Plaintiffs' Reply to Defendant's Opposition to Plaintiffs' Motion for Partial Summary Judgement

Public Court Documents

June 13, 1991

17 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Matthews v. Kizer Hardbacks. Plaintiffs' Reply to Defendant's Opposition to Plaintiffs' Motion for Partial Summary Judgement, 1991. ee7627f9-5c40-f011-b4cb-002248226c06. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1f5dfa63-5f2c-46b7-a4f9-dc81c3d54d57/plaintiffs-reply-to-defendants-opposition-to-plaintiffs-motion-for-partial-summary-judgement. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

‘ $ ii

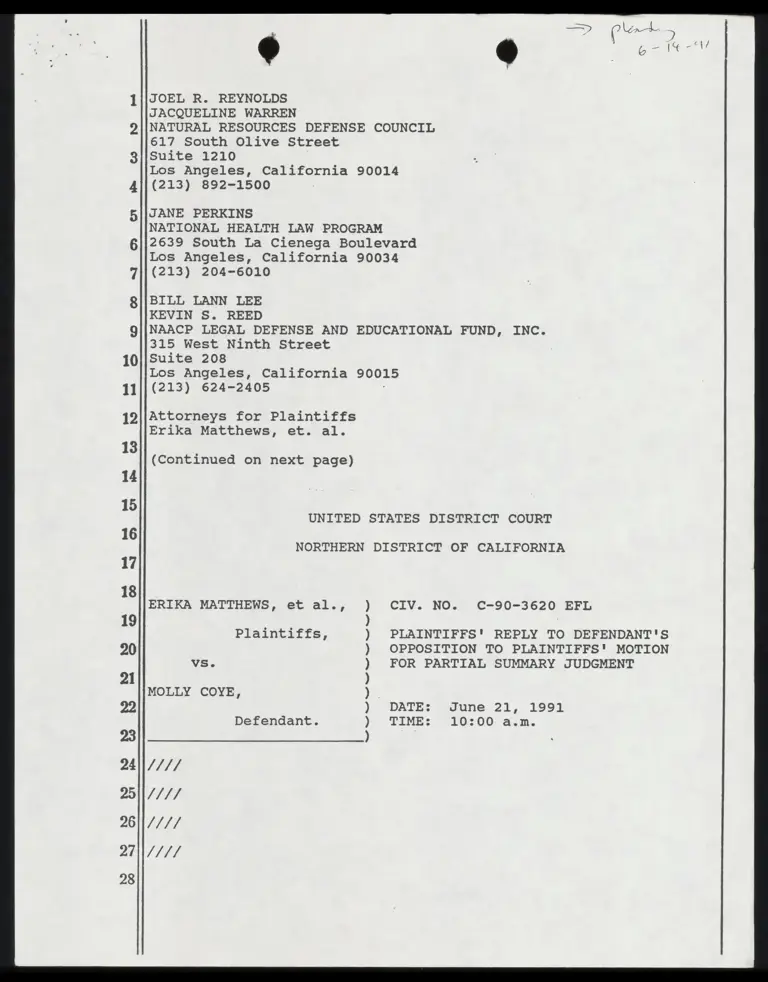

1{|JOEL R. REYNOLDS

JACQUELINE WARREN

2 |INATURAL RESOURCES DEFENSE COUNCIL

617 South Olive Street

3||suite 1210 |

Los Angeles, California 90014

411 (213) 892-1500

5||JANE PERKINS

NATIONAL HEALTH LAW PROGRAM

6/2639 South La Cienega Boulevard

Los Angeles, California 90034

711 (213) 204-6010

8||BILL LANN LEE

KEVIN S. REED

g||NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

315 West Ninth Street

10||Suite 208

Los Angeles, California 90015

11] (213) 624-2405 :

12||Attorneys for Plaintiffs

Erika Matthews, et. al.

13

(Continued on next page)

14

15

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

16

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA

17

18

ERIKA MATTHEWS, et al., ) CIV. NO. C=-90-3620 EFL

19 )

Plaintiffs, ) PLAINTIFFS' REPLY TO DEFENDANT'S

20 ) OPPOSITION TO PILAINTIFFS' MOTION

vs. ) FOR PARTIAL SUMMARY JUDGMENT

21 )

MOLLY COYE, y.

22 ) DATE: June 21, 1991

Defendant. ) TIME: 10:00 a.m.

23 )

2411/77/77

25\17/7/7/7

261/777

271/777

28

WO

0

0

J

O&

O

O

v

=

WW

NN

m

=

be

d

pe

d

pe

d

pd

pe

d

pe

d

pe

d

ed

pe

d

CO

=I

OH

OO

i=

»

WW

NN

=

O

MARK D. ROSENBAUM

ACLU FOUNDATION OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA

633 South Shatto Place

Los Angeles, California 90005

(213) 487-1720 :

SUSAN SPELLETICH

KIM CARD

LEGAL AID SOCIETY OF ALAMEDA COUNTY

1440 Broadway

Suite 700

Oakland, California 94612

(415) 451-9261

EDWARD M. CHEN

ACLU FOUNDATION OF NORTHERN CALIFORNIA

1663 Mission Street

Suite 460

San Francisco, California 94103

(415) 621-2493

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

Erika Matthews, et al.

////

////

[lf

////

[11

hiss

////

////

////

/7//

[11

[1

////

11

///f

/ 1

WO

W

O0

0

=3

J

O&

O

O

v

=

WW

NN

be

d

pd

he

h

md

fe

d

pe

d

fee

d

fe

d

pe

d

pe

d

©

00

=~

3

OO

O

v

w=

WW

NN

=m

Oo

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION [ J LJ LJ Ld L J § ® * * * L J [J LJ LJ LJ [J Ld Ld Ld LJ LJ ® Ld ® [J 1

ARGUMENT ® LJ ® [J [ J LJ LJ ® ® [J [J LJ LJ ® LJ LJ LJ Ld Ld * ® LJ LJ ® LJ [J 2

I. THE MEDICAID STATUTE, AUTHORITATIVELY CONSTRUED,

REQUIRES BIOOD LEAD TESTING OF ALL ELIGIBLE CHILDREN

BELOW AGE SIX *® L J LJ ® L J » ® ® » ® Ld ® Ld LJ LJ ® LJ ° ® ® \ 2

A. The Manual does not call for physician

discretion, as interpreted by DHS. eS A RR 4

B. The terms "screening" and "test" are used

SNE rcNanNOCAI IY evs ae aie te vie yw vie ee ae 4

Cc. The Manual does not support DHS' expense and

Ph I y SPOUT WY a a ey ee ee 7

11. THE HCFA LETTERS AREF ENTITLED TO NO DEFERENCE. + + « + 8

III. DHS' INTERPRETATION DEVIATES FROM ACCEPTABLE MEDICAL

PRACTICE L J LJ LJ ® [J L J LJ [J LJ * ® - Ld LJ * * \d LJ LJ * ® LJ LJ LJ °)

CONCLUS ION L J LJ r . LJ ® LJ LJ » LJ [J LJ LJ LJ Ld LJ ° LJ LJ LJ Ld LJ LJ LJ LJ 12

1 TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page(s)

2

3|| cASES

4|| Chandler v. Roudebush,

425 U.S. 840, 96 S.Ct. 1949, 48 L.Ed 24d 416 (1976) "is enw wD

5

Citizens Action leaque v. Kizer,

01} 887 F.2@ 1003 (Oth Civ. 1080) + vo eo 0 v.o vo vs inivis os on. vo o:9

7II NLRB v. United Food & Commercial Workers,

484 U.S. 112, 108 S.Ct. 413, 98 L.Ed.2d 429 (1987) $0 wwe wd

8

Pottgieser v. Kizer,

Gj] 906 Fe2@ 1319 Oth Cir. 1000) is vo a oc ¢ ov 0 so s.'¢%e 5 siie v9

10|| Sullivan v. Everhart,

494 U.S. 83, 110 S.Ct. 960, 108 L.Ed.2d 72 (1990) ie. ei, 3 im

11

12|| STATUTES

131] 42 USC. § 13068 (TICIVUBIII) 0 fete oiiv nin vv sin vu ois »B

14 42 .8.C. § 1396(d)r LJ ® ® * [J ® ® ® i» \ LJ a » » L J » » LJ LJ LJ LJ] El

15 42 U.8.C. § 247b-1 = e © eo eo eo oo ® ° ® N ° . ° . ® ® ® ° ° ° e 6

16 42 U.5.C. § 247 (C) @® L J ® [ J ® L J L J *» ® L J [ J [ J L J [J L J ® L J LJ LJ LJ [ J » 6

17 42 T.858.C. § 300k ® [ J [ J L J ® L J L J L J LJ LJ [ J L J ® [J » L J L J L J LJ [ J LJ ® [ J 6

18 42 H.8.C. § 300m L J [ J [J L J ® » ® » L J Rd *® LJ [J eo, ® L J L J L J ® LJ LJ *® L J 6

19 42 U.S.C. § 701 (a) L J » » ® L J ® ® Ad L J ® RA LJ * \ L J L J L J LJ LJ LJ » * 6

20

OTHER AUTHORITIES

21

State Medicaid Manual

22

§ 5123.2 Ra A L J » » ® ® ® L J L J LJ L J LJ L J LJ LA » L J L J a L J * \J Ld LJ 5

23

§ 5123.2.A ° ® LJ ® ® ° ° » ° » » » * ° ® ° ® ° ° » ° ® 5, 7

24

BEd 030 2aD) oe sie oie hie. Rie eee ee 3, 8,8,

25 i

§ 5123.2.F Ld L J L J ®» ® *® LJ ® ®» LJ LJ ® ®» » LJ * - LJ] LJ L J » » Ld \d 5

26

8 512302 0G ve te and he vim eles ee iy hy gr a gle BD

27

28

ii

Ww

W

O0

0

=

O&

O

O

r

i=

LW

NN

m

=

NO

AO

bk

bd

mk

be

d

pd

fe

d

pe

d

fee

d

pe

d

pe

d

O

O

©

O0

0

=

OH

O

v

a

W

N

=

OO

R

R

B

N

M

N

0

3

Oh

O

t

w=

INTRODUCTION

The Department of Health Services ("DHS" or "Department")

concedes that "lead poisoning is the most significant environmental

health problem facing california children today and that early

detection of elevated blood lead levels in young children is of

singular importance in preventing or ameliorating a number of

debilitating conditions which can last a lifetime." DHS'

Opposition at 1-2. Yet, the Department refuses to do the only

thing that all of the declarants in this cane agree must be done to

detect whether a child actually suffers from lead poisoning, namely

perform an initial $7.50 lead blood test. Rather, the Department

argues that, unlike other laboratory tests which it is specifically

required to include in the EPSDT screen (e.dg., tuberculosis, sickle

cell), the one laboratory test mandated by name by Congress -- lead

blood level assessment =-- is discretionary with the physician.

Common sense, as informed by the plain meaning of the controlling

federal authority contained in the State Medicaid Manual ("Manual")

and the clear purpose of the statute, dictates that DHS must be

wrong. Otherwise, the federal scheme for early prevention and

detection of lead poisoning pays only lip service to this

environmental hazard and allows lead poisoning to go undetected in

our poorest communities.

As shown below, DHS essentially makes three arguments in

support of its position. First, it attempts to tar plaintiffs as

overreaching because they seek "universal lead blood testing," DHS'

Opposition at 3. This simply misstates plaintiffs' position that

the plain language of the Manual requires blood lead testing only

for Medicaid-eligible children below age six. Second, DHS cites

1

©

00

«1

OO

Ov

i

CO

ND

nN

ND

DN

N

D

te

d

pe

d

pd

bd

pe

d

pe

d

fe

d

pe

ed

pe

d

pe

d

B

D

N

N

N

N

E

M

E

N

D

N

D

O

E

S

N

o

m

R

e

o

27

28

two facially inconsistent HCFA letters it has procured as evidence

that its policy adheres to the federal requirements. Id. at 6.

Plaintiffs will show, however, that these letters are meaningless

to this case. Finally, the DHS relies upon the American Academy of

Pediatrics to argue that its position is consistent with acceptable

medical practice. Id. at 7-8. This argument, however, is rebutted

by the very authors of the report. As noted by Dr. Philip J.

Landrigan, Chairperson of the American Academy of Pediatrics

Committee on Environmental Hazards, which drafted the Academy's

1987 Statement on Childhood Lead Poisoning:

Particularly as applied to Medicaid-eligible children --

virtually all of whom exhibit one or more of the risk

factors identified in the Academy's Statement =-- blood

lead testing is essential, and it would be a serious

misreading of the Academy's Statement to suggest that, in

the Academy's view, such testing is not a required

element of any minimally adequate lead screening program

for all such children.

Landrigan Dec. at § 5. (Emphasis added.) (Exhibit X hereto).

ARGUMENT

I. THE MEDICAID STATUTE, AUTHORITATIVELY CONSTRUED, REQUIRES

BLOOD LEAD TESTING OF ALL ELIGIBLE CHILDREN BELOW AGE SIX

DHS argues that the Medicaid statute's direction to conduct

blood lead level assessments should, in essence, be set aside

because the "appropriate for age and risk factors" limitation

leaves responsibility for performing the test entirely to the

discretion of the physician. DHS' Opposition at 3. This

construction, in which the limiting language swallows whole the

statutory requirement for blood lead testing, is completely at odds

with the remedial purpose of the 1989 EPSDT amendments to expand

preexisting federal regulatory recommendations for routine blood

2

QO

00

=

OH

O

v

x

CL

O

NN

p

o

d

p

e

d

p

d

p

e

d

f

e

d

pe

ed

fe

ed

p

e

d

e

d

pe

d

©

00

=I

OH

UV

=

CO

MN

=m

Oo

lead testing of all young EPSDT children. It also has the absurd

result of watering down, rather than strengthening, the prior

regulatory recommendations. See Plaintiffs' Memorandum 12-13.!

The Manual plainly states: "Screen all Medicaid eligible

children ages 1-5 for lead poisoning." Manual, § 5123.2.D.1

(Plaintiffs' Exhibit N).2 The only way this provision has any

meaning is if it requires physicians to provide something more to

children aged 1-5 than they provide to older children aged 6 to 21,

who are also eligible for the EPSDT Program. Since all EPSDT

eligible children =-- regardless of age -- must, under the EPSDT

statute have their age and risk factors measured for the threat of

lead poisoning, the Manual must mean that young children receive

additional attention, specifically through routine administration

of a lead blood assessment generally using the erythrocyte

protoporphyrin (EP) test. |

In fact, DHS' position garners no support from the language,

design, or structure of the Manual as a whole. See Sullivan v.

Everhart, 494 U.S. 83, 108 L.Ed.2d 72, 80 (1990) ("'In ascertaining

the plain meaning of the statute, the court must look to the

particular statutory language at issue, as well as the language and

S

E

R

X

R

B

R

R

I)

oo

In fact, a recent publication of the Congress and Boards of

the 101st Congress, Office of Technology Assessment characterizes

the screening requirements of the EPSDT program as including

"laboratory tests, such as an anemia test, sickle cell test,

tuberculin test, and lead toxicity screening." U.S. Congress,

Office of Technology Assistance, Children's Dental Services Under

the Medicaid Program-Background Paper, OTA-BP-ii-78 (Washington,

D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, October 1990) (emphasis

added). (Exhibit Y hereto).

‘a11 parties agree that the statutory direction must be read

in light of the State Medicaid Manual § 5123.2.D. (Plaintiffs®

Exhibit N). Compare Plaintiffs' Memorandum at 8-9 with Defendant's

Statement of Undisputed Material Facts at 2.

3

©

0

3

OH

O

r

ix

Ww

W

NN

m=

NN

NN

NN

N

N

N

DN

NA

N

tu

b

ph

pe

nd

pe

d

pe

d

pd

pe

d

pe

d

pe

d

pe

d

design of the statute as a whole'").

A. The Manual does not call for physician discretion, as

mos—

Ld

interpreted by DHS.

The purpose and effect oF ‘tha laboratory testing section

§ 5123.2D(1l), are to enumerate the laboratory tests which are

minimally "appropriate," not to endorse unfettered medical

discretion. The introductory paragraph of the section

unequivocally directs the states to "identify as stataVide

screening requirements, the minimum laboratory tests or analysis to

be performed by medical providers for particular age or population

groups." Manual § 5123.2.D (Plaintiffs' Exhibit N). Notably, the

qualifying introductory language upon which DHS so heavily relies,

namely the statement that physicians providing EPSDT services must

use their medical judgment to determine which tests are

appropriate, must be read in context with the very next sentence

which emphasizes that, if a laboratory test is medically

contraindicated at the time of the screen, it should be provided

when "no longer medically contraindicated." Thus, a physician may,

at the time of the screen, decide to postpone an enumerated test;

the Manual does not, however, stand for the proposition that the

test need not be provided at all.

B. The terms "screening" and "test" are used interchangeably.

DHS also makes much of the Manual's use of the phrase "lead

toxicity screening" to suggest that use of a screening test was not

intended This distinction, however, is too fine. In the section

entitled "appropriate laboratory tests," the Manual is plainly

using the terms "screen" and "test" interchangeably. This is clear

enough from the last paragraph of the laboratory testing section,

©

00

=

3

OO

O

v

=

L

W

NN

N

O

N

N

O

N

N

Y

O

N

DN

NO

pe

d

pd

pm

b

pe

d

pe

d

fe

ed

fe

d

ed

pe

d

pe

d

CO

=F

C

y

O

F

s

p

CO

S

O

O

O

W

0

0

J

O

H

U

v

a

W

O

N

E

R

D

§ 5123.2D(1) (5), which expressly characterizes the preceding

subparts, including the lead screening paragraphs, as dealing with

"tests" and refers to several other procedures -- clearly

laboratory tests -- using the term "screen," i.e., "urine"

screening ... drug dependency screening and HIV screening."

Moreover, as the Department has admitted, the term "screen" is also

used in related § 5123.2.F and G to refer to vision, hearing and

dental screening tests. See Range Dec. 69-71. The "screen" in the

lead toxicity screening section, then should be read in pari

materia as the same term elsewhere in § 5123.2. See Everhart, 108

L.E4d.2d4 at 82.

Logic dictates that if the lead screening requirement

consisted of a physician's oral history-taking, it would have been

included in that part of the Manual that deals with the oral

history. However, neither the Manual, nor the statute for that

matter, discuss lead testing in provisions dealing with history-

taking. See 42 U.S.C. § 1396d(r) (1) (B) (i); Manual § 5123.2.A.

Moreover, if DHS' artful reading of the term "screen" is

correct, the Manual would result in the following anomaly: The

Department defers to physician discretion the only test that the

EPSDT statute specifically requires -- blood lead testing -- yet it

does not recognize physician discretion in the administration of

other tests, such as tuberculin skin tests, which are not

specifically required by the statute but which DHS admits are

nevertheless mandatory. DHS' Opposition at 5. See, e.qg., Chandler

v. Roudebush, 425 U.S. 840, 848 (1976) ("The plain, obvious and

rational meaning of a statute is always to be preferred to any

curious, narrow, hidden sense that nothing but the exigency of a

5

WO

O0

0

3

OO

O

v

&»

WW

NN

m=

r

d

o

r

WO

00

J

OH

O

v

x

WW

NN

=

OO

ND

ry

hard case and the ingenuity and study of an acute and powerful

intellect would discover")>.

Notably, the Manual's use of the term "screen" to refer to

laboratory tests used for screening is consistent with Congress!

use of the term in other parts of the Social Security Act. E.g. 42

U.S.C. § 701(a) ("screening of newborns for sickle cell anemia, and

other genetic disorders"); 42 U.S.C. § 300k (programs "to screen

women for breast and cervical cancer as a preventive health

measure"); 42 U.S.C. § 300m ("the screening procedure known as a

mammography:;" "the screening procedure known as a pap smear"); and

42 U.S.C. § 247(c) ("mass diagnostic screening").

Indeed, the Lead Contamination Control Act of 1988 includes a

provision giving the Centers for Disease Control authority to make

grants to state and local governments to "screen infants and

children for elevated blood lead levels." 42 U.S.C. § 247b-1.

Like § 5123.2.D.1 of the Manual, the face of the provision

indicates that "screen" necessarily refers to screening tests

because the purpose of the screening is to determine if "elevated

blood levels" exist. The legislative history, makes this

absolutely clear. See H.R. Rep. No. 100-1041, Lead Contamination

Control Act of 1988 at 17 (1988) reprinted in 1988 U.S. Code Cong.

3

8

B

R

B

R

DHS also highlights the Manual's use of the phrase "in

general" when referring to use of the EP test. DHS' Opposition at

5. It is unclear what the Department means to infer from this

highlighting. The Manual plainly endorses the general use of the

EP test as "the primary screening test" and the use of the venous

blood level measurements on children with elevated EP levels.

There is no mention of history-taking as a threshold or primary

screening test. If DHS' position in this case were correct, one

would expect the Manual to designate history-taking as the primary

screening test to be performed in all cases. There is no such

language; rather, only two blood tests, consistent with plaintiffs!

construction, are specified as "screening tests."

6

WO

W

O0

0

=

a

OH

O

r

i=

»

WW

NN

=

S

E

SO

or

Sh

vr

Sh

Sr

SN

wy

Ww

W

O

0

0

=

J

O

H

O

v

=

W

W

N

N

=

O

O

nN

pd

& Admin. News 3793, 3805 (Exhibit Z hereto) ("[T]he Committee

believes that testing infants and children for lead poisoning will

do little good if those who test positive are not given access to

sources of medical treatment and environmental intervention for the

disease"). Thus, in the context of the Social Security Act as a

whole -- as well as the EPSDT statute and Manual -- the plain

meaning of "screen" is a screening test. Because this consistent

administrative construction of the EPSDT statute contained in the

Manual is "rational and consistent with the statute", Everhart, 108

L.Ed.2d at 80, guoting NIRB v. United Food & Commercial Workers,

484 U.S. 112, 123 (1987), it is dispositive.

C. The Manual does not support DHS! expense and utility arguments

The Manual explodes DHS' wholly specious claims that it is

avoiding "a considerable price tag" and unduly invasive, "useless

blood tests." Opposition at 5-6; Decs. of Gregory and Range at

qf 2. In fact, the Manual requires that the very same EP test be

used to screen for iron deficiency, noting that it is a "simple,

cost-effective tool for screening." Manual § 5123.2A.2

(Plaintiffs' Exhibit N). Unless DHS is also violating the law by

failing to require EP testing to screen for iron deficiency, the

incremental cost of blood lead testing for lead poisoning is

minimal and wholly acceptable because the more costly venous blood

measures are required only for children whose EP levels are in the

danger zone.

Moreover, DHS is hardly in a position to complain about lead

screening tests since it admits that "early detection of elevated

blood lead levels in young children is of singular importance in

preventing or ameliorating a number of debilitating conditions

7

©

O0

0

=~

OO

O

r

=

CW

NN

=

N

N

N

DN

AN

td

pd

pd

pe

d

ed

pe

d

fe

d

ed

pe

d

pe

d

which can last a lifetime." DHS' Opposition at 2. As Dr.

Landrigan, Chairperson of the American Academy of Pediatrics

Committee which drafted the 1987 Academy Statement, that DHS has

proffered, put it:

It is simply nonsense to suggest that the benefits of

early lead poisoning detection by a blood lead level test

are outweighed by the costs of the tests or the

invasiveness of the testing procedure. Not only is the

drawing of blood a common practice in a typical medical

examination, but the long-term benefits of early

detection and treatment are incalculable. Although an

oral examination may perhaps be cheaper and less

invasive, it is an unreliable screening tool and

inevitably will result in lead-exposed children going

undetected and untreated.

Landrigan Dec. at § 6. As against the $7.50 EP finger prick test

and the $22.50 venous test, the most recent federal study has found

that $4,631 is avoided for every child who does not have to be

treated for lead poisoning and that preventing a single deciliter

increase in blood lead level correlates with an increase in a

person's average expected wage of $1,147. Needleman Dec. Exhibit

A, Strategic Plan for the Elimination of Childhood lead Poisoning

at xiv (Feb. 1991) (elimination of lead poisoning avoids $62

billion of medical care, special education, institutionalization,

loss of productivity, and loss of lifetime earnings) (Plaintiffs

Exhibit B).

II. THE HCFA LETTERS ARE ENTITLED TO NO DEFERENCE

Notwithstanding the Department's admission that only Health

Care Financing Administration ("HCFA") regulations and the HCFA

Manual are controlling, Defendant's Statement of Undisputed

Material Facts at 2, DHS offers two letters from the local HCFA

office as support for its statement that HCFA would find DHS in

8

Ww

W

00

3

OH

O

v

=

CW

NN

=

d

h

P

e

d

f

e

d

p

e

d

p

e

d

b

e

d

f

e

d

p

e

d

pe

ed

pe

ed

©

00

«J

OO

OV

=

O

N

=

OO

x

3

8

KE

R

B

R

B

R

compliance with federal law whether or not it used lead tests. DHS

Opposition at 6. Under both Citizens Action League v. Kizer, 887

F.2d 1003, 1007 (9th Cir. 1989) and Pottgieser v. Kizer, 906 F.2d

1319, 1323 (9th cir. 1990), the letters from the HCFA employee

(Plaintiffs' Exhibits V and W) are of no legal consequence and

entitled to no deference. Each "lack[ed] the indicia of

deliberative administrative review" and "appear[ed] to have been

written for the purposes of this litigation only." Pottagieser, 906

F.2d at 1323 (quoting Citizens Action League). Here, the letters

were drafted solely for purposes of this litigation. Ruth Range

testified that as to the second letter, in which the DHS procedure

is finally described correctly, she spoke to a HCFA representative

for "two minutes." Range Depo. at 65 (Plaintiffs' Exhibit J). The

HCFA representative asked no questions concerning procedures

utilized to aSSeEs for risk or the number of eligible children

receiving some sort of blood lead level test. Id. Range said the

representative "seemed to indicate that [the procedure] was fine,"

but "[n]Jot in so many words." Id. Under these circumstances,

neither of these letters is of any consequence or entitled to any

deference.

ITI. DHS' INTERPRETATION DEVIATES FROM ACCEPTABLE MEDICAL PRACTICE

DHS erroneously claims that its position is "consistent with

acceptable medical practice" because it parallels recommendations

of a 1987 Statement by the American Academy of Pediatrics. Exhibit

A to Gregory Dec. ("1987 Academy Statement"). DHS, however, does

not dispute that the American Academy of Pediatrics has

specifically recommended since 1977 that all children ages 1-5 in

WW

00

=~

OH

O

r

=

WW

NN

=

bd

bh

pd

fe

d

he

d

ed

be

d

fe

d

fe

d

ed

©

00

3

OO

O

v

i»

W

N

=

O

21

3

27

28

the EPSDT program, namely young children who live under conditions

of poverty, should be tested for lead poisoning, see Plaintiffs’

Memorandum at 12. Nor does DHS dispute that, unlike the Manual,

the 1987 Academy Statement is not focussed on poor children but

addressed to children of all incomes and all age groups.

Significantly, the 1987 Academy Statement finds that "[lead

poisoning] is particularly prevalent in areas of urban poverty" and

"[plrevalence rates for elevated blood levels are highest among

families . . . with incomes of less than $15,000 per year." 1987

Academy Statement, Exhibit A to Gregory Dec. at 457, 458. As Dr.

Landrigan, Chairperson of the Pediatric Committee which drafted the

1987 Academy Statement, stresses:

Even as currently written, however, the Academy's

Statement reflects the Academy's view that periodic

testing of all preschool children is medically necessary.

Particularly as applied to Medicaid-eligible children --

virtually all of whom exhibit one or more of the risk

factors identified in the Academy's Statement -- blood

lead testing is essential, and it would be a serious

misreading of the Academy's Statement to suggest that, in

the Academy's view, such testing is not a requirement of

any minimally adequate lead screening program for all

such children. :

Landrigan Dec. at § 5 (Exhibit X hereto). Indeed, Dr. John Rosen,

an acknowledged resource for the Statement, points out that over

90% of the young children he treats for lead poisoning are Medicaid

recipients. Rosen Supplemental Dec. at q 4 (Exhibit AA hereto).

He adds:

[I]t would be a gross distortion of the Academy's

Statement to interpret it as recommending anything less

than mandatory testing of young Medicaid-eligible

children, both because they are as a class unquestionably

at increased risk of lead exposure and lead poisoning and

because of the vastly different circumstances that

affluent children may face.

Jd, at «4 5,

10

W

O0

0

3

O&

O

O

r

=

L

W

NN

=

bo

d

be

d

fu

k

pe

d

bm

d

f

e

d

pe

d

pe

d

pe

d

pe

d

©

O0

0

=

O

H

O

v

=

Q

W

N

N

=

O

O

B

R

It is obvious that DHS is unable to present one shred of

medical support, other than its two employee declarants, on behalf

of its claim that history-taking is a recognized and bona fide

method of blood lead screening. And, as to these declarants, Ruth

Range testified that she had received no specialized training in

the area of lead poisoning, had done no writing on the subject, and

did not consider herself an expert in terms of lead toxicity.

Range Dec. at 13 (Plaintiffs' Exhibit J). Dr. Gregory similarly

acknowledged that she lacked special expertise in the area of lead

or lead toxicology, had done neither writing nor research and did

not consider herself an expert on lead or lead poisoning. Gregory

Depo. at 12 (Plaintiffs' Exhibit 5."

By contrast, the Manual and all the other authority cited by

plaintiffs, see Plaintiffs' Memorandum 10-13, recognize only blood

lead testing as the accepted screening method for young Medicaid-

eligible children. The reason for unanimity about the need for

blood level testing to screen for lead poisoning is obvious: Lead

poisoning is often asymptomatic. No amount of verbal interview can

detect an elevated blood lead level. Plaintiffs' Memorandum at 4;

1987 Academy of Pediatrics Statement, Exhibit A to Gregory Dec. at

457 ("[T)lhere are many asymptomatic children with increased

absorption of lead in all regions of the United States" and

N

O

N

N

O

N

‘Dr. Gregory's declaration reports a telephone conversation to

Raymond Koteras, at the American Academy of Pediatrics, purportedly

to the effect that the Academy's 1987 Statement remains the

position of the Academy. Gregory Dec. at § 7. However, Mr.

Koteras stated to plaintiffs' counsel that he is "certainly not a

lead toxicity ‘expert ‘but .rather a "staff person” with

responsibilities to several Academy committees. Rosenbaum Dec. at

5. 2 {Exhibit BB hereto). He repeatedly stated that it was

inappropriate for him to "confirm or refute" any Academy position.

Id. at '¢ 1.

11

Ww

W

0

0

=~

OO

O

v

=

CW

NN

m

=

| \

)

nN

NN

DN

td

pd

pd

pe

d

ed

pn

d

fe

d

ed

pe

d

pe

d

E

N

E

B

D

E

D

m

n

m

t

n

m

e

m

s

e

b

w

27

28

"[N]europsychologic dysfunction, characterized by reduction in

intelligence and alternation in behavior has been shown

conclusively to occur in asymptomatic children with elevated blood

lead levels.").

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated above and in plaintiffs' memorandum of

points and authorities, plaintiffs' motion for partial summary

judgment should be granted.

Dated: June 13, 1991 Respectfully submitted,

Natural Resources Defense Council

National Health Law Program

ACLU Foundation of

Southern California

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund

Legal Aid Society of Alameda County

ACLU Foundation of Northern California

By: Qed Ruuirilda gp

Jbel R. Reyholds A

Natural Resources Defense Council

By: Qaunt Pinks ya

Jédne Perkins

National Health Law Program

By: AQ RISeuum

Mark D. Rosenbaum

ACLU Foundation of Southern

California

By: Bul | aun Lt

Bill Lann Lee

NAACP Legal Defense a Educational

Fund

By: kun Cond up

Kim Card

Legal Aid Society of Alameda County

12

DO

O0

0

=~

OH

O

v

=»

L

W

NN

=

nN

nN

DN

ND

te

d

pe

d

pd

pd

fk

pe

d

ee

d

pe

d

pe

d

pe

d

DECLARATION OF SERVICE BY U.S. MATL

I, HALIMA GIDDINGS, declare:

I am a resident of the County of Los Angeles, California; I

am over the age of eighteen (18) years and not a party to the

within cause of action; I am employed in the County of Los

Angeles, California; and my business address is 633 South Shatto

Place, Los Angeles, California 90005-1388.

On June 14, 1991 I served the foregoing document(s)

described as: PLAINTIFFS! REPLY TO DEFENDANT'S OPPOSITION TO

PLAINTIFFS' MOTION FOR PARTIAL SUMMARY JUDGMENT on the parties of

record in said cause, by delivering a true and correct copy

thereof enclosed in a sealed envelope addressed as follows:

HARLAN E. VAN WYE LINDA JANE SLAUGHTER

Deputy Attorney General State of California :

Department of Justice Department of Health Services

2101 Webster Street Office of Legal Services

Oakland, CA 94612-3049 714 "P" Street, Room 1216

Sacramento, CA 95814

I am "readily familiar" with the office's practice of

collection and processing correspondence for mailing. Under that

practice it would be deposited with U.S. postal service on that

same day with postage thereon fully prepaid at Los Angeles,

California in the ordinary course of business. I am aware that

on motion of the party served, service is presumed invalid if

postal cancellation date or postage meter date is more than one

day after date of deposit for mailing in affidavit.

I declare under penalty of perjury under the laws of the

State of California that the foregoing is true and correct.

Executed on June 14, 1991 at Los Angeles, California.

Halima Giddings