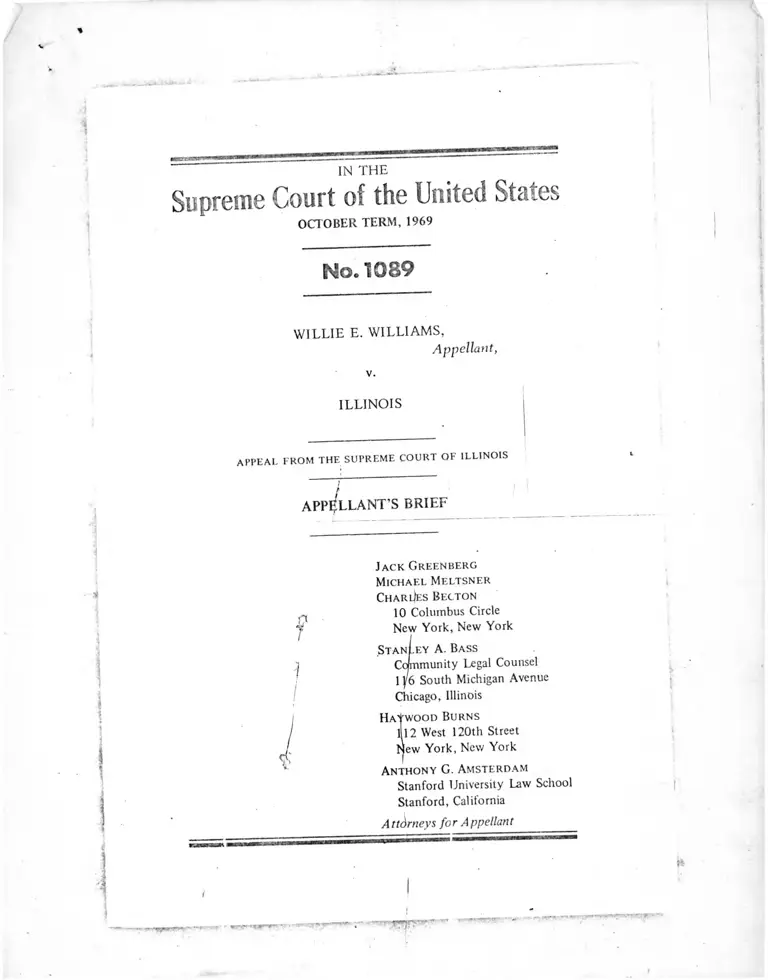

Williams v. Illinois Appellants Brief

Public Court Documents

October 6, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Williams v. Illinois Appellants Brief, 1969. ae11404e-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1e8b3455-e305-43b6-a55f-c34560bdf9b8/williams-v-illinois-appellants-brief. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1969

Mo. 1089

WILLIE E. WILLIAMS,

Appellant,

v.

ILLINOIS

APPEAL FROM THE SUPREME COURT O F ILLINOIS

f

APPELLANT’S BRIEF

f

jI

J ack Greenberg

Michael Meltsner

CharlIes Becton

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

St a nLey A. Bass

Community Legal Counsel

1 p South Michigan Avenue

Chicago, Illinois

HaTwood Burns

i l l2 West 120th Street

New York, New York

Anthony G. Amsterdam

Stanford University Law School

Stanford, California

A ttorneys fo r Appellant

(i)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

OPINION BELOW..................................................................................... 1

JURISDICTION....................................................................................... 1

QUESTION PRESENTED....................................................................... 2

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY PROVISIONS

INVOLVED.......................................................................................... 2

STATEMENT ................................................................................. 6

ARGUMENT ........................................................... 11

Illinois Statutes Which Authorize a Pauper’s Imprison

ment in Excess of the Maximum Period Otherwise Set by

Law at the Rate of Five Dollars Per Day, Despite the Fact

That He is Willing and Able to Pay a Fine and Court Costs

if Given the Opportunity, Violate the Equal Protection

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment............................................ U

CONCLUSION.......................................................' ................................. 29

AUTHORITIES CITED

Cases: i 1 ;----- f

Alegata v. Commonwealth1, 353 Mass. 287, 231 N.E.2d 201

(1 9 6 7 )...................... - . L ------------------ --------------. ™ - 1 9

Anders v. California, 386 U.S. 738 ( 1 9 6 7 ) ...................................... 25

Anderson v. Ellington, 300 F.Supp. 789 (M.D- Tenn. 1969) . . . 23

Ariel v. Massachusetts,___ Mass.___ , 248 N.E.2d 496 (1969)

appeal dismissed, 24 L.Ed.2d 468 (1^70)-.................................... 17

Baker v. Binder, 37fhF.Supp. 658 (W.D.Ky. 1967) ...................... 19

Berkenfield v. Peopfe, 191 111. 272 (19Q1) ...................................... 12

Buck v. Alex, 350 111. 167, 182 N.E. 7^4 (1 9 3 2 ) ........................ . 22

Burns v. Ohio, 360'U.S. 252 (1959) ./............................................... 24

City of Chicago v. Morell, 247 111. 383, 93 N.E. 295

(1911) . . . . j ................................. f .....................• ........................ 23

Cox v. Rice, 375/111. 357, 31 N.E.2d V86 (1 9 4 7 ) ........................... 22

Douglas v. Calih. nia, 372 U.S. 353 (11962)......................... 24, 25, 26

Draper v. Washington, 372 U.S. 487 (1963)...................................... 24

Duncan v. Louisiana, 391 U.S. 145 (1 9 6 8 ) ..............1 ................../

Edwards v. California, 314 U.S. 160 ( 1 9 4 1 ) ................

Eskridge v. Washington State Board, 357 U.S. 214 (1958)...........

Ex Parte Jackson, 96 U.S. 727 (1 8 7 7 ) ..............................................

Fenster v. Learcy, 30 N.Y.2d 309 (1967)

Frank v. United States, 395 U.S. 147 (1969)

Gardner v. California, 393 U.S. 367 (1969)

Griffin v. Illinois, 351 U.S. 12 (1956)........................... 24, 25, 26,

Harper v. Virginia Board of Elections, 383 U.S. 663 (1965) , 25,

Hill v. Wampler, 298 U.S. 460 ( 1 9 3 6 ) ..............................................

Kennedy v. People, 122 111.649, 13 N.E. 213 (1 8 8 7 ) ...................

Kettles v. People, 221 111. 221, 77 N.E. 472 ( 1 9 0 6 ) ......................

Lane v. Brown, 372 U.S. 477 (1 9 6 3 ) ................ .....................

Lawyer Title of Phoenix v. Gerber, 44 111.2d 145, 254 N.E.

2d 461 (1969) ...............................................................

| ........ •* * ' *

Long v. District Court of Iowa, 385 U.S. 192 (1 9 6 6 ) ...................

Loving v. Virginia. 388 U.S. 1 (1967) ...................................... 25,

McDonald v. Board\of Election Commissioners, 394 U.S.

802 (1 9 6 9 )...........\ .............................................................................

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184 (1 9 6 4 ) ...................... 23-24,

Maggio v. Zeitz, 333 U.S. 56 ( 1 9 4 8 ) .................................................

„ Martin v. Erwin (USDC WD La., January 25, 1968; Supple

mental Order, February 27, 1968, Civil No. 13084) . . . . . . .

Morris v. Schoonfeld, 301 F.Supp. 158 (D.Md. 1969), juris

dictional statement filed No. 782, October 28, 1969, 38

U.S.L. Week 3 1 6 2 ......................................................................... 28

North Carolina v. Pearce, 395 U.S. 711 ( 1 9 6 9 ) ................. 18, 28,

People v. Collins, 47 Misc.2d 210, 261 N.Y.S.2d 970

(Orange County Ct. 1 9 6 5 ) ...............................................................

People ex. rel. Herring v. Woods, 37 111.2d 435, 226 N!E.2d

594 (1 9 6 7 )........................... .................................................................

People v. Hedenberg, 21 111. App.2d ,504 (1959) ...................... 13,

People v. Herman, 245 111.App. 94 (1927)

14

19

24

24

19

14

25

31

26

24

23

23

24

22

25

26

25

26

18

20

-29

29

31

27

16

13

i

People v. Jaraslowski, 254 111. 299 (1 9 1 2 )................... | j2

People v. McMillan, 53 Misc. 2d 685, 279 N.Y.S.2d 941

(Orange County Court 1 9 6 7 ) ...................... ................................... 31

People v. Saffore, 18 N.Y.2d 271 N.Y.S.2d 972 218 NE

686 (1 9 6 6 )............................................................................................. 26

People v. Walker, 286 111. 541, 122 N.E. 92 (1 9 1 9 )........................... 23

People v. Zito, 237 III. 434 (1909).............................................. 13, 23

Petition of Blacklidge, 359 111. 482, 195 N.E. 3 (1 9 3 5 )................ 22

Re Gault, 387 U.S. 1 (1967) .........................• .................................... 14

Ricks v. District of Columbia, 414 F.2d 1097 (D C Cir

1 9 6 8 ) ..................................................................................19

Rinaldi v. Yeager, 384 U.S. 305 ( 1 9 6 6 ) ...................... . 21, 23, 25

Roberts v. Lavalle, 389 U.S. 40 (1967) ............................................ 25

Robinson v. California, 370 U.S. 660 (1962) ...................... ' 19

Sawyer v. District of Columbia, 238 A .2d 314 (DC App

1 9 6 8 ) ..............■.................................................................. ‘ . . . . . 27

Smith v. Bennett, 365 U.S. 708 ( 1 9 6 1 ) .................................... 25

Smith v. Hill, 385 F.Supp. 556 (E.D.N.Y. 1 9 6 8 ) .............................. 19

Strattman v. Studt,. 2d Ohio st. 2d ___ N E 2d

(1969) ................ \ .................................................. .’ . . . 7 7 ; . . . 23

Swenson v. Bosler, 386 U.S. 258 (1 9 6 7 )............................................ 25

United States ex rel. Privatera v. Kross, 239 F.Supp. 118

(S.D.N.Y. 1965) a ff’d 345 F.2d 533 (2nd Cir. 1965),

cert, denied, 382 U.S. 911 (1965) ...................................... ' 27, 28

Williams v. City of Oklahoma City, 395 l?.S. 458 (1 9 6 9 )................ 25

Wright v. Matthews, 209 Va. 246, 163 S.E.2d 158 (1968) ........... 23

Statutes:

28 U.S.C. § 1257(2)....................................................... j

29U.S.C . § 2 0 6 .............................. .. ...................................................... 19

Cal. Pen. Code Section 1205 .............................................. ' 20

Md. Ann. Code Art. 52 Sec. 18 . . , | ....................................... 20

Mass. Ann. Laws ch. 279, Section 1 A ( 1 9 5 6 ) ................................. 20

1

3

r/v>

Mich. Stats. Ann. Sec. 28.1075 (1 9 5 9 ) ................................... 20

Pa. Stat. Ann. Title 19, Section 953-56 ( 1 9 6 4 ) .............................. 20

S.C. Code Ann. Section 55-593 (1962) ...................... 20

Utah Code Ann. Section 77-53-17 (1 9 5 3 ) ......................... 20

Wash. Rev. Code Ann. Sec. 9.92.070 (1 9 6 1 ) ................................... 20

Wis. Stat. Section 57-04 (Supp. 1 9 6 5 ) ......................................... 20

Section 72 of the Illinois Civil Practice A c t .............. 8

Section 180-4 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (111 Rev

Stat. 1967 ch. 38) ................................... ' 5 -,0

Section 180-6 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (111 Rev

Stat. 1967. ch. 3 8 ) .................................................................... ' Passim

Section 1-7(k), Criminal Code of 1961 (111. Rev. Stat. 1967,

ch- 38‘) ....................................................................10, 11 , 12, 21, 22

111. Rev. Stat. 1967, ch. 38, par. 16-1........................................... 1 4 6

Model Penal Code, Proposed Official Draft, § 302.2 (1962) . . .!. 21

Other Authorities: ,

American Law Institute's Mo(3el Penal Code (Proposed Official

Draft, 1962) ................ j ...................................... j I 15

CCH Poverty Law Reporter1' 750 . . , _____ 20

Chicago Daily News, January 21, 1970 ......................................... 14

Chicago Daily News, January 20, 1969 ........................... 14

Chicago Sun Times, January 22, 1970 ................................... 14

Fines and Fining-An Evaluation, 101 li Pa ’ L Rev 1013

(1953) ................ n . .. ....................................................... ............... 20

Foote, The Coming Constitutional Crisis /in Bail, 113 U of

Penn. L.R. 1125 (1 9 6 5 )............... . . . ______ ’ ............. ’

Packer, The Limits of/the Criminal Sanction ................................... 15

Report of the President’s Commission on Crime in the District

of Columbia, ( 1 9 6 6 ) ........................... ...................... 30

The President s Commission on Law Enfo cement and Admin

istration of Justice-Task Force Report: The Courts 18 . . 16, 30

Report of the President’s Commission on Law Enforcement

and Administration of Ju stice .........................................

\

Report on Penal Institutions, Probation and Parole (1931) ........... 30

The Law of Criminal Correction, (1963) Rubin, Weihofen

and Rosenzweig ............................................................................... j5

Subin, Criminal Justice in a Metropolitan Court. ( 1 9 6 6 ) ............. 30

Sutherland and Cressey, Principles of Criminology, (5th Ed

1 9 5 5 ) ..................................................................................................... 15

12 Welfare Law Bulletin 14, April 1968 ........................................... 20

(v)

' i

f

I “T s r

IN TH E SUPREM E CO U R T OF TH E U N ITED ST A T E S

OCTOBER TERM, 1969

No. 1089

WILLIE E. WILLIAMS,

Appellant,-

v.

ILLINOIS

APPEAL FROM THE SUPREME COURT O F ILLINOIS

APPELLANT’S BRIEF

OPINION BELOW I

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Illinois affirming

denial of appellant’s motion to vacate that portion of his

sentence which directed that he stand committed to the

Cook County Jail in default of payment of S505 fine and

costs is reported at 41 111.2d 51 1, 244 N.E. 2d 197 (1969)

and is set forth in the Appendix at pp. 36-41. There was no

opinion in the court of first instance, the Fourth Municipal

District of the Circuit Court of Cook County, Illinois.

JURISDICTION

Jurisdiction of this Court is conferred pursuant to 28

UJLC. § 1257(2), this being an appeal which draws into

question the validity of statutes of the State of Illinois as

being repugnant to the Constitution of the United States,

their validity having been upheld in the cou 'ts of the state.

This Court noted probable jurisdiction on Jaiuary 19, 1970.

QUESTION PRESENTED

. Whelhc' Jllinoi statutes which authorize a pauper’s

imprisonment in excess of the maximum period otherwise

set by law, at the rate of five dollars per day for payment of

a fine and costs, despite the fact that he is willing and able

to pay them if given the opportunity, violate the Equal

ft-otrcXion Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment?

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY PROVISIONS

INVOLVED

Th«s case involves the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States.

This case invoke the following statutes of the State of

fllinor

1. Illinois Rev. Stat. 1967, ch. 38, par. 1-7

Judgment Sentence and Related Provisions

(a) Ojwmction and Sentence.

A person convicted of an offense shall be sentenced

as provided in this Section.

(b) Determination of Penalty.

Upon conviction, the court shall determine and

impose the penalty in the manner and subject to the

limitations imposed in this Section.

* * *

(d) Authorized Penalties.

Except as otherwise provided by law, a person

convicted of an oflense may be:

(1) Sentenced to death; or

(2) Sentenced to imprisonment as authorized by Sub

sections (e) and (f) of this Section; or

(3) Ordered to pay a fine authorized by Subsection

(i) of this Section; or

V .

t

(4) Placed on probation; or

(5) Ordered to pay a fine and placed on probation; or

(6) Sentenced to imprisonment and ordered to pay

a fine.

(e Penitentiary Sentences.

AJI sentences to the penitentiary shall be for an

indeterminate term. The court in imposing a sentence of

imprisonment in the penitentiary shall determine the mini

mum and maximum limits of imprisonment. The minimum

limit fixed by the court may be greater but shall not be

less than the minimum term provided by law for the offense

and the maximum limit fixed by the court may be less but

shall not be greater than the maximum term provided by law

for the offense.

(f) Sentences other than to Penitentiary.

All sentences of imprisonment other than to the

penitentiary shall be for a definite term which shall not

exceed one year.

(g) Mitigation and Aggravation.

For the Purpose of determining sentence to be

imposed, the court shall, after conviction, consider the

evidence, if any, received upon the trial and shall also hear

and receive evidence, if any, as to the moral character, life,

family, occupation and criminal record of the offender and

may consider such evidence in aggravation or mitigation of

the offense.

* * *

(j) Penalty Where Not Otherwise Provided.

The Court in imposing sentence upon an offender

convicted of an offense for which no penalty is otherwise

provided may sentence the offender to a term of imprison

ment not to exceed one year or a fine not to exceed $1,000,

or both.

4

(k) Working out Fines.

A judgment of a fine imposed upon an of.

be enforced in the same manner as a judgment

a civil action; provided, however, that in such

imposing the fine the court may further order

nonpayment of such fine, the offender may be u

until the fine is paid, or satisfied at the rate of S5.<

of imprisonment; provided, further, however, that r

shall be imprisoned under the first proviso here

longer period than 6 months.

(1) Place of Confinement.

When a statute authorizes imprisonment

violation but does not prescribe the

imprisonment, a sentence of more than

shall be to the penitentiary, and a senten

exceed one year shall be to a penal in.,

other than the penitentiary.

2. III. Rev. Stat., 1967, ch. 38, par. 18(F6

Discharge o f Pauper j

Whenever it shall be made satisfactorily to appear

court, after all legal means have been exhausted, t;

person who is confined in jail for any fine -or c

prosecution, for any criminal offense, hath no estate

with to pay such fine and costs, or costs only, it shah

duty of the said court to discharge sucfh person from,

imprisonment for sn h fine and costs, which discharg

operate as a complete release of such fine and costs:

vided, that nothing herein shall authorize any person

discharged from imprisonment before the expiration

time for which he may be sentenced to be imprison,

part of his punishment.

3. III. Rev. Stat. II967, ch. 38, par

Theft l

16-1:

A pe-son commits theft when he knowingly:

\

r may

ed in

ment

upon

oned

r day

rson

or a

' its

of

ear

t to

:ion

:he

ny

of

re

de

er

11

o-

•>e

e

us

5

(a) Obtains or exerts unauthorized control over property

jotihe owner; or y

(b) Obtains by deception control over property of the

owner; or J

(c) Obtains by threat control over property of the

owner; or J

tT,r,,tr01 0V£r St° ,en Pr°P6rty k"°wing the propen ,o have been stolen by another or under such

orcumwooes as w mid reasonably induce him to believe

tiie prop was Stolen, and

U ) intends to deprive the owner permanently of the

use or benefit of the property; or

vingly uses, conceals or abandons the prop-

** ' 1;: “uck a manner as to deprive the owner

permanently of such use or benefit; or

lie s , conceals, or abandons the property knowing

such use, concealment or abandonment probably

will deprive the owner permanently of such use

(2 )

(3)

or benefit.

Penalty

A person first convicted of theft of property not from

the person and not exceeding $150 in value shall be fined

other $ °° ° r 'mprisoned in a P^al institutionother than the penitentiary not to exceed one year, or both

hmPeerornaft0nViCted ° f SUCh 3 S6COnd ° r ^ se q u e n t time, or after a prior conviction of any type of theft shall

be imprisoned in the penitentiary from one to 5 years A

person convicted of theft of property from the person or

exceeding $150 m value shall be imprisoned in the peniten

tiary from one to 10 years.

4. III. Rev. Stat. 1967, ch. 38, par. 180-4

Judgment Hen on property, real and personal-Execution

The property, real and personal, of every person who shall

be convicted of any offense, shall be bonnd, and a lien is

hereby created on the property, both rea and personal of

6

every such offender, not exempt from execution or attach-

tnent, from the time of finding the indictment at least so

-far as will be sufficient to pay the fine and costs of prosecu-

fion. The clerk of the court in which the conviction is had

shall upon the expiration of thirty (30) days after judgment

is rendered issue an execution for any fine that remains

unpaid, and all costs of conviction remaining unpaid; in

which execution shall be stated the day on which the arrest

was made, or indictment found, as the case may be. The

execution may be directed to the proper officer of any

-county in this State. The otficer to whom such execution

is delivered shall levy the same upon all the estate, real

and personal, of the defendant (not exempt from execution )

possessed by him on the day of the arrest or finding the

indictment, as stated in the execution and any such property-

subsequently acquired; and the property so levied upon shall

be advertised and sold in the same manner as in civil leases

with the like rights to all parties that may be interested'

therein. It shall be no objection to the selling of any

property under such execution, that the body of the

defendant is in custody f)br the fine or costs, or both.

STATEMENT

On June 24, 1967, appellant, Willie E. Williams, was

arrested for the crime of theft of property not from the

person and not exceeding S1 50 in valtie, 111. Rev. Stat. 1967

ch. 38, par. 16-1, (A.A() and charged with having “knowingly

obtained unauthorized control over credit cards, checks and

papers ol the value of less than cine hundred and fifty

dollars, the property of Edna Whit net, intending to deprive

the said Edna Whitney permanently bf the use and benefits

of said property.” (Ibid).

august . ., ,, „w was utuu„ _ _ W1C

Court of Cook County at suburban!May wood, Illinois fc

arraignment; bail Aas set at S2,000 (A. 5,6). Unable to po

bail, appellant remained in custody. (A. 12). The cou

7

continued the case to August 16, 1967, and committed

Williams to the custody of-the sheriff. (A. 6). August 16,

1967, on motion of the State Attorney, the case was con

tinued to September 6, 1967 (A. 7).

September 6, 1967, appellant entered a plea of not guilty

and “waived” his right to trial by jury. (A.8) Williams was

at no time represented by counsel during the proceedings

in the trial court (A. 8, 13).1 After trial, the Honorable

Joseph R. Gill found appellant guilty as charged (A. 9) and

sentenced him to the maximum term of imprisonment for

a first offense authorized by Illinois law: one year in the

Cook County Jail (A.9). Judge Gill further sentenced

appellant:

. . . to pay the Clerk of this Court, to be by said

Clerk disposed of according to law, a fine in the

sum of FIVE HUNDRED DOLLARS ($500) and

also the costs of this suit taxed at FIVE DOLLARS

($5.00) and in default of payment of said fine, it is

ordered that said defendant, after the expiration of

said term of imprisonment, stand committed in said

County Jail until said fine and costs shall have been

paid or until said defendant shall have been dis

charged according to law. (Ibid.)2

Williams was tried in a suburban court where there is no regu

larly assigned public defender or official court reporter. Without a

transcript, it is impossible to determine aujthoritatively whether the

magistrate in this case advised Williams p f his right to appointed

counsel. Counsel for Appellant are informed, however, that the prac

tice in the Maywood court is that if a/ defendant requests an ap

pointed counsel, the case is transferred to the central court of the

District where there is a Public Defenderi regularly assigned one day

per week, but that a^criminal defendant is not otherwise apprised of

his right to counsel./ \

2Judge Gill thus -mposed the maximum term of imprisonment and

fine peimitted upon a first conviction o f the crime of theft of prop

erty no from the person and not exceeding $150 in value, 111. Rev.

Stat.1967 ch. 38, par. 16-1.

I !

I

8

of

t it filed a

1967 cli 3™ Mrl'itSn ? UlLC Act a,ld under 111 Rev. Slat,

court's order' of ^

* of ,,is one - -

S500 flue and S5 in costs (A. 12) Payment ot

In the petition, Williams affirmed under oath that he was

no estate*,n<fifnds 'or" valuabl''’*' ^ C° U" ,y J*“ a "d ,lad - Linas, oi valuable property whatsoever (A. 12);

that he was financially unable to obtain counsel at the

hiTrid,, ,o h'**1 and ” , ',eVer adViSed by I1,e trial court of ms right to have counsel assigned;

unable topay !hc T s l s Z T Z l,e was

apparent to ih, , , and costs <as should have been

the in"/ n “ C° llrt aS i,e had "O' been able to furnishthe 10/. deposit on his S2.000 bond which would l av.

attorney; mi”° is la“ > or to retain an

that he had been incarcerated since August 13 1 967 and

therefore incapable of earning a livelihood': '

that he remained on the date nf ti,Q ....

funds to pay the S 505 fine and costs; ?

lished in 1966 by^h^CenteTfor Studfe C° ° r C° Unty Jail was estab‘

sity o f Chicago Law School l h ' , 1? Cnminal Univer-

In recognition that the need of Drk 8rant fr0™ the Ford foundation,

matters extends far beyond^he LnvemTni01! I' 831 aSSfistance on civd

Civil Legal Aid Service has filpH .■ • a tyPes ° f civil cases, the

sough, other f° ' "abeaS “ H *

T h e r e * c r ir n ^ n a !" d e f e n ^ s e 0na,r*yPe^ a^ ^ ldÎ e<praaaa™ doc

lent a, being propedy wilhin lhe ™ W * -

"T’’"

i

i

1

j

1

and finally that “defendant will be able to get a job and

earn funds to pay the fine and costs if he is released from

jail upon expiration ot his one year sentence ” (A. 13)

At the November 29, 1 967, hearing on the petition, held

before Judge Gill, the judge who had sentenced appellant,

no court reporter was present.4 At no time subsequent to

the filing of the petition, however, did the state traverse

its factual allegations or offer evidence challenging the

allegations of the petition. (A. 25, 26). Appellant’s counsel

summarized the allegations of the petition and the. State’s

Attorney moved that it be denied. (Ibid). Judge Gill denied

the petition on its face:

. . .for the reason that petitioner was not legally

entitled at that time to the relief requested in the

petition, because he still has time to serve on his

jail sentence and when that sentence has been served

financial ability to pay a fine might not be the same

as it is of the date o f September 6, 1967” (Italicized

portion written into the bill of exceptions by Judge

Gill.) (A.26)

Notice of appeal to the Supreme Court of Illinois from

Judge Gill’s order denying appellant’s petition was filed on

November 30, 1967 (A. 16), and the appeal was argued

orally on May 16, 1968 (A.31) May..23, 1968, appellant

completed service ot his one year sentence, less time off for

good conduct and for time spent in custody prior to trial

and began to serve the period of incarceration required to

satisfy the $505 fine and costs, at the statutory rate of $5

per ay. (A.31). On May 28, 1968, the Supreme Court of

Illinois, on motion of appellant’s counsel, set bail for

appellant pending his appeal at $500. (A.35) The 10%

deposit ($50), $45 of which is refundable, was posted by

the Civil Legal Aid Service.

In accord with an order dated January 30, 1968, of a Justice of

e Supreme Court of Illinois, appellant constructed a bystander’s bill

of exceptions covering the proceedings o f November 29, 1967 with

out waiving his objections to the validity ano propriety o’f non

reported proceedings: (A.22-26). - F y non

"srrr-'r

i

10

Appellant argued before the Supreme Court of Illinois

that his imprisonment for default in payment of a fine and

costs, pursuant to 111. Rev. Stat. 1967, eh. 38, § 1-7 (k), and

his exclusion from coverage of 111. Rev. Stat. 1967, ch. 38,

§180-6 (which provides for discharge from imprisonment

under specified circumstances) rendered both statutes uncon

stitutional under the Fourteenth Amendment.

On January 29, 1969, the Illinois Supreme Court affirmed

the judgment of the lower court denying appellant’s peti

tion,5 and held that there is no denial of equal protection of

the laws when an indigent defendant is imprisoned to

satisfy payment of a fine and costs (A.37, 40).

Appellant filed timely notice of appeal to this Court on

February 11, 1969 (A.48). By an order of February 13,

1969, the Supreme Court of Illinois stayed its mandate

pending final disposition of the appeal (A.47). On January

19, 1970, the Court noted probable jurisdiction (A.49).

sThe Supreme Court of Illinois characterized the denial of relief

by the trial court as “because of its legal insufficiency.” (A.36). By

this holding, and by releasing appellant on bail subsequent to the

completion of one year in prison, the court appears to have rejected

any suggestion of an alternate holding by the trial court that the pe

tition was premature (A.26). The Supreme Court, of course, went

on to decide appellant’s constitutional claim on the merits.

/

ARGUMENT

Illinois Statutes Which Authorize a Pauper’s Im

prisonment in Excess of the Maximum Period

Otherwise Set by Law, at the Rate of Five Dollars

Per Day, Despite the Fact That He Is Willing and

Able To Pay a Fine and Costs if Given the

Opportunity, Violate the Equal Protection Clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment.

.Arter conviction for a petty theft, appellant Willie

Williams wsls sentenced to confinement in the Cook County

jail for the term of one year and to pay a fine of $500 and

costs taxed at $5 (A. 9). Should Williams default in pay

ment the trial court ordered that he “stand committed in

said County Jail until said fine and costs shall have been

paid or until said defendant shall have been discharged

according to law” (A. 9).6 Pursuant to § 1 -7 (k) of the

Criminal Code of 1961 (111. Rev. Stat. 1967, ch. 38),7 if

° the judgment further command that the Sheriff “take the body

of said defendant and the keeper of said jail is hereby commanded to

receive the body ot said defendant into Iris custody and confine said

body in said County Jail in sate and secure custody for and during

said term as aforesaid, and after the end of said term of imprison

ment, the keeper of said jail is hereby commanded to continue to

confine the body of said defendant in said County Jail in safe and

secure custody until said fine shall have been paid or until said de

fendant shall have been discharged according to law, and after the ex

piration of said fixed term of imprisonment as aforesaid, said defend

ant shall be thereafter discharged.”

“It is further ordered that execution issue herein against said de

fendant for the amount of said fine” (A.9, 10).

7This section provides, “Working out Fines. A judgment of a fine

imposed upon an offender may be enforced in the same manner as a

judgment entered in a civil action; Provided, however, that in such

judgment imposing the fine the court may further order that upon

non-payment of such fine, the offender may be imprisoned until the

fine is paid, or satisfied at the rate of $5.00 per day of imprison

ment, Provided, further, however, that no person shall be imprisoned

under the first proviso hereof for a longer period than 6 months.”

4

appellant did noi pay the fine of S 500 and costs of $5

they would be -satisfied at the rate of S5 per day of

imprisonment provided however, that no person “shall be

imprisoned. . .tor a longer period than 6 months.”

Williams alleged “under oath that he was indigent at all

stages of the proceedings, that he was without counsel or

lunds lure counsel at the trial and that he will be able to

get a .and earn funds to pay the fine and costs if he is

released from jail upon expiration of his one-year sentence”

b° th the tnal court and Supreme Court of

mens rei used to alter his commitment to jail in default of

the payment of the fine and costs.

It is plain from the opinion of the Supreme Court in

appellant s case, uind prior Illinois decisions, that the

Supreme- court of Illinois regards the incarceration of a

defendant who cannot pay a fine or costs as a punitive

exaction by the slate which is considered the equivalent of

the fine or costs and thus not an invidious classification

which violates the Equal Protection Clause.

12

In Berkenfield v. People, 191 111 ~>ii n o rm ->

f fa,»0'L a H e .

costs) under the predecessor % lf ° ° ^

out his fine at the rate of Si sn T -l, d required t0 work

- /o) and that otherwise the sentence nr ̂ 11 ’ at

would he catkfipH ■ • ce or imprisonment and finewuuiu ne satistied by imprisonment only.

In People v. Jaraslowski, 254 111 ?99 |H ) n i A„r .

found euilty of obtain,„g money „y fa|je <reten̂ t „ nHcedWlo

thafy miprisonmem and fined S500. The judgment order directed

z r x z s z i ? <z ~ d

455 of the Criminal Code, from working out his fine in the

house of correction, yet the mere fact that he , a pauner

“ ch r d e a s l - 0ney pay the »»• entitle L T tl,

Tf,-

13

c a t r ^ r T ■ ,haI lhe premise of lhe Illinois

M l L Z " ’"8 f appellan,'s c^ e - th a t giving a wealthy

man the choice of paying the $505 or serving 101 days is

k T T f ' r ° f requ,rm8 ,l,e P°°r man to serve 101 days-

penalty" T T° te SUre’ 3 fine may be a b"rdensomepe y specific cases. Depending on the rate at which

itjnay i e worked off”, there may even be times when it

LS d more onerous penalty than imprisonment. It would be

^ d a' r rea ,ty' h° WeVer’ to ^nore that the state has

« S L n t w m t,eavler burden on the poor in general, and

appellant Wiliams m particular, by attempting to equate a

choice of serving i0 l days in jail or paying a S505 fine with

the necessny Qf serving the prison sentence. The fact is

that the man without $505-although alleging that he can

J v l k d t r IZTZZtl" d k PP: 94(l927) ,he d' f'" d™ «■

prisonment and fined $ 1,000 plus c m T " ' Sen'Cn“ d “ 0"e S 'ar im'

Where a proper order is entered under Ŝ qi ■

ment of a fine in labor at ci cn j > requinng pay-

, .PHUIIM P

against ™ »b.ain=d

s

hided for violations of the penaU aL o n h V s f s k ^ l l 'n

e o i ^ ^ o f a ,2,1 APP 24 504' 510 <l959> “>= de-

him! T ta rS 'w "af no,

14

" " c c ' of1 m anda-

employment, loss of education-. ’ ^ °* P"y' '° SS of

normally dismal, if not mhum n • ° P P ° r t U n i t y a n d the

detention facilities-poor food a n d T ^ ’0"5 Sh° rt term

inadequate recreationai° an <j° otlicr^fadlitief' e V6fCr° ^ ’nŜ

mentary comfort and decency * C e ? eSSent,al rudi'

27 (1967), In short he i ln ^ ReGaulr- 3«7 U.S. 1

life worth living while the m T ^ h K O ^ ' t 6? ' ' 3'

a necessary inconvenience. As th,\ r ° V bl‘rdened vvith

United States, 395 US 14 7 is . ,n °Ur Sa,d 111 Frank >’■

course, a s ig n in g ,^ n f r .^ e L n t ' * • of

it IS certainly less onerous ■> r personal freedom, but

Cf D w iean » onerous a restraint than jail itself” '"

^ “7 V V- LoUlSutna'3 9 \ U.S. 145, 161-62 (1968)

punishments by V s ta ™ 'h a s ^ T " * ^ 6 labe,led crim'nal

criminal process to regard rh ° bserH of theto regard them as fungible. Thus, it is

condition, ancTf u lly T u p ^ r f t h e ^ T Iilinois f re a deplorable

that such facilities are “ ‘tHe lowestTorm0^ ——a-leading- Penologist-’

American scene.” ’ Foote The r a . °™ of social institution on the

113 U. o f Pa.-Rev. , & * ] Crisis in Bail*

Chicago Daily News reported critical findm ° ”,Janua^ 20- 1969 the

county jails financed by the For I F ^ t 8 ° f 3 survey o f ci ty and

Enforcement Com m ,Jon a n d I Z S ' T a"d ,ht '" » » »

Chicagoe Center for atujiesm Crimm , C > ,he U"Wersi,y o f

of criminologist Hans 'V. Mattick a”d 1 , 7 Ihe direction of

reported by the ,Ve».s7 , he survey f”n„d7 h" T . .R1° nald P' Sweet, As

Jonty of all Illinois jail inmates L * t the overwhelming ma-

weehs later inspectors T r Z ^ id,e "" Three

found gang rule, racill segregation and u f f reaU ° f Prisons

Chicago House of Correction Chicago D t OF COndltIons” in the

Chicago Sun Times, Jan. 22, 1970. 8 ° * N eW ’ Jan‘ 21 ’ 1970;

T I r ,e p m L T „ qt ^ b^ ; X ' l f hiS * * ■ * » - o'ake

abiding persons, mat-«tain reasonable h 7 assoaate on,y with law

job changes to his probation officer and n n tT * T ' lady’ report a"

net without permission, 395 U.S. at 15] n 6 ^ probation dis-

generally considered that imposition of the fine by a trial

court is tantamount to a declaration that neither the safety

of the community nor the welfare of the (petitioner)

required) (his) imprisonment. . (Sutherland and Cressey

Principles of Criminology, p.277 (5th Ed. 1955)." Sim

ilarly, the American Bar Association’s Committee on

Sentencing Standards regards imposition of a fine “an initial

determination that jail—or at least the time which is due to

non-payment—is unnecessary in terms of the protection of

the public, the gravity of the offense, and other factors

which normally determine the need for incarceration ”

(Tentative Draft, 1967, p. 121.) See also Rubin, Weihofen

and Rosenzweig, T he L aw o f C riminal Co r r ec t io n , 254

(1963). Indeed, one of our most thoughtful observers of

sentencing has argued that the criminal process should be

invoked only by means of “the crude benchmark of depri

vation of liberty that ■ inheres in an actual or potential

sentence ot imprisonment” Packer, The Limits o f the

Criminal Sanction 273?2

15

Tins conclusion is also supported by the American Law Insti-

^rr S ^ de' Penal Code Provisions on Sentencing, § 7.02 (Proposed

Official Draft, 1962), which provides that a fine should be imposed

when the court is “of the opinion that die fine alone suffices for

protection of the public.”

“Th'2Pr0feSSOr, PaCkeT'S V‘eW 'S Premised in Pa" on the notion that

lnd‘Scrimlnate we are treat ng conduct as criminal, the

ktss stigma resides in the mere fact that J man has been convicted of

something called a d im e” and he concludes that:

If the most that we are prepared to exact in the great ma-

J' y occurrences of a particular form of reprehended

conduct is the payment of mortey into the public treasury

i^vokine f i i0t imP° f ° n ° UrSe VeS the manifold burdens of

T k f ™ nal san^ o n . Whether the subject happens

of ho,Kin ̂ °HfenSeS’ ° r huntinS out of season, or breaches of housmg. codes, or any one of the thousands of minor

sancHo°ry °J sumptuary offenses with which the criminal

oueh I" 3nd f pr0c ŝses are Presently encumbered we

ought to purge from the criminal calendar all offenses that

sanctions.” S6n0Usly enou8h to Pu dsh by real criminal

*

16

It is beyond doubt that those concerned with administra-

dW erem 'o rT 3' l"*’— ̂ ^ as a sanc(io" of adifferent order of cnmtnal penalty, responding often to a

If this™ 0bjeC,1Ve of the cn" lin;i1 taw. than imprisonment

men is m . O iai'S WOl"d be “ -P*. for imprison-'

“ f“f more cost|y '° soci« y , not to mention burden

some to the average criminal defendant, than a fine. See

lump<hoth/fY,<" />',7 ' ^ ’ l a APP' 2d 504 <l959)- Thu> to

of “„,mkh "opttsonment together under the label

of punishment does not imply that each results the

r ; o n T w T f A' * ReP° rt ° f the President's Commis- sion on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice

observed in 1967: “Two unfortunate characteristics of

mg practices in many lower courts are the routine

~ °n the/ reat maj°nty ° f ™ ^eL anan ts and petty offenders and the ‘routine imprisonment of

defenders who default in paying fines. These practices

result in unequal punishment o f offenders and in the needless

Z ~ ntrl r y PerSOnS because o f tb“ “

supplied)^' t f b , KeP°r,: The Couns 18■ (emphasis supplied) The Report recommends that society employ

sui able a lte rna te punishments so that those unable to pay

means° PUniSh6d m°re SCVerely than those of greater

t^ US jhin°is ^as sanctioned a penological regime which

f u n d s ' his o ' ■ 0“ impnSOnment for a"y Person with

Ws ca e h' JfPOSSeSS1° n’ re^ardless ^ the circumstances of

his case, but permits a greater punishm ent-because 101

days in jail is far more onerous a punishment than the choice

of paying the fine of S505 or serving the sentence-over the

defined maximum state interest in incarceration, in the case

o the poor. What slim justification Illinois offers for

«ngl ng out the po° r for extended incarceration

to a contention that because [indigency] precludes the state

rom collecting the fine forthwith it must be entitled to

imprisonment forthwith. Even assuming arguendo that

some necessity” of providing punishment for those who

i

17

cannot pay a fine would excu

penalty, the Illinois practice do-.

Amendment because the state L

devices tar less subversive of eqm.

ment. In this case appellant aft:

state did not dispute, that if pern,

and would obtain work and pay the

could have avoided the extended

S505 before his one year prison s

sibility, as William’s alleged in this

man who does not have S505 is im

incarcerated.

Thus, even the state’s interest i:;

advanced by extended incarcera;

defendant willing and able to p

opportunity, as to whom no sue

conduct is raised, cf. Ariel r. Masse

248 N.E. 2d 496 (1969) appeal dis:

(1970),11 the state is simply choosu.

13In Ariel the appellant was found guii

violations. A municipal court judge fined

• p aint in amounts ranging from S 10 to S

Upon finding the appellant too poor to p,:

judge sentenced the appellant to jail The

order of commitment for refusing to sue

sentence was that “the Court finds the J

On appeal, the Supreme Judicial Court of

the municipal court judge submit “a comp

of the court in addition to inability to'

based its refusal to suspend execution of the

pal court s additional findings, contained a ,

prior defauh5 jn appearances on certain mot

a finding that this “contumacious conduct"

to time for payment. Although the Supre

that Massachusetts Law contemplates that a

to jail a defendant unable to pay a fine ini me

der the desirability of extracting the fine ove.

than automatically increasing the severity of

nevertheless, to rest its decision affirming the"

cipal Court on these additional findings o f pro

^position of a greater

satisfy the Fourteenth

ailable to it collection

Section than imprison-

ively alleged, and the

J his liberty he could

Although appellant

ence if he raised the

-nee expired, the pos-

is an illusion. A

\’e of earning it while

acting the fine is not

In the case of a

e fine if given the

n of contumacious

its, __Mass.____ ,

J. 24 L. Ed. 2d 468

extend incarcera-

seven motor vehicle

ypellant on each com-

or a total of $510.

fine forthwith, the

“ason recited on the

■be execution of the

nt unable to pay.”

nusetts ordered that

-ital of any findings

.■n which the court

ence. The munici-

■ion of appellant’s

ricle violations and

ot entitle appellant

dicial Court noted

before committing

-iy, at least consi-

-riod of time rather

1 ment, it elected,

lent of the Muni-

mty of default.

18

tion without allowing a poor defendant the opportunity to

satisfy the state’s exaction. As Mr. Justice Jackson said in

Maggio v. Zeitz, 333 U.S. 56, 64 (1948) . .no such acts,

however reprehensible, warrant issuance of an order which

creates a duty impossible of performance, so that punish

ment can follow.” Illinois is free to set the penalty for

petty theft at one year and 101 days but once the maximum

imprisonment which satisfies the interests of the state is

defined at one year, making extended imprisonment appli

cable to those who could satisfy the fine if given the

opportunity, but who do not have the requisite savings, the

state has invidiously distinguished between defendants. As

in North Carolina v. Pearce, 395 U.S. 71 1, 718 (1969),

Williams will have been subjected to “multiple punishments

for the same offense”, but in his case solely because of his

poverty.

A further example of the manner in which Illinois has

singled out indigents for excessive punishment is the state’s

construction of the Illinois statute which provides for dis

charge of certain classes incarcerated for nonpayment of

fines and costs. Sectibn 180-6 111. Rev. Stat. 1967 ch. 38

declares:

Whenever it shall be made satisfactorily to appear to

the Court after all legal means have been exhausted,

that any person who is confined in jail for any fine

or costs of prosecution, fipr any criminal offense,

hath no estate wherewith to pay such tine and costs,

or costs c'uiy, it shall be the duty of the said court to

discharge^such person from further imprisonment

for such fine and costs, wljich discharge shall operate

as a complete release of sluch fine and costs: Pro

vided, that nothing herein/shall authorize any person

to be discharged from imprisonment before the

expiration of the time forlwhich he may be sentenced

to be imprisoned, as partlof his punishment.”

The Illinois ijprem e Court linlited discharge under this

stat ate to only that class of persons who are physically

unable to work at the place of incarceration or when no

19

woi,i. was provided for them at such institutions (A.40).

Certainly, if Illinois is prepared to discharge such persons it

can hardly claim that incarceration of indigents is necessary

to its administration of the criminal law.

As Illinois Law stands appellant is punished simply

because he is an able-bodied poor person without savings.

Hie fact that a defendant may be able to work but is without

savings or employment,14 can no longer valid be made the

basis for sentencing him to the workhouse. This “theory

of the Elizabethan poor laws no longer fits the facts”

(,Edwards v. California, 314 U.S. 160 (1941)) of modern

life. Cf. Robinson v. California, 370 U.S. 660 (1962). We

are a society that has come to recognize that a man’s

poverty and unemployment often are something over which

he has no control. Persons caught in the backwater of a

rapidly advancing tide of economic growth, should not |be

penalized because of that fact. Appellant’s failure to have

S505 in his possession in the instant case is most accurately

viewed as an involuntary: symptom of his involuntary

poverty.15 /

This does not mean that’a non-indigent can.be fined and.

an indigent cannot, thus perhaps raising some questions of

discrimination against non-indigents. It is clear that alter-

14The irrationality of the S5-A-Day statute is further highlighted

when that»amount is compared to what a person cOuld earn outside

jail on a modern wage sc°le. Compare 29 U.S.C. §206 (minimum

wage SI.60 per hour). Ipt addition, a person in jail working off a

fine remains in jail not ju/>t for the work day,/but around the clock,

and during such period is.subject to all the strictures and deprivations

of liberty which make up/ the regimen of others in the prison popu

lation. / /

l s This view has been taken by many courts of late in declaring in

valid many of our archaic vagrancy statutes. See, e.g., Fenster v.

Leary, 30 N.Y. 2d 309, (1967); Alegata i Commonwealth, -353

Mass. 287, 231 N.E. 2'^201 (1967); Baker v. Binder, 274 F. Supp.

658 (W.D. Ky. \9G1)\-Smith v. Hill, 285 F\ Supp. 556 (E.D. N.Y.

1968); Ricks v. District o f Columbia, 414 F.2d 1097 (D.C. Cir.

1968).

\

|

/

20

nativt- means for the state to achieve its ends exist, and

where this is true the Constitution will not countenance

such invidious discrimination against the poor. Illinois law

creates a lien in favor of the state which permits execution

against an offender s real and personal property, a fine

enforcement system similar to the civil remedy of docketing

a judgment with a view towards executing on a debtor’s

acquired property § 180-4, 111. Rev. Stat. 1967, ch. 38.

Some states have written provisions for installment pay

ments into state law,16 though trial courts often have

inherent power to order installment payments without

specific statutory authorization of installment payments.17

The experience ot states and foreign countries with such a

system has been successful. In West Virignia, even during

the depression, only 5% of persons allowed to pay by

installments needed to be committed. Commitments fell

by 98%. in Sweden and by 96% in Great Britain when

insi-allme'ht payment systems were introduced. Note, Fines

and Fining-An Evaluation, 101 U. Pa. L. Rev. 10131023

(1953). Finally, a trial judge might impose on an indigent a

parole requirement that he do specified work during the day

to satisfy the fine. Cf. 50 App. U.S.C. §456.

Cal. Pen. Code Section 1205; Mn. Ann. Code Art. 52 Sec.

18; Mass. Ann. Laws ch. 279, Section 1A (1956); Mich Sta ts .

Ann.. Sec. 28.1075 (1959); Pa. St a t . Ann . title 19, Section 953-

56 (1964); S.C.Code Ann . Section 55-593 (1962); Utah Code

Ann. Section 77-53-17 (1953); Wash . Rev . Code Ann . Sec

9.92.070 (1961); Wis. Sta t . Section 57-04 (Supp. 1965).

See Martin v. Erwin (USDC WD-La., January 25, 1968; Supple

mental Order, February 27, 1968, Civil No. 13084), 12 Welfare

Law Bulletin 14, April 1968, CCH Property Law Reporter para.

750, p. 1752 where the district court on an application for a writ of

habeac. corpus reportedly held that the state court should have per-

mitted the convicted indigent to pay his fine in installments and that

providing the defendant with no alternative but to serve a sentence

was a denial of equal protection of the laws. The court reportedly

granted the writ of habeas corpus and ordered oayment of the fines

at the rate of $25 per month.

21

It might be argued that a system of execution or install

ment collection would be more burdensome on the state

than an assumed (dubious though it may be) ability of the

state to enjoy the labor of a defendant while in prison. But

the imposition of an extended prison term on indigent

defendants cannot be justified on the ground of administra

tive convenience. As the Court said in Rinaldi v. Yeager,

384 U.S. 305. 310 (1966);

Any supposed administrative inconvenience would be

minimal since repayment could easily be made a

condition of probation or parole, and those punished

only by fines could be reached through the ordinary

processes of garnishment in the event of default.

Thus, § 1 -7(k) is not saved by Illinois attempting to justify

it as a means of “working off” the fine during incarceration

Defendants with funds are given the choice of merely paying

the fine or serving a jail sentence, while indigents must

remain incarcerated. Secondly, the state has available alter

natives less infringing of liberty to collect the fine by means

of installment arrangejnents or execution. Third, the S5

a day rate of conversion of fine into labor is totally unrealis

tic in light of prevailing wage-rates—and thus creates a

penalty far more severe for the poor. Finally, to the

extent a defendant is unable to find work himself, the state

through public employment services or public works pro

grams is certainly bound to attempt to find it for him

before remitting him to incarceration.

Nor does the ?use of § 1 -7 (k) in the cases of recalcitrant

defendants who' refuse to pay (fines raise constitutional

difficulties. When a court has determined that a defendant’s

failure to pay is due to his conyumacy, there is no reason

why statutes of this type, or indeed the contempt power,

may not be used—consistent with the Fourteenth Amend-

bborn c efendant to pay his fine.18

forth in the provisions of the Model Penal Code, Proposed Official

Draft, § 302.2 (1962):

determination might be made is set

Continued

t

22

But the Sup-

limited con

absolutely n

appellant,

affirmation

if given the c

The state's

Williams’ cor

tory. Costs

criminal case'

court system,

serving one o

e Court of Illinois has not adopted such a

vtion of §1-7(k). There is, moreover,

dication of contumacy on the part of this

trial court found none, and appellant’s

s indigency and willingness to pay the $505,

rtunity, was accepted by the Illinois courts.'

empt to justify incarceration to “work off”

jst of $5 is also unnecessarily discrimina-

taxed against litigants in both civil and

a means of financing the operation of the

thus cannot be satisfactorily explained as

■e legitimate aims of the criminal law.19

“Conse.

cious i

“ (1

in the |

the m<

local s:

to sho\

tumacic

for his .

fault w:;

order o;

good fa:

ment, th

may ord

thereof i

: u, wonrayment; Imprisonment for Contuma-

ment, **

a a defendant sentenced to pay a fine defaults

t thereof or of any installment, the Court, upon

(insert appropriate agency of the State or

>nj or upon its own’motion, may require him

why his default should not be treated as con-

,may issue a summons or a warrant of arrest

ince Unless the defendant shows that his de-

• attributable to a willful refusal to obey the

ourt, or to a failure on his part to make a

it to obtain the funds required for the pay-

. shall find his default was contumacious and

^.ommitted until the fine or a specified part

19 Under the r

145, 254 N.E.2d

against appellant ..

obtain body exectr

lice exists, Illinois

Article II, §2 of

shall be imprisoned

tate for the benefit

scribed by law, or

fraud.” This sectlor

of contracts, exdresv

2d 786 (1947)’ /Vr.

(19..5) Buck v. Alex,

-awyers Title o f Phoenix v. Gerber, 44 111. 2d

69) if Illinois sought to enforce it’s judgment

tme manner as in a civil action, it could not

Je to mere inability to pay. Even where ma-

juires a showing of refusal to pay.

mois Constitution provides that “No person

bt, unless upon refusal to deliver up his es-

creditors, in such manner as should be pre-

ses where Mere is strong presumption of

es, howevei, only to judgments arising out

implied, Cdx v. Rice, 375 111. 357 31 N E

o f Blacklidge, 359 III. 482, 195 N.E. 3-

111. 167 182 N.E. 794 (1932) and not to

23

As Illinois does not imprison the indigent taxed with costs

in a civil action, it is difficult to conceive of some justifica

tion for doing so in a criminal case. Indeed, the requirement

that time in prison be served in default of the payment of

costs seems controlled by Rinaldi r. Yeager 384 U S 105

(1966) which held a New Jersey statute requiring an

unsuccessful defendant repay the cost of a transcript used on

appeal violated the Equal Protection Clause. Compare

Strattman v. Studt, 20 Ohio St. 2d. ___N.E. 2 d ___ f 1969)*

see also Anderson v. Ellington, 300 F.Supp. 789, (M.D.

Tenn. 1969); Wright v. Matthews, 209 Va. 246, 163'S.E.2d

158, (1968). (Imprisonment for non-payment of costs vio

lates Thirteenth Amendment).

^ 'S C° nCeded’ as aPPe{iant believes it must, that

101 days required imprisonment is a significantly harsher pen

alty than the choice of paying fine or serving the prison term

which is the punishment for a man with sufficient financial

resources to pay immediately, the state’s authorization of

such a course of punishment in the circumstances of this

case conflicts with the Fourteenth Amendment. A primary

purpose of the Equal Protection Clause is to secure “the

full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings for the

security of persons and property” and to subject all persons

to like punishment, pains, penalties, taxes, licenses and

exactions of every kind and to no other.” McLaughlin v.

£ 3 = i s p & g s x s i i s,

Kennedy,. People. 122 Ui 649 ‘ l 3 N E 2‘ | 3 ',i 8g7f

pa. ordinances or

Monell. 24? III. 383.93 N.E. 295 ( ]9l ij

Fhridct 379 U.S. 184, 192 (1964).“ On the basis of the

bqual Protection Clause this Court has acted to eliminate

discrimination against the poor from state criminal pro

cedure. 1 In Griffin v. Illinois, 351 U.S. 12 (1956) and

Douglas v. California, 372 U.S. 353 (1963), it was held that

24

96 U S 3? ? ! t0 the contrury- ln Ex Parte Jackson,

. ‘ ' f ) ’ Court was faced with a non-constitutional

clam that a federal court exceeded its jurisdiction in committing a de

fendant until a fine of SI00 was paid. No claim of indigency la s

made and the court ruled only that “the commitment of the peti-

!nne7 ?n C° Untyj ai1’ until his fine ^ paid, was within the discretion of the court under the statute.”

inter T I V; * ampler’ 298 U'S' 460 0 9 3 6 ) the Court merely held,

aha, that a provision in a commitment for imprisonment for

onpayment of fine and costs which was inserted by a clerk was

voi . e court stated in dictum that “Imprisonment does not fol-

Iow automahcaUy upon a showing of default in payment. It follows

if at all, because the consequence has been prescribed in the impost- ’

on ° f sentence The choice of pains and penalties, when choice is

S n ” S It f i f ' v ° f the C° Urt’ is Part of the judicial function. (id at 463, 64.) No constitutional claim, no claim of indi

gency or that the commitment exceeding the maximum set by law

seems to have been\raised.

\

- A l o n g course o f decisions under the Equal Protection Clause

have struck down numerous state practices which differentiate

between rich and poor in the administration of the criminal process

Gnffin v. Illinois, 351 U.S. 12 (1956) (denial of free criminal trial '

transcript necessary for adequate appellate review); Eskridge v Wash

ington State Board, 357 U.S. 214 (1958) (denial, absent trial court

inding that justice will thereby be promoted,” of free criminal trial

transcript necessary for adequate appellate review); Draper v. Wash-

tngton 372 U.S. 487 (1963) (denial on trial court finding that appeal

s frivilous, o f free criminal trial transcript necessary for adequate

r hf L reVr M T y Drown’312 U.S. 477 (1963) (denial, absent

public defender s willingness to prosecute appeal from denial of state

coram nobis petition, o f free transcript of coram nobis proceeding

necessary to perfect state appellate jurisdiction); Douglas v. California.

H I U.S. 353 (1962) (denial, absent appellate finding that appoint

ment of counsel on appeal would be of value to defendant or the

appellate court, of free appointment of counsel on appeal as of right

from ciiminal conviction); Burns v. Ohio, 360 U.S. 252 (1959) (denial

25

appelLk- reivcw could not be granted in such a way as to

'anas

, choed in Douglas v. California, supra at 355

"P '“ suPP'ied)- The corollary of this proposition is

the one or whtch appellant argues: there can beT o eoua

ustice where the kind of punishment a man gets depends

upon the amount of money he has. In fart in ■! .11.

situation the relationship between poverty and prej’udjce'is

far more direct. In Griffin and Douglas, one m a y on,V

" V w t , de,endant W0UW 1»™ wo" his f re ° e d l

pre en I m° ney to W a transcript; in the

n ' tC‘?S<\ lhere 1S no need for speculation. If the

ppellant had had the money to pay the fine imposed he

would no, have been imprisoned more than one year

n - draw:l on the basis of wealth or property like

of race are traditionally disfavored ” Harper v

gnua Board o] Elections, 3 83 U .S 6 63 668 M 9 6 ^

s™jec "“ , " h:.Ch di^riminute on the basis of wealth are

Fourteenth' A 7 b"rden ° f Justification which the ourttenth Amendment has traditionally required o f st-,m

statutes drawn according to r a r e ” / q T ° f State

U S 1 9 ( | QA7 t n 1 ^ i L o v '" g v. Virginia, 3 8 8

o f Firm r 7 ° n V ast term in McDonald v. Board

f Election Commissioners, 3 9 4 U.S. 8 0 2 , 8 07 ( 1 9 6 9 ) the

Court made i, plain the E<1ual Protection C la u fre ^ u im s

X a fel-

be forced pay “ 2 , 1 * " ' ! prison may

also Williams , a ,y o f Oklahoma C i!7. 3 9 5 U S 458 ( f f f ' f f "

V. California, 393 U S 367 hqaov c ' ’ i y69)> Cardner( , Qr;7t . ; f , * - ( 1969); Swenson v. Hosier 386 II 9 ->ss

(1967), Anders v. California, 386 U S 738 l p i ' 258

389 U.S. 40 (1967)- L m u r„ n / f f ( I967)’ Rob^ t s v. Lavallee,

(1966) ' 1 g l)lstnct Court o f Iowa, 385 U.S 197 ■

26

the basis of wealth or race ,lneS are drawn

A Jaw which discriminates on the (f mphasis suPPh'ed).

enacted pursuant to a valid state • frace’ “even though

only ,f lt is necessary, and not m ' ' Wl11 be upheld

to the accomplishment of n Y ratlona,,y related

M cLaum n ,, * * a P o s s ib le state policy/’

Vuginia, supra at J J. 96’ ech°ed in Loving v.

Clearly punishment of thieve ■

interest. However the L n n v 1$ 8 permi^ b le state

such a way that the poormsuffer10mn0f 0?^ PUnishment in

related (and certainly not nere than the rich is not

° [ the state’s objectives of de!^ ^ ^ accomPlishment

rehabilitation of wrongdoers J i ,ntimidati0n or

§,1; 7(k) ls constitutional because / / T ^ argUed that

J?,ke- But m Griffin v. Illinois, supra t h T ^ ^ poor

the requirement for payment o f rZ t ° m struck down

despite the fact that costs f Costs as apphecl to indigents

Poor alike. Justice B1 ° f b° tb * * and

grossly discHminaforv ^ilTilson^ ltS faCe may be

this Court struck' down ti peratlon- p or example - --

/ ’°ndls" i™" a to r y . ( S a $

and f lo S to ”

_________ J P ’ the Court ruled that a

/ t e l ' 'O'. 27jN.r.s.2d 972, 218 N E 2d

both a state statute and the violated

H ~ r : „ . . .

oerced into payment if he

I

state poll tax violated the Equal Protection Clause because

the tax (which was non-discriminatory on its face) was an

invidious discrimination against the poor.

That the state need not, indeed cannot, equalize every

advantage possessed by rich defendants hardly compels the

result reached in this case by the Supreme Court of Illinois.

Permitting indigent defendants such as appellant to earn

the amounts required by their tines does not in any realistic

way sap what may be the state’s limited financial resources.

Alternate means oi collection, such as installment payment

or execution, are available. Thus, appellant’s submission

merely amounts to an acknowledgment that when liberty is

at stake the state has an obligation to cure a drastic impact

of poverty on the administration of the criminal law when

it can do so. Cf. People ex rel. Herring v. Woods, 37 111.2d

435, 226 N.E. 2d 594 (1967) (pre-trial detention credited

in order that total imprisonment not exceed maximum).

This case does not involve the question dealt with in

several cases, e.g., United States ex rel. Privatera v. Kross,

239 F.Supp. 118 (S.D.N.V. 1965) aff’d 345 F.2d 533. (2nd

Cir. 1965), ceit. denied, 3$2 U.S. 91 1(1965), âs to whether

an indigent is deprived of equal protection ot the laws when

subsequent to failure to pay a fine he is imprisoned for a

period which does not exceed the maximum prison term

possible for the substantive offense. While such imprison

ment ot any indigent for nonwilful failure to pay a fine

raises a serious const utional question, it might be argued

that the resulting imprisonment is jijstifiable on grounds

ay; therefore, the addi-“has no money or property” with which to ^ ulc auui

t.onal imprisonment in lieu of the fine can only have been’intended

as extra punishment, extending the punitive imprisonment beyond the

statutory maximum. A unanimous court (found that incarceration

he clause of the Eighth Amendment as well asviolated the excessive

the Equal Protection Clause because incarceration at SI.50 per day

notably exceeds in amount that which is reasonable, usual, proper

and just. (218 N.E.2d at 688). Accord: Sawyer v. District of

Columbia, 238 A.2d 314 (D.C.App. 1968). *

J *

other than indigency. “The result may depend upon a

parhcular combination of infinite variables peculiar to each

CaWlina V ^ - 395 U S . 7,1 722 (1969), see also § 1-7(g) 111. Rev. Stat. 1967 ch 38’

Ind'vjdua ^ed sentencing, it might be contended justifies^'

judicial classification which results in greater imprisonment

being imposed on one who might satisfy the interests of the

criminal law with a fine if he could pay it forthwith

. J " th ;; f resent case’ however, Williams, could only be

ntenced to more than a year in prison by reason of his

tion^n ̂ nder hhnois law, no consideration of rehabilita-

reached'o f°mmUniIty C° Uld accomPhsh the result

“ ^ r ng s5o° f,ne and $s c° urt c° stsadditional days in prison. Indeed, Judge Weinfeld the

th 'a Y S e ^ reC°e" 'Zed disti"ctio"

. . .the issues raised by petitioner would be more

he rbeenPsenetetedHn COnstit{ltional terms hadhe been sentenced, as some defendants have to the

maximum permissible jail term and fined’ $500

4001 ‘v‘r reSUl‘ * addi,i°"a lt a H t o n ^ o f u p ^ -

ctr ■ i / r or„ sentenced under a statute calling for a straight fine.” (239 F.Supp. at 1 21)

Of course one can seriously question the assumption that

f f 8 * sentence of imprisonment or Jot. And coercion nf

a nend or relative tq pay, while a possible subrosa purpose

seems opposed to oiir fundamental Understanding rhnt

man should be penalized for ,he c rim l o f h t friend or

relative in which he himself did not (participate A defen

lo pay” and°tfie ^ " T " ? ^

2 S , dT f " SohfOU!dhemaf,neeehberatdy after such a hearing. . . ” Morris v. Schoonfeld,

28

TT^r

29

f i ^ M SU7« ,15n ]6u (D Md' 5969), jurisdictional statement filed No. 782, October 28, 1969, 38 U.S.L. Week 3162.

But there is a fundamental difference between this case-

w lie i only an indigent defendant is imprisoned for a

period greater than that allowable by the statute which

fixes the maximum penalty for the offense-and the case

where the penalty of imprisonment imposed, though

enhanced by failure to pay a fine, is nevertheless less than

the maximum set by the legislature. In the former case the

additional imprisonment responds to no valid objective of

the criminal law, but rather to the defendants financial

situation. In the latter, it is at least possible that the particu-

lar record may reveal circumstances which support the

additional imprisonment. In short, a judge who sentences

30 days or 30 dollars may justifiably find that punishment,

deterrence and intimidation require some immediate impo

sition of Penalty of some sort greater than a future obligation

° Pdy- HlS dls^ etlon to sentence certainly contemplates

such judgments « but conversion of indigency into jail

time greater than that allowed for any other reason does

rCSPOnd t0 any Particul*r judgment about a defendant or the needs of the criminal law. It is

quite simply punishment for poverty.

CONCLUSION

The experience of appellant Williams is similar to that of

countless other poor citizens who find themselves enmeshed

m the criminal process. Arrested for a minor crime, he had

already spent several weeks in jail when he came to trial

because of his financial inability to make bail. Legal counsel

being beyond his means, he was tried and convicted without

whe” 7 " L SComhefd Z m e " ’' UHnlike N°r'h Caru“»‘ -■

must be based upon: rLaSC , sentencing uP°n reconviction

«d menial and moral propensities.'” (§95 U S a , 723)“

*r~— -

30

an attorney. Given the maximum sentence allowable for

the offense with which he had been charged, he learned that

he would have to spend several additional months in jail

solely because he was too poor to pay the fine and the court

costs imposed upon him.24

It is thus no accident that the National Advisory Com

mission on Civil Disorders has concluded:

Some of our courts. . .have lost the confidence of

tie poor. The belief is pervasive among ghetto

residents that. . .from arrest to sentencing, the poor

and uneducated are denied equal justice with the

ailment, that procedures such as bail and fines have

been perverted to perpetuate class inequities. We

have found that the apparatus of justice in some areas

has itself become a focus'for distrust and hostility

Too often the courts have operated to aggravate

athtr than relieve the tensions that ignite and fire

disorders (Report of the Commission, p.337

[Bantam, 1968]) (Emphasis added)

2 4 The problem of jailing indigents in lieu of fine has long affected

S o n T r " S PerSOm ,'n tWS C0Untry' ™ rty years ago the National Commission on Law Observance and Enforcement pointed

S u e tomnavinr te nUI? e' °f °ffenderS Wh° were imprisoned for

Parole 14<M1 S . / T Pef Instit^ons, Probation and rarole 1404 (1931). More recently, a study of the Philadelphia

miS lYfJai Sh°wed that 60 Percent of the inmates had been com-

nutted for nonpayment. In 1960, there were over 26,000 prisoners

in New York City jails who. had been imprisoned for default in pay

ment of fines. The President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and

Admimstmron of Task Force Report, The Courts 18 (1967)

Cnl Sub,n ReP°rt on the administration of justice in the District of

n fo 7 S J rnd th3i ° p °f 3 S3mple 0f 105 c°nvicted defendants, (or 6/p) received a fine or imprisonment in default of payment

(19fi6fCe Th^rv Cnmma! Justice in a Metropolitan Court, pp. 88-89

(studv of rnf-j Dlstnct o f Columbia Crime Commission found in its

/ 83 Pr TSOn$ sentenced’ in the Court of General Sessions

m e n t is 3"!? ? 19%) WCrC sentenced t0 a fine and to imprison-

fine VnH °f Payment. Of these 105 persons could not pay the

fine and were incarcerated. Report of the President’s Commission on

Crime m the District of Columbia 394, (1966).

imprisonment predtoably E f f e c t s 'd S m ' t° f . fin“ byn r z

identical offenses under essen,Mv° ^ T ” C° " ViCted of

and upon comparable records, and s e n T e te d T o ™ ^ ? 5 same fines will walk n,,t nr entenced to pay the

s « t

fine has been the same.”« ntentlon to Pay «ie

limit the range of permissible flic : 56 thlS Court began to

Poor in crindnal p” ta,W* n ^ 3"dpremise. mgS' The Court began with this

31

Counfy cn l'965) '̂s V L o / W ^ V l ’ N'YS-2d 970 (Orange

N.Y.S.2d 941 tOr-mop r °£ C V' McMlllan 53 Misc.2d 685 279

that the sentencing of a defendant the C°Urt beld

where the court knew that the ^ d ' ; °f “ fi"e

money to pay the fine violated the ! f lnd'gent and had no

under law. In so holding the court ncip*fs of equal treatment

which all of the engines oftie criminal ' , these times in

serving and defendmg the lights o i T ^ ‘°Wards ^

should avoid resort to an archaic cV '"dlgent, our local courts

debt.” Id. at 943. system akln to imprisonment for

< \

/

‘-ce°nthJ q2 ' P7 teCti0n and due P™cess emphasize the

charged with c r ^ L 'm i V s o '^ f ' t h 'Y 311 Pe° PlecernpH’ ” i ^ ^ as the law is con-

Z £ y a S “ bar o f JUS,i“

It concluded that:

" S r . ™ „ bi , r de ;T „ i j r S e ,vhere the wnd ° fhe has.” (Id at “ f " * ° n ,he an,olim of money

maI°ob; r „ f L 7 ; e Pa,b,eha; i^ m‘,S;t FM “A

expensive, able counsel not within [hfreach 0/ “ ''° " ° f

E lib e 'tV is2/ , “

available ,0 preserve legitimate' ” *

r r rtbew tfr a dcao” t ss wor,hy ° r

punished for his c r im e b y T J ^ U c n , rf* af defendan‘ be

e f e T f wa^w Lch t ne v ltT „ rr " T nt ^ ^

.Heir freedom while financially .b E ’d r i S J ^ j T ^

H

1

33

For the foregoing reasons the judgment below should be

reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

Jack Greenberg

Michael Meltsner

Charles Becton

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Stanley A. Bass

Community Legal Counsel

1 1 6 South Michigan Avenue

Chicago, Illinois 60603

Haywood Burns

1 1 2 West 1 20th Street

New York, New York

Anthony G. Amsterdam

Stanford University Law

School

Stanford, California 94350

Attorneys for Appellant

I