Supplemental Brief of Plaintiffs-Appellees with Cover Letter

Public Court Documents

July 5, 1977

17 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bolden v. Mobile Hardbacks and Appendices. Supplemental Brief of Plaintiffs-Appellees with Cover Letter, 1977. f1f01a93-cdcd-ef11-b8e8-7c1e520b5bae. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1f0ef016-2fc0-4dc9-ae04-171d40fb5a74/supplemental-brief-of-plaintiffs-appellees-with-cover-letter. Accessed February 05, 2026.

Copied!

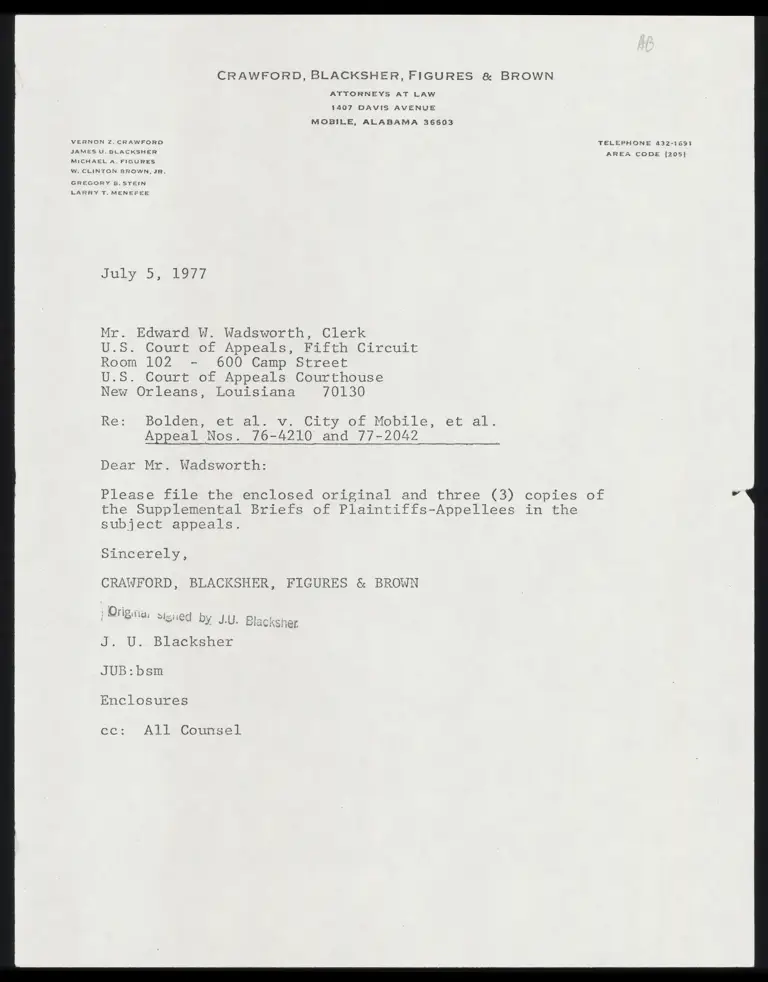

CRAWFORD, BLACKSHER, FIGURES & BROWN

ATTORNEYS AT LAW

1407 DAVIS AVENUE

MOBILE, ALABAMA 36603

VERNON Z. CRAWFORD TELEPHONE 432-1691

JAMES U. BLACKSHER AREA CODE {[205) {2

MICHAEL A. FIGURES

W. CLINTON BROWN, JR.

GREGORY B. STEIN

LARRY T. MENEFEE

July 5, 1977

Mr. Edward W. Wadsworth, Clerk

U.S. Court of Appeals, FPifth Circuit

Room 102 - 600 Camp Street

U.S. Court of Appeals Courthouse

New Orleans, Louisiana 70130

Re: Bolden, el al. v. City of Mobile, et al.

Appeal Nos. 76-4210 and 77-2042

Dear Mr. Wadsworth:

Please file the enclosed original and three (3) copies of >

the Supplemental Briefs of Plaintiffs-Appellees in the

subject appeals.

Sincerely,

CRAWFORD, BLACKSHER, FIGURES & BROWN

Origins sigued by Ju. gr.

J. U. Blacksher

JUB:bsm

Enclosures

cc: All Counsel

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NOS. 76-4210 & 77-2042

WILEY L. BOLDEN, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

VS.

CITY OF MOBILE, et al.,

Defendants-Appellants.

As Bn, —

On Appeal From The United States District Court

Southern District of Alabama, Southern Division

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF

JAMES U. BLACKSHER

LARRY T. MENEFEE

CRAWFORD, BLACKSHER,FIGURES & BROWN

1407 DAVIS AVENUE

MOBILE, AL 365603

EDWARD STILL

601 TITLE BUILDING

BIRMINGHAM, AL 35203

JACK GREENBERG

ERIC SCHNAPPER

10 COLUMBUS CIRCLE

NEW YORK. MN. VY. 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellees

iN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

POR. THE PIFTH CIRCUAT

NOS. 76-4210 & 77-2042

WILEY 1.. BOLDEN, er al.

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

¥S.

CITY OF MOBILE, et al.,

Defendants-Appellants.

POST-ARGUMENT

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF OF PLAINTIFFS-APPELLEES

WILEY L. BOLDEN, ET AL.

SR

Plaintiffs-Appellees herein submit their supplemental

brief, pursuant to the Court's instructions at oral argument

on June 13, 1977, commenting on the effect on this appeal

of Kirksey v. Board of Supervisors of Hinds County, F.2d

(53th Civ., May 31, 1977)(en banc), and David v. Garrison,

F.28 {5th Civ., June 10, 1977).

SUMMARY

The en banc opinion of this Court in Kirksey establishes

principles which remove all doubt that the district court's

judgment striking down at-large elections in Mobile should be

affirmed. Virtually every contention made by the appellant

Mobile City Commissioners is squarely repudiated by Kirksey,

including their primary argument that Washington wv. Davis,

426 1.8,:229, 26 S.Cr. 2040, 48 L.5d4.24:597 (19768), and Village

of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Development Corp.,

3.8. .,187 3.0. 555, 50 1..%d.24 430 (1377), prohibit Finding

unconstitutional dilution of black voting strength unless the

mul timember election scheme was created with racially

discriminatory intent. Rather, Kirksey provides, regardless of

the Legislature's motives, the State violated the fourteenth

and fifteenth amendments in 1911 when it adopted an apportionment

plan for Mobile that perpetuated and failed to ameliorate then

existent purposeful exclusion of blacks from the political process,

which had been accomplished in 1901. Defendants could not show

substantial evidence that this intentional discrimination

against black citizens has no remaining residual effects. To

the contrary, the great preponderance of evidence showed, and

the district judge found, that black Mobilians do not today

enjoy equal access to the political process. |

Kirksey also rejects the City Commissioners' contention

that the district court should have preserved the at-large

commission form of government in deference to substantial

local governmental interests. The en banc decision reaffirms

Ve

the rule of this Court and the Supreme Court that the more

fundamental rights of citizens to a full and effective vote

outweigh such concerns.

The trial court's opinion sub judice has none of the

deficiencies criticized by the panel majority in David wv.

Garrison, and though David seems to set up a stricter burden

of proof than this Court has previously required of dilution

case plaintiffs, the record in this appeal clearly satisfies

it.

Nevertheless, we respectfully submit that the evidentiary

standards used in David are in irreconcilable conflict with

those announced in Kirksey and that this panel is bound to

follow the en banc decision. Indeed, it may well be that

David has been overruled by Kirksey. Although the former

decision was handed down ten days after Kirksey, the opinion

cites the petition for rehearing in Kirksey as still pending.

Thus the David panel apparently did not have the benefit of

the en banc decision when it wrote its opinion.

I.

KIRKSEY FULLY AFFIRMS THE LEGAL STANDARDS

AND CONCLUSIONS ADOPTED BY THE DISTRICT

JUDGE HERE

The central defense of the City Commissioners during trial

and in this appeal is the legal contention that the ''race-

proof" circumstances surrounding the adoption of Mobile's

at-large elected commission government in 1911, in light of

Washington v. Davis, save the system from equal protection

attacks. The district court's rationale for rejecting

Defendants' theory is virtually identical to this Court's en

banc teachings in Kirksey. And, without question, the

Commissioners failed to meet the evidentiary burden required

by Kirksey to avoid the conclusion of unconstitutional dilution.

A. Kirksey approves the district court's

reconciliation of dilution caselaw with

Washington v. Davis.

In his opinion, the district judge noted Washington v.

Davis's proviso that a neutral statute may not be applied so

as invidiously to discriminate and concluded:

To hold that the 1911 facially neutral

statute would defeat rectifying the invidious

discrimination on the basis of race which

the evidence has shown in this case would

Fly in the face of this principle.

423 F.Supp. at 398. The discrimination referred to by the

court is the protracted State scheme of black disenfranchise-

ment that extended from 1901 to 1965, id. at 397, and the still

continuing nonresponsiveness of local officials to blacks’

interests, id. at 400. This reasoning exactly coincides with

the rule articulated in Kirksey:

Where a plan, though itself racially

neutral, carries forward intentional

and purposeful discriminatory denial

of access that is already in effect,

it is not constitutional... Ils benign

nature cannot insulate the redistricting

government entity from the existent taint.

Op. at 15~16. $

The en banc opinion makes it explicitly clear that, while

the apportionment plan before it is court-ordered, Op. at 1

2

the constitutional principles it enunciates "have equal

application" to legislatively adopted schemes, Op. at 8. The

court carefully divided its discussion into separate sections,

Sections I, II and III dealing with "The law of unconstitutional

reapportionment" and its application to Hinds County, and

Section IV confronting the '"mon-constitutional grounds' governing

the Court of Appeals’ supervision of court-ordered plans. In

so doing, Kirksey acknowledges that "a court-ordered

reapportionment plan is held to higher standards than a legislative

i

In Kirksey the redistricting plan was found to be racially

neutral. Here, however, the trial court did not entirely endorse

the neutrality of the 1911 statute, saying there could be little

doubt that the Legislature then was aware of the dilution caused

by at-large elections and would have employed them specifically

to diminish blacks' voting strength had they not already been

barred from the ballot. 423 F.Supp. at 397. Furthermore, said

the court, racial considerations had prevented the modern

legislators from changing the existing system to provide blacks

equal access to the election process. 1d.

plan. A legislative plan need only meet constitutional

standards." Op. at 26. Accordingly, the constitutional

standards approved in Sections I, II and III are squarely

applicable to the instant appeal.

The district judge reached his legal conclusions by the

same route followed by the en banc Kirksey Court: he relied

on Washington's reminder that invidious purpose "may often be

inferred from the totality of the relevant facts," 423 F.Supp.

at 396, noted that Washington failed "to expressly overrule or 2 P Y

comment on White, [Reese v. Dallas County], Chapman, Zimmer,

Turner, Fortson, Reynolds or Whitcomb," id. at 398, and therefore

refused to conclude that Washington v. Davis had suddenly replaced

- -5a-

the existing judicial standards for scrutinizing facially

neutral multimember systems that dilute minorities' votes

with a new requirement that initial discriminatory purpose

be shown, id. Kirksey uses essentially the same analysis to

hold that, "while Washington v. Davis and Arlington Heights

sharpen the emphasis on purpose and intent," they do not

modify the dual modes of unconstitutionality firmly established

in the voting rights caselaw of the Supreme Court and the Fifth

Circuit: (1) a facially neutral election system purposefully

created to exclude blacks or (2) a racially innocent system

that nevertheless perpetuates existent purposeful discrimination

against black voters. Op. at 18.

The district court cited the fundamental importance that

the Supreme Court has placed on each citizen's "inalienable

right to full and effective participation in the political

processes," 423 F.Supp. at 398, quoting Reynolds v. Sims, 377

U.S. 533, 565 (1964), making it unconstitutional to infrirge

precious voting rights either by express racial classifications,

by racial gerrymanders, or by schemes that operate to dilute

the "quality" of representation for minorities, 423 F.Supp. at

399. Compare Kirksey, supra, Op. at 5-6, 19. When social and

political realities dilute the effectiveness of blacks' votes,

a "litany of past history” of official racial discrimination

can satisfy the purpose and intent requirement of Arlington

Heights, Kirksey, supra, Op. at 10. Kirksey plainly approves

the district court's holding that an aggregate of circumstances

similar to those cited in White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755

(1373), and Zimmer v. McReithen, 485 F.24 1297 (5th Cir. 1973)

(en banc), aff'd sub nom. East Carroll Parish School Bd. v.

Marshall, 424 U.S. 636 (1978), make out a violation of both

the fourteenth and fifteenth amendments . 2 Op. at 9: 423 F.Supp.

at 335.

B. The burden of rebuttal placed on defendants

by Kirksey provides an additional reason for

affirming the judgment below.

According to the en banc Kirksey opinion, where the State

has in the past intentionally excluded blacks from the electoral

process, officials defending apportionment plans that would

otherwise perpetuate such past discrimination must come forward

with substantial evidence that its residual effects are

dissipated and that black voters now have equal access to the

political process. Op. at 11-12. In the instant case blacks

were disenfranchised at the time Mobile's at-large Commission

was adopted, and purposeful discrimination against blacks

seeking to vote is admitted to have persisted until 1965.

A.295-98. The defendant Commissioners' primary argument for

2

The trial court also found a cause of action available

based on Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42 1.58.C;

§1973, and Plaintiffs urge affirmance of this holding as well.

See Appellees’ Brief, pp. 44-50.

present equality of access is squarely rejected by Kirksey,

which says mere reliance on blacks' unimpeded right to vote

and run for election is not enough. Op. at 8 n.10. Compare

Appellants' Brief, pp. 8, 35. Defendants offered no affirmative

evidence to rebut the extensive proof that the political

choices and interests of black Mobilians are consistently

overwhelmed by the bloc-voting white majority, responding to

sometimes openly racist campaign appeals.

Indeed, the record in this appeal far outstrips the

evidence in Kirksey, which this Court thought to contain

"almost every significant factor indicative of denial of

access to the political process.” Op. at 10. All ten of the

indicia recounted in the en banc opinion, pp. 9-10, are present

here: (1) no blacks ever elected in city-wide or county-wide

races; (2) poll taxes and literacy tests; (3) segregation

principles adopted by political parties; (4) property ownership

requirement to run for office (City Commission qualifying

fee struck down by federal court order; see 423 F.Supp. at 387

nn. 3); (5) disproportionate education, employment, income

level and living conditions between whites and blacks; (6) bloc

voting (only alleged in Kirksey, but exhaustively proved in

the instant case); (7) majority vote requirement; (8) no

single-shot voting (place requirement); (9) systematic

exclusion of blacks from juries; and (10) dual school system.

And there was much additional evidence relied on by the district

court to conclude Mobile's at-large elections are unconstitutional:

close analysis of the candidacies of over a dozen blacks and

blac k-supported whites from 1962 to 1974, including the racist

campaign tactics that ensured their defeat; the testimony of

an expert historian, an expert statistician, two expert political

scientists and a dozen local politicians; computer analyses

of most City and County election returns since 1962; and

extensive documentary and testimonial evidence of employment

discrimination against blacks by the City, underrepresentation

of blacks on appointed boards and committees, laggard attention

to the drainage problems in black residential areas, racial

discrimination in paving and resurfacing streets and sidewalks,

and official insensitivity to special black community concerns

like police brutality, cross-burning and fair housing.

In every respect, then, the Kirksey decision compels

affirmance of the district court's finding of unconstitutional

dilution. Moreover, the en banc opinion reemphasizes the

bankruptcy of the defendants' familiar complaint that federal

courts should not disturb state and local governmental

structures just because they are instruments for denying black

citizens equal protection of the law.

It is clear, however, that the mere

fact that an apportionment plan may

satisfy some legitimate governmental

goals does not automatically immunize

it from constitutional attack on the

ground that it has offended more

fundamental criteria.

Op. at 25, quoting Robinson v. Commissioners Court, 505 F.2d

674, 680 {5th Cir. 1974).

IY.

THE OPINION AND JUDGMENT REVIEWED IN THIS

APPEAL ARE UNASSAILABLE EVEN WITH THE MORE

ONEROUS STANDARDS OF DAVID wv. GARRISON,

WHICH CONFLICT WITH THOSE ESTABLISHED BY

THE EN BANC COURT IN KIRKSEY.

The majority opinion of the panel in David v. Garrison

candidly concedes it is breaking new ground and that "'[t]he

court is trying to find its way in this developing area of

law." Slip Op. at 3706. It is clear that the panel engaged

the developing vote dilution principles without the assistance

of the May 31, 1977, en banc decision in Kirksey v. Board of

Supervisor of Hinds County, which is cited as still under

submission. Slip Op. at 3705. Plaintiffs-Appellees

respectfully submit that, in remanding the trial court findings

for further consideration, David relies on a novel legal

approach to the problem of dilutive multimember districts that

is fundamentally at odds with the en banc Kirksey decision.

A petition for rehearing and suggestion of rehearing en banc

was filed by the black plaintiffs in David on or about June

23, 1977, seeking reconciliation of the panel decision with

Kirksey. In the instant appeal, the Court is bound to follow

the en banc opinion to the extent it conflicts with David v.

Garrison.

<=10-

Indeed there is a basic divergence of philosophy between

these two most recent precedents. Both reaffirm the duty of

federal courts to enjoin the maintenance of apportionment

schemes that unconstitutionally minimize minority electoral

power. But whereas Kirksey finds reason enough in recently

abated official discrimination against blacks to require the

State to bear the burden of justifying neutral plans that

perpetuate blacks' disadvantaged position, David presumes that

plaintiffs have a heavy burden of proving that prior purposeful

devices to restrict black voters still are causally linked to

their present inferior status. David views the single-member

3 and calls for upsetting district remedy with a jaundiced eye

legislatively prescribed multimember plans only if the proof

of State complicity in dilution meets a high evidentiary

standard of certainty. Slip Op. at 3704, 3706.

David v. Garrison cannot be squared with Kirksey when it

places the burden on plaintiffs to prove that undisputedly

inferior living conditions, municipal services and city

4

employment ~ weighing on blacks are the fault of governmental

But see Connor v. Finch, 45 U.S.L..W. 4523, 4530 (May 31,1977).

/

Making voting rights plaintiffs prove how many ''qualified"

black persons had applied for municipal job classifications in

which blacks are grossly underrepresented is a tougher burden

of proof than is even required in Title VII cases. International

Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United States, 45 U.S.L.W. 4506,4510

(May 31, 1977).

11%

officials, even in the face of historical discrimination

against blacks. David, supra, Slip Op. at 3708-09. Referring

aggrieved black citizens to federal fair employment laws

rather than providing the remedial opportunities of equal

political access is a direct affront to the contrary teaching

of Kirksey. Compare David, supra, Slip Op. at 3708, with

Kirksey, supra, Op. at 13. David cites with approval the

suggestion in McGill v. Gadsden County Commission, 535 F.2d

277. (3th Cir. 1976), that plans adopted when blacks could not

vote must be racially neutral, Slip Op. at 3709, whereas

Kirksey holds that such a plan is unconstitutional if it tends

to perpetuate the prior intentional exclusion. The conclusion

in David that past racial discrimination was not proved

responsible for the continued absence of black elected officials

because blacks were not afraid to register and vote, squarely

conflicts with Kirksey's holding that defendants must prove

the contrary proposition. Compare David, supra, Slip Op. at

3709, with Kirksey, supra, Op. at 14.

But measured even by the more difficult tests set up in

David v. Garrison, the opinion of the district judge in the

instant case stands up. To begin with, Mobile is not nearly

as small a multimember district as Lufkin, Texas, a factor that

apparently keyed the especially close scrutiny the panel gave

the evidence in David. Slip Op. at 3707. In Mobile the court

received considerable, unrebutted testimony about the special

problems blacks must overcome to wage successful city-wide

-12-

campaigns, and its conclusion that blacks lack equal practical

access to candidate slating was based on this and other factors

of discouragement. 423 F.Supp. at 388-89. Its finding of

nonresponsiveness is thoroughly explicated and founded on

substantial evidence. The unequal provision of municipal

services was both observed by the court personally and measured

by documents taken from city records. Id. at 389-92. The

court's reference to municipal employment discrimination was

buttressed by two prior judicial determinations. Id. at 389.

The residual effects of historical racism on the political

system were shown by hard evidence of polarized voting and

racist literature and were attested to by both politicians

and expert political scientists. The district court pointed

to the stark residential segregation along racial lines and

the persistent margin by which the black registration rate

lags that of the whites. 423 F.Supp. at 386. Without repeating

at length matters previously briefed, suffice to say that

no serious contention could be made here that the district

court should have made "more explicit and concrete findings."

David, supra, Slip Op. at 3709.

-13-

CONCLUSION

Kirksey v. Hinds County controls this appeal and commands

that the district court be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted this 5th day of July, 1977.

/ y

sy of [fp brbice.

37 LL i

T/ARRY T. MENEFEE

CRAWFORD, BLACKSHER, FIGURES & BROWN

1407 DAVIS AVENUE

MOBILE, ALABAMA 36603

EDWARD STILL, ESQUIRE

601 TITLE BUILDING

BIRMINGHAM, ALABAMA 35203

JACK GREENBERG, ESQUIRE

ERIC SCHNAPPER, ESQUIRE

SUITE 2030

10 COLUMBUS CIRCLE

NFW YORK, NH. .Y. 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellees

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I do hereby certify that on this the 5th day of July, 1977,

I served a copy of the foregoing SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF upon counsel

of record, C. 8S. Arendall, Fsquire, P.0. Box 123, Mobile, AL 36601,

Fred G. Collins, Esquire, City Hall, Mobile, AL 36601 and Charles

S. Rhyne, Esquire, 400 Hill Building, Washington, D. C. 20006,

by depositing same in United States Mail, postage prepaid.

2 A x

{fetomey for Plaintiffs-Appellees

Wy TAN