Brief on the Merits in Support of Petitioners Submitted Amicus Curiae with Appendix

Public Court Documents

December 28, 1973

148 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Brief on the Merits in Support of Petitioners Submitted Amicus Curiae with Appendix, 1973. f47fd675-54e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1f0ff4a8-f3d7-4d06-bbfc-a20bd7bae679/brief-on-the-merits-in-support-of-petitioners-submitted-amicus-curiae-with-appendix. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

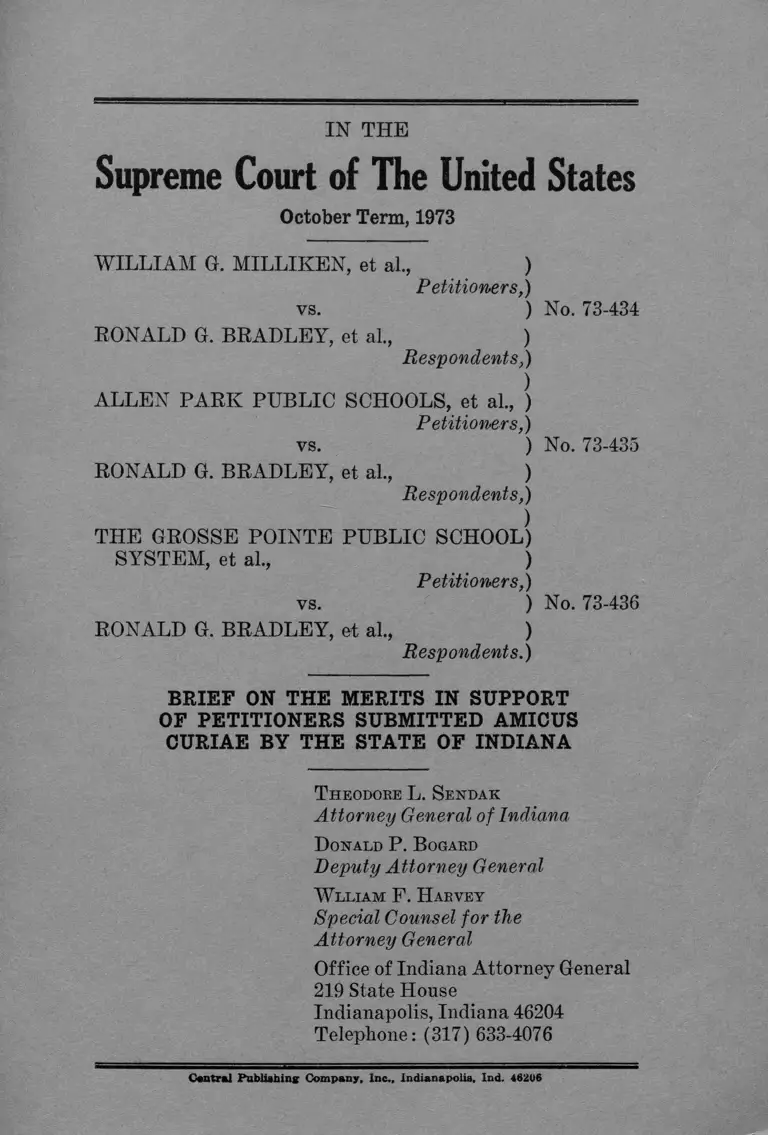

IN THE

Supreme Court of The United States

October Term, 1973

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al., )

Petitioners,)

vs. )

RONALD G. BRADLEY, et al., )

Respondents,)

)

ALLEN PARK PUBLIC SCHOOLS, et al., )

Petitioners,)

vs. )

RONALD G. BRADLEY, et al., )

Respondents,)

)

THE GROSSE POINTE PUBLIC SCHOOL)

SYSTEM, et al., )

Petitioners,)

vs. )

RONALD G. BRADLEY, et al., )

Respondents.)

BRIEF ON THE MERITS IN SUPPORT

OF PETITIONERS SUBMITTED AMICUS

CURIAE BY THE STATE OF INDIANA

T heodore L. Sendak

Attorney General of Indiana

D onald P. B ogakd

Deputy Attorney General

W lliam F. H arvey

Special Counsel for the

Attorney General

Office of Indiana Attorney General

219 State House

Indianapolis, Indiana 46204

Telephone: (317) 633-4076

No. 73-434

No. 73-435

No. 73-436

Central Publishing Company. Inc., Indianapolis. Ind. 46206

Page

Table of Authorities ....................................................... iii

Opinion Below ................................................................ 2

Jurisdiction .................... 2

Consent of Parties ......................................................... 2

Questions Presented .................................... 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved . . . 3

Interest of the Amicus Curiae..................................... 6

A. Michigan ............. 10

B. Indiana ................................................................ 11

1. Indianapolis Public School System, Marion

County, Indiana........................................... 12

2. State Officials in Indiana.......................... 13

3. Additional School Districts Within Marion

County, Indiana ......................................... 13

4. Additional School Districts Outside Marion

County, Indiana ......................................... 14

C. Indiana and Michigan Compared ................... 18

D. The Metropolitan Rem edy................................ 19

Statement of the Case ................................................... 21

Argument I A Federal District Court does not have

the power to order the transfer or ex

change of students from one school dis-

TABLE OF CONTENTS

l

TABLE OF CONTENTS— Continued

Page

triet found to be guilty of de jure seg

regation across political boundaries to

other school district found not to be

guilty of any de jure violations........... 22

Argument II The Fourteenth Amendment does not

require a state to remove black children

from schools in which they constitute

a majority of the students enrolled, or

a substantial minority, in order to mix

them with white children in other school

districts, so that the black children

will always be in a racial minority . . . . 24

A The Constitutional Definition . . . . 24

B A School Boards Duty ................... 27

C This Case and the New Constitution

for Metropolitan Am erica............... 28

Conclusion ........................................................................ 30

Certificate of Service .................................... 32

li

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases Page

Bradley v. Milliken, (6th Cir., 1973) 484 F.2d 215 . . . 2

Bradley v. School Board of Richmond, Virginia, 462

F.2d 1058 (4th Cir. 1972) ............................8,23,27,29

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) . . . 8,

21, 24, 26

Brunson v. Board of Trustees, 429 F.2d 820 (4th Cir.

19?0) ............ 20,29

Beal v. Board of Education, 369 F. 2d 55 (6th

Cir., 1965) ................. 27

Downs v. Board of Education, 366 F.2d 988 (10th

Cir., 1964) .................................................... .............. 27

Gayle v. Browder, 352 U.S. 903 (1956) ..................... 26

Green v. County School Board of New Kent, County,

Vir., 391 U.S. 430 (1968) ..................................... 15,21

Haney v. County Board of Education of Seiver County

410 F.2d 920 (8th Cir. 1969) .................................. 27

Higgins v. Bd. of Ed. City of Grand Rapids, Mich.,

No. CA 6386 (W.D. Mich. July 18, 1973) ............... 28

Holmes v. City of Atlanta, 350 U.S. 879 (1955) ....... 26

Keyes v. School District No. 1, 93 S.Ct. 2686 (1973) . .8, 21,

24, 26,28

Lee v. Macon County Board of Education, 448 F.2d

746 (5th Cir. 1971) .................................................. 27

Mapp v. Bd. of Ed. of Chattanooga, 329 F. Supp. 1374

(E.D. Tenn. 1971) 1378 .............................. ............. 28

Mayor and City Council of Baltimore City v. Dawson,

350 U.S. 877 (1955) ................................................. 26

in

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Cases—continued Page

Muir v. Louisville Park Theatrical Assn., 347 U.S.

971 (1954) .................................................................... 26

Northcross v. Board of Education of Memphis City

Schools, 397 U.S. 232 (1970) ....... ..................... .. 29

Northcross v. Bd. of Ed. Memphis, Tenn., No. 73-1954;

No. 73-1667 (6th Cir., Dec. 4 ,1 9 7 3 )......................... 21

Offerman v. Nitkowski, 378 F. 2d 22 (2nd Cir., 1967) .. 27

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896) ..................... 21

Raney v. Board of Education of Gould School Dist.,

391 U.S. 443 (1968) ..... .................................. 29

San Antonio Independent School Dist. v. Rodriquez,

411 U.S. 1 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2 8 , 30

Sealy v. Dept, of Public Instruction, 252 F. 2d 898

(3rd Cir., 1957) ............................... .............. 27

Spencer v. Kugler, 326 F. Snpp. 1235, (D.N.J.

1971) ................... ...9,23,26,30

Springfield School Committee v. Barksdale, 348 F.2d

261 (1st Cir., 1965) ............. ............................... 27

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1 (1971) .......... ...........11,15, 21,22, 23, 25, 26,27

ESA v. Board of School Commissioners of the City of

Indianapolis (S.D. Ind., 1971) 332 F. Supp. 655 ..6,11

USA & Buckley et al v. Board of School Commis

sioners of the City of Indianapolis, et al. (No. 73-

1968 through 73-1984) ..................................6, 9,10,14, 20

U.S. v. Scotland Neck City Board of Education, 407

U.S. 484 (1972) ........................................................... 29

Wright v. Council of Emporia, 407 U.S. 451 (1972)

Constitution of State of Indiana, Article 8,

Section 1 ............. ................. .................. . 27, 29

IV

Cases—continued Page

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS

Article 8, Section 1 of the Constitution of the State

of Indiana ................................................................... 7

Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution .. 3

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Con

stitution .......................................................4,12,26,28,31

Tenth Amendment to the United States Constitution .. 29

STATUTES

28 U.S.C. §1254(1) . . . . _ ........................................... 2

28 U.S.C. §1343(3) ...................................................... 12

28 U.S.C. § 2201 .............................................................. 12

28 U.S.C. § 2202 .............................................................. 12

42 U.S.C. §1983 ............................................................ 12

42 U.S.C. § 1988 .............................................................. 12

42 U.S.C. § 2000c-6 ........................................................ 5

Rule 42 of the Rules of the Supreme Court of the

United States .............................................................. 2

OTHER AUTHORITIES

United States Department of HEW

Digest of Educational Statistics, 1971 ed.................. 30

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

v

IN THE

Supreme Court of The United States

October Term, 1973

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al., )

Petitioners,)

vs. ) No. 73-434

RONALD G. BRADLEY, et al., )

Respondents,)

ALLEN PARK PUBLIC SCHOOLS, et al., )

Petitioners,)

vs. ) No. 73-435

RONALD G. BRADLEY, et al., )

Respondents,)

THE GROSSE POINTE PUBLIC SCHOOL)

SYSTEM, et al., )

Petitioners,)

vs. ) No. 73-436

RONALD G. BRADLEY, et al., )

Respondents,)

BRIEF ON THE MERITS IN SUPPORT

OF PETITIONERS SUBMITTED AMICUS

CURIAE BY THE STATE OF INDIANA

The State of Indiana, by Theodore L. Sendak, Attorney

General of Indiana, Donald P. Bogard, Deputy Attorney

General and William F. Harvey, Special Counsel for the

Attorney General, pursuant to Rule 42 of the Rules of the

Supreme Court of the United States, submits its brief

amicus curiae in support of the Petitioners in the above-

entitled cause.

1

2

OPINION BELOW

The opinion below, filed by the United States Court of

Appeals for the Sixth Circuit (hereafter Sixth Circuit) is

reported as Bradley v. Milliken, (6th Cir., 1973) 484 F.2d

215 (Certiorari Joint Appendix pp. 110a-240a) (hereafter

cert. app.).

JURISDICTION

The United States Supreme Court has jurisdiction to

review this case by writ of certiorari pursuant to 28 U.S.C.

§ 1254(1), and has accepted it for such purposes by grant

ing said writ on November 19, 1973.

CONSENT OF PARTIES

This amicus brief by the State of Indiana is filed pur

suant to Rule 42 of the Rules of the United States Supreme

Court and consent of the parties is not required pursuant to

Rule 42(4).

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

I.

Whether, in a school desegregation case involving a

metropolitan area in which one school system has been

found to be de jure segregated and all other districts found

not to be de jure segregated, a federal district court can

enter orders regarding the transfer or exchange of pupils,

against those other school systems or districts which are

geographically close to the segregated system when there

is no finding against those school systems or districts, no

finding that they were formed as a part of a state sup

ported de jure segregated system, and no finding that they

exist in order to perpetuate such a system, when those

3

orders have the effect of developing massive busing and

student transfer programs among the various districts

and which were entered solely to establish a court-

acceptable ‘ ‘ deseg’regation” plan in the one segregated

school system?

II.

Whether the state can be compelled to entirely reorga

nize local school districts in metropolitan areas within the

state in order to remove only black children from one school

system and only white children from another school sys

tem and exchange them between systems when only one

school system was found to be illegally segregated, when

there were no findings against any other school system

and when the only alleged “ act” of the “ State” was pur

ported to have been committed entirely within the ille

gally segregated system, but which in fact had no causal

connection whatever upon racial percentages or numbers

in any school system.

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED

The Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution

provides as follows:

“ No person shall be held to answer for a capital,

or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment

or indictment by a grand jury, except in cases arising

in the land or naval forces, or in the militia, when in

actual service in time of war or public danger; nor

shall any person be subject for the same offence to be

twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be com

pelled in any criminal case to be a witness against him

self ; nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, with

out due process of law; nor shall private property be

taken for public use, without just compensation.

4

The Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Con

stitution provides in part as follows:

§ 1. All persons born or naturalized in the United

States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citi

zens of the United States and of the state wherein they

reside. No state shall make or enforce any law which

shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens

of the United States; nor shall any state deprive any

person of life, liberty, or property, without due process

of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction

the equal protection of the laws.

§ 5. The congress shall have power to enforce, by

appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.

The Civil Right Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000c provides

in part as follows:

§ 2000c. Definitions

As used in this subchapter—

(a) “ Commissioner” means the Commissioner of

education.

(b) “ Desegregation” means the assignment of stu

dents to public schools and within such schools without

regard to their race, color, religion, or national origin,

but “ desegregation” shall not mean the assignment

of students to public schools in order to overcome

racial imbalance.

(c) “ Public school” means any elementary or sec

ondary educational institution, and “ public college”

means any institution of higher education or any tech

nical or vocational school above the secondary school

level, provided that such public school or public col

lege is operated by a State, subdivision of a State, or

governmental agency within a State, or operated wholly

or predominantly from or through the use of govern

mental funds or property, or funds or property derived

from a governmental source.

5

(d) “ School board’ ’ means any agency or agencies

which administer a system of one or more public

schools and any other agency which is responsible for

the assignment of students to or within such system.

Pub.L. 88-352, Title IV, § 401, July 2,1964, 78 Stat. 246.

§ 2000c-6..

(a) Whenever the Attorney General receives a com

plaint in writing—

(1) signed by a parent or group of parents to the

effect that his or their minor children, as members

of a class of persons similarly situated, are being

deprived by a school board of the equal protection

of the laws, . . .

and the Attorney General believes the complaint is

meritorious and certifies . . . that the institution of

any action will materially further the orderly achieve

ment of desegregation in public education, the Attor

ney General is authorized, after giving notice of such

complaint to the appropriate school board or college

authority and after certifying that he is satisfied that

such board or authority has had a reasonable time to

adjust the conditions alleged in such complaint, to in

stitute for or in the name of the United States a civil

action in any appropriate district court of the United

States against such parties and for such relief as

may be appropriate, and such court shall have and shall

exercise jurisdiction of proceedings instituted pur

suant to this section, provided that nothing herein

shall empower any official or court of the United

States to issue any order seeking to achieve a racial

balance in any school by requiring the transportation

of pupils or students from one school to another or one

school district to another in order to achieve such

racial balance, or otherwise enlarge the existing power

of the court to insure compliance with constitutional

standards. The Attorney General may implead as de

fendants such additional parties as are or become nec

essary to the grant of effective relief hereunder.

6

INTEREST OF THE AMICUS CURIAE

The State of Indiana submits its brief amicus curiae

since this case involves similar questions of law to a case

arising out of Indiana which is currently on appeal to the

United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit

(hereafter Seventh Circuit). U.S.A. & Buckley et al. v.

Board of School Commissioners of the City of Indianapolis,

et al., (No. 73-1968 through 73-1984) (hereafter Indianap

olis). In that case neither the State of Indiana nor the In

diana General Assembly were named parties. However,

named as added defendants in the court below—the United

States District Court for the Southern District of Indiana

(hereafter District Court)—were Otis R. Bowen, as Gov

ernor of the State of Indiana, Theodore L. Sendak, as At

torney General of the State of Indiana, Harold H. Negley,

as Superintendent of Public Instruction of the State of In

diana, and the Indiana State Board of Education, a public

corporate body (hereafter State Defendants). The State

Defendants were added to the lawsuit after the District

Court had made a finding of de jure segregation on the

part of the Indianapolis Public School System (hereafter

IPS), 332 P. Supp. 655, (1971), and which was properly on

appeal to the Seventh Circuit at the time the State Defend

ants and nineteen school districts were added as

defendants.

The Indiana case, like the case at bar, is an extremely

complex piece of school desegregation litigation involving

the transfer or exchange of pupils from IPS which has been

found guilty of de jure segregation, across township,

county, city, and town boundaries to twenty-three other

school districts in eight (8) counties found not to be guilty

of any de jure violations.

7

The State of Indiana, pursuant to its Constitution,

Article 8, Section 1 (1851), and statutes duly enacted, has

provided for a system of common schools wherein tuition

shall be without charge and “ equally open to all.” The ef

fectuation of those provisions has always been in the de

velopment and control of the local schools in the State of

Indiana, since school systems are created locally, controlled

locally, and are primarily financed locally (by issuance of

their own school bonds and the taxation of local property).

The function of the State agencies in education, such as the

Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction and the

Indiana State Board of Education, is a service function

designed to assist the local schools in their various indi

vidual programs.

In the Indianapolis Standard Metropolitan Statistical

Area (hereafter ISMS A) there are 44 independent school

systems with a total 1972 enrollment of approximately

261,482 school children. Twenty-one (21) of those school

systems are now involved in litigation in the District Court

and in the Seventh Circuit in a case which is similar to

this case. The enrollment of those twenty-one (21) school

systems for 1972 was approximately 205,175 school children,

(attached appendix following p. A-63).

The disposition of the Detroit case in the Sixth Circuit

has caused a very serious threat to the continued existence

of the school systems in the ISMSA, many of which have

existed in their present or predecessor form since before

the Civil War, and as early as 1838.

The primary interest of the amicus is in explaining to

this Court how the Detroit case affects those Indiana school

systems, and why the Sixth Circuit in the decision below

was incorrect and should be reversed.

The purpose of the amicus is also to suggest to this Court

that the decision now presented for review is of a signifi-

8

cance which equals that of Brown v. Board of Education,

347 U.S. 483 (1954). The result here can have the effect of

placing almost the whole of metropolitan development in

the United States under a federal judicial superin

tendency, and such a case previously has not been before

this Court. This effect has staggering implications, as is

evident from examining the attached United States Bureau

of Census Charts of urbanized areas in Indiana, Illinois

and Michigan from the 1970 census (attached appendix

following p. A-63).

The amicus brief is limited in its primary discussion to

that part of the Court of Appeals opinion which permits the

development of a “ Metropolitan Area Desegregation Plan,’

484 F.2d 215, 250 Cert. App. at page 173a, for the Detroit

Metropolitan area.

In this case, unlike Keyes v. School District No. 1, 93

S.Ct. 2686 (1973), there are multi-school districts involved,

against which no finding of racial discrimination has been

entered, but like Keyes, there was a finding of discrimina

tion in one school district. Unlike Bradley v. School Board

of Richmond, Virginia, 462 F.2d 1058 (4th Cir. 1972), a ff’d,

93 S.Ct. 1952 (1973), there is no history of racial discrimi

nation in the additional school district defendant-inter-

venors, and no finding that the out-of-Detroit City schools

are or ever have been anything other than integrated

school systems. Similar to Richmond is the percentage of

blacks in the city school systems, with the Detroit School

City being about 64% black, and Richmond about 70%

black. Also, as in Richmond, the Detroit school city can

desegregate now and eliminate racially identifiable schools.

In the Indianapolis case, the IPS schools are 40% hlack

and 60% white.

9

This case commenced as a school desegregation case

against the Detroit City School system, and the district

court wishes to end it as a case which alters the racial

imbalance between that school system and the added de-

fendant-intervenors. In that way it is much like the Indi

anapolis case (see attached Appendix, pp. 11 and 12), and

much like Spencer v. Kugler, 326 F.Supp. 1235, (D.N.J.

1971), a ff ’d, 404 U.S. 1027 (1972), in which this Court re

jected an attack made upon the racial imbalance found in

New Jersey school systems.

The essential fact in this case is not that the Detroit City

schools were segregated, according to the district court, but

that the added school systems were not found to be segre

gated. Those school systems are to carry the judicial bur

den. They were not heard, were not tried, and were not

present at trial; no evidence was offered against them, and

no findings were made against them. Nevertheless, they

are the subject of the district court’s orders in Detroit.

The critical factual difference between this case and

Indianapolis is that in the Indianapolis case, after IPS had

been found to be guilty of de jure segregation in the first

lawsuit (see attached appendix p. A-5) and had appealed

that finding to the Seventh Circuit, the added school de

fendants and the State Defendants were brought into court

in a second lawsuit (see attached appendix p. A-6) by a

Complaint in Intervention and an Amended Complaint in

Intervention and did present evidence, did have an oppor

tunity to cross examine, and those added school districts

were found not to he segregated school systems. Neverthe

less, principally on the basis of the Sixth Circuit’s decision

in this case (see attached appendix, p. A-22) orders were

entered against the added school districts. In the most

10

recent district court entry in Indianapolis (see Supple

mental Decision, attached appendix, p. A-61) the court has

“ delayed” action (as in Michigan), pending action by the

Indiana General Assembly, and if the General Assembly

‘ ‘ defaults ’ ’ then the district court has stated it will act. As

in Michigan there was no constitutional violation by any

added defendant school district, but substantial orders

have been entered against them which have been vacated,

but which on February 16, 1974, will rise in an even greater

magnitude than as originally ordered.

A.

Michigan

There are two categories of defendants in this case when

examined pursuant to the requirement that a constitutional

wrong be found. First, there are the state defendants; the

Governor, the Attorney General, the State Board of Edu

cation, and the Superintendent of the Detroit Public

Schools. The district court entered findings of de jure

segregation against the Detroit City defendants, with in

volvement by the State of Michigan officials, 338 F.Supp.

582, a ff’d, 484 F.2d 215, 258 (1973), Cert, App. 189a.

Secondly, there is the “ Wayne, Oakland, and Macomb

counties group, ’ ’ which consists of 53 separate and inde

pendent school systems. This group includes 780,000 school

children and their parents, and could possibly include as

many as 85 separate and independent school systems

with an enrollment of approximately 1,000,000 pupils cov

ering an area of approximately 1,952 square miles (Peti

tion for Certiorari, Michigan, pages 5, 19, 52). Against this

group, except for the School City of Detroit, there were

no findings of illegal segregation entered, and in fact no

such findings at all.

11

Nevertheless, because that group of school systems and

school children exist in close proximity to the Detroit

Public Schools they were made available for effecting a

Detroit remedy. In short, a remedy has been imposed

without a wrong. Compare, Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklen-

burg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1971).

B.

Indiana

The Indianapolis case commenced on May 31, 1968, when

the United States of America filed a Complaint in the

District Court which was assigned cause number IP-68-C-

225. The action by the United States was brought pursuant

to 42 U.S.C. §2000c-6(a) and (b), and was tried by the

Court on July 12-21, 1971, Defendants in the aforemen

tioned complaint were The Board of School Commissioners

of the City of Indianapolis, Indiana, its Superintendent of

Schools, and members of its Board.

On August 18, 1971, the Court issued its ‘ ‘ Memorandum

of Decision” permanently enjoining defendants, their suc

cessors in office, officers, agents, employees and all those

in active concert or participation with them from “ dis

criminating on the basis of race in the operation of the

Indianapolis School System,” and further ordered the

defendants to take seven steps to “ fulfill their affirmative

duty to achieve a nondiscriminatory school system.” 332 F.

Supp. 655, 680. Affirmed 474 F.2d 81 (7th Cir., 1973).

Cert, denied 407 U.S. 920, 93 S.Ct. 3066 (1973).

A part of the District Court’s findings in the first Indi

anapolis case was that that school board constructed three

high school buildings in 1961, 1963, and 1967, the placement

of which constituted acts of de jure segregation.

12

On September 10, 1971, the defendants filed their Notice

of Appeal to this Court from the final judgment entered

on August 18, 1971.

On September 14, 1971, a “ Motion to Intervene as Party

Plaintiff” and a Complaint in Intervention were filed by

Donny Brurell Buckley and Alycia Marquese Buckley who

purported to intervene as representatives of a class com

prised of Negro school age children in Marion County,

Indiana who attended only IPS.

On October 21, 1971, an Amended Complaint was filed by

intervening plaintiffs which named Edgar D. Whitcomb, as

Governor of the State of Indiana, Theodore L. Sendak, as

Attorney General of the State of Indiana, and The Indiana

State Board of Education, a public corporate body, as

added defendants. Jurisdiction under the Amended Com

plaint was extended to include 42 U.S.C. §§ 1983 and 1988,

28 U.S.C. §§ 1343(3), 2201 and 2202, and the Fourteenth

Amendment to the United States Constitution,

A trial was held on the Amended Complaint and An

swers thereto on June 12, 1973 through July 6, 1973, and

was reopened by the court on its own motion on July 18,

1973. In that trial the parties were as follows:

1.

Indianapolis Public School System

Marion County, Indiana

The IPS system is one of eleven (11) in Marion

County, Indiana, and is the twenty-nineth largest in

the United States. In its 1972-73 enrollment the IPS

system had 97,833 students with a racial composition

of 60 percent white and 40 percent Mach. If re

organized utilizing all available students in the

ISMSA it would be the fifth largest school district

in the United States, fitting between Philadelphia and

the current Detroit system.

13

Seventeen days before the commencement of the

second trial, the District Court held its findings in

the first trial were res judicata in the second trial,

hence the findings against IPS stood as before.

2.

State Officials in Indiana

In the second trial the intervening plaintiffs added

the Governor, the Attorney General, the Indiana State

Board of Education, and the Superintendent of Public

Instruction as added defendants. Findings were

entered against only the latter two parties, and those

findings were that the findings against IPS in the

first trial, i.e., that the placement of three high schools

constructed in 1961, 1963, and 1967, constituted acts

of de jure segregation which were “ imputed” to the

state officials because there was in the State Board

of Education a power to review and approve site selec

tions for purposes of insuring minimum health and

safety standards. These were the only findings against

any State officials in Indiana. (Attached appendix,

p. A-22)

3.

Additional School Districts Within

Marion County, Indiana

There are ten (10) school systems located in Marion

County, Indiana, in addition to IPS. Of those, eight

(8) are township schools and two are school systems

for the City of Beech Grove, Indiana and the Town

of Speedway, Indiana. Their combined enrollment in

1972-73 was approximately 77,611 school children.

These school systems have never been illegally segre

gated nor have they ever operated dual school systems,

and the District Court so found. (Attached appendix,

p. A-23).

14

Additional School Districts Outside

Marion County, Indiana

There are ten (10) school districts located outside

Marion County, Indiana, in six (6) other counties,

which were never a part of any Marion County school

system, and which, in several instances, have existed

since before the Civil War. Their combined 1972-73

enrollment was approximately 27,131 school children.

These schools have never been segregated nor have

they ever operated dual school systems, and the

District Court so found. (Attached appendix, p.

A-23).

On July 20, 1973 the District Court issued its “ Memo

randum of Decision.” See attached Appendix, p. A-l. In

that Decision the Court found acts of de jure segregation

on the part of the Indianapolis Public Schools in the place

ment of three (3) high schools, and that those acts were

imputed to the Indiana State Board of Education and the

State Superintendent of Public Instruction. However, the

Court found that there were no de jure acts of segregation

attributable to the added defendant school districts. The

District Court also found that the desegregation of the In

dianapolis Public School System cannot be accomplished

with its own boundaries primarily because of the possibility

of resegregation “ within a matter of two or three years.”

The District Court in the Indianapolis case stated that

it was possible to desegregate IPS within its own boun

daries, stating at page 7 of its Decision:

“ In other words, it is apparent that as a sheer exer

cise in mathematics, it would be possible for this Court

to order desegregation of IPS on a 58.9%-41.1% basis,

or some basis similar thereto, so that no school could,

for the time being, be racially identifiable as a black

school. . . ” (attached appendix p. A-12).

4.

15

But, contrary to Green v. County School Board of New

Kent County, Virginia, 391 U.S. 430 (1968) and Swann v.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, supra, the Dis

trict Court was not looking for a plan that promises real

istically to work now, but one that promises to work for all

time.

Further, in that Decision, the District Court stated in

Conclusion of Law number 2 on page 22 (attached appen

dix, p. A-26) :

“ The Superintendent of Public Instruction, The In

diana State Board of Education, and other responsible

agents and agencies of the State of Indiana, and the

State itself, have each practiced de jure segregation,

both by commission and omission.”

yet the Court never ordered any of the above to do any

specific acts.

In part V, page 17 of the Memorandum of Decision (at

tached appendix, p. A-23), the District Court stated:

“ There was no evidence that any of the added de

fendant school corporations have committed acts of

de jure segregation directed against Negro students

living within their respective borders.”

yet the Court ordered that each of the added defendant

school corporations was directed to accept Negro transfer

students from the Indianapolis Public Schools at the rate

of 5% of their 1972-73 enrollment, except for Washington

Township and Pike Township where the rates were 1%

and 2% respectively.

Also, the Indianapolis Public School system was ordered

to rearrange the enrollment patterns of its elementary

schools so that each school, at the beginning of the 1973-

74 school year, had a minimum Negro enrollment of 15%.

Four (4) separate motions for stay of the order of July

20, 1973 were filed by the defendants and added defendants

before August 6, 1973, and on August 8, 1973, in open

court, the District Court orally stayed said order as it per

tained to the transfer of IPS students to the added defend

ants, but did not stay that part of the Order that pertained

to the Indianapolis Public Schools.

Notices of appeal were filled by the original defendants

and all added defendants by August 16, 1973. However,

on September 4, 1973, the Court granted intervening plain

tiffs’ motion for leave to interplead a second class of added

defendants, and another Amended Complaint was filed on

that date. The United States of America, the Original plain

tiff, filed its notice of appeal on September 18, 1973.

Briefs were filed in the Seventh Circuit by all appellants

on or before December 10, 1973. However, on December 6,

1973, the District Court issued its “ Supplemental Memo

randum of Decision” (hereafter Supplemental Decision)

which vacated the orders in the July 20, 1973, Decision that

had been stayed on August 8, 1973, regarding the transfer

of pupils from IPS to the added defendant School Districts.

See attached appendix, p. A-39. In that Supplemental Deci

sion the District Court gave the Indiana General Assembly

until the end of the 1974 legislative session or February

15, 1974, whichever comes first, to enact a metropolitan

school desegregation plan. If the General Assembly should

“ default” in its “ duty” to find a permanent solution to

the desegregation of IPS into twenty-three (23) separate

and distinct school districts found not to be guilty of any

de jure segregation, then the District Court will devise its

own plan.

Thus, even though neither the State of Indiana nor the

General Assembly were parties to the foregoing litigation,

17

it is certain that if the General Assembly does not enact

some type of metropolitan plan which is suitable to the Dis

trict Court the Court will draft such a plan. Therefore, the

Indianapolis metropolitan area faces a major school re

organization which could include eight (8) counties and

from twenty-four (24) to forty-four (44) separate and in

dependent school districts with a total pupil population of

from approximately 205,000 students to 260,000 students,

all of which would be directed by a district court judge

whom the State of Indiana would assert is totally without

power to so act.

There was no contention made that the Indianapolis

Public School system can not now effect a desegregation

plan, or that it is not prepared to do so. The Indianapolis

federal district court, like Detroit, has involved the addi

tional school system because it wants a plan which once

implemented will “ work forever” and which will place

black students in a perpetual minority in all schools in the

Indianapolis metropolitan area.

The District Court further demands this in face of the

fact that the IPS system has about 9 percent of the entire

assessed school valuation for the State of Indiana, and that

it has the financial capacity to raise over $100,000,000 for

the construction of new schools, should it decide to do so.

(See attached appendix following p. A-63).

In short, that the IPS system can now desegregate is

not contestable. The concern of the District Court was that

it might not work forever, and it has entered orders against

the additional school defendants after finding that they

did not commit acts of discrimination and were not ille

gally segregated or de jure segregated school systems.

18

C.

Indiana and Michigan Compared

First, concerning the additional school defendants in

these cases, in Michigan there was no evidence and no find

ings against those school systems. In Indiana the District

Court found that they were not de jure segregated sys

tems. In each case the district court has either entered

orders against them, or will do so, regardless of the ab

sence of evidence or the finding of no discrimination by

them.

Secondly, concerning the state school boards and offi

cials, in Indiana the only connection with the “ State”

(which was never a party to the action) was the site ap

proval given to three high schools in the IPS system. In

Michigan, the principal connection was the enactment of

a statute affecting the Detroit Public School system. In

neither case was there any showing that the “ state acts”

had any causal connection to the racial composition of

either school system, and there was of course no showing,

nor could there have been, that in either Michigan or Indi

ana the “ state acts” had any effect in any other school

district in either the Detroit or Indianapolis area. In

neither case is the argument made that the existence of the

school district themselves caused racial discrimination and

segregation, or that they were created for those purposes

or to impede the removal of the vestiges of a dual system.

The Sixth Circuit held however, that the absence of a dual

system among school districts was insignificant, because

it “ follows logically that existing boundary lines cannot

be frozen for an unconstitutional purposes” 484 F.2d at

250.

The above-quoted statement is of course true. But either

the Sixth Circuit’s statement has no relevance to this case,

or, if it remains a controlling holding, the fact that the

added school defendants in Detroit were not fonnd to be

dlial school systems is no longer significant to this type of

litigation. If this is to become the law from this Court,

then federal equity power in this type of litigation is no

longer founded upon the duty to desegregate, after a find

ing of illegal state compelled segregation.

D.

The Metropolitan Remedy

The essential fact in the Indiana case is not that the

Indianapolis Public School system was illegally segre

gated, or that it can now be desegregated. It is that the

additional school district defendants were not segregated

and the district court entered a finding to that effect. After

that finding it entered orders against them.

The process by which this was accomplished was the

same process used by the district court in Detroit. It is as

follows: (1) education is a state public function because it

is developed pursuant to state law from the state govern

mental power; (2) acts by state officials are public acts;

(3) acts by local school boards are imputable to state edu

cation officials, whenever they occur with or without

knowledge on the part of the state education official; (4)

when the imputed act has occurred, or when a de jure act

is taken by the state official or legislature, then the dis

trict court has judicial power over the public function of

education in as many school systems as are “ conveniently”

reached by a school bus; and (5) that that power will be

asserted unless the state acts in a way consistent with the

district court’s desire.

The district court in Detroit would effect a metropolitan

remedy [“ provided, however, that existing administra-

20

tive, financial, contractual, property and governance ar

rangement shall be examined, and recommendations for

their temporary and permanent retention or modification

shall be made * * *” 345 F.Supp. 914, at 919, a ff ’d but

partly vacated, 484 F.2d at page 252 (1973)], and the dis

trict court in Indianapolis would effect the same type of

remedy, (see attached appendix, p. A-61).

This will occur not because of segregation in the school

systems in those two cities, nor because among those sys

tems segregation existed, nor because they were created to

effect racial discrimination. It will occur, in fact, because

those district courts believe it is desirable to submerge

black students forever in a minority status in the public

school systems in the respective areas. See attached ap

pendix, pp. A-12 and A-58.

The White-Majority Thesis has been rejected in Brunson

v. Board of Trustees, 429 F.2d 820, 826 (4th Cir. 1970)

(Judge Sobeloff, concurring) :

“ The invidious nature of the Pettigrew thesis, ad

vanced by the dissent in the present case, thus emerges.

Its central proposition is that the value of a school de

pends on the characteristics of a majority of its stu

dents and superiority is related to whiteness, inferior

ity to blackness. Although the theory is couched in

terms of ‘ socio-economic class’ and the necessity for

the creation of a ‘middle-class milieu,’ nevertheless,

at bottom it rests on the generalization that, educa

tionally speaking, white pupils are somehow better or

more desirable than black pupils.”

Thus, the essence of this case, as well as the case in Indi

anapolis, is whether the federal judiciary shall remove local

control of school systems and school districts, even in the

absence of racial discrimination in those schools, because

there is a heavy black enrollment (40% black in Indian-

apolis and 64% black in Detroit) in the city school system

involved in the litigation which itself may or may not be

a segregated system. Compare, Northcross v. Bd. of Ed.

Memphis, Term., No. 73-1954; No. 73-1667 (6th Cir., Dec. 4,

1973).

Plaintiffs in such cases will ask for the consolidation

and the redistricting of schools, and for the busing of stu

dents to and from systems which were not segregated. That

will mean disregarding governmental boundary lines, not

only for pupil placement but for teacher assignment, for

building construction and the taxable base which supports

that construction, and for both administrative and voter

control also.

These cases would instigate a more major political and

social upheaval than the progression either from the “ sepa

rate but equal” doctrine of Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S.

537 (1896), to the “ separate is inherently unequal” doc

trine of Brown 1, supra, or from “ freedom of choice” of

the post-Brown era to the “ affirmative duty” of Green v.

County School Board of New Kent County, Virginia, 391

U.S. 430 (1968), Swann, supra, and Keyes, supra.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The amicus accepts the statement of the case as set out

by Petitioners on brief to this Court.

21

22

ARGUMENT

I.

A FEDERAL DISTRICT COURT DOES NOT HAVE

THE POWER TO ORDER THE TRANSFER OR

EXCHANGE OF STUDENTS FROM ONE SCHOOL

DISTRICT FOUND TO BE GUILTY OF DE JURE

SEGREGATION ACROSS POLITICAL BOUNDA

RIES TO OTHER SCHOOL DISTRICTS FOUND

NOT TO BE GUILTY OF ANY DE JURE

VIOLATIONS

In Swann, supra, this Court clearly established the power

of a district court in a school desegregation case, stating

at page 16:

“ In seeking to define even in broad and general

terms how far this remedial power extends it is im

portant to remember that judicial powers may be

exercised only on the basis of a constitutional violation.

Remedial judicial authority does not put judges auto

matically in the shoes of school authorities whose

powers are plenary. Judicial authority enters only when

local authority defaults.

. . . As with any equity case, the nature of the viola

tion determines the scope of the remedy. . . .”

(Emphasis supplied.)

Thus, in this case this Court must examine what the

Sixth Circuit apparently determined was a constitutional

violation, and in so doing this Court will find that there were

no findings entered against the out-of-city schools. Those

schools were simply brought in to effect a remedy, i.e., the

Sixth Circuit says that the Detroit Schools cannot be de

segregated within their own boundaries, therefore the

23

boundaries have to be extended to bring in other school

districts. And the fact that those added districts had not

committed any constitutional violations was immaterial to

the Sixth Circuit.

A similar situation exists in Indianapolis, except that the

District Court there went so far as to enter a finding that

none of the added defendant school districts was guilty of

any discrimination (attached appendix p. A-23). But after

making that finding that District Court proceeded to use

those districts to effect its remedy to desegregate IPS.

In Bradley v. School Board of City of Richmond,

Virginia, supra, the Fourth Circuit said at page 1069:

“ Because we are unable to discern any constitu

tional violation in the establishment and maintenance

of these three school districts, nor any unconstitutional

consequence of such maintenance, we hold that it was

not within the district judge’s authority to order the

consolidation of these three separate political sub

divisions of the Commonwealth of Virginia. . . . ”

See also Spencer v. Kugler, supra.

Therefore, it is quite clear that the Sixth Circuit is

attempting to impose a remedy upon school districts that

are not guilty of any constitutional violations, and that

attempt must be reversed by this Court pursuant to

Swann, supra, Bradley v. School Board of City of Rich

mond, Virginia, supra, and Spencer v. Kugler, supra.

24

II.

THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT DOES NOT

REQUIRE A STATE TO REMOVE BLACK CHIL

DREN FROM SCHOOLS IN WHICH THEY CON

STITUTE A MAJORITY OF THE STUDENTS

ENROLLED, OR A SUBSTANTIAL MINORITY,

IN ORDER TO MIX THEM WITH WHITE CHIL

DREN IN OTHER SCHOOL DISTRICTS, SO

THAT THE BLACK CHILDREN WILL ALWAYS

BE IN A RACIAL MINORITY.

The gist of the constitutional understanding which the

District Court had in Detroit was clearly stated by that

court:

“ In reality, our courts are called upon, in these cases,

to attain a social goal, through the educational system,

by using law as a lever. ’ ’ 484 F.2d at 261; Cert. App.

41a.

“ To use the vernacular, ‘Right on!’ but steady as we

go.” Cert. App. 41a.

That certainly is not an accurate statement of the law in

school desegregation cases as established by this Court.

A.

THE CONSTITUTIONAL DEFINITION

The cases governing the district court here are, of course,

found from Brown 1, supra to Keyes, supra:

The constant theme and thrust of every holding from

Brown I to date is that state-enforced separation of the

races in public schools is discrimination that violated

the Equal Protection Clause. The remedy commanded

was to dismantle dual school systems.

25

“ We are concerned in these cases with the elimina

tion of the discrimination inherent in the dual school

systems . . . The target of the cases from Brown I to

the present was the dual school system. The elimina

tion of racial discrimination in public schools is a large

task and one that should not he retarded by efforts to

achieve broader purposes lying beyond the jurisdiction

of school authorities. One vehicle can carry only a lim

ited amount of baggage. (Emphasis supplied). Swann,

402 U.S. at 22.

In discussing the extent of the remedy, the Supreme Court

in Swann made the following observations at page 24:

. . . If we were to read the holding of the district court

to require, as a matter of substantive constitutional

law, any particular degree of racial balance or mixing,

that approach would be disapproved and we would be

obliged to reverse. The constitutional command to de

segregate schools does not mean that every community

must always reflect the racial composition of the school

system as a whole.’ (Emphasis supplied.)

And at pages 31 and 32:

At some point, these school authorities and others

like them should have achieved full compliance with

this Court’s decision in Brown I. The systems will then

be ‘ unitary’ in the sense required by our decisions in

Green and Alexander.

It does not follow that the communities served by

such systems will remain demographically stable, for

in a growing, mobile society, few will do so. Neither

school authorities nor district courts are constitution

ally required to make year-by-year adjustments of the

racial composition of student bodies * * * (Emphasis

supplied.)

In this case there was no finding that the State attempted

to fix or alter demographic patterns so as to affect the

26

racial composition of the schools in the Detroit area or in

Michigan in general. Likewise, there was no finding that the

school corporations were established for that purpose, or

that they effected that purpose and were intended to do so.

Compare Keyes v. School District No. 1, 93 S.Ct. 2686, at

2696 (1973).

In short, in Brown 1, supra, this Court struck down a gov

ernmental policy of racial segregation which was effected

in the public school system. The Court did not then, and

has not since that time used the Fourteenth Amendment

to develop educational policy.

Brown was a case which struck at a government devel

oped racial-social policy of segregation and discrimination

in the public schools. Such governmental policies meant in

herent inequality which was developed and effectuated, in

part, by use of public school system. Thus, this Court said,

“ The target of the cases from Brown I to the present was

the dual school system.” Swann, supra at 22.

But the use of the public school system to develop and

promote a governmental policy of racial segregation was

only a part of the systematic program. It occurred and was

struck down in public parks, Muir v. Louisville Park The

atrical Assn., 347 U.S. 971 (1954), in and on public beaches

and bathhouses, Mayor and City Council of Baltimore City

v. Daivson, 350 U.S. 877 (1955), municipal golf courses,

Holmes v. City of Atlanta, 350 U.S. 879 (1955), and on

municipal buses, Gayle v. Browder, 352 U.S. 903 (1956),

all on the authority and the concept of the Brown decision.

The cases which hold that for a Brown violation there

must be a state act in creating racial segregation or illegal

separation, rather than adventitious development or demo

graphic qua social alterations, are simply legion. Among

them are: Keyes v School District No. 1, supra; Spencer v.

27

Kugler, supra; Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, Vir

ginia, supra; Springfield School Committee v. Barksdale,

348 F.2d 261, 264, (1st Cir. 1965); Offerman v. Nitkowski,

378 F.2d 22 (2nd Cir. 1967); Sealy v. Dept, of Public In

struction, 252 F.2d 898 (3rd Cir. 1957), certiorari denied,

356 U.S. 975 (1958); Deal v. Board of Education, 369 F.2d

55 (6th Cir. 1965); and Downs v. Board of Education, 366

F.2d 988 (10th Cir. 1964), certiorari denied, 380 U.S. 914.

B.

A SCHOOL BOARD’S DUTY

The duty of school officials to date has been to remedy

segregation which has occurred within a single district, or

to cross school district line for purposes of desegregation

when districts were established as a part of a dual school

system; Haney v. County Board of Education of Sevier

County. 410 F.2d 920 (8th Cir. 1969); or were set up to im

pede the dismantling of a dual school system; Wright v.

Council of Emporia, 407 U.S. 451 (1972); or where the state

actively imposed its power to prevent the dismantling of a

dual school system within a single district; Lee v. Macon

County Board of Education, 448 F.2d 746 (5th Cir. 1971);

Cf. Bradley v. School Board (Richmond), 462 F.2d 1058

(4th Cir. 1972), a ff’d per curiam by an equally divided

court, 36 L.Ed.2d 771, 93 Sup. Ct. 1952 (1973).

Once school officials have taken the necessary action

within their respective school corporations to insure that

schools under their control are not racially identified either

as “ white” or “ black” as compared to each other on ac

count of discriminatory acts by school or state officials their

constitutional duty has been considered to be at an end.

Swann, supra, 402 U.S. 16, 28, 31-2. To combine city and

county schools “ by judicial fiat” has been expressly de

28

nied as a matter for “ legislative, executive or political reso

lution.” Mapp v. Bd. of Ed. of Chattanooga, (E. D. Tenn.

1971), 329 F. Supp. 1374, 1378, a ff ’d per curiam (6th

Cir. 1973) 477 F.2d 851. Compare, Higgins v. Bd. of Ed.

City of Grand Raids, Mich., No. CA 6386 (W.D.Mich.

July 18, 1973).

C .

THIS CASE AND THE NEW CONSTITUTION

FOE 'METROPOLITAN AMERICA

The new duty imposed by the Court in the instant case

is one that would require the mixing of races wherever

found within a metropolitan area so that only “ white-

majority” districts would be maintained. This cannot be

done by a single district in all cases, and where it cannot,

the Court would require a substantial redefinition of the

constitutional duty owed under the Fourteenth Amend

ment to each minority child in a city. To date, the school

function and the overall supervision of schools and their

basic governmental structure have been determined by the

State; their boundaries have been set with reference to

historical entities; and the detailed operation and the

myriad of factors involving virtually all of the items de

scribed in Keyes, supra, are delegated to school districts

with plenary corporate powers. This is vividly described

in San Antonio Independent School Dist. v. Rodriguez, 411

U.S. 1, 36 L.Ed. 2d 16 (1973), where state educational fi

nancing schemes faced a comparable challenge in the state

relationship to its governmental units. Any such attempt

to reorder the structure of school government has hereto

fore been “ reserved for the legislative processes of the

various States.” Rodriguez, supra, 36 L.Ed. 2d 16 at 57.

29

The imposition of such a new duty will require courts

not only to balance integrative necessities against travel

time and its effect on the educational system, but also with

prescribing necessary black-white ratios and enrollment;

geographic size and school board organization; and the

distribution of assets, debt, teachers, and tax base for each

unit in each school district in the entire metropolitan area.

The Sixth Circuit’s point of view is a call for busing and

total school reorganization for racial balance, and is clearly

contrary to the cases where majority-black schools and

majority-black school systems have been approved. See

Wright v. Emporia, supra (66% black); Bradley v. School

Board of Richmond, Virginia, supra (69% black); North-

cross v. Board of Education of Memphis City Schools,

397 U.S, 232 (1970) (53.6% black) (341 F. Supp. at p. 586);

Raney v. Board of Education of Gould School District, 391

U.S. 443 (1968) (60% black); U.S. v. Scotland Neck City

Board of Education, 407 U.S. 484 (1972) (78% black);

Brunson v. Board of Trustees of School District No. 1 of

Clarendon County, supra (90% black). In addition, busing

solely for purposes of racial balance is proscribed by the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000c-6(a).

Further, the trial court and the Sixth Circuit in the

majority opinion erred by basing the remedy on the over

all right of the State to control the methods of education.

The real issue is not whether education is a “ state power”

or “ local power” but whether a Federal court should

respect the right of the states to structure their internal

government under the Tenth Amendment to the United

States Constitution.

It is submitted that this structure of State government

should not be destroyed where the concentration of blacks

within the inner-city was caused by a variety of factors in

cluding in-migration, birthrates, income factors and per-

30

sonal choice. Where such concentration of blacks was not

caused by State action, the internal structure of the State

has been respected. See, e.g., Spencer v. Kugler, supra.

CONCLUSION

A decision to mandate a metropolitan “ solution” is bas

ically a political and social decision—a major untried

change in ordering human affairs, at least as far as the

Federal Judiciary is concerned.

However, the nation as a whole has chosen to administer

its schools in relatively small governmental units as is

evidenced by the following chart showing the number and

percent of school districts by size in the United States:

Pupils

Number of

Districts

Percentage

of Districts

25,000 and over 180 1.001%

10,000 to 24,999 538 2.992%

5,000 to 9,999 1,096 6.095%

2,500 to 4,999 2,026 11.268%

300 to 2,499 7,911 43.998%

Under 300 6,229 34.644%

(Source: Digest of Educational Statistics,

1971 Ed. United States Dept, of

H.E.W.)

One can paraphrase Rodriguez: the concept of this case,

after it has mutated in the Court of Appeals, is a chal

lenge to the manner in which states choose to educate chil

dren, an area in which the federal and state courts lack

expertise and familiarity, where educators are divided on

many of the problems of reorganization and where it would

be difficult to imagine a rule having a greater potential

impact on the federal system.

31

Finally, it must be said that these opinions below do not

advance the cause of human dignity, human freedom, or

human choice. They greatly retard those critical elements

of a free society and this appears to have occurred be

cause the courts have confused the elements of a class

action with constitutional rights under the Fourteenth

Amendment. The dissenting opinion in the Sixth Circuit

captured the essence of the matter, saying:

“ The metropolitan busing remedy order by the

Court is, however, unconstitutional on a more funda

mental level. It invalidly assumes that the equal pro

tection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment protects

groups and not individuals. The entire thrust of the

District Court’s order is that the rights of blacks as a

group must be redressed and that, in the process, the

rights of individual black children (and non-black chil

dren) may be disregarded.” 484 F.2d at 265. (Em

phasis supplied.)

WHEREFORE, for all the above and foregoing, the

State of Indiana, amicus curiae herein, respectfully urges

this Court reverse the decision of the Sixth Circuit.

Respectfully submitted,

T heodore L. S endak

Attorney General of Indiana

D onald P. B ogard

Deputy Attorney General

W lliam F . H arvey

Special Counsel for the

Attorney General

Office of Indiana Attorney General

219 State House

Indianapolis, Indiana 46204

Telephone: (317) 633-4076

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1973

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al., )

. . . )

Petitioners,)

)

vs. ) No. 73-434

)

RONALD G. BRADLEY, et al., )

)

Respondents.)

)

ALLEN PARK PUBLIC SCHOOLS, et al., )

)

Petitioners,)

)

vs. ) No. 73-435

)

RONALD G. BRADLEY, et al., )

)

Respondents.)

)

THE GROSSE POINTE PUBLIC SCHOOL)

SYSTEM, et al., )

)

Petitioners,)

)

vs. ) No. 73-436

)

RONALD G. BRADLEY, et al., )

)

Respondents.)

32

33

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

The undersigned hereby certifies that on the 28th day

of December, 1973, three (3) copies of the BRIEF ON

THE MERITS IN SUPPORT OP PETITIONERS SUB

MITTED AMICUS CURIAE BY THE STATE OP

INDIANA were deposited in the United States Mail, first

class postage prepaid, addressed to all counsel of record,

except that service of the counsel of record residing in

excess of five hundred (500) miles from Indianapolis,

Indiana, has been made by

Counsel of Record:

Jack Greenburg

Norman Chachkin

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10015

Louis R. Lucas

William E. Caldwell

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

Elliott Hall

950 Guardian Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

Douglas H. West

3700 Penobscot Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

Frank T. Kelley

Attorney General of Michigan

Robert A. Derengoski

Solicitor General

720 Law Building

525 W. Ottawa Street

Lansing, Michigan 48913

air mail, postage prepaid.

Paul R. Dimond

210 E. Huron Street

Ann Arbor, Michigan 48108

Nathaniel A. Jones

1790 Broadway

New York, New York 10019

J. Harold Flannery

Robert Pressman

Larsen Hall, Appian Way

Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138

William M. Saxton

John B. Weaver

Robert M. Vercruysse

Xhafer Orhan

1881 First National Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

THEODORE L. SENDAK

Attorney General of Indiana

A P P E N D IX

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Memorandum of Decision of July 20, 1973—U.S. Dis

trict Court for the Southern District of Indiana . . . A -l

Supplemental Memorandum of Decision of December,

6, 1973—U. S. District Court for the Southern Dis

trict of Indiana ............................................ A-3

Indiana SMSA (16-3) ................................................... A-64

Chicago Urbanized Area (16-44) ...................................A-65

South Bend Urbanized Area (16-48) ............................A-66

Pupil Statistical Data for Eight Counties (Ex. H) . . . A-67

Carmel-Clay Exhibit DD—U.S.A. & Buckley et al. v.

Board of School Commissioners et al., IP 68-C-225.. A-68

A-i

. . . .

............................................. ..

.................................................... ... ; 1

i » ............ ...

I

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF INDIANA

INDIANAPOLIS DIVISION

F I L E D

U.S. District Court

Indianapolis Division

July 20 8 :10 AM ’73

Southern District

of Indiana

Arthur J. Beck

Clerk

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, )

)

Plaintiff',)

)

DONNY BRURELL BUCKLEY, )

ALYCIA MARQUESE BUCKLEY, By)

their parent and next friend, Ruby L.)

Buckley, on behalf of themselves and)

all Negro school age children residing)

in the area served by original defend-)

ants herein, )

)

In tervening Plaintiffs,)

)

vs. ) NO. IP 68-C-225

j

THE BOARD OF SCHOOL COMMIS-)

SIONERS OF THE CITY OF IN-)

DIANAPOLIS, INDIANA; )

KARL R. KALP, as Superintendent of)

Schools; )

ERLE A. KIGHTLINGER, as President)

of The Board of School Commission-)

ers; )

A-l

A-2

JESSIE JACOBS, )

CARL J. MEYER, )

PAUL E. LEWIS, )

LESTER E. NEAL, )

CONSTANCE R. VALDEZ, )

W. FRED RATCLIFF, Members of The)

Board of School Commissioners of the)

City of Indianapolis, )

Defendants,)

)

OTIS R. BOWEN, as Governor of the) „

State of Indiana; )

THEODORE SENDAK, as Attorney)

General of the State of Indiana; )

HAROLD H. NEGLEY, as Superintend-)

ent of Public Instruction of the State)

of Indiana; )

)

THE METROPOLITAN SCHOOL )

DISTRICT OF DECATUR TOWN-)

SHIP, MARION COUNTY, INDIANA;)

THE FRANKLIN TOWNSHIP COM-)

MUNITY SCHOOL CORPORATION,)

MARION COUNTY, INDIANA; )

)

THE METROPOLITAN SCHOOL )

DISTRICT OF LAWRENCE TOWN-)

SHIP, MARION COUNTY, INDIANA;)

)

THE METROPOLITAN SCHOOL )

DISTRICT OF PERRY TOWNSHIP,)

MARION COUNTY, INDIANA; )

)

THE METROPOLITAN SCHOOL )

DISTRICT OF PIKE TOWNSHIP,)

MARION COUNTY, INDIANA; )

A-3

THE METROPOLITAN SCHOOL )

DISTRICT OF WARREN TOWN- )

SHIP, MARION COUNTY, INDIANA;)

)

THE METROPOLITAN SCHOOL )

DISTRICT OF WASHINGTON TOWN-)

SHIP, MARION COUNTY, INDIANA;)

)

THE METROPOLITAN SCHOOL )

DISTRICT OF WAYNE TOWNSHIP,)

MARION COUNTY, INDIANA; )

)

SCHOOL CITY OF BEECH GROVE,)

MARION COUNTY, INDIANA; )

)

SCHOOL TOWN OF SPEEDWAY,)

MARION COUNTY, INDIANA; )

)

THE GREENWOOD COMMUNITY)

SCHOOL CORPORATION, JOHNSON)

COUNTY, INDIANA; )

)

CARMEL-CLAY SCHOOLS, HAMIL-)

TON COUNTY, INDIANA; )

)

MT. VERNON COMMUNITY SCHOOL)

CORPORATION, HANCOCK COUNTY,)

INDIANA; )

GREENFIELD COMMUNITY SCHOOL)

CORPORATION, HANCOCK COUNTY,)

INDIANA; )

)

MOORESVILLE CONSOLIDATED )

SCHOOL CORPORATION, MORGAN)

COUNTY, INDIANA; )

)

PLAINFIELD COMMUNITY SCHOOL)

CORPORATION, HENDRICKS )

COUNTY, INDIANA; )

A-4

AVON COMMUNITY SCHOOL COB-)

PORATION, HENDRICKS COUNTY,)

INDIANA; )

)

BROWNSBURG COMMUNITY )

SCHOOL CORPORATION, HEN- )

DRICKS COUNTY, INDIANA; )

)

EAGLE-UNION COMMUNITY )

SCHOOL CORPORATION, BOONE )

COUNTY, INDIANA; )

) -

THE INDIANA STATE BOARD OF)

EDUCATION, a public corporate body;)

)

Added Defendants,)

)

CITIZENS FOR QUALITY SCHOOLS,)

INC., )

)

Intervening Defendant,)

)

COALITION FOR INTEGRATED )

EDUCATION, )

)

Amicus Curiae.)

MEMORANDUM OF DECISION

I. Introduction

This is a school desegregation action originally brought

by the United States on May 31, 1968, pursuant to Section

407(a) and (b) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000c—6(a) and (b) against The Board of School Com

missioners of Indianapolis, Indiana (hereinafter IPS), the

members of the Board, and its appointed Superintendent of

Schools.

A-5

On August 18, 1971, this Court found and concluded that

IPS was guilty of unlawfully segregating the public schools

within its boundaries. That decision was unanimously

affirmed by the United States Court of Appeals for the

Seventh Circuit and review was denied by the Supreme

Court of the United States, without dissent. United States

v. Board of Sch. Com’rs, Indianapolis, Ind., 332 P.Supp.

655, a ff ’d 474 F.2d 81, cert.den. ------U.S. ------, 41 L.W.

3673 (June 25,1973). Such issue is res judicata.

In contemplating a remedy to vindicate the rights of

Negro school children, this Court concluded that it could

have ordered a massive “ fruit basket” scrambling of stu

dents within IPS to achieve exact racial balancing. But

the Court also concluded that in the long run, given the

steadily rising percentage of Negro pupils within IPS, the

racial composition of IPS would become nearly all Negro

because of an acceleration in the departure of white fami

lies with children from IPS. In this connection the Court

discussed the “ tipping-point” factor—the point at which

white exodus from a school unit is accelerated by increase

of Negro students beyond a certain variable percent, and

noted that the tipping-point/resegregation problem would

become insignificant if the boundaries of IPS were enlarged

to include all of Marion County and a portion of its con

tiguous metropolitan region. The Court does not consider

its conclusions in this area as res judicata.

In order to provide an appropriate adverse setting for

further consideration of the legal and practical appropri

ateness of a metropolitan plan, the Court ordered the plain

tiff United States to secure the joinder of necessary parties

and seek further relief to determine the answers to certain

questions posed by the Court.

On September 7, 1971, the United States (hereinafter the

Government), pursuant to such order, moved to add as

A-6

parties defendant all school corporations in Marion

County, other than IPS. The motion was granted. How

ever, the Government failed to assert any claims or seek

any relief against such added defendants. A few days later

the Buckley plaintiffs filed their petition to intervene in

this action in their own right and as respresentatives of a

class consisting of Negro school age children residing in

Marion County, Indiana, who are required to attend segre

gated schools operated by IPS. The petitioners alleged that

their interests and those of the class they represented were

not being adequately protected by the original plaintiff,

the United States, because the Government had failed to

seek relief against the added school defendants. The Court

granted the petition to intervene on September 14, 1971.

The Buckley intervening plaintiffs (hereinafter plain

tiffs) eventually joined as added defendants Edgar D.

Whitcomb (since succeeded by Otis R. Bowen), as Gov

ernor of the State of Indiana; Theodore Sendak, as

Attorney General of Indiana; John J. Loughlin (since suc

ceeded by Harold H. Negley), as Superintendent of Public

Instruction of the State of Indiana; The Indiana State

Board of Education, and nineteen school corporations

within and without Marion County, Indiana (including the

ten in-county corporations joined by the Government), as

follows:

Marion Gounty

The Metropolitan School District of Decatur Township

(hereinafter Decatur)

The Franklin Township Community School Corporation

(hereinafter Franklin)

The Metropolitan School District of Lawrence Township

(hereinafter Lawrence)

A-7

The Metropolitan School District of Pike Township

(hereinafter Pike)

The Metropolitan School District of Warren Township

(hereinafter Warren)

The Metropolitan School District of Washington Town

ship (hereinafter Washington)

The Metropolitan School District of Wayne Township

(hereinafter Wayne)

School City of Beech Grove (hereinafter Beech Grove)

School Town of Speedway (hereinafter Speedway)

Boone County

Eagle-Union Community School Corporation (herein

after Eagle)

Franklin County

Greenwood Community School Corporation (hereinafter

Greenwood)

Hamilton County

Carmel-Clay Schools (hereinafter Carmel)

Hancock County

Greenfield Community School Corporation (hereinafter

Greenfield)

Mt. Vernon Community School Corporation (hereinafter

Mt. Vernon)

Hendricks County

Avon Community School Corporation (hereinafter Avon)

Brownsburg Community School Corporation (here

inafter Brownsburg)

A-8

Plainfield Community School Corporation (hereinafter

Plainfield)

Morgan County

Mooresville Consolidated School Corporation (herein

after Mooresville)

The geographical areas served by IPS and added defend

ants, with the exception of Greenfield, and Union Township

of Eagle-Union, are reflected on Figure 1. Also represented

thereon, for reasons which will hereafter appear, are terri

tories or parts of territories served by certain other school

corporations bordering on Marion County, namely, Clark-

Pleasant Community School Corporation (Clark) and Cen

ter Grove Community School Corporation (Grove) of John

son County; Delaware and Pall Creek Townships, a part

of Hamilton Southeastern School Corporation of Hamilton

County; Sugar Creek Township, a part of Southern Han

cock County Community Schools (Hancock) of Hancock

County; and Moral Township, a part of Northwestern

Consolidated School Corporation of Shelby County (North

western) of Shelby County.

The intervening defendant Citizens of Indianapolis for

Quality Schools, Inc., is a not-for-profit corporation whose

members are parents of children in IPS. Its initial attempt

to intervene in this action, in opposition to the original

complaint of the Government, was denied by this Court,

although the Court permitted it to attend the original trial,

present argument, and file a brief amicus curiae. The ruling

was appealed and affirmed. United States v. Board of Sch.

Com’rs, Indianapolis, Ind., 466 F.2d 573 (7 Cir. 1972). Sub

sequently, however, intervention was permitted and inter

vening defendant participated fully in the most recent

trial.

A-9

Coalition for Integrated Education is an unincorporated

association of individuals favoring a metropolitan plan of

school desegregation, which filed a petition for leave to

appear amicus curiae for the purpose of presenting a