Company to Pay for Discrimination

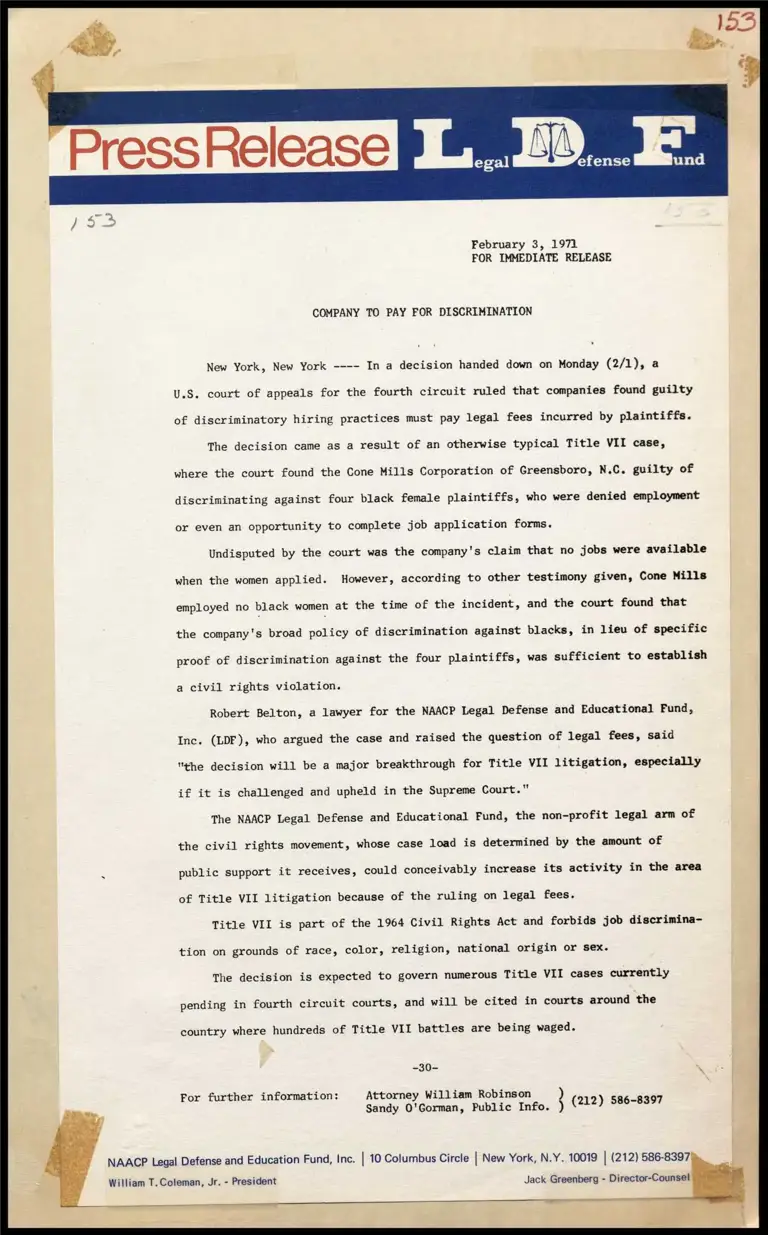

Press Release

February 3, 1971

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Volume 6. Company to Pay for Discrimination, 1971. 47369a64-ba92-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1f41d055-8d76-4e47-8081-247d91438ff1/company-to-pay-for-discrimination. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

February 3, 1971

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

COMPANY TO PAY FOR DISCRIMINATION

New York, New York ---- In a decision handed down on Monday (2/1), a

U.S. court of appeals for the fourth circuit ruled that companies found guilty

of discriminatory hiring practices must pay legal fees incurred by plaintiffs.

The decision came as a result of an otherwise typical Title VII case,

where the court found the Cone Mills Corporation of Greensboro, N.C. guilty of

discriminating against four black female plaintiffs, who were denied employment

or even an opportunity to complete job application forms.

Undisputed by the court was the company's claim that no jobs were available

when the women applied. However, according to other testimony given, Cone Mills

employed no black women at the time of the incident, and the court found that

the company's broad policy of discrimination against blacks, in lieu of specific

proof of discrimination against the four plaintiffs, was sufficient to establish

a civil rights violation.

Robert Belton, a lawyer for the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc. (LDF), who argued the case and raised the question of legal fees, said

"the decision will be a major breakthrough for Title VII litigation, especially

if it is challenged and upheld in the Supreme Court."

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, the non-profit legal arm of

the civil rights movement, whose case load is determined by the amount of

S public support it receives, could conceivably increase its activity in the area

of Title VII litigation because of the ruling on legal fees.

Title VIL is part of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and forbids job discrimina-

tion on grounds of race, color, religion, national origin or sex.

The decision is expected to govern numerous Title VII cases currently

pending in fourth circuit courts, and will be cited in courts around the

country where hundreds of Title VII battles are being waged.

-30- ;

For further information: Attorney William Robinson

Sandy O'Gorman, Public Info. } (212) 586-8397

NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, Inc. | 10 Columbus Circle | New York, N.Y. 10019 | (212) 586-8397:

William T. Coleman, Jr. - President Jack Greenberg - Director-Counsel