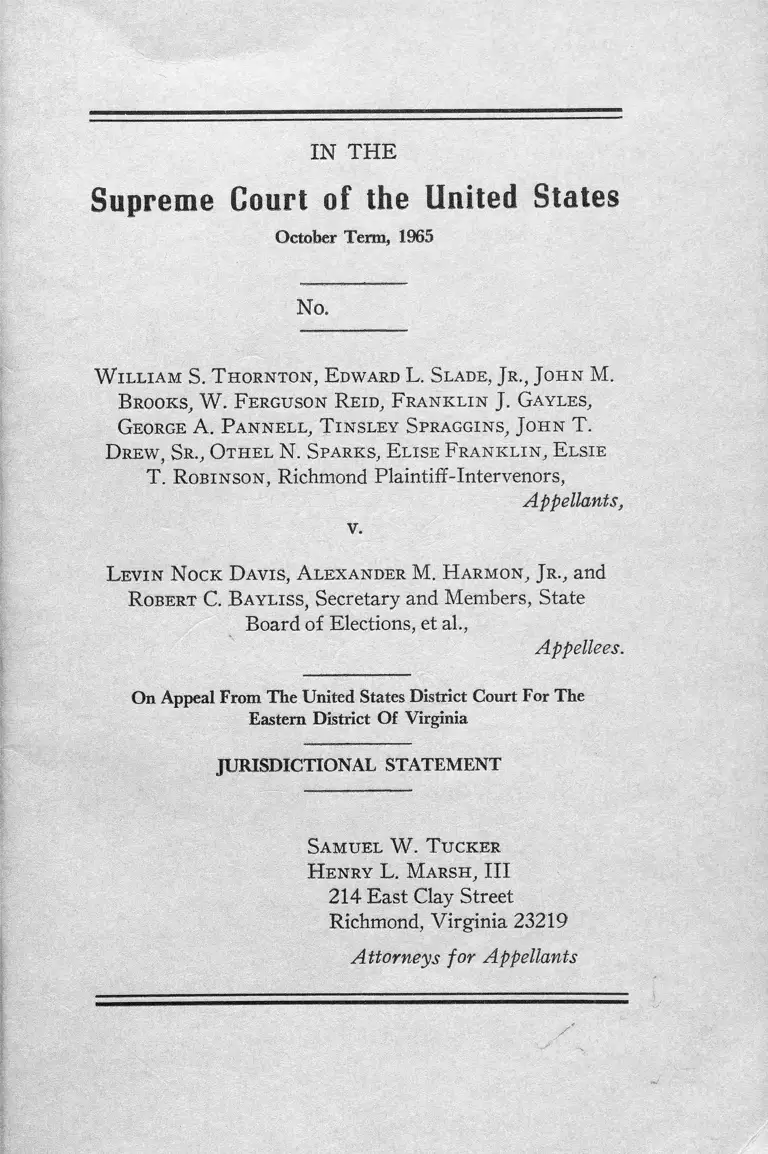

Thornton v. Davis Jurisdictional Statement

Public Court Documents

September 18, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Thornton v. Davis Jurisdictional Statement, 1964. 6dfe1323-c69a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1efe23df-a021-4438-abac-81035f3cbe71/thornton-v-davis-jurisdictional-statement. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1965

No.

W il l ia m S. T h ornton , E dward L. S lade, Jr ., Jo h n M.

B rooks, W . F erguson R eid, F r a n k l in J. Gayles,

George A. P a n n ell , T in sley Spraggins, Jo h n T.

D rew , Sr., O th e l N. S parks, E lise F r a n k l in , E lsie

T. R obinson , Richmond Plaintiff-Intervenors,

Appellants,

v.

L evin N ock D avis , A lexander M. H arm on , Jr ., and

R obert C. B ayliss , Secretary and Members, State

Board o f Elections, et al.,

Appellees.

On Appeal From The United States District Court For The

Eastern District Of Virginia

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

Sam u el W . T ucker

H enry L. M arsh , III

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

Attorneys for Appellants

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Jurisdictional Statem en t ........................................................................ 2

O pin io n Below .............................................................................................. 3

Jurisdiction ........................................................................ 3

T he Statutes I nvolved ............................................................................... 3

T he Q uestions P resented ........................................... 3

Statem en t of th e Case ............................................................................ 4

The Facts ................ - ......................................................................... *5

The Circumstances Surrounding the Adoption of the 1964

Reapportionment Statutes .............. 8

Equally Weighted Votes Was Not the Legislative Concern .... 14

T he Q uestions A re Su b s t a n t ia l ..................................................... 17

Conclusion ......... —................................................................................. —- 23

A ppendix A

Order on Petitions and Complaints of Intervenors from Hen

rico County, City of Richmond and Shenandoah County .... 1

Opinion ................................................................................................ 4

A ppendix B

Order on Mandate......................................................... -.................. 1

Opinion upon Order on M andate................................. ................ 5

A ppendix C

Chapter 1— Acts of the General Assembly of Virginia, Extra

Session 1964............................................ ................ ,.......-.......... 1

Chapter 2— Acts of the General Assembly of Virginia, Extra

Session 1964..................................................................................

A ppendix D

Public Documents Reflecting Virginia’s Official Reaction to

Brown v. Board of Education and Related Fourteenth

Amendment Rights .....................................................................

TABLE OF CITATIONS

Cases

Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond (4th Cir. 1963),

317 F. 2d 4 2 9 ......................................................................................

Davis v. Mann (1964), 377 U. S. 678, 12 L. ed. 2d 609, 84 S. Ct.

1441 ........ ...................................................................... 3, 4, 9, 10,

Fortson v. Dorsey (1965), 379 U. S. 433, 13 L. ed. 2d 401, 85 S.

Ct. 498 ..................................................................... 3, 17, 18, 19,

Gomillion v. Lightfoot (1960), 364 U. S. 339, 5 L. ed. 2d 110, 81

S. Ct. 1 2 5 ............................................................................................

Mann v. Davis (1962), 213 F. Supp. 571 .........................................

N AA C P v. Button (1963), 371 U. S. 415, 9 L. ed. 2d 405, 83 S.

Ct. 328 ................................................................................................

Reynolds v. Sims (1964), 377 U. S. 533, 12 L. ed. 2d 506, 84 S.

Ct. 1326 ................................................................................. 3, 18,

Wade v. City of Richmond (1868), 18 Gratt. (59 Va.) 583 .... 19,

Wright v. Rockefeller (1964), 376 U. S. 52, 11 L. ed. 2d 512, 84

S. Ct. 603, reh den 376 U. S. 959, 11 L. ed. 2d 977, 84 S. Ct.

964 ........................................................................................................

5

1

6

13

23

22

4

17

21

20

22

28 U. S. C.

Statutes

Page

§2101 (b ) ...................................................................... - ................ 3

§2281 .................................................................................................. 3

§2284 ................................................................................. -~......... - - 3

42 U. S. C.

§ 1983 ............................................................................... — .............. 3

§ 1988 .................................................................................- - - - - - ...... 3

Va. Const., 1902

§ 41 ....................................................................................................... 20

§ 42 ................................-..................................................................... 20

§ 43 .......................................................................... -................... ....... 20

§ 44 ..................................................................................... .............. 20, 21

Va. Code, 1950

§ 24-12 .............................................................................................. 3, S

§ 24-14 .............................................................................................. 3. 5

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1965

No.

W il liam S. T h ornton , E dward L. Slade, Jr ., Jo h n M. B rooks,

W . F erguson R eid, F r a n k l in J. Gayles, George A. P an n e ll ,

T insley Spraggins, Jo h n T. D rew , Sr ., O th el N. S parks, E lise

F r a n k l in , E lsie T. R obinson , Richmond Plaintiff-lntervenors,

Appellants,

v.

L evin N ock D avis, A lexander M. H arm on , Jr., and R obert C.

Bay liss , Secretary and Members, State Board of Elections;

T hom as R . M iller, Clerk, Hustings Court of the City of Richmond;

W ilm er L. O ’F lah erty , Sue D. B roun and R obert C. C h appell ,

Members, Electoral Board of the City of Richmond;

H elen D. Clevenger, Clerk, Circuit Court of Henrico County;

L inwood E. T oombs, E. R. B oisseau and C. K emper L orraine,

Secretary and Members, Electoral Board of Henrico County;

H arrison M a n n , K a th r y n Stone, Jo h n C. W ebb and Jo h n A. K.

D o navan , Original Plaintiffs;

H. B ruce Green , Clerk, Circuit Court of Arlington County;

D e n m a n T. R ucker, M aynard Carlisle and R alph K im ble ,

Members,, Electoral Board, Arlington County;

T hom as P. C h a p m a n , Jr ., Clerk, Circuit Court of Fairfax County;

P au l K incheloe, E bner L. D u n ca n , Jones Jasper, Members

Electoral Board, Fairfax County;

C harles L. Glanville , W illiam L. S hepheard , P aul, M. L ip k in

and Jack R. W il k in s , Norfolk Plaintiff-lntervenors;

2

W il liam L. P rieur, Jr., Clerk, Corporation Court of the City of

Norfolk; James M. W ilcott, Joseph T. F itzpatrick and James

E. B aylor, Members, Electoral Board, City of Norfolk;

Jesse D. F un kh ou ser , H enry L. H oller, W . H olmes F owle,

W il liam P. L ineburg , J. E ldred S w artz and Cletus R.

L indamood , Shenandoah Plaintiff-Intervenors;

M arvin G. S igler, Clerk, Circuit Court of Shenandoah County;

W arren B. F ren ch , Sr., P au l S hutters and F red H e ish m a n

Members, Electoral Board, Shenandoah County,

Appellees.

S im eon A. B urnette , B. E arl D u n n , E d w in H. R agsdale and

L. R ay S h adw ell , Jr .,

Co-Appellants.

On Appeal From The United States District Court For The

Eastern District O f Virginia

JURISDICTIONAL STATEM ENT

Appellants, William S. Thornton, et al., designated as

the Richmond Plaintiff-Intervenors, appeal from the judg

ment of the three-judge United States District Court for

the Eastern District o f Virginia, entered April 9, 1965,

dismissing the intervening petition and complaint filed by

appellants in the civil action therein pending under the

style, Harrison Mann, et al., v. Levin Nock Davis, et al., to

challenge the constitutionality o f the Virginia Reapportion

ment Acts o f 1964 and submit this statement to show that

the Supreme Court o f the United States has jurisdiction of

the appeal and that a substantial question is presented.

OPINION BELOW

The opinion o f the three-judge District Court for the

Eastern District of Virginia is not yet reported. The opinion

and the order thereon are printed as Appendix A hereof.

3

JURISDICTION

This proceeding stems from the intervention by certain

citizens of the City o f Richmond in a suit styled Davis v.

Mann instituted on April 9, 1962, to test the validity of the

statutory apportionment of seats in both houses of the

General Assembly of Virginia. The original action and the

intervening petition and complaint of appellants were

brought under 28 U.S.C. § 1343 (3 ) to assert rights pur

suant to 42 U.S.C. §§ 1983, 1988 and to obtain injunctions

under 28 U.S.C. §§ 2281, 2284.

The judgment now sought to be reviewed is dated and was

entered on April 9, 1965. No rehearing was requested.

Notice of appeal was filed by the instant appellants on June

7, 1965, in the United States District Court for the Eastern

District o f Virginia.

The jurisdiction of the Supreme Court to review this

decision by direct appeal is conferred by 28 U.S.C.§§ 1253,

2101 (b ).

The following decisions sustain the jurisdiction of the

Supreme Court to review the judgment on direct appeal:

Fortson v. Dorsey (1965), 379 U.S. 433, 13 L. ed 2d 401,

85 S.Ct. 498; Davis v. Mann (1964), 377 U.S. 678, 12 L.

ed 2d 609, 84 S.Ct. 1441; Reynolds v. Sims (1964), 377

U.S. 533, 12 L. ed 2d 506, 84 S.Ct. 1362.

THE STATUTES INVOLVED

The state statutes, the validity of which is involved in

this appeal, are Sections 24-12 and 24-14 of the Code of

Virginia 1950, as amended by the 1964 Extra Session of

the General Assembly of Virginia. They are set out in

Appendix C hereof.

THE QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Do the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments pro

hibit a state from combining two multi-member legislative

4

districts into one multi-member legislative district in which

the voting strength of a minority racial element o f one of

the former districts will be minimized or canceled out; par

ticularly when no other suggested purpose for such change

is plausible ?

2. Do the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments pro

hibit a state from requiring that all of a city’s legislative

representatives be elected by the voters of the city at large,

when the purpose or effect o f such a requirement is to mini

mize or cancel out the voting strength of a racial minority ?

STATEM ENT OF CASE

This litigation was commenced on April 9, 1962, in the

United States District Court for the Eastern District of

Virginia by certain residents, taxpayers and qualified voters

of Arlington and Fairfax Counties, charging that they were

subjected to invidious discrimination in the apportionment

of seats in the General Assembly o f Virginia as provided by

the 1962 statutes. Residents of the City of Norfolk inter

vened to show that the statutes effected invidious discrimin

ation against that area as well. On November 28, 1962, the

three-judge District Court sustained the plaintiffs’ claims.

Mann v. Davis, 213 F. Supp. 577. On appeal by the state

officials, the judgment of the District Court was affirmed.

Davis v. Mann, 377 U.S. 678 (1964).

By its September 18, 1964 order, on the mandate, the

District Court further stayed the enforcement of its Novem

ber 28, 1962 order to permit the General Assembly to enact

constitutionally valid reapportionment statutes for both

houses and provided that if such reapportionment legislation

as might be enacted failed to meet the requirements of the

Constitution, then the plaintiffs, the plaintiff-intervenors

and any party granted leave to intervene may apply to the

court for such further orders as may be required.

5

The General Assembly of Virginia, by acts approved

December 2, 1964, amended §§ 24-12 and 24-14 o f the

Code of Virginia. The effect o f the amendment o f § 24-12,

as far as is material to this appeal, was to allot eight dele

gates to the 36th House o f Delegates District consisting of

the City of Richmond and the County o f Henrico which,

prior to 1962, had been entirely separate districts.

The effect o f the amendment of § 24-14, as far as is

material to this appeal, was to allot two senators to the 30th

Senatorial District consisting of the entire City of Rich

mond.

Certain residents, taxpayers and voters o f the County

of Henrico (Simeon A. Burnett and others), designated as

Henrico Plaintiff-Intervenors, filed their intervening peti

tion asserting that, insofar as the amendment to § 24-12

combines the County of Henrico with the more populous

City of Richmond for representation in the House of Dele

gates, the statute effects an invidious discrimination against

voters of Henrico County who are entitled to be represented

by three delegates elected by the voters of the county at

large.

Certain residents, taxpaj^ers and voters o f the City of

Richmond all of whom are Negroes ( William S. Thornton

and others, sometimes referred to as Richmond Plaintiff-

Intervenors), filed their petition asserting that both sta

tutes as amended violate their rights under the Fourteenth

and Fifteenth Amendments inasmuch as the at-large elec

tion arrangements serve to dilute the effectiveness of those

Negro voters who, by reason of the segregated residential

pattern, inhabit certain sections o f Richmond in such num

bers that they would be in predominantly Negro districts

if Richmond were divided into single-member districts.

Further, the Richmond Plaintiff-Intervenors contend that

the purpose and effect of the combination of Richmond

6

and Henrico was and is to diminish and cancel out the rela

tive strength of the Negro vote in Richmond. The District

Court rejected the contentions o f both sets of intervenors.

THE FACTS

In 1934, approximately one-fourth of the Negroes in

the City of Richmond resided in “ East-End” and approxi

mately one-half o f Richmond’s Negroes resided in the

downtown or “ Central” area o f the city. The Master Plan

for the Physical Development of the City o f Richmond as

adopted by that city’s governing body in or subsequent to

1945 suggested that low rental housing be located in vacant

areas in sections of the city removed from the then existing

downtown slums; and that those slums could be replaced

by “ downtown apartments for white collar workers and

other income groups or for some industrial or public pur

pose” (R. pp. 74-75). Accordingly, the Council caused four

o f the five public housing projects now occupied by Negroes

to be located in Richmond’s “ East End” (R . p. 75).

The continued efforts o f the city’s school board to retain

racial segregation in the public schools accommodated and

contributed to the racially segregated residential pattern.

It is stipulated that until March of 1963, when it adopted

a “ Freedom of Choice” policy with respect to racial segre

gation in public education, the school board attempted to

meet the problem of overcrowding in Negro schools by

building new schools in Negro neighborhoods, making addi

tions to existing Negro schools and converting white schools

to Negro schools (R. p. 73). An illustrative occurrence is

related in Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond,

Virginia, 317 F. 2d 429 (4th Cir. 1963), viz: “ At a special

meeting held on September 15, 1958 (approximately two

weeks after the beginning of the school term), the School

Board voted to request the Pupil Placement Board to trans

7

fer the pupils then attending the Nathaniel Bacon School

(white) to the East End Junior High School (white), and

that a sufficient number o f pupils be transferred from the

George Mason (N egro) and Chimborazo (N egro) schools

to the Nathaniel Bacon building to utilize its capacity, thus

converting Nathaniel Bacon to a Negro School.”

Public authority accomplished its expressed purpose of

“ siphoning” Negroes from the older slum areas in the

central part of the city (R . p. 75) by developing a concen

tration of Negroes in Richmond’s East End. The 1960

Census shows that o f 92,331 non-white persons residing in

the City of Richmond, 41,899 or 45.4% lived in the East

End; 31,910 or 34.5% in Central; 10,062 or 10.9% in

Northside; 7,850 or 8.5% in Southside and 610 or 0.7% in

West End (Richmond Exhibit 10).

Substantial equality of population in these five major divi

sions of the city might be achieved by extending “ West

End” eastwardly into “ Central” and by extending “ North-

side” southwardly into “ Central” (Richmond, Exhibits 10,

15). These adjustments would leave “ East End” with a pop

ulation larger than either of the other four units— a fact

which does not detract from the force of the arguments here

advanced. So distributed, Negroes (comprising 42% of

Richmond’s total population) would constitute 88.6% of

East End’s total population of 47,275; 54.9% of Central’s

total population of 44,503; 40.8% of Northside’s total popu

lation of 44,350; 20.4% of Southside’s total population of

38,453; and 0.01% of West End’s total population, of 45,-

377 (Richmond Exhibit 15). It is impossible to divide

Richmond into five House of Delegates Districts o f sub

stantially equal population without creating one or more

districts in which Negroes will predominate (Gayles, Dep.

58). Any logical division of Richmond into two senatorial

districts o f substantially equal population is likely to create

8

one in which Negroes will predominate (Gayles, Dep. 43-

54). Only 5% of Henrico’s population of 117,339 is non

white.

As will be next seen, the General Assembly was aware of

the concentration o f Negroes in the City o f Richmond when

it convened in Extra Session to effect a legislative redistrict

ing in accordance with the directives of the Court.

The Circumstances Surrounding

The Adoption of the 1964 Reapportionment Statutes

The Committee on Privileges and Elections o f the House

of Delegates had conferred prior to the convening- o f the

General Assembly on November 30, 1964. Its report to the

House of Delegates recommended 2 delegates for Henrico

County separately and 6 Delegates for Richmond City and

Henrico County together (Henrico Exhibit 7, R. 441,

443). The Committee had before it the report, dated No

vember 15, 1961, of the Commission on Redistricting ap

pointed by the Governor in January o f 1961, which recom

mended 3 delegates for Henrico County and 6 delegates for

Richmond City (Henrico Exhibit 6, R. 415, 427). That

Commission had requested the Bureau o f Public Adminis

tration, University of Virginia, to analyze the problems and

make recommendations. Its report to the Commission of

July 17, 1961, presented Plan A which provided 3 delegates

for Henrico and 6 delegates for Richmond City (Henrico

Exhibit 5, R. 403, 406).

The recommendation of the House Committee on Privi

leges and Elections was not unanimous. One of its members

who had been chairman of the Governor’s Commission on

Redistricting filed a written dissent in favor of the recom

mendations of his Commission (Henrico Exhibit 7, R.

458). In so doing he said:

9

“ In the extensive deliberations of the Committee, I

consistently observed and commented on the obvious

efforts o f a majority o f the Committee to shield and

protect numerous members of the House whose seats

were in jeopardy.”

The recommendation o f the House Committee on Privi

leges and Elections was embodied in House Bill No. 1

and presented to the House o f Delegates by its sponsors,

one o f whom was a Richmond City resident and member

of the joint delegation representing Richmond City and in

part Henrico County in the House o f Delegates under the

1962 apportionment statute declared unconstitutional by

this Court in Davis v. Mann, supra. House Bill No. 1

created a 36th District composed o f Henrico County alone,

having 2 delegates, and a 56th District composed o f Rich

mond City and Henrico County o f 6 delegates (Henrico

Exhibit 8, R. 461,462,463).

The General Assembly also had before it a resolution of

the Board of Supervisors of Henrico County, unanimously

adopted October 28, 1964 (Henrico Exhibit 9, R. 464;

Burnette Dep., R. 338) and a resolution o f the Council of

the City of Richmond, unanimously adopted November 30,

1964 (Henrico Exhibit 10, R. 466; Crowe Dep., R. 232),

both of which strongly urged separate representation for

the city and county. It was also advised that merger of

Richmond City and Henrico County had been defeated by

a Henrico County vote of 13,647 to 8,862 on December 12,

1961, while voters in Richmond City favored the merger

by 15,050 to 6,698 (Henrico Exhibit 20, R. 507).

The House Committee on Privileges and Elections held a

public hearing on House Bill No. 1 at which the Mayor

o f Richmond City, the Chairman of the Legislative Com

mittee of the Richmond City Council and the Chairman o f

10

the Board o f Supervisors of Henrico County each spoke

for separate and independent representation in the House of

Delegates and recognized necessary conflicts in the joint

representation of the two independent political subdivisions

(Crowe Dep., R. 232, 235; Wheat Dep., R. 331, 334;

Burnette Dep., R. 339-340).

Richmond City and Henrico County were represented in

the 1964 Extra Session of the General Assembly under the

1962 reapportionment statute declared unconstitutional by

this Court in Davis v. Mann, supra. Under that statute

Henrico County had one independent delegate and Rich

mond City and Henrico had eight delegates jointly (Henrico

Exhibit 36A, R. 638). O f those eight, five Democrats and

two Republicans lived in the City of Richmond, and one

Democrat resided in Henrico County (Pollard Dep., R. 228;

Sutton Dep., R. 116; Bradshaw Dep., R. 285; Herrink

Dep., R. 354-355; Andrews Dep., R. 94-97).

House Bill No. 1 was recommitted to the House Commit

tee on Privileges and Elections on November 30, 1964

(Henrico Exhibit 12, R. 470). On December 1, 1964, the

Committee reported the bill with amendments that elimi

nated altogether any independent delegate for Henrico and

consolidated Richmond City and Henrico County into a

single House district to be represented by eight delegates

elected at large (Henrico Exhibit 12, R. 472). The Com

mittee amendments were proposed by Delegate Andrews,

a resident of Richmond City, after consulting the other

members o f the Richmond-Henrico delegation who were

also residents o f Richmond, but without consulting those

residing in Henrico County (Andrews Dep., R. 80-82).

The Committee amendments were adopted and floor amend

ments offered by the two delegates residing in Henrico

County to restore separate representation were defeated.

The bill with the Committee amendments passed by a vote

11

of 74 to 22. The five Democratic delegates resident in Rich

mond City voted for the bill and the two Republican dele

gates from Richmond City and the two delegates resident in

Henrico County voted against it (Henrico Exhibits 12, R.

474; 13, R. 478).

All of the delegates representing Richmond City and

Henrico County were keenly aware o f the great upsurge

in voter registration during 1964, particularly in Richmond

City during October of 1964, and o f the increasing Negro

vote in Richmond City (Pollard Dep., R. 254; Dervishian

Dep., R. 189, 201). The growing Republican vote in Hen

rico and Chesterfield Counties had also been noted (Pollard

Dep., R. 254). Peculiar interest had been shown by the dele

gates in analyzing the trends indicated by the Congressional

elections o f 1962 and 1964 for the Third District, consisting

of Richmond City and Henrico County as well as Chester

field County and Colonial Heights.

The reasons expressed by some of the five Democratic

incumbents resident in Richmond City for insisting upon the

consolidation o f the two political subdivisions into one dis

trict were summarized as follows:

“ I think that the expressed opinions involved the re

tention in the members of the House of persons of

conservative political philosophy and also concern about

racial relations would be the principal reasons that

have been discussed.” (Sutton Dep., R. 130).

The same delegate testified further, as follows:

“ Q. Picking up right here, Mr. Sutton, getting a

little more specific about the concern for race relations,

was there not some discussion(s) as to whether a

Negro might be elected into the General Assembly

from the Richmond area?

12

“A. That has been discussed.

“ Q. Was it not pointed out in this discussion that

the combination of Richmond and Henrico would tend

to prevent or lessen the chance of a Negro being elected

to the General Assembly, in view of the growing vote

in Richmond?

“ A. That has been discussed.

“ Q. And this was discussed by members of the

present legislature from the Richmond area, the Dem

ocratic members?

“ A. That is correct.” (Sutton Dep., R. 131).

Such discussions were confirmed by other Delegates

(Dervishian Dep., R. 198-200; Herrink Dep., R. 189-191).

The Richmond City member of the Committee on Privileges

and Elections agreed that annexation was not the only

reason for the consolidation (Andrews Dep., R. 91-92).

Another delegate testified that annexation was the only

reason “ argued before the Committee or on the floor o f the

House” (Pollard Dep., R. 245).

The statutes which were enacted combined for the first

time in the history o f the Commonwealth two separate and

independent political subdivisions each of which was entitled

to more than one representative in the House of Delegates

according to the population ratio per delegate then prevailing

under the latest decennial census. It consolidated into a sin

gle multi-member district Richmond City, having a 1960

population o f 219,958 and 67,003 registered voters, and

Henrico County, having a 1960 population o f 117,339 and

34,220 registered voters (Henrico Exhibits 1, R. 375 ; 2, R.

380, 383; 21A, R. 511-513; 22A, R. 517). It awarded the

single district eight delegates to be elected at large by

the voters o f both Richmond City and Henrico County.

13

The excuse publicly assigned for this novel departure

from tradition was the pendency during the special session

o f an annexation proceeding brought by the City of Rich

mond against Henrico County in which the annexation

court had by its written opinion o f April 27, 1964 (Defend

ants’ Exhibit 4, R. 668), and its interlocutory order of

July 31, 1964 (Defendants’ Exhibit 3, R. 663), awarded the

city 17 square miles o f Henrico territory containing ap

proximately 45,000 residents. Only the financial adjust

ments remained for decision. That award was subsequently

refused (R . 698; Crowe Dep., R. 233-234; Wheat Dep., R.

334-335).

Annexation was not the basic motivating cause.1 The

Richmond City member of the Committee on Privileges

and Elections conceded that an allotment of two delegates

to Henrico County, five delegates to Richmond City and

one floater delegate for the county and city together would

have solved all o f the problems claimed to have been

presented by the pending annexation suit (Andrews Dep.,

R. 105-106). Such an amendment was offered in the Senate

and was defeated (Henrico Exhibit 14, R. 479, 480). This

Court has recognized that such was the traditional use in

Virginia o f the “ floterial district” . Davis v. Mann, supra,

footnote 2. (See also Bradshaw Dep., R. 295).

The real reason for combining the city and county into

a single House district was the grave concern of the

Democratic members o f the House o f Delegates resident in

Richmond City over the upsurge in voter registrations

during 1964 (particularly in Richmond City during Octo

ber, 1964), the growing Republican vote in Henrico County,

1 The District Court made no finding on this point, notwithstanding

the fact that the pendency of the annexation proceeding was the only

reason the state authorities suggested for the combination of the two

independent political subdivisions.

14

that a Negro might be elected to the General Assembly from

the Richmond area in view of the increasing voting strength

of Negroes in concentrated areas of the City, and race

relations in general. Retention in the House o f Delegates

o f members from the Richmond area of conservative

political philosophy was the objective that the scheme to

consolidate Richmond City and Henrico County into a

single multi-member district was designed to accomplish.

Such a purpose the evidence plainly establishes.

Never before, so far as is known, in the history of the

Commonwealth have two separate and independent political

subdivisions, each entitled separately and independently

to more than one delegate in the House o f Delegates accord

ing to the population ratio per delegate then existing, been

combined and consolidated into a single district and awarded

delegates jointly to be elected at large by the voters of both

separate and independent political subdivisions. (See Hen

rico Exhibits 23A through 37D, R. 520-655). The chief

objection voiced by one Richmond City Councilman was

that “ it was the only city that would not have had any

individual representation, separate representation” (Wheat

D'ep., R. 334).

Equally Weighted Votes Was Not The Legislative Concern

The District Court considered as controlling the facts

next quoted from its opinion. “ Ideal representation in the

House of Delegates, when Virginia’s total population ac

cording to the 1960 census is distributed among its 100

delegates, is 39,669 persons for each member. * * * Rich

mond alone could justify 5 delegates with 21,613 towards

a sixth. T o have awarded only 5 delegates to Richmond

would have meant that each of its delegates represented

43,911, or 4,242 persons in excess of the norm.” (App. A.

15

p. 6.) However, o f Virginia’s 50 districts which are not

affected by floterial representation, 12 have populations in

excess o f 43,911 per delegate, v iz :

2nd Accomack, Northampton— 1 delegate—47,601 per dele

gate

6th Alleghany, Botetourt, Covington, Clifton Forge— 1

delegate— 45,173 per delegate

16th Russell, Dickenson— 1 delegate— 46,501 per delegate

24th Clarke, Frederick, Winchester— 1 delegate— 44,993

per delegate

26th Hampton— 2 delegates— 44,629 per delegate

28th Fauquier, Warren, Rappahannock— 1 delegate-—44,-

089 per delegate

32nd Carroll, Grayson, Galax— 1 delegate—-45,822 per dele

gate

38th Isle o f Wight, Southampton, Franklin— 1 delegate—

44,359 per delegate

47th Nansemond, Suffolk—-1 delegate—43,975 per delegate

61st Spotsylvania, Stafford, Fredericksburg— 1 delegate—

44,334 per delegate

62nd Tazewell— 1 delegate— 44,791 per delegate

50th-59th Page, Rockingham, Shenandoah, Harrisonburg

— 2 delegates— 44,899 per delegate

(Henrico Exh. 2).

It can hardly be supposed that the Legislature was so

much concerned for mathematical precision with respect

to the City of Richmond when it showed so little concern for

such precision in so many other places.

16

The General Assembly was aware o f the increasing

efforts o f Negroes in Richmond to make effective political

expression. On at least seven occasions between 1947 and

1961 some Negro citizen has sought the Democratic nomi

nation (tantamount to election) for one of Richmond’s seats

in the House of Delegates.2 In 1959, the Negro candidate,

bidding with eight others for one of the seven seats, re

ceived 10,975 votes; but the successful aspirants received

votes ranging from 12,723 to 14,000 (R . p. 71).

In 1964, there were approximately 18,355 Negroes quali

fied to vote in non-federal elections in Richmond City, ap

proximately 52,179 white persons qualified to vote in non-

federal elections in Richmond City (Henrico Exh. 21B),

and approximately 933 Negro and 40,660 white persons so

qualified in Henrico County (Henrico Exh. 22B).

Negroes in Richmond and elsewhere in Virginia have

the most compelling reasons for seeking a change from the

“ conservative” Democratic forces which control Virginia’s

government. The statutes of Virginia, past and present, are

replete with evidence of the age-old preoccupation o f the

General Assembly with establishing and preserving racial

segregation and discrimination as a cherished way of life.3

The dissatisfaction of Richmond’s Negroes with these facets

o f their environment was expressed on November 4, 1964,

when the city’s ten largest Negro precincts cast 14,111 votes

for President Johnson as against 115 for Senator Gold-

water, thus helping to put Richmond in the Democratic

column by a count of 35,662 over 27,196 (Richmond Exh.

2 In the July 13, 1965, Democratic Primary, two Negroes and ten

whites competed for the eight Richmond-Henrico seats. The high

est number of votes for any candidate was 22,610. The eighth highest

number was 14,588. In ninth place was Wm. Ferguson Reid, a Negro,

who received 14,556 votes. ( Richmond Nezvs-Leader, July 14, 1965,

p. 8.)

3 See Appendix D.

17

3). This Court, in N AACP v. Button (1963) 371 U.S.

415, 435 noted: “ W e cannot close our eyes to the fact that

the militant Negro civil rights movement has engendered

the intense resentment and opposition of the politically dom

inant white community of Virginia.”

Six o f the seven delegates and one of the two senators

who live in Richmond reside in “ West End” (Andrews,

Dep., 31, 33; Dervishian, Dep. 106-108) which is probably

the most affluent area in the city (Andrews, Dep. 29, 33).

The other delegate and the other senator live in “ Northside”

(Andrews, Dep. 31, 33). None of the incumbent legislators,

by reason of residence, economic interests or political out

look (especially with respect to race relations), can be said

to reflect the thinking of any considerable number o f resi

dents o f “ East End.”

THE QUESTIONS ARE SUBSTANTIAL

I.

The District Court, citing Fortson v. Dorsey, 379 U.S.

433 (1965), held that the possibility (indeed the certainty)

that all of the delegates may be chosen from one part rather

than from all parts of a multi-member district “ exposes no

defect” in the apportionment scheme, even where the sub

stitution of single-member districts would necessarily

create some constituencies in which persons o f racial or

political minorities would predominate (App. A. pp. 7-9).

In Fortson, the Court made clear its reservation of opinion

whether under the circumstances of a particular case a

multi-member constituency scheme would unconstitutionally

operate to minimize or cancel out the voting strength o f

racial or political elements of the voting population. That

question, unanswered in Fortson, is the exact question pre

sented by the facts in the instant case. Georgia’s 1962

18

Senatorial Reapportionment Act, reviewed in Fortson, re

quired that “ [e]ach Senator must be a resident of his own

Senatorial District” ; but it also provided that “ the Senators

from those Senatorial Districts consisting of less than one

county shall be elected by all o f the voters o f the county in

which such Senatorial District is located.” In considering

this latter proviso, the Court had no occasion to suggest that

all delegates o f a multi-member district might be validly

chosen from one part o f the district. I f such suggestion can

be found in the Fortson opinion, it lies in the quotation from

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964), to which we now

turn.

II.

As the Court began Section V of its opinion in Reynolds,

it noted that it had said all that was necessary to its decision

of the issues then before it. However, to illustrate the propo

sitions that identity in the composition or complexion o f

the two bodies of a bicameral legislature need not follow

from the fact that one criterion controlled the apportionment

o f representation in both houses, the Court did suggest that

“ One body could be composed of single-member dis

tricts while the other could have at least some multi

member districts.” (377 U.S. at 577.)

But, in Section V I of the Reynolds opinion, the Court stated

a more pervasive guide which, for the instant case at least,

overshadows all else which has been written on the subject:

“ What is marginally permissible in one State may be

unsatisfactory in another, depending on the particular

circumstances o f the case.” (377 U.S. at 578.)

Our attention is thus deflected from consideration of the

abstract question whether all the delegates may be chosen

19

from one part of 'a multi-member district to the really per

tinent questions in this case, v iz :

May the Commonwealth of Virginia, where racial dis

crimination under color o f law yet prevails, arbitrarily com

bine two multi-member districts when such results in mini

mizing or cancelling out the voting effectiveness of Negroes

in the City of Richmond ?

May the Commonwealth of Virginia, where racial dis

crimination under color of law yet prevails, arbitrarily re

tain multi-member legislative districting for the City of

Richmond, when single-member districting would neces

sarily produce a predominantly Negro district?

III.

Virginia could have divided Richmond into single-member

districts for both houses of the legislature and thus afforded

every voter in each of such districts an opportunity (equal

to that enjoyed by voters in the forty-six single-member

House of Delegates Districts and the twenty-eight single

member Senatorial Districts) to cast his ballot for that one

o f his neighbors and acquaintances who, in the voter’s per

sonal opinion uninfluenced by city-wide political machina

tions, would best represent him. Such a course would have

comported with the Federal constitutional concept of Equal

Protection in the sense indicated by Mr. Justice Douglas,

dissenting in Fortson v. Dorsey, supra, v iz :

“ But to allow some candidates to be chosen by the elec

tors in their districts and others to be defeated by the

voters of foreign districts is in my view an ‘invidious

discrimination’— the test o f equal protection under the

Fourteenth Amendment” .

Such a course, and only such a course, would have complied

with the view of Virginia’s highest court in Wade v. City of

20

Richmond, 18 Gratt. (59 V a.) 583 (1868) that the appor

tionment of representation in the General Assembly among

the counties, cities and towns, which the Constitution of

1851 effected, was in all reality but a means of reflecting

representation o f “ persons and property comprised in these

local departments.” Such a course, and only such a course,

would have complied with the letter o f the Constitution of

Virginia (1902), as amended, viz [emphasis supplied]:

“ § 41. Number and election o f senators.— The

Senate shall consist o f not more than forty and not

less than thirty-three members, who shall be elected

quadrennially by the voters of the several senatorial

districts on the Tuesday succeeding the first Monday

in November.

“ § 42. Number and election of delegates.— The

House of Delegates shall consist o f not more than one

hundred and not less than ninety members, who shall

be elected biennially by the voters of the several house

districts, on the Tuesday succeeding the first Monday

in November.

“ § 43. Apportionment of Commonwealth into sena

torial and house districts.— The present apportionment

of the Commonwealth into senatorial and house dis

tricts shall continue; but a reapportionment shall be

made in the year nineteen hundred and thirty-two and

every ten years thereafter.

“ § 44. Qualifications of senators and delegates; who

ineligible; removal from district vacates office.— Any

person may be elected senator who, at the time o f elec

tion, is actually a resident of the senatorial district and

qualified to vote for members of the General Assembly;

and any person may be elected a member o f the House

of Delegates who, at the time of election, is actually a

resident of the house district and qualified to vote for

members o f the General Assembly. * * * The removal

21

of a senator or delegate from the district for which he

is elected shall vacate his office ”

The creation of multi-member districts for either house is

patently a legislative subversion of the above quoted pro

visions o f the State Constitution. In Reynolds v. Sims,

supra, the Court observed:

“ In those States where the alleged malapportionment

has resulted from noncompliance with state constitu

tional provisions which, if complied with, would result

in an apportionment valid under the Equal Protection

Clause, the judicial task of providing effective relief

would appear to be rather simple.” (377 U.S. at 584.)

By its mere failure to provide single-member districts for

the City of Richmond, the State made it reasonably certain

that the votes o f the citizens o f an identifiable predominantly

Negro constituency would be absorbed into the larger and

predominantly white community and thereby be rendered as

ineffective as if they had not been cast. The 10,975 votes cast

for the Negro candidate in the 1959 Democratic Primary

were simply submerged by the votes cas«£by the majority of

the city’s electorate for the slate o f candidates which had the

most influential endorsement. With single-member district

ing, some o f those 10,975 votes would have been effective.

Not only did the Legislature fail to adopt the course pre

scribed by the State’s Constitution which would have ren

dered meaningful and effective the elective franchise of

Richmond’s Negro citizens; the Legislature further widened

the gap between the text and the application of the Consti

tution by enlarging the district for the purpose o f further

diluting or submerging the votes of Richmond’s Negro cit

izens. What had, or would have been, a 42% potential vot

ing effectiveness of Richmond’s Negroes in electing five

22

delegates to the General Assembly was reduced to a 29.2%

potential voting effectiveness in electing eight delegates to

the General Assembly.

That such a merger, in Virginia, was an abridgment of

the right to vote because of race and color in violation o f the

Fifteenth Amendment appears to be clear. Just as Go-million

v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (I960), struck down Alabama’s

attempt to nullify Negroes’ political effectiveness by zoning

them out o f the City o f Tuskegee, so should fall Virginia’s

patent attempt to nullify the political effectiveness of Rich

mond’s Negro citizens by zoning them into a larger district

in which their number will be overwhelmed. As in Gomillion

is suggested, judicial approval o f this manuever “ would sanc

tion the achievement by a State o f any impairment o f voting

rights whatever so long as it was cloaked in the garb o f the

realignment of political subdivisions” or legislative appor

tionment (364 U.S. at 345).

“ ‘The [Fifteenth] Amendment nullifies sophisticated

as well as simple-minded modes of discrimination.’ ”

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, supra.

These appellants have not contended and do not contend

that any state is required to carve out legislative districts

so as to insure (or make possible) representation by persons

o f any particular race, religion or place of national origin.

W e are in agreement with so much of Mr. Justice Douglas’

dissent in Wright v. Rockefeller, 376 U.S. 52, 62, 66

(1964), as is quoted in the opinion of the Court below.

Specifically, we agree that “ government has no business

designing electoral districts along racial or religious lines.”

What is here contended is that government should not com

bine electoral districts to deny effective political expression

from those who are confined within racial or political lines.

23

As this Court has noted in Forison v. Dorsey, supra,

the precise questions here presented have not been settled.

Unquestionably, the resolution of these issues will have

far reaching effect upon the meaningfulness of the franchise

to Negro people in their quest for their rightful share of

the opportunities which are America’s promise to all. The

past and current efforts o f the legislative and executive arms

of our national government to enforce the Fifteenth Amend

ment will amount to naught if a state may meet and over

come the increasing political strength of Negroes in any

given area by expanding the political constituency from time

to time so as to submerge their votes in the votes of the

larger white community.

CONCLUSION

It is respectfully submitted that the questions here pre

sented are substantial and important and that they should be

considered and decided by this Court.

Richmond, Virginia

August 6, 1965

Sam u el W . T ucker

H enry L. M arsh , III

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

Attorneys for Appellants

APPENDIX A

1

U N ITED STA TE S D ISTR IC T COU RT FOR TH E

EA STE RN D ISTR IC T OF V IR G IN IA

At Alexandria

Civil Action No. 2604

Harrison Mann, et al.

v.

Levin Nock Davis, et al.

ORDER ON PETITIONS AND COMPLAINTS OF INTER-

VENORS FROM HENRICO COUNTY, CITY OF RICHMOND

AND SHENANDOAH COUNTY

Upon consideration of the intervening petition and com

plaint o f Simeon A. Burnette, et al., designated as the

Henrico County intervenors, the intervening petition and

complaint o f William S. Thornton, et al., designated as the

City of Richmond intervenors, and the intervening petition

and complaint o f Jesse D. Funkhouser, et al., designated as

the Shenandoah County intervenors, the answers thereto,

the evidence adduced thereon, as well as the arguments of

counsel, on brief and orally, the court for the reasons stated

in its opinion this day filed, which is adopted as its findings

o f fact and conclusions of law, orders as follows: 1

1. That the petitions and complaints o f the Henrico

County and the City of Richmond intervenors be, and they

are hereby, dismissed, the respondents thereto recovering

their costs o f the said intervenors;

2

2. That the petition and complaint o f the Shenandoah

County intervenors be, and they are hereby, sustained in

respect to the apportionment o f representation o f that

county in the House of Delegates;

3. That the State and local election officials who are de

fendants to the said intervening petition and complaint of

Shenandoah County be, and each of them is hereby, enjoined

and restrained from acting under and pursuant to so much

o f Chapter 2 o f the Acts o f the General Assembly o f V ir

ginia, Extra Session 1964, as declares the representation

in the House o f Delegates for the 50th and 59th districts;

that the court now reapportions the said districts so that

the counties o f Page, Rockingham and Shenandoah and

the City of Harrisonburg shall be represented jointly by two

delegates; that the reapportionment of the 50th and 59th

districts o f Virginia as aforesaid shall be effective for the

elections, both primary and general, o f members of the

House o f Delegates from the counties o f Page, Rocking

ham and Shenandoah and the City of Harrisonburg in the

year 1965 and thereafter until the General Assembly of

Virginia shall provide a Constitutionally valid apportion

ment of representation in the House o f Delegates for

Shenandoah County; and 4

4. That the court hereby approves the reapportionment

Acts o f the General Assembly of Virginia adopted at its

Extra Session in December 1964, insofar as such approval

may be required to remove any question or doubt o f the

3

validity of any legislation which has been, or may be, passed

by the General Assembly since the adoption of the said re

apportionment Acts.

Nothing further remaining to be done in this action, it

is ordered stricken from the docket, and this order is final.

A lbert V. B ryan

United States Circuit Judge

W alter E. H offm an

United States District Judge

O ren R. L ew is

United States District Judge

April 9th, 1965.

4

U N ITE D STA TE S D ISTR IC T COU RT FO R T H E

E A STE R N D ISTR IC T OF V IR G IN IA

At Alexandria

Civil Action No. 2604

Harrison Mann, et al.

v.

Levin Nock Davis, et al.

(Argued March 10, 1965 Decided April 9, 1965)

Before B ryan , Circuit Judge, and L ew is and H offm an ,

District Judges.

OPINION

A lbert V. B r ya n , Circuit Judge:

Virginia’s 1964 reapportionment of the State into dis

tricts for the election of delegates and senators in her

General Assembly, following our invalidation of the 1962

5

redistricting,1 is here attacked as denying Fourteenth

Amendment equal protection of the laws. The assault is made

in three separate intervening petitions in the original action,

each dealing with a local problem, by certain citizens of

Henrico County, the City of Richmond and Shenandoah

County. W e think only Shenandoah can prevail.

Henrico County

The grievance asserted by these intervenors is that

Henrico County and Richmond were placed in a single dis

trict, No. 36, for representation in the House of Delegates,

rather than each made an independent district. Combined,

these two political subdivisions were given 8 delegates, but

Henrico pleads for 3 delegates o f its own, leaving the re

maining 5 to Richmond. The injury from the consolidation,

according to the county, is that as Richmond has a voting

power greater than Henrico, the city will be able to elect

all 8 delegates and Henrico will have no representation by

its own citizens.

This result, says Henrico, is due to a general disregard by

the General Assembly of the guide lines and ground rules

thus far enunciated for legislative apportionment by the

Supreme Court. E.g. Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186 (1962) ;

1 Mann v. Davis, 213 F.Supp 577 (1962), affirmed sub. nom. Davis v. Mann,

377 U.S. 678 (1964). By order entered September 18, 1964 this court restored

its injunction which had been suspended during the appeal. Thereupon the

Legislature adopted a new apportionment in December 1964. The statute re

lating to the State Senate appears as Chapter 1, and the enactment relating to

the House of Delegates as Chapter 2, of the Acts of Assembly, Extra Ses

sion 1964.

6

Gray v. Sanders, 372 U.S. 368 (1963 ); Westberry v.

Sanders, 376 U.S. 1 (1964 ); Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S.

533 (1964 ); WMCA, Inc. v. Lomenzo, 377 U.S. 633

(1964); Maryland Committee v. Tawes, 377 U.S. 656

(1964 ); Davis v. Mann, 377 U.S. 678 (1964) ; Roman v.

Sincock, 377 U.S. 695 (1964) ; Lucas v. Colorado General

Assembly, 377 U.S. 713 (1964 ); Fortson v. Dorsey, 379

U.S. 433 (1965). Our examination o f the record discloses

no such trespasses or fouls. To demonstrate the correctness

o f this conclusion, we review the 1964 reapportionment (the

A ct), touching particularly upon the features on which

Henrico found its accusations.

Ideal representation in the House of Delegates, when

Virginia’s total population according to the 1960 census is

distributed among its 100 delegates, is 39,669 persons for

each member. Richmond had a population of 219,958,

Henrico 117,339. Applying these figures, it appears that

Henrico would be entitled to 2 delegates and wanting but

3,668 residents for a third. Richmond alone could justify 5

delegates, with 21,613 towards a sixth. To have awarded

only 5 delegates to Richmond would have meant that each

o f its delegates represented 43,911, or 4,242 persons in ex

cess of the norm. With Henrico* not quite earning 3 dele

gates, but Richmond due more than 5, the solution of the

Virginia Assembly was to give the two areas 8 delegates

jointly. There would then be 42,164 persons per delegate,

a representation fairly nearing the par of 39,669.

A multi-member district, though linking more than one

political subdivision, is not Constitutionally impermissible.

7

Fortson v. Dorsey, supra, 379 U.S. 433 (1965). A multi

county or a county-city district is also legal. Id. But the

possibility that a delegate or delegates may be chosen from

one part o f a district— whether a multi-county or a county-

city district— rather than from another exposes no defect

in the allotment. Id. In passing, it is at least noteworthy

that Henrico made no objection in 1962 when the reappor

tionment act gave Henrico 1 delegate and then assigned 8

delegates jointly to Richmond and Henrico. While this dis

tribution was in effect in 1963, we are told that a number

o f the 8 winning candidates, although resident in Richmond,

received more votes in Henrico than did the candidates

from that county. This would seem to refute somewhat

Henrico’s insistence that its citizens prefer to have their

delegates come from Henrico.

The multi-member policy here does not have the “ un

desirable features” mooted in Lucas v. Colorado General

Assembly, supra, 377 U.S. 713, 731 with footnote 21

(1964). The unification does not constitute so spacious or

“ populous” a territory as to demand the establishment of

“ identifiable constituencies.” Indeed, Henrico now pledges

its willingness to have 3 delegates elected at large from

among its whole population of 117,339 and without a smaller

constituency than its entire area.

The effect o f the Act has not been to obliterate the tradi

tional integrity in Virginia o f city and county lines. The

custom was sanctioned in Davis v. Mann, supra, 377 U.S.

678, 686 (1964). The individuality of Henrico and Rich

mond is observed by the design o f a separate senatorial

district for each. W e see no inconsistency in allocating

senators on a different basis from delegates. Such a varia

tion has been authoritatively approved, when, as presently,

8

it may tend to “ balance off minor inequities.” Reynolds v.

Sims, supra, 377 U.S. 533, 577, 579 (1964).

Physical factors could reliably have directed the judg

ment o f the General Assembly in determining upon the

union of Richmond and Henrico. They form a compact and

contiguous territory. I f they may not agree politically, con-

cededly their interests are interknit and common in many

aspects. The county is the residence of hundreds of business,

professional and otherwise occupied persons plying their

callings in the city. In fact, while the two are distinct

governmental units, the courthouse of the county is situate

well within the city’s corporate limits. At all events, the

Act does not in any degree devalue the vote in either Rich

mond or Henrico below the Constitutional standard of

weight and fineness, “ one person, one vote.”

City of Richmond

Certain Richmond Negro residents question the fusion of

the city and Henrico County for the election o f delegates

on the ground that it deprives Negro citizens o f a chance

to elect one o f their race to the General Assembly. They

point out that the population o f Richmond consists of 92,331

non-white and 127,627 white persons; that in Henrico the

non-white residents number 6,070, the white 111,269; and

that the potential vote of Negroes in Richmond is, by the

coadunation, reduced from 42% (the percentage of non

white in Richmond) to 29% (the percentage of non-whites

in the aggregate population o f the city and Henrico.)

Further, they suggest that the Negro communities in

Richmond are so located that any division of the city into

9

S fairly equal segments, each embracing a sufficient number

o f inhabitants for a delegate, would create 1 or more dis

tricts in which Negroes would be the majority. Additionally,

they say that if the city were divided into 2 substantially

equal districts with the allotment o f 1 o f Richmond’s 2

senators to each district, the colored population in at least 1

might elect a senator.

Consequently, these intervenors suggest that Richmond

be assigned 5 delegates apart from Henrico, and that the 5

be distributed, 1 to a district, among 5 substantially equal

districts. Likewise, they ask that the city be fairly split into

2 senatorial districts. These contentions are underbraced by

advertence to the Virginia constitutional injunction that

legislators be elected by the voters of the several senatorial

and house districts, and that apportionment of the “State”

into such districts be made every ten years.§§ 41, 42 and 43.

From this they conclude that these clauses command legis

lative allocation, both within and without city and county

marches, by population and not according to existing

governmental units. Omission of such delineations inside

the city and State-wide, the intervenors aver, violates the

Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, as a deprivation of

equal protection o f the election laws and abridgement of

the right to vote. W e disagree.

To begin with, we reaffirm our earlier declaration of the

validity o f conjoining Richmond and Henrico. Moreover, as

we have also shown, adherence to municipal boundaries in

establishing legislative districts has been declared to be

altogether free of legal infirmity. Furthermore, the racial

exclusion decried in Gotnillion v. Lic/Jitfoot, 364 U.S. 399

(1960) and universally forbidden is not evident. Neither

10

Richmond, nor any other city or county in Virginia has

in her history ever been sub-districted. Even councilmen

for the local government of Richmond are elected at large,

and this without question by either race.

The concept of “ one person, one vote” we understand,

neither connotes nor envisages representation according to

color. Certainly it does not demand an alignment of districts

to assure success at the polls o f any race. No line may be

drawn to prefer by race or color.

As Justice Douglas, though in dissent but obviously

undeniably, tartly put it in Wright v. Rockefeller, 376 U.S.

52, 62, 66 (1964):

“ The fact that Negro political leaders find advantage

in this nearly solid Negro and Puerto Rican district is

irrelevant to our problem. Rotton boroughs were long a

curse o f democratic processes. Racial boroughs are also

at war with democratic standards.”

Page 66:

“ . . . The principle o f equality is at war with the notion

that District A must be represented by a Negro, as it

is with the notion that District B must be represented

by a Caucasian, District C by a Jew, District D by a

Catholic, and so on. . . . O f course race, like religion,

plays an important role in the choices which individual

voters make from among various candidates. But

government has no business designing electoral districts

along racial or religious lines. . . . ”

11

Previously Justice Douglas had said for the Court in

Gray v. Sanders, supra, 372 U.S. 368, 380 (1963) :

. . The concept o f political equality in the voting

booth contained in the Fifteenth Amendment extends to

all phases o f state elections, . . . and, as previously

noted, there is no indication in the Constitution that

homesite or occupation affords a permissible basis for

distinguishing between qualified voters within the

State.”

Shenandoah County

Certain citizens of Shenandoah County protest they have

been deprived of Constitutional rights by the 1964 assign

ment of delegates in the 50th and 59th districts. The

former, which has been assigned 1 delegate, comprises Page,

Rockingham, Shenandoah Counties and the City o f Har

risonburg. The 59th district encompasses only Rockingham

County and Harrisonburg but it is also given 1 delegate.

Harrisonburg is geographically within Rockingham County.

Over-representation o f Shenandoah County under the 1962

reapportionment was noted in Davis v, Mann, supra, 377

U.S. 678, 688; it had “ one seat in the Virginia House”

although its population was 21,825 as compared to the

“ ideal ratio o f one delegate for each 39,669 persons.”

In 1964 Shenandoah’s 21,825 people were leagued with

Rockingham’s 39,559, Page County’s 15,572, and Harrison

burg’s 12,842, increased to 13,804 by an annexation in

1962.* Obviously this readjustment erects a district of

* These figures are taken from the face of the complaint of the Shenandoah

Intervenors. The U.S. Bureau of Census’ U.S. Census o f Population : 1960

General Population Characteristics, Virginia. Final R ep ort P C (1 )-4 8 B , reveals

Rockingham’s population as 40,485 and Harrisonburg’s as 11,916 rather than

12,842 prior to annexation.

12

90,760, far above criterion of 39,669. Rockingham and

Harrisonburg are saved from injustice by their additional

delegate, but Shenandoah with Pag'e suffers from a clear

under-representation.

Invidious discrimination has thus been visited upon

Shenandoah. With primary elections for the General

Assembly scheduled for July of this year, and candidates’

filing times therefor expiring in April, correction of this

injury to Shenandoah County cannot await the convening

o f the General Assembly in 1966. Consequently, we are

required to act to prevent the watering down of the Shenan

doah votes. Until the General Assembly can rectify the

inequity, we must set aside the 1964 apportionment o f the

50th and 59th districts. In lieu of the present provision for

them, the court will order that the counties o f Page, Rock

ingham and Shenandoah and the City o f Harrisonburg be

assigned 2 delegates to represent all four of these political

subdivisions jointly. This adjustment will effectuate a rep

resentation o f 45,380 persons per delegate. While this is

above the proper ratio, we do not deem it an unfair approach

in the circumstances.

Recapitulation

The record does not authorize attribution to the General

Assembly or caprice or an unacceptable motive in the

Henrico and Richmond reapportionment. To the contrary,

a firm foundation may be seen for it. For Shenandoah

County, however, the imbalance in representation is obvious

and fatal.

13

An order will be entered dismissing the intervening com

plaints o f Henrico and Richmond, but sustaining the claim

of the Shenandoah intervenors, with the relief we have

prescribed. The order will also express our approval o f the

Act insofar as such approval is required to remove any

question or doubt o f the validity of any legislation which

has been, or may be, passed by the General Assembly since

the adoption o f the Act, our order of September 18, 1964

having required the General Assembly acting thereafter to

make a Constitutionally valid reapportionment o f the State

before undertaking any other legislation.

APPENDIX B

1

IN T H E U N ITE D STA TE S D ISTR IC T COURT

FO R T H E EA STE R N D ISTR IC T OF V IR G IN IA

At Alexandria

Civil Action No. 2604

H ARR ISO N M AN N , et al.,

v.

LE V IN NOCK D A V IS, et al.,

ORDER ON MANDATE

This action came on to be heard upon the mandate of

the Supreme Court of the United States affirming the judg

ment order of this Court entered November 28, 1962, upon

the motions of the plaintiffs and intervening plaintiffs for

an order on said mandate and the argument o f counsel;

upon a consideration of all of which it is

2

D eclared, A djudged and O rdered :

1. That the Governor o f Virginia and the Attorney Gen

eral be dismissed as parties defendant to this action;

2. That the motion o f the defendants to dismiss the com

plaint and intervening petition be denied;

3. That the acts o f the General Assembly of Virginia,

approved April 7, 1962, appearing as Chapter 635, page

1266, and Chapter 638, page 1269 of the 1962 Acts o f the

Assembly of Virginia, deny the plaintiffs and plaintiff-in

terveners and those persons similarly situated the equal

protection of the laws in contravention of the Fourteenth

Amendment o f the Constitution of the United States, and

that the said acts for that reason are void and of no effect;

4. That the order entered by this court on November 28,

1962 be in all respects reaffirmed but the enforcement o f said

order be further stayed until December 15, 1964 inso

far as necessary to afford ample time for the General As

sembly of Virginia to be called and convened in special ses

sion, if the Governor or the requisite number o f members

o f the General Assembly are so advised, for the purpose of

enacting constitutionally valid reapportionment statutes for

both houses of the General Assembly, and enact statutes

to effectuate said reapportionment by providing for the

election of members o f both houses of the General Assembly

from the districts of the State as reapportioned;

3

5. That, for the reasons set forth in the opinion filed

this day, the terms of the present members o f the House of

Delegates shall not be terminated by force of the said order

before, but shall terminate upon, the expiration o f the

terms for which they were elected in November, 1963 or

in any special election thereafter, that is on the day before

the second Wednesday of January, 1966;

6. That, for the reasons set forth in said opinion, the

terms o f the present members of the Senate, who were

elected in November 1963 or in any special election there

after, shall not be terminated by force of the said order

before, but shall terminate upon, the expiration o f the

terms o f the members o f the House of Delegates elected in

November, 1963 or thereafter -as aforesaid, that is the day

before the second Wednesday in January, 1966;

7. That the motion o f the plaintiffs and plaintiff-inter

veners that the present General Assembly be enjoined at this

time from enacting any legislation other than the said re

apportionment statutes be denied; but by way o f a declara

tory judgment the court now states that after the enact

ment of a constitutionally valid reapportionment statute

the present General Assembly may until the 2nd Wednesday

in January 1966 consider and pass such legislation as it

deems necessary or proper in the public interest, unless

before that date through special elections a General As

sembly is chosen in conformity with the new reapportion

ment statute.

8. That the motion o f the defendants for a continuance

is also denied, in view of the stay herein granted of the

effectiveness o f the order issued by this Court on November

28, 1962.

4

9. That the plaintiffs and plaintiff-interveners recover

o f the defendants their statutory costs, assessed or assess

able in the Supreme Court and in this court, and that the

motion of the plaintiff-inteveners for an allowance of counsel

fees as a part o f said costs is denied; and

10. That if the steps stated in paragraph 4 hereof for

reapportionment be not taken before December 15, 1964,

or if taken they do not meet the requirements of a constitu

tionally valid reapportionment, then the plaintiffs, the plain-

tiff-interveners and any part ( sic) hereafter granted leave to

intervene, may apply to the court for such further orders

as may be required; and jurisdiction of this action is hereby

retained for entry o f such other orders as may be necessary

or proper.

United States Circuit Judge

United States District Judge

-United States District Judge

September 18, 1964.

5

IN T H E U N ITED STA TE S D ISTR IC T COURT

FO R T H E EA STE RN D ISTR IC T OF V IR G IN IA

A t Alexandria

Civil Action No. 2604

H A R R ISO N M AN N et al„

v.

LE V IN N OCK D A V IS et at,

(Argued September 10, 1964 Decided 1965)

Before B r ya n , Circuit Judge, and H offm an and L ew is,

District Judges.

OPINION UPON ORDER ON MANDATE

A lbert V. B ryan , Circuit Judge:

A foremost concern in framing the order on the mandate

o f the Supreme Court affirming our original decree is the

question of the maximum period in which the present,

1963, General Assembly elected under the condemned

statute may still function and with what powers. In our

opinion it must expire as to both houses not later than the

2nd Wednesday in January 1966.

6

W e think the 1963 Assembly necessarily is empowered

to enact the requisite reapportionment laws. There is no

other body to do so, and unless its jurisdiction is recognized

for this purpose the State would be helpless to accomplish

the reapportionment. The Supreme Court has tacitly ap

proved this accordance o f provisional vitality to the existing

legislature. Maryland Committee v. Tawes, 377 U.S. 656,

675 (1964 ); Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 585 (1964)

adopting the view expressed by Justice Douglas concurring

in Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186, 250 footnote 5.

W e think, also, that after the 1963 Assembly has enacted

a constitutionally valid reapportionment statute— but not

before then— and during the interval between its adoption

and the commencement of the terms of the Senators and

Delegates chosen in the 1965 elections, vide post, the A s

sembly should not be restrained from considering and pass

ing such legislation as it considers necessary or proper in

the public interest. I f the present legislature could not act

in this interim, a potentially dangerous interregnum could

result, for there would be no legislature available in an

emergency. Moreover, if this authority were not conceded,

special elections for the creation of a new General Assembly

would have to be called immediately after the passage of the

reapportionment statute. This would mean an election of

Delegates to serve for a matter of months, when a primary

election o f Delegates is probable in July and a regular

general election is set for November, 1965. That would

be an undue burden upon the State elective processes. In

these exigencies general principles o f equity, as noted by the

Supreme Court in the decisions just cited, sustain an order

permitting such a temporary continuance o f the powers of

the current legislature.

7

In the effort to minimize disruption of the State’s elective

processes as far as possible, but still consistently with our

first order, it is well to recall those processes and consider

their application here. When our finding of invalidity in the

legislative apportionment was made in November 1962,

both houses o f the General Assembly were to stand for elec

tion the following year, 1963. During the temporary stay

of enforcement of this finding, the 1963 election proceeded

upon the unconstitutional apportionment. Delegates were

then chosen for 2-year terms expiring on the 2nd Wednes

day in January 1966, and the Senators were selected for

4 years each, that is until the 2nd Wednesday in January

1968.

Orderly procedure would, therefore, suggest that the

1963 House of Delegates should continue in being until the

expiration o f their terms in January 1966. Cf. Reynolds v.

Sims, supra, 377 U.S. 533, 585 (June 15, 1964). In the

November 1965 general election a House of Delegates will,

under the Virginia law, be elected to assume their duties on

the 2nd Wednesday in January 1966. O f course, the 1965

House would be serving under the new apportionment.

As noted, however, the 1963 Senate would not normally

leave office until January 1968. Elected on a void pattern

of representation, there is no warrantable foundation for its

accreditation beyond January 1966. Further, if it should be

allowed to survive until 1968, the General Assembly— from

January 1966 to January 1968— would be composed of a

House of Delegates elected on one (a valid) scheme of ap

portionment with a Senate elected upon another (in

8

validated) plan. This too, would be constitutionally un

justifiable. Together the two houses in a bicameral system

form a unitary and entire Legislature. For equality of

popular reprsentation they are mutually complementary,

and constitutional validity is not fulfilled if one house is

deliberately permitted to lag behind the other in seeking

fairness o f representation. Cf. Maryland Committee v.

Tarwes, supra, 377 U.S. 656, 673.

Incidentally, practical difficulties might develop if the