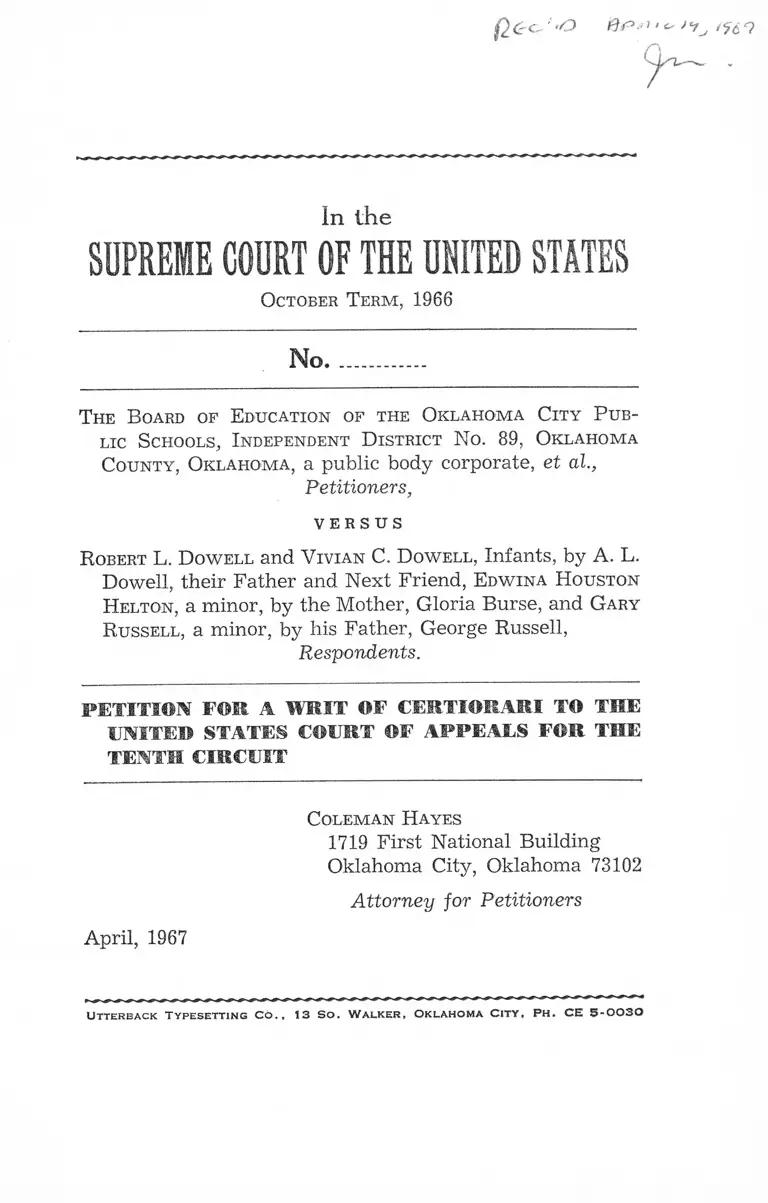

Oklahoma City Public Schools Board of Education v. Dowell Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit

Public Court Documents

April 1, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Oklahoma City Public Schools Board of Education v. Dowell Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit, 1967. ece14433-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1e03b0f6-244a-4eac-a79f-ac5b9e3bd5e5/oklahoma-city-public-schools-board-of-education-v-dowell-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-tenth-circuit. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

|2 < r< - ' -O • i- > ’t j ,y 6 9

In the

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term , 1966

No ........................

The Board of Education of the Oklahoma City P ub

lic Schools, Independent D istrict No. 89, Oklahoma

County, Oklahoma, a public body corporate, et al.,

Petitioners,

V E R S U S

R obert L. D owell and V ivian C. Dowell, Infants, by A. L.

Dowell, their Father and Next Friend, Edwina Houston

Helton, a minor, by the Mother, Gloria Burse, and Gary

Russell, a minor, by his Father, George Russell,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR A W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE

TENTH CIRCUIT

Coleman Hayes

1719 First National Building

Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 73102

Attorney for Petitioners

April, 1967

U t t e r b a c k T y p e s e t t in g C o . , t 3 S o . W a l k e r . O k l a h o m a C i t y . P h . C E 5 -O O S O

—ii—

INDEX

Citations to Opinions Below _______________________ 2

Jurisdiction ________________________________________ 2

Questions Presented__________________________ 2

Statutes and Constitutional Provision Involved -------- 3

Statement _________________________________________ 3

Reasons for Granting the Writ _____________________ 8

Conclusion _____________________________________— 15

APPENDIX

Appendix A:

Opinions of the United States Court of Appeals,

Tenth Circuit_________________________________ i-xxi

Appendix B:

Judgment and Orders Denying Petitions for Re

hearing __________________________ _________ xxii-xxiii

Appendix C:

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

xxiii-xxiv

AUTHORITIES CITED

Cases:

Bell v. School City of Gary, Indiana, 324 F.2d 209,

cert, denied 379 U.S. 924, 84 S.Ct. 1223, 12

L.Ed.2d 216 ____________________________________ 8, 9

INDEX CO N TI N UE D

Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F.Supp. 776 ------------------------- 9

Brown v. Board of Education (D.C.), 139 F.Supp.

468 ________________________________________3-9. 10, 11

Downs v. Board of Education of Kansas City, 336

F.2d 988, cert, denied 380 U.S. 914-------------------8, 9,12

Kelley v. Board of Education, 270 F.2d 209, cert,

denied 361 U.S. 924, 80 S.Ct. 293, 4 L.Ed.2d 240 8, 9

Walling v. Brown (C.A. 5), 132 F.2d 501------------ 14

Constitutional P rovisions:

United State Constitution, 14th Amendment ------- 2

Statutes:

28 U.S.C. 1254(1) _______________________________ 2

28 U.S.C. 1331 __________________________________ 2

28 U.S.C. 1343(3) _______________________________ 2

42 U.S.C. 1981, 1983 _____________________________ 2

42 U.S.C.A., Sec. 2000c (b) ----------------------------------- 10

42 U.S.C.A., Sec. 2000c-9-------------------------------------- 10

Text Books and M iscellaneous:

Article by Former Associate Justice Whittaker 1 2

In the

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1966

No.

The Board of Education of the Oklahoma City Pub

lic Schools, Independent D istrict No. 89, Oklahoma

County, Oklahoma, a public body corporate, et al.,

Petitioners,

V E R S U S

R obert L. D owell and V ivian C. Dowell, Infants, by A. L.

Dowell, their Father and Next Friend, Edwina Houston

Helton, a minor, by the Mother, Gloria Burse, and Gary

Russell, a minor, by his Father, George Russell,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE

TENTH CIRCUIT

The Board of Education of the Oklahoma City Publie

Schools, Independent District No. 89, Oklahoma County,

Oklahoma, a public body corporate,1 prays that a writ of

certiorari issue to review the judgment of the United States

Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit entered in the above

entitled case on January 23, 1967.

1 Other petitioners are: Jack F. Parker, Superintendent of the Oklahoma

City, Oklahoma Public Schools; M. J. Burr, Assistant Superintendent

of the Oklahoma City, Oklahoma Public Schools; Melvin P. Rogers,

Phil C. Bennett, William F. Lott, Mrs. Warren F. Welch and Foster

Estes, Members of the Board of Education of Oklahoma City Schools;

Independent District No. 89, Oklahoma County, Oklahoma, and their

Successors in Office.

— 2 —

CITATIONS TO OPINIONS BESTOW

There were two opinions of the District Court. The first

(R. 50) is reported in 219 F.Supp. 427. The second (R. 147)

is reported in 244 F.Supp. 971.2 The opinions of the Court

of Appeals3 are unreported and are printed in Appendix

“A ” hereto.

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered on

January 23, 1967. Rehearing was denied on March 15, 1967.

The Judgment and Orders denying rehearing are printed in

Appendix “B” hereto. The jurisdiction of this Court is in

voked under 28 U.S.C. 1254(1). Jurisdiction of the District

Court was invoked under 42 U.S.C. 1981, 42 U.S.C. 1983,

Title 28 U.S.C. 1343(3), Title 28 U.S.C. 1331, and the Four

teenth Amendment to the Constitution.

Q U E S T IO N S P R E S E N T E D

1. Whether the District Courts of the United States

have authority to impose on a Board of Education the

affirmative duty to recast or realign school attendance

districts for the purpose of mixing or blending Negro

and white students in a particular school or schools.

2. Whether the District Courts of the United States

have the authority to order a Board of Education to

adopt a transfer policy under which pupils assigned to

schools in which their race predominates are given the

2 Ten copies of the printed record are being filed with this petition,

and the reported opinions are therefore not printed herein.

3 There are three, the majority, concurring, and dissenting.

— 3—

right to transfer to schools in which their race is in the

minority, absent any showing or effort to show the ex

istence of unlawful discrimination.

3. Whether the District Courts of the United States

have the authority to direct a Board of Education to as

sign faculty personnel among the schools of the entire

school district so that by a prescribed time the ratio of

whites to non-whites in each school will be the same,

with a reasonable leeway, as they comprise at the time

of the court’s order, in the whole school system, absent

a finding that unlawful discrimination in the assign

ment of Negro teachers has occurred or is occurring.

4. Whether a District Court of the United States,

notwithstanding an affirmative finding that a Board of

Education has in good faith attempted to operate a

school system in accordance with the directions of such

court, may peremptorily order the Board to take af

firmative, specified action, the only objective of which

is to reduce or eliminate racial imbalance.

STATUTES AM® CONSTITUTIONAL

PROVISION INVOLVE®

The statutes and Constitutional provision involved are

printed in Appendix “ C” hereto.

STATEMENT

The original complaint (R. 1) was filed on behalf of

four minor Negro plaintiffs by their parents and next

friends against the Board of Education of the Oklahoma

City Public Schools, the Superintendent and Assistant

Superintendent thereof, and the members of the Board of

Education. It was alleged that the defendants had been and

were then pursuing a policy, practice, custom and usage of

4 -

operating a qualified bi-racial school system in Oklahoma

City, that attendance areas of certain schools overlapped,

and that white and Negro children were required to go to

schools attended only by members of their own race. Plain

tiff A. L. Dowell, father and next friend of two of the

plaintiffs, specifically alleged that he had sought transfer

of his children from Douglass High School, an all-Negro

school, to Northeast High School, attended by children of

both races, and that the application was denied unless

Robert L. Dowell took a course in electronics, solely because

he was a member of the Negro race. The relief sought was

that the petitioners, who were there defendants, be en

joined from operating such a system and from granting or

denying transfers on the basis of race and color.

In their answer (R. 7) defendants denied the alle

gations of discriminatory practices and affirmatively al

leged that the application of Robert L. Dowell for transfer

had been granted. This affirmative allegation was never

controverted.

A First Amended Complaint (R. 9) was filed in which

certain statutes of the State of Oklahoma requiring the

maintenance and operation of separate schools were al

leged to be unconstitutional. At pre-trial, the Board con

ceded the unconstitutionality of the statutes under attack

(R. 22).

A Second Amended Complaint (R. 33) alleged that the

Board had adopted and often enforced a policy, practice,

custom and usage of assigning students, faculty and ad

ministrative personnel on the basis of racial identity of the

racial group of which the student body is composed, and

that by reason thereof the schools in the district were

— 5—

“racial segregated schools contrary to and in violation of

the Constitution and laws of the United States.”

In its Answer (R. 41) the Board generally denied the

allegations of the Second Amended Complaint, and among

other things, affirmatively alleged that every pupil residing

within an attendance area must attend the school serving

that area unless granted a transfer, none of which had been

granted because of race or color.

An evidentiary hearing was held on May 10, 1963, fol

lowing which the court rendered an opinion (R. 50) and

directed the Board to file a complete and comprehensive

plan for the integration of the Oklahoma City school sys

tem, both as to student body and teaching and supervisory

personnel.

The Board filed a program of compliance (R. 46) and

a Clerk’s minute for August 8, 1963 (R. 50) recites:

“ Court approves School Board plan but will file his

findings in a few days.”

On February 14, 1964, a further hearing was held, at

the conclusion of which the court observed:

“I believe that the report that has been filed here

with the court of the School Board’s intentions that it

is filed in good faith, that they intend to integrate these

schools in good faith” (R. 193).

On February 28, 1964, a further hearing was held, at

which the court suggested that the Board of Education em

ploy an expert to make a study of what it referred to as

“these problems” (R. 200). The Board, by letter of March

26, 1964 (R. 83), respectfully declined to employ outside

experts. The court then entered an order (R. 90) desig

■6—

nating three persons suggested by the plaintiffs to make “ a

study of the situation” and report to the court. Such a

study was made and a report filed (R. 92). Following a

hearing on the report held on August 9 and 10, 1965 (R.

203-362) the court rendered its final opinion (R. 147) and

entered its order (R. 162).

The order directed that the Board prepare and submit

by October 30, 1965, “a further desegregation plan purposed

to completely disestablish segregation in the public schools

of Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, as to both pupil assignment

and transfer procedures, and hiring and assignment of all

faculty personnel,” and that “Said plan shall further specifi

cally provide for:

“ 1. New school district lines for the Harding and

Northeast High School attendance districts and the

Classen and Central school attendance districts drawn

in accordance with recommendations relating to said

school attendance districts as contained in the Inte

gration Report to the end that effective no later than

the start of the 1966-67 school year:

“a. The Harding (7-12) school attendance district

and the Northeast (7-12) school attendance district

shall be combined into one school attendance district,

the northern boundary of which, upon the opening of

the Eisenhower Junior High School, shall be 50th

Street. In the new Harding-Northeast school attend

ance district, Harding shall house all pupils residing in

the said new district and eligible to be enrolled in

either grades 7-9 or 10-12, and Northeast shall house

all pupils eligible to attend either grades 7-9 or 10-12.

The decision as to which school shall serve grades 7-9

and which school shall serve grades 10-12 shall be left

to the sound discretion of the school board, based on

an appraisal of existing permanent facilities and the

location of other secondary school facilities;

■7—

“ b. The Classen (7-12) school attendance district

and the Central (7-12) school attendance district shall

be combined into one school attendance district. In the

Classen-Central school attendance district, Classen

shall house all pupils residing in said new district and

eligible to be enrolled in either grades 7-9 or 10-12, and

Central shall house all pupils eligible to attend either

grades 7-9 or 10-12. The decision as to which school

shall serve grades 7-9 and which school shall serve

grades 10-12 shall be left to the sound discretion of the

school board, based on an appraisal of existing perma

nent facilities and the location of other secondary

school facilities.

“2. A new ‘majority to minority’ transfer policy,

under which policy all pupils initially assigned to

schools where pupils of their race predominate (over

50%) shall be permitted to request and obtain trans

fer, if space permits, to schools in which pupils of their

race will be in a minority (under 50%), and such

transfer shall make that bis permanent home school

for the grades it provides. Such transferee shall have

all of the rights of the school, academic programs, and

athletic programs, notwithstanding any rules to the

contrary, inasmuch as the law of desegregation super

sedes any rules requiring residence and time.

ij: * * * ❖ *

“4. Faculty desegregation of all faculty personnel,

i.e., central administration, certified nonteaching and

teaching personnel, so that by 1970, the ratio of whites

to non-whites assigned in each school of the defend

ants’ system will be the same, with reasonable leeway

of approximately 10% as the ratio of whites to non

whites in the whole number of certified personnel in

the Oklahoma City Public Schools.”

— 8 —

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE W RIT

1. The decision of the court below is in direct conflict

with:

(a) That of the Seventh Circuit in Bell v. School City

of Gary, Indiana, 324 F.2d 209, cert, denied 379 U.S. 924, 84

S.Ct. 1223, 12 L.Ed.2d 216.

(b) That of the Sixth Circuit in Kelley v. Board of

Education, 270 F.2d 209, cert, denied 361 U.S. 924, 80 S.Ct.

293, 4 L.Ed.2d 240.

(c) Its own in Downs v. Board of Education of Kansas

City, 336 F.2d 988, cert, denied 380 U.S. 914.

(d) The clearly expressed intention of Congress.

In Bell, the Court pointed out:

“Plaintiffs are unable to point to any court decision

which has laid down the principle which justifies their

claim that there is an affirmative duty on the Gary

school system to recast or realign school districts or

areas for the purpose of mixing or blending Negroes

and whites in a particular school.” ,

and said:

“We agree with the argument of the defendants

stated as ‘There is no affirmative United States consti

tutional duty to change innocently arrived at school

attendance districts by the mere fact that shifts in

population either increase or decrease the percentage

of either Negro or white pupils.’ ”

The Court approved the statement found in Brown v.

Board of Education (D.C.), 139 F.Supp. 468, that:

“Desegregation does not mean that there must be

intermingling of the races in all school districts. It

— 9—

means only that they may not be prevented from inter

mingling or going to school together because of race or

color.”

In Kelley, the Court quoted with approval the same

statement from Brown v. Board of Education, supra, as had

the Seventh Circuit in Bell, and adopted and approved a

statement contained in Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F.Supp. 776

where, in referring to the rule announced by this Court in

the desegregation cases, the Court said:

“ ‘It has not decided that the federal courts are to

take over or regulate the public schools of the states.

It has not decided that the states must mix persons of

different races in the schools or must require them to

attend schools or must deprive them of the right of

choosing the schools they attend.

* * * * * *

“ ‘The Constitution, in other words, does not require

integration. It merely forbids discrimination. It does

not forbid such segregation as occurs as the result of

voluntary action. It merely forbids the use of govern

mental power to enforce segregation.’ * * *”

In Downs, the Tenth Circuit itself, in rejecting a con

tention that even absent intentional segregation there was

still segregation in fact in the Kansas City school system,

and that under the principles of Brown the Board had a

positive and affirmative duty to eliminate segregation in

fact as well as segregation by intention, said:

“While there seems to be authority to support that

contention, the better rule is that although the Four

teenth Amendment prohibits segregation, it does not

command integration of the races in the public schools,

and Negro children have no constitutional right to have

white children attend school with them.”

1 0 —

Although not controlling, and if constitutional rights

are violated, clearly ineffective, Congress in the Civil Rights

Act of 1964 was careful to spell out the limits of the Act.

It defined desegregation as follows:

“ ‘Desegregation’ means the assignment of students

to public schools and within such schools without re

gard to their race, color, religion, or national origin,

but ‘desegregation’ shall not mean the assignment of

students to public schools in order to overcome racial

imbalance.” 42 U.S.C.A., Sec. 2000c (b).

And in order to make its intention perfectly clear, further

said:

“Nothing in this subchapter shall prohibit classifi

cation and assignment for reasons other than race,

color, religion, or national origin.” 42 U.S.C.A., Sec.

2000c-9.

The majority opinion in this case has approved action

of the District Court which, under the record, can be de

signed and intended only to blend or mix the races in the

designated areas. It may be that the court below acted un

der the mistaken belief that the District Court found and

believed that the Board had not acted in good faith in at

tempting to implement the decision in Brown.4 Completely

contrary to any such finding or belief is the statement of

the District Court that:

4 The concurring opinion clearly reflects that this was. true, since the

writer says: "I start with the premise of the trial court’s finding that

the Board of Education, despite statements o f completely acceptable

policy, had not acted in good faith in effectuating such policies after

having been afforded opportunity to do so.” The dissenting Judge

apparently acted under the same misconception as the majority, but

found no support for such a finding in the record.

— 11

“The School Board has instituted the changes in its

policy and administration required by this Court’s or

der of July, 1963, and has in good faith attempted to

administer the school system in accordance with these

changes” (R. 149).

Regardless of the reasons which impelled the majority

to affirm the District Court’s order, the opinion runs coun

ter to those of other circuits and their own in Downs. This

irreconcilable conflict should in and of itself warrant and

require the granting of the writ.

2. Ever since Brown, the questions here presented

have plagued the courts, as well as elected school officials,

throughout the country, and are causing untold confusion

and disagreement among those courts which have been con

fronted with them. This Court should delineate and refine

the teaching of Brown. Answers to the questions presented

will undoubtedly reduce the enormous volume of racial liti

gation and provide specific guidelines for officials who are

primarily expected to carry out the mandates of this and

other courts.

The uncertainty which prevails was recognized by the

District Court when, in its opinion, 244 F.Supp. at 978, it

said:

“While the full implications of the Supreme Court’s

decision in Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483,

74 S. Ct. 686, 98 L. Ed. 973 (1954) remain uncertain,

this court concludes that action thus far taken by the

defendant School Board falls far short of providing the

desegregated education envisioned in the Brown opin

ion as the constitutional right of plaintiffs and the class

they represent.”

■12—

The importance of deciding the questions presented is

clear.

3. The decision of the court below is believed to be

erroneous and those of the Sixth, Seventh, and indeed that

of the Tenth Circuit itself in Downs•, correct. It is felt that

the conflict grows out of confusion concerning the use and

true meaning of the terms “discrimination,” “segregation,”

“desegregation,” and “integration.”

Former Associate Justice Whittaker, evidently feeling

the same way, in an article published in the March issue of

Pageant Magazine, wrote:

“We hear much confused argument revolving around

the terms ‘discrimination,’ ‘segregation,’ ‘desegrega

tion,’ and ‘integration.’ So I think it may be well briefly

to consider what they really mean.

“The dictionary sense of the term ‘discrimination’ is

also, in the abstract, its legal sense. In its constitutional

sense it is one of the things prohibited to the states by

the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee of ‘the equal

protection of the laws.’

“The term ‘segregation’ is, in legal effect, only a

synonym for constitutionally prohibited ‘discrimina

tion.’ The term ‘desegregation’ is a coined one of awk

ward and dubious meaning.

“But the term ‘integration,’ a term of no consti

tutional significance, though commonly used as a syno

nym of ‘antidiscrimination’ or ‘antisegregation,’ liter

ally has a very different meaning and embraces the

concept of amalgamation, well-illustrated by the trans

fer of schoolchildren from their home district to a dis

tant district for the purpose not of avoiding unconsti

tutional ‘discrimination’ but of affirmatively ‘mixing’

or ‘integrating’ the races when indeed no provision of

the Constitution so requires.

— 13—

“Yet in recent times we have seen obvious attempts

largely through the repeated use of the coined and

meaningless phrase ‘de facto segregation’—-to torture

the word ‘integragtion’ into a meaning synonymous

with constitutionally prohibited ‘segregation,’ when in

truth they speak entirely different concepts. There is,

of course, a clear basis in the fundamental law of our

land, particularly in the Fourteenth Amendment, for

striking down state acts of ‘discrimination,’ and hence

also of ‘segregation,’ in all public institutions, including

state public schools, as violative of that Amendment’s

guarantee of the equal protection of the laws.

“But, as stated, there is no provision in the Consti

tution which in terms of intendment compels ‘inte

gration’ of the races.”

The foregoing quotation is not urged as compelling au

thority, but is used because the author expresses much

more clearly and concisely what the writer of this petition

believes to be true, than he could.

Supposedly all would agree that the constitutional

rights of Negroes should and must be protected. However,

in every case it is imperative that a clear understanding of

the rights involved must precede an intelligent evaluation

and analysis of the facts in order that the nature and ex

tent, if any, of relief may be determined. In every case

involving the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment, the first and basic question which must be

resolved is: Have the complainants been subjected to dis

criminatory practices which deny them the equal protection

afforded by the Fourteenth Amendment?

It is the sincere belief of petitioners that in many of

the cases in which racial questions have been raised the

courts have, in their zeal to evidence their concern for the

plight of many Negroes, overlooked the fact that:

— 14—

“The sound test of judicial responsibility is not, of

course, its lavishness of concern, but its measured ad

herence to the actual legal need of, and its authority

in, the situation with which it is required to deal.

Over-responsibility may be as much an abuse of ju

dicial power and function as irresponsibility.” 5

The action of the District Court, particularly in the

area of recasting the existing school attendance areas and

directing the Board how to use the existing facilities grade-

wise, can hardly be accounted for except that its over-

concern motivated such action, which constituted an abuse

of its judicial power and function and an unauthorized in

vasion of the powers and functions of the Board.

The constitutional protection afforded by the Four

teenth Amendment requires that equal treatment—nothing

more—be accorded all citizens. It is interesting to note that

neither the District Judge nor either of the concurring

Judges point to a single instance of discriminatory treat

ment. This is accounted for by the fact that nobody—pupil

or teacher—said that there was any. As the dissenting

Judge pointed out:

“The trouble with this case is that it deals with

generalities rather than specific. Discriminatory prac

tices are barred and must not be condoned. Here the

court does not find any explicit discriminatory act. It

says that the Board has not acted in good faith in the

preparation of a plan for integration and forces details

of a plan on the Board. I believe that the courts should

confine their decisions to actual controversies related to

specific rights, and should not take over the operation

of public affairs entrusted to other governmental

institutions.”

5 1Vailing v. Benson (C.A. 5 ) , 132 F.2d 501 at 504.

— 15—

Concerning that portion of the District Court’s order

directing a consolidation of four existing school attendance

areas, he said:

“The court said that the plan should provide new

district lines for four schools. The effect is to consoli

date in two instances a Junior High School District

with a Senior High School District. No finding is made

as to the physical characteristics of the facilities or to

the types of curriculum. In my opinion, this is a gratui

tous judicial interference with the duties and responsi

bilities of the Board, is made without any supporting

findings except the possibility of thereby in the future

reducing the imbalance of the races, and is not required

to protect any Fourteenth Amendment right.”

It is believed these observations are well taken and

clearly pinpoint the error into which the majority of the

court below fell.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, this petition for a writ of

certiorari should be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

Coleman Hayes

1719 First National Building

Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 73102

Attorney for Petitioners

April, 1967

A P P E N D IX A

F I L E D

United States Court o f Appeals

Tenth Circuit

Jan 23 1967

W il l ia m L. W h it a k e r

Clerk

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

Tenth Circuit

January Term, 1987

The Board of Education of the Oklahoma City

Public Schools, Independent District No. 89,

Oklahoma County, Oklahoma, a public body

corporate, Jack F. Parker, Superintendent

of the Oklahoma City, Oklahoma Public

Schools, M. J. Burr, Assistant Superintend

ent of the Oklahoma City, Oklahoma Public

Schools, Melvin P. Rogers, Phil C. Bennett,

William F. Lott, Mrs. Warren F. Welch and

Foster Estes, Members of the Board of

Education of Oklahoma City Schools, Inde

pendent District No. 89, Oklahoma County,

Oklahoma, and their successors in office,

Appellants,

vs.

Robert L. Dowell and Vivian C. Dowell, in

fants, by A. L, Dowell, their father and next

friend, Edwina Houston Helton, a minor, by

her mother, Gloria Burse, and Gary Russell,

a minor, by his father, George Russell,

Appellees.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

) Number

) 8523

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

APPEAL FRO M THE, UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE, WESTERN DISTRICT1 OF OKLAHOM A

— 11—

[ A P P E N D I X ]

Coleman Hayes of Monnet, Hayes, Bullis, Grubb &

Thompson for Appellants;

Robert D. Looney for Amicus Curiae Harding High School

Parents Teachers Association;

Submitted on brief by Wheeler, Parsons & Wheeler for

Amicus Curiae Oklahoma Education Association;

Jack Greenberg (James M. Nabrit, III, and U. Simpson

Tate on the brief) for Appellees.

Before Lewis, Breitenstein and Hill, United States Cir

cuit Judges.

HILL, Circuit Judge.

This appeal is from an order enjoining appellants to

do certain enumerated administrative acts in order to

effectuate racial desegregation in the public school system

of Oklahoma City, Oklahoma.

The action was commenced in October, 1961, in the

Western District of Oklahoma as a class action seeking

equitable relief to enjoin the Board of Education of the

Oklahoma City Public Schools and the other named de

fendants from “operating a qualified bi-racial school sys

tem * * from “maintaining a dual scheme, pattern or

implied agreement or understanding of school zone lines

based upon race or color,” from maintaining “a minority to

majority” system of pupil transfers and from continuing

other racial discriminatory practices within the school

system. A three-judge court was requested and convened

because of the alleged unconstitutionality of certain state

statutes pertaining to the Oklahoma system of education.

It was determined, after a pretrial, that the controverted

issues left in the case did not require a three-judge court.

Such court was dissolved and the case returned to the

originally assigned judge.

[ A P P E N D I X ]

The case proceeded to trial before one of the district

judges, with the following issues involved: The validity of

existing pupil transfer plan and the alleged racial discrimi

nation resulting therefrom; racial discrimination in the as

signment of teachers and other employees of the defendant

school board; racial discrimination in the fixing of school

attendance boundary lines; and the broad issue of racial

segregation generally in the operation of the school system.

After an evidentiary hearing, on July 11, 1963, the

trial court rendered its first opinion.1 There the pupil trans

fer plan, then being followed and under attack in the liti

gation, was held invalid under Goss v. Board of Education,

373 U.S. 683. A general finding, following specific findings

of fact, was made that the board had not acted in good

faith in its efforts to “integrate” the schools of the city but

the court denied relief to some individual plaintiffs claim

ing personal discrimination because of lack of proof. One

important aspect here of that order was the direction from

the court to the school board to prepare and file with the

court, within ninety days, a complete and comprehensive

plan for the “ integration” of the entire Oklahoma City

School system and the court retained jurisdiction of the

case to assure compliance with the decree.2

— i i i —

1 Dowell v. School Board of the Oklahoma City Public Schools, 219

F. Supp. 427.

2 In this opinion, the trial court made the following important and

specific findings o f fact:

"* * * The Court has searched the record carefully and finds no

tangible evidence to show the defendants have made a good faith

effort to integrate the public schools of Oklahoma City beyond the

August 1, 1955 resolution, notwithstanding eight years have now

passed, which is more time than necessary within which to begin to

adjust the inequities which have existed unnecessarily so long, and

the record is void of any evidence to indicate that the defendant

School Board will make any improvement in the future” (219 F.

Supp. at 435).

"The Court finds and concludes from the evidence that the School

Board has not acted in good faith in its efforts to integrate the

Oklahoma City Public Schools, as defined and required in the Brown

— i v

Pursuant to the order, the board filed what it called

a “Program of Compliance with Court’s Order.” This state

ment by the board asserted it had established the school

attendance boundaries by using only two criteria: (1) That

they represent logically consistent geographical areas that

support the concept of neighborhood schools and (2) that

there be as efficient as possible utilization of the building

facilities available. The board stated that under no circum

stances would it consider the race of the residents of an

area in the school district either in the establishment or

the adjustment of attendance area boundaries but that

“Basically pupils will attend the schools which serve the

attendance areas in which they reside.” The board stated

that it would no longer make special transfers on a racial

minority to majority basis but would continue to grant

transfers to enable a student to transfer out of his “neigh

borhood” school to another school where the transfer: (1) 2

[ A P P E N D I X ]

2 ( Continued)

cases, as to pupils and personnel. * * * The school children and per

sonnel have in the main from all o f the evidence been completely

segregated as much as: possible under the circumstances, rather than

integrated as much as possible. Inasmuch as the (Superintendent o f

Schools has established the proof necessary that Negro teachers are

equal in quality to the white teachers, it seems only reasonable and

fair that in all schools, mixed or otherwise, the School Board, would

and should make a good faith effort to integrate the faculty, in order

that both white and Negro students would feel that their color was

represented upon an equal level and that their people were sharing

the responsibility of high-level teaching” (444, 445).

"* # * Since August 1, 1955, the only integration has been in the

fringe areas as between minority Negro residential pattern and the

majority white residential pattern. For instance, there are 14 ele

mentary and secondary schools that have some degree of integra

tion, out o f 101 school plants. However, the re-districting of schools

has meant little or nothing in view o f the policy 'minority to ma

jority’ and as long as this policy is continued there will never be a

good faith desegregation and integration of the public schools of

the Oklahoma City district” (446).

"From a study of the evidence in this case, the Court concludes

that the Oklahoma City School Board has followed a course of inte

gration as slowly as possible” (447).

■V—

Would enable the student to take a course not available

in his attendance area and the course “is important to the

total education” of the student; (2) would enable members

of the same family to go to school together; (3) would

allow a student to complete the highest grade in a school

he has been attending; or (4) for “other valid, good-faith

reasons which justify approval.” The board stated that “ in

no case will these reasons be based in whole or in part on

race.” The board asserted in general terms its intention to

integrate faculty personnel, extra-curricular activities, com

mittee work, and “all types and kinds of activities involv

ing student participation.”

A hearing was held on August 8, 1963, upon the suf

ficiency of the plan filed by the board. After this hearing,

the court instructed the board to file a new policy state

ment. On January 14, 1964, this statement was filed. In

general terms, it reiterated the policies contained in the

earlier plan filed with the court. After another hearing on

this policy statement, the court found that while the board

had presented “a very fine plan,” there remained “doubt

in the heart of the Negro pupils as to the good faith opera

tion of the plan.” The court thereupon requested the board

to employ competent and unbiased experts, independent

of local sentiment, to make a survey of the “ integration

problem” as it related to the Oklahoma City public schools.

The board declined the request, on grounds that it would

be an unnecessary and unjustifiable expense and that the

board itself was more qualified to assess local problems and

was more sensitive to local needs. The court then invited

the plaintiffs to present for its consideration the names of

three experts in the field of “school integration.” In due

time, the plaintiffs moved the court to appoint Dr. William

R. Carmack of Norman, Oklahoma, Dr. Willard B. Spauld

ing of San Francisco, California, and Dr. Earl A. McGovern

of New Rochelle, New York,3 to undertake a broad study

[ A P P E N D I X ]

3 From the record these three men are eminently qualified in the

area of public education and they have experience and proven ability

in dealing with the problem of school segregation.

-----VI-

of the Oklahoma City public schools and recommend to

the court “a desegregation plan which will accord with

the letter and spirit of Brown v. Board of Education, 347

U.S. 483 (1954).” On June 1, 1964, the motion was granted

and an appropriate order entered.

Before considering the report of the three experts, a

brief recital of the history of race segregation in the Okla

homa City schools is appropriate. School segregation of the

races was written into the State Constitution. Separate but

like school accommodations were required. State statutes

implementing the Constitutional provision provided: For

complete separation of the races in the public schools; school

boards had to be composed exclusively of members of the

white race; segregation was compelled in private educa

tional institutions; and, any school official who permitted

a child to attend school with members of the other race

or any student who attended school with members of the

other race was guilty of a misdemeanor. A pattern of racial

segregation in housing was strictly adhered to with re

strictive covenants in general use for many years. The

Negro residents of the city had lived through the years

mostly in the east and southeast portions of the city, thus

the all-Negro schools were located in that part of the city.

This was the situation when the Supreme Court handed

down the Brown decision.

In 1955, following Brown, the board enunciated a policy

statement, by which school attendance boundaries were

drawn and the “minority to majority” pupil transfer plan

was announced.4 The school system then began operation

[ A P P E N D I X ]

"Statement Concerning Integration Oklahoma Public Schools 1955-

1956

"August 1, 1955

"All will recognize the difficulties the Board of Education has met

in complying with the recent pronouncement of the United States

Supreme Court in regard to discontinuing separate schools for white

and Negro children. The Board of Education asks the cooperation

on the “neighborhood school attendance policy” with a

feeder school plan. Attendance lines were drawn around

the existing school buildings, taking into consideration stu

dent capacities of the buildings and natural boundaries

such as rivers, highways and railroad lines and shifts in

population. The feeder plan required students graduating

from their particular elementary school to attend a desig

nated junior high school and junior high school graduates

to attend designated high schools. The minority to majority

pupil transfer plan then permitted any student, who was

enrolled in a school where his race was in the minority,

to transfer to a school where his race was in a majority,

provided space was available in the latter.

The record reflects very little actual desegregation of

the school system between 1955 and the filing of this case.

During that six year period segregation of pupils in the

system had only been reduced from total segregation in

1955 to 88.3 percent in 1961. Total segregation still existed

as to factulty members, administrative employees and all

other supporting personnel within the system. Between the

school years 1959-60 to 1964-65 the total number of all-

white schools had increased from 73 to 81, the total number

of all-Negro schools had increased from 12 to 14 and the

total number of integrated schools from 7 to 12. Between 4

4 (Continued)

and patience of our citizens in its compliance with the law and mak

ing the changes that are necessary and advisable. This action requires

the Oklahoma Board of Education to change a system which has been

in effect for centures and which is desired for many o f our citizens.

"Boundaries have been established for all schools. These boundaries

are shown on a map at the City Administration Building and maps

are being distributed to each school principal. These new boundaries

conform to the policies always followed in establishing school

boundaries. They consider natural geographical boundaries such as

major traffic streets, railroads, the river, etc. They consider the

capacity of the school. Any child may continue in the school where

he has been attending until graduation from that school. Requests for

transfers may be made and each one shall be considered on its merits

and within the respective capacity of the buildings.”

— V l l l —

the school years 1954-1955 and 1980-1981 the total Negro

pupil population in the system had increased from 5,477

to 10,142, and by 1964-1965 it had increased to 12,503.

The court-appointed expert panel’s report was com

pleted and filed in January, 1965. It reflected that out of

a total Negro or non-white school population of 12,503, in

the school year 1964-65, about 10,000 or 80% attended all-

Negro or predominantly Negro schools.5 Thus, in the four

schools years during this litigation in the District Court,

although the absolute number of Negroes in integrated

schools more than doubled, only 8.3% of the relative Negro

school population moved into integrated schools. To this

it might be added that in 1961-62 there were 13 schools

attended 95% or more by Negroes, and in 1964-65 there

were 14 schools attended 95% or more by Negroes.

The board’s special transfer policy which went into

effect in the 1963-64 school year was given consideration

by the panel. On the basis of figures showing that more

white students than non-white students had been granted

special transfers, especially under the valid-good-faith rea

son test, the panel concluded that the policy provided “an

effective loophole” for white school children.

The panel also dealt in some detail with the situation

in the Oklahoma City School system with respect to the

integration of faculty.6 The panel concluded that “There

was concrete evidence in [the school year of] 1964-65 that

the Oklahoma City Public Schools were taking more vigor

ous steps to integrate the faculty of its integrated schools.

These steps, however, only took place in previously inte

grated schools. In other words, little or nothing was done

[ A P P E N D I X ]

5 A predominantly Negro school, as defined by the expert panel, is

one having non-white enrollment o f 95% or greater.

6 The panel defined "faculty” as including three categories of certified

employees: (1 ) Those at work in the central administration of the

Oklahoma City Public Schools; (2 ) Those who constitute non

teaching personnel at the individual schools; and (3 ) Teachers.

•IX-----

[ A P P E N D I X !

to integrate the staffs of schools that were all white or all

non-white.” Included in the panel’s report was a plan for

integration of the Oklahoma City public schools.

A hearing was held on the report in August, 1965,

and the trial court, on September 7, ordered the Board of

Education to prepare and submit a plan substantially iden

tical to that set out in the report. Among the specific recom

mendations found in the report and embraced by the trial

court’s order w ere:7

(1) Combination of the Classen School (grades 7-12,

all-white) and the Central School (grades 7-12, 69% white)

attendance districts into a single district with one school

housing grades 7-9, the other housing grades 10-12.

(2) Combination of the Harding School (grades 7-12,

all white) and the Northeast School (grades 7-12, 78%

white) attendance districts into a single attendance district

with one school housing grades 7-9, the other housing grades

10- 12.

(3) A majority-to-minority transfer policy whereby,

space permitting, students initially assigned to schools

where their race is in the majority (over 50%) are en

titled to transfer to schools where their race is in the

minority.

7 In addition, the order appealed from directed:

"1. That the Board prepare and submit by October 30, 1965, 'a

further desegregation plan purposed to completely disestablish segra-

gation in the public schools of Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, as to both

pupil assignment and transfer procedure, and hiring and assignment

o f all faculty personnel.’

"2. That the plan shall provide:

' (1 ) a statement of goals to be achieved,

' ( 2 ) descriptions of procedures to be followed to achieve

such goals,

' ( 3 ) a statement o f the personnel to be responsible for carry

out said procedures, and

' ( 4 ) a reasonably early time schedule o f specific steps to be

taken to attain the stated goals.’ ”

-X—

[ A P P E N D I X ]

(4) Desegregation of all faculty personnel so that by

1970 the faculty ratio of whites to non-whites in each

school will be the same as the faculty ratio of whites to

non-whites in the entire school system, subject to a reason

able tolerance of approximately 10%.

(5) In service education of faculty, including (a) city

wide workshops devoted to the consideration of school inte

gration, (b) special seminars, and (c) special clinics.

From this order or decree of the court, this appeal

was taken. After perfection of the appeal, the Harding High

School Parents Teachers Students Association and the Okla

homa Education Association each was permitted to file a

brief in the case as amicus curiae and participate in the

oral argument.

Inherent in all of the points raised and argued here

by appellants is the contention that at the time of the

filing of this case there was no racial discrimination in

the operation’of the school system. That contention should

be first considered. The question of the existence of racial

discrimination necessarily goes hand in hand with the ques

tion of the good faith of the board in efforts to desegregate

the system.

As we have pointed out, complete and compelled seg

regation and racial discrimination existed in the Oklahoma

City School system at the time the Brown decision became

the law of the land. It then became the duty of every school

board and school official “to make a prompt and reasonable

start toward full compliance” with the first Brown case.

It is true the board, in 1955, issued the policy statement

and implemented it by the drawing of school attendance

lines and inaugurated a “minority to majority” pupil trans

fer plan. The attendance line boundaries, as pointed out

by the trial judge, had the effect in some instances of lock

ing the Negro pupils into totally segregated schools. In

other attendance districts which were not totally segregated

the operation of the transfer plan naturally led to a higher

percentage of segregation in those schools.

C A P P E N D I X J

— xi

The parties in their briefs vigorously contend the trial

court exceeded its authority by, in fact, formulating a plan

for the desegregation of the school system and compelling

them to adopt and follow the plan. They further argue that

the order appealed from usurps the functions of the board

in that, by such order, the court has undertaken to operate

and manage a school system, where there has been no

Constitutional violation by the board.

We agree that in considering or reviewing acts of

school boards and officials, generally, the power of a court

of equity does not extend to the promulgation of rules or

regulations to be adopted and followed by such boards

and officials.8 This does not mean that when a court of

equity reaches the conclusion that unconstitutional racial

discrimination in a school system exists, the power of the

court ends. When the trial court here made such a finding

and pointed out the areas of discrimination, it was the clear

duty of the school authorities to promptly pursue such

measures as would correct the unconstitutional practices.

The courts are admonished by the second Brown case “In

fashioning and effectuating the decrees, the courts will be

guided by equitable principles.” Also, after giving weight

to public and private considerations, the courts must re

quire “a prompt and reasonable start toward full compli

ance with * * *” the order of the court.9

The trial court was clearly within its equitable powers

in ordering the board to present an adequate plan for de

segregation of the school system. The board presented no

plan, it only reiterated its general intention to correct some

of the existing unlawful practices. This was not compliance

with the order of the court. It was the existence of this

factual situation, due entirely to the failure and refusal of

the board to act, which created the necessity for a survey

8 See Downs v. Board of Education o f Kansas City, 10 Cir., 336 F.2d

988, cert, denied, 380 U.S. 914.

9 Brown v. Board o f Education, 349 U.S. 294.

[ A P P E N D I X ]

of the school system by a panel of experts. Even at this

point, the trial court patiently refrained from compelling

such a survey but asked the board to cause a survey of

the school system to be made. It was only after the board’s

refusal of this request that the court appointed the three

experts and directed them to make a survey.

Because of the refusal of the board to take prompt,

substantial and affirmative action after the entering of the

court’s decree, without further action by the court the

aggrieved plaintiffs, even with a favorable decree from the

court, were helpless in their efforts to protect their court-

pronounced Constitutional rights. Under these circum

stances it was the duty of the trial court to take appropriate

action to the end that its equitable decree be made effec

tive. Again, we go back to the second Brown case where

the trial courts were directed “to take such proceedings

and enter such orders and decrees consistent with this

opinion as are necessary and proper to admit to public

schools on a racially nondiscriminatory basis with all de

liberate speed the parties to these cases.”

Appellants lay great stress on this court’s opinion in

Downs v. Board of Education of Kansas City, 336 F.2d 988,

cert, denied, 380 U.S. 914, and urge that case requires a

reversal in this case. We do not agree. Downs came to this

court in a different setting than this case. Actually, about

the only similarity between the two cases is the fact both

involved the question of school desegregation. In Downs,

after a lengthy evidentiary hearing, the trial court struck

down a “minority to majority” transfer plan and then held

that the school board had acted in good faith in its efforts

to comply with Brown, supra, and the subsequent cases

involving school segregation. The evidence in Downs re

flected that a definite plan had been adopted by the board

to achieve desegregation of the school system and that very

substantial progress had been made toward the goal of inte

gration. In addition, the trial judge made an affirmative

factual finding of good faith on the part of the board and

substantial evidence supported the finding.

•— Xll----

-X lll-

[ A P P E N D I X )

As pointed out by appellants, we did not condemn or

strike down the “neighborhood school attendance plan” in

Downs, nor do we condemn such a plan here, if it is carried

out in good faith and is not used as a mask to further and

perpetuate racial discrimination. In Downs the trial court

found the plan was not being used to deprive students of

their Constitutional rights and here the trial court, in sub

stance, found to the contrary. It is still the rule in this

Circuit and elsewhere that neighborhood school attendance

policies, when impartially maintained and administered, do

not violate any fundamental Constitutional principle or

deprive certain classes of individuals of their Constitutional

rights.10 We agree with one of the experts when he testi

fied that the proposed plan does not ignore attendance

boundaries or the neighborhood concept of such boundary

lines. The majority to minority transfer plan, in conjunc

tion with the attendance boundary plan, eliminates any

question about Constitutional infirmities of the attendance

boundary plan being followed in Oklahoma City.

The most important question raised by appellants is

whether it was error for the trial court to order the board

to include certain specific procedures in its broad plan of

desegregation. Such action by a court of equity has seldom

been necessary in the long line of desegregation cases de

cided since the Brown cases. This has been true because

the school boards, generally, have accepted the court de

crees as guidelines and proceeded “with deliberate speed”

to formulate their own plans looking toward the objective

of integration. But this was not the situation here. We need

not recite again the facts in this record which conclusively

show that for ten years after the board enunciated its in

tention to abide the mandate of Brown appellees have taken

only such action as they have been compelled to take and

10 Downs v. Board of Education of Kansas City, 10 Cir., 336 F.2d 988,

cert, denied, 380 U.S. 914; Springfield School Committee v. Barks

dale, 1 Cir., 348 F.2d 261; Bell v. School City of Gary, Indiana, 7

Cir., 324 F.2d 209, cert, denied, 377 U.S. 924.

desegregation has been only of a token nature. Under the

factual situation here we have no hesitancy in sustaining

the trial court’s authority to compel the board to take spe

cific action in compliance with the decree of the court so

long as such compelled action can be said to be necessary

for the elimination of the unconstitutional evils pointed out

in the court’s decree. The procedures ordered by the trial

court must be viewed in light of this test.

The first of those procedures requires the consolida

tion of Harding and Northeast districts and Classen and

Central districts. Each of the old districts now maintains

a school including the seventh through the twelfth grades.

Upon consolidation, each of the two new districts would

maintain two schools in the existing facilities, one for the

seventh through the ninth grades and the other for the

tenth through the twelfth grades. The combination of Hard

ing and Northeast would produce a racial composition of

91% white and 9% non-white; the combination of Classen

and Central would produce a racial composition of 85%

white and 15% non-white. The present racial compositions

in the four schools are: Harding 100% white, Northeast

78% white, Classen 100% white and Central 69% white.

Under the new plan, the amount of traveling required by

pupils in the merged districts would be no greater than

some pupils in other parts of the system are now required

to travel and no bussing problem arises from the merger.

The court recognized this fact and expressly eliminated

the necessity for bussing in its plan. It is obvious this part

of the plan would result in a broader attendance base and

in a better racial distribution of the pupils.

We pass to consideration of the part of the order com

pelling factulty desegregation. The record reflects that a

higher percentage of non-white teaching personnel have

master’s degrees than do white personnel. The superin

tendent of schools admitted there was no difference in the

quality of performance between the white and non-white

personnel. At present, integration of personnel exists only

— XV-

in schools having both white and non-white pupils, with

no non-white personnel employed in the central adminis

tration section of the system. The existing situation reflects

racial discrimination in the assignment of teachers and

other personnel. The order to desegregate faculty is cer

tainly a necessary initial step in the effort to cure the evil

of racial segregation in the school system.11

To support the necessity for the required new “ma

jority to minority” pupil transfer plan, we must again look

to the trial court’s findings of fact and the parts of the

record in support of them. Appellants argue, such a re

quirement may be said to be compelling integration, rather

than prohibiting racial discrimination.

From 1955 until the court decree in 1963, the board

used the “minority to majority” pupil transfer plan. The

effect of this plan is fully set out in the court’s decree and

the plan was held invalid by that decree. The board readily

acquiesced in this invalidation and instituted a new trans

fer plan. By this policy the evils of the first plan were

perpetuated by allowing all pupils who had been trans

ferred under the “minority to majority” plan to remain in

the school to which the transfer was made. In addition, a

brother or sister of such transferred student is permitted

to transfer to the same school.12 Also, the plan contains

[ A P P E N D I X ]

11 See Bradley v. School Board o f the City of Richmond,, 382 U.S. 103;

Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198; Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Sepa

rate School District, 5 Cir., 355 F.2d 865; Board of Public Instruction

of Duval Co. Florida v. Braxton, 5 Cir., 326 F.2d 6l6 , cert, denied,

377 U.S. 924 and Kemp v. Beasley, 8 Cir., 352 F.2d 14.

12 As the District Court said in the order appealed from:

"Certain provisions of the special transfer policy, including, but

not limited to, the provision permitting transfer to make it possible

for two or more members o f the same family to attend the same

school, the provision allowing a pupil to complete the highest grade

in a school which he has been attending, and the provision permitting

transfer for valid, good faith reasons, give a continuing effect to the

'minority to majority’ transfer rule invalidated in this Court’s July,

1963, opinion. Under the provisions set forth above, pupils who ob-

what the board calls “the finding of other valid, good faith

reasons which justify approval of transfers.” These three

provisions in the existing transfer plan enabled segregation

by transfer in the school system in much the same way it

had been done under the “minority to majority” plan.12 13

The court so held and the record amply supports such a

finding.

The court-ordered transfer plan places no bussing re

quirement on the school system. Neither does it give the

student unlimited discretion in deciding where he will at

tend school because a transfer can be made only “ if space

permits.” On the other hand, the new transfer plan will

enable any Negro student in the system, who so desires,

to enjoy the desegregated education to which he has so

long been entitled and yet of which he has been inexcus

ably deprived. In view of the long wait the Negro students

in Oklahoma City have been forced to endure, after their

rights had been judicially established, we think that re

quiring the new transfer plan was within the court’s power

to eliminate racial segregation.

By paragraph 5 of the September 7, 1965, order of the

court, the board was directed to include in its plan “In

-----X V !----

[ A P P E N D I X ]

12 (Continued)

tained transfers away from their neighborhood schools to segregated

schools under the 'minority to majority’ transfer policy are not only

permitted to remain in such schools, but also provide a basis for

enabling all brothers and sisters to follow them from the schools

near their residences to segregated schools.”

13 The District Court found that:

"The special transfer policy as presently administered tends to

permit transfers for reasons no different or more valid than those

obtained under the now voided 'minority to majority’ transfer rule.

Such policy tends to perpetuate a segregated system, violates the

Boards asserted belief in the philosophy of the neighborhood school

system and, for several economic and sociological reasons, deprives

Negro pupils assigned to predominantly Negro schools who are

less able to obtain such transfers, o f the opportunity to obtain a

desegregated education.”

xvu-

[ A P P E N D I X ]

service education of faculty; * * *” and would require city-

wide workshops, special seminars and special clinics for

teachers and administrative personnel within the school

system. Such a program may very well be a desirable and

worthwhile effort but we are unable to say that compelling

such action is necessary for the elimination of the unconsti

tutional evils sought to be corrected by the decree. There

fore, the decree should be modified so as to eliminate this

requirement.

It must be conceded Oklahoma City, not unlike many

other similarly situated localities, has a problem but that

problem must be faced up to. Delay and evasiveness will

not aid in its solution. This court certainly cannot say the

methods of solution proposed by the panel of experts and

embraced by the decree are the only or the best ones. It

may very well be necessary for the board to inaugurate

new and additional procedures to overcome the unconstitu

tional evil of racial discrimination. It is not our function

to propose methods or procedures. The long line of court

decisions pertaining to desegregation handed down since

1954 is conclusive proof that no single formula provides

the sole remedy to cure the unconstitutional and intolerable

evil of racial discrimination. The appropriate remedy in

each instance depends upon the varient facts and circum

stances. We conclude that the remedy employed by the

court below, with the exception noted, is appropriate in

view of the facts and circumstances of this case.

The court appropriately retained jurisdiction of the

case and jurisdiction should be held until such time as the

court is satisfied that the decreed unconstitutional practices

are eliminated and appellant board is found to be in full

compliance with the teachings of the Brown case. The

decree appealed from is approved and AFFIRMED in all

respects except for the provision requiring “ in service edu

cation of the faculty” which should be eliminated there

from. The case is therefore remanded for further proceed

ings consistent herewith.

—xvm -

( . A P P E N D I X ]

LEWIS, Circuit Judge, concurring.

The result dictated by this disturbing case is largely

determined by the premise from which reasoning springs

and the terminology used in advancing argument. I start

with the premise of the trial court’s finding that the Board

of Education, despite statements of completely acceptable

policy, had not acted in good faith in effectuating such

policies after having been afforded opportunity to do so.

The authority of the trial court under such circumstances

to prescribe positive action for purposes of curing a con

tinuing situation that has traditionally denied to many a

constitutional right, as with legislative re-apportionment

problems, seems firmly established. But, of course, the cure

cannot survive if it in turn reflects an unconstitutional im

position, and in this regard terminology can become a

persuasive tool in analysis.

I have no quarrel with the statement that forced in

tegration when viewed as an end in itself is not a com

pulsion of the Fourteenth Amendment. But any claimed

right to disassociation in the public schools must fail and

fall. If desegregation of the races is to be accomplished in

the public schools, forced association must result, not as

the end sought but as the path to elimination of discrimi

nation. And, to me, the argument that racial discrimination

cannot be eliminated through factors of judicial considera

tion that are based upon race itself is completely self-

denying. The problem arose through consideration of race;

it may now be approached through similar but enlightened

consideration.

Again noting that the case reaches us for review of

the affirmative action of the trial court it seems proper to

emphasize that we do not set out consolidation of schools

and the majority-to-minority transfer policy as compulsive

instruments to accomplish desegregation. But we do hold

that such means are not violative of the constitutional

rights of any and might properly have been utilized by

the School Board, and, in its stead, were available to the

-X IX —

[ A P P E N D I X ]

trial court. The contrasting policy of minority-to-majority

transfer, denied in Goss, perpeutated discrimination; here,

a start is made toward full compliance with Brown.

BREITENSTEIN, Circuit Judge, dissenting.

The district court made a general finding that the

Board of Education had not acted in good faith to de

segregate the Oklahoma City public schools. This finding

is not supported by any specific and uncorrected discrimi

natory practices. The court has assumed the authority to

tell the Board how it shall perform some of its public duties

to the end that integration may be attained.

My basic difference with the majority is that I see

nothing in the Fourteenth Amendment that compels inte

gration. To me discrimination and integration are entirely

different. Discrimination is the denial of equal rights. Inte

gration is compulsory association. Each is concerned with

individual rights and each must be tested against the same

constitutional standards.

The trouble with this case is that it deals with generali

ties rather than specific. Discriminatory practices are bad

and must not be condoned. Here the court does not find

any explicit discriminatory act. It says that the Board has

not acted in good faith in the preparation of a plan for

integration and forces details of a plan on the Board. I

believe that the courts should confine their decisions to

actual controversies related to specific rights and should

not take over the operation of public affairs entrusted to

other governmental institutions.

Prior to Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483,

the Oklahoma schools were segregated. Promptly after that

decision the Board opened the schools to all. It did un

wisely adopt a minority-to-majority transfer policy but

promptly after Goss v. Board of Education, 373 U.S. 683,

it abandoned that policy and set up a transfer system which

gave no regard to race. There is no evidence that since

the adoption of that system any child of any race has been

■— X X -

discriminated against. The unsupported suspicion of the

plaintiffs’ experts that the operation of the transfer policy

has redounded to the disadvantage of negro children is in

sufficient basis for a finding of discrimination when weighed

against the Board’s positive evidence of no discrimination.

The dissatisfaction of the court with the Board’s re

fusal to accept the court’s request for the employment of

experts is no basis for the decision rendered. Judicial pique

cannot replace the actual infringement of a constitutionally

protected right.

The court ordered the Board to submit “a further de

segregation plan.” In my opinion this portion of the order

is not appealable. See Taylor v. Board of Education, 2 Cir.,

288 F.2d 600. The court said that the plan should provide

new district lines for four schools. The effect is to consoli

date, in two instances, a junior high school district with

a senior high school district. No finding is made as to the

physical characteristics of the facilities or to the types of

curriculum. In my opinion this is a gratuitous, judicial in

terference with the duties and responsibilities of the Board,

is made without any supporting findings except the possi

bility of thereby in the future reducing the imbalance of

the races, and is not required to protect any Fourteenth

Amendment right. If the Board believes it appropriate to

redraw district lines to alleviate racial imbalance, it may

do so and any person who believes himself aggrieved by

such action may seek judicial relief. Action by the Board

is vastly different from action by the court.

In my opinion the judicial compulsion of the majority-

to-minority transfer policy is indefensible. The Goss de

cision says (373 U.S. 687): “Classifications based on race

for purposes of transfers between public schools, as here,

violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment.” A rnajority-to-minority transfer is based on

race. No more need be said. If the Board determines to

use transfers to alleviate racial imbalance, it may do so with

the qualification that a person who believes his constitu

tional rights are infringed thereby may seek judicial relief.

[ A P P E N D I X ]

-X X I—

[ A P P E N D I X ]

The court ordered desegregation of faculty personnel

“so that by 1970, the ratio of whites to non-whites assigned

in each school of the defendants’ system will be the same”

with a 10% leeway. Here again we have a classification

based on race. The stated policy of the Board is: “Oppor

tunity to apply for and be equal for any positions that may

be available in the school system will be given to all with

out regard to race, color, creed, religion, or national origin.”

The record is devoid of any evidence that the Board has

deviated from this policy in any regard. In my opinion the

Board policy is constitutionally correct and the court order

on faculty integration is wrong.

I agree with the majority that the provision of the

order for in-service faculty education cannot be sustained.

APPENDIX “B”

— x x u —

[ A P P E N D I X ]

Judgment

Fourteenth Day, January Term, Monday, January 23rd,

1967.

Before Honorable David T. Lewis, Honorable Jean S.

Breitenstein and Honorable Delmas C. Hill, Circuit Judges.

This cause came on to be heard on the transcript of the

record from the United States District Court for the West

ern District of Oklahoma and was argued by counsel.

On consideration whereof, it is ordered and adjudged

by this court that the decree appealed from is affirmed in all

respects except for the provision requiring “in service edu

cation of the faculty” which should be eliminated there

from. The case is therefore remanded for further proceed

ings consistent with the opinion of the court.

Order denying petition for rehearing en banc

Forty-Seventh Day, January Term, Wednesday, March

15th, 1967.

Before Honorable Alfred P. Murrah, Chief Judge,

Honorable David T. Lewis, Honorable Jean S. Breitenstein,

Honorable Delmas C. Hill, Honorable Oliver Seth and

Honorable John J. Hickey, Circuit Judges.

This cause came on to be heard on the petition of ap

pellants for a rehearing en banc herein and was submitted

to the court.

On consideration whereof, it is ordered by the court

that the said petition be and the same is hereby denied.

Order denying petition for rehearing

Forty-Seventh Day, January Term, Wednesday, March

15th, 1967.

[ A P P E N D I X ]

Before Honorable David T. Lewis, Honorable Jean S.

Breitenstein and Honorable Delmas C. Hill, Circuit Judges.

This cause came on to be heard on the petition of ap

pellants for a rehearing herein and was submitted to the

court.

On consideration whereof, it is ordered by the court

that the said petition be and the same is hereby denied.

Breitenstein, D. J., dissents.

— x x m —

APPENDIX “C”

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED

(a) Constitution—Amendment XIV, Sec. 1