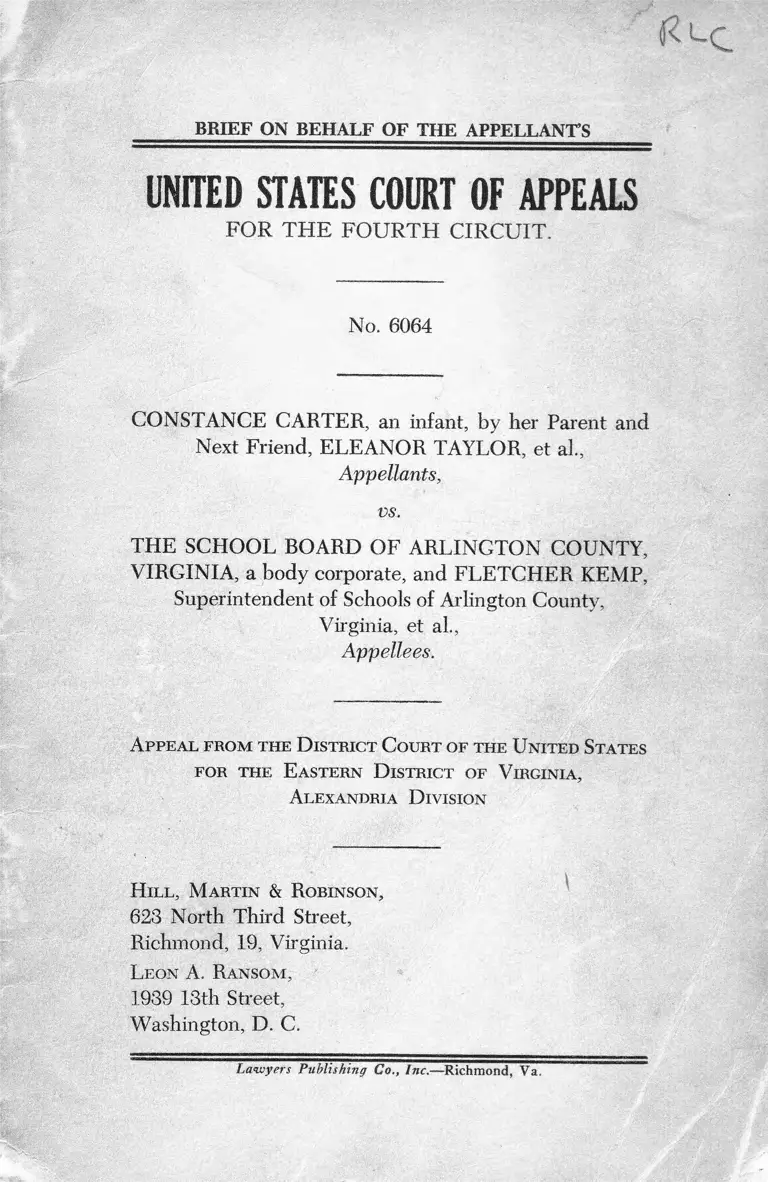

Carter v. School Board of Arlington County, Virginia Brief on Behalf of Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1950

50 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Carter v. School Board of Arlington County, Virginia Brief on Behalf of Appellants, 1950. a991d8fa-ac9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1dc9b362-f1c3-41bc-b3ce-ce2bea0584af/carter-v-school-board-of-arlington-county-virginia-brief-on-behalf-of-appellants. Accessed February 27, 2026.

Copied!

BRIEF ON BEHALF OF THE APPELLANTS

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR TH E FOURTH CIRCUIT.

No. 6064

CONSTANCE CARTER, an infant, by her Parent and

Next Friend, ELEANOR TAYLOR, et al.,

Appellants,

vs.

THE SCHOOL BOARD OF ARLINGTON COUNTY,

VIRGINIA, a body corporate, and FLETCHER KEMP,

Superintendent of Schools of Arlington County,

Virginia, et al.,

Appellees.

Appeal from the District Court of the United States

for the E astern District of Virginia,

Alexandria Division

Hill , Martin & Robinson,

623 North Third Street,

Richmond, 19, Virginia.

L eon A. Ransom,

1939 13th Street,

Washington, D. C.

Lawyers Publishing Co., Inc.—Richmond, Va.

SUBJECT INDEX

PAGE

Statement of the Case ............................. ...................................... 2

Questions Involved ................................................. ...................... 4

Statement of the Facts ......................... ......................................... 5

Argument ............................................................................ 10

I. The Legal Principles ................................................... 10

II. Appellees Are Discriminating Against Appellants

By Refusing and Failing to Afford Them High

School Opportunities, Advantages and Facilities,

Including Curricula, Equal to Those Afforded

White Children Similarly Situated ...... 12

A. Physical Plants, Facilities and Equipment..... 12

Shops ........................................................................ 13

General Shop ................................................. 13

Auto Mechanics Shop ................................ 13

Mechanical Drawing Room ........... 14

Machine Shop ......... 14

Sheet Metal Shop ........................... 14

Printing Shop .......... 14

Wood Shop ................. 14

Science Laboratories .................. 15

Libraries—Rooms ................................................. 16

Holdings of Books and Periodicals ......... 17

Music Rooms ............................. IS

Art Rooms ........................................ -................... 19

Commercial Facilities and Equipment ......... 19

Typewriting Rooms .................................... 19

Bookkeeping Rooms .................................... 19

Auditoriums ....... 20

Gymnasiums ......................................................... 20

Athletic Fields and Outdoor Facilities ........... 22

Cafeterias ............................................................. 22

Distributive Education Rooms ........................ 23

Guidance Offices ................................................. 23

Infirmary Facilities ....... 23

Teachers’ Rest Rooms ......................................... 23

Administrative Facilities .................................... 24

Grounds ................................................................. 24

Classrooms .......... 25

Sanitary Facilities................................................. 25

SUBJECT INDEX-Continued

PAGE

B. Curricula ............................................................... 26

Courses of Study.................................................- 26

Alteration of Courses.................................. 28

Grouping of Classes .................................... 28

Vocational Courses ....................................... 29

Summer School .............................. 30

Guidance ............................................................... 30

Co-Curricular Activities .................................... 30

Honorary Awards ................................................. 31

C. Teachers ................................................................. 32

Number of Teachers ......................................... - 32

Teaching Experience ........................................... 32

Teachers’ Salaries .......... ................................... - 33

Number of Different Subjects Taught.... ......... 33

D. Accreditation ......................................................... 34

III. The Discrimination Against Appellants Cannot Be

Justified By Reason of the Smaller Number of

Negro High School Pupils, as Compared With The

Number of White High School Pupils, in Arling

ton County, or By The Comparative Expenditures

or Investments Made For Education in the High

Schools of Said County............................................... 35

IV. The Discriminations Against Appellants as to

Courses of Instruction Cannot be Justified by the

Claimed Failure of Negro Pupils to Specifically

Demand the Establishment of Such Courses at

the Negro High School ....................................... 36

V. Appellees Are Discriminating Against Appellants

By Requiring Them to Avail Themselves of High

School Facilities Outside Arlington County, While

Affording White Children Similarly Situated Such

Facilities Within Said County .......... 39

Plant Facilities and Equipment .......................... 40

Shops .....................................................................

Science Laboratory .......................--------------- 40

Library ..................................... 41

Auditorium ............................................................. 41

Dining Room .............-........................................... 41

Courses of Study........................................... 42

Conclusion ............................................................... 44

T a ble o f C ases

Alston v. School Board, 112 F. 2d 992 (C. C. A. 4th, 1940 ..... 11

Ashley v. School Board of Gloucester County, 82 F. Supp.

167 (E. D. Va., 1948) .................................................10, 11, 12

Carter v. School Board of Arlington County, 87 F. Supp. 745

(E. D. Va, 1949) ......................................... ........................... 3

Corbin v. County School Board of Pulaski County, 177 F.

2d 924 (1949).................................. ................. .......10. 11, 12, 43

County School Board of Chesterfield County v. Freeman,

171 F. 2d 702 (C. C. A. 4th, 1948)........................................ 11

Fisher v. Hurst, 333 U. S. 147 (1948) ........................................ 37

McCabe v. Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway Co., 235

U. S. 151 (1914) ....................................................................... 35

Missouri ex rel Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S.

337 (1938) ......................................................................10, 35, 44

Mitchell v. United States, 313 U. S. 80 (1941) ........................ 35

Pearson v. Murray, 169 Md. 478, 182 A. 590 (1936) ................ 10

Piper v. Big Pine School District, 193 Cal. 664, 226 P. 926

(1924) ........................................................................................ 44

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 631 (1948) ................TO, 37

Smith v. School Board of King George County, 82 F. Supp.

167 (E. D. Va., 1948) ...................................................10, 11, 12

Wrighten v. Board of Trustees, 72 F. Supp. 948 (E. D. S. C.,

1947) .......................................................................................... 10

C o n stitu tio n s C ited

United States Constitution, Fourteenth Amendment..... 2, 10, 37

Virginia Constitution, Article IX, Section 1 40 ......................... 11

P rin c ipa l Sta tu tes C ited

United States Code:

Title 8, Section 41 ................................................................ 2, 11

Title 8, Section 43 ................................................................ 2, 11

Code of Virginia; 1950:

Title 22, Section 22-221 ......................................................... 11

SUBJECT INDEX-Continued

PAGE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FO R TH E FOURTH CIRCUIT.

No. 6064

CONSTANCE CARTER, an infant, by her Parent and

Next Friend, ELEANOR TAYLOR, et al.,

Appellants,

vs.

THE SCHOOL BOARD OF ARLINGTON COUNTY,

VIRGINIA, a body corporate, and FLETCHER KEMP,

Superintendent of Schools of Arlington County,

Virginia, et al.,

Appellees.

Appeal from the District Court of the United States

for the E astern District of Virginia,

Alexandria Division

BRIEF ON BEHALF OF THE APPELLANTS

[ 2 ]

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This is an appeal from a final judgment of the District

Court of the United States for the Eastern District

of Virginia in a case arising under the Constitution and

laws of the United States, wherein appellants, plain

tiffs below, are seeking a declaratory judgment and a

permanent injunction.

On September 4, 1947, appellant Constance Carter,

an infant Negro child, residing in the County of Ar

lington, Virginia, by her mother, filed her original

complaint (R. I ) 1 alleging that appellee School Board

of Arlington County, Virginia, and Fletcher Kemp, the

then Division Superintendent of Schools of Arling

ton County, Virginia, original defendants below, have

pursued and are pursuing, the policy, practice, custom

and usage of denying, on account of her race or color,

said appellant and other Negro children similarly sit

uated, educational opportunities, advantages and fa

cilities equal to those afforded white children similar

ly situated, and thereby have denied, and are denying,

her and them the equal protection of the laws secured

by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States, the rights secured by Sections

41 and 43 of Title 8 of the United States Code, and the

rights secured by the Constitution and laws of the

Commonwealth of Virginia. Both the original com

plaint, and the amended complaint (App. 1) filed Oc

tober 15, 1947, seek a judgment declaring that the

policy, custom, practice and usage aforesaid are vi

olative of the Constitution and laws aforesaid, and a

1. References are to the appendix page numbers where the portion

of the record referred to is printed therein, and, otherwise, are to the

record page numbers.

[ 3 ]

permanent injunction restraining and enjoining said de

fendants from making such distinctions or any distinc

tion based upon race or color in the opportunities, ad

vantages or facilities provided by them for the edu

cation of white and Negro children residing in said

County, or, in the alternative, a permanent injunction

restraining defendants from denying plaintiff, and those

on behalf of whom she sues, admission to and enroll

ment in the high school maintained and now used

exclusively for white pupils.

On September 30, 1947, said defendants filed an

answer (R. 9) which in substance denied that racial

discrimination is practiced. Subsequently, defendant

Kemp’s term of office expired (R. 650) and appellee

William A. Early, his successor, was duly substituted

as a defendant (R. 32).

On October 24, 1949, appellants Julius Brevard and

Peggy Council, each an infant Negro child, residing in

Arlington County, by their respective parents, filed

their petition (App. 12) seeking intervention as plain

tiffs, the petition alleging their own experiences in un

successfully seeking educational opportunities, advan

tages and facilities, and praying for the same relief

sought in the original and amended complaints. In

tervention was duly permitted (R. 1276).

On September 6-9, 1949, and on October 24-26,

1949, the Court below heard evidence and oral argument.

On December 7, 1949, the Court rendered a written

opinion (App. 343), reported at 87 F. Supp. 745, in

which appeared the Court’s findings of fact and conclu

sions of law, and on December 12, 1949, entered final

judgment (App. 364), dismissing the complaint.

[ 4 ]

QUESTIONS INVOLVED

1. Are appellees discriminating against appellants

by refusing and failing to afford them high school edu

cational opportunities, advantages and facilities, includ

ing curricula, equal to those afforded white children

similarly situated?

2. Can the discriminations against appellants be

justified by reason of the smaller number of Negro

children of high school age, as compared with the num

ber of white children of high school age, enrolled in

high schools in Arlington County, or by the compara

tive expenditures or investments made by appellees for

education in the white and Negro high schools, re

spectively, of said County?

3. Can the discriminations against appellants as to

courses of instruction afforded or taught in high schools

be justified by the claimed failure of Negro children

to specifically demand the establishment of such courses

at the Negro high school?

4. Are appellees discriminating against appellants

by requiring them to avail themselves of high school

facilities outside Arlington County, while affording white

children similarly situated high school facilities within

Arlington County?

The first three questions are raised in the record by

the original complaint (R. 1), the amended complaint

(App. 1), the answer (R. 9 ), and the pettion for in

tervention (App. 12). All questions are raised in the

record by the proceedings at the hearings (App. 86-

89, 141-144, 195-200, 224-230, R. 248-251, 270-271),

the argument, and the opinion of the Court (App.

343). The fourth question is additionally raised in the

[ 5 ]

record by appellants’ objections (R. 829-838) and mo

tion to strike (R. 891-893 ) at the hearings.

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS

Appellants are Negroes, are citizens of the United

States, of the Commonwealth of Virginia, and are res

idents of and domiciled in Arlington County. At the

time the original complaint was filed, and at the time

the amended complaint and the petition for interven

tion were filed, the appellants were all within the statu

tory age limits for eligibility to attend public schools

and satisfied all requirements for admission thereto.

Their respective parents are Negroes, are citizens of

the United States, of the Commonwealth of Virginia,

and are residents of and domiciled in Arlington Coun

ty. They are taxpayers of the United States and of

said County and Commonwealth, and are and were re

quired by law to send their respective children to

school.

Appellee School Board of Arlington County, Virginia,

exists pursuant to the Constitution and laws of the

Commonwealth of Virginia as an administrative depart

ment discharging governmental functions, and is de

clared by law to be a body corporate. Appellee Wil

liam A. Early is Division Superintendent, and holds

office pursuant to the Constitution and laws of the

Commonwealth of Virginia, as an administrative of

ficer of the free public school system of Virginia.

The public schools of Arlington County are under the

control and supervision of appellees, acting as an ad

ministrative department or division of the Common

wealth of Virginia. Said appellee School Board is under

[ 6 ]

a duty to enforce the school laws of Virginia, to main

tain an efficient system of public schools in Arlington

County, to determine the studies to be pursued, the

methods of teaching, and to establish such schools as

may be necessary to the completeness and efficiency

of the school system. Appellee William A. Early, as

Division Superintendent, has the immediate control

and operation of the public schools in Arlington Coun

ty.

The only two schools of Arlington County directly

involved in this case are the Washington-Lee High

School and the Hoffman-Boston High School.2 The

former is operated for the exclusive use of white pupils,

and the latter for the use of Negro pupils (App. 84,

244, 248; R. 37, 884, 887, 888).

Washington-Lee is predominantly a senior high school,

with 1881 senior high school pupils in its total enroll

ment of 2377 ( R. 38, 87). It has no elementary pupils

(R. 38, 87). Hoffman-Boston, on the other hand, is

predominantly an elementary-junior high school, with

only 48 senior high school pupils in its total enroll

ment of 270 (R. 38, 87).3

In the past, Negro high school pupils residing in

Arlington County have largely attended schools in the

District of Columbia to obtain courses and facilities

available to white pupils at Washington-Lee, but lack

ing at Hoffman-Boston (App. 84, 85; R. 652-653, 671-

673, 740). A number of these pupils pursued Vo-

2, There are 5 secondary schools in the Arlington school system.

The other three schools are white junior high schools, namely, Claude

Swanson, Dolly Madison, and Thomas Jefferson (R. 37).

3. During 1946-47, the Arlington School Board paid the tuition of

21 Negro pupils who were attending senior high schools in the District

of Columbia ( App. 85; R. 37). The exact number of Arlington Negro

pupils attending schools outside Arlington is unknown.

[ 7 ]

eational courses (R. 740). The District of Columbia

in recent years started charging tuition on Arlington

pupils, and Negro pupils appealed to the Arlington

School Board for payment of tuition (R. 653, 655).

During the 1946-47 session, Arlington paid the tui

tion of 21 Negro pupils (App. 85; R. 37) and, dining

the 1947-48 school session, agreed to pay, and in fact

paid, tuition on all pupils involved (R. 652-653, 740,

755). During the 1948-49 session, the School Board

decided that it would pay tuition only on Negro seniors

who had already completed three years of work in

District of Columbia schools (R. 653-654, 755).

Appellant Constance Carter originally attended high

school in the District of Columbia because of lack of

facilities and courses at Hoffmau-Boston (App. 17-

18). At the opening of the 1947-48 school session,

she, accompanied by her mother and attorney, con

ferred with the principal of Hoffman-Boston in an effort

to obtain certain courses there (App. 19-21; R. 669,

773). While the evidence is conflicting as to the courses

then sought and the details of the conversation,4 it is

uncontroverted that courses in Typewriting and Physi

cal Education were among those requested (App. 21-

22), that Hoffman-Boston then had only 8 typewriters,

an insufficient number, and no typing tables or chairs

(App. 21, 234-235; R. 775-776, 795-796), and that Physi

cal Education was taught by regular classroom teachers

not certificated in that subject (R. 43-44, 671, 774, 795).

She then sought the desired courses at Washington-

Lee, but admission was denied because she is a Negro

(App. 22; R. 670). She thereupon entered Dunbar

4. Appellants’ evidence was to the effect that the principal stated

that the courses requested were not available at Hoffman-Boston (App.

19-22).

[ 8 ]

High School, in the District of Columbia, until she

later entered Hoffman-Boston (App. 19; R, 266-287,

777-778, 797-798). Her mother has been forced to

pay tuition for her attendance in the District of Co

lumbia (App. 18-19; PL Ex. 73, 74, 75, 76).

Appellant Peggy Council attended junior high school

and obtained a part of her senior high education in

the District of Columbia (App. 211, 221; R. 1144-1145,

1148-1151). Arlington paid her tuition, but after it

ceased doing so she could not pay it herself (App. 212,

222), but entered Hoffman-Boston at the beginning

of the 1948-49 session as a pupil in grade 1G-B ( App.

212, 277; R. 631, 1149, 1150). She desires to enter

a nursing school (App. 282) and 2 years of Latin

is prerequisite for admission (App. 218-219, 282, 315; R.

645,1100-1101,1159-1160). When attending senior high

school in the District of Columbia, she filled out an

elective sheet, which the principal of Hoffman-Boston

later received, upon which she requested a course in

Latin (App. 280). When she first entered Hoffman-

Boston, she conferred with the principal, advising of

her need for Latin, and was assured that she would

be given a year and one-half of Latin at Hoffman-

Boston, and that he would see that she would be ad

mitted to a school in the Distinct of Columbia, after

her graduation from Hoffman-Boston, at which she

would be given an additional one-half year of Latin

(App. 220-221, 222, 279, 281; R. 645). In May, 1949, she

filled out another elective card upon which she requested

for the 1949-50 session, courses in Spanish and Short

hand (App. 278; R. 801), which card she personally

delivered to the principal (App. 280). At this time,

she did not understand that Latin would be offered at

Hoffman-Boston for said session (App. 281). In

June, 1949, being advised that Latin would be avail

able, she made out another elective sheet, which she

delivered to her home room teacher, upon which she

also requested Latin, Chemistry and Shorthand. (App.

212-218, 280-281). About two weeks before the close of

the 1948-49 session, she conferred with the principal

relative to her program for 1949-50 and advised him

of her desires in order that her program might be

worked out (App. 216). She also needs Chemistry

for her nursing career (App. 282-283). She first sought

this course during the 1948-49 session (App. 237-238).

She has not been afforded Latin at Hoffman-Boston, be

cause it has not been taught there since she entered

(App. 213, 222, 278, 282; R. 645). She has not been able

to get either Spanish or Chemistry because these are

alternating courses at Hoffman-Boston, and no Chem

istry has been taught since she has been there (App.

213, 282; R. 802), and the only course in Spanish

taught while she was there was an advanced course

in Spanish (App. 214; R. 802). No class in Shorthand

was afforded her until the early part of October of

the current school year (App. 278; R. 802, 1151).

Appellant Julius Brevard attended Armstrong Techni

cal High School, in the District of Columbia, during

the 1948-49 session, taking, among other courses, blue

print reading which included drafting and automo

bile mechanics (App. 208; R. 629). Unable to pay

tuition there (App. 211), he entered Hoffman-Boston

at the beginning of the 1949-50 session, and on the

first day requested of the principal a course in auto

mobile mechanics (App. 208-209; R. 628-629, 789).

The principal advised him that Hoffman-Boston did

[10J

not have the course, and that he did not know when

it would have it (App. 208-209; R. 620, 789). The

answer led him to believe that no effort would be made to

obtain the course for him (App. 209). He has not

been afforded this course (App. 209), and there never

has been a time when anyone at Hoffman-Boston ask

ed him what he desired to take (App. 210).

Since the remaining facts are so interrelated to the

decision of the legal issue, complete statements of the

facts as to specific matters are, for convenience, made

in connection with the appropriate portions of the argu

ment, and, to avoid repetition, are omitted here.

ARGUMENT

I

T h e L e g a l P r i n c i p l e s

The controlling legal principles are so well settled

as not to require extended discussion. The refusal

or failure of an agency of the state to afford its Negro

citizens, because of their race or color, educational

opportunities, advantages and facilities equal in all re

spects to those afforded persons of any other race or

color is a denial of the equal protection of the laws

secured by the Fourteenth Amendment of the Con

stitution of the United States,5 * * * and of the rights se

cured by laws of the United States enacted pursuant

5. Sipuel v. Board o f Regents, S32 U. S. 631 (1948); Missouri ex

rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337 (1938); Corbin v. County School

Board o f Pulaski County 177 F. 2d 924 (C. C. A. 4th, 1949,

Smith v. School Board of King George County, 82 F. Supp. 167 (E , D.

Va., 1948); Ashley v. School Board o f Gloucester County, 82 F. Supp.

167 (E. D. Va., 1948); Wrighten v. Board o f Trustees, 72 F. Supp. 948

(E . D. S. C., 1947); Pearson v. Murray, 169 Md. 478, 182 A 590

(1936).

[ 1 1 ]

thereto,6 and by the Constitution and laws ur the

Commonwealth of Virginia.7 It is beyond question that

the appellees in this case are subject to the constitution

al and statutory mandates.8

In Virginia, separate schools are maintained for white

and Negro pupils, respectively.9 * These provisions not

only constitute the sole reason for denying admission

of Negroes to Washington-Lee (App. 225, 244, R. 708,

884, 887), but also have necessarily made Washington-

Lee a large school and Hoffman-Boston a small school

(App. 249, 267; R. 85-86), which, in turn, has brought

about many of the differentials between the two schools

(App. 249, 267; R. 85-86). In these circumstances,

it is clear that all of the discriminations and inequalities

suffered by Negro pupils residing in Arlington County

follow as a consequence of their race, which the law

makes the sole criterion as to the school which they

may attend (App. 225, 248; R. 884, 887).

Both appellees and the Court below assumed that this

case must be decided upon an assumption that the sep-

8. REV. STAT. Sec. 1977, 1979, 8 U. S. C. Sec. 41, 43; Smith v.

School Board o f King George County, 82 F. Supp. 167 (E. D. Va., 1948),

cited supra note 5; Ashley v. School Board o f Gloucester County,

82 F. Supp. 167 (E . D. Va., 1948), cited supra note 5.

7. The Constitution of Virginia (Art. IX, Section 140) provides;

“White and colored children shall not be taught in the same school.”

The Code of Virginia of 1950 (Title 22, Section 22-221) provides:

“White and colored persons shall not be taught in the same school, but

shall be taught in separate schools, under the same general regulations

as to management, usefulness and efficiency.” While the constitutional

provision does not expressly provide for equality as does the statute,

it is necessarily to be construed as if it did, for otherwise its invalidity

would be plain. See cases cited supra note 5.

8. Corbin v. County School Board of Pulaski County, 177 F. 2d 924,

(C. C. A. 4th, 1949), cited supra note 5; County School Board o f

Chesterfield County v. Freeman, 171 F. 2d 702 (C. C. A. 4th, 1948);

Alston v. School Board, 112 F. 2d 992 (C. C. A. 4th, 1940).

9. VA. CONST. Art. IX, Sec. 140; VA. CODE (1950) Title 22,

Sec. 22-221, both cited supra note 7.

[ 1 2 ]

arate school laws of Virginia fix a rigid pattern within

the framework of which the rights of appellants, and

other Negro children residing in Arlington County, must

be determined. But in situations where unequal edu

cational opportunities and facilities are afforded Negro

pupils,10 the invalidity and inapplicability of segrega

tion laws is well settled, and the mandates of the Con

stitution and laws of the United States cannot be

avoided by resort thereto.11

As the rights of appellants are measured by the test

of equality, a determination of the issues necessarily

involves a comparison of the opportunities, advantages

and facilities which Arlington County affords its white

and Negro pupils resident therein.12

II

A p p e l l e e s A r e D is c r im in a t in g A g a in s t A p p e l l a n t s

B y R e f u s in g a n d F a il in g t o A f f o r d T h e m H ig h

S c h o o l O p p o r t u n i t i e s , A d v a n t a g e s a n d F a

c i l i t i e s , I n c l u d in g C u r r ic u l a , E q u a l t o

T h o s e A f f o r d e d W h i t e C h il d r e n

S i m i l a r l y S it u a t e d

A. Physical Plants, Facilities and Equipment.

Washington-Lee consists of a three-story brick struc

ture with a one-story shop annex. The main building,

erected in 1925, is of pleasing architectural design, be

lt). Appellants do not concede the validity of segregation laws under

any circumstances.

11. See cases cited supra note 5.

12. Corbin v. County School Board o f Pulaski County, 177 F. 2d 924

(C. C. A. 4th, 1949), cited supra note 5; Smith v. School Board o f

King George County, 82 F. Supp. 167 E. D. Va., 1948, cited supra

note. 5; Ashley v. School Board of Gloucester County, 82 F. Supp.

167 (E . D. Va., 1948), cited supra note 5.

[ 1 3 ]

mg trimmed and embellished with limestone. It has

approximately 64 classrooms and the facilities here

after described. Adjacent to the buildings is the spa

cious athletic stadium. The entire plant occupies a

site of 11.9 acres. Its total cost was $925,988. (R.

59, 101, 119, 241, 731, 940).

Hoffman-Boston consists of a two-story brick build

ing and a one-story shop annex. The building con

structed in 1923, is of plain construction unadorned by

architectural details. It has 6 regular size classrooms

and one smaller room that can seat only 18 pupils. The

grounds around the school are unimproved, and there

is no athletic stadium or facilities. The entire plant

occupies a site of 5.7 acres. Its total cost was $109,966.

App. 239; R. 59-60, 101, 119, 731, 940).

That Hoffman-Boston is tremendously inferior to

Washington-Lee in the matter of physical plant, fa

cilities and equipment13 is apparent from a compari

son of physical plant, facilities and equipment of the

two schools:

Shops: Washington-Lee has 7 separate shops, as fol

lows:

—General Shop: Ample area, orderly arrangement

(App. 61-62), equipped with universal saw, band saw,

2 jig saws, belt sander, drill press, 4 lathes, grinder,

jointer, and stock of small tools (App. 61-62; R. 63,

124, 187; PI. Ex. 53, 54).

—Auto Mechanics Shop: Large area, orderly ar

13. The physical plant and facilities of a secondary school should be

designed in such fashion that it will promote attainment of the edu

cational objectives ( R. 59). Equally important is the matter of equip

ment (R. 59, 367, 996). To the extent that physical plant, facilities

and equipment are inadequate, the educational development of the pupils

will be retarded (R. 59).

[ 1 4 ]

rangement, equipped with 3 motor analyzers, 10 prac

tice engines, drill press, valve grinder, armature lathe,

chain hoist, battery charger, air compressor, speedome

ter, and stock of small tools (App. 62-63; R. 63, 124,

187; Pi. Ex. 51, 52). Also has a trainer-type airplane

(App. 62-63; R. 245) and dual control automobile for

driver training (App. 62-64; R. 245).

—Mechanical Drawing R oom : Ample area, orderly

arrangement. Equipped with specially designed draw

ing tables, stools, drawing boards, blueprint machine,

shop library, and stock of small equipment (App. 63-

64; R. 63, 124, 187; Pi. Ex. 55).

—Machine Shop: Large area, orderly arrangement.

Equipped with 11 lathes, 5 milling machines, 3 drill

presses, forge, electric grinder, electric hack saw, arc

welder, shaper, and stock of small tools (App. 64-65;

R. 63, 124, 187; Pi. Ex. 56, 57). Also has a Link train

er for aviation training (App. 64-65; R. 63, 187; Pi. Ex.

56, 57).

—Sheet Metal Shop: Ample area, orderly arrange

ment. Equipped with forming roll, brakes, shear, fold

er, 9 crimping machines, and stock of small tools (App.

65; R. 63, 124, 188; Pi. Ex. 58).

—Printing Shop: Ample area, orderly arrangement.

Equipped with 3 presses, paper cutter, virkotype ma

chine, 4 cases of type, and stock of small tools (App.

65; R. 64, 124, 188; PL Ex. 61, 62).

—W ood Shop: Large area, orderly arrangement.

Equipped with 3 lathes, band saw, planer, 2 universal

saws, radial bench saw, 2 jointers, 2 sanders, 2 drill

presses, jig saw, and stock of small tools (App. 66;

R. 64, 124, 188; Pi. Ex. 59, 60). The machines are

[ 1 5 ]

connected to an expensive sawdust-disposal system ( App.

66; PI. Ex. 59, 60).

Each of these shops is well designed, lighted and

ventilated, and samples of work done in them evi

dence their effectiveness and the caliber of instruc

tion in them (App. 65-68). The cost of the shop build

ing was $110,000, and the cost of its equipment was

$21,000 (R. 102).

HofFman-Boston has only one shop — a general shop

(App. 61; R. 63, 187, 243; Pi. Ex. 67, 68). It con

sists of only one room (App. 61, 62-63, 70; R. 63,

187). Its space is inadequate. Its equipment consists

in 2 lathes, a universal saw, jig saw, post drill, grinder,

jointer, belt sander, band saw, drill press, and a stock

of small tools (R. 63, 188; Pi. Ex. 67, 68). It has no

machines or tools for instruction in Automobile Me

chanics or Printing (App. 62-65, 67-68, 70-71, 172-

173; R. 63, 187, 243-245, 247, 739-740, 969-970), and

no machines and little or no tools for instruction in

Machine Shop, Sheet Metal, Wood Shop, or Mechani

cal Drawing (App. 64-66, 172-173; R. 244-246). In

struction in these courses at Hoffman-Boston would

be impossible (App. 109). The cost of its building,

which also houses the Home Economics department,

was only $37,500, and of its equipment $2,000 ( R. 102).

Science Laboratories-. Washington-Lee has 4 science

laboratories:14 a Physics laboratory, a Chemistry lab

oratory, and 2 Biology laboratories (App. 50-52, 52-

53, 106-107; R. 61-62, 183-186; Pi. Ex. 29, 70). Each

laboratory is furnished with the necessary desks and

14. Thus, the courses in Biology, Chemistry and Physics can each

be conducted in a separate laboratory. This is superior to the practice

of teaching different science courses in a single laboratory or room (App.

54, 74; R. 368-371).

[ 1 6 ]

demonstration tables, all equipped with the necessary

gas, water and electric connections (R. 61; Pi. Ex. 29).

The Physics laboratory has cases for equipment, while

each of the other S laboratories is equipped with a

store room for materials and equipment (R. 61). Each

laboratory has an ample stock of apparatus, equipment

and supplies (App. 51-53, 107-108; R. 237). The cost

of its equipment was $34,501 (R. 102).

Holfman-Boston has only one science room in which

all of such sciences as are at that school are taught

(App. 52-53, 106-107; R. 61, 236; Pi. Ex. 6, 7). Its

stock of apparatus, equipment and supplies is much

less substantial and varied than that at Washington-

Lee (App. 53-54, 106-108, 191-192; R. 61-62, 183-186).

The cost of its equipment was only $1,934 (R. 102).

Libraries-Rooms: The library at Washington-Lee con

sists of a main reading room, reference room, magazine

room and work room (App. 46-47, 60, 128, 232; Pi.

Ex. 24, 25). It was originally designed for use as a

library (R. 60). It is adequately lighted (App. 46-

47; R. 60, 128) and ventilated (R. 128), is sound

proofed (R. 128), has a 20 foot ceiling (R. 128), and

is very attractive (App. 46-48). It has 3480 square

feet (R. 128). It is amply equipped with all of the

modern furniture and equipment usual in school li

braries (R. 60, 137), costing $3,921 (R. 102).

The library at Holfman-Boston consists of one room

(R. 60, 128, 233; Pi. Ex. 24, 25). It was not originally

designed for use as a library, but was made by com

bination of two rooms of classroom size (R. 60, 719).

Its low 13 foot ceiling does not afford proper ventila

tion (App. 182-183; R. 606-609). It has no sound

proofing (R. 128). It is not attractive (App. 48, 180-

[ 1 7 ]

183). It has 1617 square feet (R. 128). Its furniture

and equipment is smaller in quantity than Washington-

Lee’s, and does not include a newspaper rack or fil

ing cabinets which are found at Washington-Lee (App.

183; R. 60, 137), and only 6 of its 24 drawers in its

card catalog drawer are being used at all for cataloging

purposes (App. 183).

Additionally, the library at Hoffman-Boston is situ

ated immediately next to the auditorium (App. 182-

183; R. 945), and the principal’s office is located in the

library workroom in the comer (App. 181-183).

These, coupled with lack of soundproofing, and its low

ceiling, makes it noisy (App. 182-183, 184-185; R. 606-

609). Its low ceiling height, in relation to the size

of the room, and the positioning of the principal’s

office, detract from its aesthetic value (App. 180-183;

R. 607, 608).

—Holdings of Books and Periodicals: Washington-

Lee’s library contains 8,682 volumes of books and 90

subscriptions to periodicals. (App. 322; R. 179-181).

The library at Hoffman-Boston contains only 1,07 i vol

umes for the entire junior-senior high school depart

ment, and 21 periodical subscriptions (App. 322; R.

179). The book holdings at Washington-Lee cost $12,-

000 ( R. 102), are well diversified and many have recent

copyright dates (App. ............, 146-147). Such books

as Hoffman-Boston’s library has cost only $1,921 (R.

102), and in 1947-48 were generally very old books,

many of which had been donated by other libraries

(App. 146-147). Additions to the Hoffman-Boston li

brary since that time, while helpful, do not make it

[ 18 ]

equal to the Washington-Lee library (App. 147-148).15

Music Rooms-. Washington-Lee has two specially

equipped facilities for instruction in Music. The first

is the Choral Room (App. 48-49; R. 60, 126, 234, 977;

PL Ex. 71), a large special room with a capacity of

63 (R. 126). It is equipped with a director’s stand,

a grand piano, movable chairs, filing cabinets, book

shelf (App. 48-49). It has hung paintings on the

wall (PL Ex. 71), Celotex block ceiling (R. 126), and

the room is well soundproofed (R. 126). An adjoin

ing room is lined with cabinets for storage of instru

ments (App. 48-49).

Washington-Lee also has an auditorium specially

designed for band and orchestra instruction (App. 31-

32; R. 60, 126, 223, 977; Pi. Ex. 72). This has a stage

(App. 31-32; R. 223), music stands (App. 31-32), ad

equate storage space (App. 48-50) and about 100 mov

able chairs (App. 31-32). This room can also be used

as a multi-purpose room (App. 31-32). There is also

another instrument storage room (R. 126).

Hoffman-Boston has no studio, auditorium or other

special room for instruction in Music (App. 31-32, 99-

100, 190-191; R. 60, 126, 223, 234-235, 977). The

Music classes meet in a very small room which was

formerly used as the principal’s office (App. 32, 49-

50; R. 126, 361-362; Pi. Ex. 11), which has no stage

(App. 32), piano (App. 50-51), or storage space (App.

49-50) and is too small for a band or orchestra (App.

102-103; R. 361-362).

15. The American Library Association Report, universally accepted

as a standard, establishes a minimum of 2,000 volumes for the

smallest possible high school unit (App. 179, 180). While Washington-

Lee needs more duplicate copies, Hoffman-Boston would need substan

tially the same number of books and periodicals to compare favorably

with it (App. 105, 110-112, 178-180; R. 54).

[ 1 9 ]

Art Rooms: Washington-Lee has two rooms employed

for instruction in Art. One is the Art Studio, which is

excellently lighted and ventilated (R. 129), and equip

ped with adequate and special facilities for instruction

in Art, including adjustable swinging easels which great

ly facilitate drawing, (App. 25-27; R. 60, 129, 2.17;

Pi. Ex. 40). There is also another separate Art facility

(R. 129).

Holfman-Boston has no Ail Studio or room, or equip

ment the same or similar to that at Washington-Lee

(App. 26-27, 99-100, 102-103, 190-191; R. 60, 129,

217).

Commercial Facilities and Equipment — Typeioriting

Rooms: Washington-Lee has two large rooms specially

equipped for instruction in Typewriting, (App. 57; Pi.

Ex. 37, 38), including an ample number of typewriters,

special typing tables and chairs, a mimeograph machine

and a mimeoscope (App. 33, 57-59, 257). Holfman-

Boston utilizes one small room which is not specially

equipped for Typewriting (App. 57-58; Pi. Ex. 10).

It has a small numper of typewriters (App. 239; R.

182), no mimeograph machine (App. 57; R. 182) or

mimeoscope (R. 182), and simple folding chairs serve

as typing chairs (App. 59).

—Bookkeeping Rooms: Washington-Lee has a sep

arate room equipped with special equipment for in

struction in Bookkeeping (App. 34-35; R. 223; Pi. Ex.

39), including bookkeeping desks, typewriters, adding

and calculating machines and other equipment (App.

34-35, 113; R. 223-224). Holfman-Boston has no spe

cially equipped room for instruction in Bookkeeping,

or machines, or other equipment of the same type or

f 20 J

similar to that at Washington-Lee (App. 35-36, 113;

R. 182, 224, 996).

Auditoriums: Washington-Lee has a large, modern main

auditorium, with balcony (App. 28; R. 60, 123, 952),

comfortable fixed-type oprea seats (App. 28, 250; R.

60, 952), projection booth (App. 29; R. 60, 123, 952),

slanting floor (R. 388), a deep stage with draw cur

tains (App. 28-29, 250-251; R. 60, 220), and a seat

ing capacity of 1151 (R. 123; Pi. Ex. 17). The girls’

gymnasium, hereafter discussed (post, pp. 20-21), is

immediately behind the stage (App. 28; R. 220).

At Hoffman-Boston, a large room, with a flat floor,

is used as an auditorium (App. 31; R. 60, 221, 358;

Pi. Ex. 3). The seats are folding chairs (App. 29-

30, 250; R. 60, 222, 798-799, 952). It has a small

elevated platform rather than a stage (App. 29-30;

R. 60, 221, 944). It has no balcony (R. 952), fa

cilities for motion pictures (App. 252; R. 60-221) and

can seat only 300 persons (App. 29; R. 123). The

ceiling is only 14 feet high (R. 798) and posts sup

porting it obstruct vision (App. 30). A small room

on one side of the platform is used for storage, and an

other on the other side is used as the women teachers’

rest room (App. 56, 119; R. 221-222, 239).

Gymnasiums: Washington-Lee has two gymnasiums

(App. 41, 44, 100; R. 60, 123, 228, 230, 724, 944). The

girls’ gymnasium is very large, is located immediately

behind the stage of the main auditorium, being sep

arated from the latter by large sliding doors (App.

28; R. 220; Pi. Ex. 18, 19). These doors can be

opened to permit persons seated in the auditorium

to witness games and other activities in this gym

nasium, or they may be closed to permit separate and

simultaneous use of this gymnasium and auditorium

(App. 76-77; R. 219-220, 952-953). It has seats addi

tional to those in the main auditorium (App. 28; R.

1219). The boys’ gymnasium (Pi. Ex. 28) is also

large, and is capable of a use independent of that

made of the girls’ gymnasium (App. 76-77, 100).

Each gymnasium is well equipped (App. 29, 41-

42, 44), has a basket ball court (App. 29, 41-42. 44;

R. 944), adjoining dressing rooms (App. 42-44; R. 60,

228, 229), team rooms (Pi. Ex. 21), locker rooms (App.

42-44; R. 60, 229, 230, 231, Pi. Ex. 22, 27), shower

rooms (App. 42-44, 152; R. 60, 228; Pi. Ex. 20) and

lavatory facilities (App. 42-44; R. 60). Each can be

used for a wide variety of games and athletic contests

(App. 44; R. 123).

Hoffman-Boston has no gymnasium (App. 40-41, 44,

100-101, 190; R. 231, 681, 799, 944). The so-called

auditorium can only be used for limited calisthenics

(App. 46). It is not in fact a convertible au

ditorium-gymnasium; the ceiling is too low for

gymnasium purposes, the lights hang down too low, the

lights and windows are unprotected ( App. 101), and

the ceiling supports in the floor constitute hazards

(App. 44-45; R. 944). It is too small to permit the

playing of games (App. 44-45, 190) and the seats must

be removed before it can be used at all (App. 45).

It has little or no equipment for gymnastics (App.

190), no basketball court (App. 44-45; R. 896, 944),

dressing, team, locker, shower or lavatory facilities (App.

152; R. 60, 231-232) or other facilities similar to those

afforded at Washington-Lee (App. 100-101; R. 231-

232).

[ 2 2 ]

Athletic Fields and Outdoor Facilities: Washington-

Lee has a large athletic stadium with a graded foot

ball gridiron (App. 27; R. 59, 347, 939a; Pi. Ex. 41),

a track (R. 59), a concrete grandstand (App. 27;

R. 59, 218, 347, 939a) beneath which are team and

shower rooms (R. 218, 939a). This facility is equip

ped with seats on three sides (R. 939a) and artificial

lighting facilities for night events (R. 218). Addi

tionally, there is another smaller field used for soft-

ball and other group games and physical education

activities (R. 688-689), and there are tennis courts (R.

59).

Hoffman-Boston has no stadium, gridiron, track, ten

nis courts, grandstand, team or shower rooms, seat

ing or artificial lighting facilities (App. 27-28; R. 59-

GO, 218, 726, 941-942). It has an open space, which

is not level (App. 27-28; R. 349), not marked off (R.

349) and has too much grade for effective use (App.

27-28; R. 349). The total space available is inade

quate for outdoor recreation (App. 111-112) and it

has no facilities the same or substantially similar to

those at Washington-Lee (R. 218, 942).

Cafeterias: Washington-Lee has a large, modern at

tractive and well arranged cafeteria (App. 34-35, 267;

R. 61, 139, 225, 725; Pi. Ex. 32) with a large seating

capacity (R. 61, 139), amply arranged kitchen (App.

34-35; R. 61) and steam tables (R. 61). In it an

excellent lunch program is conducted (App. 267; R.

139). Hot plate lunches, soups, vegetables, salads, de

serts and beverages are served (R. 139).

Hoffman-Boston has no cafeteria or lunch room fa

cilities or program of any sort (App. 35-36, 99-100, 113-

114, 268; R. 61, 139, 225, 724-725, 799, 849). Chil

[ 2 3 ]

dren attending this school must either go home

to lunch, or bring lunches with them (R. 725, 849).

Each of the three principal witnesses for defendants

testified that this situation was undesirable (App. 267;

R. 691, 849).

Distributive Education Rooms: Washington-Lee has

a Distributive Education Room or office (App. 38-

39; R. 226-227; PL Ex. 43) with facilities, equipment,

and literature available for teachers to work with pupils

with a view to making a correlation between their

school work and actual work in the field, thus facili

tating the transition of the pupil from school to work

(App. 38-39, 115-116; R. 226-227). Hoffman-Boston

has no Distributive Education facilities or equipment

at all (App. 39-40; R. 227).

Guidance Offices: Washington-Lee has a special room

equipped and utilized for pupil guidance (App. 39-

40, 116-117; R. 227; Pi. Ex. 36). In it all guidance

activities can be conducted privately and effectively

(App. 117-118). Hoffman-Boston has no guidance fa

cilities at all (App. 40-41, 116-117: R. 227).

Infirmary Facilities: Washington-Lee has an infirmary

equipped with 6 beds and first aid equipment (App.

110; R. 60, 724). The office of the school health de

partment for the County is located in this building, thus

providing effective emergency service (R. 60). Hoff

man-Boston has no infirmary, clinic, or first-aid room

(App. 110; R. 60, 724).

Teachers’ Rest Rooms: At Washington-Lee there are

several rest rooms for men and women teachers (App.

54-56; R. 61, 122; Pi. Ex. 26, 33, 34). Each is an

impressive, well-equipped facility, with lavatory facili

[ 2 4 ]

ties, lounge chairs and sofas, mirrors and other furni

ture and equipment (App. 55-57; R. 122).

At Hoffman-Boston there are no rest room facilities

at all for men teachers (R. 122), and the single fa

cility for women teachers is a 12 by 6 foot room ad

jacent to the auditorium platform containing a toilet,

a mirror and 4 chairs (App. 55-57, 119; R. 122, 221-

222, 238-239; Pi. Ex. 9). This room is also used as

storage for tumbling mats and other equipment (App.

56-57; R. 239, 342-343). It contains no lounge chairs,

wash basin, coat rack, or other equipment or appoint

ments (App. 57; R. 122), and is also used as a dressing

room for dramatics (R. 122).

Administrative Facilities: Washington-Lee has a large,

well-equipped principal’s office (Pi. Ex. 30), a well-

equipped business office (App. 33; R. 224-225; PL

Ex. 31), and an elaborate intercommunication and

public address system (App. 34; R. 235; Pi. Ex. 30).

Hoffman-Boston has no business office (App. 33-34;

R. 225) or intercommunication or public address sys

tem (App. 34; R. 235, 354). The principal’s office

is in the library workroom, a very small room, with

no outside window or waiting room facilities, meager

equipment, and is noisy and ill ventilated (App. 33-

34, 118-119, 181-182, 183; R. 233, 235, 352-353, 606).

Grounds: Washington-Lee is situated upon a fully de

veloped and well-kept site (Pi. Ex. 63, 64). There

are sidewalks and paved driveways throughout the

grounds (R. 939-940). It is one of the most beautiful

high schools in the state (App. 59-60).

Hoffman-Boston’s school grounds are undeveloped

and are in much need of improvements (R. 942; Pi. Ex.

14, 15, 16). Half of its grounds is unusable (R. 942).

[ 2 5 ]

It is ungraded, has no paved walkways or driveways

on the site (App. 188-189; R. 941). Consequently, mud

and other elements in rainy and other inclement weather

present a health hazard (App. 188-189). There is

no comparison that can be made between the two schools

so far as attractiveness is concerned (App. 36-37, 59-

60, 119-120, 188-189).

Classrooms: Classroom facilities at Washington-Lee

(PL Ex. 35) are superior to those (PL Ex. 12) at Hoff-

man-Boston (App. 36-38). Washington-Lee has rooms

(Pi. Ex. 42), larger than average, which can seat a

large number of pupils, and may be used as resource

or multiple-purpose rooms or for teaching purposes

where assembly of a large group is necessary (App.

37-38).

Sanitary Facilities: Washington-Lee has lavatories for

girls and boys on each floor and for boys in the shop

building (R. 61; Pi. Ex. 23, 44, 45). There are ab-

bexl spray-type industrial washbowls in each shop (R.

61). Hoffman-Boston only has lavatories for girls and

boys on the first floor only, and a toilet for boys boxed

in a comer of the shop (R. 61). Elementary and high

school pupils use the same facilities (App. 192).

PIoffman-Boston is not as well maintained as Wash

ington-Lee (App. 38; R. 226; Pi. Ex. 13, 49). Broken

window panes are in evidence at Hoffman-Boston (R.

242; PI. Ex. 14).

In view of these great differentials,16 the conclu

sion is inevitable that Hoffman-Boston is greatly in

ferior to Washington-Lee in physical plant, facilities

and equipment.17

16. Experts attested the important educational value of the omitted

facilities: Shop (App. 109, 173); Science (App. 54-55, 74-75; R.

[ 2 6 ]

B. Curricula18

Courses o f Study: Until the 1949-50 school session,

Washington-Lee provided three separate curricula: (1)

the academic, (2) the commercial, and (3) the general,

and awarded separate diplomas for completion of each

(App. 120-122; R. 45, 147-148, 856). In addition, it

actually had a vocational curriculum (App. 121-122).

Hoffman-Boston has never actually offered anything

other than the general curriculum. (App. 120-122;

R. 45, 147, 148).19

Washington-Lee has abandoned the practice of award

ing separate diplomas for completion of the different

curricula (R. 147, 856), but the courses comprising

368-369); Library (App. 118, 178-180); Music (App. 191, 192-193;

R. 423); Art (App. 103, 191); Commercial (App. 113, 193; R. 997);

Auditorium (App. 189); Gymnasium, Athletic, Physical Education (App.

101, 144, 153-154, 156, 189); Cafeteria (App. 114-115); Distributive

Education (App. 38-39, 115-116); Guidance (App. 116-117, 193); In

firmary (App. 190, 201-202); Teachers’ Restrooms (App. 119); Ad

ministrative (App. 184). See also the Jenkins Report, R. 33-76.

17. Experts testified that the following facilities at Hoffman-Boston

were individually inferior to those at Washington-Lee: Shops (App. 67-

68, 74, 108-109; R. 318, 417); Library (App. 47-48, 104-106, 110,

147, 178, 180, 185; R. 233-234); Science (App. 107, 191; R. 307);

Distributive Education (App. 39, 115); Guidance (App. 193); Art

(App. 27, 100, 103, 191); Music (App. 50, 100, 102, 191); Cafeteria

(App. 99-100, 192); Infirmary (App. 190); Business Office (App. 33;

R. 225); Teachers’ Restroom (App. 57, 192; R. 946-947); Auditorium

(App. 31, 100, 189); Gymnasium (App. 46, 101-102, 190); Com

mercial (App. 99, 108; R. 995); Physical Education (App. 99-100; R.

488, 505, 509); Athletic (App. 249); Buildings and Sites (App. 188-

189). See also the conclusions expressed in the Jenkins Report, R.

33-76.

18. It is regarded as superior practice for a high school to provide

a number of different curricular patterns in order to meet the individual

needs of pupils of varying abilities and interests (App. 122-123, 163-

166; R. 45, 493, 524).

19. A number of the required subjects in the academic, commercial

and vocational curricula were not and are not taught (App. 120-122,

333-334, 337-339; R. 45). The general curriculum has the least number of

required courses, is the easiest to complete, normally does not permit

the pupil to enter a standard college without conditions, and does not

provide proficiency in any vocation (R. 45-47).

[ 2 7 ]

each of its several curricula are still actually taught

each year (App. 333-334, 337-339). The courses offered

at Hoffman-Boston comprise nothing more than a gen

eral curriculum (App. 120-122, 333-334, 337-339; R. 45).

There are at least 37 courses separately offered and

taught at Washington-Lee which are neither offered

nor taught at Hoffman-Boston, as follows (App. 123-

124, 127, 213, 235-237, 264,

R. 738).

Speech I

Speech II

Journalism I

Journalism II

Adv. General Mathematics

Solid Geometry

Commercial Arithmetic

Economics

Psychology

World History

Economic Geography

Latin-American History

Latin I

Latin II

Fine Arts

Commercial Art

Music Appreciation

Orchestra

Mixed Chorus

276-277, 333-334, 337-339;

Commercial Law

Business Correspondence

Bookkeeping

Machine Shop

Sheet Metal

Automobile Mechanics

Printing

Mechanical Drawing

Retail Sales

Consumer Buying

Driver Training

Woodworking

Glee Club, Boys

Glee Club, Girls

Junior Girls’ Glee Club

Cadets, Boys

Cadets, Girls

Cadet Band

These are courses commonly taught in American

high schools, the important educational value of which

was attested by expert testimony in this case.20 *

20. Speech (App. 166-167); Journalism (App. 166-167, 259); Solid

Geometry (App. 167); Commercial Arithmetic (App. 167-168); Gen

eral Mathematics (App. 168-169); Economics (App. 169-170); World

[ 2 8 ]

The only “course” offered at Hoffman-Boston and not

available at Washington-Lee is a partial unit in brick

laying taught in connection with the general shop course

at the former school (R. 47).

—Alternation o f Courses: At Washington-Lee, the

courses are taught each and every year (App. 337-339).

Such courses as Hoffman-Boston affords are offered

pursuant to a regular practice of alternating the courses

over a period of three years, that is, the alternating

courses are taught only once each three years (App. 337-

339).

A curriculum offering courses to the pupils each year

is superior to one which offers only alternating courses

(App. 74), and the practice of alternation is generally

considered undesirable and contrary to best practices

(App. 138-139, 186-187). Therefore, difficulties arising

from alternation of courses21 exist at Hoffman-Boston,

to the decided disadvantage of its pupils,22 which do

not exist at Washington-Lee (App. 138-139).

—Grouping of Classes: In standard practice at

Washington-Lee, the senior high school courses are pro-

History (App. 169-170); Latin, Business Correspondence, Bookkeeping

(App. 170); Mechanical Drawing, Fine Arts, Art Appreciation (App.

171); Music Appreciation, Mixed Chorus, Boys’ Glee Club, Girls’ Glee

Club (App. 172); Machine Shop, Sheet Metal, Automobile Mechan

ics, Printing, Woodworking (App. 173); Retail Sales, Consumer

Buying (App. 173-174); Boys’ Cadets, Girls’ Cadets, Cadet Band, Or

chestra (App. 174); Driver Training (App. 62-63, 174-175); Guidance

(App. 117).

21. The difficulties encountered by Peggy Council (ante, pp. 8-9)

are typical.

22. The chief disadvantages, among others, of such a system are

(1 ) it prevents the organization of courses on a sequential basis; (2 )

prevents homogenius grouping of pupils by age, grade and maturation

levels; (3 ) seriously handicaps maladjusted, transferring or failing stu

dents who frequently are unable to get the courses when needed, and

(4 ) requires a greater extension of teaching faculty, in the way of addi

tional preparation and decreased specialization and thoroughness of the

teacher (App. 136-139, 186-188).

[ 2 9 ]

gressively organized into half units of content (App.

337-339; R. 47).

Such has not been the practice at Hoffman-Boston.

There, all pupils in grades 9B, 10A, 10B, 11A, 11 B, 12A

and 12B were taught throughout in the same classes dur

ing the 1947-48 session, all pupils in these 7 half-

grades taking exactly the same schedule and being taught

the same content (R. 49), Under this arrangement,

progression of the subject matter of the courses of

study could not be accomplished, and the students

were permitted no electives (R. 49). During the cur

rent school session, the courses in English, Civics, Phy

sics and Typewriting are taught to all pupils in grades

11B, 12A and 12B in the same room, by the same teach

er, at the same time (App. 214-215, 217-218, 238-239),

and Physical Education is being taught to all pupils

in grades 10B, 11A, 11B, 12A and 12B in the same room

by the same teacher at the same time (App. 214-215).

Vocational Courses: The vocational courses at Wash

ington-Lee afford both general and vocational shop-

work23 (App. 265-266; R. 966). Hoffman-Boston offers

only general shopwork (App. 265; R. 968, 970-971,

1007). The single shop at Hoffman-Boston could not

afford an adequate program (App. 233), and it is un

known whether the single shop instructor there could

give or has been trained to teach all of the vocational

courses there offered at Washington-Lee ( R. 1071-1072).

23. Vocational shopwork at Washington-Lee is a technical voca

tional course in which the pupil spends one-half of his day in the vo

cational course, and the other half of his day in taking his related or

required subjects (App. 265; R. 741, 967-969). This is intended to

train the pupil for specific types of occupations (App. 265-266). Gen

eral shopwork affords only a beginners’ or background course only en

abling the acquisition of skills for development in the specialized vo

cational courses (App. 265-266; R. 967-969).

[ 3 0 ]

Summer Schools A summer session has obvious value

in affording pupils the opportunity to take additional

courses, retake courses failed, or strengthen themselves

in weak subjects (App. 175-177; R. 49-50). Wash

ington-Lee regularly provides an 8-week summer school

for its pupils (R. 49-50, 156), and its 1948-49 session

offered English and Mathematics at all levels and 9

courses in other fields (App. 336). Hoffman-Roston

has no summer school (App. 336).

Guidance: There are two trained guidance counsel

lors at Washington-Lee (R. 735). Hoffman-Boston

has no guidance counsellor (App. 116-117, 230; R.

735). Guidance has an important value to the edu

cation of the pupil, and can at all times be afforded

by a specialist than a teacher (App. 40-41, 116-118,

145-146, 200).

Co-Curricular Activities: The curriculum at Washing

ton-Lee includes a vast number of club and pupil ac

tivities24 which are absent from the curriculum at Hoff

man-Boston, as follows: (App. 128-129, 176-178; R.

52, 155):

* Boys’ Glee Club Bible Club

0 Girls’ Glee Club Football

* Mixed Chorus Basketball

* Junior Girls’ Glee Club Baseball

' Orchestra Track

*Band Crew

a Boys’ Cadet Corps Golf

* Girls’ Cadet Corps Tennis

24. The educational value of a well-rounded program of co-curricular

activities is important and well-recognized (App. 128-129, 176-178;

R. 51). All of the so-called “extra-curricular” activities are actually a

part of the pupil’s total educational experience (App. 128).

[ 3 1 ]

Student Newspaper Staff Archery

Year Book Staff

Hi-Y Organizations

Tri-Y Organizations

Literary Society

Debating Club

Various subject Clubs

The 8 activities marked with an asterisk are in fact

curricular subjects in the schedule which carry credit

(App. 129; R. 155). None of the club or pupil activi

ties available at Hoffman-Boston carries credit (App.

129). The listing above does not denote the indi

vidual subject clubs at Washington-Lee, which would

make the list considerably longer (App. 129).

Honorary Awards: Washington-Lee has a chapter of

the National Honor Society (App. 134-135; R. 70), a

national organization having chapters in the leading high

schools in the United States (App. 133-134; R. 70).

Membership in this organization is one of the most

coveted student awards, and only first-class high schools

are eligible for chapters25 (App. 133-134; R. 70). Wash

ington-Lee may also confer the Bausch and Lomb Hon

orary Science Award (App. 134; R. 70).

Hoffman-Boston does not have a chapter of the Na

tional Honor Society, nor may it confer the Bausch

and Lomb Honorary Science Award (App. 134; R.

70). The fact that its pupils cannot compete for these

honors is a decided disadvantage to them26 * (App.

134).

25. In this connection, Washington-Lee holds the following citation:

“By virtue of its standards, this school is qualified to confer this award

for scholastic attainment.” (R. 70).

26. It has long been a custom in American high schools to give

special recognition to students of scholastic excellence (R. 70). The

undisputed evidence was that honorary awards build the morale and

prestige of pupils, provide homogeneity among the pupils obtaining

them, and are of valuable assistance to them in obtaining acceptance

by. colleges, scholarships, and employment (App. 133-134, 194-195).

[ 3 2 ]

C. Teachers

Number of teachers: Washington-Lee has 79 full-time

senior high school teachers (R. 107, 108, 110, 114),

including an ample number of vocational teachers.

Hoffman-Boston has only 12 full-time teachers, who

teach in both the junior and the senior high school de

partments (App. 239), only one of whom teaches vo

cational work (App. 91). The number of teachers at

Hoffman-Boston is insufficient to permit the teaching

of the number or variety of courses taught at Wash

ington-Lee27 (App. 89-92).

Teaching Experience: The experience of the teacher

is an objective index to teaching competency (R. 39)28 *

In general, experienced teachers are better and more

effective teachers than inexperienced teachers (App.

92-93, 148, 160-161; R. 39).

Teachers at Washington-Lee have a greater average

of teaching experience, both in Arlington County and

elsewhere, than teachers at Hoffman-Boston (App. 148,

160-161; R. 110, 409, 677). The median Washington-

Lee teacher had 11 years of total teaching experi

ence in 1947-48 (R. 40, 41) and 12.8 years in 1948-

49 (R. 110). The median Hoffman-Boston teacher

had only 6 years of total teaching experience in 1947-

48 (R. 40, 41) and only 5.6 years in 1948-49 (R. 110).

27. For example, the single vocational instructor at Hoffman-Boston

could not teach, certainly as well, all of the distinct vocational courses

as well as they are taught by the several vocational teachers at Wash

ington-Lee each of whom is a specialist in his field. (App. 89-92).

The same considerations apply in the academic field, particularly in the

language and science courses (App. 91-92).

28. Arlington, like most other school systems, gives salary and other

preferences to teachers as their teaching experience increases (R. 39-

40).

[ 3 3 ]

Washington-Lee has 28 teachers with more than 15

years total teaching experience, while Hoffman-Boston

has none (R. 110).

Teachers Salaries: Differences in competency of teach

ers are further reflected in the salaries paid teachers

in the two schools.29 The median salaries paid Wash

ington-Lee teachers for 1946-47, 1947-48, and 1948-

49, were $2,861, $3,149, and $3,242, respectively (R.

42, 105). The median salaries paid Hoffman-Boston

teachers for the same years were $2,274, $2,724, and

$2,699, respectively ( R. 42, 105). In these three years,

only one teacher, for only 1947-48, at Hoffman-Boston

received a salary which was greater than the median

salary of teachers at Washington-Lee ( R. 40, 42, 105).

As all teachers are paid from the same salary scale

(App. 98-99; R. 40, 675), these differentials are due

to factors of competency rather than race (App. 99;

R. 40, 499).

Number o f Different Subjects Taught: Teachers at

Hoffman-Boston have to teach a number of different

unrelated subjects, while teachers at Washington-Lee

are almost in fields of specialization30 (App. 94-97,

29. Salaries of teachers in Arlington County are based upon factors

of experience, collegiate training and rating, reputation and scholastic

ability (R. 675-676). The basic assumption of the salary schedule is

that as training and experience increase, the teacher’s value to the

pupil increases (R. 40).

30. A teacher is seldom equally competent in all of the subjects he

is certificated to teach (R. 40-41). In terms of both training and in

terest, the teacher is usually most competent in his field of major specializa

tion (R. 43). The general practice in larger schools is to confine a

teacher to teaching primarily subjects in his major field, and, secondarily,

in his minor field, of college preparation (App. 163-164; R. 593, 594,

597). Instruction in a school in which each teacher teaches a single

subject will usually be superior to instruction in a school in which teachers

generally teach two or more unrelated subjects (App. 163-164; R.

43, 593-599).

162-163). Only 2 of the 79 teachers at Washington-

Lee in 1946-47 and only 3 of the 81 teachers there

in 1947-48, taught more than a single subject (R. 43),

and no teacher taught more than 2 unrelated subjects

during this period (R. 43). All 5 of the teachers

at Hoffman-Boston in 1946-47, and 6 of the 7 teachers

there in 1947-48 taught two or more unrelated sub

jects (R. 43). In 1948-49, only 6 of the 79 teachers

at Washington-Lee had to make more than three daily

preparations, while during the same year 9 of the 11

teachers at Hoffman-Boston had to make more than

three daily preparations (App. 95; R. 114).

D. Accreditation

Washington-Lee is accredited both by the South

ern Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools and

by the Virginia State Department of Education (App.

131, 268; R. 68). Until 1948-49, Hoffman-Boston was

accredited by neither (App. 131, 268). It is still not

accredited by the Southern.Association (App. 132, 268;

R. 937) and is accredited by the Virginia State Depart

ment of Education only on a probationary basis (App.

131, 268).31

[ 3 4 ]

31, Accreditation is a thing of great value, not only to the school,

bat also to its pupils (App. 131; R. 68). The standards of regional

accrediting agencies are usually higher than those of state accrediting

agencies (App. 147-148; R. 497). A public institution of higher learning

in Virginia might admit without qualification graduates of a school ac

credited by the state accrediting agency (App. 132). Graduates of a

school accredited by a regional accrediting agency may normally go

to any institution, public or private, in the United States and enter with

out examination, but if the school is not accredited by a regional ac

crediting agency, a majority of the colleges in the United States either

will not admit the graduate or will admit them only by special ex

amination (App. 130-131). Thus, non-accreditation by the Southern

Association would adversely effect the entrance by a Hoffman-Boston

graduate into most colleges in the United States (App. 132) and its

pupils who desire to enter college, either private or public, located outr

side Virginia are greatly disadvantaged (App. 130-132; R. 69-70).

Experts testified as to the inherent difficulties and

inferiorities of small as compared with large high schools

(App. 71-72, 75; Pi. Ex. 99). The conclusion reached

by them (App. 68, 99, 135-136, 195) that the opportuni

ties, advantages and facilities afforded Hoffman-Boston

pupils are greatly inferior to those afforded Washing

ton-Lee pupils, is inescapable.

■ Ill

The Discriminations Against Appellants Cannot Be

Justified B y Reason'of the Smaller Number of

Negro H igh School Pupils, as Compared with

the Number of W hite H igh School Pupils,

in Arlington County, or B y the Compara

tive E xpenditures or Investments Made

for E ducation in the H igh Schools

of Said County.

The position of appellees and the Court below rests

largely upon the fact that the enrollment at Hoffman-

Boston is much smaller than at Washington-Lee. The

simple answer is that the constitutional right to equali

ty in educational opportunities is personal, and that

the fact of smaller number of pupils at Hoffman-Boston

is no justification for a refusal to afford such right when

requested,32 or for the difficulties arising from its small

ness. This is educationally (App. 73, 74-75, 142-144,

195-196, 198-200, 225-226), as well as legally, sound.

The expenditures and investments per capita (App.

347-348) in the high schools in question are equally ir

relevant. Conclusions as to the relative merits of two

[ 3 5 ]

32. Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337 (1938), cited supra

note 5; McCabe v. Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway Co ., 235 U. S.

151 (1914); Mitchell v. United States, 313 U. S. 80 (1941).

[ 3 6 ]

schools drawn from per capita expenditures and in

vestments is acceptable procedure where the schools

are of comparable size, but it is well known that where,

as here, there is greatly disparity in the size of the

populations of the schools being compared, per cap

ita figures are worthless (App, 86-89).

IV

The Discriminations Against Appellants as to

Courses of Instruction Cannot B e Justified

B y the Claimed F ailure of Negro Pupils

to Specifically Demand the E stablish

ment of Such Courses at the Negro

H igh School.

At Washington-Lee, all courses in the curriculum are

available each year to every eligible pupil without prev

ious demand or request therefor (App. 224, 225, 228).

Appellees’ claim, and the holding of the Court below,

is that a Negro pupil at Hoffman-Boston seeking in

struction there in courses available to pupils at Wash

ington-Lee as a matter of course must be subjected

to an entirely different procedure:

1. He must make a precedent demand or request

for the course before it will he afforded, either at

Hoffman-Boston or elsewhere, and await its establish

ment, even though the same course is already being

taught at Washington-Lee (App. 224, 228-229; R.

712).

2. Upon receipt of a demand or request for a course

at Hoffman-Boston for instruction in which it has no

facilities or where it is requested only by a few pupils,

the principal has no authority to establish the course,

[ 3 7 ]

but can only refer the request to the School Board

for such arrangements it is able to make (App. 705-

706, 237-238; R. 784, 790, 802, 811-812). The course

will not be given unless and until the School Board so

directs (R. 811-812).

3. In addition, the pupil must survive an investi

gation or test before a determination is made (App.

230, 269-270).33

That it is not incumbent upon Negro pupils to seek

the establishment of additional educational facilities was

recently made clear in the Sipuel case34 where a Negro

refused admission to the only state-supported law school

in Oklahoma because of her race sought mandamus

to compel her admission. The courts of that state

denied the writ on the ground that she should have

requested the establishment of a separate law school.

The Supreme Court of the United States held this po

sition to be untenable.35 * *

33. The Vice-Chairman of the Board testified that if only one Negro

pupil wanted at Hoffman-Boston a course taught at Washington-Lee,

the Board would not be justified in establishing it unless the pupil

was “tested”, and it appeared that it would do the pupil some good,

the pupil showed enough talent and aptitude for the course and ability

to use it, and “there was any practical reason why tax money should