United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education Opinion (Corrected Copy)

Public Court Documents

December 29, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education Opinion (Corrected Copy), 1966. f8961f88-c79a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1dee2d1a-1d69-453c-9bcf-ca3018741fa6/united-states-v-jefferson-county-board-of-education-opinion-corrected-copy. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

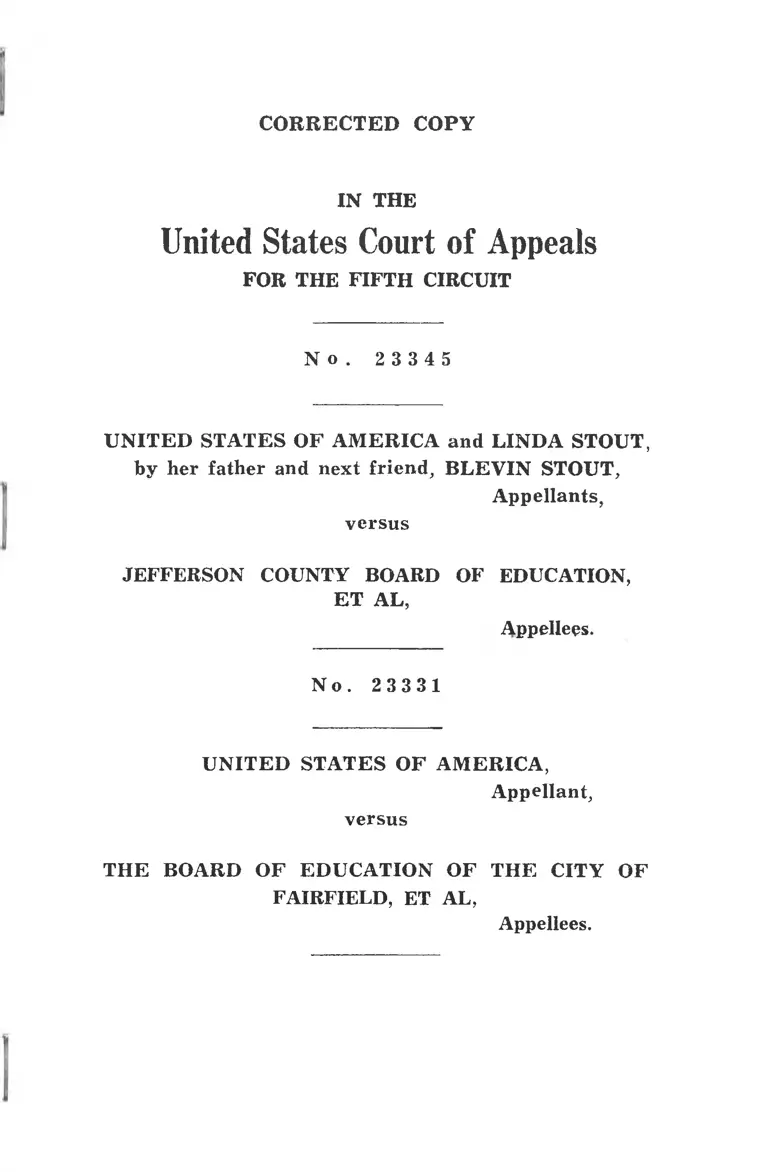

CORRECTED COPY

IN THE

United States Court of Appeals

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

N o . 2 3 3 4 5

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA and LINDA STOUT,

by her father and next friend, BLEVIN STOUT,

Appellants,

versus

JEFFERSON COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION,

ET AL,

Appellees.

N o . 2 3 3 3 1

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Appellant,

versus

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE CITY OF

FAIRFIELD, ET AL,

Appellees.

2 U. S., et al. v. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al.

N o . 2 3 3 3 5

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Appellant,

versus

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE CITY OF

BESSEMER, ET AL,

Appellees.

Appeals from the United States District Court for the

Northern District of Alabama.

N o . 2 3 2 7 4

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Appellant^

versus

CADDO PARISH SCHOOL BOARD, ET AL,

Appellees.

N o . 2 3 3 6 5

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Appellant,

versus

THE BOSSIER PARISH SCHOOL BOARD, ET AL,

Appellees.

17. S., et al . V. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al.

N o . 2 3 1 7 3

MARGARET M. JOHNSON, ET AL,

Appellants,

versus

JACKSON PARISH SCHOOL BOARD, ET AL,

Appellees,

N o . 2 3 19 2

YVORNIA DECAROL BANKS, ET AL,

Appellants,

versus

CLAIBORNE PARISH SCHOOL BOARD, ET AL,

Appellees.

Appeals from the United States Distriet Court for the

Western Distriet of Louisiana.

(D ecem ber 29, 1966.)

Before WISDOM and THORNBERRY, C ircuit Judges,

and COX,* D istric t Judge.

WISDOM, C ircuit Judge: Once again the Court is

called upon to review school desegregation plans to

determ ine w hether the plans m eet constitutional

s tandards. The distinctive fea tu re of these cases, con

solidated on appeal, is that they requ ire us to reex

am ine school desegregation standards in the light of

* William Harold Cox, U. S. District Judge for the Southern Dis

trict of Mississippi, sitting by designation.

4 U. S., et al. v. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al.

the Civil R ights A ct of 1964 and the G uidelines of the

U nited States Office of E ducation , D epartm en t of

H ealth , Education, and W elfare (HEW ).

W hen the U nited S tates Suprem e Court in 1954

decided Brown v. Board of Education^ the m em

bers of the H igh School C lass of 1966 had not en tered

the firs t g rade. Brown I held th a t sep a ra te schools

for N egro children w ere “ inheren tly unequal” .̂ N e

gro children, sa id the Court, have the “ personal and

p re sen t” righ t to equal educational opportunities

w ith white children in a rac ia lly nondiscrim inatory

public school system . F o r all but a handful of Negro

m em bers of the High School Class of ’66 th is righ t

has been “ of such stuff as d ream s a re m ade on” ,!*

“ The Brown case is m isread and m isapp lied when

it is construed sim ply to confer upon N egro pupils

the rig h t to be considered for adm ission to a white

̂ Brown v. Board of Education, 1954, 347 U. S. 483, 74 S.Ct.

686, 98 L. Ed. 873 {Brown I). See Brown v. Board of Education,

1955, 349 U.S. 294, 75 S.Ct. 293, 99 L.Ed.'1083 {Brown II).

2 347 U. S. at 495.

3 Shakespeare, The Temptest IV, The cases consolidated for ap

peal involve Alabama and Louisiana public schools. In Alabama,

as of December 1965, there were 1250 Negro pupils, out of a state

wide total of 295,848, actually enrolled in schools with 559,123

white students,, 0.43% of the eligible Negro enrollment. In Louisi

ana there were 2187 Negro children, out of a total of 318,651, en

rolled in school with 483,941 white children, 0.69% of the total

eligible. Southern Education Reporting Service, Statistical Sum

mary of Segregation-Desegregation in the Southern and Border

Area from 1954 to the present, 15th Rev. p. 2, Dec. 1965. See Ap

pendix B, Rate of Change and Status of Desegregation. In each of

the seven cases before this Court, no start was made toward de

segregation of the schools until 1965, eleven years after Brown.

In all these cases, the start was a consequence of a court order

obtained only after vigorous opposition by school officials.

U. S ; et al. V. Jejf. County Bd. of Educ., et al.

school” .̂ The U nited S ta tes Constitution, as construed

in Brown, req u ires public school system s to in teg ra te

students, faculties, facilities, and activities.® If Brown

* Braxton v. Board of Public Instruction of Duval County,

S.D.Fla. 1962, 7 Race Rel. L. Rep. 675, aff’d, 5 Cir.

1964, 326 F.2d 616, cert, den’d 377 U. S. 924 (1964).

Senator Humphrey cited this case in explaining Section 604 of

The Civil Rights Act of 1964. See Section IV D of this opinion.

" The mystique that has developed over the supposed difference

between “desegregation” and “integration” originated in Briggs

V . Elliott, E.D.S.C. 1955, 132 F.Supp. 776: “The Constitution . . .

does not require integration. It merely forbids segregation”. 132

F.Supp. at 777. This dictum is a product of the narrow view

that Fourteenth Amendment rights are only individual rights;

that therefore Negro school children individually must exhaust

their administrative remedies and will not be allowed to bring class

action suits to desegregate a school system. See Section IIIA of

this opinion.

The Supreme Court did not use either “desegrega

tion” or “integration” in Brown. But the Court did

quote with approval a statement of the district court

in which “integrated” was used as we use it here. For ten

years after Brown the Court carefully refrained from using “in

tegration” or “integrated”. Then in 1964 in Griffin v. County

School Board of Prince Edward County, 375 U.S. 391, 84 S.Ct.

400, 11 L.Ed.2d 409, the Court noted that “the Board of Super

visors decided not to levy taxes or appropriate funds for integrated

public schools”, i.e. schools under a desegregation order. There

is not one Supreme Court decision which can be fairly construed

to show that the Court distinguished “desegregation” from “in

tegration”, in terms or by even the most gossamer implication.

Counsel for the Alabama defendants assert that “desegrega

tion” and “integration” are terms of art. They struggle valiantly

to define these words:

By “desegregation” we mean the duty imposed by Brown

upon schools which previously compelled segregation to take

affirmative steps to eliminate such compulsory segregation

so as to allow the admission of students to schools on a non-

racial admission basis. By “integration” we mean the actual

placing of or attendance by Negro students in schools with

whites.

They can do so only by narrowing the definitions to the point of

inadequacy. Manifestly, the duty to desegregate schools extends

beyond the mere “admission” of Negro students on a non-racial

basis. As for “integration”, manifestly a desegregation plan must

include some arrangement for the attendance of Negroes in

formerly white schools.

In this opinion we use the words “integration” and “desegre

gation” interchangeably. That is the way they are used in the

vernacular. That is the way they are defined in Webster’s Third

New International Dictionary: “ ‘integrate’ to ‘desegregate’ ”.

6 17. S., et al. v. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al.

I left any doubt as to the a ffirm ative dutj? ̂ of s ta tes

to fu rn ish a fully in teg ra ted education to N egroes as

The Civil Rights Commission follows this usage; for example,

“The Office of Education . . . standards . . . should . . .

ensure that free choice plans are adequate to disestablish dual,

racially segregated school systems . . . to achieve substantial

integration in such systems.” U. S. Comm. Survey of School

Desegregation 1965-66, p. 54.

The Eighth Circuit used “integration” interchangeably with

“desegregation” in Smith v. Board of Education of Morrilton, 8

Cir. 1966, 365 F.2d 7J0. So did the Third Circuit in Evans v.

Ennis, 3 Cir. 1960, 281 F.2d 385. See also Brown v. County

School Board of Frederick County, Va., W.D.Va. 1965, 245 F.

Supp. 549. The courts in Dowell v. School Board of Oklahoma City

Public Schools, W.D.Okla. 1965, 244 F. Supp. 971 and Dove v.

Parham, 8 Cir. 1960, 282 F.2d 256 (and the Civil Rights Commis

sion), speak of a school board’s duty to “disestablish segrega

tion”. This term accurately “implies that existing racial imbalance

is a consequence of past segregation policies, and, because of

this, school boards have an affirmative duty to remedy racial

imbalance”. Note, Discrimination in. the Hiring and Assignment of

Teachers in Public School Systems, 64 Mich. L. Rev. 692, 698 n.44

(1966). (Emphasis added.)

We use the terms “integration” and “desegregation” of

formerly segregated public schools to mean the conversion of a

de jure segregated dual system to a unitary, nonracial (nondis-

criminatory) system—lock, stock, and barrel: students, faculty,

staff, facilities, programs, and activities. The proper govern

mental objective of the conversion is to offer educational op

portunities on equal terms to all.

As we see it, the law imposes an absolute duty to desegre

gate, that is, disestablish segregation. And an absolute duty to

integrate, in the sense that a disproportionate concentration of

Negroes in certain schools cannot be ignored; racial mixing of

students is a high priority educational goal. The law does not

require a maximum of racial mixing' or striking a racial balance

accurately reflecting the racial composition of the community

or the school population. It does not require that each and evep^

child shall attend a racially balanced school. This, we take it,

is the sense in which the Civil Rights Commission used the

phrase “substantial-integration”. i.. j

As long as school boards understand the objective of de

segregation and the necessity for complete disestablishment of

segregation by converting the dual system to a nonracial unitary

svstem, the nomenclature is unimportant. The criterion for deter

mining the validity of a provision in a desegregation plan_ is

whether it is reasonably related to the objective. We emphasize,

therefore the governmental objective and the specifics of the

conversion process, rather than the imagery evoked by the

pejorative “integration”. Decision-making in this important area

of the law cannot be made to .turn upon a quibble devised over

U. S., et al. V. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al. 7

a class, Brown II reso lved th a t doubt. A s ta te w ith a

dual a ttendance system , one for w hites and one for

N egroes, m ust “ effectuate a transition to a [single]

rac ia lly nondiscrim inatory sy stem .” ® The two Brown

decisions estab lished equalization of educational op

portunities as a h igh p rio rity goal for all of the s ta tes

and com pelled seven teen s ta tes , w hich by law had

segregated public schools, to take affirm ative action

to reorganize their schools into a un itary , nonracial

system .

The only school desegregation plan that m eets con

stitutional standards is one that works. By helping

public schools to m eet th a t test, by assisting the

courts in the ir independent evaluation of school de

segregation plans, and by acce lerating the p rogress

bu t sim plifying the process of desegregation the.

HEW G uidelines offer new hope to N egro school

children long denied the ir constitu tional rights. A

national effort, bringing together Congress, the

executive, and the jud ic ia ry m ay be able to m ake

m eaningful the rig h t of Negro ch ildren to equal

educational opportunities. The courts acting alone

have failed.

We hold, again , in determ ining w hether school de

segregation plans m eet the standards of Brown and

ten years ago by a court that misread Brown, misapplied the class

action doctrine in the school desegregation cases, and did not fore

see the development of the law of equal opportunities.

® Brown v. Board of Education, 1955, 349 U.S. 294, 301.

8 U. S., et al. v. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al.

other decisions of the Suprem e C o u r t , th a t courts in

th is c ircu it should give “ g rea t w eight” to HEW

Guidelines.® Such deference is consistent w ith the

exercise of trad itio n a l jud ic ia l pow ers and functions.

HEW G uidelines a re based on decisions cf th is and

o ther courts, a re fo rm u la ted to s tay w ithin the scope

of the Civil R ights Act of 1964, a re p rep a red in detail

by experts in education and school adm in istra tion ,

and a re in tended by Congress and the executive to

be p a r t of a coordinated national p ro g ram . The

G uidelines p resen t the best system availab le for uni

fo rm application, and the East aid to the courts in

evaluating the valid ity of a school desegregation plan

and the progress m ade under th a t plan.

HEW regulations provide th a t schools applying for

financial assistance m ust com ply w jfh ce rta in re

qu irem ents. However, the req u irem en ts for elem en

ta ry or secondary schools “ shall be deem ed to be

satisfied if such school or school sy stem is sub jec t to

a final o rder of a court of the U nited S ta tes for the

desegregation of such school or school system . .

This regu la tion causes our decisions to have a tw o

fold im p ac t on school desegregation . Our decisions

determ ine not only (1) the s tandards schools m ust

com ply w ith under Brown but also (2) the s tan d ard s

these schools m ust com ply w ith to qualify for fed era l

financial assistance. Schools automatically qual-

’’ Especially Cooper v. Aaron, 1958, 358 U.S. 1, 78 S.Ct. 1399,

3 LEd.2d 3; Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond,

1965, 382 U.S. 103, 86 S.Ct. 224, 15 L.Ed.2d 187; Rogers v. Paul,

1965, 382 U.S. 198, 86 S.Ct. 358, 15 L.Ed.2d 265.

8 Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School District, 5

Cir. 1965, 348 F.2d 729 (Singleton /) .

9 45 C.P.R. 180.4(c) (1964).

17, S., et al. V. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al. 9

ify for fed e ra l aid w henever a final court o rd er

desegregating the school has been en tered in the liti

gation and the school au thorities ag ree to com ply

w ith the order. Because of the second consequence of

our decisions and because of our duty to cooperate

w ith Congress and w ith the executive in enforcing

Congressional objectives, strong policy considerations

support our holding th a t the s tandards of court-

superv ised desegregation should not be lower than

the s tandards of H EW -supervised desegregation . The

Guidelines, of course, cannot bind the courts; we a re

not abdicating any jud ic ia l responsib ilities.“ But we

hold th a t H EW ’s s tan d ard s a re substan tia lly the sam e

as th is C ourt’s s tandards. They a re req u ired by the

Constitution and, as we construe them , a re w ithin

the scope of the Civil R ights A ct of 1964. In evaluating

desegregation plans, d is tric t courts should m ake

few exceptions to the Guidelines and should c a re

fully ta ilo r those so as not to defeat the policies of

HEW or the holding of th is Court.

Case by case over the last tw elve years, courts

have increased the ir understand ing of the desegre

gation p rocess.“ Less and less have courts accepted

the question-begging distinction betw een “ deseg rega

tion” and “ in teg ra tio n ” as a san c tu ary for school

boards fleeing from th e ir constitutional duty to estab-

In Singleton I, to avoid any such inference, we said: “The

judiciary has of course functions and duties distinct from those

of the executive department . . . Absent legal questions, the

United States Office of Education is better qualified. . . . ” 348

F. 2d at 731.

“The rule has become: the later the start, the shorter the

time allowed for transition.” Lockett v. Board of Education of

Muscogee County, 5 Cir. 1965, 342 F.2d 225, 228.

10 U. S., et al. V. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al.

lish an in teg ra ted , non-racial school system d^ W ith

the benefit of th is experience, the Court has re

studied the School Segregation Cases. We have re

exam ined the n a tu re of the N egro’s rig h t to equal

educational opportunities and the ex tent of the cor

re la tive affirm ative duty of the s ta te to fu rn ish equal

educational opportunities. We have taken a close look

at the background and objectives of the Civil R ights

A ct of 1964.18

^ ^ jJ?

We approach decision-m aking here w ith hum ility.

M any in telligent m en of good will who have dedicated

th e ir lives to public education a re deeply concerned

for fear th a t a doctrinaire approach to desegregat

ing schools m ay lower educational standards or even

destroy public schools in som e a reas . These educa

to rs and school adm in istra to rs, especially in com m u

nities where to tal segregation has been the w ay of

life from crad le to coffin, m ay fail to understand all

of th,3 legal im plications of Brown, but they un

d erstand the g rim rea lities of the problem s th a t com

plicate th e ir task.

The Court is aw are of the g rav ity of th e ir problem s.

(1) Some determ ined opponents of desegregation

would scuttle public education ra th e r th an send th e ir

children to schools w ith N egro children. These m en

■- See Section III A and footnote 5.

The Court asked counsel in these consolidated cases and in

five other cases for briefs on the following questions:

(a) To what extent, consistent with judicial preroga

tives and obligations,- statutory and constitutional, is it per

missible and desirable for a federal court (trial or appellate)

to give weight to or to rely on H.E.W. guidelines and policies

in cases before the court?

(b) If permissible and desirable, what practical_ means

and methods do you suggest that federal courts (trial and

appellate) should follow in making H.E.W. guidelines and

policies judicially effective?

17. S., et al. V. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al. 11

flee to the suburbs, reinforcing u rb an neighborhood

school p a tte rn s. (2) P riv a te schools, a ided by s ta te

g ran ts , have m ushroom ed in som e s ta tes in th is c ir

c u i t . T h e flight of w hite children to these new

Schools and to estab lished p riv a te and paroch ial

schools prom otes resegregation . (3) M any white

teach ers p re fe r not to teach in Negro schools. They

a re tem p ted to seek em ploym ent a t white schools or

to re tire . (4) M any Negro children, for various re a

sons, p re fe r to finish school w here they s ta rted . (5)

The gap betw een white and Negro scholastic achieve

m ents causes all so rts of difficulties. There is no con

solation in the fac t th a t the gap depends on the socio

econom ic sta tu s of N egroes a t leas t as m uch as it de

pends on in ferio r N egro schools.

No court can have a confident solution for a legal

problem so closely interw oven w ith political, social,

and m o ra l th read s as the problem of establishing

fair, w orkable s tandards for undoing de ju re school

segregation in the South. The Civil R ights Act of

1964 and the HEW Guidelines a re belated but invalu

able helps in arriv ing a t a neutral, principled deci

le Alabama provides tuition grants of $185 a year and Louisiana

$360 a year to students attending private schools. “Only Florida

and- Texas report no obvious cases of private schools formed to

avoid desegregation in public schools.” Up to the school year

1965-66, Louisiana had “some 11,000 pupils already receiving

state, tuition grants to attend private schools.” This number will

be significantly increased as a result of new private schools in

Plaquemines Parish. Leeson, Private Schools Continue to In

crease in the South, Southern Education Report, November 1966,

p. 23. In Louisiana, students attending parochial schools do not

receive tuition grants.

12 U. S., et al. v. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al.

Sion consisten t w ith the dim ensions of the problem ,

trad itiona l jud ic ia l functions, and the U nited S tates

Constitution. We g rasp the nettle.

I.

“ No arm y is s tronger th an an idea whose tim e

h as com e.” ®̂ Ten y ears a fte r Brown, cam e the Civil

R ights Act of 1964.“ C ongress decided th a t the tim e

had com e for a sweeping civil righ ts advance, in

cluding national legislation to speed up d eseg rega

tion of public schools and to put tee th into enforce

m en t of desegregation .” T itles IV and VI together

In a press meeting May 19, 1964, to discuss the Civil Rights

bill. Senator Everett Dirksen so paraphrased, “On resiste a

I’invasion des armees; on ne resiste pas a I’invasion des idees.”

Victor Hugo, Histoire d’un crime: Conclusion: La Chute, Ch. 10

(1877). Senator Dirksen then said, “Let editors rave at will and

let states fulminate at will, but the time has come, and it can’t

be stopped.” Cong. Quarterly Service, Revolution in Civil Rights

63 (1965).

i« H. R. 7152, Pub. L. 88-352, 78 Stat. 243; approved July 2,

1964.

“[I]n the last decade it has become increasingly clear that

progress has been too slow and that national legislation is re

quired to meet a national need which becomes ever more obvious.

That need is evidenced, on the one hand, by a growing impatience

by the victims of discrimination with its continuance and, on the

other hand, by a growing recognition on the part of all of our

people of the incompatibility of such discrimination with our

ideals and the principles to which this country is dedicated. A

number of provisions of the Constitution of the United States

clearly supply the means ‘to secure these rights,’ and H. R. 7152,

as amended, resting upon this authority, is designed as a step

toward eradicating significant areas of discrimination on a na

tionwide basis. It is general in application and national in scope.”

House Judiciary Committee Report No. 914, to Accompany H. R.

7152. 2 U.S. Code Congressional and Administrative News,

88th Cong. 2nd Sess. 1964, 2933. “The transition from all-

Negro to integrated schools is at best a difficult problem of ad

justment for teachers and students alike. . . . We have tried to

point out that the progress in school desegregation so well com

menced in the period 1954-57 has been grinding to a halt. The

trend observed in 1957-59 toward desegregation by court order

U. S., et al. V. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al. 13

constitu te the congressional a lte rn ativ e to court-su

perv ised desegregation . These sections of the law

mobilize in aid of desegregation the U nited States

Office of Education and the Nation’s purse.

A. Title IV authorizes the Office of E ducation to

give techn ical and financial assis tance to local school

system s in the process of desegregation.^® Title VI

requ ires all fed era l agencies adm in istering any grant-

in-aid p ro g ram to see to it that there is no rac ia l dis

crim ination by any school or other recipient of fed

eral financial aid.^® School boards cannot, however,

hy giving up fed era l aid, avoid the policy th a t p ro

duced this limitation on federal aid to schools: Title

IV authorizes the A ttorney G eneral to sue, in the

nam e of the U nited S tates, to desegregate a public

rathrr than hy voluntary action has continued. It is not healthy

nor right in this country to require the local residents of a com

munity to carry the sole burden and face alone the hazards of

commencing costly litigation to compel school desegregation. After

all, it is the responsibility of the Federal Government to protect

constitutional rights. . . . ” Additional Views on H. R. 7152 of

Hon. William M. McCulloch, Hon. John'V. Lindsay, Hon. William

T. Cahill, Hon. Garner E. Shriver, Hon. Clark MacGregor, Hon.

Charles McC. Mathias, Hon. James E. Bromwell.” Ibid., 2487.

18 78 Stat. 246-99, 42 U.S.C. § 2000c (1964).

19 78 Stat. 252-53, 42 U.S.C. § 2000d (1964). Section 601

states: “No person in the United States shall, on the ground of

race, color, or national origin, be excluded from participation in,

be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under

any program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”

Section 602 states: “Each Federal department and agency which

is empowered to extend Federal financial assistance to any program

or activity . . . is authorized and directed to effectuate the pro

visions of Section 601 with respect to such program or activity

by issuing rules, regulations, or orders of general applicability

which shall be consistent with achievement of the objectives of

the statute authorizing the financial assistance in connection

with which the action is taken. . . . ”

14 U. S., et al. v. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al.

school or school system.^® More clearly and effec

tively th an e ither of the o ther two coordinate b ranches

of G overnm ent, Congress speaks as the Voice of the

N ation. The national policy is plain: form erly de jure

segregated public school system s based on dual at

tendance zones m ust shift to unitary, nonracial sys

tem s—with or without federal funds.

The Chief Executive acted prom ptly to c a rry into

effect the Chief L eg isla tu re’s m andate. P res id en t

Lyndon B. Johnson signed the bill into law Ju ly 2,

19'64, only a few hours a fte r C ongress had finally

approved it. In the signing cerem ony b ro ad cas t to the

N ation, the P resid en t said : “ We believe all m en are

en titled to the blessings of liberty , yet m illions are

being deprived of those blessings—not because of

the ir own fa ilu res, but because of the color of the ir

skins. . . . [It] cannot c o n t i n u e . A t the request

of P res id en t Johnson, Vice P resid en t H ubert H. H um

phrey subm itted .a rep o rt to the P resid en t “ On the

Coordination of Civil R ights A ctivities in the F ed e ra l

G overnm ent” recom m ending the creation of a Coun

cil on E qual O pportunity. The rep o rt concludes that

“ the very b read th of the F ed era l G overnm ent’s ef

fort, involving a m ultip licity of p ro g ram s” necessary

to c a rry out the 1964 Act had c rea ted a “ problem

of coordination .” The P resid en t approved the recom

m endation th a t instead of creating a new agency

20 78 Stat. 246-49, 42 U.S.C. § 2000c (1964). In addition, Title

IX authorizes the Attorney General to intervene in private suits

where persons have alleged denial of equal protection of the laws

under the 14th Amendment where he certifies that the case is of

“general public importance.” 78 Stat. 266, Title IX § 902, 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000 h-2 (1964).

21 N.Y. Times, July 3, 1964, p. 1.

17. S., et al. V. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al. 15

there be a general coordination of e f f o r t . L a t e r ,

the P resid en t noted th a t the federal d ep artm en ts and

agencies had “ adopted uniform and consistent reg u la

tions im plem enting Title VI . . . [in] a coordinated

p ro g ram of en fo rcem ent.” He d irected the A ttorney

G eneral to “ coord inate” the various federal p ro

g ram s in the adoption of “ consistent and uniform

policies, p rac tices and procedures w ith respect to the

enforcem ent of Title VI. . .

In A pril 1965 Congress for the firs t tim e in its h is

tory adopted a law providing general federal aid

—a billion dollars a y ea r—for elem entary and

secondary schools.-^ It is a fa ir assum ption th a t

Congress would not have tak en th is step had Title VI

not estab lished the principle th a t schools receiving

fed era l assis tance m ust m eet uniform national

s tan d ard s for desegregation.^®

To m ake Title VI effective, the D epartm en t of

Health, E ducation , and W elfare (HEW) adopted the

regulation, “ N on-discrim ination in F edera lly assisted

P ro g ra m s.” *® This regulation d irects the C om m is

sioner of Education to approve applications for fi-

Executive Order 11197, Feb. 9, 1965, 30 F.R. 1721.

Executive Order No. 11247, Sept. 28, 1965, 30 F. R. 12327.

The Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, 79

Stat. 27.

23 “The Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965

greatly increased the amount of federal money available for public

schools, and did so in accordance with a formula that pumps the

lion’s share of the money to low-income areas such as the Deep

South. Consequently, Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

has become the main instrument for accelerating and completing

the desegregation of Southern public schools.” The New Republic,

April 9, 1966 (Professor Alexander M. Bickel).

2« 45 C.F.R. Part 80, Dec. 4, 1964, 64 F. R. 12539.

16 U. S., et al. v. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al.

nancia l assis tance to public schools only if the school

or school system agrees to com ply w ith a court o rder,

if any, outstanding against it, or subm its a deseg re

gation plan satisfacto ry to the Commissioner.^’̂

To m ake the regulation effective, by assisting the

Office of E ducation in determ ining w hether a "school

qualifies for fed era l financial aid and by inform ing

school boards of HEW requ irem en ts, HEW form u

lated certa in standards or guidelines. In A pril 1965,

nearly a y ear after the Act w as signed, HEW pub

lished its f irs t Guidelines, “ G eneral S ta tem en t of

Policies under Title VI of the Civil R ights Act of

1964 R especting D esegregation of E lem en ta ry and

Secondary Schools.” -® These Guidelines fixed the

fa ll of 1967 as the ta rg e t date for to ta l desegregation

of all g rades. In M arch 1966 HEW issued “Revised

Guidelines” to co rrec t m ost of the m a jo r flaw s re

vealed in the firs t y ea r of operation under Title VI.

B. The HEW G uidelines ra ise the question: To

w hat ex ten t should a court, in determ ining w hether

to approve a school desegregation plan, give w eight

to the HEW G uidelines? We adhere to the answ er

2'̂ “Every application for Federal financial assistance to carry

out a program to which this part applies . . . shall, as a condi

tion to its approval . . contain or be accompanied by an as

surance that the program will be conducted or the facility operated

in compliance with all requirements imposed by or pursuant to

this part. . . . ” 45 C.F.R. § 80.4 (a) (1964).

U. S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare, Office

of Education, General Statement of Policies under Title VI of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964 Respecting Desegregation of Elementary

and Secondary Schools, April, 1965. It is quoted in full in Price

V. Denison Independent School District, 5 Cir. 1965, 348 F.2d at

1010 .

29 Revised Statement of Policies for School Desegregation Plans

Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. March, 1966.

U. S., et al. V. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al. 17

this Court gave in four ea rlie r cases. The HEW

Guidelines a re “ m in im um s tan d a rd s” , representing

for the m ost p a r t s tan d ard s the Suprem e Court and

th is Court estab lished before the Guidelines were

promulgated.^^ Again we hold, “we attach g rea t

w eight” to the Guidelines. Singleton v. Jackson Munic

ipal Separate School District, 5' Cir. 1965, 348 F.2d

729 (Singleton I). “We put these s tan d ard s to work.

. . . [P lans] should be m odeled a fte r the Com

m issioner of E duca tion ’s requ irem en ts. . , . [E xcep

tions to the guidelines should be] confined to those

ra re cases p resen ting justic iab le, not operational,

questions. . . . The applicable s tan d a rd is essentially

the HEW fo rm u lae .” Price v. Denison Independent

School District, 5 Cir. 1965, 348 F .2d 1010. “We consid

e r it to be in the best in te rest of all concerned th a t

School B oards m eet the m inim um stan d ard s of the

Office of Education . . . . In certain school districts

and in certa in respects, HEW stan d ard s m ay be too

low to m eet the requ irem en ts estab lished by the

Suprem e Court and by this Court . . . . [But we also]

consider it im portan t to m ake c lear th a t . . . we do

not abd ica te our jud ic ia l responsibility for de term in

ing w hether a school desegregation p lan violates fed

era lly g u aran teed rig h ts .” Singleton v. Jackson Mu

nicipal Separate School District, 5 Cir. 1966, 355 F.2d

815 (Singleton II). In Davis v. Board of School Com

missioners of Mobile County, 5 Cir. 1966, 364 F.2d 896,

the m ost recen t school case before th is Court, we ap-

In Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile County,

5 Cir. 1966, 364 F.2d 896, Judge Tuttle, for the Court, noted that

“for more than a year, it has been apparent to all concerned

that the requirements of Singleton and Denison were the minimum

standards to apply.”

18 U. S., et al. v. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al.

proved Singleton I and II and Price v. Denison and

o rdered certa in changes in the school p lan in con

fo rm ity w ith the HEW G uidelines.

Courts in o ther c ircu its a re in substantial agree

m en t w ith this Court. In K em p v. Beasley, 8 Cir.

1965, 352 F . 2d 14, 18-19, the Court said : “ The Court

ag rees th a t these [HEW] s tan d ard s m ust be

'heavily relied upon . . . . [T]he courts should en

deavor to m odel th e ir s tan d ard s a fte r those prom ul-

g a ted by the executive. They a re not bound, how ever,

and w hen c ircum stances d icta te , the courts m ay re

quire som ething m ore, less or d ifferen t from the

H.E.W . guidelines.” (E m phasis added.) C oncurring,

Judge L arson observed: “However, th a t ‘som ething

d ifferen t’ should ra re ly , if ever be less th a n w hat is

contem plated by the H.E.W . s tan d a rd s .” 352 F .2d a t

23. Sm ith v. Board of Education of Morrilton, 8 Cir.

1966, 365 F.2d 770 rea ffirm s th a t the G uidelines “ a re

en titled to serious jud ic ia l deference” .

A lthough the Court of Appeals for the F o u rth C ir

cuit has not y e t considered the effect of the HEW

standards, d is tric t courts in th a t c ircu it have relied

on the guidelines. See Kier v. County School Board

of Augusta County, W .D.Va. 1966, 249 F. Supp. 239;

W right v. County School Board of Greenville County,

E.D .V a. 1966, 252 F. Supp. 378; Miller v. Clarendon

County School District No. 2, D.S.C., Civil Action No.

8752, A pril 21, 1966. In Miller, one of the m ost recen t

of these cases, the court said:

The orderly p rogress of desegregation is

best served if school system s desegregating

U. S., et al. V. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., e t.a l. 19

under court o rder are requ ired to m eet the

m inim um stan d ard s prom ulgated for system s

th a t desegregate voluntarily . W ithout d irec t

ing absolute adherence to the “ Revised S tand

a rd s” guidelines at this jun c tu re , th is court

will w elcom e their inclusion in any new,

am ended, or substitu te p lan which m ay be

adopted and subm itted .

In this circuit, the school problem arises from

state action. This Court has not had to deal w ith

nonracially m otivated de facto segregation, that is,

rac ia l im balance resulting fortuitously in a school

system based on a single neighborhood school se rv

ing all white and N egro children in a certa in a ttend

ance area or neighborhood. F o r this circu it, the

HEW G uidelines offer, for the firs t tim e, the p ros

pect th a t the transition from a de ju re seg regated

dual system to a u n ita ry in teg ra ted system m ay be

carried out effectively, prom ptly, and in an orderly

m anner. See A ppendix B, R ate of Change and S tatus

of Desegregation.

II.

We read Title VI as a congressional m andate for

change—change in pace and m ethod of enforcing de

segregation. The 1964 Act does not disavow court-

supervised desegregation. On the con trary , Congress

recognized th a t to the courts belongs the la s t word

in any case or c o n t r o v e r s y .B u t Congress w as dis-

31 Title IV, § 407, 42 U.S.C. § 2000 (c) authorizing the Attorney-

General to bring suit, on receipt of a written complaint, would

seem to imply this conclusion. Section 409 preserves the right of

individual citizens “to sue for or obtain relief” against discrimina

tion in public education. HEW Regulations prowde: “In any

case in which a final order of a court of the United States for

20 U. S., et al. v. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al.

satisfied w ith the slow prog ress inheren t in the jud i

cial adversary process.®^ Congress therefore fash

ioned a new m ethod of enforcem ent to be adm in

is te red not on a case by case basis as in the courts

but, generally , by fed era l agencies operating on a

na tional scale and having a special com petence in

th e ir respective fields. C ongress looked to these agen

cies to shoulder the additional enforcem ent burdens

resu lting from the shift to high g ear in school deseg

regation.

A. Congress was well aw are th a t it w as tim e for

a change. In the decade following Brown, court-super

v ised desegregation m ade qualita tive p rogress:

Responsible Southern leaders accep ted desegregation

as a settled constitu tional principle.®® Q uantitively,

the desegregation of such school or school system is entered

after submission of such a plan, such a plan shall be revised to

conform to such final order, including any future modification of

such order.” 45 C.F.R. § 80.4(c) (1964).

32 See footnote 17.

33 “The Federal courts have been responsible for great qualita

tive advances in civil rights; the lack has been in quantitative im

plementation—in enabling the individual to avail himself of these

great decisions.” Bernhard and Natalie, Between Rights and

Remedies, 53 Georgetown L. Jour. 915, 916 (1965). “[ l i t is the

consensus of the judges on the firing line, so to speak, that one

phase in the administration of the law—the establishment phase,

characterized by permissive tokenism, by a sort of minimal

judicial holding of the line while the political process did, as it

must, the main job of establishing—this phase has been closed

out.” Bickel, The Decade of School Desegregation, 64 Colum.

L. Rev. 193, 209 (1964). The changes of the past decade have dis

appointed the most optimistic hopes, but they have been dramat

ically sweeping nonetheless. Gellhorn, A Decade of Desegregation—

Retrospect and Prospect, 9 Utah L. Rev. 3 (1964). “What makes

one uneasy, of course is the truly awesome magnitude of what

has yet to be done.” Marshall, The Courts, in Center for the Study

of Democratic Institutions, The Maze of Modem Government 36

(1964), quoted in Poliak, Ten Years After the Decision, 24 Fed.

Bar Jour. 123 (1964). On the first decade of desegregation, see

generally, Sarratt, The Ordeal of Desegregation (1966); Legal

Aspects of the Civil Rights Movement (D. B. King ed. 1965).

17. S., et al. V. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al. 21

the resu lts w ere m eagre. The s ta tistics speak elo

quently. See Appendix B, R ate of Change and S tatus

of Desegregation. In 1965 the public school d is tric ts

in the consolidated cases now before this C ourt had

a school population of 155,782 school children, 59,361

of whom w ere Negro. Y et under the existing court-

approved desegregation plans, only 110 Negro chil

dren in these d istric ts , .019 p er cent of the school

population, a ttend fo rm er “ w hite” schools.®^ In 1965

there w as no faculty desegregation in any of these

school d is tric ts ; indeed, none of the 30,500 Negro

teachers in A labam a, Louisiana, and M ississippi

served w ith any of the 65,400 white teach ers in those

states.®® In the 1963-64 school year, the eleven s ta tes

of the C onfederacy had 1.17 per cent of th e ir N egro

students in schools w ith white students.®® In 1964-65,

undoubtedly because of the effect of the 1964 Act,

Total

Enrollment

Negroes Admitted

To Formerly

White Schools

Bessemer, Ala.

Fairfield, Ala.

Jefferson County, Ala.

Caddo Parish, La.

Bossier Parish, La.

Jackson Parish, La.

Claiborne Parish, La.

W N

2,920 5,284 13

1,779 2,159 31

45,000 18,000 24

30,680 24,467 1

11,100 4,400 31

2,548 1,609 5

X XX.X. 2,394 3,442 5

(Affidavit of St. John Barrett, Attorney, Department of Justice,

attached to Motion to Consolidate and Expedite Appeals.)

U. S. Dept, of Health, Education and Welfare, Office of

Education Release, Table 3, September 27, 1965. In the 11 states

of the Confederacy there are 1800 Negro teachers, 1.8 per cent

of all the Negro teachers in Southern schools, assigned to schopls

with biracial faculties. By contrast, in the border states (Dela

ware, Kentucky, Maryland, Missouri, Oklahoma and West Vir

ginia). 51 per cent of the Negro teachers now teach white students.

Xl3id36 Southern Education Reporting Service, Statistical Sunimary,

Dec. 1965, cited in U.S. Comm, on Civil Rights,

Desegregation in the Southern and Border States 1965-66, p. l.

22 U. S., et al. v. Jefj. County Bd. oj Educ., et al.

the percen tage doubled, reach ing 2.25. F o r the 1965-66

school y ear, this tim e because of HEW Guidelines,

the percen tage reached 6.01 per cent. In 1965-66 the

en tire region encom passing the Southern and border

states h ad 10.9 per cent of th e ir N egro children in

school w ith w hite ch ildren; 1,555 b irac ial school dis

tric ts out of 3,031 in the Southern and border states

w ere still fully seg regated ; 3,101,043 N egro children

in the region a ttended all-N egro schools. D espite the

im petus of the 1964 Act, the s ta tes of A labam a, Loui

siana, and M ississippi, still had less th an one p er cent

of th e ir N egro enro llm ent attend ing schools with

white students.®^

The dead hand of the old p ast and the closed f is t of

the recen t past account for som e of the slow prog

ress. There a re o ther reasons—as obvious to Con

gress as to courts. (1) Local loyalties com pelled

school officials and elected officials to m ake a public

record of the ir unw illingness to act. But even school

au thorities willing to ac t have m oved slowly be

cause of un certa in ty as to the scope of th e ir duty to

ac t affirm atively . This is a ttrib u tab le to (a) a m is

placed re liance on the Briggs d ictum th a t the Consti-

tuition “does not require integration”,®* (b) a misun

derstanding of the Brown II m andate , desegregate

with “due deliberate speed”,®* and (c) a mistaken no-

3̂ Ibid.; see footnote 3; Appendix B, Rate of Change and Status

of Desegregation.

38 See Section III A of this opinion.

39 In Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile County,

5 Cir. 1966, 364 F.2d 896, 898, Judge Tuttle, for the Court, said:

“This is the fourth appearance of this case before this court. This

present appeal, coming as it does from an order the trial

court entered nearly eighteen months ago, on March 31, 1965,

points up, among other things, the utter impracticability of a

U. S., et al. V. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al. 23

tion th a t tra n s fe rs under the P upil P lacem en t Law s

satisfy desegregation requirements.^® (2) Case by

case developm ent of the law is a poor sort of m edium

for reasonably p rom pt and uniform desegregation.

There a re n a tu ra l lim its to effective legal action.

Courts cannot give advisory opinions, and the d isci

plined exercise of the jud icia l function p roperly m akes

courts re lu c tan t to m ove fo rw ard in an a rea of the

continued exercise by the courts of the responsibility for super

vising the manner in which segregated school systems break out

of the policy of complete segregation into gradual steps of com

pliance and towards complete compliance with the constitutional

requirements of Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483. One

of the reasons for the impracticability of this method of oversee

ing the transitional stages of operations of the school boards

involved is that, under the Supreme Court’s ‘deliberate speed’

provisions, it has been the duty of the appellate courts to interpret

and reinterpret this language as time has grown apace, it now

being the twelfth school year since the Supreme Court’s decision.”

40 “The pupil assignment acts have been the principal obstacle

to desegregation in the South.” U. S. Comm, on Civil Rights,

Civil Rights U.S.A.—^Public Schools, Southern States 15, 1962.

See Note, The Federal Courts and Integration of Southern

Schools: Troubled Status of the Pupil Placement Acts, 62 Colum.

L. Rev. 1448, 1471-73 (1962); Bush v. Orleans Parish School

Board, 5 Cir. 1962, 308 F.2d 491. Such laws allow care

fully screened Negro children, on their application, to transfer

to white schools from the segregated schools to which the Negroes

were initially unconstitutionally assigned. Often, even after six

to eight years of no desegregation, these transfers were limited

to a grade a year. When this law first came before us we held

it to be unconstitutional. Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board,

E. D.La. 1956, 138 F. Supp. 337, af f d 242 F.2d 156, cert, den’d 354

U.S. 921 (1957). Later, in a narrowly focused opinion, we held

that the Alabama version was constitutional on its face. Shut-

tlesworth v. Birmingham Board of Education, N.D.Ala. 1958, 162

F. Supp. 372, aff’d per curiam, 358 .U.S. 101 (1958). As

long ago as 1959 and 1960 this Court disapproved of such acts as a

reasonable start toward full compliance. Gibson v. Board of

Public Instruction of Dade County, 272 F.2d 763; Mannings v.

Board of Public Instruction of Hillsborough County, 277 F.2d 370.

See also Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 5 Cir. 1961, 308

F.2d 491; Evers v. Jackson Municipal Separate School District, 5

Cir. 1964, 328 F.2d 408. *‘[T]he entire public knows that in fact

[the Louisiana law] . . . is being used to maintain segregation.

. . . It is not a plan for desegregation at all.” Bush v. Orleans

Parish School Board, 308 F. 2d at 499-500.

24 17. S., et al. v. Jeff, County Bd. of Educ., et al.

law bordering the p e rip h ery of the jud ic ia l domain.

(3) The con tem pt pow er is ill-suited to serve as the

chief m eans of enforcing desegregation . Judges nat

u ra lly shrink fro m using it ag a in s t citizens willing

to accep t the thank less, painful responsib ility of se rv

ing on a school board.'*^ (4) School desegregation

p lans a re often woefully inadequate ; they ra re ly p ro

vide n ecessa ry detailed instructions and specific an

swers to administrative problems.^^ And most judges

do not have sufficient com petence—they a re not

educato rs or school ad m in is tra to rs—to know the rig h t

questions, m uch less the rig h t answ ers. (5) B ut one

reason m ore th an any o ther has held back deseg re

gation of public schools on a large scale. This has

been the lack, until 1964, of effective congressional

Bush V. Orleans Parish School Board is an example.

The board was plagued by bundles of Louisiana statutes

aimed at defeating desegregation. There were five extra

sessions of the Louisiana legislature in 1960. After the School

Board had for three years failed to comply with an order to sub

mit a plan, the district judge wrote one himself. The trial judge

simply said: “All children [entering New Orleans public schools

. . . may attend either the formerly all white public schools

nearest their homes, or the formerly all Negro public schools

nearest their homes, at their option. B. Children may be trans

ferred from one school to another, provided such transfers are

not based on race”. 204 F.Supp. 568; 571-72.

For example, the order of the able district judge in Bush.

See footnote 41. Judge Bohanon underscored this point in

Dowell V. School Board of Oklahoma City Public Schools, W.D.Okla.

1965, 244 F. Supp. 971, 976: “The plan submitted to this Court

. . . is not a plan, but a statement of policy. School desegrega

tion is a difficult and complicated matter, and, a s . the record

shows, cannot be accomplished by a statement of policy. U De

segregation of public schools in a system as large as Oklahoma

City requires a definite and positive plan providing definable

and ascertainable goals to be achieved within a definite time

according to a prepared procedure and with responsibilities clearly

designated.”

U. S., et al. V. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al. 25

statu to ry recognition of school desegregation as the

law of the land.'^®

“Considerable p rog ress has been m ade . . . N ever

theless, in the la s t decade it has becom e increasingly

clear th a t p rogress has been too slow and that nation

al legislation is requ ired to m eet a national need

which becomes ever more obvious.” *̂ Title VI of the

Civil R ights Act of 1964, therefore, w as not only ap

propriate and proper legislation under the T hirteenth

and F ourteen th A m endm ents; it w as n ecessary to

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 had its direct genesis in Presi

dent Kennedy’s message to Congress of June 19, 1963, urging

passage of an omnibus civil rights law. He noted: “In the con

tinued absence of congressional action, too many state and local

officials as well as businessmen will remain unwilling to accord

these rights to all citizens. Some local courts and local mer

chants may well claim to be uncertain of the law, while those

merchants who do recognize the justice of the Negro’s request

(and I believe these constitute the great majority of merchants.

North and South)'will be fearful of being the first to move, in

the face of official customer, employee, or competitive pressures.

Negroes, consequently, can be expected to continue increasingly

to seek the vindication of these rights, through organized direct

action, with all its potentially explosive consequences, such as we

have seen in Birmingham, in Philadelphia, in Jackson, in Boston,

in Cambridge, Md., and in many other parts of the country. H In

short, the result of continued Federal legislative inaction will be

continued, if not increased, racial strife—causing the leadership

on both sides to pass from the hands of reasonable and responsible

men to the purveyors of hate and violence, endangering domestic

tranquillity, retarding our nation’s economic and social progress

and weakening the respect with which the rest of the world re

gards us. No American, I feel sure, would prefer this course of

tension, disorder, and division—and the great majority of our

citizens simply cannot accept it.’’ H.Doc. 124, 88th Cong. 1st

Sess. June 20, 1963, Rep. Emanuel Celler, Chairman of the House

Judiciary Committee, introduced H.R. 7152 embodying the Presi

dent’s proposals. The same day Senator Mike Mansfield intro

duced a similar bill, S. 1731. H.R. 7152-S.1731, as amended, be

came the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

H. Rep. No. 914, 88th Cong., 1st Sess.

26 U. S., et al. v. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., e t al.

rescue school desegregation from the bog in which

it had been trapped for ten years.*®

The Civil R ights Com m ission, doubtless be tte r able

th an any other au thority to un d ers tan d the signifi

cance of the Civil R ights Act of 1964, had th is to say

about Title VI:

“ This s ta tu te hera lded a new era in school

desegregation . . . M ost significantly . . .

F edera l pow er was to be b rought to b ear in

a m an n er w hich prom ised speed ier and m ore

su b stan tia l desegregation than had been

achieved through the vo lun tary efforts of

school boards and d istric t-by-d istric t litig a

tion. . . . D uring fiscal y e a r 1964, $176,546,992

w as d istribu ted to S tate and local school

agencies in the 17 Southern and border States.

The passage of the E lem en ta ry and Second

a ry E ducation A ct of 1965 added an addition

al appropria tion of $589,946,135 for allocation

to the 17 Southern and border S ta tes for fiscal

y e a r 1966. W ith funds of such m agnitude at

s take, m ost school system s would be placed

a t a serious d isadvan tage by te rm ina tion of

Federal assistance.”*®

“It was the Congressional purpose, in Title VI of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, to remove school desegregation efforts from

the courts, where they had been bogged down for more than a

decade. Unless the power of the Federal purse is more effectively

utilized, resistance to national policy will continue and, in fact,

will he reinforced.” Report of the White House Conference “To

Fulfill These Rights”, June 1-2, 1966, p. 63.

Rep. U. S. Comm, on Civil Rights, Survey of School De

segregation in the Southern and Border States—1965-66, p. 2.

U. S., et al. V. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., e t al. 27

B. The congressional m andate , as em bodied in

the Act and as ca rried out in the HEW G uidelines,

does not conflict w ith the p roper exercise of the jud i

cial function or w ith the doctrine of separation of

powers. It does how ever profoundly affect construc

tive use of the jud ic ia l function w ithin the lawful

scope of sound jud ic ia l discretion. W hen C ongress

declares national policy, the duty the two other coor

dinate branches owe to the N ation requ ires that,

within the law , the jud ic ia ry and the executive re

spect and c a rry out th a t policy. H ere the Chief E x

ecutive acted p rom ptly to bring about uniform s tan d

ards for desegregation . The jud icia l b ran ch too

should cooperate w ith Congress and the executive

in m aking adm in istra tive agencies effective in stru

m ents for supervising and enforcing desegregation

of public schools. Ju stice H arlan F. Stone expressed

this well;

“ L egisla tu res c rea te adm in istra tive agencies

w ith the desire and expectation th a t they will

perfo rm efficiently the tasks com m itted to

them . That, a t least, is one of the contem

p la ted social advan tages to be w eighed in

resolving doubtful construction. Its a im is so

obvious as to- m ake unavoidable the conclu

sion th a t the function w hich courts a re called

upon to perform , in carry ing into operation

such adm in istra tive schem es, is constructive,

not destructive, to m ake adm in istra tive agen

cies, w henever reasonab ly possible, effective

28 U. S., et al. v. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al.

in s trum en ts for law enforcem ent, and not to

destroy them .” ’̂'

In an analogous situation involving enforcem ent of

the F a ir Labor S tandards Act, the Suprem e Court

has said, “ Good adm in istra tion of the Act and good

jud icia l adm in is tra tio n alike requ ire th a t the stand

a rd s of public enforcem ent and those for d e term in

ing p riv a te righ ts shall be a t v a rian ce only w here

justified by very good reaso n s .” Skidm ore v. Swift

& Co., 1944, 323 U. S. 134, 65 S.Ct. 161, 89 L .E d. 124.

In an appeal from, the d is tric t co u rt’s denial of an

injunction to enforce labor s tan d ard s under the A ct

th is Court has pointed out:

“ . . . this proceeding is only superficially r e

la ted to a su it in equity for an injunction to

p ro tect in te rests jeopardized in a p rivate con

troversy . The public in te re s t is jeopardized

here. The in junctive p rocesses a re a m eans

of effecting general com pliance w ith national

Stone, The Common Law in the United States, 50 Harv. L.

Rev. 1, 18 (1936). In a similar vein, writing for the Court,

Justice Stone has said: “ . . . in construing a statute setting

up an administrative agency and providing for judicial review of

its action, court and agency are not to be regarded as wholly in

dependent and unrelated instrumentalities of justice, each acting

in the performance of its prescribed statutory duty without re

gard to the appropriate function of the other in securing the

plainly indicated objects of the statute. Court and agency are

the means adopted to attain the prescribed end, and so far as

their duties are defined by the words of the statute, those words

should be construed so as to attain that end through co-ordinated

action. Neither body should repeat in this day the mistake made

by the courts of law when equity was struggling for recognition

as an ameliorating system of justice; neither can rightly be re

garded by the other as an alien intruder, to be tolerated if must

be, but never to be encouraged or aided by the other in the at

tainment of the common aim.” United States v. Morgan, 1939,

307 U. S. 183, 191, 59 S. Ct. 795, 799, 83 L.Ed. 1211.

U. S., et al. V. Jejf. County Bd. of Educ., et al. 29

policy as expressed by Congress, a public

policy judges too m ust c a rry out—actu a ted by

the sp irit of the law and not begrudgingly as

if it w ere a newly im posed fia t of a p resid i

um . . . . Im plicit in the defendan ts’ non-com

pliance, as we read the briefs' and the record,

is a certa in underlying, not unna tu ra l, Acton-

ian d istaste for national legislation affecting

local activities. B ut the F a ir Labor S tandards

Law has been on the books for tw enty-three

years. The A ct estab lishes a policy for all of

the country, and for the courts as well as for

the agency requ ired to adm in ister the law.

M itchell V. Pidcock, 5 Cir. 1962, 299 F.2d 281,

287, 288.

C. We m ust therefore cooperate w ith Congress

and the Executive in enforcing Title VI. The problem

is: A re the HEW G uidelines w ithin the scope of

the congressional and executive policies em bodied

in the Civil R ights Act of 1964. We hold th a t they are.

The G uidelines do not p u rp o rt to be a ru le or reg u

lation or order. They constitute a s ta tem en t of policy

under section 80.4(c) of the HEW R egulations is

sued a fte r the P resid en t approved the regulations

D ecem ber 3, 1964. HEW is under no statu tory com

pulsion to issue such sta tem en ts . I t is, how ever, of

m anifest advan tage to school boards throughout the

country and to the general public to know the c rite ria

the C om m issioner uses in determ ining w hether a

30 17. S., et al. v. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al.

school m eets the req u irem en ts for eligibility to re

ceive financial assistance .

The G uidelines have the vices of all ad m in is tra

tive policies estab lished un ila te ra lly w ithout a h e a r

ing. B ecause of these vices the courts, as the school

boards point out, have set lim its on adm in istra tive

regulations, ru lings, policies, and p rac tices: an

agency construction of a s ta tu te cannot m ake the

law ; it m ust conform to the law and be reasonable.

To some extent the adm in istra tive w eight of the dec

la ra tions depends on the p lace of such declarations

in the h ie ra rch y of agency pronouncem ents extending

from regu lations down to general counsel m em o ran

da and inter-office decisions. See M anhattan General

Electric Company v. Commissioner, 1936, 297 U. S.

129, 56 S.Ct. 397, 80 L .Ed. 528; United States v. Ben

nett, 5 Cir. 1951, 186 F.2d 407; United States v. Mis

sissippi Chemical Corporation, 5 Cir. 1964, 326 F.

2d 569; Chattanooga Auto Club v. Commissioner, 6

Cir. 1950, 182 F.2d 551.

These and sim ila r decisions a re not inconsistent

w ith the co u rts’ giving g re a t w eight to the HEW ’s

policy s ta tem en ts on enforcem ent of Title VI. In

Skidmore v. Sw ift & Co., 323 U.S. 134, an action was

com m enced in a fed era l d is tric t court by em ployees

of Swift & Co. to recover w ages a t the overtim e ra te s

p rescrib ed by the F a ir Labor S tandards Act (52 Stat.

1060, et seq.) for certa in serv ices which they had

perform ed. At issue w as w hether these serv ices con

stitu ted “ em ploym ent” w ithin the m eaning of sec-

U. S., et al. V. Jefj. County Bd. of Educ., et al. 31

tion 7 (a) of th a t act. The d is tric t court and th is

Court, on appeal, decided th is issue ag a in st the

plaintiffs. The Suprem e Court reversed . A fter ac

knowledging (323 U.S. a t 137) th a t the s ta tu te had

g ran ted no ru le-m aking pow er to the W age and H our

A dm in istra to r w ith resp ec t to the issue a t hand

( “ [ijn stead , it put th is responsibility on the

courts”), the Court referred to an “Interpretative

B ulletin” issued by the A dm in istra to r containing his

in terp re ta tion of the s ta tu to ry ph rase in question. The

Suprem e Court said:

“ We consider th a t the rulings, in terp re ta tions

and opinions of the A dm in istra to r under th is

Act, while not controlling upon the courts by

reason of th e ir authority , do constitute a body

of experience and inform ed judgm en t to

w hich courts and litigan ts m ay properly re

so rt for guidance. The w eight of such a judg

m en t in a p a rtic u la r case will depend upon

the thoroughness evident in its consideration,

the valid ity of its reasoning, its consistency

w ith ea rlie r and la ter pronouncem ents, and

all those fac to rs which give it pow er to p e r

suade, if lacking power to control.” ®̂

The Supreme Court also stated in Skidmore, 323 U. S. at 139-

40: “The rulings of this Administrator are not reached as a re

sult of hearing adversary proceedings in which he finds facts

from evidence and reaches conclusions of law from findings of

fact. They are not, of course, conclusive, even in the cases with

which they directly deal, much less in those to which they apply

only by analogy. They do not constitute an interpretation of the

Act or a standard for judging factual situations which binds a

district court’s processes, as an authoritative pronoimcement of

a higher court might do. But the Administrator’s policies are

made in pursuance of official duty, based upon more specialized

32 U. S., et al. v. Jejf. County Bd. of Educ., et al.

The Suprem e Court found th a t the low er courts had

misunderstood their function vis-a-vis the In te rp reta

tive Bulletin and remanded the case. See also,

United States v. Am erican Trucking Association,

1940, 310 U. S. 543, 549; Goldberg v. Servas, 1 Cir.

1961, 294 F.2d 841, 847.

The national im portance of the HEW G uidelines,

the evident thoroughness w ith which these s tan d ard s

were p rep a red and fo rm ulated by educational au tho r

ities, the s im ila rity of the HEW stan d a rd s to the

s tandards th is Court and the Suprem e Court have

established, and the m anifest effort of the Office of

E ducation to be faithfu l to the congressional objec

tives of the 1964 Civil R ights Act entitle the HEW

G uidelines to g re a te r w eight by the courts th an run-

of-the-mine policy statem ents low in the h ie ra rchy

of adm in istra tive declarations.

Courts therefo re should cooperate v/ith the congres

sional-executive policy in favor of desegregation and

against aiding segregated schools.

D. B ecause our approval of a p lan establishes

eligibility for federal aid, our s tan d a rd s should not

be low er than those of HEW. Unless jud ic ia l stand-

experience and broader investigations and information than is

likely to come to a judge in a particular case. They do deter

mine the policy which will guide applications for enforcement by

injunction on behalf of the Government. Good administration of

the Act and good judicial administration alike require that the

standards of public enforcement and those for determining private

rights shall be at variance only where justified by very good

reasons.” (Emphasis added.)

17. S., et al. V. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al. 33

ards a re substantia lly in accord w ith the Guidelines,

school boards previously resistan t to desegregation

will re so rt to the courts to avoid com plying w ith the

m inim um stan d ard s HEW prom ulgates for schools

tha t desegregate voluntarily . As we said in Singleton

I:

“ If in som e d istric t courts jud ic ia l guides for

approval of a school desegregation p lan a re

m ore accep tab le to the com m unity or sub

stantially less burdensom e than H.E.W .

guides, school boards m ay tu rn to the federal

courts as a m eans of c ircum venting the

H.E.W . requ irem en ts for financial aid. In

stead of a uniform policy re la tive ly easy to

adm in ister, both the courts and the Office of

E ducation would have to struggle w ith indi

vidual school system s on ad hoc basis. If

judicial s tan d ard s a re low er, re ca lc itran t

school boards in effect will receive a p re

m ium for recalc itran ce; the m ore the in tran

sigence, the b igger the bonus.” 348 F.2d a t

731.

In Kem p v. Beasley, 8 Cir. 1965, 352 F.2d 14, the

Court concluded:

“ [HEW] s tan d ard s m ust be heavily relied

upon. . . . Therefore, to the end of p rom ot

ing a degree of uniform ity and discouraging

re lu c tan t school boards from reap ing a bene

fit from the ir re luctance the courts should

endeavor to m odel th e ir s tan d ard s a fte r those

34 U. S., et al. v. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al.

prom ulgated by the executive.’

19.

352 F.2d a t 18,

C oncurring, Judge Larson, speaking from his expe

rience as a d is tric t judge, pointed out th a t school

boards w hich do not a c t vo luntarily re ta rd the deseg

regation process to the d isadvan tage of the individ

ual’s constitu tional righ ts: “ Ju d ic ia l c rite ria ” ,

therefo re , “ should ‘p robably be m ore s trin g en t” than

HEW G uidelines:

“A school board which fails to a c t voluntarily

forces Negro students to solicit a id from the

courts. This not only shifts the burden of in i

tia tin g desegregation , but inevitab ly m eans

delay in tak ing the f irs t step. As Judge Gib

son observes, we a re not here concerned w ith

regu lating the flow of F ed e ra l funds. Our task

is to safeguard basic constitu tional rights.

Thus, our s tan d ard s should be directed to

w ard full, com plete, and final realization of

those r ig h ts .” 352 F.2d a t 23.

The announcem ent in HEW regulations tha t the

Com m issioner would accep t a final school desegrega

tion o rder as proof of the school’s eligibility for

fed era l aid p rom pted a num ber of schools to seek

refuge in the fed e ra l courts. M any of these had not

moved an inch toward desegregation.^® In Louisiana

The following statement appeared in the Shreveport 'Journal

for July 1, 1965: “The local school boards prefer a court order

over the voluntary plan because HEW regidations governing the

voluntary plans or compliance agreements demand complete

desegregation of the entire system, including students, faculty,

staff, lunch workers, bus drivers, and administrators, whereas

the court-ordered plans can be more or less negotiated with the

judge.” This was not news to the Court.

U. S., et al. V. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al. 35

alone tw enty school boards obtained quick decrees

providing for desegregation according to p lans g re a t

ly at variance with the Guidelines.®®

We shall not p e rm it the courts to be used to destroy

or dilute the effectiveness of the congressional policy

expressed in Title VI. There is no bonus for foot-

dragging.

E. The experience th is Court has had in the la st

ten y ears argues strongly for uniform stan d ard s in

court-supervised desegregation.

The firs t school case to reach this Court a fte r

Brown v. Board of Education was Brown v. Rippey,

5 Cir. 1956, 237 F.2d 796. Since then we have review ed

41 other school cases, many more than once.® ̂ The

We may also expect a number of school desegregation. suits

to be filed in Alabama. The legislature has enacted a statute de

claring the Guidelines null and void in Alabama and prohibiting

school officials signing any agreement to comply. The bill pro

vides that any agreement or assurance of compliance with the

guidelines already in effect “is null and void and shall have no

binding effect.” H.B. 446, approved September 2, 1966.

The brief of the United States gives the following figures:

“1. Case Load

Number of

Cases

Number of

Orders Entered

District

Court

128

513

Court of

Appeals

42

76

Supreme

Court

10

2. Frequency of Appeals

to this Court

Number of Cases With One or More Appeals 42

Number of Cases With Two or More Appeals 21

Number of Cases With Three or More Appeals 8

Number of Cases With Four or More Appeals 4

Number of Cases With Five or More Appeals 2

In Bush V. Orleans Parish School Board the complaint was

filed September 5, 1952. Bush’s peregrinations through the

courts are reported as follows: 138 F.Supp. 336 (3-

judge 1956) motion for leave to file petition for man

damus denied, 351 U. S. 948 (1956); 138 F. Supp. 337

36 U. S., et al. v. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ.j et al.

d is tric t courts in th is c ircu it have considered 128

school cases in the sam e period. R eview ing these

cases im poses a taxing, tim e-consum ing burden on

the courts not reflected in s ta tistics . An analysis of

the cases shows a wide lack of uniform ity in areas

w here th e re is no good reason for varia tio n s in the

schedule and m anner of desegregation.®^ In some

cases there has been a substan tia l tim e-lag betw een

th is C ourt’s opinions and the ir application by the dis

trict courts.®* In certain cases—which we consider un

necessary to cite—there has even been a m an ifest

v a riance betw een th is C ourt’s decision and a la te r

d is tric t court decision. A num ber of d is tric t courts

still m istaken ly assum e th a t tran sfe rs under Pupil

P lacem en t Laws—superim posed on unconstitu tional

in itia l assignm ent—satisfy the req u irem en ts of a de

segregation plan. The lack of c lear and uniform

s tan d a rd s to govern school boards has tended to put

a prem ium on delaying actions. In sum , the lack of

uniform standards has re ta rd ed the developnaent of

(1956) , aff’d 242 F.2d 156 (1957), cert, den’d, 354 U.S. 921

(1957) ; 252 F.2d 253, cert, den’d 356 U.S. 960 (1958); 163 F.

Supp. 701 (1958), aff’d, 268 F.2d 78 (1959); 187 F. Supp. 42 (3-

judge 1960), motion to stay den’d, 364 U.S. 803 (1960), aff’d

365 U.S. 569 (1961); 188 F. Supp. 916 (3-judge 1960), motion

for stay denied, 364 U.S. 500 (1960), aff’d, 365 U.S. 569 (1961);

190 F. Supp. 861 (3-judge 1960), aff’d 366 U.S. 212 (1961); 191

F. Supp. 871 (3-judge 1961), aff’d 367 U.S. 908 (1961); 194 F.

Supp. 182 (3-judge 1961), aff’d, 367 U.S. 907 (1961), 368 U.S. 11

(1961); 204 F. Supp. 568 (1962); 205 F. Supp. 893 (1962), aff’d

in part and rev’d in part, 308 F.2d 491 (1962); 230 F. Supp. 509

(1963).

5- Of the 99 court-approved freedom of choice plans .in this

circuit, 44 do not desegregate all grades by 1967; 78 fail to pro

vide specific, non-racial criteria for denying choices; 79 fail to

provide any start toward faculty desegregation; only 22 provide

for transfers to teke courses not otherwise available; only 4 in

clude the 8ingl§tcm transfer rule.

See footnote 39.

V. S., et al. V. J^ff. County Bd. of EdUc., et al. 37

local responsibility for the adrh in istre tion 6f Schools

w ithout reg a rd to race or color. W hat w as tru e of an

earlie r A thens and an ea rlie r Rom e is tru e today: In

Georgia, for exam ple, there should not be one law

for Athens and another law for Rom e.

Before HEW published its Guidelines, this Court

had a lread y estab lished guidelines for school deseg

regation: to encourage uniform ity at the d is tric t

court level and to conserve judicia l effort at both

the d is tric t court and appellate levels. We did so by

m aking detailed suggestions to the d is tric t courts.

Lockett V. Board of Education of Muscogee County,

5 Cir. 1964, 342 F.2d 225; Bivens v. Board of Educa

tion for Bihh County, 5 Cir. 1965, 242 F.2d 229; A rm

strong V. Board of Education of B irm ingham , 5 Cir.

1964, 333 F.2d 47; Davis v. Board of School Com mis

sioners of Mobile County, 5 Cir. 1964, 333 F.2d 53;

Stell V. Savannah-Chatham County Board of Educa

tion, 5 Cir. 1964, 333 F.2d 55; Gaines v. Dougherty

County Board of Education, 5 Cir. 1964, 334 F.2d 983.

In other a re a s of the law involving rec u rre n t p rob

lem s of regional or national in terest, th is Court

has also found guidelines advantageous. In United

States V. Ward, 5 Cir. 1965, 347 F.2d 795, and United

States V. Palm er, 5 Cir. 1966, 356 F.2d 951, suits to

enjoin re g is tra rs of voters fro m discrim inating

against N egroes, we a ttached identical proposed

decrees for the guidance of district courts.® ̂ See also

In Ward the Court said: “[Glood administration suggests

that the proposed decree be indicated by an Appendix, not be

cause of any apprehenmoh that the conscientious District Judge

would hot faithfully impose every condition so obviously im

plied, but rather because of factors bearing upon administration

38 U. S., et al. v. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al.