Davis v. Alabama Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

February 17, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Davis v. Alabama Brief for Appellants, 1967. 7791b84c-af9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1e6cfb3b-50f5-4abb-968d-8884ac321991/davis-v-alabama-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

■4fi.lL

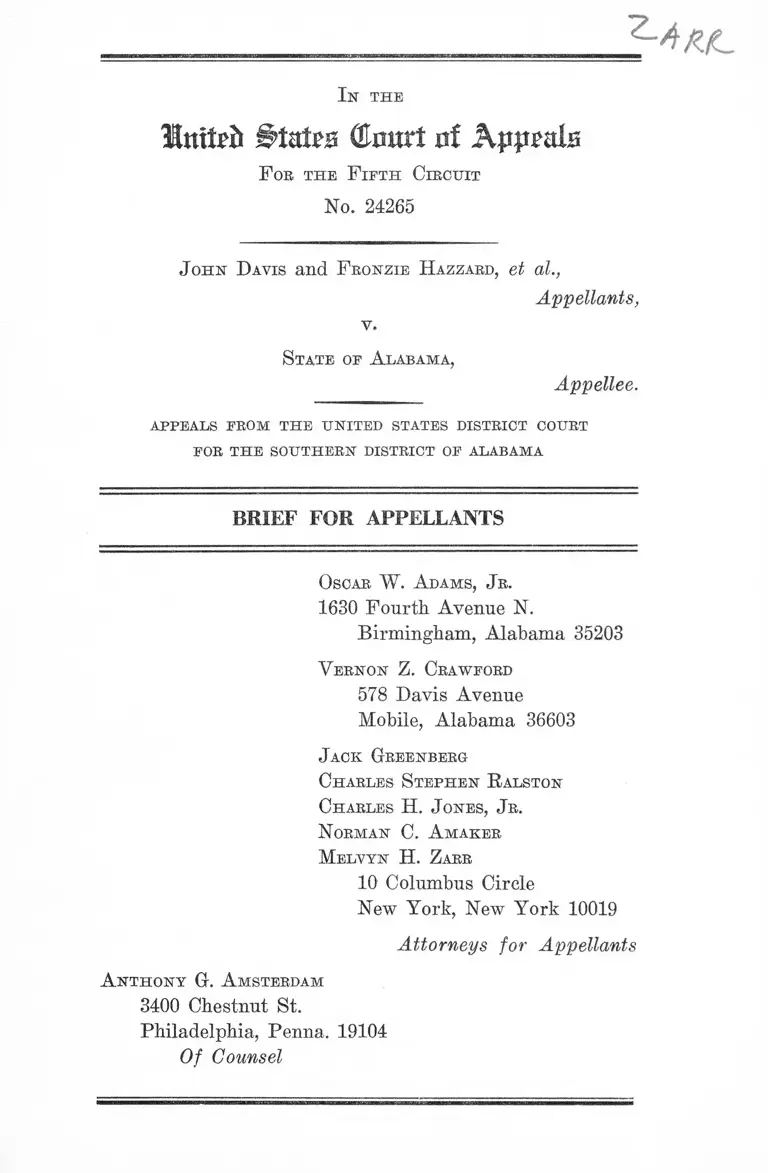

I n the

%niUb States GImtrt nt KppM z

F oe the F ifth Circuit

No. 24265

John Davis and F ronzie H azzabd, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

State of A labama,

Appellee.

APPEALS FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOE THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Oscar W . A dams, Jb.

1630 Fourth Avenue N.

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Y eenon Z. Crawford

578 Davis Avenue

Mobile, Alabama 36603

Jack Greenberg

Charles Stephen Ralston

Charles H. Jones, Jr.

Norman C. A maker

Melvyn H. Z aee

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

A nthony G. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut St.

Philadelphia, Penna. 19104

Of Counsel

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Statement of the Case ...................................................... 1

A. Fronzie Hazzard, et al. v. Alabama .................. - 1

B. John Davis v. State of Alabama ....................... 2

Specification of Error ...................................................... 3

Argument

28 TJ.S.C. §1443(1) Authorizes Federal Civil Rights

Removal Jurisdiction of State Criminal Prosecu

tions Brought Solely to Harass, Threaten or In

timidate Negroes for Exercising Their Right to

Vote or Aiding Others to Vote ..................-........... 4

A. The prosecutions in Hazzard v. Alabama are

removable by virtue of the federal voting acts 4

B. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 gave federal

courts sole jurisdiction of offenses such as are

charged in Hazzard ...... ...... ....................... -........ 8

C. In Davis v. Alabama, the Federal Voting Rights

Acts similarly grant immunity from prosecu

tion to those aiding others to register to vote .... 10

Conclusion .......................... ......................................... -.... 13

Certificate of Service ....................... -............................. 14

Statutory Appendix .......................................................... la

ftfSvs t A fers-WoULj

QhTECVn* fto 6P

ji/i'T ft h , S u pieptW'*fty

11

Table op Cases

page

City of Greenwood v. Peacock, 384 U.S. 808 (1966) ....4, 5,6,

10,11,12

Georgia v. Rachel, 384 U.S. 780 (1966) .......4,5,7,8,10,12

Harper v. Virginia Board of Elections, 383 U.S. 663

(1966) ..... .......................................................................... 7

In re Loney, 134 U.S. 372 (1890) .................................... 10

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964) .......................... 6

Sellers v. Trussed, 253 F.Supp. 915 (M.I). Ala. 1966) 9

United States v. Raines, 362 U.S. 17 (1960) ................... 7

United States v. Wood, 295 F.2d 772 (5th Cir. 1961),

cert, den., 369 U.S. 850 (1962) ...................................... 7,11

Yick Wo v. Hopldns, 118 U.S. 356 (1886) ....................... 6

Federal Statutes:

28 U.S.C. §1443 .................... 1,3,4,11,12

42 U.S.C. §1971 (a ) (1) .................................................... 5

42 U.S.C. §1971(b) ...................................................5,7,8,11

42 U.S.C. §19731. .............................................................. 8-9

42 U.S.C. §1973d ... ........................................................ 9

42 U.S.C. § 19731(h) ................ 5,6,7,8,10,11,12

42 U.S.C. §1973!(c)(1 ) .................................................... 6

42 U.S.C. §2000a (1964) .................................................. 4, 5

Ill

PAGE

42 TJ.S.C. §2000a-2 (1964) ............................................. 4,5,8

Civil Rights Act of 1957, Act of September 9, 1957,

Pub. L. 85-315, 71 Stat. 637 .......................................... 6

Civil Rights Act of 1960, Act of May 6, 1960, Pub. L.

86-449, 74 Stat. 90 .......................................................... 6

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Act of July 2, 1964, Pub. L.

88-352, 78 Stat. 241..........................................................6,11

Voting Rights Act of 1965, Act of August 6, 1965,

Pub. L. 89-110, 79 Stat. 437 ..........................1,2,4,6,8,11

In th e

Hmtm gtfata ©mtrt of

F ob the F ifth Circuit

No. 24265

John Davis and F ronzie Hazzard, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

State of A labama,

Appellee.

a p p e a l s f r o m t h e u n i t e d s t a t e s d is t r ic t c o u r t

FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Statement of the Case

This is an appeal from an order of the United States

District Court for the Southern District of Alabama re

manding in a single order and without a hearing two cases

removed to the federal court under 28 U.S.C. §1443, the

civil rights removal statute. The facts as alleged in the

removal petitions and which, for the purpose of the pres

ent appeal, must be taken as true, are as follows.

A. Fronzie Hazzard, et al. v. Alabama

In the Hazzard case, petitioners alleged that prior to the

passage of the Federal Voting Rights Act of 1965, they as

Negro citizens had been denied their rights to register to

vote and to vote. Subsequent to the passage of that act

2

and under its authority, numerous Negro citizens have

registered in that county, including most of the named peti

tioners (R. 17).

On February 23, 1966, with no prior warning, the twenty-

four petitioners were notified by the sheriff of Clarke

County that they were to appear in the Circuit Court on

February 25th to answer to indictments for perjury. The

ostensible basis for the perjury indictments was that the

petitioners had made misstatements of fact under oath on

their voter registration forms. These forms had been filled

out under the authority and in exercise of the rights granted

to petitioners under the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Petitioners alleged further that there were no bases in

fact for the perjury charges, but that the charges were

brought against them for the purpose of harassing and in

timidating them in the exercise of rights and privileges

granted by the Constitution and laws of the United States

with the intent and effect of discouraging themselves and

other Negro citizens from exercising their right to register

to vote and to vote (R. 17-18).

B. John Davis v. State of Alabama

In his petition, appellant Davis alleged that he is a Negro

citizen of the State of New Jersey and the United States

and is a voluntary worker with a civil rights organization

in a project whose purpose was to “ eliminate discrimina

tion with reference to registration and voting” in the State

of Alabama (R. 3). At the time of his arrest, petitioner

was at the Clarke County Courthouse assisting other per

sons in their efforts in becoming registered to vote. The

day of his arrest was the same day that the Federal Vot

ing Rights Act was passed by the Congress of the United

States.

3

A large number of persons were lined up at the regis

trar’s office to try to register to vote but a sheriff’s deputy

informed them, including the petitioner, that the voting

period or the period allocated to become registered to vote

had expired. When the petitioner sought clarification of

this order, he was charged under state law with disorderly

conduct and failure to obey the command of a law enforce

ment officer. »

The petition alleged that the charge against petitioner

had no basis in fact and the purpose and effect of the

prosecution was to punish him for the exercise of rights,

privileges, and immunities secured to him by the Federal

Constitution and laws, and to deter others from exercising

their right to register to vote in federal and state elec

tions free of racial discrimination (R. 4-5).

The removal petition in Hazzard was filed March 21,

1966, while the petition in Davis was filed on September 16,

1965. Subsequently, on October 4, 1966, the District Court

entered an order remanding both cases to the state courts

(R. 8). Timely notices of appeal were filed in both cases

(R. 9, 20). A motion for a stay of the remand order pend

ing appeal was filed in both cases but was denied by the

District Court (R. 10-14). In neither case has a trial date

been set as yet in the state courts.

Specification of Error

The Court below erred in holding that, given the allega

tions of the petitions for removal, these prosecutions were

not removable under 28 U.S.C. §1443 and in remanding

them to the state courts for trial.

4

ARGUMENT

28 U.S.C. §1443(1 ) Authorizes Federal Civil Rights

Removal Jurisdiction of State Criminal Prosecutions

Brought Solely to Harass, Threaten or Intimidate

Negroes for Exercising Their Right to Vote or Aiding

Others to Vote.

The central issue in these cases is whether they come

within the rule of Georgia v. Rachel, 384 U.S. 780 (1966) so

that removal is proper, or within that of City of Green

wood v. Peacock, 384 U.S. 808 (1966), which would defeat

removal jurisdiction. Appellants contend that Rachel gov

erns, in view both of the purpose and applicability of the

voting rights statutes in general and of the effect of the

Voting Rights Act of 1965 specifically.

A. The prosecutions in Hazsard v. Alabama are

removable by virtue of the federal voting acts.

In Georgia v. Rachel, 384 U.S. 780 (1966), the Supreme

Court of the United States sustained removal under 28

U.S.C. §1443(1) of state criminal trespass prosecutions

brought against Negroes for refusing to leave places of

public accommodations in which they were given a right of

service without racial discrimination by 42 U.S.C. §2000a

(1964). 42 U.S.C. §2000a(a) (set forth in the statutory

appendix, infra, pp. 2a-3a), was read as giving persons

seeking restaurant service a right to insist upon such ser

vice without discrimination, and 42 U.S.C. §2000a-2 (1964)

(set forth, infra, p. 3a), was read as giving a con

comitant right not to be prosecuted for that insistence.

In City of Greenwood v. Peacock, 384 U.S. 808 (1966), on

the other hand, the Supreme Court disallowed removal of

prosecutions against civil rights demonstrators based upon

5

their conduct in protesting the denial to Negroes of rights

to register and vote given by 42 U.S.C. §1971(a)(l) (set

forth, infra, p. la ). Section 1971(a)(1) was read as not

extending to persons a specific statutory right to protest

racial discrimination in voting registration, as distin

guished from the right to register to vote without racial

discrimination. Thus, in Peacock, the question was neither

raised nor decided whether 42 U.S.C. §§1971 (b) and

1973i(b) (set forth, infra, p. 2a), which protect those

persons directly engaged in the exercise of voting rights

in the same way as §2000a protects those engaged in sit-ins,

resulted in a right to remove state prosecutions designed

to intimidate and coerce persons for protected activities.

Appellants thus contend that the proper distinction be

tween Rachel and Peacock is the presence in the former

and absence in the latter of a federal statute with language

granting the specific right exercised together with a protec

tion against harassment, intimidation, coercion, etc., be

cause of an exercise or attempted exercise of that right.

The only other possible distinction between Rachel and

Peacock—namely, that §2000a-2 includes the word “ punish”

together with “ intimidate, threaten or coerce” within its

prohibition, while §§1971 (b) and 1973i(b) do not—is so

palpably insubstantial as to trivialize the significance of

these important pieces of federal civil rights legislation

and to reduce Rachel to trifling and rationally unsup-

portable dimensions. Yet, only this second and wholly im

permissible distinction will support the decision below re-

. manding appellants’ cases to state court. Appellants in

Hazzard, unlike the demonstrators in Peacock, were di

rectly engaged in the process of being registered to vote

and the conduct for which they are prosecuted comes di

rectly within the language of §1973i(b), viz., “voting or at-

6

tempting to vote.” 1 Thus, one of the “ specific provisions

of a federal pre-emptive civil rights law”— §1973i(b)—

“ confers immunity from state prosecution” upon appel

lants’ conduct (Peacock, supra, at 826, 827).

This Court must uphold federal civil rights removal ju

risdiction here unless it decides that Congress has deter

mined that voting rights are less worthy or needful of fed

eral protection than the right to equal public accommoda

tions, or unless it decides that Congress has failed to pro

tect voting rights by similarly “ specific provisions of a

federal pre-emptive civil rights law” (Peacock, supra, at

826).

Neither Congress nor the Supreme Court has relegated

voting rights to such a subordinate position. In the Civil

Rights Acts of 1957,2 I960,3 1964,4 and 1965,5 Congress has

enacted a comprehensive scheme for the protection of

voting rights, a legislative scheme certainly no less pro

tective than Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Anal

ysis of this scheme renders it highly unlikely that Congress

intended to place voting rights on a lower plane of federal

protection than the right to equal public accommodations.

And the Supreme Court has long recognized that the right

to vote is a fundamental right, “because preservative of

all rights” (Yick Wo v. Ilopkins, 118 U.S. 356, 370 (1886)).

In Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 561-62 (1964), the Court

said:

Undoubtedly, the right of suffrage is a fundamental

matter in a free and democratic society. Especially

1 42 U.S.C. §19731 (c) (1) defines “vote” or “voting” as including regis

tering to vote.

2 Act of September 9, 1957, Pub. L. 85-315, 71 Stat. 637.

8 Act o f May 6, 1960, Pub. L. 86-449, 74 Stat. 90.

4 Act of July 2, 1964, Pub. L. 88-352, 78 Stat. 241.

5 Act of August 6, 1965, Pub. L. 89-110, 79 Stat. 437.

7

since the right to exercise the franchise in a free and

unimpaired manner is preservative of other basic civil

and political rights, any alleged infringement of the

right of citizens to vote must be carefully and meticu

lously scrutinized.6

The language and intent of federal voting legislation en

able appellants and others subjected to prosecutions which

repress Negro voting activity to meet the test of removal

announced in Rachel. Section 1971(b) provides an ample \

declaration of Congressional intent to immunize from state

prosecution a person against whom state criminal charges

are brought with the sole purpose and effect of harassing

and intimidating him and other Negroes and punishing

them for, and deterring them from, exercising their right

to vote. This Court has so. held, and its reasoning and j

authority are persuasive./Cp”' United Siate~s~v. Wood, 29b

F.2d 772 (5th Cir. 1961), ttrt. den., 369 U.S. 850 (1962).

Section 1971(b), as a matter of language, is broad enough

to cover the case of official intimidation through abuse of

the state criminal process; and its legislative history can

vassed in Wood, 295 F.2d at 781-82, compels the conclu

sion “that Congress contemplated just such activity as is

here alleged—where the state criminal processes are used

as instruments for the deprivation of constitutional rights”

(295 F.2d 781).

Section 1973i(b) is of particular significance here for

two reasons. First, it has signified Congressional accept

ance of the Wood construction of §1971 (b) in that there

is now specifically proscribed any “ attempt to intimidate,

threaten or coerce any person for voting or attempting to

vote.” Second, it has retained the “ intimidate, threaten or

6 § 0e also, Harper v. Virginia Board of Elections, 383 U.S. 663, 667-68

(1966); United States v. Baines, 362 U.S. 17, 27 (1960).

8

coerce” formula of §1971 (b), apparently deeming it suffi

cient to cover the case of official intimidation through

harassment prosecutions— a case undoubtedly recognized

by the 89th Congress as an important means of repression

of persons aiding other persons to register to vote. Thus

it can be seen that there is no magic to the language “ pun

ish or attempt to punish” of §2000a-2 which qualifies it

alone to combat harassment prosecutions violative of im

portant federal rights.

To recapitulate, appellants contend that: (1) when they

registered to vote they exercised rights specifically granted

under federal statutes that provide for equal civil rights;

(2) the statutes, 42 U.S.C. §§1971 and 1973i, further pro

vide that they could not be intimidated or threatened be

cause they exercised those rights; and (3) therefore, just

as in Rachel, removal of their prosecutions to federal dis

trict court is essential to give the full protection afforded

by the statutes. O'

« 'W to

B. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 gave federal courts . .

sole jurisdiction of offenses such as are charged in

Haszard.

f 6 W* Appellants further argue that the overall statutory

Cyyf}*4* scheme of the Voting-Rights Act of 1965 establishes the

jurisdiction of the 'Tederal-'Courts over the offenses

» charged. The operation of the Act and its effect on the

. present prosecutions can be best understood by outlining

./> chronologically the events relevant to this action.

^ (M Prior to August, 1965, the registrars in Clarke County,

j . Alabama, operated under state lâ v. That is, they enforced

state statutory provisions relating to the registering of

voters and imposed state qualifications upon prospective

\ registrants. On August 6, 1965, the Voting Rights Act of

1965 was signed by the President. In Section 4 (42 U.S.C.

9

§1973b) of the Act, the Attorney General of the United

States was given the power to determine, according to a

formula, that tests or devices had been used in a state to

restrict the right of persons to vote because of race. Upon

his making such a determination, the use of any test (in

cluding a literacy test or other requirements such as had

been in force in the State of Alabama) in the state or po

litical subdivision was no longer permissible.

On August 7, 1965, the Attorney General made the re

quired determination with regard to the entire State of

Alabama, including Clarke County.7 Under the statute, he

had two options. He could request the Civil Service Com

mission to appoint federal examiners to go into some or

all counties in the state and to themselves register voters

for both federal and state elections (42 U.S.C. §1973d). In

the alternative, he could decide that within a particular

subdivision state registrars were making bona fide efforts

to register voters free of racial discrimination. In the case

of Alabama, federal examiners were sent into certain se

lected counties; in most counties, including Clarke County,

reliance was placed on existing state registrars. In either

case, however, the result was the same: prior requirements

of Alabama law were no longer in effect; literacy tests,

voucher requirements, etc., no longer were applicable;

rather, only such standards as were permitted under fed

eral law were imposed. In other words, the state registrars

were acting in the capacity of quasi-federal officers, doing

the same thing federal examiners would be doing, i.e., en

forcing provisions of federal law.

Thus, to permit removal in the present case in no manner

enlarges federal at the expense of state trial jurisdiction.

Just as the state courts would clearly lack jurisdiction over

7 See, Sellers v. Truss ell, 253 F. Supp. 915, 917 (M.D. Ala. 1966).

10

the offense charged against appellants-petitioners if they

had registered with federal examiners, so they lack juris

diction when the alleged offense is charged to have taken

place before state officials enforcing federal law. See, In re

Loney, 134 U.S. 372 (1890). In Loney, the Supreme Court

held that to allow the state to prosecute a person for per

jury because of testimony given before a state notary pub

lic for use in a trial in federal court could effectively

hamper the administration of an important federal opera

tion. Similarly, the state may not be allowed to interfere

with the enforcement of federal voting rights and the reg

istration of voters under federal statutory standards by a

criminal prosecution merely because the official acting pur

suant to federal law holds a state rather than a federal

position.

For these reasons, just as in Loney, the federal courts

have full power here to intervene, whether by removal or

otherwise, and exercise their proper jurisdiction over the

alleged offenses.

C. In Davis v. Alabama, the Federal Voting Rights Acts

similarly grant immunity from prosecution to those

aiding others to register to vote.

It has been argued above that the appellants in Haszard

are entitled to the removal of their prosecutions under the

rule of Georgia v. Rachel, since their conduct is specifically

protected by a federal statute providing for equal civil

rights. Their case was contrasted with that of the respon

dents in City of Greenwood v. Peacock, since no statute

grants the right to demonstrate in support of equal voting

rights. Just as the appellants in Haszard are protected for

the act of registering to vote, so appellant Davis is pro

tected in the act of directly aiding persons to vote or at

tempting to vote by 42 U.S.C. §19731 (b ).

11

The importance to adequate federal protection of voting

rights of protection and insulation of persons aiding others

to register was recognized by this Court in United States

v. Wood, 295 F.2d 772 (5th Cir. 1961). In Wood, the court

ordered a federal injunction against the state prosecution

of John Hardy, a Negro voter registration worker in

Walthall County, Mississippi, for peacefully attempting to

aid and encourage Negro citizens to attempt to register to

vote. Hardy had been arrested, without cause, for breach

of the peace. The court held that the prosecution of Hardy,

regardless of its outcome, would effectively intimidate Ne

groes in the exercise of their right to vote in violation of

§1971(b). 42 U.S.C. §1973i(b) thus in effect accepted and

codified the holding of Wood by prohibiting any “attempt

to intimidate, threaten or coerce any person for urging or

aiding any person to vote or attempt to vote.” Thus the

section sets to rest whatever doubt §1971 (b) may have left

that appellant Davis merits the protection of federal vot

ing legislation in aiding others to register to vote.

Again, the distinction between this case and Peacock lies

in the fact that appellant was directly involved in the vot

ing registration process, whereas the demonstrators in the

latter case were only tangentially involved. The Supreme

Court in Peacock made it clear that it construed a “law

providing for . . . equal civil rights” within the meaning of

28 U.S.C. §1443, as excluding the First Amendment rights

protected by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment. On the other hand, the phrase does include

the Equal Protection Clause, the Fifteenth Amendment,

42 U.S.C. §1971, the Civil Eights Act of 1964, and the Vot-

—... ing Rights Act of 1965.

C' ̂ .... -"In Peacock, the only claim available to the demonstrators

IfdffbD ! was the claim mot that they were being prosecuted for pro

tected acts, but that their prosecutions were harassing de-

® I * * > h i j //iV a

12

vices indirectly aimed at Negro voting activity. Therefore,

the Supreme Court held, there was no establishment of a

denial of the equal rights of the demonstrators themselves

by their prosecution in the state courts.

Appellant Davis, on the other hand, as in the case of

the appellants in Ilazzard, is being prosecuted for conduct

which is itself directly protected by the “ aiding” provision

of the voting rights statutes, and the “aiding” provision is

part of a section prohibiting all forms of intimidation, 42

U.S.C. §1973i(b). Where prosecution is based on conduct

thus directly protected by such a federal law protecting

equal rights, the prosecution necessarily denies the defend

ant his equal federal rights within the meaning of 28 U.S.C.

§1443(1), as the Supreme Court held in Georgia v. Rachel.

In conclusion, to permit appellants to prove in a federal

evidentiary hearing that the state prosecutions against

them are nothing more than an attempt to stifle the exer

cise of the right to vote by Negroes in Clarke County,

Alabama will not “work a wholesale dislocation of the his

toric relationship between the state and federal courts in

the administration of the criminal law” (Peacock, supra,

at 831). Rather, it will vindicate respect for that law by

assuring that it will not be used to interfere with specific

rights declared by Congress to be essential for the

achievement of equal civil rights.

13

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the order of the District

Court remanding appellants’ cases should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

Oscar W. A dams, Jr.

1630 Fourth Avenue N.

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

V ernon Z. Crawford

578 Davis Avenue

Mobile, Alabama 36603

Jack Greenberg

Charles Stephen Ralston

Charles H. Jones, Jr.

Norman C. A maker

Melvyn H. Zarr

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

A nthony G. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut St.

Philadelphia, Penna. 19104

Of Counsel

14

Certificate of Service

I hereby certify that I have served copies of appellants’

Brief on appellee by sending copies to Hon. Lee B. W il

liams, County Solicitor of Clarke County, Clarke County

Courthouse, Grove Hill, Alabama, and Hon. J. Massey

Edgar, District Attorney, Butler, Alabama, by United

States mail, postage prepaid.

Done this 17th day of February, 1967.

Attorney for Appellants

Statutory Appendix

1. 28 U. S. C. §1443(1) (1964):

§1443. Civil rights cases

Any of the following civil actions or criminal prosecu

tions, commenced in a State Court may be removed

by the defendant to the district court of the United

States for the district and division embracing the place

wherein it is pending:

(1) Against any person who is denied or cannot

enforce in the courts of such State a right under any

law providing for the equal civil rights of citizens

of the United States, or of all persons within the juris

diction thereof; . . .

2. 42 U. S. C. §1971(a) (1) (1964) (R. S. §2004 (1875) :

§1971 . . .

(a) (1) All citizens of the United States who are

otherwise qualified by law to vote at any election by

the people in any State, Territory, district, county,

city, parish, township, school district, municipality, or

other territorial subdivision, shall be entitled and al

lowed to vote at all such elections, without distinction of

race, color, or previous condition of servitude; any

constitution, law, custom, usage, or regulation of any

State or Territory, or by or under its authority, to the

contrary notwithstanding.

3. 42 U. S. C. §1971 (b) (1964) (Sec. 131 of the Civil

Rights Act of 1957, 71 Stat. 637):

§1971 . . . (b) Intimidation, threats, or coercion

No person, whether acting under color of law or

otherwise, shall intimidate, threaten, coerce, or at-

2a

tempt to intimidate, threaten, or coerce any other per

son for the purpose of interfering with the right of

such other person to vote or to vote as he may choose,

or of causing such other person to vote for, or not to

vote for, any candidate for the office of President, Vice

President, presidential elector, Member of the Senate,

or Member of the House of Representatives, Delegates

or Commissioners from the Territories or possessions,

at any general, special or primary election held solely

or in part for the purpose of selecting or electing any

such candidate.

4. 42 U. S. C. §1973 i (b) (Supp. I, 1965) (Sec. 11(b) of

the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 79 Stat. 443):

§1973 i . .. (b) Intimidation, threats, or coercion

No person, whether acting under color of law or

otherwise, shall intimidate, threaten, or coerce, or at

tempt to intimidate, threaten, or coerce any person

for voting or attempting to vote, or intimidate,

threaten, or coerce, or attempt to intimidate, threaten,

or coerce any person for urging or aiding anv person

to vote or attempt to vote, or intimidate, threaten, or

coerce any person for exercising any powers or duties

under section 1973a(a), 1973d, 1973f, 1973g, 1973h, or

1973j(e) of this title.

5. 42 U. S. C. §2000a (a) (1964) (Sec. 201(a) of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, 78 Stat. 243):

§2000a. Prohibition against discrimination or segrega

tion in places of public accommodation—Equal

access

(a) All persons shall be entitled to the full and

equal enjoyment of the goods, services, facilities,

privileges, advantages, and accommodations of any

3a

place of public accommodation, as defined in this sec

tion, without discrimination or segregation on the

ground of race, color, religion, or national origin.

6. 42 U. S. C. §2000a-2 (1964) (Sec. 203 of the Civil

Bights Act of 1964, 78 Stat. 244):

§2000a-2. Prohibition against deprivation of, inter

ference with, and punishment for exercising

rights and privileges secured by section

2000a or 2000a-l of this title

No person shall (a) withhold, deny, or attempt to

withhold or deny, or deprive or attempt to deprive, any

person of any right or privilege secured by section

2000a or 2000a-l of this title, or (b) intimidate, threaten,

or coerce, or attempt to intimidate, threaten, or coerce

any person with the purpose of interfering with any

right or privilege secured by section 2000a or 2000a-l

of this title, or (c) punish or attempt to punish any

person for exercising or attempting to exercise any

right or privilege secured by section 2000a or 2000a-l

of this title.

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. 219