Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 9, 1975

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education Brief for Appellants, 1975. 984eb1f8-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1fab66d0-734c-4d56-9564-bf8bc708743e/wheeler-v-durham-city-board-of-education-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

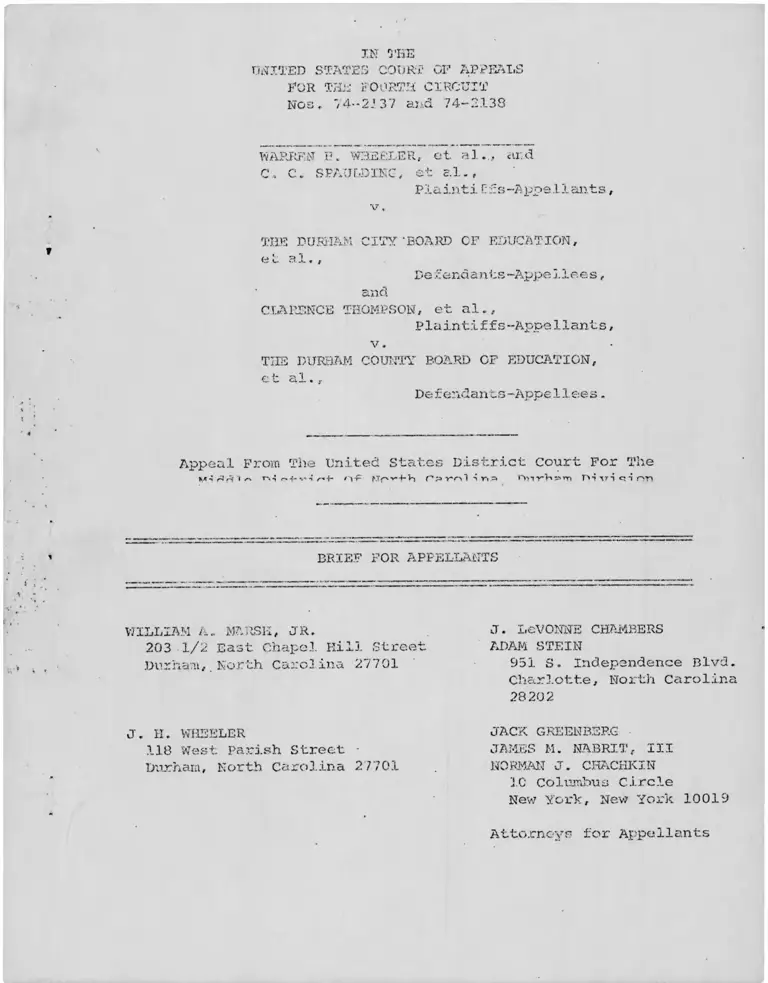

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 74~2237 and 74-2.133

WARREN H. WHEELER, ot. al<iK.d

C.. C. SPAULDING, et 8.1.,

Piainti Ofs-Appellants,

THE DURHAM CITY'BOARD OF EDUCATION,

O L- 3.1 * ,

D e f enda nts-Appe j. 1ee s,

and

CLARENCE THOMPSON, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appe11ant s,

v .

THE DURHAM COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION,

et ai.,

De fondants-Appe11ees.

Appeal From The United States District court For The

M o r * r i '» ^ n-lcfv'ir'-l- H & Y ' r y l o r i =» P i ' i r i q i o n

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

WILLIAM A. MARSH, JR.

203 1/2 East. Chapel Kill Street

Durham,. North Carolina 27701

J. LeVONNE CHAMBERS

ADAM STEIN

951 S. Independence Blvd

Charlotte, North Cardin

28202

J. H . WHEELER

118 West Parish Street -

Durham, North Carolina 27701

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NA.BRIT, III

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

1C Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Table of Authorities . . ii

Issues Presented for Review.......... ........... la

Statement of the Case ........................... 2

Statement of Facts

1. Durham City Schools ..................... 8

2. Durham County Schools and Public

Housing and Relocation .................. 12

3. Plaintiffs' Proposed Plans of

Desegregation ........................... 16

4. The 1974-75 Plans Submitted By

The Boards .............................. 17

ARGUMENT —

I The District Court Should Have Ordered

Complete Desegregation Of The Durham

City School System .................... 21

II The Durham County Board's 1974-75 Pupil

Assignment Plan Unconstitutionally

Places A Disproportionate Burden Upon

Black Students ........................ 27

III The District Court Should Have Granted

Injunctive Relief To Halt Practices Of

City Agencies Which Thwarted Effectu

ation Of Desegregation In Durham...... 30

Conclusion ...................................... 34

Certificate of Service .......................... 36

Page

Table of Authorities

Cases:

Adams v. Rankin County Bd. of Educ., 485 F.2d

324 (5th Cir. 1973) ........................ 26

Adams v. School Dist. No. 5, Orangeburg, 444

F.2d 99 (4th Cir. 1971), cert, denied sub.

nom. Winston-Salem/Forsyth County Bd. of

Educ. v. Scott, 404 U.S. 912 (1971) ..... . 23n, 26, 27

Alexander v. Holmes County Bd. of Educ., 396

U.S. 19 (1969) ................ ............. 12

Arvizu v. Waco Independent School Dist., 495

F . 2d 499 (5th Cir. 1974) ................... 28

Boyd v. Pointe Coupee Parish School Bd., No. 71-

3305 (5th Cir., Dec. 10, 1974), rev1g 332

F. Supp. 994 (E.D. La. 1971). ............... 24

Boykins v. Fairfield Bd. of Educ., 457 F.2d I0yl

(5th Cir. 1972) ..................... ....... 24, 25

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 51 F.R.D. 139

(E.D. Va. 1970) 34

Brewer v. School Bd. of Norfolk, 397 F.2d 37

(4th Cir. 1968) 31

Brice v. Landis, 314 F. Supp. 974 (N..D. Cal. 1969) 28

City of Kenosha v. Bruno, 412 U.S. 507 (1973) .... 5n

Clark v. Board of Educ. of Little Rock, 449 F.2d

493 (8th Cir. 1971), cert, denied, 405 U.S.

936 (1972) .................................. 28

Crow v. Brown, 332 F. Supp. 283 (N.D. Ga. 1971),

aff'd 457 F.2d 788 (5th Cir. 1972) ....... . 31

Dowell v. Board of Educ. of Oklahoma City, 465

F.2d 1012 (10th Cir.), cert, denied, 409

U.S. 1041 (1972) 24

Page

xi

Table of Authorities (continued)

Page

Ellis v. Board of Public Instruction, 465 F.2d

878 (5th Cir. 1972) .....................••** 24

Flax v. Potts, 464 F.2d 865 (5th Cir.), cert.

denied, 409 U.S. 1007 (1972)................. 24

Goss v. Board of Educ. of Knoxville, 444 F.2d

632 (6th Cir. 1971) ................ -....... 23n

Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent County,

391 U.S. 430 (1968) ........................ 3' 9' 23

Green v. School Bd. of Roanoke, 316 F. Supp. 6

(W.D. Va. 1970), aff'd sub nom. Adams v.

School Dist. No. 5, Orangeburg, 444 F.2d 99

(4th Cir. 1971), cert, denied sub nom.

Winston-Salem/Forsyth County Bd. of Educ. v.

Scott, 404 U.S. 912 (1971) .................. 28

Harrington v. Colquitt County Bd. or Educ., 4-t>u

F.2d 193 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 409

U.S. 915 (1972) .................. . ......... 21' 28

Hart v. County School Bd. of Arlington County,

459 F.2d 981 (4th Cir. 1972) ............... 27-28

Hobsen v. Hansen, 269 F. Supp. 401,(D.D.C. 196/),

aff'd sub nom. Smuck v. Hobson, 405 F.2d 175

(D.C. Cir. 1969) ...................... ..... 33

Hereford v. Huntsville Bd. of Educ., 504 F«2d

857 (5th Cir. 1974) ........................ 24

Kelley v. Metropolitan County Bd. of Educ., 463

F.2d 732 (6th Cir.), cert, denied, 409 U.S.

1001 (1972) ................. ;.............* 24

Kelly v. Guinn, 456 F.2d 100 (9th Cir. 1972),

cert, denied, 413 U.S..919 (1973) .......... 25n

Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, Denver, 413 U.S.

189 (1973) ................................. 23n

iii

Table of Authorities (continued)

Page

Lee v. Macon County Bd. of Educ., 448 F.2d

746 (5th Cir. 1971) ........................ 28

Lemon v. Bossier Parish School Bd., 446 F.2d

911, 444 F.2d 1400 (5th Cir. 1971) ......... 23

McFerren v. County Bd. of Educ., 497 F.2d 924

(6th Cir. 1974) 28

Medley v. School Bd. of Danville, 482 F.2d 1061

(4th Cir. 1973), cert, denied, 414 U.S.

1172 (1974) ....... ......................... 22, 25, 27

Milliken v. Bradley, 41 L.Ed.2d 1069 (1974) .... . 23n

Monroe v. Board of Comirt'rs of Jackson, 391 U.S.

450 (1968) ..................... ............ .9

Monroe v. County Bd. of Educ., 505 F.2d 109

(6 Lh Cxi . j ) ............... ................ x--xr

Nesbit v. Statesville City Bd. of Educ., 418

F. 2d 1040 (4th Cir. 1969) ..... ............. 12

Northcross v. Board of Educ. of Memphis, 466

F.2d 890 (6th Cir. 1972), cert, denied, 410

U.S. 926 (1973), vacated and remanded on

other grounds, 412 U.S. 42 7 (1973) ......... 2 5

Pate v. Dade County School Bd., 434 F.2d 1151

(5th Cir. 1970) ............................. 27

Raney v. Board of Educ. of Gould, 391 U.S. 443

(1968) ...................................... 9

Robinson v. Shelby County Bd. of Educ., 467 F.2d

1187 (6th Cir. 1972) 28

Sloan v. Tenth School Dist. of Wilson County,

433 F.2d 587 (6th Cir. 1970) ............... 31

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ.,

402 U.S. 1 (1971) .......................... 22, 24, 25, 31

IV

Table of Authorities (continued)

Pa^e

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ.,

431 F.2d 138 (4th Cir. 1970), rev'd in

part, 402 U.S. 1 (1971) .................... 22

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ.,

Civ. No. 1974 (W.D.N.C., August 7, 1970),

aff'd 402 U.S. 1 (1971) ............ ........ 29-30

Weaver v. Board of Public Instruction, 467 F.2d

473 (5th Cir. 1972), cert, denied, 410 U.S.

982 (1973) ...................... ........... 25

Wheeler v. Durham City Bd. of Educ., 363 F.2d 738

(4th Cir. 1966) ...................... ...... 3n

Wheeler v. Durham City Bd. of Educ., 196 F. Supp.

71 (M.D.N.C. 1961) .......... ............... 3n

Statutes:

20 U.S.C.A. §1653 (1974) 31

42 U.S.C.A. §2000d (1974) 31

Rules

F.R.C.P. 19 ............................... 34

F.R.C.P. 21 ...................................... 34

v

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 74-2137, - 2138

WARREN H. WHEELER, et al.,

and

C. C. SPAULDING, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants

v.

DURHAM CITY BOARD OF EDUCATION,

et al.,

Defendants-Appellees,

and

CLARENCE THOMPSON, et al..

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

DURHAM COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION,

et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeals From The United States District Court For The

Middle District Of North Carolina, Durham Division

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Issues Presented For Review

1. Should the District Court have ordered further

desegregation of the Durham City schools rather than

holding that implementation of the 1970 plan made the

system unitary?

2. Should the District Court have rejected the

Durham County Board’s 1974-75 proposal for the elementary

schools on the ground that the conversion of Bragtown and

Lakeview to single-grade centers unfairly and dispro

portionately burdens black students?

3. Should the District Court have granted injunctive

relief against the City of Durham, and/or against city

agencies which could have been added as parties necessary

for relief, to prevent the future location of massive public

housing projects, relocation activities, or other official

action which would impede and undermine the success of its

desegregation orders?

la

Statement of the Case

These are appeals from orders entered by the district

court in these consolidated school desegregation cases

following a 1974 trial on plaintiffs' Motion for Further

Relief and Supplemental Complaint seeking consolidation,

cross-boundary assignments, or other form of interdistrict

relief between the Durham City and County school systems.

The District Court denied any form of interdistrict relief

(the instant appeals do not challenge that action) and also

denied plaintiffs' requests for alternative relief. Plaintiffs

p p u r r Vi -f- a ( "1 \ •Pivr+-V>rN v* — » 4— ! /-x -C 4-V « - r - \ ^ n J J— T' ' .. * • - ------w—•

schools — many of which had remained racially identifiable

and segregated despite the 15 years of litigation in the

Wheeler and Spaulding cases; (2) adoption of a fairer and

more equitable 1974-75 desegregation plan for the Durham

County elementary schools to replace the clustering plan pro

posed by the school authorities, which reduced two elementary

schools with predominantly black enrollments to single-grade

centers; and (3) injunctive relief against city agencies whose

practices, including the location of multi-family public

housing projects, had contributed significantly to the con

centration of black students in particular Durham City and

County schools, and which threatened in the future to destroy

2

the effectiveness of any desegregation decrees entered by the

district court against the school authorities. The District

Court granted no injunctive relief and accepted separate

city and county plans despite these claims of insufficiency and

unfairness.

The Durham City school desegregation cases (Wheeler and

1/Spaulding) were filed in I960, and were last before this

2/

Court in 1966, at which time the freedom-of-choice method

of pupil desegregation was endorsed. Thereafter, and following

the Supreme Court's decision in Green v. County School Board

of New Kent County. 391 U.S. 430 (1968), plaintiffs filed a

Motion for Further Relief which resulted, ultimately, in the

issuance of an Order on July 31, 1970 approving (as modified)

a new plan of pupil assignment, based upon geographic zoning

and the contiguous pairing of three sets of elementary schools

3/(A. 99,488). That plan projected school facility racial

1/ See Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education, 196 F. Supp.

71 (M.D.N.C. 1961).

2/ Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education, 363 F.2d 738

(4th Cir. 1966) .

3/ Citations are to the Appendix reproduced in connection with

this appeal, pursuant to agreement of counsel, a Supplemental

Appendix containing additional portions of the record will be

filed hereafter.

3

compositions ranging from 21% to 90 black, in the city

system which was then 60% black (A. 486$ .

When implementation of the plan failed to produce even

these results, the Durham City Board studied alternative

means of achieving greater desegregation, and discussed

possible plans with both plaintiffs' counsel and members

of the public (A. 65-66,209). However, the Board having failed

to act, plaintiffs on July 25, 1972 filed another Motion for

Further Relief in the city case, alleging that the 1970 decree

had not worked to create a unitary public school system in

Durham, that reaching this goal was made more difficult by the

fact that the city school district did not include the entire

geographic area of the city's political jurisdiction, and

requesting that the Court require the submission of a new plan

to include that entire area (A. 17-25-

Because such relief would affect the Durham County

district, which currently administers five schools located in

4/

the "city-out" area, plaintiffs on October 16, 1972, filed

a motion seeking leave, subsequently granted by the district

4/ The geographic area within the corporate limits of the City

of Durham, but outside the boundaries of the city school system.

"City-in" refers to the portion of Durham City within the city

school district.

4

court, to add the Durham County Board of Education and

Superintendent, as well as various State educational and

municipal officials, as parties defendant. At the Court's

direction, plaintiffs filed a Supplemental Complaint against

the original and added defendants on December 18, 1972; and

the Wheeler-Spaulding and Thompson cases were then consolidated

for purposes of trial on the issues raised by the Supplemental

5/

Complaint. Pre-trial motions to dismiss were denied, or

carried with the case, and discovery proceeded. Plaintiffs'

motion for interim injunctive relief against the Durham City

district defendants was denied by the district court on December

6, 1973 on the ground that mid-year implementation of a new

desegregation plan for the city schools

would create a disruptive and uncertain

atmosphere at a time when comprehensive

and drastic changes are being prayed for

in a supplemental complaint filed in these

consolidated actions on December 15, 1972.

5/ On June 11, 1974, plaintiffs filed a post-trial motion for

leave to amend their original and Supplemental Complaints to

eliminate potential jurisdictional problems which arose following

the Supreme Court's decision in City of Kenosha v. Bruno, 412 U.S.

507 (1973), by broadening the jurisdictional claims and adding

individual members of the various boards as defendants. This

motion was granted by Order of July 30, 1974 at the same time

as the merits of the main case were determined by the district

court (A. 470-78).

5

The busing remedy, as well as other measures,

approved in Swann, supra, has been utilized

to a significant extent in the Durham City

Administrative School Unit, and court-ordered

procedures to further desegregate the school

system, if to take effect during this school

year, would seriously impinge upon the

educational process without corresponding

benefits toward the establishment or per

petuation of a unitary school system. [Findings

of Fact and Conclusions of Law, issued December

6, 1973, pp. 14, 16]

The matter was tried before the Court in May, .1974 and decided

July 30, 1974.

Although the primary relief sought in the Supplemental

Complaint was inter-district assignment, of students between

the Durham city and county school systems, plaintiffs alter

natively prayed

that plans of desegregation for both

units be developed and implemented

which will provide for the assignment

of students by the two units in order

to eliminate the racial segregation and

racial identity of the schools and

school units of Durham County and Durham

City.

and for "such other, alternate or additional relief as the

Court may deem the plaintiffs entitled [to]." (A. 36 ).

Furthermore, in light of the substantial evidence developed

during discovery and presented at the trial concerning the

activities of city agencies (the Durham Housing Authority,

6

Redevelopment Commissdon, etc.) which impacted negatively

upon the creation and maintenance of unitary school systems

in both the city and county, plaintiffs' Proposed Findings

of Fact and Conclusions of Law submitted after the trial

requested an injunction requiring

that the City of Durham shall immediately

take such steps as may be necessary to

insure that none of the city agencies,

whether under the direct or indirect

control of the city, institute or

implement any policies or practices

which have the affect [she] of perpetuating

or resegregating the public schools of

Durham city and Durham county.

(Plaintiffs' Proposed Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law,

and Order, filed June 14, 1974, at p. 35). The Court's Order

of July 30, 1974, denied "[p]laintiffs' request for relief

contained in plaintiffs' supplemental complaint . . .,"

gave plaintiffs ten days within which to object to a Durham

County Board of Education motion to alter its desegregation

plan by converting Lakeview and Bragtown Elementary Schools,

which had become majority-black schools, into single-grade

attendance centers, and directed the Durham City Board of

Education to submit its pupil assignment plan for the 1974-75

school year (A.5 33-34). August 26, 1974, plaintiffs noticed

their appeal from the July 30 Order (A. 546) .

7

Plaintiffs subsequently objected to both the Durham

County and Durham City school board plans for 1974-75 (A. 542 ),

but their objections were overruled by the district court in

an Order entered August 29, 1974 (A. 551 ). Neither Order of

the District Court granted any relief against the City of

Durham or city agencies. Plaintiffs noticed their appeal from

the second district court decree on September 3, 1974 (A. 553 ).

Statement of Pacts

1. Durham City Schools

The Durham City School Administrative Unit.’, as it is

referred to under North Carolina law, is located within but

is not fully coextensive with, the City of Durham. During

the 1973-74 school year, the city school system operated 24

facilities: two high schools, six junior high schools, and

sixteen elementary schools, enrolling some 10,034 students in

grades 1-12 (A. 490); the city district extends approximately

five miles from North to South and four from East to West (A. 199).

As noted above, the present litigation to desegregate the

§/Durham city schools was commenced fifteen years ago. Prior

6/ Reported decisions in the Wheeler case are as follows: 196

F. Supp. 71 (M.D.N.C. 1961); 210 F. Supp. 839 (M.D.N.C.), rev'd

309 F.2d 630 (4th Cir. 1962); 326 F.2d 759 (4th Cir. 1964); 346

F . 2d 768 (4th Cir. 1965); 249 F. Supp. 145 (M.D.N.C.), rev1d in part,

363 F.2d 738 (4th Cir. 1966); 379 F. Supp. 1352 (M.D.N.C. 1974).

- 8 -

to the entry of the Orders from which these appeals are taken,

the case followed the usual pattern of school desegregation

actions: approval of pupil placement schemes, then freedom

of choice. After the Supreme Court's Green, Monroe and Raney

Vdecisions in 1968, proceedings initiated by the filing of

another Motion for Further Relief resulted in the approval

and implementation of a new plan embodying the mandatory assign

ment of pupils, which remained in effect from 1970-7], until

1974-75.

The 1970 plan employed the techniques of contiguous

geographic zoning and contiguous pairing only (A. 91, 99-100,

120). It did not utilize either satellite znni.nrr o-r non

contiguous pairing because of the added pupil transportation which

8/would have been required by these devices (A. 104-05, 110, 119)

and it did not have as a starting-point or goal, the approximation

of the system-wide racial, composition in the city schools (A.

102, 120). Indeed, projections under the 1970 plan as approved

showed schools anticipated to have student populations of widely

divergent racial makeup (A. 108-09, 488). Significantly, the

schools which were expected to be virtually all-black (more than

7/ Green v. County School Board of New Kent County, supra; Monroe

v. Board of Commissioners of Jackson, 391 U.S. 450 (1968); Raney

v. Board of Education of Gould, 391 U.S. 443 (1968).

8/ The Durham City Board did not operate its own transportation

system; students utilized public transit buses operated by the

Duke Power Company (A. 99-100).

9

80%) were previously operated as segregated all-black

institutions under the dual system (see A. 216-17). In short,

the plan did not, as conceived, seek to maximize desegregation

of the Durham city public schools (A. 107).

Nor did the 1970 plan, as executed, achieve this result.

The projected levels of desegregation — limited as they were

— did not materialize (A. 52-53, 57, 65, 188, 409). Many

traditionally black schools had less then 10% white students

when the geographic zoning plan was first implemented (A. 489).

The Board's disappointment with these results, and complaints

from parents about one-race schools, led to study of alternative

means of assignment which would bring about greater desegrega

tion of the city's school system (A. 50-51, 58-59, 65-67, 209).

This investigation, of ways to improve the desegregation plan

continued until the filing of plaintiffs' Motion for Further

Relief in 1972 — but without any action by the Board to

modify its plan despite steadily worsening results under its

1970 pupil assignment scheme. Although the Board was presented

9/

with several effective and fully feasible alternatives, all

9/ For example, the markedly different racial composition of

Durham and Hillside High Schools (55% and 78% black, respectively,

in 1973-74) could be eliminated by rezoning (A. 212). Plaintiffs

proposed a Durham city system plan doing just that (A. 466).

Contrast the Board's ineffective high school rezoning for 1974-75

(A. 541) .

10

of which required additional transportation of students (A. 39,

51, 197-99), it never made any changes in the 1970 plan until

after plaintiffs' Motion for Further Relief had been decided.

Instead, the decision was made to "study further" (A. 37, 69-70,

214-15). Once the Motion was filed, it became the excuse for

inaction (A. 42, 47, 62, 71).

By 1973-74, therefore, the Durham City school board was

still assigning students pursuant to a desegregation plan

drafted in 1970, utilizing no noncontiguous assignment techniques

and very little pupil transportation, and v/hich was markedly

ineffective in eliminating substantially disproportionate pupil

racial compositions among its schools, as illustrated by these

examples (A. 490):

School Grades 1973-74 % Black

Durham High 10-12 55%

Hillside High 10-12 78%

Brogden Jr. High 7-9 20%

Rogers-Herr Jr. High 7-9 81%

Shepard Jr. High 7-9 96%

Powe Elementary 1-6 28%

Watts Elementary 1-6 45%

Spaulding Elementary 1-6 97%

Pearson Elementary 1-6 98%

Burton Elementary 1-6 93%

These results were held by the district court to represent

"full compliance" with the Fourteenth Amendment; the Court

11

found the system was "'unitary' in the sense required in the

later decisions in Green . . Alexander . . . and Swann . .

(A. 526-27). Accordingly, the Court held that "further

court-ordered pairing or grouping of attendance zones is not

constitutionally mandated at this time" (A. 526).

2. Durham County Schools and Public Housing and Relocation

The Thompson case was brought.to end racial discrimination

within the Durham County School Administrative Unit in 1963,

10/and it, too, followed the classic pattern of such suits.

After this Court's 1969 reversal of a delay in eliminating

freedom of choice, which had been granted by the district court

11/prior to the decision in Alexander (Nesbit v. Statesville

City Bd. of Educ., 418 F .2d 1040 [4th Cir. 1969]), a geographic

zoning plan for county schools was submitted to, and approved

by, the district court. Enrollments under the plan remained

relatively stable until 1972, when the larger two of three

public housing projects constructed by the Durham Housing

Authority in the "city-out" area opened (A. 229). As a result

of this construction, in the area served by the Lakeview

10/ A more thorough history of the case is given in the

district court's opinion, A. 482-86.

11/ Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education. 396 U.S. 19

(1969) .

12

and Bragtown Elementary Schools, there was an immediate and

12/

radical shift in the racial composition of these schools:

1969-70

% Black

1971-72 1972-73 1973-74

Bragtown 37% 45% 63% 73%

Lakeview 36% 33% 57% 67%

When the 1970 plan was drafted, however.- the Durham County

board had no knowledge that this might occur, since there had

been no notification or communication from the Housing

Authority about the projects (A. 76, 77-78, 246, 267, 324,

Am

More than half of Durham County's 1970-1974 gain in black

student population is attributable to public housing, according

to the Superintendent (A. 236-37); he and other witnesses

agreed that the location of such a large concentration of units

in the Bragtown-Lakeview area was responsible for the sudden

13/resegregation of the two schools (A. 75, 164, 227-28, 260)-

12/ In Durham, as in many localities, public housing is

occupied predominantly by blacks (A. 150, 153, 276-88; see

A. 124) .

13/ Similarly, the county system had no knowledge of the public

housing when it planned the new Chewning Junior High School in

the Northern part of the system; the contemplated assignment zones

were modified in 1974-75 utilizing non-contiguous zoning for

Carrington Junior High to avoid a disproportionate concentration

of black students at Chewning (A. 254-57).

13

The Executive Director of the Housing Authority recognized

that public housing 'practices had caused or magnified the

concentration of black students in particular schools within

M /

both the city and county systems — largely because units

had been grouped together in massive projects rather than

being dispersed on 11 scattered sites" (A. 294) . He admitted

that the conscious location of public housing could assist

15/rather than retard desegregation of the schools, and that

the continued building of large multi-unit projects would lead

to further resegregation of schools (A. 296) . Yet the

Authority's position when the Bragtown-Lakeview units were

being considered was to ignore any impact upon the schools

and "leave it to the developer" of the Turnkey projects (A.

324-25).

Similarly, the Mayor and members of the City Council

expressed their total lack of concern with the consequences for

individual school populations of various city agency actions,

14/ The City Superintendent agreed that this had been the result

within the city (A. 269, 271), where both public housing and

relocation services had largely been limited to the predominantly

black southeastern section of Durham; the U.S. Department of

H.U.D. had for this reason imposed a temporary prohibition on

further location of public housing in southeast Durham (A. 124,

143, 171, 306, 346-48).

15/ The benefits of joint planning with school officials were

also recognized by the Durham Planning Director (A. 400) and the

Mayor (A. 125-26). However, the district court did not order it.

14

including, in particular, public housing, urban renewal, and

16/

relocation programs — stating either that the Council never

thought about possible effect on the schools or that these

activities were completely beyond the control of the city's

governing body, being committed to other governmental entities

17/

(A. 122-23, 132, 136-37, 143, 158-59, 163, 178, 185). But

not only does the Council appoint the membership of these

"independent governmental agencies" (the city district school

board, Housing Authority, Redevelopment Commission, etc.) as

well as receive periodic reports about housing and renewal

activities (A. 174, 184, 290); it may replace members, merge

or abolish the agencies, and influence or even’stop particular

projects if it so desires (A. 127, 344-45). In fact, the

Council has discussed the location of specific public housing

units (A. 175, 177-78) and it has contributed funds to the

Housing Authority for specific uses it favors (A. 345). The

governmental prerogatives have simply not been exercised for the

purpose of preventing the resegregation of schools as occurred

at Bragtown and Lakeview.

16/ Since 1962, Durham has provided relocation assistance to

more than a thousand families and individuals (A. 362-71), most

of whom were blacl̂ (ibid.) . Historically, most of these persons

were relocated in southeast Durham; and 65% of those relocated

have moved to public housing projects (A. 374-75).

17/ Council members knew, however, of the tendency of the public

housing program as it has been operated in Durham to increase the

15

3. Plaintiffs' Proposed Plans of Desegregation

At the trial on the merits in May 1974, plaintiffs

presented alternative plans of desegregation for consolidated

and separately operated school districts in Durham City and

County (A. 454-69), through the testimony of educational

and computer expert witnesses who had prepared the plans

(A. 411-39). The plans included separate assignment proposals

for students in the existing Durham City and County systems

in a manner which would maximize desegregation (A. 429-30).

The plans were based upon geographic zoning, utilizing a

computer model to draw separate zones for black and white

students at each grade level which would achieve desegregation

of the schools while minimizing pupil transportation (A. 416-17).

As the district court found, under plaintiffs' plans the

projected racial composition of city schools would range from

63% to 74% black, and that in county schools between 17% and

31% black (A. 50 9) .

17/ (Continued)

residential concentration of blacks (A. 122-23, 154-55). They

can hardly have been completely ignorant of public school affairs

in the city they governed.

16

Mrs. Stein, one of the drafters, testified that the

computer drawn zones provided a good basis upon which the

school authorities could make actual pupil assignments in

order to achieve full desegregation of the city and county

schools, although the computer zones would have to be modified

to conform to natural boundaries, etc.; there was no reason

to expect that such modifications (some of which had been

made in the process of devising the plans) would result in a

substantial change in projected racial compositions (A. 423-

26) .

The District Court found that "the various plans of th<̂

plaintiffs demonstrate that the schools can be more effectively

desegregated" (A. 509).

4. The 1974-75 Plans Submitted By the Boards

In the Fall of 1973, the Durham County Board determined

to modify its elementary school pupil assignment plan in order

to eliminate the resegregation which had developed as a result

of the public housing in the Bragtown-Lakeview area (A. 441-42).

A variety of options, involving rezoning, pairing or clustering

was available to alter the majority black enrollments at

these two schools (A. 81-82). Through the Title IV Center

in Raleigh, the Board brought in a consultant with experience

17

in desegregation from Ohio State University (A. 444), who

recommended that Bragtown and Lakeview each be included

with two nearby schools in separate three-school clusters

(A. 247-48). Instead of adopting this recommendation,

however, the Superintendent proposed and the Board ultimately

adopted and submitted to the district court a plan whereby

Bragtown and Lakeview would operate as Sixth Grade and

Kindergarten centers, respectively, for a larger cluster

involving a total of six elementary schools: Bragtown,

Lakeview, Hillandale, Holt, Glenn and Merrick-Moore (A. 240-41,

18/

445) .

Plaintiffs objected to the county plan because the black

students who now predominate in the Bragtown and Lakeview

areas will be assigned away from their homes for a dis

proportionate number of years (5 of 6) while white students

in the clustered schools will remain in their pre-1974 assign

ment patterns for 5 of 6 years. Plaintiffs noted that their

18/ The plan also involves minor changes in zone lines among

county elementary schools, moving approximately 100 students

each from Little River to Mangum, Holt to Little River, and

Hillandale to Holt (A. 241).

18

desegregation proposal presented at trial would achieve

results equal to those under the county plan without

disproportionately burdening the black community in this

manner (A. 543). The District Court overruled plaintiffs'

objections and approved the county plan on August 29, 1974

(A. 552).

In accordance with the July 30 Order of the District

Court (A. 534), the City Board of Education also submitted

a 1974-75 plan (A. 536-41). This proposal involved a-minor,

shift in the zone line between the two city high schools,

and the pairing of two additional elementary schools.

However, it did not seek nor was it anticipated to eliminate

all of the substantial disproportions in the racial composition

of city schools (A. 541). For example, Brogden Junior High

School was projected 20% black, and Powe Elementary School

was projected 31% black, while Shepard and Whitted Junior

High Schools, as well as Fayetteville Street, Pearson, and

Spaulding Elementary Schools were each expected to be more

than 90% black.

Plaintiffs objected to the constitutional sufficiency

of this plan (A. 542-43), but their objections were overruled

by the District Court (A. 552), apparently in accordance with

19

the Court's earlier holding that a unitary system within

the city had been established. Nevertheless, the District

Court directed the City Board to submit further revisions

of its desegregation plan for the 1975-76 school year, and

to place special emphasis on "schools which currently have

a white pupil enrollment of 20 percent or less" (A. 552).

20

ARGUMENT

I

The District Court Should Have Ordered

Complete Desegregation Of The Durham

City School System

Repeatedly in its Opinion, the District Court makes the

assertion (both as a Finding of Fact and also as a Conclusion

of Law) that "[w]ith the implementation of . . . [the 1970]

desegregation plan . . - the Durham City school system is now

'unitary' . . . " (A. 492-93, 504, 526-27). Whatever the

proper characterization of the statement, it is flatly wrong

under' governing rulxiiys of the United Grates Supreme Court- ana

decisions of this and other Circuits.

Even a quick perusal of the results expected under the plan,

and the actual experience thereunder (A. 488-90) indicates the

continuing substantial disproportionality of racial composition

among the various schools in the Durham city system. As this

Court has said in similar circumstances,

In the light of the history of state-

enforced segregation in the [Durham]

schools, the marked residual disparity

in the racial balance of the schools

under the plan of the District Court

strongly suggests that the plan is

ineffective to attain an acceptable

degree of realistic desegregation.

21

Medley v. School Bd. of Danville, 482 F.2d 1061, 1063 (4th Cir.

1973), cert, denied, 414 U.S. 1172 (1974). Furthermore, the

cause of the ineffectiveness is not hard to discern on this

record. The 1970 plan was drafted and approved by the district

court before even this Court's decision in Swann v. Charlotte-

Mecklenburq Bd. of Educ., 431 F .2d 138 (4th Cir. 1970), rev1d in

part on other grounds, 402 U.S. 1 (1971), which endorsed the use

of non-contiguous assignment techniques and pupil transportation

at the secondary level in order to achieve effective school

desegregation. As described above, it employed only geographic

19/rezoning and contiguous pairing, with minimal transportation of

20/

pupils. It was nor aevxsea xn antxcxpatxon ot tne governxng

standard enunciated by the Supreme Court in Swann, supra: that

19/ The district court's description of the plan as involving the

"pairing of schools at opposite ends of the City" (A. 526) is

somewhat misleading. Contiguous sets of elementary schools in

northeastern and southern Durham were paired but there was no

combination of identifiable schools of opposite racial concentra

tions at either extremity of the district.

20/ Although defendant Durham City Board of Education included

in its Proposed Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law the

following finding:

The bussing remedy, approved in Swann,

supra, has been fully utilized in the

Durham City Administrative School Unit,

and further Court-ordered pairing or

grouping of attendance zones could result

in significant impingement of the educa

tional process.

the district court limited its holding as follows, declining to

employ the term "fully":

22

desegregation be maximized. In short, proving ineffective, and

having been designed without regard to the strictures of Swann,

the 1970 plan must be replaced with one holding greater promise

21/ 22/

of effectuating system-wide desegregation "root and branch"

The obligation of the Durham City School Board to achieve

the actual desegregation of all of its schools is not mitigated,

as the district court apparently thought, by the fact that

demographic changes may have contributed to the failure of the

1970 decree (see A. 493-94, 504-05). The 1970 plan could not

be said to create a unitary system instanter, even accepting

arguendo the sufficiency of its projections, but only when it

lictCl jprOVfciCc _i_ u S vii j. .L. j_Ii L u a r u x C o C v C i . Ca-iuO • G i. 0011 V • u O U n l. y

School Bd. of New Kent County, supra; Lemon v. Bossier Parish

School Bd., 444 F .2d 1400, 446 F.2d 911 (5th Cir. 1971). Nor is

20/ (Continued)

The busing remedy, approved in Swann,

supra, has been utilized in the Durham

City Administrative School Unit, . . . .

(A. 526)

21/ Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent County, supra, 391 U.S.

at 437-38; see Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, Denver, 413 U.S. 189, 214

(1973); Milliken v. Bradley, 41 L.Ed.2d 1069, 1096 (1974).

22/ Cf. Goss v. Board of Educ. of Knoxville, 444 F.2d 632, 634 (6th

Cir. 1971)("We believe, however, that Knoxville must now conform

the direction of its schools to whatever new action is enjo ed upon

it by the relevant 1971 decisions of the United States Supreme Court")

Adams v. School Dist. No. 5, Orangeburg, 444 F.2d 99 (4th Cir.), cert.

denied sub nom. Winston-Salem/Forsyth County Bd. of Educ. v. Scott,

404 U.S. 912 (1971).

23

defendants' obligation lessened because, during the time that

this ineffective plan was being tried, some formerly white

schools became majority-black. Flax v. Potts, 464 F.2d 865

(5th Cir.), cert, denied, 409 U.S. 1007 (1972); Kelley v.

Metropolitan County Bd. of Educ., 463 F.2d 732 (6th Cir.), cert.

denied, 409 U.S. 1001 (1972). As the Fifth Circuit recently

put it:

We view this case as presenting no more

than a motion in the district court for

further relief in a typical school

desegregation case where modification is

indicated because of lack of success.

Hereford v. Huntsville Bd. of Educ., 504 F .2d 857, 858 (5th Cir.

1974) (emphasis supplied). Accord, Ellis v. Board f Public

Instruction of Orange County, 465 F.2d 878 (5th Cir. 1972);

Boykins v. Fairfield Bd. of Educ., 457 F.2d 1091 (5th Cir. 1972)

Dowell v. Board of Educ. of Oklahoma City, 465 F .2d 1012 (10th

Cir.), cert, denied, 409 U.S. 1041 (1972); Monroe v. County Bd.

of Educ., 505 F.2d 109 (6th Cir. 1974); Boyd v. Pointe Coupee

Parish School Bd., No. 71-3305 (5th Cir., Dec. 10, 1974), rev1 g

332 F. Supp. 994 (E.D. La. 1971).

Certainly the 1970 plan cannot be justified as resulting

in only a "small number of one-race schools," Swann, supra, 402

U.S., at 26. See A. 525-26. The Supreme Court did not intend

by this language to validate continued substantial school

24

segregation, as is found in Durham. See Northcross v. Board

of Educ. of Memphis, 466 F.2d 890, 893 (6th Cir. 1972), cert.

denied, 410 U.S. 926 (1973), vacated in part and remanded on

other grounds, 412 U.S. 427 (1973); Medley v. School Bd. of

23/

Danville, supra. Even one or two virtually all-black schools

may be constitutionally unacceptable if feasible alternatives

for their desegregation exist. E.g., Weaver v. Board of Public

Instruction, 467 F .2d 473 (5th Cir. 1972), cert. denied. 410

U.S. 982 (1973); Boykins v. Fairfield Bd. of Educ., supra.

Swann directed school boards and district courts "to make

every effort to achieve the greatest possible degree of actual

desegregation. . . .11 40 2 U.S. , at 26. It specifically approved

the use of pupil transportation, together with other techniques

such as pairing, grouping, and grade restructuring of schools,

as permissible tools to bring about the constitutionally required

result of actual school desegregation. And it suggested, if it

did not explicitly state, that valid grounds for objecting to

desegregation plans using pupil busing exist only when "the time

23/ At least one Court of Appeals has suggested that the

language relied upon by the district court reflects upon the

proof necessary to establish a violation, while the following

sentence in the Supreme Court's opinion articulates the remedial

standard ("achieve the greatest possible degree of actual desegre

gation"). See Kelly v. Guinn, 456 F .2d 100, 109-10 (9th Cir.

1972), cert. denied, 413 U.S. 919 (1973).

25

or distance of travel is so great as to either risk the health

of the children or significantly impinge on the educational

process." 402 U.S., at 30-31. Detailed factual findings about

the impracticality of alternative assignment plans which promise

greater desegregation are required to sustain district court

decisions rejecting such plans. Adams v. School Dist. No. 5,

Orangeburg, supra, 444 F.2d, at 101; Adams v. Rankin County Bd.

of Educ., 485 F.2d 324, 326 (5th Cir. 1973).

There are no such findings on this record. Indeed, the

district court found explicitly that plaintiffs' Durham City-only

desegregation plan as well as the plans considered by the School

Board in 1972-73, each of which would utilize pupil transportation,

were fully feasible (A. 505-07, 509). Compared to Charlotte-

Mecklenburg, or Norfolk, the Durham system is exceedingly compact

(A. 199); during the freedom-of-choice era, students travelled

as far as would be required in order to effectively desegregate

the system today (A. 101).

The District Court praised the city school board for its

continual restudy of its desegregation plan (A. 505, 523-24, 531).

The Durham City Board has been notorious for study, but it has

not translated that study into action. Both in 1970 and 1972,

the board abruptly ceased consideration of proposals for further

desegregation when motions for further relief were filed by the

26

plaintiffs (A. 42, 47, 62, 71, 93). The district court should

have required more than continued study.

We respectfully submit that this Court's decision in Medley,

supra, is controlling; it, as well as the other authorities cited

above, requires reversal of the judgment below with instructions

to the district court to require submission of a new plan of

desegregation for the Durham City schools, to be based upon the

alternatives previously considered by the board, or those

developed by the plaintiffs, and to achieve the levels of

desegregation projected under these plans. Adams v. School Dist.

No. 5, Orangeburg, supra; Pate v. Dade County School Bd., 434

F . 2d 1151 (5th Cir. 1970).

II

The Durham County Board's 1974-75

Pupil Assignment Plan Unconstitutionally

Places A Disproportionate Burden Upon

Black Students

It is now an accepted principle of school desegregation law

that black students should not bear the sole, or a disproportionate

share of, the burdens of achieving desegregation. See, e.g.,

Harrington v. Colquitt County Bd. of Educ., 460 F.2d 193, 196

n.3 (5th Cir.), cert. denied, 409 U.S. 915 (1972); Hart v. County

School Bd. of Arlington County, 459 F.2d 981, 982 (4th Cir. 1972)

(school officials may not, in dismantling dual system, "create

27

another form of invidious discrimination"); Arvizu v. Waco

Independent School Dist., 495 F.2d 499 (5th Cir. 1974); Robinson

v. Shelby County Bd. of Educ., 467 F.2d 1187 (6th Cir. 1972).

The requirement of fairness has most often been applied in

situations where school boards have attempted to close down

black schools completely rather than desegregate them. E.g.,

Lee v. Macon County Bd. of Educ., 448 F .2d 746 (5th Cir. 1971);

Green v. School Bd. of Roanoke. 316 F. Supp. 6 (W.D. Va. 1970),

aff1d sub nom. Adams v. School Dist. No. 5, Orangeburg, supra;

Brice v. Landis, 314 F. Supp. 974 (N.D. Cal. 1969); McFerren v.

County Bd. of Educ., 497 F .2d 924 (6th Cir. 1974).

However, it is equally applicable to plans which place the

major burden of busing for desegregation upon black students.

Harrington v. Colquitt County Bd. of Educ., supra; Clark v. Board

of Educ, of Little Rock, 449 F.2d 493 (8th Cir. 1971), cert. denied,

405 U.S. 936 (1972). In these cases, too, courts have required

nonracial justification for the plans. Particularly relevant to

this inquiry is the existence of alternative methods of assignment

which are equally effective but which distribute the burdens of

desegregation more evenly.

In the instant case, the effect of the County Board's 1974-75

plan making Bragtown and Lakeview schools single-grade centers is

strikingly clear: because a majority of black students now reside

28

in the original attendance areas for these schools, they must

be bused to other schools for five of seven school years

(counting kindergarten), while white students who formerly

attended surrounding facilities will "stay at home" five of

seven years.

This gross difference in the distribution of the burdens

of achieving desegregation of Brag town and I.akeview is unnecessary;

and the District Court failed to make any findings of a neutral,

nonracial justification for the Board's proposal. Two different

alternatives are available to carry out the board's intentions

without exacting this penalty from the black community. Dr.

Glatt, called in as a consultant by the Board, suggested two

three-school clusters (A. 247-48, 444), which would have somewhat

reduced the busing differential for black and white students.

And plaintiffs' Durham County plan utilized gerrymandered

attendance zones while retaining the same grade structure for

all elementary schools in order to desegregate them. Either of

these proposals would have been preferable to the six-school

cluster implemented by the board.

It is noteworthy that while the sixth-grade center technique

(converting black schools to sixth grade centers) formed the

basis of the initial plan approved in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklen

burg Bd. of Educ., Civ. No. 1974 (W.D.N.C., August 7, 1970), aff'd

29

402 U.S. 1. (1971), that plan was recently abandoned in favor

of one which treated all segments of the community on an

equitable basis. The district court should have required the

same in this case, by rejecting the County Board's submission.

*

III

The District Court Should Have Granted

Injunctive Relief to Halt Practices Of

City Agencies Which Thwarted Effectuation

Of Desegregation In Durham

The record in this case reveals a callous disregard by

governmental agencies in Durham County of both moral obligation

and also national policy, which the district court should have

corrected by injunctive relief in order to preserve the

effectiveness of its decrees. Yet although the Bragtown-Lakeview

example was fresh evidence of the need, the court failed to act.

The testimony of City Councilmen, the City Planner, the

Directors of Redevelopment and of the Housing Authority, and

that of the two School Superintendents showed that the non-school

governmental agencies had never made any attempt to consider

what impact their activities might have upon the success of

the respective school systems' desegregation efforts. These

officials simply refused to face up to their general obligation

as governmental officers to enforce all the laws, and their

actions frustrated the national policy favoring both desegregation

30

and the minimization of pupil transportation. See 42 U.S.C.A.

§ 2000d; 20 U.S.C.A. §1652 (1974). As the history of the

Bragtown-Lakeview housing projects demonstrates, the Housing

Authority's failure to consider these matters in locating and

determining the size of these projects has made necessary

greater and longer pupil transportation in the county school

sys tern.

Furthermore, housing officials and school superintendents

agreed that if the housing and renewal programs continued to

operate as they had, further resegregation of city or county

schools was likely. But the district court granted no relief

and made no findings on this subject.

The relationship between residential segregation and

school segregation has long been recognized. E.g., Brewer v.

School Bd. of Norfolk, 397 F .2d 37 (4th Cir. 1968); Swann v.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., supra, 402 U.S., at 21;

Sloan v. Tenth School Dist. of Wilson County, 433 F.2d 587

(6th Cir. 1970). Courts have also noted the consequences for

school operations of racially impacting practices with respect

to the location of public housing. E.g., Crow v. Brown, 332

F. Supp. 382, 391 (N.D. Ga. 1971), aff1d 457 F.2d 788 (5th Cir.

1972). There is ample basis for judicial action to curb dis

criminatory practices.

31

In the instant case the court is presented with a panorama

of governmental activities which is nothing short of remarkable.

If the testimony is to be credited, each city agency and official

managed to perform their official duties without assessing their

impact upon any other agencies. The City Council appoints

members of housing and school agencies, receives official reports

and citizen complaints, but strictly respects the division of

governmental powers by permitting total latitude to these other

agencies in running their own programs. The Housing Authority

and Redevelopment Commission undertake absolutely no coordination

with the school boards — although everyone seems to recognize

JL 1~ — ~ 1- ^ -v-v^3 -? VN — , +- A •» 1 ^ "Vs ̂ n — T -f-Vs r s TXr-\n i‘ >-v AVL t i U L O *— V y w W w. »— * — - » — -*--- — »-----_J

Authority has further passed the buck to the developers of its

turnkey projects, although these individuals are not governmental

officials and although the Authority does not spell out any

requirement that developers take impact on school desegregation

into account in planning or locating housing.

Surely this picture of governmental horses wearing huge

sets of side-vision blinders, or of governmental ostriches with

their heads in the sand, represents autonomy rampantly carried

to the point of thoughtlessness and irresponsibility. As Judge

Wright has said, "the arbitrary quality of thoughtlessness can be

as disastrous and unfair to private rights and the public interest

32

as the perversity of a wilful scheme." Hobsen v. Hansen, 269

F. Supp. 401, 497 (D.D.C. 1967), aff1d 408 F.2d 175 (D.C. Cir.

1969) .

It should have been clear to the District Court, as a

result of the testimony, that unless the City was directed to

require that its agencies consider impact upon desegregation

before taking action, there would be no coordination, and

Bragtown-Lakeview problems were likely to be repeated in the

future — seriously impeding the effectiveness of the court's

desegregation decrees (A. 125-26, 139-40, 356-57, 392-93). The

court defaulted in its obligation to protect the integrity of

its orders by not requiring that the City at least consider

the school systems' needs before building additional multi-unit

public housing, undertaking urban renewal, etc.; the injunction

requested by the plaintiffs (see p. 7 above) is but a modest

step which promised to avoid the need for additional busing, or

more serious measures in the future.

The District Court made no findings with respect to these

issues, nor explained its reluctance to grant relief. However,

if the court was of the view that the Housing Authority, Redevelop

ment Commission or other agencies should themselves be subject

to any decree (despite plaintiffs' contention, which we submit

is amply supported on this record, that the City Council retains

33

sufficient control over these agencies to make any decree

effective), the Court had full power under F.R.C.P. 19 and 21

to require the joinder of additional parties. See Bradley v.

School Bd. of Richmond, 51 F.R.D. 139 (E.D. Va. 1970). Since

this case must be remanded for further proceedings to complete

the desegregation of the city schools, the court will have ample

opportunity to add such parties should it conclude that a decree

should run against them as well as the City.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, plaintiffs-appellants respectfully

nrsv -t-Viat fho -indrrme'nt.s below be reversed, and the cause remanded

with directions to: (1) require the submission for the approval

of the district court, and implementation, of a new plan of

desegregation which eliminates racially identifiable schools

from the Durham City School Administrative Unit; (2) require

the submission for the approval of the district court, and

implementation, of a new plan of elementary school pupil assign

ment for the Durham County School Administrative Unit which does

not place a disproportionate share of required pupil transporta

tion upon black students; and (3) enter an appropriate injunction,

joining such additional parties for this purpose as the court

may deem necessary, against City authorities and agencies requiring

that they avoid taking actions which will result in recreating

or resegregating racially identifiable schools, because of

34

foreseeable racial residential consequences of those actions,

in either the Durham City or County school systems.

Plaintiffs-appellants further pray that this Court award

them their costs and reasonable attorneys' fees in connection

with these appeals.

Respectfully submitted,

951 S. Independence Blvd.

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

W ILLIAM A MAP PM ,TP_

203 1/2 East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina 27701

J. II. WHEELER

118 West Parish Street

Durham, North Carolina 27701

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN J. CHACIIKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

35

CERTIFICATE OF SEPVICE

I hereby certify that on this 9th day of January, 1975,

I served two copies of the foregoing Brief for Appellants upon

counsel for the defendants-appellees herein, by depositing

same in the United States mail, first class postage prepaid,

addressed as follows:

Jerry L. Jarvis, Esq. James L. Newsom, Esq.

First Union Nat'l Bank Bldg. P. 0. Box 2088

Durham, North Carolina 27701 Durham, North Carolina 27702

Robert Holleman, Esq.

First Federal Building

W. I. thornton, Jr., Esq.

1006 Central Carolina Bank Bldg,

Durham, North Carolina 27701 Durham, North Carolina 27702

Hon. Andrew Vanore, Esq.

P. O. Box 629

Raleigh, North Carolina 27602

-36-