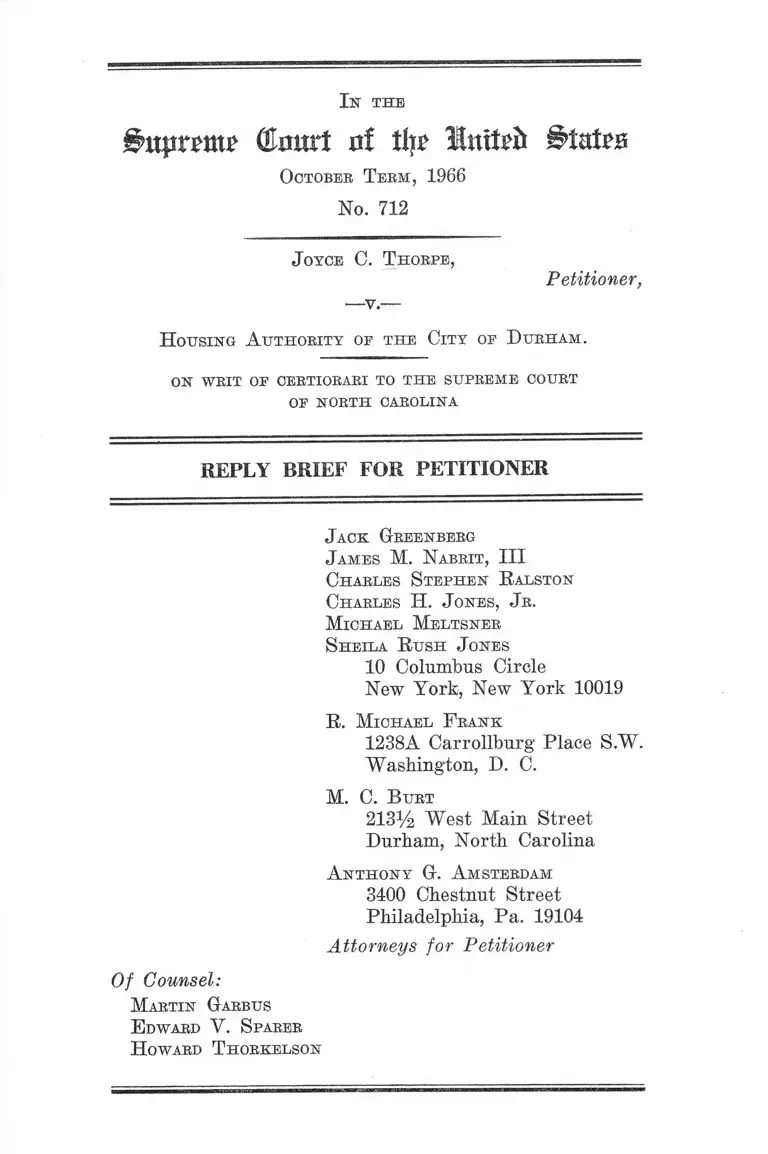

Thorpe v. Housing Authority of the City of Durham Reply Brief for Petitioner

Public Court Documents

October 3, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Thorpe v. Housing Authority of the City of Durham Reply Brief for Petitioner, 1966. 8afe1323-c69a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1f6e61d2-0e34-4390-a2a5-70ff8b1a32fa/thorpe-v-housing-authority-of-the-city-of-durham-reply-brief-for-petitioner. Accessed February 01, 2026.

Copied!

I n the

Bwpvmt Okmrt of % luttei*

October T eem, 1966

No. 712

J oyce 0 . T horpe,

Petitioner,

H ousing A uthority op the City op D urham.

on writ op certioeaei to the supreme court

OP NORTH CAROLINA

REPLY BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Charles Stephen R alston

Charles H. J ones, J r.

Michael Meltsner

S heila R ush J ones

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

R. Michael F rank

1238A Carrollburg Place S.W.

Washington, D. C.

M. C. B urt

213% West Main Street

Durham, North Carolina

A nthony G. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pa. 19104

Attorneys for Petitioner

Of Counsel:

Martin Garbus

E dward Y. Sparer

H oward T horkelson

I N D E X

PAGE

Introduction ................ ................. —„ .... ........................... 1

I. The Judgment Below May Also Be Reversed on

the Basis of a New Federal Administrative Rule

Adopted February 7, 1967 ........ 2

II. The History of the Superseded Policy Relied on

by Respondent Shows Its Potential and Purpose

for Abuse ................................................................... 8

A ppendix

Public Housing Administration Circular July 28,

1954 ...... la

H.U.D. Circular Dated May 31, 1966 .................... 2a

H.U.D. Circular Dated February 7, 1967 ............ . 4a

T able op Cases

Ashwander v. T.V.A., 297 U.S. 288 ----------------- — ..... 8

Bowles v. Strickland, 151 F.2d 419 (5th Cir. 1945) ..... 4

Bruner v. United States, 343 U.S. 112 ..... ................... - 3

Congress of Racial Equality v. Clinton, 346 F.2d 911

(5th Cir. 1964) ........ .......................................... ......... 4

Dixon v. Alabama State Board of Education, 294 F .2d

150 (5th Cir. 1961), cert, denied 368 U.S. 930 ......... 7

Doughty v. Maxwell, 376 U.S. 202 ............................... 5

Ex parte Collett, 337 U.S. 55 ............... - ...............-..... - 4

11

PAGE

Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 ............................. 5

Gonzalez v. Freeman, 334 F.2d 570 (D.C. Cir. 1964) .... 7

Griffin v. California, 380 U.S. 609 ........... ........... ......... 5

Hamm v. Rock Hill, 379 U.S. 306 ................ ................ 4

Hoadley v. San Francisco, 94 H.S. 4 ............................. 4

Hyser v. Reed, 318 F.2d 225 (D.C. Cir. 1963), cert, de

nied, 375 U.S. 957 ............. .......................................... 7

Johnson v. New Jersey, 384 U.S. 719 ........... ....... ........ 5

Linkletter v. Walker, 381 U.S. 618 ............................... 4

Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643 ............................................ 4, 5

Massey v. United States, 291 U.S. 608 ......................... 4

O’Connor v. Ohio, 385 U.S. 92 ....................................... 5

Orr v. United States, 174 F.2d 577 (2nd Cir. 1949) .... 4

Rachel v. Georgia, 342 F.2d 336 (5th Cir. 1965) ......... 4

Rudder v. United States, 105 A.2d 741 (D.C. Mnn. App.

1954), reversed 226 F.2d 51 (D.C. Cir. 1955) .....9,10,11

Schoen v. Mountain Producers Corporation, 170 F.2d

707 (3rd Cir. 1948) ........................ ......... .......... .......... 4

United States v. Chambers, 291 U.S. 217............... ...... 4

United States v. LaVallee, 330 F.2d 303 (2nd Cir.

1964) ...................................................... ........................ 5

United States v. Schooner Peggy, 1 Cranch. 103 ..... 4

I l l

Statutes:

Act August 31, 1951, c. 376, Title I, § 101, 65 Stat. 277 10

Act July 5, 1952, c. 578, Title I, § 101, 66 Stat. 403 ...... 10

Act July 31, 1953, c. 302, Title I, § 101, 67 Stat. 307 .... 10

42 U.S.C. § 1404(a) ......................................... 3

42 U.S.C. § 1408 .................. 3

42 U.S.C. § 1411(c), Gwinn Amendment .................. 10

42 U.S.C. § 1434 ................................... 3

Other Authorities:

Local Housing Authority Management Handbook, Part

IV, Section 1—Occupancy Policies, Department of

Housing and Urban Development (July 1965) ....... 8, 9

41 Op. Atty. Gen., April 26 .............. ..... ......... ...... ........ 10

PAGE

In the

tour! nf % Inttefr l&tnteB

October Term, 1966

No. 712

J oyce C. T horpe,

— v.—

Petitioner,

H ousing A uthority op the City op D urham.

REPLY BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

Introduction

On February 7, 1967, after petitioner’s brief was filed

in this Court, the Department of Housing and Urban

Development issued a directive to all local housing au

thorities prescribing new procedures for the eviction of

low income public housing* tenants. The new federal re

quirement refutes the argument made by the respondent

Housing Authority in this case that its action conforms

with the federal administrative policy.1 More importantly,

the new federally prescribed procedures may afford a new

and independent ground for reversal of the judgment of

the North Carolina courts in petitioner’s case. We discuss

the new procedural requirements and their relationship

to this case in part I, infra.

In part II, infra, we discuss the previous policy of the

federal Public Housing Administration,la relied upon by

respondent to justify its actions in petitioner’s case.

1 See “ Brief for Housing Authority of the City of Durham,” p. 11.

la Now the Housing Assistance Administration of the Department of

Housing and Urban Development.

2

I.

The Judgment Below May Also Be Reversed on the

Basis of a New Federal Administrative Rule Adopted

February 7, 1967.

The February 7, 1967, circular issued to all local hous

ing authorities by Mr. Don Hummel, who is Assistant

Secretary for Renewal and Housing Assistance of the

Department of Housing and Urban Development (herein

after referred to as HUD), is reproduced in the appendix

to this brief, infra, pp. 4a-6a.

The circular first makes reference to pending lawsuits

“challenging the right of a Local Authority to evict a

tenant without advising him of the reasons for such evic

tion.” It then states:

Since this is a federally assisted program, we believe

it is essential that no tenant be given notice to vacate

without being told by the Local Authority, in a private

conference or other appropriate manner, the reasons

for the eviction, and given an opportunity to make

such reply or explanation as he may wish.

The directive then provides that, in addition to inform

ing the tenant of the reason for any proposed eviction,

each local authority shall maintain written records of

every eviction which are to be available for review by

HUD representatives, and should contain certain specified

information. This circular superseded a prior circular

dated May 31, 1966, which is reproduced in the appendix

hereto, infra, p. 2a. The May 31, 1966, circular had

stated that the Public Housing Administration “strongly

urge[d], as a matter of good social policy, that Local

Authorities in a private conference inform any tenants

3

who are given such notices of the reasons for . . . [evic

tion]

The circular issued February 7, 1967, unlike the earlier

circular-, contains mandatory language. The authority of

the federal agency to make such rules and regulations is

conferred by the federal housing laws.2 We believe that

the new federal rule confers rights enforceable by in

dividual low-income tenants, and submit that whatever

may be the full scope of the individual rights conferred

by the new rule, it must at least be available as a defense

to a suit maintained in a state court by a local housing

authority seeking to evict a tenant in violation of the

rule.

It is plain, we think, that if the present rule had been

in effect when the respondent sued to evict Mrs. Thorpe

in September 1965, Mrs. Thorpe would have had a com

plete defense to the suit. Under the Supremacy Clause

the state courts would have been bound to recognize her

defense that the Durham Authority issued its notice can

celling her lease in violation of the governing federal

procedural requirement.

We urge that this newly adopted procedural rule should

now be applied to petitioner’s case in accordance with

the generally applicable principle that modal or procedural

changes will be applied to pending litigation. This gen

eral tendency to apply new procedural regulations to

pending cases is very strongly developed in the law. The

policy is to apply the law as it exists at the time a court

is called upon to decide pending litigation. It is exempli

fied by such cases as Bruner v. United States, 343 U.8.

2 See 42 U.S.C. § 1408. See also, 42 U.S.C. § 1404a. The authority of

the federal agency to require records to be maintained is conferred by

42 U.S.C. § 1434."

4

112 (suit by employee against United States; pending

certiorari in Supreme Court on question of jurisdiction

of district court Congress amended statute making it clear

that there was no such jurisdiction; the new statutory

rule was applied to the pending case); Ex parte Collett,

337 U.S. 55 (new code provision applying forum non

conveniens to FELA cases applied to pending case); Orr

v. United States, 174 F.2d 577 (2nd Cir. 1949) (change in

venue provisions applied in pending case); Schoen v.

Mountain Producers Corporation, 170 F.2d 707 (3rd Cir.

1948) (change in rule of forum non conveniens applied in

pending case); Bowles v. Strickland, 151 F.2d 419 (5th

Cir. 1945) (procedural rule change relating to filing of

suit under Emergency Price Control Act applied in pend

ing case); Hoadley v. San Francisco, 94 U.S. 4 (change in

removal statute applicable to case pending in state court);

and Congress of Racial Equality v. Clinton, 346 F.2d 911

(5th Cir. 1964), and Rachel v. Georgia, 342 F.2d 336 (5th.

Cir. 1965) (change in statute to allow appeal of remand

order in civil rights removal case applied to pending cases).

Of course, Hamm v. Rock Hill, 379 U.S. 306, illustrates

the application of the rule applying a new statute to de

cide substantive rights in a pending case. See also, United

States v. Schooner Peggy, 1 Cranch. 103; United States

v. Chambers, 291 U.S. 217; Massey v. United States, 291

U.S. 608. The effectuation of the purpose of the new

statutory regulation, as perceived by this Court, was

strongly influential in these cases. And, similarly, in de

ciding whether or not to apply new judicial decisions to

pending cases—or even retrospectively to cases which have

become final—the Court has looked to the purpose of the

rule involved.3

3 See, for example, Linkletter v. Walker, 381 U.S. 618, holding that

the rule of Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643, would be applied only prospee-

5

Application of the new HUD rule of February 7, 1967,

in this case is justified by a variety of considerations, in

cluding the language of the circular, its purpose, and the

general tendency of this Court’s decisions, just discussed,

to apply procedural innovations to pending cases.

First, we believe that analysis of the language of the

circular supports its application to petitioner’s case. The

first paragraph of the circular (appendix, infra, p. 4a)

which refers to the dissatisfaction caused by the prior

practices and the litigation filed throughout the United

States challenging those practices, reflects a concern for

doing justice for the individuals who have focused atten

tion on the practice. The second paragraph {ibid.) pre

scribing an “essential” requirement that a tenant be told

the reasons for the eviction and “given an opportunity to

make such reply or explanation as he may wish” is time

less. The paragraph contains no language of futurity. In

contrast, the third paragraph {ibid.), establishing a record

keeping requirement, does expressly refer to the future

and applies “ from this date,” i.e., February 7, 1967. The

final paragraph, which says that the earlier circular

(strongly urging that tenants be told reasons for evic

tion) is now superseded, is also suggestive of a displace

ment of policy in a manner consistent with retroactivity.

Second, just as was true with respect to the federal

policy in Ilamm v. Rock Hill, 379 U.S. 306, it is fair and

tively because the purpose of the rule was to deter unlawful conduct, and

this purpose would not be served by retrospective application of the

exclusionary rule. Of course, the Mapp decision was applied to cases

pending on appeal at the time of Mapp. Johnson v. New Jersey, 384

U.S. 719, 732. See also, O’Connor v. Ohio, 385 U.S. 92, which applies

the Fifth Amendment principle of Griffin v. California, 380 U.S. 609, to

a pending case. And see the decisions giving retrospective effect to the

right to counsel as declared in Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335, e.g.,

Doughty v. Maxwell, 376 U.S. 202; United States v. LaVallee, 330 F.2d

303 (2nd Cir. 1964).

6

just to apply the new and more enlightened policy so that

it will benefit those whose protests prompted the new rule.

Third, this case involves a procedural regulation in the

classic sense; it relates to notice and the right to be heard.

The new rule requires procedural safeguards prior to

the initiation of an action to evict, but does not deprive

the local housing authority of its right to maintain evic

tion proceedings after compliance with the prescribed pro

cedures. The requirement would not be duplicated or waste

ful since the respondent authority has never given peti

tioner the benefit of such procedures.

There remains, of course, the question of whether the

new federal administrative rule conforms to the require

ments of the Constitution and does actually provide pro

cedures sufficient to protect petitioner’s rights under the

Due Process Clause. We have argued in our Brief that

petitioner was entitled to notice of the reason her low

income housing benefits were cancelled and also was en

titled to an administrative hearing in order to contest the

factual basis for the local authority’s action. The HUD

circular of February 7, 1967, is not explicit with respect

to several important matters affecting the constitutional

claim. We urge that the Court construe the HUD rule to

require at least the minimum safeguards necessary to

afford basic fairness.

The HUD circular states that tenants must be told “ the

reasons for the eviction” and that the records shall con

tain a statement of “Specific reason(s) for notice to

vacate.” It indicates that “if a tenant is being evicted

because of undesirable actions, the record should detail

the actions which resulted in the determination that evic

tion should be instituted.” We urge that the Court con

strue these provisions to mean that tenants must be ad

7

vised of the facts on the basis of which the agency pro

poses to take action, including a statement of the informa

tion on the basis of which the agency believes the facts

asserted to be true.

The HUD circular does not use the word “hearing” but,

rather, refers to notice being given “in a private con

ference or other appropriate manner” and states that the

tenant should he “given an opportunity to make such

reply or explanation as he may wish.” HUD also requires

that a record be kept including, inter alia, a “summary

of any conferences with tenant[s], including names of

conference participants.” We urge that these provisions

be interpreted to include the right to be heard in person

or by counsel at such a hearing or “conference,” and also

to include fair opportunities to challenge the grounds of

the local authority’s proposed action, to probe the facts

relied upon by the authority, and to present the tenant’s

own version of the facts. The provision should also be

interpreted to include a requirement that the agency deci

sion be rendered on the basis of the facts presented to it.

It should be stated that petitioner does not contend that

due process necessarily requires in all cases any particular

set of judicial-type hearing rules or common law eviden

tiary principles. We contend only for such procedures as

may reasonably be necessary to give a complete and fair-

airing of the controverted facts. The detailed requirements

will, of course, depend upon the circumstances of the par

ticular cased 4

4 Note, for example, the minimum requirements adopted by the Court

of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit in a state college expulsion case. Dixon

v. Alabama State Board of Education, 294 F.2d 150, 158-159 (5th Cir.

1961), cert, denied 368 U.S. 930. Cf. the procedures for parole revoca

tion set forth in Hyser v. Heed, 318 F.2d 225 (D.C. Cir. 1963), cert,

denied, 375 U.S. 957. Cf. also, Gonzalez v. Freeman, 334 F.2d 570, 578

(D.C. Cir. 1964), involving the basic standards necessary to insure fair

ness prior to debarment from participating in government contracts.

I f this Court agrees with petitioner’s view that the new

HUD regulation gives the sort of full and fair hearing

which we have just described, there is, of course, an ad

ditional reason to apply the new procedure to petitioner’s

case. Such an application, affording petitioner the full

measure of relief sought in the present case, would per

mit the Court to avoid unnecessary decision of constitu

tional questions. See Ashwander v. T.V.A., 297 U.S. 288,

341 et seq. (Mr. Justice Brandeis dissenting in part).

Such a route to disposition of the case would justify

reversal of the judgments below and a remand of the

cause with directions to set aside the eviction, leaving the

authority to take such further steps as may be conformable

to law.

II.

The History of the Superseded Policy Relied on by

Respondent Shows Its Potential and Purpose for Abuse.

The Brief of the Housing Authority of the City of

Durham, p. 11, argues that: “In following the provisions

of the lease and the published directives of the Federal

Public Housing Administration the local Housing Author

ity did not act arbitrarily.” In a footnote to the sentence

just quoted, the Authority’s Brief sets out a portion of a

provision in an HUD publication known as the L ocal H ous

ing A uthority Management H andbook, P art IV, Section 1

— Occupancy P olicies (July 1965), p. 8. We quote the

entire subparagraph:

6.d. It is recommended that each Local Authority’s

lease:

(1) Be drawn on a month-to-month basis when

ever possible. This should permit any neces

sary evictions to be accomplished with a mini

9

mum of delay and expense upon the giving

of a statutory Notice To Quit.5

(2) Contain no provision absolving the Local Au

thority from liability for its own negligence.

(3) If Local Authority policy provides for charges

for utility consumption in excess of specified

amounts, contain a provision obligating the

tenant to pay amounts assessed by the Local

Authority for overconsumption of utilities.

Of course, as we have shown in part I, supra, the federal

administrative policies upon which respondent relies have

now been superseded by new and more enlightened policies

which, far from condoning a refusal to disclose the grounds

of an eviction notice, compel disclosure and a fair oppor

tunity to reply. But, in any event, the former federal

policy invoked by respondent, and which was in effect at

the time of the notice to vacate in this case, displays in

its language, and its history, the clearest example of po

tential and purpose for abuse, and gives compelling force

to petitioner’s constitutional claims.

The recommendation was first made to local housing

authorities in a Public Housing Administration circular

dated July 28, 1954, which is reproduced in the appendix,

infra, p. la. The circular states that it was issued in

response to the ruling of the Municipal Court of Appeals

for the District of Columbia in Rudder v. United States,

105 A.2d 741 (D.C. Mun. App. 1954), subsequently reversed

226 F.2d 51 (D.C. Cir. 1955). Rudder involved a constitu

5 Note the difference between the wording of 6 .d (l) above and the

language quoted in the Authority’s brief which contains the words “with

out stating reasons for such notice” at the end of the second sentence.

It may be that the Authority’s brief quotes an earlier edition of the

Handbook.

1 0

tional challenge to the so-called Gw inn Amendment, tempo

rary legislation which formerly barred subversives from

occupying public housing units.6 The Municipal Court of

Appeals held in Rudder that since the local agency invoked

the Gwinn Amendment provision in its lease to evict the

tenants, the tenants could defend the eviction on the ground

that the eviction was unlawful by attacking the constitu

tionality of the Gwinn Amendment. The court sustained

the eviction by holding the Gwinn Amendment valid. The

July 28, 1954, circular (appendix, infra, p. la) was issued

in response to this decision and before the District of

Columbia Circuit reversed the eviction order. The circu

lar summarized the Rudder litigation and said that the

agency could have terminated the monthly tenancy by serv

ing a statutory notice to evict without revealing its rea

sons, but had erred by assigning a specific reason that

could be challenged as unconstitutional. The circular con

cluded :

In light of this decision it is suggested that all exist

ing tenant lease forms be reviewed to determine

whether there are contained therein any provisions

which might be interpreted by a Court as being con

trary to a simple monthly tenancy, thus precluding

tenancy being terminated by merely giving the statu

tory Notice to Quit. It is also suggested that all future

Notices to Quit cite only the provision of the lease

which permits termination within a specified time with

out reference to any other provision.

6 The Gwinn Amendment was former section 1411(c) of Title 42 of the

U. S. Code. The provisions were contained in three appropriations acts.

See Act, Aug. 31, 1951, c. 376, Title I, § 101, 65 Stat. 277; Act July 5,

1952, c. 578, Title I, § 101, 66 Stat. 403; Act July 31, 1953, c. 302, Title I,

% 101, 67 Stat. 307. The Attorney General ruled that the Gwinn Amend

ment was temporary legislation which has expired. 41 Ops. Att’y. Gen.,

April 26. Note, however, that the lease in the instant case still contains

an anti-subversive provision (R. 17).

1 1

Thus the Federal Government originally urged the local

housing authorities to terminate without giving reasons

for the specific purpose of enabling them to evict people

for reasons that might he challenged as without factual

basis or as violative of federal constitutional rights—in

the Rudder case, rights protected by the First Amendment

—by evicting only under a provision that did not require

giving a reason for the action. Thus the government in

1954 encouraged precisely the kind of misuse of a termi

nation provision that petitioner challenges here; that is,

the housing authority concealing a possibly unconstitutional

motive behind an eviction for which no reason need be

given.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Charles Stephen R alston

Charles H. J ones, J r.

Michael Meltsner

Sheila R ush J ones

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

R. Michael F rank

1238A Carrollburg Place S.W.

Washington, D. C.

M. C. B urt

213% West Main Street

Durham, North Carolina

A nthony G. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pa. 19104

Attorneys for Petitioner

Of Counsel:

Martin Garbus

E dward V. Sparer

H oward T horkelson

APPENDIX

H O U G I N G A N D H O M E F I N A N C E A G E N C Y W A S H I N G T O N 25, D. C .

CIRCULAR

■ 7-28-5U

TO} Local Authorities

Field Office Directors

SUBJECT: Decision in Rudder v, US of A and Its Importance Re Tenant

Lease Forms

The decisicfo made in the case of John Rudder andDoris Rudder, Appellants,

v * United States of America, Appellee*! NoTl)i29~ in “the Fnnicipal Court of

Appeals for the District of Columbia, on June 9, 195U, is one which should

be of interest to all local Authorities as it affects the issuance of

Notices To Vacate and the right to evict any tenant, either in the Lanham

Act or the low-rent propram.

The questions at issue were whether the l!„S. Government (National. Capital

Housing Authority) is required to reveal its reason for seeking to termi

nate tenancy and whether, if a reason were given, the tenant had the right

to defend on the ground that the reason given was improper or unlawful.

The Appellate Court stated that the Government, like any private landlord,

has the right to terminate a monthly tenancy by serving a statutory Notice

To Quit without revealing the reason therefor, providing, that such action

is in accord with the existing lease agreement with the tenant. Although,

in this case, the lease agreement did provide for termination upon 30- days’

notice, the Housing Authority included in the lease a provision that it

could bo terminated for any one of eight listed reasons. The Appellate

Court held that the Government in citing one such reason j_n its Notice To

Quit was in effect saying that eviction woulu b., sought only for one or

more of these eight stated reasons. It therefore hold that the Trial Court

should have, entertained the defense of the tenant. However, because of

another more compelling consideration the Appellate Court did not reverse

the decision of the Trial Court,

In light of this decision it is suggested that all existing tenant lease

forms be reviewed to determine whether there are contained therein any

provisions which might, be interpreted by a Court as being contrary to a

simple monthly tenancy, thus precluding tenancy being terminated by merely

giving the statutory Notice To Quit, It Is also suggested that all future

Notices To Quit cite only the provision of the lease vliich permits termi

nation within a specified time without reference to any other provision.

A ~ e .

A c wing Commi s slo nor

la

APPENDIX

2a

(See Opposite) EST

DEPARTMENT OF HOUSING AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT

PUBLIC HOUSING ADMINISTRATION

5

W A S H IN G T O N 13, C . 204«S

CIRC UTAH.

5-31-66

TO: Local Authorities

Regional Directors

Central Office Division and Branch Heads

FROM s Commissioner

SDEJECT:; Terminations of tenancy in low-rent projects

The Public Housing Administration has for a number of years recommended

that tenant leases be drawn on a month-to-month basis noting that this

practice should permit any necessary evictions to be accomplished upon

the giving of a notice to vacate# There is as you may be aware growing

opposition and challenge from individuals and organisations to the prac

tice of simply giving the statutory notice without stating the reason or

reasons therefor®

In connection with the above practice, we strongly urge, as a matter of

good social policy, that Local Authorities in a private conference inform

ary tenants who are given such notices of the reasons for this action.

Also, not all Local Authorities have kept their tenant lease forms current

with the result that, in some cases, obsolete and unenforceable lease

conditions are being challenged legally. We urge that all Local Authorities

review their lease forms and remove any such conditions. Regional Offices

will provide advice and assistance in connection with such reviews as may

be desired.

Commissioner

3a

4a

(See Opposite) SS?"

DEPARTMENT OF HOUSING AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT

WASHINGTON, D. C. 20410

O F F I C E O F T H E A S S I S T A N T S E C R E T A R Y

F OR R E N E W A L AND HOUSING AS S I ST A N C E

CIRCULAR

2-7 -6?

TO: Local Housing Authorities

Assistant Regional Administrators for Housing Assistance

HAA Division and Branch Heads

FROM: Don Hummel

SUBJECT: Terminations of Tenancy in Lew-Rent Projects

Within the past year increasing dissatisfaction has been expressed with

eviction practices in public low-rent housing projects. During that period

a number of suits have been filed throughout the United States generally

challenging the right of a Local Authority to evict a tenant without advising

him of the reasons for such eviction.

Since this is a federally assisted program, we believe it is essential that

no tenant be given notice to vacate without being told by the Local Authority,

in a private conference or other appropriate manner, the reasons for the

eviction, and given an opportunity to make such reply or explanation as he may

wish.

In addition to informing the tenant of the reason(s) for any proposed eviction

action, from this date each Local Authority shall maintain a written record of

every eviction from its federally assisted public housing. Such records are to

be available for review from time to time by HUD representatives and shall con

tain the following information:

1, Name of tenant and identification of unit occupied®

2, Date of notice to vacate,

3, Specific reason(s) for notice to vacate. For example, if a tenant

is being evicted because of undesirable actions, the record should

detail the actions which resulted in the determination that eviction

should be instituted.

(Cont*d)

5a

(See Opposite)

2

iu Date and method of notifying tenant with summary of any conferences

with tenant, including names of conference participants®

5. Date and description of final action taken®

The Circular on the above subject from the PHA. Commissioner, dated May 31,

1966, is superseded by this Circular®

Assistant Secretary for Renewal

and Housing Assistance

7a

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y.