Cooper v. Aaron Brief for the Petitioners

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1958

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Cooper v. Aaron Brief for the Petitioners, 1958. b4457f48-ae9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1ee32ffa-f3eb-43db-9ac6-e80a1f8a2f08/cooper-v-aaron-brief-for-the-petitioners. Accessed February 04, 2026.

Copied!

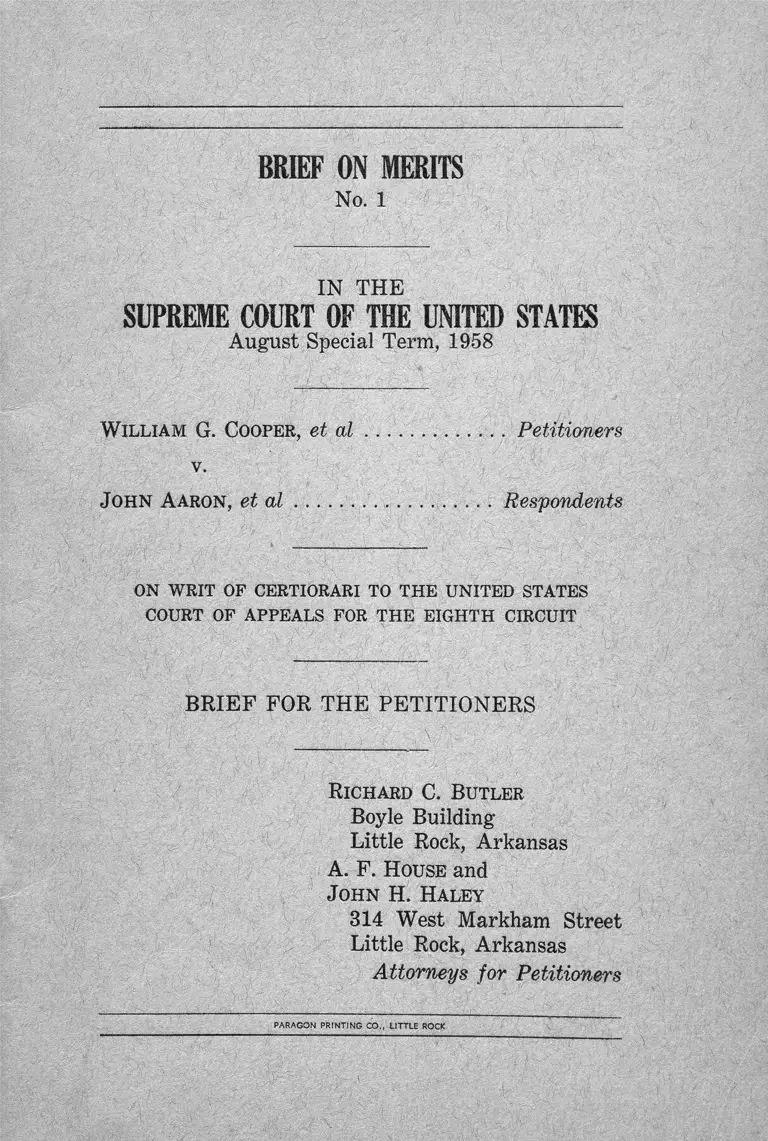

BRIEF ON MERITS

No. 1

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

August Special Term, 1958

W i l l i a m G . C o o p e r , et a l ....................... .. Petitioners

v.

J o h n A a r o n , et a l ............................ Respondents

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR THE PETITIONERS

R ic h a r d C . B u t l e r

Boyle Building

Little Rock, Arkansas

A. F . H o u se and

J o h n H . H a l e y

814 West Markham Street

Little Rock, Arkansas

Attorneys for Petitioners

PARAGON PRINTING CO ., LITTLE ROCK

INDEX

Page

Opinion Below ______________________________________________ 1

Jurisdiction _______________________ ___________ __________ i—— 1

Questions Presented - ----------------------------------------- --------------------- 2

Constitutional Amendment Involved _____ _______ _____ ______ 2

Statement __________________________._________ ________________ 3

Summary of Argument _____________________________ 7

Argument:

I. The Decision of the District Court is in the

Public Interest and is in Accord with the Spirit of

the Second Brown Decision ___ 10

II. Effect of Opposition by Community and by

State Government _________ __________________________ 19

III. Responsibility for Enforcement ______________________ 27

IV. This District is Entitled to Relief _______ 36

Conclusion _____________________________________________________ 38

Appendix ____ 39

INDEX—(Continued)

CITATIONS

Page

Cases:

Aaron v. Cooper, 143 F. Supp. 855 (E. D. Ark.), aff’d

243 F. 2d 361 (C.C.A. 8th) ------------------------------------------- 3

Allen v. County School Board of Prince Edward County,

Virginia, 249 F. 2d 462 (C.C.A. 4th) ------------------------- 25

Brewer v. Hoxie School District, 238 F. 2d 91 (C.C.A. 8th) — 34

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483; 349 U.S. 294 ------10-19

Cumming v. Board of Education, 175 U.S. 528 ------------------ 15

Faubus v. United States, 254 F. 2d 797 (C.C.A. 8th) ------------ 35

Giles v. Harris, 189 U.S. 475 ------------------------------------------- 33

Hoxie School District v. Brewer, 137 F. Supp. 364

(E. D. Ark.) ---------------------------------------- :■--------------------- 14

Jackson v. Rawdon, 235 F. 2d 93 (C.C.A. 5th) --------------------- 21

Kasper v. Brittain, 245 F. 2d 92 (C.C.A. 6th) --------------------- 34

Orleans Parish School Board v. Bush, 242 F. 2d 156

(C.C.A. 5th) __________________________________________ 23

School Board of City of Charlottesville, Va. v. Allen,

240 F. 2d 59 (C.C.A. 4th) ---------------------------------------- 23

Screws v. United States, 325 U.S. 91 ---------------------------------- 32

Thomason v. Cooper, 254 F. 2d 808 (C.C.A. 8th) __________ 35

United States v. Williams, 341 U.S. 70 ---------------------------- 32

Miscellaneous:

Amendment 44 to the Constitution of Arkansas __________ 16

Arkansas Statutes Annotated 80-1519-1524; 80-1535; 80-539,

6-801 (1947 & Supp. 1957) __________________________ 16

Blaustein & Ferguson, Desegregation and the Law _______18,32

Journal of Public Law, Emory University School of Law,

Vol. 3, No. 1 __________________________________________13,42

Negro Citizens in the Supreme Court of the United States,

52 Harvard Law Review 832 (1939) __________________ 32

Sumner, Folkways ------- — ______________ __________________ 13,42

BRIEF ON MERITS

No. 1

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

August Special Term, 1958

W il l i a m G. C o o p e r , et oX ......................... PetitioneTs

v.

J o h n A a r o n , et a l .................................... Respondents

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR THE PETITIONERS

OPINION BELOW

The opinion of the Court o f Appeals is as yet un-

reported. It and the District Court opinion are ab

stracted in the appendix to Respondents’ brief filed

prior to the August 28 hearing.

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was en

tered August 18, 1958. On August 28, 1958, by order

of this Court, the Petitioners were given leave to file

petition for a Writ of Certiorari not later than Sep

tember 8, 1958. The petition was filed September 8,

1958. The jurisdiction of this Court rests on 28 U.S C

§ 1254(1).

2

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

The District Court found that the school board’s

plan of desegregation has resulted in severe impair

ment of the educational program and an overall in

tolerable situation because of overt resistence and op

position by the state government, students, parents,

organized groups, and segments of the community.

The questions presented are:

(1) Whether a court of equity may postpone

the enforcement of the respondents’ constitutional

rights if the continued enforcement thereof will result

in an intolerable situation and great disruption of the

educational process to the detriment of the public in

terest, the schools, and the students including the re

spondents.

(2) Whether a school district has a duty and

obligation, by invoking extraordinary legal processes

and otherwise, to quell violence, disorder and organized

resistance to desegregation.

CONSTITUTIONAL AMENDMENT INVOLVED.

Amendment 14 to the Constitution of the United

States, Section 1, provides:

“ All persons born or naturalized in the

United States, and subject to the jurisdiction

thereof, are citizens of the United States and

of the state wherein they reside. No state shall

make or enforce any law which shall abridge

the privileges or immunities of citizens of the

United States; nor shall any state deprive any

person of life, liberty, or property, without due

process of law; nor deny to any person within

its jurisdiction the equal protection of the

laws.”

3

STATEMENT

Little Rock School District, hereinafter referred

to as “ the District” , after the first Brown de

cision and b e f o r e the s e c o n d Brown de

cision, evolved a tentative Plan of Integration. The

good faith of the District has never been chal

lenged. The Plan contemplated integration in the

senior high schools of the District during the 1957-

1958 term, later in the junior high schools, and still

later in the grade schools. It was assumed that the

plan would require a period of about seven years.

The NAACP was not satisfied with the Plan or

the time schedule and caused a suit to be filed con

tending that complete integration should be required

overnight. The District Court and the Circuit Court

of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit approved the seven

year plan. See Aaron v. Cooper, 143 F. Supp. 855

(E.D. A rk .) ; 243 F. (2d) 361 (C.C.A. 8th).

The District commenced functioning under the

Plan in September, 1957, and it operated during the

1957-1958 term with disastrous results. With an

experience which t a u g h t the futility of imme

diate operation of the plan without sacrificing

those values uppermost in the minds of educa

tors, the District filed a Petition asking that the

District Court, in the exercise of its discretion,

postpone operation under the Plan for a period

of two and one-half years. On undisputed testimony

as to what had happened, the District Court concluded

that the education of all pupils was being harmed and

in the public interest an interruption in operations

should be permitted.

4

Among the express findings of the District

Court, as contained in its Memorandum Opinion, are

the following:

“ There were many incidents within the

school consisting of slugging, pushing, tripping,

catcalls, and abusive language.

“ There was tension among the students

and teachers which resulted in the lowering of

the standards of education.

“ Teachers were physically exhausted and

frustrated.

“ On forty-three occasions there were

threats that the school building would be de

stroyed by dynamite. Each threat necessitated

the searching of the premises.

“ School property was destroyed by acts of

vandalism and school funds were expended for

replacements which necessitated reducing ex

penditures for necessary maintenance.

“200 pupils were suspended and two were

expelled.

“ Extra-curricular school activities were

diminished.

“ Troops moved around and within the

school building distracting the pupils from

their school work.

“ There was ‘chaos, bedlam and turmoil’

from the beginning.

“ Newspaper articles and circulars have

been published and distributed condemning the

principle of integration, abusing the school of

ficials, and telling the residents of the district

that integration could be avoided.

“ School officials were threatened with

violence.

5

“ A serious financial burden has been cast

on the District in coping with the problems en

countered.

“ The State of Arkansas, instead of bring

ing its laws into conformity with the rule of

Brown v. Board of Education, has adopted a

constitutional amendment and enacted several

statutes which destroy in various ways the pro

cess of integration.

“ Education has suffered and will contin

ue to suffer.

“ The Police Department of Little Rock is

unable to furnish adequate protection.

“ Federal troops will be required again

next year.

“ The situation is intolerable.”

Although not mentioned by the District Judge,

the record reveals other conditions which added to the

intolerability of the situation:

Mobs formed and overtly interfered with opera

tions under the Plan. Some were arrested by the City

Police but later discharged.

Vicious circulars were distributed condemning

the District Court, the Supreme Court of the United

States and the school officials who recognized the su

premacy of Federal Law.

Masters of rhetoric were imported who told the

residents of the District that the Governor of Arkansas

could legally prevent integration and suggested that

the shedding of blood was permissible in order to main

tain segregation.

Many of those who formed into mobs were identi

fiable, but none has been punished by the District

Court or any Federal law enforcement agency.

6

Some of the Negro pupils who were abused made

reports to the United States District Attorney. The

Attorney General of the United States made a public

statement to the effect that no one who had interfered

with operations under the Plan would be prosecuted.

A columnist writing for one of the local papers

constantly supports the doctrine that the Fourteenth

Amendment was not legally adopted and that the de

cision of this Court in Brown V. Board of Education

is not the law of the land.

Vulgar cards, critical of the school officials, were

given by adults to school children for distribution

within the school building.

Pupils who became involved in disciplinary in

vestigations are being guided by adults.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation made a full

and comprehensive report of the Little Rock situation,

and although the school officials discussed with the

F.B.I. several times the matter of using the report to

arrive at a decision as to feasibility of the use of in

junctive measure, the report was not made available to

them, nor was the report utilized by the Department

of Justice since it dropped plans to prosecute agitators.

The legislative, executive, and judicial depart

ments of the state government opposed the desegre

gation of Little Rock schools by enacting laws, calling

out troops, making statements villifying Federal law

and Federal courts, and failing to aid enforcement

through judicial processes.

On the basis of its findings, the District Court

held that the request for a postponement was made in

good faith and was manifestly justifiable; that severe

7

impairment of the educational program and of the

welfare of the students and the community would re

sult were the postponement not granted; that the in

herent powers of equity and the spirit of the second

Brown decision dictated that the school district be al

lowed to operate its schools on a segregated basis for

a time without being considered in contempt of court.

The Circuit Court of Appeals for the Eighth Cir

cuit agreed with the findings of the District Court that

the evidence is appalling but that great additional ex

pense, disruption of normal educational procedures,

tension and nervous collapse of the school personnel,

turmoil, bedlam, and chaos, are not a legal basis for

suspension of the plan since this would be an accession

to the demands of insurrectionists.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The argument of petitioners is reflected by the

questions presented. First, where a school board has

made a prompt start toward desegregation and has

continued throughout to exercise good faith, severe

impairment of the educational system both present

and prospective because of desegregation entitles the

school district to a postponement regardless of the

source and motivation of the destructive forces. The

second Brown decision was so construed by the District

Court.

There are thousands of school districts in the

South that have not made a step toward desegregation.

In their repose these districts are conducting educa

tional programs without harrassment of any sort al

beit constitutional rights declared by the Brown de

cisions are being delayed. Thus it would be the

height of irony if the Little Rock School District, hav

ing made the start in good faith, were denied this post

8

ponement at the expense of the entire educational pro

gram at the high school level. The attorneys for the

respondents have, at every stage, tacitly conceded the

existence of the situation as found by the District

Court, but have ignored and skirted the equities of the

school district and of the thousands of students, parents

and teachers. Moreover, it is the judgment of the

District Court and the school board that the respond

ents’ best interests would be served by enrolling them

on a segregated basis, and no one is in a better posi

tion to determine this.

The Solicitor General, in his argument before this

Court on August 28,1958, stated that a court of equity

does not ask people to do things that are beyond their

power. He agreed that the school board has had a

difficult time of it. He further stated that in his

opinion the Broivn decision does not extend to destruc

tion of institutions in order to grant private rights.

Apparently the position of the Government is that if

the school board had done everything possible and still

the merits of the case called for a stay, then the grant

ing of it would be reasonable; but that the school board

could have done more and that the situation is difficult

but not impossible. This would seem to be a substitu

tion of judgment for that of the school board and the

District Court.

The Circuit Court of Appeals and this Court

should not substitute its judgment for that of the

District C o u r t unless it is obviously without

foundation in fact. Here the school board determined

and the District Court found that maintenance o f edu

cational standards was impossible under the circum

stances. There was ample evidence in support of this

determination, and the District Court further found

9

that the school board and personnel had done all they

could to prevent total disruption of the schools.

It is to be questioned whether a court has the

practical power to deal with opposition such as is here

encountered. But if it does, certainly the method

should not be that of placing the school board in the

undeserved position of being the sole bastion of

Federal authority until it destroys itself. It may

be that mass violent opposition can be dealt with

through the District Court with the assistance of

the Department of Justice and the respondents,

but until unlawful force, v i o l e n c e and official

state resistance subside through passage of time or as

a result of the exercise of the powers of the judicial

processes, the school district must be allowed its re

quested postponement.

Finally, the respondents and the Solicitor General

have argued, and the Circuit Court of Appeals has

suggested, that the school board was obligated to pur

sue the forces of violence arrayed in the community.

This the school board cannot do, and this should not

be expected of it. The school board is dedicated only

to furtherance of the educational program and adher

ence to law and order. It is under compulsion of court

order to desegregate, but it is not and should not be a

militant combatant of segregationist forces. Rather,

this should be an obligation of the respondents and the

Department of Justice, neither of whom has acted.

10

ARGUMENT

I

The decision of the District Court is in the public in

terest and is in accord with the spirit of the second

Brown decision.

The District Court found that continuation of de

segregation in the immediate future would place the

District in an intolerable situation. It found that the

educational program was being, and would continue

to be, greatly impaired and endangered to the detri

ment of the public. It further found that the District

had done all it could toward alleviating the situation.

Findings of fact by lower tribunals are not lightly dis

turbed. Especially should these findings of fact, based

as they are upon overwhelming evidence, be unassail

able in the light of the Brown decision. The determi

nation of the reasonableness of the time and manner

in which a school district implements the prescriptions

of the Brown decision rests in the sound discretion of

the local District Judge. Virgil Blossom, Superinten

dent of the District, gave his interpretation of “ all de

liberate speed” couching it in terms of the history of

the Negro in this country and the present considera

tions of maintenance of educational standards and the

public interest (R .295-299):

Q. Did the term used by the United States Supreme

Court, “ deliberate speed” , gain your attention

and did you try to determine what was meant by

it?

A. Yes, sir, very materially, to this extent, Mr.

Butler. The Negro as a race came to this coun

try in 1619. They came in chains, as slaves.

They stayed in that, and, as far as I could study

it, you would class that as the first period in

the history of the United States, and they stayed

from 1619 until 1865_, which is nearly two and

three-quarters centuries, and that is one period

in their march for civil rights of their develop

ment. The second period began in 1865 and

they stayed in this second period until 1896

when we had Plessy V. Ferguson. That is 31

years. Now, in this period they had their free

dom. They did not have economic or political or

any other type of position to any extent. Then

coming out of that period into what I would

call the third one, from 1896 until 1954, and I

would just label that separate but equal. Now,

they stayed in that 58 years, and when you look

at the problems and the complexities in this

thing and recognize that many places separate

but equal is no way near a reality. Many

places in the Southland they still do not ap

proach separate but equal, but in Little Rock,

Arkansas, they did. I am not arguing the sep

arate but equal philosophy. I am trying to

state what history tells us in terms of a two and

a half year request for delay, and that is the

third period, and when we account for the fact

that there are three periods, one taking nearly

three centuries, another 31 years and another

58 years, and recognizing that there is one group

that says we are going to have it all now and

another that says we are never going to have

it, you put the horns of the dilemma in proper

perspective with the School Board right in the

middle, and it is a difficult thing; and then you

come to May 17, 1954, and we look at it today,

June 4th, 1958, and you compare that period

of time as compared to either one of the pre

vious three periods I have outlined, and you

wonder how fast, in terms of history, anyone

can expect a change in cultural patterns, and

you have to ask yourself, well, this district

which was actually separate but equal, and

could so be defended prior to May 17, which

12

has nothing to do with this, except in terms of

the two and a half year delay. In view of what

we know has happened this year, it just magni

fies and intensifies the problem, and in terms

of that period of time that I have outlined it is

a very small segment compared to either one

of the previous three periods and, at the same

time, when we look at the slowness with which

local laws are being moved out of the way by

courts, and state courts in this instance, if you

please, the problem is certainly magnified, and

I would not be smart enough to say that two

and a half years, or three and a half, or two,

is a long enough period of time.

But when you look at it in terms of the

time required to change cultural patterns, the

slowness with which local laws are moved out

of the way, and recognize that the fact that the

Court spelled out in its “ all deliberate speed”

philosophy, certain logical legal reasons for

delay, one of which is “ local laws” . It tells me

that the Court anticipated the fact but they made

a mistake. They anticipated that local and state

governments would voluntarily fall in line and

move those laws out of the way, but to me the

Supreme Court was in error in their judgment.

Southern states have not done that. Instead of

moving them out of the way, daily they are

creating more, which adds to this dilemma, and

until that has happened, it seems to me that his

tory spells out exactly what the Supreme Court

meant by “ all deliberate speed” , and it spells out

to me a varied studied judicial approach that

each place is different and it may be different

this year than last year or it may even be next,

but they recognize it, and public interest is an

other thing, and I am sure that they have no

idea of down-grading anybody’s educational

program. Now all of that was considered very

deliberately and judiciously in terms of asking

for two and a half years, and when you look

13

at the size of the problem involved and look at

what history seems to tell us, then two and a

half years looks like a very short time to me.

In the second Brown opinion (349 U.S. 294), with

respect to the spheres in which school districts and the

District Courts should operate, this was said:

“ Full implementation of these constitu

tional principles may require solution of varied

local school problems. School authorities have

the primary responsibility for elucidating, as

sessing, and solving these problems; courts will

have to consider whether the action of school

authorities constitutes good faith implementa

tion of the governing constitutional principles.”

The mores of the people in the realm of law en

forcement are powerful. In the Appendix we have

quoted from “ Folkways” by William Graham Sumner

and articles by Ruppert Vance, Wiley H. Davis and

W. E. Gauerke and Mozell Hill which appeared in the

Journal of Public Law, Emory University Law School,

Vol. 3, No. 1, Spring, 1954, Edition.

As a rule laws follow the crystallization of the

mores. In that pattern law enforcement is easy, as

public sentiment approves enforcement. When laws

are in advance of the mores, then in order to have ef

fective enforcement there must be (a) an ability to

understand the purpose of the law, a well developed

sense of self-discipline, and a willingness to cancel an

existing attitude for societal benefits; or (b) the gov

ernment which creates the new law which is not in step

with the mores must, by an application of compulsive

power, be able to force the people to accept its principle

regardless of their attitudes. If both conditions for

enforcement are lacking, the results are bound to be

14

turmoil, recalcitrance, and a rapidly developing dis

respect for all law.

The mores are different in different places, the

variation being due to the environments under which

they develop. The Brown decision is more or less

apace with the mores in some of the northern states.

In the southern states it was far out in front, and its

rule has provoked wide-spread and intense hostility to

the members of the Negro race, the Supreme Court

of the United States, the Federal Government, and all

school officials who believe it is their duty to carry out

its mandate. Judge Reeves who presided in Hoxie

School District V. Brewer, 137 F. Supp. 364 (E.D.

Ark.), was aware of the actuality of the problems

springing from the mores. He said:

“ Judges should not be unmindful of the

customs, mores and sentiments that may have

existed among people and in communities over

a long period of years and that a sudden over

turning or reversal of such habits and customs

by an apparent outside force or authority would

at first blush be provocative. Under such cir

cumstances logic, and not emotion, should dom

inate and prompt action. If the change is

proper and just, then all should submit without

delay. If it be deemed unjust and improper,

then orderly processes should be observed to

reestablish the custom.”

It seems to us that the language in Brown shows

an awareness of the probable development of difficul

ties and insistence that the remedy of enforcement was

to be kept flexible so as not to place the District Courts

in the position of ordering what they could not enforce.

Reference is made to the “ varied local school prob

lems” . When a school district grapples with one of

the problems, the courts will have to determine whether

15

it is acting in good faith. In most instances good

faith can be determined by answering the question as

to whether the problem is real or imaginary. It is

said that “ once a start has been made” additional time

may be requested to carry out the ruling in an “ ef

fective” manner. Here a start was made. Due to

conditions beyond the control of the District, its efforts

effectively to integrate have been thwarted. What is

the meaning of the word “ effective” as used in the

opinion? Is effectiveness to be tested only by the

speed with which Negro pupils are enrolled in inte

grated schools or does the word connote a transition

which will give to the Negro pupils their constitutional

rights with as much speed as is reasonably compatible

with the preservation of the existing standards of

public education.

In the case of Gumming v. Board of Education,

175 U.S. 528, 544-545, Justice Harlan denied an in

junction because “ the result would only be to take

from white children educational privileges enjoyed by

them, without giving colored children additional op

portunities for the education furnished in h i g h

schools.” In the Little Rock situation, the negro stu

dents’ high school education will not be interrupted

and in fact they will be spared the predictable mental

torment and physical danger that would accompany

attendance at Central High School at the present time.

On the other hand, Judge Lemley’s decision is not

reinstated, the school board for the reasons reflected

in the findings of the district court will be unable to

operate Central High School on an integrated basis

under conditions as they now exist in Little Rock.

Perhaps the matter of greatest importance will be the

irreparable harm done to the education of 2,000 stu

16

dents at Central High School and more than 21,000

students throughout the Little Rock School District.

It is said that the courts may consider problems

relating to “ administration . . . arising from the . . .

revision of local laws . . . which may be necessary in

solving the foregoing problems.” The revision there

contemplated was one which would conform local laws

to the rule of Brown. Here the revision has gone in

reverse of what was intended. Amendment 44 to the

Constitution of Arkansas was adopted in 1957. It

commands the General Assembly to oppose by every

c o n s t i t u t i o n a l method the “ unconstitutional

d e c i s i o n of Brown v. Board of Education.'”

As ludicrous as its language may appear to this Court

from a legal standpoint, it illustrates the spirit in

which the suggestion to revise has been accepted. The

following statutes have been enacted or adopted by

the people to impede the process of integration:

The Pupil Assignment Law, Sections 80-

1519 to 80-1524, Arkansas Statutes (1947).

No compulsory attendance, non-segregated

schools, Section 80-1535, ib.

Employment of legal counsel to resist in

tegration, Section 80-539, ib.

Sovereignty Commission, Section 6-801, ib.

At its special session commencing August 26,

1958, the Arkansas legislature passed a raft of bills

which allow the governor to close schools integrated

by court order where there is some opposition; allow

transfer of students from integrated schools to segre

gated schools as a matter of right; allow attendance at

segregated classes if desired and as a matter of right;

permit retaliation against school boards by means of

17

recall; and so forth. The governor has not yet signed

the bills.

The heart beat of the educational system is found

in the area of administration and the opponents of

integration, realizing this, aim at the disruption of

the administrative department. Administration is

concerned with teacher qualifications, finances, pro

tection of school property, discipline, pupil responsive

ness, scholastic opportunities, etc., etc. I f a timely re

vision of local laws was by this Court considered an

important factor, surely the twisted revision which

has occurred in Arkansas was a factor to be considered

by the District Court in determining whether the plan

first adopted was workable and, if not, whether a rea

sonable modification was appropriate.

Unable to predict what problems would arise, this

Court said the rule of equity should be applied in in

tegration suits. From the opinion:

“ In fashioning and effectuating the de

crees, the courts will be guided by equitable

principles. Traditionally, equity has been char

acterized by a practical flexibility in shaping

its remedies and by a facility for adjusting and

reconciling public and private needs. These

cases call for the exercise of these traditional

attributes of equity power. At stake is the

personal interest of the plaintiffs in admission

to public schools as soon as practicable on a

nondiscriminatory basis. To effectuate this in

terest may call for elimination of a variety of

obstacles in making the transition to school

systems operated in accordance with the con

stitutional principles set forth in our May 17,

1954, decision. Courts of equity may properly

take into account the public interest in the

elimination of such obstacles in a systematic

and effective manner (emphasis supplied).

18

Having said that the principles of equity are to

control and that “ practicable flexibility” in the ad

justing and reconciling of public and private needs

is one of the traditional functions of equity, we as

sume this Court meant that those tests should be

applied not only at the start of integration but

throughout its entire course and until the supervisory

jurisdiction of the particular court is ended with a

completely integrated school system. To argue that

because a start is made the District is frozen to the

original schedule which, due to the development of

unanticipated conditions, is found to be no longer

practical is to do violence to any reasonable concept

of flexibility.

The phrase “with all deliberate speed” repels any

idea of precipitancy in total disregard of the con

sequences. The following is taken from “ Desegrega

tion and the Law” , a book written by Albert P. Blau-

stein and Clarence Clyde Ferguson, Jr. (1957), mem

bers of the faculty of Rutgers University Law School:

“ No words in the school segregation cases

have created more confusion or caused more

comment than the simple phrase, ‘with all de

liberate speed’ . Yet, vague as these words

may appear, they were not tossed carelessly

into the 1955 opinion just to improve literary

style or sentence structure. On the contrary,

as Justice Minton told the press shortly before

his retirement, these words were the result of

Jong and careful consideration’ . Embodied in

the phrase ‘with all deliberate speed’ is a defi

nite rule of law. But it is a peculiar rule of

law in that it is designed to permit so much

flexibility in its application. It is a rule which

causes decisions to vary from court to court

and from case to case. And it was for pre

cisely this reason that it was employed in

19

Brown v. Board of Education. 'With all delib

erate speed’ was utilized as a term of art, em

powering the lower courts to adjust the impact

of the decision in light of local governmental

conditions” (pp. 218-219) (emphasis supplied).

Here the District Court was acting within the

area of permissive discretion when the impact of the

Brown decision was adjusted in the light of local

governmental conditions.

II

EFFECT OF OPPOSITION BY COMMUNITY AND BY

STATE GOVERNMENT

It is the position of the District that where the

educational program is imperiled and greatly im

paired because of the current operation of a plan of

desegregation, then in the public interest it is en

titled to suspend for a time the operation of schools

on an integrated basis. The nexus of the District’s

case is the practical impossibility of continued opera

tion on a desegregated basis. The motives and actions

of third parties are not material to the question of

whether or not the Little Rock school system should

be effectively destroyed by court order.

To illustrate, let us suppose that a drayman is

ordered by a court to proceed from town A to town

B. In transit he must pass over a bridge spanning

a chasm. The bridge is destroyed before he can

traverse it. The bizarre position of the Circuit Court

of Appeals and the Respondents is that if the bridge

is destroyed by accident or somesuch probably the

drayman should be allowed to halt his journey until

reconstruction of the bridge; but if the bridge is

maliciously destroyed by a third party in order to

frustrate the orders of the Court, then the drayman

20

must be forced to plod on his journey and over the

brink of the chasm to his fate.

The Solicitor General has made substantially the

same argument as that of the Respondents, leavened,

however, by the concession that institutions may not

be destroyed in order to enforce private rights. In

fact the District comes within the scope of the latter

premise, and the District Court so found. The re

mainder of the brief of the Solicitor General is di

rected to responsibility for enforcement and to an

effort to go behind the findings of the District Court

and argue the facts. To traverse these questions of

fact would unnecessarily lengthen the brief but two

misstatements should be corrected. On page 15 of

the Solicitor General’s brief it is stated that the

active instigators are limited in number. To the con

trary, they are legion; they represent the great mass

of the people and the state government as well. And

on page 17 it is stated that only twenty-five students

were interfering with the plan. In fact more than

two hundred students were suspended and many more

were not apprehended.

The equities of the public, the students, and

the District have been hastily dismissed by the

Circuit Court of Appeals and the Respondents. But

this is the foremost consideration for to do other

wise in this situation would be to establish a policy

of consigning the handful of southern school districts

conforming to law and order to the role of martyrdom

on the public altar.

The several cases discarding public opposition as

a ground for postponement have no relevance to this

situation for only a threat existed, not devastating

21

results. It is the results and consequences that en

title the District to relief.

The District Court, in its opinion, said:

“ The opposition to integration in Little

Rock is more than a mental attitude.”

In that terse finding the rule of Jackson v. Raw-

don, 235 F. 2d 93 (C.C.A. 5th), and its followers

is set apart and catalogued as one which has applica

tion only in the preliminary stages of a judicially en

forced integration. Nathaniel Jackson and others

filed suit against a Texas school district in 1955. At

the hearing the school officials offered only alibis

which showed conclusively that there were no adminis

trative problems confronting them. The following

excerpts are taken from the opinion:

“ * * * plaintiffs’ claims by developing that

there were no administrative difficulties which

had to be overcome in order to admit the plain

tiffs to the Mansfield High School but only, as

clearly shown by the testimony of R. L. H uff

man, the superintendent, a difficulty arising

out of the local climate of opinion, requiring

the board, in its opinion, to discriminate against

plaintiffs by denying them access to the only

high school in Mansfield, while permitting

white children to attend it. * * *

“ We think it clear that, upon the plainest

principles governing cases of this kind, the de

cision appealed from was wrong in refusing to

declare the constitutional rights of plaintiffs

to have the school board, acting promptly, and

completely uninfluenced by private and public

opinion as to the desirability of desegregation

in the community, proceed with deliberate

speed consistent with administration to abolish

segregation in Mansfield’s only high school and

22

to put into effect desegregation there” (pp.

94-96).

The District was never dominated by private or

public opinion. It received criticism from both avid in-

tegrationists and segregationists from the beginning,

but it steadily went forward. There has been

only one pause, and that was justifiable in the think

ing of any rational human. When the Governor of

Arkansas unexpectedly surrounded C e n t r a l High

School with troops in order to prevent the entry of

Negro pupils, the situation was bristling with danger

and solely to prevent injury to the Negro pupils the

District caused a notice to the published in a local

paper requesting them not to attend on the opening

day. That decision was made late in the night. The

next day the District, by petition, reported its action

to District Judge Davies, in Arkansas on temporary as

signment, and asked whether the notice should be

rescinded. The District Court ordered that it be

rescinded, and it was rescinded. A little later,

when mobs were milling about the school premises,

tension had almost reached the breaking point and a

race riot was in the making, the District asked for

a “ temporary” postponement until calmness could be

restored, pointing out in its petition that it was im

possible to teach in an environment of such turmoil.

Judge Davies labeled the petition and the proof

as being “ anemic” , and that utterance did much to

increase the difficulties of the District. The District

continued its efforts to operate an integrated school,

and at last it concluded that conditions were such

that it should again ask the Court to decide whether

operations under the Plan should be continued, and

it then filed the petition which is here under consider

ation. This District has never declined to go forward.

It has submitted its proof to a Federal Court, and

23

that Court, in the exercise of its discretion, has said

that under existing conditions the District should not

be required to proceed.

In School Board of City of Charlottesville, Va. v

Allen, 240 F. 2d 59 (C.C.A. 4th), the trial court

found:

“ They have given no evidence of any will

ingness to comply with the ruling o f the Su

preme Court at any time” (p.61).

This is taken from the opinion of the appellate

court:

“ It had been two years since the first de

cision of the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board

of Education and, despite repeated demands

upon them, the boards of education had taken

no steps towards removing the requirement of

segregation in the schools which the Supreme

Court had held violative of the constitutional

rights of the plaintiffs. This was not ‘delib

erate speed’ in complying with the law as laid

down by the Supreme Court but was clear

manisfestation of an attitude of intransigence,

which justified the issuance of the injunctions

to dispel the misapprehension of school author

ities as to their obligations under the law and

to bring about their prompt compliance with

constitutional requirements as interpreted by

the Supreme Court” (p.64) (emphasis sup

plied).

In Orleans Parish School Board v. Bush 242 F.

2d 156 (C.C.A. 5th), the situation was the same.

The School District had made no start and it was

ordered to do so. From the opinion:

“ It is evident from the tone and content of

the trial court’s order and the willing acqui

escence in the delay by the aggrieved pupils that

a good faith acceptance by the school board of

24

the underlying principle of equality of educa

tion for all children with no classification by

race might well warrant the allowance by the

trial court of time for such reasonable steps in

the process of desegregation as appears to be

helpful in avoiding unseemly confusion and tur

moil. Nevertheless whether there is such ac

ceptance by the Board or not, the duty of the

court is plain. The vindication of rights guar

anteed by the Constitution can not be condi

tioned upon the absence of practical difficul

ties” (p.166).

That language was used in 1957, two years after

the second Brown decision, with respect to a district

that had not even formulated a plan of integration.

The last sentence in the quotation is the thesis of re

spondents. As an abstract declaration of law, it can

not be challenged. As a working rule to be applied

in all situations in the absence of power on the part of

the Federal Government to vindicate federal rights

and in the presence of forces which, if injected, will

destroy public education for both white and Negro

pupils, it can only be classed as obiter.

As stated in Brown—

“ Courts of equity may properly take into

account the public interest in the elimination of

such obstacles in a systematic and effective

manner.”

If the public interest is important and if it is

demonstrated that a too rapid enforcement of private

rights is harmful to the public interest, the ultimate

decision must come out of a balancing of the equities

between the two. In such situations there is little

helpfulness in a legal abstraction.

25

In Allen V. County School Board of Prince Ed

ward County, Va., 249 F. 2d 462, (C.C.A. 4th), the

school district was still stalling as late as November,

1957. The District Judge had declined to order it to

proceed and gave the following reasons :

(a ) Opposition to the order;

(b) racial tension in the community; and

(c) the possible closing of schools under a Vir

ginia statute.

Apparently no testimony was offered. Like the school

officials in Jackson, the District Judge did not think

the community was ready. Evidently the only racial

tension in existence was of the pro and con type which

develops in all southern localities when integration is

discussed.

In short, the Virginia situation was identical to

that of Jackson. There had been no start and the only

reason for the delay was that the populace did not

like the idea. The Court said:

“ * * * Furthermore, it would not be neces

sary for the requirement as to segregation to be

removed at once with respect to all grades in

the schools, if a reasonable start were made to

that end with ‘deliberate speed’ considering the

problems of proper administration. See order

in the Arlington case, approved by this court,

240 F. 2d at page 61, also Aaron v. Cooper (8

Cir.) 243 F. 2d 361.

“ The fact that the schools might be closed

if the order were enforced is no reason for not

enforcing it. A person may not be denied en

forcement of rights to which he is entitled un

der the Constitution of the United States be

cause of action taken or threatened in defiance

of such rights” (p.465).

26

In the foregoing cases only a “ mental attitude”

was involved. There were no overt acts of interfer

ence which crippled operations. The law draws a dis

tinction in many fields between a mental attitude and

an act. The first may be licit while the second may

be illicit. Here the District is not confronted with what

people of the community think about integration. It

is confronted with such realities as: Destroy

ing school property; planting disobedience in the

minds of the pupils; making the lives of the school

officials and teachers miserable; plunging the District

into expenses it cannot afford; spreading panic by

bomb threats; depriving pupils, Negro and white, of

an opportunity to obtain a normal education, etc., etc.

In the cases discussed above, the courts could

never have envisioned the turmoil, chaos and confusion

which agitators have thrust into the schools operated

by the District, and no court intends its opinion to be

stretched in meaning so as to furnish a guide for

factual situations unknown and unknowable at the

time it was rendered.

If there were nothing in this record other than

proof of a mental attitude, the position of the District

would be untenable under the decisions above men

tioned. If, on the other hand, there are illegal and

overt acts of interference which cannot be halted by

the District or some law enforcing agency, then the

schedule first adopted should be modified.

Respondents say a constitutional right cannot be

denied even to “ promote the public peace by prevent

ing race conflicts.” From that it does not necessarily

follow that a constitutional right, the enjoyment of

which is conditioned by the decision creating it, can

not reasonably be postponed in order to protect the

public interest, It is stated in Brown that in the

elimination of obstacles in the transition from segre

gated to integrated schools the courts shall “ take into

account the public interest.” The public interest re

ferred to is that mass of rights belonging to whites and

Negroes which are rooted in public education.

Of course, no constitutional right should be im

paired on the basis of what some partisan says may

happen in the future. That, however, is not the situa

tion before this Court. Here we are dealing with a

constitutional right and the existence of conditions

which enter into a decision as to whether it is en

forceable in the manner and according to the original

time schedule.

ill

RESPONSIBILITY FOR ENFORCEMENT

The argument that the District should be denied

relief because it did not affirmatively enforce the

public peace and quell insurrection is probably as

unrealistic as that involving the drayman and the

bridge.

This is no mere instance of a handful of dis

gruntled extremists in the community. The matter is

rather one of massive resistance to and defiance of

a constitutional principle running counter to the

mores of the people. Under the leadership of popular

office holders the people of the state are launched on

a steady course o f absolute nonrecognition of the

validity of the Broivn decisions, usually on the premise

that they are unconstititional. The people have been

told repeatedly by high officials, nationally syndicated

columnists and others that the Brown decisions are

not “ the law of the land” .

28

The District’s attempted desegregation met with

total opposition by the state government. As Mr.

Blossom stated (R .2 73 ):

“ My opinion as to that, sir, would be that

we have had total opposition from the State

in that the executive branch of state government

placed the troops around the school; the legis

lative branch of the government passed the

segregation acts, the judicial branch of the

government has not aided in any enforcement.

Now that may be a lay interpretation, but in

our system of government that embraces all

three branches of it, and instead of aid we have

opposition.”

And the Court may take judicial notice that two

weeks ago the Arkansas legislature voted almost

unanimously for the drastic anti-integration legisla

tion proposed by the governor and the attorney gen

eral.

At no time have the people of Little Rock

or the school board expressed a feeling that

integration of schools is desirable. The converse

is true. But initially most people felt a re

sponsibility as citizens to comply with orders of fed

eral courts if that day came. When the District

announced its plan of limited integration over a period

of time most appeared satisfied that this was the best

solution to a difficult problem.

Because of the statements made by our state’s

leadership, because of the failure of the Department of

Justice to prosecute members of mobs and others

hampering the federal courts, because several school

districts retracted desegregation plans with impunity,

because school districts refusing to formulate deseg

regation plans are still unintegrated despite months

29

and years of litigation, the people of Little Rock have

changed their opinion. Now, in view of the above,

the people believe that the District’s plan was

wholly unnecessary in light of the other means of

resistence, legal and otherwise.

The District has exercised good faith with the

courts and will continue to do so but its task is not

one of preserving the peace. It did not pursue a plan

of desegregation through choice, and it should not

now be placed in the position of being duty bound to

quell defiance. It is not the function of a school

district to act as a buffer in a contest between state

and federal authority, and certainly not to act as the

bulwark of federal authority in such a contest.

This Court, in giving a new interpretation to the

Fourteenth Amendment, has pronounced a rule of law

which is well in advance of the mores of the people

of this region and violent opposition to its principle has

erupted.

The purpose behind the filing of the Petition is to

ascertain whether a non-combatant school district

must submit to interference such as is revealed here

in the absence of any effective protection from the

Federal Government. If no protection is to be ex

pected in two and one-half years, it will be wise to

suspend operations for that period. If, in the nature

of things, there will never be any protection, operations

should be suspended until such time as the people, by

the processes of time, are taught to respect Federal

Court decisions and to be willing, on patriotic grounds,

to subdue the passions which now control their think

ing.

Instead of facing the problem, the Respondents

would gulp the rights which are said to be theirs

30

with no concern whatever as to whether their course

will end in frustration and a further wasting away

of respect for national law. The District Court could

see far beyond the horizon of the negro students. There

are visible rights other than those of immediacy in

integration. The public interest is involved, and it

was thought best to adjust and balance rather than

apply the over simplified syllogism that this Court

having said the Negro pupils are entitled to some

rights, it therefore follows that any retardation in

granting those rights, regardless of the reason, is un

reasonable.

There is no questioning of constitutional rights

in a short delay. Those rights are recognized. In a

temporary postponement of the time for the exercise

of those rights, based on sound reason, there is no

intimation of a lowering of status. A reasonable

postponement is in the nature of an adjustment wisely

required for the better protection of the very rights

which are asserted. That is the rationale of the

District Court’s decision. As a rule, education is far

removed from the controversial areas of government.

No one would think of a school district as being

equipped to enforce a law which is objectionable to

those who supply the funds with which the District

is operated, and yet that seems to be one of the basic

ideas of appellant. The petitioners quite candidly

told the District Court they did not look upon such

enforcement as being a duty and they felt it would

be improper for the District, which is tax supported

and whose revenues are limited, to expend its funds

in perpetual litigation and prosecutions. Surely there

is no federal law which could possibly impose upon

a local school district any kind of a mandate which

would force it to use its revenues, not for educational

31

purposes, but for compeling obedience on the part of

others to federal laws.

Mobs formed preventing entry of the Negro

pupils and screaming insults upon the Police Depart

ment, school officials and the Federal Court. Arrests

were made by the police, but the offenders were dis

charged by the judge who presided over the Municipal

Court. There was not a single prosecution by the

Federal Government. There was not a single citation

for contempt, although many of the participants were

identifiable. A spokesman for the Department of

Justice, in an effort to impress upon the Governor of

Arkansas the importance of maintaining law and or

der through State action, explained the difficulties of

Federal enforcement. Thereupon the Governor re

vealed through the press the existing weakness in

Federal enforcement and this, as intended, gave im

petus to the deliberate flouting of the federal law.

The FBI made an investigation and it is to be assumed

that it identified the ring leaders. The local papers

contained pictures of Negro pupils going into the

office of the United States District Attorney to make

complaints. Nothing happened. Then came a front

page announcement in jumbo type that the Attorney

General of the United States would not prosecute any

of those who had taken part in the unlawful demon

strations.

We are not in the least critical of the Department

of Justice. As a matter of fact, we believe its staff

has shown a high degree of competence and zeal in

the Hoxie case and in the action to restrain the use of

Arkansas National Guard in preventing Negro pupils

from entering Central High School. The brutal fact

is that the Department of Justice has only few and

inadequate legal implements it can use in punishing

32

those who directly or indirectly defy the Federal Court

order of integration. This fact having become ob

vious, the agitators are emboldened and they go to

further extremities in placing their individual ideas

of law above any disagreeable judicial decision.

The problem of enforcement is forcefully pointed

out in the book, “ Desegregation and the Law” , by Al

bert P. Blaustein and Clarence Clyde Ferguson, Jr.

(1957) , members of the faculty of Rutgers University

Law School. It is there pointed out that severe doubts

exist as to the constitutionality of Sections 241 and

242 of Title 18, United States Code. United States v.

Williams, 341 U.S. 70; Screivs v. United States, 325

U.S. 91. And it is further pointed out that the con

tempt power is limited by the requirement of certainty

when dealing with broad desegregation orders and

by its inherent inadequacy in coping with community

disrespect for federal law.

In an article entitled “ Negro Citizens in the Su

preme Court of the United States” , 52 Harvard Law

Review (1939), at page 832, this is found:

“ It is impossible in reviewing these de

cisions to avoid the conclusion that the Su

preme Court, until recently at least, has been

no great friend to the black man. There are

those who believe that it could have done no

more with a nonrational problem packed with

sectional dynamite. Legislation running coun

ter to emotions rising to a religious pitch is

likely to require bayonets rather than equity

decrees to enforce it. The Court is not well

equipped to deal with a conspiracy by a whole

state; and, when Congress has for so long been

reluctant to interfere, it is not surprising that

the Court should refrain from interfering with

state policy.”

33

The author cites Giles v. Harris, 189 U.S. 475.

In the opinion Mr. Justice Holmes had this to say:

“ The other difficulty is of a different sort,

and strikingly reinforces the argument that

equity cannot undertake now, any more than

it has in the past, to enforce political rights,

and also the suggestion the state constitutions

were not left unmentioned in Sec. 1979 by ac

cident. In determining whether a court of

equity can take jurisdiction, one of the first

questions is what it can do to enforce any order

that it may make. This is alleged to be the

conspiracy of a State, although the State is not

and could not be made a party to the bill. Hans

v. Louisiana, 134 U.S. 1. The Circuit Court

has no constitutional power to control its action

by any direct means. And if we leave the

State out of consideration, the court has as

little practical power to deal with the people

of the State in a body. The bill imports that

the great mass of the white population intends

to keep the black from voting. To meet such

an intent something more than ordering the

plaintiff’s name to be inscribed upon the lists

of 1902 will be needed. If the conspiracy and

the intent exist, a name on a piece of paper will

not defeat them. Unless we are prepared to

supervise the voting in that State by officers

of the court, it seems to us that all that the

plaintiff could get from equity would be an

empty form. Apart from damages to the in

dividual, relief from a great political wrong,

if done, as alleged, by the people of a State

and the State itself, must be given by them or

by the legislative and political department of

the government of the United States (emphasis

supplied).

Counsel for appellants asked witnesses for the

District why they did not institute proceedings against

those who interfered with the operations of Central

High School as was done in Kasper v. Brittain 38,

245 F. 2d 92 (C.C.A. 6th), and Brewer v. Hoxie School

District, 238 F. 2d 91 (C.C.A. 8th). The reasons are

obvious. In the Kasper case, only Kasper himself was

involved. He fomented the strife. The school of

ficials asked for a restraining order. It was entered

and ignored. Kasper was then adjudged to be in

contempt and brought before the court with an order

of attachment. From that point on it was the pre

siding judge and not the school officials who placed

Kasper in the federal penitentiary.

In the Hoxie case (137 F. Supp. 364), there were

only four defendants, to-wit, Brewer, Guthridge,

Johnson and Copeland. The results of the agitation

they had created involved the personal safety of the

school officials and many others. The officials, aided

by the Attorney General of the United States, sought

an order of injunction. The latter had come in as

amicus curiae. He filed an exhaustive brief in the

Court of Appeals, and we are sure he was mainly

responsible for the results of the litigation.

It seems inconsistent to us that counsel employed

by NAACP contend that a school district sustained

by tax funds should assume the burden of prosecuting

those who interfere with the District’s efforts to com

ply with the terms of the Plan. NAACP is an organ

ization created for the very purpose of establishing and

then enforcing constitutional rights of Negro pupils.

It has a most capable legal staff and adequate funds.

The idea of transferring to the School Board the bur

den of prosecuting violators of the Court order is as

strange as the idea of requiring a defendant who has

been cast in damages to issue the process that will

consume his assets in order that the plaintiff’s judg

ment may be satisfied.

35

It is true that in Thomason v. Cooper, 254 F. 2d

808 (E.D. A rk), the District applied to the District

Court for an injunction against the use of a State

court order which would have compelled it to violate

the District Court’s order. That, however, was no

indication of a willingness to assume the role of public

prosecutor. As stated by Judge Sanborn, the District

was between the “ upper and the nether millstone” .

The District officials respect their oaths to sup

port the Constitution of the United States and they

have done so to the best of their ability. Now they

have concluded that a sincere effort on their part is not

enough. They have practiced no strategy of evasion.

They have made no move without asking approval

of the Federal Court. Their attitude from the start

has been one in which law and order along with their

primary function of maintaining a public school sys

tem have priority.

In Faubus v. United States, 254 F. 2d 797

(C.C.A. 8th), the Federal Government had the power

to act, and it exercised such power with swiftness in

putting a stop to an unlawful defiance of a Federal

Court order. A school district, however, which func

tions only in the field of education, is not as formidable

an adversary as the United States of America.

Respondents quote from the Faubus case as fol

lows:

“ * * * A rule which would permit an

official whose duty it was to enforce the law, to

disregard the very law which it was his duty

to enforce, in order to pacify a mob or suppress

an insurrection, would deprive all citizens of

any security in the enjoyment of their lives,

liberty, or property (p.33).

36

To enforce the law of the land is obviously a duty

of a law enforcing agency, but one of the vital ques

tions here is whether any such duty rests on a school

district. If it be said that the duty rests on the

school district, then we ask how can it possibly en

force the federal law and where is it to obtain funds

to be used for the purpose?

IV

THE DISTRICT IS ENTITLED TO RELIEF

The District has requested and received from the

District Court a stay of desegregation for two and

one-half years. Its request was granted for com

pelling reasons of public interest and preservation of

the educational system. The Circuit Court of Appeals

reversed although admitting the predicament of the

District.

The District Court found that the situation was

intolerable but this term cannot begin to describe the

loss to the community and the nation that results from

impairment and even breakdown in the educational

process. This Court should not revisit chaos and

bedlam upon the District, but rather should uphold Dis

trict Judge Lemley in his determination of the local

situation.

Where a school board has made a prompt start

toward desegregation and has continued throughout

to exercise good faith, severe impairment of the edu

cational system both present and prospective because

of desegregation entitles the school district to a post

ponement regardless of the source and motivation of

the destructive forces. The second Brown decision

was so construed by the District Court.

37

If the Brown rule is not sufficiently flexible to

allow time for the subsidence of forces such as are

arrayed here against it, then it may be seriously

doubted whether courts are able to effectively cope

with “ state action” such as this, and perhaps this

Court should so hold. Certainly the legislative and polit

ical departments of the United States government have

displayed little willingness to assist in the implementa

tion of the Brown decisions, although the matter would

seem to rest more appropriately in those departments

where obstruction by the governor and legislature and

mass opposition by the people of a state is concerned.

We are not saying that all of the havoc created

by the militant conflicting forces arrayed against

each other as a result of the Brown decisions can be

dispelled within the next two and one-half years, but

we are saying that a reasonable period of calm is

the only hope of producing solutions to the distressing

problems which this School Board and the people of

this community must solve. This School Board pleads

for that opportunity. The ruling of the District

Court can and should be upheld within the frame

work of the pronouncements of this Court in the

Brown decisions.

38

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated it is respectfully submitted

that the judgment of the Circuit Court of Appeals

should be reversed.

R ic h a r d C. B u t l e r

Boyle Building

Little Rock, Arkansas

A . F . H o u se and

J o h n H . H a l e y

314 West Markham Street

Little Rock, Arkansas

Attorneys for Petitioners

APPENDIX

FOLKWAYS by WILLIAM GRAHAM SUMNER

In our southern states, before the civil war,

whites and blacks had formed habits of action and

feeling toward each other. They lived in peace and

concord, and each one grew up in the ways which were

traditional and customary. The civil war abolished

legal rights and left the two races to learn how to

live together under other relations than before. The

white have never been converted from the old mores.

Those who still survive look back with regret and

affection to the old social usages and customary senti

ments and feelings. The two races have not yet made

new mores. Vain attempts have been made to con

trol the new order by legislation. The only result is

the proof that legislation cannot make mores. We

see also that mores do not form under social con

vulsion and discord. It is only just now that the new

society seems to be taking shape. There is a trend

in the mores now as they begin to form under the new

state of things. It is not at all what the humani

tarians hoped and expected. The two races are separ

ating more than ever before. The strongest point in

the new code seems to be that any white man is boy

cotted and despised if he “ associates with negroes” .

Some are anxious to interfere and try to control.

They take their stand on ethical views of what is

going on. It is evidently impossible for any one to

interfere. We are like spectators at a great natural

convulsion. The results will be such as the facts and

forces call for. We cannot foresee them. They do

not depend on ethical views any more than the volcanic

eruption on Martinique contained an ethical element.

All the faiths, hopes, energies, and sacrifices of both

40

whites and black are components in the new construc

tion of folkways by which the two races will learn how

to live together. As we go along with the construc

tive process it is very plain that what once was, or

what any one thinks ought to be, but slightly affects

what, at the moment, is. The mores which once were

are a memory. Those which any one thinks ought to

be are a dream. The only thing with which we can

deal are those which are.

The abolition of slavery in the northern states

had been brought about by changes in conditions and

interests. Emancipation in the South was produced

by outside force against the mores of the whites there.

The consequence has been forty years of economic,

social, and political discord. In this case free in

stitutions and mores in which free individual initiative

is a leading element allow efforts towards social read

justment out of which a solution of the difficulties will

come. New mores will be developed which will cover

the situation with customs, habits, mutual concessions,

and cooperation of interests, and these will produce a

social philosophy consistent with the facts. The pro

cess is long, painful, and discouraging, but it contains

its own guarantees.

We often meet with references to Abraham Lin

coln and Alexander II as political heroes who set free

millions of slaves or serfs “ by a stroke of the pen” .

Such references are only flights of rhetoric. They en

tirely miss the apprehension of what it is to set men

free, or to tear out of a society mores of long growth

and wide reach. Circumstances may be such that a

change which is imperative can be accomplished in no

other way, but then the period of disorder and con

fusion is unavoidable. The stoke of the pen never does

anything but order that this period shall begin.

41

All these cases go to show that changes which run

with the mores are easily brought about, but that

changes which are opposed to the mores require long

and patient effort, if they are possible at all.

I f we admit that it is possible and right for some

to undertake to mold the mores of others, of set pur

pose, we see that the limits within which any such

effort can succeed are very narrow, and the methods

by which it can operate are strictly defined. The

favorite methods of our time are legislation and

preaching. These methods fail because they do not

affect ritual, and because they always aim at great

results in a short time. Above all, we can judge of

the amount of serious attention which is due to plans

for “ reorganizing society” , to get rid of alleged errors

and inconveniences in it. We might as well plan

to reorganize our globe by redistributing the elements

in it.

Strictly speaking, there is no administration of

the mores, or it is left to voluntary organs acting

by moral suasion. The state administration fails

if it tries to deal with the mores, because it goes

out of its province.

Great crises come when great new forces are at

work changing fundamental conditions, while power

ful institutions and traditions still hold old systems

intact. The fifteenth century was such a period. It

is in such crises that great men find their opportun

ity. The man and the age react on each other. The

measures of policy which are adopted and upon which

energy is expended become components in the evolu

tion. The evolution, although it has the character

of a nature process, always must issue by and through

men whose passions, follies, and wills are a part of

42

it but are also always dominated by it. The interaction

defies our analysis, but it does not discourage our

reason and conscience from their play on the situation,

if we are content to know that their function must

be humble.

JOURNAL OF PUBLIC LAW

EMORY UNIVERSITY LAW SCHOOL

Volume 8 Spring 1954

Number 1

A u t h o r R u p e r t V a n c e

What of those important officers of administra

tion, the members of local school boards? What al

ternative have they? Obviously their alternatives are

limited: they cannot resign when they are sued, en

joined, or jailed for the community’s noncompliance

with the law. But as citizens they can refuse service

on school boards. Since there is political capital to be

gained in these areas, such refusal to serve may well

be selective— exercising negative selection on the more

moderate business men and administrators, and bring

ing forward those types who realize the political re

wards to be reaped through the revival o f the “ Negro

baiting” tactics of the recent past.

A u t h o r W y l i e H . D a v is

Georgia is the only state which has immediately

reacted to the school decisions with loud rumblings

of threatened violence. Governor Talmadge and his

cohorts, including some of his potential assignees

43

office, have pledged employment of the state militia