Opposition to Motion to Affirm

Public Court Documents

July 3, 1978

12 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bolden v. Mobile Hardbacks and Appendices. Opposition to Motion to Affirm, 1978. d70f76d2-cdcd-ef11-8ee9-6045bddb7cb0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1ddaea48-9e30-4644-8730-8f466e0c2c59/opposition-to-motion-to-affirm. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

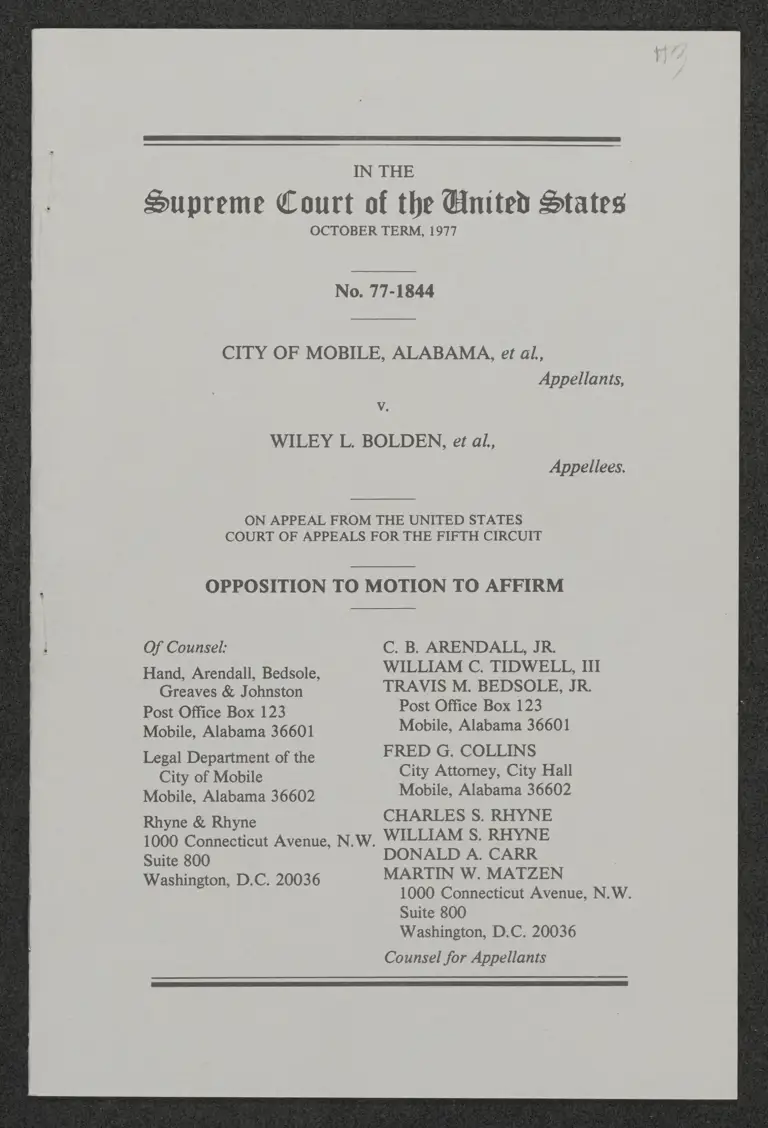

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1977

No. 77-1844

CITY OF MOBILE, ALABAMA, et al,

Appellants,

V.

WILEY L. BOLDEN, et al,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

OPPOSITION TO MOTION TO AFFIRM

Of Counsel: C. B. ARENDALL, JR.

Hand, Arendall, Bedsole, WILLIAM C. TIDWELL, III

Greaves & Johnston TRAVIS M. BEDSOLE, JR.

Post Office Box 123 Post Office Box 123

Mobile, Alabama 36601 Mobile, Alabama 36601

Legal Department of the FRED G. COLLINS

City of Mobile City Attorney, City Hall

Mobile, Alabama 36602 Mobile, Alabama 36602

1000 Connecticut Avenue, N.W. WILLIAM S. RHYNE

Suite 800 DONALD A. CARR

Washington, D.C. 20036 MARTIN W. MATZEN

1000 Connecticut Avenue, N.W.

Suite 800

Washington, D.C. 20036

Counsel for Appellants

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1977

No. 77-1844

CITY OF MOBILE, ALABAMA, et al,

Appellants,

WILEY L. BOLDEN, et al,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

OPPOSITION TO MOTION TO AFFIRM

As Appellants’ Jurisdictional Statement points out, this

case is the first to come before this Court in which an entire

form of local government, not merely the manner of its

election, has been struck down by the Federal Courts under

the constitutional rubric of “dilution” of black votes. Itis also

the first case to require this Court to decide whether

“relevant constitutional distinctions may be drawn in this

[dilution] area between a state legislature and a municipal

government.” Wise v. Lipscomb, U.S. , 46

U.S.L.W. 4777, 4780 (June 22, 1978) (separate opinion).

This aspect of Lipscomb was not addressed in Appellees’

2

Motion to Affirm (August 3, 1978). This Court cannot

dispose of this case properly without evaluating the distinc-

tion between state governments and local governments,

adumbrated in Lipscomb.

The dilution rule made applicable to state legislative

elections by White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755, should not be

carelessly transplanted into the local government context.

There are a host of salient differences and reasons militating

more greatly in favor of municipal at-large electoral systems,

several of which are highlighted in this litigation.

The essence of a state legislature is the representation of

geographically narrow constituencies in the formulation of

broad, statewide policy. See United Jewish Organizations

of Williamsburgh, Inc. v. Carey, 430 U.S. 144, 166. The

generality of the policy declaration, and the absence of a

need for implementation by the legislature, make the state

legislature perfectly adapted to continual reapportionment

and coalition politics. Intervention by Federal Courts to

rearrange the constituencies of the individual members of the

legislative collective, when the Constitution requires, causes

no undue dislocation in the duties or operation of the

legislative institution.

This is not always the case, however, with the local

governments which implement the broad statewide policy. It

is especially not the case where the Federal Court’s remedy

changes not only constituency but the very form of the local

government, as does the remedy in this case.

Fundamentally, the central purpose served by at-large

elections is more important to local governing boards than to

state legislatures. Thus, it has been observed:

“[ T]he purposes served by multimember districts are

less apparent in Regester than in Zimmer.* The

In Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297 (5th Cir. 1973) (en banc),

aff'd sub. nom. East Carroll Parish School Board v. Marshall, 424

(continued)

3

districtwide perspective and allegiance which result

from representatives being elected at-large, and which

enhance their ability to deal with districtwide problems,

would seem more useful in a public body with

responsibility only for the district than in a statewide

legislature.” Note, 87 Harv. L. Rev. 1851, 1857

(1974).

It is consistent with this analysis that use of multimember

districts in state legislative apportionment has long been on

the decline.? Silva, Compared Values Of The Single- And

The Multi-Member Legislative District, 17 West. Polit. Q.

504-505 (1964); Dixon & Hatheway, The Seminal Issue In

State Constitutional Revision: Reapportionment Method

And Standards, 10 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 888, 903 (1969).

With respect to city government, exactly the opposite is true.

The proportion of cities using at-large elections has grown

markedly since the turn of the century and from 53 percent in

1940 to 62 percent in the middle 1960’s to more than 67

percent in 1972. Jewell, Local Systems of Representation:

(footnote continued from preceding page)

U.S. 636, the Fifth Circuit extrapolated from Regester and extended the

dilution rule to local governments. This Court affirmed “without

approval of the constitutional views” enunciated by the Fifth Circuit.

424 U.S. at 638. :

The autonomy of most local governments being limited by State law,

councils and commissions often must seek approval of their decisions in

the State legislatures. The City of Mobile, for example, does not have

home rule under Alabama law. The District Court below took notice of

the local legislation procedures employed in the Alabama legislature,

which consists of a 35 single-member districted Senate and a 105 single-

member districted House.

Thus, in a real sense, policy for the City of Mobile is made by a

combination of the best of both patterns: single-member districts for the

supervisory State legislature, and commission form, necessarily at-large,

for the city government.

In this way, the distinctions perceived in. Lipscomb, supra, can

coexist.

4

Political Consequences And Judicial Choices, 36 Geo.

Wash. L. Rev. 790, 799 (1968); International City Man-

agement Association, Municipal Year Book Table 3/15

(1972).

Much of the impetus of this trend is undoubtedly provided

by adoptions of the two reform models of local government:

the commission form and its successor, council-manager.

Aside from the shared premise of at-large elections, the

common ground of these two forms is non-partisan elections?

— another extremely important distinction from the state

legislative circumstance confronting the Court in Regester.

Where parties determine who may run for office, there is a

potential for the exclusion of minority-supported candidates

from the ballot which cancels out or minimizes minority

voting strength.

That potential for exclusion is removed where elections

are truly non-partisan and where no other white-dominated

interest groups control the slating process. While there are

some only nominally non-partisan cities where candidates

are nevertheless supported by political parties or by various

influential groups, it is most common for a “free for all”

pattern to prevail, in which neither parties nor slates of

candidates are important. C. Adrian & C. Press, Governing

Urban America 99-100 (4th Ed. 1972); R. Lineberry & L

Sharkansky, Urban Politics and Public Policy 88 (1971).

In Mobile, parties play no role, and there is but one

important slating organization — a black group which

endorsed each of the winners in the last contested city

elections. (J.S. 10-12). In such a situation, it is an absolute

’The great majority (76 per cent) of city governments in the country are

non-partisan. Only the mayor-council form, decreed by the District

Court below, shows a substantial percentage (36 per cent) of partisan

electoral systems. International City Management Association,

Municipal Year Book 69 (1976).

5

imperative that, as Appellees concede, all “candidates

actively seek black votes as well as white votes. . .”” (Motion

to Affirm at 6).

Political scientists concur that the most outstanding

feature of the commission form is the dual role of the

commissioners — each of them serves individually as the

head of an executive department while collectively they

serve as the policy-making council for the city. In other

words, unlike the various mayor-council structures and

unlike any state governmental scheme, there is no separation

of powers.

The theory, and in Mobile, the practice? of this is that the

real implementer of policy is directly and immediately

accessible to citizens with input or complaints about the

performance of city government. There are no intermediate

steps. The legislator is not compelled to do extensive

casework to locate and persuade the responsible ad-

ministrator of the value of his constituent’s message.

Whereas in a state legislature single-member districts may

be necessary to make constituencies small enough so that all

the casework can be done, the very structure of Mobile’s

government is designed to address that need.

The council-manager form is based on an almost anti-

thetical idea of complete insulation of the manager from

electoral politics. Appellants do not argue that one or the

other is best for all times and all communities, only that each

serves important policy considerations and has charac-

teristics quite distinct from the state legislative scenario.

Both reform models depend on at-large elections, which

“The testimony of Plaintiffs’ own witnesses established that one or

more Commissioners were personally available to hear black citizens’

needs and grievances, and that this access had tangible impact on city

government performance. (Tr. 433-34, 572-73, 583, 621-25).

6

under the law of this case (a rule purportedly derived from the

principles set down in Regester) are unconstitutional in any

city where racially polarized voting is found from an abstruse

statistical demonstation and blacks are not numerous enough

to elect blacks to office.

Probable jurisdiction should be noted.

Respectfully submitted,

C. B. ARENDALL, JR.

WILLIAM C. TIDWELL, III

TRAVIS M. BEDSOLE, JR.

Post Office Box 123

Mobile, Alabama 36601

FRED G. COLLINS

City Attorney

City Hall

Mobile, Alabama 36602

CHARLES S. RHYNE

WILLIAM S. RHYNE

Of Connsel DONALD A. CARR

MARTIN W. MATZEN

Hand, Arendall, Bedsole, 1000 Connecticut Avenue, N.W.

Greaves & Johnston Suite 800

Post Office Box 123 Washington, D.C. 20036

Mobile, Alabama 36601

Legal Department of the

City of Mobile

Mobile, Alabama 36602

Counsel for Appellants

Rhyne & Rhyne

1000 Connecticut Avenue, N. W.

Suite 800

Washington, D. C. 20036