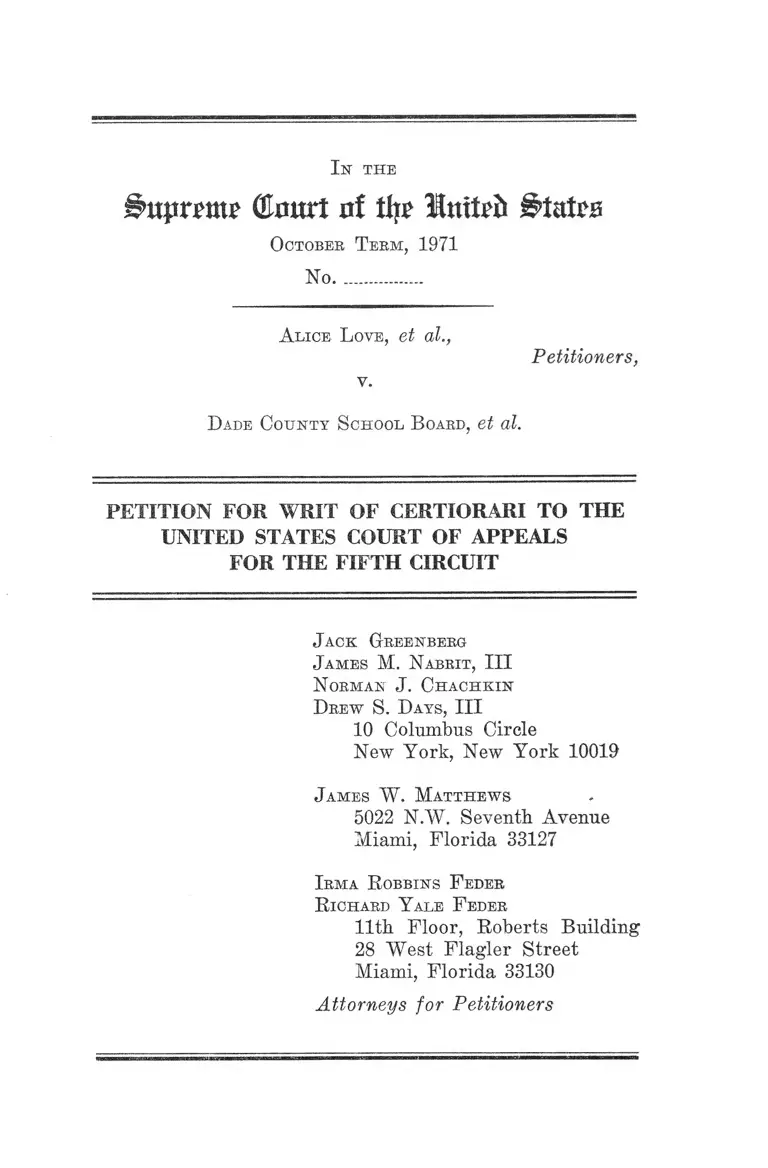

Alice Love v. Dade County School Board Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Alice Love v. Dade County School Board Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1971. c39943c8-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1ed4a190-9aa7-4acc-aa92-4356246495e5/alice-love-v-dade-county-school-board-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

GImtrt nf % Mmtzb States

October T erm , 1971

No. ...............

I n th e

A lice L ove, et al.,

v.

Petitioners,

D ade Cou nty S chool B oard, et al.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

J ack G reenberg

J ames M. N abrit, III

N orman J. C h a c h k in

D rew S. D ays, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

J ames W. M atth ew s

5022 N.W. Seventh Avenue

Miami, Florida 33127

I rm a R obbins F eder

R ichard Y ale F eder

11th Floor, Roberts Building

28 West Flagler Street

Miami, Florida 33130

Attorneys for Petitioners

I N D E X

PAGE

Opinions Below .................................................................... 1

Jurisdiction .......................................................................... 2

Question Presented ............................................................ 2

Constitutional Provisions Involved ................................. 2

Statement of the Case .............. 3

Introduction....... .......................................................... 3

The Proceedings B elow .... .......................................... 4

Beasons for Granting the W r it ........................................ 6

Conclusion ...................................................................................... 13

A ppendix—

Order Dated June 14, 1971 ....................................... la

Order Dated June 18, 1971 .... 5a

Order on Motions For Evidentiary Hearing ....... 8a

Opinion of United States Court of Appeals For

the Fifth C ircuit......................................................

Exhibit 1(b)

10a

11a

11

T able oe Cases

page

Bradley v. Board of Public Instruction, 431 F.2d 1377

(5th Cir. 1970) ................................................................ 10

Bradley v. School Board of Richmond, 382 U.S. 103

(1965) ............................................................................... 7

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) ..... 3

Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Board, 396

U.S. 290 (1970) .............................................................. 7

Davis v. School Commissioners of Mobile County, 430

F.2d 883 (5th Cir. 1970), reversed, 402 U.S. 33 (1971) 10

Davis v. School Commissioners of Moble County, 402

U.S. 33 (1971) .................................. 2, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9,10,12,13

Ellis v. Board of Public Instruction, 423 F.2d 874 (5th

Cir. 1970) .......................................................................... 10

Goss v. Board of Education of Knoxville, 403 U.S. 956

(1971) ................................................................................ 7

Green v. County School Board of New Kent County,

391 U.S. 430 (1968) ......................................................... 3

Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction, 427 F.2d 874

(5th Cir. 1970) ............... .......... ............. ........................ 10

Northcross v. Board of Education, 397 U.S. 232 (1970) 7

Pate v. Dade County School Board, 434 F.2d 1151 (5th

Cir. 1970) cert, denied, 402 U.S. 953 (1971) .........3,10,11

Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965) ................................ 7

Swann v. Charlotte-MecMenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1 (1971) ............................ 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 9,10,12,13

(Burnt of iljp #>iatpa

O ctober T erm , 1971

No..................

I n the

A lice L ove, et al.,

v.

Petitioners,

D ade County S chool B oard, et al.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for the

Fifth Circuit entered in the above-entitled cause on Septem

ber 3, 1971.

Opinions Below

The opinions of the courts below directly preceding this

petition are as follows:

1. The District Court order of June 14, 1971 is un

reported and is printed in. the appendix hereto,

infra, p. la ;

2. The District Court order of June 18, 1971 is un

reported and is printed in the appendix hereto,

infra, p. 5a;

2

3. The District Court order of June 30, 1971 is un

reported and is printed in the appendix hereto,

infra, p. 8a;

4. The Court of Appeals order of September 3, 1971

is unreported and is reprinted in the appendix

hereto, infra, p. 10a.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered on

September 3, 1971 (appendix, p. 10a, infra). On Novem

ber 24, 1971, Mr. Justice Stewart extended the time for

filing the petition for certiorari until January 15, 1972.

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under 28 U.S.C.

Section 1254(1).

Question Presented

Whether the courts below erred by approving a desegre

gation plan for Dade County which leaves one-fourth of the

black pupils in all-black schools without holding a hearing

or making findings with respect to the issues framed in

this Court’s recent decisions in Swann v. Charlotte-Meck-

lenburg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1971) and Davis

v. School Commissioners of Mobile County, 402 U.S. 33

(1971), creating a presumption against one-race schools.

Constitutional Provisions Involved

This case involves the Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States.

3

Statement of the Case

Introduction

This is a school desegregation case involving the public

education system of Dade County, Florida. Petitioners seek

review by this Court of the extent to which the desegrega

tion plan currently in force in that school system meets

the constitutional requirements established in Brown v.

Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), Green v. County

School Board of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968), and

Swann v. Charlotte-Mechlenburg Board of Education, 402

U.S. 1 (1971). In the rulings below which petitioners here

challenge, the district court permitted the Dade County

School Board [hereinafter, “ the Board” ] to continue operat

ing its system during 1971-72 essentially in accordance with

a desegregation plan which the Fifth Circuit Court of

Appeals ordered implemented at the commencement of the

1970-71 academic year.1 2

The Dade County system was segregated by law at the

time of Brown, supra and continued to operate schools in

which no significant desegregation was achieved for many

years thereafter. As recently as the 1969-70 academic year,

the Board was administering 217 schools enrolling 262,295

students of which 25.8% were black. At that time approx

imately 57.9% of the total black enrollment attended 85-

100% black schools.8 Though the court of appeals order

of August, 1970 reduced the number of virtually all-black

1 The Fifth Circuit’s exhaustive decision setting out a desegrega

tion plan for Dade County schools is reported in Pate v. Bade

County School Board, 434 F.2d 1151 (5th Cir. 1970), cert, denied,

402 U.S. 953 (1971). Earlier proceedings in the same case are

reported at 303 F.Supp. 1068 (S.D.Fla., 1969) ■ 307 F.Supp. 1288

(S.D.Fla., 1969) remanded for further proceedings, 430 F 2d 1175

(5th Cir., 1970); 315 F.Supp. 1161 (S.D.Fla., 1970).

2 “Final Desegregation Plan” (March 31, 1970).

4

schools in the system, statistics on the progress of deseg

regation for the 1970-71 and the 1971-72 academic years

point np the substantial degree to which vestiges of the

state-imposed dual system are still present in Dade County.

In September, 1970, black students constituted 25% of the

total population of which 29% were enrolled in 85-100%

black facilities.3 For the 1971-72 academic year, black stu

dents represent 26% of the total enrollment in Dade County

Schools. Twenty-three percent (23%) of this total black

enrollment attend 85-100% black facilities.4

Proceedings Below

On May 26, 1971, the Board filed with the district court

a set of proposed modifications, for the 1971-72 academic

year, of the desegregation plan mandated by the Fifth

Circuit Court of Appeals in August, 1970. By order of

June 14, 1971, the district court indicated that it had re

tained jurisdiction of the Dade County case only “to assure

that the school system was continually maintained in a

unitary manner.” Since, in its view, the system had been

declared unitary, the court saw its only responsibility as

that of assuring that the school system did not revert to

a state-imposed dual system. It granted all parties an

opportunity to file responses to the Board’s proposed modi

fications and to be heard at a hearing set for June 18, 1971.

On June 16, 1971, petitioners filed objections to the Board’s

proposals, arguing that the Court should reject suggested

modifications which: (1) sought to increase the ratio of

white students in three schools which enrolled children of

both races in 1970-71; and (2) established boundaries for

3 Report to Court (December 4, 1970).

4 Report to Court (November 10, 1971). These statistics were not

available to the Courts below during the most recent proceedings in

this case. However, data from the November, 1971 report is set-out

in the appendix hereto, infra, p. 11a for this Court’s benefit.

5

five or six new schools in such a way as to assure all-white

or virtually all-white enrollments. Petitioners approved of

the Board’s proposal to reduce substantially predominantly

black enrollments in four schools. However, the objection

noted that, since boundary changes for 27 of the 40 schools

considered made no significant alteration in the degree of

desegregation in those facilities, the Board’s proposals con

stituted “nonaction” .

After the June 18, 1971 hearing, the district court imme

diately entered an order rejecting petitioners’ objections

and approving the Board’s modifications for 1971-72. Fur

thermore, the court held that thereafter the Board would

not be required to petition the court for approval of any

proposed modification in its desegregation plan. In the

future, the burden would be upon the petitioners and other

intervenors to demonstrate to the court a prima facie case

of the Board’s failure to maintain a unitary school system.

On June 22, 1971, petitioners and another intervenor, the

Dade County Classroom Teachers’ Association (C.T.A.),5 6

filed motions with the district court for an evidentiary

hearing at which the Dade County system could be re

evaluated in light of new guidelines established by this

Court in Swann, supra and, Davis v. School Commissioners

of Mobile County, 402 U.S. 33 (1971). The motions of peti

tioners and the C.T.A. set out in great detail, among other

matters, the extent to which the Board, the Florida School

Desegregation Consulting Center (HEW ), the district court

and the court of appeals (1) had rejected the use of non

contiguous pairings and groupings of schools and “ cross

busing” in attempting to desegregate the Dade County

system; (2) had failed to use the system-wide black-to-white

5 Although the C.T.A. does not join in this petition for a writ of

certiorari, it was co-appellant with the petitioners herein before the

Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals in case No. 71-2338.

6

ratio as a starting point in fashioning a desegregation plan;

and (3) had not entertained a presumption against the

continued operation of one-race schools, in evaluating in

1970 alternative methods for desegregating the Dade

County system. The motions asserted that Swann, supra

and Davis, supra, now required the district court to em

ploy the criteria it rejected in 1970 to determine whether

the Dade County system was truly “unitary” . Such a re

consideration, petitioners contended, would establish: first,

that existing black schools in the system were vestiges of

the state-imposed dual system; and, second, that each of

these black schools could be desegregated fully in a feas

ible manner using techniques approved by this Court in

Swann, supra. It was submitted that, in any event, the

burden was upon the Board to show why the remaining

black schools could not be desegregated based upon Swann

guidelines.

On June 30, 1971, the district court denied motions of

petitioners and the C.T.A. for an evidentiary hearing. Peti

tioners duly filed Notice of Appeal to the Fifth Circuit

from the June 18 and June 30 orders of the district court.

On September 3, 1971, without oral argument, the court of

appeals summarily affirmed the district court’s denial of

an evidentiary hearing.

Reasons for Granting the Writ

This case merits review on certiorari because the courts

below have permitted one of the ten largest school systems

in the nation to continue operating numerous segregated

schools without applying the legal principles announced

by this Court in Swann v. Charlotte-Meclderiburg Board of

Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1971), and Davis v. School Commis

sioners of Mobile County, 402 TJ.S. 33 (1971). Indeed, the

desegregation plan in effect in Dade County is explicitly

7

premised on the Fifth Circuit’s reasoning in the Davis case

which this Court has reversed. There has been no recon

sideration of the details of the Dade County plan by either

court below since Swann and Davis, and there are no find

ings and conclusions which address the important doctrines

enunciated by this Court in those decisions. We think that

the matter presents so plain a conflict with this Court’s

recent decisions, and the time available to prepare a new

plan for next year is so short, that this Court should grant

certiorari and summarily reverse, directing further pro

ceedings conformable to Swann and Davis*

The decisions of the courts below approve a desegrega

tion plan for Dade County, Florida under which a substan

tial proportion of black student population will remain in

definitely in virtually all-black schools. Court sanction was

given to the desegregation plan in force based upon legal

theories that pre-date and clearly conflict with doctrines

articulated by this Court in Swann and Davis. Neverthe

less, the courts below have summarily rejected petitioners’

contention that these most recent pronouncements estab

lish new constitutional standards against which all prior

efforts to dismantle dual, segregated school systems must

be measured.

Official Board reports for the 1970-71 and 1971-72 aca

demic years reveal that substantial numbers of students

are continuing to attend one-race schools in Dade County.

In September, 1970, the Board operated 218 schools, en

rolling 239,218 students. Of that total, 179,318 students

were white and 59,000 were black (75% white, 25% black).

6 This Court has found such disposition appropriate in several

recent school desegregation cases. Carter v. West Feliciana Parish

School Board, 396 U.S. 290 (1970) ; Northcross v. Board of Edu

cation, 397 U.S. 232 (1970) ; Bradley v. School Board of Richmond,

382 U.S. 103 (1965) ; and Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965).

Cf. Goss v. Board of Education of Knoxville, 4.03 U.S. 956 (1971).

8

During that year, 83 schools had 99-100% white enrollments

and seventeen (17) schools had enrollments between 85-

100% black. Ten of these seventeen schools were 99-100%

black, three were 90-94% black and four had between 85-

89% black enrollments. These virtually all-black schools

enrolled 17,131 or 29% of the total black student population

of Dade County.7 In this current academic year, 1971-72,

the Board is operating 218 schools in which a total of

245,242 students are enrolled. Of that number, 182,029 stu

dents are white and 62,213 are black (74% white, 26%

black). There are 69 schools which have between 99-100%

white enrollments and fifteen (15) schools with between 85-

100% black enrollments. Ten of these schools have 99-100%

black student bodies, three are 91-95% black and two have

87% and 89% black enrollments. Approximately 14,686, or

23% of the black enrollment of Dade County attend these

7 The 17 virtually all-black schools operated

as follows:

Grades Black

School Served Students

North County

C.R. Drew

L.C. Evans

Holmes

Liberty City

Olinda

Orchard Villa

Poineiana Park

C.R. Drew

Miami-Northwestern

Allapattah

Earlington Heights

Floral Heights

F.S. Tucker

Miami- J ackson

Pine Villa

Goulds

K-6 970

K-6 951

K-6 991

1-3 607

K-6 820

1-6 863

K-6 1273

K-6 1208

7-9 1247

9-12 2265

6 231

K-6 892

1-6 745

K-3 490

10-12 2267

1-6 1039

1-6 272

Total 17,131

during 1970-71 were

White

Students % Black

134 88

0 100

4 99

38 94

0 100

1 99

0 100

0 100

0 100

2 99

18 93

2 99

0 100

84 85

282 89

69 94

47 85

681

9

fifteen schools.8 The schools that are virtually all-black in

1971-72 were all over 95% black in 1969 when the first sig

nificant steps were taken to dismantle the state-imposed

dual system in Dade County. And it is reasonable to as

sume that substantial numbers of black students will attend

one-race schools in the future. For, if the Board’s May 26,

1971 proposal is any guide, prospective modifications of the

current plan, at best, will have no impact upon desegrega

tion. At worst, such alterations will create additional one-

race schools. Furthermore, the district court has so circum

scribed its own authority to require further desegregation

that it cannot be expected to take any initiative in reducing

the number of one-race schools in the Dade County System.

However, this Court’s decisions in Swann and Davis pro

vide guidelines for evaluating the constitutionality of de

segregation plans like Dade County’s which envision the

continued existence of one-race schools. First, “having

once found a violation, the district judge or school authori-

8 The following fifteen schools have virtually all-black enrollments'

for 1971-72:

Grades Black White

School Served Students Students % Black

North County K-6 1105 111 91

C.E. Drew K-6 902 0 100

L.C. Evans K-6 1018 0 100

Holmes K-3 706 34 95

Liberty City K-6 829 0 100

Olinda, K-6 884 0 100

Poinciana K-6 1141 0 100

Orchard Villa K-6 1274 0 100

C.E. Drew 7-9 1217 0 100

Miami-Northwestern 9-12 2187 4 99

Allapattah 6 301 45 87

Darlington Heights K-6 889 8 99

Floral Heights K-6 843 0 100

Goulds K-6 318 41 89

Pine Villa K-6 1072 68 94

Totals 14,686 311

10

ties should make every effort to achieve the greatest pos

sible degree of actual desegregation, taking into account

the practicalities of the situation.” Davis, supra, at 37.

Second, in attempting to achieve maximum desegregation,

school boards and courts should recognize the existence of

“a presumption against schools that are substantially dis

proportionate in their racial composition.” Swann, supra,

at 26. And finally, Swann holds that:

Where the school authority’s proposed plan for conver

sion from a dual to a unitary system contemplates the

continued existence of some schools that are all or

predominantly of one race, they have the burden of

showing that such school assignments are genuinely

nondiscriminatory. The court should scrutinize such

schools and the burden upon school authorities will be

to satisfy the court that the racial composition is not

the result of present or past discriminatory action on

their part. (Id. at 26)

Neither of the courts below has ever addressed itself to

these issues framed by Swann and Davis. In its August,

1970 decision which outlined what it viewed as a constitu

tional desegregation plan for Dade County,9 the court of

appeals explicitly relied upon its Davis decision10 (later re

versed in this Court), and three similar cases.11 In each of

those cases, the court of appeals reduced the percentage of

black children in virtually all-black schools to between 20-

9 Pate v. Dade County School Board, 434 F.2d 1151, 1152 (5th

Cir. 1970).

10 Davis v. School Commissioners of Mobile County, 430 F.2d 883

(5th Cir. 1970), reversed, 402 U.S. 33 (1971).

11 Ellis v. Board of Public Instruction, 423 F.2d 874 (5th Cir.

1970); Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction, 427 F.2d 874 (5th

Cir. 1970) ; and Bradley v. Board of Public Instruction, 431 F.2d

1377 (5th Cir. 1970).

11

25% through the use of equi-distant zoning or contiguous

pairing and grouping of schools without doing violence to

what it denominated “the neighborhood school concept.”

Non-contiguous groupings and “cross-busing” were rejected

as incompatible with the neighborhood concept; respect for

district lines was necessary to maintain a viable neighbor

hood school system; and the presumption was not against

the continued existence of one-race schools but in favor of

their existence where disruption of a “neighborhood” would

be required to desegregate such facilities. The court of

appeals strictly adhered to identical principles in this case.

For example, it determined that the desegregation of six

north central district virtually all-black schools was infeas

ible because:

the attendance zones of all six of these schools are

bordered by attendance zones of schools which are

either already paired with outlying substantially white

schools or are all-Negro themselves. (Pate, supra, at

1155).

The court gave no consideration to the possibility of non

contiguous groupings of the six schools with predominantly

white schools in the northeast district. And, without making

any findings on the times or distances related to student

transportation, the court of appeals determined that the

Drew Junior High could not be desegregated because it

was:

situated in the northern part of that concentration of

the Negro elementary schools in the center of the City

of Miami discussed above and is also over three miles

from the nearest predominantly white junior high.

(Id. at 1157.)

As a consequence of these arbitrary limitations imposed

upon what techniques could be used to achieve greater

12

desegregation, the court of appeals decision left approx

imately 24% of the black student population in virtually

all-black schools.

It cannot be denied that Swann and Davis forthrightly

rejected and overruled the “neighborhood school concept”

standards articulated by the 1970 Fifth Circuit decisions

in this case and other cases. In Davis, this Court held:

A district court may and should consider the use of

all available techniques including restructuring of at

tendance zones and both contiguous and non-contigu-

ous attendant zones. (Davis at 37.)

# # *

On the record before us, it is clear that the Court of

Appeals felt constrained to treat the eastern part of

metropolitan Mobile in isolation from the rest of the

school system and that inadequate consideration was

given to the possible use of bus transportation and

split-zoning. (Id. at 37.)

And Stvann pointed out that objection to increased trans

portation based upon opposition to “cross-busing” per se

was constitutionally irrelevant. Valid objection to trans

portation could be raised only “when the time or distance

is so great as to either risk the health of the children or

significantly impinge on the educational process.” Swann,

supra at 30-31.

Yet, in the most recent proceedings in this case, the

courts below failed once again to address themselves to the

issues raised by Swann and Davis with respect to the con

tinued existence of one-race schools. Petitioners’ motion

and that of the C.T.A. for an evidentiary hearing not only

correctly pointed up the fact that the Dade County system

was presumed unconstitutional in light of this Court’s

discussion of one-race schools in Swann and Davis. It

13

alleged, in addition, that feasible means existed for de

segregating all of the remaining virtually all-black schools

in the system. Armed with this presumption of unconstitu

tionality and with allegations that the “greatest possible

degree of actual desegregation” had not been achieved in

Dade County, petitioners were properly entitled to an evi

dentiary hearing before the district court. Petitioners sub

mit that until the Dade County system has been subjected

to and has met the standards established by Swann and

Davis, neither the Board nor the courts below can legiti

mately claim to have eradicated all vestiges of the dual

system.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, it is respectfully submitted

that this Court should grant certiorari, summarily reverse

the judgment below, and direct further proceedings con

formable to Swann and Davis.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit, III

N orman J . C h a c h k in

D rew S. D ays, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

J ames W . M atthew s

5022 N.W. Seventh Avenue

Miami, Florida 33127

I bm a R obbins F edeb

R ichard Y ale F edeb

11th Floor, Roberts Building

28 West Flagler Street

Miami, Florida 33130

Attorneys for Petitioners

APPENDIX

Order Dated June 14, 1971

I n the

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

I n and F oe th e S outhern D isteict oe F lobida

M ia m i D ivision

No. 69-1020-Civ-CA

H ebbebt P ate, et al.,

v.

Plaintiffs,

D ade C ou nty S chool B oaed, et al.

Defendants.

By order dated June 26, 1970, as modified by order dated

July 24, 1970, this Court found the Dade County school

system to be a unitary school system in which all vestiges

of a state-imposed dual school system had been eliminated.

Pate v. Dade County School Board, 315 F. Supp. 1161

(S. Dist. Fla. 1970). On August 12, 1970 the Fifth Circuit

Court of Appeals, after affirming all of the changes in the

School Board plan made by this Court and ordering several

further changes, stated that “Implementation of these

modifications effectively desegregate the Dade County

School system.” Pate v. Dade County School Board, 434

F.2d 1151, 1154 (5th Cir. 1970), cert. den. 39 U.S.L.W. 3487

(U.S. May 4, 1971). This Court retained jurisdiction to

assure that the school system was continually maintained

in a unitary manner.

la

2a

Once having disestablished the dual school system and

eliminated racial discrimination through official action from

the system, there remains vested in the authority of this

Court only the responsibility to assure that the school sys

tem does not revert to a state-imposed dual school system.

See, Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

39 U.S.L.W. 4437 (U.S. April 20, 1971).

The Court is aware, from the proposed plan as well as

from letters from concerned parents, that there are serious

problems which must be overcome before the approved plan

can be improved to meet everyone’s approval. Some of the

more obvious problems revolve around the withdrawal of

white students from court-ordered desegregated schools

and the fear of both violence and the loss of educational

quality in these same schools. These problems and others

do not present Constitutional issues within the Court’s

jurisdiction. It is not the Court’s responsibility nor its

authority to compel or guide the school system into an

easier transition. The School Board has the responsibility

to make the unitary plan work realistically to the end that

quality education is made available to every child in every

school of the system. It is the Court’s duty to see that this

responsibility is met and met in good faith with the dedica

tion necessary to make it work. Without prejudging what

may come before the Court in the future, the Court may

find that the failure to act by the School Board to correct

the deficiencies is prima facie evidence of an attempt to

reestablish the dual school system through official action or

inaction.

The Biracial Committee, appointed by this Court with

the imprimatur of the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, has

strenuously and diligently advanced the cause of making

the unitary system work realistically. Its role in the transi

Order Dated June 14, 1971

3a

tion process gains greater importance and prominence.

The Committee is the Court’s Committee to the extent that

it shall continually review the School Board’s attempts to

improve the operation of the plan and to assure that racial

discrimination does not reappear in the school system by

official state action. The Committee is the School Board’s

Committee for the purpose of continually reviewing the

operation of the plan and giving the School Board the

benefit of their findings and recommendations. The School

Board may use the services of the Committee in any way

they deem most helpful. The Court has found the Commit

tee’s recommendations and insight into the school system

to be extremely intuitive and immensely helpful and has

every confidence in their dedication and competency. The

School Board is especially urged to keep the Committee

fully informed well in advance of (a) proposed acquisition

of school sites and construction plans, and (b) contemplated

changes in attendance zones.

With this in mind, while awaiting receipt of the mandate

from the United States Supreme Court, this Court will

hold a hearing on June 18, 1971 at 3 :00 p.m. to determine

the procedure to be utilized for the future conduct of this

cause. All Intervenors not making an appearance through

counsel at this hearing will be dismissed from the cause

and no further pleadings shall be served upon them. Those

Intervenors who desire to be heard at the hearing shall

file either their objections to the proposed 1971-72 School

Board plan, to the extent that it embodies changes from the

modified plan approved by the Fifth Circuit Court of Ap

peals, (all intervenors having been served by mail on May

26, 1971) or a statement of position on or before 12:00 noon

June 17, 1971.

Order Dated June 14, 1971

4a

The Court wishes to advise all counsel that appeals in

this case will be processed in accordance with Part III of

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School District,

419 F.2d 1211 (5th Cir. 1970). No extensions of time are

to be allowed except by order of the panel of the Fifth

Circuit Court of Appeals to which the case is assigned.

While the record does not have to be reproduced by print

ing or other similar process, three legible copies shall be

filed for the use of each of the members of the panel cover

ing all matters pertinent to the issues raised on the appeal

including oral or deposition evidence, exhibits, maps, charts,

plans, proposed plans, and all such other matters as are

relevant to the issues presented. Counsel are entrusted with

the responsibility to collaborate to assure that unneeded

or unwanted portions of the record are not included. All

questions should be directed to Edward W. Wadsworth,

Clerk, Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals by referring to his

letter of May 26, 1971.

D one and Ordebed at Miami, Florida this 14th day o f

June, 1971.

Order Dated June 14, 1971

C. Clyde A tk in s

United States District Judge

cc. All counsel of record

All members of the Bi-Racial Committee

5a

Order Dated June 18, 1971

In th e

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

In and F oe th e S outhern D istrict oe F lorida

M ia m i D ivision

No. 69-1020-Civ-CA

H erbert P ate, et al.,

v.

Plaintiffs,

D ade Co u nty S chool B oard, et al.

Defendants.

By order dated June 14, 1971, this Court established a

housekeeping requirement that all Intervenors desiring to

remain as parties to this cause were required to appear

through counsel at 3 :00 p.m. June 18, 1971. The following

are those parties and their counsel who appeared at the

aforesaid hearing and are therefore entitled to remain as

parties to this action:

(1) Dade County Classroom Teachers Association

Tobias Simon, Attorney

(2) Alice Love, Carswell Washington, Margaret

Washington and American Civil Liberties Union

of Florida, Inc.

James W. Matthews and Richard Yale Feder,

Attorneys

6a

(3) Dade County Education Association

Fred Davant, Attorney

(4) Florida Board of Education

Charles Minor, Attorney

It Is T herefore Ordered and A djudged as follows:

(a) That all other Intervenors are hereby dismissed

from this cause and shall be stricken from the roll of those

entitled to service;

(b) That the Motion to Intervene and Objection and

Prayer for Opportunity to Prepare and Challenge of

Wellington Rolle is denied without prejudice to make a

detailed factual presentation which would constitute a

prima facie case of the School Board’s failure to maintain

a unitary school system;

(c) That the objections of Intervenors Alice Love, Cars

well Washington and Margaret Washington and the

American Civil Liberties Union of Florida, Inc. are denied

without prejudice;

(d) That the Statement of Position of the Intervenor,

Classroom Teachers Association, is noted and rejected but

its thrust is commended to the consideration of the School

Board;

(e) That the 1971-72 Pupil Assignment Plan of the Dade

County School Board, as adopted by the Board at its meet

ing of May 19, 1971 and filed in this cause on May 26, 1971

is hereby approved;

(f) That hereafter the School Board shall not be re

quired to petition the Court for approval of any proposed

changes in its Pupil Assignment Plan by which it desires

Order Dated June 18, 1971

7a

to improve the effectiveness of the Plan. The burden shall

be upon the present intervenors, or any other persons here

after permitted to intervene, to demonstrate to this Court

a prima facie case of the School Board’s failure to act in

accordance with the principles outlined in this Court’s

order of June 14, 1971. Jurisdiction is retained for this

limited purpose.

D one and Oedeeed at Miami, Florida this 18th day of

June, 1971.

Order Dated June 18, 1971

C. Clyde A tkin s

United States District Judge

cc. George Bolles, Esq.

Tobias Simon, Esq.

James W. Matthews, Esq.

Richard Y. Feder, Esq.

Fred Davant, Esq.

Charles Minor, Esq., Florida Board of Education

Mr. Wellington Rolle

8a

Order on Motions For Evidentiary Hearing

I n th e

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

I n and F oe the S outhern D istrict oe F lorida

M ia m i D ivision

No. 69-1020-Civ-CA

H erbert P ate, et al.,

v.

Plaintiffs,

D ade C ou nty S chool B oard, et al.

Defendants.

The Dade County Classroom Teachers Association (CTA)

and certain Intervenors have moved this Court for an evi

dentiary hearing de novo to determine whether or not the

Dade County School system is unitary. In so doing, the

movants contend that Swann v. CJiarlotte-MecMenburg

Board of Education, 39 U.S.L.W. 4437 (U.S. April 20,1971),

dictates guidelines not previously considered in earlier

rulings by this Court and the Court of Appeals for the

Fifth Circuit in which the Dade County Schools were found

to be unitary. The Supreme Court, after Swann, supra, de

nied certiorari by which the Dade County School Board

challenged these orders. 39 U.S.L.W. 3487 (U.S. May 4,

1971).

The Court has carefully considered the Swann opinion

vis a vis the orders of the district court and the Fifth Cir

cuit Court of Appeals. While no cross-bussing was ordered

9a

Order on Motions■ For Evidentiary Hearing

in the prior approvals of the plan under which the Dade

County School system is operated, there is no doubt but

that the effect of the district court order as modified by the

appellate court was to require the extensive use of bus

transportation to achieve the results directed. This Court

being of the opinion that an evidentiary de novo is not re

quired, the above motions are denied.

The Court reaffirms its earlier direction that the Biracial

Committee “ shall continuously review the school board’s

attempts to improve the operation of the plan and to as

sure that racial discrimination does not reappear in the

school system, by official state action.” Additionally, the

School Board is requested to file semi-annual reports dur

ing the school year similar to those required in United

States v. Hinds County School Board, 433 F.2d 611, 618-619

(5 Cir. 1970).

E ntered at Miami, Florida this 30th day of June, 1971.

C. Clyde A tk in s

United States District Judge

10a

Opinion of United States Court of Appeals

For the Fifth Circuit

I n t h e

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

F ob t h e F if t h C ircuit

No. 71-2338

H erbert P ate , et al.,

Plaintiffs,

v.

D ade C ou nty S chool B oard, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees,

v.

A lice L ove, Carsw ell W ashington , et al.,

Intervenors- Appellants,

D ade C ou nty Classroom T eachers ’ A ssociation, I n c .,

Intervenor-Appellant.

A P PE A L FROM T H E U N IT E D STATES D ISTR IC T COURT

FOR T H E SO U T H E R N D ISTRICT OF FLORIDA

(September 3, 1971)

Before:

B ro w n , Chief Judge,

M organ and I n graham , Circuit Judges.

P er C u r ia m :

A ffirm ed . See Local Rule 21.1

[No separate judgment was entered.]

1 See NLRB v. Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America,

5 Cir., 1970, 439 F.2d 966.

11a

DADE COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS

Racial Composition as of September 27, 1971

Exhibit 1(b)

Northeast District—Elementary Schools

School Grade White Black Total %White %Black

Bay Harbor K-6 416 0 416 100 0

Biscayne K-6 508 5 508 99 1

Biseayne Gardens K-6 761 16 777 98 2

Bryan, W. J. K-6 801 4 805 99 1

Fienberg, L. D. K-6 464 6 470 99 1

Fulford K-6 502 79 581 86 14

Gratigny K-6 643 4 647 99 1

Greynolds Park K-6 635 0 635 100 0

Hibiscus K-6 611 1 612 99 1

Highland Oaks K-6 669 4 673 99 1

Ives, Madie K-6 678 1 679 99 1

Natural Bridge K-6 289 66 355 81 19

Norland K-6 890 0 890 100 0

North Beach K-6 680 22 702 97 3

North Miami K-6 587 37 624 94 6

Norwood K-6 581 1 582 99 1

Oak Grove K-6 562 34 596 94 6

Ojus K-6 372 20 392 95 5

Parkway K-6 563 5 568 99 1

Sabal Palm K-6 958 2 960 99 1

South Beach K-6 457 12 469 97 3

Treasure Island K-6 433 3 436 99 1

Total (K-6) 13,055 322 13,377 98 2

Northeast District—Secondary Schools

School Grade White Black Total %

White %Black

Ctr. for Spec. Inst.-NE 7-12 2 9 11 18 82

Fisher, Ida M. Jr. 7-9 585 182 767 76 24

Jefferson, T. Jr. 7-9 920 147 1067 86 14

Kennedy, J. F. Jr. 7-8 1347 153 1500 90 10

Miami Beach Sr. 10-12 2005 327 2332 86 14

Miami Norland Sr. 10-12 2215 413 2628 84 16

Nautilus Jr. 7-9 1205 188 1393 87 13

Norland Jr. 7-9 1494 169 1663 90 10

North Miami Jr. 7-9 1172 149 1321 89 11

North Miami Sr. 10-12 2711 205 2916 93 7

North Miami Beach Sr. 9-11 2510 281 2791 90 10

Total (7-12) 16,166 2,223 18,389 88 12

District Total K-12 29,221 2,545 31,766 92 8

12a

DADE COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS

Racial Composition as of September 27, 1971

Exhibit 1(b)

Northwest District■—Elementary Schools

School Grade White Black Total %White %Black

Bunche Park K, 5-6 248 370 618 40 60

Carol City K-6 875 164 1039 84 16

Crestview K-6 703 8 711 99 1

DuPuis K-6 559 8 567 99 1

Earhart, Amelia K-6 644 18 662 97 3

Flamingo K-6 871 2 873 99 1

Golden Glades K-6 401 400 801 50 50

Lake Stevens K-6 612 95 707 87 13

Meadowlane K-6 789 6 795 99 1

Miami Gardens K-6 425 279 704 60 40

Miami Lakes K-6 737 0 737 100 0

Milam, M. A. K-6 550 0 550 100 0

Myrtle Grove K-6 864 195 1059 82 18

North Carol City K-6 508 429 937 54 46

North County K-6 111 1105 1216 9 91

North Glade K-6 1113 78 1191 93 7

North Hialeah K-6 781 4 785 99 1

North Twin Lakes K-6 512 0 512 100 0

Opa-loeka K-6 621 317 938 66 34

Palm Lakes K-6 579 2 581 99 1

Palm Springs K-6 799 11 810 99 1

Palm Springs N. K-6 1147 0 1147 100 0

Parkview K-4 319 226 545 59 41

Pilot House, The 1-6 27 18 45 60 40

Rainbow Park K-6 238 389 627 38 62

Scott Lake K-4 439 239 678 65 35

Twin Lakes K-6 701 0 701 100 0

Walters, Mae K-6 1064 33 1097 97 3

Total (K-6) 17,237 4,396 21,633 80 20

13a

Exhibit 1(b)

DADE COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS

Racial Composition as of September 27, 1971

Northwest District—Secondary Schools

School Grade White Black Total 70White _ 70Black

Carol City Jr. 7-9 1642 649 2291 72 28Filer, Henry H. Jr. 7-9 2011 189 2200 91 9Hialeah Jr. 7-9 1153 124 1277 90 10Hialeah Sr. 10-12 3494 9 3503 99 1

Hialeah-iViiami Lakes Sr. 9-11 1830 189 2019 91 9

Miami Carol City Sr. 10-12 1940 680 2620 74 26North Dade Jr. 7-9 232 928 1160 20 80Palm Springs Jr. 7-9 1789 0 1789 100 0Parkway Jr. 7-9 1214 456 1670 73 27Youth Oppor. Sch. No. 7-9 65 53 118 55 45

Total (7-12) 15,370 3,277 18,647 82 18

District Total K-12 32,607 7,673 40,280 81 19

North Central District—Elementary Schools

School Grade White Black Total %White %Black

Areola Lake K-3 408 538 946 43 57Blanton, Van E. K, 4-6 350 475 825 42 58Bright, James H. K-5 768 179 947 81 19Broadmoor K-3 543 485 1028 53 47Curtiss, Glenn K, 5-6 164 221 385 43 57Drew, C. R. K-6 0 902 902 0 100Edison Park K, 3-4 363 522 885 41 59Evans, L. C. K-6 0 1018 1018 0 100Franklin, Benj. K-6 661 3 664 99 1

Gladeview K, 5-6 122 291 413 30 70Hialeah K-4 522 307 829 63 37Holmes K-3 34 706 740 5 95J ohnson, J. W. 6 115 30 145 79 21King, M. L. Prim. K-2 139 200 339 41 59Lakeview K-6 680 19 699 97 3Liberty City K-6 0 829 829 0 100Little River K, 5-6 338 702 1040 33 67Lorah Park K-4 145 500 645 22 78

M. Edison Middle 6 189 231 420 45 55Miami Park K-6 878 307 1185 74 26

Miami Shores K-6 986 8 994 99 1

Miami Springs K-6 493 43 536 92 8

Morningside K-5 480 15 495 97 3

Olinda K-6 0 884 884 0 100Orchard Villa K-6 0 1274 1274 0 100Poinciana Park K-6 0 1141 1141 0 100

14a

DADE COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS

Exhibit 1(b)

Racial Composition as of September 27, 1971

North Central District—Elementary Schools (continued)

School Grade White Black Total %White %Black

Primary School “ C” K-2 106 287 393 27 73

Shadowlawn K-5 317 592 909 35 65

South Hialeah K-6 1252 6 1258 99 1

Springview K-6 588 1 589 99 1W. Little River K, 4-6 394 615 1009 39 61

Westview K-3 286 246 532 54 46Young, Nathan K, 4-6 190 279 469 41 59

Total (K-6) 11,511 13,856 25,367 45 55

North Central District—-Secondary Schools

%WhiteSchool Grade White Black Total %Black

C.O.P.E. Center 7-12 1 84 85 1 99Drew, C. R. Jr. 7-9 0 1217 1217 0 100MacArthur, D. Jr./Sr. 7-12 266 37 303 88 12Madison Jr. 7-9 642 641 1283 50 50Mann, Horace Jr. 7-9 810 357 1167 69 31Miami Central Sr. 9-12 1830 1343 3173 58 42

Miami Edison Middle 7-8 341 577 918 37 63Miami Edison Sr. 9-12 1237 1055 2292 54 46

Miami Northwestern Sr. 9-12 4 2187 2191 1 99Miami Springs Jr. 8-9 530 861 1391 38 62

Miami Springs Sr. 9-12 2977 531 3508 85 15

Westview Jr. 7-9 897 374 1271 71 29

Total (7-12) 9,535 9,264 18,799 51 49

District Total K-12 21,046 23,120 44,166 48 52

South Central District—Elementary Schools

%WhiteSchool Grade White Black Total %Black

Allapattah K, 3-5 180 888 1068 17 83

Allapattah Jr. 6 45 301 346 13 87

Auburndale K-6 915 10 925 99 1

Bethune K-3 209 432 641 33 67

Buena Vista K-2 287 135 422 68 32

Carver, G. W. K-2 281 274 555 51 49

Citrus Grove 1-6 1291 1 1292 99 1

Coconut Grove K-6 201 294 495 41 59

Comstock K-3 938 322 1260 74 26

Coral Gables K, 3-6 346 115 461 75 25

Coral Way K-6 1524 16 1540 99 1

Dade K, 4-6 253 326 579 44 56

15a

DADE COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS

Exhibit 1(b)

Racial Composition as of September 27, 1971

South, Central District—Elementary Schools ( continued)

S ch oo l G rade White B lack T o ta l

%

W h ite

%

B lack

Douglas K-3 407 898 1305 31 69

Dunbar K, 4-6 298 601 899 33 67

Earlington Hts. K-6 8 889 897 1 99

Flagler, H. M. K-6 721 16 737 98 2

Floral Heights K-6 0 843 843 0 100

Kensington Park K-6 1258 15 1273 99 1

Key Biscayne K-6 627 3 630 99 1

Kinloch Park K-6 712 22 734 97 3

Melrose K, 4-6 386 384 770 50 50

Merrick K, 3-6 358 91 449 80 20

Miramar K-3 268 303 571 47 53

Pharr, Kelsey K, 4-6 439 493 932 47 53

Riverside K, 4-6 861 608 1469 59 41

Santa Clara K-2 204 427 631 32 68

Shenandoah 1-6 1103 0 1103 100 0

Silver Bluff K-6 724 3 727 99 1

Southside 1-6 382 5 387 99 1

Sunset K, 3-6 484 147 631 77 23

Tucker, F. S. K-3 96 463 559 17 83

West Dunbar K-3 323 463 786 41 59

W. Laboratory K-6 311 91 402 77 23

Wheatley, P. 3-6 441 528 969 46 54

Total (K-6) 16,881 10,407 27,288 62 38

South

S ch oo l

Central District-—

G rade W h ite

■Secondary Schools

B la ck T o ta l

%

W h ite

%

B lack

Allapattah Jr. 7-8 377 768 1145 33 67

Brownsville Jr. 7 241 612 853 28 72

Carver, G. W. Jr. 7 311 218 529 59 41

Citrus Grove Jr. 8 893 439 1332 67 33

Coral Gables Sr. 10-12 2488 489 2977 84 16

Kinloch Park Jr. 7-9 1652 27 1679 98 2

Lee, Robert E. Jr. 8-9 406 598 1004 40 60

Merrit, Ada Jr. 7 721 474 1195 60 40

Miami Jackson Sr. 10-12 430 2142 2572 17 83

Miami Sr. 10-12 4741 264 5005 95 5

Ponce de Leon Jr. 8-9 909 385 1294 70 30

Shenandoah Jr. 7-9 1928 4 1932 99 1

Washington, B. T. Jr. 9 745 447 1192 62 38

Total (7-12) 15,842 6,867 22,709 70 30

District Total K-12 32,723 17,274 49,997 70 30

16a

School

Banyan

Blue Lakes

Coral Park

Coral Terrace

Cypress

Emerson

Everglades

Fairchild, D.

Fairlawn

Flagami

Greenglade

Kendale

Kenwood

Lee, J.R.E. Ctr.

Leewood

Ludlam

Martin, F.C.

Olympia Heights

Roekway

Royal Palm

Seminole

Silver Oaks

Snapper Creek

South Miami

Sunset Park

Sylvania Heights

Tropical

Village Green

Vineland

Exhibit 1(b)

DADE COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS

Racial Composition as of September 27, 1971

Southwest District-Elementary Schools

Grade White Black Total %White %Black

K-6 704 0 704 100 0

K-6 1041 0 1041 100 0

K-6 898 0 898 100 0

K-6 802 2 804 99 1

K-6 841 0 841 100 0

K-6 942 0 942 100 0

K-6 875 1 876 99 1

K-6 542 78 620 87 13

K-6 831 0 831 100 0

K-6 811 2 813 99 1

K-6 738 1 739 99 1

K-6 558 1 559 99 1

K-6 799 4 803 99 1

K- 1 59 60 2 98

K-5 733 210 943 78 22

K-6 401 248 649 62 38

K-6 581 355 936 62 38

K-6 840 2 842 99 1

K-6 818 1 819 99 1

K-6 966 6 972 99 1

K-6 972 2 974 99 1

1-6 2 7 9 22 78

K-6 797 0 797 100 0

K-6 475 171 646 74 26

K-6 851 8 859 99 1

K-6 741 6 747 99 1

K-6 1014 12 1026 99 1

K-6 906 2 908 99 1

K-5 525 159 684 77 23

21,005 1,337 22,342 94 6Total (K-6)

17a

Exhibit 1(b)

DADE COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS

Racial Composition as of September 27, 1971

Southwest District—Secondary Schools

School Grade White Black Total %White %Black

Ctr. for Spec. Inst.-S.W. 7-12 1 2 3 33 67

Glades Jr. 7-9 2013 4 2017 99 1

Miami Coral Park Sr. 10-12 2711 0 2711 100 0

Miami Killian Sr. 9-12 2709 734 3443 79 21

Richmond Heights Jr. 7-9 943 910 1853 51 49

Riviera Jr. 7-9 2095 5 2100 99 1

Rockway Jr. 7-9 1838 0 1838 100 0

Silver Oaks 7-12 23 54 77 30 70

South Miami Jr. 7-9 1023 246 1269 81 19

South Miami Sr. 10-11 1306 126 1432 91 9

Southwest Clinical Sch. 7-9 48 3 51 94 6

Southwest Miami Sr. 10-12 3132 75 3207 98 2

West Miami Jr. 7-9 1894 0 1894 100 0

Total (7-12) 19,736 2,159 21,895 90 10

District Total K-12 40,741 3,496 44,237 92 8

South District—Elementary Schools

School Grade White Black Total %White %Black

Air Base K-6 1170 101 1271 92 8

Avocado K-6 700 18 718 97 3

Bel-Aire K-4 285 237 522 55 45

Caribbean K-6 1092 51 1143 96 4

Colonial Drive K-6 530 216 746 71 29

Cooper, N. K. K-3 272 364 636 43 57

Coral Reef K-5 764 188 952 80 20

Cutler Ridge K-6 1018 19 1037 98 2

Florida City K-2 154 336 490 31 69

Goulds K-6 41 318 359 11 89

Gulfstream K-6 592 22 614 96 4

Howard Drive K-5 556 171 727 76 24

Leisure City K-6 1066 9 1075 99 1

Lewis, A. L. K, 4-6 142 394 536 26 74

Miami Heights K-6 884 80 964 92 8

Moton, R. R. K, 5-6 180 314 494 36 64

Naranja K-6 281 304 585 48 52

Palmetto K-5 559 179 738 76 24

Perrine K-4 248 145 393 63 37

Pinecrest K-6 859 0 859 100 0

18a

Exhibit 1(b)

DADE COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS

Racial Composition as of September 27, 1971

South District—Elementary Schools (continued)

School Grade White Black Total White Black

Pine Villa K-6 68 1072 1140 6 94

Redland K-6 676 97 773 87 13

Redondo K-6 471 17 488 97 3

Richmond K-6 177 488 665 27 73

South Miami Hts. K-6 877 41 918 96 4

West Homestead K, 3-6 216 569 785 28 72

Whispering Pines K-6 779 1 780 99 1

Total (K-6) 14,657 5,751 20,408 72 28

South District—Secondary Schools

S ch o o l G rade W h ite B lack T ota l

%

W h ite

%

B lack

Cutler Ridge Jr. 7-9 1535 417 1952 79 21

Homestead Jr. 7-9 1007 650 1657 61 39

Mays Jr. 7-9 1189 701 1890 63 37

Miami Palmetto Sr. 10-12 3228 419 3647 89 11

Palmetto Jr. 7-9 1677 33 1710 98 2

Redland Jr. 7-9 619 180 799 77 23

South Dade Sr. 10-12 1593 923 2516 63 37

Total (7-12) 10,848 3,323 14,171 77 23

District Total K-12 25,505 9,074 34,579 74 26

SYSTEM-WIDE TOTAL K-12 182,029 63,213 245,242 74 26

ME1LEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C. 219