Petition for Rehearing and Suggestion of Appropriateness of Rehearing En Banc with Cover Letter

Public Court Documents

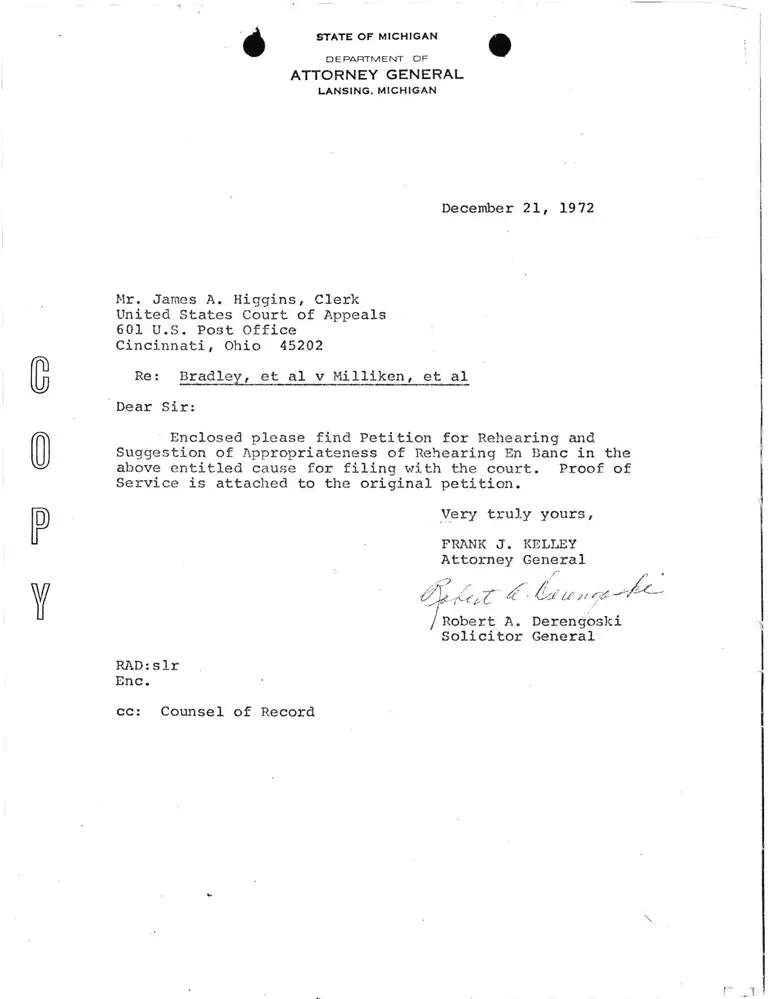

December 21, 1972

17 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Petition for Rehearing and Suggestion of Appropriateness of Rehearing En Banc with Cover Letter, 1972. 49be28b2-53e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1f6fac46-36b9-429b-a526-0d07ea7d92cf/petition-for-rehearing-and-suggestion-of-appropriateness-of-rehearing-en-banc-with-cover-letter. Accessed February 27, 2026.

Copied!

4 S T A T E O F M IC H IG A N

D E P A R T M E N T O F

A T T O R N E Y G E N E R A L

LA N S IN G . M ICH IG AN

December 21, 1972

Mr. James A. Higgins, Clerk

United States Court of Appeals

601 U.S. Post Office

Cincinnati, Ohio 45202

Re: Bradley, et al v Milliken, et al

Dear Sir:

Enclosed please find Petition for Rehearing and

Suggestion of Appropriateness of Rehearing En Banc in the

above entitled cause for filing with the court. Proof of

Service is attached to the original petition.

Very truly yours

FRANK J. KELLEY

Attorney General

Robert A. Derengoski

Solicitor General

RAD:sir

Enc.

cc: Counsel of Record

Nos. 72-1809 - 72-1814

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

RONALD BRADLEY, et al,

v Plaintiffs-Appellees,

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, Governor of Michigan,

etc.; BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE CITY OF

DETROIT, Defendants-Appe Hants,

and

DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS LOCAL 231,

AMERICAN FEDERATION OF TEACHERS, AFL-CIO

Defendant-Intervenor-Appellee,

and

ALLEN PARK PUBLIC SCHOOLS, et al.,

Defendants-Intervenors-AppeHants,

and

KERRY GREEN, et al.,

Defendants-Intervenors-Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Michigan, Southern Division

PETITION FOR REHEARING AND SUGGESTION OF

APPROPRIATENESS OF REHEARING EN BANC

Business Address:

720 Law Building

525 West Ottawa Street

Lansing, Michigan 48913

FRANK J. KELLEY

Attorney General

I

Robert A. Derengoski

Solicitor General

Eugene Krasicky

Gerald F. Young

George L. McCargar Assistant Attorneys General

Attorneys for Petitioners

Nos. 72-1809 - 72-1814

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

For the Sixth Circuit

RONALD BRADLEY, et al,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

v

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, Governor of Michigan,

etc.; BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE CITY OF

DETROIT, Defendants-Appellants,

and

DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS LOCAL 231,

AMERICAN FEDERATION OF TEACHERS, AFL-CIO,

Defendant-Intervenor-Appellee,

and

ALLEN PARK PUBLIC SCHOOLS, et al.,

Defendants-Intervenors-Appellants,

and

KERRY GREEN, et al.,

Defendants-Intervenors-Appellees.

/

To: Honorable Judges of Said Court

PETITION FOR REHEARING AND SUGGESTION

OF APPROPRIATENESS OF REHEARING EN BANC

Petitioners, William G. Milliken, Governor of the

State of Michigan; Frank J. Kelley, Attorney General of the

State of Michigan; John W. Porter, Superintendent of Public

Instruction for the State of Michigan; the State Board of

Education for the State of Michigan, and Allison Green,

Treasurer of the State of Michigan (hereinafter, collectively,

called petitioners), by their undersigned counsel, respect

fully request that pursuant to F.R.A.P. 40 and 35(a), this

Court grant rehearing en banc of the December 8, 1972

decisions in these causes by a Panel of this Court consisting

of the Honorable Harry Phillips, Chief Judge, the Honorable

George Edwards and the Honorable John W. Peck, Circuit Judges,

as erroneous and in conflict with decisions of other panels

of this Court.

I.

FINDINGS OF FACT AND CONCLUSIONS OF LAW

WITH REGARD TO THE GOVERNOR AND THE

ATTORNEY GENERAL ARE CLEARLY ERRONEOUS

The panel began its opinion as follows:

"This is a school desegregation case involving

the metropolitan area of Detroit, Michigan."

It should be noted that the case was commenced as a school

desegregation case and tried as a school desegregation case

involving bnly the Detroit public schools, a school district

and body corporate under the laws of the State of Michigan

and boundaries of which are coterminous with the City of Detroit,

and that the fundamental issue heard and determined was whether

the Detroit public school district was a de jure segregated

system. Brown v Board of Education, 347 US 483 (1954). Thê

complaint was filed on August 19, 1970 and was neither amended

-2

nor supplemented. The fundamental issue, therefore, had

to be determined in light of events as they existed at that

time. FR Civ P 7 and 15.

While both the trial court and the Panel of this Court

considered and decided the matter as a suit against the State

of Michigan, it is elementary that a sovereign state may not

be sued without its consent in a federal court. US Const

AM XI. See pp 49, 50 and 64 of the opinion of the Panel.

In re State of New York, 256 US 490, 497 (1921). No such

consent was ever given and the State of Michigan is not a

party to this suit.

It is equally elementary that the proscription of the

equal protection clause of US Const, Am XIV applies to the

states, and not to an individual. "No state shall . . . deny

to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of

the law." See discussion in Burton v Wilmington Parking

Authority, 365 US 715 (1961).

The dilemma is that the equal protection clause of

US Const, Am XIV operates as a proscription only against the

state, but US Const, Am XI prohibits suits against the states

and, thus, on its face, renders the equal protection clause of

US Const, Am XIV unenforceable in the courts against the entity

upon which it operates. The answer, of course, is to clothe

an individual or a governmental agency with the authority of

the state.

-3-

"The applicable principle is that where state

officials, purporting to act under state authority,

invade the rights secured by the Federal Con

stitution, they are subject to the process of

the federal courts in order that the^persons

injured may have appropriate relief."

Sterling v Constantin, 387 US 378, 393 (1932).

More recently, the Supreme Court said:

"It is contended that the case is an action

against the State, is forbidden by the Eleventh

Amendment, and therefore should be dismissed.

The complaint, however, charged that state and

county officials were depriving petitioner of

rights guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment.

It has been settled law since Ex Parte Young,

(citation) that suits against state and county

officials to enjoin them from invading consti

tutional rights are not forbidden by the Eleventh

Amendment." Griffin v County School Board of

Prince Edward County, 377 US 218, 228 (1964).

The same concept was written into the civil rights

act of 1964. 42 USC 1983 says:

"Every person, who under color of any statute,

ordinance, regulation, custom or usage, of any

State or territory, . . . " (Emphasis supplied)

The controlling principle is that individuals are

clothed with the authority of the state - are found to be acting

under the color of state law - so that their acts may be reached

under US Const, AM XIV and the provisions of the 1964 civil

rights act. The state is not reached through the individual.

In its ruling on issue of segregation (la 210), the

trial court determined "the principles essential to a finding

of de jure segregation, as outlined in rulings of the United

States Supreme Court to be:

-4-

"1. The State, through its officers and agencies,

and usually the school administration, must have

taken some action or actions for the purpose of

segregation.

"2. This action or these actions must have

created or aggravated segregation in the

schools in question.

"3. A current condition of segregation exists.

II• • •

Without doubt these are the essential principles, except

the statement, "[t]he State, through its officers and agencies"

could be construed as imposing a vicarious liability upon a state,

contrary to the provisions of US Const, AM XI. Therefore, this

phrase, to avoid confusion and a misapplication of constitutional

principles should have read, "officers and agencies acting under

the color of state law," or "officers and agencies clothed with

the authority of state law."

In passing upon the actions of the Governor and the

Attorney General, it may hardly be argued that either the Governor

or the Attorney General shed any of their federally protected

constitutional rights at the state capitol door. See Tinker v

Des Moines Independent School District, 393 US 503, 506 (1968).

Like every other citizen their actions should be judged fairly

by the record and in accordance with due process of law.

Neither the trial court nor the Panel made any specific

findings of misconduct against the Governor and the Attorney

General, as indeed on the record, they could not. Also, no

findings were made that they were necessary parties for relief.

-5-

It must be concluded that the action of the Panel in

affirming the decision against the Governor and the Attorney

General must be based upon vicarious liability. Such rulings

are clearly erroneous.

In its opinion at page 62 the Panel of the Court ruled

that the Governor and the Superintendent of Public Instruction

helped to merge the Carver district with Oak Park. Neither the

Governor nor the Superintendent of Public Instruction merged the

Carver District with Oak Park since the Oakland Intermediate

School District ordered the merger as authorized by the legislature

pursuant to the provisions of MCLA 340.3; MSA 15.3003. Further,

there is no evidence on the record in this cause that this merger

was for the purpose of and created or aggravated segregation in

the Detroit public schools. The testimony of Dr. Green is that

after the merger the Carver children were doing very well in a

unitary school system. (Transcript 939-40) ,

II.

FINDINGS OF FACT AND CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AS TO

SUPERINTENDENT OF PUBLIC INSTRUCTION AND THE

STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION ARE CLEARLY ERRONEOUS.

On the record in this case, three specific acts alleged

against these petitioners are: that the State Board of Education

entered into a joint policy statement with the Civil Rights

Commission (plaintiffs' exhibit 174, IX a 281); that the State

Board of Education published a school plant planning handbook

(la 203) quoted in the trial court's opinion as follows:

6-

f

I

"Care in site selection must be taken if a

serious transportation problem exists or if

housing patterns in an area would result in

a school largely segregated on racial, ethnic,

or socio-economic lines."; and

that the Superintendent of Public Instruction failed to use the

power over site selection that he had prior to 1962.

It is untenable to argue that the State Board of

Education's joining in the joint policy statement was an act

taken for the purpose of segregation or that it created or

aggravated segregation. From the standpoint of the State Board

of Education, the joint policy statement was a recammendarion.

(Testimony of Dr. Porter, Ilia 99-101). If it conferred rights

on appellee-plaintiffs, the rights arose under the laws of the

State of Michigan, not under the Constitution of the United States,

because state laws do not create federal constitutional rights.

Baker v Carr, 369 US 186, pp 194-195 Fn 15 (1962). Calder v

Bull, 3 Dali 386, 1 L Ed 648 (1798) . Gentry, v Howard, 288

F supp 495 (ED Tenn, 1969). Further, the power to enforce

Michigan law in this area is vested in the Civil Rights Commission,

not a party to this action, and not in petitioners. Const 1963,

art 5, § 29.

During the period 1949 to 1962 the Superintendent of

Public Instruction had the power to approve schoolhouse sites.

1949 PA 231. By MCLA 388.1014; MSA 15.1023(14) certain powers

of the Superintendent of Public Instruction were vested in the

State Board of Education, but the site selection approval was

-7-

removed from the Superintendent of Public Instruction prior

to this vesting. 1962 PA 175. The State Board of Education

never was given authority by the legislature to approve school

sites. Thus, the Court is clearly in error. The incidents of

site selection relied upon by the Panel of this Court and the

trial court in their conclusions of de jure segregation in the

Detroit public schools occurred after the effective date of

1962 PA 175. The assertion that the selection of sites within

the Detroit school district was a purposeful act of the State

Board of Education and the Superintendent of Public Instruction

when neither of them had any control over site selection nor

sought to exercise any control (they never selected any of the

controversial sites) is not only erroneous but indefensible.

Again, it defies reality to suggest that a statement

in the School Construction Handbook to use care in site selection

if housing patterns in an area would result in a school largely

segregated on racial, ethnic, or socio-economic lines, was an

act taken with a purpose of segregation or was an act which

created or aggravated segregation.

III.

MATTERS OF BONDING, TRANSPORTATION AND FINANCE

These were considered by the Panel (p 41 of opinion)

under the heading "(B) The constitutional violation found to

have been committed by the State of Michigan." First, the

State of Michigan is not a party to this lawsuit. See Argument I.

-8-

The Panel's first point was school construction. This

was discussed above and will be briefly here. MCLA 340.961;

MSA 15.1961 for the approval of construction plans by the State

Board of Education is directed to safety and health factors.

The Superintendent of Public Instruction's power to supervise

location of sites was repealed in 1962, prior to any of the

evidence against the Detroit Board of Education with reference

to site selection. There was no showing that the State Board

of Education's approval of the Detroit school district's con

struction plans as to health and safety was an act taken with

a purpose of segregation.

The second point made by the Panel was that Detroit

was discriminated against in its bonding authority. These figures

cited by the panel are in error. Prior to 1969 the bonding

authority of first, second and third class districts was 2%.

1965 PA 28, 1962 PA 177 and 1955 PA 269, § 115. The limitation

was raised to 3% in first class districts and 5% in all other

districts, by 1968 PA 316 and increased to 5% in first class

districts by 1971 PA 23. The record does not show that the

bonding limitations were imposed for the purpose of segregation

or that they created or aggravated segregation. (pp 41, 42 of

Opinion) It is undisputed that the Detroit Board of Education

never exhausted the bonding limitations. Even assuming arguendo

that the percentage bonding limitations were discriminatory, they

were not racially discriminatory because they affected all children

regardless of race.

-9-

The third point made by the Panel was that the school

district of Detroit was denied any allocation of state funds for

transportation, although such funds were available for students

living over a mile and one-half from their assigned school in

rural areas, and some suburban districts received such funds

under an alleged "grandfather clause." The Panel refers to

"SB 1269, Reg Session 671(2)(a)(b)(1972)." First, "S.B. 1269"

is not a part of the record of this litigation, although it is

< ! in the Appendix (IXa 617). The record is barren that any

suburban district involved in the metropolitan area is a

"grandfather" beneficiary.

The second misapprehension is that the statutory dis

tinction between city and rural was for the purpose of segregation

and that it created or aggravated segregation. There is no

evidence in this record to so show. The act affects all urban

school districts in the same manner. This has been determined

to be a reasonable classification, Sparrow v Gill, 304 F Supp 86

(MD NC, 1969), and in any event, it is not racially discriminatory.

Assuming arguendo what the Panel is saying is true

relative to bonding, financing^ construction and transportation,

the Carver school district, and even 1970 PA 48, § 12, based on the

record, none of these actions had the effect of creating and main

taining racial segregation along school district lines. Thus

the ruling of the Panel on page 65 of its opinion is totally

unwarranted. Moreover, with the exception of Dr. Porter's

testimony as to transportation, all the proofs as to bonding.

-10-

finance, construction, and other proofs as to transportation

were admitted into evidence after your petitioners made motions

to dismiss pursuant to FR Civ P, 41(b), and petitioners rested.

To consider evidence introduced after they rested is clearly j

error. A. & N. Club v Great American Insurance Co, 404 F 2d

100, 103-104 (CA 6, 1968).

IV.

THE MANDATE FOR A METROPOLITAN REMEDY

Plaintiffs complained and tried their case on the

theory that the Detroit public schools was a segregated school

district and without reference to any other school district.

Yet, based upon one factual finding, the trial court not only

gave plaintiff a new cause of action, but also decided this cause

of action in plaintiffs' favor without giving any of the allegedly

discriminating school districts the opportunity to be heard.

The Panel has erroneously affirmed the order of the

trial court that relief of segregation in the public schools of

the City of Detroit cannot be accomplished within the Detroit

school district. The sole fact in support of this conclusion

was that the student population was predominately black. See

Panel's opinion, pp 52, 53.

The trial court's sole factual findings, affirmed by

this Court, reinforces the position of petitioners: (1) The

Detroit school district is not a de jure segregated district but

is a school district with a predominately black student population

(2) that this condition is not a denial of equal protection under

-11-

US Const, Am XIV, Swann v Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 US 1 (1971), Wright v Council of City of Emporia, 407 US 451

(1972), United States v Scotland Neck Board of Education, 407

US 484 (1972), and (3) that this condition was not caused by

the purposeful acts of the defendants, especially the acts of

petitioners. None of the three conditions precedent to a finding

of de jure segregation have been met. Yet, by resort to the

theory of vicarious liability, the Panel affirms a metropolitan

remedy without providing affected neighboring school districts

their day in court.

The first cross district desegregation plan was ordered

by Judge Merhige in Bradley v School Board of City of Richmond,

Virginia, 338 F Supp 67 (1972), rev'd 462 F 2d 1058 (1972),

based upon a finding of purposeful establishment and maintenance

of school district boundaries with intent to segregate after

notice and nearing to the affected school districts. There is

no finding here that school district boundary lines were created

and maintained for the purpose of segregation.

In this connection it should be noted that Haney v

County Board of Education of Sevier County, 429 F 2d 364 (CA8,

1970), cited by this Court at p 56 of its opinion, contained a

specific finding that the boundary lines were created and maintained

for the purpose of enhancing the segregation of the schools

required by state law in that case.

Another example of the application by the Panel of

the vicarious liability principle is:

-12-

"Thus, the record establishes that the State

has committed de jure acts of segregation and

that the State controls the instrumentalities

whose action is necessary to remedy the harmful

effects of State acts. . . (p 64 of Opinion)

The state is not a party to this action and further,

is immune from suit. Second, assuming arguendo that officers

or agencies, clothed with the authority of the state did act

unconstitutionally, this does not mean that their acts may be

attributed to other individuals and agencies, clothed with the

authority of the state and not before the court. Another example

of the vicarious liability reasoning is:

"If we hold that school district boundaries are

absolute barriers to a Detroit school desegregation

plan, we would be opening a way to nullify Brown

v Board of Education, which overruled Plessy,

supra." (p 65 of Opinion)

The law is that school boundaries which were not created

and maintained for the purpose of segregation are not a violation

of the United States Constitution and, therefore, the courts have

no jurisdiction to interfere. Spencer v Kugler, 326 F Supp 1235

(D NJ, 1971), aff'd 404 US 1027 (1972). On this record, by the

express admissions of the trial court, there is not a single

finding that school district boundaries were created and maintained

for the purpose of school segregation.

At p 66 of the opinion, the Panel states that there is a

vested constitutional right to a metropolitan remedy in this case,

and this is the same as saying that there is a vested constitutional

right to a particular ratio of black to white in a school district.

This concept was rejected by the Supreme Court on numerous occasions.

13

Swann, supra; Spencer v Kugler, supra; Wright v Council of

Emporia, supra; Cotton v Scotland Neck, supra. It is also

contrary to Deal v Cincinnati Board of Education, 369 F 2d 55

(CA 6, 1966) , cert den 389 US 847 (1967) , Deal v Cincinnati

Board of Education, 419 F 2d 1387 (CA 6, 1969), cert den 402

US 962 (1971), and Mapp v Board of Education of the City of

Chattanooga, __ F 2d ___ (CA 6, 1972), slip opinion October 11,

1972, rehearing granted November 29, 1972.

This analysis demonstrates the grievous misapprehension

of not only the facts, but also of the applicable principles of

constitutional law enunciated by the Supreme Court and by this

Circuit.

SUGGESTION OF APPROPRIATENESS OF A REHEARING EN BANC

The decision of the Panel is unquestionably unique,

unprecedented and, for the reasons set forth, erroneous. It

rests upon a rationale clearly inconsistent with Deal, supra,

and Mapp, supra. These inconsistencies must be reconciled and

harmonized.

Petitioners note the granting of a petition for

rehearing en banc in the case now pending before this Court of

Mapp v Board of Education, supra. That case, undoubtedly, raises

important questions, but they do not compare with either the

unprecedented nature or the importance of the questions presented

herein. This case merits equal rehearing en banc.

-14-

RELIEF

WHEREFORE, Petitioners respectfully pray this

Honorable Court to grant them an en banc rehearing of the

decision filed by a panel of this Court on December 8, 1972.

FRANK J. KELLEY

Robert A. Deren_

Attorney Genera

Solicitor General

Eugene Krasicky

Gerald F. Young

George L. McCargar

Lawrence G. WardAssistant Attorneys General

Attorneys for Petitioners-Defendants

Business Address:

720 Law Building

525 West Ottawa Street

Lansing, Michigan 48913

Dated: December 21, 1972