Pleadings Hardback Index #3

Public Court Documents

April 3, 1998 - June 22, 1998

2 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Cromartie Hardbacks. Pleadings Hardback Index #3, 1998. 0a0023b5-e30e-f011-9989-7c1e5267c7b6. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1e73089c-5fb5-41ad-ac83-667d24d596fb/pleadings-hardback-index-3. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Copied!

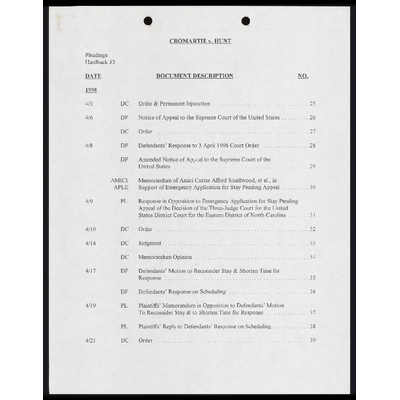

CROMARTIE v. HUNT

Pleadings

Hardback #3

DATE DOCUMENT DESCRIPTION

1998

Defendants’ Response to 3 April 1998 Court Order

Amended Notice of Appeal to the Supreme Court of the

United States

Memorandum of Amici Curiae Alfred Smallwood, et al., in

Support of Emergency Application for Stay Pending Appeal

Response in Opposition to Emergency Application for Stay Pending

Appeal of the Decision of the Three-Judge Court for the United

States District Court for the Eastern District of North Carolina

Judgment

Memorandum Opinion

Defendants’ Motion to Reconsider Stay & Shorten Time for

Response

Defendants’ Response on Scheduling

Plaintiffs’ Memorandum in Opposition to Defendants’ Motion

To Reconsider Stay & to Shorten Time for Response

Plaintiffs’ Reply to Defendants’ Response on Scheduling

DC

5/27 APLT

PL

6/22

Application for Extension of time to File Jurisdictional

Statement

Opposition & Objections to the Revised 1998 Redistricting

Plan

United States Motion & Memorandum for Leave to File Brief

as Amicus Curiae