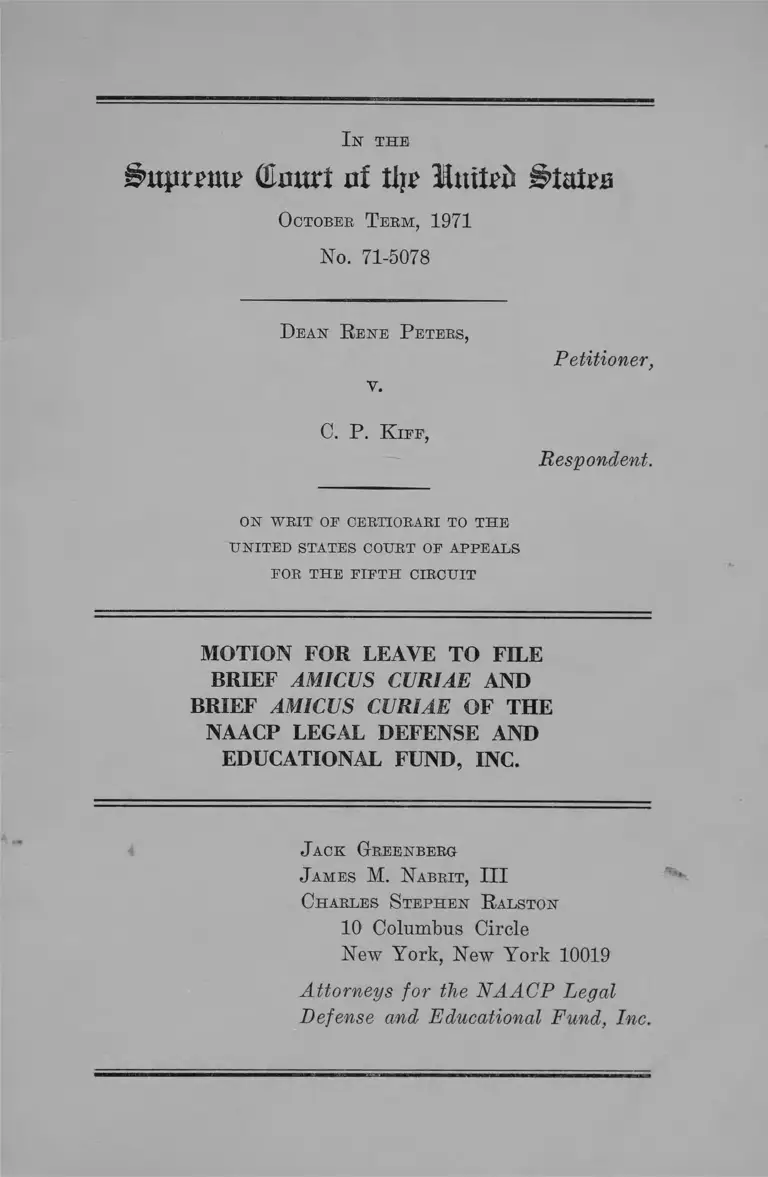

Peters v. Kiff Motion for Leave to File and Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

October 4, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Peters v. Kiff Motion for Leave to File and Brief Amicus Curiae, 1971. 4ee1ee0d-c19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1f51fb44-b6e0-4c67-8924-573d36026f44/peters-v-kiff-motion-for-leave-to-file-and-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

Isr the

(Cmtrt of % laited

Octobee T eem , 1971

No. 71-5078

Dean B ene Peteks,

v.

Petitioner,

C. P. K ief,

Respondent.

ON W BIT OF CEBTIOBAEI TO TH E

UNITED STATES COTJBT OF APPEALS

FOB TH E F IF T H CIBCTTIT

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE AND

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE OF THE

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

Jack Gbeenbebg

James M. Nabbit, III

Charles Stephen Ralston

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for the NAACP Legal

Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

I N D E X

PAGE

Motion for Leave to File Brief Amicus Curiae and

Statement of Interest of Amicus ............................... 1

A rgument ...................................................................................... 1

I. The Due Process Clause Requires That Juries

Reasonably Reflect a Cross-Section of the Com

munity ........................................................................ 2

II. Petitioner Can Challenge the Exclusion of Blacks

Under the Reasoning of Barrows v. Jackson .... 4

III. A Decision That White Defendants May Chal

lenge Discrimination Against Blacks in Jury Se

lection Should Be Made Fully Retroactive ............ 6

Conclusion- .................................................................................... 8

Table op A uthorities

Cases:

Alexander v. Louisiana, 0. T. 1971, No. 70-5026 ....... 5

Allen v. State, 110 Ga. App. 56, 137 S.E.2d 711 (1964).. 3

Avery v. Georgia, 345 U.S. 559 (1953) ........................... 3

Ballard v. United States, 329 U.S. 187 (1946) ........... 2, 3

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249 (1953) ...................... 2, 5

Carter v. Jury Commission of Greene County, 396

U.S. 320 (1970) ............................................................ 2

Fay v. New York, 332 U.S. 261 (1947) ...................... 2

11

PAGE

Hill v. Texas, 316 U.S. 400 (1942) .............................. 4

Maryland v. Madison, 240 Md. 265, 213 A.2d 880

(1965) .............................................................................. 3

Patton v. Mississippi, 332 U.S. 463 (1947) ................ 2

Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S. 128 (1940) ....... ................... 4

Stovall v. Denno, 388 U.S. 293 (1967) .......................... 6

Strander v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1880) ....... 4

Turner v. Fouche, 396 U.S. 346 (1970) .......................... 5

United States ex rel. Goldsby v. Harpole, 263 F.2d

71 (5th Cir. 1959) ....................... 5

Vanleeward v. Rutledge, 369 F.2d 584 (5th Cir. 1966).. 3

Whitus v. Balkcom, 333 F.2d 496 (5th Cir. 1964) ....... 5

Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545 (1967) ...................... 3

Williams v. Florida, 399 U.S. 78 (1970) ...................... 2

Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510 (1968) ............. 6

Statute:

18 U.S.C. §243 ................................................................ 2

I n the

©curt of % Inittfi States

O ctober T erm , 1971

No. 71-5078

Dean Rene Peters,

v.

Petitioner,

C. P. K ife,

Respondent.

o n w r i t o f c e r t i o r a r i t o t h e

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR TH E F IF T H CIRCUIT

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF

AMICUS CURIAE AND STATEMENT OF INTEREST

OF AMICUS

Movant N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc., respectfully moves the Court for permission to file the

attached brief amicus curiae, for the following reasons.

The reasons assigned also disclose the interest of the

amicus.

(1) Counsel for the petitioner has consent to the filing of

a brief amicus curiae by the movant. The present motion

is necessitated because counsel for the respondent has re

fused consent.1 On January 21, 1972, counsel for amicus

mailed to counsel for respondent the final manuscript of

this motion and brief. Therefore, respondent received the

1 The letters of petitioner and respondent granting and refusing

consent are on file with the clerk of this Court.

2

brief in ample time to allow it to respond to the arguments

made therein, if it so desired, in its brief, due February 9,

1972.

(2) Movant N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc., is a non-profit corporation, incorporated under

the laws of the State of New York in 1939. It was formed

to assist Negroes to secure their constitutional rights by

the prosecution of lawsuits. Its charter declares that its

purposes include rendering legal aid gratuitously to Ne

groes suffering injustice by reason of race who are unable,

on account of poverty, to employ legal counsel on their own

behalf. The charter was approved by a New York Court,

authorizing the organization to serve as a legal aid society.

The N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

(LDF), is independent of other organizations and is sup

ported by contributions from the public. For many years

its attorneys have represented parties in this Court and

the lower courts, and it has participated as amicus curiae

in this Court and other courts, in cases involving many

facets of the law.

(3) Over a long period of time, LDF attorneys have

handled, here and in other courts, many cases involving the

unconstitutional esclusion of blacks from jury venires.2

Despite success in these cases, the problem of discrimina

tion in this vital facet of the administration of criminal

justice persists. This experience has led amicus to the con

clusion that its goal, the final eradication of jury discrim

ination, will be substantially advanced by a decision in the

present case that all criminal defendants may challenge

such discrimination. Thus, amicus has an interest in the

2 A7.gr., Patton v. Mississippi, 332 U.S. 463 (1947); Sims v.

Georgia, 389 U.S. 404 (1967) ; Carter v. Jury Commission of

Greene County, 396 U.S. 320 (1970); Turner v. Fouche, 396 U.S.

346 (1970); Alexander v. Louisiana, 0 . T. 1971, No. 70-5026.

3

present case beyond that of the immediate litigants and

therefore presents in the attached brief a broader and al

ternative basis in support of petitioner’s position.

W herefore, movant prays that the attached brief amicus

curiae be permitted to be filed with the Court.

Respectfully submitted,

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

Charles Stephen Ralston

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for the NAACP Legal

Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

I n the

Supreme (Eourt of % United B utts

Octobee T eem , 1971

No. 71-5078

Dean E ene Peters,

v.

Petitioner,

C. P. K ief,

Respondent.

ON W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR TH E F IF T H CIRCUIT

BRIEF OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.,

AS AMICUS CURIAE

ARGUMENT

Because the petition for writ of habeas corpus was de

nied without a hearing, the facts are not in dispute here.

Thus, this case presents squarely the issue of whether a

white defendant may have his indictment quashed or his

conviction reversed on the ground that blacks have been

excluded from juries in violation of the Constitution and

statutes of the United States. AVe urge that two independent

reasons require an affirmative answer: (1) all defendants

have the right under the due process clause to be indicted

and tried by juries that reflect a cross-section of the com

2

munity, i.e., from which no significant group has been ex

cluded; and (2) a defendant has standing to enforce the

rights of the excluded group even if he is not a member

of it under the reasoning of Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S.

249 (1953).

I

The Due Process Clause Requires That Juries Rea

sonably Reflect a Cross-Section of the Community.

This case raises squarely the issue left open by this

Court in Fay v. New York, 332 U.S. 261 (1947), whether the

due process clause alone bars the exclusion of racial groups

from juries so that the constitutional rights of defendants

not members of the excluded group are violated. See, 332

U.S. at 284, n. 27. Amicus urges that the proper view is

that there is an independent due process right to be in

dicted and tried by a jury selected from venires that fairly

represent a cross-section of the entire community. This

requirement arises from “the very idea of a jury” 1 as a

democratic institution1 2 whose purpose is to interpose be

tween the state and the accused a group of laymen who

speak for the community as a whole.3

Here, of course, because of the exclusion of blacks, the

jury did not represent the community as a whole. Indeed,

it was composed in direct and flagrant violation of the Con

stitution and laws of the United States (18 U.S.C. §243) in

spite of decisions of this Court dating back nine decades.

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1880); see, Patton

v. Mississippi, 332 U.S. 463, 465, n. 3 (1947). The particu

1 Carter v. Jury Commission of Greene County, 396 U.S. 320, 330

(1970).

2 Ballard v. United States, 329 U.S. 187, 195 (1946).

3 Williams v. Florida, 399 U.S. 78, 100 (1970).

3

lar device used to exclude blacks in petitioner’s case—segre

gated tax digests—was struck down by this Court the year

after he was convicted in Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545

(1967). Whitus essentially followed, as directly controlling,

the decision in Avery v. Georgia, 345 U.S. 559 (1953), de

cided thirteen years earlier. And see, Vanleeward v. Rut

ledge, 369 F.2d 584 (5th Cir. 1966).

Essentially, the State of Georgia argues that despite the

fact that the juries that indicted and convicted petitioner

were composed in clear violation of federal law, its illegal

acts are insulated from attack here by the fortuity that the

defendant is white.4 We urge that this Court rather adopt

the enlightened view of the Supreme Court of Maryland

and hold that: “ every person accused of crime has the right

to be tried under what has been determined to be the law

of the land,” Maryland v. Madison, 240 Md. 265, 213 A.2d

880, 882 (1965). See also, Allen v. State, 110 Ga. App. 56,

137 S.E.2d 711 (1964).

In Madison, the court held that a believer in God had the

right to be indicted by a jury from which nonbelievers had

not been unconstitutionally excluded; in Allen, the court

held that a white had the right to be tried by a jury from

which blacks had not been similarly excluded. Both deci

sions rested on holdings of this Court interpreting federal

jury statutes and held that their reasoning applied to con

stitutional challenges. As this Court said in Ballard v.

United States, 329 U.S. 187, 195 (1946):

The injury is not limited to the defendant—there is

injury to the jury system, to the law as an institution,

4 In a sense, a white defendant is also denied equal protection by

not being allowed to challenge the exclusion of blacks. That is, his

conviction stands solely because of his race, since if he were black

it would not. See, Maryland v. Madison, 240 Md. 265, 213 A.2d 880,

886 (1965).

4

to the community at large, and to the democratic ideal

reflected in the processes of our courts.

All three cases recognized that it was a denial of due

process in the most fundamental sense to permit a defen

dant to be deprived of liberty by a jury that was convened

in violation of the Constitution. Again, the decisions rest

on the necessity of protecting the jury system as an insti

tution whose purpose is to protect the rights of all persons

charged by the state by putting the ultimate decision as to

their fate in the hands of “a body truly representative of

the community.” A jury otherwise constituted “is at war

with our basic concepts of a democratic society and a rep

resentative government.” Smith v. Texas, 311 U.8. 128,

130 (1940). See also, Hill v. Texas, 316 U.S. 400, 406 (1942).

II

Petitioner Can Challenge the Exclusion of Blacks

Under the Reasoning of Barrows v. Jackson.

In Part I we have argued that a white defendant—indeed

that all defendants—have a personal right under the due

process clause to be indicted and tried by juries selected

in accordance with the Constitution. In addition, we urge

that white defendants should be given standing to enforce

the right of blacks not to be denied equal protection and

thus to effectuate fully the constitutional guarantees that

this Court has so long sought to enforce.

It has been pointed out above that ever since 1880 this

Court, in an undeviating line of decisions, has held that

exclusion of blacks from jury service violates the law.

Sadly, there has been an equally undeviating history of

resistance to and circumvention of the holdings of this

Court. Despite the passage of ninety years since Strauder,

5

this Court is still called on to strike down unconstitutional

jury discrimination. See, Turner v. Fouche, 396 U.S. 346

(1970); Alexander v. Louisiana, O.T. 1971, No. 70-5026.

We suggest that one explanation for this unfortunate

fact is that jury officials have believed that they could, by

and large, get away with unlawful discrimination in most

cases. Only blacks could complain; and most black defen

dants lacked the resources to, and/or lawyers who would,6

raise and prove jury discrimination claims.

If, however, this Court makes it clear that no conviction

of any defendant may stand when blacks have been unlaw

fully excluded from juries, then there may be a different

result. At long last, state officials may decide that they

have more to lose than to gain by continuing jury discrim

ination. The rights of all concerned—black defendants,

white defendants, and black prospective jurors—may finally

become realities.

Thus, this case is closely analogous to Barrows v. Jack-

son, 346 U.S. 249 (1953). There, the Court held that a white

homeowner could raise the constitutional right of blacks not

to be denied equal access to housing by state action as a

defense to an action for damages for violating a racial

restrictive covenant. The specific basis for allowing stand

ing to a white to raise the constitutional rights of blacks

was that it was necessary for the effective enforcement of

those rights. Otherwise, the use of restrictive covenants

would be encouraged (346 U.S. at 254), just as here the

continuation of discriminatory jury selection would be en

couraged. And the refusal to allow petitioner to challenge

the composition of his jury would have the sole effect “ of

giving vitality to” unlawful racial discrimination. See, 346

U.S. at 258.

6 See, United States ex rel. Goldsby v. Harpole, 263 F.2d 71, 82

(5th Cir. 1959); Whitus v. Balkcom, 333 F.2d 496 (5th Cir. 1964).

6

It is true that in Barrows the Court was led to its holding

partly by the fact that since it was unlikely that black

prospective property buyers would come before the courts,

the only way to protect their rights would be to allow white

property owners to defend in damage actions. On the

other hand, the right of blacks to be free of discrimination

in the jury selection process can and has been raised by

blacks themselves. Nevertheless, Barrows should not be

distinguished on that ground. As the experience of ninety

years has shown, the problem of jury discrimination per

sists despite the fact that blacks can and do raise the issue.

For the reasons set out above, we urge that only by allow

ing all defendant to challenge illegal jury selection meth

ods will this blot on the administration of justice be eradi

cated once and for all. Thus, the same concepts of public

policy that were determinative in Barrows should govern

here.

Ill

A Decision That White Defendants May Challenge

Discrimination Against Blacks in Jury Selection Should

Be Made Fully Retroactive.

Petitioner, in his brief, explains why, under the standards

set out by this Court in Stovall v. Denno, 388 U.S. 293

(1967), a decision that white defendants may challenge the

illegal exclusion of blacks from juries should be made fully

retroactive. We add two brief comments.

First, we urge that the most analogous case is Wither

spoon v. Illinois, 391 TJ.S. 510 (1968). There, this Court

held that its new rule that persons with scruples against

the death penalty could not be excluded from juries in capi

tal cases was to be fully retroactive. This was because the

wrongful exclusion of such persons “undermined ‘the very

integrity of the . . . process’ ” by which a defendant’s fate

7

was determined. 391 U.S. at 523, n. 22. Similarly here, for

the reasons set out above, the unlawful exclusion of blacks

totally undermines the proper functioning of the jury

system.

Second, we suggest that the retroactive giving to white

defendants a right long enjoyed by blacks will not have a

harmful effect on the administration of justice, i.e., it would

not result in a general jail release. It must be remembered

that what is involved here is the possible application of

the Whitus decision to whites. Therefore, an examination

of the impact of Whitus on black prisoners is instructive.

(1) According to data available from the Georgia Depart

ment of Corrections, in the year July 1967—July 1968 (the

year following Whitus), a substantial majority of the in

mates of the Georgia prison system were black (5139 out

of 8629). Thus, the retroactive application of a decision

favorable to petitioner in this case would affect a minority

of those convicted in Georgia. (2) As the figures cited

above show, Whitus had the potential of releasing nearly

60% of those incarcerated in Georgia when it was handed

down. Nevertheless, subsequent figures indicate no such

general jail delivery. Thus, in 1971 the number of blacks

and the total number of prisoners was approximately the

same (4991 out of 8205) as in 1967-68. There is no reason

to expect any more deleterious effect from a decision in

this case than there was from Whitus.

8

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the judgment of the Court of

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

Jack Greenberg

James M. N abrit, III

Charles Stephen Ralston

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for the NAACP Legal

Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C. 219