upon,

or an attempt to rape upon, a white woman shall

suffer death. C. C. Clay, Digest of the Laws of the

State of Alabama 472 (1843).

A rkansas

whites: The punishment for rape is death. Act of Dec.

14, 1842 in Josiah Gould, A Digest of the Statutes

of Arkansas 334 (1858).

negroes and mulattoes: The punishment for rape is

death; the punishment for attempted rape of a

white woman is death. Id. at 335.

D istrict of Columbia

whites: A Code of Laws for the District of Columbia

published in 1819 by the Judges of the Circuit

la

2a

Court and the Attorney for the District of Colum

bia, who had been authorized by Congress to pre

pare a code of jurisprudence for the District, rec

ommended that free persons convicted of the crime

of rape be punished with two to twenty (20) years

of imprisonment. This Code was not adopted.

W. Cranch, Code of Laws for the District of

Columbia 235 (1819).

A Penal Code published by order of the Senate

on February 28, 1833, provided that rape was pun

ishable by life imprisonment. A System of Civil

and Criminal Law for the District of Columbia 367

(1833).

The penal law in effect in 1857 provided that rape

of a man’s daughter or sister shall be punished by

life imprisonment and rape of any other woman

or child shall be punished by five to twenty (20)

years imprisonment, for the first offence, and life

imprisonment for the second offence. Devised Code

of the District of Columbia 518-519 (1857). An

assault with intent to commit a rape was punish

able by three (3) to fifteen (15) years imprison

ment. Id. at 58.

slaves: The punishment for attempting to commit a

rape upon a white woman is death. Worthington

G. Snethen, Black Code of the District of Colum

bia 18 (1848).

F lobida

whites: The punishment for rape is death. Act Feb.

10, 1832, §2 in Leslie A. Thompson, Manual or

Digest of the Statute Law of the State of Florida

490 (1847).

3a

slaves, free negroes, or mulattoes: An act of 1828 pro

vided that any negro or mulatto who assaults a

white woman or child with intent to commit a rape

shall be cropped, branded or suffer death, at the

discretion of the court. Acts of the Legislative

Council of the Territory of Florida, 1827-8, 109

(1828). An act of 1840 provided that the punish

ment for rape or assault with intent to rape a white

woman shall be death. Act March 2, 1840, §2 in

Leslie A. Thompson, Manual or Digest of the Stat

ute Law of the State of Florida 538 (1847).

Georgia

whites: Punishment for rape is imprisonment at hard

labor for not less than seven nor more than sixteen

years. Lucious Q. C. Lamar, Compelation of The

Laws of Georgia 552-1821. In 1816, the penalty for

rape in the penal code was changed to imprison

ment for not less than two nor more than twenty

years, and a section was added punishing at

tempted rape by imprisonment by for not less than

one nor more than five years.

Lamar, supra p. 571.

Between 1816-1861 a rape by a wdiite person upon

a free white female remained punishable by im

prisonment for no less than two, nor more than

twenty years; I'ape upon a slave or free person

of color was made punishable by fine and imprison

ment at the discretion of the Court.

An assault with intent to commit rape remained

punishable with one to five years of imprisonment.

Clark, Cobb, Irwin, Code of The State of Georgia,

Penal Code, §§4248-4250, p. 824 (1861).

4a

slaves, free negroes: In 1816 the punishment for the

crime of rape or attempted rape of a free white

female was death. Lamar, supra, p. 804.

Between 1816-1861 rape upon a free white female

remained punishable by death. Attempted rape

upon a free white female was punishable by death

or such other punishment as the Court might pre

scribe. Clark, Cobb, Irwin, Penal Code For Slave

and Free Persons of Color, §§ 7704, 4708, page 918

(1861).

K entucky

whites: An act passed in 1798 provided that rape shall

be punished by imprisonment for four to twenty-

one (21) years. Morehead and Brown, Digest of

the Statute Laws of Kentucky, Yol. II, 1265 (1834).

In 1801 the penalty for rape was changed to im

prisonment from ten to twenty-one (21) years. Id.

at 1269. In 1813 an act was passed which made

rape “upon the body of an infant under the age

of twelve years” punishable by death. Littell and

Swigert, Digest of the Statute Law of Kentucky,

Vol. II, 1009 (1822).

The Revised Statutes of Kentucky in force from

July 1, 1852, and published in 1867, retain the

death penalty for a rape upon an infant under

the age of twelve years. Richard H. Stanton, Re

vised Statutes of Kentucky, Vol. 1, 379 (1967).

Rape of a white woman is punishable by imprison

ment from ten to twenty years, the same punish

ment applies to carnal knowledge of a white girl

under the age of ten years. Id. at 379-80.

slaves and free negroes: The act of 1801 provided that

slaves shall be punished by death for rape com-

5a

mitted upon a white woman. Morehead and Brown,

Digest of the Statute Laws of Kentucky, Vol. II,

1282 (1834). In 1811, an attempt to commit a rape

upon a white woman by a slave was made punish

able by death. Id. at 1288.

By 1867, free negroes as well as slaves were pun

ished by death for rape upon a white woman or an

attempt to commit such rape, or for being an

accessory before the fact to either of these crimes.

Richard H. Stanton, Revised Statutes of Kentucky,

Yol. II, 375 (1867).

L ouisiana

whites: A proposed System of Penal Law published

in 1833 as a result of a commission from the

General Assembly of Louisiana provided that the

punishment for rape should be life imprisonment.

Edward Livingston, A System of Penal Law for

the State of Louisiana 435 (1833).

An act passed in 1855 provided that the punish

ment for rape shall be death. However, a com

panion provision gave juries the power to sub

stitute life imprisonment for the death penalty.

Acts [1855], Nos. 120, §4 and 121, §25. In 1855,

the maximum penalty for assault with intent to

commit a rape was two years imprisonment. U. B.

Phillips, Revised Statutes of Louisiana 136 (1856).

slaves and free colored persons: An act passed in

1855 provided that slaves and free colored per

sons shall be punished by death for rape upon or

attempted rape upon a white female. Acts [1855]

No. 308 §6.

6a

Maryland

whites: By an act of 1810, the punishment for rape

was death or imprisonment for not less than one

year nor more than twenty-one (21) years, at the

discretion of the court-. Kilty, Harris and Wat

kins, The Laws of Maryland, Yol. IV, Nov. 1809,

Ch. 138 §4. In 1860 the punishment for rape was

death or imprisonment for not less than eighteen

months nor more than twenty-one (21) years at

the discretion of the court. Scott and M’Cullough,

The Maryland Code, Yol. I, 242 (1860). The pun

ishment for assault with intent to rape was im

prisonment for not less than two nor more than

ten (10) years. Scott and M’Cullough, Revised

Laws of the State of Maryland 209 (1859).

negro or mulatto slave: An act of 1819 made it un

lawful for a court to sentence any negro or mu

latto slave to imprisonment, and in effect made

the death penalty mandatory in case of rape.

Kilty, Harris and Watkins, The Laws of Mary

land, Vol. VI, 1818, Ch. 197 §1. For an assault

with intent to rape, the court had discretion, under

the terms of this act, to sentence any slave to

be whipped or to banishment from the state. Id.,

2. The law in 1860 provided where the punishment

would be imprisonment were the defendant white,

the negro slave shall be sentenced to be sold out

of the state for such term as he may have to

serve. Scott and M’Cullough, The Maryland Code,

Vol. I, 250 (1860). In the case of a free negro,

he shall be sentenced to be sold either in or out

of the state, at the discretion of the court, for

such term as a white man for the same offense

would be sentenced to imprisonment. Ibid.

7a

negroes or mulattoes (free or enslaved): In 1859 the

punishment for impregnation of a white woman

was that he he sold beyond the limits of the state

as a slave for life. Scott and M’Cullough, Re

vised Laws of the State of Maryland 242 (1859).

Mississippi

whites: An act passed June 14, 1822, provided that

the punishment for rape shall be death and the

punishment for assault with intent to rape shall

be a fine and not more than imprisonment for

one year. Revised Code of the Laws of Missis

sippi, Ch. 54, §§6 and 11, 297, 298 (1824).

In 1839 the punishment for rape was changed to

not less than ten (10) years imprisonment. 1839

Laws (Adjourned Session, Jan. 7 to Feb. 16,

1839), Ch. 66, 116. The penal laws were expressly

extended to all free persons of color. Id. at 190.

By 1857 the punishment for rape had been changed

to life imprisonment. Revised Code of the Stat

ute Laws of the State of Mississippi, Art. 218, 608

(1857).

slaves: The act of June 18, 1822, provided that the

punishment for an attempt to rape a free white

woman or child shall be death. Revised Code of

the Laws of Mississippi, Ch. 73, §55, 381 (1824).

Slaves were not affected by the act of 1839 which

eliminated the death penalty for rape. 1839 Laws

(Adjourned Session, Jan. 7 to Feb. 16, 1839), Ch.

66, 190. The Revised Code of 1857 provided that

slaves shall suffer death for rape upon or an at

tempt to rape any white woman, or for having

“carnal connexion” or attempting to have “such

8a

connexion” with any white female child under the

age of fourteen years. Revised Code of the Stat

ute Laws of the State of Mississippi, Art. 68, 248

(1857).

M issouri

whites: In 1818, the law of the Missouri Territory

provided that the punishment for rape shall he

castration. Henry S. Geyer, Digest of the Laws of

Missouri Territory 137 (1818).

In 1825, after Missouri had become a state, rape

remained punishable by castration, and an assault

with intent to rape was punished by imprisonment

for not more than seven (7) years. Laws of the

State of Missouri: Revised and Digested, Yol. I,

283 (1825).

In 1835, the punishment for rape was changed to

imprisonment for not less than five (5) years. The

Revised Statutes of the State of Missouri 170

(1835).

slaves, negroes, or mulattoes: The law of the Mis

souri Territory punished rape by a slave with

castration. Henry S. Geyer, Digest of the Laws

of Missouri Territory 158 (1818).

In 1825, the law of the State of Missouri provided

that in the case of slaves, rape upon any person,

or attempt to commit a rape upon a white woman,

shall be punished by castration. Laws of the State

of Missouri: Revised and Digested, Yol. I, 283

(1825).

In 1835, when the punishment for rape by whites

was changed to a term of imprisonment, rape upon,

or an attempt to commit a rape upon, a white fe

male by any negro or mulatto was made punish

able by castration. The Revised Statutes of the

State of Missouri 170-71 (1835).

N evada

An act passed in 1861 provided that the punishment for

rape shall be imprisonment for not less than five

years to life imprisonment, and the punishment

for assault with intent to rape shall be not less

than one nor more than fourteen years imprison

ment. Bonnifield and Healy, Compiled Laws of

the State of Nevada, 1861-1873, Vol. I 557 (1873).

N orth Carolina

whites: The punishment for rape was death. Revised

Statutes of the State of North Carolina, Vol. I,

192 (1837).

“persons of color” : The punishment for rape or for

an assault upon a white female with intent to com

mit a rape was death. Id. at 590.

S outh Carolina

whites: An act enacted in 1712 provided that rape shall

be punished by death. Thomas Cooper, Statutes

At Large of South Carolina, Vol. II, 498 (1837).

slaves or free persons of color: By an act enacted in

1843, the punishment for an assault upon a white

woman with intent to rape is death.

Tennessee

whites: Rape was punished by imprisonment for not

less than ten nor more than twenty-one (21) years.

Assault with intent to commit a rape was pun-

10a

ished by imprisonment for not less than two nor

more than ten (10) years. Meigs and Cooper, Code

of Tennessee 830 (1858).

slaves and free persons of color: Rape upon or an

assault with intent to commit rape upon a free

white female, and having or attempting to have

sexual intercourse with a free white female under

twelve years of age, were punished with death.

Id. at 509, 524.

T exas

whites: An act of Aug. 28, 1856 provided that the pun

ishment for rape shall be not less than five nor

more than fifteen years imprisonment. Oldham

and White, A Digest of the General Statute Laws

of the State of Texas, Penal Code Art. 529, p. 523

(1859).

slaves and free persons of color: An act of Feb. 12,

1858 provided that the punishment for rape, as

sault with intent to rape, or attempted rape upon

a free white woman is death. Id., Art. 819 and

Art. 823, 562-63.

V irginia:

whites: An act passed in 1819 provided that the pun

ishment for rape shall be imprisonment for a

term not less then ten nor more than twenty-one

(21) years. Revised Code of the Laws of Vir

ginia, Vol. I, 585 (1819). A Code published in

1860 states that rape is punishable by imprison

ment for not less than ten nor more than twenty

(20) years. Code of Virginia (2d ed.) 785 (1860).

slaves and free negroes: The act of 1819 provided that

in the case of slaves, the punishment for rape shall

11a

be death and the punishment for attempted rape

upon a white woman shall be castration. Revised

Code of the Laws of Virginia, Vol. I, 585 (1819).

The Code of 1860 provided that in the case of

slaves, rape upon or attempted rape upon a white

woman shall be punished by death, and in the

case of free negroes, rape upon or attempted rape

upon a white woman shall be punished by death

or by imprisonment for not less than five nor

more than twenty (20) years, at the discretion of

the jury. Code of Virginia (2d ed.) 815-16 (1860).

MEiLEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C. 219